Abstract

Objective

Exposing to NMDAR receptor antagonists, such as ketamine, produces schizophrenia-like symptoms in humans and deteriorates symptoms in schizophrenia patients. Meanwhile, schizophrenia is associated with alterations of cytokines in the immune system. This study aims to examine the serum TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 levels in chronic human ketamine users as compared to healthy subjects. The correlations between the serum cytokines levels with the demographic, ketamine use characteristics and psychiatric symptoms were also assessed.

Methods

155 subjects who fulfilled the criteria of ketamine dependence and 80 healthy control subjects were recruited. Serum TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 levels were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The psychiatric symptoms of the ketamine abusers were assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

Results

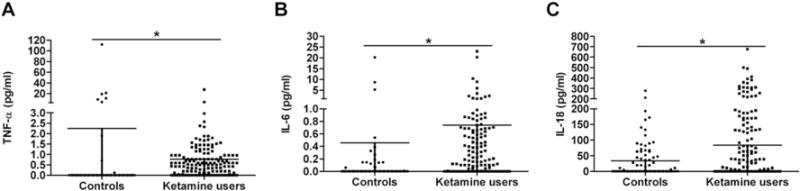

Serum IL-6 and IL-18 levels were significantly higher, while serum TNF-α level was significantly lower among ketamine users than among healthy controls (p < 0.05). Serum TNF-α levels showed a significant negative association with PANSS total score (r = −0.210, p < 0.01) and negative subscore (r = −0.300, p < 0.01). No significant association was found between PANSS score and serum levels of IL-6 and IL-18.

Conclusions

Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 were altered in chronic ketamine abusers which may play a role in schizophrenia-like symptoms in chronic ketamine abusers.

Keywords: Ketamine, Schizophrenia, Cytokines, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-18

1. Introduction

Ketamine, a phencyclidine (PCP) derivative, is an un-competitive antagonist of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR). It was first synthesized by Calvin Stevens of the Parke-Davis pharmaceutical company in 1962 (Rowland, 2005). Ketamine is recognized as an anesthetic in 1964 (Corssen and Domino, 1966), with additional analgesic, amnesic, pain management and possible fast acting anti-depressant effects (Rowland, 2005; Abi-Dargham et al., 2002; Berman et al., 2000; Niesters et al., 2012). However, ketamine also provoke adverse reactions, including hallucinations, delirium, delusion, confusion, and vivid dreams. These effects are thought to contribute to the abuse of this drug (Frohlich and Van Horn, 2014; Morgan and Curran, 2012). The recreational use of ketamine became popular in North America, Europe, Asia and many other parts of the world. In the past two decades ketamine appears to be one of the most popular drugs for recreational use in China teenagers. Several epidemiological surveys showed that the ketamine abuser among drug addicts had increased from 21.5% in 2001 to 40% in 2009 in China (Lian et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2009a,b). Correspondingly, ketamine was classified as a psychotropic substance of categoryI in 2004 due to its psychedelic properties and increased abuse in China (FDA, 2004).

Ketamine could cause acute effects at subanaesthetic doses that resemble the positive, negative and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia in healthy volunteers (Krystal et al., 1994). When administered to schizophrenia patients with stable condition, ketamine may result in a resurgence of symptoms indistinguishable from the idiopathic disease (Lahti et al., 1995). Chronic use also has been suggested to produce schizophrenia-like symptoms (Frohlich and Van Horn, 2014). Thus, ketamine, the NMDAR antagonist, is increasingly used to model the cognitive deficits and clinical symptoms of schizophrenia (Frohlich and Van Horn, 2014). Despite increasing interest in the NMDAR antagonist model of schizophrenia, acute ketamine administration has been suggested to lead to somewhat unlike idiopathic symptoms because of its relatively short-lived effects (Tsa and Coyle, 2002). In contrast, chronic ketamine administration may be more representative of the long-term NMDA dysfunction hypothesized to occur in schizophrenia (Tsa and Coyle, 2002). In rats, repeated administration of ketamine has been demonstrated to cause neurodegenerative changes in brain regions similar these influenced in schizophrenia (Keilhoff et al., 2004). In mice, subchronic administration of ketamine induced an increase in NADPH-oxidase activity and increased oxidative stress in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), hippocampus and thalamus, leading to a loss of parvalbumin interneurons which similar to what observed in schizophrenia (Behrens et al., 2007). Taken together, chronic administration of ketamine initializes a great many of adaptation mechanisms, which associate with findings observed in schizophrenia patients.

