Abstract

Purpose

The present study evaluated the association between oxidative parameters in embryo cryopreservation medium and laboratory and clinical outcomes.

Methods

This prospective laboratory study was conducted in an IVF unit in a university-affiliated hospital with 91 IVF patients undergoing a frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycle. Following thawing, 50 μL of embryo cryopreservation medium was retrieved from each cryotube and tested by the thermochemiluminescence (TCL) assay. TCL amplitudes after 50 (H1), 150 (H2), and 280 s (H3) were recorded in counts per second (CPS) and the TCL ratio determined for comparison with implantation and pregnancy rates.

Results

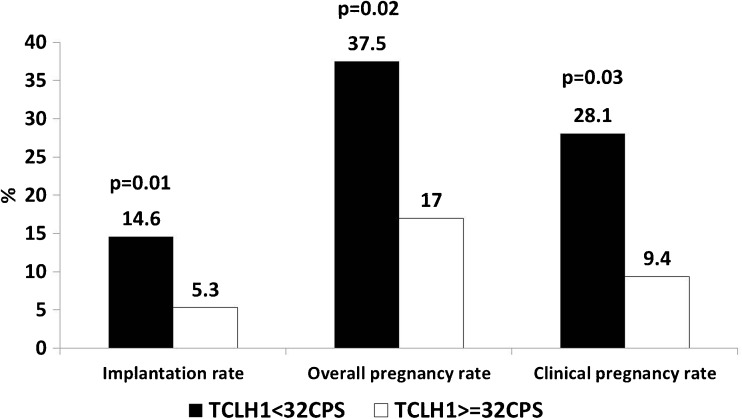

A total of 194 embryos were transferred in 85 frozen-thaw cycles. Twenty-one pregnancies (24.7 %) occurred. Implantation and overall and clinical pregnancy rates were higher when the median TCL H1 amplitude was <32 CPS compared to ≥32 CPS (14.6 vs. 5.3 %, 37.5 vs. 17 %, 28.1 vs. 9.4 %, respectively). No pregnancies occurred when the H1 amplitude was ≥40 CPS. Logistic regression multivariate analysis found that only the median TCL H1 amplitude was associated with the occurrence of pregnancy (OR = 2.93, 95 % CI 1.065–8.08). The TCL ratio inversely correlated with the duration of embryo cryopreservation (r = −0.37).

Conclusions

The results indicate that thawed embryos may express oxidative processes in the cryopreservation medium, and higher oxidative levels are associated with lower implantation rates. These findings may aid in the improved selection of frozen-thawed embryos for IVF.

Keywords: IVF, Embryo, Cryopreservation, Oxidation, Pregnancy

Introduction

Cryopreservation of surplus embryos has been routine practice in IVF laboratories since 1983 [1]. This procedure both reduces the risk of multiple births and prevents the wastage of embryos developed after supraphysiological ovarian stimulation. In addition, the possibility of cryopreserving all embryos and avoiding fresh embryo transfer may prevent the aggravation of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in high-risk IVF cycles [2, 3]. Embryo cryopreservation may also be a successful option for fertility preservation in young women at risk of premature ovarian failure under specific circumstances [4]. Recently, pregnancy and live birth rates for frozen-thawed embryos have approached or surpassed those of fresh embryos [5–7]. Consequently, the emerging trend for elective single embryo transfer in fresh cycles has been extended to frozen-thaw cycles. Due to the increasing tendency to transfer fewer embryos in IVF, embryo selection methods have been the focus of research for the last 10–15 years. The need for more accurate selection criteria than the standard morphological grading system has prompted numerous trials in an attempt to develop non-invasive tools enabling real-time selection of embryos with the best chances of implantation. Time-lapse embryo scoring is a promising tool for improving the selection of embryos for transfer, but this technique involves only fresh embryos [8]. Despite the development of standardized protocols for embryo grading, embryos chosen for transfer following a freeze-thaw cycle are assessed on the basis of a subjective morphological grading and scoring system, which has limitations, including intra- and inter-observer variability [9]. Both cryopreservation and thawing have been associated with post-thaw damage to cells, tissues, and organs via several mechanisms [10]. After incubation and assessment as fresh embryos, frozen-thawed embryos further undergo a process with potential implications for occurrence of implantation. However, these changes are currently assessed only by classical morphological grading and blastomere survival. The thermochemiluminescence (TCL) assay developed in 1994 by Shnizer et al. has been used to investigate oxidative stress in biological fluids [11] and was validated in several studies using various biological samples such as the following: bovine serum albumin, polyunsaturated fatty acids [11], human and rat blood serum [12, 13], human seminal plasma [14], human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, amniotic fluid, follicular fluid [15], and embryo culture media [16].

