Significance

MLN4924, a potent small-molecule inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme, blocks cullin-RING ligase activity through inhibiting cullin neddylation. MLN4924 is widely used in both preclinical and clinical settings for an anticancer application. We report here an unexpected finding: MLN4924 at nanomolar concentration stimulates stem cell proliferation, self-renewal, and differentiation in both tumor and normal stem cell models and promotes skin wound healing in a mouse model and cell migration in vitro. Mechanistic studies revealed that MLN4924 causes c-MYC accumulation and promotes EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) dimerization to activate the EGFR signaling pathway. Our study raises a concern in anticancer application of MLN4924, but at the same time provides an opportunity for future development of MLN4924 as an agent for stem cell therapy and tissue regeneration.

Keywords: MLN4924, neddylation, EGFR, stem cell, wound healing

Abstract

MLN4924, also known as pevonedistat, is the first-in-class inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme, which blocks the entire neddylation modification of proteins. Previous preclinical studies and current clinical trials have been exclusively focused on its anticancer property. Unexpectedly, we show here, to our knowledge for the first time, that MLN4924, when applied at nanomolar concentrations, significantly stimulates in vitro tumor sphere formation and in vivo tumorigenesis and differentiation of human cancer cells and mouse embryonic stem cells. These stimulatory effects are attributable to (i) c-MYC accumulation via blocking its degradation and (ii) continued activation of EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) and its downstream pathways, including PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK, via inducing EGFR dimerization. Finally, MLN4924 accelerates EGF-mediated skin wound healing in mouse and stimulates cell migration in an in vitro culture setting. Taking these data together, our study reveals that neddylation modification could regulate stem cell proliferation and differentiation and that a low dose of MLN4924 might have a therapeutic value for stem cell therapy and tissue regeneration.

In cells, homeostasis is reached by a fine balance between the rates of protein synthesis and degradation. The process of protein degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) involves two sequential steps: (i) ubiquitylation catalyzed by the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), and a ubiquitin ligase (E3) and (ii) degradation catalyzed by 26S proteasome (1). Abnormal UPS activity abrogates the homeostasis and is associated with many human diseases, including cancer (2, 3). Bortezomib, the first Food and Drug Administration-approved proteasome inhibitor for the treatment of multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma (4), possesses significant cytotoxicity against normal cells due to its universal inhibition of the UPS (5). This stimulated an intensive search for inhibitors targeting the enzymes upstream of the proteasome for improved specificity.

Cullin-RING ligases (CRLs), consisting of scaffold cullins, adaptor proteins, substrate-recognizing receptors, and RING finger proteins, are the largest family of E3 ubiquitin ligases and are responsible for the ubiquitylation of about 20% of all cellular proteins (6, 7). The activity of CRLs requires neddylation of the cullin proteins (8, 9), a ubiquitylation-like process, which is sequentially catalyzed by three enzymes: a NEDD8-activating enzyme (NAE or E1), NEDD8-conjugating enzyme (E2), and NEDD8 ligase (E3). Abnormal elevation of CRL activity has been found in multiple human cancers, which makes them favorable targets for cancer treatment (10, 11).

MLN4924 was descried in 2009 as the first-in-class NAE inhibitor exclusively in the application for cancer treatment by inactivation of CRLs via blockage of cullin neddylation (7). Since the initial report, more than 150 papers (by PubMed search) were published to show its preclinical anticancer activity, either acting alone or in combination with current chemotherapy and/or radiation (6, 11). One of the seven clinical trials of MLN4924 (NCT00911066) was published recently, concluding a modest effect of MLN4924 against acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (12).

To further elucidate the role of blocking neddylation in cancer treatment, we thought to study the effect of MLN4924 on cancer stem cells (CSCs) or tumor-initiating cells (TICs), a small group of tumor cells with stem cell properties that have been claimed to be responsible for cancer initiation and relapse (13). Meanwhile, a recent study showed that pharmacological inactivation of SKP2 SCF (SKP1–Cullins–F-box proteins) E3 ubiquitin ligase (also known as CRL1) by a small molecule inhibitor, compound 25, could restrict CSC traits and cancer progression in prostate cancer (14).

To our utter surprise, we found that at low drug concentrations (30–100 nM), MLN4924 stimulates in vitro tumor sphere (TS) formation and in vivo tumorigenesis of both cancer cells and embryonic stem cells. Mechanistic studies revealed the involvement of accumulation of c-MYC, and dimerization and activation of EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor). We also found that MLN4924 could accelerate the process of EGF-induced skin wound healing in mouse and cell migration in an in vitro culture setting. Thus, MLN4924, when applied at low concentrations, may have potential utility in the field of stem cell therapy and tissue regeneration.

Results

Bipolar Effects of MLN4924 on Proliferation of Cancer Cells.

Suppression of cancer cell growth by MLN4924 has been well-documented in the literature (for a review, see ref. 11). Indeed, we found a dose-dependent growth inhibition in multiple human cancer cell lines, including H1299 (lung cancer), MCF7 and SUM159 (breast cancer), and HCT116 (colorectal cancer), when cultured in the media containing 10% (vol/vol) or 1% serum (Fig. S1 A and B). Unexpectedly, when cultured in serum-free medium, we observed various degrees of dose-dependent growth stimulation at low MLN4924 concentrations (30–300 nM) in H1299 [maximum effective concentration (ECmax), 0.1 μM, P < 0.0001 (Fig. S1A)], HCT116 (ECmax, 0.3 μM, P < 0.0001) (Fig. S1B), MCF7 (ECmax, 0.1 μM, P = 0.0001) (Fig. S1B), and SUM159 (ECmax, 0.1 μM, P = 0.0098) (Fig. S1B) cells, followed by growth suppression at higher concentrations. We confirmed via trypan blue exclusion assay that the number of living cells was indeed significantly increased following treatment with a low dose of MLN4924 under serum-free conditions (Fig. S1C) (P < 0.0001). Collectively, we uncovered the bipolar effects of MLN4924 on cell proliferation, both stimulatory and inhibitory, on cancer cells depending on serum and drug concentrations. We then focused our study on the growth-stimulating effect of MLN4924.

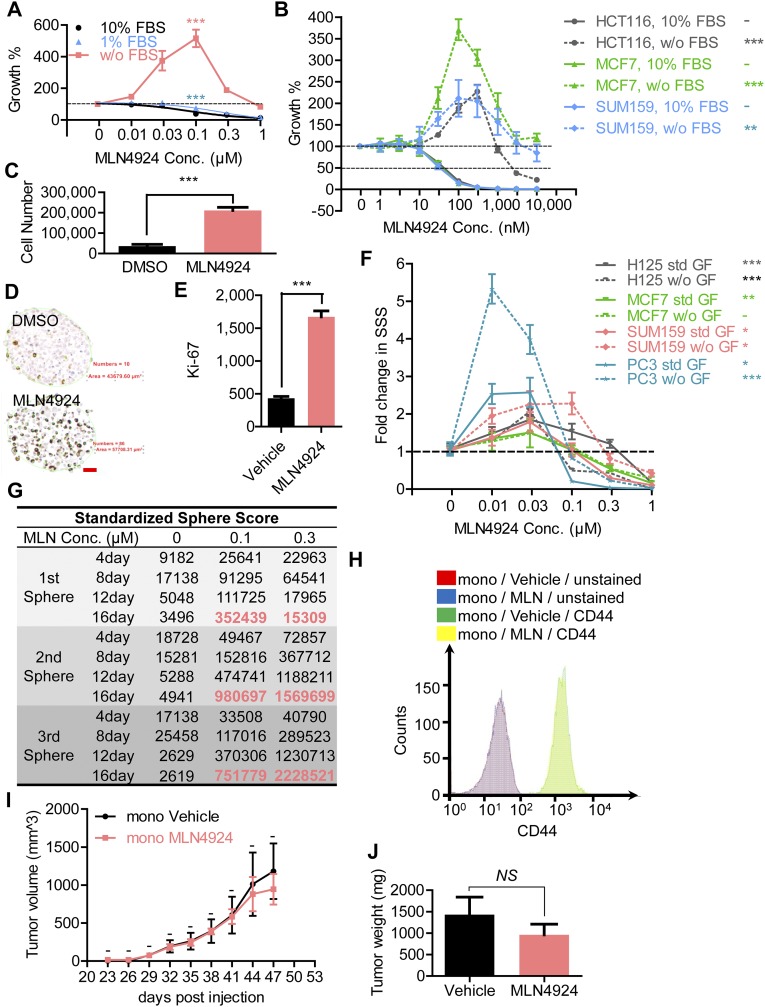

Fig. S1.

MLN4924 stimulates TS formation and in vivo tumorigenesis. (A and B) Effect on cell proliferation, assayed by ATPLite. H1299 cells (A) and multiple lines of human cancer cells (B) were plated in a 96-well plate for attached growth in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1% and 10% (vol/vol) FBS or without FBS and treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of MLN4924. Proliferation was assessed by ATPLite assay after 72 h. Fold-changes in cell growth were calculated by arbitrarily setting the vehicle as 1 and were plotted against dose. (C) Effect on cell proliferation, assayed by Trypan blue exclusion counting. H1299 cells were plated in six-well plate in serum-free RPMI 1640 and treated with or without 0.1 μM MLN4924 for 72 h. Cells were harvested, disassociated, stained with Trypan blue dye, and counted by hemocytometer. (D and E) Effect on TS formation, assayed by IHC. H1299 TSs cultured in vehicle or 0.1 μM MLN4924 were harvested and sectioned for Ki67 staining (D). Number of Ki67+ cells in 10 randomly selected sections from different spheres in the vehicle or 0.1-μM MLN4924-treated group was counted and divided by the sum of areas of the 10 sections from their respective group (E). (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (F) Effect on TS formation in multiple lines of human cancer cells. Indicated cancer cell lines were plated at clonal density in TS medium in 24-well ULA plates and treated with indicated concentrations of MLN4924. SSSs were documented at 16 d. Fold-change in SSSs was calculated by arbitrarily setting the SSS of vehicle-treated wells as 1 and was plotted against dose. (G) Value of SSS of serial TS formation assay. Primary TSs (first) were generated by culturing H1299 in TS medium (500 cells per 2 mL TS medium per well) and were treated with the indicated concentration of MLN4924 for 16 d. Primary TSs from 0.1-μM MLN4924-treated groups were harvested, disassociated, and replated at the same cell density to generate secondary (second) TSs for 16 d. Tertiary (third) TSs were generated from 0.1-μM MLN4924-treated secondary TSs in the same way. SSSs were documented at 4-d intervals. (H) Effect on CD44 staining in monolayer cultured cells. H1299 cells cultured in monolayer vehicle or 0.1 μM MLN4924 for 72 h were harvested, disassociated, stained with anti–CD44-Alexa700, and analyzed by FACS. Unstained cells from both groups served as control. (I and J) In vivo growth of TS-derived tumor cells in nude mice. H1299 TSs cultured in vehicle or 0.1 μM MLN4924 for 8 d were harvested, disassociated, and 1:1 mixed with matrigel, before being injected subcutaneously in the left or right flank region, respectively (50,000 cells per injection for both groups). Tumor volumes were measured in 3-d intervals (I). Weights of explanted tumors from both groups were measured at the end of the experiment (J). Shown are mean ± SEM (n = 5).

MLN4924 Stimulates TS Formation in Multiple Cancer Cell Lines.

The observation that MLN4924 at low concentrations stimulated cell growth under serum-starved conditions triggered us to test whether MLN4924 would promote TS formation, an assay widely used to study the stem cell potential in a serum-free suspension culture (15). We first tested H1299 nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells that formed typically spherical TSs in standard conditioned TS medium (16). We found a significant dose-dependent stimulation by MLN4924 on TS formation with an ECmax of 100 nM, followed by a dose-dependent inhibition of TS formation, with 1 μM MLN4924 completely disrupting TS formation (Fig. 1A). To quantify, we used our recently developed Standardized Sphere Score (SSS) (16) as the assessment parameter and found that 0.1 μM MLN4924 induced a greater than 30-fold increase in SSS in H1299 cells (Fig. 1B) (P < 0.0001). The stimulation was also time dependent, despite the fact that no medium change or growth factor replenishment was performed throughout the entire assay period of up to 16 d (Fig. 1C) (P = 0.013 at 4 d and P < 0.0001 at 8, 12, and 16 d). It is worth noting that although TSs did not appear to grow bigger in 0.1-μM MLN4924-treated groups (Fig. 1A) from the 12-d to the 16-d time points, a more than twofold increase in SSS was observed (Fig. 1C) (P = 0.0077), suggesting that those TSs with the largest size might have reached the maximal growth capacity, possibly as a result of central necrosis (17), whereas smaller TSs continued to grow, giving rise to a higher SSS at the later time point.

