Abstract

Background

A prior randomized controlled trial of social media exposure at Circulation determined that social media did not increase 30‐day page views. Whether insufficient social media intensity contributed to these results is uncertain.

Methods and Results

Original article manuscripts were randomized to social media exposure compared with no social media exposure (control) at Circulation beginning in January 2015. Social media exposure consisted of Facebook and Twitter posts on the journal's accounts. To increase social media intensity, a larger base of followers was built using advertising and organic growth, and posts were presented in triplicate and boosted on Facebook and retweeted on Twitter. The primary outcome was 30‐day page views. Stopping rules were established at the point that 50% of the manuscripts were randomized and had 30‐day follow‐up to compare groups on 30‐day page views. The trial was stopped for futility on September 26, 2015. Overall, 74 manuscripts were randomized to receive social media exposure, and 78 manuscripts were randomized to the control arm. The intervention and control arms were similar based on article type (P=0.85), geographic location of the corresponding author (P=0.33), and whether the manuscript had an editorial (P=0.80). Median number of 30‐day page views was 499.5 in the social media arm and 450.5 in the control arm; there was no evidence of a treatment effect (P=0.38). There were no statistically significant interactions of treatment by manuscript type (P=0.86), by corresponding author (P=0.35), by trimester of publication date (P=0.34), or by editorial status (P=0.79).

Conclusions

A more intensive social media strategy did not result in increased 30‐day page views of original research.

Keywords: altmetrics, randomized control trial, social media

Subject Categories: Health Services

Introduction

Many medical journals use social media strategies. Social media metrics, known as altmetrics, can be used to predict the future impact of a manuscript1, 2, 3, 4; however, it remains unclear whether social media exposure itself can serve as a driver of manuscript impact.

We previously conducted a randomized controlled trial at the journal Circulation to test whether social media exposure could increase the number of times an original article was viewed.5 There was no difference between the control and intervention groups. The trial, however, was limited by the journal's relatively small social media following at the time of the clinical trial. Consequently, it was unclear whether these findings could be generalizable to journals with larger social media followings or those using more intensive social media strategies.

We augmented the design of our initial study and recapitulated our randomized controlled trial of social media exposure at Circulation. This time, a higher intensity of social media was used, including a larger social media following, triplicate posting, retweeting, and the boosting of posts to gain farther reach. In this paper, we report on these findings.