Although chronic NMDA receptor blockade is an established preclinical model of schizophrenia and immune abnormalities may be involved in the etiology and pathophysiology of schizophrenia (Maes et al., 2002; Muller et al., 2000; Sirota et al., 2005; Song et al., 2009), it is not known whether chronic NMDA receptor blockade in humans is associated with alterations of serum cytokines levels and whether the alterations of cytokines are related to schizophrenia-like symptoms. As we known, there have been no attempts to investigate the potential relationships between inflammatory cytokines and chronic ketamine abusers. In this study, we examined the serum TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 levels in chronic human ketamine users in comparison to healthy control subjects. The correlations between the serum cytokines levels with the subjects’ demographic characteristics, pattern of ketamine use and psychiatric symptoms were also analyzed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

All chronic ketamine users were recruited from Guangzhou Brain hospital and Guangzhou Baiyun voluntary drug rehabilitation hospital. Healthy controls were recruited through advertisement. A semi-structured interview was applied to investigate general demographic information, psychopathological symptoms and substances usage for chronic ketamine abusers. The inclusion criteria for ketamine abusers included ketamine dependence according to DSM-IV-TR, frequent ketamine use (defined as subjects taking ketamine at least four times every week), no history of head injury or organic brain damage, no other substances dependence, and no other substances use other than alcohol and tobacco for at least 6 months. Inclusion criteria for healthy subjects were no axisI diagnosis in accordance with DSM-IV-TR criteria, no familial history (in first- or second-degree relatives) of mental disorders, and no physical disease. Exclusion criteria of participants included any known organic diseases, history of head trauma with loss of consciousness, any unstable physical illnesses and impairments of color vision or hearing. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Brain hospital, Guangzhou Huiai Hospital, the Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after giving information about the study.

Clinical symptoms of ketamine users were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Leucht et al., 2005) administered by physicians with at least 3 years’ clinical experience. Assessment of inter-rater reliability for raters in this study was in the excellent to good range, with intra-class correlations ranging from 0.90 to 0.96.

2.2. Serum TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 measurement

Venous blood sample was collected from each subject using standard venipuncture technique. The average days of blood drawing since last ketamine use was 8.9 ± 7.4 days. Serum was obtained by centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min, then aliquoted and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 were measured by using commercial enzyme linked immunosorbent (ELISA) kits (eBioscience, San Diego, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The sensitivities of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 were 2.3 pg/mL, 0.92 pg/mL and 9 pg/mL, with inter-assay variation coefficients of 7.4%, 5.2% and 8.1%, and intra-assay variation coefficients of 6.0%, 3.4% and 6.5%, respectively. No cross-reactivity was observed. All measurements were performed in duplicate and expressed as pg/ml. Cytokine levels were measured using a microtiter plate reader (Bio-Rad iMark, California, USA) set at 450 nm.

2.3. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The difference of gender variables between ketamine users and healthy controls was analyzed using Chi-square test. Non-parametric analyses using the two-sided Mann–Whitney U tests were used to examine age variables in the patient and control groups. We compared serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 in the patient and control groups using Non-parametric analyses. Then, we further analyzed the difference of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 levels in the two groups using a univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with gender as covariates. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to evaluate the correlations between serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 and clinical characteristics in ketamine users. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences at p < 0.05 level (two tailed) were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and demographic data

Clinical and demographic characteristics of chronic ketamine users and healthy subjects were shown in Table 1. One hundred fifty-five chronic ketamine users and 80 healthy controls participated in the study. There were significant differences in gender between the two groups, but no significant difference in age (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of ketamine users and healthy controls.

