Abstract

N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline (Ac-SDKP) is a natural tetrapeptide with anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties. Previously, we have shown that prolyl oligopeptidase (POP) is involved in the Ac-SDKP release from thymosin-β4 (Tβ4). However, POP can only hydrolyze peptides shorter than 30 amino acids, and Tβ4 is 43 amino acids long. This indicates that before POP hydrolysis takes place, Tβ4 is hydrolyzed by another peptidase that releases NH2-terminal intermediate peptide(s) with fewer than 30 amino acids. Our peptidase database search pointed out meprin-α metalloprotease as a potential candidate. Therefore, we hypothesized that, prior to POP hydrolysis, Tβ4 is hydrolyzed by meprin-α. In vitro, we found that the incubation of Tβ4 with both meprin-α and POP released Ac-SDKP, whereas no Ac-SDKP was released when Tβ4 was incubated with either meprin-α or POP alone. Incubation of Tβ4 with rat kidney homogenates significantly released Ac-SDKP, which was blocked by the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin. In addition, kidneys from meprin-α knockout (KO) mice showed significantly lower basal Ac-SDKP amount, compared with wild-type mice. Kidney homogenates from meprin-α KO mice failed to release Ac-SDKP from Tβ4. In vivo, we observed that rats treated with the ACE inhibitor captopril increased plasma concentrations of Ac-SDKP, which was inhibited by the coadministration of actinonin (vehicle, 3.1 ± 0.2 nmol/l; captopril, 15.1 ± 0.7 nmol/l; captopril + actinonin, 6.1 ± 0.3 nmol/l; P < 0.005). Similar results were obtained with urinary Ac-SDKP after actinonin treatment. We conclude that release of Ac-SDKP from Tβ4 is mediated by successive hydrolysis involving meprin-α and POP.

Keywords: N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline, thymosin-β4, meprin-α, prolyl oligopeptidase, angiotensin-converting enzyme

the anti-inflammatory peptide N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline (Ac-SDKP) was identified originally in the bone marrow (24). It has also been widely distributed in mammalian organs, plasma, urine, and circulating mononuclear cells (23, 39, 46). In animal diseases with hypertension, as well as cardiovascular and kidney disease, Ac-SDKP reduces inflammatory cell infiltration and collagen deposition in the heart, kidney, lung, and liver (14, 15, 33, 34, 37, 44). Ac-SDKP is hydrolyzed by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and has a short half-life of 4.5 min in the circulation (16). Treatment with ACE inhibitors significantly increased plasma concentration of Ac-SDKP (2), and some of the ACE inhibitors protective effects were reported to be mediated by the increases in Ac-SDKP concentrations (34, 35).

Thymosin-β4 (Tβ4) is a major G-actin-sequestering peptide that consists of 43 amino acids. Since it contains the Ac-SDKP sequence in its NH2-terminal, Tβ4 is considered to be the precursor of Ac-SDKP (19, 39). Our group has shown previously that Ac-SDKP is released from Tβ4 by the peptidase(s) present in kidney homogenates, and this release is blocked by specific inhibitors of prolyl oligopeptidase (POP) (13). However, POP has a structural characteristic in that it is unable to hydrolyze peptides containing more than 30 amino acids (36). Hence, larger peptides and proteins are resistant to POP hydrolysis (29). Therefore, prior to Ac-SDKP release via POP cleavage, Tβ4 must undergo hydrolysis by an unknown peptidase(s).

To determine the peptidase(s) that is capable of hydrolyzing Tβ4, we performed a peptidase database search and found strong hits for meprin-α metalloprotease and matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) (41). Meprin-α is a zinc endopeptidase of the astacin family that is highly expressed in the brush border membrane of proximal kidney tubules and small intestine (9, 40). Here, we hypothesized that Ac-SDKP is released from Tβ4 through a two-step hydrolysis, first mediated by meprin-α that releases NH2-terminal intermediate peptide(s) with <30 amino acids, followed by POP hydrolysis of intermediate peptide(s) to finally release Ac-SDKP. Therefore, we designed a new study to determine 1) in vitro, whether incubation of Tβ4 in the presence of meprin-α and POP releases Ac-SDKP; 2) in vitro, whether incubation of Tβ4 in the presence of kidney homogenates from wild-type and meprin-α knockout (KO) mice releases Ac-SDKP; 3) in vitro and in vivo, whether the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin decreases the Ac-SDKP content in rats, and 4) meprin-α cleavage sites on Tβ4 and to identify the putative intermediate substrate(s) for POP.

METHODS

Materials.

Recombinant meprin-α, recombinant MMP-2, anti-meprin-α, anti-meprin-β antibodies, and Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp)-OH (fluorogenic meprin-α substrate) were purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phsophate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Chemiluminescence substrate was purchased from Pierce Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL). Recombinant POP, actinonin (meprin-α inhibitor), captopril (ACE inhibitor), 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC standards for POP enzyme activity), pepstatin, leupeptin, and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled inulin (FITC-Inulin) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail was purchased from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Z-Gly-Pro-AMC (POP substrate) was purchased from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland). Ac-SDKP ELISA kit was purchased from SPIBio (Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France). The POP inhibitor S-17092 was a gift from P. Vanhoutte, Institut de Recherches Internationales Servier (Courbevoie, France). Thymosin-β4 (Tβ4) was provided as a gift by Regene Rx Biopharmaceuticals, (Rockville, MD).

Experimental animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) and male C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice (Jackson Laboratories, Sacramento, CA) at 8 wk of age were housed in the bioresource facility at Henry Ford Hospital. Male meprin-α KO mice (on C57BL/6 background) at 8 wk of age were housed in the Laboratory Animal Resource Unit at the North Carolina A & T State University. Animals were kept at room temperature in vented cages with 12:12-h light-dark cycle and fed rodent chow ad libitum. Animals were acclimatized to the new environment for 2 wk before the experiments were performed. All surgical procedures were conducted under either thiobutabarbital (125 mg/kg body wt ip) or ketamine-xylazine (120:10 mg/kg body wt ip) anesthesia. All of the experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Henry Ford Hospital and North Carolina A & T State University.

Assay for Ac-SDKP.

Ac-SDKP was measured using a commercially available, highly specific, competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit, as described previously (13). Briefly, for in vivo studies, following the treatments blood was collected into heparinized prechilled tubes containing freshly prepared captopril at a final concentration of 10 μmol/l and followed by centrifugation to obtain plasma. Captopril was added to prevent Ac-SDKP degradation during the sample processing. Ac-SDKP was measured in methanol-extracted plasma according to the manufacturer's instructions. Urine was collected directly from the bladder via a catheter into the tube containing captopril at a final concentration of 10 μmol/l. Urine samples were assayed without methanol extraction. For in vitro studies, the enzymatic reaction was stopped by boiling the samples for 5 min, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15 min. The Ac-SDKP present in the supernatant was quantified.

Tβ4 hydrolysis by meprin-α and POP in vitro.

To determine whether meprin-α is capable of hydrolyzing Tβ4 in vitro, Tβ4 (20 μmol/l) was incubated at 37°C for 3 h in the following five conditions: 1) meprin-α (20 nmol/l), 2) POP (20 nmol/l), 3) meprin-α + POP, 4) meprin-α + POP + actinonin (20 μmol/l), and 5) meprin-α + POP + S17092 (20 μmol/l). There was n = 6 in each group. The total reaction volume was 100 μl in PBS buffer (pH 7.4). The concentrations of reagents used in this protocol were determined based on the previous studies, with minor modifications (1). Ac-SDKP was then quantified by ELISA assay. For reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography experiments, 50 μmol/l Tβ4 was incubated at 37°C for 3 h in the presence of meprin-α, and the reaction was stopped by adding 0.1% trifluroacetate (TFA). We used a higher concentration of Tβ4 for the HPLC protocol based on a previous study (30). Samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 10,000 g, and 100 μl of the supernatant was applied to a C-18 column, 4 μm particle size (Waters, Milford, MA), and peptides were eluted with 25 min of linear gradient of acetonitrile-0.1% TFA (50:50%). Elution peaks were collected individually by a fraction collector and then directly infused via an injection loop in LTQ ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) for peptide characterization.

In vitro Tβ4 hydrolysis by rat kidney homogenates.

To harvest kidneys, Sprague-Dawley rats were anesthetized and then transcardially perfused with 0.9% NaCl for 5–6 min to remove blood from the kidneys. The kidneys were excised, decapsulated, individually weighed, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until they were homogenized. Kidneys were homogenized in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 10 μmol/l captopril using an IKA Ultra-turax homogenizer, followed by sonication. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C to remove cell debris and supernatants (kidney homogenates) collected. The total protein concentrations were determined by Bradford assay (5). Aliquots of supernatants were stored at −80°C until further use. To determine Ac-SDKP release from Tβ4 hydrolysis, kidney homogenates (50 μg) were incubated at 37°C for 3 h as follows: 1) control, kidney homogenates (KH) alone; 2) KH + Tβ4 (20 μmol/l); 3) KH + Tβ4 + actinonin (20 μmol/l); 4) KH + Tβ4 + S17092 (20 μmol/l); and 5) KH + Tβ4 + actinonin + S17092 (n = 8 in each group). Stock solutions of actinonin and S17092 were prepared in 10% ethanol and DMSO, respectively, and then diluted to their final concentration in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 10 μmol/l captopril. Ac-SDKP in these samples was quantified by ELISA, as described above.

