Abstract

Background and Purpose

Although dental hygienists are currently practicing within interprofessional teams in settings such as pediatric offices, hospitals, nursing homes, schools, and federally qualified health centers, they often still assume traditional responsibilities rather than practicing to the full extent of their training and licenses. This article explains the opportunity for the dental hygiene professional to embrace patient-centered care as an oral healthcare manager who can facilitate integration of oral and primary care in a variety of healthcare settings.

Methods

Based on an innovative model of collaboration between a college of dentistry and a college of nursing, an idea emerged among several faculty members for a new management method for realizing continuity and coordination of comprehensive patient care. Involved faculty members began working on the development of an approach to interprofessional practice with the dental hygienist serving as an oral healthcare manager who would address both oral healthcare and a patient’s related primary care issues through appropriate referrals and follow-up. This approach is explained in this article, along with the results of several pilot studies that begin to evaluate the feasibility of a dental hygienist as an oral healthcare manager.

Conclusion

A healthcare provider with management skills and leadership qualities is required to coordinate the interprofessional provision of comprehensive healthcare. The dental hygienist has the opportunity to lead closer integration of oral and primary care as an oral healthcare manager, by coordinating the team of providers needed to implement comprehensive, patient-centered care.

Keywords: oral healthcare, primary care, interprofessional core competencies, patient-centered care, dental hygienist, oral healthcare manager

Introduction

Interprofessional collaboration is an important component of dental hygiene practice. Yet dental hygiene professionals are not embracing this collaboration with the fervor needed to become leaders as primary oral healthcare providers and managers of patient-centered care. Other professionals, including nurses, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and teachers, are stepping up to provide oral health prevention and education and deliver services regarding oral-systemic disease. How long will it take until the dental hygiene profession realizes that it is strategically positioned to embrace the opportunity to address comprehensive oral healthcare needs in both the service provision as well as in oral healthcare management?

We came to this realization while having the good fortune to work within a college of dentistry that formerly administered a college of nursing. To our mutual advantage, many opportunities are available for both the college of dentistry and nursing to actively explore interprofessional education (IPE) through research and outreach activities. In our view, while ample IPE exists at the colleges, there is a need to provide evidence that would reveal the relationship between IPE and effective interprofessional practice or collaboration (IPC) between dental hygienists, dentists, other healthcare providers and educators. We became aware that the oral-systemic link that was well known within our distinct disciplinary perspective was gaining traction for other professions beyond dental hygiene. IPE and IPC aspects were being framed as when other healthcare providers identified oral concerns, the patient was referred to the dentist and not the dental hygienist. Often, these non-dental providers would assume responsibility for oral healthcare activities, except restorative dental needs that are generally referred to a dentist. These revelations intensified the need to embrace IPC, and explore the idea of the dental hygienist as the key oral healthcare manager within the interprofessional team, accessing input from and facilitating referrals to other professionals while coordinating a patient-centered approach to oral healthcare.