Methods

Overall Design

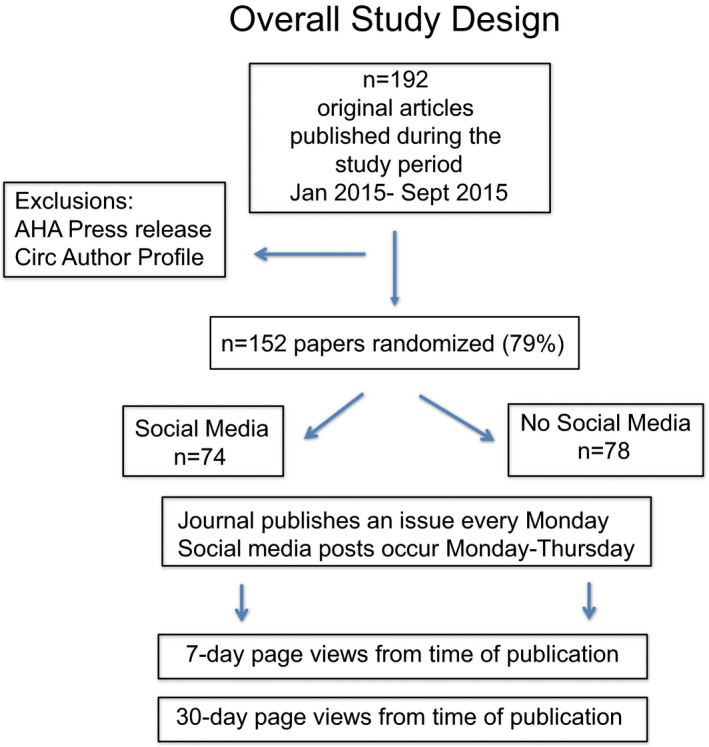

This study was a randomized controlled trial of original articles published in Circulation from January 13, 2015, through September 22, 2015. To differentiate ourselves from our prior trial and to overcome a key limitation of the size of our following during that trial, we actively built a larger base of followers using advertising and capitalizing on the publicity garnered from our first trial. In the specified time period, 192 original articles were published. Articles were excluded if they had a press release through the American Heart Association or were designated as Circulation author profiles, resulting in 152 articles that were ultimately randomized. Randomization to intervention or control occurred in a block size of 4 using envelope randomization. The overall design is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the overall study design. AHA indicates American Heart Association; Circ, Circulation.

Intervention

The primary intervention consisted of exposure of original articles on Circulation's Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/Circulation) and Twitter (@CircAHA) accounts. Posts were written in clear English, included a key figure or image if possible, and appeared online Monday through Thursday to be contemporaneous with the publication of the articles. All posts contained a toll‐free link to the full‐text version of the manuscript on the Circulation website. Examples of posts are as follows: (1) “Race, #SES, and life expectancy after #AMI—read our new outcomes study here”; (2) “Meta‐analysis of >1 million pts demonstrates similar clinical outcomes for #PCI centers w/on versus off‐site surgery”; (3) “There is #genetic overlap btwn #Alzheimers, #CRP & #lipids that can help uncover novel #AD loci.” The comprehensive list of posts can be viewed by visiting the sites. Other content included in Circulation such as weekly images, review articles, clinician updates, and guidelines were also posted on social media but were not part of the clinical trial. In total, there were anywhere from 2 to 7 separate posts on both Facebook and Twitter on a daily basis. In addition, all posts were reposted the next day at 11 am and 3 pm using the “ICYMI” moniker (ie, “in case you missed it”) up to a total of 3 posts. Social media platform‐specific strategies were used. On Twitter, online interaction was encouraged by retweeting posts of articles randomized to social media using the official Circulation Twitter account. To increase the viewership of Facebook posts, posts were boosted for 24 hours for a total of $10 for each post using the following targeted approach: persons aged ≥18 years designating “cardiology” as an interest and residing in Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Germany, Egypt, France, the United Kingdom, Mexico, or the United States. At the beginning of the trial, Circulation had 46 431 likes on Facebook and 6746 followers on Twitter. By the conclusion of the trial, the journal had 87 607 likes on Facebook and 10 072 followers on Twitter.

Primary End Point

The primary end point was 30‐day page views abstracted through Circulation's Google Analytics account, including abstract, HTML, and PDF page views. The 30‐day page views were selected to be consistent with our prior study5 and because page views have been shown to correlate ultimately with citations.6

Secondary End Point

Seven‐day page views were selected as a secondary end point. Data were abstracted similarly to the process described above.

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics were categorized and tabulated and compared across randomized study arms using the chi‐square test for independence. The primary analysis was an intention‐to‐treat analysis comparing 30‐day article page views by 2‐sample t test on the log‐transformed data. As a secondary analysis, log‐transformed 7‐day page views by treatment status were examined.

Prespecified subgroup analyses included article type (population, clinical, basic), US versus non‐US corresponding author, editorial (yes, no), and trimester of publication (first: January to April; second: May to August; third: September to December). The goal of these analyses was to assess the consistency of the differences between the 2 randomized study arms within these various subgroups; it was not necessarily expected that a significant difference between the 2 randomized groups would be found within any subgroup category. Consistency was assessed using logistic regression on the log of page views with the model containing the effects of the randomized treatment arm, subgroup (eg, US versus non‐US corresponding author), and randomized treatment‐by‐subgroup interaction and rank ANCOVA.

