Abstract

Introduction: The aim of the current study was to present and discuss a broad range of register-based definitions of chronic conditions for use in register research, as well as the challenges and pitfalls when defining chronic conditions by the use of registers. Materials and methods: The definitions were defined based on information from nationwide Danish public healthcare registers. Medical and epidemiological specialists identified and grouped relevant diagnosis codes that covered chronic conditions, using the International Classification System version 10 (ICD-10). Where relevant, prescription and other healthcare data were also used to define the chronic conditions. Results: We identified 199 chronic conditions and subgroups, which were divided into four groups according to a medical judgment of the expected duration of the conditions, as follows. Category I: Stationary to progressive conditions (maximum register inclusion time of diagnosis since the start of the register in 1994). Category II: Stationary to diminishing conditions (10 years of register inclusion after time of diagnosis). Category III: Diminishing conditions (5 years of register inclusion after time of diagnosis). Category IV: Borderline conditions (2 years of register inclusion time following diagnosis). The conditions were primarily defined using hospital discharge diagnoses; however, for 35 conditions, including common conditions such as diabetes, chronic obstructive lung disease and allergy, more complex definitions were proposed based on record linkage between multiple registers, including registers of prescribed drugs and use of general practitioners’ services. Conclusions: This study provided a catalog of register-based definitions for chronic conditions for use in healthcare planning and research, which is, to the authors’ knowledge, the largest currently compiled in a single study.

Keywords: Catalog, chronic conditions, chronic disease, definition, disease duration, linkage, quality of life, registry, study design

Introduction

Healthcare costs and the disease burden of chronic illness are rising, along with a growing ageing population [1–6]. This underlines an increasing need for accurate tools for monitoring the epidemiology of chronic conditions, including incidence, prevalence and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for use in healthcare planning, decision making, forecasting and research.

Existing studies measure population prevalence estimates of chronic conditions very differently, varying from community-based health surveys and screening examinations to register-based studies. The choice of definitions, methods and source of data may affect the findings substantially. Among the obvious strengths of using registers is the fact that the diagnoses are reported by clinicians; and thus are preferred by other studies as the registers are free of unwanted self-reported bias [7]. Also, the completeness of data is mostly high. In addition, register data is often available up-to-date and cost-effectiveness is high, since the data has already been collected [8].

The Scandinavian countries have a long tradition of keeping high-quality registers on all key aspects of the life of its citizens, including healthcare, and these registers are essential for healthcare planning and epidemiological research. Several studies have used registers to estimate the burden of chronic disease [2,4,9–14]; however, these studies usually only covered a few selected chronic conditions. To the authors’ knowledge, there are so far no existing register-based studies that have aimed to present a catalogue of register-based definitions on a broad range of chronic conditions.

The aim of this study was to present a comprehensive catalogue of register-based definitions of chronic conditions, and to discuss the challenges and pitfalls when doing so. Also, an important aim was to ensure the usefulness of the definitions in both the register and the linked survey studies. This study is the first in a series that estimate both nationwide population prevalence and HRQoL, based on surveys of the 199 chronic conditions in Denmark [15].

Materials and methods

The definitions within current study were defined based on information from nationwide Danish public registers.

The Danish National Patient Register (NPR)

The NPR was established in 1977 and holds data on diagnosis, treatments, patient type, dates and more from all nationwide hospital treatments for every patient contact, at the individual level [16,17]. The NPR was originally established for administrative use, but has over the years increasingly been used for research, due to the richness and quality of the data. From 1995, the register included both somatic and psychiatric patients, as well as emergency patients; and with the coming of private healthcare in the 2000s, private hospital and clinic patients were included in the NPR from 2003. The use of the International Classification System’s ICD-10 codes was implemented in 1994 [16].

The NPR is based on the attending physician’s reports of patient diagnosis and treatments, which are collected in data servers at the hospitals on a daily basis and later sent to NPR. The diagnoses are reported at hospital discharge and after every outpatient contact or treatment, for each patient. Reporting to the NPR is mandatory, according to Danish law. The patient diagnoses are reported as being:

Primary (A), i.e. an ‘action’ diagnosis or the first-treated and main illness of interest;

Secondary diagnosis (B), i.e. secondary diagnosis of relevance for treatment; or

Additional diagnosis (+), identified for up to 19 diagnoses, but these were not necessarily treated or of relevance for the specific hospital contact.

The NPR includes data on both inpatients and outpatients, and emergency patients [16]; however, the emergency patients were excluded from the present study at all times, as the validity of an emergency diagnosis has not been adequately shown [18,19].

The Danish National Psychiatry Central Research Register (PCRR)

To increase the accuracy and precision of psychiatric diagnoses, the PCRR [20] was also employed in this study. The PCRR was first started in 1938, but was made national in 1969; and it includes information on all psychiatry admissions at Danish psychiatric hospitals. The register also comprised nationwide inpatients and outpatients, as well as emergency visits and ICD-10 diagnoses from 1995 (when the register also became an integrated part of the NPR) on [20]. Besides the diagnosis, the PCRR also contains information including date, patient discharge information, type of referral and place of treatment. The PCRR data is collected and reported by the attending physicians.

National Health Service Register (NHSR)

The NHSR [21,22] comprises information from services and activities of primary care health professionals who were contracted to the Danish nationwide, public, tax-funded healthcare system. This includes information from all general practitioners (GPs), practicing medical specialists, dentists, physiotherapists, psychologists, chiropodists and chiropractors. The NHSR contains information used for economic settlement of services with the government, and also from 1990 for research purposes; thus, the NHSR was included in the current study to link the services (e.g. patient blood samples, diabetes tests, lung tests, different laboratory tests, the types of consultation and referrals to specialists) to specific diagnoses, where possible. The data is reported electronically every week through the GP invoices to the Regional Health Administration, which is afterwards passed on to the Danish National Board of Health [21].

The Danish National Prescription Register (DNPR)

The DNPR [23,24] was established in 1994 and it contains information on all prescribed medicine at an individual level, redeemed outside hospitals (pharmacies), for all Danish individuals. All medicine is reported using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification (ATC) code, the date and personal identification number for linkage to other registers; however, the DNPR does not provide information on over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, nor drugs dispensed at hospitals.

All Danish pharmacies are obligated to report any dispensed prescriptions electronically to the Danish Medicines Agency, enhancing the validity of the register. In practice, all drug packages are labeled with a barcode matching the drug’s article number. Thus, information bias, and inter- and intra-observer bias, are unlikely to occur in the DNPR, ensuring high-quality data; however, naturally the DNPR does not document ingestion of the drugs (primary non-compliance); therefore, the register is a surrogate measure for the patient’s real ingestion of the drug [23]. The DNPR is included in the present study to increase the accuracy of several definitions, by linking specific drugs to specific conditions where possible (i.e. like NHSR, we used the DNPR to identify patients whom were exclusively diagnosed and treated for their chronic condition in the primary care sector).

The Danish Civil Registration System (DCRS) and linkage to healthcare registers

In Denmark, all persons alive and living are registered in the DCRS; which includes the patient name, gender, birthdate or age, place of residence, whether they are alive or their death, and more [25,26]. The DCRS identifies inhabitants by a unique 10-digit personal identification number (their ‘CPR’ number). This allows record linkage across time on an individual level, for data from complete national registers including the DCRS and different healthcare registers of a current study. The full Danish population aged ⩾ 16 years consisted of 4,555,439 citizens on 1 January 2013.

Identifying and classifying chronic conditions

A medical review of the definitions was done in cooperation with experienced physicians, including specialists in public health diseases, diseases of the circulatory system, psychiatric conditions, musculoskeletal diseases, specialists in general medicine and clinical epidemiologists, as well as other experienced experts in the field (working with research, data management and disease estimation). The medical review and ratification included identifying the ICD-10 codes of chronic conditions and assessing the average duration of the identified conditions. Finally, physicians and epidemiologists identified conditions that required more complex register-based definitions, including use of prescription and health services data, and reviewed and ratified the complex register definitions. The medical review, involved physicians, and a description of the process and considerations of the work are presented in more details in the online supplementary material.

Chronic conditions were defined in accordance with other international studies [27–30]: “We defined a person as having a chronic condition if that person’s condition had lasted or was expected to last 12 or more months and resulted in functional limitations and/or the need for ongoing medical care.” [28].

