Abstract

Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channels (ENaC) regulate fluid balance in the alveoli and are regulated by oxidative stress. Since glutathione (GSH) is the predominant antioxidant in the lungs, we proposed that changes in glutathione redox potential (Eh) would alter cell signaling and have an effect on ENaC open probability (Po). In the present study, we used single channel patch-clamp recordings to examine the effect of oxidative stress, via direct application of glutathione disulfide (GSSG), on ENaC activity. We found a linear decrease in ENaC activity as the GSH/GSSG Eh became less negative (n = 21; P < 0.05). Treatment of 400 μM GSSG to the cell bath significantly decreased ENaC Po from 0.39 ± 0.06 to 0.13 ± 0.05 (n = 8; P < 0.05). Likewise, back-filling recording electrodes with 400 μM GSSG reduced ENaC Po from 0.32 ± 0.08 to 0.17 ± 0.05 (n = 10; P < 0.05), thus implicating GSSG as an important regulatory factor. Biochemical assays indicated that oxidizing potentials promote S-glutathionylation of ENaC and irreversible oxidation of cysteine residues with N-ethylmaleimide blocked the effects of GSSG on ENaC Po. Additionally, real-time imaging studies showed that GSSG impairs alveolar fluid clearance in vivo as opposed to GSH, which did not impair clearance. Taken together, these data show that glutathione Eh is an important determinant of alveolar fluid clearance in vivo.

Keywords: Cys thiol, redox potential, oxidative stress, alveolar flooding

oxidative stress is defined as a disruption of redox signaling and control (29), and studies show that oxidative stress occurs in many lung diseases. The lung is continuously exposed to oxygen and as a result has developed a cache of antioxidant defenses to combat a potential threat from oxidants. The lower respiratory tract, where oxygen exchange occurs, contains large amounts of the antioxidant glutathione (GSH) with ∼96% in the reduced form (9). Inside the cell, the main biological effect of GSH is catalyzed by glutathione peroxidase, which reduces hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to water. Generally speaking, GSH can be directly oxidized and can form numerous adducts with protein. However, the oxidation of GSH also leads to glutathione disulfide (GSSG) formation. As such, the calculated GSH/GSSG redox potential (Eh) of epithelial lining fluid (ELF) is a good indicator of the lungs' ability to handle an oxidative insult (2, 29, 30). The GSH/GSSG Eh in the ELF of normal healthy lung is approximately −205 mV (6) and has been shown to shift towards more oxidized states in the lungs of smokers (32) and alcoholics (6, 52). Reduced (more negative) Eh values are regarded as healthy normal values, whereas greater oxidation (more positive redox values) are associated with disorders such as type 2 diabetes (9, 29, 42), neurodegenerative diseases (7), cardiovascular disease (2), cystic fibrosis (41), and some cancers (44).

Because of the putative predictive value of the calculated GSH/GSSG Eh, and the possibility that glutathione disulfide serves as an important signaling molecule, it is important to examine how ion transport changes following shifts in Eh. In the lower respiratory tract, epithelial sodium channels (ENaC), in part, regulate ELF volume and composition. ENaC is composed of heterotrimeric subunits (α-, β-, and γ-), which can be assembled in different combinations resulting in a channel subtype that is highly selective for Na+ ions (HSC) or a subtype that can transport multiple cations (NSC) (8, 24). Heterologous overexpression of α-ENaC subunit alone produces functional channels (25, 26). Importantly, transgenic mice lacking normal expression of α-ENaC die within 48 h of birth due to an inability to clear lung fluid (22). In humans, inhibition of lung ENaC activity leads to impaired fluid clearance resulting in pulmonary edema (37, 40), and increased activity can cause drying of the lung and lead to mucus build up as seen in cystic fibrosis (27, 36, 39). We have previously shown that H2O2 is an activator of ENaC activity in the lung (16), while others have reported similar findings in kidney cells (35). However, the role of reactive oxygen species generation and resident antioxidants in edematous lung injury and their interplay with fluid regulation remains unclear. Since the redox state of the lung can be significantly impacted by the environment (12, 15, 16), it is important to examine the effect of prooxidants and antioxidants in the lung.

Because the redox state is a critical component that differentiates healthy from diseased lung, we examined the effect of altering the redox state on the rate of ion transport via ENaC in lung cells. Specifically, we performed cell-attached single channel recordings from primary alveolar type 1 (T1) and type 2 (T2) cells isolated from rat lungs or directly from lung tissue slices. We found that oxidized redox potentials corresponded with decreases in ENaC activity. Biochemical studies indicated a role for GSH in the signaling pathway via S-glutathionylation, and in vivo experiments, where mouse lungs were instilled with GSSG, showed impeded fluid clearance. Taken together, these results suggest that changes in Na+ channel activity, and hence lung fluid balance, are likely to be redox dependent.

METHODS

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (8–12 wk old) were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) and used as a source for lung tissue slices and primary cell isolation. Female C57Bl/6J mice (6–8 wk old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). All procedures conformed to National Institutes of Health animal care and use guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University.

Reagents.

γ-l-Glutamyl-cysteinyl-glycine (GSH), l-glutathione oxidized (GSSG), and all other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or as indicated.

Isolation of primary alveolar type 2 cells.

Rat primary alveolar T2 cells were isolated using a previously published protocol (20). Briefly, the lungs were perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) via the pulmonary artery and then extracted en bloc. The trachea was cannulated and the lungs instilled with elastase solution (96 units in 40 ml of saline solution). The lung lobes were excised, minced into 1- to 2-mm pieces, and sequentially filtered through 100- and 40-μm filters to produce a cell suspension. Cell suspensions were centrifuged at 1,200 rpm and were resuspended in DMEM/F-12 Ham's media containing gentamycin. The cell suspension was added to rat IgG-coated plates and panned for 1 h at 37°C. The cell suspension was collected and centrifuged, and the cell number was counted. Approximately 5 × 104 cells were seeded onto Snapwell inserts (Corning, Lowell, MA) and fed DMEM/F-12 Ham's media (supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 μM dexamethasone, 84 μM gentamicin, and 20 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin). Air-interface was established within 12 h, and T2 cells were used within 48 h for the experiments.