Based on prior power calculations, the mean number of 30‐day page views in the control group was assumed to be 525, with a standard deviation of 265, and the distribution of 30‐day page views was assumed to be log‐normal. In addition, we performed a pilot study comparing 7‐day page views of manuscripts boosted with Facebook advertisements compared with manuscripts with posts on Facebook without ads. We observed that the number of 7‐day page views was 463 in the boosted group compared with 362 in the control group, a 22% difference. Assuming a sample size of 119 papers in each group and a log‐normal distribution for 30‐day page views, a relative improvement for the intervention group of 22% could be detected at 80% power, and a relative improvement of 19% could be detected at 90% power, using a 2‐sided α=0.05. An interim look at the data was planned at the point at which 50% of the manuscripts were randomized and had 30‐day follow‐up (“50% information time”). Termination of the trial was planned if there was evidence of either futility or overwhelming efficacy. Specifically, at the 50% information time, groups were compared on 30‐day page views using significance levels based on the O'Brien‐Fleming stopping philosophy7: (1) If a 1‐sided P value (assessing benefit of social media over no social media) is <0.00153, then the study may be stopped for overwhelming efficacy; (2) if a 1‐sided P value (assessing benefit of social media over no social media) is >0.50041, then the study may be stopped for futility; (3) if the conditional power for a significant beneficial social media effect by the end of the study is between 50% and 80%, a sample size increase may be undertaken to maintain 80% conditional power by the end of the study (the methodology used followed that of Chen et al,8 which allows an increase in sample size while maintaining type I error at the nominal level); (4) otherwise, the study may continue as is. To account for the α level spent at the interim look, at the final assessment (should the study not be stopped at the interim analysis), the final significance level used to test the benefit of social media over no social media was 0.02481 (1‐sided) or 0.04962 (2‐sided).

Based on the stopping criteria, the trial was stopped September 26, 2015. At that time, 123 manuscripts (52% information) had been randomized and had 30‐day follow‐up (61 to the control group and 62 to the intervention arm), resulting in a change to the P value stopping criteria for futility to 1‐sided P=0.49. The median number of 30‐day page views using the data set at a 52% information time was 459 in the control group and 486 in the intervention arm. The 1‐sided P value comparing treatment on the log of 30‐day page view was 0.49. In addition, the mean difference between treatments was approximately half of what was expected, and the standard deviation was approximately twice as large as expected in the sample size calculations.

All P values presented are 2‐sided. Analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Overall, 152 manuscripts were randomized: 74 to the social media arm and 78 to the control arm. A Kolmogorov–Smirnov test of the data to the log‐normal distribution indicated that the distribution was log‐normal within the control and intervention arms (P≥0.10). As shown in Table 1, there were no differences in manuscript characteristics between the 2 arms with respect to article type (P=0.85), geographic location of the corresponding author (P=0.33), date of publication (P=0.93), or whether the manuscript had an editorial (P=0.80).

Table 1.

Study Sample Characteristics by Trial Arm

| Social Media Arm (n=74) | No Social Media (n=78) | P Value (Chi‐Square Test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Article type (%) | |||

| Clinical | 32 (50.8) | 31 (49.2) | 0.85 |

| Basic | 24 (49.0) | 25 (51.0) | |

| Population | 18 (45.0) | 22 (55.0) | |

| Corresponding author (%) | |||

| US | 40 (52.6) | 36 (47.4) | 0.33 |

| Non‐US | 34 (44.7) | 42 (55.3) | |

| Date of publication (%) | |||

| First third | 37 (50.0) | 37 (50.0) | 0.93 |

| Second third | 29 (46.8) | 33 (53.2) | |

| Third third | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | |

| Editorial (%) | |||

| Yes | 29 (50.0) | 29 (50.0) | 0.80 |

| No | 45 (47.9) | 49 (52.1) | |

| Day of social media post (%) | |||

| Monday | 26 (100) | NA | NA |

| Tuesday | 31 (100) | ||

| Wednesday | 13 (100) | ||

| Thursday | 3 (100) | ||

Data shown as number with percentages in parentheses for dichotomous data. NA indicates not available.