The definition was used to identify the conditions with an expected duration of at least 12 months and their corresponding ICD-10 codes. In the case of disagreements or doubt of chronicity, the definitions of the conditions were compared to previous work where possible, to make a decision [27,29,30]. Finally, the chosen and chronic ICD-10 codes were grouped into 199 clinically meaningful groups, using the standard ICD-10 groupings and subgroupings.

Because no absolute ‘cutpoints’ or gold standards existed regarding the size of the grouped conditions, two criteria were used (besides ensuring clinically meaningful groups of conditions based on the ICD-10 groupings). First, the conditions were grouped based on the existing two- or three-level ICD-10 codes (e.g. C56 or M797) where clinically advised. Secondly, as the catalogue was also intended to be used in linkage with larger surveys, a test sample of 56,988 respondents [31,32] was applied, along with a minimum requirement of 50 persons within every condition, for proper statistical analysis. If the statistical requirement could not be reached, the condition was grouped into the previous, nearest and broader ICD-10 level if possible; or kept at the two or three ICD-10 levels based on a clinical assessment (see the online supplementary material).

Starting with approximately 22,000 ICD-10 codes and conditions, we ended up with 199 conditions and groups of conditions comprising, to the authors’ knowledge, most chronic conditions, by using the above criteria and definition. A few conditions could not meet the 50-person requirement and could not be collapsed in a clinically meaningful way into other conditions. Besides the 199 conditions, five groups of medications for common conditions were also defined: Depression, antipsychotic, anxiety, heart failure and ischemic heart medication.

Duration of conditions: Chronicity

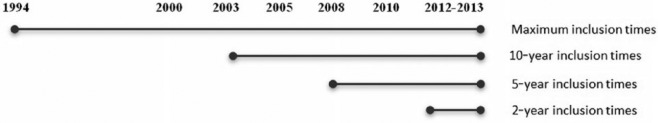

While the above definition of ‘chronic’ solely outlines a condition as chronic when it has existed for a minimum of 12 months, it does not take into account that not all chronic conditions will have a lifelong presence. Since the expected duration in fact varies across different chronic conditions, the conditions were grouped into one of four categories, according to their expected duration:

Category I: Stationary to progressive chronic conditions (no time limit equals inclusion time going back from the time of interest, for as long as valid data were available. In the current study, this starting point was defined by the introduction of the ICD-10 diagnosis coding in Denmark, in 1994);

Category II: Stationary to diminishing chronic conditions (10 years of register inclusion time, to the time of interest);

Category III: Diminishing chronic conditions (5 years of register inclusion time, to the time of interest); and

Category IV: Borderline chronic conditions (2 years of register inclusion time, to the time of interest).

The grouping of the conditions into one of the four categories was based on a medical assessment of the average duration of the individual conditions from first identification and diagnosis in the registers.

This was done to ensure with best clinical certainty that the condition was present when looking back in registers from the time of interest. For instance, the categorization of inclusion times defined whether a person reported with depression once in 2008 or later is to be considered to have a chronic condition at the time of interest (on for example, 1 January 2013). In consequence, if a diagnosis was identified in the NPR once or more in the specified inclusion time period, it was considered as chronic, according to our criteria. For the Category III diminishing chronic conditions (e.g. depression), a condition was included as chronic if it was found at least once in the register within the 5 years leading to 1 January 2013 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Example of the four categories of chronicity and the inclusion time periods, based on a “time of interest” set to 1 January 2013.

The complex definitions for selected conditions and medicine

For 35 conditions, more complex definitions were created using medication records, GP services and hospital treatments where possible, besides the diagnosis codes; but also solely by diagnosis codes in clinically reviewed combinations, for some conditions (Table I). For example, the conditions were chosen if they were primarily treated in primary care and thus not reported by diagnosis from hospitals, making several registers necessary to capture the condition; or if the clinical experience and literature suggested complex combinations of diagnosis codes for better precision of a specific condition. Finally, five different medications comprising different, non-ICD-10 specific chronic conditions were also added besides the 199 conditions, as they were of general interest.

Table I.

The 35 (33+2) complex definitions and five medicine definitions.

| No. | Condition | ICD-10 | Category | Definitions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brain cancer [40,41] | C71, C75.1–75.3, D33.0–33.2, D35.2–35.4, D43.0–43.2, D44.3–44.5 (brain). C70, D32, D42 (brain membrane). C72, D33.3–33.9, D43.3–43.9 (cranial nerve, spinal cord) | Cat. II | (DIAG)b |

| 2 | Diseases of the thyroid | E00–04, E06, E07 | Cat. III | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE10)c including all prescriptions with ATC: H03. |

| EXCLUDED: If defined with thyrotoxicosis. | ||||

| 3 | Thyrotoxicosis | E05 | Cat. III | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE)c including all prescriptions with ATC: H03B and H03C. |

| 4 | Diabetes Type 1 [13,37,38,42] | E10 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and (MEDICINE)c. Patients that have had a minimum of two medicine prescriptions, any time since 1995, with ATC: A10A (insulin prescription); and/or: all patients who have gotten at least one ICD-10 E10 or ICD-8 249 diagnosis code since 1987, or ICD-8 code 250 from 1977 to 1986, before age 30 at the time of contact and at a minimum one ATC: A10A prescription anytime. EXCLUDED: All diagnoses and medicine contacts for 1 year after first diagnosed with ICD-10: O24.4 / ICD-8 63474 (pregnancy diabetes), and/or all, if defined with diabetes Type 2 below. |

| 5 | Diabetes Type 2 [13,37–39,42,43] | E11 | Cat. II | (DIAG)b with minimum 2 diagnoses/contacts. And/or: |

| (MEDICINE10)c ATC: A10A and if age 40+ at time of prescription. And/or ATC: A10B at age 30+ at time of prescription. And all needs a minimum of two prescriptions. And/or: | ||||

| (SERVICE10)d: ‘Foot therapy for diabetes patients’ (specialty 54) once within the last 10 years, or ‘bloodsucherer meassurements’ (service numbers XX7136 and XX7159, except specialties 44, 45, 46 in places of the two X’s) twice each year, during a period of a minimum of 5 years (blood2in5) or | ||||

| 5 times within 1 year, once within the last 10 years (blood5in1). | ||||

| EXCLUDED: (MEDICINE10)c A10A medicine inclusion criterion is excluded if a patient is diagnosed with diabetes Type 1 as defined above. (MEDICINE10)c A10B and DIAGb criteria are excluded if a patient is diagnosed the first time with Type 1 before age 30 at the time of contact, and prescribed ATC: A10A anytime as described in the above definition of type I. Service inclusion criteria are excluded if a patient is defined with diabetes Type 1 as defined above. All diagnosis and medicine contacts are excluded from and 1 year after first diagnosed with O24.4 (pregnancy diabetes). And/or if women are diagnosed with E282 (PCOS) or have been treated with PCOS medicine ATC: A10BA02 in combination with either ATC: G03GB02 or G03HB. | ||||

| 6 | Diabetes others [42] | E12–14 | Cat. III | (DIAG)b. |

| EXCLUDED: If diabetes Types I and II already defined. | ||||

| 7 | Disorders of lipoprotein metabolism/ other lipidemias | E78 | Cat. III | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE5)c, including all prescriptions with ATC: C10. |

| 8 | Cystic fibrosis [38,37] | E84 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE)c including all prescriptions with indication codes 369 (cystic fibrosis) or 433 (against lung infection in cystic fibrosis) and/or ATC: R05CB13 (cystic fibrosis-specific medicine). |

| 9 | Dementia [35] | F00, G30, F01, F02.0, F03.9, G31.8B, G31.8E, G31.9, G31.0B | Cat. I | (DIAG)b all patients of age 60+ at contact, who have had a minimum of one contact with one of the ICD-10 codes on the left since 1994. And/or: (MEDICINE)c patients who have had a minimum of one medicine prescription with either indication codes 329 (dementia), 330 (Alzheimer’s dementia) or 331 (Alzheimer’s disease) and/or ATC: N06D. |

| 10 | Schizophrenia [34,37,38] | F20 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and |