Rat lung slice preparation.

Lung slice preparation was performed as previously described (13, 14, 16, 20, 21) to access alveolar type 1 cells for patch analysis. Briefly, lungs were perfused via the pulmonary artery with 75 ml of PBS. Warm (35°C) 2% low-melting-point agarose in PBS was intratracheally instilled into the lungs to expand the air spaces and provide support for the tissue during the slicing process. Excised lungs were removed en bloc and chilled in cold PBS (4°C) to solidify the agarose, and a small block of tissue was separated from the largest lobe of the lung and mounted using surgical-grade cyanoacrylate adhesive onto a Vibratome (model VT1000S; Leica Microsystems). Lung slices were prepared (175–225 μm) from agarose-instilled rat lungs and transferred to 50:50 DMEM/F-12 (containing 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 μM dexamethasone, 84 μM gentamicin, and 20 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin). Lung slices were washed before bathed in patch-clamp solution containing the following (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, and 10 HEPES, at pH 7.4. T1 cells were patched within 6 h of the initial tissue preparation.

Single-channel patch-clamp analysis of ENaC in alveolar cells.

Cell-attached recordings were established on the apical membrane of T1 and T2 cells, which are morphologically distinct. T1 cells comprise >95% of the alveolar surface and were approached from the luminal surface after preparing lung tissue sections, which exposes a hemisection of the alveolus as recently described (21). Polished micropipettes were pulled from filamented borosilicate glass capillaries (TW-150; World Precision Instruments) with a two-stage vertical puller (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). Patch-clamp electrode and saline solution contained the following (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, and 10 HEPES, with pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The resistance of fire-polished pipettes was between 5 and 10 MΩ when filled with this electrode solution. Channel currents were sampled at 1 kHz with an Axopatch 1B patch-clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and filtered at 200 Hz with a low-pass Bessel filter. Data were recorded by a computer running AxoScope 10.2 software (Molecular Devices). As a measure of ENaC activity, we calculated the product of the number of channels times the open probability (NPo) within a patch using pCLAMP 10.2 software (Molecular Devices) as previously described (53). Voltages are given as the negative of the patch-pipette potential (−Vp), which is the displacement of the patch potential from the resting potential. Positive potentials represent depolarization, and negative potentials represent hyperpolarization of the cell membrane away from the resting potential. Chord conductances were calculated between hyperpolarizing and depolarizing potentials for NSC channels. All drug treatments were prepared in patch-clamp solution.

Glutathione measurements via HPLC.

GSH/GSSH Eh was determined with HPLC analysis as outlined previously (33) by the Emory and Children's Pediatric Research Center Biomarkers Core (Atlanta, GA). In brief, GSH and GSSG samples were aliquoted into tubes containing 21 μl of a diluted preservative with a final concentration of 5% perchloric acid, 0.1 M boric acid, 6.7 mM iodoacetic acid, and 5 nM γ-glutamyl-glutamate. Samples were then assayed by HPLC as S-carboxymethyl, N-dansyl derivatives using γ-glutamyl-glutamate as an internal standard. GSH and GSSG fractions were treated with dansyl chloride and the dansylated derivatives were separated using an amino μBondaPak column (Waters, Milford MA) with fluorescent detection. The lower limits of detection were 15 fmol/μl for rGSH. Levels of S-glutathionylation (Pr-SSG) were determined via methods described in Jones et al. (31) through reduction of proteins followed by rederivatization and HPLC analysis. To minimize operational variability, all samples from this study were analyzed within the same HPLC run. Interassay coefficient of variability was determined by performing HPLC analysis on a mixture of standards including cysteine, cystine, rGSH, and GSSG. This mixture was analyzed immediately before, in the middle, and at the end of sample set analysis. Based on this cocktail of standards, the interassay coefficient of variability was calculated at 1%.

Glutathione redox buffers.

Glutathione solutions were prepared immediately before use in electrode buffer, as previously reported in (49). Based on the Nernst equation {Eh = Eo + RT/2F ln [(GSSG)/(GSH)2]} for calculating GSH/GSSG redox state, the following proportions of GSH and GSSG shifts Eh accordingly: 1) GSH (400 μM) + GSSG (1.5 nM) = −200 mV Eh; 2) GSH (300 μM) + GSSG (100 μM) = −150 mV Eh; and 3) GSH (12 μM) + GSSG (400 μM) = −75 mV Eh. These ratios have been verified by HPLC analysis of the reagents (see above) and corrected for pH = 7.4. Glutathione solutions were added to the extracellular bath, or back-filled in the electrode recording solution as indicated.

Fluorescent reactive oxygen species detection.

Cells were treated with GSH or GSSG as indicated for 1 h before detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Amplex Red was used to determine H2O2 levels in the cell culture supernatant as previously described (12, 16). Isolated rat T2 cells were seeded to tissue culture plates and exposed to mixtures of GSH/GSSG corresponding to specific redox potentials (verified by HPLC). After 1 h of exposure, the cell supernatants were removed and the Amplex Red assay was performed per the manufacturer's recommendations. Dihydroethidium (DHE; Invitrogen) was used as a quantitative measure of O2·− production in live lung tissue slices as described previously (12, 16, 20). Lung tissue slices were divided into treatment groups and exposed to mixtures of GSH/GSSG corresponding to specific redox potentials (as determined by HPLC). The slices were then incubated with 10 μM DHE in PBS solution for 30 min in a light-protected chamber, fixed, and mounted on slides using Vectashield to prevent photo-bleaching over time. Thin optical sections (1-μmA z-stack images) were obtained using an Olympus BX61WI microscope designed for confocal fluorescence observations alongside FluoView FV10-ASW 1.7 software. The entire field of view and all stacks were used to quantify the relative light units reported.

Biotinylated glutathione ethyl ester assay.

