Abstract

Background:

Urogenital mycoplasmas are potentially pathogenic species causing genitourinary tract infections that may be initially asymptomatic but can progress and lead to severe complications and threaten reproductive health. However, the overall prevalence rate of this bacterium and its probable impacts on fertility potential have yet to be determined.

Methods:

We searched both English and Persian electronic databases using key words such as “Mycoplasma,” “Ureaplasma,” “M. hominis,” “M. genitalium,” “U. urealyticum,” “U. parvum,” “prevalence,” and “Iran”. Finally, after some exclusion, 29 studies from different regions of Iran were included in our study, and a meta-analysis was performed on collected data.

Results:

Urogenital mycoplasmas prevalence for women and men was high and ranged from 2%–40.5% and 2%–44.3%, respectively. The pooled prevalence in the male population was 11.1% (95% CI, 7.4%–16.4%) and in female was 12.8% (95% CI, 9.8%–16.5%). The prevalence of these bacteria was significantly higher in infertile men compared with that in fertile men. A high level of heterogeneity was observed for both men (I2 = 92.4%; P<0.001) and women (I2 = 93.3%; P<0.001). Some evidence for publication bias was observed in both men [Egger’s test (two-tailed P=0.0007), and Begg’s test (two-tailed P=0.0151)] and women [Egger’s test (two-tailed P=0.0006), and Begg’s test (two-tailed P=0.0086)] analysis.

Conclusion:

Since urogenital mycoplasmas may play a role in male infertility, screening strategies, particularly for asymptomatic individuals, and treatment of infected ones, which can reduce consequent complications, looks to be necessary.

Keywords: Urogenital mycoplasmas, Prevalence, Frequency, Fertility potential, Iran

Introduction

Mycoplasmas are in a class of bacteria designated as mollicutes, which lack cell walls, and this characteristic along with their minute size separates them from other bacteria. Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, U. parvum, and M. genitalium are potentially pathogenic species frequently isolated from the genitourinary tract and are known as urogenital mycoplasmas ( 1 ). These bacteria together with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis are considered among the most prevalent sexually transmitted pathogens that have a global distribution ( 2 – 3 ). Urogenital mycoplasmas are associated with some symptomatic and asymptomatic genitourinary tract infections in both males and females; for example, they may cause Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) resulting in damage to the fallopian tubes, which may lead to ectopic pregnancy. These bacteria are also associated with non-gonococcal urethritis, endometritis, bacterial vaginosis, preterm delivery, postpartum, or post-abortal fever, as well as perinatal disorders such as low birth weight and neonatal bacteremia/meningitis ( 4 – 12 ). The effects of urogenital mycoplasmas on spermatozoa and seminological variables and their role in male or female infertility are controversial and remain unclear ( 13 – 18 ); however, there is some evidence that M. genitalium may cause female infertility, particularly tubal infertility ( 19 – 20 ).

Some of investigators believe that mycoplasmas are genitourinary tract commensals; thus, one of the important problems concerning urogenital mycoplasmas is that there are many clinically asymptomatic carriers silently colonized by these bacteria while these microorganisms are potentially pathogenic and may play a role in urogenital tract infection or affect fertility potential as an opportunistic pathogen, under certain circumstances ( 21 – 25 ). Nevertheless, the majority of asymptomatic infections may remain undetected and consequently untreated.

In Iran, to date, several studies have reported the frequency of urogenital mycoplasmas infections in males and/or females, in which the frequency of these pathogens varies significantly in different surveys. However, most of these studies are local and limited to an individual hospital or a special province or city, and a comprehensive analysis of the overall prevalence of these bacteria, which may be useful to set up control programs for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), has not yet been performed.

Thus, the present study was designed to determine the prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas infections in Iran using a systematic review and meta-analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement ( 26 ).

Methods

Search strategies

We searched electronic databases, including OVID databases, PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar for the prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas infections in Iran from Nov 1999 to Feb 2015. The search was restricted to original articles published in English that present the prevalence, frequency, or incidence of urogenital mycoplasmas infections in Iranian males or females using the following keywords with the help of Boolean operators (AND, OR): “Mycoplasma”, “Ureaplasma”, “urogenital mycoplasmas”, “genital mycoplasmas”, “M. hominis”, “M. genitalium”, “U. urealyticum”, “U. parvum”, “prevalence”, “incidence”, “frequency”, “epidemiology”, and “Iran” . We additionally searched for other urogenital tract associated mycoplasma species using keywords: “M. fermentans”, “M. penetrans”, “M. primatum”, and “M. spermatophilum”. In addition to articles published in English, we also looked for relevant articles in Persian published and indexed in Iranian databases, such as Scientific Information Database (SID) (http://www.sid.ir/), Magiran (http://www.magiran.com/), Irandoc (http://www.irandoc.ac.ir/), Regional Information Center for Science and Technology (RICST) (http://en.ricest.ac.ir/), and Iranian National Library (http://www.nlai.ir/), with similar strategies and related appropriate Persian keywords. References from reviewed articles were also searched for more information.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included studies were all original articles presenting cross-sectional, case–control, or cohort studies on the prevalence of symptomatic or asymptomatic urogenital mycoplasmas infections in Iranian males/females in which the methods for diagnoses were molecular amplification techniques, such as PCR, PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP), and multiplex PCR. Excluded studies were: 1) those that used detection methods other than nucleic acid amplification techniques (NAAT), including culture or serological methods, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or immunofluorescence (IF), 2) studies reporting prevalence of myco-plasma species other than urogenital mycoplasmas such as M. pneumoniae, 3) studies that included mycoplasma infections in organs or body sites other than the genitourinary tract, and 4) studies reporting the prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas at the genus level and not the species of mycoplasma. Review articles, congress abstracts, studies reported in languages other than English or Persian, meta-analyses or systematic reviews, duplicate publications of the same study, and articles available only in abstract form were also excluded.

Data extraction and definitions

Variables and information extracted from each study included first author’s name, year of publication, study setting, geographical location, participants characteristic, gender, specimen type, number of patients investigated (sample size), bacterial species investigated, type of detection method, and number of positive samples. The articles were reviewed, and relevant data were extracted by two authors independently. Disagreements between reviewers were discussed to obtain consensus.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software Version 2.0 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). The prevalence was reported by 95% confidence interval (CI). Cochrane Q-statistic test and I2 test were performed to estimate heterogeneity between studies, and the random effect model was chosen to estimate the average prevalence because of its conservative summary estimate and because in all calculations (except one in which the fixed effect model was used), I2 was above 50%. To assess possible publication bias, a funnel plot along with Begg’s rank correlation and Egger’s weighted regression methods were used. Two-tailed P<0.05 was considered indicative of a statistically significant publication bias.

