Abstract

Oxidatively induced DNA damage is caused in living organisms by a variety of damaging agents, resulting in the formation of a multiplicity of lesions, which are mutagenic and cytotoxic. Unless repaired by DNA repair mechanisms before DNA replication, DNA lesions can lead to genomic instability, which is one of the hallmarks of cancer. Oxidatively induced DNA damage is mainly repaired by base excision repair pathway with the involvement of a plethora of proteins. Cancer tissues develop greater DNA repair capacity than normal tissues by overexpressing DNA repair proteins. Increased DNA repair in tumors that removes DNA lesions generated by therapeutic agents before they became toxic is a major mechanism in the development of therapy resistance. Evidence suggests that DNA repair capacity may be a predictive biomarker of patient response. Thus, knowledge of DNA–protein expressions in disease-free and cancerous tissues may help predict and guide development of treatments and yield the best therapeutic response. Our laboratory has developed methodologies that use mass spectrometry with isotope dilution for the measurement of expression of DNA repair proteins in human tissues and cultured cells. For this purpose, full-length 15N-labeled analogs of a number of human DNA repair proteins have been produced and purified to be used as internal standards for positive identification and accurate quantification. This chapter describes in detail the protocols of this work. The use of 15N-labeled proteins as internal standards for the measurement of several DNA repair proteins in vivo is also presented.

1. INTRODUCTION

Exogenous and endogenous sources such as free radicals and ionizing radiation generate oxidatively induced DNA damage by a variety of mechanisms, resulting in the formation of modified bases and sugars, DNA–protein cross-links, strand breaks, base-free sites, and tandem lesions such as 8,5′-cyclopurine-2′-deoxyribonucleosides and clustered damaged sites (reviewed in Dizdaroglu & Jaruga, 2012; Evans, Dizdaroglu, & Cooke, 2004). This type of DNA damage is thought to play an important role in disease processes such as carcinogenesis and aging (reviewed in Dizdaroglu, 2015; Friedberg et al., 2006). Elaborate DNA repair pathways exist in mammalian cells with approximately 150 different proteins involved (reviewed in Friedberg et al., 2006; Wood, Mitchell, & Lindahl, 2005). DNA repair deficiencies cause accumulation of DNA damage and mutations, leading to genomic instability, which is a major factor in carcinogenesis (Beckman & Loeb, 2005; Helleday, Petermann, Lundin, Hodgson, & Sharma, 2008; Hoeijmakers, 2001; Kelley, 2012; Liu, Yin, & Pu, 2007; Loeb, 2011; Madhusudan & Middleton, 2005). Oxidatively induced DNA damage is mainly repaired by base excision repair (BER) and also by nucleotide excision repair (NER), albeit to a lesser extent (Friedberg et al., 2006). In the first step of BER, DNA glycosylases hydrolyze the N-glycosidic bond releasing the damaged base and generating an abasic site, followed by the action of a series of other BER enzymes (Gros, Saparbaev, & Laval, 2002; Hegde, Hazra, & Mitra, 2008). Formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase (Fpg, also called MutM) is one of the main DNA glycosylases in Escherichia coli, which specifically excises 4,6-diamino-5-formamidopyrimidine (FapyAde), 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine (FapyGua), and 8-hydroxyguanine (8-OH-Gua) from DNA containing multiple lesions (Boiteux, Gajewski, Laval, & Dizdaroglu, 1992; Dizdaroglu, 2005). In eukaryotes, 8-oxoguanine-DNA glycosylase (OGG1) including human OGG1 (hOGG1), which is a functional homolog of Fpg, exhibits a strong specificity for FapyGua and 8-OH-Gua, but does not act on FapyAde (Audebert, Radicella, & Dizdaroglu, 2000; Dherin, Radicella, Dizdaroglu, & Boiteux, 1999; Hu et al., 2005; Sidorenko, Grollman, Jaruga, Dizdaroglu, & Zharkov, 2009).

Mammalian NEIL1 protein, which is a E. coli Nei-like DNA glycosylase with an additional β,δ-elimination activity, has been discovered in eukaryotes (Bandaru, Sunkara, Wallace, & Bond, 2002; Hazra et al., 2002). This enzyme is unique in that it specifically removes FapyAde and FapyGua from DNA with multiple lesions, without exhibiting any significant activity for 8-OH-Gua (Bandaru et al., 2002; Chan et al., 2009; Doublie, Bandaru, Bond, & Wallace, 2004; Hazra et al., 2002; Hu et al., 2005; Jaruga, Birincioglu, Rosenquist, & Dizdaroglu, 2004; Liu et al., 2010; Muftuoglu et al., 2009; Rosenquist et al., 2003; Roy et al., 2007). The involvement of NEIL1 in NER has also been suggested on the basis of accumulation of 8,5′ -cyclopurine-2′-deoxyribonucleosides in nei1−/− mice (Jaruga, Xiao, Vartanian, Lloyd, & Dizdaroglu, 2010). Homologs of E. coli Nth have also been found in yeast and mammals (Aspinwall et al., 1997; Roldán-Arjona, Anselmino, & Lindahl, 1996). Mammalian NTH1 mainly acted on pyrimidine-derived lesions, exhibiting a narrower substrate specificity than E. coli Nth (Karahalil, Roldan-Arjona, & Dizdaroglu, 1998; Roldán-Arjona et al., 1996); however, evidence has also been provided for purine-derived FapyAde to be the physiological substrate of NTH1 (Chan et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2005).

Other enzymes such as apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) and DNA polymerase β (Pol β) also play vital roles in BER. Abasic sites, which are left behind following removal of modified DNA bases by DNA glycosylases, are processed by APE1 (Demple, Herman, & Chen, 1991). APE1 provides over 95% of the total endonuclease function with some additional critical functions (Abbotts & Madhusudan, 2010; Barnes et al., 2009; Demple & Harrison, 1994; Demple et al., 1991; Fishel, Vascotto, & Kelley, 2013; Gros, Ishchenko, Ide, Elder, & Saparbaev, 2004; Tell, Quadrifoglio, Tiribelli, & Kelley, 2009; Wilson & Barsky, 2001; Xanthoudakis & Curran, 1992). The action of APE1 generates a one-nucleotide gap with a 3′-OH and a 5′-terminal 2′-deoxyribose phosphate (dRP) moiety. Pol β, which is found in all vertebrate species (Beard & Wilson, 2006, 2014; Braithwaite & Ito, 1993), binds to this gap and performs DNA synthesis with its DNA polymerase activity, filling in the gap. It then removes the blocking dRP moiety, paving the way for other enzymes such as DNA ligases to close the resulting gap to complete the repair of DNA (Beard & Wilson, 2000, 2006; Matsumoto & Kim, 1995; Srivastava et al., 1998).

Defects in BER enzymes such as those discussed above are associated with neurological disorders and cancer (Sampath, McCullough, & Lloyd, 2012; Wallace, Murphy, & Sweasy, 2012; Wilson, Kim, Berquist, & Sigurdson, 2011). Polymorphic variants of these enzymes have been found in human populations in connection to various cancer incidences (reviewed in Dizdaroglu, 2015). For example, neil1−/− mice developed obesity and symptoms of metabolic syndrome (Vartanian et al., 2006). Male and female neil1−/− and nth1−/− mice developed pulmonary and hepatocellular tumors to an extent up to ≈ 15%. A dramatic increase up to 75% in cancer incidence has been observed in neil1−/− nth1−/−male and female mice (Chan et al., 2009). In mice with both deleted alleles of ape1, early embryonic lethality has been observed; similarly, APE1 heterozygous mice exhibited increased oxidative stress, spontaneous mutagenesis and cancer incidences, and reduced survival of pups and embryos (Cabelof, 2012; Hakem, 2008; Huamani et al., 2004; Meira et al., 2001; Xanthoudakis, Smeyne, Wallace, & Curran, 1996). Thus, accumulated evidence unequivocally points to the crucial role of BER enzymes in the maintenance of genetic stability and disease prevention.

