Abstract

Background

Few previous studies have investigated the association between the severity of an infectious disease and the length of incubation period.

Methods

We estimated the association between the length of the incubation period and the severity of infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, using data from the epidemic in 2003 in Hong Kong.

Results

We estimated the incubation period of SARS based on a subset of patients with available data on exposure periods and a separate subset of patients in a putative common source outbreak, and we found significant associations between shorter incubation period and greater severity in both groups after adjusting for potential confounders.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that patients with a shorter incubation period proceeded to have more severe disease. Further studies are needed to investigate potential biological mechanisms for this association.

INTRODUCTION

The incubation period of an infectious disease is the time from infection to onset of disease. Estimation of the incubation period of a novel pathogen can be vital for prevention and control, for example in order to determine appropriate duration of quarantine or observation of exposed persons.1 In 2002–03, there was an epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused by a novel coronavirus with more than 8,000 cases worldwide, mainly in Asia. The mean incubation period was rapidly estimated during the outbreak to be around 6.4 days,2 and subsequent studies estimated a slightly shorter mean incubation period of around 4.0–5.3 days.3–6 Estimation of the incubation period of a pathogen such as the SARS coronavirus can be complicated because infection events cannot be directly observed and exposure data are consequently interval-censored.7

The incubation period is thought to be a function of the initial infective dose, the speed of replication of the pathogen within the host, and within-host defense mechanisms.1 Few previous studies have investigated the hypothesis that the incubation period might be correlated with the severity of disease, although some studies have examined the correlation between infecting dose and severity of disease.8,9 Here, we analyze the association between the length of the incubation period and the severity of SARS using data from the 2003 outbreak in Hong Kong.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Sources of Data

Information on all 1755 probable cases of SARS coronavirus infection were recorded in an electronic database extracted from a secure web-based data repository containing clinical and epidemiological data on all probable SARS cases admitted to hospitals in Hong Kong throughout the entire epidemic between February and July 2003.10 Further details of the definition of a probable case of SARS and the database are reported elsewhere.10,11 In a subset of cases, information was available on dates of exposure to infection, and in the majority of cases this was recorded as intervals of 2 or more days during which infection may have occurred rather than exact dates of infection.2,6,7,10 We also analysed a separate subset of cases who were residents of the Amoy Gardens housing estate where a potential super-spreading event occurred in March 2003.12–14 For these patients, we removed the small proportion of cases with onset dates prior to the main outbreak and with onset dates >14 days after the start of the main outbreak (eAppendix).

Statistical Analysis

A simple approach to estimate the incubation distribution from interval-censored data is to impute the midpoint of the exposure interval for each patient, and then estimate the distribution based on these ‘exact’ incubation times.5,15 However, this approach is somewhat naïve, and is likely to overestimate incubation distributions which tend to be right-skewed.3

For the subset of cases with exposure dates, two approaches were used to estimate the incubation period distribution. First, we used a non-parametric estimator of the survival function that is a generalization of the Kaplan-Meier estimator for interval-censored data.16 Second, we fitted a lognormal distribution1,6,7,17 allowing for interval censoring, estimating the location and scale parameters (μ and σ) using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) in a Bayesian framework.

To evaluate the association between the incubation period and the severity of disease, we first estimated the difference in mean incubation period between fatal and non-fatal cases in a Bayesian framework. However this analysis could not account for a potential confounding factor such as age which is known to be associated with the duration of the incubation period5,6 and with the severity of disease.10 We therefore specified a multivariable logistic regression model where death was the binary response variable and predictors included age, sex, occupation, and the incubation time Ti of each patient. We performed this with Ti resampled from the 10,000 posterior samples in each MCMC iteration. For the Amoy Gardens subset, we first estimated the potential date of infection for all cases by comparing the epidemic curve with the lognormal incubation period distribution estimated above, and then included in a similar logistic regression model.

In each of the analyses, we specified flat priors for each parameter, and drew 10,000 samples from the posterior distributions after a burn-in of 5,000 iterations. Further technical details of the statistical methods are provided in the eAppendix. All analyses presented here were conducted using R version 3.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Among the 1755 probable cases of SARS in Hong Kong, 302 (17%) patients died.10 The mean age was 44 years, the proportion of healthcare workers was 23% and cases that died were older and more likely to be male and not healthcare workers (Table 1). Among the 1755 cases, we identified 234 cases with an exposure period contained within the interval 0 to 20 days and 308 cases in the “Amoy Gardens” subset with an onset date within the interval 0 to 14 days (eAppendix). Both subsets had similar characteristics to the 1755 cases with fatal outcomes in 25/234 (11%) of the patients with exposure data and 38/308 (12%) in the Amoy Gardens subset (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of SARS patients

| Patient characteristics | Fatal cases | Non-fatal cases | Overall | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cases | ||||

| Sample size, n (%) | 302 (17%) | 1453 (83%) | 1755 | – |

| Age (years); mean±SD | 66.6 ± 17.3 | 38.7 ± 17.3 | 43.5 ± 20.2 | <0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 173 (57%) | 604 (42%) | 777 (44%) | <0.001 |

