Abstract

Thiamin is essential for normal metabolism in pancreatic acinar cells (PAC) and is obtained from their microenvironment through specific plasma-membrane transporters, converted to thiamin pyrophosphate (TPP) in the cytoplasm, followed by uptake of TPP by mitochondria through the mitochondrial TPP (MTPP) transporter (MTPPT; product of SLC25A19 gene). TPP is essential for normal mitochondrial function. We examined the effect of long-term/chronic exposure of PAC in vitro (pancreatic acinar 266-6 cells) and in vivo (wild-type or transgenic mice carrying the SLC25A19 promoter) of the cigarette smoke toxin, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), on the MTPP uptake process. Our in vitro and in vivo findings demonstrate that NNK negatively affects MTPP uptake and reduced expression of MTPPT protein, MTPPT mRNA, and heterogenous nuclear RNA, as well as SLC25A19 promoter activity. The effect of NNK on Slc25a19 transcription was neither mediated by changes in expression of transcriptional factor NFY-1 (known to drive SLC25A19 transcription), nor due to changes in methylation profile of the Slc25a19 promoter. Rather, it appears to be due to changes in histone modifications that involve significant decreases in histone H3K4-trimethylation and H3K9-acetylation (activation markers). The effect of NNK on MTPPT function is mediated through the nonneuronal α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7-nAChR), as indicated by both in vitro (using the nAChR antagonist mecamylamine) and in vivo (using an α7-nAchR−/− mouse model) studies. These findings demonstrate that chronic exposure of PAC to NNK negatively impacts PAC MTPP uptake. This effect appears to be exerted at the level of Slc25a19 transcription, involve epigenetic mechanism(s), and is mediated through the α7-nAchR.

Keywords: mitochondrial thiamin pyrophosphate transport, pancreatic acinar cells, cigarette smoke, NNK

thiamin pyrophosphate (TPP) is a diphosphorylated form of the B-vitamin, thiamin, and is an essential cofactor for a range of enzymes involved in oxidative energy metabolism, including cytosolic transketolase, mitochondrial α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), and branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase (7). Thiamin insufficiency has been shown to adversely affect normal structure and function of the mitochondria (8), an organelle that stores ∼90% of cellular TPP content. Cellular thiamin deficiency leads to reduced mitochondrial energy production, leaving cells vulnerable to oxidative stress (13).

The pancreas typically maintains high thiamin levels for use in critical exocrine and endocrine functions. Therefore, reductions in its availability can negatively affect pancreatic endocrine cell function (39, 40). Pancreatic acinar cells (PAC) are unable to synthesize thiamin and must obtain it from the circulation using a carrier-mediated process involving the high-affinity plasma membrane thiamin transporters-1 and -2 (THTR-1 and THTR-2; proteins encoded by the SLC19A2 and SLC19A3 genes) (50). Internalized free thiamin is then enzymatically converted to TPP exclusively in the cytoplasm (16, 20); subsequently, up to 90% of the TPP moves into the mitochondria through a mitochondrial membrane carrier-mediated process that involves the mitochondrial TPP (MTPP) transporter (MTPPT) system, product of the SLC25A19 gene (25, 33).

A range of environmental factors, such as chronic abuse of alcohol and tobacco, are known to negatively impact pancreatic physiology and function. Furthermore, numerous reports show that cigarette smoking (CS) is an independent and dose-dependent risk factor for the development and advancement of pancreatic diseases, such as pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer (3, 28, 35). CS significantly alters normal exocrine function, inducing pathological changes detrimental to pancreatic health (2, 5, 54). The underlying cellular mechanism(s) that mediate the effects of chronic cigarette smoke exposure are not fully understood, but are thought to include alterations in gene expression [with both inhibition and induction being reported (21, 49, 55, 56)], oxidative stress (24), and mitochondrial dysfunction (12). Although several thousand compounds are present in CS, nicotine and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) have been the most widely implicated constituents with respect to pancreatic disease (53). The nitrosylated nicotine metabolite, NNK, is highly toxic and has been shown to accumulate in organs, including the pancreas, following smoking (38). We have shown that NNK exposure negatively affects cellular thiamin uptake. This effect is mediated at the level of transcription of both the thiamin transporter genes SLC19A2 and SLC19A3 (47). Here we examined the effect of long-term/chronic exposure of PAC to NNK both in vitro (mouse-derived pancreatic acinar 266-6 cells) and in vivo [wild-type (C57BL/6) mice and transgenic mice that carry the human SLC25A19 promoter] on MTPP uptake. The findings show that chronic exposure of PAC to NNK inhibits TPP uptake, and that this effect occurs partly at the level of Slc25a19 transcription and apparently involves histone modifications at the Slc25a19 promoter. Also, since nonneural nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) have previously been shown to mediate NNK-induced pancreatitis responses in rats (2), we also explored whether the NNK effect on MTPP transport is mediated through a nonneuronal α7-nAChR-mediated pathway. For that, we pretreated PAC in vitro (mouse-derived pancreatic acinar 266-6 cells) with the nAChR blocker mecamylamine and then exposed them to NNK; alternatively, we treated α7-nAchR−/− mice with NNK. In both of these in vitro and in vivo studies, NNK effects on MTPP transport were abrogated, suggesting that nonneuronal α7-nAChR-mediated pathways might also be involved.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

[3H]TPP (specific activity 1.8 Ci/mmol; radiochemical purity > 97%) was obtained from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, CA). Nylon filters (0.45-μm pore size) were from Millipore (Fisher Scientific). Unlabeled TPP and other chemicals, including molecular biology reagents, were from commercial vendors and were of analytic grade. Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by Sigma Genosys (Sigma, Woodland, TX). MTPPT goat polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and PDH E1 α-subunit monoclonal antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA).

Methods

Chronic/long-term exposure of 266-6 cells to NNK and MTPP uptake.

The mouse-derived pancreatic acinar 266-6 cells were from American Type Tissue Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD) and were cultured in DMEM growth medium containing 10% FBS and an antibiotic cocktail. Cells between passages 2 and 20 were exposed to 3 μM NNK [a concentration that mimics the level of NNK found in human pancreatic juice of smokers (38)] for 24 h in DMEM growth medium containing 5% FBS, as described before (32). Mitochondria was isolated form 266-6 cells using Mitochondria Isolation Kit for Cultured Cells (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) following the manufacturer's instruction. The final mitochondrial pellet was suspended in uptake buffer [in mM: 140 KCl, 0.3 EDTA, 5 MgCl2, 10 MES, 10 HEPES, succinate (to maintain mitochondrial function), pH 7.4], to achieve a protein concentration of ∼15–20 μg/μl and then immediately used for uptake studies. Twenty microliters of mitochondria suspension were added to 80 μl of uptake buffer containing [3H]TPP (0.38 μM) and then subjected to the incubation at 37°C for 5 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 1 ml of ice-cold stop solution [in mM: 100 KCl, 100 mannitol, and 10 KH2PO4, pH 7.4] followed by rapid filtration. The filter was washed two times with stop solution followed by measurement of radioactivity in a liquid scintillation counter. An aliquot of the mitochondrial suspension was used for protein estimation.

Chronic exposure of mice to NNK and MTPP uptake studies.