Heating samples in the TCL Analyzer (Carmel Diagnostics, Kiryat-Tivon, Israel) [11] result in molecular oxidative modification and the formation of electronically excited species (EES) that can be measured as low chemiluminescence in the 350–600nm wavelength range. The TCL kinetic curve pattern reflects the in vitro residual oxidative capacity following in vivo molecular oxidation. The TCL Analyzer is a sensitive, simple, and fast (7 min) method for assessing oxidizability in a given sample of biological fluid. Its convenient size (30 cm × 35 cm × 40 cm) enables its use in an IVF laboratory setup, and sample volumes as small as 10 μL can be analyzed [16]. In a previous study [15], we found an association between oxidative parameters in follicular fluid as measured by the TCL assay, ovarian reserve parameters and the ability to conceive. In another study [16], we found that TCL oxidative parameters in the embryo culture media may serve as quick, simple, and accurate tools for embryo selection in IVF. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the possible association between TCL oxidative parameters in embryo cryopreservation medium and laboratory and clinical parameters of treatment success.

Materials and methods

Ninety-one women undergoing a frozen-thaw embryo transfer cycle in our unit during 2013 participated in this prospective study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Cryopreservation and thawing protocols

Embryo cohorts were cryopreserved according to the slow-freeze protocol in a biological freezer (Planer Kryo II; Planer Products Ltd., Middlesex, England) with a freezing and thawing kit consisting of three freezing and three thawing solutions (Quinns advantage freeze kit; SAGE Trumbull, USA) containing propandiol, sucrose and human albumin in varying proportions. Embryos were frozen in tubes (Cryotubes, Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) containing 0.25 mL of freezing medium. The temperature was decreased from room temperature to −7.5 °C at the rate of −2 °C per minute. After 10 min at this temperature, the tubes were manually seeded. After seeding, the tubes remained at −7.5 °C for another 15 min. The temperature was then dropped to −30 °C at a rate of −0.3 °C per minute. Afterwards, the temperature was further dropped at a rate of −10 °C per minute to −130 °C. At this stage, the tubes were transferred to a canister, which was inserted into liquid nitrogen (−196 °C) until thawing.

For thawing, the cryotubes were removed from the canister and kept at room temperature for 1 min and then inserted into a 37 °C water bath for approximately 1.5 min until completely thawed. At this stage, embryos were removed from the freezing medium and transferred, in decreasing concentrations, to a thawing medium according to the instructions in the SAGE kit. At the end of this process, the embryos were transferred to fresh incubation medium at 37 °C and then transferred to the uterus.

Freeze-thaw embryo transfer protocols

Patients underwent either a natural cycle protocol or a hormonal replacement protocol in order to achieve a receptive endometrium. In the natural cycle protocol, patients with normal ovulatory cycles were serially monitored during the follicular phase for serum estradiol, luteinizing hormone and progesterone levels, and transvaginal sonography (TVS) was performed to determine the number and size of the leading follicles and endometrial thickness until ovulation occurred. When LH surge was observed in the serum, coupled with signs of ovulation by transvaginal sonography, thawing and transferring of embryos was planned according to their developmental stage at freezing [17]. Patients in the natural cycle protocol did not receive any medication in order to induce ovulation. Luteal phase support by the administration of 400 mg of micronized progesterone was administered as a vaginal suppository (Utrogestane, Besins International Laboratories, Paris, France) twice daily to the patients.

In the endometrial preparation protocol, 2 mg of oral estradiol hemihydrate (Estrofem, Novo Nordisk, IS, Denmark) or estradiol valerate (Progynova, Bayer, GmBH and, CO.KG Weimar, Germany) was administered three times a day starting on cycle day 3. Patients were monitored by TVS for endometrial thickness and appearance. When a three-laminar endometrium ≥7 mm was observed, 400 mg of micronized progesterone was administered as a vaginal suppository (Utrogestane, Besins International Laboratories, Paris, France) twice daily. Embryos were thawed and transferred 2 or 3 days after the addition of progesterone depending on embryo age at freezing. After thawing, all surviving embryos in the cryotube were transferred to the uterus. None of the patients received thawed embryos originating from two freezing cohorts (i.e., two different cryotubes); every transfer cycle represents one frozen-thawed embryo cohort. Hormonal support was maintained among both groups until serum BHCG levels were measured, 12 days after embryo transfer. Levels above 5 IU/L were indicative of pregnancy. Clinical pregnancy was defined by the presence of one or more gestational sacs on TVS. If pregnancy occurred, hormonal support was carried on until the ninth gestational week [18]. The implantation rate was defined as the number of gestational sacs demonstrated by sonography divided by the number of transferred embryos per patient in a conception cycle.

Embryo selection for transfer and freezing and embryo scoring after thawing were performed according to standard morphological assessment methods [19]. Briefly, embryos were graded according to three parameters: equality of blastomeres, nuclear fragmentation and cytoplasmic granules. Each parameter was graded as 0, 0.5, or 1. The maximum total score was 3. Embryos were cryopreserved only when the total score was ≥2. Thawed embryos were considered viable and eligible for transfer if ≥50 % of blastomeres survived and the total score was ≥2.