Alveolar T2 cells were isolated from rat lung as described previously and the biotinylated glutathione ethyl ester (BioGEE) assay was performed as described by Sullivan et al. (47). Briefly, cells were divided into 3 treatment groups (control, 20 μM H2O2, and 20 μM diamide for 15 min). All groups of cells were incubated with 0.5 mM biotinylated glutathione for 1 h. Cells were then lysed (in RIPA buffer containing 149 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaPO4, 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 6 mM deoxycholic acid, 5 μM antipain, 5 μM leupeptin, 5 μM tosyl lysyl chloromethyl ketone/tosyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone, and 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride protease inhibitors), and cells that had incorporated BioGEE were pulled down using streptavidin-agarose beads (50 μl/mg of soluble protein incubated for 30 min at 4°C with gentle shaking). Beads were pelleted and supernatants were stored to run in parallel as negative glutathionylation signal control. Beads were resuspended in PBS-0.1% wt/vol SDS containing 10 mM DTT for Western blot analysis of S-glutathionylated protein. Standard Western blot techniques were used to verify BioGEE incorporation into cell protein and, more specifically, α-ENaC subunit.

Western blot.

Lung cell lysate, immunoprecipitated α-ENaC, or BioGEE incorporated proteins were electrophoresed on 7.5% acrylamide gels and transferred to Protran nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher Schuell, Keene, NH) for labeling. Membranes were incubated with the following antibodies, as indicated in the text, for 1 h at room temperature: a 1:200-fold dilution of antibodies directed against the COOH-terminal domain of rabbit α-ENaC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); a 1:1,000-fold dilution of primary mouse anti-GSH antibody (Virogen, Boston, MA); or a 1:2,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin antibody (BD Pharmagen). Secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit or anti-mouse) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at a 1:20,000-fold dilution were applied and incubated for an additional 1 h at room temperature as needed. Chemiluminescent signal was detected using Supersignal West Dura (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and exposed using a Carestream Gel Logic 4000 Imaging Station and compatible software.

Tracheal instillation of saline and radiographic assessment of lung fluid clearance.

Tracheal instillations were performed as previously described (17, 18). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 15 mg/kg xylazine (Anased; 100 mg/m; Lloyd Laboratories, Shenandoah, IA) and 125 mg/kg ketamine (ketamine hydrochloride injection USP; 50 mg/ml; Bioniche Pharma, Lake Forest, IL) prepared in PBS (pH 7.4; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) for a final intraperitoneal injection volume of 250 μl/20 g body wt. The instillate vehicle for all experiments consisted of 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES with pH 7.4, hereafter referred to as control saline. Tracheal instillation volumes of 5 μl/g body wt (100 μl; final volume in 20 g C57Bl/6J mice) were delivered using a 26-gauge, 5/8-inch needle, and 1-ml syringe. Immediately after mice received a tracheal instillation, lung fluid clearance was assessed using radiographic imaging as previously described (17). Briefly, animals were placed in an In-Vivo Multispectral Imaging System (Bruker, Billerica, CT) connected to a rodent nose cone with continuous anesthesia (1.5 l/min isoflurane) and supplemental oxygen (100%). Animals were X-ray imaged at 5-min intervals up to 240 min with an acquisition period of 120 s. X-ray settings were as follows: 2 × 2 binding, 180-mm field of view, 149-A X-ray current, 35 kVp, and 0.4-mm aluminum filter. X-ray density was quantified using Carestream Health MI software with a 5-mm2 region of interest. In all whole animal studies, the region of interest was the left upper lobe of the lung as described by Goodson et al. (17).

Statistical analysis.

ENaC Po values were examined before and after treatment(s). Therefore, the same patch-clamp recording before drug treatment could be used as its own control, and statistical analysis was determined by paired t-test; P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Data are presented as means ± SE. Linear regression was used to determine the relationship between redox potential and ENaC Po and to determine the best fit for the current-voltage (I–V) relationship. Conductance was calculated from the slope of the regression line.

RESULTS

Redox state is important for ENaC regulation.

Because the oxidant state is altered in many lung diseases, we sought to determine the effect of altering the redox state on ENaC activity. In Fig. 1A we provide portions of a representative cell-attached single channel recording from a T2 cell under physiologic conditions (−210 mV; Fig. 1A top trace). The same cell was then exposed to 400 μM GSSG added extracellularly to create a severely oxidized environment (−75 mV), followed by return of the redox potential to a more reduced state (−213 mV) using the same cell attached patch. Point amplitude histograms indicate that application of GSSG (Eh = 75 mV) to the extracellular bath increases the likelihood of observing ENaC in a closed (0 pA) state (Fig. 1B). ENaC was less likely to be in the closed state when the redox potential was returned to −213 mV, as illustrated by the histograms in Fig. 1B. Figure 1C reports that in the open state, channel conductance (γ) = 26.6 pS and does not change under various redox environments. Figure 1D represents 12 independent observations of continual recordings in which the extracellular redox potentials were shifted from −210 to −75 mV and returned to −213 mV. Extracellular application of GSSG decreased the open probability (Po) of the epithelial sodium channel on average from 0.39 ± 0.06 to 0.13 ± 0.05. Channel Po increased to 0.38 ± 0.05 upon return of the redox potential (−213 mV). Figure 1E shows that a GSSG-induced decrease in ENaC activity was also observed in T1 cells accessed from lung tissue preparation; the Po decreased from 0.47 ± 0.06 to 0.19 ± 0.03. In Fig. 1F, we report a linear decrease in ENaC activity as the GSH/GSSG Eh became less negative (n = 21; P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Extracellular shifts in glutathione (GSH)/glutathione disufide (GSSG) glutathione redox potential (Eh) potential affect epithelial Na+ channels (ENaC) open probability (Po). A: representative portions of a trace taken from a continual cell attached patch-clamp recording of a T2 cell at a holding potential of 10 mV (−Vp) is shown. Closed states (c) are indicated by dashed line and # indicates a break from continual recording. B: point amplitude histograms were constructed from the data for each condition in A. Peaks in the distribution represent 0 or 1 open channel. C: current/voltage relationship of representative trace shown in A, with a calculated conductance (γ = 26.6 pS) that is typical of nonselective cation channels. D: dot plot graph of 12 separate T2 cells shows effects of control (−210 mV; CTR), GSSG (−75 mV), and then GSH (−213 mV) sequentially added on ENaC open probability in continual trace recordings. Individual cells are represented by open circles, and closed circles represent average ± SE. *P < 0.05. E: GSSG (−75 mV) similarly decreases ENaC Po in T1 cells. F: cell attached recordings were performed before (−205-mV redox potential) and after adding a mixture of GSH and GSSG (redox potentials ranging from −300 to −100 mV) to alveolar epithelial cells. Percent control values for individual cells (circles) were calculated by dividing open probability after the addition of GSH/GSSG by the open probability under control conditions and multiplying by 100. Open squares with error bars represent means ± SE for each redox potential. Linear regression was performed to determine the best fit relationship between redox potential and ENaC activity.

