Significance

Mutations affecting two unrelated genes, retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) and tubulin tyrosine ligase like 5 (TTLL5), lead to photoreceptor degeneration and blindness in humans. We find that RPGR function in photoreceptor cilia requires glutamylation by TTLL5. Glutamylation is a poorly understood posttranslational modification that consists of the addition of glutamates to target proteins. Moreover, we find that mice lacking RPGR or TTLL5 exhibit similar phenotypes characterized by photoreceptor degeneration and opsin mislocalization. Our work identifies a novel essential regulator of RPGR and demonstrates that disease-causing mutations in these two genes share a common pathogenic pathway in humans.

Keywords: cilia, polyglutamylation, retinitis pigmentosa, tubulin tyrosine ligase-like, RPGR

Abstract

Mutations in the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) gene are a major cause of retinitis pigmentosa, a blinding retinal disease resulting from photoreceptor degeneration. A photoreceptor specific ORF15 variant of RPGR (RPGRORF15), carrying multiple Glu-Gly tandem repeats and a C-terminal basic domain of unknown function, localizes to the connecting cilium where it is thought to regulate cargo trafficking. Here we show that tubulin tyrosine ligase like-5 (TTLL5) glutamylates RPGRORF15 in its Glu-Gly–rich repetitive region containing motifs homologous to the α-tubulin C-terminal tail. The RPGRORF15 C-terminal basic domain binds to the noncatalytic cofactor interaction domain unique to TTLL5 among TTLL family glutamylases and targets TTLL5 to glutamylate RPGR. Only TTLL5 and not other TTLL family glutamylases interacts with RPGRORF15 when expressed transiently in cells. Consistent with this, a Ttll5 mutant mouse displays a complete loss of RPGR glutamylation without marked changes in tubulin glutamylation levels. The Ttll5 mutant mouse develops slow photoreceptor degeneration with early mislocalization of cone opsins, features resembling those of Rpgr-null mice. Moreover TTLL5 disease mutants that cause human retinal dystrophy show impaired glutamylation of RPGRORF15. Thus, RPGRORF15 is a novel glutamylation substrate, and this posttranslational modification is critical for its function in photoreceptors. Our study uncovers the pathogenic mechanism whereby absence of RPGRORF15 glutamylation leads to retinal pathology in patients with TTLL5 gene mutations and connects these two genes into a common disease pathway.

Inherited forms of retinal dystrophies, clinically known as retinitis pigmentosa (RP), are degenerative conditions affecting photoreceptor cells and are an important cause of blindness (1). Autosomal dominant, recessive, and X-linked forms of the disease are well documented. The disease etiology is highly heterogeneous, with mutations in more than 200 genes with diverse functions shown to underlie various forms of retinal dystrophy (https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/sum-dis.htm). Among these, mutations in the gene encoding retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) are a frequent cause, accounting for more than 70% of X-linked RP and up to 20% of all RP cases (2–5). The disease associated with RPGR is severe and impacts central vision important for visual acuity (6). The high disease incidence and associated central visual handicap make RPGR one of the most clinically important RP genes and the focus of a large number of studies aimed at understanding its disease mechanism and the development of effective therapies (7).

RPGR is expressed in a complex pattern, with both default (RPGRdefault or constitutive) and ORF15 (RPGRORF15) variants having been described. RPGRdefault spans exons 1–19 (hence also referred to as RPGRex1-19) and shares the first 14 exons with RPGRORF15 (8, 9). Exons 1–10 code for an RCC1 (regulator of chromatin condensation 1)-like domain, suggestive of a role in regulating the activity of small GTPases. RPGRORF15 terminates in a large alternative ORF15 exon, characterized by a purine-rich, highly repetitive sequence coding for multiple Glu-Gly repeats followed by a C-terminal tail region rich in basic amino acid residues (basic domain) with unknown function. Although both variants are ciliary proteins, RPGRdefault is the predominant form in a broad range of ciliated tissues (10), whereas RPGRORF15 is found primarily in the connecting cilia of photoreceptor cells (10, 11). The connecting cilium is structurally analogous to the transition zone of primary or motile cilia and links the biosynthetic inner segment to the photo sensing outer segment and serves as a gateway for protein trafficking between these cellular compartments. Although RPGRdefault has yet to be linked to any human disease, genetic studies (8, 12) have established an essential role for RPGRORF15 in photoreceptor function and survival. The ORF15 exon is a mutation hotspot in RPGR, with mutations identified in this region in up to 60% of patients with X-linked RP (8, 13, 14). Notably, in-frame deletions or insertions that alter the length of this region are well tolerated, as are missense changes (2, 15–19). However, frame shift mutations that lead to loss of the C-terminal basic domain are always disease causing, underscoring the functional importance of this domain (7).

To explore RPGR gene function and disease mechanism, we developed the first mouse model, to our knowledge, carrying a null mutation by ablation of both RPGR isoforms (11). Rpgr-null mice manifest a slowly progressive retinal degeneration characterized by early cone opsin mislocalization in cell bodies and synapses and reduced levels of rhodopsin in rods that are detectable at weaning (11). However, significant loss of photoreceptor cells is only evident after 12–16 mo of age. Thus, the early opsin mislocalization appears to reflect a primary defect rather than the result of secondary changes following cell degeneration. The disease course of Rpgr−/− mice is slow considering the human disease with RPGR mutations is severe, which initially generated some debate as to the cause for this discrepancy. Subsequent studies in independent KO mouse lines found a similar slowly progressing disease, indicating that species differences likely account for the disparate disease severity. A naturally occurring rd9 mouse, carrying a frame shift mutation in the ORF15 exon that disrupts RPGRORF15 but leaves RPGRdefault intact, manifests a virtually identical phenotype (20). RPGRORF15 was shown to interact with a number of transition zone proteins essential for ciliary maintenance highlighting a central role for RPGRORF15 in this subcellular compartment. It is generally thought that RPGRORF15 plays a role in regulating protein trafficking through the connecting cilium (11, 21, 22); however, the molecular mechanisms of RPGRORF15 function are not understood.

A distinguishing feature of the ciliary transition zone is the myriad of posttranslational modifications present on axonemal microtubules that set them apart from other microtubule populations in the cell (23–25). The majority of these modifications concentrate on the disordered and highly negatively charged C-terminal tails of tubulin (25). One such abundant modification is glutamylation, the addition of glutamates (one or multiple) to internal glutamates on the tubulin tails. It is catalyzed by glutamylases belonging to the tubulin tyrosine ligase like (TTLL) family (25, 26), many of which localize to cilia (26). Tubulin glutamylation can modulate the affinity of microtubule binding proteins for the microtubule (27–29). Both hyper- and hypo-glutamylation disrupt ciliary functions (30–32). Recently, a member of the TTLL family, TTLL5, was reported to underlie a form of human retinal dystrophy with an early and prominent cone involvement (33). Intriguingly, mice with targeted disruption of the Ttll5 gene showed changes in tubulin glutamylation levels only in sperm, but no phenotype related to retinal function was reported (34). Thus, the pathogenic process leading from a gene defect in TTLL5 to retinal dystrophy remained unexplained.

In this study, we identify RPGRORF15, the RPGR variant predominantly expressed in photoreceptors, as a novel glutamylation substrate. We show that RPGRORF15 recruits TTLL5 via its C-terminal basic domain and is glutamylated specifically by TTLL5 in a region that shares glutamylation consensus motifs with the α-tubulin C-terminal tail. Loss of TTLL5 abolishes RPGRORF15 glutamylation with no detectable effect on tubulin glutamylation levels, and results in a cellular pathology that phenocopies that of Rpgr null animals. Our findings demonstrate that RPGRORF15 is the physiological substrate of the TTLL5 glutamylase and connect the recently reported TTLL5-associated retinal dystrophy pathophysiology to RPGR dysfunction, integrating it into the large family of RPGR-related retinal dystrophies.

Results

RPGRORF15 Is Glutamylated in Its Glu-Gly–Rich Repetitive Region.

Axonemal microtubules are glutamylated. The monoclonal antibody GT335 is widely used to detect this modification (35). In the retina, GT335 prominently stains the connecting cilia of photoreceptors (Fig. 1A, Upper) and primary cilia in the inner retina. It is generally believed that GT335 stains cilia by binding to glutamylated tubulin. However, in the Rpgr−/− mouse retina, we found that the GT335 signal in photoreceptor connecting cilia was greatly diminished (Fig. 1A, Lower), whereas staining in other parts of the retina was unchanged. Because the GT335 antibody does not recognizes glutamate branches exclusively on tubulin, we also tested the retinas with the B3 monoclonal antibody known to be specific for polyglutamylated α-tubulin (36, 37) (the antigenic epitopes of glutamylation specific antibodies are illustrated in Fig. 1I). The B3 antibody gives comparable if not elevated signal intensity in the Rpgr−/− mouse retina (Fig. 1A). These findings suggest that GT335 stains primarily RPGRORF15 at the photoreceptor connecting cilia. To confirm this finding, we performed immunoblotting analyses of retinal lysates from WT and Rpgr mutant retinas (Fig. 1C–E). An RPGR antibody detects two major variants in the WT retina: RPGRORF15 and RPGRdefault, that migrate at molecular weights of ∼200 kDa (Fig. 1C, lane 1, solid arrowhead) and 100 kDa (open arrowhead), respectively. As expected neither variant was present in the Rpgr−/− retina (lane 3). An RPGRdefault-specific KO mouse had only the RPGRORF15 variant (lane 2), whereas the rd9 mouse had only the RPGRdefault variant (lane 4). When the same samples were probed with GT335, only those that retained the RPGRORF15 variant showed a band at the higher molecular weight (Fig. 1D, lanes 1 and 2). Similarly, mouse brains, which do not express the ORF15 variant, did not show a high-molecular-weight band (lane 5). Notably, neither GT335 nor B3 (Fig. 1E) detected a decrease in tubulin glutamylation in mice lacking the RPGRORF15 variant. Moreover, the α-tubulin signal was comparable among all lanes (Fig. 1F). Thus, tubulin expression and glutamylation levels were unchanged in Rpgr mutant retinas. These results indicate that the GT335 staining at the photoreceptor connecting cilia can be attributed primarily to RPGR, and that RPGRORF15 and not RPGRdefault is glutamylated in photoreceptors.

Fig. 1.