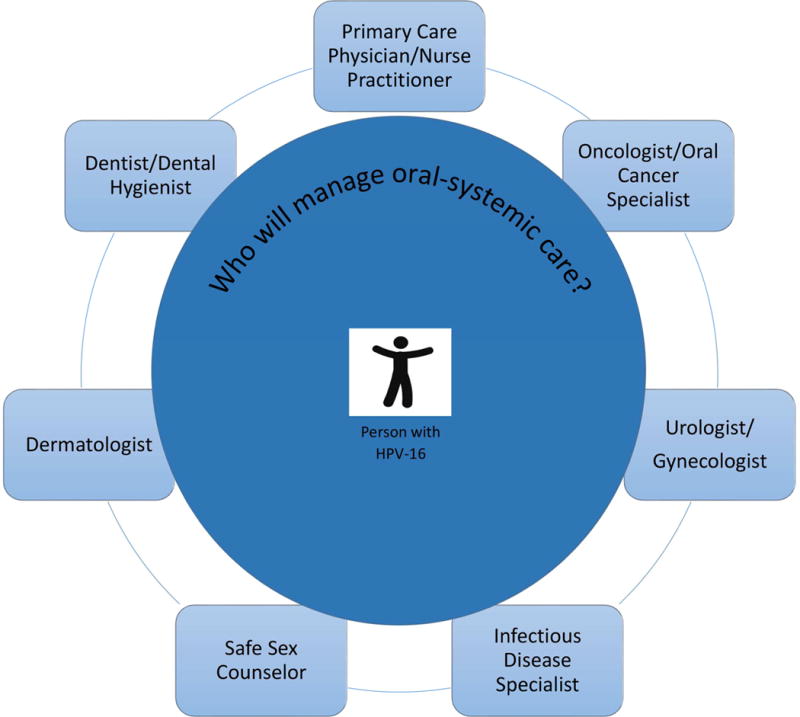

Consider this scenario. A patient arrives for a dental hygiene visit, regardless of location, and presents as HPV-16 positive. Who should coordinate the many aspects of delivering comprehensive patient-centered care and assessing the oral healthcare outcomes within an ongoing plan? Can this be the responsibility of the dental hygienist? Which team members should be consulted? What referrals are indicated? This is just one example of a condition requiring input from many healthcare disciplines. Diabetes, hypertension, tobacco use, obesity, opportunistic respiratory diseases, and caries risk reduction present additional scenarios that require interprofessional collaborative care. See Figure 1, which depicts the patient in the center wondering where to go for needed referrals, confused without someone to coordinate the care.

Figure 1. Coordination of patient-centered healthcare.

In this model, the patient is at the center of the healthcare system surrounded by primary care providers, specialists, and social service providers, but there is no designated professional to manage patient care. The providers listed are not intended to be comprehensive. Notably, the dental hygienist needed to coordinate care is missing.

A central question is, “How might the dental hygienist best contribute to and benefit from IPE and IPC?” This article presents a vision for the position of the dental hygienist as the IPC leader providing optimum delivery of whole person care.

Interprofessional care

More than a decade ago, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) examined quality and patient safety by health professionals and found these in need of improvement. The IOM published two seminal reports. To begin addressing quality and patient safety, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,1 called for care that is evidence-based, patient-centered, and systems-oriented. The follow-up report, Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality,2 focused on interprofessional care as one solution and suggested integrating a set of core competencies into health professions education. Specifically, it championed a future in which all health professionals, including but not limited to dental hygienists, nurses, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, would: (1) deliver patient-centered care; (2) be members of interprofessional teams; (3) emphasize evidence-based practice; and (4) use quality improvement approaches and informatics. Since 2003, limited but certain progress has been made in the creation of interprofessional core competencies. Yet a study done on interprofesional education in US dental hygiene programs indicates that there is still a lack of interprofessional education among potential partners.3