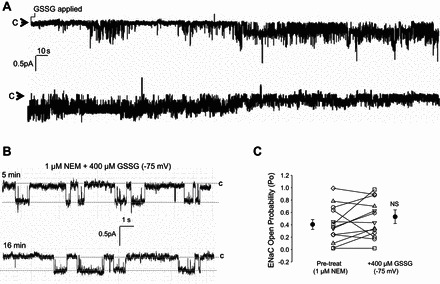

N-ethylmaleimide attenuates GSSG inhibition of ENaC activity in T2 cells.

Next, we assessed the effect of blocking disulfide bond formation, using N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and GSSG, on ENaC activity. If ENaC is posttranslationally regulated by Cys thiol modification, then pretreating cells with 1 μM NEM should attenuate the previously reported decrease in ENaC Po following positive shifts in the GSH/GSSG Eh. NEM is a small molecule that forms stable, covalent thioether bonds with sulfhydryls (e.g., reduced cysteines) keeping the sulfhydryls permanently blocked. Figure 2A shows ∼10 min of a continual recording of a cell attached patch-clamp trace of a T2 cell following GSSG application (conducted 10 min following an NEM pretreatment period that is not shown). In this representative recording, no change in ENaC activity was observed following 400 μM GSSG application to the extracellular bath in NEM pretreated cells. In Fig. 2B, we enlarged excerpts from the same single channel recording taken following 5 and 16 min post-GSSG exposure in NEM pretreated cells. Analysis of 13 independent observations shows that GSSG in the setting of NEM did not affect ENaC open probability (Fig. 2C). Together, these data suggest that S-glutathionylation, specifically by GSSG, may play a critical role in the regulation of ENaC.

Fig. 2.

N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) attenuates GSSG inhibition of ENaC. A: representative T2 single channel patch-clamp recording shows no change in ENaC activity during the 10-min observation time period in which cells were pretreated with 1 μM NEM and then 400 μM GSSG (applied where indicated). B: enlarged portion of single channel recordings at 5 min and 16 min post 400 μM GSSG treatment. In A and B, closed states are indicated by “c”, and downward deflections from the closed state indicate channel openings. C: a dot plot graph showing that the Po values did not change significantly from 0.41 ± 0.08 to 0.54 ± 0.12 in 13 independent observations.

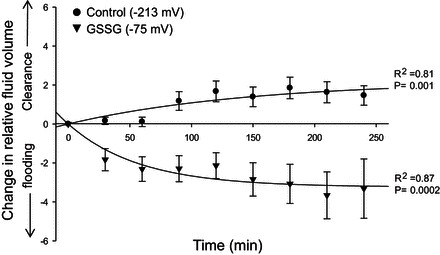

GSSG attenuates alveolar fluid clearance in vivo.

To determine the functional effects of GSSG on ENaC, mice were given a tracheal instillation of 5 μl/g body wt of GSH/GSSG with an Eh of either −213 or −75 mV and lung fluid clearance was determined as described by Goodson et al. (17) (Fig. 3). Mice exposed to a highly oxidized GSH/GSSG Eh demonstrated alveolar flooding compared with mice receiving a more reduced GSH/GSSG Eh. To describe the change in lung fluid clearance due to alterations of the glutathione redox potential we fit our data to the following model:

where F(t) represents the amount of surface fluid in the lung at time, t; K is the steady state or peak amount of lung fluid; and ka is the rate of fluid absorption. The rate of secretion was determined by dividing the peak fluid volume by the rate of absorption (K/ka). Fit parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 3.

Positive shifts in GSH/GSSG Eh decrease the rate of lung fluid clearance in vivo. C57Bl/6J mice were given a tracheal instillation (5 μl saline/mg body wt) containing either 400 μM GSH (n = 7) or 400 μM GSSG (n = 6). Fluorometric data quantified at 5-min intervals for up to 4 h, with 30-min averaged values reported. Plotted values show the effects of GSH (black circles) and GSSG (black triangles) on relative lung fluid clearance. Symbols represent means ± SE for each condition. Average data were then fit to an exponential model for fluid clearance (see text).

Table 1.

Fit parameters for fluid clearance in vivo

| −300 mV | −25 mV | |

|---|---|---|

| Peak fluid volume (K) | 2.20 ± 0.94 | −3.24 ± 0.29 |

| Rate of fluid absorption (ka) | 0.007 ± 0.005 | 0.017 ± 0.005 |

| Rate of fluid secretion (ks) | 323.97 ± 176.92 |

Values are means ± SE. The fit parameters used to determine fluid clearance over time in Fig. 3 are shown.

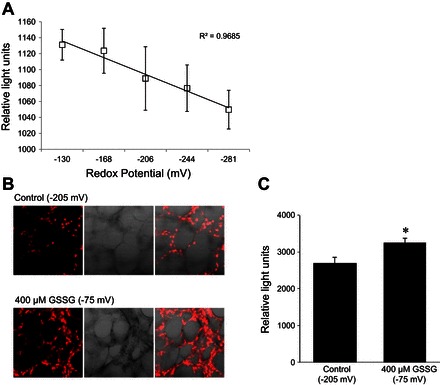

To better understand the alveolar landscape following shifts in the extracellular redox potential, we measured intracellular and extracellular ROS levels following equilibration of the extracellular bath with GSH/GSSG redox buffers. Figure 4A shows a linear relationship between altering the Eh and ROS production measured using Amplex Red reagent to detect hydrogen peroxide release in isolated rat T2 cells. Similarly, Fig. 4, B and C, shows an increase in ROS production in lung tissue slices treated under control (−205 mV) and with 400 μM GSSG (−75 mV) using DHE. Together, these data indicate that increasing extracellular GSSG content (i.e., positive increase in redox potential) can indeed alter extracellular and intracellular redox signaling.