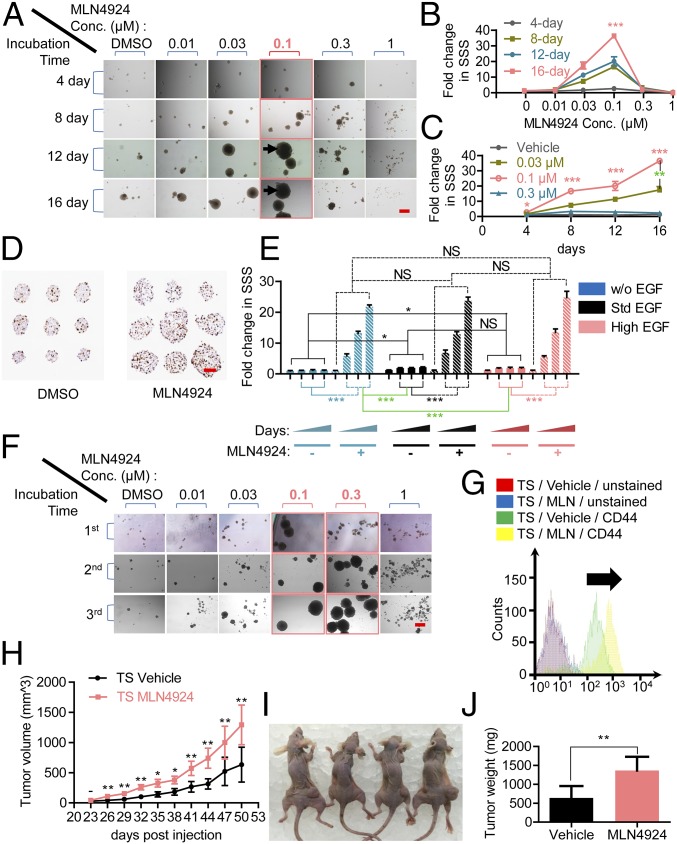

Fig. 1.

MLN4924 stimulates TS formation and in vivo tumorigenesis. (A–C) H1299 TS formation assay. H1299 cells were plated at clonal density in the TS medium in 24-well ULA plates and treated with the indicated concentration of MLN4924 for up to 16 d. Representative pictures were taken (A) and SSSs were documented at 4-d intervals. Fold-changes in SSSs were calculated by arbitrarily setting the SSS of vehicle treated wells as 1 and were plotted against dose (B) and time (C). (D) Ki67 staining of H1299 TS. H1299 TS cultured in DMSO (vehicle control) and 0.1 μM MLN4924 were harvested and sectioned for Ki67 staining. (E) Effect of MLN4924 on TS formation in the presence or absence of EGF. H1299 cells were plated for TS formation in TS medium supplemented with 20 ng/mL EGF (Std, black), 1,000 ng/mL EGF (High, pink), or without EGF (w/o, blue) and treated with (sliced columns) or without 0.1 μM MLN4924 (solid columns) for up to 16 d. Columns represented fold-change in SSSs at 4, 8, 12, and 16 d by arbitrarily setting the SSS of “Std, 4 day, without MLN4924” as 1. (F) Serial TS formation assay of H1299 cells. Primary TSs (first) were generated by culturing H1299 in TS medium (500 cells per 2 mL TS medium per well) and were treated with the indicated concentration of MLN4924 for 16 d. Primary TSs from 0.1 μM MLN4924-treated groups were harvested, disassociated, and replated at the same cell density to generate secondary (second) TSs for 16 d. Tertiary (third) TSs were generated from 0.1 μM MLN4924-treated secondary TSs in the same way. (G) Effect on CD44 staining in H1299 TSs. H1299 TSs cultured in monolayer vehicle or 0.1 μM MLN4924 for 8 d were harvested, disassociated, and stained with anti–CD44-Alexa700 and analyzed by FACS. Unstained cells from both groups served as control. (H–J) H1299 xenograft assays in nude mice. After being mixed with vehicle or 0.1 μM MLN4924, H1299 cells (5 × 105) were immediately injected subcutaneously in the left or right flank region, respectively. Tumor volumes were measured at 3-d intervals (H). Mice were euthanized at 50 d postinjection (I). Weights of tumors from both groups were measured at the end of this experiment (J). Error bars represent the SEM (n = 8). (Scale bars, 500 μm.)

To further confirm the stimulatory effect of MLN4924 on TS formation, we harvested TSs cultured in MLN4924 (0.1 μM), along with the vehicle control, and performed Ki67 staining on TS sections (Fig. 1D). We quantified the result by dividing the number of Ki67+ cells by the area of each respective section (Fig. S1D) and found a significantly higher ratio of Ki67+ cells in TSs cultured with 0.1 μM MLN4924 (Fig. S1E) (P < 0.0001).

Given that MLN4924 stimulated proliferation of monolayer-cultured cancer cells in the absence of any serum or growth factors (Fig. S1 A and B), we next determined whether MLN4924 could stimulate TS formation under EGF-free TS medium. Although, as expected, TS formation was significantly impaired without EGF supplementation, MLN4924 alone was indeed capable of inducing TS formation in H1299 cells in TS medium without EGF supplementation (Fig. 1E, blue bars) (P < 0.0001). The same stimulating effect, to various extents, was also observed in other human cancer cell lines that form typical TSs in our conditioned TS medium, including H125 (NSCLC), MCF7/SUM159 (breast cancer), and PC3 (prostate cancer) (Fig. S1F).

We next directly compared the TS-stimulating activity between MLN4924 and EGF given at the standard concentration (20 ng/mL) or much higher concentration (1,000 ng/mL). As expected, addition of standard as well as high concentrations of EGF significantly promoted TS formation (Fig. 1E, blue solid bars versus black solid bars, P = 0.0218; blue solid bars versus red solid bars, P = 0.0252) but in an EGF concentration-independent manner (Fig. 1E), suggesting that EGF was probably already saturated in the standard condition. Surprisingly, MLN4924 alone at 0.1 μM remarkably stimulated TS formation with about 10-fold more effectiveness than EGF (Fig. 1E) (P < 0.0001). More importantly, a combination of either a standard or high concentration of EGF did not seem to further enhance MLN4924 activity (Fig. 1E). Taken together, it appears that MLN4924 at low concentrations is an effective stimulator of TS formation with an activity that is much greater than EGF.

MLN4924 Stimulates Self-Renewal and Increases the Level of Stem Cell Marker CD44.

Self-renewal is one of the key features of stem cells (13). The capability of TSs being serially passaged is indicative of self-renewal (18). We next determined the effect of MLN4924 on stem cell self-renewal. A single-cell suspension was prepared by enzymatic and mechanic disassociation of H1299 TS formed in 0.1 μM MLN4924-containing culture (first generation of TSs) and replated for the formation of the next generation of TSs in the presence of vehicle control or indicated concentrations of MLN4924. The results showed that H1299 cells that originated from TSs cultured in MLN4924 were capable of forming new TSs, indicating the self-renewal ability of these cells (Fig. 1F, red frame). Interestingly, ECmax of secondary and tertiary TSs shifted from 0.1 μM to 0.3 μM (Fig. 1F and Fig. S1G, red). A possible explanation is that tumor cells became more resistant to the growth inhibitory effect of MLN4924 after being cultured for primary TS formation in MLN4924. In addition, maximal secondary and tertiary SSSs in 0.1 μM MLN4924 culture were significantly larger than that of primary SSSs (Fig. S1G, red), suggesting a higher percentage of CSCs in TSs than in monolayer culture, which is consistent with a previous report (19).

CD44, a cell surface glycoprotein functioning as a receptor for hyaluronic acid (HA), is involved in cell-to-cell interactions, cell adhesion, and migration (20). Many normal stem cells express CD44, including ESCs (21). CD44 has also been established as a CSC marker in multiple human cancers (22), including lung cancer (23). We found that H1299 TSs cultured in 0.1 μM MLN4924 expressed significantly higher levels of CD44 compared with the TSs cultured in vehicle control (Fig. 1G), whereas MLN4924 had no effect on CD44 expression when cells were cultured in monolayer (Fig. S1H). Thus, MLN4924 appears to maintain stem cell self-renewal and enrich the CSC population in TS culture.

MLN4924 Stimulated in Vivo Tumorigenesis.

We next extended our in vitro observations to an in vivo xenograft tumor model by determining whether MLN4924 at a low concentration would stimulate tumor growth in nude mice. We designed and performed two experiments. In the first experiment, we compared the in vivo tumorigenicity of cells that originated from TS cultured in 0.1 μM MLN4924 (with a higher proliferation index) (Fig. 1D and Fig. S1 D and E) versus TSs cultured in vehicle control by subcutaneous implantation in the right and left flank region, respectively, of BALB/c background SCID NCr immunodeficient mice (Charles River). Unexpectedly, no difference in tumorigenicity was observed (Fig. S1 I and J), suggesting that without continuous exposure to MLN4924, enhanced proliferation of cancer cells cannot be sustained in vivo. Thus, we suspected that the proliferation-promoting effect of MLN4924 is transient if cells are not continuously exposed to MLN4924.

We, therefore, conducted the second in vivo experiment, in which we mimicked the in vitro setting by subcutaneously implanting unselected H1299 cells from monolayer culture mixed with 0.1 μM MLN4924 or vehicle control in the right or left flank of the same strain of nude mice, respectively. No MLN4924 was given after initial implantation. The results showed that MLN4924 significantly promoted in vivo tumorigenesis of H1299 cells with an accelerated growth rate (Fig. 1H) (P = 0.0021 at 50 d) and had much bigger tumor size at 50 d postimplantation (Fig. 1 I and J) (P = 0.002).

MLN4924 Stimulates in Vitro Proliferation of mESC and Embryonic Body Formation.

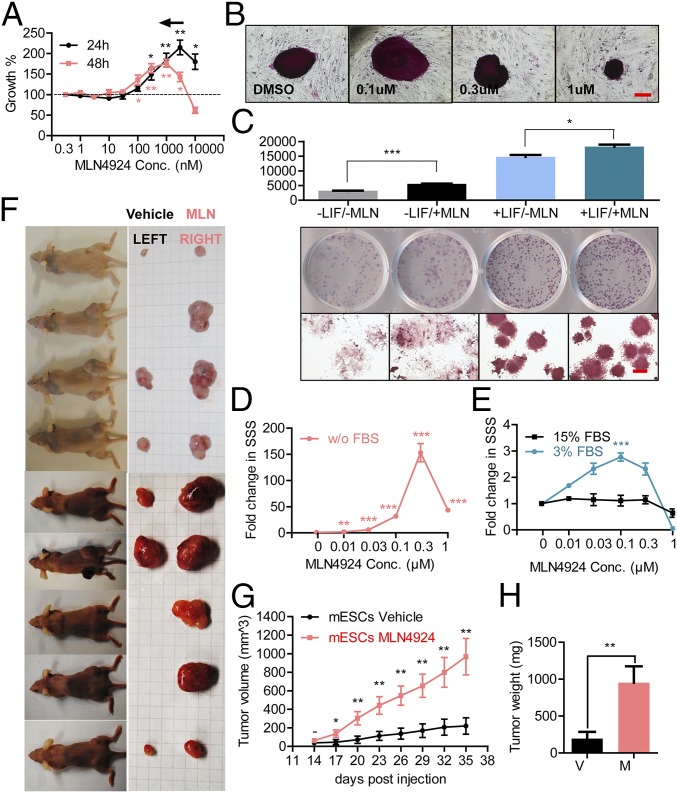

We next determined potential effects of MLN4924 on the proliferation of normal stem cells using mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) as a model. In the feeder-free mESC culturing system [supplemented with leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) to maintain an undifferentiated state of mESC] (24), a bipolar effect of MLN4924 on proliferation was again observed. Significant stimulation of proliferation was observed at the dose range of 0.1∼3 μM (ECmax at 24 h, 3 μM, P = 0.0034; ECmax at 48 h, 1 μM, P = 0.0041), followed by growth suppression at higher concentrations (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

MLN4924 stimulates proliferation of mESCs both in vitro and in vivo. (A) Proliferation assay of mESCs in feeder-free maintenance culture. mESCs were plated in DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS and LIF in 96-well plates and treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of MLN4924 for up to 48 h. Cell proliferation was assessed by ATPLite assay at 24-h intervals. Fold-change in cell growth was calculated by arbitrarily setting the vehicle as 1 and was plotted against dose. (B) Proliferation assay of mESCs in MEF-feeder culture. mESCs were plated at clonal density (400 cells per well in six-well plates) in MEF-feeder culture supplemented with 15% FBS and treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of MLN4924 for 120 h. AP staining was used to visualize undifferentiated colonies of mESCs (red stain). (C) Proliferation assay of mESCs in feeder-free attached culture in both self-renew and differentiation conditions. mESCs were plated at clonal density (400 cells per well in six-well plates) in DMEM (15% FBS) supplemented with or without LIF and treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of MLN4924 for 120 h. AP staining was used to visualize differentiated (weak, disperse staining) and undifferentiated cells (strong, concentrated staining). ATPLite was used to assess cell proliferation on parallel-cultured unstained cells. (D and E) EB formation assay. mESCs were plated at clonal density in DMEM supplemented with 3% FBS, 15% FBS (E), or without FBS (D) in 24-well ULA plates and treated with the indicated concentration of MLN4924 for 4 d or 16 d, respectively. Fold-change in SSSs was calculated by arbitrarily setting the SSS of vehicle-treated wells as 1 and was plotted against dose. (F–H) mESC xenograft/teratoma assays in nude mice. After being mixed with vehicle or 0.1 μM MLN4924, mESC cells (1 × 105) were immediately injected subcutaneously in the left or right flank region, respectively. Tumor volumes were measured at 3-d intervals (G). Mice were euthanized at day 35 postinjection (F). Tumor weights from both groups were measured at the end of the experiment (H). Length of the side of the smallest square in F is 0.5 cm. Error bars represent the SEM (n = 9). (Scale bars, 500 μm.)