Wild-type (C57 BL6) mice, transgenic mice carrying the full-length human SLC25A19 promoters fused to firefly luciferase reporter gene (previously generated and characterized by us; Ref. 46), and α7-nAChR−/− mice (kindly provided by M. Picciotto, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT) were used in these studies. Animal use was approved by the Internal Animal Care and Use Committee of the Veterans Affairs at Long Beach, CA and West Haven, CT. NNK (10 mg/100 g body wt) was administered intraperitoneal as described recently (2, 47) thrice/week for 2 wk; control mice were injected with normal saline only. This method delivers NNK at a dosage similar to the level of NNK found in smokers (2). After 2 wk of chronic NNK exposure, mice were euthanized, the pancreas was removed, and primary PAC were isolated from mice by a collagenase type V (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) digestion method, as described previously (41). Mitochondria was isolated from 200 mg of primary PAC using Mitochondria Isolation Kit for tissues (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) following the manufacturer's instruction. The final mitochondrial pellet was suspended in uptake buffer, and MTPP uptake was performed as described above using a rapid filtration method. Measurement of radioactivity and protein determination were done as described above.

Western blot and quantitative PCR analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed using whole cell lysate prepared from 266-6 cells and mouse primary PAC exposed to NNK and their respective controls, as described previously (45, 47, 48). Sixty micrograms of protein resolved in 10% Bis-Tris minigel (Invitrogen) was electroblotted onto immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Fisher Scientific) and blocked with Odyssey blocking solution (LI-COR Bioscience, Lincoln, NE) for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation with primary antibody of MTPPT (1:100 dilution) goat polyclonal antibody, along with PDH E1 α-subunit (1:10,000 dilution) monoclonal antibody. The MTPPT and PDH immunoreactive bands were detected by using donkey anti-goat IRDye-800 for MTPPT and goat anti-mouse IRDye 680 secondary antibodies (1:30,000 dilution). Signals were detected with the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Bioscience) and quantified with LI-COR software and normalized to PDH as an internal control.

cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of RNA isolated from 266-6 cells and primary mouse PAC that was digested with DNase I (Invitrogen) reverse transcribed using iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The mice Slc25a19 and ARPO gene were amplified using gene-specific primers for mRNA/heterogenous nuclear RNA (hnRNA) (Table 1) for quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis using conditions described previously (46). The ARPO was used as endogenous control, and the data were quantified using relative relationship method (34).

Table 1.

Primers used for qPCR, cloning of mouse Slc25a19 promoter, bisulfite PCR primers for amplifying mice Slc25a19 CpG islands, and qPCR primers for histone modification studies

| Primers Used in the Study: Forward and Reverse Primers (5′-3′) |

|---|

| Primers for real-time PCR |

| ARPO mRNA: GCTGAACATCTCCCCCTTCTC; ATATCCTCATCTGATTCCTCC |

| Slc25a19 mRNA: TCCAGATTGAACGCCTGTG; GACAGCTCCGTAGCCTATGGAC |

| ARPO hnRNA: GGCATCTTCAGTTGTTCC; TTAGACACAGCCCCCAC |

| Slc25a19 hnRNA: CTGCTGTGGTCTTCTGTAG; ATCTTCTTGCTTTTGTCTTC |

| Primers for Slc25a19 promoter bisulfite PCR analysis |

| TTAATGAGAGGTTTTTTAGAAGGT; ATAACCCAACAACAAAACTTAACAAC |

| Primers for histone modification studies of the Slc25a19 promoter |

| −266 to −137: GCGGTATCTGGACAGTGACA; TGTAGCCCAACAGCAAAACTT |

| −131 to +10: TAAAAGCCAACTTCGCCATC; CTGTAGTCTTCCGCTTCCAA |

| Primers for PCR amplification of β1-AR, β2-AR, and α7-nAChR |

| β1-AR: CATCGTAGTGGGCAACGTGTTG; AAATCGCAGCACTTGGGGTC |

| β2-AR: ACCTCCTTCTTGCCTATCCA; TAGGTTTTCGAAGAAGACCG |

| α7-nAChR: ATCTGGGCATTGCCAGTATC; TCCCATGAGATCCCATTCTC |

Luciferase reporter gene assay.

The SLC25A19 full-length promoter-luciferase reporter construct utilized in this study was generated previously (37). The 266-6 cells were co-transfected with 2 μg of SLC25A19-luciferase plasmid and 100 ng of pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase-thymidine kinase control plasmid) (Promega, Madison, WI) using lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. One day after transfection, the cells were exposed to NNK (3 μM) for 24 h, as described above. After 24 h of NNK exposure, Renilla-normalized firefly luciferase activity was determined by using the Dual Luciferase Assay system (Promega).

For measuring the firefly luciferase activity in transgenic mice PAC, the isolated PAC were homogenized in ice-cold passive lysis buffer (Promega), and firefly luciferase activity was determined using a Luciferase Assay system (Promega). Luciferase activity was normalized to total protein concentration in each sample.

DNA methylation analysis.

Genomic DNA was isolated using Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega) from NNK-exposed 266-6 cells and mice primary PAC, and bisulfite conversion was performed using the EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen), which results in the conversion of all the unmethylated cytosines, except the 5-methylcytosines to uracil. The bisulfite converted DNA was PCR amplified using primers designed by MethPrimer (31), which span areas of CpG islands in the promoter of Slc25a19, as described earlier (46). The PCR amplicons obtained were cloned in pGEM-T easy vector (Promega) and were sequenced using either the T-7 or the Sp-6 primers from a commercial vendor (Laragen). The sequence was analyzed using QUMA methylation analysis tool (27). A minimum of 10 clones were analyzed per sample of control and NNK, and data are from 3 independent experiments.

Histone modifications.

The DNA for ChIP-qPCR was obtained using SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (agarose beads) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) following manufacturer's recommendation. The 266-6 cells exposed to NNK and their controls were cross-linked using 1% formaldehyde for 10 min and followed by addition of 0.1 volume glycine to stop the cross-linking. Nuclei obtained using the manufacturer's protocol was digested with micrococcal nuclease followed by sonication. Fifty microliters of the sonicated chromatin preparation were purified using DNA spin columns provided with the kit and checked for chromatin digestion and concentration. Five micrograms of chromatin were diluted in 500 μl ChIP buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail, and 10 μl of this sample were stored to be used as 2% input in qPCR. This chromatin preparation was immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C using specific antibodies for H3, H3K4me3, H3K9Ac, and IgG (IgG was used as negative control). DNA from immunoprecipitated samples and the 2% input were purified following the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was performed using purified DNA obtain from NNK-exposed and control 266-6 cells and primers that span −266 to −137 and −131 to +10 [transcription start site (TSS) = +1] (see Table 1) region of the mouse Slc25a19 promoter (Table 1), as described earlier (46). The data were normalized to percent input and expressed as percentage of H3 enrichment relative to the control. No amplification was detected in IgG negative control.

Statistical Analysis

Uptake data (determined by subtracting simple diffusion from total uptake) with isolated mitochondria form 266-6 cells, and mouse primary PAC are means ± SE of a minimum of three independent experiments and are expressed as percentage relative to simultaneously performed controls. Western blot analysis, qPCR, promoter-luciferase activity, and histone modification studies were all performed from triplicates of samples prepared at different occasions. The Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effect of Exposure of PACs to NNK on Physiological and Molecular Parameters of MTPP Uptake: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies

In vitro exposure studies.