Fig. 4.

Changes in extracellular GSH/GSSG Eh alter cellular oxidant production and intracellular redox. A: line graph demonstrating a change in extracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) from isolated rat T2 cells challenged with a range of redox potentials using Amplex Red for determining H2O2 production. B: images of live lung tissue labeled with dihydroethidium (DHE; as an indicator of O2·− production) and subjected to a highly oxidized redox potential (−75 mV) or control (−205 mV) conditions. C: bar graph quantifying an increase in intracellular ROS production (i.e., DHE intensities) in lung tissue subjected to a highly oxidized redox potential. *P < 0.05.

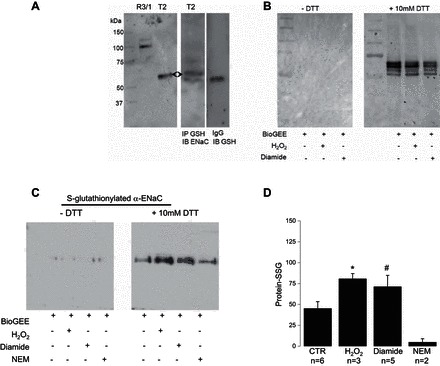

S-glutathionylation is a novel posttranslational modification of ENaC under oxidative stress.

There are two common approaches used to test S-glutathionylation of protein. The first method involves treating cells with BioGEE, a membrane permeable biotinylated glutathione ethyl ester (thus allowing for protein pull-down), alongside prooxidants to promote S-glutathionylation. Secondly, S-glutathionylated protein can be immunoprecipitated for using anti-GSH antibodies under nonreducing conditions followed by western blot detection with antibody of interest. To gain insight into the mechanism by which glutathione alters sodium channel function, we performed both. Anti-GSH antibody was used to IP proteins that have incorporated an oxidizing GSH moiety and immunoblotted with α-ENaC protein (Fig. 5A, middle). Herein, we show that the ∼65-kDa cleaved form of α-ENaC is primarily expressed in T2 cells, as opposed to the uncleaved full-length form (95 kDa) primarily expressed in cultured R3/1 rat alveolar epithelial cells using the same antibody targeting the COOH-terminal domain of α-ENaC subunit (Fig. 5A, left). We have recently characterized the binding specificity of the anti-α-ENaC antibody employed in Fig. 5. Based on this observation, we now conclude that the α-ENaC antibody directed against the COOH-terminal domain (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), primarily detects the active cleaved form of α-ENaC subunit in freshly isolated T2 cells. Figure 5B illustrates global glutathionylation of oxidation status of protein thiols performed in situ. In Fig. 5B, left and right, the blots were probed for streptavidin conjugation to total protein lysate that have indeed incorporated BioGEE. As a negative signal control, we show that the S-glutathionylated protein did not elute under nonreducing (−DTT) conditions. Figure 5B, right, shows that BioGEE incorporation into (total) protein could be eluted and easily detected in the presence of 10 mM DTT. All protein samples (regardless of vehicle, H2O2, or diamide treatment) had incorporated the biotinylated glutathione ethyl ester, as expected. Using a similar approach, we next showed that α-ENaC is indeed S-glutathionylated by probing the membrane with anti-α-ENaC antibody characterized in Fig. 5A. The amount of BioGEE incorporation with α-ENaC protein significantly increased under oxidizing conditions (H2O2 and diamide). Again, as expected, S-glutathionylated protein was only detectable after elution with 10 mM DTT (Fig. 5C, right lanes). Figure 5D represents averaged relative light units from four independently performed α-ENaC/BioGEE experiments.

Fig. 5.

α-ENaC is S-glutathionylated. A, left: control Western blot showing α-ENaC detection in R3/1 (full length) and T2 (cleaved) cells. IP, immunoprecipitated; IB, immunoblot. Middle: Western blot analysis of α-ENaC immunoprecipitated samples blotted with anti-GSH antibody indicates direct S-glutathionylation of α-ENaC subunit. Right: IgG signal control. B: control BioGEE assays conducted on equal number T2 cells under control, H2O2, or diamide treatments. Total cell lysate was run on a polyacrylamide gel under reducing (+DTT) and nonreducing (−DTT) conditions and labeled for biotin. Results are representative of 3 independent observations. C: T2 cells were incubated with H2O2 or diamide in the presence of BioGEE then lysed, ran on a gel, and immunoblotted for α-ENaC under reducing and nonreducing conditions. D: quantification of cleaved α-ENaC protein-SSG averaged from 3 independent observations.

DISCUSSION

Redox sensitive Cys.

Shifts in glutathione Eh of lung ELF to a more oxidized state are associated with aging, lung damage, and chronic disease states (29, 30, 32). The goal of the present study was to determine if altering glutathione redox potential affected ENaC activity and altered lung fluid clearance. Our findings are the first to demonstrate that shifting the redox potential to a more oxidized state by the addition of GSSG causes a decrease in ENaC activity, which can be rescued by the addition of GSH (Fig. 1). Moreover, we have found that direct, reversible modification of ENaC by GSSG (S-glutathionylation) is responsible for this change in ENaC activity. In these studies, reduced and oxidized glutathione was applied to the extracellular bath. The reagents are cell membrane impermeable; however, changes in extracellular oxidative state can impact intracellular redox status, as indicated by Fig. 4, which shows DHE labeling of cells following extracellular shifts in Eh. These findings provide novel insight into the role of redox regulation of lung fluid clearance in vivo. However, at this point, it remains unclear which Cys residue(s) (intracellular, transmembrane, or extracellular) is sensitive to positive shifts in Eh values away from baseline. Additional single channel recordings, in which GSH and GSSG were back-filled into the patch-clamp electrode supports the idea that extracellular Cys residues may be directly posttranslationally modified by S-glutathionylation. Specifically, 400 μM back-filled GSH increased ENaC Po (from 0.16 ± 0.06 to 0.32 ± 0.06; n = 8; P = 0.02) and 400 μM back-filled GSSG decreased ENaC Po (from 0.32 ± 0.08 to 0.17 ± 0.05; n = 10; P = 0.03) (data not shown). Together, these studies indicate that reversible S-glutathionylation of ENaC subunits can play an important role in regulating lung fluid balance.