Medium collection for TCL analysis

After removing the embryos from the thawing medium, 50 μL of cryopreservation medium was removed from each cryotube and examined in the TCL Analyzer. Both the embryologists and the physician performing the embryo transfer were blinded to the TCL results. The four TCL parameters recorded were the TCL amplitude after 50 (H1), 150 (H2), and 280 (H3) seconds, expressed in counts per second (CPS) and the TCL ratio. The ratio was calculated as follows:

The slope of the TCL curve expressed by the TCL ratio represents the residual oxidative potential of the examined sample. The TCL H1 amplitude represents the fast oxidation of intermediary oxidative metabolites present in the sample, which begins prior to examination in the TCL Analyzer.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM statistics SPSS22 package for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD or median and range. The categorical variables were presented as percentages. The statistical tests used to examine the difference between two groups were the independent t test or Mann-Whitney test, as appropriate, for the continuous variables. The chi-square test was used for categorical variables. The correlation between two continuous variables was examined using the Pearson or Spearman correlation as appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify the independent factors associated with the occurrence of pregnancy. p < 0.05 was considered significant. In order to calculate an optimal TCL amplitude cut-off, a receiver operator curve (ROC) was plotted.

In our previous work [16] evaluating oxidative parameters in embryo culture media from IVF, the TCL H1 amplitude was the most predictive parameter for treatment success. Therefore, in this study evaluating oxidative parameters in embryo cryopreservation medium, we assumed that the TCL H1 amplitude may also potentially impact treatment outcome. Consequently, the power analysis was calculated according to a possible difference in TCL H1 amplitude of 0.7 standard deviations given a confidence level of 95 % and power of 0.8 among pregnant vs. non-pregnant patients. The study was planned as a 1-year study. Therefore, our sample size considerations were based on the average number of frozen embryo transfer (FET) cycles in our IVF unit annually during recent years. Our unit performs 90–100 FET cycles per year, achieving an average pregnancy rate of 25 %. Based on this data and assuming a 95 % confidence level and power of 80 %, this sample size allows us to find a difference of 0.7 SD (based on independent t test) in TCL HI amplitude between the conception cycles (cycles that resulted in pregnancy) and non-conception cycles.

Results

The patients ranged in age from 20 to 45 years (Table 1). A total of 275 embryos were thawed, 194 of which (70.5 %) were transferred. In six cycles, embryo transfer was canceled due to fragmentation and no survival of post-thaw embryos. The mean number of thawed and transferred embryos per freezing cohort was 2.9 ± 0.9 and 2.1 ± 0.8, respectively. One embryo was transferred in 12 of the 85 transfer cycles (14 %). Twenty-one pregnancies (24.7 %) were achieved. Thirteen resulted in live birth (9 singleton and 4 twin deliveries). Eight pregnancies (38 %) resulted in miscarriage. Demographic, clinical and laboratory data are summarized in Table 1. In the ROC analysis, the median TCL H1 amplitude of 32 CPS was the best cut-off value for discriminating between conception and non-conception cycles. The area under the ROC (AUC) of the TCL H1 median for any pregnancy was 0.62 (95 % CI 0.48–0.76). When ROC was calculated for clinical pregnancies only, the AUC was 0.66 (95 % CI 0.5–0.82). Overall and clinical pregnancy rates obtained from embryos with a TCL H1 amplitude <32 CPS were higher than those achieved from embryos with a TCL H1 amplitude ≥32 CPS (37.5 vs. 17 %, p < 0.03 and 28.1 vs. 9.4 %, p < 0.02, respectively). The mean implantation rate was 8.8 % (95 % CI 3.9–13.7). Similarly, the implantation rate obtained for embryos with a TCL H1 amplitude <32 CPS was higher than those achieved for embryos with a TCL H1 amplitude ≥32 CPS (Fig. 1). In addition, higher pregnancy rates were associated with the transfer of embryos at 2 days (p < 0.093), a greater number of transferred embryos (p < 0.07) and the transfer of embryos with a lower TCL H1 amplitude (p < 0.089) or a TCL H2 amplitude <35 CPS (p < 0.068; Table 1). The areas under the ROC of the median TCL H2 amplitude, TCL H3 amplitude and TCL ratio were 0.58 (95 % CI 0.44–0.72), 0.52 (95 % CI 0.37–0.67), and 0.57 (95 % CI 0.42–0.73), respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data in relation to the occurrence of pregnancy

| Parameter | Total N = 85 | No pregnancy N = 64 | Pregnancy N = 21 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.9 ± 5.6 | 31.98 ± 5.7 | 31.19 ± 5.9 | 0.585 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.277 | |||

| Yes | 12 (14.1 %) | 11 (91.7) | 1 (8.3) | |

| No | 70 (85.4) | 51 (72.9) | 19 (27.1) | |

| Type of infertility, n (%) | 0.649 | |||

| Primary | 36 (42.4) | 28 (77.8.) | 8 (22.2) | |

| Secondary | 49 (57.6) | 36 (73.5) | 13 (26.5) | |

| Diagnosis of infertility, n (%) | 0.945 | |||

| Male | 44 (51.8) | 32 (50.0) | 12 (57.1) | |

| Mechanical factor | 4 (4.7) | 3 (4.7) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Anovulation | 7 (8.2) | 6 (9.4) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Unexplained | 19 (22.3) | 14 (21.9) | 5 (23.8) | |