| EXCLUDED: If complete remission (ICD-10: F20.05, F20.15, F20.25, F20.35, F20.45, F20.55, F20.65, F20.85, F20.95). | ||||

| 11 | Bipolar affective disorder | F30–F31 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE)c ATC: N05A or N06A with indication codes 491 (of mania) or 631 (treatment of bipolar disorder). |

| 12 | Depression [34,44] | F32, F33, F34.1, F06.32 | Cat. III | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE5)c ATC: N06A with indication code 168 (against depression). |

| 13 | OCD | F42 | Cat. II | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE10)c ATC: N06A with indication codes 472 (from OCD) or 596 (the treatment of OCD). |

| 14 | Hyperkinetic disorders (ADHD) | F90 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE)c including all prescriptions with indication code 376 (against hyperactivity) or 391 (for treatment of ADHD). And/or: ATC: N06BA. |

| 15 | Parkinson’s disease | G20, G21, G22, F02.3 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE)c, including all prescriptions with ATC: N04. |

| 16 | Epilepsy [45,46] | G40–G41 | Cat. III | (DIAG)b and minimum of two NPR contacts with a minimum of one of the diagnosis codes on the left, within the last 5 years. And/or: (MEDICINE5)c ATC: N03, N05BA, N05CD with indication codes 155 (epilepsy) or 753 (prolonged epileptic seizures). |

| 17 | Migraine | G43 | Cat. II | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE10)c, including all prescriptions with: ATC: N02C. And/or: either indication codes 56 (for the prevention of migraine), 153 (migraine) or 594 (migraine prophylaxis). |

| 18 | Glaucoma [47] | H40–H42 | Cat. III | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE5)c, including all prescriptions with ATC: S01E. |

| 19 | Ménière’s disease | H810 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE)c, including all prescriptions with indication code 194 (against Ménière’s disease). |

| 20 | Aortic and mitral valve disease [48] | I05, I06, I34, I35 | Cat. III | (DIAG)b |

| 21 | Hypertensive diseases [49,50] | I10–I15 | Cat. III | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE5)c, including all prescriptions with a combination treatment with at least two of the following classes of antihypertensive drugs with ATC: codes: |

| ● α Adrenergic blockers (C02A, C02B, C02C); | ||||

| ● Non-loop diuretics (C02DA, C02L, C03A, C03B, C03D, C03E, C03X, C07C, C07D, C08G, C09BA, C09DA, C09XA52); | ||||

| ● Vasodilators (C02DB, C02DD, C02DG, C04, C05); | ||||

| ● β Blockers (C07); | ||||

| ● Calcium channel blockers (C07F, C08, C09BB, C09DB); | ||||

| ● Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors (C09). | ||||

| 22 | Heart failure [34,51] | I11.0, I13.0, I13.2, I42.0, I42.6, I42.7, I42.9, I50.0, I50.1, I50.9 | Cat. II | (DIAG)b and only A-diagnosis. |

| 23 | Stroke [34,52] | I60, I61,I63–I64,Z501 (rehabilitation) | Cat. II | (DIAG)b I60, I61, I63, I64 with A-diagnosis only. And/or DZ501 as A-diagnosis in combination with I61, I63–I64 as A- or B-diagnosis. |

| 24 | Hemorrhoids | I84 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE2)c, including all prescriptions with ATC: C05A and indication code 63 (for hemorrhoids). |

| 25 | Respiratory allergy [35] | J30, except J30.0 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE)c ATC: V01AA02, V01AA03, V01AA05, V01AA11; R01AC, R01AD, R06A, S01G, R01BA52. |

| 120Aa | Chronic lower respiratory diseases [35] | J40–J43, J47 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE)c including all prescriptions with indication codes 127, 396 or 740 (bronchitis). And/or ATC: R03AC, R03AK, R03BA, R03BB, R03CC, R03DA, R03DC, V03AN01. |

| EXCLUDED if they have cystic fibrosis as defined; and/or if medicine comprises COPD and asthma-specific medicine, as defined below. | ||||

| 26 | COPD [35,53,54] | J44, J96, J13–J18 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b All patients of minimum 30 years of age at contact who have had a minimum of one contact with J44 with an A-diagnosis. And/or J96 with A-diagnosis in combination with J44 with B-diagnosis. And/or J44 or J96 with B-diagnosis in combination with J13–18 with A-diagnosis. And/or: (MEDICINE)c including all prescriptions with indication codes 379 or 464. And/or ATC: R03AC18, R03AC19, R03AL02, R03AL03, R03AL04, R03BB04, R03BB05, R03BB06, R03DX07 (COPD-specific medicine). And/or: |

| (SERVICE10)d if patients have had a minimum of two lab services within the last 12 months. Lab services: (80)7113 (lung spirometer test), (80)7121 (lung function test). | ||||

| EXCLUDED if has cystic fibrosis as defined. | ||||

| 27 | Asthma, status asthmaticus [35] | J45–J46 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE)c, including all prescriptions with indication codes 202 (for asthma) or 203 (for the prevention of asthma) and/or all prescriptions with ATC: R03DC03. EXCLUDED if has cystic fibrosis as defined. |

| 28 | Ulcers | K25–K27 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE2)c including all prescriptions with indication codes 003 (for ulcer) or 465 (against ulcer (Helicobacter pylori eradication)). And/or ATC: A02BD. Only one prescription needed. |

| 29 | Psoriasis | L40 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE)c, including all prescriptions ATC: D05 unless D05BB. And/or ATC: D05BB with either indication codes 221 (psoriasis), 231 (psoriasis with infection), 243 (against scalp psoriasis), 246 (against infected psoriasis) or 344 (for psoriasis of the scalp). |

| 30Aa | Inflammatory polyarthropathies and ankylosing spondylitis [35,36] | M05–M14, M45 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE)c, including all prescriptions with indication codes 147 (RA), 402 (RA), 641 (for RA), 406 (ankylosing spondylitis) or 407 (Bechterew’s disease). And/or ATC: M01C, LO4AA13, A07EC01, P01BA01, P01BA02, M04AA01, M04AA03, M04AB01. |

| 30 | RA [35,36] | M05, M06, M07.1, M07.2, M07.3, M08, M09 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE)c including all prescriptions with indication codes 147 (RA), 402 (RA) or 641 (for RA) and/or ATC: M01C, LO4AA13, A07EC01, P01BA01, P01BA02. |

| 31 | Inflammatory polyarthropathies, except RA [35,36] | M074–M079, M10–M14, M45 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or (MEDICINE10)c including all prescriptions with indication code 406 (ankylosing spondylitis) or 407 (Bechterew’s disease). And/or ATC: M01C, LO4AA13, A07EC01, P01BA01, P01BA02, M04AA01, M04AA03, M04AB01.EXCLUDED if indication codes equal 147, 402 or 641 of RA at any time. |

| 32 | Osteoporosis [35,37,38] | M80–M81 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b All patients of age 50+ at contact that have had minimum one contact with one of the ICD-10 codes on the left since 1994. And/or: |

| (MEDICINE)c all medicine prescriptions with either ATC: M05BA01, M05BA04, M05BA06, M05BA07, M05BB01, M05BB03, G03XC01, H05AA02, H05AA03. | ||||

| 33 | CRF [14] | N18 | Cat. I | (DIAG)b and/or:(C1) included the procedure codes concerning kidney transplant (KKAS10 or KKAS20) just once since 2000. And/or:(C2) condition 1: The patient has been in dialysis (SKS code BJFD) at least 12 times (for at least one period) of 90–97 days after 1 January 2000, in which either the distance between the first and last dialysis is 90–97 days, or:(C3) condition 2: at least one dialysis was reported as chronic peritoneal dialysis (SKS codes: BJFD21, BJFD22, BJFD23, BJFD24, BJFD25 or BJFD27). |

| 1M | Depression medicine | None | (MEDICINE2)c ATC: N06A. | |

| 2M | Antipsychotic medicine | None | (MEDICINE2)c ATC: N05A. | |

| 3M | Indication prescribed anxiety medicine | None | (MEDICINE2)c all prescriptions with either indication codes 163 (for anxiety) or 371 (for anxiety, addictive). | |

| 4M | Heart failure medication [37,38] | None | (MEDICINE2)c including all prescriptions of ATC: C01AA05, C03, C07 or C09A with indication code 430 (for heart failure). | |

| 5M | Ischemic heart medication [35] | None | (MEDICINE2)c including all prescriptions of ATC: C01A, C01B, C01D, C01E. |

Conditions numbered with “A” are overlapping with other conditions and thus, not counted twice. Use the different definitions according to specific needs.

