Abstract

The human TAS2R38 gene encodes a bitter taste receptor that regulates the bitterness perception and differentiation of ingested nutritional/poisonous compounds in the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract. TAS2R38 gene variants are associated with alterations in individual sensitivity to bitter taste and food intake; hence, these genetic variants may modify the risk for diet-related diseases, including cancer. However, little is known about the association between TAS2R38 polymorphisms and gastric cancer susceptibility. The present case-control study examined the influence of TAS2R38 polymorphisms on food intake and determined whether they predict gastric cancer risk in Koreans. A total of 1,580 subjects, including 449 gastric cancer cases, were genotyped for TAS2R38 A49P, V262A, I296V and diplotypes. Dietary data were analysed to determine the total consumption of energy, fibre, vegetables, fruits, sweets, fats, alcohol and cigarettes. TAS2R38 diplotype was not associated with food, alcohol or cigarette consumption, either independent or dependent of gastric cancer phenotype. However, the PAV/AVI diplotype significantly increased gastric cancer risk (adjusted odds ratio: 1.513; 95% confidence interval: 1.148–1.994) independent of dietary intake. Findings suggest that TAS2R38 may be associated with the risk for gastric cancer in Koreans, although the TAS2R38 diplotype did not influence dietary intake.

Taste sensitivity plays a central role in individual dietary behaviour. Differential taste sensitivity leads to differing attraction to a variety of foods; hence, it may influence consumption1. Human taste consists of five major categories (sweet, sour, salty, umami and bitter), of which bitterness is a key determinant for the acceptance and/or rejection of foods, such as bitter-tasting vegetables, alcohol and sweets2,3,4. For this reason, it has been hypothesized that differential bitter taste sensitivity may contribute to the risk for diet-related health outcomes, such as cancer5,6.

Human bitterness perception is mediated by signalling of transmembrane G protein-coupled receptors encoded by type 2 bitter-taste receptor (TAS2R) genes. Approximately 25 types of functional TAS2Rs are located on chromosomes 5, 7 and 12 and are expressed in various organs, including the brain, oral cavity, lung, pancreas and gastrointestinal mucosa7,8,9. Chemosensing by TAS2Rs differentiates bitter compounds as well as beneficial and noxious substances in the diet as a checkpoint2,10. In particular, TAS2Rs in the gastrointestinal tract initiate the subsequent process of digestion and nutrient absorption. TAS2Rs also trigger protective responses, such as vomiting and excretion, to remove toxic chemicals by activating hormonal and neuronal cascades systems8,11.

Among the TAS2R family, TAS2R38 gene is the most intensively studied genetic locus for bitter taste perception. Three variants, A49P (145G > C, rs713598), V262A (785T > C, rs1726866) and I296V (886A > G, rs10246939), in the TAS2R38 gene are associated with bitter taste sensitivity as tested with 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) and phenylthiocarbamide (PTC)12,13. The TAS2R38 PAV/PAV diplotype is sensitive to PTC/PROP (taster), but the AVI/AVI diplotype rarely responds to thiourea (N-C=S) moiety-containing chemicals (non-taster). Earlier studies demonstrated that TAS2R38 diplotype is associated with the consumption of bitter foods, cruciferous vegetables (high in a group of thiourea-containing compounds), and alcohol as well as blood folate concentrations5,9,14,15,16. Therefore, few studies have examined the association between TAS2R38 genetic variation and disease risk, especially pertaining to cancer, but the findings have been inconclusive5,17,18.

Gastric cancer is one of the common malignancies globally, and the highest incidence rates are found in Eastern Asia, Japan, China, Mongolia and Korea19,20,21. Although the overall incidence and annual mortality of gastric cancer are continuously declining regionally, gastric cancer remains the second most common type of cancer (30,847 new case incidence in 2012), and the third most common reason for cancer-related death in Korea (crude and age-standardized mortality rates in 2012: 18.6 and 11.2 per 100,000)22. Diet is a crucial environmental risk factor in gastric cancer aetiology. Abundant intake of vegetables, fruits and fibres reduces the risk for gastric cancer23,24,25, whereas a low folate intake26 and a high consumption of red meat and sodium elevate the risk27,28,29,30. Epidemiological evidence suggests that various socio-economical and/or psychological factors determine food choice and consumption in individuals31,32,33; however, studies have inadequately addressed the corresponding biological reasons and their association with disease risk. Given the taste sensitivity-diet-disease risk hypothesis, differential taste sensitivity due to TAS2R38 genetic variants may influence dietary intake and thus modify the risk for gastric cancer. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has examined the TAS2R38-diet association in gastric cancer risk.

This study aimed to examine whether genetic variations in TAS2R38 influence the consumption of food, alcohol and tobacco in Koreans. The study also investigated whether TAS2R38 variants are associated with the risk for gastric cancer either dependent or independent of dietary intake.