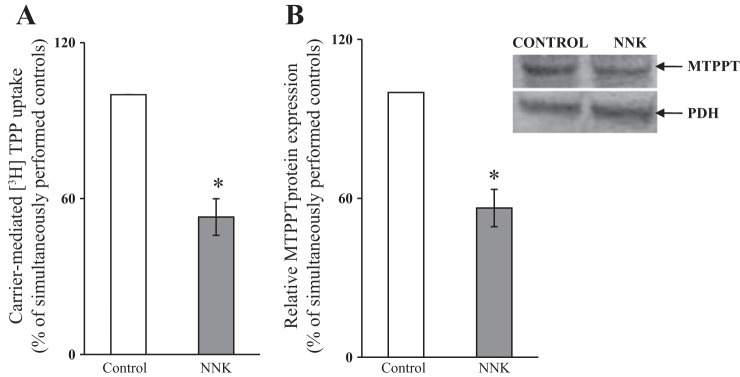

Using the mouse-derived pancreatic acinar 266-6 cells as a model, we determined the effect of chronic/long-term NNK treatment on carrier-mediated TPP uptake by freshly isolated mitochondria from NNK-exposed cells and their control; treatment with NNK (3 μM, 24 h) was done as described (32). The results showed a significant (P < 0.05) inhibition in MTPP uptake by NNK-exposed cells compared with control (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Chronic/long-term exposure of pancreatic acinar 266-6 cells to NNK inhibits mitochondrial [3H]TPP uptake (A) and decreases the level of expression of MTPPT protein (B). Cells were exposed to NNK (3 μM, 24 h), and carrier-mediated [3H]TPP uptake was determined in freshly isolated mitochondria. Level of protein expression was determined by Western blotting. Values are means ± SE of at least 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.01.

Thiamin availability is known to affect energy metabolism in cells (58). Therefore, we examined the effect of chronic exposure of 266-6 cells to NNK on the total cellular ATP content. The results showed a significant (P < 0.05) reduction in total cellular ATP level in cells exposed to NNK compared with unexposed controls (100 ± 4 vs. 63 ± 13% of total cellular content ATP from simultaneously performed studies for control and NNK exposure, respectively).

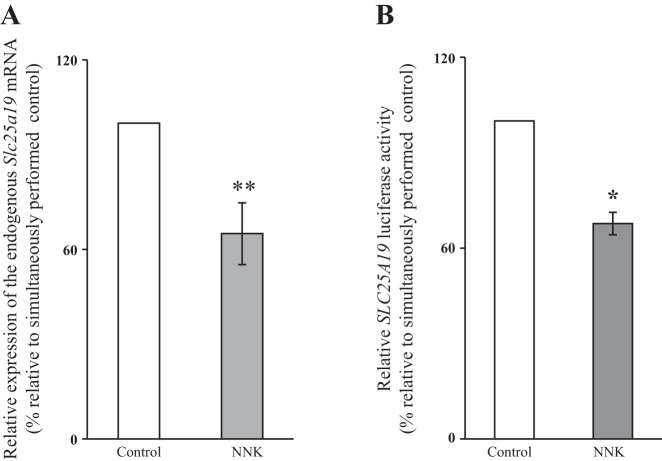

The effect of NNK exposure on cellular levels of the MTPPT protein was assessed with immunoblotting using specific polyclonal antibodies against the transporter (see materials and methods). The results showed a significant (P < 0.01) reduction in the level of expression of MTPPT protein in cells chronically exposed to NNK compared with controls (Fig. 1B). In another study, we tested the effect of chronic exposure of 266-6 cells to NNK on the level of expression of mouse Slc25a19 mRNA by qPCR. The results showed a significant (P < 0.05) reduction in the level of expression of Slc25a19 mRNA in cells exposed to NNK compared with controls (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Chronic/long-term exposure of pancreatic acinar 266-6 cells to NNK inhibits expression of Slc25a19 mRNA (A) and activity of the SLC25A19 promoter (B). RNA was isolated from cells chronically exposed to NKK (3 μM, 24 h). Mouse endogenous Slc25a19 mRNA was quantitated using qPCR. Full-length SLC25A19 promoter in pGL3-basic was transfected into 266-6 cells and were exposed to NNK, followed by determination of luciferase activity. Values were normalized relative to Renilla luciferase activity are expressed as the means ± SE of at least 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.01. **P < 0.05.

Although changes in mRNA level could occur through several processes, a common mechanism is through changes in gene transcription. We tested the effect of prolonged exposure of 266-6 cells to NNK on the activity of the human SLC25A19 promoter transfected into these cells and found a significant (P < 0.01) reduction in the activity of SLC25A19 promoter after NNK exposure (Fig. 2B). Collectively, the above findings indicate that extended treatment of PAC with NNK inhibits MTPP uptake, and that the effect is partially explained by a decrease in level of transcription of the SLC25A19 gene and its protein product, MTPPT.

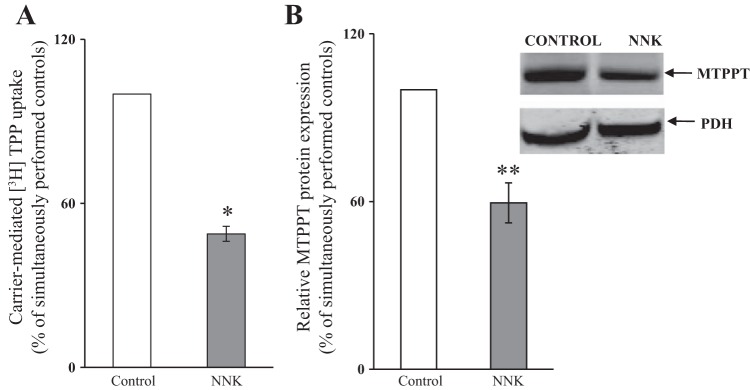

In vivo exposure studies.

To validate our in vitro findings, we assessed the effect of chronic exposure to NNK on pancreatic acinar MTPP uptake in wild-type mice. Treatments (intraperitoneal injection, 10 mg/100 g body wt, three times per week for 2 wk) were carried out as described (2, 47), and MTPP uptake was examined using freshly isolated mitochondria from the PAC, as described in materials and methods. The results showed a significant (P < 0.01) inhibition in MTPP uptake by freshly isolated mitochondria from PAC of NNK-treated mice compared with those isolated from control animals (Fig. 3A). Chronic NNK exposure of mice caused a significant (P < 0.05) decrease in MTPPT protein in PAC compared with controls (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Chronic exposure of wild-type (C57BL/6) mice to NNK inhibits mitochondrial [3H]TPP uptake (A) and decreases the level of expression of MTPPT protein (B) in PAC. Wild-type (C57BL/6) mice were exposed to NNK (10 mg/100 g body wt) for 2 wk, and the controls were injected with saline. Carrier-mediated mitochondrial [3H]TPP uptake was determined in freshly isolated mitochondria from PAC, and the level of protein expression was determined by Western blotting using total cell lysate isolated from PAC of NNK-exposed mice and their controls. *P < 0.01. **P < 0.05.