Results

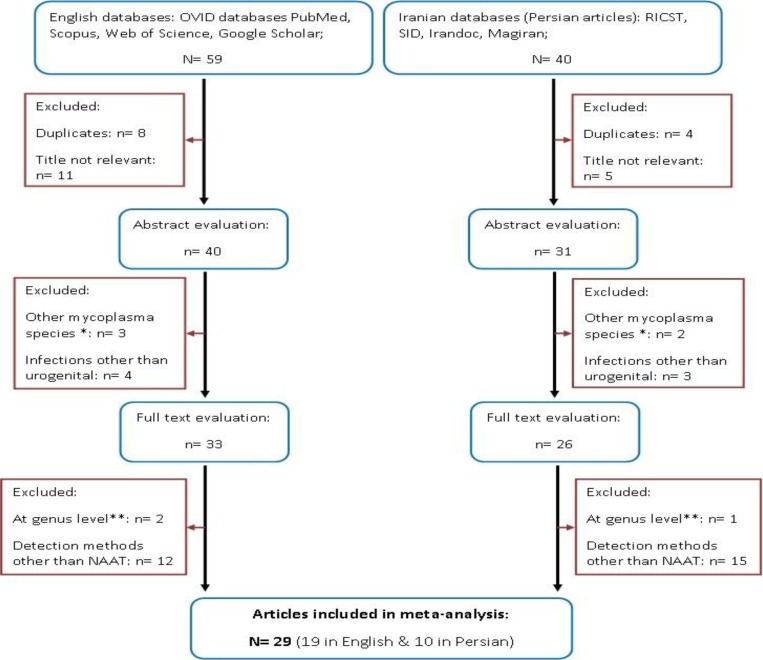

A total of 99 articles (59 in English and 40 in Persian) were collected. Through the first screening, 28 articles were excluded on the basis of the title evaluation. After the second assessment, 12 papers were discarded because they had reported mycoplasma infections in organs or body sites other than the genitourinary tract, or investigated other mycoplasma species (such as M. pneumonia). Finally, after full-text evaluation, 30 studies were ruled out on the basis of their detection methods, or because they had reported the prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas at the genus level and not specified the species, and therefore 29 articles (19 in English and 10 in Persian) published between 2005 and 2015 were selected and included in our analysis ( Fig. 1 and Table 1 ).

Fig. 1:

Flow chart of the literature search, systematic review and study selection. *Studies reporting prevalence of mycoplasma species other than urogenital mycoplasmas, such as M. pneumonia; ** surveys reporting the prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas at genus level

Table 1:

Studies included in meta-analysis after final evaluation

| Reference | Published year | Province/City | Sex | Sample | Bacteria spp. | Mean age | Total number of participants | Events number | Events rate (%) (95% CI) | Disease, Complication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ( 38 ) | 2005 | Tehran | F | Endocervical swabs | MH | 36 | 312 | 50 | 16.02 | Infertility |

| ( 39 ) | 2005 | Tehran | F | Endocervical swabs | UU | 32 | 312 | 74 | 23.7 | Infertility |

| ( 40 ) | 2006 | Tehran | F | Endocervical swabs | MH | 32 | 377 | 56 | 14.9 | Infertility |

| ( 41 ) | 2007 | Tehran | M | Semen | MH UU |

35 | 100 | 3 17 |

3 17 |

Infertility |

| ( 42 ) | 2007 | Tehran | M | Semen | UU | 36 | 200 | 15 | 7.5 | Fertile & infertile men |

| ( 43 ) | 2007 | Tehran | F | Endocervical swabs | UU | 32 | 377 | 85 | 22.5 | Infertility |

| ( 44 ) | 2007 | Tehran | M | Semen | MH UU |

35 | 200 | 40 12 |

20 6 |

Asymptomatic infertile men |

| ( 45 ) | 2008 | Tehran | M | Semen | UU | 35 | 246 | 26 | 10.6 | Fertile and infertile men |

| ( 46 ) | 2008 | Tehran | F | Endocervical swabs | MH | 31 | 312 | 48 | 15.4 | Infertile women |

| ( 47 ) | 2009 | Tehran | F | Endocervical swabs | MH UU MG |

31.9 | 210 | 42 93 11 |

20 44.3 5.2 |

Genital infection |

| ( 48 ) | 2009 | Tehran | M | Semen | UU UP |

35 | 200 | 10 5 |

5 2.5 |

Fertile & infertile men |

| ( 49 ) | 2010 | Tehran | M | Semen | MH UU |

38.5 | 220 | 34 89 |

15.5 40.5 |

Infertility |

| ( 50 ) | 2011 | Gorgan | F | Vaginal discharge | MH UU |

34 | 235 | 18 18 |

7.7 7.7 |

Vaginitis & Vaginosis |

| ( 51 ) | 2011 | Sabzevar | F | FVU | MG | 31 | 196 | 4 | 2.04 | Pregnant women |

| ( 52 ) | 2012 | Tehran | F | Endocervical swabs | MH UU |

39 | 191 | 52 58 |

27.2 30.4 |

Symptomatic urogenital infection |

| ( 53 ) | 2012 | Ahvaz | F | Cervicovaginal swab & FVU | MH UU |

34.5 | 265 | 18 28 |

6.8 10.6 |

Symptomatic uro genital infection |

| ( 54 ) | 2013 | Kerman | M | Semen | MH | 33.5 | 58 | 13 | 22.4 | Infertility |

| ( 55 ) | 2013 | Tehran | M | Semen | MG | 34.7 | 120 | 15 | 12.5 | Infertility |

| ( 56 ) | 2013 | Tonekabon | F | vaginal secretions | MG | 30 | 44 | 10 | 22.7 | Pregnant women |

| ( 57 ) | 2013 | Tehran | M | FVU | MG | 33.5 | 200 | 14 | 7 | Symptomatic & Asymptomatic men |

| ( 58 ) | 2013 | Ahvaz | F | cervicovaginal swab & FVU | MH UU |

34.5 | 465 | 18 41 |

3.9 8.8 |

Genitourinary infections & healthy females |

| ( 59 ) | 2013 | Tehran | M | Prostate tissue | MG | ND | 200 | 4 | 2 | Prostatitis |

| ( 60 ) | 2014 | Sanandaj | F | Endocervical swabs | UU | 31 | 218 | 26 | 11.9 | Spontaneous abortion & normal pregnancy |

| ( 61 ) | 2014 | Kerman shah | F | Cervical swabs | MG | 32.5 | 223 | 11 | 4.9 | Cervicitis |

| ( 62 ) | 2014 | Sanandaj | F | Cervical swabs | MH UU MG |

27 | 104 | 3 39 3 |

2.9 37.5 2.9 |

Infertility |

| ( 63 ) | 2014 | Kerman | F M |

Vaginal swabs | MH | ND ND |

100 100 |

18 15 |

18 15 |

Infertility |

| ( 64 ) | 2014 | Kerman | M F |

Semen Vaginal swab |

MG | 43 32.5 |

100 100 |

13 10 |

13 10 |

Infertility |

| ( 65 ) | 2014 | Tehran | F | Vaginal swab | MH UU |

28 | 165 | 25 25 |

15.2 15.2 |

Pregnant women |

| ( 66 ) | 2015 | Tehran | M | Semen | MG | ND | 45 | 17 | 37.8 | Fertile & Infertile men |

M: males; F: females; FVU: first void urine; MH: M. hominis; UU: U. urealyticum; MG: M. genitalium; UP: U. parvum;

ND: not determined.

