Abstract

Many studies of right/left differences in motor performance related to handedness have employed tasks that use arm movements or combined arm and hand movements rather than movements of the fingers per se, the well-known exception being rhythmic finger tapping. We therefore explored four simple tasks performed on a small touchscreen with relatively isolated movements of the index finger. Each task revealed a different right/left performance asymmetry. In a step-tracking Target Task, left-handed subjects showed greater accuracy with the index finger of the dominant left hand than with the nondominant right hand. In a Center-Out Task, right-handed subjects produced trajectories with the nondominant left hand that had greater curvature than those produced with the dominant right hand. In a continuous Circle Tracking Task, slips of the nondominant left index finger showed higher jerk than slips of the dominant right index finger. And in a continuous Complex Tracking Task, the nondominant left index finger showed shorter time lags in tracking the relatively unpredictable target than the dominant right index finger. Our findings are broadly consistent with previous studies indicating left hemisphere specialization for dynamic control and predictable situations vs. right hemisphere specialization for impedance control and unpredictable situations, the specialized contributions of the two hemispheres being combined to different degrees in the right vs. left hands of right-handed vs. left-handed individuals.

Keywords: finger, handedness, motor control, movement

handedness occurs in approximately 96% of the human population (Annett 1998). Although referred to as handedness, the same phenomenon typically extends beyond movements of the hand to a general preference to use one side of the body instead of the other. One eye might be preferred for looking through a telescope, one arm might be preferred for hammering a nail, one foot might be preferred for kicking a ball, all typically on the same side of the body. Use of one side of the body over the other in a given situation presumably is preferred because of some underlying performance advantage on the preferred side.

Relatively few right/left differences in motor performance related to handedness have been identified in finger movements per se, however. One well-established difference is in tapping rate (Hammond et al. 1988; Heuer 2007; Todor and Kyprie 1980), and another is in the rate at which pegs can be moved on a pegboard (Noguchi et al. 2006; Triggs et al. 2000), both of which are faster in the dominant right hand of right-handed subjects. Compared with the nondominant left hand, the dominant right hand also has been found to show a smaller drop in force-stabilizing synergies among the fingers at the onset of a voluntary pulse or step increase in force produced by one finger (Zhang et al. 2006). Although one might expect right/left differences in performance to be present in individuated movements of the fingers themselves, right/left differences have not been found in the ability to individuate finger movements (Hager-Ross and Schieber 2000) or forces (Reilly and Hammond 2000).

Modern touchscreens afford new opportunities to examine movements of the fingers made to reach to or track small visual targets. To explore additional right/left asymmetries in finger movements, here we studied the motor performance of the right vs. the left index finger in a variety of simple tasks performed on a small touchscreen. Because left-handedness is not simply the mirror image of right-handedness (Annett 1975, 1998; Ashe and Ugurbil 1994; Przybyla et al. 2012; Wang and Sainburg 2006), we studied both right-handed and left-handed individuals.

METHODS

Subjects

Subjects with no neurological or orthopedic abnormalities that affected sensorimotor performance of the upper extremities participated in this study after giving written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Research Subjects Review Board of the University of Rochester. To quantify handedness, each subject completed the Edinburgh Inventory (Oldfield 1971). To compare clearly right-handed vs. left-handed subjects, we included subjects only if the absolute value of their laterality quotient was >50. The results presented here therefore include 17 strongly right-handed subjects [laterality quotients averaging 91.7 ± 9.9 (mean ± SD); 5 men and 12 women, 19–62 yr old] and 13 strongly left-handed subjects (laterality quotients averaging −78.1 ± 18.4; 3 men and 10 women, 21–63 yr old). For purposes of brevity, in right-handed subjects we will refer to the dominant right hand and the nondominant left hand and in left-handed subjects we will refer to the dominant left hand and the nondominant right hand.

Experimental Setup

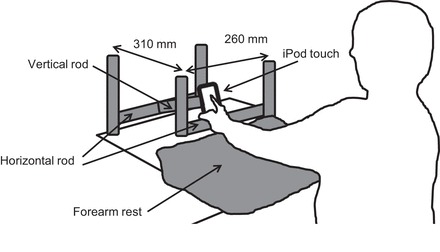

The experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 1. Behavioral tasks were performed on a custom-programmed iPod touch (Apple) mounted rigidly on rods that permitted the distance, height, and angle of the touchscreen to be adjusted to suit each subject prior to beginning any task performance (Fig. 1). Subjects sat comfortably, rested their forearm on a padded support, and interacted with the touchscreen using the index finger, while holding a horizontal rod (30-mm diameter) positioned in front of the torso with the thumb and middle, ring, and little fingers to stabilize the working hand.

Fig. 1.

Schematic drawing of experimental setup. Note that while touching the screen with the index finger the subject held a horizontal rod with the other fingers and the thumb, stabilizing the position of the hand.

The width and height of the iPod touch screen were 51.2 and 76.8 mm, respectively. In the horizontal dimension, rightward was considered positive; in the vertical dimension, upward was considered positive. Fingertip position was taken from the iPod touch operating system. During behavioral tasks, the position of the target and the position of the subject's fingertip on the touchscreen each were sampled at ∼100 Hz and stored to the iPod touch along with behavioral event markers indicating the start and stop of each trial, entry into and exit from any target, and when the subject's fingertip contacted or lost contact with the touchscreen. For all of the tasks, the background color of the touchscreen was black.

