CONSPECTUS

Many fundamental processes of life depend on the chemical energy stored in the O–O bond of dioxygen (O2), the majority of which is derived from photosynthetic H2O oxidation. Key steps in these processes involve Mn-, Fe-, or Cu-promoted formation or cleavage of O–O and O–H bonds, the mechanisms of which are not fully understood, especially with Mn. Metal–peroxo and high-valent metal–oxo species are proposed to be involved as intermediates. The metal ion properties that favor O–O and O–H bond formation versus cleavage have yet to be systematically explored. Herein we examine the O2 reactivity of a series of structurally related Mn(II) complexes and show that several metastable intermediates are observed, the relative stabilities of which depend on subtle differences in ligand architecture. We show that in contrast to Fe and Cu complexes, O2 binds irreversibly to Mn(II). By crystallizing an entire series of the first reported examples of Mn(III)–OOR peroxos as well as an O2-derived binuclear trans-μ-1,2-bridged Mn(III)–peroxo with varying degrees of O–O bond activation, we demonstrate that there are distinct correlations between spectroscopic, structural, and reactivity properties. Rate-limiting O–O bond cleavage is shown to afford a reactive species capable of abstracting H atoms from 2,4-tBu2-PhOH or 1,4-cyclohexadiene, depending on the ligand substituents. The weakly coordinated N-heterocycle Mn⋯Npy,quino distance is shown to correlate with the peroxo O–O bond length and modulate the π overlap between the filled and Mn dxz orbitals. We also show that there is a strong correlation between the peroxo → Mn charge transfer (CT) band and the peroxo O–O bond length. The energy difference between the CT bands associated with the peroxos possessing the shortest and longest O–O bonds shows that these distances are spectroscopically distinguishable. We show that we can use this spectroscopic parameter to estimate the O–O bond length, and thus the degree of O–O bond activation, in intermediates for which there is no crystal structure, as long as the ligand environment is approximately the same.

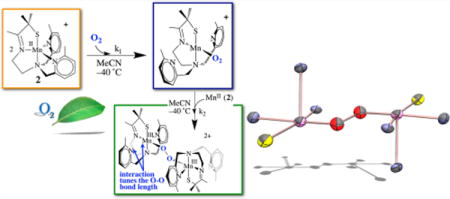

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

The energy stored in the O–O bond of O2 sustains aerobic life by driving essential metabolic and biosynthetic pathways, including DNA synthesis and repair1 and the biosynthesis of neurotransmitters2 and hormones.2 Manganese-, iron-, and copper-containing enzymes catalyze the majority of these reactions.2–8 Although O2-mediated oxidation reactions are thermodynamically favored, they are spin-forbidden and thus kinetically slow unless promoted by a transition-metal ion.9 Most of the O2 on our planet is generated via Mn-promoted H2O splitting.4,10,11 The formation and/or cleavage of O–O and O–H bonds represent key steps in dioxygen activation, substrate oxidation, and H2O splitting, the mechanisms of which are not fully understood. Metal–peroxo and high-valent metal–oxo species are proposed to be involved as intermediates.4–8,12,13 The formation of strong MO–H bonds provides a driving force for the latter to abstract H atoms from strong X–H bonds (X = C, N, O).14,15 Thiolates (RS−) have been shown to facilitate O2 activation16 via the formation of highly covalent M(III)–SR bonds17 and to facilitate hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) reactions14 by increasing the metal–oxo basicity.15 Understanding the metal ion properties that favor O–H and O–O bond formation versus cleavage should facilitate the development of catalysts tailored to promote C–H activation or H2O splitting.

MANGANESE DIOXYGEN CHEMISTRY

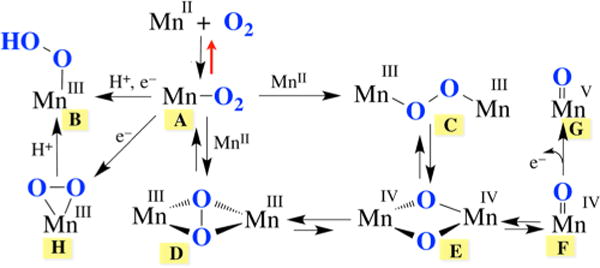

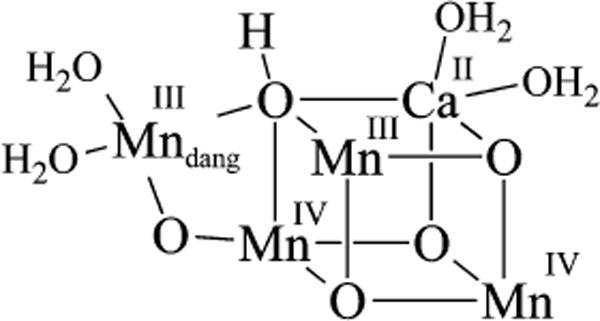

In contrast to iron and copper dioxygen chemistry,2,3,5,7,8,13,15 manganese dioxygen chemistry remains relatively unexplored,12,18–21 and the spectroscopic properties of key superoxo and peroxo intermediates have yet to be elucidated. Establishing benchmark spectroscopic parameters will allow key enzymatic intermediates to be more readily identified, thereby providing mechanistic details that are currently unavailable. Potential Mn–dioxygen activation pathways, based in part on those established for Fe and Cu, are shown in Figure 1. These involve superoxo (A), hydroperoxo (B), and peroxo (end-on (C) or side-on (D and H)) intermediates as well as high-valent Mn(IV)–oxo (binuclear (E) or mononuclear (F)) and Mn(V)–oxo22 (G) intermediates. A number of groups have paved the way in terms of our understanding of the properties and reactivity of Mn(IV)– and Mn(V)–oxo compounds.22–28 High-valent Mn–oxos are typically considered to be more potent oxidants than peroxo or superoxo species and are proposed to form following heterolytic (B → Mn(V)≡O + H2O) or homolytic (C → E or D → E) O–O bond cleavage (Figure 1). With Fe and Cu, peroxo O–O bond cleavage is facilitated either by protonation of the distal oxygen (B)9 or bridging the peroxo between two metal ions, ideally in an η2, η2-side-on fashion (D), so as to maximize overlap with the empty σ*(O–O) orbital.2,7 The reverse reaction sequence (Mn(V)≡O + M–OH (M = Mn, or Ca) or Mn–O• + Mn–O•) is proposed to be involved in the O–O bond-forming step of photosynthetic H2O splitting, catalyzed by the oxygen evolving complex (OEC), Mndang–CaMn3O4 (Figure 2).4,10,23,29 The dangling Mn (Mndang) has been implicated as a key player in this step. The metal ion properties that favor the forward versus reverse processes outlined in Figure 1 remain to be established.

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanism for dioxygen activation by Mn, based in part on established Fe and Cu pathways.

Figure 2.

Structure of the OEC in its S1 state.

Prior to our work,12,20,30,31 there were no characterized examples of non-heme Mn intermediates A, B, C, and D (Figure 1), although there were a handful of examples of deprotonated versions of B containing an η2-side-on peroxo (Figure 3).18,32–35 Only one of these is derived from O2, however.18 Although the O–O bond in η2-side-on Mn(III)–peroxo compounds is relatively unactivated in terms of O–O bond length, side-on peroxos have been shown to react with electrophilic aldehydes, presumably via nucleophilic attack by a “ring-opened” end-on Mn(III)–O–O− intermediate.18,32 Consistent with this possibility, an end-on Mn(III)–OOH species B was recently shown to form upon protonation of the η2-side-on Mn–peroxo compound shown in Figure 3, but it was not crystallographically characterized.36

Figure 3.