In vitro Tβ4 hydrolysis by kidney homogenates from meprin-α KO mice.

Kidney tissues were obtained from meprin-α KO mice (on a C57BL/6 background). Kidney homogenates were prepared as described for rats. Kidney homogenates (250 μg) from either meprin-α KO or WT- mice were incubated at 37°C for 3 h in the presence of the following: 1) control, kidney homogenates alone; 2) KH + Tβ4 (20 μmol/l); and 3) KH + Tβ4 + actinonin (20 μmol/l) (n = 6 in each group). The Ac-SDKP content was then measured as described above.

Western blot analysis for meprin-α and -β isoforms.

Kidney homogenate proteins (20 μg) from meprin-α KO and WT mice were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel and transferred on to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The blotted membrane was incubated with either anti-meprin-α (1:2,000) or anti-meprin-β (1:2,000) antibodies. The meprin protein bands were visualized using a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and chemiluminescence reagent. The housekeeping gene product GAPDH (1:10,000) served as a loading control.

Meprin-α and POP activity assays.

Meprin-α and POP enzyme activities were measured as described previously (27, 47). Briefly, meprin-α activity was measured with fluorogenic substrate Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp)-OH. Kidney homogenates (50 μg) from C57BL/6 mice and Sprague-Dawley rats were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and pH 7.4 with 10 μmol/l of fluorogenic substrate in PBS containing the following broad range protease inhibitors: Complete EDTA-free cocktail from Roche, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 10 μmol/l leupeptin, 1 mmol/l CaCl2, and 1 mmol/l ZnCl2. Fluorescence of the released product was measured using a fluorometer (SpectraMax, M2) at excitation of 320 nm and emission of 405 nm. The unit of relative meprin-α activity is expressed as arbitrary fluorescence units (AFU) per minute per milligram of total protein. The meprin-α inhibitor actinonin (100 μmol/l) was used as a control. POP enzyme activity was measured with fluorogenic substrate Z-Gly-Pro-AMC. Kidney homogenate proteins (50 μg) from mice and rats were incubated with 50 μmol/l fluorogenic substrate in PBS, pH 7.4, for 60 min at 37°C. Fluorescence of released AMC product was measured at excitation of 360 nm and emission of 460 nm and quantified against AMC standards. Specific POP activity is expressed as picomoles of AMC per minute per milligram of total protein. The POP inhibitor S17092 (20 μmol/l) was used as a control.

Determining the effect of meprin-α inhibition on Ac-SDKP concentrations in vivo.

The acute effect of actinonin on the Ac-SDKP concentrations was tested in vivo. Rats were randomly divided into eight groups: 1) control-untreated (n = 6), 2) control-vehicle (n = 6), 3) actinonin (20 mg/kg; n = 6), 4) captopril (50 mg/kg; n = 9), 5) captopril + actinonin (n = 9), 6) Tβ4 (20 mg/kg; n = 6), 7) Tβ4 + captopril (n = 6), and 8) Tβ4 + captopril + actinonin (n = 6). Captopril and Tβ4 were prepared in PBS (pH 7.4), and actinonin was prepared in 10% ethanol in PBS (pH 7.4). Concentrations of reagents used in this protocol were determined based on previous studies, with minor modifications (13, 46, 47). Bolus intravenous injection of captopril, actinonin, Tβ4, and vehicle (PBS containing 10% ethanol) were administered while the animals were kept on a warm pad. Rat bladders were flushed twice with 0.9% warm saline before the initiation of urine collection. Urine was collected continuously from the bladder via a catheter for 1 h in a tube containing 10 μmol/l captopril. Blood was collected 1 h after the administration of the drug into heparinized prechilled tubes containing 10 μmol/l captopril and centrifuged to obtain plasma. Samples were kept frozen at −80°C until an Ac-SDKP ELISA assay was performed.

Determining the effect of actinonin and captopril on blood pressure and glomerular filtration rate in rats.

The effects of actinonin and captopril on blood pressure and renal function were measured as described previously (13, 25). Rats were randomly divided into three groups: 1) vehicle (n = 4), 2) actinonin (20 mg/kg; n = 4), and 3) captopril (50 mg/kg; n = 4). Briefly, rats were anesthetized and placed on a heating pad. Femoral artery and vein were catheterized for the measurement of mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and drug administration, respectively. After a 20-min stabilization period, MAP was recorded for 20 min (baseline), after which drugs were administered. After administering each drug, MAP was allowed to stabilize for 20 min, and blood pressure was recorded for 20 min. The effect of actinonin and captopril on glomerular filtration rate (GFR), an index of renal function, was measured in the same anesthestized rats using fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled inulin (FITC-inulin). FITC-inulin dissolved at 10 mg/ml in PBS, pH 7.4 was injected as a bolus at 3 μl/g body wt, followed by a constant infusion of 0.15 μl·min−1·g body wt−1. After a 30-min stabilization period, urine was collected for 30 min via bladder catheter. Blood was withdrawn via vein catheter in two heparinized glass capillary tubes (100 μl/tube) before and after the 30-min urine collection. Plasma was separated by centrifugation. Samples of FITC-inulin standards, plasma, and diluted urine in 10 mmol/l HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) were transferred into a black 96-well microplate in triplicate. Fluorescence of FITC-inulin was measured using a microplate fluorescence reader at the excitation of 485 nm and emission of 538 nm. GFR was calculated using the following formula: GFR = (urine fluorescence × urine volume/blood fluorescence)/collection time. GFR was corrected by body weight, and units are expressed as milliliters per minute per 100 grams of body weight.

Mass spectrometry to identify meprin-α cleavage sites on Tβ4.

After Tβ4 (50 μmol/l) was incubated in the presence of meprin-α (20 nmol/l) for 3 h at 37°C, the reaction was stopped by adding 0.1% TFA. Peptides were purified by strong cation exchange chromatography using a polysulfoethyl aspartamide microspin column (The Nest Group, Southborough, MA) and dried in a speed vacuum. Samples were resuspended in 5% acetonitrile-0.1% formic acid-0.005% trifluoroacetic acid and analyzed using an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer coupled to an Easy-nLC 1000 UHPLC system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Statistical analysis.

A nonparametric two-sample Wilcoxon test was used to compare contrasts of interest in all of the data. Significance was determined using Hochberg's method to adjust for multiple testing. The adjustment was made on groups of similar tests. A P value of <0.05 was considered evidence of significant differences. Analysis was generated using SAS/STAT software, version 9.3 of the SAS System for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Both meprin-α and POP were required for the release of Ac-SDKP from Tβ4 in vitro.