Experimental Procedure

Four behavioral tasks were performed by each subject, using the right hand and the left hand in an order randomized between subjects. For each task, mirror-image target locations and/or motion paths were used for the right and left hands. Data collection began after a small number of practice trials performed to familiarize the subject with the task. Figure 2 illustrates one round of each of the four tasks performed with the right hand and one round performed with the left hand for a single right-handed subject.

Fig. 2.

Example data from a single right-handed subject. One round of data is shown from the Target Task (A), the Center-Out Task (B), the Circle Tracking Task (C), and the Complex Tracking Task (D) performed with the left hand (left) and one round performed with the right hand (right). Open circles show target locations, and filled circles are the positions of subject's fingertip. In A, C, and D, simultaneous target and fingertip positions are connected by gray lines. In B, fingertip trajectories are indicated by dotted black lines, and the filled circle from each trial indicates the fingertip's position when it first contacted the target.

Target Task.

The Target Task assessed the subject's speed and accuracy in rapidly positioning the index fingertip (Fig. 2A). Each subject was instructed to use the index finger to touch a yellow circle (the target, 1.6-mm diameter) that suddenly appeared on the touch screen at one of 16 different locations on a 4 × 4 grid. The distance between targets was 12.8 mm horizontally and 12.8 mm vertically. Four potential target locations that might have been hidden by the subject's hand were not used. The remaining 12 target locations were varied in a pseudorandom block design. The subject was instructed to lift the index finger off the touchscreen and replace it as quickly and accurately as possible on the target. If the subject moved the index finger >1.6 mm while in contact with the touchscreen, the target turned red, indicating an error. Each round lasted until 36 successful trials had been acquired. Each subject completed three rounds with the right hand and three rounds with the left hand. During experiments, all trials were recorded regardless of the distance between a target and fingertip contact. However, when the distance between a target and the fingertip was longer than 18.1 mm, i.e., more than the distance from the center of the target to beyond a diagonally neighboring target, the trial was discarded as an outlier. Of the 36 × 3 = 108 trials performed by each hand, 4.1 ± 7.9 (mean ± SD) were discarded for the dominant right hand, 1.8 ± 3.4 for the nondominant left hand, 1.7 ± 2.2 for the dominant left hand, and 2.2 ± 2.9 for the nondominant right hand. If a subject did not touch the screen for 5 s, that round of data was discarded and another round was performed.

Center-Out Task.

The Center-Out Task assessed finger performance in a task that involved relatively linear motion of the fingertip in continuous contact with the touchscreen. Subjects were instructed to slide their index finger from a central home target to a peripheral target that appeared at one of eight locations arranged radially at 45° intervals on a circle of 17.6-mm radius from the center of the home target to the peripheral target centers (Fig. 2B). Three potential target locations that might have been occluded by the subject's hand were not used. Subjects were instructed to begin each trial by touching a light blue circle (the home target, 9.6-mm diameter) at the center of the touchscreen. After subjects held the home target for 1 s, a yellow circle (the target, also 9.6-mm diameter) appeared at one of the five peripheral locations. The subject was instructed to slide the index finger to the target as quickly and accurately as possible, while maintaining continuous contact with the touchscreen. Once within the peripheral target, the subject was required to maintain the index finger on the target for 1 s. Successful performance on each trial then was indicated to the subject by changing the background color from black to green. If the index finger reached and then overshot the target, or was lifted off the touchscreen at any time from the appearance of the target to the end of the 1-s hold period, the background color changed to red, indicating an error, and that trial was excluded from subsequent data analysis. To cue the subject to slide the fingertip back to the starting position, the background color changed to brown and the central light blue circle reappeared. Once the fingertip had been maintained in the starting position for 1 s, the background color changed back to black and the central circle color changed to dark blue to start the next trial. Each round continued until 20 successful trials (4 trials per target) were acquired. The order of balanced target presentation was randomized in each round. Each subject completed three rounds with each hand.

Tracking Tasks.

Two Tracking Tasks assessed finger performance in continuous pursuit tracking. Subjects used their index fingertip to track a target moving on the touchscreen. The target consisted of a yellow circle 1.6 mm in diameter moving at a constant speed of 16 mm/s and trailing a yellow tail 32 mm in length, indicating where the target had been. Subjects were instructed to follow the path laid out by the target with their index finger as accurately as possible while keeping the fingertip as close to the current target position as possible. Subjects were required to keep the fingertip in contact with the touchscreen for the duration of each trial. If the fingertip broke contact with the touchscreen during tracking, the trial immediately was aborted as an error and was excluded from subsequent data analysis. Another trial then was collected. In the Circle Tracking Task, the point moved in a circle 19.2 mm in radius, counterclockwise for the right hand and clockwise for the left hand (Fig. 2C), taking 7.54 s to complete one revolution. Because circular motion is completely predictable, in a second Complex Tracking Task the target moved in a path calculated as a sum of sines separately in the horizontal and vertical dimensions (Fig. 2D). For the right hand, the motion of the target was defined as

| (1) |

| (2) |

where t is time in seconds. For the left hand, the target's motion was the mirror image, reflected about the vertical center line of the touchscreen. Errors were declared only if the fingertip lost contact with the touchscreen. Each round consisted of 30 s of continuous tracking that began when the target appeared on the screen. Although the underlying path was constant for the Circle and Complex Tracking Tasks, the starting position at which the target initially appeared was randomized for each round. The subjects completed three rounds of each condition with each hand.