Results

Study population characteristics

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study participants by gastric cancer phenotype. The subjects with gastric cancer were more likely to be older, male, drinkers and smokers but less likely to engage in regular physical activity compared with the controls (p < 0.001 for all variables except alcohol drinking; p = 0.004 for alcohol drinking behaviour). Helicobacter pylori infection was significantly more common among subjects with gastric cancer (p < 0.001). These variables might be associated with gastric cancer risk and were therefore included in subsequent statistical analyses that considered potential confounders. Subjects exhibited significant differences in the dietary intake of the examined foods depending on gastric cancer phenotype. Controls consumed more dietary fibre (p < 0.001), dark green vegetables (p = 0.007), all fruits (p < 0.001) and citrus fruits (p < 0.001) than cases.

Table 1. Descriptive data of study subjects by gastric cancer phenotype.

| Total (N = 1,580) | Case (N = 449) | Control (N = 1,131) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics | ||||

| Number of participants (%) | ||||

| Male | 832 (52.6) | 296 (65.9) | 536 (47.3) | <0.001 |

| Female | 748 (47.3) | 153 (34.0) | 595 (52.6) | |

| Age (years) | 53.0 ± 9.31 | 55.4 ± 10.7 | 52.1 ± 8.4 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.7 ± 3.04 | 23.6 ± 3.2 | 23.7 ± 2.9 | 0.342 |

| Smoking behaviour (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Non-smoker | 815 (51.5) | 170 (37.8) | 645 (57.0) | |

| Ex-smoker | 416 (26.3) | 131 (29.1) | 285 (25.2) | |

| Current smoker | 313 (19.8) | 131 (29.1) | 182 (16.0) | |

| Missing | 36 (2.2) | 17 (3.7) | 19 (1.6) | |

| Alcohol drinking behaviour (%) | 0.004 | |||

| Current drinker | 916 (57.9) | 256 (57.0) | 660 (58.3) | |

| Ex-drinker | 123 (7.7) | 46 (10.2) | 77 (6.8) | |

| Non-drinker | 505 (31.9) | 130 (28.9) | 375 (33.1) | |

| Missing | 36 (2.2) | 17 (3.7) | 19 (1.6) | |

| Regular exercise (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 746 (47.2) | 154 (34.3) | 592 (52.3) | |

| No | 793 (50.1) | 279 (62.1) | 514 (45.4) | |

| Missing | 41 (2.5) | 16 (3.5) | 25 (2.2) | |

| Helicobacter pylori infection (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Negative | 489 (30.9) | 38 (8.4) | 451 (39.8) | |

| Positive | 1091 (69.0) | 411 (91.5) | 680 (60.1) | |

| Dietary intake | ||||

| Energy (kcal/day) | 1850.7 ± 638.4 | 2038.1 ± 694.2 | 1778.7 ± 600.5 | <0.001 |

| Fibre (g/day) | 20.4 ± 6.7 | 19.4 ± 6.5 | 20.8 ± 6.7 | <0.001 |

| Vegetables (g/day) | 382.4 ± 194 | 374.3 ± 203.3 | 385.6 ± 190.3 | 0.070 |

| Cruciferous | 183.1 ± 118.1 | 196.4 ± 135.9 | 178 ± 110.1 | 0.198 |

| Dark green | 41.2 ± 38.3 | 38.4 ± 36.8 | 42.3 ± 38.9 | 0.007 |

| Non-starchy | 335.8 ± 177.9 | 331.4 ± 187.7 | 337.6 ± 174.0 | 0.120 |

| Fruits (g/day) | 182.1 ± 201.6 | 135.4 ± 166.9 | 199.9 ± 210.8 | <0.001 |

| Citrus | 39.2 ± 55.3 | 30.7 ± 44.5 | 42.2 ± 58.4 | <0.001 |

| Sweets (g/day) | 30.1 ± 63.2 | 33.5 ± 91.6 | 28.8 ± 48.2 | 0.831 |

| Fat-foods (g/day) | 4.7 ± 4.8 | 4.6 ± 5.4 | 4.7 ± 4.6 | 0.348 |

Numbers in parentheses are percentages; all other data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Variables for dietary intake were adjusted for energy intake. *P-values denote the difference between cases and controls at the 95% confidence level.