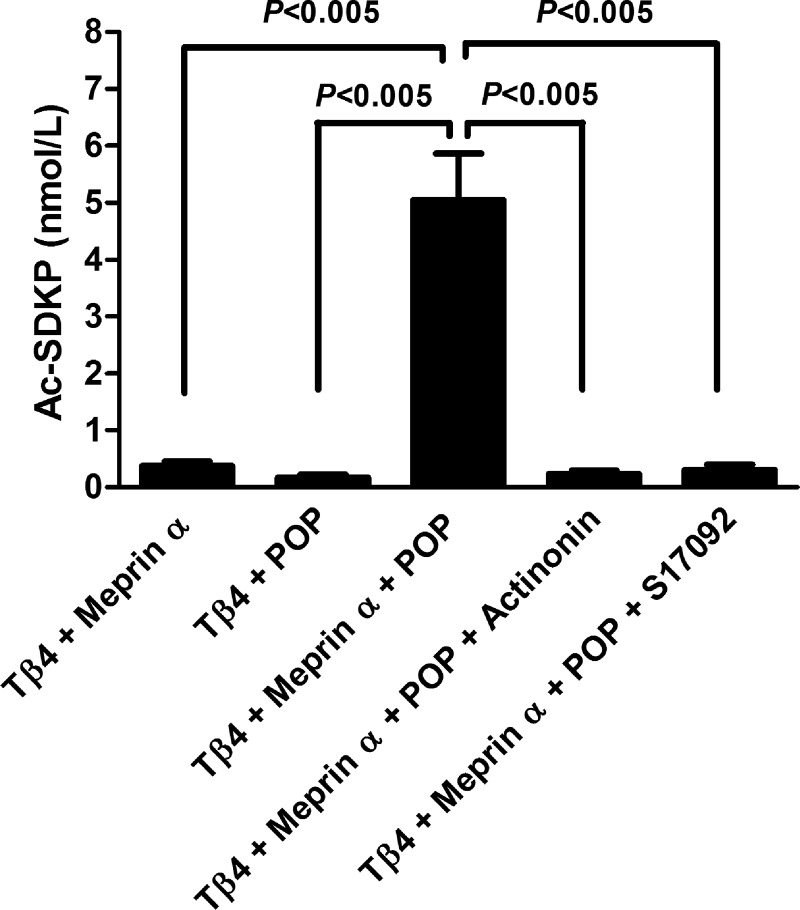

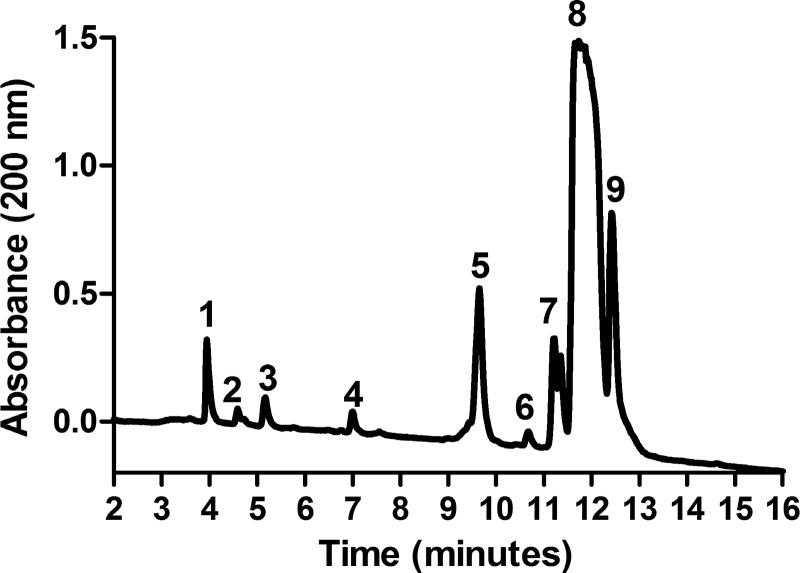

Incubation of Tβ4 with either meprin-α or POP alone did not release Ac-SDKP (0.37 ± 0.08 nmol/l Tβ4 + meprin-α, 0.17 ± 0.05 nmol/L Tβ4 + POP). However, when Tβ4 was incubated with both meprin-α and POP, Ac-SDKP release was significant (5.05 ± 0.81 nmol/l; Fig. 1). This release of Ac-SDKP from Tβ4 in the presence of both meprin-α and POP was completely inhibited by the addition of either the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin (0.22 ± 0.06 nmol/l) or the POP inhibitor S17092 (0.30 ± 0.09 nmol/l) (Fig. 1). The presence of Ac-SDKP in this reaction mixture was further confirmed by mass spectrometer. Figure 2 shows that reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography chromatogram of elution peaks after Tβ4 was incubated with both meprin-α and POP. Eluted peptides were analyzed by a mass spectrometer. Fraction represented by peak no. 3, which eluted at ∼5 min, was identified to be Ac-SDKP (molecular mass: 487.5). Other peaks represent the rest of the peptides that were the product of Tβ4 hydrolysis. A summary of the amino acid sequence of eluted peptides is shown in the legend to Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline (Ac-SDKP) was not released from thymosin-β4 (Tβ4) by meprin-α (20 nmol/l) or prolyl oligopeptidase (POP; 20 nmol/l) alone. Ac-SDKP was released from Tβ4 (20 μmol/l) by the action of both meprin-α (20 nmol/l) and POP (20 nmol/l). Release of Ac-SDKP from Tβ4 was blocked by the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin (20 μmol/l) and POP inhibitor S17092 (20 μmol/l) (n = 6 in each group). All data are expressed as means ± SE.

Fig. 2.

HPLC chromatogram showing eluted peaks after Tβ4 (50 μmol/l) hydrolysis in the presence of both meprin-α (20 nmol/l) and POP (20 nmol/l). Fraction no. 3, which eluted at ∼5 min, was identified as Ac-SDKP. Other peaks represent the rest of the peptides that were the product of Tβ4 hydrolysis. Fraction no. 1, ETIEQEK (mass: 872.4); fraction no. 2, SKLKK (mass: 602.6); fraction no. 3, Ac-SDKP (mass: 487.5); fraction no. 4, SKETIEQEKQA (mass: 1,289.8); fraction no. 5, TQEKNPLPSKETIEQEKQAGE S (mass: 2,470.5); fraction no. 6, TETQEKNPLPSKETIEQEKQAGES (mass: 2,702.1), fraction no. 7, DMAEIEKFDKSKLKK (mass: 1,811) and Ac-SDKPDMAEIEKFDKSKLKKTETQE KNPLPSKETIEQEKQAGES (mass: 4,965.8); fraction no. 8, Ac-SDKPDMAEIEKFDKSKLK KTETQEKNPLPSKETIEQEKQAGES (mass: 4,965.8); fraction no. 9, Ac-SDKPDMAEIEKF DKSKLKKTETQEKNPLPSKETIE (mass: 4,107.5). The absorbance of peptides was taken at a wavelength of 200 nm. Eluted peptides were collected and analyzed by a mass spectrometer.

All of the enzymatic reactions in this present study were stopped by boiling. We tested whether boiling temperature affected Ac-SDKP measurement by ELISA. We found that boiling temperature did not change Ac-SDKP content in rat kidney homogenate [kidney homogenates (KH) not boiled at 4.50 ± 0.16 pmol/mg protein and KH boiled at 4.52 ± 0.17 pmol/mg protein]. Therefore, this method may be used to inactivate the enzymes, which subsequently stops any further Ac-SDKP release from Tβ4. We also studied the effect of metalloproteinase enzyme MMP-2, one of the potential candidate enzymes. MMP-2 incubated with Tβ4 alone or with POP did not release any Ac-SDKP (0.06 ± 0.04 nmol/l MMP-2 + Tβ4 and 0.02 ± 0.08 nmol/l MMP-2 + Tβ4 + POP). These data indicate that MMP-2 is not involved in Ac-SDKP release from Tβ4.

Actinonin blocked Ac-SDKP release from Tβ4 by rat kidney homogenates in vitro.

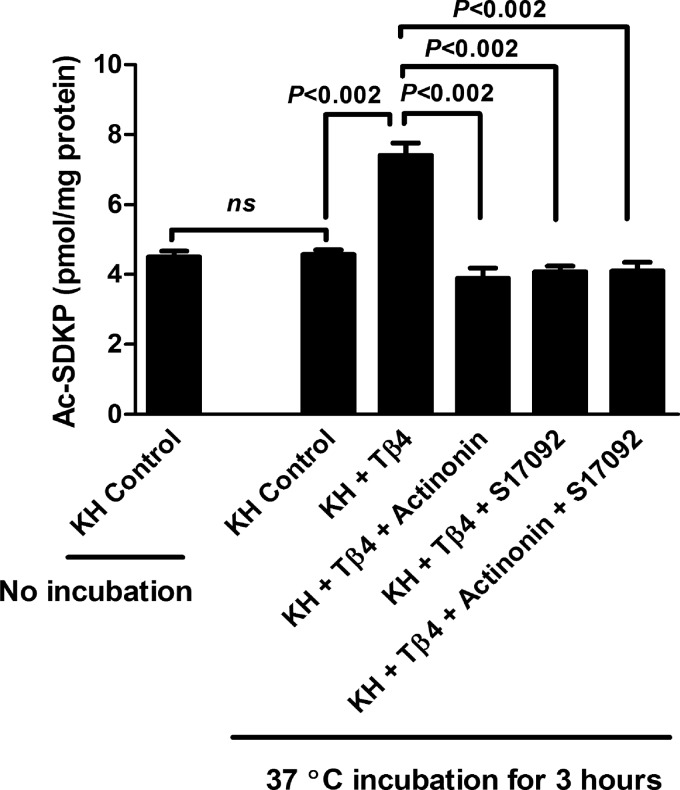

We next studied the effect of the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin on the release of Ac-SDKP from Tβ4 by rat kidney homogenates. Significant amounts of basal Ac-SDKP were detected in the rat kidney homogenates without the addition of any Tβ4 (KH control without incubation; Fig. 3). This was expected, because Ac-SDKP is widely present in mammalian organs, including the kidney (19). Ac-SDKP amount in the kidney homogenates alone after incubation at 37°C for 3 h was not increased compared with the kidney homogenates before incubation (KH control 37°C for 3 h; Fig. 3). This may be due to the low basal concentration of Tβ4 in the kidney (19), and as a result, the Ac-SDKP amount was not increased in the kidney homogenates after incubation. Kidney homogenates incubated with exogenous Tβ4 released significantly higher amounts of Ac-SDKP (7.40 ± 0.35 pmol/mg protein KH + Tβ4) compared with the condition where KH were incubated alone (4.57 ± 0.13 pmol/mg protein control KH) (Fig. 3). This release of Ac-SDKP from Tβ4 by kidney homogenates was blocked by the addition of actinonin (3.89 ± 0.29 pmol/mg protein), S17092 (4.07 ± 0.16 pmol/mg protein), and actinonin + S17092 (4.09 ± 0.24 pmol/mg protein) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of different treatments on the release of Ac-SDKP from Tβ4 (20 μmol/l) by rat kidney homogenates (KH; 50 μg). Control sample is the KH only. Ac-SDKP amount in KH before and after incubation at 37°C for 3 h was similar. Addition of exogenous Tβ4 resulted in a significant increase in the Ac-SDKP amount by kidney homogenates. The release of Ac-SDKP was blocked by meprin-α inhibitor actinonin (20 μmol/l) and POP inhibitor S17092 (20 μmol/l) either alone or together (n = 8 in each group). All data are expressed as means ± SE.