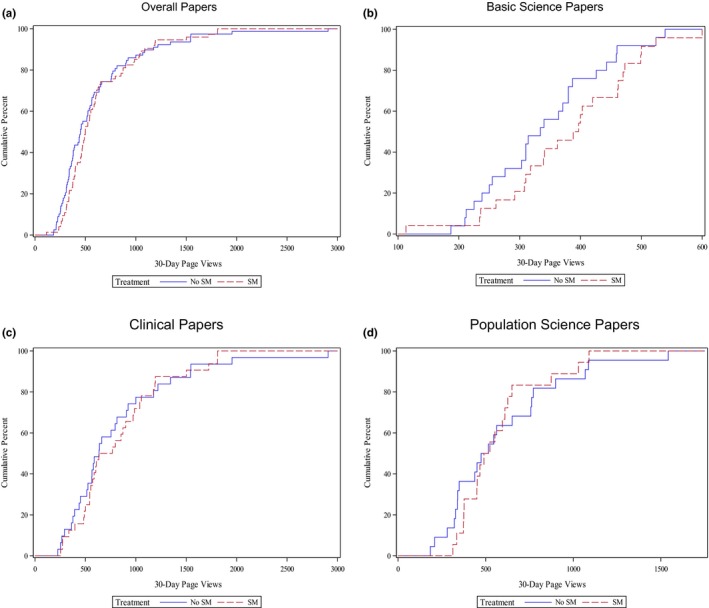

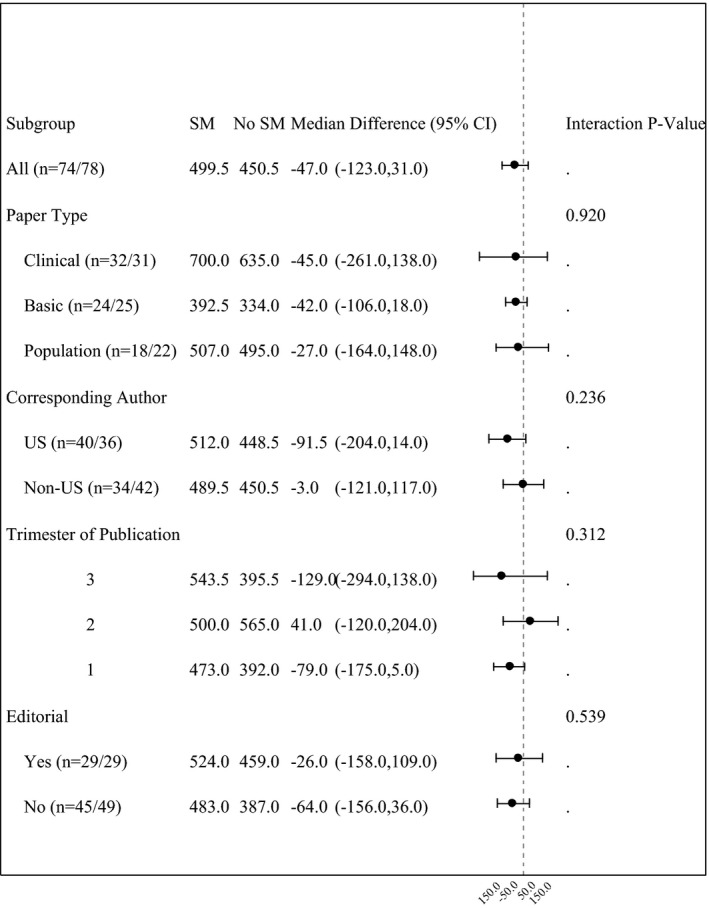

Median number of 30‐day page views was 499.5 in the intervention arm and 450.5 in the control arm (Table 2). The cumulative distribution of 30‐day page views over the course of the entire study is shown in Figure 2. There was no difference in the social media group compared with the control group (P=0.38). In prespecified subgroup analyses (Figure 3), there were no significant interactions of subgroups with treatment (P interaction>0.20 for all subgroups). Power, however, is generally low for assessment of interaction, and no conclusion of lack of subgroup effect on social media effect size can truly be made. Although the treatment‐by‐publication trimester interaction, for example, was not significant (P=0.31), social media largely improved 30‐day page views in trimester 3 (median improvement of 129 views) but was detrimental in trimester 2 (median worsening of 41 views). Further studies would be required to assess whether a true interaction existed in this case.

Table 2.

Page Views at 30 Days: Overall and Stratified by Study Sample Characteristics

| Social Media Arm | No Social Media | P Valuea Assessing Interaction of Treatment and Subgroup | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (25th/75th) | Mean (SD) | Median (25th/75th) | ||

| Overall | 616.0 (367.0) | 499.5 (375/767) | 597.2 (450.8) | 450.5 (321/754) | NA |

| Article type | |||||

| Clinical | 821.5 (437.8) | 700 (521.5/1047) | 813 (576.0) | 635 (438/1000) | 0.96 |

| Basic | 379.6 (111.0) | 392.5 (309/466) | 339.9 (98.0) | 334 (255/387) | |

| Population | 565.8 (226.1) | 507 (377/626) | 585.4 (335.6) | 495 (339/762) | |

| Corresponding author | |||||

| US | 632.4 (385.1) | 512 (392/782) | 510.0 (304.1) | 448.5 (286.5/572) | 0.21 |

