Abstract

Some nurses who work the night shift experience high levels of sleepiness. Napping has been adopted as an effective countermeasure to sleepiness and fatigue in other safety-sensitive industries but has not had widespread acceptance in nursing. In this two-hospital implementation project, napping was offered to six nursing units where nurse executives had previously approved nap implementation for the night shift as a pilot project. Successful implementation occurred in only one of the six units with partial success in a second unit. Barriers primarily occurred at the point of seeking unit-based nursing leadership approval. On the successful unit, one hundred fifty three 30-minutes naps were taken during the 3-month pilot period. A Nap Experience Survey measured sleepiness prior to the nap, the nap duration and perceived sleep, sleep inertia after the nap, and the perceived helpfulness of the nap. A high level of sleepiness was present at the beginning of 44% of naps. For over half of naps, nurses reported sleeping slightly (43%) or deeply (14%). Sleep inertia was rare (very groggy or sluggish on arising, 1.3%). The average score of helpfulness of napping was high (7.3 on a 1–10 scale). Nurses who napped reported being less drowsy while driving home after their shift. These data suggest that when barriers to napping are overcome, napping on the nightshift is feasible and can reduce sleepiness and drowsy driving in nurses.

Nurses who work the night shift often experience high levels of sleepiness that are a normal biological consequence of working during the circadian low point (2 to 6 AM) (Åkerstedt, 1988). The work environment also has periods of low stimulation (dimmer light, quieter, less bustle) which unmasks a high propensity for sleep in nurses who may be sleep deprived as well as working at the circadian low (Dinges, 1989). Night shift sleepiness produces three problems: (1) reduced alertness and increased risk for involuntary sleep and patient care errors (Dorrian et al., 2006; Dorrian et al., 2008), (2) increased risk of job-related accidents and injuries, including motor vehicle accidents on the drive home from work, (Folkard, Lombardi, & Spencer, 2006; Horwitz & McCall, 2004; Scott et al., 2007; Swanson, Drake, & Arnedt, 2012), and (3) increased risk for long term impaired health, associated missed work and increased health care costs (Horwitz & McCall, 2004; Geiger-Brown, Lee, & Trinkoff, 2012; Geiger-Brown & Lipscomb, 2011). Scheduled naps during night shifts have decreased sleepiness, increased alertness and total sleep time, and improved response accuracy (Ruggiero & Redeker, 2014).

Studies of sleepiness during the night shift began in the 1950’s, and physiological (electroencephalographic) evidence of involuntary sleep in train engineers, truck drivers and manufacturing workers has been present in the literature since the 1980’s (Akerstedt & Landstrom, 1998). Sleep scientists have written about the benefits of napping to reduce sleepiness during the night shift since the 1970’s (Angiboust & Gousars, 1972[French language] as reported in Akerstedt & Landstrom, 1998; Akerstedt & Torsvall, 1985; Dinges, Orne, Whitehouse & Orne, 1987; Rosa et al., 1990). In other safety-sensitive industries such as aviation, transportation, and manufacturing, napping has been adopted as an effective countermeasure to sleepiness and fatigue (Ficca, Axelsson, Mollicone, Muto, & Vitiello, 2010). The Institute of Medicine’s 2004 report Keeping Patients Safe, Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses discussed the benefits of providing nurses with nap opportunities to maintain a safe work environment (Institute of Medicine, 2004). Napping was promoted as a safety practice in an evidence-based handbook for nurses published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, whose Federal mission is to create and disseminate evidence to make healthcare safer (Rogers, 2008). The Joint Commission, expressing its concern for the effect of health care worker fatigue on patient safety, published a Sentinel Alert where they recommend that all health care organizations mitigate the risk of fatigue (The Joint Commission, 2011). In this document they state that the “only way to counteract the severe consequences of sleepiness is to sleep” (pg 2), and included napping as an action that can be taken to reduce fatigue as one component of a fatigue management plan. In an excellent systematic review of experimental and quasi-experimental studies of napping, Ruggiero and Redeker (2014) concluded that “planned naps hold promise as a means to improve sleepiness and sleep-related performance deficits among shift workers…it may be feasible to implement nap programs in current workplace studies.” Finally, the American Nurses Association updated its Position Statement on Nurse Fatigue in September, 2014 (American Nurses Association, 2014) and suggested that registered nurses should “use naps (in accordance with workplace policies)”, recognizing this as an evidence-based fatigue countermeasure.

