Abstract

The production of functional male gametes is dependent on the continuous activity of germline stem cells. The availability of a transplantation assay system to unequivocally identify male germline stem cells has allowed their in vitro culture, cryopreservation, and genetic modification. Moreover, the system has enabled the identification of conditions and factors involved in stem cell self-renewal, the foundation of spermatogenesis, and the production of spermatozoa. The increased knowledge about these cells is also of great potential practical value, for example, for the possible cryopreservation of stem cells from boys undergoing treatment for cancer to safeguard their germ line.

Male germline stem cells, called spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) in post-natal mammals, are the foundation of spermatogenesis (the process for spermatozoa production) and, together with oocytes from females, are essential for species continuity. SSCs reside on the basement membrane of the seminiferous tubule in the testis and are almost completely surrounded by somatic Sertoli cells, which form a microenvironment or niche. Within the niche, growth factors and extracellular signals regulate the fate decisions of SSCs either to self-renew or to form daughter cells that will begin the complex differentiation process of spermatogenesis, resulting in mature spermatozoa after about 35 days in the mouse and 64 days in the human (1, 2). The timing of sequential steps in spermatogenesis is tightly regulated by genes of the germ cell, and Sertoli cells support the differentiation process.

The first step in spermatogenesis is the fate decision of an SSC to produce daughter cells committed to differentiation. There are no known unique biochemical or phenotypic markers for distinguishing SSCs from their initial daughters, called undifferentiated spermatogonia. This limitation has hampered studies on the biology of SSCs. However, in 1994 a spermatogonial stem cell assay was reported in mice that identified SSCs by their ability to generate a colony of spermatogenesis after transplantation to the seminiferous tubules of a recipient male. If a sufficient number of SSCs were transplanted, progeny displaying the donor haplotype were produced by the recipient (3). Subsequent studies showed that SSCs of all mammalian species examined (e.g., rat, rabbit, dog, pig, cow, baboon, and human) would colonize the seminiferous tubules of immunodeficient mice and generate colonies of stem cells and cells that appeared to be early differentiating daughter spermatogonia (1, 3). These results indicate that signals in the stem cell and niche must have been highly conserved among mammalian species during the course of the 100 million years since the phylogenetic divergence of mice and humans. Moreover, unlike mature spermatozoa, which are difficult to cryopreserve and require species-specific procedures, SSCs from all of the species examined can be cryopreserved for long periods with common techniques used for somatic cells (1).

The availability of the transplantation assay made it possible to study SSCs in culture (4) and has led to the continuous replication of mouse SSCs in vitro (5). Glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) was identified as a critical factor in vivo for the replication of spermatogonia (6). In vitro studies using serum-free culture medium demonstrated that GDNF is the primary growth factor supporting mouse SSC self-renewal (7). The development of culture methods has led to a wide range of studies on SSCs in vitro (8, 9). GDNF binding and signaling occur through GDNF-family receptor α1 (GFRα1) and the Ret receptor on SSCs and undifferentiated spermatogonia. Although both GFRα1 and Ret are surface molecules, they have not been ideal for purifying SSCs from testes, resulting in, at best, a 1.75-fold enrichment (10, 11). Selection with antibodies to thymus cell antigen 1, however, produces a 5- to 10-fold enrichment of SSCs, generating excellent cell populations for studies on SSCs (10, 12).

In the presence of GDNF, SSCs grow on feeder cells as islands or clumps of cells. If GDNF is removed, the clump cells begin to grow in chains resembling the initial stages of stem cell differentiation, as seen in vivo (2, 12–15). Thus, GDNF appears to be a primary regulator of the self-renewal versus differentiation fate decision for mouse and rat SSCs (7, 14), and it is probably a conserved self-renewal signal for all mammalian SSCs (7, 14, 15). Similar to embryonic stem cells (ESCs), SSCs grow in vitro on feeder cells in islands or clumps, and they stain positive for POU domain class 5 transcription factor 1 (Oct 3/4) and alkaline phosphatase (7). These observations suggested that SSCs might be pluripotent. However, whereas ESCs readily generate teratocarcinomas when transplanted in vivo, SSCs do not form tumors under similar conditions (3, 7). Whether the normal adult SSC can be induced to become pluripotent remains controversial.