Data Analysis

All data were saved to disk on the iPod touch and subsequently downloaded to a personal computer for off-line analyses, which were performed in MATLAB (MathWorks). Fingertip position on the touchscreen as provided by the operating system of the iPod touch was the only kinematic data collected. We did not monitor forces exerted by the fingertip, nor did we monitor the posture or movement of the finger or more proximal limb segments or their joint angles. The iPod touch calculated fingertip position as the centroid of the contact area to a pixel resolution of 0.156 × 0.156 mm, more than an order of magnitude smaller than the fingertip. Although the compliance of the fingertip pulp might have resulted in a small shift of the centroid depending on the velocity of the fingertip across the screen, the position calculated by the iPod touch operating system was consistently beneath the fingertip, as required for standard use of such a device, as well as for our custom task control software.

For each successful trial of the Target Task, we calculated the horizontal (Δx) and vertical (Δy) distances between the center of the target and the position at which the fingertip touched the screen, the absolute values of these distances (|Δx|, |Δy|), and the Euclidean distance between the target and fingertip positions (d = ). We also measured 1) the reaction time from target appearance to fingertip liftoff, 2) the movement time from liftoff at the starting location to contact at the new target location, and 3) the response time, i.e., the sum of the reaction and movement times.

For each trial of the Center-Out Task, we calculated the same parameters as for the Target Task, using the fingertip's position when it first entered a target as its final position. We did not examine reaction and movement times in the Center-Out Task. We quantified the deviation of each trajectory from a straight line between the centers of the starting position and the target by integrating the area between the actual trajectory and that straight line.

For the Circle and Complex Tracking Tasks, given that fingertip position could not be sampled precisely at 100 Hz, both the target and fingertip position were resampled to simultaneous time series at 20-ms intervals to provide more precise correspondence between the target and fingertip positions at each time step. Δx, Δy, |Δx|, |Δy|, and d then were calculated at each time step. To quantify the angular relationship between the target and the fingertip, at each 20-ms time step we calculated the angle from the center of rotation/oscillation (the center of the touchscreen) to both the target and the fingertip and then calculated the cumulative angle of the target and of the fingertip over each trial, adding 360° when the angle passed from 359.9° to 0.0° and subtracting 360° when the angle passed from 0.0° to 359.9°. We used these cumulative angles to calculate phase lag as the average angular difference between the target and fingertip across all time steps in each trial. Because the target motions used for the right vs. left hand were mirror images of one another, phase lag typically was positive for one hand and negative for the other, and we therefore used the absolute value of phase lag for statistical comparisons. In the Complex Tracking Task, reversals of target direction often resulted in reversal between lag and lead as the fingertip that had been lagging behind the target was in front of the target when it reversed direction, only to lag behind again once the target had passed the fingertip. Averaging these episodes of phase lead together with lags tended to minimize the average phase difference. Therefore, we also computed the cross-correlation between the cumulative angle of the target and that of the fingertip and measured the maximum correlation coefficient and its time lag.

In addition, we noted that although sliding the fingertip across the touchscreen during the Circle and Complex Tracking Tasks usually was smooth, the fingertip occasionally “slipped,” producing a sudden jerk. To quantify these slips, we differentiated velocity, acceleration, and jerk from fingertip position. The horizontal and vertical components, as well as their vector sum, were examined for each of the three parameters. After preliminary inspection of these data, we defined a slip as an event in which the scalar value of jerk was ≥0.32 mm/s3.

Statistical Analysis

For the right and left hands of each subject in each task, we averaged each parameter across all successful trials in the three rounds performed. Group mean values of all parameters then were computed separately for the right and left hands of right-handed and left-handed subjects. Paired t-tests were used to detect differences between parameter means. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Target Task

In the Target Task, subjects used their index finger to touch 1.6-mm-diameter targets as quickly and accurately as possible. Figure 2A illustrates one round of the Target Task performed with the dominant right hand and one round performed with the nondominant left hand for a single right-handed subject. The location at which the fingertip touched the screen as detected by the iPod touch was typically within a few millimeters of the target center, with the distance between touch location and the target center averaging 3.9 ± 1.1 mm (mean ± SD) across all subjects. The fingertip, being several millimeters in width, thus typically covered the target on touchdown, eliminating any final visual feedback on accuracy and precision unless the distance between the target and the fingertip was unusually large.

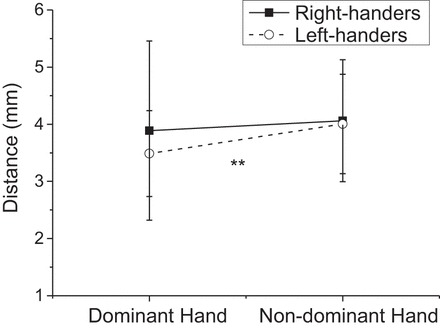

We evaluated the accuracy in the Target Task as the Euclidean distance between the center of the target and the location at which the fingertip touched the screen averaged across all targets and all trials for each hand. In right-handed subjects, although the dominant right hand tended to be slightly more accurate than the nondominant left hand (as for the subject illustrated in Fig. 2A), the trend did not reach significance. In contrast, left-handed subjects on average were more accurate in the Target Task with their dominant left hand than with their nondominant right hand. As shown in Fig. 3, the distance between the point of fingertip contact and the target was significantly less with the dominant left hand than with the nondominant right hand (P < 0.01). Both the horizontal (|Δx|, P < 0.05) and vertical (|Δy|, P < 0.001) components were smaller with the dominant left hand.