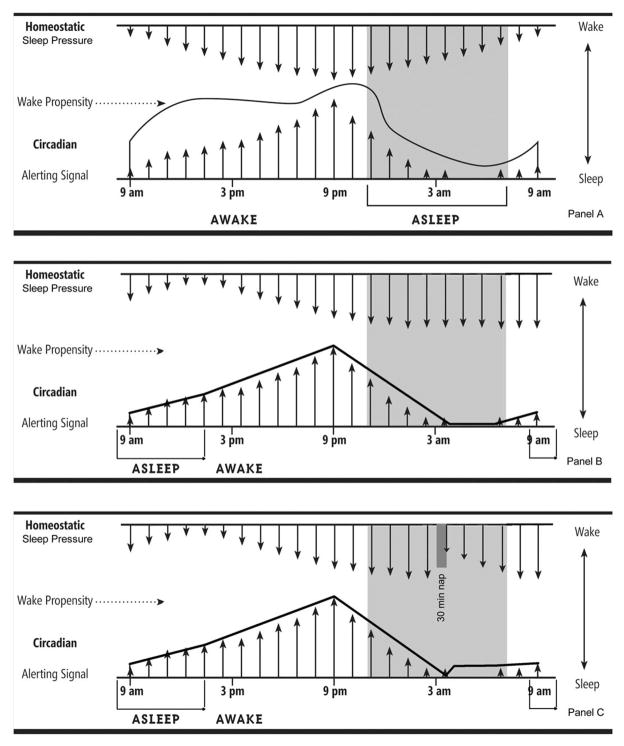

Conceptually, the benefit of napping can best be understood using the two-process model of sleep (Figure 1) (Borbely, 1982). The homeostatic drive to sleep, often called sleep pressure, increases with every hour awake, and reduces rapidly at next sleep onset. The circadian drive for wakefulness increases with daylight, with a dip after lunch, then increases to a peak from 7–9 PM, then decreases at night, with a low point between 2 and 6 AM. These forces work in opposition, and the result is that in the middle of the night there is high sleep pressure that is unopposed by waking pressure; this results in a high level of sleepiness. A short nap (20–30 minutes) reduces the homeostatic drive to sleep without inducing sleep inertia, the groggy feeling that some people feel when awakened during slow wave (deep) sleep (Tassi & Muzet, 2000). During short naps sleep is usually stage 1 or 2 (light) sleep, and under normal conditions, slow wave sleep only occurs after about 30–45 minutes of sleep time.

Figure 1.

The two-process model of sleep. Panel A (Top) represents the homeostatic and circadian processes in a day working nurse. Panel B (Middle) shows these same processes for a night shift nurse without a nap who retires upon arriving home at 8 AM, goes to sleep at 8:30 AM and wakes at 1 PM. Panel C (Bottom) shows these same processes with a 30 minute nap taken at 3:30 AM.

Artwork by Joanne Pinna, M.S.