| Ketamine users (N = 155) | Healthy controls (N = 80) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years ± SEM) | 25.90 ± 0.40 | 26.77 ± 0.60 | ||

| Age range (years) | 17–44 | 18–48 | ||

| Gender* | Male | Female | Male | Female |

| 145 (93.55%) | 10 (6.45%) | 65 (81.25%) | 15 (18.75%) | |

| Duration of ketamine use (years ± SEM) | 3.01 ± 0.16 | |||

| Dose of ketamine use (g/day ± SEM) | 3.03 ± 0.19 | |||

| Frequency of ketamine use (day/week ± SEM) | 6.45 ± 0.06 | |||

| Use of other psychoactive compounds | Yes | No | ||

| 132(85.20%) | 23 (14.80%) | |||

| Alcohol | Yes | No | ||

| 131(84.50%) | 24 (15.50%) | |||

| Smoking | Yes | No | ||

| 150 (96.80%) | 5 (3.20%) | |||

| PANSS | ||||

| P subscoreb (±SEM) | 7.97 ± 0.14 | |||

| N subscorec (±SEM) | 13.23 ± 0.30 | |||

| G subscored (±SEM) | 24.46 ± 0.41 | |||

| total scorea (±SEM) | 45.65 ± 0.69 | |||

| Serum TNF-α* (pg/ml ± SEM) | 0.77 ± 0.18 | 2.24 ± 1.44 | ||

| Serum IL-6* (pg/ml ± SEM) | 0.74 ± 0.15 | 0.45 ± 0.28 | ||

| Serum IL-18* (pg/ml ± SEM) | 83.72 ± 10.04 | 33.79 ± 6.35 | ||

Positive and Negative Symptom Scale.

PANSS positive symptom subscale.

PANSS negative symptom subscale.

PANSS general psychopathology subscale.

Denotes p < 0.05.

3.2. Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18

Serum IL-6 and IL-18 levels were significantly higher, while serum TNF-α level was lower in ketamine users than in healthy controls (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1). When gender was added as potentially confounding covariate terms, the differences between the ketamine users and controls were still significant (p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Serum TNF-α (A), IL-6 (B) and IL-18 (C) levels in healthy controls (n = 80) and ketamine users (n = 155). Serum IL-6 and IL-18 levels were significantly higher among ketamine users than among healthy controls, whereas serum TNF-α level was significantly lower in ketamine users. The sample means are indicated by the horizontal line. The error bars represent standard deviations. * denotes p < 0.05.

3.3. Correlations of serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 with demographic, drug use characteristics and psychiatric symptoms

The correlations between cytokine levels with demographic, drug use characteristics and psychiatric symptoms in the ketamine group were shown in Table 2. The results found that serum TNF-α levels showed a significant negative correlation with PANSS total score (r = −0.210, p < 0.01) and negative subscore (r = −0.300, p < 0.01). Serum IL-6 and IL-18 levels were not significantly correlated with demographic and drug use characteristics as well as with psychiatric symptoms (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients between cytokine concentrations and clinical characteristics of ketamine users.

| TNF-α | IL-6 | IL-18 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.041 | 0.178 | 0.303 |

| Gender | −0.083 | −0.044 | −0.122 |

| Duration of ketamine use (years) | −0.019 | 0.030 | 0.050 |

| Dose of ketamine use (gram/day) | −0.089 | 0.086 | 0.073 |

| Frequency of ketamine use (days per week) | −0.009 | −0.056 | 0.066 |

| Use of other psychoactive compounds | 0.084 | −0.001 | −0.040 |

| Alcohol | 0.088 | 0.165 | −0.112 |

| Smoking | 0.002 | 0.000 | −0.144 |

| PANSS total scorea | −0.210** | −0.086 | −0.037 |

| P subscoreb | −0.149 | −0.052 | −0.011 |

| N subscorec | −0.300** | −0.100 | −0.096 |

| G subscored | −0.045 | −0.011 | 0.029 |

Positive and Negative Symptom Scale.