Representative example of a mononuclear η2-side-on Mn–peroxo.30

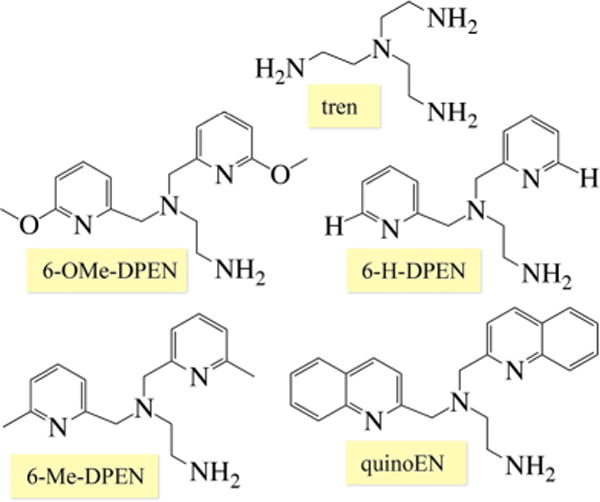

LIGAND DESIGN

By making systematic changes to a metal ion’s coordination sphere, one can determine how the reactivity and spectroscopic properties correlate with electronic and geometric structure of the metal ion. For the systems described herein, the ligand architecture was found to play an important role in determining both the kinetics and thermodynamics of Mn-promoted dioxygen activation (vide infra). Ligand scaffolds consisting of a thiolate (RS−) and either a primary amine or N-heterocycle were assembled via a Schiff base condensation between 3-methyl-3-mercapto-2-butanone and the tetradentate amine backbones depicted in Figure 4. A thiolate was incorporated (Figure 5) in order to promote O2 binding and facilitate the observation of metastable dioxygen intermediates.12 We have shown that the RS → M charge transfer (CT) bands of M–thiolate complexes provide a convenient spectroscopic handle for monitoring the formation of intermediates (e.g., [FeIII(SMe2N4(tren))(OOH)]+),12,17,37–39 and the reduction of small molecules (e.g., O2, O2−•, NO2−, NO).12,37,38,40 and Upon oxidation, the metal-centered orbitals drop in energy closer to the sulfur orbitals of π symmetry, causing the RS → M CT band to shift from the UV to the visible region.17 This also increases the M–SR bond covalency, providing a driving force for RS–M(III)–O2•− formation from RS–M(II) + O2 and lowering the activation barrier to O2 binding.16 We found that with Mn, the thiolate’s contributions to the electronic spectral properties turn out to be especially important because in contrast to Cu and Fe, the peroxo → M CT band falls in the UV as opposed to the visible region of the spectrum.2,5,30 N-heterocycles were incorporated into our ligand design because they are easily derivatized, allowing us to readily tune the electronic and steric properties of the corresponding manganese complexes (Figure 5). Substituents at the 6-position were varied from R = H, Me, or OMe to a fused phenyl ring (i.e., quinoline), and the number of methylene units (CH2)n connecting the tertiary amine to the imine was varied from n = 2 to 3. Subtle differences in the ligand scaffold were found to significantly affect the O2 reactivity41 and our ability to observe metastable intermediates, illustrating the importance of judicious ligand design and modification.

Figure 4.

Tetradentate amine ligand backbones used to construct reactive Mn(II) complexes.

Figure 5.

Series of thiolate-ligated Mn(II) complexes shown to react with O2.

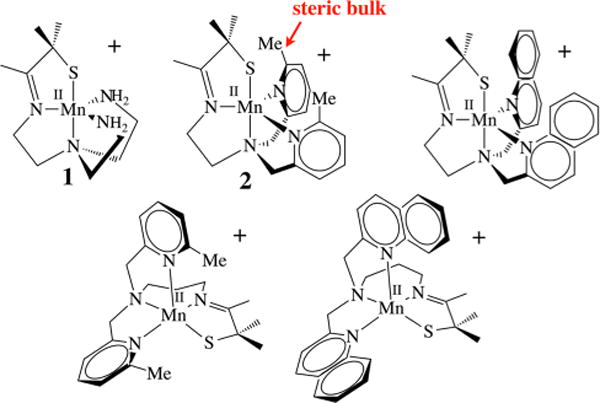

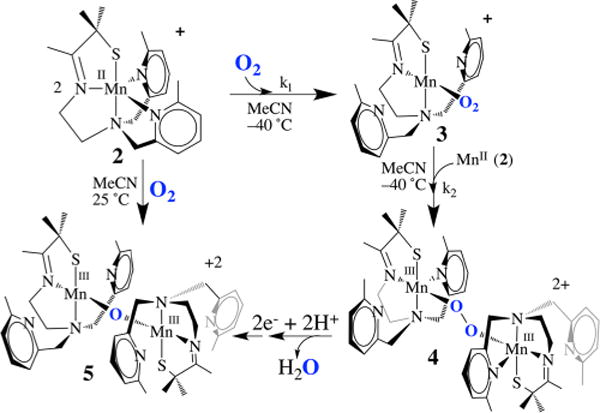

DIOXYGEN ACTIVATION BY SYNTHETIC MN(II) COMPLEXES

At ambient temperatures, all of the Mn(II) complexes pictured in Figure 5 were shown to react with O2 to form relatively stable binuclear Mn(III) complexes containing a single oxo atom bridge in high yields (96–98%).12,41 At low temperatures, metastable dioxygen intermediates are observed,12,19 but only if steric bulk is incorporated into the ligand backbone. The N-heterocycle substituent was found to dramatically influence both the relative and overall stabilities of Mn–dioxygen intermediates. With primary amines (tren, 1)41 or with an R = H substituent at the 6-position of the pyridine (6-H-DPEN, Figure 4), no dioxygen intermediates are observed, even at temperatures as low as −78 °C. With a Me substituent at the 6-position, on the other hand, the reduced five-coordinate complex [MnII(SMe2N4(6-MeDPEN))]+ (2) was shown to react with 1 equiv of O2 at low T (Figure 6) to irreversibly form the dioxygen intermediate [Mn(SMe2N4(6-MeDPEN))(O2)]+ (3), observable by stopped-flow (λmax = 515 nm, k1(−10 °C) = 3780 M−1 s−1, , ),12 which then more slowly converts to the metastable green intermediate {[MnIII(SMe2N4(6-MeDPEN)]2(μ-O2)}2+(4) (λmax = 640(830) nm, k2(−10 °C) = 417 M−1 s−1, , ). Binding of dioxygen to 2 is relatively slow compared with binding to Cu(I) complexes.3,7 Metastable 4 slowly converts (~4 h at −40 °C) to the purple mono-oxo-bridged product {[MnIII(SMe2N4(6-MeDPEN)]2(μ-O)}2+ (5) (λmax = 560 nm) in high yields (97−99%). The oxo atom in 5 (Figure 6) is derived from O2, as shown by 18O2 labeling studies. This would be consistent with O–O bond cleavage occurring along the reaction pathway.

Figure 6.

Reaction of five-coordinate 2 with O2 to afford mono-oxo-bridged 5 via metastable Mn-O2 intermediate 3 and Mn–peroxo intermediate 4.