| Non‐US | 596.7 (349.2) | 489.5 (341/600) | 671.8 (538.9) | 450.5 (339/772) | |

| Date of publication | |||||

| First third | 643.9 (445.4) | 473 (362/650) | 493.3 (305.3) | 392 (310/525) | 0.20 |

| Second third | 601.9 (296.2) | 500 (396/872) | 744.0 (578.5) | 565 (376/923) | |

| Third third | 537.8 (146.8) | 543.5 (466/621.5) | 471.8 (223.9) | 395.5 (303/609) | |

| Editorial | |||||

| Yes | 686.8 (435.8) | 524 (388/853) | 653.3 (501.8) | 459 (380/754) | 0.77 |

| No | 570.4 (311.7) | 483 (373/626) | 563.9 (419.7) | 387 (281/635) | |

Overall P value of treatment vs control: 0.38. NA indicates not available.

P values based on log‐page views.

Figure 2.

Cumulative distribution of page views overall and by manuscript type: (A) the overall sample, (B) basic science papers, (C) clinical papers, and (D) population science papers. SM indicates social media.

Figure 3.

Forest plots displaying the results by trial arm in the overall study and by subgroups. SM indicates social media.

Examining 7‐day page views (Table 3), there was similarly no difference in number of page views in the social media group (330.5) compared with the control group (268; P=0.17).

Table 3.

Page Views at 7 Days: Overall and Stratified by Study Sample Characteristics

| Social Media Arm | No Social Media | P Valuea Assessing Interaction of Treatment and Subgroup | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (25th/75th) | Mean (SD) | Median (25th/75th) | ||

| Overall | 397.4 (243.7) | 330.5 (234/445) | 359.1 (242.5) | 268 (196/433) | |

| Article type | |||||

| Clinical | 533.8 (282.4) | 432 (351/648.5) | 475.5 (287.4) | 391 (260/682) | 0.86 |

| Basic | 230.6 (67.9) | 233.5 (192.5/265) | 197.2 (65.5) | 178 (141/249) | |

| Population | 377.2 (169.1) | 338.5 (279/378) | 379.2 (202.5) | 341.5 (225/518) | |