| Combined | 11 (12.9) | 9 (14.1) | 2 (9.5) | |

| Duration of infertility (years) | 3.59 ± 2.3 | 3.53 ± 2.2 | 3.29 ± 1.9 | 0.691 |

| Basal FSH | 6.35 ± 1.8 | 6.33 ± 2.0 | 6.41 ± 1.62 | 0.859 |

| Endometrium thickness | 8.7 ± 1.5 | 8.67 ± 1.6 | 8.91 ± 1.5 | 0.628 |

| No. of mature oocytes | 8.63 ± 6.0 | 8.59 ± 6.5 | 8.75 ± 4.6 | 0.473 |

| No. of fertilized oocytes | 8.01 ± 4.2 | 8.39 ± 4.6 | 6.80 ± 1.94 | 0.188 |

| No. of cleaving embryos | 6.39 ± 2.8 | 6.55 ± 3.1 | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 0.674 |

| Total no. of frozen embryos | 4.8 ± 2.8 | N = 64 | N = 20 | 0.705 |

| 5.00 ± 3.1 | 4.15 ± 1.5 | |||

| No. of embryos per cryotube | 2.96 ± 0.82 | 2.9 ± 0.83 | 3.02 ± 0.82 | 0.683 |

| Survival rate per cryotube, median (range) | 75 (20–100) | 66 (20–100) | 75 (50–100) | 0.383 |

| Embryo age, n (%) | 0.093* | |||

| 2 days | 56 (65.9) | 39 (69.6) | 17 (30.4) | |

| 3 days | 29 (34.1) | 25 (86.2) | 4 (13.8) | |

| No. of transferred embryos | 2.27 ± 0.73 | 2.2 ± 0.74 | 2.48 ± 0.68 | 0.070* |

| Post-thaw intra-cohort embryo grading (mean) | 2.26 ± 0.38 | 2.23 ± 0.4 | 2.37 ± 0.35 | 0.124 |

| TCL H1 amplitude (CPS) | 32.89 ± 4.9 | 33.38 ± 5.2 | 31.43 ± 3.9 | 0.089* |

| Median TCL H1 amplitude, n (%) | 0.034 | |||

| <32 CPS | 32 (37.6) | 20 (62.5) | 12 (37.5) | |

| ≥32 CPS | 53 (62.4) | 44 (83.0) | 9 (17.0) | |

| TCL H2 amplitude (CPS) | 35.54 ± 4.8 | 35.87 ± 4.9 | 34.52 ± 4.3 | 0.276 |

| Median TCL H2 amplitude, n (%) | 0.068* | |||

| <35 CPS | 38 (44.7) | 25 (65.8) | 13 (34.2) | |

| ≥35 CPS | 47 (55.3) | 39 (83.0) | 8 (17.0) | |

| TCL H3 amplitude (CPS) | 41.0 ± 7.6 | 40.8 ± 6.9 | 41.62 ± 9.5 | 0.787 |

| Median TCL H3 amplitude, n (%) | 0.754 | |||

| <40 CPS | 42 (49.4) | 31 (73.8) | 11 (26.2) | |

| ≥40 CPS | 39 (45.9) | 33 (76.7) | 10 (23.3) | |

| TCL ratio | 126.2 ± 21.0 | 124 ± 17.1 | 132.4 ± 29.6 | 0.318 |

| Median TCL ratio, n (%) | 0.232 | |||

| <126 | 42 (49.4) | 34 (81.0) | 8 (19.0) | |

| ≥126 | 43 (50.6) | 30 (69.8) | 13 (30.2) |

Data are presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise noted

*We examined the effect size of the variables with p < 0.1

Fig. 1.

Comparison of implantation, overall pregnancy, and clinical pregnancy rates in relation to median TCL H1 (32 CPS) amplitude in the cryopreservation medium

Although these results did not reach significance, we have included the variables for which p < 0.1 (i.e., embryo age, number of transferred embryos and median TCL H2 amplitude) as possible confounding factors in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, as well as patient age, which was not associated with the occurrence of pregnancy in our analysis, but according to the existing literature is a major determinant of the chances of conception. No relationship was found between embryo developmental stage at thawing and intra-cohort embryo survival rates (day 2 vs. day 3 embryos: 77.7 ± 21.15 vs. 78.8 ± 22.15 %, p < 0.930). No difference was found in any of the TCL parameters between thawed Day2 and thawed Day3 embryos (TCL H1 amplitude 32.4 vs. 33.3 CPS, p < 0.445; TCL H2 amplitude 35.25 vs. 35.77 CPS, p < 0.623; TCL H3 amplitude 40.76 vs. 40.74 CPS, p < 0.99; TCL ratio 127.4 vs. 122.67, p < 0.301). We also found no difference between these two embryo age groups in regard to embryo or mean patient implantation rate (11.2 vs. 6.8 %, p < 0.343, 11.6 vs. 5.1 %, p < 0.269). The differences between clinical and laboratory parameters between median TCL H1 and TCL H2 amplitudes, which were associated with the occurrence of pregnancy, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic and outcome parameters among embryo cohorts according to median TCL H1 and H2 amplitudes