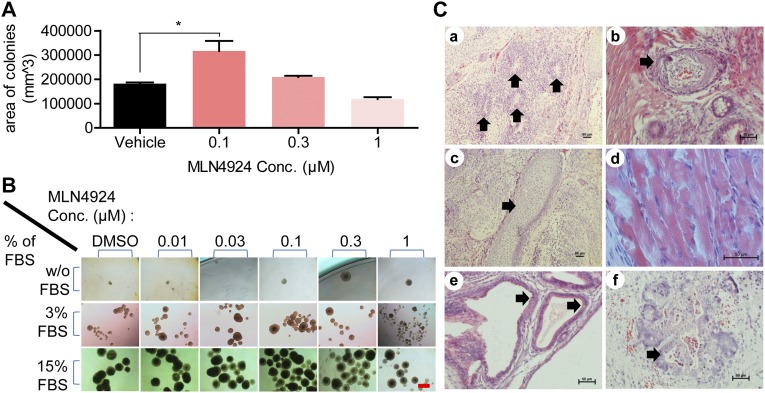

We then plated mESCs at clonal density in an MEF-feeder mESC culturing system to test if MLN4924 could stimulate colony formation under undifferentiated status. Alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining was used to visualize undifferentiated mESC colonies. MLN4924 at a low concentration (0.1 μM) stimulated but at high concentration (1 μM) inhibited colony growth (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2A) (P = 0.0326). No significant effect on the number of colonies was observed.

Fig. S2.

MLN4924 stimulates proliferation of mESCs both in vitro and in vivo. (A) Effect on feeder layer growth. mESCs were plated at clonal density (400 cells per well in a six-well plate) in feeder layer culture supplemented with 15% FBS and treated with vehicle or indicated concentrations of MLN4924 for 120 h, followed by AP staining. Sum of areas of colonies were measured and calculated by computer-based imaging software with the function of taking live measurements (NIS Elements BR). Shown are mean ± SEM (n = 3). (B) Effect on EB formation. mESCs were plated at clonal density in TS medium or DMEM supplemented with 3% or 15% FBS in 24-well ULA plates and treated with indicated concentrations of MLN4924 for 4 d (15% FBS) or 16 d (3% FBS, and TS medium). Representative pictures were taken at 4 d. (Scale bar, 500 μm.) (C) H&E staining of teratomas derived from subcutaneously implanted mESCs mixed with 0.1 μM MLN4924. Teratomas were fixed and processed by H&E staining. Tissues resembling characteristics of three germ layers were found (arrows): (a) neuronal rosettes (ectoderm), (b) squamous epithelium (ectoderm), (c) cartilage (mesoderm), (d) striated muscle (mesoderm), (e) gut-like structure lined with mucinous epithelium (endoderm), and (f) glands (endoderm). (Scale bar, 50 μm.)

We further tested whether MLN4924 would affect mESC differentiation. We plated mESCs in feeder-free culture supplemented with or without LIF. The proliferation of mESCs was measured by ATPLite assay. Undifferentiated and differentiated colonies were assessed by AP staining. The results showed that MLN4924 exhibited a significant stimulatory effect on mESC proliferation under both differentiating and undifferentiating conditions (Fig. 2C) (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0213, respectively).

In suspension culture, mESCs can proliferate to form embryonic body (EB) with a spherical 3D structure (25). We next determined the effect of MLN4924 on mESC proliferation in suspension culture supplemented with LIF in the following three conditions: (i) serum-free but supplemented with 20 ng/mL EGF, (ii) 3% (vol/vol) serum, and (iii) 15% (vol/vol) serum (standard condition). The results showed that 0.1 μM MLN4924 significantly stimulated EB formation under the conditions of serum-free (Fig. 2D and Fig. S2B) (ECmax, 0.3 μM, P < 0.0001) or 3% (vol/vol) FBS (Fig. 2E and Fig. S2B) (ECmax, 0.1 μM, P = 0.0004), but not 15% (vol/vol) FBS (Fig. 2E and Fig. S2B).

MLN4924 Stimulates Teratoma Formation in Vivo.

The subcutaneously implanted mESCs in immunodeficient mice can proliferate and differentiate to form teratoma consisting of multiple tissues from all germ layers (26). We determined whether MLN4924 could promote in vivo mESC proliferation/differentiation by stimulating teratoma formation in nude mice. Similar to our second H1299 xenograft model, we injected matrigel-mixed single cell suspension of mESCs supplemented with 0.1 μM MLN4924 or the vehicle control subcutaneously in the right or left flank of nude mice, respectively. Again, no MLN4924 was administered after implantation. The results showed that MLN4924 significantly stimulated teratoma formation (Fig. 2F), as evidenced by accelerated tumor growth (Fig. 2G) (P = 0.0019 at 35 d) and much larger size of tumors at 35 d postimplantation (Fig. 2H) (P = 0.0037). To show the tumors are indeed teratoma in nature, we sectioned and H&E-stained the tumors and found various tissues derived from all three germ layers, including (i) neuronal rosettes (ectoderm), (ii) squamous epithelium (ectoderm), (iii) cartilage (mesoderm), (iv) striated muscle (mesoderm), (v) gut-like structure lined with mucinous epithelium (endoderm), and (vi) glands (endoderm) (Fig. S2C), confirming that MLN4924 stimulated in vivo proliferation and differentiation of mESCs.

TS Stimulatory Effect of MLN4924 Is Mediated in Part by the c-MYC/FBXW7 Axis.

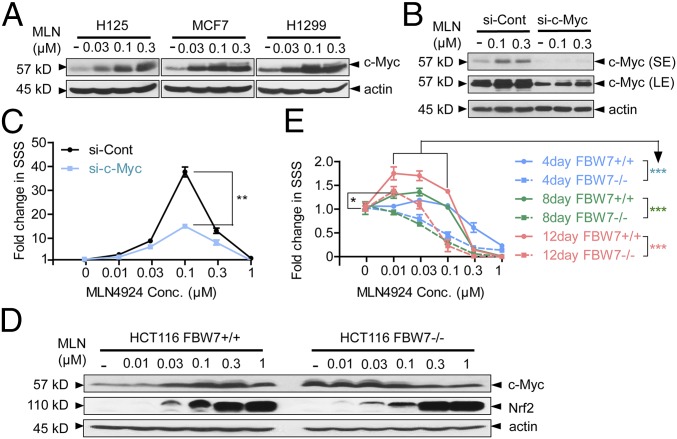

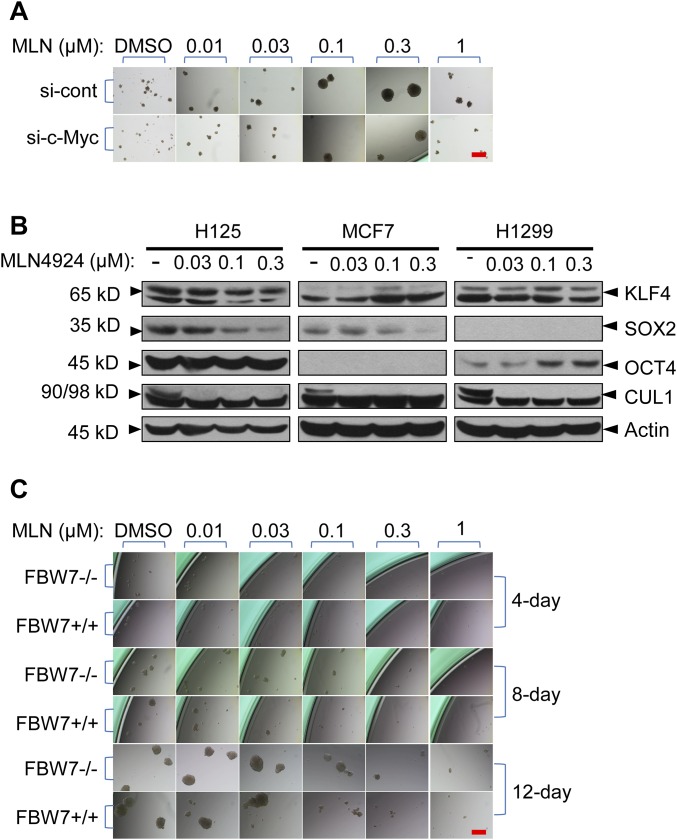

Given that CRL-mediated ubiquitylation and degradation of proteins can be blocked by MLN4924 (6, 11), we hypothesized that MLN4924 might stimulate TS formation by blocking the degradation of oncoproteins or stemness factors that were substrates of CRL. c-MYC is one of the four Yamanaka factors (OCT3/4, SOX2, c-MYC, and KLF4) that are capable of reprogramming fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells (27). C-Myc itself has been shown to play a significant role in self-renewal of stem cells (28). Because it is well-known that c-MYC is subjected to ubiquitylation and degradation by two SCF E3 ubiquitin ligases, SCFFBXW7 (29) and SCFSKP2 (30), we determined whether MLN4924 can cause accumulation of c-MYC by inactivation of cullin neddylation (7). As expected, we observed a dose-dependent increase of c-MYC upon MLN4924 treatment in multiple cell lines (Fig. 3A). We next determined whether c-MYC accumulation was causally related to the TS-stimulating effect of MLN4924. We silenced c-MYC (Fig. 3B) and did observe a significant reduction, but not complete abrogation, of MLN4924-induced TS formation (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3A) (P = 0.003). We also measured the effects of MLN4924 on the protein levels of the other three Yamanaka factors—KLF4, SOX2, and OCT4—and found that the effect was protein- as well as cell line-dependent. Either induction or repression, or even no effect, was observed among the three cancer cell lines tested (Fig. S3B), thus excluding their potential involvement.

Fig. 3.

The stimulatory effect of MLN4924 is partially mediated by c-MYC. (A) MLN4924 enhanced c-MYC levels in H125, MCF7, and H1299 cells dose-dependently. Cells were treated with vehicle (–) or 0.03, 0.1, and 0.3 μM MLN4924 for 24 h before being harvested for Western blot detection of c-MYC. (B) Knockdown of c-MYC in H1299. H1299 cells were transfected with 20 nM of scrambled siRNA (–) or siRNA targeting c-MYC (+) before being treated with vehicle (–) or 0.1 μM and 0.3 μM MLN4924 for 24 h. Western blot was used to detect c-MYC levels. LE, long exposure; SE, short exposure. (C) H1299 TS formation assay with c-MYC knockdown. H1299 cells were transfected with 20 nM of scrambled siRNA (si-Cont) or siRNA targeting c-MYC (+) before being plated for TS formation assay and treated with the indicated concentration of MLN4924 for 16 d. Fold-change in SSSs was calculated by arbitrarily setting the SSS of vehicle-treated wells from each group as 1 and was plotted against dose. (D) Effect of FBW7 knockout on c-MYC levels in the presence or absence of MLN4924. Two isogenic HCT116 cells (FBW7+/+ and FBW7−/−) treated with vehicle (–) or 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, and 0.3 and 1 μM MLN4924 for 24 h before being harvested for Western blot detection of c-MYC and Nrf2. (E) HCT116 (FBW7+/+ and FBW7−/−) TS formation assay. The two isogenic cells were plated at clonal density in TS medium in 24-well ULA plates and treated with the indicated concentration of MLN4924 for up to 12 d. SSSs were documented at 4-d intervals. Fold-change in SSSs was calculated by arbitrarily setting the SSS of vehicle-treated samples from each cell line as 1 and was plotted against dose.

Fig. S3.