It is now well known that overexpression of DNA repair proteins that may increase the DNA repair capacity is common in cancer (Helleday et al., 2008; Kelley, 2012; Madhusudan & Middleton, 2005). Increased and effective DNA repair capacity in tumors that removes DNA lesions generated by ionizing radiation and/or chemotherapy before they became toxic is a major mechanism to develop therapy resistance. Evidence suggests that DNA repair capacity might be a predictive biomarker of patient response (Kelley, 2012; Perry, Sultana, & Madhusudan, 2012). In this respect, BER proteins have emerged as biomarkers for assessment of the effectiveness and outcome of therapy (Chan & Bristow, 2010; Curtin, 2013; Fishel et al., 2013; Helleday, 2008; Helleday et al., 2008; Illuzzi & Wilson, 2012; Kelley, 2012; Madhusudan & Middleton, 2005; Moeller, Arap, & Pasqualini, 2010; Perry et al., 2012). Targeting MTH1 protein, which is not a BER protein, has been also suggested to be beneficial in cancer therapy (Gad et al., 2014; Huber et al., 2014). This enzyme dephosphorylates modified 2′-deoxynucleoside triphosphates in the nucleotide pool so that they cannot be incorporated into DNA during DNA replication, preventing cell death and mutations (Maki & Sekiguchi, 1992; Mo, Maki, & Sekiguchi, 1992; Sakai et al., 2002; Sakumi et al., 1993; Sekiguchi & Tsuzuki, 2002; Tsuzuki et al., 2001). Its overexpression has been observed in many cancers (Gad et al., 2014; Huber et al., 2014; Kennedy, Cueto, Belinsky, Lechner, & Pryor, 1998; Okamoto et al., 1996; Speina et al., 2005).

The determination of the overexpression or underexpression of DNA repair proteins in normal and cancer tissues may help predict and guide development of treatments, potentially yielding the greatest therapeutic response (Kelley, 2012). In general, expression levels of DNA repair proteins have been estimated by Western blot methods. With these methods, proteins are separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and identified by the use of an antibody specific to a target protein, meaning that they completely depend on a reliable and specific antibody resource. Antibodies may potentially exhibit some off-target binding, leading to false results. No positive identification and no absolute quantification are provided because of the lack of mass spectrometric evidence and suitable internal standards. Quantification is based on the estimation of stained area only. The molecular mass of a target protein is only estimated by the use of a molecular mass ladder of proteins. If DNA repair proteins are to be used as reliable biomarkers in cancer, their expression levels must be accurately measured in tissues, providing positive identification of a target protein and its absolute quantification. Mass spectrometry is the most suitable technique of choice for the measurement of proteins. The application of this technique would be essential for positive identification and accurate quantification of DNA repair proteins in human tissues using proper internal standards. Our laboratory has recently developed methodologies and stable isotope-labeled standards for the measurements of DNA repair proteins using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with isotope dilution (Coskun et al., 2015; Dizdaroglu, Reddy, & Jaruga, 2011; Kirkali et al., 2013; Reddy, Jaruga, Nelson, Lowenthal, & Dizdaroglu, 2011; Reddy et al., 2013). Stable isotope-labeled analogs of DNA repair proteins, which are to be used as internal standards, were produced, purified, and characterized. This chapter describes the procedures used for this purpose and the application of the developed internal standards for the measurement of DNA repair proteins.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Materials

Restriction endonucleases, DNA ligase, and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase were obtained from New England Biolabs (MA). Isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG), acrylamide, bisacrylamide, and Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Diethylaminoethyl (DEAE) cellulose (DE52) was from Whatman Laboratories. Shodex carboxymethyl cellulose HPLC preparative column (CM 2025) was from Phenomenex. YM10 membrane filters were from EMD Millipore Corporation (Bedford, MA). Ni-Sepharose column HisTrap HP and MonoQ anion-exchange column were obtained from GE Healthcare, Bio-Science (Uppsala, Sweden). BugBuster protein extraction reagent was from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Protease inhibitor cocktail was purchased from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). Benzonase nuclease was from Novagen (Denmark). 15N-NH4Cl was obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO).

2.2 E. coli Strains and Plasmids

The pET11a expression vector, for native protein production of EcFpg based on the IPTG induction, was obtained from Novagen, Madison, WI. The relevant strains for cloning and expression are E. coli Novablue (K12) and BL21(DE3), respectively. The human ogg1 gene in the expression vector pET15b for His-tagged production of the protein was kindly provided by Dr. Dmitry Zharkov through Prof. Arthur Grollman’s laboratory. The human neil1 gene in the expression vector pET28 for His-tagged production of the protein was kindly provided by Dr. Stephen Lloyd (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon). The human ape1 gene was provided by Dr. David M. Wilson III of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

2.3 Preparation of Minimal Medium

The composition of the medium was: 6 g NaH2PO4, 3 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g NaCl, and 1 g 15N-NH4Cl, 5 g glucose, 246 mg MgSO4·7H2O per liter. Ampicillin or kanamycin was added to a final concentration of 50 µg/mL or 25 µg/mL, respectively.

2.4 DNA Procedures

E. coli Novablue (K12) harboring a recombinant plasmid was grown at 37 °C overnight in 10 mL Luria-Bertani medium (Miller, 1972), containing the appropriate antibiotic. Minipreparations of plasmid DNA were purified using a Qiagen Kit. Digestion of DNA with restriction enzymes was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on SeaKem GTG agarose or NuSieve GTG agarose. DNA was purified using a Qiagen Kit. Ligation of DNA fragments was performed as described (Sambrook, Fritsch, & Maniatis, 1989). Competent cells of the E. coli strains used here were prepared by the Hanahan method (Hanahan, 1983; Sambrook et al., 1989).

3. PRODUCTION AND PURIFICATION OF E. COLI 15N-Fpg PROTEIN

3.1 Cloning of fpg Into pET11a Vector

The coding sequence for E. coli fpg gene from the plasmid pFpg was provided by Dr. Timothy R. O’Connor of the Beckman Research Institute of the City of Hope, Duarte, CA (O’Connor, Boiteux, & Laval, 1989). It was amplified by PCR with Pfu polymerase using a 5′-end primer (5′-GGAATTC CAT ATG CCT GAA TTA CCC GAA G-3′) and a 3′-end primer (5′-CCG CTC GAG TTA CTT CTG GCA CTG CCG AC-3′). The 5′-end primer sequence contained the NdeI restriction recognition sequence CATATG wherein ATG served as the initiation codon for protein expression. The 3′-end primer contained the TAA translation stop codon. The amplified product was digested with NdeI to produce the gene with 5′-NdeI protruding end and 3′-blunt end. The DNA fragment was purified from a 1% agarose gel, and cloned into the NdeI and BamHI (first digested with BamHI, filled in with DNA polymerase to make this blunt end, then digested with NdeI) sites of the pET11a expression vector. A recombinant plasmid pET11a/Fpg was isolated from E. coli Nova Blue cells. E. coli BL21 (DE3) was transformed with the recombinant plasmid to induce protein expression with IPTG.

3.2 Production of 15N-Fpg

E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring pET1 1a/Fpg recombinant plasmid was grown at 37 °C for 20 h on LB agar plate containing 100 µg/mL ampicillin. A colony was carefully (without touching into the LB medium) transferred to 10 mL minimal medium containing 1 mg 15N-NH4Cl/mL and 50 µg ampicillin/ mL. Cells were grown for 1 h at 37 °C at 250 rpm in a 50 mL tube. This inoculum was transferred to 140 mL minimal medium, in a 500 mL baffled flask, containing 15N-NH4Cl and ampicillin as above. This culture was grown at 37 °C for 16 h. Next, 3 × 50 mL of this seed culture was transferred to 3 × 450 mL of minimal medium containing 15N-NH4Cl and ampicillin in 3 × 2 L baffled flasks. IPTG was added to a final concentration of 30 µmol/L to induce 15N-Fpg production at 37° C for 1 h. Next, the culture was shifted 42° C for 5 h to continue 15N-Fpg production. Cells were harvested at 6000 × g for 20 min and washed with 25 mmol/L Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.5. The wet weight of cells obtained in this procedure was ≈3g.