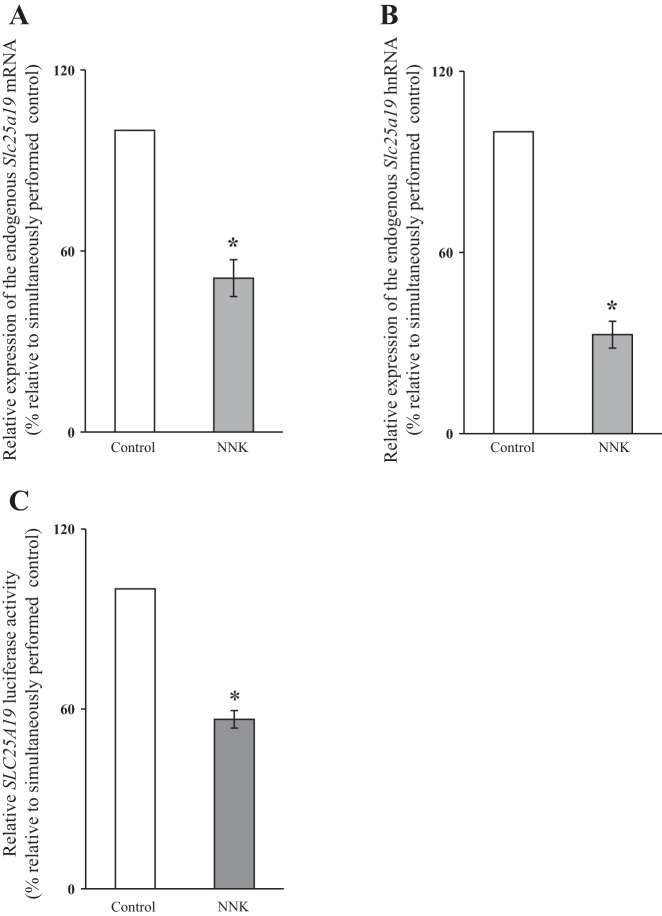

In another study, we examined the effect of chronic exposure of mice to NNK on endogenous mRNA levels of Slc25a19 mRNA and hnRNA (level of hnRNA of a particular gene reflects the rate of transcription of that gene). For this, we used transgenic mice carrying the human SLC25A19 promoter (fused to the firefly luciferase reporter gene) (46) to allow for simultaneous and direct examination of the effect of in vivo exposure to NNK on promoter activity. The results showed a significant (P < 0.01) reduction in the expression of the Slc25a19 mRNA in PAC of mice chronically treated with NNK compared with the controls (Fig. 4A). Similarly, a significantly (P < 0.01) lower level of expression of the Slc25a19 hnRNA was found in mice chronically exposed to NNK compared with controls (Fig. 4B). The latter suggests the possible involvement of a transcriptional mechanism(s) in the observed inhibitory effects of NNK on PAC MTPP uptake. This was confirmed by the finding that activity of the SLC25A19 promoter in PAC of the NNK-treated mice is significantly (P < 0.01) lower than that of controls (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Chronic exposure of transgenic mice carrying the SLC25A19 promoter to NNK inhibits Slc25a19 mRNA (A) and hnRNA (B) expression, as well as activity of the human SLC25A19 promoter (C) in PAC. RNA was isolated from PAC of transgenic mice exposed to NNK (10 mg/100 g body wt; Ref. 26) for 2 wk and their controls. Mouse endogenous Slc25a19 mRNA and hnRNA were quantitated using qPCR. Luciferase activity of SLC25A19 promoters was determined in lysates prepared from the PAC of mice and is presented as percentage relative to controls. Values are means ± SE of at least 3 independent experiments from multiple sets of mice. *P < 0.01.

Mechanism(s) Involved in the Inhibitory Effects of Chronic NNK Exposure of PAC on Slc25a19 Promoter Activity

The above-described studies showed that in vitro and in vivo exposure of PAC to NNK leads to an inhibition in MTPP uptake, and that this inhibition is, at least in part, mediated by decreased transcription of the Slc25a19 gene. Since this effect could be mediated by changes in expression of a nuclear factor(s) that is needed for activity of the Slc25a19 promoter or through epigenetic mechanisms (e.g., DNA methylation, histone modifications, or both), we examined both possibilities. We focused on the role of the transcription factor NF-Y, since our laboratory's recent research has shown that this nuclear factor plays an important role in regulating basal activity of the SLC25A19 promoter (37). The effect of chronic NNK exposure of 266-6 cells on the expression of the transcription factor NF-Y was examined and showed no significant change in level of this transcription factor (data not shown). Possible involvement of epigenetic mechanisms in the NNK effect on Slc25a19 transcription in PAC was then examined. We focused on possible changes in DNA methylation at CpG islands and on specific modifications in the NH2-terminal tails of histones, since they represent important mechanism for modulating transcriptional activity (9–11, 17–19). We have identified the CpG islands of the murine Slc25a19 gene using the Methprimer program and reported their location at −335 to −178 and −143 to −38 relative to TSS (46). These CpG islands in the Slc25a19 promoter were PCR amplified using the bisulfite-converted DNA from control and NNK-exposed mice PAC and from 266-6 cells, cloned in pGEM-T Easy vector and subjected to sequencing as described (2, 46, 47). The results again showed no significant alterations in DNA methylation at the identified CpG islands of the Slc25a19 promoter as a result of NNK exposure. These findings suggest that mechanism(s) other than DNA methylation at the CpG islands is involved in mediating the inhibitory effect of NNK exposure on activity of the Slc25a19 promoter.

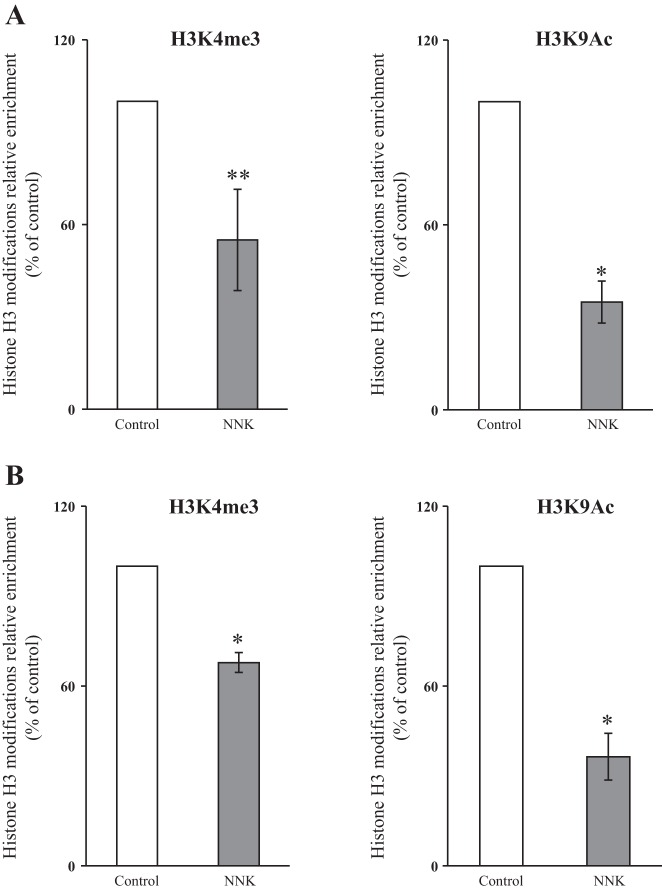

A possible role for histone modifications in mediating the inhibitory effect of NNK exposure on Slc25a19 transcriptional activity was then examined in 266-6 cells. Results of the ChIP-qPCR analysis of promoter regions −266 to −137 and −131 to +10 (TSS = +1) showed a significant decrease in the euchromatin markers H3K4me3 (P < 0.05 for the −266 to −137 region, and P < 0.01 for the −131 to +10 region) and H3K9Ac (P < 0.01 for both of the regions) (Fig. 5, A and B). These results indicate that NNK exposure negatively affects euchromatin markers and leads to a heterochromatin pattern at the Slc25a19 promoter, which may contribute to the reduction in promoter activity and in level of expression of the MTPPT mRNA.