Attitudes about napping were assessed using a survey and focus group. Edwards, Mc Millan & Fallis (2013) used a web based survey to assess experience and attitudes towards napping in 47 highly experienced critical care nurse managers in Canadian hospitals, most of whom had worked the night shift themselves. While they were well aware of the risks of fatigue on patient and nurse safety, and had evidence of actual fatigue-related adverse patient safety events and nurse drowsy driving on their units, not all were in favor of napping. Barriers fell into several categories. Administratively, the lack of a written policy on napping was common and there was a perception that even if the nurse manager himself was in favor of napping, other managers and administrators were opposed. For many there was a lack of a suitable napping space that would allow some nurses to nap while other could enjoy the break room. Concerns were expressed about combining break times to have extended periods for napping which could cause inadequate staff coverage; family concerns about nurses napping on breaks particularly when of extended duration; and covering staff not being proactive with patients. Lastly, there were concerns that nurses would have difficulty waking up and would require others to retrieve them, or have sleep inertia and function poorly if awakened to attend a code. In addition to surveying managers, a small purposive sample of critical care nurses was used to qualitatively assess nurses’ perceptions of napping (Fallis, Mc Millan & Edwards, 2011). From these data it was clear that nurses were careful about allowing naps to occur based on the need to have highly experienced staff present and alert at all times. This was also true of non-napping breaks; senior nurses ‘scanned the environment’ to make decisions about meeting patient needs before any relief was given to nurses. Breaks were not always possible, especially a ‘reality’ with night shift staffing and expectations to cover codes. Nurses varied in their response to naps; many reported improved alertness but some felt disoriented. Without a nap, nurses reported ‘foggy thinking’ and were concerned about making errors. Drowsy driving was reported including instances of dangerous unsafe driving. Nurses echoed their manager’s concerns about the lack of suitable napping space, interruptions in the break room, and a ‘sense that management does not support napping’.

There are only a few experimental studies where naps of brief duration have actually been implemented in occupational settings, including in nursing work environments. In industrial and transportation settings (aircraft maintenance, refinery operators, air traffic controllers) (Purnell, Feyer & Herbison, 2002; Sallinen, Hårmä, Åkerstedt, Rosa & Lillqvist, 1998; Signal, Gander, Anderson & Brash, 2009) night shifts ranged from 8 to 12 hours, and naps were generally brief (20 minute) although the refinery operators sometimes took naps of 45 minutes. In all of these settings there was increased vigilance when naps were taken compared to the no nap condition, and in two of three studies there was also improved alertness after the nap (Sallinen et al., 1998; Signal et al., 2009). In one small study (n=9) of nurses and other health workers in Australia, where a brief (average of 16 minute) nap was taken between 1 and 3 AM, participants showed improved vigilance and reduced sleepiness after the nap (Smith, Kilby, Jorgensen, & Douglas, 2007). In this study, sleep during the nap was documented using polysomnography (PSG), and excursions into Stage 3 (slow wave) sleep was present briefly for 2 of 6 participants with PSG data, and for a more extended period (10 minutes) in one participant. Similar improvements in vigilance and sleepiness were seen in a study of emergency room nurses and physicians who took a 25 minute nap during the night shift (Smith-Coggins et al., 2006). In both of the nursing papers there was no discussion of implementation issues around napping; the reports focused on study outcomes. The purposes of this paper are to describe the results of a two-hospital napping implementation project to assess a) barriers to successful implementation of a nightshift nap, and b) the nap experiences of nightshift nurses.

Methods

Setting

This pilot study of napping implementation was one component of a study of fatigue risk management implementation in two middle Atlantic hospitals. One is a 380 bed community teaching hospital, and the other a 313 bed freestanding children’s hospital. Both hospitals have received Magnet recognition by the American Nurses Credentialing Center.

Procedures

Initial study approval was given from the respective directors of nursing research, the nursing research councils, and then the vice presidents for nursing at each hospital. Six nursing units were selected collaboratively by the nursing research directors and nursing leadership. The process of engaging the units was the same in both settings. The PI met with each nurse manager and her designates and provided information about the risks of sleepiness on the night shift, the scientific basis for napping, and methods to avoid sleep inertia. Each unit that was offered napping was encouraged to develop their own method of implementing this within the framework of scientific knowledge about napping and preventing sleep inertia (Table 1). Nurse managers often delegated implementation to their senior nursing staff. When requested, the PI introduced the study to nurses verbally during change of shift meetings. Nurse managers were interviewed at the end of the implementation period, and night shift nurses were also interviewed as a group on the unit where napping was successful. Written notes of these conversations were used to explain the implementation outcomes. IRB approval was obtained from each hospital’s human subjects review board as well as the University of Maryland IRB.