3.3 Purification of 15N-Fpg

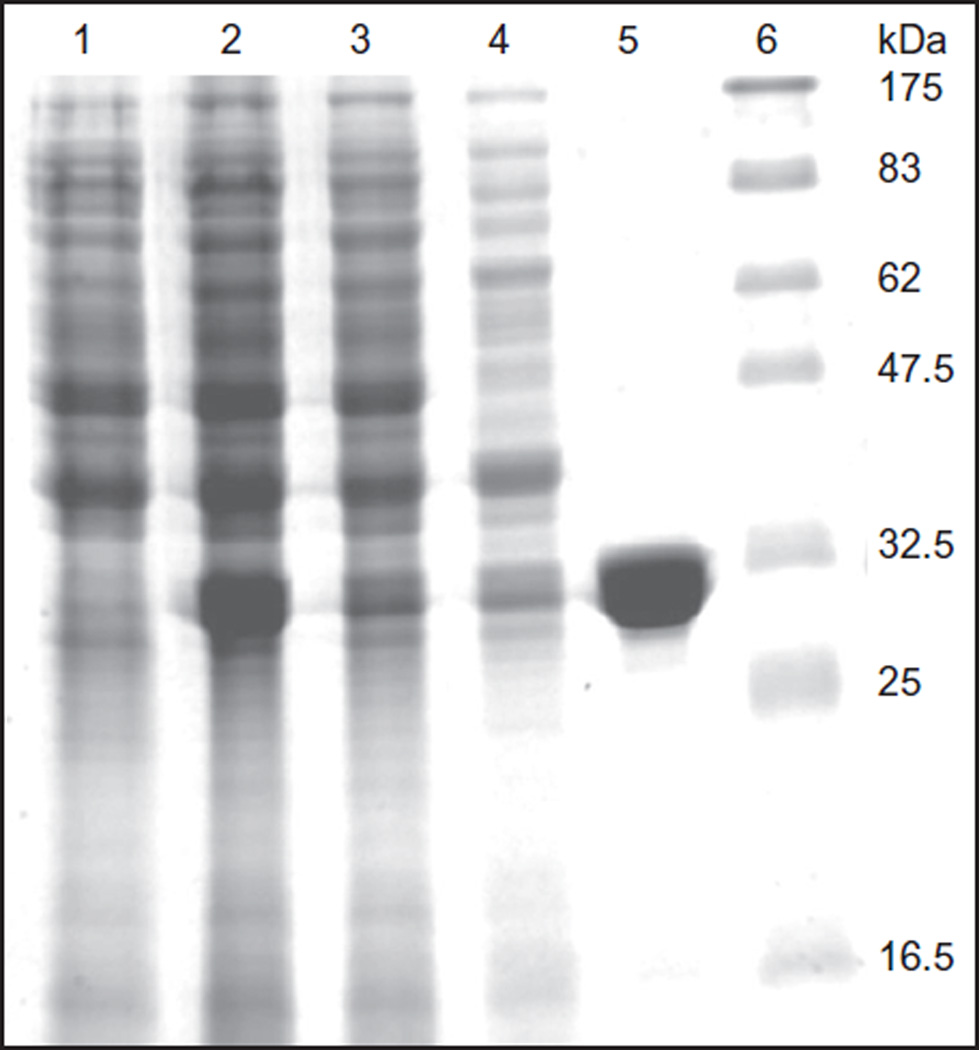

Cell pellet was suspended in 40 ml of 50 mmol/L Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 50 mmol/L NaCl (lysis buffer 1), containing one tablet of protease inhibitors. Cell suspension was passed through a French press at 7.1 × 104 kPa twice. The cell-free extract was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was mixed with 5 g of DE52 anion-exchange resin equilibrated with the lysis buffer 1 in a 500-mL bottle at 80 rpm for 1 h at 4 °C and then poured into a column. The flow through containing nearly all the 15N-Fpg and fewer cellular proteins was collected. The resin was washed with 10 mL of the lysis buffer 1 and added to the flow through. The 15N-Fpg enriched pool (50 mL) was dialyzed overnight against 1 L of 20 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The dialyzed pool was centrifuged at 100000 × g for 1 h to remove any particulate material. The supernatant was chromatographed on a HPLC-Shodex carboxymethyl cellulose column (2 cm × 20 cm) equilibrated with 20 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. The column was washed with 100 mL of 20 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 until the A280 stabilized. Then 15N-Fpg was eluted with a 0–0.5 mol/L potassium chloride gradient (250 mL each) in 20 mmol/L potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Pure 15N-Fpg was eluted as a sharp peak at ≈ 0.3 mol/L KCl. Fractions containing 15N-Fpg were pooled, concentrated on YM3 membrane filter, and dialyzed overnight against 500 mL of 50% glycerol, 20 mmol/L Tris–HCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, and 10 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.5. Protein concentration was determined by the Lowry method using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as standard (Lowry, Rosebrough, Farr, & Randall, 1951). Total yield of the protein was 1 mg. The SDS–PAGE and Coomassie staining of 15N-Fpg (lane 5) and protein molecular mass standards (lane 6) are shown in Fig. 1, indicating high purity of the labeled protein (Reddy et al., 2011).

Figure 1.

SDS (13%)-PAGE analysis of the purification steps of E. coli15N-Fpg: lane 1, 21 µg protein of the extract of BL21(DE3) cells harboring pET11a control plasmid; lane 2,31 µg protein of the extract of BL21(DE3) cells harboring Fpg/pET11a plasmid induced with IPTG; lane 3,26 µg of 10000 × g supernatant; lane 4,8.6 µg flow through from DEAE cellulose column, 29 µg; lane 5, 8.5 µg 15N-Fpg eluted from CM cellulose column, 26 µg; and lane 6, molecular mass markers. Data from Reddy et al. (2011).

4. PRODUCTION AND PURIFICATION OF 15N-hOGG1

4.1 Production of 15N-hOGG1

E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pET15b/hOGG1 recombinant plasmid was grown at 37 °C for 20 h on LB agar plate containing 100 µg/mL ampicillin. A colony was carefully (without touching into the LB medium) transferred to 100 mL minimal medium containing 1 mg 15N-NH4Cl/mL and 50 µg ampicillin/mL. Cells were grown overnight (16 h) at 37 °C at 250 rpm in a 250-mL baffled flask. This inoculum was transferred to 1000 mL minimal medium, in a 2000-mL baffled flask, containing 15N-NH4Cl and ampicillin as above. This culture was grown at 37 °C for 1 h and briefly cooled in ice water to room temperature. Next, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 100 µmol/L to induce 15N-hOGG1 production at 24° C overnight. Cells were harvested at 6000 × g for 20 min and washed with 25 mmol/L Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.5. The wet weight of cells obtained in this procedure was ≈2g.

4.2 Purification of 15N-hOGG1

The cell pellet was suspended in 20 mL of 50 mmol/L Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, 300 mmol/L NaCl, and 10 mmol/L imidazole (lysis buffer 2) containing one tablet of protease inhibitors. Cell suspension was passed through a French press at 7.1 × 104 kPa. The cell-free extract was centrifuged at 40000 × g for 1 h. Meanwhile, 2 mL of nickel-agarose slurry (1 mL resin) was washed with the lysis buffer 2 in a 30 mL Bio-Rad polypropylene column. The supernatant was added to the resin and mixed on a rocker for 2 h at 4 °C. The flow through was collected, and the column was washed successively with three 10-mL aliquots of the lysis buffer 2. Next, the resin was washed three times with 3-mL aliquots of the lysis buffer 2 containing an additional 20 mmol/L imidazole (total 30 mmol/L). Next, the 15N-hOGG1 was eluted with five 5-mL aliquots of the lysis buffer containing 100 mmol/L imidazole. The first 5 mL contained about 50% of 15N-hOGG1 (≈ 95% pure) with minor contaminants as judged by SDS–PAGE. The subsequent four elutions contained the remaining 15N-hOGG1 with higher purity (≈ 98%). All the five elutions containing 15N-hOGG1 were pooled, concentrated on YM3 membrane filter, and dialyzed overnight against 500 mL of 50% glycerol, 20 mmol/L Tris–HCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, and 10 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.5. Mass measurements and activity analysis of 15N-hOGG1 were carried out. Protein concentration was determined by the Lowry method using BSA as standard (Lowry et al., 1951). Total yield of the protein was 5.3 mg. Figure 2 shows the SDS–PAGE and Coomassie staining of 15N-hOGG1 (lane 5) and protein molecular mass standards (lane 6), indicating high purity of the labeled protein (Reddy et al., 2011).