The precise Cys thiol sensitive to S-glutathionylation has yet to be identified using a labor intensive mass spectrometry approach. We have circumvented the limitations of mass spectrometry analysis by using a bioinformatics method as an alternative way to predicting S-glutathionylation sites of α-, β-, and γ- ENaC subunits (Fig. 6). The Cys residues that may be sensitive to S-glutathionylation under oxidative stress were identified by employing machine learning methods based on protein sequence data. Using our bioinformatics method, we have obtained an area under curve score of 0.879 in fivefold cross validation, which demonstrates the predictive power of our proposed method.

Fig. 6.

Predicted ENaC subunit S-glutathionylation sites (shown in combination). α: 89C; 159C; 499C; 503C; 507C; 694C. β: 43C; 61C; 89C; 194C; 210C; 247C; 359C; 438C; 534C. γ: 100C; 551C.

Interestingly, all ENaC subunits express several highly conserved Cys on the extracellular loop (43). Because GSH is oxidized to GSSG within the cell and is then actively transported to the extracellular compartment (34, 44, 46), we hypothesize that extracellular α-ENaC Cys can be modified in this way (4). This is supported by our observation that application of GSSG via the recording electrode significantly altered ENaC Po. Alternatively, GSSG may be catabolized to GSH and thereby act as antioxidants and hinder intracellular ROS modification of α-ENaC activity. The direct mechanism of posttranslational modification following change to intracellular and extracellular redox states is currently unknown.

Physiological relevance of ion channel glutathionylation.

Posttranslational modifications of ion channels are becoming increasingly recognized as important regulatory mechanism of ion channel activity (51). S-glutathionylation, which occurs during oxidative stress, allows channel activity to be directly modified in response to environmental conditions. In the present study, we present biochemical data that suggest that α-ENaC subunit undergoes S-glutathionylation when the glutathione redox potential is shifted to a more oxidized potential (Fig. 5, A and B). Furthermore, biotinylated glutathione uptake was increased in T2 cells exposed to H2O2 or when GSH was converted to GSSG by diamide but blocked when Cys residues were modified by NEM (Fig. 5C). Additionally, electrophysiological data showed that modification of Cys residues with NEM blocked the decrease in ENaC Po when channels were directly exposed to GSSG in the recording electrode (Fig. 2, C and D). Taken together, these experiments provide evidence that ENaC activity is modified in response to oxidative stress via S-glutathionylation of the α-ENaC subunit.

Data from other groups have suggested that S-glutathionylation of ENaC may be an important posttranslational modification to regulate function and ultimately lung fluid balance, but evidence has been lacking. Nitric oxide, which can oxidize GSH leading to increased concentrations of GSSG, is increased in models of pulmonary edema (19, 23, 28, 45). Studies also suggest that nitric oxide may impair glutathione reductase activity, effectively reducing the rate of GSSG conversion to GSH (5). There are, however, therapeutic benefits to inhibiting ENaC. Investigators are currently developing novel compound inhibitors of ENaC to help rehydrate cigarette smoke-exposed airways and thereby restore mucociliary clearance (3). It is an intriguing possibility that manipulating the redox potential (alongside the use of other conventional inhibitors of ENaC, such as amiloride and benzamil) could rescue the dehydrated airways of patients with pulmonary disorders.

In the present study, we increased levels of oxidized GSH by adding GSSG to alter the Eh to determine the effect of “redox” state on lung ENaC activity and, ultimately, alveolar fluid clearance. Our group has previously shown that the application of exogenous H2O2 increases ENaC activity (14), and in the current study we show that shifting the GSH/GSSG Eh towards less negative values via increasing GSSG concentrations caused a significant decrease in ENaC activity. This observed effect of GSSG on net salt and water movement across epithelial cells was consistent whether GSSG was exogenously applied (Figs. 1 and 2) or tracheally instilled in vivo (Fig. 3). The opposing effects of H2O2 and GSSG application suggest that the result of oxidizing the redox potential is not simply elevation of intracellular ROS, but two separate mechanisms acting upon the cell. H2O2 has been shown to increase ENaC activity by increasing phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3] in the apical membrane by stimulating phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (35), while S-glutathionylation occurs via thiol modification of Cys residues.

Our observations are in line with the general paradigm that S-glutathionylation is a primary response to oxidative stress, which can also occur under basal conditions (10, 38, 48). Previous studies have suggested that S-glutathionylation occurs during oxidative stress to protect Cys residues against irreversible oxidation and can be reversed when environmental conditions permit (10). Additionally, ENaC subunit expression is repressed by oxidative stress (50), which also serves to counteract ROS-mediated increases in channel activity. The present study suggests that an additional role of S-glutathionylation may serve to protect the lung against ROS-mediated excess fluid clearance, leading to drying of the lung, thus indicating the important role of the GSH Eh in ENaC regulation.

Redox signaling in T1 and T2 cells.

In the current study, we assessed the effect of shifting the extracellular Eh on ROS production. We assessed H2O2 levels in the cell supernatant and DHE-labeled lung tissue slices (Fig. 4). In both instances, shifting the extracellular Eh to more positive values resulted in a net increase in ROS detection. This suggests that the extracellular redox state of the epithelial lining fluid may play a critical role in cell signaling, ENaC activity, and thus, the maintenance of lung fluid balance. Because our group is able to access T1 and T2 cells from live lung tissue, as well as isolate pure populations of T2 cells, we can make novel comparisons between all the cells that make up the alveolar wall. We have previously shown that exogenous H2O2 increases ENaC activity (14, 35). We have also observed that the effect of H2O2 on ENaC activity is more robust in T2 cells compared with T1 cells. This difference in T1 and T2 response to H2O2 can, in part, be explained by our previous observation that T1 cells produce larger amounts of ROS (20) and have lower levels of glutathione peroxidase (1, 11) compared with T2 cells. As such, T2 cells may be generating more (inhibitory) GSSG in response to exogenous H2O2. It is an intriguing possibility that T1 and T2 cells have different sensitivities to oxidative stress. At the least, these findings highlight the need for additional redox studies on the regulatory mechanisms of lung ENaC.