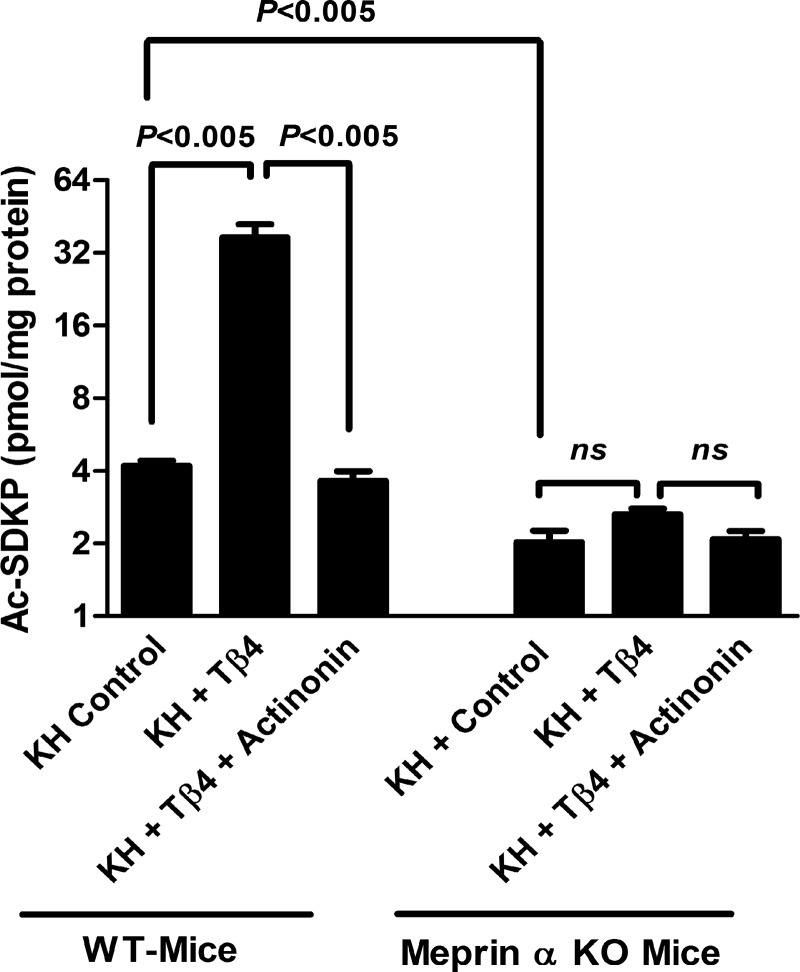

KH from meprin-α KO mice did not release Ac-SDKP from Tβ4 in vitro.

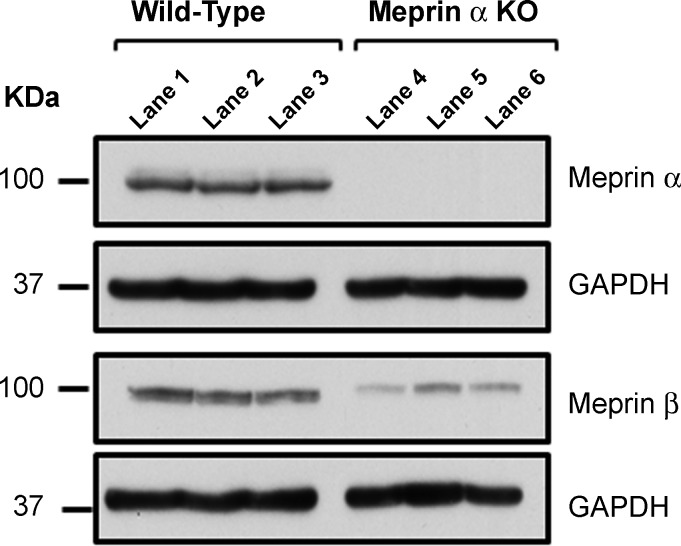

Western blot analysis showed the presence of meprin-α and meprin-β isoforms in the kidneys from WT mice. It also showed the absence of meprin-α and presence of meprin-β isoform in the kidney proteins from meprin-α KO mice (Fig. 4). The basal Ac-SDKP content was significantly lower in the kidney tissue from meprin-α KO mice compared with the WT mice (Fig. 5). Incubation of KH from WT mice in the presence of exogenous Tβ4 significantly released Ac-SDKP (37.02 ± 4.97 pmol/mg protein KH + Tβ4) compared with KH alone (4.21 ± 0.19 pmol/mg protein KH control) (Fig. 5). This increase in Ac-SDKP release from Tβ4 by KH of WT mice was blocked by the addition of the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin (3.64 ± 0.35 pmol/mg protein KH + Tβ4 + actinonin). However, KH of meprin-α KO mice incubated in the presence of exogenous Tβ4 did not release Ac-SDKP (2.02 ± 0.23 pmol/mg protein KH control, 2.64 ± 0.15 pmol/mg protein KH + Tβ4, and 2.08 ± 0.16 pmol/mg protein KH + Tβ4 + actinonin) (Fig. 5). These data indicate the important role of meprin-α in the Ac-SDKP release from Tβ4.

Fig. 4.

Meprin-α and meprin-β protein detection in wild-type (WT) mice and meprin-α knockout (KO) mice. Immunoblot for meprin-α and meprin-β in the KH from WT mice (lanes 1–3) and meprin-α KO mice (lanes 4–6) (n = 3 in each group).

Fig. 5.

Release of Ac-SDKP from Tβ4 (20 μmol/l) by KH (250 μg) from WT and meprin-α KO mice. Control is the KH only. Addition of exogenous Tβ4 in the KH from WT mice resulted in a significant Ac-SDKP release, and this Ac-SDKP release was blocked by the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin (20 μmol/l). Amount of Ac-SDKP was significantly lower in the KH from meprin-α KO mice compared with WT-mice. KH from meprin-α KO mice failed to release Ac-SDKP in the presence of Tβ4 (n = 6 in each group). All data are expressed as means ± SE. NS, not significant.

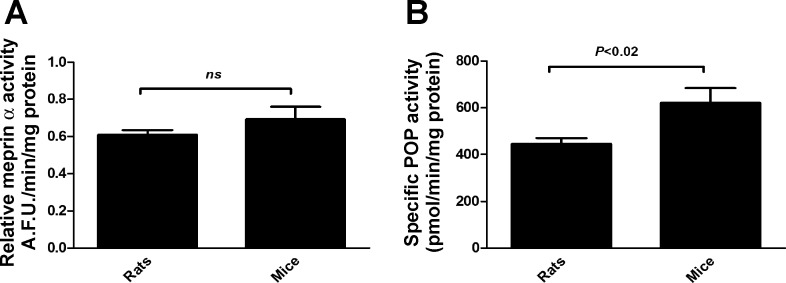

POP activity, but not meprin-α activity, is significantly higher in mice than in rats.

Our previous results showed that KH from C57BL/6 mice in the presence of Tβ4 released higher amounts of Ac-SDKP compared with the Sprague-Dawley rats. To understand the observed effects, we tested the enzyme activities of meprin-α and POP in KH of rats and mice. There were no significant differences in the meprin-α activity between rats (0.61 ± 0.03 AFU·min−1·mg−1 protein) and mice (0.69 ± 0.07 AFU·min−1·mg−1 protein) (Fig. 6A). However, POP activity was significantly higher in the KH from mice (621 ± 62.86 pmol·min−1·mg protein−1) compared with the KH from rats (446.45 ± 23.17 pmol·min−1·mg protein−1) (Fig. 6B). This may in part explain the higher Ac-SDKP release from Tβ4 by the KH from mice compared with the KH from rats.

Fig. 6.