Figure 2.

SDS (10%)-PAGE analysis of the purification steps of 15N-hOGG1: lane 1, 20 µg protein of the extract of BL21(DE3) cells harboring pET11a control plasmid; lane 2, 21 µg protein of the extract of BL21(DE3) cells harboring hOGG1/pET15b plasmid induced with IPTG; lane 3, 17 µg of 48000 × g supernatant; lane 4, 15.5 µg from Ni-agarose flow through; lane 5, 8.3 µg 15N-hOGG1 eluted from Ni-agarose column; and lane 6, molecular mass markers. Data from Reddy et al. (2011).

5. PRODUCTION AND PURIFICATION OF 15N-hNEIL1

5.1 Production of 15N-hNEIL1

E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring pET28/human neil1 recombinant plasmid was grown at 37 °C for 20 h on LB agar plate containing 100 µg ampicillin and 40 µg chloramphenicol/mL. A colony was carefully (without touching into the LB medium) transferred to 10 mL minimal medium containing 1 mg 15N-NH4Cl/mL, 50 µg ampicillin, and 20 µg chloramphenicol/mL. Cells were grown for 16 h at 37 °C at 250 rpm in a 50 mL tube. This inoculum was transferred to 90 mL minimal medium, in a 250 mL flask, containing 15N-NH4Cl, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol as above. This culture was grown at 37 °C for 9 h. Next, this seed culture was transferred to 900 mL of minimal medium containing 15N-NH4Cl, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol in a 2 L flask. This culture was grown at 37 °C for 4 h. Cells (A600 = 0.45) were briefly cooled in ice and 15N-hNEIL1 production was induced with 100 µmol IPTG/mL at 25 °C for 16 h. Cells were harvested at 6000 × g for 20 min and washed with 25 mmol/L Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5). The wet weight of cells obtained in this procedure was 2.8 g/L culture.

5.2 Purification of 15N-hNEIL1

Cell pellet was suspended at a rate of 1 g/10 mL of 50 mmol/L Na2HPO4–NaH2PO4 buffer (pH 8.0), 10 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mmol/L imidazole, and 300 mmol/L NaCl (lysis buffer). One tablet of protease inhibitors was added to the cell suspension. Cell suspension was passed through a French press at 7.1 × 104 kPa twice. The cell-free extract was centrifuged at 36000 × g for 30 min. Meanwhile, 1 mL of nickel-agarose slurry (0.5 mL resin) was washed with the lysis buffer in a 30-mL Bio-Rad polypropylene column. The supernatant was added to the resin and mixed on a rocker for 2 h at 4 °C. The flow through was collected, and the column was washed successively with three 10-mL aliquots of the lysis buffer. Next, the resin was washed successively two times with 10 mL aliquots of the lysis buffer containing an additional 30 mmol/L imidazole (total 40 mmol/L). Next, the resin was washed successively three times with 5-mL aliquots of the lysis buffer containing an additional 70 mmol/L imidazole (total 80 mmol/L). The first imidazole80 wash did elute about 30% of 15N-hNEIL1 with a number of contaminating proteins as judged by SDS–PAGE. The second and third imidazole80 washes eluted about 30% of nearly homo-geneous 15N-hNEIL1. Next, 15N-hNEIL1 was eluted successively with three 5 mL aliquots of the lysis buffer containing 150 mmol/L imidazole. The first 5 mL contained about 30% of 15N-hNEIL1. The subsequent two elutions contained the remaining 15N-hNEIL1. The second and third imidazole80 elutions and all the imidazole150 elutions were pooled and dialyzed overnight against 1 L of 50 mmol/L Na2HPO4–NaH2PO4 buffer (pH 8.0) and 300 mmol/L NaCl. Slight precipitate of 15N-hNEIL1 appeared after dialysis even in the presence of 300 mmol/L NaCl. The precipitate was centrifuged off from the dialyzed pool, and the clear supernatant was concentrated on NMLW5 membrane in an Amicon cell. The above purification procedure developed for cells from 1 L culture was proportionately scaled up to 5 L as and when needed. Protein concentration was determined by the Lowry method using BSA as the standard (Lowry et al., 1951). The final yield of 15N-hNEIL1 was ≈2 mg/L culture. The SDS–PAGE and Coomassie staining of 15N-hNEIL1 (lane 5) and protein molecular mass standards (lane 6) are presented in Fig. 3. A high purity of the labeled protein can be seen with a minor contaminant at ≈ 17 kDa (Reddy et al., 2013).

Figure 3.

SDS (10%)-PAGE analysis of the purification steps of 15N-hNEIL1: lane 1, uninduced cell extract, 24 µg; lane 2, induced cell extract, 28 µg; lane 3,20000 × g supernatant, 22 µg; lane 4, flow through from nickel resin, 17 µg; lane 5, pure 15N-NEIL1 eluted from nickel resin, 15 µg; and lane 6, molecular mass markers. Data from Reddy et al. (2013).

6. PRODUCTION AND PURIFICATION OF 15N-hAPE1

6.1 Production of 15N-hAPE1

E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring pET11/hAPE1 recombinant plasmid was grown at 37 °C for 20 h on LB agar plate containing 100 µg ampicillin/ mL. A colony was carefully (without touching into the LB medium) transferred to 10 mL minimal medium containing 50 µg ampicillin/mL. Cells were grown for 3 h at 37 °C at 250 rpm in a 50 mL tube. This inoculum was transferred to 200 mL minimal medium with 50 µg ampicillin/mL in a 500 mL flask. This culture was grown at 37 °C for 14 h. Next, each 50 mL of this seed culture was transferred to 4 × 1000 mL of minimal medium containing 15N-NH4Cl and ampicillin in 4 × 2 L flasks. This culture was grown at 37 °C for 6 h and then at 20 °C for 90 min. Cell density at this stage was A600 = 0.5. The production of 15N-hAPE1 was induced with 100 µmol IPTG/mL at 20 °C for 15 h. Cells were harvested at 6000 × g for 20 min and washed with 25 mmol/L Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5). The wet weight of cells obtained in this procedure was 2.25 g/L culture for a total of 9 g wet weight of cells.

6.2 Purification of 15N-hAPE1

Nine grams of cells from 4-L culture were suspended in 90 mL of lysis buffer A: 50 mmol/L HEPES–KOH buffer, pH 7.5, containing 5% glycerol, 50 mmol/L KCl, and 1 mmol/L DTT. Cells were broken by passing through a French press at 7.1 × 104 kPa. The cell-free extract was centrifuged at 70000 × g for 1 h. The supernatant was mixed with 5 g of DE52 anion-exchange resin equilibrated with the buffer A. The supernatant/resin slurry in a 250-ml bottle was mixed at 178 rpm for 1 h and then poured into a column. The flow through containing nearly all the 15N-hAE1 and ewer cellular proteins was collected. The resin was washed with 10 mL of the buffer A and added to the flow through. The 15N-hAPE1 enriched pool (100 mL) was chromatographed on a HPLC-Shodex carboxymethyl cellulose column (2.0 cm × 25 cm) equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 100 mL of buffer A until the A280 stabilized. Then 15N-hAPE1 was eluted with a potassium chloride gradient generated from buffer A and buffer A containing 0.65 mol/L KCl (250 mL each). Pure 15N-hAPE1 was eluted as a sharp peak at ≈ 0.3 mol/L KCl. Fractions containing 15N-hAPE1 were pooled, concentrated to ≈ 10 mg/mL on a YM10 membrane filter. The yield of 15N-hAPE1 from 4 L culture of minimal medium was 60 mg. Aliquots of the protein was stored at −70 °C. Figure 4, lane 6, shows the SDS–PAGE analysis and Coomassie staining of 15N-hAPE1 and protein molecular mass standards (lane 7), indicating high purity of the labeled protein (Kirkali et al., 2013).

Figure 4.

SDS (11%)-PAGE analysis of the purification steps of 15N-hAPE1: lane 1, uninduced cell extract, 24 µg; lane 2, induced cell extract, 28 µg; lane 3, 70000 × g supernatant, 24 µg; lane 4, flow through from DEAE cellulose column, 17 µg; lane 5, flow through from CM cellulose column, 16µg; lane 6, pure 15N-APE1 eluted from CM cellulose column, 21 µg; and lane 7, molecular mass markers. Data from Kirkali et al. (2013).