DIAG: All patients, any age unless specified otherwise, that have had a minimum of one hospital or outpatient contact, with one of the ICD-10 diagnosis codes of the condition within the defined inclusion time described by Categories I–IV. Both ‘open’ (ongoing treatment) and ‘closed’ (finalized treatment) contacts, as well as primary (A), secondary (B) and additional (+) diagnosis are included.

MEDICINE: All patients that have had a minimum of two medicine prescriptions as defined by the ATC codes and/or indication codes within a period of 12 months, at last one time during the specified period from the time of interest. MEDICINE10 indicates that medication criteria have been included for 10 years from the time of interest, MEDICINE5 for 5 years, and MEDICINE2 for 2 years. If no number is specified after a medicine, the inclusion time is the same as that in the diagnosis category. For medicine using indication codes, medicine can only be included at the earliest from 2004, which is when indication codes were first reported. Records of ATC medicine prescriptions exist from 1995.

SERVICE10: Patients that have had a minimum of one healthcare SERVICE during the last 10 years.

ADHD: attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; ATC: Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical classification; Cat: category; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRF: chronic renal failure; ICD: International Classification of Disease; OCD: obsessive-compulsive disorder; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; SERVICE10: Patients with a minimum of one healthcare SERVICE during the last 10 years.

Where possible, the complex definitions were inspired by existing research, including those in ‘The Danish Clinical Registries’ (TDCR), a collection of disease-specific clinical databases [33,34] with clinically validated and tested definitions, the Research Centre for Prevention and Health [10,35,36], the Statens Serum Institute (SSI) register of eight selected chronic conditions [37,38], and different studies referenced in Table I.

Because the existing literature often had a different purpose than that of the current study, or fewer registers to include, it is important to underline that the majority of the definitions in the present study are not identical to those used in existing literature, but are inspired by them. For example, we have added medicine to the existing TDCR definitions where clinically relevant to best capture the disease population, or we have divided conditions into more subgroups than the existing literature, in order to get more detailed conditions (e.g. diabetes, chronic lower respiratory disease and heart conditions). The definitions in this catalogue have been adjusted to suit the purpose of best capturing the condition at a specific time, while several existing databases estimate yearly incidence or specific hospital procedures, making the adjustments necessary here.

Results

The definitions and the four categories of chronicity

The 199 conditions, their definitions and their allocation to one of the four categories of chronicity, are shown in Table I and Table II. Table I shows the more complex definitions. All 199 conditions reflect both primary (A), secondary (B) and additional (+) diagnoses; and they include data on both inpatients and outpatients, unless otherwise specified.

Table II.

The 166 diagnosis-based definitions of somatic and mental chronic conditions and their categories, sorted by ICD-10 diagnosis.

| No. | Somatic conditions | ICD-10 | Category | Definitions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34 | Chronic viral hepatitis | B18 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 35 | HIV | B20–B24 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 36 | Malignant neoplasms of other and unspecified localizations | C00–C14; C30–C33; C37–C42; C45–C49; C69; C73–74; C754–C759 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 37 | Malignant neoplasms of digestive organs | C15–C17; C22–C26 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 38 | Malignant neoplasm of the colon | C18 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 39 | Malignant neoplasms of the rectosigmoid junction, rectum, anus and anal canal | C19–C21 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 40 | Malignant neoplasm of bronchus and lung | C34 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 41 | Malignant melanoma of skin | C43 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 42 | Other malignant neoplasms of skin | C44 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 43 | Malignant neoplasm of the breast | C50 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 44 | Malignant neoplasms of female genital organs | C51–C52; C56–C58 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 45 | Malignant neoplasm of the cervix uteri, corpus uteri and part unspecified | C53–C55 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 46 | Malignant tumor of the male genitalia | C60, C62–C63 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 47 | Malignant neoplasm of prostate | C61 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 48 | Malignant neoplasms of urinary tract | C64–C68 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 49 | Malignant neoplasms of ill-defined, secondary and unspecified sites, and of independent (primary) multiple sites | C76–C80, C97 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 50 | Malignant neoplasms, stated or presumed to be primary, of lymphoid, haematopoietic and related tissue | C81–C96 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 51 | In situ neoplasms | D00–D09 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 52 | Hemolytic anemias | D55–D59 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 53 | Aplastic and other anaemias | D60–D63 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 54 | Other anemias | D64 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 55 | Coagulation defects, purpura and other hemorrhagic conditions | D65–D69 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 56 | Other diseases of blood and blood-forming organs | D70–D77 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 57 | Certain disorders involving the immune mechanism | D80–D89 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 58 | Disorders of other endocrine glands | E20–E35, except E30 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 59 | Metabolic disorders | E70–E77; E79–E83; E85; E88–E89 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 60 | Inflammatory diseases of the central nervous system | G00–G09 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 61 | Systemic atrophies primarily affecting the central nervous system and other degenerative diseases | G10–G14, G30–G32 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 62 | Extrapyramidal and movement disorders | G23–G26 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 63 | Sclerosis | G35 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 64 | Demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system | G36–G37 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 65 | Other headache syndromes | G44 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 66 | Transient cerebral ischemic attacks and related syndromes and vascular syndromes of the brain in cerebrovascular diseases | G45–G46 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 67 | Sleep disorders | G47 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 68 | Disorders of the trigeminal nerve and facial nerve disorders | G50–G51 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 69 | Disorders of other cranial nerves, cranial nerve disorders in diseases classified elsewhere, nerve root and plexus disorders, and nerve root and plexus compressions in diseases classified elsewhere | G52–G55 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 70 | Mononeuropathies of the upper limb | G56 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 71 | Mononeuropathies of the lower limb, other mononeuropathies and mononeuropathy in diseases classified elsewhere | G57–G59 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 72 | Polyneuropathies and other disorders of the peripheral nervous system | G60–G64 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 73 | Diseases of myoneural junction and muscle | G70–G73 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 74 | Cerebral palsy and other paralytic syndromes | G80–G83 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 75 | Other disorders of the nervous system | G90–G99 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 76 | Disorders of eyelid, lacrimal system and orbit | H02– H06 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 77 | Corneal scars and opacities | H17 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 78 | Other disorders of the cornea | H18 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 79 | Diseases of the eye lens (cataracts) | H25–H28 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 80 | Disorders of the choroid and retina | H31–H32 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 81 | Retinal vascular occlusions | H34 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 82 | Other retinal disorders | H35 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 83 | Retinal disorders in diseases classified elsewhere | H36 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 84 | Disorders of the vitreous body and globe | H43–H45 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 85 | Disorders of optic nerve and visual pathways | A: H46, H48 and B: H47 | A: Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| B: Cat. III | ||||

| 86 | Disorders of ocular muscles, binocular movement, accommodation and refraction | A: H49 and B: H50, H52 and C: H51 | A: Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| B: Cat. IV | ||||