Conclusions.

In summary, single channel patch-clamp analysis of primary isolated and lung tissue preparations allow us to access and determine the effect of oxidants, antioxidants, and adducts formed on ENaC expressed in T1 and T2 cells. It is important to examine the effect of both neighboring cell types under various redox potentials, given that both cell types contribute to net salt and water transport out of the lungs. Moreover, our in vivo assessment of lung fluid clearance correlates with the observed increase in ENaC activity following GSH treatment and significant decrease in ENaC activity following GSSG application. Whether pro- and antioxidants can be effectively utilized to treat edematous lung injury in adult and newborn lung remains an area of active investigation.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: C.A.D., L.K., P.T.T., and N.M.J. performed experiments; C.A.D., X.-M.Z., J.M.H., and M.N.H. analyzed data; C.A.D., X.-M.Z., J.M.H., L.A.S.B., and M.N.H. interpreted results of experiments; C.A.D., L.K., P.T.T., N.M.J., and M.N.H. prepared figures; C.A.D., L.K., and M.N.H. drafted manuscript; C.A.D. and M.N.H. edited and revised manuscript; C.A.D., L.K., X.-M.Z., P.T.T., N.M.J., J.M.H., L.A.S.B., and M.N.H. approved final version of manuscript; L.A.S.B. and M.N.H. conception and design of research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asayama K, Yokota S, Dobashi K, Kawada Y, Nakane T, Kawaoi A, Nakazawa S. Immunolocalization of cellular glutathione peroxidase in adult rat lungs and quantitative analysis after postembedding immunogold labeling. Histochem Cell Biol 105: 383–389, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashfaq S, Abramson JL, Jones DP, Rhodes SD, Weintraub WS, Hooper WC, Vaccarino V, Harrison DG, Quyyumi AA. The relationship between plasma levels of oxidized and reduced thiols and early atherosclerosis in healthy adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 47: 1005–1011, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Astrand AB, Hemmerling M, Root J, Wingren C, Pesic J, Johansson E, Garland AL, Ghosh A, Tarran R. Linking increased airway hydration, ciliary beating, and mucociliary clearance through ENaC inhibition. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308: L22–L32, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bao HF, Zhang ZR, Liang YY, Ma JJ, Eaton DC, Ma HP. Ceramide mediates inhibition of the renal epithelial sodium channel by tumor necrosis factor-alpha through protein kinase C. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1178–F1186, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beigi F, Gonzalez DR, Minhas KM, Sun QA, Foster MW, Khan SA, Treuer AV, Dulce RA, Harrison RW, Saraiva RM, Premer C, Schulman IH, Stamler JS, Hare JM. Dynamic denitrosylation via S-nitrosoglutathione reductase regulates cardiovascular function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 4314–4319, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown LA, Ping XD, Harris FL, Gauthier TW. Glutathione availability modulates alveolar macrophage function in the chronic ethanol-fed rat. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L824–L832, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calabrese V, Sultana R, Scapagnini G, Guagliano E, Sapienza M, Bella R, Kanski J, Pennisi G, Mancuso C, Stella AM, Butterfield DA. Nitrosative stress, cellular stress response, and thiol homeostasis in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 8: 1975–1986, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canessa CM, Schild L, Buell G, Thorens B, Gautschi I, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC. Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel is made of three homologous subunits. Nature 367: 463–467, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantin AM, North SL, Hubbard RC, Crystal RG. Normal alveolar epithelial lining fluid contains high levels of glutathione. J Appl Physiol 63: 152–157, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalle-Donne I, Milzani A, Gagliano N, Colombo R, Giustarini D, Rossi R. Molecular mechanisms and potential clinical significance of S-glutathionylation. Antioxid Redox Signal 10: 445–473, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinsdale D, Green JA, Manson MM, Lee MJ. The ultrastructural immunolocalization of gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase in rat lung: correlation with the histochemical demonstration of enzyme activity. Histochem J 24: 144–152, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downs CA, Kreiner LH, Trac DQ, Helms MN. Acute effects of cigarette smoke extract on alveolar epithelial sodium channel activity and lung fluid clearance. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 49: 251–259, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downs CA, Kriener LH, Yu L, Eaton DC, Jain L, Helms MN. β-Adrenergic agonists differentially regulate highly selective and nonselective epithelial sodium channels to promote alveolar fluid clearance in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 302: L1167–L1178, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downs CA, Kumar A, Kreiner LH, Johnson NM, Helms MN. H2O2 regulates lung epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) via ubiquitin-like protein Nedd8. J Biol Chem 288: 8136–8145, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Downs CA, Trac D, Brewer EM, Brown LA, Helms MN. Chronic alcohol ingestion changes the landscape of the alveolar epithelium. Biomed Res Int 2013: 470217, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downs CA, Trac DQ, Kreiner LH, Eaton AF, Johnson NM, Brown LA, Helms MN. Ethanol alters alveolar fluid balance via Nadph oxidase (NOX) signaling to epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) in the lung. PLoS One 8: e54750, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodson P, Kumar A, Jain L, Kundu K, Murthy N, Koval M, Helms MN. Nadph oxidase regulates alveolar epithelial sodium channel activity and lung fluid balance in vivo via O2− signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 302: L410–L419, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gui L, Qian H, Rocco KA, Grecu L, Niklason LE. Efficient intratracheal delivery of airway epithelial cells in mice and pigs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308: L221–L228, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo Y, Duvall MD, Crow JP, Matalon S. Nitric oxide inhibits Na+ absorption across cultured alveolar type II monolayers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 274: L369–L377, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helms MN, Jain L, Self JL, Eaton DC. Redox regulation of epithelial sodium channels examined in alveolar type 1 and 2 cells patch-clamped in lung slice tissue. J Biol Chem 283: 22875–28883, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helms MN, Self J, Bao HF, Job LC, Jain L, Eaton DC. Dopamine activates amiloride-sensitive sodium channels in alveolar type I cells in lung slice preparations. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L610–L618, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hummler E, Barker P, Gatzy J, Beermann F, Verdumo C, Schmidt A, Boucher R, Rossier BC. Early death due to defective neonatal lung liquid clearance in alpha-ENaC-deficient mice. Nat Genet 12: 325–328, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iles KE, Song W, Miller DW, Dickinson DA, Matalon S. Reactive species and pulmonary edema. Expert Rev Respir Med 3: 487–496, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ismailov II, Awayda MS, Berdiev BK, Bubien JK, Lucas JE, Fuller CM, Benos DJ. Triple-barrel organization of ENaC, a cloned epithelial Na+ channel. J Biol Chem 271: 807–816, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain L, Chen XJ, Malik B, Al-Khalili O, Eaton DC. Antisense oligonucleotides against the a-subunit of ENaC decrease lung epithelial cation-channel activity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 276: L1046–L1051, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain L, Chen XJ, Ramosevac S, Brown LA, Eaton DC. Expression of highly selective sodium channels in alveolar type II cells is determined by culture conditions. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L646–L658, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang C, Finkbeiner WE, Widdicombe JH, McCray PB Jr, Miller SS. Altered fluid transport across airway epithelium in cystic fibrosis. Science 262: 424–427, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jilling T, Haddad IY, Cheng SH, Matalon S. Nitric oxide inhibits heterologous CFTR expression in polarized epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 277: L89–L96, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones DP. Redefining oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal 8: 1865–1879, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones DP. The health dividend of glutathione. Nat Med J 3: 2, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones DP, Carlson JL, Mody VC, Cai J, Lynn MJ, Sternberg P. Redox state of glutathione in human plasma. Free Radic Biol Med 28: 625–635, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones DP, Carlson JL, Samiec PS, Sternberg P Jr, Mody VC Jr, Reed RL, Brown LA. Glutathione measurement in human plasma Evaluation of sample collection, storage and derivatization conditions for analysis of dansyl derivatives by HPLC. Clin Chim Acta 275: 175–184, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones DP. Redox Potential of GSH/GSSG Couple: Assay and Biological Significance, edited by Helmut S, Lester P. New York: Academic, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirsch JD, Yi AK, Spitz DR, Krieg AM. Accumulation of glutathione disulfide mediates NF-kappaB activation during immune stimulation with CpG DNA. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev 12: 327–340, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma HP. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates the epithelial sodium channel through a phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 286: 32444–32453, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mall M, Grubb BR, Harkema JR, O'Neal WK, Boucher RC. Increased airway epithelial Na+ absorption produces cystic fibrosis-like lung disease in mice. Nat Med 10: 487–493, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matthay MA, Wiener-Kronish JP. Intact epithelial barrier function is critical for the resolution of alveolar edema in humans. Am Rev Respir Dis 142: 1250–1257, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mieyal JJ, Gallogly MM, Qanungo S, Sabens EA, Shelton MD. Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications of reversible protein S-glutathionylation. Antioxid Redox Signal 10: 1941–1988, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myerburg MM, Butterworth MB, McKenna EE, Peters KW, Frizzell RA, Kleyman TR, Pilewski JM. Airway surface liquid volume regulates ENaC by altering the serine protease-protease inhibitor balance: a mechanism for sodium hyperabsorption in cystic fibrosis. J Biol Chem 281: 27942–27949, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olivier R, Scherrer U, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC, Hummler E. Selected contribution: limiting Na+ transport rate in airway epithelia from alpha-ENaC transgenic mice: a model for pulmonary edema. J Appl Physiol 93: 1881–1887, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roum JH, Buhl R, McElvaney NG, Borok Z, Crystal RG. Systemic deficiency of glutathione in cystic fibrosis. J Appl Physiol 75: 2419–2424, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samiec PS, Drews-Botsch C, Flagg EW, Kurtz JC, Sternberg P Jr, Reed RL, Jones DP. Glutathione in human plasma: decline in association with aging, age-related macular degeneration, and diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med 24: 699–704, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheng S, Maarouf AB, Bruns JB, Hughey RP, Kleyman TR. Functional role of extracellular loop cysteine residues of the epithelial Na+ channel in Na+ self-inhibition. J Biol Chem 282: 20180–20190, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh S, Khan AR, Gupta AK. Role of glutathione in cancer pathophysiology and therapeutic interventions. J Exp Ther Oncol 9: 303–316, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song W, Matalon S. Modulation of alveolar fluid clearance by reactive oxygen-nitrogen intermediates. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L855–L858, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Srivastava SK, Beutler E. The transport of oxidized glutathione from human erythrocytes. J Biol Chem 244: 9–16, 1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sullivan DM, Levine RL, Finkel T. Detection and affinity purification of oxidant-sensitive proteins using biotinylated glutathione ethyl ester. Methods Enzymol 353: 101–113, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Townsend DM. S-glutathionylation: indicator of cell stress and regulator of the unfolded protein response. Mol Interv 7: 313–324, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watson WH, Pohl J, Montfort WR, Stuchlik O, Reed MS, Powis G, Jones DP. Redox potential of human thioredoxin 1 and identification of a second dithiol/disulfide motif. J Biol Chem 278: 33408–33415, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu H, Chu S. ENaC alpha-subunit variants are expressed in lung epithelial cells and are suppressed by oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L1454–L1462, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Y, Jin X, Jiang C. S-glutathionylation of ion channels: insights into the regulation of channel functions, thiol modification crosstalk, and mechanosensing. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 937–951, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yeh MY, Burnham EL, Moss M, Brown LA. Chronic alcoholism alters systemic and pulmonary glutathione redox status. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 270–276, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu L, Bao HF, Self JL, Eaton DC, Helms MN. Aldosterone-induced increases in superoxide production counters nitric oxide inhibition of epithelial Na channel activity in A6 distal nephron cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1666–F1677, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]