Of the 29 articles included, 16 had studied the prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas infections in women, 11 in men, and two in both genders; four articles had studied only M. hominis; five only studied U. urealyticum, and eight only studied M. genitalium; nine articles had studied both M. hominis and U. urealyticum, two had investigated all three bacteria simultaneously, and there was only one article, explored U. urealyticum and U. parvum concurrently. We didn’t find any articles conducted in Iran about other urogenital tract associated mycoplasma species, including: M. fermentans, M. penetrans, M. primatum, and M. spermatophilum. Seven studies (five for men and two for women) were case–control (investigating the frequency of urogenital mycoplasmas in symptomatic– asymptomatic or fertile–infertile individuals, or in females having spontaneous abortion–normal pregnancy), and the rest were cross-sectional. The participants of the cross-sectional studies varied from asymptomatic and fertile individuals to symptomatic men and women having urogenital infections and complications including urethritis, prostatitis, cervicitis, vaginitis, vaginosis, and infertility.

The most commonly collected sample for detection was cervical or endocervical swabs for women, and semen samples for men, but other samples included vaginal discharge or vaginal swabs for women, prostate tissue for men, and first void urine for both genders. Five papers studied other agents in addition to urogenital mycoplasmas, such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Chlamydia trachomatis, simultaneously.

Most of the included studies had been performed in Tehran (n=18), which is the capital of Iran, in comparison with ones performed in western (n=3), southeastern (n=3), southwestern (n=2), northern (n=2), and northeastern (n=1) Iran. There were no studies conducted in central, southern or northwestern Iran. The prevalence of urogenital mycoplasma species in different regions of Iran is shown in Table 2 .

Table 2:

Prevalence of urogenital mycoplasma species in different regions of Iran

| Province (City) | Sex | Number of studies | Pooled prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas a(%) (range) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All species | MH | UU | MG | UP b | |||

| Tehran | M F |

14 12 |

10.1 (6.2–16.1) 19.6 (15.1–25.1) |

12.6 (6.7–22.6) 17.8 (14.5–21.6) |

11.5 (4.9–25.0) 26.4 (18.6–36.0) |

10.1 (3.3–26.9) 5.2 (2.9–9.2)* |

2.5 (1.0–5.9) NS |

| Kerman | M F |

3 2 |

16.2 (11.8–22.0) 13.9 (7.7–23.9) |

18.1 (12.0–26.3) 18.0 (11.6–26.8) * |

NS NS |

13.0 (7.7–21.1)

*

10.0 (5.5–17.6) * |

NS NS |

| Ahvaz | M F |

NS 4 |

7.2 (4.8–10.7) |

5.1 (2.9–8.8) |

9.5 (7.6–11.8) |

NS |

NS |

| Sanandaj | M F |

NS 4 |

9.2 (2.7–27.1) |

2.9 (0.9–8.6) * |

22.2 (6.2–55.1) |

2.9 (0.9–8.6) * |

NS NS |

| Kermanshah |

M F |

NS 1 |

4.9 (2.8–8.7) |

NS |

NS |

4.9 (2.8–8.7) * |

NS NS |

| Gorgan | M F |

NS 2 |

7.7 (5.6–10.4) |

7.7 (4.9–11.8) * |

7.7 (4.9–11.8) * |

NS |

NS NS |

| Tonekabon | M F |

NS 1 |

22.7 (12.7–37.3) |

NS |

NS |

22.7 (12.7–37.3) * |

NS NS |

| Sabzevar | M F |

NS 1 |

2.0 (0.8–5.3) |

NS |

NS |

2.0 (0.8–5.3) * |

NS NS |

| Total | M F |

17 27 |

11.1 (7.4–16.4) 12.8 (9.8–16.5) |

15.3 (10.6–21.7) 12.2 (8.8–16.8) |

11.5 (4.9–25) 18.9 (12.7–27.2) |

10.7 (4.6–22.9) 6.2 (3.1–11.8) |

2.5 (1.0–5.9) NS |

M: male; F: female; MH: M. hominis; UU: U. urealyticum; MG: M. genitalium; UP: U. parvum;

Based on random effects, (95% CI);

There was only one article among included studies, investigated the prevalence of U. parvum in males;

There was only one study among included articles in this gender, from this city; NS: no study conducted in this city, about this gender.

The age for women ranged from 14–60 yr (median: 37 yr), and for men from 17–65 yr (median: 41 yr). Three studies had not reported the ages of participants, and nine did not have age-stratified data. Moreover, most of the studies had no usable information on patients’ education and/or occupation. However, the highest prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas between the age groups belonged to 26–36 yr [38.2% (95% CI, range: 18.8%–57.6%)] and 25–35 yr [42.6% (95%CI, range: 33.7%–51.5%)] for men and women, respectively.