7. PRODUCTION AND PURIFICATION OF 15N-hMTH1

15N-hMTH1 was produced according to the procedures used for the production of hMTH1 (Svensson et al., 2011). 15N-hMTH1 was expressed from pET28a-hMTH1 in E. coli BL21(DE3) grown in a minimal medium (6 g Na2HPO4, 3 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g NaCl, 5 g glucose, 120.4 mg MgSO4 per liter) containing 1 g 15N-NH4Cl. The production was induced by addition of 200 µmol/L isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside. Cells were harvested by centrifugation after 16 h at 20 °C, and the obtained pellet was dissolved in BugBuster protein extraction reagent supplemented with complete protease inhibitor cocktail and benzonase nuclease. The resulting suspension was centrifuged, and the cleared lysate was subjected to chromatography on Ni-Sepharose column HisTrap HP. Bound proteins were eluted using a linear gradient of imidazole (25–500 mmol/L) and analyzed by SDS–PAGE. Fractions containing 15N-hMTH1 were after dialysis loaded onto a MonoQ anion-exchange column and eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl. Eluted fractions were analyzed using SDS–PAGE with Coomassie staining. Fractions containing 15N-hMTH1 protein were pooled and stored in 20 mmol/L HEPES, 225 mmol/L NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 1 mmol/L Tris (2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine hydrochloride at −80° C The purity of the isolated 15N-hMTH1 was checked using SDS–PAGE with Coomassie staining. Figure 5 illustrates the SDS–PAGE analysis of 15N-hMTH1 along with hMTH1 and protein standards, indicating high purity of both proteins (Coskun et al., 2015).

Figure 5.

SDS–PAGE analysis of purified hMTH1 and 15N-hMTH1. Lane 1, hMTH1; lane 2, 15N-hMTH1; and lane 3, molecular mass markers. Data from Coskun et al. (2015).

8. MASS SPECTROMETRIC ANALYSIS OF 15N-LABELED PROTEINS

Mass spectrometry was used to measure the molecular masses and to check the isotopic purities of 15N-labeled DNA repair proteins that were produced as described above. MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry was applied to measure the molecular masses of E. coli 15N-Fpg and 15N-hOGG1 (Reddy et al., 2011). The protonated average molecular mass (MH+) of E. coli 15N-Fpg amounts to 30641 Da, as calculated using the NIST Mass and Fragment Calculator. The measurement yielded a value of 30442 Da. It is well known that the N-terminal Met is removed from proteins by peptide deformylase and methionineaminopeptidase as an essential process, when the penultimate residue is small and uncharged as Pro next to Met (Giglione, Boularot, & Meinnel, 2004). Without the N-terminal Met, the calculated value of the MH+ of E. coli 15N-Fpg amounted to 30509 Da. The measured value (30442 Da) is 99.8% of this calculated value. Using the same approach, the MH+ of His-tagged 15N-hOGG1 was found to be 41834 Da. The His-tag had a sequence of MGSSHHHHHHSSGLVPRGSHEL. The calculated MH+ of this protein amounts to 41688 Da, which is 99.7% of the measured value. The measured MH+ of His (KLAAALEHHHHHH)-tagged 15N-hNEIL1 amounted to 45833 Da (unpublished results). The calculated MH+ of this protein was 45785 Da, which is 99.9% of the measured value. Considering that the MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry provides a mass accuracy of 0.1%, these values represent more than 99% 15N-labeling of E. coli Fpg, hOGG1, and hNEIL1 proteins.

An Orbitrap mass spectrometer coupled to an HPLC system, which has a mass accuracy of 0.001%, was used to measure the molecular mass of 15N-hAPE1 (Kirkali et al., 2013). The calculated MH+ of 15N-hAPE1 with the loss of Met amounts to 35858 Da. The measured MH+ was 35854 Da, which differs by 4 Da only from the calculated value and thus represents a 99.99% labeling. Within the mass accuracy of the Orbitrap mass spectrometer, this result showed that a complete 15N-labeling of hAPE1 was achieved.

The molecular mass of 15N-hMTH1 was measured using a high-resolution QToF mass spectrometer coupled to an HPLC system (Coskun et al., 2015). Without the N-terminal Met, the calculated MH+ of 15N-hMTH1 amounts to 20229.8 Da. The measured MH+ of 15N-hMTH1 was 20216.2 Da, which is 99.93% of the calculated value. Taken together, the measurement of the average molecular masses of the produced full-length 15N-labeled proteins confirmed their identity and an almost complete 15N-labeling, meaning that these labeled proteins can be used as excellent internal standards for the measurement of DNA repair proteins by LC-MS/MS or any other MS technique.