Table 1.

Guidelines for implementing naps on the night shift for hospital nurses

| Who should nap? |

Ideally, all nurses working between the hours of midnight and 6 AM If insufficient staff to allow all night shift nurses to nap, the following should be given priority:

|

| Where should naps occur? |

The nap environment should ideally be:

|

| How long should a nap be? |

The duration of a nap is important-naps that are too long increase the risk for sleep inertia

|

| What time should naps be taken? |

Any sleep is preferable to no sleep, but ideally naps that are taken after midnight may help to alleviate sleepiness during this period

|

| What is the best way to prevent sleep inertia? |

| Nurses that have significant sleep deprivation prior to the nap are more likely to have sleep inertia compared to those who are achieving adequate sleep prior to the shift. Keeping naps short and providing a time to wake up and move about before resuming duties will help. |

Measures

A single page Nap Experience form was used by napping nurses to document aspects of the nap. Form completion took less than 2 minutes. Data included: the timing and duration of the nap, sleepiness immediately prior to the nap, sleep ability during the nap, sleep inertia upon arising, and helpfulness of the nap. Nurses completed a nap experience form each time they took a nap. No unique identifiers were collected on the Nap Experience Form.

Sleepiness prior to the nap was assessed using the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS). This scale rates sleepiness on an ordinal scale from 1 to 10 with scores of 7–10 representing a level of sleepiness that can impair workplace safety (1, extremely alert; 2, very alert; 3, alert; 4, rather alert; 5, neither alert nor sleepy, 6, some signs of sleepiness; 7 sleepy, but no effort to keep awake; 8, sleepy, but some effort to keep awake; 9, very sleepy, great effort to keep awake, fighting sleep; 10 extremely sleepy, can’t keep awake). It is widely used in sleep science to describe state sleepiness (Gillberg, Kecklund & Akerstedt, 1994), and is validated against performance and EEG measures of sleepiness (Kaida, Ǻkerstedt, Kecklund, Nilsson, & Axelsson, 2007). Sleep ability during the nap was rated on an investigator-developed four point ordinal scale (1, awake, eyes closed; 2, eyes closed, not sure if I fell asleep; 3, eyes closed, slept lightly; 4, fell asleep quickly and deeply). Sleep inertia on arising was measured using a four point scale (1, very groggy or sluggish; 2, a little groggy or sluggish; 3, alert, not refreshed; 4, alert and refreshed). The perceived helpfulness of the nap was assessed using a visual analogue scale ranging from not at all helpful (0) to extremely helpful (10).

Analysis of quantitative data

Data were described based on the level of measurement, and graphs were produced to display the relative proportions of the variables.

Results

Napping uptake

Barriers were seen on four of six units where napping was not successfully implemented. In three of these four units, the invitation to implement napping was declined by the nurse manager before presenting it to the staff or attempting implementation. One nurse manager declined stating that she did not feel it would be feasible to implement because (1) her unit covered rapid response events and she was afraid of short staffing during an event or a delay in responding, and (2) she felt there was no feasible and acceptable napping space on the nursing unit or nearby. Another nurse manager also declined, stating that nurses on her unit did not take formal breaks. Despite working 12 hour shifts, nurses just ate at the nursing station when they had an opportunity. She did not think that it would be successful to implement napping on that unit. The third manager felt that nursing care would not be as good if nurses took naps. The layout of the nursing unit was such that nurses would not be able to see the cardiac monitors of the napping nurse without running back and forth to check them. She declined to participate. The fourth manager accepted the invitation for napping implementation, presented it to staff, and implementation activities were initiated including designating a space and bedding for napping, but the implementation was not successful. There was a severe weather event early in the implementation process, and the napping space was used to house those who were staying during the winter storm. The unit did not get back to the implementation when the weather cleared due to staff reductions and high unit acuity.