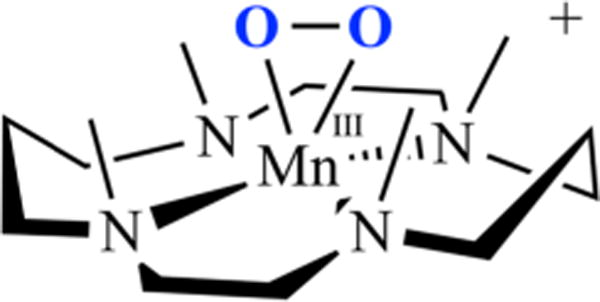

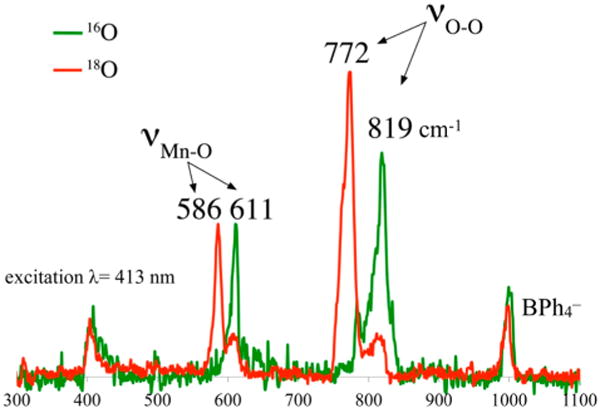

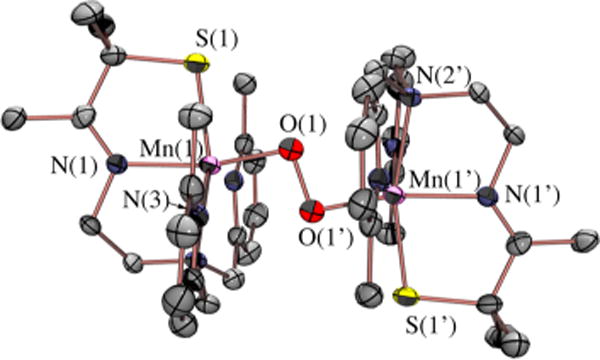

CHARACTERIZATION OF A MN–PEROXO INTERMEDIATE DERIVED FROM O2

Intermediate 4 (Figure 6) was found to release H2O2 upon protonation and to display isotopically sensitive stretches in the resonance Raman (rR) spectrum (νO–O(Δ18O) = 819(47) cm−1, νMn–O(Δ18O) = 611(25) cm−1; Figure 7), consistent with a peroxo.12 This assignment was ultimately verified by X-ray crystallography, which showed two Mn3+ ions bridged by a peroxo in an end-on trans-μ-1,2 fashion (Figure 8).12 The two electrons required to convert O2to O22− are derived from the two Mn2+ ions required to form 4. Overall, the kinetics of peroxo 4 formation show a second-order dependence on Mn(II) and a first-order dependence on O2·12 Consistent with two-electron reduction of O2, the O–O bond in 4 (1.452(5) Å) is significantly longer than that in O=O (1.21 Å) and close to that in reduced peroxide O–O2− (1.49 Å). The coexistence of a thiolate (a reductant) and a peroxide (an oxidant) in the same molecule is quite remarkable and perhaps suggests that the bridging peroxo is not a particularly strong oxidant. Compared with the peroxo O–O bonds of the more predominant mononuclear η2-side-on Mn(III)–peroxo complexes (Figure 3), with lengths in the range 1.403(4)–1.428(7) Å,32–35 that of 4 is noticeably longer. It is, however, comparable to those of lower-resolution cis-μ-1,2-peroxo-bridged Mn(IV) dimer (1.46(3) Å),21 and cis-μ-1,2-peroxo-bridged trinuclear (1.6(1) Å)42 structures, indicating that the bridging mode is responsible for the longer O–O bond. The isotopically sensitive νO–O stretching frequency of 4 is the lowest reported for a Mn–peroxo,18,34 consistent with its long O–O bond length and unique bridging mode.

Figure 7.

Resonance Raman spectrum of peroxo intermediate 4 (16O (green) vs 18O (red)).

Figure 8.

ORTEP diagram of O2-derived peroxo intermediate 4.

Peroxo-bridged 4 was not only the first well-defined example of a trans-μ-1,2-end-on Mn(III)–peroxo but also the first Mn–peroxo to be characterized by resonance Raman spectroscopy.12 The electronic absorption spectrum of 4 displays two bands, one at λmax = 387(1200) nm and the other at λmax = 640(830) nm. Resonance enhancement of the isotopically sensitive νO–O and νMn–O stretches in Figure 7 is observed only with laser frequencies near the UV, leading us to conclude that the higher-energy band at 387 nm rather than the lower-energy band at 640 nm corresponds to the CT band. This is in contrast to Fe–peroxo species, which have intense peroxo-to-metal CT bands in the visible region (500–700 nm),5,8,37 and may be one of the reasons there are no other reported rR-characterized Mn–peroxo species, except for recently reported Mn(III)–OOH.36