Fig. 3.

Mean values of the Euclidean distance between the target and fingertip (d = ) at touchdown in the Target Task for the dominant vs. nondominant hand of right-handed and left-handed subjects. Only in left-handers was the distance significantly less with the dominant hand. In this and all subsequent figures error bars represent 1 SD. **P < 0.01.

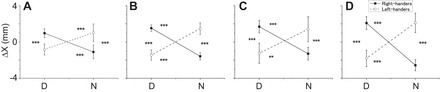

We also evaluated point of aim in the horizontal and vertical dimensions. Touch location was biased systematically in the horizontal dimension depending on whether the right vs. left hand was used, regardless of handedness. With either hand touchdown occurred on the right side of the target in some trials and the left side of the target in other trials (Fig. 2A), but, as illustrated in Fig. 4A, when using the right hand subjects touched the screen on average ∼1 mm to the right of the target's center (Δx > 0) and when using the left hand they touched on average ∼1 mm to the left (Δx < 0). Right-hand vs. left-hand differences in Δx were significant in both right-handed (P < 0.001) and left-handed (P < 0.001) subjects. In contrast to this horizontal bias, we found no systematic right-hand vs. left-hand bias in the vertical dimension (Δy).

Fig. 4.

Horizontal bias across tasks. Mean values of Δx for the dominant and nondominant hands are shown from the Target Task (A), Center-Out Task (B), Circle Tracking Task (C), and Complex Tracking Task (D) in right-handed and left-handed subjects. D, dominant hand; N, nondominant hand. Regardless of handedness, subjects tended to touch to the right of the target (Δx > 0) with the right index finger and to the left of the target (Δx < 0) with the left index finger. All pairwise comparisons were significant. Note that horizontal bias in general increases progressively from A to D. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

For both right- and left-handed subjects, the average reaction time of the dominant hand was significantly faster than that of the nondominant hand (P < 0.01; Fig. 5A). The movement time of the dominant left hand of left-handed subjects, however, was significantly slower than that of the nondominant right hand (P < 0.05; Fig. 5B), while there was no significant difference in the right-handed subjects. Consequently, for right-handed subjects the overall response time of the dominant right hand was significantly faster than that of the nondominant left hand (P < 0.01; Fig. 5C), because of the faster reaction time in the dominant right hand. In contrast, for left-handed subjects a significant difference in response time was not found because the opposing differences in reaction and movement times canceled one another in the total response time.

Fig. 5.

Mean values of reaction time (A), movement time (B), and response time (C) with the dominant and nondominant hands in the Target Task for right-handed and left-handed subjects. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Center-Out Task

In the Center-Out Task, rather than changing the position of the index fingertip in a single step as in the Target Task, subjects were required to slide the index finger from a center target to a peripheral target while keeping the fingertip continuously in contact with the touchscreen. Figure 2B illustrates one round of the Center-Out Task performed with the dominant right hand and one round performed with the nondominant left hand for a single right-handed subject. Initially, we evaluated the position of the index finger as soon as it entered the 9.6-mm-diameter peripheral target. A horizontal bias in point of aim was present at this end point of center-out movements, similar to that found in the step-tracking movements of the Target Task (P < 0.001; Fig. 4B). This bias was somewhat larger in the Center-Out Task in part because of the direction from which the fingertip entered the target in these center-out movements, which did not include positions occluded by the palm. As illustrated by the single-subject data presented in Fig. 2B, the dominant right hand, making more leftward than rightward movements, more often entered the target from the right, whereas the nondominant left hand more often entered the target from the left. Both right- and left-handed subjects therefore tended to enter on average ∼1.5 mm to the right of the peripheral target's center when using the right hand and on average ∼1.5 mm to the left when using the left hand. The average Δx in the Center-Out Task was systematically larger than in the Target Task for both the right and the left hand of both right-handed and left-handed subjects (P < 0.05).

Vertical end-point offsets, Δy, also were slightly larger in the Center-Out Task than in the Target Task (P < 0.05). In the Center-Out Task, both right- and left-handed subjects tended to end their center-out movements on average ∼0.7–1.5 mm below the center of peripheral targets. Again, this may have been due in large part to the fact that more of the targets used were entered from below than from above. The vertical end-point offset of right-handed subjects did not differ depending on the hand used, but using their dominant left hand, left-handed subjects ended closer to the target center in the vertical dimension than when using their nondominant right hand (P < 0.05; Fig. 6A) and closer to the target in the vertical dimension than right-handed subjects using their nondominant left hand (P < 0.001; Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Mean values of Δy (A), of the integrated area between the actual trajectory of the fingertip and the line between the home and peripheral target centers (B), and of response time (C) with the dominant and nondominant hands for the Center-Out Task in right-handed and left-handed subjects. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Another aspect of center-out movement performance is the degree to which the path of the fingertip lies close to a straight line between the centers of the home and peripheral targets. For each successful movement, we therefore integrated the area between the actual trajectory of the fingertip and the line between the home and peripheral target centers. This area increases with deviation from a straight-line path but is positive regardless of the side of the line on which the trajectory lies. In right-handed, but not left-handed, subjects this area was smaller on average when using the dominant right hand than when using the nondominant left hand (P < 0.01; Fig. 6B). For left-handed subjects, the area when using either hand was similar to that with the right hand of right-handed subjects. The nondominant left hand of right-handed subjects thus showed the largest deviations from straight-line trajectories. Right-handed subjects, but not left-handed subjects, also had shorter response times—from appearance of the peripheral target until the fingertip entered the target—with their dominant right hands (P < 0.05; Fig. 6C).