There were two units where nurses did actually nap, but only one unit where the implementation could be deemed successful. On the unsuccessful unit, the manager established a napping place in a conference room that was not used at night, appointing a staff nurse “champion” for the project, and gave verbal support of the project during staff meetings. On this unit, there were 10 nurses who tried napping over the course of a three month period, but no nurse took a second nap. An interview with the manager revealed that the nurses were frequently being called to come to work on days off because a hospital-wide staffing change had eliminated staffing margins for budget reasons. She stated that the nurse to patient ratios had not changed but the unit climate was different after the staffing change, less relaxed, with more of a sense of scarcity. She felt that the climate was not right for implementing napping. The staff nurse champion felt that there was a stigma to taking naps despite reassurances that it was acceptable and could be helpful.

On the successful unit there was excellent uptake of napping, and naps continued after the study ended. On this nursing unit, the nursing director met with supervisors and charge nurses prior to implementation of napping to discuss their concerns and perceived barriers to napping. The discussion focused on how to overcome barriers and create a safe environment for napping. Once charge nurse fears/concerns were addressed, and they were fully engaged their support helped establish a secure environment that allowed napping to be successfully implemented. Engaging staff nurses in deciding how to begin a napping program in a manner that would support reducing fatigue while ensuring that patients were cared for in a safe environment was essential to successful implementation. There were several nurses who had experienced napping in other settings and actively promoted it to peers. The setting for napping was chosen to allow the nurse complete privacy while sleeping. Naps were planned at the beginning of the shift when patient care assignments were negotiated, along with coverage for the napping nurse. Nurses in this setting already took planned breaks, and there was a very high level of trust among nurses. They used a ‘buddy system’ prior to the napping implementation, so the transition to napping was made easier by their already developed teamwork. A total of 153 naps were taken over the course of three months of a trial implementation. After the study was complete, the nurses on the successful unit continued the napping protocol, but modified it to be more liberal, allowing 30 minutes of sleep plus 5 minutes on either side of the nap to allow the nurse to bed down, then refresh herself at the end of the nap. In this hospital, two other non-study units approached the investigator to learn about how to implement napping. The shared governance committee is also exploring opportunities to implement this more widely.

Nap Experience Data

A total of 153 survey questionnaires were collected and analyzed. The average nap duration was 31 minutes (SD=5.4). Nurses reported some sleepiness immediately prior to the nap (mean KSS=6.1, SD=1.8), which is expected on the night shift. For 44.2% of naps, nurses experienced a KSS score from 7–9 (Figure 1). For over half of naps nurses slept slightly (43%) or deeply (14%). Sleep inertia was relatively rare, with only 1.3% of naps ending in ‘very groggy or sluggish’ and 20.3% of naps ending in ‘a little groggy or sluggish. Nurses felt ‘alert and refreshed’ at the end of 56.2% of naps. The average score of helpfulness of napping was 7.3 out of 10 (SD=2.2).

In qualitative debriefing nurses commented that napping during the night shift eliminated drowsy driving on the way home from work. They also thought that having the napping protocol on their unit made it more desirable for nurses to ‘float’ to their unit in order to avail themselves of a nap during the night.

Discussion

This implementation study showed that barriers remain to reduce sleepiness in night shift nurses by implementing naps. The barriers seen in this multiunit study were similar to those described by Edwards et al. (2013) showing that nurse manager knowledge and attitudes about napping are a key barrier. In half of the units where we attempted implementation, the process was halted by the nurse manager before the nurses themselves were able to provide input. On the successful unit, the same barriers to napping were identified as on the unsuccessful units, but there was an open dialogue among the nurses and their leadership about the barriers, potential solutions were sought, and the model of shared governance was upheld to make the decision to proceed with a trial of napping. Future napping implementation projects will need to pay attention to the knowledge and attitudes of nurse managers and find ways of reducing the perceived risks of napping while promoting the benefits for nurses and patients. Our data also are consistent with Rogers, Hwang & Scott’s 2004 data which showed that nurses often fail to take breaks during their work shift, despite shift durations of 12 or more hours. The concept of a ‘completely relieved break’ may be more and more difficult to achieve now that staffing margins are reduced and where nurses are reluctant to relinquish digital bedside communication devices to remotely monitor their patients. The new ANA Position Statement supports nurses taking rest breaks to reduce fatigue, and makes this a joint responsibility of the employer and the nurse. We observed that this seems to be part of the culture of units as much as a staffing issue, and could be amenable to change with strong nursing leadership.