Involvement of c-MYC and FBXW7 in MLN4924-induced TS formation. (A) Partial rescue by c-Myc knockdown. H1299 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA or 20 nM siRNA targeting c-MYC, followed by TS formation assay in the presence of indicated concentrations of MLN4924 for 16 d. Shown are representative photos of spheres. (B) Expression of other iPS (induced pluripotent stem cell) factors. Three lines of human cancer cells were treated with various concentrations of MLN4924 for 24 h, followed by Western blot. (C) Effect of FBXW7. Isogenic HCT116 cells (FBXW7+/+ and FBXW7−/−) were plated at clonal density in TS medium in 24-well ULA plates and treated with indicated concentrations of MLN4924 for up to 12 d. Shown are representative photos of spheres taken at 4-d intervals. (Scale bars, 500 μm.)

Given that FBXW7 binds to c-MYC and promotes its degradation (29), we further determined the role of FBXW7 in MLN4924-induced TS formation by using a pair of isogenic HCT116 FBXW7+/+ and HCT116 FBXW7−/− cell lines (31). We first found that although the basal level of c-MYC was higher in null cells, MLN4924 treatment caused a dose-dependent c-MYC accumulation in wild type but not in null cells, even though SCFSKP2 was unaffected (Fig. 3D), indicating that FBXW7 knockout could completely abolish c-MYC accumulation upon MLN4924 treatment. We then tested the response of the two isogenic lines to MLN4924 by TS formation assay and found that MLN4924 could still stimulate TS formation in FBXW7-null cells, although to a less extent than wild-type cells (Fig. 3E and Fig. S3C). Thus, the TS stimulatory effect of MLN4924 is partially mediated by the c-MYC/FBXW7 axis, whereas other signaling pathways may also be involved.

MLN4924 Activates EGFR and Its Downstream Signaling Pathways.

Given that (i) MLN4924 stimulated the TS formation in conditioned culture medium without any supplement of growth factors (EGF and bFGF) and (ii) MLN4924 increased the expression of CD44 in TS, a receptor similar and closely related to EGFR in cancer cells (32), we hypothesized that MLN4924 might also act through activation of growth factor pathways, particularly the EGFR signaling pathways.

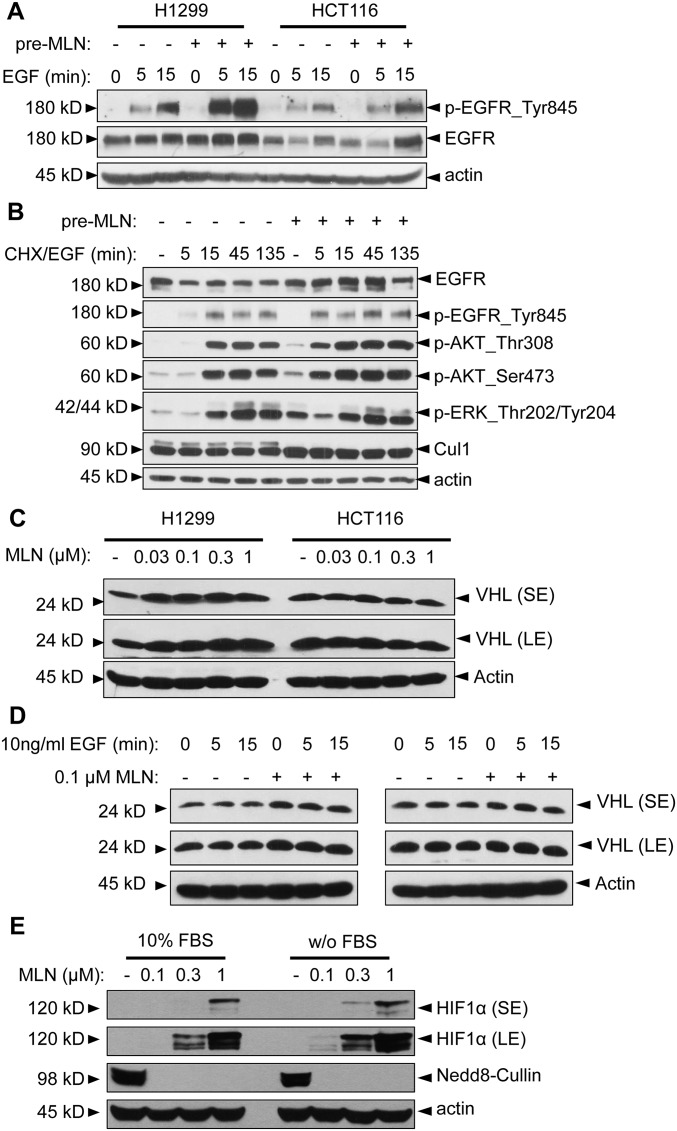

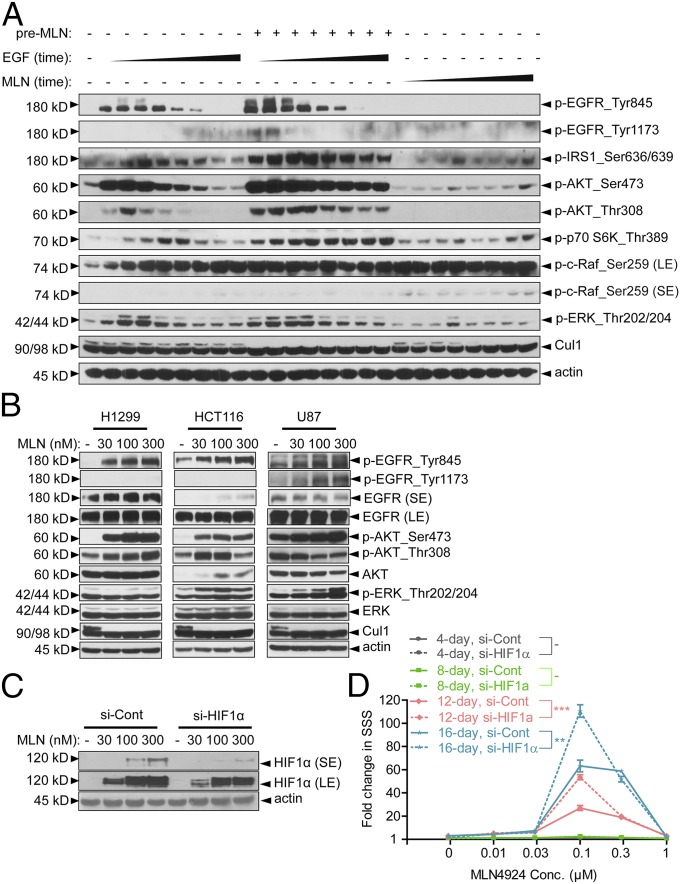

We first found that pretreatment with MLN4924 could enhance EGF-stimulated EGFR phosphorylation and elevate the expression of total EGFR (to a less extent) in H1299 and HCT116 cells (Fig. S4A). We next measured a time-dependent (a period of 2–256 min) activation of EGFR and its downstream signaling pathways by EGF, MLN4924 alone, or the combination of both (with MLN4924 pretreatment for 24 h). Compared with EGF alone, the combination of EGF-MLN4924 caused a greater activation of EGFR itself on Tyr845 and Tyr1173, IRS1 on Ser636/639, AKT on Thr308/Ser473, S6K on Thr389, RAF on Ser259, and ERK on Thr202/Thr204 (Fig. 4A). However, within this shorter exposure time, MLN4924 alone had minor, if any, effect on the activation of EGFR and its downstream pathways (Fig. 4A). Taken together, it appeared that 0.1 μM MLN4924 enhanced and prolonged EGF-induced activation of EGFR and its major downstream signaling pathways, PI3K/AKT/mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) and RAS/RAF/ERK, that are closely related to cell proliferation.

Fig. S4.

MLN4924 activates EGFR and its downstream signaling pathways. (A) MLN4924 enhanced EGF-mediated EGFR phosphorylation. H1299 and HCT116 cells were serum-starved for 24 h, followed by treatment with vehicle (–) or 0.1 μM MLN4924 (+) for another 24 h (pre-MLN). Cells were then stimulated with 10 ng/mL EGF for 5 min and 15 min and subjected to Western blotting using indicated antibodies. (B) MLN4924 blocked EGF-induced EGFR degradation. H1299 cells were serum-starved for 24 h and treated with vehicle (–) or 0.1 μM MLN4924 (+) for another 24 h (pre-MLN). Cells were then treated with 10 ng/mL EGF and 100 μg/mL CHX for 5 min, 15 min, 45 min, and 135 min and harvested for Western blotting using the indicated Abs. (C and D) MLN4924 has no effect on VHL levels. H1299 and HCT116 cells were treated with various concentrations of MLN4924 for 24 h or EGF for the indicated time period alone or in combination. Cells were then subjected to Western blotting, using Ab against VHL. LE, long exposure; SE, short exposure. (E) Induction of HIF1α accumulation. H1299 cells were treated with vehicle (–) or MLN4924 (0.1 μM, 0.3 μM, and 1 μM) for 24 h at 10% and 0% FBS, followed by Western blot to detect the levels of HIF1α. For the “w/o FBS” group, cells were serum-starved for 24 h first before being subjected to vehicle (–) or MLN4924 (0.1 μM, 0.3 μM, and 1 μM) treatment for another 24 h in medium without any serum supplement. LE, long exposure; SE, short exposure.

Fig. 4.

MLN4924 activates EGFR and its downstream signaling pathways. (A) MLN4924 enhanced and prolonged EGF-mediated activation of EGFR and its downstream pathways. H1299 cells were serum-starved for 24 h, followed by treatment with vehicle (–) or 0.1 μM MLN4924 (+) for another 24 h (pre-MLN). Cells were then stimulated with 10 ng/mL EGF or 0.1 μM MLN4924 for 2 min, 4 min, 8 min, 16 min, 32 min, 64 min, 128 min, and 256 min and harvested for Western blot. LE, long exposure; SE, short exposure. (B) MLN4924 alone activated EGFR and its downstream signaling pathways. H1299, HCT116, and U87 cells were serum-starved for 24 h, followed by treatment with vehicle (–) or the indicated concentration of MLN4924 for another 24 h. Cells were then harvested and analyzed by Western blot. (C) Knockdown of HIF1α in H1299. H1299 cells were transfected with 20 nM of scrambled siRNA, or siRNA targeting HIF1α, before being treated with vehicle (0) or 0.1 μM, 0.3 μM, or 1 μM MLN4924 for 24 h. Western blot was used to detect HIF1α levels. (D) H1299 TS formation assay with HIF1α knockdown. H1299 cells were transfected with 20 nM of scrambled siRNA (si-Cont), or siRNA targeting HIF1α (si-HIF1α), before being plated for TS formation assay and treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of MLN4924 for 16 d. Fold-change in SSSs was calculated by arbitrarily setting the SSS of vehicle-treated wells from each group as 1 and was plotted against dose.

We next tested the dose-dependent (0.03, 0.1, and 0.3 μM) effect of MLN4924 alone on the activation of EGFR and its downstream targets after prolonged exposure (24 h). We included three cancer cell lines (H1299, HCT116, and U87) to exclude the possibility of any cell line-dependent effect. The results showed that MLN4924 itself was capable of causing EGFR autophosphorylation at Tyr1173 (U87) and subsequent phosphorylation at Tyr845 (all three cell lines), which was crucial for EGFR kinase activity (33) (Fig. 4B). Dose-dependent increases in AKT phosphorylation at both Thr308 (H1299 and HCT116) and Ser473, and dose-dependent increases in ERK phosphorylation levels was also observed in all three cell lines (Fig. 4B). These results indicated that MLN4924 alone could activate EGFR and its downstream AKT/ERK signaling pathways.

We then determined the effect of MLN4924 on EGF-induced EGFR turnover using CHX (cycloheximide) to block new EGFR synthesis and found that within a time frame of 5–45 min of EGF stimulation, MLN4924 caused a moderate inhibition of EGFR degradation, as evidenced by a moderate increase in EGFR levels, along with a significantly enhanced phosphorylation of EGFR, AKT, and ERK at the 5–15-min time points (Fig. S4B).

Effect of the von Hippel–Lindau/HIF1 Axis on MLN4924-Induced Sphere Formation.