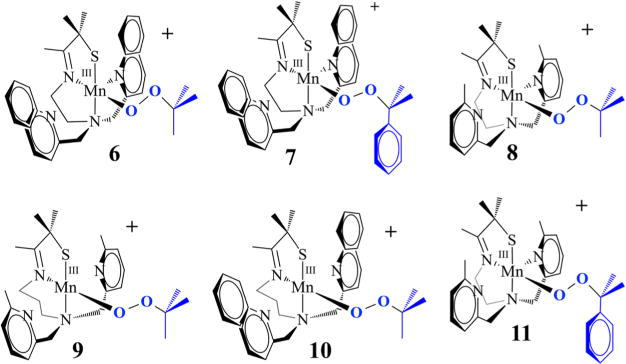

OBSERVED CORRELATION BETWEEN STRUCTURE AND SPECTROSCOPIC PROPERTIES OF MN–PEROXO COMPOUNDS

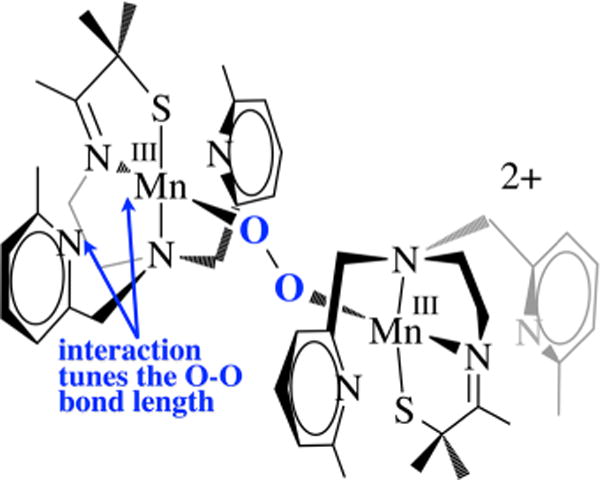

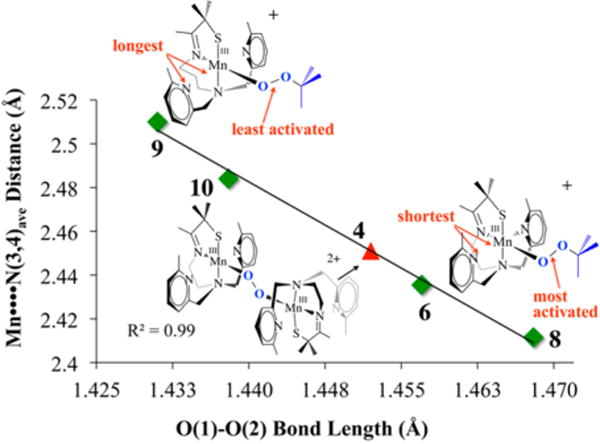

An unusual structural feature of peroxo-bridged 4, which turns out to play a key role in our ability to observe this metastable dioxygen intermediate, is the weakly coordinated pyridines (Figure 9). The Mn⋯Npy distances in 4 (2.410(3) and 2.492(3) Å) are well outside the typical range (2.17–2.25 Å) and significantly longer than the sum of their covalent radii (2.105 Å). Similarly long distances are observed in mono-oxo-bridged 5. Space-filling models indicate that steric interactions between the 6-methylpyridine substituent and the gem-dimethyl group adjacent to the sulfur are likely responsible for the long Mn⋯Npy distances. Although Jahn–Teller-like distortions possibly contribute to the elongation of these bonds, the Mn–Npy bonds in the less sterically congested 6-H-DPEN (Figure 4)-ligated Mn(III) oxo-bridged species are significantly shorter (2.223(5) and 2.243(5) Å), indicating that steric interactions play an important role. Peroxo 4 can therefore technically be described as a coordinatively unsaturated molecule. We observe similarly long Mn⋯Npy,quino “bonds” (2.349(7)–2.522(8) Å) in the series of structurally characterized metastable alkylperoxo Mn(III)–OOR (R = tBu, CMe2Ph) compounds 6–11 (Figure 10), the first reported examples of this type.30,31 Not only is it rare for one to be able to crystallize a first-row transition-metal peroxo, but to do so with a series of structurally related molecules (selected examples are shown in Figure 11) is extraordinarily rare, if not unprecedented. Thus, we were provided with an opportunity to look for correlations between key properties that are likely to influence O–O bond cleavage and formation. Strong correlations between structural, spectroscopic, and kinetic parameters were in fact observed.30 For example, the peroxo O–O bond length was shown to be inversely correlated with the Mn⋯Npy,quino distance (Figure 12). The O–O bond was found to elongate as the N-heterocycle moves closer to the Mn ion. Parameters for O2-derived peroxo 4 also fall on this line (red triangle in Figure 12). An extrapolation of this line to include a Mn–Npy distance of 2.23 or 2.31 Å would predict that the peroxo compounds containing the unsubstituted pyridine (6-H-DPEN) and primary amine (tren) ligands (Figure 4) would have O–O bond lengths of 1.55 and 1.51 Å, respectively, which would be significantly longer than the O–O bond of free peroxide O22− (1.49 Å). This extrapolation assumes that, as observed with the other peroxo/oxo compounds described above, the (unobserved) peroxo intermediate and the final mono-oxo-bridged Mn(III)–oxo possess similar Mn–Npy distances.41 This explains why we were unable to observe peroxo intermediates with the less sterically encumbered ligands. Extrapolation of this line to ≥2.8 Å (i.e., removal of the pyridines) would result in a significantly shorter O–O bond (≤1.32 Å). The “dangling” pyridines provide a potential H+ relay site that could be used either to facilitate heterolytic O–O bond cleavage or deprotonation of a coordinated H2O.

Figure 9.

The N-heterocycle influences the peroxo O–O bond length in all of the peroxo compounds examined in this series, including 4, even though they are well outside the typical bonding range.

Figure 10.

Series of structurally related metastable Mn(III)–OOR complexes.

Figure 11.

ORTEP diagrams of crystallized metastable Mn(III)–OOR complexes (representative examples).

Figure 12.

Correlation between the Mn⋯Npy,quino distance and the peroxo O–O bond length in Mn(III)–OOR compounds and O2− derived 4.

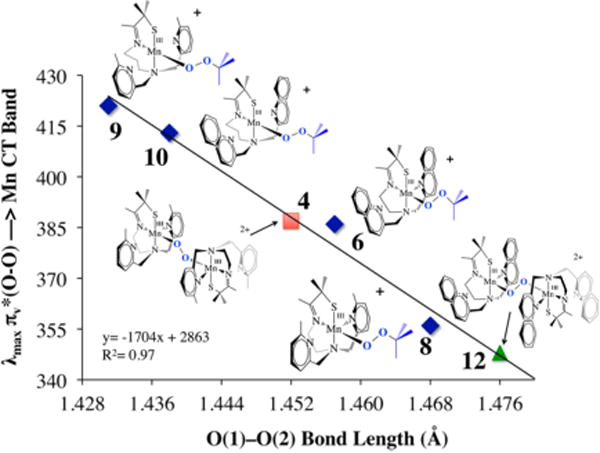

The data described above demonstrate that the N-heterocycle has a profound effect on the degree of O–O bond activation observed in our peroxo complexes, even when they lie well outside the expected bonding range. A density functional theory (DFT)-generated bonding picture30 for the alkylperoxo Mn(III)–OOtBu complex 9 (Figure 11) shows that the Mn⋯Npy interaction modulates the π overlap between the filled peroxo orbital and the Mn dxz orbital by altering the metal ion Lewis acidity: the Mulliken charge density was shown to increase (from +0.42 to +0.50) as the Mn⋯Npy,quino distance increases.30 As the metal ion Lewis acidity increases, the d manifold drops in energy toward the peroxo oxygen orbitals, thereby increasing σ(Mn–Operoxo) and π(Mn–Operoxo) bonding interactions. An increased π interaction shifts electron density out of the filled antibonding peroxo orbital into the Mn–Operoxo bonding region, resulting in a shorter, stronger peroxo O–O bond and ultimately an isolable Mn–peroxo.30 If the d orbitals drop in energy toward the peroxo orbitals, this would predict that the energy of the peroxo → M CT band should decrease as the Mn⋯Npy,quino separation increases and the O–O bond length decreases. This is in fact what we observe. The electronic absorption spectra of the intense-blue Mn–peroxo compounds 6–11 described above display two bands (as shown for 8 in Figure 13), one of which tracks with the O–O bond length. As shown in Figure 14, the energy of the band in the near-UV region of the spectrum (e.g., λmax = 356 nm in Figure 13) decreases as the O–O bond length decreases. Parameters for O2-derived peroxo 4 also fall on this line (red square in Figure 14). The energy difference (~70 nm) between the CT bands for the complexes with the shortest and longest peroxo O–O bonds shows that these distances are spectroscopically distinguishable. We can therefore use this spectroscopic parameter to estimate the O–O bond length, and thus the degree of O–O bond activation, in related Mn(III)–peroxo intermediates for which there is no crystal structure. This would of course require that the ligand environment be roughly the same. For example, although we have not been able to grow high-quality crystals of an O2-derived quinolone–Mn–peroxo intermediate (green triangle in Figure 14), we can estimate its O–O bond length using the experimentally determined peroxo → Mn CT band energy (λmax = 348 nm) and the linear fit to the data. The long O–O bond estimated in this manner (1.476 Å) is consistent with the significantly shorter lifetime of the quinoline peroxo (t1/2(233 K) = 47 s; k = 0.0149 s−1) relative to 4 (t1/2(233 K) ≈ 45 min).19

Figure 13.

Electronic absorption spectrum of metastable Mn(III)–OOR complex 8 (R = tBu).

Figure 14.

Correlation between the peroxo → Mn(III) CT band energy and the peroxo O–O bond length.