PANSS positive symptom subscale.

PANSS negative symptom subscale.

PANSS general psychopathology subscale.

Denotes p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to report the alteration of serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 in chronic ketamine users. We found that serum IL-6 and IL-18 levels were significantly higher in chronic ketamine users than in healthy controls, whereas serum TNF-α level was significantly lower in ketamine users. Moreover, TNF-α level was significantly negatively correlated with PANSS total score and negative subscore.

Ketamine has been showed to interfere with inflammatory response. Previous studies showed that ketamine could decrease the syntheses of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced proinflammatory cytokine, such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β, suggesting a close relationship between ketamine and cytokine levels (Chang et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2009a,b).

TNF-α is a multifunctional pro-inflammatory cytokine that is produced primarily by monocytes and macrophages. TNF-α plays a key role in mediating the complex events involved in inflammation and immunity. The roles of TNF-α in controlling neuronal excitability and metabolisms of glutamate, dopamine, and serotonin neurotransmitters make it an outstanding candidate for etiology and pathophysiology of schizophrenia (Tian et al., 2014). Alterations in serum TNF-α level in chronic schizophrenia patients have been reported previously, but with inconsistent results, being no different (Pedrini et al., 2012; Kunz et al., 2011), elevated (Lin et al., 1998; Naudin et al., 1997; Beumer et al., 2012; García-Miss et al., 2010; Luo et al., 2014) or reduced (Francesconi et al., 2011; Lv et al., 2014; Potvin et al., 2008), as compared with healthy control subjects. Nonetheless, these evidences implicate the role of TNF-α and TNF-α-related signaling pathways in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. In the ketamine animal model of schizophrenia, a slight decrease in TNF-α level was observed during ketamine exposure in vitro (Behrens et al., 2008). In the present study, we found that serum TNF-α level was significantly lower in chronic ketamine users (p < 0.05) and serum TNF-α level showed a significant negative association with PANSS total score and negative subscore (p < 0.01). Recent studies have shown that decreased serum TNF-α level in chronic schizophrenia patients was significantly negatively correlated with PANSS total score and positive subscore (Lv et al., 2014; Potvin et al., 2008), suggesting patients with lowered TNF-α levels would be more likely to have severer psychopathological symptoms. The negative correlation TNF-α level with the severity of psychopathological symptoms may seem contradictory to what proinflammatory cytokines are generally recognized as worsening factors for the pathology of psychiatric disorders at the first glance. However under certain physiological conditions, pro-inflammatory cytokines promote neurotrophic activities, containing cell signal transduction, synaptic plasticity, and neurogenesis (Dheen et al., 2007). We hypothesized that the effects of TNF-α on brain functions and psychotic symptoms may be different under acute versus chronic conditions and there might be a bi-directional pathway of TNF-α under different circumstances. Ketamine users in our study were chronic. In such chronic status, cytokines such as TNF-α may manifest beneficial rather than harmful effects. TNFα-related inflammatory pathways may participate in processes related to psychiatric symptoms in schizophrenia. Recently, TNF-α has been proved to have key roles in central nervous system (CNS) development and functions including neuronal plasticity, cognition, and behavior (Garay and McAllister, 2010), and disrupted TNF-α signaling leads to abnormal development of the hippocampus and impairments in cognitive function (Tonelli and Postolache, 2005; Baune et al., 2012). Moreover, TNF-α was involved in dopaminergic processes and played a key role in the pathogenesis of dopaminergic neurodegeneration (Nakajima et al., 2004; Niwa et al., 2007). Thus, TNF-α has been proposed to be related to schizophrenia-like psychiatric symptoms.