The availability of a functional transplantation assay and a culture system that allows long-term replication of SSCs made it possible to examine intracellular signals that influence self-renewal and differentiation in vitro in a rigorous manner that is not available for most adult stem cells (16). These studies demonstrated that Oct 3/4 and SRY–box-containing gene 2 (Sox 2), which regulate Nanog, are expressed in SSCs. However, Nanog, the key determinant of ESC self-renewal and pluripotency, is not expressed in SSCs (16). Therefore, the signaling mechanisms that maintain self-renewal in SSCs and ESCs are different. These studies also demonstrated that the expression of genes for three transcription factors, B cell CLL/lymphoma 6 member B (Bcl6b), Ets-related molecule (Erm), and LIM homeobox 1 (Lhx1), is highly regulated by GDNF in vitro. Functional SSC transplantation assays confirmed the importance of Bcl6b, and it is therefore likely that Erm and Lhx1 influence SSC self-renewal (16). Erm expression in Sertoli cells is also believed to affect niche function (17). Other studies indicate an important role in SSC self-renewal for promyelocyte leukemia zinc-finger factor (Plzf ), TATA-binding protein-associated factor 4b (TAF4b), and perhaps Nanos 2 (NOS2) (18–20), but GDNF does not regulate these genes (16). Therefore, the mechanism of their action is unclear.

Although the culture and transplantation systems have made it possible to study SSC self-renewal, the absence of similar systems for germ cell differentiation stages of spermatogenesis has complicated the examination of regulatory mechanisms for this process. Moreover, the intricate three-dimensional structural organization of spermatogenesis has compounded the problem. In addition to surrounding the stem cell to provide a regulatory niche, the Sertoli cell extends ~90 μm from the basement membrane to the lumen of the seminiferous tubule, contacting and surrounding germ cells in many stages of differentiation. Furthermore, an individual germ cell may associate with more than one Sertoli cell (2, 13). Near the basement membrane are early stages of spermatogonia, including SSCs and undifferentiated spermatogonia. These cells are GDNF-responsive but do not display the c-Kit tyrosine kinase receptor on their surface (7, 8). A critical step to initiate their conversion to differentiating spermatogonia is probably a signal to express c-kit. Then, the binding of the stem cell factor Kit ligand, from Sertoli cells to the c-Kit receptor, could initiate the remaining differentiation pathway. This step from undifferentiated to differentiating spermatogonia appears to be a critical regulatory point in spermatogenesis. The timing of subsequent steps in differentiation is controlled by germ cell genes (1). An exciting new area of spermatogenesis regulation involves small interfering RNAs, evolutionarily conserved molecules that inhibit gene expression and are present in germ cells throughout spermatogenesis (21).

The ability to recover, cryopreserve, culture, and transplant SSCs has stimulated new approaches to understanding the biology of these important cells. It has also provided an opportunity for practical and medical applications of SSCs and makes individual male germ lines potentially immortal. The continuous long-term increase in the number of SSCs in culture now allows for the introduction of genetic modifications through the germ line with methods developed for somatic cells and ESCs. Potentially, any genetic manipulation, including targeted gene knockout or correction, can be used in all mammalian species for which culture conditions are developed. However, in humans, clinical and ethical limitations will be critically important.