Patient-centered care

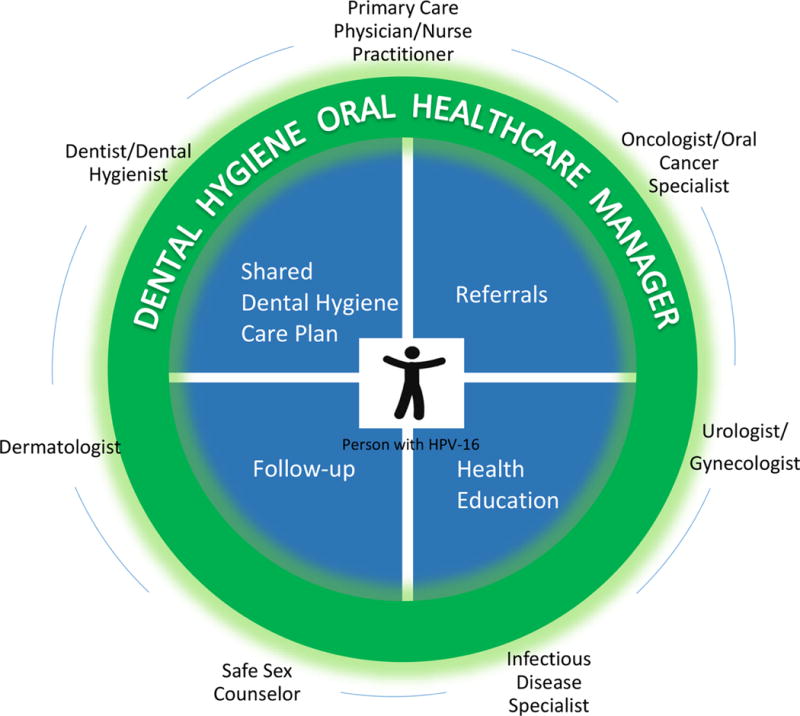

Patient-centered care is defined by the IOM as respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values that guide all clinical decisions.2 With multiple patient needs at the heart of healthcare practice, coordinated care is incumbent upon the collaboration between health professionals. The dental hygienist already has a broad scientific and patient-centered foundation of knowledge. With additional leadership skills and education and management training, the dental hygienist should be the point of contact for oral heathcare within collaborative, interprofessional teams. See Figure 2, which depicts the patient now in the center with the dental hygienist coordinating the referrals, health education, and follow-up care through a partnership with the patient in a shared care plan.

Figure 2. Dental hygienists as oral healthcare managers, coordinating patient-centered healthcare.

In this model which is more evolved than Figure 1 the patient is at the center of the healthcare system, and the dental hygienist acts as the oral healthcare manager, thereby ensuring that the shared dental hygiene care plan, referrals, health education, and follow-up care are enacted.

Patient-centered care has numerous applications to the practice of dental hygiene. Varying definitions of medical/dental/health homes4 and patient-centered care focus attention not only on the patient, but also on the family unit, and emphasize the accessibility and expertise of healthcare practitioners. The dental hygiene care plan also fully encompasses the individual’s psycho-bio-social issues, not merely the services delivered by the dental professional. That is, the whole person is the focus of care, which is the goal of a fully integrated interprofessional approach.

The dental hygiene care plan addresses health conditions, risk management, and the dental hygiene diagnosis, which is analogous to a nursing diagnosis. Clinical reasoning skills are employed to construct diagnostic statements, interventions, projected outcomes, and evaluation goals. This systems approach suggests the need for comprehensive preventive oral healthcare management.

When the dental hygienist manager develops the care plan, these referrals are incorporated into the plan and followed to the resulting outcomes. This contrasts with the traditional model where the dental hygienist after obtaining vital information advises the patient to visit another professional for hypertension screening or treatment, for example, or recommends that the patient seek counseling or treatment for tobacco cessation. The dental hygienist sets care objectives that address oral and general health concerns and incorporates the referrals to other professionals, thereby coordinating patient care as the primary oral healthcare manager. The frequency of visits with the dental hygienist supports close monitoring of oral-systemic care objectives and the status of the referrals and patient follow through on recommendations. In this evolved model, the dental hygienist remains linked to the patient during all aspects of care, coordinating efforts as they relate to oral healthcare (see Figure 2).

Participation of dental hygienists in interprofessional practice and research

Dental hygienists already contribute to team-based care in a variety of practice settings. In certain states, collaborative practice agreements are created by dental hygienists to establish cooperative working relationships with other healthcare providers. These agreements follow many different models, depending, in part, upon the dental hygiene practice acts of the involved states. For instance, in some collaborative agreements, dental hygienists provide care with reduced or no supervision, such as in pediatric offices5 or federally qualified health centers (FQHCs).6 These collaborative practice models expand access to care and delivery of dental hygiene services in diverse settings (see Box1).

Box. 1.

Current Practice Settings for Dental Hygienists

Traditional

Dental offices

Dental vans

Dental schools

Free clinics

Dental hygiene practices

Hospital

Schools

Community

Pediatric offices

Nurse practitioner offices

Migrant clinics

Nonprofit community centers

Residential facilities

Long-term care facilities

Senior centers

State or Federal

Federally qualified health centers

Government public health programs

Correctional institutions

Local and state health departments

Departments of aging or child services

Head start programs

State or group homes

The oral healthcare manager model presented in this article focuses on the dental hygienist as a primary oral healthcare team provider and researcher, regardless of the practice act or setting. For instance, formative research on chairside diabetes screening in dental settings illustrates the dental hygienist as data collector and medical needs assessor, while engaging in interprofessional collaboration.