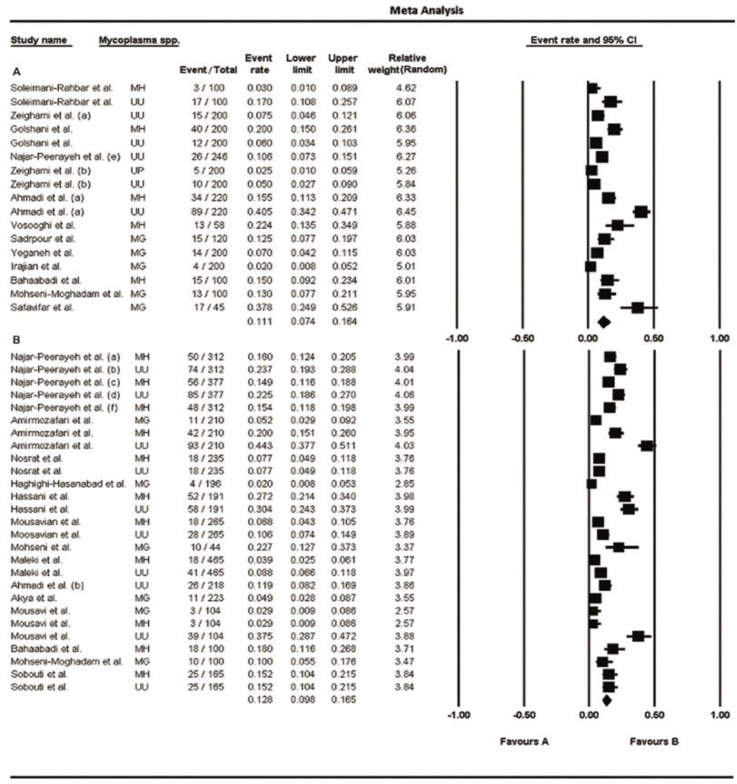

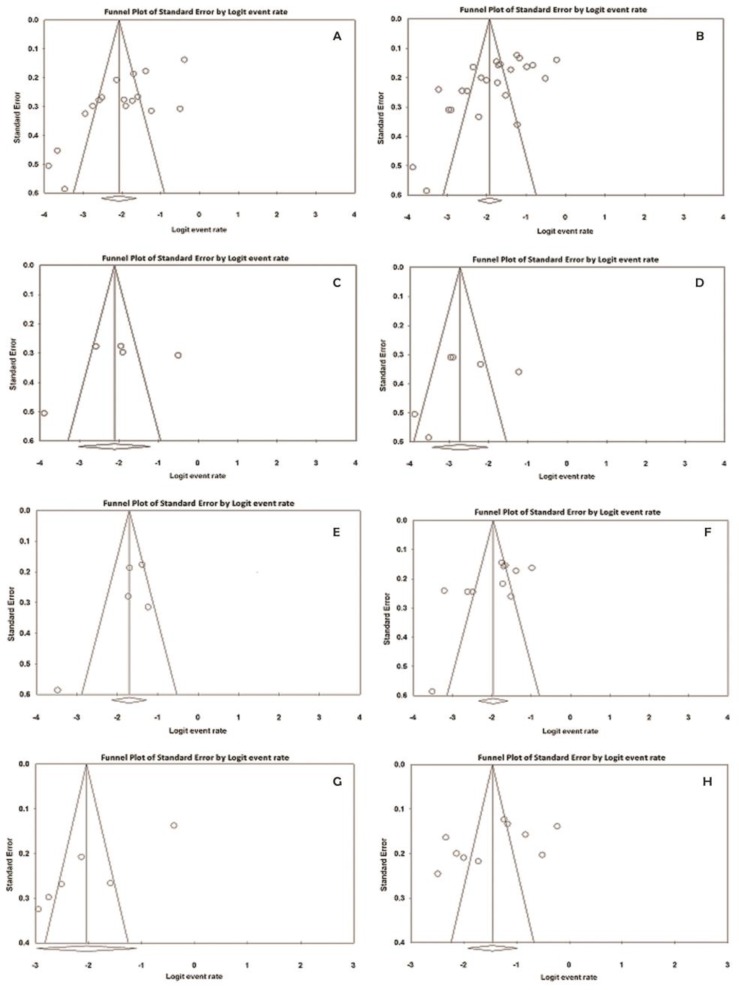

The numbers of participants (sample sizes) in the included studies varied from 45–246 in men and 44–465 in women. Prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas for men and women ranged from 2%–40.5% and 2%–44.3%, respectively (95% CI); the lowest rate was related to M. genitalium and the highest one was associated to U. urealyticum, in both genders. The pooled prevalence of these bacteria in men was 11.1% (95% CI, range: 7.4%–16.4%) and in women was 12.8% (95% CI, range: 9.8%–16.5%); moreover, a high level of heterogeneity was observed in men (I2 = 92.4%; P<0.001) and women (I2 = 93.3%; P<0.001). Fig. 2 (A and B) shows the forest plots of the meta-analyses of urogenital mycoplasmas prevalence for men and women, respectively. The funnel plots for meta-analysis of urogenital mycoplasmas prevalence in both men and women suggest some evidence of publication bias [ Fig. 4 (A and B)]; two-tailed P for Begg’s (based on continuity-corrected normal approximation) and Egger’s tests in men was 0.0151 and 0.0007, respectively, and in women was 0.0086 and 0.0006, correspondingly. We also analyzed the prevalence of each mycoplasma species in men and women, separately; the results are shown in Table 3 and corresponding forest and funnel plots are shown in Fig. 3 (A–F) and 4 (C–H), respectively. Some evidence of publication bias was observed in analysis of U. urealyticum prevalence in men (but not in women) [Egger’s test (two-tailed P=0.0085), and Begg’s test (two-tailed P=0.0242)]. Conversely, no evidence of publication bias was observed in the analysis of other mycoplasma species in men or women [ Table 3 and Fig. 4 (CH)]; however, the number of studies on the prevalence of M. genitalium in both men and women and prevalence of M. hominis and U. urealyticum in men was fewer than 10, and insufficient for an accurate conclusion.

Fig. 2:

Forest plots of the meta-analysis of urogenital mycoplasmas prevalence for men (A) and women (B). MH: M. hominis; UU: U. urealyticum; MG: M. genitalium; UP: U. parvum

Fig. 4:

Funnel plots of the meta-analysis of urogenital mycoplasmas prevalence. A and B: funnel plots for meta-analysis of urogenital mycoplasmas prevalence in men and women, respectively. C, E, and G: funnel plots for meta-analysis of prevalence of M. genitalium, M. hominis, and U. urealyticum, respectively in men. D, F, and H: funnel plots for meta-analysis of prevalence of M. genitalium, M. hominis, and U. urealyticum, respectively in women.

Table 3:

Meta-analysis results for prevalence of each mycoplasma species in included studies

| Mycoplasma species* | Number of studies | Sex | Prevalence rate (%) (95% CI) | Heterogeneity test | Begg’s test ***P-value (two-tailed) | Egger’s test **** P-value (two-tailed) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Pooled ** (range) | ||||||||

| a | b | |||||||||

| I2 (%) | P-value | |||||||||

| M. genitalium | 5 | M | 2.0 | 37.8 | 10.7 (4.6–22.9) | 90.6 | <0.001 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| 6 | F | 2.0 | 22.7 | 6.2 (3.1–11.8) | 81.6 | <0.001 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.5 | |

| M. hominis | 5 | M | 3.0 | 22.4 | 15.3 (10.6–21.7) | 70.4 | 0.009 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| 11 | F | 2.9 | 27.2 | 12.2 (8.8–16.8) | 89.5 | <0.001 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.04 | |

| U. urealyticum | 6 | M | 5.0 | 40.5 | 11.5 (4.9–25) | 96.1 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.009 |

| 10 | F | 7.7 | 44.3 | 18.9 (12.7–27.2) | 95.0 | <0.001 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | |

| All species | 17 | M | 2.0 | 40.5 | 11.1 (7.4–16.4) | 92.4 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.02 | <0.001 |

| 27 | F | 2.0 | 44.3 | 12.8 (9.8–16.5) | 93.3 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.009 | <0.001 | |

M: male; F: female; Min: minimum; Max: maximum; a: Kendall’s tau without continuity correction; b: Kendall’s tau with continuity correction.