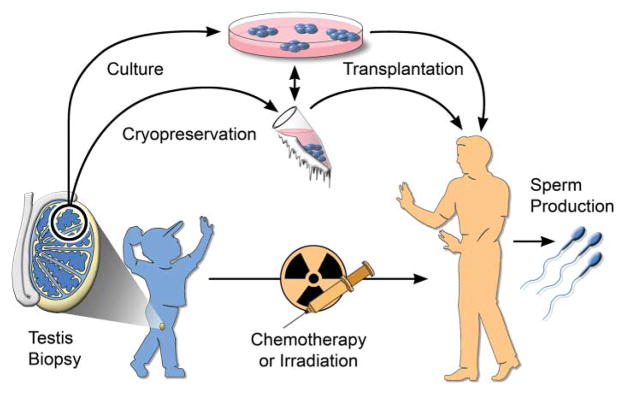

Stem cell recovery and cryopreservation may be applicable to all mammalian species and could be used to preserve the male germ line of valuable livestock animals, companion animals, and endangered species. Perhaps the most provocative and potentially valuable medical application of SSC research is for prepubertal boys undergoing chemotherapy or irradiation for cancer (9). In many cases, the SSCs are destroyed as a side effect of treatment, and the patient is left infertile. It is possible to obtain a testicular biopsy and cryopreserve a cell suspension produced from the biopsy. This cell suspension containing SSCs could then be transplanted back into the patient’s testes at any age after treatment, potentially resulting in recolonization of the testes and spermatozoa production (Fig. 1). Development of culture techniques for human SSCs will facilitate this important medical application.

Fig. 1.

Male germline stem cell preservation. Before treatment for cancer by chemotherapy or irradiation, a boy could undergo a testicular biopsy to recover stem cells. The stem cells could be cryopreserved or, after development of the necessary techniques, could be cultured. After treatment, the stem cells would be transplanted to the patient’s testes for the production of spermatozoa.

There are many possible future directions to pursue. Three particularly important areas include (i) the further definition of factors and signals that support self-renewal of SSCs, relative to those that initiate differentiation in order to provide a better understanding of this fate decision; (ii) the extension of the serum-free culture system to other species, including domestic animals, endangered species, and humans to confirm that self-renewal signals are conserved among mammals and for relevant applications; and (iii) the development of methods to allow in vitro differentiation of stem cells to provide mature spermatozoa, which would be enormously valuable in understanding the complex process of spermatogenesis and would have great practical use. These advances will dramatically expand the applications of SSCs.

Acknowledgments

I thank R. Behringer, R. Davies, H. Kubota, J. Oatley, and J. Schmidt for valuable comments on and contributions to the manuscript; M. Avarbock, C. Freeman, R. Naroznowski, and C. Pope for assistance in experiments; J. Hayden for help with photography and figures; and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant HDO44445) and the Robert J. Kleberg Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation for financial support.

References and Notes

- 1.Brinster RL. Science. 2002;296:2174. doi: 10.1126/science.1071607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russell LD, Ettlin RA, Sinha Hikim AP, Clegg ED. Histological and Histopathological Evaluation of the Testis. Cache River; Clearwater, FL: 1990. pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinster RL, Avarbock MR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagano M, Avarbock MR, Leonida EB, Brinster CJ, Brinster RL. Tissue Cell. 1998;30:389. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(98)80053-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, et al. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:612. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meng X, et al. Science. 2000;287:1489. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407063101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oatley JM, Brinster RL. Methods Enzymol. 2006;419:259. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)19011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubota H, Brinster RL. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2:99. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebata KT, Zhang X, Nagano MC. Mol Reprod Dev. 2005;72:171. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buageaw A, et al. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:1011. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:722. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.029207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Rooij DG. Int J Exp Pathol. 1998;79:67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.1998.t01-1-00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryu BY, Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506970102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamra FK, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508780102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oatley JM, Avarbock MR, Teleranta AI, Fearon DT, Brinster RL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603332103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen C, et al. Nature. 2005;436:1030. doi: 10.1038/nature03894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong MD, Jin Z, Xie T. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.105855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falender AE, et al. Genes Dev. 2005;19:794. doi: 10.1101/gad.1290105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki A, Tsuda M, Saga Y. Development. 2007;134:77. doi: 10.1242/dev.02697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin H. Science. 2007;316:397. doi: 10.1126/science.1137543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]