Contributions of dental hygienists to diabetes research

In view of the bidirectional relationship between diabetes and periodontal disease,7 recent research by Strauss and colleagues described below has illuminated the importance of dental hygienists in supporting the health of dental patients with periodontitis who have, or are at risk for, diabetes. In particular, ongoing research at New York University examines and supports the potential for using gingival crevicular blood to test for hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c),8–10 a test endorsed by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) for the diagnosis and monitoring of diabetes.11 Dental hygienists and dental hygiene students at New York University have actively participated in this line of research, collaborating with dentists, dental students, nurses, and nursing students to recruit patients into research studies, collect blood samples for laboratory analysis of HbA1c levels, refer patients to other healthcare providers, as indicated, and provide important oral-systemic health information to participants.

With the limited knowledge of internists and endocrinologists concerning the oral-systemic connection,12 dental hygienists are vital to the research team, as their diabetes-related activities include: (1) patient education concerning the mechanisms underlying the association between diabetes and periodontal disease; (2) disease prevention; (3) patient counseling concerning the importance of maintaining good glycemic control and practicing regular interdental cleaning and brushing13–14; and (4) the detection and recognition of oral manifestations of diabetes. In fact, because they often have initial contact with the patient followed by frequent visits, and are the primary professionals charged with providing nonsurgical periodontal care,15 dental hygienists may be the first providers to recognize the presence of disease.16

As screening for diabetes at dental visits generates continued interest,17–19 dental hygienists will likely continue to collaborate with other healthcare providers in identifying high risk patients for diabetes and its oral-systemic complications, support treatment plans to best maintain patients’ oral and systemic health, and facilitate the referral of patients to other healthcare providers to address their diabetes-related needs.

Contributions of dental hygienists to implementation science

To explore how best to implement primary care coordination, screening, and monitoring by dental hygienists at chairside, a pilot study was conducted in 10 dental offices in the New York City area with diverse patient populations using an implementation science framework and methods.20–21 Implementation science is defined by the US National Institutes of Health as the study of methods to promote the integration of research findings and evidence into healthcare policy and practice.22 Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, which is a pragmatic structure for approaching complex, interacting, multi-level, and transient states of constructs in the real world by embracing, consolidating, and unifying key constructs from published implementation theories,23 an enhanced conceptual model was developed by a dental hygienist research team member.20–21 The perspectives of dental hygienists and dentists regarding the integration of primary care activities within dental practice were explored, along with their needs regarding primary care activities and use of information technology to obtain clinical information at chairside.

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Because these interviews were conducted by a dental hygienist, the participating dental providers appeared to be at ease and were willing to speak frankly. Findings indicated that both dental hygienists and dentists frequently fail to use evidence-based guidelines to screen their patients for primary care sensitive conditions, that is, conditions that benefit from screening and monitoring by primary care providers, including diabetes and hypertension. Overwhelmingly, the dental providers interviewed believe that tobacco use and poor diet contribute to oral disease, and report using electronic devices at chairside to obtain web-based health information.20 These findings support the premise that more needs to be done at chairside to support dental hygienists and dentists in caring for their patients, and that the dental hygienist is well-positioned to take the lead in coordinating referrals for indicated patient care and counseling.