| Parameter | H1 < 32 N = 32 |

H2 ≥ 32 N = 53 |

p value | H2 < 35 N = 38 |

H2 ≥ 35 N = 47 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.19 ± 4.9 | 32.15 ± 6.2 | 0.456 | 32.74 ± 5.8 | 31.02 ± 5.6 | 0.171 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 3 (10.0) | 9 (17.3) | 0.521 | 4 (10.8) | 8 (17.8) | 0.374 |

| Primary infertility, n (%) | 8 (25.0) | 28 (52.8) | 0.649 | 11 (28.9) | 25 (53.2) | 0.025 |

| Duration of infertility (years) | 3.06 ± 2.2 | 3.72 ± 2.0 | 0.082 | 3.2 ± 2.1 | 3.67 ± 2.1 | 0.194 |

| Basal FSH (IU/L) | 6.22 ± 1.7 | 6.42 ± 2.0 | 0.642 | 2.15 ± 0.3 | 2.28 ± 0.3 | 0.794 |

| Endometrial thickness (mm) | 9.16 ± 1.7 | 8.48 ± 1.4 | 0.115 | 8.96 ± 1.6 | 8.56 ± 1.5 | 0.273 |

| No. of mature oocytes | 8.19 ± 5.7 | 8.9 ± 6.3 | 0.566 | 7.16 ± 5.5 | 9.79 ± 6.2 | 0.037 |

| No. of fertilized oocytes | 7.25 ± 2.6 | 8.48 ± 4.8 | 0.256 | 7.32 ± 2.7 | 8.55 ± 4.9 | 0.251 |

| No. of cleaving embryos | 6.00 ± 2.3 | 6.63 ± 3.1 | 0.535 | 6.3 ± 2.7 | 6.47 ± 3.0 | 0.781 |

| Total no. of frozen embryos | 4.56 ± 2.7 | 4.94 ± 2.9 | 0.705 | 4.57 ± 2.7 | 4.98 ± 2.9 | 0.577 |

| Duration of cryopreservation (months), median (range) | 3.5 (1–84) | 3 (1–168) | 0.185 | 3 (1–168) | 3 (1–72) | 0.146 |

| No. of embryos per cryotube | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.76 | 0.316 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 3.06 ± 0.9 | 0.210 |

| Embryo survival rate per cryotube, mean (range) | 100 (20–100) | 66 (33–100) | 0.149 | 100 (20–100) | 66 (33–100) | 0.343 |

| Embryos aged 2 days, n (%) | 23 (71.9) | 33 (62.3) | 0.365 | 26 (68.4) | 30 (63.8) | 0.657 |

| No. of transferred embryos | 2.38 ± 0.75 | 2.21 ± 0.72 | 0.233 | 2.29 ± 0.77 | 2.26 ± 0.71 | 0.688 |

| Post-thaw embryo grading | 2.37 ± 0.36 | 2.20 ± 0.38 | 0.123 | 2.32 ± 0.4 | 2.21 ± 0.35 | 0.211 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise noted

A stepwise logistic regression multivariate analysis including patient age and all confounding factors associated with the occurrence of pregnancy found that only the median TCL H1 amplitude was associated with the chances of conception (OR = 2.93, 95 % CI 1.065–8.08, p < 0.03, Table 3). The omnibus test of the model was 0.036. When patient age was excluded from the multivariate analysis, the results were the same; only the median TCL H1 amplitude was significantly associated with the occurrence of pregnancy (B = 1.08, OR = 2.93, 95 % CI 1.07–8.08, p < 0.037).

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors affecting pregnancy rates

| Parameter | OR | 95 % CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age | 0.98 | 0.89–1.1 | 0.687 |

| No. of transferred embryos | 1.6 | 0.78–3.25 | 0.200 |

| Embryo age (2 vs. 3 days) | 2.54 | 0.75–8.65 | 0.134 |

| H1 median <32 vs. ≥32 CPS | 2.93 | 1.07–8.08 | 0.037 |

| H2 median <35 vs. ≥35 CPS | 1.41 | 0.33–6.1 | 0.647 |

The stepwise regression revealed that only the median H1 amplitude was a significant factor affecting the chance of conception