Distribution of TAS2R38 genetic variants

The distribution of three genotypes and diplotypes of TAS2R38 is summarized in Table 2. For all three TAS2R38 variants, the heterozygous genotype was most prevalent. The PA A49P genotype was present in 54.1% and 46.0% of case and control, respectively. The V262A and I296V variants were in complete linkage disequilibrium (r2 = 1.0), and the prevalence of heterozygous genotypes in both loci were 54.5% for cases and 46.0% for controls. Three out of eight hypothetically possible TAS2R38 haplotypes were observed in the study population. The most common haplotypes were PAV and AVI, and the combination of these haplotypes (PAV/PAV, PAV/AVI and AVI/AVI) covered most diplotypes observed in the study population. The AAV haplotype was detected in only two subjects with gastric cancer. For this reason, subjects with a diplotype containing an AAV allele (AVI/AAV) were excluded from all statistical analyses. Diplotype is known to depict the interaction between single genetic variation and haplotypes in individuals’ diploid genome and therefore affords greater power in discriminating phenotypic effects12,34. Thus, the current study focused more on the effect of diplotype than of each single genetic variant. The chi-square tests revealed significant differences in the distribution of TAS2R38 genotype and diplotype depending on gastric cancer phenotype (Table 2).

Table 2. Distribution of the three TAS2R38 variants and the diplotypes.

| Total (N = 1,580) | Case (%) |

Control (%) |

p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 449 | (28.4) | 1,131 | (71.6) | ||

| A49P | |||||

| PP | 138 | (30.7) | 412 | (36.4) | 0.015 |

| PA | 243 | (54.1) | 521 | (46.0) | |

| AA | 68 | (15.1) | 198 | (17.5) | |

| V262A | |||||

| AA | 138 | (30.7) | 412 | (36.4) | 0.009 |

| AV | 245 | (54.5) | 521 | (46.0) | |

| VV | 66 | (14.7) | 198 | (17.5) | |

| I296V | |||||

| VV | 138 | (30.7) | 412 | (36.4) | 0.009 |

| VI | 245 | (54.5) | 521 | (46.0) | |

| II | 66 | (14.7) | 198 | (17.5) | |

| Diplotype | |||||

| PAV/PAV | 138 | (30.7) | 412 | (36.4) | 0.012 |

| PAV/AVI | 243 | (54.1) | 521 | (46.0) | |

| AVI/AVI | 66 | (14.7) | 198 | (17.5) | |

| AVI/AAV | 2 | (0.4) | – | – | |

*P-values from chi-square tests.

Association between TAS2R38 diplotype and dietary intake

Table 3 summarizes the mean consumption of selected food groups, alcohol and cigarettes for each major TAS2R38 diplotype. Total energy, dietary fibre, all vegetables, cruciferous vegetables, dark green vegetables, non-starchy vegetables, all fruits, citrus fruits, sweets, fat-foods and alcohol consumption as well as tobacco smoking were examined. However, no significant differences in those variables were noted among TAS2R38 diplotypes. When the subjects were stratified based on gastric cancer phenotype, again, TAS2R38 diplotype did not predict dietary or alcohol intake or cigarette smoking (data not shown).

Table 3. Mean consumption of select foods, alcohol and tobacco stratified by TAS2R38 diplotype.

| PAV/PAV | PAV/AVI | AVI/AVI | p1† | p2‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 530 (128, 402)* | N = 736 (232, 504) | N = 256 (61, 195) | |||

| Energy (kcal/day) | 1845.1 ± 649.3 | 1867.1 ± 630.6 | 1812.5 ± 640.3 | 0.280 | 0.223 |

| Fibre (g/day) | 20.6 ± 6.4 | 20.5 ± 6.9 | 20.1 ± 6.4 | 0.677 | 0.435 |

| Vegetables (g/day) | 387.9 ± 186.6 | 382.8 ± 198.1 | 371.1 ± 197.7 | 0.363 | 0.187 |

| Cruciferous | 186.5 ± 116.3 | 184.6 ± 120.2 | 172.0 ± 115.9 | 0.198 | 0.124 |

| Dark green | 42.6 ± 36.3 | 41.3 ± 41.9 | 38.2 ± 30.9 | 0.458 | 0.245 |

| Non-starchy | 342.3 ± 171.6 | 336.1 ± 182.0 | 322.4 ± 178.9 | 0.208 | 0.099 |

| Fruits (g/day) | 184.0 ± 203.7 | 180.2 ± 199.9 | 183.6 ± 203.5 | 0.350 | 0.197 |

| Citrus | 43.9 ± 63.2 | 37.2 ± 52.1 | 35.0 ± 45.8 | 0.243 | 0.266 |

| Sweets (g/day) | 29.0 ± 48.8 | 31.4 ± 76.6 | 28.7 ± 45.2 | 0.771 | 0.879 |

| Fat-food (g/day) | 4.6 ± 4.8 | 4.5 ± 4.5 | 5.1 ± 5.7 | 0.402 | 0.644 |

| Alcohol (g/day)§ | 15.9 ± 21.9 | 19.4 ± 28.6 | 25.4 ± 47.2 | 0.138 | 0.336 |

| Tobacco (cigarettes/day)§ | 16.0 ± 8.8 | 16.3 ± 8.5 | 17.0 ± 9.7 | 0.611 | 0.513 |

Dietary variables are presented as the energy-adjusted mean ± standard deviation. Subjects with AVI/AAV diplotype were excluded from the analyses because of limited numbers (n = 2).