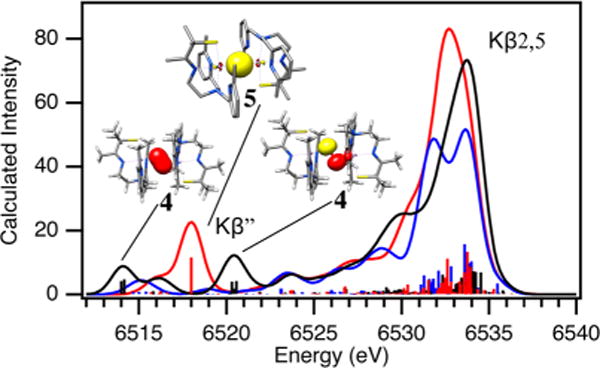

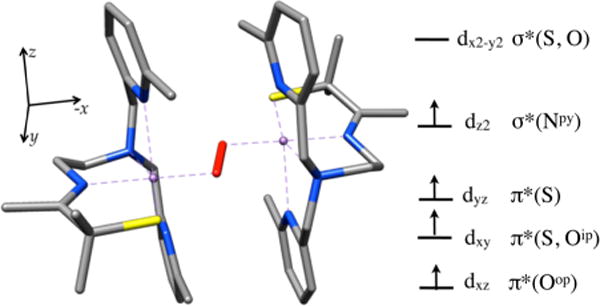

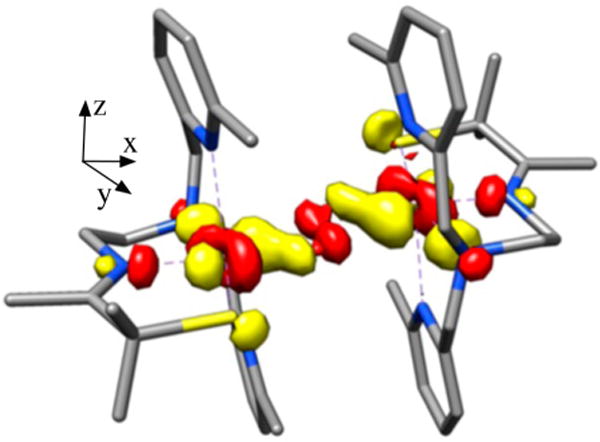

In collaboration with the DeBeer group, Kβ X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) was pursued in order to examine factors favoring O–O bond activation in O2-derived 4 and to provide a molecular orbital (MO) picture of the bonding.20 X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) involves the promotion of a metal ion 1s electron into either discrete orbitals (the pre-edge) or the continuum. XES involves the relaxation of a metal 3p electron (the Kβ1,3 and Kβ′ mainline region) or a ligand-based 2s or 2p electron (the Kβ″ and Kβ2,5 valence-to-core (VtC) region) into the 1s hole. This method has been used successfully to quantify N2 activation in Fe–N2 complexes.43 We are interested in obtaining benchmark parameters and looking for correlations between key emission features and O–O bond lengths in Mn–peroxo compounds. As shown in Figure 15, fits to the XES spectrum of peroxo-bridged 4 (black) show two features in the region 6514–6521 eV20 that are not present in the spectrum of the Mn(II) precursor 2 (blue) and lie above and below that involving the O 2s orbital of oxo-bridged 5 (red). These features correspond to emission from the peroxo σ2s(O–O) and orbitals, the separation of which reflects the peroxo O–O bond strength. DFT-calculated fits to the experimental XES data were used to generate a bonding picture of 4 (Figure 16),20 which shows that the thiolate and peroxo ligands dominate the ligand field, resulting in an empty orbital and leaving the pyridine nitrogens pointing toward the half-occupied orbital, thereby providing a mechanism for modulating the metal ion Lewis acidity. Pseudo-σ overlap between the thiolate sulfur, half-occupied Mn dxy, and peroxo orbitals (Figure 17) provides an additional mechanism for elongating the peroxo O–O bond.20 On the basis of the above structural, theoretical, and spectroscopic data, it is tempting to suggest that the eventual O–O bond cleavage that occurs with these metastable peroxos results from vibrational compression along the Mn–Npy,quino vectors. The thiolate also plays an important role in promoting O–O bond cleavage via a “push” mechanism20 much like that proposed to be involved in the cysS-promoted O–O bond cleavage step of P450.

Figure 15.

XES spectrum of O2-derived peroxo intermediate 4 (black) vs those of oxo-bridged 5 (red) and Mn(II) 2 (blue).

Figure 16.

HOMO/LUMO region of the DFT-calculated MO diagram of peroxo-bridged 4.

Figure 17.

DFT-calculated MO involving overlap between the peroxo , Mn dxy, and thiolate sulfur orbitals of peroxo-bridged 4.

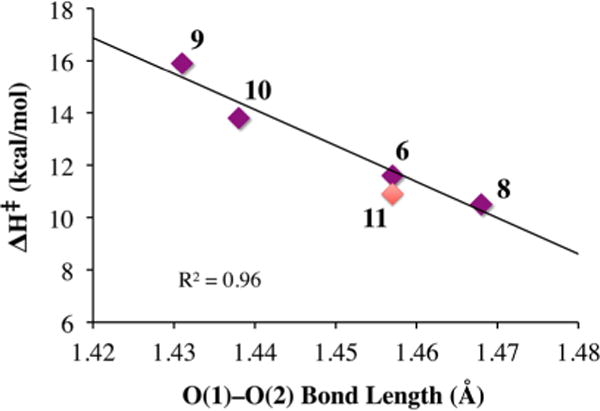

CORRELATION BETWEEN REACTIVITY AND STRUCTURAL AND SPECTROSCOPIC PROPERTIES

Rate-limiting peroxo O–O bond cleavage constitutes the mechanism of decay of our metastable Mn(III)–OOR compounds (Figure 10), as shown by the strong correlation between the enthalpy of activation (ΔH‡) and the peroxo O–O bond length (Figure 18).30 The Mn⋯Npy,quino interaction plays an integral role. The value of ΔH‡ progressively decreases (from 15.9 to 10.4 kcal/mol) as the average Mn⋯Npy,quino distance decreases (from 2.51 to 2.41 Å).30 The exclusive formation of acetophenone (72% yield) as opposed to cumenol upon warming cumenyl (Cm) peroxo derivatives 7 and 11 (Figure 10) provides evidence for homolytic as opposed to heterolytic O–O bond cleavage.31 The rate constants were found to be insensitive to the presence of electrophilic or nucleophilic organic substrates. The formation of Et2POtBu (24%) + Et3PO (31%) upon warming of Mn(III)–OOtBu derivatives 6 and 8–10 in the presence of PEt3 is also consistent with homolytic as opposed to heterolytic O–O bond cleavage.31 The formation of Et3PO implies that a Mn(IV)–oxo intermediate is involved.

Figure 18.

Correlation between ΔH‡ and the peroxo O–O bond length of Mn(III)–OOR (R = tBu (purple), Cm (red)) complexes.