Meprin-α (A) and POP activity (B) in the KH from Sprague-Dawley rats and C57BL/6 mice. KH protein (50 μg) from rats and mice was incubated in the presence of either fluorogenic meprin-α substrate [Mca-YVADAPK(Dnp)-OH at 10 μmol/l; A] or fluorogenic POP substrate (Z-Gly-Pro-AMC at 50 μmol/l; B). Fluorescence of the released product was measured. POP activity, but not meprin-α activity, was higher in KH from mice compared with the activity in KH from rats; n = 6 in each group. All data are expressed as means ± SE. AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

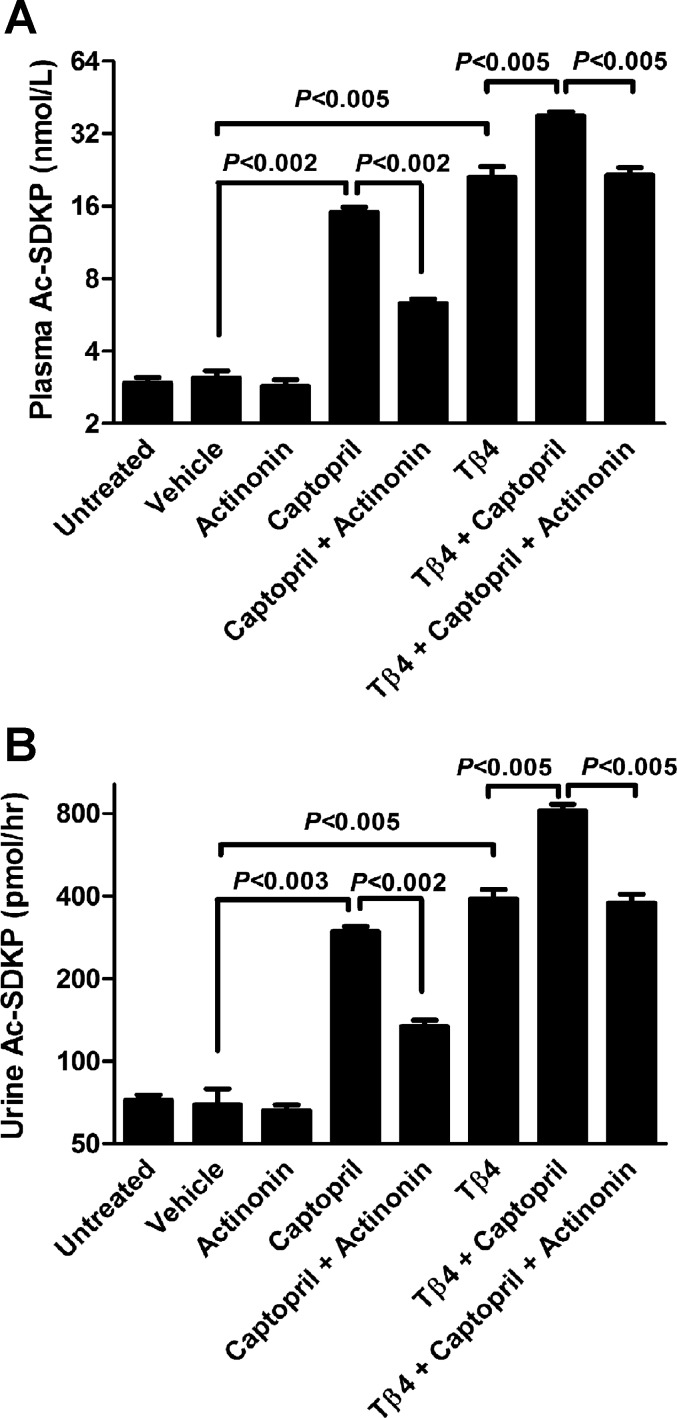

Actinonin significantly inhibited the release of Ac-SDKP from Tβ4 in vivo.

The effects of the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin on the Ac-SDKP concentrations in vivo were measured in the plasma and urine of rats. There were no differences between control-untreated and control-vehicle groups in the Ac-SDKP plasma concentrations (untreated 2.95 ± 0.16 nmol/l, vehicle 3.08 ± 0.22 nmol/l; Fig. 7A). Actinonin-treated rats did not exhibit a decrease in Ac-SDKP concentrations (2.86 ± 0.18 nmol/l plasma) compared with the vehicle-treated rats. Captopril-treated rats had a significantly higher Ac-SDKP concentrations (15.09 ± 0.74 nmol/l plasma) compared with the vehicle-treated animals, and this increase was significantly inhibited by the coadministration of actinonin (6.33 ± 0.26 nmol/l) plasma (Fig. 7A). Tβ4 treatment alone significantly increased Ac-SDKP concentrations (21.03 ± 2.3 nmol/l plasma) compared with the vehicle. We observed a further increase when captopril and Tβ4 were administered together (37.95 ± 1.57 nmol/l plasma; Fig. 7A). This increase was significantly inhibited by the coadministration of actinonin (21.55 ± 1.56 nmol/l plasma; Fig. 7A). We obtained similar results with urinary Ac-SDKP content after different treatments: control-untreated 72.29 ± 3.41 pmol/h, control-vehicle 69.37 ± 9.91 pmol/h, actinonin 65.95 ± 3.50 pmol/h, captopril 297.62 ± 12.54 pmol/h, captopril + actinonin 133.80 ± 7.38 pmol/h, Tβ4 391.23 ± 31.58 pmol/h, Tβ4 + captopril 814.46 ± 52.74 pmol/h, and Tβ4 + captopril + actinonin 378.29 ± 27.89 pmol/h (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Effect of the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin on the release of Ac-SDKP in vivo. Ac-SDKP concentration in the plasma (A) and urine (B) of rats treated with actinonin (20 mg/kg), captopril (50 mg/kg), and Tβ4 (20 mg/kg) either alone or in combinations (n = 6–9 in each group). Note that the scales on ordinates are different in A and B. All data are expressed as means ± SE.

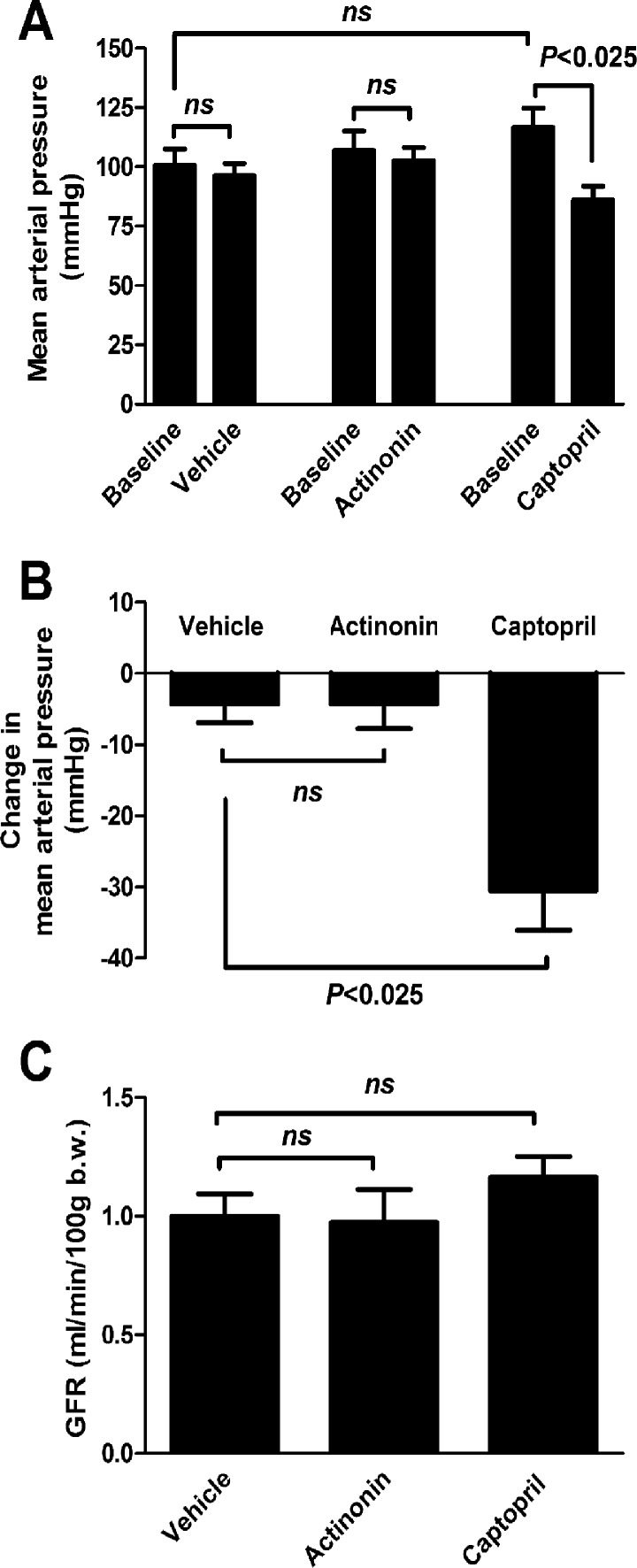

Captopril, but not actinonin, decreased the blood pressure in rats.