| C: Cat. I | ||||

| 87 | Visual disturbances | H53 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 88 | Blindness and partial sight | H54 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 89 | Nystagmus and other irregular eye movements and other disorders of eye and adnexa | H55, H57 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 90 | Otosclerosis | H80 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 91 | Other diseases of the inner ear | H83 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 92 | Conductive and sensorineural hearing loss | H90 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 93 | Other hearing loss and other disorders of ear, not elsewhere classified | H910, H912, H913, H918, H930, H932, H933 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 94 | Presbycusis (age-related hearing loss) | H911 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 95 | Hearing loss, unspecified | H919 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 96 | Tinnitus | H931 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 97 | Other specified disorders of the ear | H938 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 98 | Angina pectoris | I20 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 99 | Acute myocardial infarction and subsequent myocardial infarction | I21–I22 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 100 | Acute myocardial infarction complex/other | I23–I24 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 101 | Chronic ischemic heart disease | I25 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 102 | Pulmonary heart disease and diseases of pulmonary circulation | I26–I28 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 103 | Acute pericarditis | I30 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 104 | Other forms of heart disease | I31–I43, except I34–I35 and I42 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 105 | Atrioventricular and left bundle-branch block | I44 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 106 | Other conduction disorders | I45–46 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 107 | Paroxysmal tachycardia | I47 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 108 | Atrial fibrillation and flutter | I48 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 109 | Other cardiac arrhythmias | I49 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 110 | Complications and ill-defined descriptions of heart disease and other heart disorders in diseases classified elsewhere | I51–52 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 111 | Cerebrovascular diseases | I62,I65–I68 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 112 | Sequelae of cerebrovascular disease | I69 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 113 | Atherosclerosis | I70 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 114 | Aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection | I71 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 115 | Diseases of arteries, arterioles and capillaries | I72, I74, I77–I79 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 116 | Other peripheral vascular diseases | I73 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 117 | Phlebitis, thrombosis of the portal vein and others | I80–I82 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 118 | Varicose veins of lower extremities | I83 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 119 | Esophageal varices (chronic), varicose veins of other sites, other disorders of veins, nonspecific lymphadenitis, other noninfective disorders of lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes, other and unspecified disorders of the circulatory system | I85–I99, except I89 and I95 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 120 | Bronchitis, not specified as acute or chronic, simple and mucopurulent chronic bronchitis, and unspecified chronic bronchitis | J40–J42 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 121 | Emphysema | J43 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 122 | Bronchiectasis | J47 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 123 | Other diseases of the respiratory system | J60–J84; J95, J97–J99 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 124 | Inguinal hernia | K40 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 125 | Ventral hernia | K43 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 126 | Crohn’s disease | K50 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 127 | Ulcerative colitis | K51 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 128 | Other noninfective gastroenteritis and colitis | K52 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 129 | IBS | K58 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 130 | Other functional intestinal disorders | K59 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 131 | Diseases of liver, biliary tract and pancreas | K71–K77; K86–K87 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 132 | Infectious arthropathies | M01–M03 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 133 | Polyarthrosis (arthrosis) | M15 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 134 | Coxarthrosis (arthrosis of hip) | M16 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 135 | Gonarthrosis (arthrosis of knee) | M17 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 136 | Arthrosis of first carpometacarpal joint and other arthrosis | M18–M19 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 137 | Acquired deformities of fingers and toes | M20 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 138 | Other acquired deformities of limbs | M21 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 139 | Disorders of patella (knee cap) | M22 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 140 | Internal derangement of knee | M230, M231, M233, M235, M236, M238 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 141 | Derangement of meniscus due to old tear or injury | M232 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 142 | Internal derangement of knee, unspecified | M239 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 143 | Other specific joint derangements | M24, except M240–M241 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 144 | Other joint disorders, not elsewhere classified | M25 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 145 | Systemic connective tissue disorders | M30–M31,M35-M36 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 146 | Systemic lupus erythematosus | M32 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 147 | Dermatopolymyositis | M33 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 148 | Systemic sclerosis | M34 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 149 | Kyphosis, lordosis | M40 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 150 | Scoliosis | M41 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 151 | Spinal osteochondrosis | M42 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 152 | Other deforming dorsopathies | M43 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 153 | Other inflammatory spondylopathies | M46 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 154 | Spondylosis | M47 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 155 | Other spondylopathies and spondylopathies in diseases classified elsewhere | M48, M49 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 156 | Cervical disc disorders | M50 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 157 | Other intervertebral disc disorders | M51 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 158 | Other dorsopathies, not elsewhere classified | M53 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 159 | Dorsalgia | M54 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 160 | Disorders of muscles | M60–M63, except M600 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 161 | Synovitis and tenosynovitis | M65 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 162 | Disorders of the synovium and tendon | M66–68 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 163 | Soft tissue disorders related to use, overuse and pressure | M70 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 164 | Fibroblastic disorders | M72 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 165 | Shoulder lesions | M75 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 166 | Enthesopathies of the lower limb, excluding the foot | M76 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 167 | Other enthesopathies | M77 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 168 | Rheumatism, unspecified | M790 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 169 | Myalgia | M791 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 170 | Other soft tissue disorders not elsewhere classified | M792– M794; M798–M799 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 171 | Other soft tissue disorders not elsewhere classified: pain in limb | M796 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 172 | Fibromyalgia | M797 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 173 | Osteoporosis in diseases classified elsewhere | M82 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 174 | Adult osteomalacia and other disorders of bone density and structure | M83, M85, except M833 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 175 | Disorders of continuity of bone | M84 | Cat. IV | (DIAG)a |

| 176 | Other osteopathies | M86–M90 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 177 | Other disorders of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | M95–M99 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 178 | Congenital malformations of the nervous, circulatory, respiratory system; cleft palate and cleft lip; urinary tract; bones and muscles; other and chromosomal abnormalities not elsewhere classified | Q00–Q07; Q20–Q37; Q60–Q99 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 179 | Congenital malformations of eye, ear, face and neck | Q10–Q18 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 180 | Other congenital malformations of the digestive system | Q38–Q45 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 181 | Congenital malformations of the sexual organs | Q50–Q56 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| No. | Mental conditions | ICD-10 | Category | Definitions |

| 182 | Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders | F04–F09 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 183 | Mental and behavioral disorders due to use of alcohol | F10 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 184 | Mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use | F11–F19 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 185 | Schizotypal and delusional disorders | F21-F29 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 186 | Mood (affective) disorders | F340, F348-F349, F38-F39 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 187 | Phobic anxiety disorders | F40 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 188 | Other anxiety disorders | F41 | Cat. II | (DIAG)a |

| 189 | Post-traumatic stress disorder | F431 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 190 | Reactions to severe stress and adjustment disorders | F432–F439 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 191 | Dissociative (conversion) disorders, somatoform disorders and other neurotic disorders | F44, F45, F48 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 192 | Eating disorders | F50 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 193 | Behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors | F51-F59 | Cat. III | (DIAG)a |

| 194 | Emotionally unstable personality disorder | F603 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 195 | Specific personality disorders | F602, F604–F609 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 196 | Disorders of adult personality and behavior | F61–F69 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 197 | Mental retardation | F70–F79 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 198 | Disorders of psychological development | F80–F89 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

| 199 | Behavioral and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence | F91–F99 | Cat. I | (DIAG)a |

DIAG: All patients, any age unless specified otherwise, that have had a minimum of one hospital or outpatient contact with one of the ICD-10 diagnosis codes of the condition within the defined inclusion time described by Categories I–IV. Both ‘open’ (ongoing treatment) and ‘closed’ (finalized treatment) contacts as well as primary (A), secondary (B) and additional (+) diagnosis are included.

HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; ICD-10: International Classification System Version 10; IBS: irritable bowel syndrome.

Examples:

Category I: Stationary to progressive chronic conditions are sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, Type 1 diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). These conditions are not expected to improve, but may remain stable or progress.

Category II: Stationary to diminishing chronic conditions are cancers and strokes. Common to these are that they are either stationary or they may have a possibility of recovering for the better.

Category III: Diminishing chronic conditions are depression, sleep disorders and varices. Here, we do not expect any of the conditions to be stationary chronic (although this may occur in a minority of the patients), and we cannot be certain that the condition will still be present 5 years after the first identified diagnosis.

Category IV: Borderline chronic conditions are hernias and ulcers, as mentioned, but also varices and eye conditions such as cataracts. They were included since they may exist for a longer time than 12 months; however, they are often treated with success and cured. Borderline chronic conditions such as stomach ulcers or hernias were discussed, but considered chronic in coherence with other research [30].

The complex definitions and medicine

The TDCR definitions define groups of ICD-codes in combination with different age groups, for some conditions (e.g. COPD, osteoporosis and diabetes). The existing TDCR definitions mostly use a 1-year inclusion period, but we expanded into the above inclusion time periods. Contrary to the TDCR definitions, diabetes was subdivided into three groups (Type I, II and others), also using medicine and age criteria, and partly inspired by Thomsen et al. [39]. Besides the TDCR-inspired conditions, other complex definitions using several registers were also constructed as the diagnoses alone by experts and clinicians were not considered sufficient to include the condition. For example, respiratory allergy, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes Type I and Type II, and COPD all had different medications included, besides the ICD-10 diagnoses, as shown in Table I.