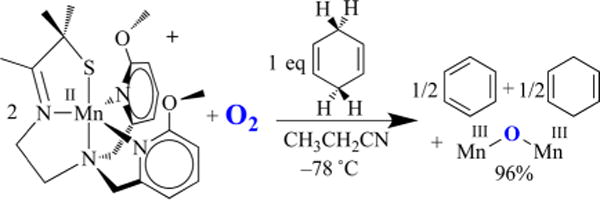

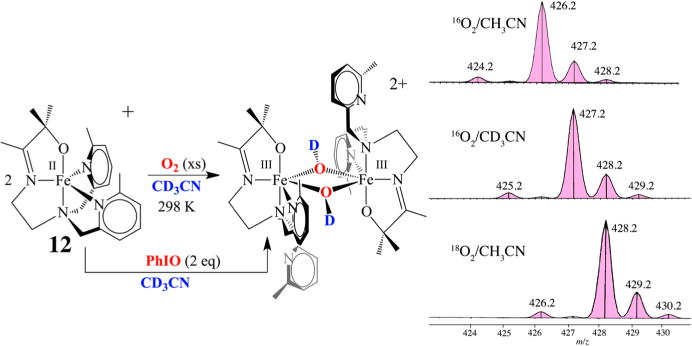

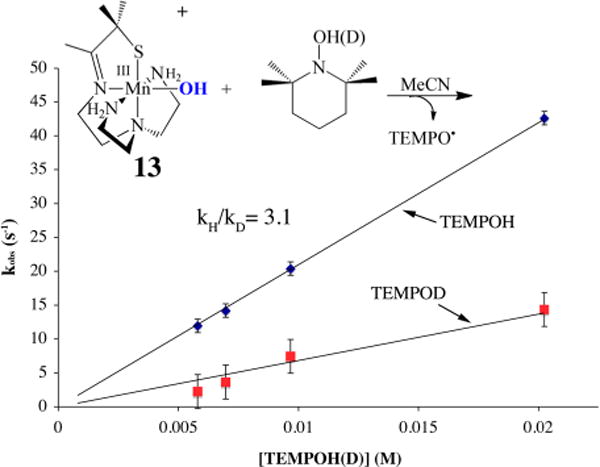

In order to convert dioxygen-derived peroxo-bridged 4 to mono-oxo-bridged 5, two electrons and at least one or likely two protons are required (Figure 6). The fate of the second O atom and the source of additional reducing equivalents (2e− + 2H+) remain to be determined. We suspect that a high-valent Mn–oxo intermediate, formed during the course of the reaction, abstracts H atoms from the solvent. However, to date we have only circumstantial evidence19,44 to support this. The reproducibly observed high yield of 5 rules out Mn2+ or sacrificial ligand as a source of H atoms or electrons, respectively. External substrates (PPh3, 2,4-tBu2-PhOH) are oxidized by Mn(II) 2 + O2 and serve as an electron (or e− + H+) source.19 However, the rate of peroxo 4 decay is not affected by added external substrates, indicating that the reactive species responsible for the observed oxidation chemistry forms following rate-limiting O–O bond cleavage, much like the Mn(III)–OOR compounds described above.19 This suggests that the peroxo itself is not very reactive. As revealed by space-filling models, this may in part be due to the inaccessibility of the peroxo, which is flanked by four π-stacked aromatic rings.12 With PPh3, 15 turnovers are achieved with almost no degradation of the catalyst. With 2,4-tBu2-PhOH, mono-oxo-bridged 5 forms in addition to the oxidized biphenol product (52% yield).19 The second oxygen is most likely lost as H2O via the condensation of two Mn(III)–OH intermediates. Isotopically labeled 18O is incorporated into the oxo bridge of 5 when H218O is added to 2 + 16O2, also supporting the involvement of a Mn(IV)=O intermediate. No label is incorporated when H218O is added to 5 alone as a control.19 The less sterically encumbered, more electron-rich 6-OMe-DPEN-ligated derivative of 2, shown in Figure 19, converts 1,4-cyclohexadiene (CHD) to benzene.19 In the absence of an external H atom donor, it is possible that MeCN solvent, or some impurity therein, serves as a H atom (e− + H+) source. Evidence to support this possibility is provided by results showing that deuterium from CD3CN is incorporated into the bis(μ-OD)-bridged product formed upon the addition of O2 (or PhIO) to [FeII(OMe2N4(6-MeDPEN))]+ (12) (Figure 20).44 On the basis of the MeCN C–H bond dissociation free energy (BDFE) of 97 kcal/mol,14 this would require a potent oxidant. With a coordinated thiolate (or possibly an alkoxide), one would expect a Mn(IV)=O species to be highly reactive, much like the RS•+–Fe(IV)=O of P450. In fact, we found that even the reduced, protonated, thiolate-ligated Mn(III)–OH complex [MnIII(SMe2N4(tren))(OH)]+ (13) can abstract H atoms, albeit from weak X–H bonds such as that in TEMPOH (O–H BDFE = 66.5 kcal/mol; Figure 21).45 This is despite the fact that 13 is an extremely mild oxidant (E1/2 = −300 mV vs Cp2Fe+/0 in MeCN). The reactive species 13 can be aerobically regenerated in H2O, and at least 10 turnovers can be achieved with almost no degradation of the “catalyst”.45 Hydroxo-bound 13 is the only water-soluble Mn(III)–OH complex shown to promote HAT. Consistent with this reactivity, 13 displays proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) in H2O, and from the linear correlation between its redox potential and the pH we were able to calculate an aqueous O–H BDFE of 74.0(5) kcal/mol for the product [MnII(SMe2N4(tren))(H2O)]+ (14). From this we could estimate the O–H BDFE for 14 in MeCN (70.1 kcal/mol) and calculate its pKa as 21.2.45 The thiolate was shown to increase the basicity of the hydroxo ligand, offsetting the low potential, thereby facilitating H atom abstraction.45 This work demonstrates that the O–H BDFE of H2O (122.7 kcal/mol) is decreased considerably (by 48.7 kcal/mol) upon binding to Mn2+,45 an observation relevant to the mechanism of photosynthetic H2O splitting.

Figure 19.

Reaction between O2 and the more electron-donating 6-OMe-DPEN-ligated Mn(II) complex in the presence of CHD affords benzene.

Figure 20.

Deuterium incorporation into the product of the reaction between O2 (or PhIO) and an alkoxide-ligated Fe(II) complex in CD3CN.

Figure 21.

Deuterium isotope effect demonstrating that reduced protonated Mn(III)–OH abstracts a hydrogen atom from TEMPOH-(D).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Dioxygen formation and its controlled activation for incorporation into organic molecules drive the chemistry of life as we know it. Key steps in these reactions involve transition-metal-promoted cleavage and/or formation of O–H and O–O bonds via metal–oxo and –peroxo intermediates, but we are far from understanding the mechanistic details, especially with Mn. By systematically altering the metal ion coordination sphere, we have shown that subtle differences in ligand architecture can significantly affect the relative stability of Mn–dioxygen intermediates and tune peroxo O–O bond lengths. By crystallizing an entire series of metastable Mn(III)–peroxo compounds with varying degrees of O–O bond activation, we have demonstrated that there are distinct correlations between spectroscopic, structural, and reactivity properties. Weakly coordinated N-heterocycles have been shown to be responsible for our ability to observe these peroxos and to cause the O–O bond length to vary as a function of Mn⋯Npy,quino distance by modulating the π overlap between the filled peroxo and Mn dxz orbitals. We have shown that there is a strong correlation between the peroxo → Mn CT band and the peroxo O–O bond length, and the energy difference between the CT bands for the complexes with the shortest and longest O–O bonds shows that these distances are spectroscopically distinguishable, indicating that we can use this spectroscopic parameter to predict an estimated O–O bond length, and thus the degree of O–O bond activation, in intermediates for which there is no crystal structure, as long as the ligand environment is roughly the same.