| Corresponding author | |||||

| US | 405.6 (248.4) | 345.5 (235/486.5) | 318.7 (185.5) | 258 (177/368.5) | 0.35 |

| Non‐US | 387.7 (241.4) | 307.5 (233/435) | 393.8 (279.9) | 280.5 (201/518) | |

| Date of publication | |||||

| First third | 405.4 (287.7) | 279 (227/398) | 304.7 (192.8) | 246 (161/350) | 0.34 |

| Second third | 404.9 (209.7) | 347 (253/585) | 438.5 (291.7) | 367 (210/526) | |

| Third third | 333.0 (111.7) | 336 (285/380.5) | 283.6 (121.2) | 279 (177/395) | |

| Editorial | |||||

| Yes | 442.0 (291.8) | 347 (253/604) | 382.1 (233.0) | 313 (243/433) | 0.79 |

| No | 368.6 (205.4) | 319 (234/429) | 345.6 (249.3) | 256 (156/424) | |

Overall P value of treatment vs control: 0.17.

P values based on log‐page view.

Overall study sample characteristics by 30‐day page views are presented in Table 4. As expected, clinical papers had more 30‐day page views than basic science or population papers (P<0.0001). No other differences were observed across study sample characteristics.

Table 4.

Overall Study Sample Characteristics for 30‐Day Page Views

| Mean (SD) | Median (25th/75th) | P Value for Within‐Group Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Article type | |||

| Clinical | 817.3 (506.3) | 635 (489/1039) | <0.0001 |

| Basic | 359.3 (105.4) | 362 (292/443) | |

| Population | 576.6 (288.2) | 503 (361/704.5) | |

| Corresponding author | |||

| US | 574.4 (352.2) | 478.5 (342.5/650.5) | 0.41 |

| Non‐US | 638.2 (462.4) | 481 (339.5/767) | |

| Date of publication | |||

| First third | 568.6 (386.7) | 440.5 (321/596) | 0.24 |

| Second third | 677.5 (470.0) | 551 (376/874) | |

| Third third | 504.8 (186.1) | 485.5 (327/621.5) | |

| 30‐day page views | 606.3 (410.9) | 478.5 (339.5/756) | NA |

| Editorial | |||

| Yes | 670.0 (466.1) | 499.5 (380/813) | 0.07 |

| No | 567.0 (370.0) | 468.5 (310/633) | |

| Day of social media post | |||

| Monday | 692.0 (452.9) | 553 (420/650) | 0.40 |

| Tuesday | 570.7 (286.1) | 470 (335/853) | |

| Wednesday | 635.0 (389.2) | 483 (388/767) | |

| Thursday | 374.0 (119.5) | 362 (261/499) | |

NA indicates not available.

Table 5 provides an overview of demographic characteristics from Facebook, Twitter, and Google Analytics for the Circulation website.

Table 5.

User Statistics From the Circulation Facebook and Twitter Feed and Overall Circulation Website Traffic

| Demographic Information | Circulation Website Analytics | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | |||

| Women | 38 | 32 | 52.8 |

| Men | 61 | 68 | 47.2 |

| Age, y (%) | |||

| 13 to 17 | 0.9 | NA | — |

| 18 to 24 | 32 | 22.5 | |

| 25 to 34 | 40 | 27.7 | |

| 35 to 44 | 14 | 15.0 | |

| 45 to 54 | 7 | 11.5 | |

| 55 to 64 | 3 | 12.5 | |

| ≥65 | 1.8 | 10.8 | |

| Country (%) | Egypt, 19.9 | United States, 31 | United States, 46.4 |

| India, 16.4 | Spain, 11 | United Kingdom, 8.4 | |

| Mexico, 8.9 | United Kingdom, 6 | Canada, 5.0 | |

| United States, 6.7 | Mexico, 5 | India, 4.2 | |

| Brazil, 4.9 | Canada, 3 | Japan, 2.4 | |

| Colombia, 4.1 | Italy, 3 | Australia, 2.3 | |

| Pakistan, 2.7 | Australia, 3 | China, 1.9 | |

| Thailand, 1.7 | Argentina, 3 | Germany, 1.8 | |

| Italy, 1.5 | Colombia, 3 | Italy, 1.4 | |

| Saudi Arabia, 1.2 | Saudi Arabia, 2 | Thailand, 1.0 | |

Data obtained January 9, 2016, from Facebook and Twitter and January 16, 2016, from Google Analytics. NA indicates not available.