Circle Tracking Task

In the Circle Tracking Task, subjects were required to keep their fingertip in contact with the touchscreen while tracking a 1.6-mm-diameter target as it moved at constant speed in a circular path. Figure 2C shows the target location and the simultaneous fingertip position for one subject during one trial of circle tracking with each hand. For the left hand the target moved clockwise and for the right hand counterclockwise. On average, subjects kept their fingertips ∼10–11 mm from the target center, primarily lagging behind the current position of the target. The fingertip did not follow the circle traced by the target precisely, however. The right fingertip tended to track slightly down and to the right of the target circle, whereas the left fingertip tended to be slightly down and to the left. Consequently, as seen in the Target Task (Fig. 4A) and Center-Out Task (Fig. 4B) for both right-handed (P < 0.001) and left-handed (P < 0.01) subjects, the average position of the right fingertip tended to be ∼1 mm to the right of the target and the left index fingertip ∼1 mm to the left (Fig. 4C).

Angular measures of tracking were similar in the dominant and nondominant hands of both right- and left-handed subjects during the Circle Tracking Task. No significant differences were found for absolute phase lag, maximal correlation coefficient, or time lag. Notably, however, for all subjects the maximal correlation coefficient was essentially 1 (all individual trials had values > 0.9985) and time lag was 0.00 s (also on all individual trials). These observations suggest that although subjects tracked with appreciable phase lag (absolute value across subjects and hands: 30 ± 13°), they accurately predicted the circular motion.

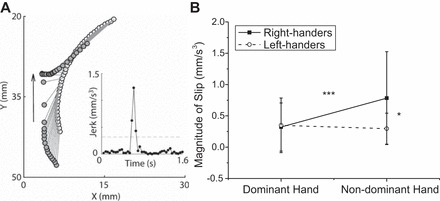

In the Circle Tracking Task the target moved at a constant speed, while the direction of motion varied smoothly in a predictable circular path. In examining the motion of the fingertip as a function of time, we noted instances in which the fingertip slipped across the touchscreen. An example slip is shown in Fig. 7A (arrow). The fingertip suddenly deviated from its approximately circular path, accelerating tangentially. Once the slip had been arrested, the fingertip returned to tracking the circular target motion with appropriate speed and direction.

Fig. 7.

Slips. A: example of a slip during the Circle Tracking Task. The fingertip was following the motion of the circle initially, though somewhat below and to the left of the target, but then suddenly accelerated tangentially (arrow). After this motion was arrested, the fingertip returned to tracking the circle. Inset: scalar jerk magnitude as a function of time for the same data, with a dashed line indicating the value of 0.32 mm/s3 used as the criterion to include such events as slips. B: mean values of magnitude of slip with dominant and nondominant hands for the Circle Tracking Task in right-handed and left-handed subjects. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Such slips could have resulted from variation either in the forces produced by the subject's fingertip or in the friction between the moving fingertip and the touchscreen. Controlling the fingertip when such unexpected irregularities are encountered requires dynamic control of both the normal force keeping the fingertip in contact with the screen and the tangential force moving the fingertip across the screen (Johansson and Flanagan 2009). We therefore quantified both the incidence and magnitude of these slips. Initially, we examined the velocity, acceleration, and jerk differentiated successively from fingertip position data as separate horizontal and vertical components, as well as their vector sum. After preliminary evaluation, we defined a movement irregularity in which the vector magnitude of jerk exceeded a threshold of 0.32 mm/s3 as a “slip” (Fig. 7A, inset).

The incidence of slips was similar in the right and left hands of both right-handed and left-handed subjects. The magnitude of slips in terms of peak jerk, however, while being similar in the right hand of right-handed subjects and in both hands of left-handed subjects, was particularly large in the nondominant left hand of right-handed subjects (Fig. 7B). Although the difference between the left hands of right- vs. left-handed subjects was not significant, slips in the nondominant left hand of right-handed subjects had significantly higher jerk on average than those in the right hand of either left-handed (P < 0.05) or right-handed (P < 0.001) subjects.

Complex Tracking Task

In the Complex Tracking Task, subjects continuously tracked a target that moved as a different sum of sines in the horizontal and vertical dimensions. While other requirements remained the same as in the Circle Tracking Task, here the motion of the target was less predictable. Figure 2D shows the target location and the simultaneous fingertip position for one subject during one trial of complex tracking with each hand. As in the Circle Tracking Task, the subject's fingertip typically remained ∼9–10 mm from the center of the target. And again, as seen in the other three tasks, both right-handed and left-handed subjects showed a systematic bias in horizontal position depending on the hand used, the fingertip tending to be slightly to the right of the target path on average when using the right hand and slightly to the left when using the left hand (P < 0.001; Fig. 4D). In the Complex Tracking Task, this horizontal bias was slightly larger (≥2 mm on average) than in any of the other tasks. (An exception, however, was the horizontal bias of the dominant left hand of left-handed subjects, which was not significantly larger during Complex Tracking than during Circle Tracking or in the Center-Out Task.) The nondominant left hand of right-handed subjects showed the largest horizontal bias during Complex Tracking, significantly larger than the dominant left hand of left-handed subjects (P < 0.05).