Of the proposed intermediates outlined in Figure 1, two have yet to be characterized: a binuclear bridging η2,η2-side-on Mn(III)–peroxo (D) and a well-defined Mn(III)–superoxo (A). We have shown that several metastable intermediates can be observed in the reaction between O2 and our coordinatively unsaturated Mn(II) complexes (Figure 5), including the first crystallographically characterized example of a binuclear trans-μ-1,2-peroxo-bridged Mn(III) intermediate (C), a Mn–O2 intermediate (A) (Figure 1), and a third intermediate (E or F) implicated via indirect (reactivity) evidence. Rate-limiting O–O bond cleavage affords a reactive species capable of abstracting H atoms from 2,4-tBu2-PhOH or 1,4-cyclohexadiene depending on the supporting ligand substituents. The observation of more than one intermediate is exceedingly rare in first-row transition-metal O2 chemistry outside of a protein environment.2,3,6,7 The instability of our Mn–O2 intermediate 3 did not allow us to determine whether it is best described as a Mn(III)–O2•− (superoxo) or Mn(II)–O2 species. Obtaining a well-defined Mn–superoxo would allow one to determine whether such a species is capable of abstracting H atoms and/or reductively eliminating O2 upon oxidation. We have shown that O2 binds irreversibly to our Mn(II) complex, which is in contrast to its behavior with Fe and Cu.3,12 It is possible that the thiolate ligand contributes to this irreversibility. However, as illustrated by OEC-promoted (Figure 1) biological O2 evolution,4 one would expect a higher oxidation state to be required in order for Mn to promote reductive elimination of O246 because the Mn(II) d orbitals lie higher in energy than those of Cu(I) or Fe(II) relative to oxygen.

The first steps of photosynthetic H2O splitting (S0 → S4)4,10,29 involve the endothermic cleavage of strong O–H bonds (122.7 kcal/mol) via PCET.14 We have shown that the O–H BDFE of H2O decreases considerably upon binding to Mn2+.45 Mechanistic details about the steps that follow, involving O–O bond formation and reductive elimination of O2 (S4→ S0), are unavailable.4,10,22,29 An unobserved Mn–peroxo species ,47 resembling our structurally characterized binuclear trans-μ-1,2-peroxo-bridged Mn complex 4, has been proposed to be involved as a key intermediate. However, the longer O–O bonds of binuclear Mn(III) peroxo-bridged 4 and related binuclear Mn(IV) peroxo-bridged species21 relative to those of mononuclear Mn(III)–peroxos indicate that dioxygen is more effectively activated when bridged between two Mn ions regardless of the oxidation state. This suggests that such a species is unlikely to be involved as an intermediate in photosynthetic O2 evolution, which would be consistent with the proposed involvement of the OEC Mndang and Ca2+ ions (Figure 2).4,10,22,29

Acknowledgments

J.A.K. is grateful to have had the privilege of working with a number of very talented graduate students who have contributed to the work described herein. The NIH is also gratefully acknowledged for its support (GM 45881).

Biography

Julie A. Kovacs is a Professor of Chemistry at the University of Washington in Seattle. She received her B.S. degree from Michigan State University (1981) and her Ph.D. from Harvard University (1986) and did her postdoctoral work at UC Berkeley. Her research focuses on characterizing metastable intermediates formed during transition-metal-promoted dioxygen activation and determining how thiolate ligands influence their properties.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Cotruvo JA, Jr, Stich TA, Britt RS, Stubbe J. Mechanism of Assembly of the Dimanganese-Tyrosyl Radical Cofactor of Class Ib Ribonucleotide Reductase: Enzymatic Generation of Superoxide Is Required for Tyrosine Oxidation via a Mn(III)Mn(IV) Intermediate. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:4027–4039. doi: 10.1021/ja312457t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon EI, Heppner DE, Johnston EM, Ginsbach JW, Cirera J, Qayyum M, Kieber-Emmons MT, Kjaergaard CH, Hadt RG, Tian L. Copper Active Sites in Biology. Chem Rev. 2014;114:3659–3853. doi: 10.1021/cr400327t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JY, Karlin KD. Elaboration of copper–oxygen mediated C–H activation chemistry in consideration of future fuel and feedstock generation. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2015;25:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yano J, Yachandra VK. Mn4Ca Cluster in Photosynthesis: Where and How Water is Oxidized to Dioxygen. Chem Rev. 2014;114:4175–4205. doi: 10.1021/cr4004874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tinberg CE, Lippard SJ. Dioxygen Activation in Soluble Methane Monooxygenase. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:280–288. doi: 10.1021/ar1001473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kovaleva EG, Neibergall MB, Chakrabarty S, Lipscomb JD. Finding Intermediates in the O2 Activation Pathways of Non-Heme Iron Oxygenases. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:475–483. doi: 10.1021/ar700052v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis EA, Tolman WB. Reactivity of dioxygen-copper systems. Chem Rev. 2004;104:1047–1076. doi: 10.1021/cr020633r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que LJ. Dioxygen Activation at Mononuclear Nonheme Iron Active Sites: Enzymes, Models, and Intermediates. Chem Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovacs JA. How Iron Activates O2. Science. 2003;299:1024–1025. doi: 10.1126/science.1081792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suga M, Akita F, Hirata K, Ueno G, Murakami H, Nakajima Y, Shimizu T, Yamashita K, Yamamoto M, Ago H, Shen J-R. Native structure of photosystem II at 1.95 Å resolution viewed by femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature. 2015;517:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature13991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young KJ, Brennan BJ, Tagore R, Brudvig GW. Photosynthetic Water Oxidation: Insights from Manganese Model Chemistry. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:567–574. doi: 10.1021/ar5004175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coggins MK, Sun X, Kwak Y, Solomon EI, Rybak-Akimova E, Kovacs JA. Characterization of Metastable Intermediates Formed in the Reaction Between a Mn(II) Complex and Dioxygen, Including a Crystallographic Structure of a Binuclear Mn(III)-Peroxo Species. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:5631–5640. doi: 10.1021/ja311166u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon EI, Wong SD, Liu LV, Decker A, Chow MS. Peroxo and oxo intermediates in mononuclear non-heme iron enzymes and related active sites. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren JJ, Tronic TA, Mayer JM. Thermochemistry of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reagents and its Implications. Chem Rev. 2010;110:6961–7001. doi: 10.1021/cr100085k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green MT. C–H bond activation in heme proteins: the role of thiolate ligation in cytochrome P450. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown CD, Neidig ML, Neibergall MB, Lipscomb JD, Solomon EI. VTVH-MCD and DFT Studies of Thiolate Bonding to {FeNO}7/{FeO2}8 Complexes of Isopenicillin N Synthase: Substrate Determination of Oxidase versus Oxygenase Activity in Nonheme Fe Enzymes. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7427–7438. doi: 10.1021/ja071364v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovacs JA, Brines LM. Understanding how the thiolate sulfur contributes to the function of the non-heme iron enzyme superoxide reductase. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:501–509. doi: 10.1021/ar600059h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shook RL, Gunderson WA, Greaves J, Ziller JW, Hendrich MP, Borovik AS. A Monomeric MnIII-Peroxo Complex Derived Directly from Dioxygen. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8888–8889. doi: 10.1021/ja802775e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johansen A, Rees JA, Hayes E, Coggins MK, Stoll S, Rybak-Akimova E, DeBeer S, Kovacs JA. Tuning the Ligand Environment To Favor Mn(II)-Promoted Dioxygen Activation and O-O Bond Cleavage. Manuscript in preparation [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rees JA, Martin-Diaconescu V, Kovacs JA, DeBeer S. X-ray Absorption and Emission Study of Dioxygen Activation by a Small-Molecule Manganese Complex. Inorg Chem. 2015;54:6410–6422. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bossek U, Weyhermüller T, Wieghardt K, Nuber B, Weiss J. [L2Mn2(μ-O)2(μ-O2)](ClO4): The First Binuclear(μ-Peroxo)-dimanganese(IV) Complex (L = 1,4,7Trimethyl-1,4,7triazacyclononane). A Model for the S4-S0 Transformation in the Oxygen Evolving Complex in Photosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6387–6388. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta R, Taguchi T, Lassalle-Kaiser B, Bominaar EL, Yano J, Hendrich MP, Borovik AS. High-spin Mn–oxo complexes and their relevance to the oxygen-evolving complex within photosystem II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:5319–5324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422800112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukherjee S, Stull JA, Yano J, Stamatatos TC, Pringouri K, Stich TA, Abboud KA, Britt RD, Yachandra VK, Christou G. Synthetic model of the asymmetric [Mn3CaO4] cubane core of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2257–2262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115290109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prokop KA, Goldberg DP. Generation of an Isolable, Monomeric Manganese(V)–Oxo Complex from O2 and Visible Light. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8014–8017. doi: 10.1021/ja300888t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin N, Ibrahim M, Spiro TG, Groves JT. Trans-dioxo Manganese(V) Porphyrins. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12416–12417. doi: 10.1021/ja0761737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pecoraro VL, Baldwin MJ, Gelasco A. Interaction of Manganese with Dioxygen and Its Reduced Derivatives. Chem Rev. 1994;94:807–826. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Limburg J, Vrettos JS, Liable-Sands LM, Rheingold AL, Crabtree RH, Brudvig GW. A Functional Model for O–O Bond Formation by the O2-Evolving Complex in Photosystem II. Science. 1999;283:1524–1527. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SH, Park H, Seo MS, Kubo M, Ogura T, Klajn J, Gryko DT, Valentine JS, Nam W. Reversible O–O Bond Cleavage and Formation between Mn(IV)-Peroxo and Mn(V)-Oxo Corroles. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14030–14032. doi: 10.1021/ja1066465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsui EY, Tran R, Yano J, Agapie T. Redox-inactive metals modulate the reduction potential in heterometallic manganese–oxido clusters. Nat Chem. 2013;5:293–299. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coggins MK, Martin-Diaconescu V, De Beer S, Kovacs JA. Correlation Between Structural, Spectroscopic, and Reactivity Properties Within a Series of Structurally Analogous Metastable Manganese(III)-Alkylperoxo Complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:4260–4272. doi: 10.1021/ja308915x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coggins MK, Kovacs JA. Structural and Spectroscopic Characterization of Metastable Thiolate-Ligated Manganese(III)-Alkylperoxo Species. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12470–12473. doi: 10.1021/ja205520u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seo MS, Kim JY, Annaraj J, Kim Y, Lee Y-M, Kim S-J, Kim J, Nam W. [Mn(tmc)(O2)]+: A Side-On Peroxido Manganese–(III) Complex Bearing a Non-Heme Ligand. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:377–380. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.VanAtta RB, Strouse CE, Hanson LK, Valentine JS. [Peroxotetraphenyl porphinato] manganese(III) and [Chlorotetraphenylporphinato]manganese(II) Anions. Syntheses, Crystal Structures, and Electronic Structures. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:1425–1434. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitajima N, Komatsuzaki H, Hikichi S, Osawa M, Morooka Y. A Monomeric Side-On Peroxo Manganese(III) Complex: Mn(O2)(3,5-iPr2pzH) (HB(3,5-iPr2pz)3) J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:11596–11597. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh UP, Sharma AK, Hikichi S, Komatsuzaki H, Morooka Y, Akita M. Hydrogen bonding interaction between imidazolyl N–H group and peroxide: Stabilization of Mn(III)-peroxo complexTpiPr2Mn(μ2-O2) (imMeH) (imMeH = 2-methylimidazole) Inorg Chim Acta. 2006;359:4407–4411. [Google Scholar]