*Number of subjects (case, control).

†,‡Mean intake of subjects with each diplotype was compared without adjustments (p1) or after adjusting for sex, age, body mass index, smoking and drinking status, regular exercise and Helicobacter pylori infection (p2) at the 95% confidence level.

§Mean alcohol and tobacco consumption was computed from group of subjects only ex- and current drinkers and smokers.

Association between TAS2R38 diplotype and gastric cancer risk

Statistical analyses provided evidence that TAS2R38 genetic variants are clearly associated with gastric cancer risk, although the variants did not influence dietary intake (Table 4). All three heterozygous genotypes and the PAV/AVI diplotype increased the risk for gastric cancer. The prevalence of PAV/AVI was 54.1% for cases and 46.0% for controls, thus generating an odds ratio (OR) of 1.392 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.089–1.780). A logistic regression model that considered potential confounders also supported the increased risk for gastric cancer with PAV/AVI diplotype (OR: 1.513; 95% CI: 1.148–1.994).

Table 4. TAS2R38 variants and diplotypes and the association with gastric cancer risk.

| Model 1 OR (95% CI)* | P | Model 2 OR (95% CI)† | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A49P | ||||

| PP | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | ||

| PA | 1.392 (1.089–1.780) | 0.005 | 1.515 (1.149–1.996) | 0.001 |

| AA | 1.025 (0.733–1.435) | 0.361 | 0.983 (0.676–1.429) | 0.190 |

| V262A | ||||

| AA | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | ||

| AV | 1.404 (1.098–1.794) | 0.003 | 1.525 (1.157–2.009) | 0.001 |

| VV | 0.995 (0.709–1.396) | 0.261 | 0.957 (0.656–1.395) | 0.140 |

| I296V | ||||

| VV | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference) | ||

| VI | 1.404 (1.098–1.794) | 0.003 | 1.525 (1.157–2.009) | 0.001 |

| II | 0.995 (0.709–1.396) | 0.261 | 0.957 (0.656–1.395) | 0.140 |

| Diplotype | ||||

| PAV/PAV | 1.000 (reference) | 1.000 (reference)‡ | ||

| PAV/AVI | 1.392 (1.089–1.780) | 0.004 | 1.513 (1.148–1.994) | 0.001 |

| AVI/AVI | 0.995 (0.709–1.396) | 0.272 | 0.956 (0.656–1.394) | 0.145 |

Subjects with AVI/AAV diplotype were excluded from the analyses because of limited numbers (n = 2).

*Model 1: crude OR and 95% CI.

†Model 2: ORs computed after adjusting for sex, age, body mass index, smoking and drinking status, regular exercise and Helicobacter pylori infection (please refer to Supplementary Table S2 for the effect of potential confounders). OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

Genetic variants in human TAS2R38 bitter taste receptor alter individual sensitivity to bitter taste and food intake. Therefore, these variants may be further associated with diet-related disease risk. The present study examined whether TAS2R38 genetic variants influence dietary intake and whether they are associated with the risk of gastric cancer in Koreans.

The findings showed that the TAS2R38 diplotype did not predict the dietary intake of the examined foods, alcohol consumption or tobacco smoking, regardless of gastric cancer phenotype. A few earlier studies examined the association between TAS2R38 diplotype and food and alcohol intake and smoking behaviour; however, the results are inconclusive17,35,36. This inconsistent association between TAS2R38 diplotypes and dietary food intake might stem from the use of natural and artificial condiments in the study population17. Although cruciferous vegetables constitute a large proportion of the vegetables consumed by Koreans, the majority include Kimchi and/or other pickled dishes with a large amount of seasoning, including sodium, garlic, hot pepper, ginger, vinegar, and fish sauce. These strongly flavoured condiments may mask the bitter taste of cruciferous and other vegetables, and therefore, the TAS2R38 diplotype may not be associated with the dietary intake of such vegetables. Thus, continuous intake of foods containing large amounts of sugar and fat may also impact the sensitivity to sweet and fatty food as well as to fruits, which may have caused the insignificant difference in the intake of these foods among TAS2R38 diplotype groups3,36. Furthermore, increased frequency of dining out and the use of artificial flavour enhancers, such as monosodium glutamate, may mask taste and alter the sensitivity to the native tastes of foods. Finally, the relatively small size of the study population may have limited the potential associations between TAS2R38 diplotypes and dietary food intake (The power of the general linear models was relatively low across the examined dietary variables. See Supplementary Table S1).