Our data also showed that nurses found naps to be helpful, which is supported by multiple experimental napping studies reviewed by Ruggiero and Redeker (2011). Although we did not directly measure drowsy driving, the repeated mention of this by nurses who napped lends support to the idea that napping could potentially reduce motor vehicle accidents on the way home from the night shift. In a description of peak times for motor vehicle accidents, for adults between the ages of 26 and 65 there is a peak of accidents between 6 and 8 a.m. (National Highway Transportation Safety Board, 2014). Given the fact that 20% of all motor vehicle accidents are attributed to drowsy driving, the burden of morbidity and mortality could be reduced by a strategic nap.

This pilot study had limitations. We attempted to implement napping in only two hospitals, and in only six units overall. A larger sample would be needed to fully understand all of the barriers, and the best methods for overcoming these. In this study we assessed each nap as an independent event and did not collect data on the identity of the nurse, so were unable to assess the within-subject aspects of the quantitative parameters that we reported.

This study has several implications for nursing practice. First, napping is unlikely to be successful unless staff nurses are willing to take completely relieved breaks in a context where safe nursing practice is possible because of adequate staffing levels based on actual acuity. Our impression is that many nurses do not take breaks despite the long duration of shifts, this is a unit culture problem, and lack of breaks contributes to fatigue. Second, napping is an evidence based practice (EBP) that has the potential to make the workplace safer. Thirty-five percent of night shift nurses nod off at work at least once a week (Hughes & Stone, 2004), and those who struggle to remain awake have 1.17–1.83 times the odds of making a medication errors and 1.9–2.1 times the odds of a near-miss medication error (Gold et al, 1992; Dorrian, Tolley, Lamond et al., 2008). Drowsy driving accounts for 40,000 fatalities per year (2–3% of overall motor vehicle crashes) (U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Transportation Safety Administration, 2011), night shift work alone have 5.5 times the odds of a crash compared to day shift (Stutts, Wilkins, Osberg, Vaughn, 2003) the hour of the day with the most crashes is between 6 and 8 AM (Pack, Pack, Rodgman, Cucchiara, Dinges, Schwab, 1995), and the strongest predictor of drowsy driving is drowsiness at work (odds of 3–5 times higher compared to those not drowsy at work) (Scott, Hwang, Rogers, Nysse, Dean, Dinges, 2007; Dorrian, Tolley, Lamond et al., 2008). Do we only consider EBP when it is convenient for management and staff? Third, napping is but one component of a health and safety management program which now mostly focuses on safe lifting and prevention of communicable diseases. Although these are important, the daily risk of drowsy driving to nurses and the driving public is much higher than lifting or infectious disease, yet this problem is ignored.

It has been 45 years since the early studies of napping in the 1970s, yet napping is far from a standard practice in health care settings where nurses are employed on the night shift. Other safety-sensitive industries have adopted napping to reduce worker sleepiness or fatigue. The barriers to napping that were found in surveys of nurse managers by Edwards et al. (2013) were also found in this implementation project. These barriers existed despite senior executive support of napping. Yet, when napping was implemented, it was well-accepted by the nurses who found it helpful, and indicated that it reduced drowsy driving on the way home from work. Although additional research will enrich the science of implementing napping in nursing settings, there is enough known now to begin the process of moving napping from a fatigue risk-management abstraction to an actual method of helping nurses to make work safer for their patients and for themselves.

Acknowledgments

Sponsor: National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety, CDC

Grant number: R21OH009979, Dr. Geiger-Brown, PI.

Footnotes

Conflicts: None to declare.