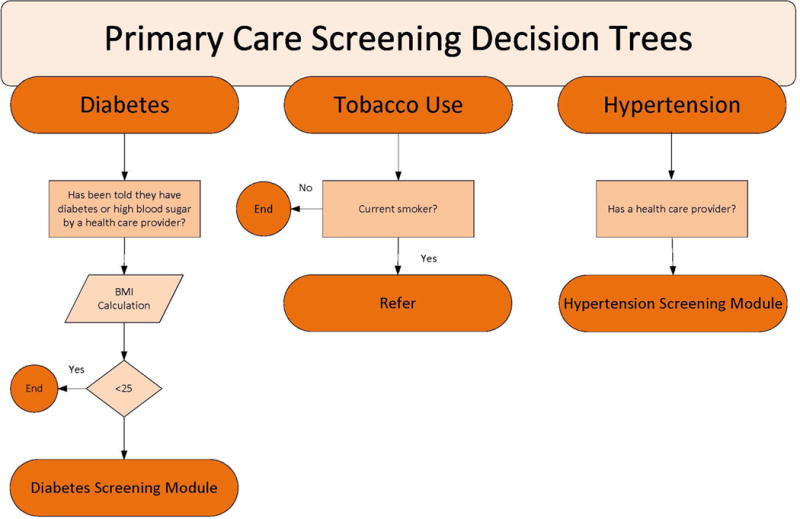

Building upon this qualitative research, an evidence-based clinical decision support system (CDSS) for use by dental hygienists at chairside for tobacco use, hypertension and diabetes screening, and nutrition counseling was developed with the active participation of the dental hygienists involved in the implementation study. An Advisory Board for the project, which included the Assistant Dean for Allied Health Programs, health experts in tobacco cessation, hypertension, diabetes, and nutrition, and three other dental hygienists from the New York University College of Dentistry, appraised the New York State education and scope of practice requirements. Algorithms were created for the four health issues of tobacco use, hypertension and diabetes screening, and nutrition counseling using evidence-based guidelines endorsed by professional authoritative bodies, such as the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) for the management of high blood pressure in adults24 and adapted for dental hygienists (see Figure 3 which covers tobacco use, and hypertension and diabetes screening).

Figure 3. Preliminary decision trees for chairside primary care coordination by dental hygienists.

In this graphic, the preliminary questions that the oral healthcare manager asks of the patient at chairside are depicted. Rather than placing this information in a paper chart or electronic record, the answers are used to guide the patient and provider to the best course of action. The fully developed algorithms for counseling for tobacco use, hypertension screening, diabetes screening, and sugar sweetened food and beverages intake and caries risk for use by dental hygienists at chairside are available in Russell et al.20

These algorithms were incorporated into an electronic tool by an information technology specialist using an iterative process to refine the CDSS, with active input from dental hygienists and dentists at the New York University College of Dentistry and Advisory Board members.21 Next steps are to rigorously evaluate the developed CDSS in a variety of settings with the close collaboration of dental hygienists and other dental and medical providers.

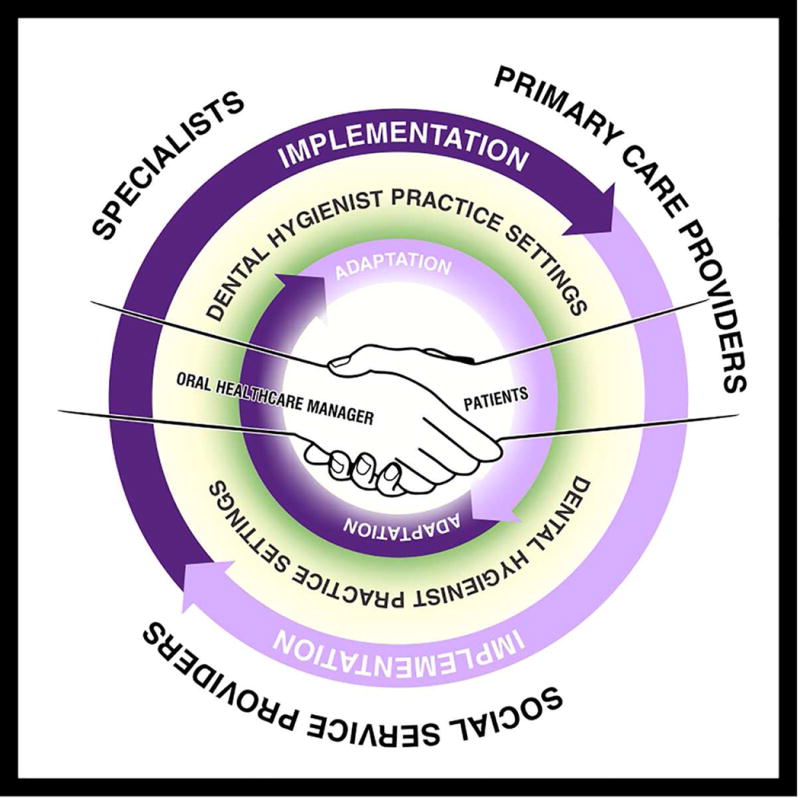

Extending the implementation science framework to the current premise of this paper, dental hygienists are well positioned to act as oral healthcare managers and work hand in hand with patients to facilitate integrated patient-centered care and then monitor the referral to other professionals across settings. (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. The five major domains of the Consolidated Framework of Implementation Research (CFIR), displayed for the oral-systemic care coordination role of the oral healthcare manager.