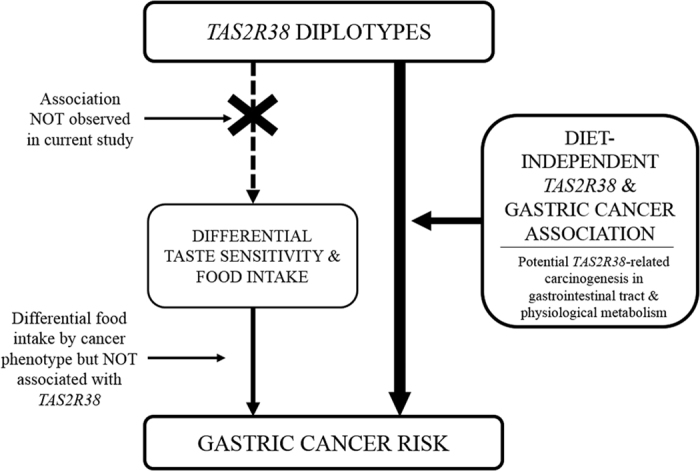

Although TAS2R38 diplotype was not associated with food intake, TAS2R38 genetic variants and diplotype predicted gastric cancer risk. This diet-independent TAS2R38-cancer association may suggest that genetic variation in TAS2R38 involved in gastric carcinogenesis not simply via altered food intake but through other potential mechanisms (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Simplified diagram of the hypothesized (dotted arrow) and observed (solid arrow) association between the TAS2R38 gene and gastric cancer risk in the present study.

Earlier studies hypothesized that individuals with PAV/PAV diplotype (tasters) may avoid the bitter taste of cruciferous vegetables and may have a greater risk for cancer compared with the AVI/AVI group (non-tasters). However, studies have reported a trend toward an increased risk for colorectal cancer independent of dietary food intake in the AVI/AVI group, not the PAV/PAV group17,18. The precise mechanism for this phenomenon has not yet been verified. However, one diet-independent hypothesis implicates TAS2R38 diplotype as a biomarker for gastrointestinal function18. The variant protein may give rise to the insufficient ability to neutralize and expel potentially harmful chemicals from the gastrointestinal tract. Therefore, the AVI/AVI diplotype may increase the risk for colorectal cancer and could be a biomarker for gastrointestinal function7. This biomarker-related hypothesis possibly supports the diet-independent association between TAS2R38 and gastric cancer risk in the current study18,37.

Unlike previous studies, our data suggested that the heterozygous TAS2R38 diplotype (PAV/AVI), not the homozygous AVI/AVI genotype, increased the risk for gastric cancer. A previous study demonstrated that the TAS2R38 receptor encoded by the PAV/PAV variant was only activated by bitter compounds containing a thiourea moiety; other varieties of bitter chemicals minimally activated the protein37. The TAS2R38 protein encoded by the AVI/AVI variant rarely responds to PTC and PROP. However, AVI transcript expression was clearly evident, and individuals with the homozygous AVI variant react to other bitter tastes as strongly as individuals with the homozygous PAV variant37. This observation may support the notion that the AVI variant not only conveys impaired receptor activity but also potentially mediates the independent reaction to other unknown bitter chemicals37. Consistent with these results, both homozygous diplotype receptors (PAV/PAV or AVI/AVI) may be fully capable of responding to each agonist and may thus possess a greater ability to initiate protective mechanisms against potentially toxic chemicals in the gastrointestinal tract. In contrast, compared with homozygotes, the PAV/AVI heterozygous protein may be less active in sensing agonist molecules. Therefore, the gastrointestinal system of individuals harbouring the PAV/AVI diplotype may experience prolonged exposure to potentially carcinogenic chemicals and be at a higher risk for gastric cancer. Findings from studies on chemo-sensitivity and TAS2R38 diplotype possibly support this hypothesis. Individuals with the PAV/AVI diplotype generally exhibit intermediate sensitivity to bitter-tasting molecules5,37. Furthermore, allele-specific mRNA expression of the PAV/AVI diplotype was evident, and the expression level of each allele was reduced compared with the PAV and AVI homozygous diplotypes37.