RPGRORF15, but not RPGRdefault, is glutamylated in vivo. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of retinal cryosections. (Left) RPGR (green) localizes to the connecting cilia as indicated by its position just distal to the ciliary rootlet (red) in the control retina but is absent in the RPGR−/− retina. (Right) GT335 (green) and B3 (red) antibodies both stain the connecting cilia in the control; GT335 signal is greatly diminished in the RPGR−/− retina, whereas B3 is maintained or slightly enhanced. GT335 is a monoclonal antibody that detects monoglutamylation; B3 detects longer glutamate chains on α-tubulin. Insets show images at higher magnification. (B) Schematic representation of a photoreceptor cell. CC, connecting cilia; BB, basal bodies. (C and D) Immunoblotting of mouse tissue extracts with antibodies indicated at the bottom of each blot. (Lower) Same blots probed with γ-tubulin as a loading control. Lane 1, WT retina; 2, RPGRdefault KO (lacking RPGRdefault only) retina; 3, RPGR KO (lacking both RPGRdefault and RPGRORF15 isoforms) retina; 4, rd9 (lacking RPGRORF15) retina; 5, WT brain. (C) An RPGR antibody detected both RPGRORF15 (solid arrowhead) and RPGRdefault (open arrowhead) in the WT retina. RPGRORF15 was retained (solid arrowhead) in the RPGRdefault KO retina but was lost in the full RPGR KO and the rd9 retinas. (D) GT335 reacts with RPGRORF15 (arrowhead) but not with RPGRdefault. Glutamylated tubulin bands (arrow) show comparable intensities in all samples. Brain expresses only RPGRdefault and hence does not have the higher-molecular-weight RPGRORF15 band (lane 5). (E) The B3 antibody shows similar signal intensity in all lanes. (F) α-Tubulin expression levels are comparable in all samples, indicating that tubulin glutamylation is similar in all samples. (G) RPGRORF15 is predominantly monoglutamylated. (Upper) Retinal lysates from a WT mouse or an Rpgr-null mouse expressing human RPGRORF15 (through AAV gene transduction) were run in triplicate and probed with the GT335, polyE, and 1D5 antibodies. Glutamylated mouse and human RPGRORF15 is readily detected with GT335, which recognizes branched glutamate side chains. PolyE, which reacts with the side chains of three or more glutamates, did not detect RPGR. 1D5, which reacts with the chains of two or more glutamates, detects trace amounts of RPGR on prolonged exposure. (H) RPGRORF15 from human photoreceptors is glutamylated. (Left) Three donor retinal lysates (Ret 1, 2, and 3) were run together with recombinant human RPGRORF15 expressed in mouse retina (aav, lane 1) on an immunoblot probed with GT335. Bands corresponding to the position of RPGR were detected (arrowhead). (Right) Following immunoprecipitation with an RPGR antibody, the bound fraction was enriched for the GT335-reactive band (Ret-IP). Ret is lysate before IP (5% input). Note that the tubulin band (arrow) was present in the lysate (Ret) but was lost in the eluate (Ret-IP). Separate blot probed with an RPGR antibody confirmed enrichment of RPGR in the eluate and reduction in the flow-through fraction. (I) (Left) Schematic diagram of glutamylation. The sequence in the diagram can be found in RPGR and the α-tubulin C-terminal tail but does not denote an exact, experimentally mapped modification site. Epitopes for GT335, B3, polyE, and 1D5 antibodies are shown. (Right) Chemical structure of two postranslationally added glutamates (the first one connected to the main chain of the target protein through an isopeptide bond).

The GT335 antibody reacts with the branched glutamate that is first added to an internal glutamate in the sequence of the protein being modified (Fig. 1I) and thus does not distinguish between monoglutamylation (addition of one glutamate) or polyglutamylation (addition of longer chains of glutamate residues) (38). Therefore, it was not clear whether RPGRORF15 is mono- or polyglutamylated. To resolve this question, we performed immunoblotting analysis with additional antibodies: 1D5 (also known as ID5), which recognizes glutamate chains longer than two (39), and polyE, which recognizes C-terminally located glutamate chains of four or more residues (26). In the WT mouse retina, polyE did not react with RPGRORF15, whereas 1D5 detected only trace amounts (Fig. 1G, Left), indicating RPGR is primarily monoglutamylated. We further analyzed recombinant human RPGRORF15 expressed in the Rpgr−/− mouse retina via AAV (adeno-associated virus)-mediated gene transduction, and found nearly identical results (Fig. 1G, Right). These data indicate that RPGRORF15 is primarily monoglutamylated regardless of species of origin. To rule out the possibility that the mouse photoreceptor environment was responsible for glutamylation of recombinant human RPGRORF15, we examined lysate of donor human retinas directly. Three independent donor retina extracts (Ret1, 2, and 3) showed GT335-reactive bands that comigrated with recombinant human RPGRORF15 (aav) by immunoblotting (Fig. 1H, Left). Following immunoprecipitation with an RPGR antibody, GT335-reactive RPGR was highly enriched in the bound fraction (Ret-IP) (Fig. 1H, Right), confirming that native human RPGRORF15 is glutamylated.

RPGRORF15 Interacts with TTLL5 via Its Basic Domain and Is Glutamylated by TTLL5.

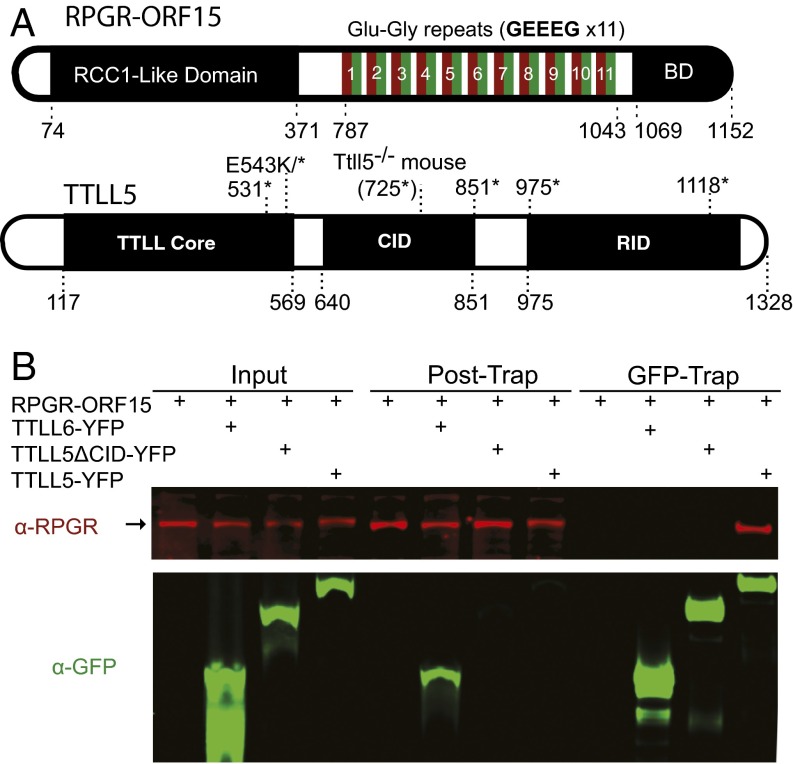

The RPGRORF15 sequence diverges from the default variant, which is not glutamylated, at its C-terminal half. The C-terminal half of RPGRORF15 consists of a Glu-Gly rich repeat region followed by a C-terminal basic domain (Fig. 2A). Sequence analysis of the repeat region identified 11 glutamate rich consensus motifs (GEEEG) homologous to the α-tubulin C-terminal tail (Fig. 2A). The number of these motifs depends on the mouse strain: 18 were found in C57BL6 and 22 in the 129/Sv strain. Thus, the repetitive region is a natural candidate for glutamylation. The basic domain next to the repetitive region is highly conserved among vertebrates, but it was not known whether it has any role in RPGRORF15 glutamylation. To explore this question we examined data from a yeast two-hybrid protein interaction screen in which the basic domain from human RPGRORF15 was used as bait (Fig. S1). Among candidate proteins identified as potential interaction partners, one group represented TTLL5, a glutamylase of the TTLL superfamily. Sequence analysis indicated that the region of TTLL5 that interacted with RPGRORF15 overlapped with the cofactor interaction domain (CID) thought to bind transcription activators (34). To verify a physical interaction between RPGRORF15 and TTLL5, we carried out pull-down assays using lysates of transiently transfected HEK 293 cells. Recombinant RPGRORF15 was coexpressed with YFP-tagged full-length TTLL5 or TTLL5 missing the CID. Full-length YFP-tagged TTLL6 and TTLL7 (glutamylases also belonging to the TTLL superfamily) were used as negative controls. Full-length TTLL5, but not TTLL6 or TTLL7, was able to pull down RPGRORF15 after cell lysates were put through a GFP-Trap (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2A). TTLL5 ΔCID also failed to form a stable complex with RPGRORF15 as clearly indicated by lack of RPGRORF15 recovery in the GFP-Trap (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2B). Full-length TTLL5 not only bound to but also glutamylated RPGRORF15, as indicated by the colabeling of the RPGRORF15 band by GT335 (Fig. S2B) and an upward shift in its apparent molecular weight detectable on a longer gel run (Fig. S2B, white arrowheads). Both TTLL5 and TTLL5 ΔCID also produced a number of high-molecular-weight, GT335-positive proteins. These bands are unrelated to RPGR as they did not react with RPGR antibodies and also appeared in samples not transfected with RPGR. This observation is consistent with a previous study that detected similar unknown high molecular substrates for TTLL5 in cultured human cell lines (26). Together, our yeast two-hybrid and cellular assays indicate that RPGRORF15 interacts specifically with TTLL5 and that the CID of TTLL5 and the C-terminal basic domain of RPGRORF15 are critical for a specific interaction between these proteins.

Fig. 2.

RPGRORF15 interacts with TTLL5 via its C-terminal basic domain (BD). (A) Diagrams showing the domain organization of RPGRORF15 and TTLL5. The RCC1-like domain is shared among all RPGR variants, whereas the Glu-Gly–rich region and the basic C-terminal domain are unique to RPGRORF15. Human RPGRORF15 possesses 11 tandem GEEEG repeats, whereas mouse RPGRORF15 possesses 18. TTLL5 is comprised of a core tubulin tyrosine ligase-like (TTLL) domain, a cofactor interaction domain (CID), and a receptor interaction domain (RID). Point and deletion mutations relevant to this study (see later sections) are denoted on the diagrams. (B) Confirmation of the physical interaction between RPGRORF15 and TTLL5 by GFP-trap precipitation and immunoblotting of transiently transfected HEK293 cell lysates. RPGRORF15 was detected with a polyclonal antibody (red; Upper). All TTLL constructs were YFP-fusions. TTLL5, TTLL5 ΔCID, and TTLL6 (Lower) were detected with a GFP antibody (green; Lower). Input, posttrap (unbound), and GFP-Trap (bound) fractions were analyzed. In the bound (GFP-Trap) fractions, TTLL5, TTLL5 ΔCID, and TTLL6 proteins were efficiently recovered. RPGR was recovered only together with TTLL5. GFP-Trap results were reproduced in more than four independent trials.

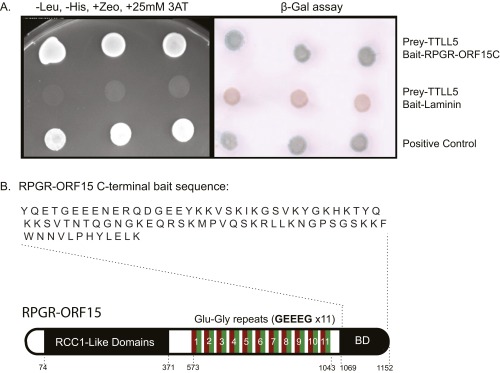

Fig. S1.

Identification of TTLL5 as a putative interacting partner of RPGR through yeast two-hybrid screens. (A) Confirmation assays. Image on the Left shows growth of yeast colonies. Presence of both TTLL5 and RPGR promoted growth. TTLL5 cotransfected with laminin did not allow growth (negative control). Positive control yeast cells carried SV40 large T antigen and P53, two proteins known to interact. Image on the Right shows lacZ expression in yeast cells where bait and prey plasmids were able to bind each other. (B) Sequence of the human RPGRORF15 C-terminal basic domain used as bait in the screen.