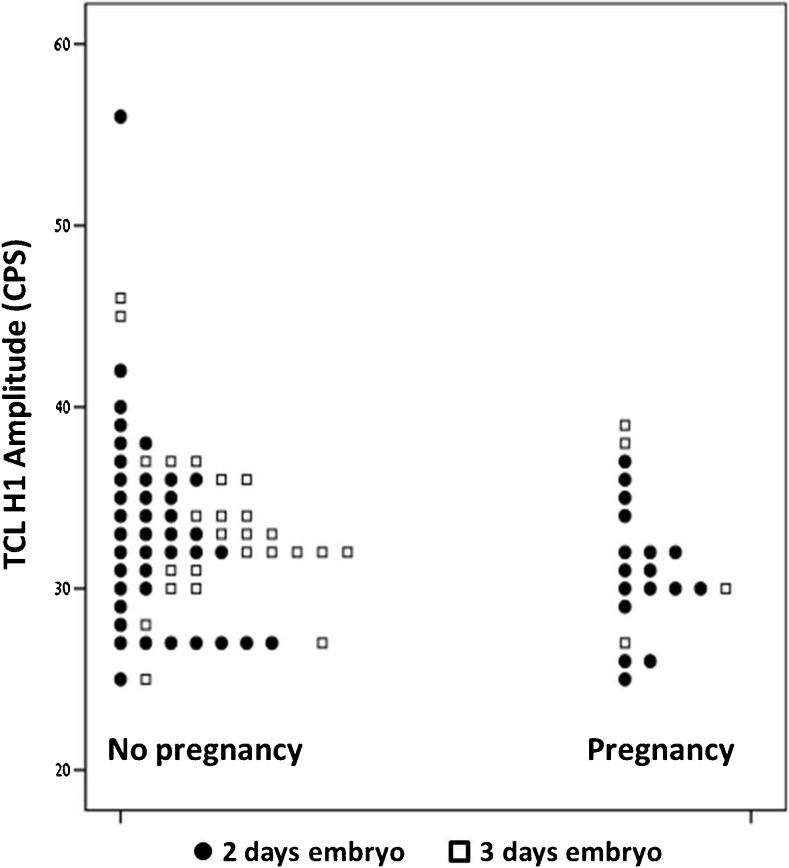

No pregnancies occurred when the TCL H1 amplitude was ≥40 CPS (95 % CI 0–0.52). This was found in five cycles. The distribution of TCL H1 amplitudes in conception vs. non-conception cycles according to embryo age is demonstrated in Fig. 2. Patient age inversely correlated with TCL H3 amplitude (r = −0.25, p < 0.01) and TCL ratio (r = −0.21, p < 0.04). However, no association was found between patient age and the chances of pregnancy.

Fig. 2.

A dot plot describing the distribution of TCL H1 amplitude in conception vs. non-conception cycles according to embryo age (2 vs. 3 days)

Of the 85 patients with embryo transfer, 12 (14.1 %) were smokers. Pregnancy rates were higher among non-smokers than among smokers, but the difference was not significant (27.1 vs. 8.3 %, p < 0.277). The median TCL H3 amplitude was higher among smokers than non-smokers (44 CPS vs. 40 CPS, p < 0.03). The same trend was observed for median TCL H2 amplitude and TCL ratio, though the differences did not reach significance. The TCL ratio inversely correlated with the duration of embryo cryopreservation (r = −0.37, p < 0.0001). Duration did not correlate with the TCL H1, TCL H2, or TCL H3 amplitudes.

Furthermore, no association was found between the number of thawed and transferred embryos in a cohort and any of the TCL parameters: TCL H1, TCL H2, and TCL H3 amplitudes and TCL ratio (thawed embryos r = 0.02, p 0.869; r = 0.13, p = 0.235; r = 0.18, p = 0.103; and r = 0.10, p = 0.344, respectively; transferred embryos r = −0.06, p = 0.584; r = 0.01, p = 0.937; r = 0.02, p = 0.854; and r = 0.16, p = 0.146, respectively). No association was found between the type of infertility (primary/secondary), embryo grading and staging, embryo survival rate in the freezing cohort, and pregnancy rates (Table 1). No differences were found between median TCL H1 amplitude and median TCL H2 amplitude and the number of embryos in the cohort, intra-cohort embryo survival rate (for all embryos and also when embryos were grouped according to the FET cycle, i.e., natural vs. hormonal replacement), or embryo morphological staging and grading (Table 2).

Discussion

In this preliminary study, we demonstrated for the first time that frozen-thawed embryos for IVF express oxidative processes in the cryopreservation medium, and that one of these parameters, the median TCL H1 amplitude, is associated with their ability to implant. We found that higher levels of oxidation, as indicated by the TCL H1 amplitude, in the cryopreservation medium are inversely associated with the chances of conception. In addition, we identified a TCL H1 cut-off value beyond which no pregnancies occurred. However, as a TCL H1 amplitude >40 CPS was found in only five cases, we think it is premature to recommend that frozen-thawed embryos be discarded from transfer if this specific value is measured in the cryopreservation medium. After extending this preliminary study to a larger sample size, it may be possible to find a new cut-off value representing more frozen-thawed embryos that will be able to discriminate between conception and non-conception cycles in a significant manner.

The effects of cryopreservation on biological organs and tissues have been studied extensively. The mechanisms underlying damage caused by the freeze-thaw process include osmotic rupture, intracellular ice formation [20], and oxidative stress [21].