Additionally, because gastric carcinogenesis is a multifactorial process, alterations in other TAS2R38-related physiological metabolism processes due to genetic polymorphism may be associated with gastric carcinogenesis. For example, TAS2R mRNA expression has been observed in various types of blood leukocytes, which may suggest TAS2Rs contribute to the cellular immune response by differentiating foodborne substances38. TAS2R38 protein in ciliated epithelial cells was reported to regulate innate immunity via the production of nitric oxide39, which is critical for the initiation and progression of gastric cancer40. Therefore, alterations in immune responses and/or nitric oxide production related to TAS2R38 variants may modify gastric cancer risk if TAS2R38 mediates such defence mechanisms in the gastrointestinal mucosal epithelia. In addition, although the precise mechanism is not fully understood, the TAS2R38 protein functions in energy metabolism and glucose homeostasis7,35,41. The decisive components in these metabolic pathways, including insulin, insulin-like growth factor (IGF), IGF-binding protein and insulin resistance, are also involved in regulating cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis42. Therefore, the association between TAS2R38 variants and these factors may be related to predisposition to gastric cancer. However, because little evidence is available to support those putative correlations, larger epidemiological studies and further investigations are required to verify the underlying mechanisms for the TAS2R38-gastric cancer relationship.

The results of the present study suggest interesting associations surrounding TAS2R38 bitter taste receptor gene and gastric cancer risk; however, some limitations exist. The findings were derived from a relatively small Korean population, and a limited amount of literature is available to conjecture the association between TAS2R38 and the gastric carcinogenic mechanism. Although we investigated a myriad of foods and consumer goods, other foods and genes linked to TAS2R38 may contribute to gastric cancer susceptibility. Despite these limitations, this study is worthy of consideration given that TAS2R38 is centred in human diet behaviour and physiological metabolism. Furthermore, this is the first TAS2R38 study that covers the full repertoire of genetic variants, dietary intake and clinical phenotype in understanding gastric cancer aetiology.

In summary, the PAV/AVI diplotype of the TAS2R38 gene increased the risk for gastric cancer, but genetic variation did not influence dietary intake. TAS2R38 may play a decisive role in gastric carcinogenesis in Koreans.

Methods

Subjects

This case-control study was part of a gastric cancer research project at the National Cancer Center (NCC), Korea. The details of the study population were previously described elsewhere23,43. Participants were recruited at the NCC Hospital between March 2011 and December 2014. Cases were clinically diagnosed by gastroenterology specialists as having early gastric cancer that was histologically confirmed by endoscopic biopsy at the Center for Gastric Cancer. Patients who had diabetes mellitus, severe systemic or mental disease, a history of any other cancer within the past five years or advanced gastric cancer were excluded from the study. Controls were enrolled from a health screening examination (a benefit program of the National Health Insurance) at the Center for Cancer Prevention and Detection in the same hospital. A total of 1,710 subjects (500 gastric cancer cases and 1,210 controls) agreed to participate in the study. In total, 1,585 individuals provided blood samples and were genotyped. The risk for gastric cancer related to TAS2R38 was estimated from these participants (n = 1,580; 449 gastric cancer cases and 1,131 controls) after excluding subjects whose genotype was not determined (n = 5). Of these subjects, individuals who did not provide dietary intake data (n = 45) or whose total energy intake was <500 kcal or >5,000 kcal (n = 11) were excluded from the study population due to the implausibility of the data. Therefore, the remaining 1,524 participants (1,101 controls and 423 cases) were analysed to determine the influence of TAS2R38 variants on dietary intake. All participants joined the research voluntarily, and written informed consent was obtained prior to study commencement. All the study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the NCC (IRB Number: NCCNCS-11-148), and all actual procedures involved in current study were conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the IRB, NCC.

Data Collection and Dietary Intake Analyses

Participants were requested to complete a self-administered questionnaire designed to collect information on demographics (e.g., age and gender), lifestyle (e.g., cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and regular physical activity) and medical history. Anthropometric data (e.g., height and weight) were obtained using the InBody 370 (Biospace, Seoul, Korea). Body mass index was computed as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters.

A validated food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) covering 106 food items was used to evaluate dietary intake44. The participants were asked to verify the frequency and portion size of each of the food items in the FFQ. Nine degrees of frequency (never or rarely, once a month, two or three times a month, once or twice a week, three or four times a week, five or six times a week, once a day, twice a day, or three times a day) and three portion sizes (small, medium, or large) are included in the FFQ to evaluate food intake over the last year. Dietary intake was evaluated using CAN-PRO 4.0 (Computer Aided Nutritional Analysis Program, The Korean Nutrition Society, Seoul, Korea). The dietary intake of the following nine classes of foods was of particular interest in the current study17: 1) total dietary fibre, 2) vegetables (all), 3) cruciferous vegetables (white radish, radish leaves, mustard, mustard leaves, napa cabbage, broccoli, cabbage and others), 4) dark green vegetables (curled mallow, chicory, pumpkin leaf, pine leaf, sweet potato vines, hot pepper, hot pepper leaf, perilla leaf, field dropwort, angelica, water parsley, chives, lettuce, iceberg lettuce, celery, spinach, mugwort, crown daisy, taro vine and others), 5) non-starchy vegetables (all vegetables excluding potato, sweet potato, soybean and green bean), 6) fruits (all), 7) citrus fruits (mandarin, cumquat, orange and orange juice), 8) sweets (honey, candy, sugar, syrup, chocolate, caramel, jam, sherbet, ice cream and soda)3 and 9) fat-foods (margarine, butter, beef fat, sesame oil, coffee creamer and soybean oil)45. Additionally, the consumption of alcohol (beer, hard liquor, Korean spirits, Korean rice wine, wine and fruit liquor) and tobacco (cigarettes/day), which were previously reported to be associated with taste receptor gene variants, were also investigated35,36.