Fig. S2.

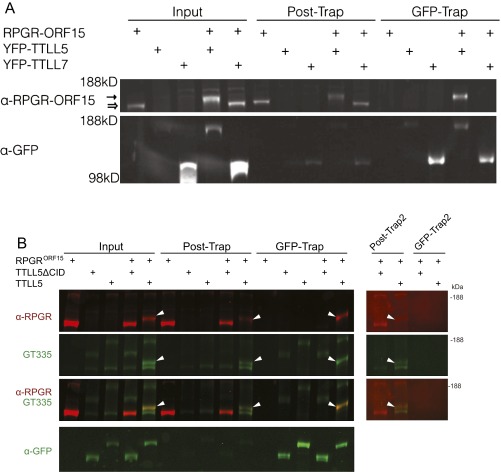

RPGRORF15 interacts stably with full-length TTLL5, but not with the closely related paralog TTLL 7 or TTLL5 ΔCID. All TTLL constructs were YFP-fusions. (A) RPGRORF15 is recovered together with TTLL5 in the GFP-Trap fraction in cotransfected heterologous cells. TTLL5 also glutamylates and reduces the electrophoretic mobility of RPGRORF15, as indicated by an upward shift (hollow to solid arrow). TTLL5 paralog family member TTLL7 does not interact with nor does it glutamylate RPGRORF15. (B) RPGRORF15 interacts with and is glutamylated by full-length TTLL5 but not TTLL5ΔCID. (Left) RPGRORF15 is recovered from the GFP-trap fraction only when cotransfected with TTLL5-YFP. Glutamylation of RPGRORF15 is detected by the GT335 antibody and is also marked by an upward shift in mobility (white arrowheads). Additional glutamylated (GT335 reactive) bands were also observed. These bands are unrelated to RPGR (they are present also in cells transfected only with TTLL5 or TTLL5 ΔCID) and are presently unknown. (Right) A second round of GFP-Trap binding was performed using Post-Trap supernatants to exclude the possibility that glutamylated RPGRORF15 bound nonspecifically to GFP-Trap in the absence of TTLL5-YFP. Post-Trap2 and GFP-Trap2 are unbound and bound fractions, respectively, from the second round of the GFP-Trap experiment. White arrowheads indicate glutamylated RPGRORF15. The results show that residual RPGRORF15 from the first round Post-Trap fraction, in which TTLL5-YFP fusion proteins were largely depleted, did not bind to GFP-Trap in isolation (in the absence of TTLL5-YFP).

RPGRORF15 Is the Physiological Substrate for TTLL5 in the Retina.

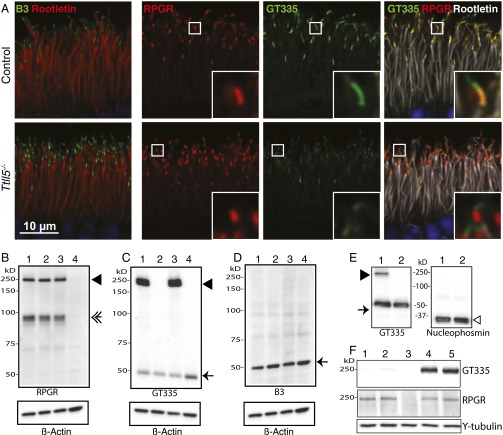

We next investigated the relationship between RPGRORF15 and TTLL5 in vivo. Like RPGRORF15, TTLL5 was also reported to localize in the vicinity of the photoreceptor connecting cilium (33). A mouse line carrying a targeted disruption of the Ttll5 gene was reported to be viable with no overt retinal phenotype (34). We examined the state of RPGRORF15 glutamylation in the retina of this mutant mouse. Immunostaining of cryo-sections illustrated that glutamylation of ciliary tubulin was not diminished nor was RPGR expression altered on loss of TTLL5 (Fig. 3A). In contrast, GT335 signal was nearly absent (Fig. 3A). Higher-magnification views revealed two domains of GT335 signal: a strong one that overlapped with RPGR in the transition zone and a weak one that extended distally and represents axonemal microtubules. In Ttll5 mutant photoreceptors, GT335 signal in the transition zone was absent but the portion attributable to glutamylated tubulin remained. These data indicate that RPGRORF15 glutamylation is abolished, whereas tubulin glutamylation is not visibly affected in the absence of TTLL5. This interpretation was further corroborated by immunoblotting analysis. Loss of TTLL5 had no effect on the expression levels of RPGR (Fig. 3B) nor did it affect tubulin glutamylation (Fig. 3 C and D). However, glutamylation of RPGRORF15 was abolished as indicated by the absence of GT335 staining (Fig. 3C). In heterozygous Ttll5 retina, the glutamylation level of RPGRORF15 was indistinguishable from that of WT (Fig. 3B), indicating that the enzyme level is not limiting. These data indicate that RPGRORF15 is the major physiological substrate for TTLL5 in the retina. This conclusion is reinforced by our analysis of nucleophosmin, a protein that was reported to be glutamylated in HeLa cells (40) and in Xenopus oocytes (41). It interacts with the C-terminal basic domain of RPGRORF15 (42) and thus could be in close proximity to RPGRORF15 in photoreceptors. However, immunoblotting (Fig. 3E) analysis demonstrates that nucleophosmin is not glutamylated in the murine retina. These findings rule out nucleophosmin as a possible mediator of pathogenesis in TTLL5-related retinal dystrophy. Because both RPGRORF15 and TTLL5 localize at or near the connecting cilia of photoreceptors, we next asked whether RPGRORF15 is modified in this subcellular compartment or at an earlier step of protein biosynthesis. RPGRORF15 is known to be anchored by RPGRIP1 in the connecting cilia, and in Rpgrip1 KO mice, RPGRORF15 is expressed at normal levels but fails to localize to the connecting cilia (43). By immunoblotting with GT335, we found that RPGRORF15 glutamylation was greatly diminished in the Rpgrip1 mutant retinas compared with the WT controls (Fig. 3F). This finding suggests that RPGRORF15 is glutamylated by TTLL5 primarily at the connecting cilia.

Fig. 3.

RPGRORF15 is glutamylated by TTLL5 in vivo. (A) Analysis of WT and Ttll5 mutant retinal sections by immunofluorescence. Polyglutamylation of ciliary tubulin (indicated by staining with the B3 antibody) is not diminished on TTLL5 loss (green; leftmost panels), nor is RPGR itself (red; second column). However, GT335 signal is greatly diminished on TTLL5 loss. Zoomed in images in Insets reveal two domains of GT335 signal: one overlapping with RPGR and the other extending more distally. The GT335 signal in the distal domain, which corresponds to glutamylated tubulin, is unaffected by the Ttll5 mutation. (B–D) Immunoblotting analysis of Ttll5+/− (lane 1), Ttll5−/− (lane 2), WT (lane 3), and Rpgr−/− (lane 4) mouse retinal lysates. Ttll5+/−, Ttll5−/− and WT mice were littermates. Antibodies used for immunoblotting are marked under each panel. RPGRORF15 (solid arrowhead) and RPGRdefault (double arrow) expression was unchanged in the Ttll5−/− mutant (B). Glutamylation of RPGRORF15 is abolished in the Ttll5−/− retina (lane 2 of C), whereas tubulin glutamylation (arrow) remains constant. The B3 antibody, which recognizes polyglutamylated tubulin specifically, shows comparable signal intensity among all samples (D). (Lower) Blots reprobed for β-actin as loading controls (B–D). Similar results were obtained from two independent experiments. (E) Nucleophosmin is not glutamylated. Mouse retinal lysates probed with GT335 show signal for tubulin (arrow) in both WT (1) and Ttll5−/− mutant (2) samples, and RPGRORF15 (solid arrowhead) only in the WT sample. No GT335-reactive bands at the molecular weight of nucleophosmin (∼33 kDa) were detected even after prolonged exposure (Left). Nucleophosmin (open arrowhead) was readily detected in both samples (Right). (F) Glutamylation of RPGRORF15 is greatly diminished in the Rpgrip1−/− retina. (Top) GT335 immunoblot of retinal extracts from Rpgrip1−/− retinas (lanes 1 and 2) at age postnatal day 20 and age-matched WT controls (lanes 4 and 5). Four mice of each genotype were analyzed in this experiment. Lane 3: Rpgr−/− as a negative control. (Middle) Immunoblot of the same retinal lysates probed with an RPGRORF15 C-terminal antibody. (Bottom) A γ-tubulin immunoblot is shown as a loading control.

Ttll5−/− Mice Develop a Retinal Phenotype Similar to Rpgr−/− Mice.