Park et al. described defective antioxidant activity in yeast cells following cryopreservation and demonstrated that post-thaw cellular damage is associated with generation of the oxidant superoxide. They also showed that the damage may be prevented by the addition of antioxidants [22]. Cryopreservation of sperm was associated with low antioxidant status, making them susceptible to oxidative stress and peroxidative damage [23]. In human sperm samples, cryopreservation led to a significant increase in the rate of DNA fragmentation, 8-OHdG (marker of oxidative DNA damage), and apoptosis. The rate of DNA fragmentation correlated with 8-OHdG levels, and the addition of antioxidant to the cryoprotectant had a significant protective effect on the integrity of sperm DNA [24]. Recently, Gale et al. demonstrated increased levels of oxidative stress biomarkers in mussel oocytes following cryopreservation [25]. Other studies demonstrated increased production of reactive oxygen species following cryopreservation of mouse embryos [26] and decreased levels of antioxidant enzymes, such as glutathione reductase, superoxide dismutase, and dehydroascorbate reductase, in frozen maize embryos [27]. These findings are in concordance with the work of Boonkusol et al., who reported the upregulation of two genes associated with oxidative stress (MnSOD and CuSOD) following thawing of mouse embryos [28]. Similarly, Lane et al. showed that the addition of the antioxidant ascorbate to the cryopreservation medium of mouse embryos was beneficial for subsequent embryo development to the blastocyst stage [29]. Recently, Castillo-Martín et al. reported that supplementing culture and vitrification-warming media with ascorbic acid enhanced survival rates and the redox status of porcine blastocysts via induction of GPX1 and SOD1 expression [30]. However, none of these studies addressed embryo implantation. Until now, no studies have been published regarding the mechanisms underlying freeze-thaw damage to human embryos. In the study by Lane et al. [29], it is possible that the oxidative damage to embryos may decrease their developmental potential to reach the blastocyst stage, reducing the chance of implantation.

Although other cycle variables, such as the number of transferred embryos and embryo age, were found to be associated with the chance of conception, a logistic regression multivariate analysis revealed that the median TCL H1 amplitude was the only significant contributor to treatment success. Survival rates and embryo grading were not associated with the occurrence of pregnancy. The latter may be explained by the small sample size or the narrow range of embryo morphological scores, resulting in a limited resolution to accurately differentiate between viable and non-viable embryos.

The process of cryopreservation and subsequent thawing may be a traumatic procedure for the embryo, and the resulting damage may not necessarily be detected by current methods of assessing the quality of frozen-thawed embryos, namely grading and staging by a trained embryologist. Therefore, embryos with a high post-thaw morphological score may not necessarily be those with the highest potential for implantation. Also, the TCL analysis in our study was performed on cryopreservation medium from embryo cohorts and not individual embryos. Therefore, the results do not reflect the implantation potential of single embryos, but rather that of a cohort. However, from a clinical point of view, this may enable us to identify thawed embryo cohorts with a higher implantation potential, as cleavage state frozen-thawed embryos are transferred as a cohort in many IVF units, including ours. Nevertheless, with the increasing tendency towards the elective freezing and transfer of a single frozen-thawed embryo (especially frozen-thawed blastocyst), we aim to extend our study to the FET of a single blastocyst.

In this context, it is interesting to state that no association was found between the number of embryos in a frozen-thawed cohort and TCL parameters.

An interesting finding was the inverse correlation between patient age and TCL ratio and TCL H3 amplitude. The TCL ratio expresses the residual oxidizability of the sample, which is inversely related to the oxidative processes the sample has already undergone prior to the TCL analysis (i.e., a higher TCL curve slope indicates a non-oxidized state of the examined sample, and vice versa). Similar results were found when we examined follicular fluid in the TCL Analyzer [15]. This inverse correlation may reflect the age-related increase in free radical activity [31–34].

Our results regarding the association between smoking and the chance of implantation did not reach significance. This may be due to the small sample size. However, a relationship was found between the women’s smoking status and TCL parameters in the cryopreservation medium. The embryos of smoking patients may undergo more oxidative processes, resulting in higher oxidative levels in the cryopreservation medium. This finding is in line with our previous study assessing TCL oxidative parameters in embryo culture medium [16] and may reflect the maternally derived environmental influence on in vitro cultured embryos. Thus, we speculate that embryos from smoking patients “sense” their mother’s smoking status.

The inverse correlation between the duration of cryopreservation and TCL ratio may represent a time-dependent decline in the residual oxidative capacity of the medium; embryos stored for longer expressed higher levels of oxidation in the cryopreservation medium. This finding may support our assumption that TCL parameters in the cryopreservation medium represent oxidative processes that occur during the freezing period.

Although vitrification is currently our preferred method for embryo cryopreservation, achieving higher survival and pregnancy rates, the study was conducted when most of our embryos were cryopreserved by the slow-freezing method [35]. We are aware of the advantages and recent tendency to cryopreserve all fresh embryos separately as single blastocysts [36], but an updated Cochrane review database [37] revealed that cleavage stage embryos derived from fresh and thaw cycles result in higher clinical pregnancy rates than those from blastocyst cycles. Our clinical pregnancy rates achieved by slow freezing are in line with other studies [38, 39]. Analysis of cleavage-stage thawed embryos is relevant due to the number of stored embryos that are to be thawed and the unsolved dilemma as to the optimal timing of embryo transfer and freezing.