The choice of complex conditions not sufficiently captured using the hospital discharge diagnosis alone as they were often treated in primary care, is coherent with the existing studies referenced and with most major public health conditions, but with a few more common conditions (e.g. psoriasis, ulcers, hemorrhoids, migraine, epilepsy, thyrotoxicosis and glaucoma). Medication indication codes, the labels of the prescribed medicines for the condition, were used to identify the specific condition, as some drugs have several indications (for example epilepsy and depression medicine, heart and circulatory medicine). This was done with caution, and mostly in combination with already known drugs, as their validity is not known and needs to be investigated further.

Finally, we added five groups based solely on medicine, as broad ‘condition’ categories of general interest (depression, psychosis, anxiety, heart failure and ischemic heart disease medicine). This was done to ensure the inclusion of patients from primary care who were not expected to be captured elsewhere using diagnosis codes, and where it had not been possible to use medicine to identify a specific condition, because the medicines are used for a variety of conditions.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this study provides the first complete catalogue of definitions of chronic conditions that is based on data from population-based healthcare registers. The definitions have been reviewed and ratified by physicians and epidemiologists to ensure their clinical coherence, significance, and hence, applicability for use in future studies. Further detailed descriptions of the process and medical considerations are found on the online supplementary material, including examples of the prevalence within some complex definitions, compared to non-complex definitions of the same conditions.

For this discussion, we used a suggested framework of three of seven factors of importance when assessing the value of secondary data [8]:

Completeness of registration of individuals;

Accuracy and degree of completeness of the registered data;

Size of the data source;

Registration period;

Data accessibility, availability and cost;

Data format; and

Possibilities of linkage with other data sources (record linkage).

In the following, we discuss the strengths and weaknesses of numbers 1, 2 and 4 regarding the issues of quality and validity relevant for this study. Finally, we discuss the current study in comparison with other studies and future studies.

Completeness of registration of individuals

While population-based registers by definition hold the complete data of a population, they are often only complete within specific healthcare sectors. For example, a weakness of traditional studies using hospital discharge registers is their inability to identify patients with chronic conditions who have been treated exclusively by GPs. The lack of diagnosis data from primary care may reduce the inclusion of less severe conditions that are normally not referred for hospital treatment (e.g. less severe levels of osteoporosis, COPD, Type 2 diabetes, allergies and asthma), which may only have been diagnosed and treated in primary care. In the present study, we aimed to overcome this limitation by also including prescription data when defining some of the conditions; however, some less severe conditions may still be under-reported using the definitions of the present study, amongst other reasons due to the fact that a few of the included conditions are often treated by private specialists and are not included sufficiently in the registers employed, or not diagnosed at all. The extent of under-reporting, validity and under-diagnosing is examined in other studies, with varying results of specific conditions and methods [7,55–59]. Besides the conditions mentioned above, this may include less severe conditions such as cataracts, age-related hearing loss, and less severe mental conditions like some types of anxiety or depression. This issue may lead to an underestimation of their true prevalence or other biased estimates depending on the outcomes used [60].

A disadvantage of community-based survey studies compared to register-based studies is the problem with non-responders due to people being in prison, homeless people, people living in institutions, those currently in inpatient treatment and survey non-responders in general [60]; which might lead to underestimation of more severe conditions. Thus, the strength of the definitions of the current study is an expected more complete identification of patients with chronic conditions, in particular patients with more severe conditions. Previous studies also show varying or poor overlap between register-based and self-reported data, for a number of conditions [36,61,62]. Consequently, register-based studies contrast with and complement community-based survey studies.

The accuracy and degree of completeness of the registered data

Although misclassification and non-registration of a diagnosis are well-known issues in community-based surveys, due to incorrect self-reported conditions, forgotten reports of past disorders, etc. [60]; similar limitations may also exist in register-based studies, regarding the accuracy of the diagnosis. One reason is the different coding practices for diagnoses, as well as incomplete coding practices between or even within hospitals [8,12]. In addition, non-reports of conditions, clinical disagreements and different interpretation of the ICD-10 diagnostic inclusion criteria may affect registration [8,12]. Hence, the risks of misclassification are known for some complex, multifaceted conditions [63,64], but it is also the case that some common and well-defined conditions are not always sufficiently reported in the NPR, according to an older study [65].

Furthermore, since the NPR is also used for monitoring the productivity of the individual hospital departments, economic incentives might bias the coding practice towards more costly diagnoses and treatments [16]. Yet nothing suggests a systemic bias in misclassification for all conditions, and the validity of several diagnoses that have previously been examined using medical records as a gold standard were reported to be high [19,60,66–70]; however, the validity of the diagnoses appear to vary across conditions [59], although we have sought to incorporate experience from existing validated conditions into the definitions. Caution is therefore advised using the definitions, and further validation and ongoing adjustment of the algorithms are warranted, since coding practices for diagnoses and the completeness of data can change over time.

Another issue in register-based studies is the lack of accuracy when using non-diagnosis registers from the primary sector. Since medication, services and registered treatments are often used for a variety of conditions, these cannot always be used alone as reliable predictors. Thus, the use of, for example, medication to define conditions has only been applied for specific cases, and definitions were developed based on a clinical judgment of coherence between the medication and conditions. For instance, Type 1 diabetes was defined as having a Type 1 diagnosis and insulin use.

As around a quarter of the medication, on average, is missing yearly indication codes, all from before 2004, and the validity of the existing medication indication codes may be questionable, these should be (and were) used conservatively. Thus, known disease-specific medication was preferred and included without indication codes where possible, such as for thyrotoxicosis, diabetes, lipid disturbances, Parkinson’s disease, hypertension, respiratory allergy and more; however, for several conditions such as depression, bipolar affective disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), heart failure, epilepsy and hemorrhoids, there was a necessity to use indication codes to differentiate different conditions from non-disease medicine. Since the completeness of indication codes is low, these conditions will properly underestimate the true prevalence; however, since the alternative was not using the medicine given, this still represents an improvement from the alternative of using diagnosis alone, if the condition is often treated in primary care or by private specialists.

The registration period

The main issue regarding the registration period is the potential risk of changes over time in diagnostic criteria that may bias the registrations [8,12]. This is mainly solved by excluding ICD-8 and solely using ICD-10, but there may still be changes within ICD-10 diagnostic criteria over the period since 1994.

The changing of diagnostic criteria is a particular challenge for studies using longer time periods than here [8]; which is why we suggest limiting longer inclusion times to a minimum, in order to ensure accuracy. For example, we reduced the inclusion time to 5 years for epilepsy, as well as requiring a minimum of two hospital diagnoses, since the risk of misclassification (besides high variability in chronicity) was considerable [45,46,71]. The issues are even more prevalent for more disputed and complex conditions; for example chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), a severe, long-term chronic and common condition affecting 0.2–0.4% of the population, but is only reported for 0.014 per cent in the NPR [63]. In the case of CFS, cultural interpretation of the condition and differences across countries might also affect the registrations [63]. In essence, this will bias results, but cannot be managed before clinical practice is changed.

Comparisons with other studies

The strength of the current study is that the definitions were reviewed and ratified by physicians and epidemiologists, and included existing studies and medical experts, enhancing their clinical relevance. The conditions were assessed individually, and it was decided to focus on the conditions needing complex definitions and the use of several registers to ensure the most accurate representation and inclusion. Furthermore, already established register-based definitions, created by specialists in their field, were used as inspiration, which may increase the transferability and comparability of those definitions presented here.

As stated above, there is no uniform government or professionally advised definition of ‘chronic condition’ in use, nor any fully suitable definition for register studies, since no existing definitions set the maximum time limits of chronicity. Thus, an advantage of this study was the production of the four clinically evaluated and differentiated categories of chronicity, with different inclusion times. In addition, previous Scandinavian register studies had usually used a 1–5-year inclusion time, often limited by the maximum data length available, with some only 1 year depending on the purpose and some recommending more; and for a limited and selected variety of conditions or more broadly defined disease groups, compared to the present study [4,9,10,12,72]. Hence, one of the obvious strengths and new innovations of the current study compared to other register studies were the long register time used, as well as the four differentiated time inclusion categories used on all conditions [2,4,9–12]. The relatively longer inclusion time enhances the possibility of including several conditions, since it was expected that, due to severity, the majority of patients with chronic conditions would at some time be reported as inpatients or outpatients in hospitals, or by medications and services.