In the Complex Tracking Task, although absolute phase lag was not different among hands (absolute value across all subjects and hands: 10 ± 5°), the maximal correlation coefficient and its time lag showed some small but significant differences (Fig. 8). The maximal correlation coefficient of the dominant right hand was slightly higher than that of the dominant left hand (0.97 ± 0.01 vs. 0.96 ± 0.02, P < 0.05), but it was the nondominant left hand that showed the shortest time lag, though this was significantly different only from that of the dominant right hand (0.12 ± 0.09 s vs. 0.20 ± 0.14 s, P < 0.05). These observations suggest that although the dominant right index finger replicated the target path slightly better than the dominant left index finger, the nondominant left index finger followed the complex target motion more closely in time than the dominant right index finger.

Fig. 8.

Angular cross-correlations during the Complex Tracking Task. Cross-correlations were computed between the angle of the target and that of the fingertip relative to the center of target oscillation. A: maximal correlation coefficients. B: time lags of the maximal correlation coefficients. *P < 0.05.

We also analyzed slips during the Complex Tracking Task. Slips occurred at about the same frequency (∼0.14 slips/s) on average during the Complex Tracking Task and during the Circle Tracking Task, but, in contrast to the Circle Tracking Task, during the Complex Tracking Task no significant differences in the magnitude of slips were present between the right and left hands or between right-handed and left-handed subjects.

DISCUSSION

We explored right/left differences in four simple tasks performed on a small touchscreen. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that some of the differences we found (or failed to find) might have been related to unmonitored factors such as the forces exerted by the fingertip or the posture of more proximal joints, the four tasks revealed a variety of right/left differences in the index finger movements of right-handed subjects, left-handed subjects, or both. In addition, we found a right/left difference in horizontal bias across all tasks unrelated to handedness.

Target Task, Speed-Accuracy Trade-Off, and Hemispheric Specialization

In the present Target Task, subjects touched targets as quickly and accurately as possible. The dominant left hand was more accurate than the nondominant right hand in left-handed subjects, but no right/left accuracy difference was found in right-handed subjects (Fig. 3). Both right- and left-handed subjects reacted faster with their dominant hand, but because in left-handed subjects the dominant left hand moved more slowly than the nondominant right hand, only right-handed subjects had faster total response times with the dominant right hand than with the nondominant left hand (Fig. 5).

Previous studies have suggested that in right-handed subjects the right hemisphere may be specialized for position control, giving the nondominant left hand greater positional accuracy than the dominant right hand (Haaland et al. 2004; Sainburg 2005). This greater positional accuracy appears to be restricted, however, to conditions when target locations are unpredictable and no visual feedback is available (Przybyla et al. 2013) or when unpredictable loads are applied (Bagesteiro and Sainburg 2003). None of these specific conditions was used in the present study.

The differences we did observe might be related, then, to the classic speed-accuracy trade-off (Fitts 1954). The general principle that requiring greater accuracy is associated with slower movements can be biased by instructions. When subjects were instructed to emphasize either speed or accuracy, the instruction to emphasize speed was found to elicit faster but less accurate movements, whereas the instruction to emphasize accuracy elicited slower but more accurate movements (Carson et al. 1993). Our subjects were instructed to touch the target as quickly and as accurately as possible. Whether speed or accuracy predominated therefore might reflect not different task instructions or requirements but instead differences in hemispheric specialization or strategies. In right-handed subjects the dominant left hemisphere may have emphasized speed, whereas in left-handed subjects the dominant right hemisphere may have emphasized accuracy.

Indeed, a number of other studies examining aiming tasks (largely in right-handed individuals) have reported shorter reaction times with the nondominant left hand but shorter movement times with the dominant right hand (Barthélémy and Boulinguez 2002; Bradshaw et al. 1990; Carson et al. 1993; Elliott and Carson 2000; Roy et al. 1994; van Doorn 2008). Barthélémy and Boulinguez (2002) further reported that faster reaction time with the left hand was found only when attention had to be disengaged and/or shifted to a new location. Their observations suggested a somewhat different axis of hemispheric specialization. The faster reaction time observed in the left hand of right-handed subjects may represent an advantage of the nondominant right hemisphere in preparing movement to a specific, newly attended spatial location. Conversely, the faster movement time observed in the right hand of right-handed subjects may represent an advantage of the dominant left hemisphere in execution of goal-directed movements resulting from specialization for processing perceptual and/or motor information during ongoing movement. In the present Target Task, however, right-handed subjects reacted faster with the dominant right hand than with the nondominant left hand, while their movement times and accuracy were not significantly different with the right vs. left hand. Our results for right-handed subjects thus were not fully consistent with this interpretation either, perhaps because the small size of the touchscreen used in the present study required less shifting of spatial attention.

Center-Out Task and Trajectory Curvature

In the present Center-Out Task, subjects slid their index fingers on the surface of the touchscreen from a central home target to different peripheral targets. In the vertical dimension, the index finger of the dominant left hand entered the circular targets closer to their centers than that of either the nondominant right hand or the dominant right hand (Fig. 6A). The dominant left index finger thus arrived in targets more from the side than from above or below. Nevertheless, it was the nondominant left hand that showed the greatest trajectory curvature (Fig. 6B).