There was only one article studied the prevalence of U. parvum and reported its prevalence to be 2% and 3% in fertile and infertile men, respectively;

Pooled prevalence (based on random effects);

Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation;

Egger’s regression intercept.

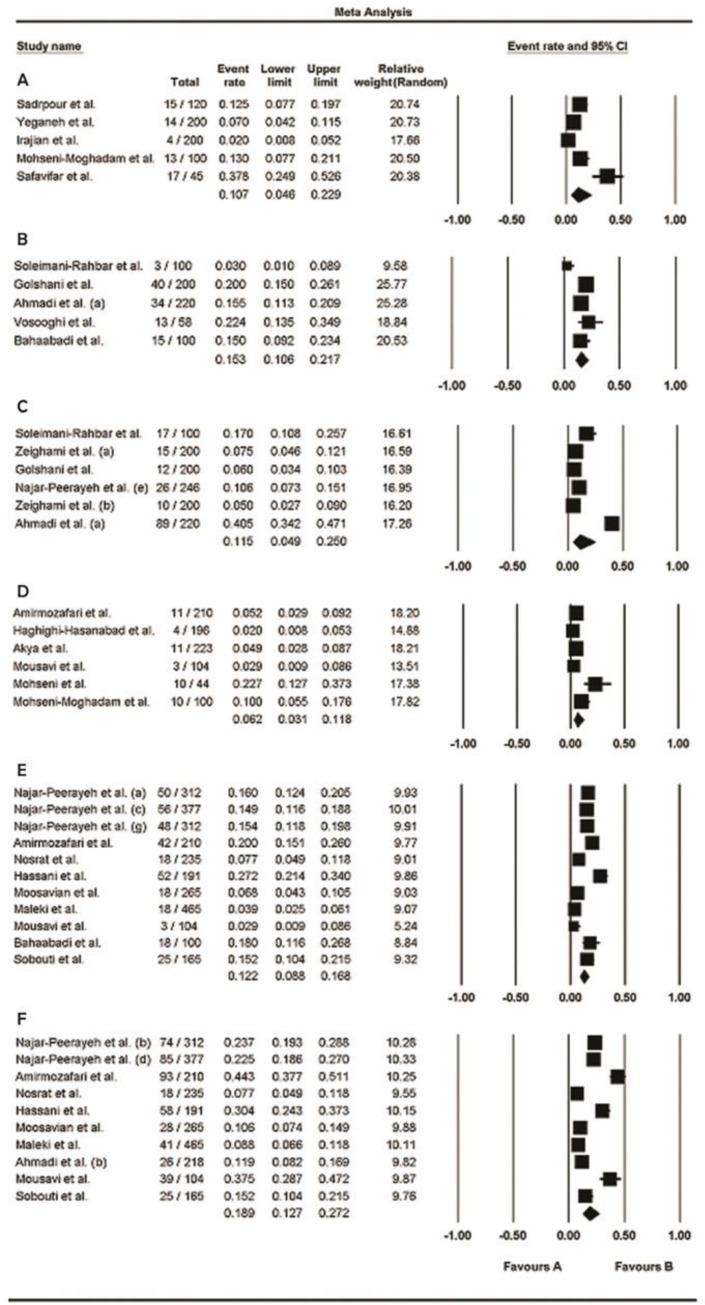

Fig. 3:

Forest plots of the meta-analysis of the prevalence of each mycoplasma species. A, C, and E: meta-analysis of prevalence of M. genitalium, M. hominis, and U. urealyticum, respectively in men. B, D, and F: meta-analysis of prevalence of M. genitalium, M. hominis, and U. urealyticum, respectively in women

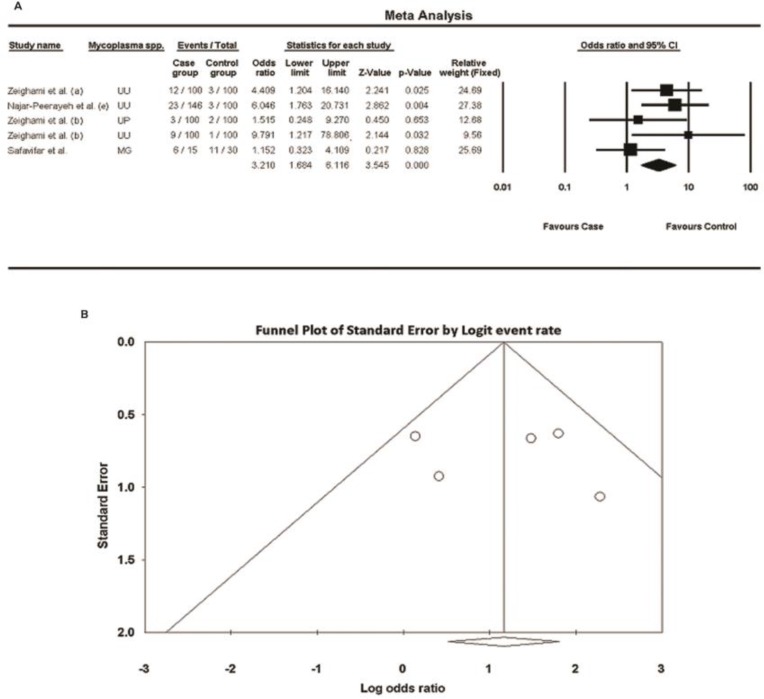

There were only five case–control studies among the included articles investigated the prevalence of some urogenital mycoplasma species in both fertile and infertile men; the forest plot of meta-analysis showed that the odds ratios for all these studies were above 1, and P values for three surveys were below 0.05 ( Fig. 5A ), indicating that the prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas was significantly higher in the case group (infertile men) compared with that in the control group (fertile men); as I2 was 27.2% (below 50%), the fixed effect model was used; however, the number of studies was fewer than 10, and insufficient for an accurate conclusion; the resulting funnel plot is shown in Fig. 5B; [no publication bias was observed: Egger’s test (two-tailed P=0.8232), and Begg’s test (two-tailed P=1.000)]. Moreover, we found just one article among the included studies that investigated the prevalence of U. parvum and reported its prevalence to be 2% and 3% in fertile and infertile men, respectively ( 27 ).