Discussion

In this randomized trial of social media exposure of original articles published in Circulation from January 2015 through September 2015, there was no difference in 30‐day page views despite increased intensity of social media delivered to the intervention arm. The trial was stopped early due to futility, and no differences were observed in prespecified subgroup analyses.

These findings are largely consistent with our prior findings, in which we failed to show increased 30‐day page views among original articles randomized to social media compared with control.5 These findings increase the generalizability of our prior findings to social media campaigns with more modestly sized followings. To expand on this point, our prior study was limited by a relatively low intensity of social media use, as demonstrated by our small following at study initiation and completion (Facebook had 16 215 likes at initiation and 28 177 at completion; Twitter had 2219 followers at initiation and 4758 at completion). In contrast, the present study had nearly 4 times as many users following. In addition, strategies were used to increase the reach of social media, including posting in triplicate, tweeting, and boosting posts using the Facebook advertising function. Despite this, the study remained unable to demonstrate differences in 30‐day page views between the 2 arms. Consequently, the generalizability of these findings can be applied to the majority of medical journal social media campaigns, which have following bases of similar magnitude to that in the present study.

Our prior findings have been criticized by others using social media to promote medical journal content. Thoma et al,9 for example, cited their experience with the Annals of Emergency Medicine, for which they created a comprehensive social media campaign that was associated with an increase in traffic to the website annemergmed.com of 289% compared with the prior calendar year. Although this increase is impressive, it is an ecological association, and attribution to the social media campaign cannot be determined based on the observational design. Dixon et al10 cited their experience with a blog post on Radiopaedia.org regarding a manuscript published in PLoS One.11 Following the blog post and sharing on Facebook, article views increased from 3234 to 6768 in the 7 days following the posting. Aase's blog piece on our prior work highlighted that good science is not always consistent with good communication and that page views do not convey the full impact of social media.12 Finally, Djuricich and Madanick13 cited our own experience of the virality of our prior study (1.5 million accounts reached on Twitter within 1 week of publishing our paper) as evidence of the power of social media. Although impressive, these anecdotes cannot be generalized to findings from a randomized control trial that exposes randomly selected manuscripts to social media instead of carefully selected papers that are featured on social media because they are deemed to have high impact.

Our findings are supported by a recent observational study that examined the impact of social media dissemination and implementation of clinical practice guidelines and failed to show a benefit with social media dissemination based on clinical practice guideline knowledge or behavioral change compared with print, email, or Internet‐based materials.14

Taken together, these findings highlight the need to develop new metrics of quantifying value for social media campaigns developed by medical journals. These findings highlight that, for original research, counting page views is not a meaningful metric. Metrics to be considered in the future may include brand recognition, community building, and knowledge assessments, although the methods in which they can ultimately be quantified may require development. In addition, these findings highlight that high‐impact papers can be identified using early social media metrics, but papers cannot be made high impact through social media promotion. A similar argument has been made for the citation index of individual papers: Although publication in a high‐impact journal might give a manuscript an early boost, in time, the scientific community tends to recognize important work regardless of target journal publication.15