In rapid reaching movements using the arm, such curvature likewise has been found to be greatest in the nondominant left arm (Przybyla et al. 2012). In addition to showing greater curvature than the dominant right arm, the nondominant left arm of right-handed subjects showed greater curvature than either arm of left-handed subjects. Within left-handed subjects, the nondominant right arm showed greater curvature than the dominant left arm, though the difference was smaller than that found in right-handed subjects. In these reaching movements, the lesser degree of curvature found in the dominant arm is thought to reflect specialization of the dominant hemisphere for predictive control of limb dynamics (Bagesteiro and Sainburg 2002; Sainburg 2002, 2005; Sainburg and Kalakanis 2000; Yadav and Sainburg 2014a, 2014b). A similar asymmetry of hemispheric specialization may have resulted in the higher curvature of the nondominant left index finger found in the present right-handed subjects, while the lower inertial loads of finger compared with the arm may have precluded our observing any differences in left-handed subjects.

Path Predictability in Continuous Tracking Tasks, Slips, and Angular Correlation

Although not part of the experimental design, we noted that during both the Circle Tracking Task and the Complex Tracking Task the subject's index finger occasionally slipped on the touchscreen. Slips presumably resulted from an unanticipated mismatch between the moving friction of the fingertip (which would be proportional to the normal force exerted by the fingertip on the touchscreen) and the force being exerted tangentially to move the fingertip across the touchscreen. Slips thus could occur either because the fingertip met a sudden drop in friction with no change in tangential force exerted or because the fingertip met an increase in friction and responded with an increase in tangential force until the friction suddenly was overcome. Although our data do not distinguish these possibilities, in either case slips required sudden unanticipated arrest, followed promptly by return to the path being tracked, i.e., a dynamic control process.

We found no difference in the frequency of slips in the right vs. left hand of either right- or left-handed subjects, but during the Circle Tracking Task slip magnitude (peak jerk) was significantly larger in the nondominant left hand than in the dominant right hand. This suggests that the dominant right hand dealt more readily with unexpected inconsistencies in friction and/or arrested slips more quickly. In contrast, left-handed subjects showed no significant difference in slip magnitude between their dominant left hands and nondominant right hands, both of which showed slip magnitudes similar to those of the dominant right hand of right-handed subjects. Thus it was the nondominant left hand of right-handed subjects that showed comparatively large slips.

Interestingly, during the Complex Tracking Task slip magnitude was not different between the right and left hands of either right- or left-handed subjects. This difference between tasks suggests differences in neural control when the motion of the target is highly predictable vs. relatively unpredictable. Correlation between target and fingertip angles in the present study confirmed that subjects accurately predicted the target's motion in the Circle Tracking Task and were less able to predict the target's motion in the Complex Tracking Task.

Previous studies have shown that when unpredictable inertial loads are imposed on reaching movements, the nondominant left arm maintains higher final position accuracy than the dominant right arm (Bagesteiro and Sainburg 2003), consistent with a right hemisphere specialization for impedance control (Yadav and Sainburg 2014a, 2014b). In addition to better impedance control, the right hemisphere specialization might also involve an advantage in dealing with relatively unpredictable situations (MacNeilage et al. 2009; Sainburg 2014). The present findings do not fit simply with these previous observations. Unpredictable slips during Circle Tracking were lower in magnitude for the dominant right index finger than for the nondominant left, and during Complex Tracking, although the nondominant left index finger followed the target more closely in time, the dominant right index finger showed higher correlation with the target motion than the dominant left index finger. These differences may reflect the smaller inertia of the index finger and lower speeds used in the present studies compared with the larger inertia of the arm and higher speeds studied in previous work.

Horizontal Bias

In all four tasks, we consistently found a systematic bias in the horizontal position at which the index fingertip touched the screen relative to the center of the target depending on whether the right or left hand was used, independent of handedness (Fig. 4). When using the right hand subjects touched the screen on average slightly to the right of the target, and when using the left hand they touched slightly to the left. This horizontal bias was observed consistently in both right-handed and left-handed subjects in all four tasks.

Typically when using a touchscreen, the entire upper extremity is free to move. Even when touching the screen with the tip of a single finger, simple observation shows that much of the motion of the fingertip across the screen is produced by rotation at joints as far proximal as the shoulder. In all of the present tasks, however, we had subjects stabilize the position of the hand by holding a horizontal rod with the other digits while the index finger moved, thereby constraining the motion of the fingertip to be produced relatively selectively by rotation at the joints of the index finger itself. When subjects used their right index finger, therefore, the right hand was to the right side of the touchscreen center, and when they used their left index finger the left hand was to the left. Stabilizing the hand therefore may have produced a mechanical bias, because placing the index finger farther from the hand would have required more energy.

Another possibility has to do with visual feedback. If subjects touched to the left of the target when using the right index finger, seeing the target would have been more difficult than if the index finger touched to the right of the target. The converse would apply when using the left index finger. The horizontal bias therefore might also have helped the subjects maintain vision of the target as much as possible.