References

- Åkerstedt T, Landstrom U. Work place countermeasures of night shift fatigue. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 1998;21:3–4. 167–78. [Google Scholar]

- Åkerstedt T, Torsvall L. Napping in shift work. Sleep. 1985;8(2):105–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/8.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åkerstedt Torbjörn. Sleepiness as a consequence of shiftwork. Sleep: Journal of Sleep Research and Sleep Medicine. 1988;11:17–34. doi: 10.1093/sleep/11.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association. Position Statement: Addressing nurse fatigue to promote safety and health: joint responsibilities of registered nurses and employers to reduce risks. 2014 Retrieved from http://nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/WorkplaceSafety/Healthy-Work-Environment/Work-Environment/NurseFatigue/Addressing-Nurse-Fatigue-ANA-Position-Statement.pdf.

- Angiboust R, Gousars M. Tentative d’evaluation de l’efficacite operationelle du personnel de l’aeronautique militaire au cours de veilles nocturnes. Aspects of Human Efficiency. The English Universities Press, London. As cited in Åkerstedt, T & Landstrom, U. (1998). Work place countermeasures of night shift fatigue. In: Colquhoun WP, editor. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. Vol. 21. 1972. pp. 3–4.pp. 167–78. [Google Scholar]

- Borbely AA. A two process model of sleep regulation. Human Neurobiology. 1982;1:195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinges DF, Orne MT, Whitehouse WG, Orne EC. Temporal placement of a nap for alertness: contributions of circadian phase and prior wakefulness. Sleep. 1987;10(4):313–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinges DF. Chapter 9. The nature of sleepiness: causes, consequences and contexts. In: Stunkard AJ, Baum A, editors. Eating, Sleeping and Sex. Hillsdale, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1989. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=bf-dRU-Ie9EC&oi=fnd&pg=PA147&dq=sleepiness+low+stimulation+environment&ots=N6BsBPmZMa&sig=Nz_uc7FAyrnY62l9tvuEC2rM2NE#v=onepage&q=sleepiness%20low%20stimulation%20environment&f=false. [Google Scholar]

- Dorrian J, Lamond N, van den Heuvel C, Pincombe J, Rogers AE, Dawson D. A pilot study of the safety implications of Australian Nurses’ Sleep and Work Hours. Chronobiology International. 2006;23:1149–1163. doi: 10.1080/07420520601059615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrian J, Tolley C, Lamond N, van den Heuvel C, Pincombe J, Rogers AE, Dawson D. Sleep and errors in a group of Australian hospital nurses at work and during the commute. Applied Ergonomics. 2008;39:605–613. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MP, McMillan DE, Fallis WM. Napping during breaks on night shift: Critical care nurse managers’ perceptions. Dynamics. 2013;24(4):30–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallis WM, McMillan DE, Edwards MP. Napping during the night shift: Practices, preferences, and perceptions of critical care and emergency department nurses. Critical Care Nurse Online NOW. 2011;31(2):e1–e11. doi: 10.4037/ccn2011710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficca G, Axelsson J, Mollicone DJ, Muto V, Vitiello MV. Naps, cognition and performance. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2010;14:249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkard S, Lombardi DA, Spencer MB. Estimating the circadian rhythm in the risk of occupational injuries and accidents. Chronobiology International. 2006;23:1181–92. doi: 10.1080/07420520601096443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger-Brown J, Lipscomb J. Chapter 8. The healthcare work environment and adverse health and safety consequences for nurses. In: Kasper C, editor. Annual Review of Nursing Research. Vol. 29. 2011. pp. 195–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger-Brown J, Lee CJ, Trinkoff A. The role of work schedules in occupational health and safety. In: Gatchel RJ, Schultz IZ, editors. Handbook of Occupational Health and Wellness. Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg M, Kecklund G, Akerstedt T. Relations between performance and subjective ratings of sleepiness during a night awake. Sleep. 1994;17:236–241. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold DR, Rogacz S, Bock N, Tosteson TD, Baum TM, Speizer FE, Czeisler CA. Rotating shift work, sleep, and accidents related to sleepiness in hospital nurses. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1011–1014. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.7.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz IB, Mc Call BP. The impact of shift work on the risk and severity of injuries for hospital employees: an analysis using Oregon workers’ compensation data. Occupational Medicine. 2004;54:556–563. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqh093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R, Stone P. The perils of shift work: evening shift, night shift, and rotating shifts: are they for you? Am J Nurs. 2004;104:60–63. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200409000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Work Environment for Nurses and Patient Safety, Board on Health Care Services. Keeping Patients Safe: Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses. 2004:229. [Google Scholar]