Fig. 5:

Meta-analysis of urogenital mycoplasmas prevalence for six case-control studies about men. A: forest plot, B: funnel plot; UU: U. urealyticum; MG: M. genitalium; UP: U. parvum

Discussion

Urogenital mycoplasma species are primarily mucus-associated organisms inhabiting the urogenital tracts of their hosts in close relation with epithelial cells. They may invade host cells and reside intracellularly; a trait that may assist them to cause chronic infections and give them the ability to evade from host immune responses ( 5 , 27 – 28 ). These microorganisms may also cause clinically asymptomatic infections as an opportunistic pathogen, while considering as commensals ( 21 – 25 ); perhaps due to an imbalance occurred among vaginal microbiota in some circumstances in which some bacteria can multiply and cause diseases ( 29 ). However, a considerable amount of urogenital infections caused by these bacteria is asymptomatic and remain undetected and untreated, and consequently the infection may be transmitted to the sexual partner(s). Thus, designing and implementing national control programs to prevent subsequent complications is thought to be necessary. Comprehensive analyses of the overall prevalence of these bacteria, particularly in developing countries (including Iran), may help to carry out such a strategy.

Through this systematic review and meta-analysis, which is the first such study in Iran, we found that prevalence and frequency of urogenital mycoplasma species in men as well as women was highly variable in various studies. There was also a high grade of heterogeneity in participants’ characteristics, samples taken for tests, detection methods, sample sizes, and study settings.

As men and women are distinct populations with different indicators of prevalence, corresponding data about each of them were analyzed separately in the present study. Among articles finally included in this analysis, there were no studies conducted in central, southern, or northwestern Iran, and most of them were performed in the capital of Iran (Tehran); this was one of the limitations of our study, which may suggest some participation bias in the generalization of the meta-analysis results. Another restriction of the present study was that many papers conducted in different regions of the country had to be excluded from analysis because their methods of detection were serology (for example, ELISA and IF) or culture, which have lower sensitivity and specificity in comparison with molecular techniques. Furthermore, the samples used for detections were different, and sample sizes in the included studies were different and ranged from 45–246 and 44– 465 for men and women, respectively; this may have impacted on the results of analysis, thus we calculated and reported the relative weight for each study. An additional restriction encountered in the current study was that the numbers of included studies investigated the prevalence of M. genitalium in both men and women, and M. hominis and U. urealyticum in men were fewer than 10 and insufficient for a good meta-analysis and an accurate conclusion.

In order to find out about possible effects of urogenital mycoplasmas on fertility potential, we analyzed five case–control studies among the included articles investigated the prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas in both fertile and infertile men; the odds ratios for all of these studies were above 1, P values for three surveys (investigated U. urealyticum) were below 0.05, the overall odds ratio was 3.2 (95% CI, range: 1.7–6.1), and the overall P value was zero; meaning that the prevalence of these bacteria is significantly higher in the case group (infertile men) compared with that in the control group (fertile men), and these bacteria may play a role in male infertility. Nevertheless, because the number of these studies was fewer than 10, we couldn’t achieve an exact conclusion about the correlation between urogenital mycoplasmas and male infertility; however, as mentioned in the introduction, this topic is controversial and further case–control or cohort studies are needed to conclude accurately and generalize the results. Moreover, we could not find any interventional or randomized-controlled clinical trial studies assessing the effects of antibiotic therapy for urogenital mycoplasmas infections (particularly asymptomatic infections) on the treatment of probable infertility due to these bacteria.

According to the results of our meta-analysis, the highest pooled prevalence among urogenital mycoplasma species belonged to M. hominis in men and U. urealyticum in women, and the pooled prevalence of M. genitalium was lower than M. hominis and U. urealyticum in both men and women ( Table 3 ).

As shown in Table 2 , the study of urogenital mycoplasmas prevalence in the male population was conducted only in two provinces of Iran, in which the pooled prevalence rate was higher in Kerman [pooled prevalence: 16.2%, (95% CI, range: 11.8%–22%)], rather than Tehran [pooled prevalence: 10.1%, (95% CI, range: 6.2%–16.1%)]; although the number of studies was more in Tehran (n=14) rather than the Kerman province (n=3), and there was no study about U. urealyticum from Kerman. In the case of women, the highest prevalence rate belonged to Tonekabon city [22.7%, (95% CI, range: 12.7%–37.3%)], although only one study had been reported from this city on women, and which only investigated the prevalence rate of M. genitalium; after that, Tehran province had 12 studies about three mycoplasma species [pooled prevalence: 19.6%, (95% CI, range: 15.1%–25.1%)], and the lowest one belonged to Sabzevar city [prevalence rate: 2%, (95% CI, range: 0.8%–5.3%)], though only one survey had been performed in this city on women about M. genitalium prevalence ( Table 2 ).

The World Health Organization has estimated that more than 340 million new cases of STIs occur annually throughout the world, with the highest incidence in developing countries ( 30 ).

We could not find similar meta-analysis studies on the prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas conducted either in neighboring or other countries, to be compared with our analysis in Iran. As mentioned in the results, the highest prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas in our analysis was in young individuals of 25–36 yr; this finding is consistent with other studies performed in other countries ( 31 – 36 ). However, the overall prevalence of urogenital mycoplasmas varies in different countries and international reports suggest an increase in infections due to these bacteria over the last decade ( 37 ). This variability in prevalence rates reported in different countries is perhaps due to a variety in ethnic and social populations, differences in detection methods, types of samples studied, sample sizes, hygiene issues, socioeconomic status, age of participants, and absence of regular screening, treatment, and control programs, particularly in some of the developing countries for dealing with the infections caused by these bacteria.