The effects of the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor captopril on the blood pressure and GFR were measured in rats. Captopril significantly decreased the MAP by 30.50 ± 5.56 mmHg compared with vehicle (4.33 ± 2.53 mmHg) and actinonin (4.25 ± 3.48 mmHg) (Fig. 8, A and B). On the other hand, GFR was unaffected by actinonin (0.97 ± 0.14 ml·min−1·100 g body wt−1) or captopril (1.17 ± 0.08 ml·min−1·100 g body wt−1) compared with the vehicle (1.0 ± 0.09 ml·min−1·100 g body wt−1) (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Effect of the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor captopril on the mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in rats. A: MAP before (basal) and after treatments with vehicle (10% ethanol in PBS, pH 7.4), actinonin (20 mg/kg), and captopril (50 mg/kg). B: MAP changes in rats after different treatments. Captopril treatment significantly reduced the MAP, whereas actinonin treatment had no effect on MAP compared with the vehicle treatment. C: GFR did not change significantly with either actinonin or captopril treatment (n = 4 in each group). All data are expressed as means ± SE.

Characterization of peptide fragments released by meprin-α from Tβ4.

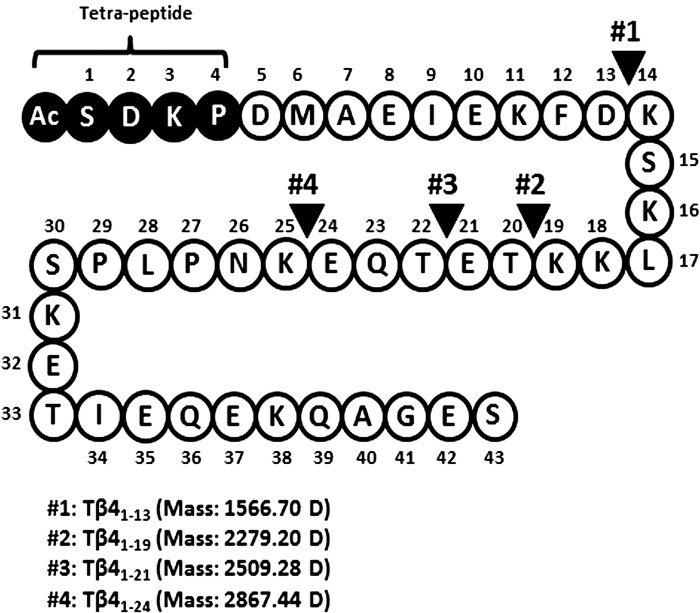

Mass spectrometry was used to determine the mass of peptide fragments released from the full-length Tβ41–43 by meprin-α (Fig. 9). Many peptide fragments were detected after the hydrolysis by meprin-α (Supplemental Table S1; Supplemental Material for this article is available on the AJP-Renal Physiology web site). The most abundant were the peptide fragments with masses corresponding to Tβ41–21 (peptide no. 3; mass: 2,509.28 Da) and Tβ41–24 (peptide no. 4; mass: 2,867.44 Da). These peptides are the expected products of the Tβ4 hydrolysis at the predicted meprin-α cleavage sites at E21-T22 and E24-K25 (41). In addition, data from mass spectrometry revealed two new putative cleavage sites at D13-K14 (peptide no. 1, Tβ41–13; mass: 1,566.70 Da) and K19-T20 (peptide no. 3, Tβ41–19; mass: 2,279.20 Da). This is consistent with the specificity of the active site of meprin-α, which prefers acidic amino acids at positions near and adjacent to its cleavage site (20, 21). Overall, we found four of the most abundant NH2-terminal peptide fragments after Tβ4 hydrolysis by meprin-α that were shorter than 30 amino acids in length and may serve as the substrate(s) for POP in the release of Ac-SDKP. A summary of meprin-α putative cleavage sites on Tβ41–43 is shown in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Amino acid sequence of Tβ4 showing the putative meprin-α cleavage sites. Peptides released after Tβ4 (50 μmol/l) incubation with recombinant meprin-α (20 nmol/l) were analyzed by a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometer. Meprin-α cleavage sites are marked by solid arrowheads. Four NH2-terminal intermediate peptides <30 amino acids released from Tβ4 by meprin-α are shown.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that both meprin-α and POP are required to release Ac-SDKP from its precursor Tβ4. In vitro, incubation of Tβ4 with meprin-α and POP significantly released Ac-SDKP compared with the conditions where Tβ4 was incubated with either meprin-α or POP alone. In addition, in vivo, captopril treatment increased the plasma and urinary Ac-SDKP concentrations, which were inhibited by the coadministration of the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin. Furthermore, we tested the specificity of meprin-α for Tβ4 hydrolysis using kidney tissue from meprin-α KO mice. We found that basal Ac-SDKP concentration was significantly lower in KO mice lacking meprin-α compared with WT mice. Kidney homogenates from meprin-α KO failed to release Ac-SDKP from Tβ4. Taken together, these data suggest a role for meprin-α in proteolytic processing of Tβ4 to release Ac-SDKP.

The antifibrotic, anti-inflammatory, and angiogenic properties of Ac-SDKP have been demonstrated in the pathology of hypertension, heart, renal, diabetes, lung, and liver and in autoimmune diseases (7, 12, 14, 26, 33, 44, 45). However, the mechanism of Ac-SDKP release is not completely understood. Tβ4, a G-actin-sequestering peptide, contains the Ac-SDKP sequence at its NH2-terminal and is the most likely precursor of Ac-SDKP (39). POP is a serine protease widely distributed in mammalian organs (brain, kidney, heart, liver, and muscle) and cleaves peptide bonds at the COOH-terminal end of proline in peptide hormones such as angiotensin, substance P, neurotensin, bradykinin, arginine-vasopressin, and oxytocin and thus may be involved in the biological maturation and degradation of these hormones (36, 46). POP participates in a wide variety of pathophysiological processes, such as inflammation, fibrosis, and angiogenesis (13, 30, 42). Circulating POP activity was significantly decreased in patients suffering from multiple sclerosis (42). Exogenous addition of recombinant POP in vitro increased the tube formation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells in matrigel assay (30). Treatment with a specific POP inhibitor, S17092, in renal injury in rats caused by angiotensin II increased the collagen deposition in heart and kidney, indicating the involvement of POP in alleviating the fibrosis (12). Cavasin et.al. (13) have shown previously that POP is involved in the release of Ac-SDKP from its precursor Tβ4. That study was based on the effect of three POP inhibitors, namely Z-prolyl-prolinal, Fmoc-prolyl-pyrrolidine-2-nitrile, and S17092, which significantly blocked the increase in Ac-SDKP content by kidney homogenates. Since POP hydrolyzes only peptides shorter than 30 amino acids, and since Tβ4 (43 amino acids) is too large to be hydrolyzed by POP (36), it was suggested that an unknown tissue peptidase(s) hydrolyzes Tβ4 in the first step, releasing NH2-terminal intermediate peptide(s) <30 amino acids, and then POP hydrolyzes this intermediate peptide(s) in the second step, finally releasing Ac-SDKP.

Our peptidase database search gave high scores for the zinc proteases, namely meprin-α and matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2), as potential candidates that may hydrolyze Tβ4. Our in vitro study revealed that both meprin-α and POP are required for the release of Ac-SDKP from Tβ4. In contrast, MMP-2 and POP failed to do so. Therefore, we can rule out the involvement of MMP-2 in the release of Ac-SDKP from Tβ4. Furthermore, we and others have shown that rat kidneys express the necessary peptidases for Tβ4 hydrolysis (13, 30). It is interesting that high expression of meprin-α and POP are found in the rodent kidney (8, 17), with high Ac-SDKP excretion in the urine (22). This led us to use kidney tissue in this present study to test our hypothesis that meprin-α and POP are involved in the Ac-SDKP release from Tβ4. Our data showed that actinonin, a natural product from streptomyces and an inhibitor of meprin-α (6), and the POP inhibitor S17092, either alone or together, blocked the increase in Ac-SDKP amount by kidney homogenates. These results indicate that the kidney may serve as the physiological site for Ac-SDKP release. Since meprin-α and POP are also present in other cells and tissues (8, 17, 46), the possibility that Ac-SDKP is released elsewhere cannot be excluded. However, actinonin has been suggested to inhibit the activity of MMP(s) and other enzyme(s) (18, 32). To test the specificity of meprin-α for Tβ4 hydrolysis, we obtained kidney tissue from meprin-α KO mice. These mice do not express meprin-α, but they do express the meprin-β isoform. Meprin-α and meprin-β share many structural features and have few common and unique substrate preferences (8). We found that basal Ac-SDKP content was significantly lower in meprin-α KO mice compared with the WT mice and that Ac-SDKP release from Tβ4 was completely blocked by kidney homogenates from meprin-α KO mice. This indicates that meprin-β isoform is not involved in the Tβ4 hydrolysis and that meprin-α is indeed the main peptidase responsible for the observed Tβ4 hydrolysis into Ac-SDKP in the kidney under normal physiological conditions.