Strengths of this study include the rigorous clinical trial design that was adequately powered for our primary outcome (30‐day page views). The primary outcome was objective and unbiased between the control and intervention arms. Some limitations warrant mention. The intervention was delivered solely to original articles; these findings are not generalizable to review articles, clinical practice guidelines, clinician updates, and other content that is frequently delivered on social media and in medical journals. The primary outcome, although easily quantifiable, does not reflect the complexity of social media dissemination. Furthermore, the trial was stopped early due to futility; therefore, findings are likely underpowered for prespecified analyses other than our primary outcome. Whereas our primary analysis focused on 30‐day page views, our 7‐day page view analysis suggested more granularity in findings that were more proximal to publication. Tweets are known to follow a Pareto distribution, with the majority occurring within the first 2 days of publication1; however, we were more interested in the longer term impact of social media and intentionally designed our study to focus on 30‐day page views and not a more proximal end point. We powered our study to achieve a 22% improvement in the social media arm, reflecting a trial design that would be feasible compared with powering for a lower treatment difference (eg, a 10% difference would require a 3‐year study). It is possible that smaller differences would be observable with a longer term study. Finally, although our follower base was 4 times larger than that in our prior clinical trial, it was still relatively modest. It is unclear if these findings are generalizable to medical journals with larger followings.

A more intensive social media strategy did not result in increased 30‐day page views of original research. Novel metrics of return on investment of social media strategies are required.

Disclosures

Fox, Ryan, Bonaca, Barry, Loscalzo, and Massaro are editors at Circulation and report receiving compensation for this work from the American Heart Association. Caroline Fox became an employee of Merck Research Labs as of December 14, 2015 and reports earning income and holding stock options.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003088 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.003088)

References

- 1. Eysenbach G. Can tweets predict citations? Metrics of social impact based on Twitter and correlation with traditional metrics of scientific impact. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Evans P, Krauthammer M. Exploring the use of social media to measure journal article impact. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:374–381. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu CL, Xu YQ, Wu H, Chen SS, Guo JJ. Correlation and interaction visualization of altmetric indicators extracted from scholarly social network activities: dimensions and structure. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thelwall M, Haustein S, Lariviere V, Sugimoto CR. Do altmetrics work? Twitter and ten other social web services. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fox CS, Bonaca MA, Ryan JJ, Massaro JM, Barry K, Loscalzo J. A randomized trial of social media from Circulation. Circulation. 2015;131:28–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perneger TV. Relation between online “hit counts” and subsequent citations: prospective study of research papers in the BMJ. BMJ. 2004;329:546–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics. 1979;35:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen YH, DeMets DL, Lan KK. Increasing the sample size when the unblinded interim result is promising. Stat Med. 2004;23:1023–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thoma B, Cabrera D, Trueger NS. Letter by Thoma et al. regarding article, “A randomized trial of social media from Circulation”. Circulation. 2015;131:e392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dixon A, Fitzgerald RT, Gaillard F. Letter by Dixon et al. regarding article, “A randomized trial of social media from Circulation”. Circulation. 2015;131:e393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schwarz ST, Afzal M, Morgan PS, Bajaj N, Gowland PA, Auer DP. The ‘swallow tail’ appearance of the healthy nigrosome—a new accurate test of Parkinson's disease: a case‐control and retrospective cross‐sectional MRI study at 3T. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aase L. Can social media increase medical journal article readership? Social Media Health Network blog. Available at: http://network.socialmedia.mayoclinic.org/discussion/can-socialmedia-increase-medical-journal-article-readership/. Accessed November 28, 2015.

- 13. Djuricich AM, Madanick RD. Letter by Djuricich and Madanick regarding article, “A randomized trial of social media from Circulation”. Circulation. 2015;131:e395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Narayanaswami P, Gronseth G, Dubinsky R, Penfold‐Murray R, Cox J, Bever C Jr, Martins Y, Rheaume C, Shouse D, Getchius TS. The impact of social media on dissemination and implementation of clinical practice guidelines: a longitudinal observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang D, Song C, Barabasi AL. Quantifying long‐term scientific impact. Science. 2013;342:127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]