Conclusion

The results show a relatively high prevalence of urogenital mycoplasma species in male as well as female populations in Iran, particularly in youth (25–36 yr). Urogenital mycoplasmas may play a role in male infertility; this highlights the necessity of planning national programs for adequate diagnosis and screening for genitourinary infections due to these bacteria, particularly asymptomatic infections, and treating infected individuals (including sexual partners) to control STIs and the consequent complications, reduce the carrier rate, and maintain reproductive health and fertility potential. Moreover, further case–control studies or randomized-controlled trials are needed, particularly on the likely influences of these bacteria on reproductive health and their correlation with male/female infertility.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1. Razin S. (2006). The genus Mycoplasma and related genera (class Mollicutes). In: The Prokaryotes: A Handbook on the Biology of Bacteria. Eds, Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E. 3rd ed , Springer; . New York: , 836 – 904 . [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krause W. (2008). Male accessory gland infection. Andrologia, 40( 2): 113–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gdoura R, Kchaou W, Ammar-Keskes L, Chakroun N, Sellemi A, Znazen A, et al. (2008). Assessment of Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Ureaplasma parvum, Mycoplasma hominis, and Mycoplasma genitalium in semen and first void urine specimens of asymptomatic male partners of infertile couples. J Androl, 29( 2): 198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Waites KB, Schelonka RL, Xiao L, Grigsby PL, Novy MJ. (2009). Congenital and opportunistic infections: Ureaplasma species and Mycoplasma hominis. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med, 14( 4): 190–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Waites KB, Katz B, Schelonka RL. (2005). Mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas as neonatal pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev, 18( 4): 757–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taylor-Robinson D, Lamont R. (2011). Mycoplasmas in pregnancy. BJOG, 118( 2): 164–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taylor-Robinson D. (2007). The role of mycoplasmas in pregnancy outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol, 21( 3): 425–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stellrecht KA, Woron AM, Mishrik NG, Venezia RA. (2004). Comparison of multiplex PCR assay with culture for detection of genital mycoplasmas. J Clin Microbiol, 42( 4): 1528–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stacey C, Munday P, Taylor-Robinson D, Thomas B, Gilchrist C, Ruck F, et al. (1992). A longitudinal study of pelvic inflammatory disease. Br J Obstet Gynaecol, 99( 12): 994–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mårdh P, Weström L. (1970). Tubal and cervical cultures in acute salpingitis with special reference to Mycoplasma hominis and T-strain mycoplasmas. Br J Vener Dis, 46( 3): 179–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mårdh P. (1983). Mycoplasmal PID: a review of natural and experimental infections. Yale J Biol Med, 56( 5–6): 529–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kataoka S, Yamada T, Chou K, Nishida R, Morikawa M, Minami M, et al. (2006). Association between preterm birth and vaginal colonization by mycoplasmas in early pregnancy. J Clin Microbiol, 44( 1): 51–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang Y, Liang CL, Wu JQ, Xu C, Qin SX, Gao ES. (2006). Do Ureaplasma urealyticum infections in the genital tract affect semen quality? Asian J Androl, 8( 5): 562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sanocka-Maciejewska D, Ciupińska M, Kurpisz M. (2005). Bacterial infection and semen quality. J Reprod Immunol, 67( 1–2): 51–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Potts JM, Sharma R, Pasqualotto F, Nelson D, Hall G, Agarwal A. (2000). Association of Ureaplasma urealyticum with abnormal reactive oxygen species levels and absence of leukocytospermia. J Urol, 163( 6): 1775–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ochsendorf FR. (2008). Sexually transmitted infections: impact on male fertility. Andrologia, 40( 2): 72–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Knox CL, Allan JA, Allan JM, Edirisinghe WR, Stenzel D, Lawrence FA, et al. (2003). Ureaplasma parvum and Ureaplasma urealyticum are detected in semen after washing before assisted reproductive technology procedures. Fertil Steril, 80( 4): 921–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gdoura R, Keskes-Ammar L, Bouzid F, Eb F, Hammami A, Orfila J. (2001). Chlamydia trachomatis and male infertility in Tunisia. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care, 6( 2): 102–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Svenstrup HF, Fedder J, Kristoffersen SE, Trolle B, Birkelund S, Christiansen G. (2008). Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis, and tubal factor infertility—a prospective study. Fertil Steril, 90( 3): 513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clausen HF, Fedder J, Drasbek M, Nielsen PK, Toft B, Ingerslev HJ, et al. (2001). Serological investigation of Mycoplasma genitalium in infertile women. Hum Reprod, 16( 9): 1866–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Al-Daghistani HI, Abdel-Dayem M. (2010). Clinical significance of asymptomatic urogenital Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in relation to seminal fluid parameters among infertile Jordanian males. Middle East Fertil Soc J, 15( 1): 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Günyeli İ, Abike F, Dünder İ, Aslan C, Tapısız ÖL, Temizkan O, et al. (2011). Chlamydia, Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma infections in infertile couples and effects of these infections on fertility. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 283( 2): 379–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klein JO, Buckland D, Finland M. (1969). Colonization of newborn infants by mycoplasmas. N Engl J Med, 280( 19): 1025–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pannekoek Y, Trum JW, Bleker OP, van der Veen F, Spanjaard L, Dankert J. (2000). Cytokine concentrations in seminal plasma from subfertile men are not indicative of the presence of Ureaplasma urealyticum or Mycoplasma hominis in the lower genital tract. J Med Microbiol, 49( 8): 697–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salmeri M, Valenti D, Vignera SL, Bellanca S, Morello A, Toscano MA, et al. (2012). Prevalence of Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis infection in unselected infertile men. J Chemother, 24( 2): 81–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med, 151( 4): 264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ammar A, Gad G, Hasan A, Lamia A. (2014). Virulence Factors in Mycoplasma of Human Origin. Egypt J Med Microbiol, 23( 3): 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 28. McAuliffe L, Ellis RJ, Miles K, Ayling RD, Nicholas RA. (2006). Biofilm formation by mycoplasma species and its role in environmental persistence and survival. Microbiology, 152( 4): 913–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen J, Svenstrup H, Stacey C. (2012). Difficulties experienced in defining the microbial cause of pelvic inflammatory disease. Int J STD AIDS, 23( 1): 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. WHO (2010). Global strategy for the prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections: 2006–2015: breaking the chain of transmission, Geneva, Switzerland: . [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bayraktar MR, Ozerol IH, Gucluer N, Celik O. (2010). Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in pregnant women. Int J Infect Dis, 14( 2): e90–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pónyai K, Mihalik N, Ostorházi E, Farkas B, Párducz L, Marschalkó M, et al. (2013). Incidence and antibiotic susceptibility of genital mycoplasmas in sexually active individuals in Hungary. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 32( 11): 1423–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Song T, Ye A, Xie X, Huang J, Ruan Z, Kong Y, et al. (2014). Epidemiological investigation and antimicrobial susceptibility analysis of ureaplasma species and Mycoplasma hominis in outpatients with genital manifestations. J Clin Pathol, 67( 9): 817–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Verteramo R, Patella A, Calzolari E, Recine N, Marcone V, Osborn J, et al. (2013). An epidemiological survey of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in gynaecological outpatients, Rome, Italy. Epidemiol Infect, 141( 12): 2650–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ye G, Jiang Z, Wang M, Huang J, Jin G, Lu S. (2014). The resistance analysis of Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis in female reproductive tract specimens. Cell Biochem Biophys, 68( 1): 207–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhu C, Liu J, Ling Y, Dong C, Wu T, Yu X, et al. (2012). Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis in Chinese women with genital infectious diseases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol, 78( 3): 406–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Díaz L, Cabrera LE, Fernández T, Ibáñez I, Torres Y, Obregón Y, et al. (2013). Frequency and antimicrobial sensitivity of Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis in patients with vaginal discharge. MEDICC Rev; 15( 4): 45–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Najar Peerayeh S, Ale Yasin A. (2005). Comparison of PCR with Culture for Detection of Mycoplasma hominis in Infertile Women. TRAUMA MON, 10(3): 183–90. (In Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Najar Peerayeh S, Mirdamad R. (2005). Comparison of Culture with Polymerase Chain Reaction for Detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum in Endocervical Specimens. Med J Islam Repub Iran, 19( 2): 175–9. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Najar Peerayeh S, Sattari M. (2006). Detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis in endocervical specimens from infertile women by polymerase chain reaction. Middle East Fertil Soc J, 11( 2): 104–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Soleimani Rahbar A, Golshani M, Fayyaz F, Rafiee Tabatabaei S, Moradi A. (2007). Detection of Mycoplasma DNA from the sperm specimens of infertile men by PCR. Iran J Med Microbiol, 1(1): 47–53. (In Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zeighami H, Peerayeh SN, Safarlu M. (2007). Detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum in semen of infertile men by PCR. Pak J Biol Sci, 10( 21): 3960–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Najar Peerayeh S, Samimi R. (2007). Detection of Ureaplasma Urealyticum in Clinical Samples from Infertile Women by Polymerase Chain Reaction. Iran J Pharmacol Ther, 6( 1): 23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Golshani M, Eslami G, Ghobadloo SM, Fallah F, Goudarzi H, Rahbar AS, et al. (2007). Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum by multiplex PCR in semen sample of infertile men. Iran J Public Health, 36( 2): 50–7. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Najar Peerayeh S, Yazdi RS, Zeighami H. (2008). Association of Ureaplasma urealyticum infection with Varicocele-related infertility. J Infect Dev Ctries, 2( 2): 116–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Najar Peerayeh S, Samimi R. (2008). Comparison Of Culture With The Polymerase Chain Reaction For Detection Of Gennital Mycoplasma. Eur J Gen Pract, 5( 2): 107–11. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Amirmozafari N, Mirnejad R, Kazemi B, Sariri E, Bojari M, Darkahi FD. (2009). Simultaneous Detection of Genital Mycoplasma in Women with Genital Infections by PCR. J Biol Sci, 9( 8): 804–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zeighami H, Peerayeh S, Yazdi R, Sorouri R. (2009). Prevalence of Ureaplasma urealyticum and Ureaplasma parvum in semen of infertile and healthy men. Int J STD AIDS, 20( 6): 387–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ahmadi MH, Amirmozafari N, Kazemi B, Gilani MAS, Jazi FM. (2010). Use of PCR to detect Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum from semen samples of infertile men who referred to Royan Institute in 2009. Cell J, 12(3): 371–80. (In Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nosrat SB, Ghazisaidei K, Livani S, Dadgar T, Bazueri M, Bagheri H, et al. (2011). The Prevalence of Genital Mycoplasmas in Vaginal Infections in Gorgan, Iran. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil, 14(3): 20–8. (In Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 51. Haghighi Hasanabad M, Mohammadzadeh M, Bahador A, Fazel N, Rakhshani H, Majnooni A. (2011). Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium in pregnant women of Sabzevar-Iran. Iran J Microbiol, 3( 3): 123–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hassani A, Shahrokhi N, Khezerdoust S, Sarshar M, Takroosta N, Jamileh N. (2012). Detection of Ureaplasma Urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis in Clinical Isolates from Women with Genital Tract Infection by PCR. Iran J Infect Dis Trop Med, 17(58): 45–50. (In Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 53. Moosavian SM, Motamedi H, Malki S, Shahbazian N. (2011). Comparison between Prevalence of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in Women with Urogenital Infections by Multiplex PCR and Culture Methods. Med J Tabriz Univ Med Sci, 33(5): 91–7. (In Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vosooghi S, Kheirkhah B, Mirshekari T-R, Karimi Nik A, Hamidavi Mohammadpour S, Mohseni Moghadam N. (2013). Molecular detection of Mycoplasma hominis from genital secretions of infertile men referred to the Kerman infertility center. J Microb World, 6(1): 14–22. (In Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sadrpour P, Bahador A, Asgari S, Bagheri R, Chamani-Tabriz L. (2013). Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium in semen samples of infertile men using multiplex PCR. Tehran Univ Med J, 70(10): 623–9. (In Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mohseni R, Sadeghi F, Mirinargesi M, Eghbali M, Dezhkame S, Ghane M. (2013). A study on the frequency of vaginal species of Mycoplasma genitalium, Gardnerella vaginalis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae among pregnant women by PCR technique. Int J Mol Clin Microbiol, 3( 1): 231–6. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yeganeh O, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Yaghmaie F, Kamali K, Heidari-Vala H, Zeraati H, et al. (2013). A survey on the prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium infections in symptomatic and asymptomatic men referring to urology clinic of Labbafinejad Hospital, Tehran, Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J, 15( 4): 340–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Maleki S, Motamedi H, Moosavian SM, Shahbaziyan N. (2013). Frequency of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in Females With Urogenital Infections and Habitual Abortion History in Ahvaz, Iran; Using Multiplex PCR. Jundishapur J Microbiol, 6( 6): 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Irajian G, Mirnejad R, Ghorbanpour N. (2013). Determing the Prevalence Rate of Mycoplasma genitalium in Patients with Prostatitis by PCRRFLP Technique. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci, 13(1): 86–92. (In Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ahmadi A, Khodabandehloo M, Ramazanzadeh R, Farhadifar F, Nikkhoo B, Soofizade N, et al. (2014). Association between Ureaplasma urealyticum endocervical infection and spontaneous abortion. Iran J Microbiol, 6( 6): 392–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Akya A, Ale Taha SM. (2014). The frequency of Mycoplasma genitalium infection in women with cervicitis in Kermanshah. J Clin Res Paramed Sci, 3(1): 56–62. (In Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mousavi A, Farhadifar F, Mirnejad R, Ramazanzadeh R. (2015). Detection of genital mycoplasmal infections among infertile females by multiplex PCR. Iran J Microbiol, 6( 6): 398–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bahaabadi SJ, Moghadam NM, Kheirkhah B, Farsinejad A, Habibzadeh V. (2014). Isolation and Molecular Identification of Mycoplasma hominis in Infertile Female and Male Reproductive System. Nephrourol Mon, 6 (6): e22390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mohseni Moghadam N, Kheirkhah B, Mirshekari TR, Harandi MF, Tafsiri E. (2014). Isolation and molecular identification of mycoplasma genitalium from the secretion of genital tract in infertile male and female. Iran J Reprod Med, 12( 9): 601–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sobouti B, Fallah S, Mobayen M, Noorbakhsh S, Ghavami Y. (2014). Colonization of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in pregnant women and their transmission to offspring. Iran J Microbiol, 6( 4): 219–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Safavifar F, Bandehpour M, Hosseiny SJ, Khorramizadeh MR, Shahverdi A, Kazemi B. (2015). Mycoplasma Infection in Pyospermic Infertile and Healthy Fertile Men. Novel biomed, 3( 1): 25–9. [Google Scholar]