A previous study reported that the VHL (von Hippel–Lindau)/HIF1α oxygen-sensing axis is implicated in the EGFR internalization process, with HIF1 acting as an inhibitor of EGFR endocytosis (34). We, therefore, measured the effect of MLN4924 on the levels of these two proteins in lung and colon cancer cells. We found that MLN4924, when acting alone or in combination with EGF, had minimal, if any, effect on the levels of VHL (Fig. S4 C and D), excluding the involvement of VHL. Our previous study showed that MLN4924 caused accumulation of HIF1α, a well-established substrate of CRL2 in multiple lines of human cancer cells, including HCT116 cells (35). We confirmed that MLN4924 also caused a dose-dependent accumulation of HIF1α in H1299 cells when cultured in either 10% (vol/vol) or 0% serum (Fig. S4E). We then used an siRNA-based knockdown approach to determine if HIF1α plays any role in MLN4924-induced sphere stimulation. We predicted that HIF1α knockdown would reduce sphere formation if HIF1 blocks EGFR endocytosis to prolong EGFR signals in our assay condition, as described in the previous study (34). Unexpectedly, although siHIF1α indeed reduced the level of HIF1α induced by MLN4924 (Fig. 4C), it caused a ∼twofold increase in sphere formation at the 12 d (red) and 16 d (blue) time points (Fig. 4D), suggesting that HIF1α played a negative role in MLN4924-induced sphere stimulation under our setting. We, therefore, excluded the possibility that MLN4924 stimulated TS formation by causing HIF1α accumulation. The underlying mechanism of how lower HIF1α level leads to a stimulation of TS formation by MLN4924 requires further investigation.

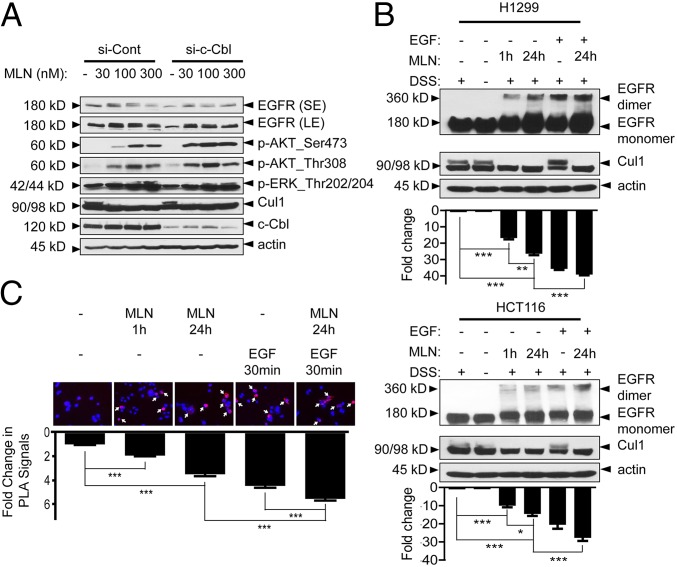

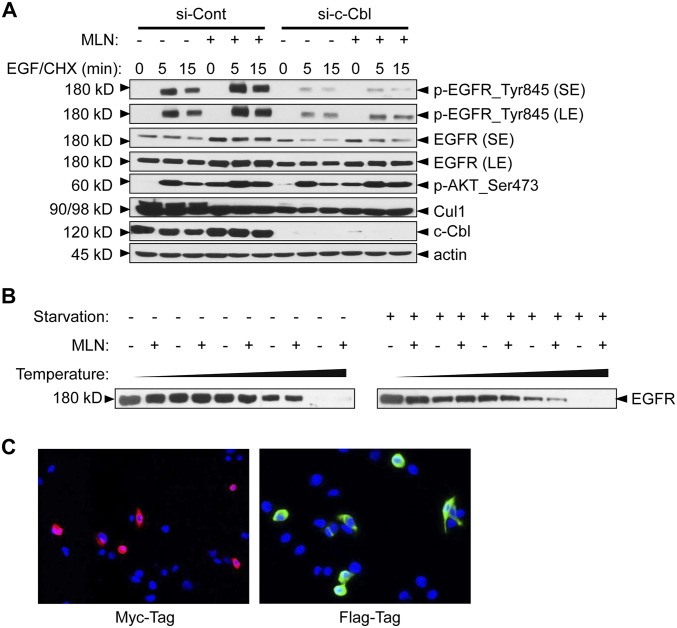

MLN4924-Induced EGFR Activation Is Independent of c-Casitas B-Lineage Lymphoma.

It was reported that c-Cbl (Casitas B-lineage lymphoma) is the E3 ligase for both neddylation and ubiquitylation of EGFR (36, 37). Upon EGF stimulation, c-Cbl promotes EGFR neddylation to facilitate its ubiquitylation and subsequent endocytosis-based degradation (36). Given that MLN4924 is a potent neddylation inhibitor (7), it could inactivate neddylation E3 activity of c-Cbl and block endocytic degradation of EGFR. We, therefore, tested the potential involvement of c-Cbl in MLN4924-induced EGFR activation. We hypothesized that if the MLN effect is mediated through c-Cbl, c-Cbl depletion would abrogate it. However, we observed a minimal, if any, effect of c-Cbl knockdown on total levels of EGFR and EGFR downstream signaling pathways (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, c-Cbl knockdown caused a decrease, rather than an expected increase, in the levels of phosphorylated EGFR and total EGFR and had a minimal effect, if any, on MLN4924-affected EGFR turnover (Fig. S5A). Thus, MLN4924 manipulation of EGFR appeared to be independent of c-Cbl.

Fig. 5.

MLN4924-induced EGFR activation is independent of c-Cbl but is associated with receptor dimerization. (A) c-Cbl has a minimal effect on MLN4924-induced EGFR accumulation. H1299 cells were first transfected with scrambled siRNA (si-Cont) or siRNA targeting c-Cbl (si-c-Cbl), followed by serum starvation for 24 h, and subsequent treatment with vehicle (–) or the indicated concentration of MLN4924 for another 24 h. Cells were then harvested for Western blot. (B) MLN4924 induces EGFR dimerization. H1299 and HCT116 cells were serum-starved for 24 h and then treated with DMSO vehicle control or 0.1 µM MLN4924 for 1 h or 24 h in the presence of the protein cross-linking agent DSS in the last 30 min. For positive control, serum-starved cells were treated with EGF (10 ng/mL) for 30 min in combination with DSS. A combination of MLN4924 and EGFR was also included. Cell lysates were then prepared for Western blot. The band density was quantified using Image J software. Shown are mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. (C) PLA assay to measure EGFR dimerization. EGFR-null CHO cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing EGFR-MYC and EGFR-FLAG and then seeded in coverslips for treatment with MLN4924 or EGF alone or in combination. The slides were stained with primary antibody, followed by staining using the In Situ-Fluorescence kit. Cell images were acquired, and positive-stained cells were quantified. Shown are mean ± SEM from three independent experiments.

Fig. S5.

MLN4924-induced EGFR activation is independent of c-Cbl and VHL. (A) c-Cbl has minimal effect on MLN4924-induced EGFR turnover. H1299 cells were first transfected with siRNA targeting c-Cbl or siCont control, followed by serum starvation for 24 h, and subsequent treatment with vehicle (–) or 0.1 μM MLN4924 for another 24 h. Cells were then treated with 10 ng/mL EGF and 100 μg/mL CHX for 5 min and 15 min, and harvested for Western blotting, using the indicated Abs. (B) Effect on CETSA of EGFR. H1299 were serum-starved for 24 h and pretreated with 10 μM MLN4924 for 1 h before being subjected to thermo-treatment (43 °C, 45 °C, 47 °C, 49 °C, and 51 °C) as described in Materials and Methods. Samples were then analyzed by Western blot using the indicated Abs. (C) Expression of isotope-tagged EGFR. CHO cells were transfected with MYC- or FLAG-tagged EGFR, followed by immunofluorescent staining and photography. (Magnification: 40×.)

MLN4924 Does Not Bind to EGFR Directly but Induces EGFR Dimerization.

To elucidate the possible mechanisms by which MLN4924 activated the EGFR signaling pathway, we first determined whether MLN4924 could directly bind to EGFR using the cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) (38), a screening assay designed to monitor drug-target engagement based on the assumption that drug binding could cause a shift in the thermostability of the target. The results showed that MLN4924 did not significantly change the EGFR thermostability (Fig. S5B), indicating that MLN4924 might not directly bind to EGFR for its action, although we cannot exclude the possibility of a weak binding.

Given that EGFR stabilization and activation can be achieved by its dimerization (39), we next determined whether MLN4924 would trigger EGFR dimerization. Cells were treated with 0.1 µM MLN4924 for 1 h or 24 h or EGF (10 ng/mL served as a positive control), as well as in combination, followed by cross-linking with disuccinimidyl substrate (DSS). The results showed that in both H1299 and HCT116 cells, MLN4924 indeed induced a time-dependent increase in the formation of dimerized EGFR, with combination reaching the highest level of dimerization (Fig. 5B).

Finally, we used a proximity ligase assay (PLA), also known as proximity ligation immunofluorescence (PLI) (40), as an independent measure for in situ detection of EGFR dimerization in intact cells. The assay is based upon induced close proximity upon dimerization of two fluorescent-labeled EGFR molecules to trigger unique fluorescent signals (40). We first confirmed that Myc- or FLAG-tagged EGFR constructs were expressed properly at the individual level (Fig. S5C) and then treated cotransfected cells with MLN4924 or EGF alone or in combination. Indeed, MLN4924 or EGF triggered PLA/PLI signals significantly compared with the vehicle control, with the highest signals seen in combination (Fig. 5C). Taken together, we have used two independent methods to demonstrate that MLN4924 indeed triggers EGFR dimerization to activate the EGFR signaling pathway.

TS-Stimulating Effect of MLN4924 Requires Activation of EGFR Signaling Pathways.

We next determined, via loss-of-function (kinase inhibitors) and gain-of-function (ectopic EGFR expression) approaches, whether activation of EGFR signaling pathways was causally related to MLN4924-induced TS formation. To reproducibly and quantitatively assess the effect of inhibitors alone (toxicity) or in combination with MLN4924 (rescue), we defined two SSS-based parameters: %SSSi and %SSSr. As explained by the equation (Table S1), the higher the %SSSi value, the greater the inhibition of an inhibitor alone on basal level of TS formation, whereas the higher the %SSSr value, the more the blockage of MLN4924-induced TS formation by an inhibitor. Because a high value of %SSSi (which might indicate a high degree of cytotoxicity) of a given inhibitor might interfere with the assessment of its rescue effect on MLN4924, we defined arbitrarily that %SSSr would be more meaningful if %SSSi was less than 0.5 (50% or the dosage of the inhibitor was lower than its IC50 of TS inhibition effect), despite the fact that we did see a dissociation between the two parameters (Table S1).

Table S1.

Pathway inhibitors for blockage of MLN4924-induced TS formation

| Drug | Con (μM) | %SSSi | %SSSr | Rescue? | |||||

| CI | 2 | 10,747 | 21,362 | 5,758 | 7,762 | 46.40 | 64.80 | Yes | Partial |

| ERL | 3 | 10,747 | 21,362 | 7,677 | 13,463 | 28.60 | 23.70 | Yes | Partial |

| 6 | 12,577 | 56,355 | 4,938 | 7,471 | 60.70 | 85.30 | Yes | Partial | |

| LY | 10 | 64,886 | 140,261 | 61,118 | 78,002 | 5.80 | 76.20 | Yes | Partial |

| Rapa | 0.1 | 64,886 | 140,261 | 46,140 | 59,199 | 28.90 | 75.60 | Yes | Partial |

| MK | 0.25 | 27,207 | 65,045 | 9,148 | 23,512 | 66.40 | −12.90 | No | N/A |

| 0.5 | 27,207 | 65,045 | 6,984 | 18,608 | 74.30 | −19.70 | No | N/A | |

| PFS | 1 | 13,675 | 48,277 | 11,174 | 48,105 | 18.30 | −30.60 | No | N/A |

| 3 | 13,675 | 48,277 | 9,087 | 42,546 | 33.60 | −45.50 | No | N/A | |

| si-AKT | 0.1 | 27,207 | 65,045 | 6,178 | 11,960 | 77.30 | 32.7 | Yes | Partial |

| U | 10 | 64,886 | 140,261 | 49,498 | 75,053 | 23.70 | 55.60 | Yes | Partial |

Equations: and . CI, CI1033; con, concentration; ERL, Erlotinib; LY, LY294002; MK, MK2206; PD, PD98059; PFS, Perifosine; Rapa, Rapamycin; si-AKT, siRNA targeting AKT; U, U0126.