In this conceptual model, the intervention is oral-systemic care coordination, where dental hygienists act as oral healthcare managers closely aligned with patients across settings to bring about coordinated, holistic, patient-centered care. Adapted from Northridge et al19 and Damschroder et al.21

Fried, in describing a model for interprofessional collaboration around a diagnosis of HPV, suggests that the dental hygienist can provide preventive education and a recommendation to secure immunizations or referrals to counselors to achieve healthy behaviors and practices.25 In Fried’s example, the dental hygienist requests that other professionals provide a diagnosis upon screening and assessment, yet remains part of the loop, seeking ways to improve oral-systemic health outcomes.

Interprofessional core competencies

Team-based practice is not a new concept. Indeed, it has been part of dental delivery systems since the inception of dental assistants and dental hygienists. The IOM report titled, Dental Education at the Crossroads: Challenges and Change26 encourages dental educators to consider the allied dental practitioners in workforce models. This report champions a more open approach to the delivery of care and less focus on protective silos defined by scope of practice acts. Unfortunately not enough has changed since this landmark report was published more than two decades ago. More recently, in 2011, a collaboration formed from diverse health professions, including nursing, dentistry, pharmacy, medicine, and osteopathy, met and created a consensus statement and core competencies for interprofessional practice.27

The core competencies are intended to guide interprofessional practice by providing a unified direction and overriding principles, across provider categories. Guidance is provided in four domains: values and ethics, roles and responsibilities, communication, and teamwork. Each domain is further delineated by competencies that address both patient care and population health, all of which are patient-centered and broadly applicable across practice settings and professions.27 Box 2 lists the four core competency domains along with sample competencies within each domain that are particularly relevant to the role we envision for the oral healthcare manager.

BOX 2.

Interprofessional Education Collaborative four core competency domains and sample competencies within each related to the oral healthcare manager

Values/Ethics for Interprofessional Practice

Work in cooperation with those who receive care, those who provide care, and those who contribute to or support the delivery of prevention and healthcare services.

Recognize and respect the unique cultures, values, roles/responsibilities, and expertise of other health professionals.

Roles/Responsibilities for Collaborative Practice

Communicate one’s roles and responsibilities clearly to patients, families, and other professionals.

Engage diverse healthcare professionals who complement one’s own professional expertise, as well as associated resources, to develop strategies to meet specific patient care needs.

Interprofessional Communication

Communicate consistently the importance of teamwork in community and patient-centered care.

Choose effective communication tools and techniques, including information systems and communication technologies, to facilitate discussions and interactions that enhance team function.

Interprofessional Teamwork and Team-based Care

Engage other health professionals–appropriate to the specific care situation–in shared patient-centered problem solving.

Share accountability appropriately with other professions, patients and communities for outcomes relevant to prevention and healthcare.

Coordinating interprofessional practice

The American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) defines the dental hygienist as a primary care oral health professional who administers a range of services, which are defined by scope, characteristics, and integration of care.28 Important to our vision of the oral healthcare manager, the ADHA considers dental hygienists to be providers that serve as the entry and control point linking the patient to the total healthcare system. They provide coordination with other specialized health or social services to ensure that the patient receives comprehensive and continuous care at both a single point in time as well as over a period of time.28

With the policy shift from fee for service to payment based on quality of care under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,29 interprofessional practice is poised to become the model of the future. Dental hygienists will need to embrace the 4 interprofessional core competencies for this approach to be realized. In addition, knowledge of the potential contributions of other professionals to patient-centered care and a fuller understanding of what those professionals bring to the successful implementation of the comprehensive oral care plan is requisite. Interprofessional collaboration is best viewed as a partnership between a team of healthcare providers and a patient in a participatory, collaborative, and coordinated approach to shared decision-making around health and social issues.30 As the oral healthcare manager, the dental hygienist is part of a team of health professionals with a shared knowledge of each other’s roles in order to achieve patient-centered care (see Box 3).

BOX 3.