IL-6 is also a proinflammatory cytokines, promoting the immune response to infection and inflammation by motivating leukocytes to inflammatory sites and/or by activating inflammatory cells (Lv et al., 2014). Although the role of IL-6 in brain development and central nervous system (CNS) disease is not well studied, several studies have demonstrated that production of IL-6 in the CNS was shown to be directly implicated in the impairment of working memory caused by peripheral inflammation (Sparkman et al., 2006), as well as in the amount of stored information during in vivo long-term potentiation (LTP) (Balschun et al., 2004). It has been demonstrated that both first episode and chronic schizophrenia patients showed a significant increased level of IL-6 in comparison to healthy control subjects (Beumer et al., 2012; Pedrini et al., 2012; García-Miss et al., 2010; Song et al., 2013), suggesting IL-6 may play a role to the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Most importantly, recent studies have shown that maternal IL-6 was responsible for the delayed schizophrenia-like behavior detected in the offspring in the rodent maternal-infection model of schizophrenia (Smith et al., 2007). It has also been reported that IL-6 mediated the increase in NADPH-oxidase in the ketamine model of schizophrenia (Behrens et al., 2008). Early evidence proved that decreased antioxidant defenses were commonly found in schizophrenia patients, and a recent clinical trial showed that symptoms of schizophrenia could be attenuate by increasing these defenses (Berk et al., 2008). Another clinical trial showed that D-serine, a NMDAR agonist reduced the serum IL-6 concentration in individuals at clinical high risk of schizophrenia and the reduction in IL-6 concentration significantly correlated with improvement in negative symptoms (Kantrowitz et al., 2015). Hence, possibly, reduced levels of IL-6 may ameliorate the propsychotic effects of ketamine, indicating IL-6 is the possible downstream mediator of ketamine effects. Consistent with these results, we found that chronic ketamine users had elevated serum levels of IL-6 compared with healthy control subjects, which further confirmed IL-6 played a role in ketamine-induced schizophrenia-like effects.

IL-18, a member of the IL-1 family of pro-inflammatory cytokines, is an important and pleiotropic cytokine modulator of immune responses (Tanaka et al., 2000). Based on recent studies, IL-18 is also a presumed ‘key’ cytokine in the CNS, mediating two distinct immunological regulatory pathways of cytotoxic and inflammatory responses under neuropathological conditions (Felderhoff-Mueser et al., 2005). Therefore, IL-18 appears to be a communication signal between the nervous and immune systems, mediating neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative processes as well as influencing homeostasis and behavior (Alboni et al., 2010). Previous studies in Japanese, Italian and Chinese schizophrenic patients have shown that Il-18 level was remarkably higher in schizophrenia patients than in controls (Tanaka et al., 2000; Reale et al., 2011; Xiu et al., 2012; Palladino et al., 2012; Luo et al., 2014) indicating alterations of IL-18 may be involved in pathophysiology of schizophrenia. To date, there have been no reports to study the role of IL-18 in ketamine animal or human model of schizophrenia. Nonetheless, our finding of elevated serum IL-18 levels in ketamine users was in line with these results of schizophrenic patients, providing additional evidence that elevated IL-18 level may play important role in psychopathology of schizophrenia.

Cytokines are key chemical messengers between immune cells and play an important role in immune regulation. They also play a critical role in infectious and inflammatory processes by mediating the crosstalk between the brain and the immune system, which has become a recent focus of immunologic research in schizophrenia (Altamura et al., 2014). The molecular mechanisms underlying the elevated or reduced serum levels of cytokines in chronic schizophrenia patients and chronic ketamine abusers are largely unknown. Previous studies demonstrated that abnormities of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-18, were found in schizophrenic patients and these alterations might have implications for psychopathological symptoms in schizophrenia (Potvin et al., 2008; García-Miss et al., 2010; Kunz et al., 2011; Beumer et al., 2012; Pedrini et al., 2012; Borovcanin et al., 2012; Luo et al., 2014; Lv et al., 2014). It is possible that an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines play a role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and the schizophrenia-like symptoms in ketamine abusers through various mechanisms. In present study we only measured the level pro-inflammatory cytokines. It is important to also evaluate the level of anti-inflammatory cytokines in further study to profile the inflammatory state in chronic ketamine users. In this study, we found that serum IL-6 and IL-18 levels were not significantly correlated with psychiatric symptoms in chronic ketamine users. However, previous studies have reported positive correlations between levels of IL-6 and PANSS positive scores in subjects with schizophrenia (Dimitrov et al., 2013). It has also been reported that IL-18 was positively correlated with the PANSS general psychopathology subscore in chronic schizophrenic patients (Xiu et al., 2012). The inconsistencies of these results might be due to the small sample size, the relative mild psychiatric symptoms in chronic ketamine users. Further follow-up studies and replication of these findings are necessary.