| Healthcare worker, n (%) | 129 (43%) | 276 (19%) | 405 (23%) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Cases with exposure data | ||||

| Sample size, n (%) | 25 (11%) | 209 (89%) | 234 | – |

| Age (years); mean±SD | 57.8 ± 14.7 | 40.1 ± 14.1 | 42.0 ± 15.2 | <0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 14 (56%) | 99 (47%) | 113 (48%) | 0.546 |

| Healthcare worker, n (%) | 3 (12%) | 54 (26%) | 57 (24%) | 0.202 |

|

| ||||

| Amoy Gardens cases | ||||

| Sample size, n (%) | 38 (12%) | 270 (88%) | 308 | – |

| Age (years); mean±SD | 48.4 ± 12.0 | 33.1± 14.1 | 35.0 ± 14.7 | <0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 22 (58%) | 108 (40%) | 130 (42%) | 0.055 |

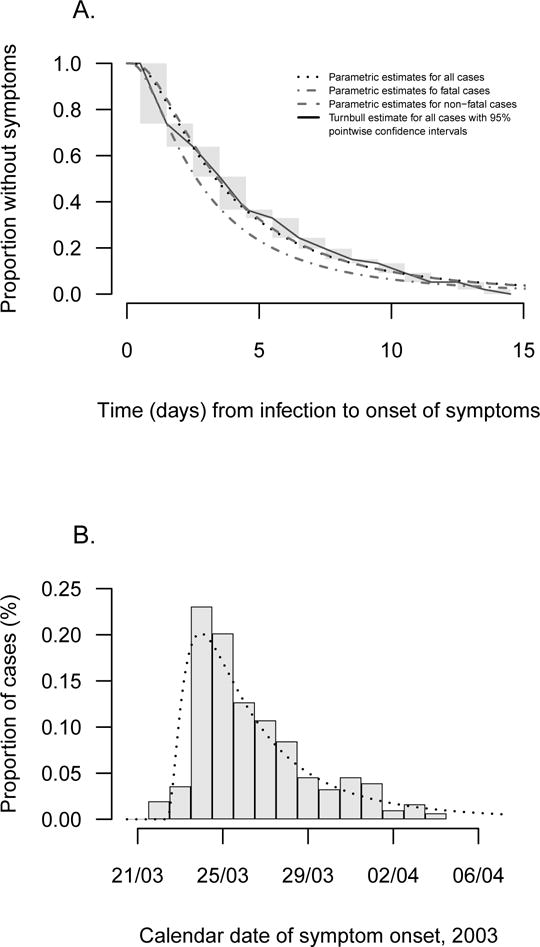

Parametric and nonparametric estimates of the incubation period distribution are presented in Figure 1A and show close agreement. We found a shorter incubation period for the fatal cases with a mean of 3.7 days (95% credibility interval, CrI: 2.6, 5.8), compared with a mean of 4.8 days (95% CrI: 4.2, 5.5) for the non-fatal cases, and a difference in means of 1.02 days (95% CrI: −0.41, 2.22) which was not significant.

Figure 1.

Panel (a): Parametric (dotted line) and non-parametric (solid line) estimates of the incubation distribution for SARS cases with available data on exposure times (n=234). The incubation distribution estimated with a lognormal model (dotted line) gives a mean incubation time of 4.7 days (95% credibility interval, CrI: 4.1–5.4 days) and a standard deviation of 4.6 days (95% CrI: 3.6–6.0 days) respectively. The non-parametric estimate of the incubation distribution is represented by a solid line, and gray rectangles show intervals where the nonparametric maximum likelihood estimate was not unique. Panel (b): Distribution of illness onset dates for SARS cases in the Amoy Gardens cluster (n=308). For this subset of patients, we hypothesized that all the cases were infected on 21 March 2003, and the epidemic curve is consistent with the lognormal incubation period distribution estimated on the separate subset of cases with exposure data as shown in panel A (i.e. mean 4.7 days, standard deviation 4.6 days).

The epidemic curve in the Amoy Gardens outbreak followed a very similar pattern, consistent with an infection event on 21st March 2003 (Figure 1B). Incubation periods for each patient were calculated based on this infection date. In this group, the mean incubation period was significantly shorter in the fatal cases 4.5 days (95% CrI: 3.8, 5.6) than in the non-fatal cases 5.5 days (95% CrI: 5.2, 6.0) with mean difference 1.06 days (95% CrI: 0.16, 1.97) which was significant.

In the multivariable logistic regression model, we found that a shorter incubation period was generally associated with an increased risk of death in both subsets of patients. This association was statistically significant in the analysis of the patients with exposure intervals (OR=0.86; 95% CrI: 0.71, 1.00), and in the Amoy Gardens cluster with an OR=0.79 (95% CrI: 0.67, 0.94) (see also eAppendix).