Providers on the oral healthcare manager’s team for potential patient referrals

Advanced dental hygiene practitioner

Audiologist

Chiropractor

Dentist

Dental specialist

Dietician

Genetic counselor

Mental health counselor

Nurse

Nurse practitioner

Occupational therapist

Ophthalmologist

Pharmacist

Physical therapist

Physician

Podiatrist

Sleep apnea therapist

Speech-language pathologist

Substance abuse counselor

Surgeon

New skills and integrated systems

Given the ever-changing collaborative practice acts, advanced practice settings, revised role delineations, and new workforce models, the time has come for the dental hygienist to take a leadership role in the interprofessional oral care team. To lead within a healthcare facility, enhanced skills will likely be needed, such as additional education in communication, motivational interviewing, active listening, mindfulness, social networks/family support, financial concerns, access issues, leadership skills, systems thinking, cultural barriers, and health literacy (see Gurenlian, Spolarich and Rogo article in this issue). In particular, efforts are needed to create integrated referral systems for the smooth coordination of multiple health-related issues.

Dental hygienists currently practice in settings listed in Box 1; these opportunities will continue to increase. Technological advances such as chairside decision support systems, additional diabetes clinical assessment techniques, teledentistry, and centralized electronic health records (see Simmons article in this issue) contribute to the feasibility of these concepts. Consultations and referrals will take on a new meaning when the patient does not need to leave the immediate setting, given professional conferencing and integrated oral-systemic electronic health record capabilities (see Simmons article in this issue). Each health condition with oral and systemic components presents an opportunity to explore the scientific, preventive, and educational aspects essential to deliver comprehensive care.

Conclusion

The dental hygienist is well situated to lead in the coordination of oral healthcare for the patient. Dental hygienists have expertise in oral healthcare combined with knowledge of the oral-systemic connection. By serving as the oral healthcare manager, the dental hygienist identifies disease risk and promotes health, and enlists the resources of the patient and other providers for resolving identified health issues. The dental hygienist remains engaged in the process to monitor interventions and outcomes, ensuring that patient-centered care is provided. This article has presented the concept that the dental hygienist oral healthcare manager in interprofessional practice can incorporate and monitor oral and systemic outcomes within dental hygiene care plans. Figure 5 portrays the concept of the dental hygiene oral healthcare manager helping to integrate oral and primary care and coordinating the team of interprofessional providers to implement patient-centered care.

Figure 5. The oral healthcare manager in a patient-centered health facility.

The dental hygienist has the opportunity to lead closer integration of oral and primary care as an oral healthcare manager, by coordinating the team of providers needed to implement comprehensive, patient-centered care. This model also incorporates the IPEC core competencies.

Suggested readings.

INTERPROFESSIONAL EDUCATION AND PRACTICE: A CONCEPT WHOSE TIME HAS COME

Journal of the Academy of Distinguished Educators (JADE), Vol. 3, No. 1. Available at: http://dental.nyu.edu/faculty/academy-of-distinguished-educators/jade.html. Accessed: September 20, 2015.

Contents:

-

“Interprofessional Education and Practice: A Concept Whose Time Has Come”

Stefanie Russell, DDS, MPH, PhD

-

“An Opportunity to Reunite the Mouth with the Body and Make the Patient Whole”

Kathleen Klink, MD, FAAFP, and Renee Joskow, DDS, MPH, FAGD, FACD

-

“Building a Culture of Collaboration”

Judith Haber, PhD, APRN, BC, FAAN

-

“Reconnecting Mouth and Body Requires Rethinking Dental Care Financing”

Marko Vujicic, PhD

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported in the research, analysis, and writing of this paper by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the US National Institutes of Health for the project titled, Primary Care Screening by Dental Hygienists at Chairside: Developing and Evaluating an Electronic Tool (grant UL1TR000038) and by the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research of the US National Institutes of Health for the project titled, Integrating Social and Systems Science Approaches to Promote Oral Health Equity (grant R01-DE023072).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Cheryl Westphal Theile, Email: cmw1@nyu.edu, Clinical Professor, Dental Hygiene Programs, New York University College of Dentistry, 212-998-9390 (w), 212-995-4593 (fax).

Shiela Strauss, Email: ss4313@nyu.edu, Associate Professor, New York University College of Nursing, 212-998-5280 (w), 212-995-3143 (fax).

Mary Evelyn Northridge, Email: men6@nyu.edu, Associate Professor, Department of Epidemiology & Health Promotion, New York University College of Dentistry, 212-998-9728 (w).