9. APPLICATIONS TO THE MEASUREMENT OF DNA REPAIR PROTEINS

9.1 Development of Methodologies

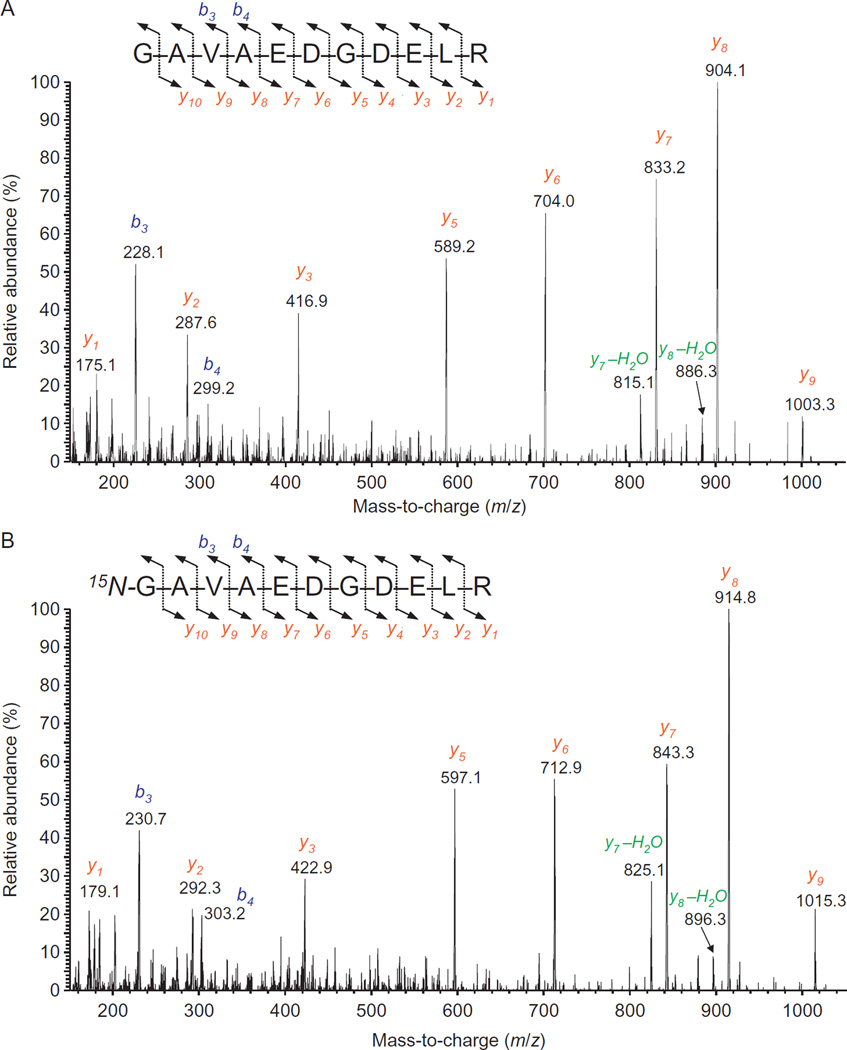

Following production of 15N-labeled DNA repair proteins, we developed methodologies using these proteins as internal standards to positively identify and accurately quantify corresponding DNA repair proteins in human cultured cells and tissues with the use of LC-MS/MS. For this purpose, 15N-labeled proteins and their unlabeled analogs were hydrolyzed with trypsin and then analyzed by LC-MS/MS. A number of tryptic peptides of each protein were identified on the basis of their full-scan mass spectra and product ion spectra. Identified tryptic peptides yielded protein scores of more than 100 with the use of the “Mascot” search engine (http://www.matrixscience.com), according to which protein scores greater than 70 are considered significant (p<0.05) for positive identification. Moreover, using to the SwissProt database (http://prospector.ucsf.edu/prospector/cgi-bin/mssearch.cgi) and the taxonomy Homo sapiens (20,200 sequences), several combinations of only four out of many identified tryptic peptides provided a 100% match with studied proteins. This means that the simultaneous measurement of just four tryptic peptides would be sufficient to positively identify and quantify a target protein. As an example of full-scan mass spectra, Fig. 6 illustrates the mass spectrum of one of the tryptic peptides of hAPE1 and its 15N-labeled analog (Kirkali et al., 2013). In general, mass spectra of such peptides contain an MH+ ion of lower abundance (ion at m/z 1131 in Fig. 6) and a doubly protonated (charged) molecular ion [(M+2H)2+] as the most abundant ion (m/z 566.1 in Fig. 6) (Kinter & Sherman, 2000). The mass spectrum of the 15N-labeled peptide exhibited a shift of 14 Da in the mass of MH+ of the unlabeled peptide, consistent with the fourteen 15N atoms in the molecule. The shift in the mass of (M+2H)2+ was also in agreement with the mass difference of 14 Da. To obtain product ion spectra, optimum collision energies using (M+2H)2+ ions as the precursor ions were measured (Coskun et al., 2015; Reddy et al., 2013). These were in agreement with previously determined collision energies of peptides with similar masses (Kinter & Sherman, 2000). Product ion spectra of identified tryptic peptides were recorded using the determined collision energy for each peptide. As examples, product ion spectra of the peptides in Fig. 6 are illustrated in Fig. 7 (Kirkali et al., 2013). Such spectra are generally dominated by so-called γ-series ions with b-series ions being of lesser intensity (Kinter & Sherman, 2000). In Fig. 7A, typical γ-ions from the γ1-ion to the γ9-ion, with the most intense ion being the γ8-ion at m/z 904, are seen with only a few b-ions. The 15N-labeled analog gave an essentially identical spectrum with mass shifts according to the 15N-content of the fragments (Fig. 7B). The observed masses of all γ-series ions and b-series ions in product ion spectra of analyzed tryptic peptides perfectly matched the corresponding theoretical masses calculated using NIST Mass and Fragment Calculator (www.nist.gov/mml/bmd/bioanalytical/massfragcalc.cfm).

Figure 6.

Full-scan mass spectra of the tryptic peptides GAVAEDGDELR (A) and 15N-GAVAEDGDELR (B). Data from Kirkali et al. (2013).

Figure 7.

Product ion spectra of GAVAEDGDELR (A) and 15N-GAVAEDGDELR (B). The (M+2H)2+ ions m/z 566.3 (A) and m/z 573.3 (B) were used as the precursor ions. The insert shows the fragmentation pathways leading to the b- and y-ions. Data from Kirkali et al. (2013).

Selected reaction monitoring (SRM) was used to analyze trypsin hydro-lysates of proteins and their 15N-labeled analogs to establish the sensitive and accurate measurement of proteins in vivo. Mass transitions from (M+2H)2+ to the most intense γ-ion in product ion spectra were used. Ion-current profiles of the mass transitions of tryptic peptides exhibited excellent peak shapes and a baseline separation between peptides. As expected, each tryptic peptide and its respective 15N-labeled analog coeluted at the same retention time (Coskun et al., 2015; Dizdaroglu et al., 2011; Kirkali et al., 2013; Reddy et al., 2013). To further ascertain the identity of a target peptide, multiple typical transitions were simultaneously monitored. All typical transitions of tryptic peptides lined up at their appropriate retention times, confirming their identity. The analytical sensitivity of the LC-MS/MS instrument was measured. Depending on the peptide, the on-column limit of detection varied from 10 to 20 fmol with a signal-to-noise ratio of at least 3, whereas the limit of quantification was approximately 50–100 fmol of target peptide with a signal-to-noise ratio of 10.

9.2 Measurement of DNA Repair Proteins In Vivo

hAPE1 has been positively identified and quantified in nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts of three human cell lines and in mouse liver (Kirkali et al., 2013), and in human cancerous and disease-free breast tissues (unpublished data). Different expression levels of hAPE1 were observed depending of the cell line and tissue types. As an example, Fig. 8 illustrates ion-current profiles of mass transitions of five tryptic peptides of hAPE1 and 15N-hAPE1 obtained using the tryptic digest of a nuclear extract of human mammary gland epithelial adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) cells. The signals of five peptides of hAPE1 and 15N-hAPE1, which was added to protein extracts as an internal standard, lined up at the corresponding retention times, unequivocally identifying hAPE1 in this human cell line. The expression levels of hAPE1 in cell lines and tissues were calculated by using the measured signals of mass transitions of each tryptic peptide and their 15N-labeled analogs, the amount of the internal standard, and the protein amount in each protein extract. In addition, we demonstrated the detection of APE1 variants with single amino acid replacements, i.e., Gln51His and Gly241Arg, which occur in several cancers (Pieretti, Khattar, & Smith, 2001), and in the general population (Hadi, Coleman, Fidelis, Mohrenweiser, & Wilson, 2000; Mohrenweiser, Xi, Vazquez-Matias, & Jones, 2002).

Figure 8.

Ion-current profiles of mass transitions of five tryptic peptides of hAPE1 and 15N-hAPE1 obtained using the tryptic digest of a nuclear extract of MCF-7 cells. The extract was spiked with an aliquot of 15N-hAPE1 prior to separation by HPLC. Data from Kirkali et al. (2013).

hMTH1 has been unequivocally identified and quantified in human malignant and disease-free breast tissues and in four cultured human cell lines (Coskun et al., 2015). Extreme expression of MTH1 in malignant breast tumors was observed, suggesting that cancer cells are addicted to MTH1 for their survival. In agreement with this finding, cultured MCF-7 cells exhibited a much greater expression level of hMTH1 than their normal counterpart mammary gland epithelial (MCF-10A) cells.

10. CONCLUSIONS

In this chapter, we described the production and purification of full-length 15N-labeled DNA proteins to be used as internal standards for the measurement of DNA repair proteins in human tissues in vivo by LC-MS/MS or by other mass spectrometric techniques. These internal standards are absolutely essential for positive identification and accurate quantification of target proteins. The use of these labeled proteins has been demonstrated for the measurement of several DNA repair proteins in human tissues and cultured cells. Such measurements will be of fundamental importance for the determination of DNA repair capacity, the use of DNA repair proteins as biomarkers, and the development of DNA repair inhibitors in cancer, and eventually in other diseases as well.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Dimitry Zharkov (SB RAS Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine, Novosibirsk, Russia) for providing the ogg1 gene in the expression vector of pET15b for the production of 15N-hOGG1, and to Dr. Timothy R. O’Connor (Beckman Institute of the City of Hope, Duarte, CA) for the gift of the coding sequence for E. coli fpg gene from the plasmid pFpg for production of E. coli 15N-Fpg. E. coli BL21 (λDE3) harboring pETApe recombinant of plasmid for the production of 15N-hAPE1 was kindly provided by Dr. David M. Wilson III (National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA). The human neil1 gene in the expression vector pET22b for the production of 15N-hNEIL1 was a gift from Dr. Stephen Lloyd (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR). This work on MTH1 protein was supported by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (T.H.), Swedish Research Council (T.H.), Swedish Cancer Society (T.H.), the Swedish Pain Relief Foundation (T.H.), the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (T.H.), the Göran Gustafsson Foundation, and the Torsten and Ragnar Söderberg Foundation (T.H.).

Certain commercial equipment or materials are identified in this chapter in order to specify adequately the experimental procedure. Such identification does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor does it imply that the materials or equipment identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

Contributor Information

Prasad T. Reddy, Email: prasad.reddy@nist.gov.

Miral Dizdaroglu, Email: miral@nist.gov.