Fig. 5.

Chronic exposure of mice to NNK decreases H3K4me3 and H3K9Ac euchromatin marks at −266 to −137 (A) and −131 to +10 (B) regions of the mouse Slc25a19 promoter. The 266-6 cells were exposed to NNK (3 μM, 24 h), and the formaldehyde cross-linked chromatin was immunoprecipitated using antibodies specific to histone H3, H3K4me3, and H3K9Ac. DNA was purified from the immunoprecipitated complexes, followed by qPCR analysis of the mouse Slc25a19 promoter spanning the region −266 to −137 and −131 to +10. Values were normalized relative to input DNA and expressed as percentage of enrichment relative to H3. *P < 0.01. **P < 0.05.

Role of the α7-nAchR Receptor in Mediating the NNK Effects on MTPPT Physiology/Molecular Biology: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies

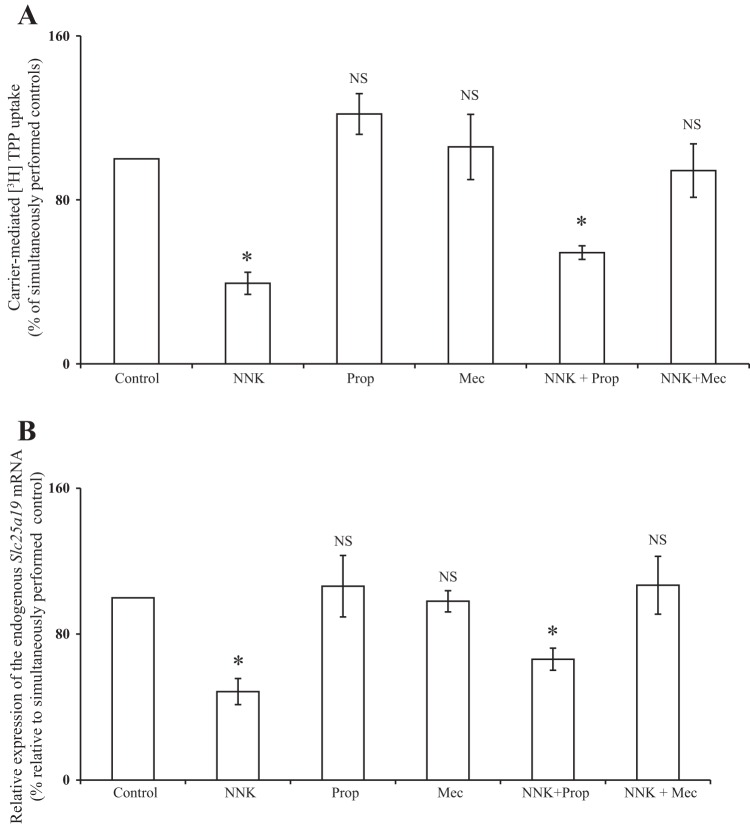

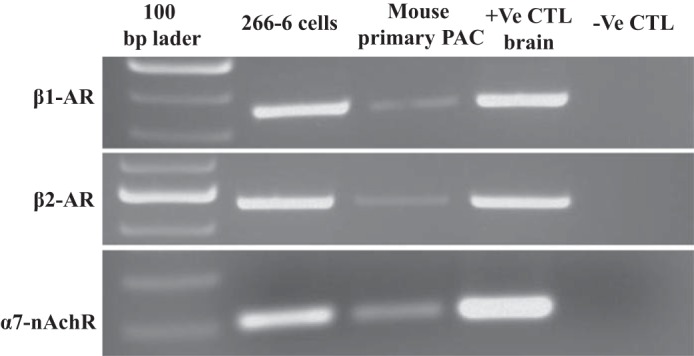

Previous studies have shown that NNK induces early pancreatitis responses in rats (2). It has also been shown that NNK has a high affinity for both β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs) and nAChRs (42, 43). Both β-ARs and nAChRs receptors are expressed in PACs (16), and some of the NNK-mediated effects (e.g., zymogen activation) have been shown to depend on a nonneuronal nAChR (2). Here we examined whether NNK effect on MTPP uptake is mediated by the β-ARs and/or the nonneuronal nAChR receptors. We confirmed the expression of the β1-AR, β2-AR, and α7-nAchR receptors by PCR using gene-specific primers and cDNA from 266-6 cells (Fig. 6). To identify the receptor through which NNK mediates its effect on MTPP transport, the 266-6 cells were treated (for 24 h) with a pharmacological inhibitor of the β-AR blocker, i.e., propranolol (10 μM), or a nAChR blocker, mecamylamine (500 μM); NNK (3 μM) was added to these cell 30 min following the addition of these inhibitors. The growth medium containing the above-mentioned compounds was changed every 8 h. [3H]TPP uptake was then performed using freshly isolated mitochondria from the treated cells. The results showed that propranolol did not alter the inhibition caused by NNK in MTPP uptake, but mecamylamine completely abolished the inhibitory effect of NNK on MTPP uptake (Fig. 7A). Similar results were also seen at the level of expression of the mouse Slc25a19 mRNA in 266-6 cells treated with the above-mentioned compounds. Thus there was no change in the level of mRNA expression in cells treated with propranolol, but a complete reversal of the NNK inhibition was seen in cells treated with mecamylamine (Fig. 7B). These results indicate that NNK effect on PAC MTPP uptake physiology is likely mediated by the nAChR.

Fig. 6.

β-ARs and α7-nAChRs mRNA are expressed in 266-6 cells. β1-AR, β2-AR, and α7-nAChR were PCR amplified using gene-specific primers, and cDNA was reverse-transcribed using 1 μg of RNA isolated from 266-6 cells. Control (CTL) tissue [positive (+ve)] was brain, and negative (−ve) CTL contained no cDNA. Amplicon of 440 bp, 559 bp, and 178 bp was observed for β1-AR, β2-AR, and α7-nAChR, respectively.

Fig. 7.

The nAChR blocker mecamylamine [Mec; but not the β-AR antagonist propranolol (Prop)] abrogates the inhibitory effect of NNK on mitochondrial [3H]TPP uptake (A), as well as the level of Slc25a19 mRNA (B) in 266-6 cells. The 266-6 cells were treated with Prop (10 μM) or Mec (500 μM) for 30 min, followed by addition of NNK (3 μM). Fresh media containing the same concentration of above-mentioned compounds were added every 8 h and continued for 24 h. Uptake was performed on freshly isolated mitochondria from these cells. RNA was isolated from cells exposed to above-mentioned conditions. Mouse endogenous Slc25a19 mRNA was quantitated using qPCR. *P < 0.01. NS, not significant.