Although the present study has a relatively large sample size several limitations should be noticed. Firstly, most ketamine users recruited in this study also had taken psychoactive drugs other than ketamine. The usage of such compounds might also have an impact on the cytokines levels. But the ketamine users recruited in our study had no other reported substance dependencies other than tobacco and no other substances use other than alcohol and tobacco for at least 6 months. So the potential confounding factors are likely to be limited and it seems reasonable to consider that the altered serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 may primarily resulting from chronic ketamine use. Secondly, all ketamine patients in this study were treated with antipsychotic drugs. Many studies have demonstrated that treatment with some antipsychotic drugs may have immunosuppressive effects and influence the cytokine network (Zhang et al., 2004; Watanabe et al., 2010). So in order to eliminate the possible confounding factor of anti-psychotic drugs, future studies with antipsychotics-naive patients would be necessary. Thirdly, most ketamine users recruited in this study drank alcohol and smoked. Alcohol drinking and smoking are possible confounding factors in the differences in cytokine levels. In the present study serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 in ketimine users showed no significant association with alcohol drinking and smoking. Despite no correlation between cytokine levels and these potential confounding factors, the confounder effect of these factors cannot be completely eliminated. Further prospective studies and replication of these findings are necessary. Nonetheless, our present findings may provide some insight into the relationship between the serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 and schizophrenia-like symptoms in chronic ketamine abuser.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that serum IL-6 and IL-18 levels were significantly higher among ketamine users than among healthy controls, whereas serum TNF-α level was significantly lower in ketamine users. TNF-α level was significantly negatively associated with PANSS total score and negative subscore. These findings in the present study provided preliminary evidence that alterations of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 levels may be play a role in ketamine abuse related symptoms.

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding

This work was supported by grants to Ni Fan from National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81300959), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (grant number 2014J4100134), Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry (20131792), Chinese National Key Clinical Program in Psychiatry to Guangzhou Brain Hospital (grant number 201202001), and grants from Guangzhou Municipal Health Bureau (grant number 20131A011091) and Guangzhou Municipal Key Discipline in Medicine to Guangzhou Brain Hospital (grant number GBH2014-ZD03), and by grants to Hongbo He from Chinese National Key Clinical Program in Psychiatry to Guangzhou Brain Hospital (grant number 201201001), and grant from Guangzhou Municipal Health Bureau (grant number 20131A011083).