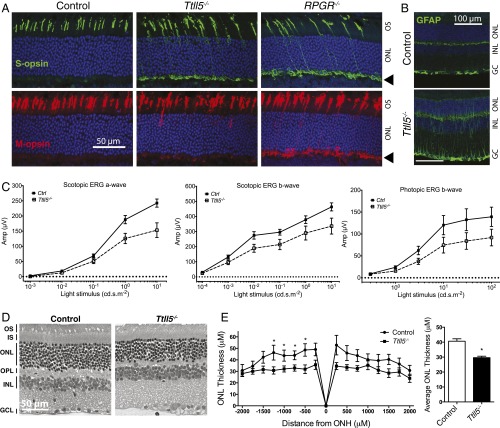

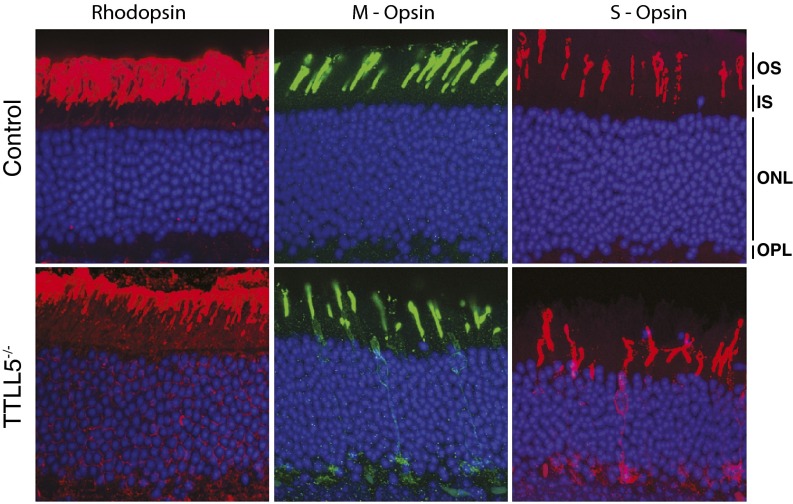

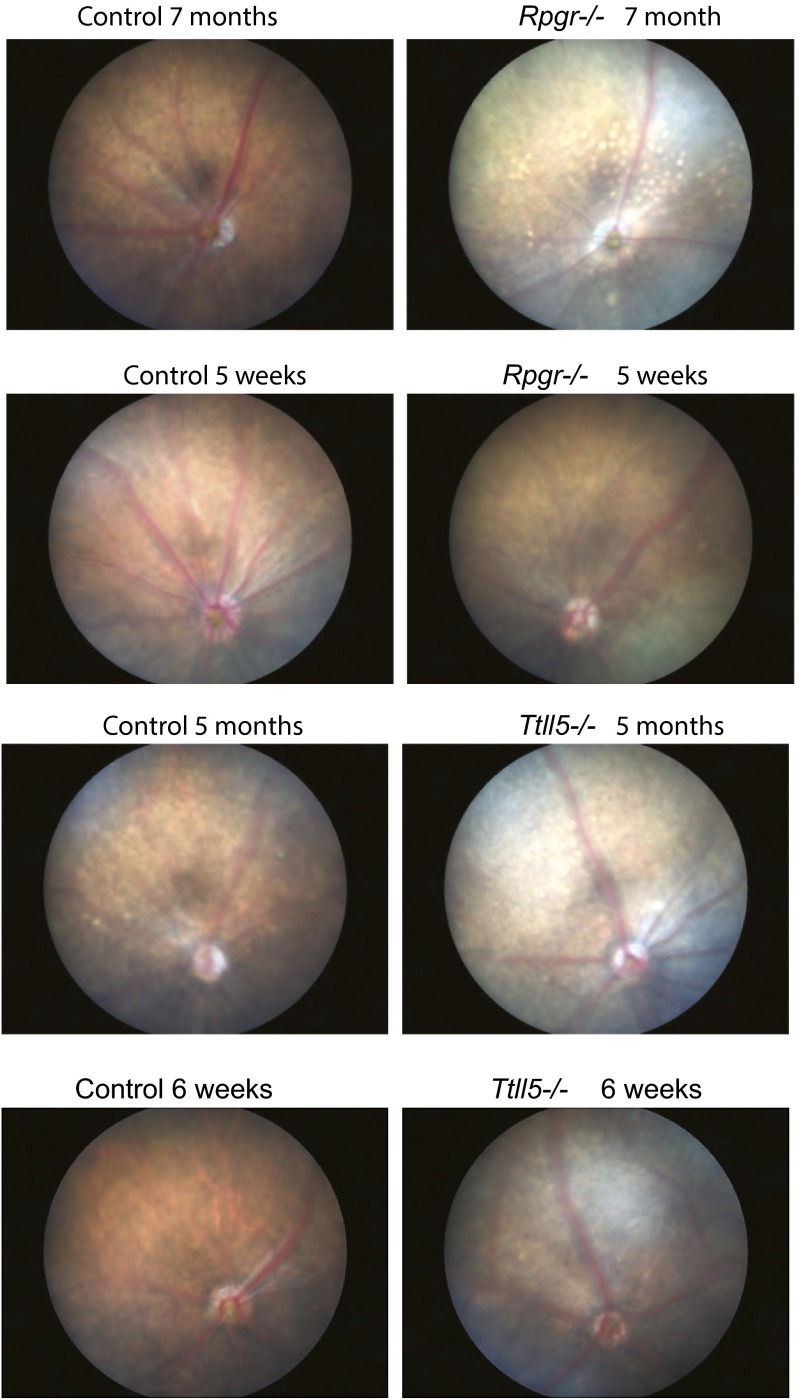

Although the initial study of the Ttll5−/− mice did not find an overt retinal defect based on histology (34), we thought it likely that using additional assays and extending the observation period to older ages might reveal a late-onset, slowly progressive form of photoreceptor degeneration, in line with the phenotypes observed in the Rpgr-null mice. Indeed, immunofluorescence analysis at a young age (postnatal 20–40 d) found ectopic localization of S- and M-cone opsin in the cell body (Fig. 4A). Both rhodopsin and cone opsins mislocalized at older ages (Fig. S3). Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a general indicator of photoreceptor stress and degeneration, is also up-regulated in Ttll5−/− retinas at older ages (Fig. 4B). Early cone opsin mislocalization is also a distinguishing feature of Rpgr−/− mice (Fig. 4A) at the same age (11). A second distinguishing feature in Rpgr−/− mice is a change of fundus color from orange red to a metallic gray from an early age, which may reflect reduced rhodopsin content in the outer segments (11). This feature was also observed in the Ttll5−/− mice (Fig. S4).

Fig. 4.

Ttll5−/− mice develop late-onset, slowly progressive photoreceptor degeneration that phenocopies Rpgr−/− mice. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of cone opsins at a young age (20–40 d). Comparison with the control shows both the S- and M-opsins mislocalized to the cell body and the synaptic layer (arrowhead) in the Ttll5−/− and Rpgr−/− retinas. (B) GFAP is up-regulated in the Ttll5−/− retinas at older ages (20–22 mo old). (C) ERG stimulus intensity–amplitude functions in aged mice. ERG amplitudes in Ttll5−/− mice are significantly lower than control mice of this age (20–22 mo; P < 0.0001 for scotopic ERG a- and b- waves; P = 0.0013 for photopic ERG b-wave in two-way ANOVA). (D) Light microscopy of retina sections show mild thinning of the photoreceptor layers. (E) Measurements of ONL thickness at different positions from the optic nerve head (ONH) to the far peripheral retinas (Left) shows thinning of ONL in the Ttll5−/− mice (n = 11) compared with the controls (n = 9). Overall, the mean ONL thickness (Right) in Ttll5−/− retinas was significantly reduced compared with controls (P < 0.05). Mice were 20–22 mo old in D and E.

Fig. S3.

Immunofluorescence analysis of rhodopsin and cone opsins at 20–22 mo. Rhodopsin staining reveals outer segments are shorter in the mutant with some mislocalization of rhodopsin in the inner segments and nuclear layer. Both the S- and M-opsins mislocalize to the cell body and the synaptic layer in the Ttll5−/− retinas, but not in that of controls.

Fig. S4.

Representative fundus photographs from Rpgr and Ttll5−/− mice and age-matched controls. The controls for Rpgr-null mice were age-matched C57BL/6J and, for Ttll5 mice, WT littermates were used.

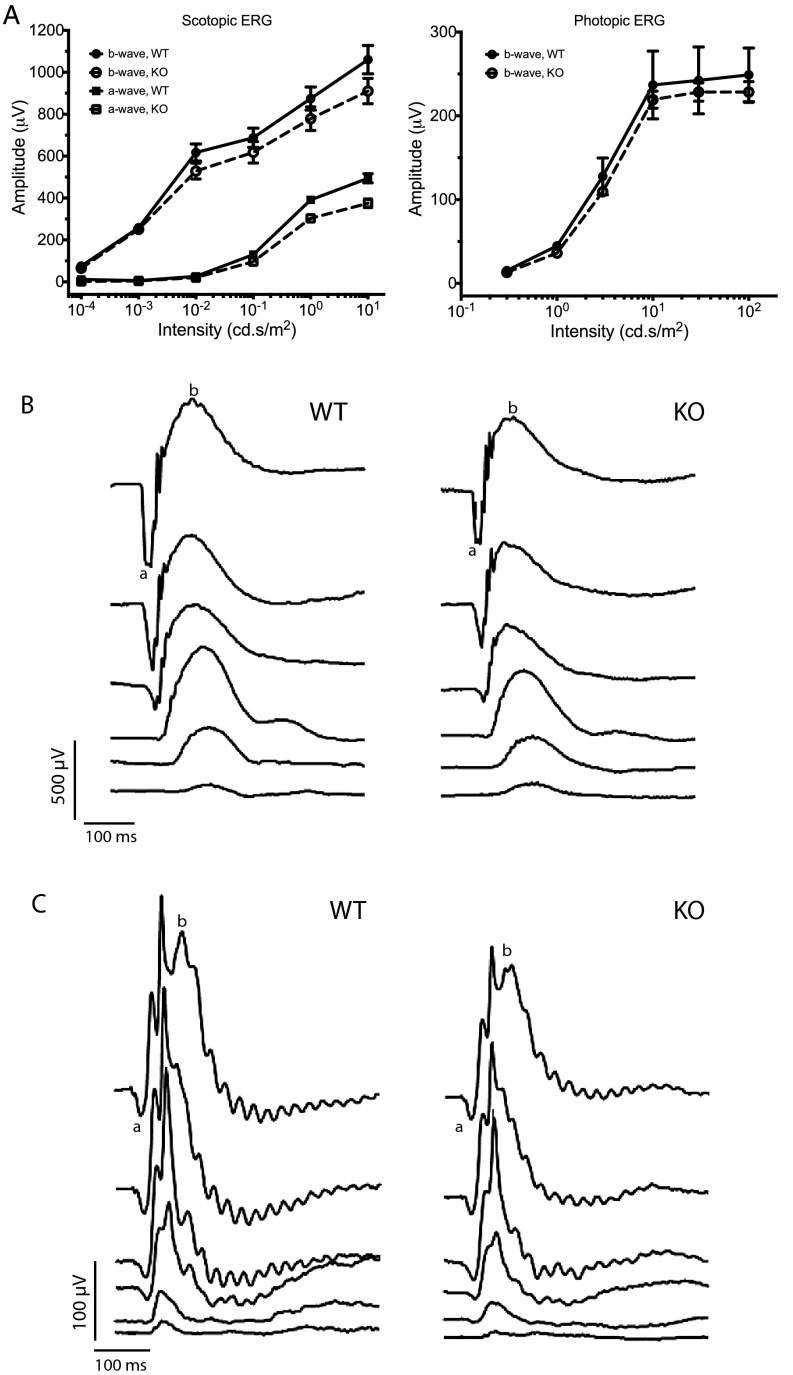

Electroretinograms (ERGs) that measure photoreceptor function were recorded at 4 and 20–22 mo of age. The dark-adapted ERG reflects primarily rod function at lower stimulus intensities and mixed rod and cone function at high stimulus intensities, whereas light-adapted ERG reflects cone function. At the younger age, rod and cone ERG waveforms and amplitudes were comparable between the control and mutant mice, with the exception of the rod a-wave amplitude at the highest stimulus intensity where the mutant mice showed a borderline decline (Fig. S5). At older ages, both rod and cone ERG amplitudes declined significantly (Fig. 4C). Morphometric measurements of plastic embedded retinal sections also showed a significant thinning of the photoreceptor layer in aged animals (Fig. 4 D and E). The overall disease course and accompanying features of Ttll5−/− mice thus appear to phenocopy those of Rpgr−/− mice.

Fig. S5.

ERG analysis of Ttll5−/− (KO) mice and littermate WT mice at 4 mo of age. (A) ERG stimulus intensity-amplitude functions. (B) Representative dark-adapted ERG waveforms. (C) Representative light-adapted ERG waveforms.