Moreover, an obvious benefit compared to the previous studies was the large number of conditions included in this single study. While previous register studies mostly identify up to approximately 15 conditions [2,4,9–13], the purpose of this study was to include most possible ICD-10-defined chronic conditions into one of these groups of conditions, including both somatic and psychiatric conditions.

Summary and future studies

In summary, the definitions were as a minimum expected to provide a lower limit of prevalence in future studies, especially for some of the less severe conditions, because the registers used do not account for individuals not seeking treatment. On the contrary, more severe conditions that are most often treated are expected to have a higher accuracy, compared to other studies and study designs, even though there may be inaccuracies and differences in the coding of diagnoses in the NPR [16]. In general, it was expected that the definitions will produce reasonably representative estimates concerning the consequences and epidemiology of the majority of chronic conditions, and be free of self-reported bias; however, an ongoing revision and thorough clinical validation of specific conditions using for example clinical records [8] is needed by researchers in their field, to ensure improvement in the validity of the definitions. We also recommend that future studies should explore the extent of possible underestimation or overestimation of the prevalence of less severe conditions, using the definitions and differences for self-reported conditions. Further studies should also explore how possible underestimation can be counteracted by including self-reported community-based surveys for the less severe conditions, if available [10,36], as well as methods for counteracting the lack of ICD-10 diagnosis accuracy when using surveys. Additionally, so far the definitions cannot be applied for incidence studies using the four categorizations; thus, future studies should investigate how the definitions are best applied within incidence studies. At this time, the authors recommend using the defined ICD-10 codes and/or medications, in combination with the chosen incidence timeframe wherein only new incidences are included. Moreover, future studies should also investigate how to apply a multimorbidity framework, as suggested by other studies [73–75]. Although a simple approach defining multi-morbidity as having two or more conditions could easily be applied, it is recommended that future studies also identify the patterns or clusters of comorbidities, as these are expected to vary in severity and to be of importance in unfolding the burden of chronic disease.

This study provides a comprehensive catalogue of ICD-10-based definitions. The definitions can be used in national monitoring of the prevalence of chronic conditions, as well as estimation of the HRQoL associated with a condition, for example, through the use of the National Health Profiles [31]. Although the definitions are created for long term data series and registers that are mostly availably in Scandinavian countries, the ICD-10 groupings and the use of ATC-medicine can still be adopted for use in medico-administrative data in other countries that are based on both public and private registers, while the inclusion times must be adjusted according to the specific time series available. In the end, these definitions are expected to enable policy makers to assess the burden of chronic conditions in more detail, with accuracy, and for more conditions than other studies for comparison; and without the burden of using several and often non-comparable, different studies and estimates.

Conclusions

This study provides the results and the methodology behind the creation of a compilation of definitions for a variety of ICD-10 register-based groups of chronic conditions, which is, to the authors’ knowledge, the largest currently compiled.

The prevalence rates and HRQoL estimates based on the definitions presented here will be investigated in planned future studies; and will thus provide important information on the burden of illness for use in etiologic studies, health economics and other research areas, as well as in healthcare planning.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Ib Rasmussen, of the North Denmark Region Psychiatry, Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark, for reviewing and ratifying the four categorizations of chronicity and the register definitions and assessments, regarding the chronic psychiatric conditions. Also, John Hyltoft of the North Denmark Region provided valuable information regarding treatment of conditions, medicines, diagnostic use in general practice, chronicity of conditions; and he commented on suggested chronicity inclusion times. This was used for assessing which conditions needed complex definitions, chronicity and possible use of different registers for inclusion, which was much appreciated. Likewise, we thank Kaare Haurvig Palnum of the Department of Ophthalmology, Regionshospitalet Holstebro, Denmark, for reviewing and ratifying the four categorizations of chronicity, and the register definitions and assessments regarding the chronic diseases of the eye and adnexa. We are also grateful to Kaspar René Nielsen of the Department of Clinical Immunology, Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark, for help with the identification, categorization and review of chronic diseases within the ICD-10 disease group ‘A’ and ‘B’. Finally, our thanks to Martin Bach Jensen at the Department of Clinical Medicine, Aalborg University, Denmark, and the Research Unit for General Practice in Aalborg, for his important review and input regarding the diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This work was supported by the North Denmark Region, Danish Public Tax Foundation and Aalborg University.

Supplemental material: Online supplementary data is available at http://sjp.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- [1]. Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Ward BW, et al. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2011. Vital Heal Stat 2012;10:1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Esteban-Vasallo M, Dominguez-Berjon M, Astray-Mochales J, et al. Epidemiological usefulness of population-based electronic clinical records in primary care: Estimation of the prevalence of chronic diseases. Fam Pract 2009;26:445–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Garrett N, Martini EM. The boomers are coming: A total cost of care model of the impact of population aging on the cost of chronic conditions in the United States. Dis Manag 2007;10:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Wiréhn A-BE, Karlsson HM, Carstensen JM. Estimating disease prevalence using a population-based administrative healthcare database. Scand J Public Health 2007;35:424–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Epping-Jordan J, Pruitt S, Bengoa R, et al. Improving the quality of health care for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Sundhedsstyrelsen [National Board of Health]. Kronisk sygdom: Patient, sundhedsvæsen og samfund [Chronic Conditions: Patient, health care and society], www.sst.dk/publ/Publ2005/PLAN/Kronikere/Kronisk_sygdom_patient_sundhedsvaesen_samfund.pdf (2005, accessed 1 May 2015).

- [7]. Frost M, Wraae K, Gudex C, et al. Chronic diseases in elderly men: Underreporting and underdiagnosis. Age Ageing 2012;41:177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Sorensen HT, Sabroe S, Olsen J. A framework for evaluation of secondary data sources for epidemiological research. Int J Epidemiol 1996;25:435–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Klinisk Epidemiologisk Afdeling [Department of Clinical Epidemiology]. Sygehuskontakter og lægemiddelforbrug for udvalgte kroniske sygdomme i Region Nordjylland [Hospital contacts and drug consumption for selected chronic diseases in North Jutland], www.kea.au.dk/file/pdf/36.pdf (2007, accessed 1 May 2014).

- [10]. Robinson KM, Juel Lau C, Jeppesen M, et al. Kroniske sygdomme - forekomst af kroniske sygdomme og forbrug af sundhedsydelser i Region Hovedstaden [Chronic diseases: Prevalence of chronic diseases and use of health services in the Capital Region], www.regionh.dk/fcfs/publikationer/Documents/Kroniskesygdomme-forekomstafkroniskesygdommeogforbrugafsundhedsydelseriRegionHovedstaden.pdf (2012, accessed 2 May 2014).

- [11]. Statens Serum Institute. Monitorering af kronisk sygdom hos Statens Serum Institut [Monitoring of chronic disease at Statens Serum Institute], www.ssi.dk/Sundhedsdataogit/Sundhedsvaesenetital/Monitoreringer/Kronisksygdom/Monitorering-Kronisksygdom2011.aspx (2012, accessed 10 November 2014).

- [12]. Sundhedsstyrelsen [Danish National Board of Health]. Beskrivelse af Sundhedsstyrelsens monitorering af kronisk sygdom [Description of the National Board of Health’s monitoring of chronic disease], www.ssi.dk/~/media/Indhold/DK-dansk/Sundhedsdataogit/NSF/Dataformidling/Sundhedsdata/Kroniker/MetodebeskrivelseafSundhedsstyrelsensmonitoreringafkronisksygdom.ashx (2012, accessed 15 June 2015).

- [13]. Carstensen B, Kristensen JK, Marcussen MM, et al. The National Diabetes Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Hommel K, Rasmussen S, Madsen M, et al. The Danish Registry on Regular Dialysis and Transplantation: Completeness and validity of incident patient registration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25:947–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Hvidberg MF, Ehlers L, Petersen KD. Catalogue of EQ-5D scores for chronic conditions in Denmark. Value Heal 2013;16:A595. [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Statens Serum Institute. Landspatientregisteret [The National Patient Registry]. Statens Serum Institute, www.ssi.dk/Sundhedsdataogit/Registreogkliniskedatabaser/Denationalesundhedsregistre/Sygdommeleagemidlerbehandlinger/Landspatientregisteret.aspx (2015, accessed 26 February 2015).