Footnotes

Contributors

Ni Fan and Yayan Luo designed the study and wrote the protocol. Xiaoyin Ke, Yi Ding, and Daping Wang were responsible for recruiting subjects. Yayan Luo, Minling Zhang and Xini Huang performed the experiments. Yayan Luo and Ni Fan managed the literature searches and analyses. Ke Xu, Yuping Ning, Xuefeng Deng and Hongbo He contributed to the writing of the paper. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- Abi-Dargham A, Mawlawi O, Lombardo I, et al. Prefrontal dopamine D1 receptors and working memory in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3708–3719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03708.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alboni S, Cervia D, Sugama S, Conti B. Interleukin 18 in the CNS. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;29:7–9. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altamura AC, Buoli M, Pozzoli S. Role of immunological factors in the pathophysiology and diagnosis of bipolar disorder: comparison with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;68:21–36. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balschun D, Wetzel W, Del Rey A, et al. Interleukin-6: a cytokine to forget. FASEB J. 2004;18:1788–1790. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1625fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baune BT, Konrad C, Grotegerd D, et al. Tumor necrosis factor gene variation predicts hippocampus volume in healthy individuals. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens MM, Ali SS, Dao DN, et al. Ketamine-induced loss of phenotype of fast-spiking interneurons is mediated by NADPH-oxidase. Science. 2007;318:1645–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1148045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens MM, Al ISS, Dugan LL. Interleukin-6 mediates the increase in NADPH-oxidase in the ketamine model of schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13957–13966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4457-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Copolov D, Dean O, et al. N-acetyl cysteine as a glutathione precursor for schizophrenia — a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:351–354. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beumer W, Drexhage RC, De Wit H, et al. Increased level of serum cytokines, chemokines and adipokines in patients with schizophrenia is associated with disease and metabolic syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:1901–1911. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borovcanin M, Jovanovic I, Radosavljevic G. Elevated serum level of type-2 cytokine and low IL-17 in first episode psychosis and schizophrenia in relapse. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:1421–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Chen TL, Sheu JR, Chen RM. Suppressive effects of ketamine on macrophage functions. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;204:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TL, Chang CC, Lin YL, et al. Signal-transducing mechanisms of ketamine-caused inhibition of interleukin-1b gene expression in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated murine macrophage-like raw 264.7 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009a;40:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Fan C, Du J, et al. DSM-IV axle I diagnoses analysis in 506 patients with substance dependence. Chin J Drug Depend. 2009b;18:200–202. [Google Scholar]

- Corssen G, Domino EF. Dissociative anesthesia: further pharmacologic studies and first clinical experience with the phencyclidine derivative CI-581. Anesth Analg. 1966;45:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dheen ST, Kaur C, Ling EA. Microglial activation and its implications in the brain diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1189–1197. doi: 10.2174/092986707780597961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov DH, Lee S, Yantis J, et al. Differential correlations between inflammatory cytokines and psychopathology in veterans with schizophrenia: potential role for IL-17 pathway. Schizophr Res. 2013;151:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA, C. Notice on further strengthening the management of ketamine released by China Food and Drug Administration. Capital Med. 2004;15:24. [Google Scholar]