- Kaida K, Ǻkerstedt T, Kecklund G, Nilsson JP, Axelsson J. Use of subjective and physiological indicators of sleepiness to predict performance during a vigilance task. Industrial Health. 2007;45:520–526. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.45.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Transportation Safety Board. [February 6, 2015];Drowsy driving and automobile crashes, Expert panel on driver fatigue and sleepiness. Accessed at http://www.nhtsa.gov/people/injury/drowsy_driving1/Drowsy.html.

- Pack AI, Pack AM, Rodgman E, Cucchiara A, Dinges DF, Schwab CW. Characteristics of crashes attributed to the driver having fallen asleep. Accid Anal and Prev. 1995;27:769–775. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(95)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnell MT, Feyer AM, Herbison GP. The impact of a nap opportunity during the night shift on the performance and alertness of 12-h shift workers. J Sleep Res. 2002;11:219–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AE. The effect of fatigue and sleepiness on performance and patient safety. In: Hughes R, editor. Advances in Patient Safety & Quality – an Evidence-based Handbook for Nurses. Published by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AE, Hwang WT, Scott LD. The effect of work breaks on staff nurse performance. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2004;34:512–519. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200411000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa RR, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, Eastman CI, Monk T, Penn PE, et al. Intervention factors for promoting adjustment to nightwork and shiftwork. Occupational Medicine. 1990;5:391–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero JS, Redeker NS. Effects of napping on sleepiness and sleep-related performance deficits in night-shift workers: a systematic review. Biological Research for Nursing. 2014;16:134–142. doi: 10.1177/1099800413476571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LD, Hwang WT, Rogers AE, Nysse T, Dean GE, Dinges DF. The relationship between nursing work schedules, sleep duration, and drowsy driving. Sleep. 2007;30:1801–1807. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallinen M, Harma M, Akerstedt T, Rosa R, Lillqvist O. Promoting alertness with a short nap during a night shift. J Sleep Res. 1998;7:240–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1998.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signal TL, Gander PH, Anderson H, Brash S. Scheduled napping as a countermeasure to sleepiness in air traffic controllers. J Sleep Res. 2009;18(1):11–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS, Kilby S, Jorgensen G, Douglas JA. Napping and nightshift work: Effects of a short nap on psychomotor vigilance and subjective sleepiness in health workers. Sleep and Biol Rhythms. 2007;5:117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Coggins R, Howard SK, Mac DT, Wang C, Kwan S, Rosekind MR, et al. Improving alertness and performance in Emergency Department physicians and nurses: the use of planned naps. Annals of Emergency Med. 2006;48:596–604. c3. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutts JC, Wilkins JW, Osberg JS, Vaughn BV. Driver risk factors for sleep-related crashes. Accid Anal Prev. 2003;35:321–331. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(02)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LM, Drake C, Arnedt JT. Employment and drowsy driving: a survey of American workers. Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 2012;10:250–7. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2011.624231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassi P, Muzet A. Sleep inertia. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4(4):341–353. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2000.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. The Joint Commission Sentinal Event Alert. Health care worker fatigue and patient safety Issue 48. 2011 Dec 14; Retrieved from http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/sea_48.pdf. [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Transportation, National Transportation Highway Safety Administration. Drowsy Driving. Traffic Safety Facts and Statistics. 2011 DOT HS 811 449. [Google Scholar]