We detected basal Ac-SDKP amounts in the kidneys of meprin-α KO mice, albeit at a lower amount compared with the WT mice. It indicates that peptidase(s) other than meprin-α may also be involved in the Ac-SDKP release. However, our data showed that kidney homogenates from meprin-α KO mice failed to release Ac-SDKP when incubated with exogenous Tβ4 (Fig. 5), indicating that a nonrenal enzyme(s) other than meprin-α may release Ac-SDKP in other tissues. However, meprin-α and POP are still the main peptidases in the release of Ac-SDKP from Tβ4.

It is intriguing that kidney homogenates from C57BL/6 mice incubated with Tβ4 released higher amounts of Ac-SDKP compared with Sprague-Dawley rats. To understand the mechanisms behind this, we tested the enzyme activities of meprin-α and POP, the two peptidases involved in Ac-SDKP release. POP activity, but not meprin-α activity, was significantly higher in the kidney homogenates from mice compared with the rats, indicating that higher POP activity resulted in a higher Ac-SDKP release in mice. It is possible that species differences may influence the process of Ac-SDKP release; different species may have different enzymes' catalytic efficiency to hydrolyze Tβ4. Regardless of the levels of POP or meprin-α activities among rodent species, it is important that meprin-α and POP participated in the Ac-SDKP release from Tβ4 both in rats and mice.

Meprins are highly expressed in the mammalian kidney and intestine (8). Meprin-α is released into the lumen of kidney tubules and intestine, whereas the meprin-β protein isoform is membrane bound (8). Meprins hydrolyze a wide variety of peptides and proteins, such as growth factors, peptide hormones, and extracellular matrix proteins (11); however, their precise physiological role is not clear. The role of meprins has been studied in renal diseases, inflammation, and angiogenesis (4, 10, 20, 27, 38). It has been reported that meprin-β exacerbated the acute kidney injuries, whereas meprin-α was reported to be beneficial (10, 20). Meprin-α displayed proangiogenic properties in cell culture settings and in animal models (27, 38). Furthermore, meprin-α showed anti-inflammatory properties in human patients with ulcerative colitis and in animal models of inflammatory bowel disease (3, 4). Ac-SDKP, the product of Tβ4 hydrolysis by meprin-α and POP, shares very similar properties with meprin-α. It has been reported that Ac-SDKP promotes angiogenesis in cornea (43) and abdominal wall of the rat (26). The anti-inflammatory properties of Ac-SDKP have been shown in pathologies such as renal diseases, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases (31, 45). Thus, the angiogenic and anti-inflammatory properties of Ac-SDKP might explain in part the beneficial effects of meprin-α reported in renal disease, colitis, and angiogenesis.

Ac-SDKP is degraded by ACE, and it is known that treatment of the ACE inhibitor increases plasma and urinary Ac-SDKP content four- to fivefold in rats (22). We observed that rats treated with the ACE inhibitor captopril had a significant increase in the plasma and urinary Ac-SDKP concentrations, and this increase was partially inhibited by the coadministration of the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin. However, endogenous Ac-SDKP in the plasma and urine was not significantly lower in rats treated with the meprin-α inhibitor actinonin alone compared with the rats treated with vehicle. It could be argued that Ac-SDKP in plasma and urine did not decrease significantly because plasma and kidney ACE activity were also inhibited by actinonin, and consequently that would block Ac-SDKP degradation. Therefore, we tested indirectly whether ACE activity is affected during actinonin treatment by measuring the mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) in rats. We found that captopril (ACE inhibitor) significantly reduced the MAP, with no change in GFR. This is in full agreement with the previous reports that showed high dosage of captopril reduced MAP significantly but did not change the GFR (28). However, our study showed that actinonin (a meprin-α inhibitor) did not cause changes in MAP or GFR in rats, suggesting that ACE activity is not affected by actinonin.

Furthermore, we have found that the exogenous administration of Tβ4 increases the Ac-SDKP concentrations in vivo, and this increase was significantly inhibited by actinonin. Zuo et.al. reported recently that when Ac-SDKP release was blocked with the POP inhibitor, Tβ4 treatment showed profibrotic effects; however, Tβ4 without POP inhibitor or Ac-SDKP alone showed antifibrotic effects in the obstructive kidney of mice (47). It is likely that the beneficial effects of Tβ4 may also be due partly to the increase in Ac-SDKP concentrations in these animals.

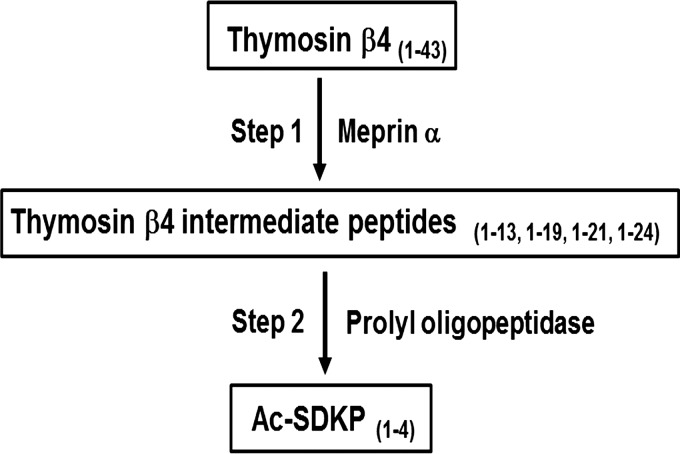

Finally, our mass spectrometry data indicated that meprin-α hydrolyzes full-length Tβ4 to release NH2-terminal intermediate peptides that contain less than 30 amino acids while including the Ac-SDKP sequence. Further cleavage of these NH2-terminal intermediate peptides may allow sequential hydrolysis by POP to finally release Ac-SDKP (Fig. 10). To our knowledge, the current studies are the first to demonstrate the involvement of meprin-α in the release of the anti-inflammatory peptide Ac-SDKP. These data provide new insights on how meprin-α metalloproteases may modulate the inflammatory response.

Fig. 10.

Schematic diagram of sequential hydrolysis of Tβ4. In the first step, meprin-α hydrolyzes Tβ4 into NH2-terminal intermediate peptide(s) <30 amino acids. The second step involves POP hydrolysis of the intermediate peptide(s) that releases Ac-SDKP.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant P01-HL-028982 (O. A. Carretero) and National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant SC3GM102049 (E. M. Ongeri).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