REFERENCES

- Abbotts R, Madhusudan S. Human AP endonuclease 1 (APE1): From mechanistic insights to druggable target in cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2010;36:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinwall R, Rothwell DG, Roldan-Arjona T, Anselmino C, Ward CJ, Cheadle JP, et al. Cloning and characterization of a functional human homo-log of Escherichia coli endonuclease III. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:109–114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audebert M, Radicella JP, Dizdaroglu M. Effect of single mutations in the OGG1 gene found in human tumors on the substrate specificity of the ogg1 protein. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28:2672–2678. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.14.2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandaru V, Sunkara S, Wallace SS, Bond JP. A novel human DNA gly-cosylase that removes oxidative DNA damage and is homologous to Escherichia coli endonuclease VIII. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 2002;1:517–529. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes T, Kim WC, Mantha AK, Kim SE, Izumi T, Mitra S, et al. Identification of Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) as the endoribonuclease that cleaves c-myc mRNA. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37:3946–3958. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard WA, Wilson SH. Structural design of a eukaryotic DNA repair polymerase: DNA polymerase beta. Mutation Research. 2000;460:231–244. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(00)00029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard WA, Wilson SH. Structure and mechanism of DNA polymerase beta. Chemical Reviews. 2006;106:361–382. doi: 10.1021/cr0404904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard WA, Wilson SH. Structure and mechanism of DNA polymerase beta. Biochemistry. 2014;53:2768–2780. doi: 10.1021/bi500139h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman RA, Loeb LA. Genetic instability in cancer: Theory and experiment. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2005;15:423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boiteux S, Gajewski E, Laval J, Dizdaroglu M. Substrate specificity of the Escherichia coli Fpg protein (formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase): Excision of purine lesions in DNA produced by ionizing radiation or photosensitization. Biochemistry. 1992;31:106–110. doi: 10.1021/bi00116a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite DK, Ito J. Compilation, alignment, and phylogenetic relationships of DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Research. 1993;21:787–802. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.4.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabelof DC. Haploinsufficiency in mouse models of DNA repair deficiency: Modifiers of penetrance. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2012;69:727–740. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0839-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan N, Bristow RG. “Contextual” synthetic lethality and/or loss of heterozygosity: Tumor hypoxia and modification of DNA repair. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16:4553–4560. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MK, Ocampo-Hafalla MT, Vartanian V, Jaruga P, Kirkali G, Koenig KL, et al. Targeted deletion of the genes encoding NTH1 and NEIL1 DNA N-glycosylases reveals the existence of novel carcinogenic oxidative damage to DNA. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 2009;8:786–794. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun E, Jaruga P, Jemth AS, Loseva O, Scanlan LD, Tona A, et al. Addiction to MTH1 protein results in intense expression in human breast cancer tissue as measured by liquid chromatography-isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.05.008. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin NJ. PARP and PARP inhibitor therapeutics. In: Madhusudan S, Wilson DM III, editors. DNA repair and cancer from bench to clinic. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2013. pp. 513–563. [Google Scholar]

- Demple B, Harrison L. Repair of oxidative damage to DNA: Enzymology and biology. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1994;63:915–948. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.004411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demple B, Herman T, Chen DS. Cloning and expression of APE, the cDNA encoding the major human apurinic endonuclease: Definition of a family of DNA repair enzymes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88:11450–11454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dherin C, Radicella JP, Dizdaroglu M, Boiteux S. Excision of oxidatively damaged DNA bases by the human alpha-hOgg1 protein and the polymorphic alpha-hOgg1 (Ser326Cys) protein which is frequently found in human populations. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27:4001–4007. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.20.4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizdaroglu M. Base-excision repair of oxidative DNA damage by DNA glycosylases. Mutation Research. 2005;591:45–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizdaroglu M. Oxidatively induced DNA damage and its repair in cancer. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research. 2015;763:212–245. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizdaroglu M, Jaruga P. Mechanisms of free radical-induced damage to DNA. Free Radical Research. 2012;46:382–419. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.653969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dizdaroglu M, Reddy PT, Jaruga P. Identification and quantification of DNA repair proteins by liquid chromatography/isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry using their fully 15N–labeled analogues as internal standards. Journal of Proteome Research. 2011;10:3802–3813. doi: 10.1021/pr200269j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doublie S, Bandaru V, Bond JP, Wallace SS. The crystal structure of human endonuclease VIII-like 1 (NEIL1) reveals a zincless finger motif required for glycosylase activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:10284–10289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402051101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Cooke MS. Oxidative DNA damage and disease: Induction, repair and significance. Mutation Research. 2004;567:1–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishel ML, Vascotto C, Kelley MR. DNA base excision repair therapeutics: Summary of targets with a focus on APE1. In: Madhusudan S, Wilson DM III, editors. DNA repair and cancer from bench to clinic. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2013. pp. 233–287. [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T. DNA repair and mutagenesis. 2nd. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gad H, Koolmeister T, Jemth AS, Eshtad S, Jacques SA, Strom CE, et al. MTH1 inhibition eradicates cancer by preventing sanitation of the dNTP pool. Nature. 2014;508:215–221. doi: 10.1038/nature13181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglione C, Boularot A, Meinnel T. Protein N-terminal methionine excision. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences: CMLS. 2004;61:1455–1474. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-3466-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros L, Ishchenko AA, Ide H, Elder RH, Saparbaev MK. The major human AP endonuclease (Ape1) is involved in the nucleotide incision repair pathway. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32:73–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros L, Saparbaev MK, Laval J. Enzymology of the repair of free radicals-induced DNA damage. Oncogene. 2002;21:8905–8925. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadi MZ, Coleman MA, Fidelis K, Mohrenweiser HW, Wilson DM., III Functional characterization of Ape1 variants identified in the human population. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28:3871–3879. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.20.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakem R. DNA-damage repair; the good, the bad, and the ugly. The EMBO Journal. 2008;27:589–605. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazra TK, Izumi T, Boldogh I, Imhoff B, Kow YW, Jaruga P, et al. Identification and characterization of a human DNA glycosylase for repair of modified bases in oxidatively damaged DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:3523–3528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062053799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde ML, Hazra TK, Mitra S. Early steps in the DNA base excision/single-strand interruption repair pathway in mammalian cells. Cell Research. 2008;18:27–47. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleday T. Amplifying tumour-specific replication lesions by DNA repair inhibitors—A new era in targeted cancer therapy. European Journal of Cancer. 2008;44:921–927. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleday T, Petermann E, Lundin C, Hodgson B, Sharma RA. DNA repair pathways as targets for cancer therapy. Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2008;8:193–204. doi: 10.1038/nrc2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeijmakers JH. Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature. 2001;411:366–374. doi: 10.1038/35077232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, de Souza-Pinto NC, Haraguchi K, Hogue BA, Jaruga P, Greenberg MM, et al. Repair of formamidopyrimidines in DNA involves different glycosylases: Role of the OGG1, NTH1, and NEIL1 enzymes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:40544–40551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508772200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huamani J, McMahan CA, Herbert DC, Reddick R, McCarrey JR, MacInnes MI, et al. Spontaneous mutagenesis is enhanced in Apex heterozygous mice. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2004;24:8145–8153. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8145-8153.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber KV, Salah E, Radic B, Gridling M, Elkins JM, Stukalov A, et al. Stereospecific targeting of MTH1 by (S)-crizotinib as an anticancer strategy. Nature. 2014;508:222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature13194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illuzzi JL, Wilson DM., III Base excision repair: Contribution to tumorigenesis and target in anticancer treatment paradigms. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2012;19:3922–3936. doi: 10.2174/092986712802002581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaruga P, Birincioglu M, Rosenquist TA, Dizdaroglu M. Mouse NEIL1 protein is specific for excision of 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine and 4,6-diamino-5-formamidopyrimidine from oxidatively damaged DNA. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15909–15914. doi: 10.1021/bi048162l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaruga P, Xiao Y, Vartanian V, Lloyd RS, Dizdaroglu M. Evidence for the involvement of DNA repair enzyme NEIL1 in nucleotide excision repair of (5′R)- and (5′ S)-8,5′-cyclo-2′-deoxyadenosines. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1053–1055. doi: 10.1021/bi902161f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karahalil B, Roldan-Arjona T, Dizdaroglu M. Substrate specificity of Schizosaccharomyces pombe Nth protein for products of oxidative DNA damage. Biochemistry. 1998;37:590–595. doi: 10.1021/bi971660s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley MR. Future directions with DNA repair inhibitors: A roadmap for disruptive approaches to cancer therapy. In: Kelley MR, editor. Molecular targets and clinical applications. DNA repair in cancer therapy. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CH, Cueto R, Belinsky SA, Lechner JF, Pryor WA. Over-expression of hMTH1 mRNA: A molecular marker of oxidative stress in lung cancer cells. FEBS Letters. 1998;429:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00505-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinter M, Sherman NE. Protein sequencing and identification using tandem mass spectrometry. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkali G, Jaruga P, Reddy PT, Tona A, Nelson BC, Li M, et al. Identification and quantification of DNA repair protein apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) in human cells by liquid chromatography/isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Bandaru V, Bond JP, Jaruga P, Zhao X, Christov PP, et al. The mouse ortholog of NEIL3 is a functional DNA glycosylase in vitro and in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:4925–4930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908307107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Yin LH, Pu YP. Reduced expression of human DNA repair genes in esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma in china. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. Part A. 2007;70:956–963. doi: 10.1080/15287390701290725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb LA. Human cancers express mutator phenotypes: Origin, consequences and targeting. Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2011;11:450–457. doi: 10.1038/nrc3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudan S, Middleton MR. The emerging role of DNA repair proteins as predictive, prognostic and therapeutic targets in cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2005;31:603–617. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki H, Sekiguchi M. MutT protein specifically hydrolyses a potent mutagenic substrate for DNA synthesis. Nature. 1992;355:273–275. doi: 10.1038/355273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto Y, Kim K. Excision of deoxyribose phosphate residues by DNA polymerase β during DNA repair. Science. 1995;269:699–702. doi: 10.1126/science.7624801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meira LB, Devaraj S, Kisby GE, Burns DK, Daniel RL, Hammer RE, et al. Heterozygosity for the mouse Apex gene results in phenotypes associated with oxidative stress. Cancer Research. 2001;61:5552–5557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Mo JY, Maki H, Sekiguchi M. Hydrolytic elimination of a mutagenic nucleotide, 8-oxodGTP, by human 18-kilodalton protein: Sanitization of nucleotide pool. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:11021–11025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.11021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller BJ, Arap W, Pasqualini R. Targeting synthetic lethality in DNA damage repair pathways as an anti-cancer strategy. Current Drug Targets. 2010;11:1336–1340. doi: 10.2174/1389450111007011336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrenweiser HW, Xi T, Vazquez-Matias J, Jones IM. Identification of 127 amino acid substitution variants in screening 37 DNA repair genes in humans. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2002;11:1054–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muftuoglu M, de Souza-Pinto NC, Dogan A, Aamann M, Stevnsner T, Rybanska I, et al. Cockayne syndrome group B protein stimulates repair of formamidopyrimidines by NEIL1 DNA glycosylase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:9270–9279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807006200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TR, Boiteux S, Laval J. Repair of imidazole ring-opened purines in DNA: Overproduction of the formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase of Escherichia coli using plasmids containing the fpg+gene. Annali dell’Istituto Superiore di Sanità. 1989;25:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K, Toyokuni S, Kim WJ, Ogawa O, Kakehi Y, Arao S, et al. Overexpression of human mutT homologue gene messenger RNA in renal-cell carcinoma: Evidence of persistent oxidative stress in cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 1996;65:437–441. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960208)65:4<437::AID-IJC7>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry C, Sultana R, Madhusudan S. Personalized cancer medicine: DNA repair alterations are promising predictive biomarkers in cancer targets Molecular applications clinical. In: Kelley MR, editor. lDNA repair in cancer therapy. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 257–282. [Google Scholar]