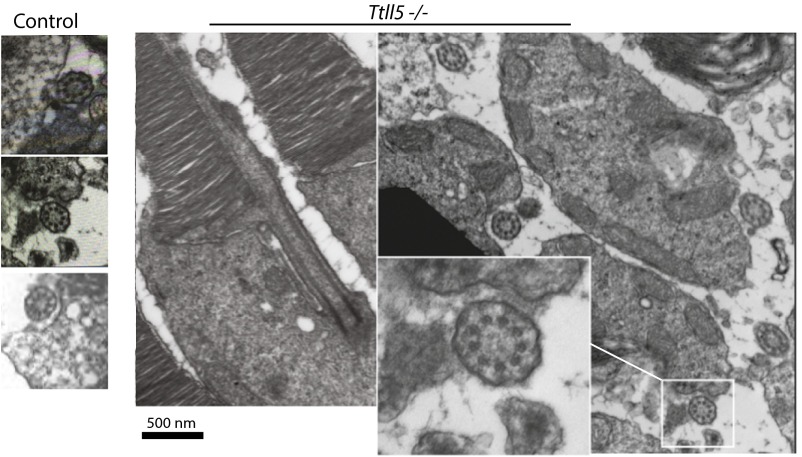

Sperm from Ttll5−/− mice has defective axonemes (34). Specifically doublet 4 is missing from the 9+2 microtubule arrays. Given the prominent function of TTLL5 in photoreceptors, we asked if loss of TTLL5 might have caused structural defects in photoreceptor connecting cilia. We performed transmission electron microscopy of cross sections through the connecting cilia of WT and mutant photoreceptors (Fig. S6). Unlike sperm tails, which are motile and therefore have a central microtubule pair, the connecting cilia have a 9+0 configuration. Examination of the electron micrographs found no apparent microtubule defects in the mutant, at least not at the level of the connecting cilia.

Fig. S6.

The 9+0 microtubule doublet array appeared normal in the photoreceptor connecting cilia of Ttll5−/− mice. Transmission electron micrographs showing cross-sectional views of the connecting cilia. Mice were at 20 mo of age. Controls and mutant mice were littermates. Two animals of each genotype were examined.

RPGR Glutamylation in Vivo Requires Both the Glu-Rich Repetitive Region and the Basic Domain.

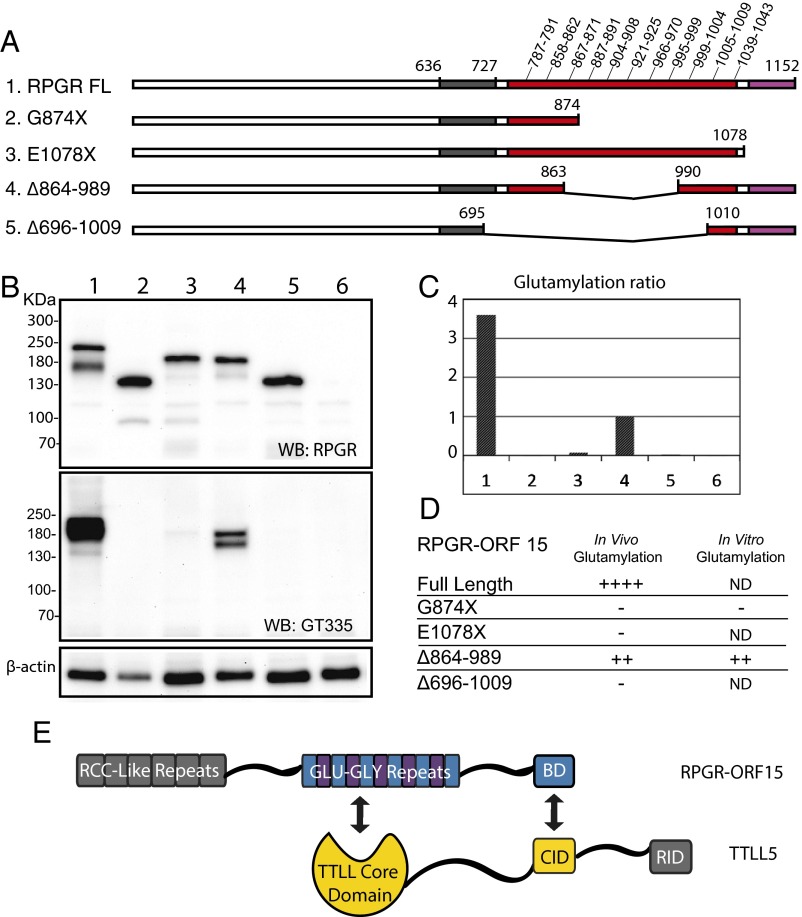

We postulated that binding of the basic domain of RPGRORF15 to the CID recruits TTLL5 to glutamylate the RPGRORF15 Glu-Gly repeat region at multiple consensus sites along its length. To test this hypothesis in vivo, we packaged a series of human RPGRORF15 deletion constructs (Fig. 5A) into an AAV vector under the control of a photoreceptor-specific promoter and injected them into the subretinal space of Rpgr−/− mice. Retinal lysates expressing recombinant RPGRORF15 were subjected to immunoblot analysis. Recombinant proteins were expressed at comparable levels (Fig. 5B, Top). GT335 immunoblotting (Fig. 5B, Middle), indicated that full-length RPGRORF15 was strongly glutamylated (lane 1), whereas constructs missing the basic domain showed no detectible glutamylation (G874X and E1078X, lanes 2 and 3). Δ864–989, which lacks more than one third of the Glu-Gly repeat region and 6 of the 11 glutamylation consensus motifs, but retains the basic domain, is moderately glutamylated (lane 4). Δ696–1009, which retains a single Glu-Gly motif (the last one next to the basic domain), showed no detectable glutamylation (lane 5). Interestingly, a recent study tested the therapeutic efficacy of RPGRORF15 deletion constructs Δ864–989 (ORF15-L) and Δ696–1009 (ORF15-S) and showed that the former was functional but the latter was not (17). Two of the constructs were also tested in cultured cells with similar results (Fig. 5D). The in vivo and in vitro data are quantified and summarized in Fig. 5 C and D, respectively. The in vivo experiments in photoreceptors suggest that RPGRORF15 is glutamylated at multiple sites, and partial elimination of the consensus sites appears to result in a matching decrease in glutamylation levels. These data confirm the requirement for the C-terminal basic domain for RPGRORF15 glutamylation by TTLL5.

Fig. 5.

RPGR glutamylation in vivo requires both the C-terminal basic domain and the Glu-Gly–rich region. (A) Diagrams of human RPGRORF15 expression constructs packaged into AAV vectors. The Glu-Gly–rich region is marked in red and the C-terminal basic domain in magenta. The position of glutamylation consensus motifs is shown in the schematic for the full-length (FL) construct. (B) Immunoblots of retinal extracts from Rpgr−/− mice injected with RPGR expression constructs. Lanes 1–5 match the construct numbers shown in A, and lane 6 is an uninjected control. Full-length RPGR and to a lesser extent RPGRΔ864–989 are glutamylated as indicated by detection with GT335 (Middle). Probing with an RPGR antibody shows expression levels for recombinant RPGR (Top). Reprobing blots with β-actin provides a loading control (Bottom). (C) Quantification of glutamylation levels by densitometry after normalizing for RPGR levels, with sample 4 level set arbitrarily at 1. These results are summarized in D. ND, not determined. Similar results were obtained from two independent experiments. (E) Schematic diagram illustrating mapped interactions between RPGR and TTLL5.

Impact of TTLL5 Disease Mutants on RPGRORF15 Glutamylation.