- 36.So H, Park YJ, Cho K-B, Lee Y-M, Seo MS, Cho J, Sarangi R, Nam W. Spectroscopic Characterization and Reactivity Studies of a Mononuclear Nonheme Mn(III)–Hydroperoxo Complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:12229–12232. doi: 10.1021/ja506275q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shearer J, Scarrow RC, Kovacs JA. Synthetic models for the cysteinate–ligated Non–Heme Iron Enzyme Superoxide Reductase: Observation and Structural characterization by XAS of an FeIII–OOH Intermediate. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11709–11717. doi: 10.1021/ja012722b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitagawa T, Dey A, Lugo-Mas P, Benedict J, Kaminsky W, Solomon E, Kovacs JA. A Functional Model for the Metalloenzyme Superoxide Reductase. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14448–14449. doi: 10.1021/ja064870d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nam E, Alokolaro PE, Swartz RD, Gleaves MC, Pikul J, Kovacs JA. An Investigation of the Mechanism of Formation of a Thiolate-Ligated Fe(III)-OOH. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:1592–1602. doi: 10.1021/ic101776m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Villar-Acevedo G, Nam E, Fitch S, Benedict J, Freudenthal J, Kaminsky W, Kovacs JA. Influence of Thiolate Ligands on Reductive N–O Bond Activation. Oxidative Addition of NO to a Biomimetic SOR Analogue, and its Proton-Dependent Reduction of Nitrite. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1419–1427. doi: 10.1021/ja107551u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coggins MK, Toledo S, Shaffer E, Kaminsky W, Shearer J, Kovacs JA. Characterization and Dioxygen Reactivity of a New Series of Coordinatively Unsaturated Thiolate-Ligated Manganese(II) Complexes. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:6633–6644. doi: 10.1021/ic300192q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhula R, Gainsford GJ, Weatherburn DC. A New Model for the Oxygen-Evolving Complex in Photosynthesis. A Trinuclear μ3−Oxo Manganese(III) Complex Which Contains a μ-Peroxo Group. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:7550–7552. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pollock CJ, Grubel K, Holland PL, DeBeer S. Experimentally Quantifying Small-Molecule Bond Activation Using Valence-to-Core X-ray Emission Spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:11803–11808. doi: 10.1021/ja3116247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coggins MK, Toledo S, Kovacs JA. Isolation and Characterization of an Unsupported, Hydroxo-Bridged Iron(III, III)(μ-OH)2 Diamond Core Derived from Dioxygen. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:13325–13331. doi: 10.1021/ic4010906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coggins MK, Brines LM, Kovacs JA. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of a Series of Mn(III)-OR Complexes, Including a Water-Soluble Mn(III)-OH that Promotes Aerobic Hydrogen Atom Transfer. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:12383–12393. doi: 10.1021/ic401234t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Popp BV, Stahl SS. Oxidatively Induced” Reductive Elimination of Dioxygen from an η2 Peroxopalladium(II) Complex Promoted by Electron-Deficient Alkenes. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2804–2805. doi: 10.1021/ja057753b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haumann M, Muller C, Barra M, Grabolle M, Dau H. Photosynthetic O2 Formation Tracked by Time-Resolved X-ray Experiments. Science. 2005;310:1019–1021. doi: 10.1126/science.1117551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]