To examine the sensitivity of our results to inclusion of patients with wide exposure intervals for the cases with exposure data, we also fitted the logistic regression models for a subset of 185 patients with shorter exposure intervals, and found very similar associations of the incubation period with risk of death (eAppendix). In addition, to examine the sensitivity of our results to the assumption of a linear association between incubation time and the log-odds of death, we categorized incubation times into tertiles and found similar results although the effects were only significant in the Amoy Gardens patients (eAppendix).

DISCUSSION

We estimated the incubation period of SARS based on two different subsets of patients, the latter with available data on exposure periods and the former with the hypothesis of a index patient contamination, and compared the length of this period between fatal cases and non-fatal cases to identify a correlation between shorter incubation and greater severity, allowing for potential confounding by age, sex and occupation. Ours is the first study that examines the association between the incubation period and the severity of SARS in the literature to date. It is unlikely that a shorter incubation period itself is the cause of greater severity, but our results indicate that it could be a marker of underlying biological processes that led to greater severity. A shorter incubation period could be indicative of a higher infective dose, leading to faster/greater pathogen replication, out-running adaptive immune responses or leading to a more aggressive and damaging inflammatory response, and thus leading to more severe disease.

An association between severity and a shorter incubation period was suggested by Glynn et al.8 in a study on malaria where a longer incubation period was associated with tertian fever, spontaneous recovery and less use of modifying treatment. Another study on salmonella infection reported a correlation between infecting dose and severity of the infection.9 In a previous study, we showed that healthcare workers, who could have received a higher infecting dose, had a significantly shorter incubation period compared with non-healthcare workers.6 It may also be biologically plausible that a more rapid progression from infection to symptom onset is correlated with more rapid disease progression after onset.

Our study does have some limitations, including a low number of fatal cases having available exposure data that may not be fully representative of all infections. In addition, exposures were self-reported and could be subject to recall bias which was differential and affected by severity, and the cases in the Amoy Gardens cluster may not have all been infected on the same date.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their colleagues in the Hong Kong Department of Health who were involved with the public health control of the SARS epidemic, and data collection and processing.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This study was funded by the Harvard Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant no. U54GM088558), and a commissioned grant from the Health and Medical Research Fund, Food and Health Bureau, Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The funding bodies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to publish.

Footnotes

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

GML has received speaker honoraria from HSBC and CLSA. BJC has received research funding from MedImmune Inc. and Sanofi Pasteur, and consults for Crucell NV. The authors report no other potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nishiura H. Early efforts in modeling the incubation period of infectious diseases with an acute course of illness. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2007;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donnelly CA, Ghani AC, Leung GM, et al. Epidemiological determinants of spread of causal agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1761–1766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13410-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lessler J, Reich NG, Brookmeyer R, Perl TM, Nelson KE, Cummings DAT. Incubation periods of acute respiratory viral infections: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(5):291–300. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70069-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McBryde ES, Gibson G, Pettitt AN, Zhang Y, Zhao B, McElwain DLS. Bayesian modelling of an epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Bull Math Biol. 2006;68(4):889–917. doi: 10.1007/s11538-005-9005-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai Q-C, Xu Q-F, Xu J-M, et al. Refined estimate of the incubation period of severe acute respiratory syndrome and related influencing factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(3):211–216. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowling BJ, Muller MP, Wong IOL, et al. Alternative methods of estimating an incubation distribution: examples from severe acute respiratory syndrome. Epidemiology. 2007;18(2):253–259. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000254660.07942.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farewell VT, Herzberg AM, James KW, Ho LM, Leung GM. SARS incubation and quarantine times: when is an exposed individual known to be disease free? Stat Med. 2005;24(22):3431–3445. doi: 10.1002/sim.2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glynn JR, Bradley DJ. Inoculum size, incubation period and severity of malaria. Analysis of data from malaria therapy records. Parasitology. 1995;110(01):7. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000080999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glynn JR, Bradley DJ. The relationship between infecting dose and severity of disease in reported outbreaks of salmonella infections. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;109(03):371. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800050366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung GM, Hedley AJ, Ho L-M, et al. The epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome in the 2003 Hong Kong epidemic: an analysis of all 1755 patients. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(9):662–673. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-9-200411020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Case Definitions for Surveillance of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) WHO; Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/sars/casedefinition/en/. Accessed October 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y, Duan S, Yu ITS, Wong TW. Multi-zone modeling of probable SARS virus transmission by airflow between flats in Block E, Amoy Gardens. Indoor Air. 2005;15(2):96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu ITS, Li Y, Wong TW, et al. Evidence of airborne transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(17):1731–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu IT-S, Qiu H, Tse LA, Wong TW. Severe acute respiratory syndrome beyond Amoy Gardens: completing the incomplete legacy. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(5):683–686. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Severe acute respiratory syndrome–Singapore, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(18):405–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turnbull BW. The empirical distribution function with arbitrarily grouped, censored and truncated data. J Roy Stat Soc Ser B. 1976;38:290–295. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sartwell PE. The distribution of incubation periods of infectious disease. Am J Hyg. 1950;51(3):310–318. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.