Conclusions

Each of the four simple tasks performed on a small touchscreen with relatively isolated movements of the index finger revealed a significant right/left difference in right-handed subjects, left-handed subjects, or both. Performance by left-handed subjects was not a mirror image of performance by right-handed subjects. Further studies will be needed to determine the extent to which the right/left differences in finger movements identified here result from differences in dynamic vs. impedance control, predictable vs. unpredictable situations, and possibly other factors (MacNeilage et al. 2009; Sainburg 2014), all combining to different degrees in the performance of the dominant right hand, the nondominant left hand, the dominant left hand, and the nondominant right hand.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grants R01 NS-079664 and R01 NS-065902.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: T.A., G.R., and M.H.S. conception and design of research; T.A. and G.R. performed experiments; T.A. and G.R. analyzed data; T.A. and M.H.S. interpreted results of experiments; T.A. and M.H.S. prepared figures; T.A. and M.H.S. drafted manuscript; T.A. and M.H.S. edited and revised manuscript; T.A., G.R., and M.H.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Andrea Moore for technical assistance, Marsha Hayles for editorial comments, and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

REFERENCES

- Annett M. Hand preference and the laterality of cerebral speech. Cortex 11: 305–328, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annett M. Handedness and cerebral dominance: the right shift theory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 10: 459–469, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe J, Ugurbil K. Functional imaging of the motor system. Curr Opin Neurobiol 4: 832–839, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagesteiro LB, Sainburg RL. Handedness: dominant arm advantages in control of limb dynamics. J Neurophysiol 88: 2408–2421, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagesteiro LB, Sainburg RL. Nondominant arm advantages in load compensation during rapid elbow joint movements. J Neurophysiol 90: 1503–1513, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthélémy S, Boulinguez P. Manual asymmetries in the directional coding of reaching: further evidence for hemispatial effects and right hemisphere dominance for movement planning. Exp Brain Res 147: 305–312, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw JL, Bradshaw JA, Nettleton NC. Abduction, adduction and hand differences in simple and serial movements. Neuropsychologia 28: 917–931, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson RG, Goodman D, Chua R, Elliott D. Asymmetries in the regulation of visually guided aiming. J Mot Behav 25: 21–32, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D, Carson RG. Moving into the new millennium: some perspectives on the brain in action. Brain Cogn 42: 153–156, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitts PM. The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement. J Exp Psychol 47: 381–391, 1954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaland KY, Prestopnik JL, Knight RT, Lee RR. Hemispheric asymmetries for kinematic and positional aspects of reaching. Brain 127: 1145–1158, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager-Ross CK, Schieber MH. Quantifying the independence of human finger movements: comparisons of digits, hands and movement frequencies. J Neurosci 20: 8542–8550, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond G, Bolton Y, Plant Y, Manning J. Hand asymmetries in interresponse intervals during rapid repetitive finger tapping. J Mot Behav 20: 67–71, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer H. Control of the dominant and nondominant hand: exploitation and taming of nonmuscular forces. Exp Brain Res 178: 363–373, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson RS, Flanagan JR. Coding and use of tactile signals from the fingertips in object manipulation tasks. Nat Rev Neurosci 10: 345–359, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeilage PF, Rogers LJ, Vallortigara G. Origins of the left & right brain. Sci Am 301: 60–67, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi T, Demura S, Nagasawa Y, Uchiyama M. An examination of practice and laterality effects on the Purdue Pegboard and Moving Beans with Tweezers. Percept Mot Skills 102: 265–274, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9: 97–113, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybyla A, Coelho CJ, Akpinar S, Kirazci S, Sainburg RL. Sensorimotor performance asymmetries predict hand selection. Neuroscience 228: 349–360, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybyla A, Good DC, Sainburg RL. Dynamic dominance varies with handedness: reduced interlimb asymmetries in left-handers. Exp Brain Res 216: 419–431, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly KT, Hammond GR. Independence of force production by digits of the human hand. Neurosci Lett 290: 53–56, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy EA, Kalbfleisch L, Elliott D. Kinematic analyses of manual asymmetries in visual aiming movements. Brain Cogn 24: 289–295, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainburg RL. Evidence for a dynamic-dominance hypothesis of handedness. Exp Brain Res 142: 241–258, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainburg RL. Handedness: differential specializations for control of trajectory and position. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 33: 206–213, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainburg RL. Convergent models of handedness and brain lateralization. Front Psychol 5: 1092, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainburg RL, Kalakanis D. Differences in control of limb dynamics during dominant and nondominant arm reaching. J Neurophysiol 83: 2661–2675, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todor JI, Kyprie PM. Hand differences in the rate and variability of rapid tapping. J Mot Behav 12: 57–62, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triggs WJ, Calvanio R, Levine M, Heaton RK, Heilman KM. Predicting hand preference with performance on motor tasks. Cortex 36: 679–689, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doorn RR. Manual asymmetries in the temporal and spatial control of aimed movements. Hum Mov Sci 27: 551–576, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Sainburg RL. Interlimb transfer of visuomotor rotations depends on handedness. Exp Brain Res 175: 223–230, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav V, Sainburg RL. Handedness can be explained by a serial hybrid control scheme. Neuroscience 278: 385–396, 2014a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav V, Sainburg RL. Limb dominance results from asymmetries in predictive and impedance control mechanisms. PLoS One 9: e93892, 2014b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Sainburg RL, Zatsiorsky VM, Latash ML. Hand dominance and multi-finger synergies. Neurosci Lett 409: 200–204, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]