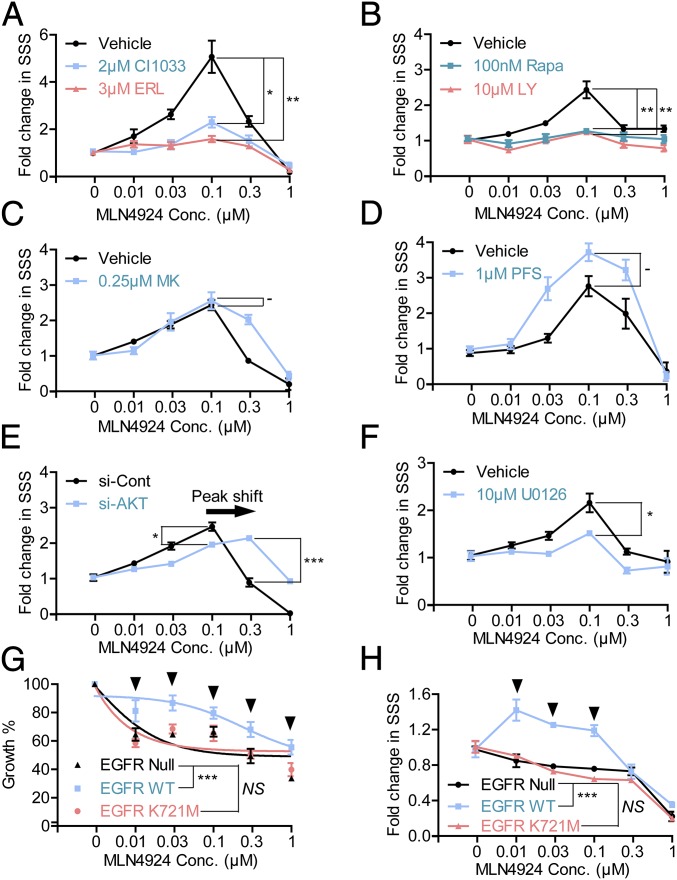

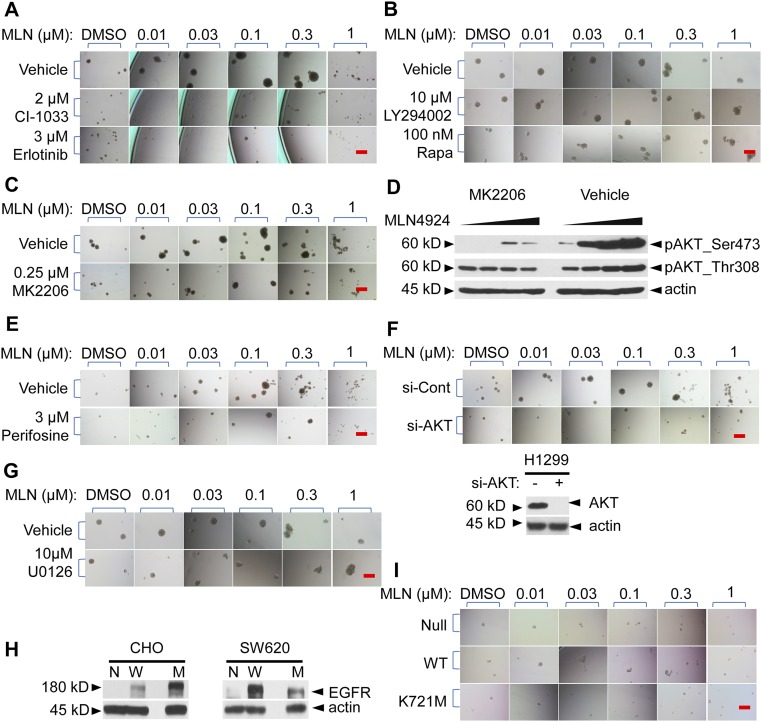

Targeting EGFR.

RTKs require their kinase activity to transduce extracellular signals from ligand binding to their intracellular downstream targets. We, therefore, used CI-1033, an irreversible inhibitor (41), and Erlotinib, a reversible inhibitor (42), of EGFR tyrosine kinase and found that both inhibitors were able to partially block the stimulatory effect of MLN4924 at the concentrations less than the IC50 dosage (Fig. 6A, and Fig. S6A, P = 0.0074 and P = 0.0181, respectively, and Table S1). A higher dose of Erlotinib conferred a better rescue but with a higher %SSSi value (Table S1).

Fig. 6.

Blockage of TS-stimulating effect of MLN4924 via pharmacological or genetic approaches. (A) Targeting EGFR. H1299 cells were plated for TS formation assay and treated with the indicated concentration of MLN4924 in the presence or absence of CI-1033 (2 μM) or Erlotinib (ERL, 3 μM). Fold-change in SSSs was calculated by arbitrarily setting the SSS of vehicle-treated cells from each group as 1 and was plotted against dose. (B–D) Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 axis. H1299 cells were plated for TS formation assay and treated with indicated concentrations of MLN4924 in the presence or absence of Rapamycin (Rapa, 100 nM), LY294002 (LY, 10 μM), MK2206 (MK, 0.25 μM), or Perifosine (PFS, 1 μM). Results were presented as described in A. (E) Targeting total AKT via siRNA. H1299 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA (si-Cont) or 20 nM siRNA targeting AKT (si-AKT), followed by TS formation assay in the presence of indicated concentrations of MLN4924 for 4 d. Results were presented as described in A. (F) Targeting MAPK. H1299 cells were subjected to TS formation assay with MLN4924 stimulation in the presence or absence of MAPK inhibitor U0126 (10 µM). Results were presented as described in A. (G and H) Effect of ectopic expression of EGFR. EGFR-null CHO cells or colon cancer SW620 cells were transfected with wild-type EGFR and an EGFR dead mutant K721M. CHO cells were subjected to ATPLite proliferation assay after treatment with indicated concentrations of MLN4924 for 72 h (G), whereas SW620 cells were subjected to TS formation assay after treatment with indicated concentrations of MLN4924 for 4 d (H). Results were presented as described in A.

Fig. S6.

Blockage of TS-stimulating effect of MLN4924 via pharmacological or genetic approaches. (A and B) Targeting EGFR, PI3K, or mTORC1. H1299 cells were plated for TS formation assay treated with indicated concentrations of MLN4924 in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of EGFR inhibitor CI-1033 or Erlotinib (A) or LY294002 or Rapamycin (B). Shown are representative photos of spheres taken at day 8 (for CI-1033 or Erlotinib) or at day 4 (for LY294002 or Rapamycin). (C–E) Targeting AKT. H1299 cells were plated and treated with indicated concentrations of MLN4924 in the presence or absence of indicated concentrations of MK2206 for TS formation assay (C) or Western blot (D) or Perifosine for TS formation assay (E). Shown are representative photos of spheres taken at day 8. (F) Target total AKT via siRNA. H1299 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA (si-Cont) or 100 nM siRNA targeting AKT (si-AKT), followed by Western blot or TS formation assay in the presence of the indicated concentrations of MLN4924 for 4 d. Shown are representative photos of spheres taken at day 4. (G) Targeting MAPK. H1299 cells were plated for TS formation assay treated with the indicated concentrations of MLN4924 in the presence or absence of 10 μM U0126. Shown are representative photos of spheres taken at day 8. (H) Overexpressing wild-type EGFR (WT) and kinase dead mutant EGFR (K721M) in EGFR-null CHO and SW620 cells. CHO and SW620 cells were transfected with EGFR WT and EGFR K721M constructs. Expression of EGFR WT and mutant were confirmed by Western blot. (I) Effect of ectopic expression of EGFR. EGFR-null SW620 cells were transfected with wild-type EGFR and an EGFR dead mutant K721M and subsequently subjected to TS formation assay treated with indicated concentrations of MLN4924 for 4 d. Shown are representative photos of spheres taken at day 4. (Scale bars, 500 μm.)

Targeting PI3K/AKT/mTORC1.

We then used several small molecule inhibitors targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR. LY294002, a classic inhibitor of PI3K (43), significantly blocked the TS-stimulating effect of MLN4924 with a 76% rescue effect (Fig. 6A, Fig. S6B, and Table S1) (P = 0.0083). Likewise, rapamycin, an mTORC1 inhibitor, also showed a 76% rescue effect (Fig. 6A, Fig. S6B, and Table S1) (P = 0.0086). Interestingly, MK2206, a highly selective allosteric AKT inhibitor, which prevented recruitment of AKT to the plasma membrane for activation via binding to the pleckstrin-homology domain to cause conformational change (44), had no rescue effect (Fig. 6C and Fig. S6C), even when used at a high toxicity dose (Table S1) with potent activity in blocking phosphorylation of AKTSer473 (Fig. S6D). Moreover, another AKT inhibitor, Perifosine, which blocks the recruitment of AKT to the plasma membrane for activation by PDK1, thus blocking AKTSer473 phosphorylation (45), had no rescue effect either (Fig. 6D, Fig. S6E, and Table S1). On the other hand, however, AKT knockdown by siRNA caused a right shift of the MLN4924-TS stimulation curve (Fig. 6E and Fig. S6F) (P = 0.0204 at 0.1 μM and P = 0.0006 at 0.3 μM) with a partial rescue activity (Table S1). The results suggest that AKT itself, but not its Ser473 phosphorylation or plasma membrane recruitment, is required to mediate MLN4924 action. Taken together, it appeared that the PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 axis, particularly activation of PI3K and mTORC1 kinases, plays a major role in the MLN4924 TS-stimulating effect.

Targeting RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK.

We also tested the potential involvement of the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway using U0126, a selective noncompetitive inhibitor of MEK1/2 (46). U0126 partially blocked the stimulatory effect of MLN4924 on TS formation with a 55.6% rescue effect (Fig. 6F, Fig. S6G, and Table S1) (P = 0.0357), supporting the role of MAPK signaling as a major downstream pathway of EGFR.

Activating EGFR.

To further validate EGFR involvement, we used a gain-of-function approach by ectopic expression of wild-type EGFR in comparison with a kinase-dead mutant control in EGFR-null Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells and SW620 cells (human colorectal cancer cells). Because CHO cells do not form TSs whereas SW620 cells can, we, therefore, used ATPLite proliferation assay and TS formation assay to assess the effect of MLN4924, respectively. Indeed, cells expressing wild-type EGFR (Fig. S6H) were more resistant to MLN4924-induced growth suppression in a monolayer culture (Fig. 6G) (P < 0.0001) and were able to form significantly more TSs upon MLN4924 stimulation (Fig. 6H and Fig. S6I) (P < 0.0001). On the other hand, cells expressing K721M mutant, a point mutation in the ATP pocket of EGFR, which completely inactivates the kinase activity of EGFR (47), had no such effects (Fig. 6 G and H). Taken together, these results suggested that the kinase activity of EGFR was required for the growth-stimulating effect of MLN4924.

MLN4924 Promoted EGF-Induced Skin Wound Healing in the Mouse Model and in Vitro Migration of Immortalized Epithelial Cells.