- Felderhoff-Mueser U, Schmidt OI, Oberholzer A, et al. IL-18: a key player in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration? Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francesconi LP, Ceresér KM, Mascarenhas R, et al. Increased annexin-V and decreased TNF-α serum levels in chronic-medicated patients with schizophrenia. Neurosci Lett. 2011;502:143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich J, Van Horn JD. Reviewing the ketamine model for schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28:287–302. doi: 10.1177/0269881113512909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garay PA, McAllister AK. Novel roles for immune molecules in neural development: implications for neurodevelopmental disorders. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2010;2:136. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Miss Mdel R, Pérez-Mutul J, López-Canul B, et al. Folate, homocysteine, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor alfa levels, but not the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism, are risk factors for schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz JT, Woods SW, Petkova E, et al. D-serine for the treatment of negative symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk of schizophrenia: a pilot, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised parallel group mechanistic proof-of-concept trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:403–412. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00098-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilhoff G, Becker A, Grecksch G, et al. Repeated application of ketamine to rats induces changes in the hippocampal expression of parvalbumin, neuronal nitric oxide syn-thase and cFOS similar to those found in human schizophrenia. Neuroscience. 2004;126:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, et al. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:199–214. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz M, Ceresér KM, Goi PD, et al. Serum levels of IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: differences in pro- and anti-inflammatory balance. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2011;33:268–274. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462011000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti AC, Koffel B, LaPorte D, Tamminga CA. Subanesthetic doses of ketamine stimulate psychosis in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;13:9–19. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00131-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Kane JM, Kissling W, et al. What does the PANSS mean? Schizophr Res. 2005;79:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian Z, Liu Z, Liu R, et al. Epidemiological survey of ketamine in China. Chin J Drug Depend. 2005;14:280–283. [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Kenis G, Bignotti S, et al. The inflammatory response system in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: increased serum interleukin-6. Schizophr Res. 1998;32:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo YY, He HB, Zhang ML, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 elevated in chronic schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res. 2014;159:556–557. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv MH, Tan YL, Yan SX, et al. Decreased serum TNF-alpha levels in chronic schizophrenia patients on long-term antipsychotics: correlation with psychopathology and cognition. Psychopharmacology. 2014;232:165–172. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3650-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, Bocchio Chiavetto L, Bignotti S, et al. Increased serum interleukin-8 and interleukin-10 in schizophrenic patients resistant to treatment with neuroleptics and the stimulatory effects of clozapine on serumleukemia inhibitory factor receptor. Schizophr Res. 2002;54:281–291. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CJ, Curran HV. Ketamine use: a review. Addiction. 2012;107:27–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller N, Riedel M, Gruber R, et al. The immune system and schizophrenia. An integrative view. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;917:456–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima A, Yamada K, Nagai T, et al. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in methamphetamine-induced drug dependence and neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2212–2225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4847-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naudin J, Capo C, Giusano B, et al. A differential role for interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in schizophrenia? Schizophr Res. 1997;26:227–233. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(97)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesters M, Khalili-Mahani N, Martini C, et al. Effect of subanesthetic ketamine on intrinsic functional brain connectivity: a placebo-controlled functional magnetic resonance imaging study in healthy male volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:868–877. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31826a0db3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa M, Nitta A, Yamada Y, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and its inducer inhibit morphine-induced rewarding effects and sensitization. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:658–668. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palladino I, Salani F, Ciaramella A, et al. Elevated levels of circulating IL-18BP and perturbed regulation of IL-18 in schizophrenia. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:206. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrini M, Massuda R, Fries GR, et al. Similarities in serum oxidative stress markers and inflammatory cytokines in patients with overt schizophrenia at early and late stages of chronicity. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:819–824. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potvin S, Stip E, Sepehry AA, et al. Inflammatory cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: a systematic quantitative review. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reale M, Patruno A, De Lutiis MA, et al. Dysregulation of chemo-cytokine production in schizophrenic patients versus healthy controls. BMC Neurosci. 2011;25:12–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland LM. Subanesthetic ketamine: how it alters physiology and behavior in humans. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2005;76:C52–C58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirota P, Meiman M, Herschko R, Bessler H. Effect of neuroleptic administration on serumlevels of soluble IL-2 receptor-alpha and IL-1 receptor antagonist in schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Res. 2005;134:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SE, Li J, Garbet TK, et al. Maternal immune activation alters fetal brain development through interleukin-6. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10695–10702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2178-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song XQ, Lv LX, Li WQ, et al. The interaction of nuclear factor-kappa B and cytokines is associated with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Fan Xd, et al. Elevated levels of adiponectin and other cytokines in drug naïve, first episode schizophrenia patients with normal weight. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkman NL, Buchanan JB, Heyen JR, et al. Interleukin-6 facilitates lipopolysaccharide-induced disruption in working memory and expression of other proinflammatory cytokines in hippocampal neuronal cell layers. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10709–10716. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3376-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka KF, Shintani F, Fujii Y, et al. Serum interleukin-18 levels are elevated in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2000;96:75–80. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(00)00196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Tan Y, Chen D, et al. Reduced serum TNF alpha level in chronic schizophrenia patients with or without tardive dyskinesia. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;54:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonelli LF, Postolache TT. Tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-6 and major histocompatibility complex molecules in the normal brain and after peripheral immune challenge. Neurol Res. 2005;27:679–684. doi: 10.1179/016164105X49463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsa G, Coyle JT. Glutamatergic mechanisms in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:165–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.082701.160735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang Y, Lian Z, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of three new drugs abuse in Beijing. Chin J Drug Depend. 2008;17:445–454. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Someya T, Nawa H. Cytokine hypothesis of schizophrenia pathogenesis: evidence from human studies and animal models. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;64:217–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiu MH, Chen DC, Wang D, et al. Elevated interleukin-18 serum levels in chronic schizophrenia: association with psychopathology. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:1093–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XY, Zhou DF, Cao LY, et al. Changes in serum interleukin-2, -6, and -8 levels before and during treatment with risperidone and haloperidol: relationship to outcome in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:940–947. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]