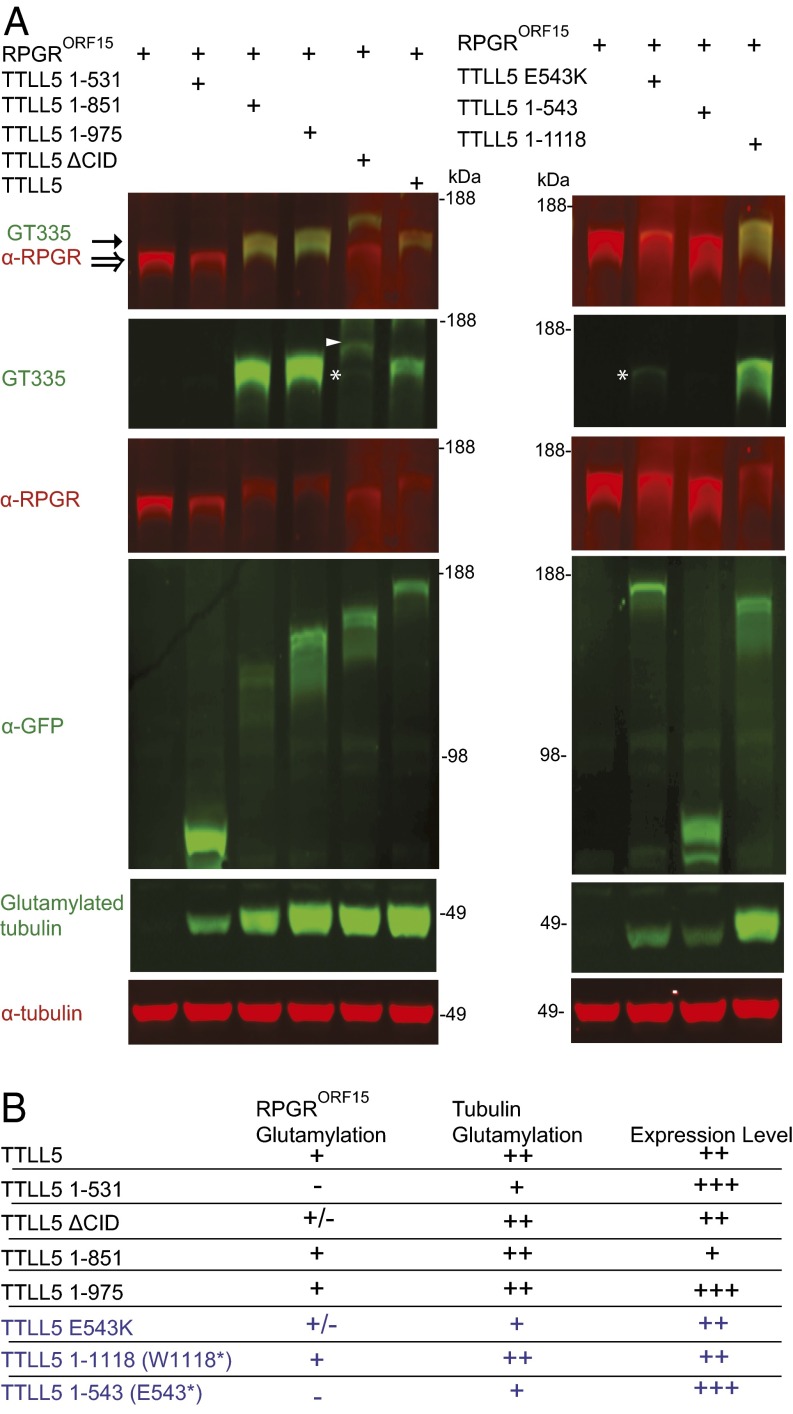

To define critical domains required for glutamylation of RPGRORF15 and to explore the pathogenicity of mutant alleles, we next examined a series of deletion mutants of TTLL5 for their ability to modify RPGRORF15, as well as three disease-causing mutations by cotransfection in 293 cells. Five disease-causing TTLL5 alleles were identified in patients with retinal dystrophy, all of which are recessive (33), indicating that they are loss-of-function alleles. Previous studies showed that the N-terminal 569 residues in TTLL5 are part of the TTLL glutamylase core domain and are required for glutamylase activity of TTLL5 (26, 44). An early frame-shift mutant L134Rfs results in an early truncation of the TTLL core and was presumed a null. The E529Vfs*2 mutant is also truncated well within the TTLL5 core domain. We therefore focused on the three remaining disease-causing mutants, E543K, E543* (1-543), and W1118* (1-1118), and analyzed these together with a battery of domain truncation mutants. Consistent with the core domain organization of TTLL5, TTLL5 truncated at residue 531 shows no detectable glutamylation activity, whereas TTLL5 truncated at residues 851 or 975 has robust activity (Fig. 6A, Left). In line with our finding that the CID (640-851) of TTLL5 mediates binding to RPGR, TTLL5 ΔCID only produced a trace amount of glutamylated RPGR, even in a transient overexpression assay system while retaining full glutamylase activity toward tubulin (Fig. 6A, Left). Deletion mutants truncating at codons 851 and 975 that retain the TTLL5 catalytic core and the RPGR binding CID are fully active toward both tubulin and RPGR (Fig. 6A, Left). These data show that the core TTLL domain (1-569) is required for glutamylase activity (for any substrate), but the CID (640-851) is additionally required for efficient RPGRORF15 glutamylation. High-molecular-weight protein(s) unrelated to RPGRORF15 were also glutamylated and migrated as a collection of bands or smear (arrowhead), as reported in a previous study (26). TTLL5 ΔCID produced a band (white arrowhead, Fig. 6A) migrating just above RPGRORF15 along with a higher-molecular-weight smear, whereas TTLL5 produced only higher molecular smears. These bands are unrelated to RPGRORF15 and are also present in cells transfected only with TTLL5 or TTLL5ΔCID (Fig. S2B). The disease-causing charge-reversal mutant E543K and the catalytic core truncation mutant E543* show greatly diminished tubulin glutamylation (Fig. 6A, Right). The E543K mutant, which retains the RPGR adaptor CID produced trace amounts of glutamylated RPGR (indicated by an asterisk), whereas E543* showed no detectable RPGR glutamylation. E543K and E543* thus behave as strong hypomorphic or null alleles. A third disease-causing mutant, W1118* that retains an intact TTLL glutamylase core and the RPGR binding CID, displays full activity toward both tubulin and RPGRORF15 in vitro (Fig. 6A, Right). Interestingly, all three mutants truncated downstream of the CID (1-851, 1-975, W1118*) glutamylated RPGR efficiently but not the unknown high-molecular-weight targets (Fig. 6), suggesting that the C-terminal tail may target TTLL5 to these other substates. Taken together, the results of these cotransfection assays (Fig. 6B) confirm the critical role of the CID in recruiting TTLL5 to modify RPGR. Because the E543X disease mutant behaves as a null, it is highly likely that the early frame-shift mutant L134Rfs would also behave as a null. Thus, the majority of disease-causing mutants are defective for RPGR glutamylation. The only exception is the W1118* mutant. We hypothesize that the C-terminal domain lost in the W1118* allele may have in vivo roles such as protein trafficking or regulatory activities that could not be tested in a heterologous cell culture system. Deciphering the pathogenicity of this allele will require future in vivo studies.

Fig. 6.

Effect of TTLL5 domain deletion and disease mutations on RPGRORF15 glutamylation in transient cotransfection assays. (A) Coexpression of RPGRORF15 and WT TTLL5 in HEK293 cells leads to RPGRORF15 glutamylation as detected by GT335 staining. An early truncation mutant TTLL5 1–531 shows no activity toward RPGRORF15. Deletion of the CID or mutation of a conserved residue E543K in the TTLL core dramatically reduce RPGRORF15 glutamylation as indicated by only residual GT335 staining (denoted by a star). Truncation downstream from CID generally preserves TTLL5 activity toward RPGRORF15 in the in vitro assay. White arrowhead indicates the unknown high-molecular-weight protein that is also gluatmylated. Note an upward shift in molecular weight of RPGRORF15 on glutamylation as denoted by hollow (unmodified) and solid (modified) arrows, consistent with the glutamate addition at multiple Glu-Gly–rich motifs. Expression of YFP-TTLL5 constructs was confirmed with a GFP antibody. This experiment is representative for more than three independent cotransfections. (B) Summary table of RPGR-ORF15 glutamylation by mutant TTLL5 constructs in heterologous cells (disease-causing mutations are shown in blue).

Discussion

Here we report the unexpected discovery that RPGRORF15, the functional variant of RPGR in photoreceptor cilia, is glutamylated by the TTLL family glutamylase TTLL5 and that Ttll5−/− mice phenocopy the Rpgr−/− retinal degeneration phenotype. The significance of our findings is threefold. First, they resolve at the molecular level the pathophysiology of TTLL5 gene mutations that cause retinal dystrophy and connect the RPGR and TTLL5 disease mutations into a common pathway. In the absence of TTLL5, no glutamylation occurs on RPGRORF15, leading to compromised if not abolished function of RPGRORF15 in photoreceptors and cellular defects that resemble loss of RPGRORF15. Second, TTLL5 appears to be highly selective for RPGRORF15, with the CID unique to TTLL5 acting as an adapter to engage the C-terminal basic domain of RPGRORF15. Other TTLL family members do not compensate for TTLL5 in RPGRORF15 glutamylation in vivo, consistent with our in vitro transfection experiments that show that neither TTLL6 nor TTLL7 glutamylates RPGRORF15. The high degree of selectivity of TTLL5 for RPGRORF15 in vivo is likely enhanced by their close proximity at the same subcellular compartment. RPGRORF15 is recruited through its RCC1-like domain by RPGRIP1 (43) to the connecting cilia, whereas TTLL5 localizes to the ciliary base (33). Subsequent engagement of RPGRORF15 with TTLL5 and glutamylation occur primarily at this subcellular compartment. Our study further supports the idea that some TTLL family members, despite their name, act on nontubulin substrates and use accessory domains outside the TTLL core for their recognition. It is possible that TTLL5 also modifies tubulin in vivo as it does in vitro consistent with the axonemal defects observed in the sperm of Ttll5−/− mice (34), although such defects were not observed in our analysis of the retina. Third, our data shed light on the long-standing question regarding the roles of the Glu-Gly–rich region and the conserved C-terminal basic domain in RPGRORF15. RPGRORF15 binds TTLL5 with its basic domain, bringing TTLL5 in close proximity to glutamylation sites along the Glu-Gly–rich repetitive region of RPGR ORF15. This interaction likely forms the basis for the recruitment of TTLL5 to RPGRORF15.

Five disease-causing mutant alleles were found in a recent study that identified TTLL5 as a disease gene for human retinal dystrophy (33). We examined three of these disease mutations and demonstrate that two reduce TTLL5 glutamylase activity to near background levels. Three alleles prematurely truncate the TTLL glutamylase catalytic core (including E543* examined in this study) and are apparent nulls. One missense mutation affects the TTLL core catalytic domain (E543K) and severely impairs glutamylation activity both toward RPGRORF15, as well as tubulin. The W1118* mutant glutamylates RPGRORF15 efficiently in vitro (Fig. 6), consistent with our domain mapping experiments showing that the TTLL core and CID are required for robust RPGRORF15 glutamylation. Interestingly, the W1118X mutant truncates the receptor interacting domain (RID). These observations indicate that the RID may have a yet unidentified but important role in photoreceptors.

The disease resulting from TTLL5 mutations has prominent cone photoreceptor involvement and is clinically characterized as cone-rod dystrophy or cone dystrophy, although rods are also involved in some of these patients (33). This phenotype would seem somewhat dissimilar to the majority of RP patients with RPGR mutations. However, clinical manifestations of RP are known to be highly variable, and RPGR mutations are also known to cause disease with early cone involvement (6, 8, 45–48). Moreover, it is possible that the greater involvement of cones in TTLL5 patients could be due to a selection bias because the study was initiated on patients diagnosed with cone or cone-rod dystrophies. If so, future genetic screens among patients with typical RP may yet turn up cases that are caused by TTLL5 mutations. Comparison of the Rpgr−/− and Ttll5−/− mouse models revealed several similarities, including early cone involvement and overall long-term disease progression. Therefore, in our view, the Ttll5−/− mouse model phenocopies the Rpgr−/− mice, and the disease in both models can be attributed to a nonfunctional RPGRORF15. Finally our working model does not exclude the possibility that TTLL5 mutations lead to a strongly hypomorphic rather than a null RPGRORF15; RPGRORF15 might be glutamylated at an extremely low level by another enzyme or the nonglutamylated protein may still retain very low levels of function. This scenario would be consistent with patients carrying TTLL5 mutations manifesting a somewhat milder disease than patients with RPGR mutations.

RPGRORF15 appears to be glutamylated at multiple consensus sites along the length of its repetitive region, but seems to be primarily monoglutamylated, i.e., each internal glutamylation site has a single postranslationally added glutamate as opposed to longer glutamate chains. This observation is consistent with the enzymatic properties of TTLL5, which was shown to have higher activity initiating glutamate chains than elongating them (26). Because elongating glutamylases also localize to the cilium, e.g., TTLL6 (49, 50), it is possible that the primarily monoglutamylated RPGR species is a result of a balance between elongating glutamylases and carboxypeptidases (CCPs) that shorten the glutamate chains (31). It is not clear how glutamylation of the repetitive region of RPGRORF15 functionalizes it in photoreceptor cells. The similar phenotypes found in Ttll5−/− and Rpgr−/− mice strongly argue for the critical role of glutamylation for this functionalization. The posttranslational addition of negatively charged glutamates can act as an electrostatic tuner to modulate the binding affinity of the modified protein for interacting partners (28). Such a mechanism has been shown for microtubule associated proteins (27, 29) and is likely relevant for histone chaperones Nap1 (51), which are also known to be glutamylated in vivo. Interestingly, RPGRORF15 function is preserved as long as the protein is still able to be glutamylated, even after substantially lowering glutamate content by shortening the Glu-rich region by a third (Fig. 5), which substantially lowers glutamate content (17, 18). These observations suggest that it is the branched glutamate structure added posttranslationally by TTLL5 that is required for RPGRORF15 function. These branched glutamates could act as signals for the recruitment of key regulatory factors to RPGRORF15. Past attempts at identifying an RPGR interactome used recombinant nonglutamylated forms of RPGRORF15 and proved unproductive. Future studies could benefit from our findings by incorporating glutamylated forms of RPGRORF15 as affinity ligands in search of novel binding partners, which may yield fresh insight into RPGR functions.

Materials and Methods

All animal care and procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees at the National Institutes of Health. Mice were used in accordance with the Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology. Normal human donor eyes were obtained from the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI), in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human tissue. Immunofluorescence staining of RPGR was performed on fresh frozen mouse eyes without prior fixation as prior fixation restricts antibody access to the ciliary transition zone. Retinal sections were than postfixed with 1% formaldehyde for 5 min before continuing with blocking and antibody staining. For yeast two-hybrid protein interaction screen, human RPGRORF15 C-terminal basic domain (BD) was used as bait. Further details are in SI Materials and Methods including experimental procedures and reagents.

SI Materials and Methods

Animals.