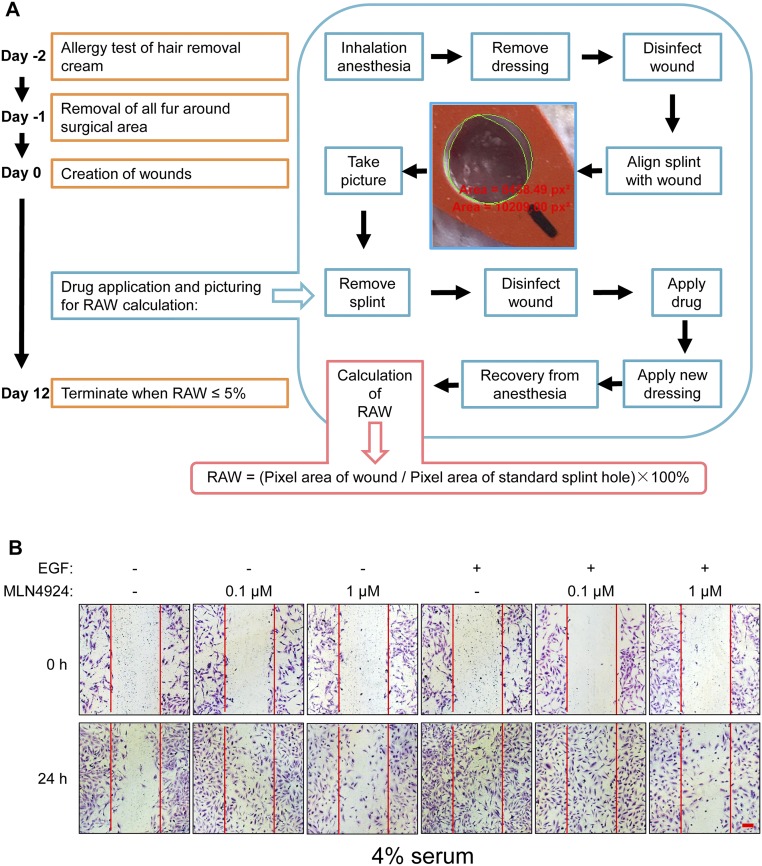

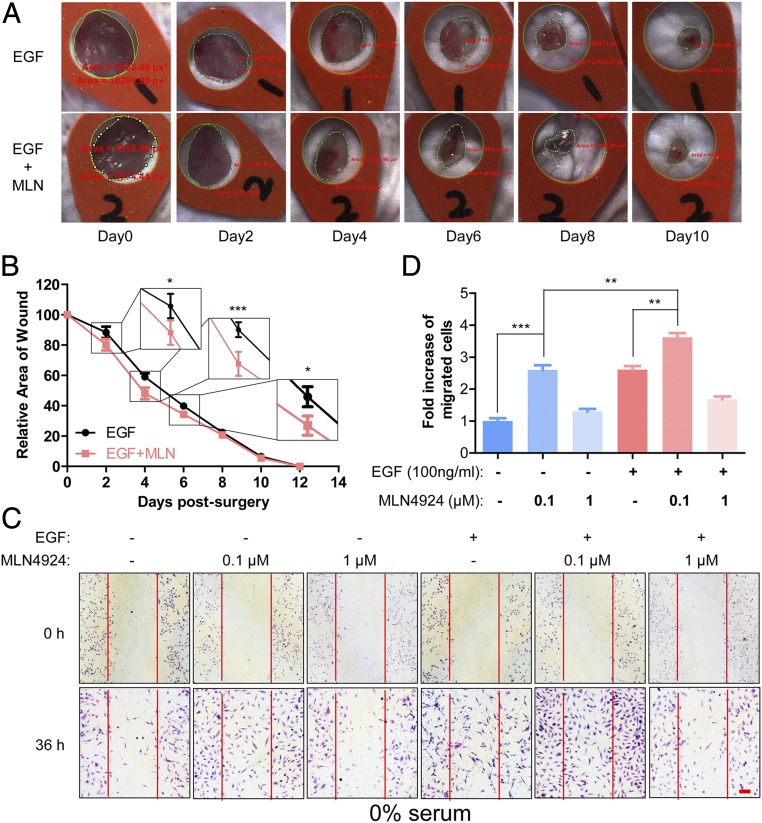

Finally, we determined the potential application of stem cell-stimulating activity of MLN4924 in vivo. Given that EGF has been shown to accelerate the healing process of various types of skin wounds, including massive burns (48), skin loss resulting from trauma or medical procedures, and diabetic ulcers (49) and given that MLN4924 was capable of stimulating proliferation of stem cells by activating EGFR signaling pathways, we used C57BL/6 mice and tested whether MLN4924 could work with EGF synergistically in promoting skin wound healing with the procedures outlined (Fig. S7A). Because wound contraction after creation of full-thickness skin wound in mice could be problematic for precise assessment of the healing process (50), we used transparent adhesive dermal dressing (3M, Tegaderm) to seal the wound for preventing wound contraction, better observation of the healing process, and prolonged local application of the drug in liquid form. After creating bilateral full-thickness skin wounds as previously described (51), we treated mirroring wounds created on the left and right flank region with either EGF plus vehicle or EGF plus 0.1 μM MLN4924, respectively (n = 11). Dressings were changed, fresh EGF/MLN4924 was applied, and relative areas of wound (RAWs) values were measured and calculated every other day (Fig. 7A). The results showed that MLN4924 significantly accelerated wounding healing during the early phase (before 6 d), as evidenced by smaller RAW values (P values at day 2, 4, and 6 were 0.0230, 0.0005, and 0.0349, respectively), although it did not seem to affect the total time period required for complete wound closure (12 d) (Fig. 7B).

Fig. S7.

Protocol for skin wound healing assay in mouse. (A) Flowchart of protocol for mouse skin wound healing assay. See Materials and Methods for details. (B) MLN4924 at low concentration stimulates migration of BEAS-2B cells. In confluent BEAS-2B cells cultured in coverslips, a linear wound was generated in the monolayer with sterile 200-μL pipette tips. Cells were cultured in 4% (vol/vol) serum and treated with MLN4924 or EGF alone or in combination for 24 h, followed by staining and photographing. (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

Fig. 7.

MLN4924 promotes EGF-induced skin wound healing and cell migration. (A) Surgical creation of full-thickness skin wound and measurement/calculation of RAW. Words in red are software-measured pixel areas of actual wounds and the standard hole on the red silicon film. See SI Materials and Methods for details. (B) MLN4924 promoted EGF-induced healing of skin wound. RAWs of wounds treated with EGF plus vehicle (EGF) or EGF plus MLN4924 (EGF+MLN) were plotted against time. Shown are mean ± SEM (n = 11). (C and D) MLN4924 promoted migration of BEAS2B cells in an in vitro scratch assay. BEAS2B cells with a linear wound made by 200-μL pipette tips were then treated with various treatments as indicated while grown in 0% serum for 24 h. Cells were fixed, stained with 1% Toluidine and 1% Borax for 20 min, and photographed (C). Number of cells migrating into scratched space was counted. The data were expressed as fold increase of migrated cells compared with vehicle control. Shown are mean ± SEM from three independent experiments (D). (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

We further performed the in vitro scratch assay (52) using BEAS2B cells (a normal epithelial line derived from normal bronchial epithelium and immortalized by infection with a replication-defective SV40/adenovirus 12) to determine the stimulating effect of MLN4924 on cell migration. We found that migration of BEAS2B cells was promoted by 0.1 µM MLN4924, as well as EGF, but inhibited by 1 µM MLN4924 regardless of EGF. A combination of MLN4924 and EGF induced maximal migration when cells were cultured in 0% (Fig. 7 C and D) or 4% (vol/vol) serum (Fig. S7B). Collectively, our data showed that MLN4924 indeed promotes cell migration, with a potential to accelerate wound healing.

Discussion

MLN4924 (pevonedistat) is a potent inhibitor of NAE, thus inactivating the entire process of protein neddylation (7). MLN4924 showed anticancer activity in various preclinical settings by inducing apoptosis, autophagy, and senescence, as well as overcoming drug resistance and sensitizing chemoradiation (for a review, see refs. 11 and 53). MLN4924 has been evaluated as a single agent in four phase 1 trials in solid tumors and hematological malignancies, and is currently evaluated in phase 1b trials in combination with conventional chemotherapies for solid tumors and AML (11, 54).

Here, we made a novel and unexpected observation that MLN4924, at low nanomolar concentrations, has significant stimulating activity in promoting cell proliferation and stem cell self-renewal under both in vitro culture and in vivo mice settings, as evidenced by following observations made in (i) monolayer culture of cancer cells and mESCs, (ii) sphere formation of both cancer cells and mouse ESCs, (iii) in vivo tumorigenesis of both cancer cells and mESCs, and (iv) the early phase of wound healing in mouse skin and in vitro migration of immortalized epithelial cells.

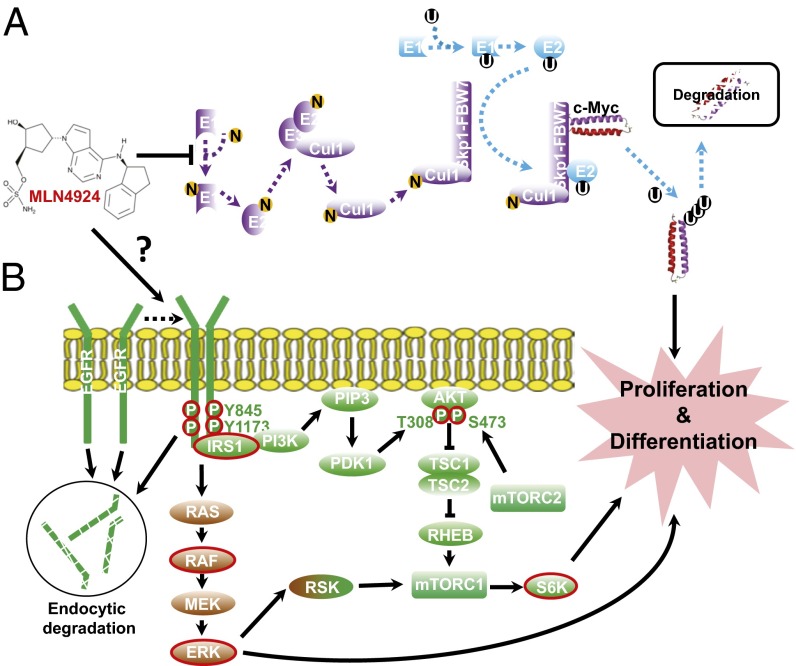

Through our mechanistic studies, we propose that this stimulatory effect of MLN4924 could likely be attributable to (i) blockage of degradation of c-MYC, a growth-promoting oncoprotein, and stemness-stimulating factor (Fig. 8A) and (ii) activation of EGFR signaling by inducing dimerization of EGFR (Fig. 8B). Based on the observations that (i) MLN4924 only caused a minor accumulation of total EGFR, (ii) MLN4924 enhanced and prolonged EGF-induced activation of EGFR signaling pathways, and (iii) prolonged treatment with MLN4924 also activated the EGFR signaling pathway in the absence of EGF, we propose a possible model to explain how MLN4924 would activate EGFR signaling alone or in combination with EGF (Fig. 8). First, it is well-established that upon addition of EGF to serum-starved cells (in the absence of MLN4924), EGF instantly promotes EGFR dimerization and activation, followed by rapid endocytic degradation of EGFR (55). Therefore, the activation of EGFR and other downstream targets reaches a peak within minutes, followed by gradual deactivation via endocytic degradation, returning to the basal level at 2 h (Fig. 4A). Second, upon prolonged exposure of serum-starved cells to a low dose of MLN4924 (in the absence of EGF), a ligand-independent EGFR dimerization occurs (Fig. 5 B and C) through a currently unknown mechanism, leading to accumulation EGFR dimers on the cellular membrane, a known process to cause the activation of EGFR and its downstream signals (39). Third, in the presence of both EGF and MLN4924, EGFR signaling is again instantly activated by ligand binding with the endocytic degradation of EGFR moderately inhibited possibly by MLN4924-induced EGFR dimerization, leading to sustained EGFR signaling. Interestingly, in our experimental conditions, this process appears to be independent of c-Cbl (Fig. 5A and Fig. S5A), an E3 ligase reported to induce EGFR ubiquitylation and neddylation for subsequent endocytosis (36), and VHL (Fig. S4 C and D), but with HIF1α playing a negative role (Fig. 4 C and D).

Fig. 8.

Mechanism of MLN4924 action. Proposed mechanisms of how MLN4924 promotes cell proliferation. (A) Inactivation of CRL1. MLN4924 causes accumulation of oncoprotein c-MYC, which promotes proliferation of both normal and cancer-initiating cells. (B) Induction of EGFR dimerization. MLN4924 induces EGFR dimerization and stabilizes EGFR on the cellular membrane to activate multiple downstream pathways for proliferation.

This working model also explains our interesting observation that MLN4924 is much more active than EGF in stimulating TS formation in our system (Fig. 1E). Given that EGF causes a rapid activation of EGFR, which triggers recycling of activated EGFR for endocytosis, the EGF effect is doomed to be acute and transient. However, in the case of MLN4924, the effect is rather long term; MLN4924 appears to break the dynamic balance of EGFR recycling by inducing dimerization, causing persistent transduction of hyperactivated EGFR signaling to stimulate sphere formation, which is a long-period process for up to 16 d. The involvement of activation of EGFR and its downstream pathways in MLN4924-induced TS stimulation was further confirmed by our rescue experiments with both a loss-of-function approach, which confirmed the involvement of EGFR and two of its main downstream pathways—PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 and MAPK (Table S1)—and a gain-of-function approach, which confirmed the necessity of the kinase activity of EGFR.

However, another interesting observation we made here is that this TS-stimulating effect was only observed within a certain range of MLN4924 concentrations, mostly centering at 0.1 μM, which is sufficient to inhibit cullin-1 neddylation (Fig. 4B, Fig. 5A, and Fig. S5A). The underlying mechanism of the opposing effects of MLN4924 in growth stimulation (at low concentration) versus growth suppression (at high concentration) is not clear at the present time. It is conceivable that MLN4924 facilitates chronic EGFR activation by inducing dimerization, particularly under serum-free condition, whereas higher concentration exhibited predominantly antiproliferation properties by causing accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins via blockage of their proteasomal degradation due to inactivation of CRL E3 ligases (56). It is worth noting that MLN4924 concentrations of 0.1 μM are lower than peak plasma concentrations of ∼1.5 μM reached at the maximum tolerated dose of 59 mg/m2 in a phase 1 trial of MLN4924 in AML and MDS (12). Although the half-life of MLN4924 in mice was not measured directly, Soucy et al. (7) did show that the levels of NEDD8-cullin conjugate were reduced to 20% of the original within the first 2 h upon a single subcutaneous dose of MLN4924, and 50% levels of reduction were maintained for up to 24 h. On the other hand, the results of pK analysis for MLN4924 in patients were separately presented as abstracts by J. J. Shah during the 51st American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition (57) and J. S. Kauh during the 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting (58), which indicated a half-life of 4–9 h and 5–15 h via intravenous infusion, respectively. Generally, the drug administered via local injection (as for the xenograft assays conducted in our study) could have a prolonged and concentrated effect in the injected areas compared with IV infusion. Nevertheless, our observation that MLN4924 possesses the proliferation- and sphere-stimulating activity at nanomolar concentration raises concern for its application in the treatment of human cancer (especially solid tumors), while suggesting a potential future application of MLN4924 in stem cell therapy and tissue regeneration.