N.K., P.N., and O.A.C. conception and design of research; N.K. and P.N. performed experiments; N.K., P.N., and E.L.P. analyzed data; N.K., P.N., B.J., C.A.R., M.E.W., S.R.M., J.S., F.V., E.M.O., J.-M.V.N., N.-E.R., and O.A.C. interpreted results of experiments; N.K. and M.E.W. prepared figures; N.K. drafted manuscript; N.K., P.N., B.J., C.A.R., M.E.W., S.R.M., E.M.O., N.-E.R., and O.A.C. edited and revised manuscript; N.K., P.N., B.J., C.A.R., M.E.W., S.R.M., E.L.P., J.S., F.V., E.M.O., J.-M.V.N., N.-E.R., and O.A.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gulser Gurocak and Carl Polomoski for their technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Addison ML, Minnion JS, Shillito JC, Suzuki K, Tan TM, Field BC, Germain-Zito N, Becker-Pauly C, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR, Murphy KG. A role for metalloendopeptidases in the breakdown of the gut hormone, PYY 3–36. Endocrinology 152: 4630–4640, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azizi M, Ezan E, Nicolet L, Grognet JM, Menard J. High plasma level of N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline: a new marker of chronic angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Hypertension 30: 1015–1019, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee S, Jin G, Bradley SG, Matters GL, Gailey RD, Crisman JM, Bond JS. Balance of meprin A and B in mice affects the progression of experimental inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300: G273–G282, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee S, Oneda B, Yap LM, Jewell DP, Matters GL, Fitzpatrick LR, Seibold F, Sterchi EE, Ahmad T, Lottaz D, Bond JS. MEP1A allele for meprin A metalloprotease is a susceptibility gene for inflammatory bowel disease. Mucosal Immunol 2: 220–231, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beligni MV, Lamattina L. Nitric oxide stimulates seed germination and de-etiolation, and inhibits hypocotyl elongation, three light-inducible responses in plants. Planta 210: 215–221, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertenshaw GP, Turk BE, Hubbard SJ, Matters GL, Bylander JE, Crisman JM, Cantley LC, Bond JS. Marked differences between metalloproteases meprin A and B in substrate and peptide bond specificity. J Biol Chem 276: 13248–13255, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bidon-Chanal A, Marti MA, Crespo A, Milani M, Orozco M, Bolognesi M, Luque FJ, Estrin DA. Ligand-induced dynamical regulation of NO conversion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis truncated hemoglobin-N. Proteins 64: 457–464, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broder C, Becker-Pauly C. The metalloproteases meprin α and meprin β: unique enzymes in inflammation, neurodegeneration, cancer and fibrosis. Biochem J 450: 253–264, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler PE, McKay MJ, Bond JS. Characterization of meprin, a membrane-bound metalloendopeptidase from mouse kidney. Biochem J 241: 229–235, 1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bylander J, Li Q, Ramesh G, Zhang B, Reeves WB, Bond JS. Targeted disruption of the meprin metalloproteinase β gene protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F480–F490, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bylander JE, Bertenshaw GP, Matters GL, Hubbard SJ, Bond JS. Human and mouse homo-oligomeric meprin A metalloendopeptidase: substrate and inhibitor specificities. Biol Chem 388: 1163–1172, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavasin MA, Liao TD, Yang XP, Yang JJ, Carretero OA. Decreased endogenous levels of Ac-SDKP promote organ fibrosis. Hypertension 50: 130–136, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavasin MA, Rhaleb NE, Yang XP, Carretero OA. Prolyl oligopeptidase is involved in release of the antifibrotic peptide Ac-SDKP. Hypertension 43: 1140–1145, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen YW, Liu BW, Zhang YJ, Chen YW, Dong GF, Ding XD, Xu LM, Pat B, Fan JG, Li DG. Preservation of basal AcSDKP attenuates carbon tetrachloride-induced fibrosis in the rat liver. J Hepatol 53: 528–536, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cingolani OH, Yang XP, Liu YH, Villanueva M, Rhaleb NE, Carretero OA. Reduction of cardiac fibrosis decreases systolic performance without affecting diastolic function in hypertensive rats. Hypertension 43: 1067–1073, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ezan E, Carde P, Le Kerneau J, Ardouin T, Thomas F, Isnard F, Deschamps de Paillette E, Grognet JM. Pharmcokinetics in healthy volunteers and patients of NAc-SDKP (seraspenide), a negative regulator of hematopoiesis. Drug Metab Dispos 22: 843–848, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goossens F, De Meester I, Vanhoof G, Scharpé S. Distribution of prolyl oligopeptidase in human peripheral tissues and body fluids. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem 34: 17–22, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta KJ, Fernie AR, Kaiser WM, van Dongen JT. On the origins of nitric oxide. Trends Plant Sci 16: 160–168, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hannappel E. beta-Thymosins. Ann NY Acad Sci 1112: 21–37, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herzog C, Marisiddaiah R, Haun RS, Kaushal GP. Basement membrane protein nidogen-1 is a target of meprin beta in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Toxicol Lett 236: 110–116, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jefferson T, Auf dem Keller U, Bellac C, Metz VV, Broder C, Hedrich J, Ohler A, Maier W, Magdolen V, Sterchi E, Bond JS, Jayakumar A, Traupe H, Chalaris A, Rose-John S, Pietrzik CU, Postina R, Overall CM, Becker-Pauly C. The substrate degradome of meprin metalloproteases reveals an unexpected proteolytic link between meprin β and ADAM10. Cell Mol Life Sci 70: 309–333, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Junot C, Nicolet L, Ezan E, Gonzales MF, Menard J, Azizi M. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on plasma, urine, and tissue concentrations of hemoregulatory peptide acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 291: 982–987, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee U, Wie C, Fernandez BO, Feelisch M, Vierling E. Modulation of nitrosative stress by S-nitrosoglutathione reductase is critical for thermotolerance and plant growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20: 786–802, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenfant M, Wdzieczak-Bakala J, Guittet E, Prome JC, Sotty D, Frindel E. Inhibitor of hematopoietic pluripotent stem cell proliferation: purification and determination of its structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 779–782, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao TD, Yang XP, D'Ambrosio M, Zhang Y, Rhaleb NE, Carretero OA. N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline attenuates renal injury and dysfunction in hypertensive rats with reduced renal mass: council for high blood pressure research. Hypertension 55: 459–467, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu JM, Lawrence F, Kovacevic M, Bignon J, Papadimitriou E, Lallemand JY, Katsoris P, Potier P, Fromes Y, Wdzieczak-Bakala J. The tetrapeptide AcSDKP, an inhibitor of primitive hematopoietic cell proliferation, induces angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Blood 101: 3014–3020, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lottaz D, Maurer CA, Noël A, Blacher S, Huguenin M, Nievergelt A, Niggli V, Kern A, Müller S, Seibold F, Friess H, Becker-Pauly C, Stöcker W, Sterchi EE. Enhanced activity of meprin-α, a pro-migratory and pro-angiogenic protease, in colorectal cancer. PLoS One 6: e26450, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendelsohn FA, Kachel C. Production of angiotensin converting enzyme by cultured bovine endothelial cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 8: 477–481, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milani M, Pesce A, Ouellet Y, Dewilde S, Friedman J, Ascenzi P, Guertin M, Bolognesi M. Heme-ligand tunneling in group I truncated hemoglobins. J Biol Chem 279: 21520–21525, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myöhänen TT, Tenorio-Laranga J, Jokinen B, Vázquez-Sánchez R, Moreno-Baylach MJ, García-Horsman JA, Männistö PT. Prolyl oligopeptidase induces angiogenesis both in vitro and in vivo in a novel regulatory manner. Br J Pharmacol 163: 1666–1678, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakagawa P, Liu Y, Liao TD, Chen X, Gonzalez GE, Bobbitt KR, Smolarek D, Peterson EL, Kedl R, Yang XP, Rhaleb NE, Carretero OA. Treatment with N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline prevents experimental autoimmune myocarditis in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303: H1114–H1127, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pankow K, Wang Y, Gembardt F, Krause E, Sun X, Krause G, Schultheiss HP, Siems WE, Walther T. Successive action of meprin A and neprilysin catabolizes B-type natriuretic peptide. Circ Res 101: 875–882, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng H, Carretero OA, Brigstock DR, Oja-Tebbe N, Rhaleb NE. Ac-SDKP reverses cardiac fibrosis in rats with renovascular hypertension. Hypertension 42: 1164–1170, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng H, Carretero OA, Liao TD, Peterson EL, Rhaleb NE. Role of N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline in the antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor captopril in hypertension. Hypertension 49: 695–703, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng H, Carretero OA, Vuljaj N, Liao TD, Motivala A, Peterson EL, Rhaleb NE. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: a new mechanism of action. Circulation 112: 2436–2445, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polgar L. The prolyl oligopeptidase family. Cell Mol Life Sci 59: 349–362, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhaleb NE, Pokharel S, Sharma U, Carretero OA. Renal protective effects of N-acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive mice. J Hypertens 29: 330–338, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schutte A, Hedrich J, Stöcker W, Becker-Pauly C. Let it flow: Morpholino knockdown in zebrafish embryos reveals a pro-angiogenic effect of the metalloprotease meprin alpha2. PLoS One 5: e8835, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shiva S, Huang Z, Grubina R, Sun J, Ringwood LA, MacArthur PH, Xu X, Murphy E, Darley-Usmar VM, Gladwin MT. Deoxymyoglobin is a nitrite reductase that generates nitric oxide and regulates mitochondrial respiration. Circ Res 100: 654–661, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sterchi EE, Naim HY, Lentze MJ, Hauri HP, Fransen JA. N-benzoyl-l-tyrosyl-p-aminobenzoic acid hydrolase: a metalloendopeptidase of the human intestinal microvillus membrane which degrades biologically active peptides. Arch Biochem Biophys 265: 105–118, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stohr C, Ullrich WR. Generation and possible roles of NO in plant roots and their apoplastic space. J Exp Bot 53: 2293–2303, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tenorio-Laranga J, Coret-Ferrer F, Casanova-Estruch B, Burgal M, García-Horsman JA. Prolyl oligopeptidase is inhibited in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation 7: 23, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang D, Carretero OA, Yang XY, Rhaleb NE, Liu YH, Liao TD, Yang XP. N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline stimulates angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2099–H2105, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu H, Yang F, Sun Y, Yuan Y, Cheng H, Wei Z, Li S, Cheng T, Brann D, Wang R. A new antifibrotic target of Ac-SDKP: inhibition of myofibroblast differentiation in rat lung with silicosis. PLoS One 7: e40301, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang F, Yang XP, Liu YH, Xu J, Cingolani O, Rhaleb NE, Carretero OA. Ac-SDKP reverses inflammation and fibrosis in rats with heart failure after myocardial infarction. Hypertension 43: 229–236, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu M, Lamattina L, Spoel SH, Loake GJ. Nitric oxide function in plant biology: a redox cue in deconvolution. New Phytol 202: 1142–1156, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zuo Y, Chun B, Potthoff SA, Kazi N, Brolin TJ, Orhan D, Yang HC, Ma LJ, Kon V, Myohanen T, Rhaleb NE, Carretero OA, Fogo AB. Thymosin beta4 and its degradation product, Ac-SDKP, are novel reparative factors in renal fibrosis. Kidney Int 84: 1166–1175, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]