The Ttll5−/− mice were described previously (34). For ERG and morphometric analysis of aged mice (20–22 mo), Ttll5+/− and Ttll5+/+ littermates of the null mice were used as controls. For study of the younger mice (postnatal 20 days–4 months), Ttll5+/+ littermates of the null mice were included as controls. Ttll5 study mice were screened to rule out the recessive Crb1rd8 mutation as a cause for degeneration (52, 53). A line of Rpgrip1 KO mice was previously described (43). An RPGR default specific knockout mouse line, in which the ORF15 variant is unaffected, was generated in our laboratory. Mice were maintained in a pathogen-free animal care facility under 12-h light/12-h dark lighting cycle.

Antibodies.

The following primary antibodies were used in this study: GT335 (mouse IgG; Adipogen), polyE (Rabbit, pAb; Adipogen), B3 (mouse IgM; Abcam), 1D5 (mouse IgG1; Synaptic System), α-tubulin (mouse IgG1, clone D1MA; Sigma-Aldrich), human RPGR (Sigma-Aldrich), TAP952 (Millipore), EP1332Y (Millipore), GFP (Roche), S-opsin (raised in chicken against mouse S-opsin sequence CRKPMADESDVSGSQKT), M-opsin (Millipore), Rhodopsin (gift of Robert Molday, University of British Columbia, Vancouver), RPGR S1 (10), GFAP (Dako), and Rootletin (54).

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screen.

Yeast two-hybrid screening was performed using the GAL4 system 3 (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as previously described (22). The retinal cDNA library used in these screens was constructed using poly(A)+RNA from donor retinas. The cDNAs were inserted into the pACT2 plasmid vector downstream from the GAL4-activation domain. Baits were cloned into the pGBKT7 vector. To ensure the high stringency of the screen, 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) was included in the selection media at a final concentration of 15 mM.

AAV Plasmid Constructions and Production of Recombinant RPGR.

The plasmid pV4.7-RK-hRPGR-ORF15 (55) was used to express full-length human RPGRORF15 (RPGR FL). The plasmids pAAV-RK-ORF15-L and pAAV-RK-ORF15-S (17) were used to express RPGR-Δ863–990 and Δ695–1011, respectively. E1078X and G874X are two nonsense point mutations found in human patients (33). To make the AAV vector plasmid containing the E1078X mutant, PCR was performed to generate the DNA fragments using the primers below carrying the point mutation. PCR was performed with PrimeSTAR HS DNA Polymerase (Clontech Laboratories). The PCR conditions were 94 °C for 1 min followed by 30 cycles at 98 °C for 10 s and 72 °C for 80 s, followed by 7 min of extension at 72 °C and hold at 4 °C. The PCR product was subcloned into TOPO TA Vector, sequenced to verify fidelity, and then cut and inserted back to the aforementioned parental plasmid pV4.7-RK-hRPGR-ORF15. To make the vector plasmid containing the G874X mutant, a DNA fragment (sequence shown as below) was synthesized (DNA 2.0). The fragment was digested with BsrBI and XhoI and was inserted into the corresponding location of pV4.7-RK-hRPGR-ORF15. The expression of recombinant protein was driven and regulated by a human rhodopsin kinase (RK) promoter (56). The plasmids were propagated in XL10-Gold bacterial strain (Agilent Technologies). The underlined letters correspond to restriction sites Pst1 and Xho1.

RPGR-Pst1_F 5′-GGAAATGTACTGCAGAGGACTCTATCA-3′

Pst1

RPGR-E1078X_R 5′-GCTGATCACTCGAGTTAATTCTCTTCTTCGCCTGTCTCCT-3′

Xho1 Stop

Sequence of synthesized DNA for G874X construct 5′-GGAGGAAAGAGCGGGAAAGGAGGAAAAGGGGGAAGAAGAGGGTGACCAGGGGGAGGGTGAAGAGGAGGAAACGGAAGGTCGCGGGGAGGAGAAAGAGGAAGGTGGAGAAGTGGAGGGAGGAGAGGTCGAGGAGGGCAAAGGGGAACGGGAAGAAGAGGAAGAGGAGGGGGAAGGCGAAGAAGAAGAAGGGGAAGGGGAGGAGGAAGAGGGAGAGGGTGAGGAGGAGGAGGGAGAAGGAAAGGGAGAAGAGGAGGGGGAGGAAGGAGAGGGCGAGGAGGAGGGCGAAGAGTGACTCGAGAGATCTAATCTC-3′

AAV Vector Packaging.

Triple-plasmid transfection of HEK293 cells was used to produce AAV vectors. The human RPGR-ORF15 AAV constructs were packaged into AAV8. The vectors were purified by polyethylene glycol precipitation followed by cesium chloride density gradient fractionation, as described earlier (55). The purified vectors were formulated in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl and 180 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, and stored at −80 °C before use. Quantification of vectors was done by real-time PCR using linearized plasmid standards.

Subretinal Injections.

AAV vectors were injected subretinally. Briefly, mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (8 mg/kg). Pupils were dilated with topical atropine (1%) and tropicamide (0.5%). Surgery was performed under an ophthalmic surgical microscope. A small incision was made through the cornea adjacent to the limbus using an 18-gauge needle. A 34-gauge blunt needle fitted to a Hamilton syringe was inserted through the incision while avoiding the lens and pushed through the retina. All injections were made subretinally in a location within the nasal quadrant of the retina. Each animal received 1 μL AAV vector at the concentration of 1× 10 12–4 × 10 12 vector genomes/mL. Visualization during injection was aided by addition of fluorescein (100 mg /mL AK-FLUOR; Alcon) to the vector suspensions at 0.1% by volume.

Immunofluorescence.

Mice were euthanized and eyes were enucleated. For unfixed sectioning, eyes were embedded immediately in OCT and frozen in dry ice-cooled isopentane. For fixed eyes, eyes were placed in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde for 10 min; the anterior segment was then removed, and eyecups were returned to 4% paraformaldehyde for 50 min. The eyecup was washed in PBS and cryoprotected in 30% (wt/vol) sucrose before freezing in OCT. Eyes were sectioned vertically at 10 µm using either a cryostat (Thermo Microm HM550) or at 100 µm using a vibratome (Leica VT1000S). Because RPGR can only be stained on unfixed sections, these sections were postfixed in 1% paraformaldehyde and processed according to previous described methods (11). All sections were blocked in 5% (vol/vol) donkey serum diluted in PBS-0.1% Triton X-100 (PBS-Tx). Sections were incubated in primary antibody overnight. Subsequently, sections were washed with PBS-Tx and incubated in secondary antibody for 1–2 h. Fluorescent dye-conjugated secondary antibodies generated in donkey were obtained from Life Technologies (anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG) and Jackson Immunoresearch (anti-chicken IgY and anti-mouse IgM). DAPI was used to stain nuclei. Sections were analyzed using a confocal microscope (Zeiss 700), and images were processed using Adobe Photoshop (CS6, version 13).

Cloning and Recombinant Protein Expression in Cell Culture.

Mouse TTLL5-YFP and its paralogs are gifts from C. Janke, France Paris Sciences et Lettres Research University, Paris (24). TTLL5-YFP was modified by site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent) to produce domain truncation and clinical mutants. The TTLL5 mutants were PCR amplified and subcloned into GFP-tagged pDEST53 (Thermo-Fisher Scientific). All mutant clones were sequence verified. Recombinant expression was visualized by GFP fluorescence. HEK293/TSA201 cells were cotransfected using Fugene (Roche) with RPGRORF15 and the various TTLL5 constructs. Cotransfected HEK293 cells were lysed with 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100 with Protease Inhibitor Mixture (Roche) >24 h after transfection, and cellular debris were removed by centrifugation. GFP Trap (ChromoTek) was used per manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunoblotting Analysis.

Eyes were collected and placed on ice from mice at ages indicated in figure legends. Neuronal retinas were dissected out in a physiological buffer and transferred and homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer containing proteinase inhibitor. The tissue debris was removed by a brief centrifugation. Alternatively, retinal proteins were isolated using TRIZOL reagent according the manufacturer’s Instruction (Invitrogen). Retinal protein was separated on 5%, 7.5%, or 4–15% (wt/vol) SDS/PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. After preadsorption with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature, the membrane blots were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody. The blots were then washed with Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBS-T: 137 mM sodium chloride, 20 mM Tris, and 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.6), incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the secondary antibody HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch), developed by chemiluminescence detection (SuperSignal West Pico, Dura or Femto Chemiluminescent; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and imaged using a digital camera (FluorChem; ProteinSimple). Mouse monoclonal anti–β-actin antibody or anti–γ-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for loading controls. For analysis of recombinant proteins expressed in cell culture, immunoblotting was performed using near-infrared fluorescence per manufacturer’s instructions (LI-COR).

Transmission Electron Microscopy, Histology, and Morphometric Analysis.

For light microscopy, enucleated eyes were fixed for 10 min in 1% formaldehyde and 2.5% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH7.5). Following removal of the anterior segments and lenses, the eyecups were left in the same fixative at 4 °C overnight. Eyecups were washed with buffer, postfixed in osmium tetroxide, dehydrated through a graded alcohol series, and embedded in Epon. Semithin sections (1 µm) were cut for light microscopy observations. For EM, ultrathin sections were stained in uranyl acetate and lead citrate before viewing on a JEOL JEM-1010 electron microscope. For morphometric analysis, images of retinal cross sections were created by tiling multiple 10× brightfield images of stained sections. Tiled digital images were opened in ImageJ (National Institutes of Health), distance was calibrated using the scale bar, and segmental distances from the ONH created along the entire length of the retina with ONL thickness measured at each location. Measurements were made along a single retina section for each mouse (n = 9 control and 11 Ttll5−/− age-matched mice), and measured values were transferred to Graphpad Prism to generate graphs and perform statistical analyses. Error bars indicate SEM, and comparisons between control and Ttll5−/− mice were made using unpaired t tests, with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Fundus Imaging.

Mice were anesthetized by ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (8 mg/kg) and subjected to pupillary dilation with tropicamide (0.5%; Bausch & Lomb) and phenylephrine hydrochloride [2.5% (wt/vol); Paragon BioTek]. Fundi were photographed using the Μm III Rodent Fundus Imaging System (Phoenix Research Labs) with a drop of hypromellose solution [2.5% (wt/vol) Gonak; Akorn] for corneal hydration.

Electroretinographic Analysis.