Genotyping and Diplotype Computation

An Axiom® Exome 319 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) containing 318,983 loci of single nucleotide polymorphisms was utilized to determine the TAS2R38 genotypes of subjects. The call rate for A49P, V262A and I296V TAS2R38 variants was >95% in both the case and control groups, and all three variants were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the controls. The TAS2R38 diplotypes were computed using FAMHAP based on maximum-likelihood estimates, which were generated using the expectation-maximization algorithm (http://famhap.meb.uni-bonn.de/)46,47.

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square tests and Student’s t-tests were applied to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively, by gastric cancer phenotype. Variables for dietary consumption were adjusted for total energy intake using Willett’s residual method48. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the difference in food intake among the major three diplotypes of TAS2R38. Two ANOVA models were established, without (crude) or with adjustments for confounding factors. Logistic regression models without (crude) or with adjustments for potential confounders were applied to determine the ORs and 95% CIs for the associations between TAS2R38 genetic variants and gastric cancer risk. All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All reported p-values were two-tailed at the 95% confidence level.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Choi, J.-H. et al. Genetic Variation in the TAS2R38 Bitter Taste Receptor and Gastric Cancer Risk in Koreans. Sci. Rep. 6, 26904; doi: 10.1038/srep26904 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (no. NRF-2015R1C1A1A02036717) and a grant from the NCC, Republic of Korea (no. 1410260).