Shirley Birenz, Email: ssb254@nyu.edu, Clinical Assistant Professor, Dental Hygiene Programs and Research Associate, Department of Epidemiology & Health Promotion, New York University College of Dentistry, 212-992-7005 (w).

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Health professional education: A bridge to quality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furgeson D, Kinney J, Gwozdek A, Wilder R, Inglehart M. Interprofessional education in U.S. dental hygiene programs: a national study. J Dent Educ. 2015;79:1286–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Northridge ME, Glick M, Metcalf SS, Shelley D. Public health support for the health home model. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1818–20. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun P, Kahl S, Ellison M, Ling S, Widmer-Racich K, Daley M. Feasibility of collocating dental hygienists into medical practices. J Public Health Dent. 2013;73:187–94. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maxey H. Integration of oral health with primary care in health centers: Profiles of five innovative models. Washington, DC: National Association of Community Health Centers; 2015. Available at: http://.nachc.com/client//Integration%20of%20Oral%20Health%20with%20Primary%20Care%20in%20Health%20Centers.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, et al. Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009—2012. J Periodontol. 2015;86:611–22. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strauss SM, Tuthill J, Singh G, et al. A novel intra-oral diabetes screening approach in periodontal patients: Results of a pilot study. J Periodontol. 2012;83:699–706. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strauss SM, Rosedale MT, Pesce MA, et al. The potential for glycemic control monitoring and screening for diabetes at dental visits using oral blood. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:796–801. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosedale MT, Strauss SM. Diabetes screening at the periodontal visit: patient and provider experiences with two screening approaches. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012;10:250–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2011.00542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Supp 1):S1–S93. doi: 10.2337/cd20-as01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Owens JB, Wilder RS, Southerland JH, Buse JB, Malone RM. Physicians’ knowledge about the oral-diabetes connection. J Dent Educ. 2011;75:329–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohrn K. The role of dental hygienists in oral health prevention. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2004;2(Suppl 1):277–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuen HK, Wolf BJ, Bandyopadhyay D, Magruder KM, Salinas CF, London SD. Oral health knowledge and behavior among adults with diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;86:239–46. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams KB. Periodontal disease and type 2 diabetes. J Dent Hyg. 2009;83:8–44. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hays WA, Calderon LL. A dental hygiene perspective in the detection of diabetes mellitus. NDA J. 1996;47:16–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright D, Muirhead V, Weston-Price S, Fortune F. Type 2 diabetes risk screening in dental practice settings: A pilot study. Br Dent J. 2014;216:E15. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lalla E, Cheng B, Kunzel C, Burkett S, Ferraro A, Lamster IB. Six-month outcomes in dental patients identified with hyperglycaemia: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42:228–25. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Genco RJ, Schifferle RE, Dunford RG, Falkner KL, Hsu WC, Balukjian J. Screening for diabetes mellitus in dental practices: A field trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:57–64. doi: 10.14219/jada.2013.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Northridge ME, Birenz S, Gomes G, Golembeski CA, Greenblatt AP, Shelley D, Russell SL. Views of dental providers on primary care coordination at chairside. J Dent Hyg. (in re-review) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russell SL, Greenblatt AP, Gomes D, Birenz S, Golembeski CA, Shelley D, McGuirk M, Eisenberg E, Northridge ME. Toward implementing primary care at chairside: developing a clinical decision support system for dental hygienists. J Evid Based Dent Pract. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2015.08.003. (in press) DEEPA- UPDATE IF YOU CAN PLEASE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US National Institutes of Health. Fogarty International Center. Implementation Science Information and Resources. Available at: http://www.fic.nih.gov/researchtopics/pages/implementationscience.aspx. Accessed November 16, 2015.

- 23.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014;311:507–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fried J. Confronting human papilloma virus/oropharyngeal cancer: A model for interprofessional collaboration. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2014;14(Suppl):136–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institute of Medicine. Dental Education at the Crossroad: Challenges and Change. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Policy manual. Available at: https://www.adha.org/resources-docs/7614_Policy_Manual.pdf.

- 29.Sparer M. US health care reform and the future of dentistry. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1841–1844. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Interprofessional Education for Collaboration Expert Panel. Learning how to improve health from interprofessional models across the continuum of education to practice: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]