Mice were dark-adapted overnight and prepared for recording in darkness under dim-red illumination. Mouse pupils were dilated by topical administration of tropicamide (1%; Alcon) and phenylephrine [2.5% (wt/vol); Alcon]; proparacaine hydrochloride (0.5%; Alcon) was applied for topical anesthesia. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) by i.p. injection of 0.1 mL/10 g body weight of anesthetic solution (1 mL of 100 mg/mL ketamine and 0.1 mL of 100 mg/mL xylazine in 8.9 mL PBS). Body temperature was maintained at 37 °C on a heating platform. Gonioscopic Prism solution [2.5% (wt/vol) Hypomellose Ophthalmic Demulcent solution; Alcon] was applied to each eye, and gold wire loop electrodes were placed on corneas, with the reference electrode was placed in the mouth and the ground subdermal electrode at the tail. Flash ERGs recordings were recorded simultaneously from both eyes using an Espion E2 Visual Electrophysiological System (Diagnosys). Rod and mixed rod-cone ERG responses were recorded at increasing light intensities over the ranges of 0.0001–10 cd⋅s/m2 under dark-adapted conditions. The stimulus interval between flashes varied from 5 s at the lowest stimulus strengths to 60 s at the highest ones. Two to 10 responses were averaged depending on flash intensity. Then the mouse was light adapted for photopic responses for at least 2 min in the Ganzfeld dome. Recordings were carried out at light intensities over 0.3–100 cd⋅s/m2 under a background light that saturates rod function. Twenty to 30 responses were averaged. ERG signals were sampled at 1,000 Hz and recorded with 0.3-Hz low-frequency and 300-Hz high-frequency cutoffs. The a-wave amplitude was measured from the baseline to the negative peak, and the b-wave was measured from the a-wave trough to the maximum positive peak. To compare ERG data between groups at each intensity point, we first averaged the ERG amplitude data for the two eyes of each mouse and then averaged the data for all mice within a single group (e.g., genotype). Unpaired two-tailed t tests were used to analyze the data, and P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Data analysis and graphing were done using statistical software (GraphPad Prism Software; Version 6.0f). A regular two-way ANOVA was performed with the two factors of genotype and light stimulus intensity. In all graphical representations, the error bars indicate SEM.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Stoney Simons, Jr. (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases) for transferring the Ttll5−/− mice to A.R.-M., Dr. Robert Fariss [National Eye Institute (NEI)] for help with confocal microscopy, Dr. Mones Abu-Asab (NEI) for help with TEM, Dr. Suresh Sharma (NEI) for advice on statistics, Suja Hiriyanna (NEI) and Dr. Wenhan Yu (NEI) for AAV vector production, Yide Mi (NEI) for colony management, Megan Kopera (NEI) and Hideko Takahashi (NEI) for rederivation of Ttll5 mice to the C57BL/6J background, Drs. Heather Narver and Brian Wilgenburg [National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)] for veterinarian service and Ttll5 mouse colony management, and Arturo Rivera (NEI) for help with genotyping. This work was supported by the intramural programs of the NEI and NINDS (to T.L. and A.R.-M., respectively).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1523201113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Berson EL. Retinitis pigmentosa. The Friedenwald Lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34(5):1659–1676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bader I, et al. X-linked retinitis pigmentosa: RPGR mutations in most families with definite X linkage and clustering of mutations in a short sequence stretch of exon ORF15. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(4):1458–1463. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pelletier V, et al. Comprehensive survey of mutations in RP2 and RPGR in patients affected with distinct retinal dystrophies: Genotype-phenotype correlations and impact on genetic counseling. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(1):81–91. doi: 10.1002/humu.20417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branham K, et al. Mutations in RPGR and RP2 account for 15% of males with simplex retinal degenerative disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(13):8232–8237. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Churchill JD, et al. Mutations in the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa genes RPGR and RP2 found in 8.5% of families with a provisional diagnosis of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(2):1411–1416. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandberg MA, Rosner B, Weigel-DiFranco C, Dryja TP, Berson EL. Disease course of patients with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa due to RPGR gene mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(3):1298–1304. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Megaw RD, Soares DC, Wright AF. RPGR: Its role in photoreceptor physiology, human disease, and future therapies. Exp Eye Res. 2015;138:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vervoort R, et al. Mutational hot spot within a new RPGR exon in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 2000;25(4):462–466. doi: 10.1038/78182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan D, et al. Biochemical characterization and subcellular localization of the mouse retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (mRpgr) J Biol Chem. 1998;273(31):19656–19663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong DH, et al. RPGR isoforms in photoreceptor connecting cilia and the transitional zone of motile cilia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(6):2413–2421. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong DH, et al. A retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR)-deficient mouse model for X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP3) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(7):3649–3654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060037497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vervoort R, Wright AF. Mutations of RPGR in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP3) Hum Mutat. 2002;19(5):486–500. doi: 10.1002/humu.10057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breuer DK, et al. A comprehensive mutation analysis of RP2 and RPGR in a North American cohort of families with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70(6):1545–1554. doi: 10.1086/340848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharon D, Sandberg MA, Rabe VW, Stillberger M, Dryja TP, Berson EL. RP2 and RPGR mutations and clinical correlations in patients with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73(5):1131–1146. doi: 10.1086/379379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobi FK, Karra D, Broghammer M, Blin N, Pusch CM. Mutational risk in highly repetitive exon ORF15 of the RPGR multidisease gene is not associated with haplotype background. Int J Mol Med. 2005;16(6):1175–1178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karra D, Jacobi FK, Broghammer M, Blin N, Pusch CM. Population haplotypes of exon ORF15 of the retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator gene in Germany : Implications for screening for inherited retinal disorders. Mol Diagn Ther. 2006;10(2):115–123. doi: 10.1007/BF03256451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pawlyk BS, et al. Photoreceptor rescue by an abbreviated human RPGR gene in a murine model of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Gene Ther. 2016;23(2):196–204. doi: 10.1038/gt.2015.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong DH, Pawlyk BS, Adamian M, Sandberg MA, Li T. A single, abbreviated RPGR-ORF15 variant reconstitutes RPGR function in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(2):435–441. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng WT, et al. Stability and safety of an AAV vector for treating RPGR-ORF15 X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Gene Ther. 2015;26(9):593–602. doi: 10.1089/hum.2015.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson DA, et al. Rd9 is a naturally occurring mouse model of a common form of retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations in RPGR-ORF15. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e35865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong DH, Li T. Complex expression pattern of RPGR reveals a role for purine-rich exonic splicing enhancers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(11):3373–3382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong DH, Yue G, Adamian M, Li T. Retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGRr)-interacting protein is stably associated with the photoreceptor ciliary axoneme and anchors RPGR to the connecting cilium. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(15):12091–12099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song Y, Brady ST. Post-translational modifications of tubulin: Pathways to functional diversity of microtubules. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25(3):125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janke C, Rogowski K, van Dijk J. Polyglutamylation: A fine-regulator of protein function? ‘Protein Modifications: beyond the usual suspects’ review series. EMBO Rep. 2008;9(7):636–641. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garnham CP, Roll-Mecak A. The chemical complexity of cellular microtubules: Tubulin post-translational modification enzymes and their roles in tuning microtubule functions. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2012;69(7):442–463. doi: 10.1002/cm.21027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Dijk J, et al. A targeted multienzyme mechanism for selective microtubule polyglutamylation. Mol Cell. 2007;26(3):437–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonnet C, et al. Differential binding regulation of microtubule-associated proteins MAP1A, MAP1B, and MAP2 by tubulin polyglutamylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(16):12839–12848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roll-Mecak A. Intrinsically disordered tubulin tails: Complex tuners of microtubule functions? Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;37:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valenstein ML, Roll-Mecak A. Graded control of microtubule severing by tubulin glutamylation. Cell. 2016;164(5):911–921. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikegami K, et al. Loss of alpha-tubulin polyglutamylation in ROSA22 mice is associated with abnormal targeting of KIF1A and modulated synaptic function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(9):3213–3218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611547104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogowski K, et al. A family of protein-deglutamylating enzymes associated with neurodegeneration. Cell. 2010;143(4):564–578. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikegami K, Sato S, Nakamura K, Ostrowski LE, Setou M. Tubulin polyglutamylation is essential for airway ciliary function through the regulation of beating asymmetry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(23):10490–10495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002128107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sergouniotis PI, et al. UCL-Exomes Consortium Biallelic variants in TTLL5, encoding a tubulin glutamylase, cause retinal dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94(5):760–769. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee GS, et al. Disruption of Ttll5/stamp gene (tubulin tyrosine ligase-like protein 5/SRC-1 and TIF2-associated modulatory protein gene) in male mice causes sperm malformation and infertility. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(21):15167–15180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.453936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolff A, et al. Distribution of glutamylated alpha and beta-tubulin in mouse tissues using a specific monoclonal antibody, GT335. Eur J Cell Biol. 1992;59(2):425–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gagnon C, et al. The polyglutamylated lateral chain of alpha-tubulin plays a key role in flagellar motility. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 6):1545–1553. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kann ML, Soues S, Levilliers N, Fouquet JP. Glutamylated tubulin: Diversity of expression and distribution of isoforms. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2003;55(1):14–25. doi: 10.1002/cm.10107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magiera MM, Janke C. Investigating tubulin posttranslational modifications with specific antibodies. Methods Cell Biol. 2013;115:247–267. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407757-7.00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rüdiger AH, Rüdiger M, Wehland J, Weber K. Monoclonal antibody ID5: Epitope characterization and minimal requirements for the recognition of polyglutamylated alpha- and beta-tubulin. Eur J Cell Biol. 1999;78(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0171-9335(99)80003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Dijk J, et al. Polyglutamylation is a post-translational modification with a broad range of substrates. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(7):3915–3922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Onikubo T, et al. 2015. Developmentally regulated post-translational modification of nucleoplasmin controls histone sequestration and deposition [published online ahead of print March 11, 2015]. Cell Rep doi:10.1016/j.cetrep.2015.02.038.

- 42.Shu X, et al. RPGR ORF15 isoform co-localizes with RPGRIP1 at centrioles and basal bodies and interacts with nucleophosmin. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(9):1183–1197. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Y, et al. The retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR)- interacting protein: Subserving RPGR function and participating in disk morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(7):3965–3970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0637349100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garnham CP, et al. Multivalent microtubule recognition by tubulin tyrosine ligase-like family glutamylases. Cell. 2015;161(5):1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zahid S, et al. Phenotypic conservation in patients with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa caused by RPGR mutations. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(8):1016–1025. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ebenezer ND, et al. Identification of novel RPGR ORF15 mutations in X-linked progressive cone-rod dystrophy (XLCORD) families. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(6):1891–1898. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Z, et al. Mutations in the RPGR gene cause X-linked cone dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(5):605–611. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thiadens AA, et al. Clinical course of cone dystrophy caused by mutations in the RPGR gene. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249(10):1527–1535. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1789-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JE, et al. CEP41 is mutated in Joubert syndrome and is required for tubulin glutamylation at the cilium. Nat Genet. 2012;44(2):193–199. doi: 10.1038/ng.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pathak N, Austin CA, Drummond IA. Tubulin tyrosine ligase-like genes ttll3 and ttll6 maintain zebrafish cilia structure and motility. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(13):11685–11695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.209817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller KE, Heald R. Glutamylation of Nap1 modulates histone H1 dynamics and chromosome condensation in Xenopus. J Cell Biol. 2015;209(2):211–220. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201412097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mehalow AK, et al. CRB1 is essential for external limiting membrane integrity and photoreceptor morphogenesis in the mammalian retina. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(17):2179–2189. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mattapallil MJ, et al. The Rd8 mutation of the Crb1 gene is present in vendor lines of C57BL/6N mice and embryonic stem cells, and confounds ocular induced mutant phenotypes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(6):2921–2927. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang J, et al. Rootletin, a novel coiled-coil protein, is a structural component of the ciliary rootlet. J Cell Biol. 2002;159(3):431–440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu Z, et al. A long-term efficacy study of gene replacement therapy for RPGR-associated retinal degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(14):3956–3970. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khani SC, et al. AAV-mediated expression targeting of rod and cone photoreceptors with a human rhodopsin kinase promoter. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(9):3954–3961. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]