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.-H.C. designed the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. J.L. conducted the research. Y.-W.K., K.W.R. and I.J.C. contributed to data collection. J.K. provided critical review and had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Duffy V. B. Variation in oral Sensation: implications for diet and health. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 23, 171–177 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A. & Gomez-Carneros C. Bitter taste, phytonutrients, and the consumer: a review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 72, 1424–1435 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell M. et al. Genetic variation in the hTAS2R38 taste receptor and Food consumption among Finnish adults. Genes Nutr. 9, 433 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A., Henderson S. A., Shore A. B. & Barratt-Fornell A. Sensory responses to 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) or sucrose solutions and food preferences in young women. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 855, 797–801 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucock M. et al. TAS2R38 bitter taste genetics, dietary vitamin C, and both natural and synthetic dietary folic acid predict folate status, a key micronutrient in the pathoaetiology of adenomatous polyps. Food Funct. 2, 457–465 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson M. D. et al. Association between 6-N-propylthiouracil (prop) bitterness and colonic neoplasms. Dig. Dis. Sci. 50, 483–489 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozengurt E. Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. I. Bitter taste receptors and alpha-gustducin in the mammalian gut. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver. Physiol. 291, G171–G177 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens M., Gunn H. C., Ramos P. C., Meyerhof W. & Wooding S. P. Genetic, functional, and phenotypic diversity in TAS2R38-Mediated bitter taste perception. Chem. Senses. 38, 475–484 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipchock S. V., Mennella J. A., Spielman A. I. & Reed D. R. Human bitter perception correlates with bitter receptor messenger RNA expression in taste cells. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98, 1136–1143 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soranzo N. et al. Positive selection on a high-sensitivity allele of the human bitter-taste receptor TAS2R16. Curr. Biol. 15, 1257–1265 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternini C., Anselmi L. & Rozengurt E. (2008) Enteroendocrine cells: a site of ‘taste’ in gastrointestinal chemosensing. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 15, 73–78 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U. K. et al. Positional cloning of the human quantitative trait locus underlying taste sensitivity to phenylthiocarbamide. Science 299, 1221–1225 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy V. B. et al. Bitter receptor Gene (TAS2R38), 6-n-propylthiouracil (prop) bitterness and alcohol intake. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 28, 1629–1637 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacerdote C. et al. Lactase persistence and bitter taste response: instrumental variables and Mendelian randomization in epidemiologic studies of dietary factors and cancer risk. Am. J. Epidemiol. 166, 576–581 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. C. et al. Functional variants in TAS2R38 and TAS2R16 influence alcohol consumption in high-risk families of African-American origin. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 31, 209–215 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K. & Kaur G. K. Ptc bitter taste genetic polymorphism, Food choices, physical growth in body Height and body fat related traits among adolescent girls from Kangra Valley, Himachal Pradesh (India). Ann. Hum. Biol. 41, 29–39 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schembre S. M., Cheng I., Wilkens L. R., Albright C. L. & Le Marchand L. Variations in bitter-taste receptor genes, dietary intake, and colorectal adenoma risk. Nutr. Cancer 65, 982–990 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrai M. et al. Association between TAS2R38 Gene polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk: A Case-Control Study in Two Independent Populations Of Caucasian Origin. PLos ONE 6, e20464 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. Y., Noh S. H. & Cheong J. H. Evolution of gastric cancer treatment: from the golden Age of surgery to an era of Precision medicine. Yonsei Med. J. 56, 1177–1185 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eom B. W. et al. Prediction model for gastric cancer incidence in Korean population. PLos One 10, e0132613 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre L. A. et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 65, 87–108 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K. W. et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2012. Cancer Res. Treat. 47, 127–141 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo H. D. et al. Dietary flavonoids and gastric cancer risk in a Korean population. Nutrients 6, 4961–4973 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo H. D. & Kim J. Dietary flavonoid intake and risk of stomach and colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 19, 1011–1019 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steevens J., Schouten L. J., Goldbohm R. A. & van den Brandt P. A. Vegetables and fruits consumption and risk of esophageal and gastric cancer subtypes in the Netherlands Cohort Study. Int. J. Cancer 129, 2681–2693 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q. et al. Intakes of folate, methionine, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 with risk of esophageal and gastric cancer in a large cohort study. Br. J. Cancer 110, 1328–1333 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wie G. A. et al. Red meat consumption is associated with an increased overall cancer risk: a prospective cohort Study in Korea. Br. J. Nutr. 112, 238–247 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H. et al. Red and processed meat intake is associated with higher gastric cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiological observational studies. PLos One 8, e70955 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S. H., Li Y. H., Leung K., Huang C. Y. & Wang X. R. Salt processed food and gastric cancer in a Chinese population. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 15, 5293–5298 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Elia L., Galletti F. & Strazzullo P. Dietary salt intake and risk of gastric cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. 159, 83–95 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler N. E., Boyce W. T., Chesney M. A., Folkman S. & Syme S. L. Socioeconomic inequalities in health. No easy solution. JAMA 269, 3140–3145 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo L. C., Espinosa de los Monteros K. & Shivpuri S. Socioeconomic status and health: what is the role of reserve capacity? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 18, 269–274 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampuré A. et al. Sociodemographic, psychological, and lifestyle characteristics are associated with a liking for salty and sweet tastes in French adults. J. Nutr. 145, 587–594 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B. In silico gene discovery In Clinical bioinformatics, Vol. 141 (ed. Walker J. M.) 1–12 (Humana Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Keller M. et al. TAS2R38 and its influence on smoking behavior and glucose homeostasis in the German Sorbs. PLos One 8, e80512 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes J. E. et al. Allelic variation in TAS2R bitter receptor genes associates with variation in sensations from and ingestive behaviors toward common bitter beverages in adults. Chem. Senses. 36, 311–319 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bufe B. et al. The molecular basis of individual differences in phenylthiocarbamide and propylthiouracil bitterness perception. Curr. Biol. 15, 322–327 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malki A. et al. Class I odorant receptors, TAS1R and TAS2R taste receptors, are markers for subpopulations of circulating leukocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 97, 533–545 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. J. & Cohen N. A. Taste receptors in innate immunity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 72, 217–236 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhari S. K., Chaudhary M., Bagde S., Gadbail A. R. & Joshi V. Nitric oxide and cancer: a review. World J. Surg. Oncol. 11, 118 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson C. D. et al. Bitter taste receptors influence glucose homeostasis. PLos One 3, e3974 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnagnarella P., Gandini S., La Vecchia C. & Maisonneuve P. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 87, 1793–1801 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W. et al. Dietary folate, one-carbon metabolism-related genes, and gastric cancer risk in Korea. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 60, 337–345 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn Y. et al. Validation and reproducibility of Food frequency questionnaire for Korean genome epidemiologic study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 61, 1435–1441 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafaie Y., Koelliker Y., Hoffman D. J. & Tepper B. J. Energy intake and diet selection during buffet consumption in women classified by the 6-N-propylthiouracil bitter taste phenotype. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98, 1583–1591 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T. & Knapp M. Maximum-likelihood estimation of haplotype frequencies in nuclear families. Genet. Epidemiol. 27, 21–32 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold C. & Becker T. Genetic association analysis with fFAMHAP: a major program update. BioInformatics 25, 134–136 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett W. C., Howe G. R. & Kushi L. H. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 65, 1220S–1228S, discussion 1229S (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.