- [18]. Johnsen SP, Overvad K, Sørensen HT, et al. Predictive value of stroke and transient ischemic attack discharge diagnoses in The Danish National Registry of Patients. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:602–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Uggerby P, Østergaard SD, Røge R, et al. The validity of the schizophrenia diagnosis in the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register is good. Dan Med J 2013;60:A4578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:54–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Sahl Andersen J, De Fine Olivarius N, Krasnik A. The Danish National Health Service Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:34–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Statens Serum Institute. Sygesikringsregister [The National Health Service Registry]. www.ssi.dk/Sundhedsdataogit/Registreogkliniskedatabaser/Denationalesundhedsregistre/Sundhedsokonomifinansiering/Sygesikringsregister.aspx (2013, accessed 26 August 2015).

- [23]. Wallach Kildemoes H, Toft Sorensen H, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:38–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Statens Serum Institute. Om Lægemiddelstatistikregisteret [Pharmaceutical Statistics Register], www.ssi.dk/Sundhedsdataogit/Registreogkliniskedatabaser/Denationalesundhedsregistre/Sygdommeleagemidlerbehandlinger/Laegemiddelstatistikregisteret.aspx (2013, accessed 1 May 2014).

- [25]. Statens Serum Institute. CPR-registret [The Danish Civil Registration system], www.ssi.dk/Sundhedsdataogit/Registreogkliniskedatabaser/Denationalesundhedsregistre/Personoplysningersundhedsfagligbeskeaftigelse/CPR-registeret.aspx (2015, accessed 1 May 2014).

- [26]. Pedersen CB, Gøtzsche H, Møller JO, et al. The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull 2006;53:441–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V. Preference-based EQ-5D index scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Decis Mak 2006;26:410–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Paez KA, Zhao L, Hwang W. Rising out-of-pocket spending for chronic conditions: A ten-year trend. Health Aff 2009;28:15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Hwang W, Weller W, Ireys H, et al. Out-of-pocket medical spending for care of chronic conditions. Health Aff 2001;20:267–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Sullivan PW, Lawrence WF, Ghushchyan V. A national catalog of preference-based scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Care 2005;43:736–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Christensen AI, Ekholm O, Glumer C, et al. The Danish National Health Survey 2010. Study design and respondent characteristics. Scand J Public Health 2012;40:391–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Hayes VS, Cristoffanini SL, Kraemer SR, et al. Sundhedsprofil 2013 - trivsel, sundhed og sygdom i Region Nordjylland [Health profile 2013: Well-being, health and disease in North Jutland], www.rn.dk/sundhedsprofil (2014, accessed 20 June 2015).

- [33]. Bartels P. Om RKKP (About the The Danish Clinical Registries), www.rkkp.dk/om-rkkp/ (2015, accessed 25 October 2014).

- [34]. Kliniske databaser – temanummer [Clinical databases – thema issue]. Ugeskrift for laeger [The Journal of the Danish Medical Association]. 2012;42:2493–584, http://ugeskriftet.dk/blad/42-2012. [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Lau CJ, Lykke M, Andreasen AH, et al. Sundhedsprofil 2013 - Kronisk Sygdom [Health profile 2013: Chronic disease], www.regionh.dk/fcfs/publikationer/Documents/Sundhedsprofil2013-Kronisksygdom.pdf (2015, accessed 2 July 2015).

- [36]. Robinson KM, Juel Lau C, Jeppesen M, et al. Kroniske sygdomme – hvordan opgøres kroniske sygdomme [Chronic disease: How chronic disease is defined], www.regionh.dk/fcfs/publikationer/nyhedsbreve/setember-2014/PublishingImages/Sider/NyKroniske_sygdomme_metoderapport.pdf (2011, accessed 5 May 2014).

- [37]. Statens Serum Institute. Register for udvalgte kroniske sygdomme (RUKS) – høringsmateriale og definitioner [Register of selected chronic conditions (RUKS): Consultation material and definitions], https://hoeringsportalen.dk/Hearing/Details/36878 (2014, accessed 22 May 2015).

- [38]. Statens Serum Institute. De reviderede udtræksalgoritmer til brug for dannelse af Register for Udvalgte Kroniske Sygdomme og svære psykiske lidelser (RUKS) af marts 2015 [The revised algorithms of selected chronic diseases and severe mental disorders (RUKS) of March 2015], http://sundhedsdatastyrelsen.dk/da/tal-og-analyser/analyser-og-rapporter/sygdomme/multisygdom (2015, accessed 1 March 2016).

- [39]. Thomsen RW, Baggesen LM, Svensson E, et al. Early glycaemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes and initial glucose-lowering treatment: a 13-year population-based cohort study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015;17:771–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Hansen S. Dansk Neuro Onkologisk Register aarsrapport 2011 [Danish Neuro-oncology Registry annual report 2011], www.dnog.dk (2012, accessed 30 September 2014). [PubMed]

- [41]. Gjerstorff ML. The Danish Cancer Registry. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:42–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Rossing P, Adolfsen H, Nielsen KA. Dansk voksen diabetes database – datadefinitioner (2015) [Danish adult diabetes register: Data definitions (2015)], www.kcks-vest.dk/kliniske-kvalitetsdatabaser/voksendiabetes/ (2015, accessed 6 May 2015).

- [43]. Green A, Sortsø C, Jensen PB, et al. Validation of the Danish national diabetes register. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:5–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Videbech P, Delueran A, Haller L. Dansk depressionsdatabase – datadefinitioner (2013) [The Danish depression Register – datadefinitions (2013)], www.kcks-vest.dk/kliniske-kvalitetsdatabaser/dansk-depressionsdatabase/ (2013, accessed 17 June 2014).

- [45]. Christensen J, Vestergaard M, Pedersen MG, et al. Incidence and prevalence of epilepsy in Denmark. Epilepsy Res 2007;76:60–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Russell MB, Lühr Hansen B, Witting N, et al. Epilepsi [Epilepsy], www.sundhed.dk/sundhedsfaglig/laegehaandbogen/neurologi/tilstande-og-sygdomme/kramper/epilepsi/ (2015, accessed 5 August 2015).

- [47]. Kolko M, Horwitz A, Thygesen J, et al. The prevalence and incidence of glaucoma in Denmark in a fifteen year period: A nationwide study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0132048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Özcan C, Vive J, Davidsen M, et al. Dansk Hjerteregister – aarsberetning 2014 [Danish Heart Registry: Annual report 2014], www.si-folkesundhed.dk/Udgivelser/B%C3%B8gerograpporter/2015/DanskHjerteregisters%C3%85rsberetning2014.aspx (2015, accessed 16 July 2015).

- [49]. Ekholm O, Hesse U, Davidsen M, et al. The study design and characteristics of the Danish national health interview surveys. Scand J Public Health 2009;37:758–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Olesen JB, Lip GYH, Hansen ML, et al. Validation of risk stratification schemes for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation: Nationwide cohort study. Brit Med J 2011;342:d124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Egstrup K, Schjødt I, Nakano A. Dansk hjertesvigts database – datadefinitioner for NIP-hjerteinsufficiens (2011) [The Danish heart failure register: Data definitions (2011)], www.kcks-vest.dk/kliniske-kvalitetsdatabaser/hjertesvigt/ (2011, accessed 20 March 2015).

- [52]. Gyllenborg J, Zielke S, Ingeman A. Dansk apopleksiregister – datadefinitioner (2014) [Danish stroke register: Data definitions (2014)], www.kcks-vest.dk/kliniske-kvalitetsdatabaser/apopleksi/ (2014, accessed 29 December 2014).

- [53]. Lange P, Sorknæs AD, Abildtrup Nielsen K. Dansk register for Kronisk Obstruktiv Lungesygdom DrKOL – datadefinitioner 2014 [Danish register of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Data definitions 2014], www.kcks-vest.dk/kliniske-kvalitetsdatabaser/kol/ (2014, accessed 5 January 2015).

- [54]. Smidth M, Sokolowski I, Kærsvang L, et al. Developing an algorithm to identify people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) using administrative data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012;12:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]