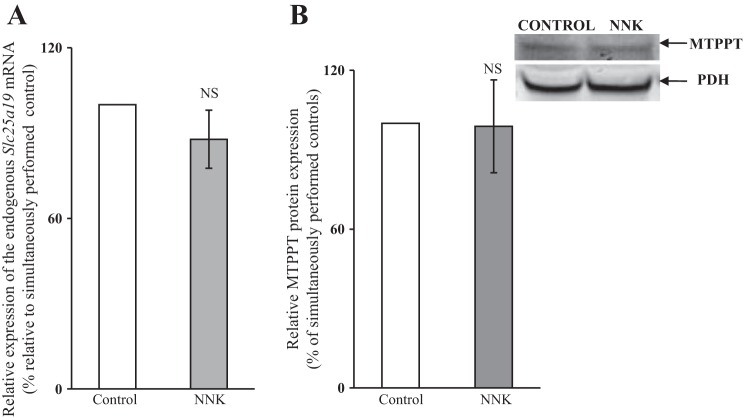

To further confirm these findings with 266 cells, we employed the α7-nAchR−/− mouse model and examined the effect of treating these animals with NNK on level of expression of MTPPT protein and mRNA in PAC. The results showed no significant decrease in MTPPT protein or mRNA levels in PAC of mice treated with NNK compared with controls (Fig. 8, A and B). These findings confirm that a nonneural nicotinic receptor mediates the effects of NNK on MTPPT.

Fig. 8.

Chronic exposure of α7-nAchR−/− mice to NNK does not affect the expression of MTPPT protein (A), or Slc25a19 mRNA (B) in PAC. α7-nAChR knockout mice were exposed to NNK (10 mg/100 g body wt; Ref. 26) for 2 wk, and their controls were injected with saline. RNA and protein were isolated as described before from the NNK-injected and the control mice. Level of protein expression was determined by Western blotting, and mouse endogenous Slc25a19 mRNA was quantitated using qPCR. NS, not significant.

DISCUSSION

The availability of adequate intracellular thiamin is critical for key cellular functions, including mitochondrial ATP production. Thiamin is transported into cells across the plasma membrane by THTR-1 and -2 and converted to TPP in the cytoplasm. Although mitochondria uses around 90% of total cellular thiamin, there is no synthesis of TPP in this organelle (6). MTPPT (encoded by Slc25a19) is responsible for the transport of TPP from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria (25, 33). The TPP that is transported into the mitochondria is used by enzymes involved in oxidative phosphorylation, ATP production, and reduction of oxidative stress (7). Therefore, any factors that disrupt the mitochondrial transport of TPP would negatively impact the resting energy and oxidative states of the pancreas and increase its susceptibility to injury.

There is a wealth of evidence to suggest that CS is a significant risk factor for the development and progression of pancreatic injury. Furthermore, components of CS, such as NNK, can exert multiple negative effects on pancreatic acinar physiology and function (1, 3–5, 14, 24, 28, 35, 36, 54). Our laboratory has previously shown that NNK negatively affects the transport of thiamin into the cytoplasm across cell membrane, and that the effect is mediated at the level of transcription of the Slc19A2 and Slc19A3 genes that encode THTR-1 and -2, respectively (47). The aim of the present study is to understand the effect of chronic exposure of PAC to NNK on MTPPT. We employed both an in vitro model (mouse pancreatic acinar tumor cell line 266-6 exposed to 3 μM NNK) and an in vivo model (mice injected with 10 mg/100 g body wt of NNK three times per week for 2 wk) of NNK exposure in our investigations.

The chronic/long-term exposure of 266-6 cells to NNK led to a significant inhibition in carrier-mediated TPP uptake by freshly isolated mitochondria, which was associated with a significant reduction in the level of total cellular ATP. Furthermore, a significant decrease in the expression of the MTPPT protein and Slc25a19 mRNA was also observed. Pancreatic acinar 266-6 cells transfected with SLC25A19 promoter exhibited a significant reduction in promoter activity (luciferase assay) following NNK treatment, which indicates that the negative effect of NNK on MTPP uptake and expression of the MTPPT mRNA is, at least in part, mediated at the level of transcription of the Slc25a19 gene.

In the in vivo model, we exposed wild-type and transgenic mice carrying the human SLC25A19 promoter chronically to NNK and examined the effect(s) of such treatment on different physiological and molecular parameters of the MTPPT process using freshly isolated mitochondria from PAC (the use of transgenic mice allowed for direct examination of the effect of in vivo exposure to NNK on promoter activity). Similar results to those seen with the in vitro model of exposure were observed in the in vivo model as well, where NNK treatment led to a significant inhibition in pancreatic acinar MTPP uptake, and in level of expression of mouse MTPPT at the protein, mRNA, and hnRNA levels. The latter finding suggests possible involvement of a transcriptional mechanism(s) in the observed inhibitory effects of NNK on PAC MTPP uptake. This suggestion was further confirmed by the observation of a significant reduction in the activity of the SLC25A19 promoter in PAC of the NNK-treated transgenic mice compared with their untreated controls. These results confirm and complement our in vitro findings and suggest that chronic NNK exposure negatively impacts PAC MTPP uptake, and that the effect is at least partially mediated at the level of transcription of SLC25A19 gene.

The transcriptional (promoter) activity of genes can be regulated by various molecular mechanisms, which in turn can be influenced by various environmental factors. The most common mechanisms involved in the regulation of promoter activity are changes in the expression level of a critical transcription factor that is essential for promoter activity and/or through epigenetic mechanisms involving DNA methylation and/or histone modifications. We investigated both of these possibilities and found that the key transcription factor NF-Y [which plays a major role in regulating basal activity of the SLC25A19 promoter (37)] is not affected by chronic exposure to NNK.

With regards to epigenetic mechanisms, previous studies have shown that exposure to NNK (and to CS) leads to changes in DNA methylation status of certain genes (29, 32). However, no such changes in the CpG islands of the Slc25a19 were found in our in vitro and in vivo NNK exposure studies. Similarly, CS has been shown to affect expression of certain genes via histone modifications (15, 22, 26, 51, 52, 57). The histone H3 protein undergoes posttranslational modification via addition or removal of four classes of chemical groups: methyl, acetyl, phosphate, and ubiquitin (30). These modifications, which predominantly occur in a lysine residue, can lead to either a change in heterochromatin or a euchromatin structure, depending on the position of the lysine residue and the chemical group added. We focused on two specific histone modifications, trimethylation of histone 3 at the lysine 4 (H3K4me3) and acetylation of histone 3 at the lysine 9 (H3K9Ac), both euchromatin markers. Our findings showed that chronic NNK exposure leads to a significant decrease in euchromatin formation (by decreasing H3K4me3 and H3K9Ac histone modifications), thereby favoring a heterochromatin structure at the Slc25A19 promoter. This, in turn, could lead to a decrease in Slc25A19 expression, and thus to a negative effect on PAC MTPP uptake.