- Pieretti M, Khattar NH, Smith SA. Common polymorphisms and somatic mutations in human base excision repair genes in ovarian and endometrial cancers. Mutation Research. 2001;432:53–59. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5726(00)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy PT, Jaruga P, Kirkali G, Tuna G, Nelson BC, Dizdaroglu M. Identification and quantification of human DNA repair protein NEIL1 by liquid chromatography/isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Proteome Research. 2013;12:1049–1061. doi: 10.1021/pr301037t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy PT, Jaruga P, Nelson BC, Lowenthal M, Dizdaroglu M. Stable isotope-labeling of DNA repair proteins, and their purification and characterization. Protein Expression and Purification. 2011;78:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roldán-Arjona T, Anselmino C, Lindahl T. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of a Schizosaccharomyces pombe homologue of Escherichia coli endonuclease III. Nucleic Acids Research. 1996;24:3307–3312. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.17.3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist TA, Zaika E, Fernandes AS, Zharkov DO, Miller H, Grollman AP. The novel DNA glycosylase, NEIL1, protects mammalian cells from radiation-mediated cell death. DNA Repair (Amsterdam) 2003;2:581–591. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy LM, Jaruga P, Wood TG, McCullough AK, Dizdaroglu M, Lloyd RS. Human polymorphic variants of the NEIL1 DNA glycosylase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:15790–15798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y, Furuichi M, Takahashi M, Mishima M, Iwai S, Shirakawa M, et al. A molecular basis for the selective recognition of 2-hydroxy-dATP and 8-oxo-dGTP by human MTH1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:8579–8587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110566200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakumi K, Furuichi M, Tsuzuki T, Kakuma T, Kawabata S, Maki H, et al. Cloning and expression of cDNA for a human enzyme that hydrolyzes 8-oxo-dGTP, a mutagenic substrate for DNA synthesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:23524–23530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. 2nd. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sampath H, McCullough AK, Lloyd RS. Regulation of DNA glycosylases and their role in limiting disease. Free Radical Research. 2012;46:460–478. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2012.655730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi M, Tsuzuki T. Oxidative nucleotide damage: Consequences and prevention. Oncogene. 2002;21:8895–8904. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidorenko VS, Grollman AP, Jaruga P, Dizdaroglu M, Zharkov DO. Substrate specificity and excision kinetics of natural polymorphic variants and phosphomimetic mutants of human 8-oxoguanine-DNA glycosylase. The FEBS Journal. 2009;276:5149–5162. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speina E, Arczewska KD, Gackowski D, Zielinska M, Siomek A, Kowalewski J, et al. Contribution of hMTH1 to the maintenance of 8-oxoguanine levels in lung DNA of non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97:384–395. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava DK, Berg BJ, Prasad R, Molina JT, Beard WA, Tomkinson AE, et al. Mammalian abasic site base excision repair. Identification of the reaction sequence and rate-determining steps. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:21203–21209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson LM, Jemth AS, Desroses M, Loseva O, Helleday T, Hogbom M, et al. Crystal structure of human MTH1 and the 8-oxo-dGMP product complex. FEBS Letters. 2011;585:2617–2621. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tell G, Quadrifoglio F, Tiribelli C, Kelley MR. The many functions of APE1/Ref-1: Not only a DNA repair enzyme. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2009;11:601–620. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuzuki T, Egashira A, Igarashi H, Iwakuma T, Nakatsuru Y, Tominaga Y, et al. Spontaneous tumorigenesis in mice defective in the MTH1 gene encoding 8-oxo-dGTPase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:11456–11461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191086798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian V, Lowell B, Minko IG, Wood TG, Ceci JD, George S, et al. The metabolic syndrome resulting from a knockout of the NEIL1 DNA glycosylase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:1864–1869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507444103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace SS, Murphy DL, Sweasy JB. Base excision repair and cancer. Cancer Letters. 2012;327:73–89. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DM, III, Barsky D. The major human abasic endonuclease: Formation, consequences and repair of abasic lesions in DNA. Mutation Research. 2001;485:283–307. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DM, III, Kim D, Berquist BR, Sigurdson AJ. Variation in base excision repair capacity. Mutation Research. 2011;711:100–112. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RD, Mitchell M, Lindahl T. Human DNA repair genes. Mutation Research. 2005;577:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthoudakis S, Curran T. Identification and characterization of Ref-1, a nuclear protein that facilitates AP-1 DNA-binding activity. The EMBO Journal. 1992;11:653–665. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthoudakis S, Smeyne RJ, Wallace JD, Curran T. The redox/DNA repair protein, Ref-1, is essential for early embryonic development in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:8919–8923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]