The process of wound healing can be divided into three phases: (i) hemostasis and inflammation, (ii) proliferation/tissue formation, and (iii) tissue remodeling (59). It is currently acknowledged that multiple types of stem cells reside within the dermis and epidermis, including stem cells in the interfollicular epidermis (IFE), and hair follicular stem cells and melanocyte stem cells in the hair follicle bulge (60). Cells from both hair follicles and IFE migrate into the site of damage following full-thickness wound creation, contributing to wound repair (61), whereas only IFE plays a major role in wound reepithelialization (62). Here we showed that in both in vivo and in vitro settings MLN4924 accelerated the EGF-induced skin wound healing process as well as epithelial cell migration. It is unclear why this early stage healing acceleration in our mouse model did not eventually translate to an overall shortening of the healing process. We speculate that MLN4924 may be only effective in the first two stages of wound healing by inhibiting inflammation (63) and promoting proliferation (this study) but not the last stage of tissue remodeling, which is a subject of future investigation. Nevertheless, the healing-accelerating and migration-promoting effects may benefit patients, particularly those with chronic skin wounds such as diabetic ulcers and large area of skin loss resulting from trauma or burns.

In summary, we made a surprising observation that blockage of the neddylation modification with low concentrations of MLN4924 significantly stimulates proliferation and sphere formation in human cancer cells and mESCs both in an in vitro cell culture setting and in vivo animal studies with a mechanism involving accumulation of c-Myc and chronic activation of EGFR via dimerization (Fig. 8). Our study might pave the foundation for future development of MLN4924 as a novel class of agents for stem cell therapy and tissue regeneration.

Materials and Methods

Study Approval.

All procedures and experiments were approved by the University of Michigan Committee for the Use and Care of Animals. Animal care was provided in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (64). The human cancer cell lines used in this study were purchased from ATCC and cultured according to the instructions provided.

Sphere Formation Assay.

A single cancer cell suspension was made by enzymatic/mechanic disassociation, followed by filtration through a 40-μM cell strainer. Cells were washed in 1× DPBS (Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline) twice, counted, and plated at clonal density in TS conditioned medium, consisting of serum-free DMEM F12 supplemented with 0.4% BSA, 5 mM Hepes, penicillin/streptomycin, 20 ng/mL EGF (Life Technologies), and 10 ng/mL bFGF (Sigma), unless otherwise indicated, in 24-well ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates (Corning). SSSs are documented as previously described (16) every 4 d for up to 16 d.

EGFR Dimerization.

H1299 and HCT116 cells were serum-starved for 24 h and then treated with 0.1 µM MLN4924 for 1 h or 24 h with the addition of 150 µM DSS, a cross-linking agent, in the last 30 min of treatment. For positive control, 30 ng/mL of EGF was added in combination with DSS and incubated for 30 min. Cells were scraped into RIPA buffer with protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics). Cell lysates were then sonicated and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The soluble protein fraction was collected and subjected to immunoblotting to detect EGFR dimerization.

In Situ PLA.

A previous protocol (40) was followed with minor modification. Briefly, EGFR-null CHO cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing EGFR-FLAG and EGFR-MYC. Twenty-four hours later, cells were seeded on coverslips and treated with 0.1 μM MLN4924 for 1 h or 24 h, respectively. For the positive control, 100 ng/mL of EGF was added and incubated for 30 min. The combination of MLN4924 and EGF was included. Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with mouse anti-MYC (Sigma-Aldrich) and rabbit anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich) primary antibodies and then stained using Duolink In Situ-Fluorescence kit (Sigma-Aldrich), according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. PLA images were collected and quantified by Duolink ImageTool.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using paired or unpaired Student’s t test or two-way ANOVA. Data were represented as mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments or otherwise indicated. Not significant P > 0.05, *0.01 < P < 0.05, **0.005 < P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005.

SI Materials and Methods

Cell Lines.

Lung cancer cell lines (H1299, H125), breast cancer cell lines (MCF7, SUM159), colorectal cancer cell lines (HCT116), prostate cancer cell lines (PC3), neuroblastoma cells (U87), CHO, and SW620 (colorectal cancer) were obtained from ATCC. H1299-ODC-ZsGreen cells were a gift from M. You, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee (23). Isogenic HCT116 FBW7+/+ and FBW7−/− cells were obtained from B. Vogelstein, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. mESCs were derived as previously described (65).

Compounds.

MLN4924 was provided by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. CI-1033 and Erlotinib were purchased from Selleck Chemicals. LY294002 and Rapamycin were purchased from Sigma. MK2206 (Selleck Chemicals) and Perifosine (Sigma) were kindly provided by Alnawaz Rehemtulla, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Animals.

BALB/c background SCID NCr (nude) mice and C57BL/6 background mice were purchased from Charles River (www.criver.com).

Antibodies and siRNAs.

The following antibodies were used: c-MYC (rabbit polyclonal; Epitomics), Nrf2 (rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz), pEGFR Tyr845 (mouse monoclonal; Enzo Life Sciences), pEGFR Tyr1173 (rabbit polyclonal; Cell Signaling), EGFR (rabbit polyclonal; Cell Signaling), pIRS1 (rabbit polyclonal; Cell Signaling), pAKT Ser473 (rabbit polyclonal; Cell Signaling), pAKT Thr308 (rabbit polyclonal; Cell Signaling), p-c-Raf (rabbit polyclonal; Cell Signaling), pERK (rabbit polyclonal; Cell Signaling), p-p70 S6K (rabbit polyclonal; Cell Signaling), c-Cbl (rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz), AKT (mouse monoclonal; Cell Signaling), Cul1 (rabbit polyclonal; Abcam), Nedd8-Cullin (rabbit polyclonal; Abcam), CDT1 (rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz), KLF4 (rabbit polyclonal; Cell Signaling), OCT4 (rabbit monoclonal; Cell Signaling), SOX2 (rabbit monoclonal; Cell Signaling), HIF1α (rabbit polyclonal; Santa Cruz), and actin (mouse monoclonal; Santa Cruz). SiRNA targeting c-MYC, AKT, and c-Cbl were purchased from Santa Cruz.

Expression Constructs.

To prepare FLAG and MYC epitope-tagged EGFR-expressing vectors, we made the following two oligonucleotides: Oligoes FLAG sense/antisense (FLAGsense-01, 5′-GGGGTACCCGATTACAAGGATGACGACGATAAGTGATGAAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCAAAAGGAAAA-3′; and FLAG antisense-01, 5′-TTTTCCTTTTGCGGCCGCTTTTTTCCTTCATCACTTATCGTCGTCATCCTTGTAATCGGGTACCCC-3′) and MYC sense/antisense (MYC sense-01, 5′-GGGGTACCCGAGCAGAAACTCATCTCTGAAGAGGATCTGTGATGAAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCAAAAGGAAAA-3′, and MYC antisense-01, 5-TTTTCCTTTTGCGGCCGCTTTTTTCCTTCATCACAGATCCTCTTCAGAGATGAGTTTCTGCTCGGGTACCCC-3′). The oligonucleotides were annealed and digested with KpnI and NotI and then cloned into N1-EGFR (lacking stop code) to replace YFP fragment to generate plasmids expressing N1-EGFR-FLAG and N1-EGFR-MYC.

Immunohistochemistry for Paraffin Sections.

TSs and explanted xenografts were processed as follows: For TSs, 3D structures were collected in a 100-μm cell strainer and then gently washed into 15-mL V-bottomed Falcon tubes using PBS. TSs and xenografts were then washed twice in PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4 °C overnight after removing the supernatant PBS by gentle aspiration. After PFA fixation, PFA was removed carefully by pipette and washed twice in PBS. For TSs, a minimum amount of liquid HistoGel (Thermo Scientific) was used to resuspend the pellet gently, which was then transferred into cryomolds for solidification (Sakura Finetek). Xenografts were transferred into cyromolds. Cryomold blocks were then dehydrated in 30% ethanol (30 min), 50% ethanol (30 min), and 70% ethanol (overnight) before embedding in paraffin. Sections of 5 μm obtained using microtome (Leica RM2235) were deparaffinized and rehydrated in water before immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed. Sections were processed by standard H&E staining protocol or stained with indicated antibodies and developed by ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) following the manufacturer’s protocol. IHC slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted for microscopy (Olympus IX71) and picturing (Nikon, DS-Fi1).

EB Formation Assay.

mESCs were maintained as feeder-free monolayer cultures in the presence of 1,000 U/mL LIF (Life Technologies). A single-cell suspension was made as described above. Cells were then counted and plated at clonal density in DMEM supplemented with 15% (vol/vol) FBS, unless otherwise indicated, in 24-well ULA plates. The SSS (16) was recorded every 4 d for up to 16 d.

SiRNA-Based Knockdown.

Knockdown of c-MYC, HIF1α, AKT, or c-Cbl was achieved by Lipofectamine2000 (Life Technologies)-mediated siRNA transfection, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Santa Cruz). A Western blot showing knockdown effect was performed 48 h after transfection. All phenotypic assays were started 72 h after transfection.

Immunofluorescence Staining.

A single-cell suspension was prepared as described above. Cells were then stained with Alexa Fluor 700-conjugated anti-CD44 antibodies (Affymetrix eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, before assessment by FACS (Beckman Coulter).

AP Staining.

mESCs were plated for attached growth with or without feeder cells. Following MLN4924 treatment, AP staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Sigma-Aldrich).

ATPLite for Cell Proliferation.

Cells were plated in a 96-well plate for attached growth before treatment with the indicated drugs for 72 h, or as otherwise indicated. One-step ATPLite assay (PerkinElmer) was then performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunohistochemistry.

Paraffin sections of H1299 TS were stained with anti-Ki67 antibody (BD Pharmingen) and developed by ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Paraffin sections of explanted xenograft from mESCs were processed through a standard H&E staining protocol.

CETSA.

CETSAs were performed as previously described (38). In general, H1299 cells were serum-starved for 24 h, before being treated with a high dose of MLN4924 (10 μM) for a short time (1 h). Samples were then subjected to gradient thermo treatment using PCR cycler (Eppendorf) before being analyzed by Western blot using indicated antibodies.

Xenograft Assay.

Matrigel mixed single-cell suspension were mixed with MLN4924 (to a final concentration of 0.1 μM) or vehicle, before subcutaneous injection in the right or left flank region, respectively, of BALB/c background SCID NCr immunodeficient mice. Mouse body weight and the size of tumor mass (; W, width, the shortest axis of mass; L, length, the longest axis of mass) were recorded every 3 d. Mice were euthanized when tumor volume exceeded 1,000 mm2 and tumor weights were recorded.

Skin Wound Healing Assay in Mouse.

Two identical full-thickness skin wounds on the left and right flank region of pure C57BL/6 background mice were created using biopsy punch as previously described (51). The 10 μL of 0.67 μg/mL EGF in 1× PBS or 10 μL of 0.67 μg/mL EGF with 0.1 μM MLN4924 in 1× PBS were directly pipetted onto the left or right wound, respectively, in an aseptic manner. Sterilized transparent adhesive dressings (3M; Tegaderm) were then applied to prevent wound contraction. Every other day, dressings were changed and RAWs of all wounds were measured and calculated as follows. Briefly, we developed a previously unreported method/parameter for precise measurement of the size of a skin wound, designated as RAW. A silicon film with a standard circular hole (for example, ⌀6 mm) was placed above the wound, which was made using a smaller gauge skin punch (for example, ⌀5 mm), to ensure that (i) the entire wound was enclosed within the standard circular hole; (ii) the silicon film was attached tightly with the skin around the wound, so that the standard circular hole and the wound were on the same plane; and (iii) the tension of the skin around the wound was minimal so that the wound was in its natural shape. A photograph completely covering the wound and the standard circular hole was then taken. Using imaging software with measuring functions (e.g., NIS Element BR; Nikon), we measured the “pixel area” of the wound and the standard circular hole by “polygon” and “5-point ellipse,” respectively. RAW was then calculated as (see Fig. S7A for the detailed procedure). We used the same silicon film or other silicon films (silicon film can be labeled to identify different wounds after taking the picture) with the same sized standard circular hole to measure other wounds and calculate their respective RAW in batches. Because the wound and the standard silicon hole were placed on the same plane, neither the distance between the camera and the wound nor the angle from which the picture was taken would affect the value of RAW. Because the same standard circular hole was used as reference, RAWs of all wounds were comparable. Computer-based measurement resulted in a highly precise RAW value. The experiment was terminated when all RAWs ≤ 5%.

Scratch Assay.