NNK is known to be a high-affinity ligand for nAChRs and β-ARs, and these receptors are, therefore, candidate targets for NNK in pancreatic disease (53). Previous studies have shown that NNK can initiate its effects through α7-nAChR- and β-AR-mediated pathways in pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer (2). In addition, both receptor types have been shown to be present in rodent PACs (2). To determine which of these receptor type(s) are involved in mediating the effect of NNK on MTPP transport, we first confirmed that the receptors are expressed endogenously in the acinar 266-6 cells used in our studies. We then examined the effect of exposure to NNK on MTPP transport after pretreating the cells with either nicotinic receptor antagonist mecamylamine or β-AR blocker propranolol. The results showed that mecamylamine significantly abrogated the inhibitory effect of NKK (in the level of uptake and mRNA), whereas propranolol did not show any effect. These findings were further confirmed using α7-nAchR−/− mice injected with NNK and found that NNK exposure did not decrease the expression of Slc25a19 mRNA and MTPPT protein expression. These finding suggest that NNK mediates its inhibitory effect on PAC MTPP transport through the α7-nAChR. α7-nAChR is an ion channel that demonstrates a high permeability for Ca2+ (23). Exposure to NNK, a high-affinity antagonist of the α7-nAChR, significantly increases intracellular Ca2+ levels in human lung carcinoma (44). This increase in Ca2+ might, in turn, modulate downstream mediators that could regulate the transcription of the Slc25a19 gene. The exact pathway by which NNK mediates the above-mentioned effect on Slc25a19 through the α7-nAChR is an important topic for future studies.

In summary, our findings show, for the first time, that the effect of chronic exposure of PAC to NNK negatively impacts pancreatic MTPPT function. These effects appear to be mediated, at least in part, by decreasing transcription of the SLC25A19 gene and may involve epigenetic mechanisms. In addition, our results also indicate a potential contribution from α7-nAChR-mediated pathways following exposure of PAC to NNK. Whether the genetic and receptor-mediated mechanisms regulate NNK effects on MTPPT expression and function independently, or in tandem, remains the focus of future research.

GRANTS

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Veterans Affairs (AA018071 and DK-56061).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.S., E.C.T., F.S.G., and H.M.S. conception and design of research; P.S. and E.C.T. performed experiments; P.S. analyzed data; P.S., E.C.T., and F.S.G. interpreted results of experiments; P.S. prepared figures; P.S. and H.M.S. drafted manuscript; P.S., E.C.T., F.S.G., and H.M.S. edited and revised manuscript; P.S., E.C.T., F.S.G., and H.M.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexandre M, Pandol SJ, Gorelick FS, Thrower EC. The emerging role of smoking in the development of pancreatitis. Pancreatology 11: 469–474, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexandre M, Uduman AK, Minervini S, Raoof A, Shugrue CA, Akinbiyi EO, Patel V, Shitia M, Kolodecik TR, Patton R, Gorelick FS, Thrower EC. Tobacco carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone initiates and enhances pancreatitis responses. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 303: G696–G704, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alsamarrai A, Das SL, Windsor JA, Petrov MS. Factors that affect risk for pancreatic disease in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 12: 1635–1644.e5; quiz e103, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andriulli A, Botteri E, Almasio PL, Vantini I, Uomo G, Maisonneuve P; ad hoc Committee of the Italian Association for the Study of the Pancreas. Smoking as a cofactor for causation of chronic pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Pancreas 39: 1205–1210, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Askari MDF, Tsao MS, Schuller HM. The tobacco-specific carcinogen, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone stimulates proliferation of immortalized human pancreatic duct epithelia through beta-adrenergic transactivation of EGF receptors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 131: 639–648, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barile M, Passarella S, Quagliariello E. Thiamine pyrophosphate uptake into isolated rat liver mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys 280: 352–357, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berdanier CD. Advanced Nutrition-Micronutrients. New York: CRC, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bettendorff L, Goessens G, Sluse F, Wins P, Bureau M, Laschet J, Grisar T. Thiamine deficiency in cultured neuroblastoma cells: effect on mitochondrial function and peripheral benzodiazepine receptors. J Neurochem 64: 2013–2021, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleich S, Lenz B, Ziegenbein M, Beutler S, Frieling H, Kornhuber J, Bonsch D. Epigenetic DNA hypermethylation of the HERP gene promoter induces down-regulation of its mRNA expression in patients with alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30: 587–591, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonsch D, Lenz B, Fiszer R, Frieling H, Kornhuber J, Bleich S. Lowered DNA methyltransferase (DNMT-3b) mRNA expression is associated with genomic DNA hypermethylation in patients with chronic alcoholism. J Neural Transm 113: 1299–1304, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonsch D, Lenz B, Reulbach U, Kornhuber J, Bleich S. Homocysteine associated genomic DNA hypermethylation in patients with chronic alcoholism. J Neural Transm 111: 1611–1616, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruin JE, Petre MA, Raha S, Morrison KM, Gerstein HC, Holloway AC. Fetal and neonatal nicotine exposure in Wistar rats causes progressive pancreatic mitochondrial damage and beta cell dysfunction. PloS One 3: , 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calingasan NY, Chun WJ, Park LC, Uchida K, Gibson GE. Oxidative stress is associated with region-specific neuronal death during thiamine deficiency. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 58: 946–958, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chowdhury P, MacLeod S, Udupa KB, Rayford PL. Pathophysiological effects of nicotine on the pancreas: an update. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 227: 445–454, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung S, Sundar IK, Yao H, Ho YS, Rahman I. Glutaredoxin 1 regulates cigarette smoke-mediated lung inflammation through differential modulation of IκB kinases in mice: impact on histone acetylation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 299: L192–L203, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cusaro G, Rindi G, Sciorelli G. Subcellular distribution of thiamine-pyrophosphokinase and thiamine-pyrophosphatase activities in rat isolated enterocytes. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 47: 99–106, 1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Addario C, Caputi FF, Ekstrom TJ, Di Benedetto M, Maccarrone M, Romualdi P, Candeletti S. Ethanol induces epigenetic modulation of prodynorphin and pronociceptin gene expression in the rat amygdala complex. J Mol Neurosci 49: 312–319, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D'Addario C, Johansson S, Candeletti S, Romualdi P, Ögren SO, Terenius L, Ekstrom TJ. Ethanol and acetaldehyde exposure induces specific epigenetic modifications in the prodynorphin gene promoter in a human neuroblastoma cell line. FASEB J 25: 1069–1075, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deaton AM, Bird A. CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes Dev 25: 1010–1022, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deus B, Blum H. Subcellular distribution of thiamine pyrophosphokinase activity in rat liver and erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 219: 489–492, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di YP, Zhao J, Harper R. Cigarette smoke induces MUC5AC protein expression through the activation of Sp1. J Biol Chem 287: 27948–27958, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Escobar J, Pereda J, Lopez-Rodas G, Sastre J. Redox signaling and histone acetylation in acute pancreatitis. Free Radic Biol Med 52: 819–837, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gopalakrishnan M, Buisson B, Touma E, Giordano T, Campbell JE, Hu IC, Donnelly-Roberts D, Arneric SP, Bertrand D, Sullivan JP. Stable expression and pharmacological properties of the human alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Eur J Pharmacol 290: 237–246, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jianyu H, Guang L, Baosen P. Evidence for cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress in the rat pancreas. Inhal Toxicol 21: 1007–1012, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang J, Samuels DC. The evidence that the DNC (SLC25A19) is not the mitochondrial deoxyribonucleotide carrier. Mitochondrion 8: 103–108, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koenig A, Linhart T, Schlengemann K, Reutlinger K, Wegele J, Adler G, Singh G, Hofmann L, Kunsch S, Buch T, Schafer E, Gress TM, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Ellenrieder V. NFAT-induced histone acetylation relay switch promotes c-Myc-dependent growth in pancreatic cancer cells. Gastroenterology 138: 1189–1199.e1-2, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumaki Y, Oda M, Okano M. QUMA: quantification tool for methylation analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 36: 170–175, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Law R, Parsi M, Lopez R, Zuccaro G, Stevens T. Cigarette smoking is independently associated with chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology 10: 54–59, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee KWK, Pausova Z. Cigarette smoking and DNA methylation. Front Genet 4: 132–132, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 128: 707–719, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li LC, Dahiya R. MethPrimer: designing primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics 18: 1427–1431, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin RK, Hsieh YS, Lin P, Hsu HS, Chen CY, Tang YA, Lee CF, Wang YC. The tobacco-specific carcinogen NNK induces DNA methyltransferase 1 accumulation and tumor suppressor gene hypermethylation in mice and lung cancer patients. J Clin Invest 120: 521–532, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindhurst MJ, Fiermonte G, Song S, Struys E, De Leonardis F, Schwartzberg PL, Chen A, Castegna A, Verhoeven N, Mathews CK, Palmieri F, Biesecker LG. Knockout of Slc25a19 causes mitochondrial thiamine pyrophosphate depletion, embryonic lethality, CNS malformations, and anemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 15927–15932, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2[-delta delta C(T)] method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB, Mullhaupt B, Cavallini G, Lankisch PG, Andersen JR, Dimagno EP, Andren-Sandberg A, Domellof L, Frulloni L, Ammann RW. Cigarette smoking accelerates progression of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Gut 54: 510–514, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malfertheiner P, Schutte K. Smoking–a trigger for chronic inflammation and cancer development in the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol 101: 160–162, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nabokina SM, Valle JE, Said HM. Characterization of the human mitochondrial thiamine pyrophosphate transporter SLC25A19 minimal promoter: a role for NF-Y in regulating basal transcription. Gene 528: 248–255, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prokopczyk B, Hoffmann D, Bologna M, Cunningham AJ, Trushin N, Akerkar S, Boyiri T, Amin S, Desai D, Colosimo S, Pittman B, Leder G, Ramadani M, Henne-Bruns D, Beger HG, El-Bayoumy K. Identification of tobacco-derived compounds in human pancreatic juice. Chem Res Toxicol 15: 677–685, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rathanaswami P, Pourany A, Sundaresan R. Effects of thiamine deficiency on the secretion of insulin and the metabolism of glucose in isolated rat pancreatic islets. Biochem Int 25: 577–583, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rathanaswami P, Sundaresan R. Effects of thiamine deficiency on the biosynthesis of insulin in rats. Biochem Int 24: 1057–1062, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Said HM, Mee L, Sekar VT, Ashokkumar B, Pandol SJ. Mechanism and regulation of folate uptake by pancreatic acinar cells: effect of chronic alcohol consumption. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 298: G985–G993, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schuller HM. Nitrosamines as nicotinic receptor ligands. Life Sci 80: 2274–2280, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schuller HM, Tithof PK, Williams M, Plummer H 3rd. The tobacco-specific carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone is a beta-adrenergic agonist and stimulates DNA synthesis in lung adenocarcinoma via beta-adrenergic receptor-mediated release of arachidonic acid. Cancer Res 59: 4510–4515, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheppard BJ, Williams M, Plummer HK, Schuller HM. Activation of voltage-operated Ca2+-channels in human small cell lung carcinoma by the tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Int J Oncol 16: 513–518, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srinivasan P, Kapadia R, Biswas A, Said HM. Chronic alcohol exposure inhibits biotin uptake by pancreatic acinar cells: possible involvement of epigenetic mechanisms. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 307: G941–G949, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Srinivasan P, Nabokina SM, Said HM. Chronic alcohol exposure affects pancreatic acinar mitochondrial thiamin pyrophosphate uptake: Studies with mouse 266-6 cell line and primary cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 309: G750–G758, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srinivasan P, Subramanian VS, Said HM. Effect of the cigarette smoke component, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), on physiological and molecular parameters of thiamin uptake by pancreatic acinar cells. PloS One 8: , 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Srinivasan P, Subramanian VS, Said HM. Mechanisms involved in the inhibitory effect of chronic alcohol exposure on pancreatic acinar thiamin uptake. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 306: G631–G639, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Srinivasan P, Thrower EC, Loganathan G, Balamurugan AN, Subramanian VS, Gorelick FS, Said HM. Chronic nicotine exposure in vivo and in vitro inhibits vitamin B1 (thiamin) uptake by pancreatic acinar cells. PloS One 10: , 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Subramanian VS, Subramanya SB, Said HM. Relative contribution of THTR-1 and THTR-2 in thiamin uptake by pancreatic acinar cells: studies utilizing Slc19a2 and Slc19a3 knockout mouse models. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302: G572–G578, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sundar IK, Chung S, Hwang JW, Lapek JD Jr, Bulger M, Friedman AE, Yao H, Davie JR, Rahman I. Mitogen- and stress-activated kinase 1 (MSK1) regulates cigarette smoke-induced histone modifications on NF-kappaB-dependent genes. PloS One 7: , 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sundar IK, Nevid MZ, Friedman AE, Rahman I. Cigarette smoke induces distinct histone modifications in lung cells: implications for the pathogenesis of COPD and lung cancer. J Proteome Res 13: 982–996, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thrower E. Pathologic cellular events in smoking-related pancreatitis. Cancers (Basel) 7: 723–735, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wittel UA, Pandey KK, Andrianifahanana M, Johansson SL, Cullen DM, Akhter MP, Brand RE, Prokopczyk B, Batra SK. Chronic pancreatic inflammation induced by environmental tobacco smoke inhalation in rats. Am J Gastroenterol 101: 148–159, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Word B, Lyn-Cook LE, Mwamba B, Wang H, Lyn-Cook B, Hammons G. Cigarette smoke condensate induces differential expression and promoter methylation profiles of critical genes involved in lung cancer in NL-20 lung cells in vitro: short-term and chronic exposure. Int J Toxicol 32: 23–31, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu H, Ferro TJ, Chu S. Cigarette smoke condensate inhibits ENaC alpha-subunit expression in lung epithelial cells. Eur Respir J 30: 633–642, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yao H, Hwang JW, Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT, Leitges M, Kishore N, Li X, Rahman I. Protein kinase C zeta mediates cigarette smoke/aldehyde- and lipopolysaccharide-induced lung inflammation and histone modifications. J Biol Chem 285: 5405–5416, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zangen A, Shainberg A. Thiamine deficiency in cardiac cells in culture. Biochem Pharmacol 54: 575–582, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]