Our results, though preliminary, may shed light on the nature of cryopreservation and thawing-induced embryo damage. They warrant a large-scale prospective study using cryopreservation medium from vitrified embryos, including both cleavage stage and blastocysts, which we are currently being frozen individually. When dealing with the transfer of fresh embryos, extensive effort is being made towards improving our ability to select viable embryos out of a cohort of cleavage embryos or blastocysts (time lapse analysis, gene expression analysis, metabolomics, etc.) [8, 40, 41]. However, selection tools for the transfer of thawed embryos are still based on survival and morphology. As cryopreservation of embryos becomes more and more common in the context of assisted reproductive technologies, we believe that the application of the TCL assay may provide an additional quick, non-invasive, simple, accurate, and objective tool for better embryo selection after thawing, improving treatment outcome.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Footnotes

Capsule

An oxidative parameter in embryo cryopreservation medium as measured by thermochemiluminescence assay was associated with pregnancy in a prospective study. These findings may provide a tool for better embryo selection.

References

- 1.Trounson AO, Mohr L. Human pregnancy following cryopreservation, thawing and transfer of an eight-cell embryo. Nature. 1983;305:707–709. doi: 10.1038/305707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pattinson HA, Hignett M, Dunphy BC, Fleetham JA. Outcome of thaw embryo transfer after cryopreservation of all embryos in patients at risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:1192–1196. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)57184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiener-Megnazi Z, Lahav-Baratz S, Rothschild E, Abramovici H, Dirnfeld M. Impact of cryopreservation and subsequent embryo transfer on the outcome of in vitro fertilization in patients at high risk for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:201–203. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedoschi G, Oktay K. Current approach to fertility preservation by embryo cryopreservation. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1496–1502. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong KM, Mastenbroek S, Repping S. Cryopreservation of human embryos and its contribution to in vitro fertilization success rates. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roque M, Lattes K, Serra S, Solà I, Geber S, Carreras R, Checa MA. Fresh embryo transfer versus frozen embryo transfer in in vitro fertilization cycles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edgar DH, Bourne H, Speirs AL, McBain JC. A quantitative analysis of the impact of cryopreservation on the implantation potential of human early cleavage stage embryos. Hum Reprod. 1999;15:175–179. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemmen JG, Agerholm I, Ziebe S. Kinetic markers of human embryo quality using time-lapse recordings of IVF/ICSI-fertilized oocytes. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;17:385–391. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baxter Bendus AE, Mayer JF, Shipley SK, Catherino WH. Interobserver and intraobserver variation in day 3 embryo grading. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:1608–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao D, Critserl JK. Mechanisms of cryoinjury in living cells. ILAR J. 2000;41:187–196. doi: 10.1093/ilar.41.4.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shnizer S, Kagan T, Lanir A, Maor I, Reznick AZ. Modifications and oxidation of lipids and proteins in human serum detected by thermochemiluminescence. Luminescence. 2003;18:90–96. doi: 10.1002/bio.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman K, Peleg E, Kagan T, Shnizer S, Rosenthal T. Oxidative stress in hypertensive, diabetic and diabetic hypertensive rates. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:1049–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sukhotnik I, Brod V, Lurie M, Rahat MA, Shnizer S, Lahat N, et al. The effect of 100% oxygen on intestinal preservation and recovery following ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1054–1061. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819d0f5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lissak A, Wiener-Megnazi Z, Reznick AZ, Shnizer S, Ishai D, Grach B, et al. Oxidative stress indices in seminal plasma, as measured by thermochemiluminescence assay correlate with sperm parameters. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:792–797. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiener-Megnazi Z, Vardi L, Lissak A, Shnizer S, Reznick AZ, Ishai D, Lahav-Baratz S, Shiloh H, Koifman M, Dirnfeld M. Oxidative stress indices in follicular fluid as measured by thermochemiluminescence (TCL) assay correlate with outcome parameters in IVF. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1171–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiener-Megnazi Z, Shiloh H, Avraham L, Lahav-Baratz S, Koifman M, Reznick AZ, Auslender R, Dirnfeld M. Oxidative parameters of embryo culture media may predict treatment outcome in in vitro fertilization: a novel applicable tool for improving embryo selection. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:979–984. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Shawaf T, Yang D, Al-Magid Y, Seaton A, Iketubosin F, Craft I. Ultrasonic monitoring during replacement of frozen-thawed embryos in natural and hormone replacement cycles. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:2068–2074. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muasher SJ, Kruithoff C, Simonetti S, Oehninger S, Acosta AA, Jones GS. Controlled preparation of the endometrium with exogenous steroids for the transfer of frozen-thawed pre-embryos in patients with anovulatory or irregular cycles. Hum Reprod. 1991;6:443–445. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummins JM, Breen TM, Harrison KL, Shaw JM, Wilson LM, Hennessey JF. A formula for scoring human embryo growth rates in in vitro fertilization: its value in predicting pregnancy and in comparison with visual estimates of embryo quality. J In Vitro Fert Embryo Transf. 1986;3:284–295. doi: 10.1007/BF01133388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muldrew K, McGann LE. The osmotic rupture hypothesis of intracellular freezing injury. Biophys J. 1994;66:532–541. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80806-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vreugdenhil PK, Belzer FO, Southard JH. Effect of cold storage on tissue and cellular glutathione. Cryobiology. 1991;28(2):143–149. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(91)90016-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park JI. The cytoplasmic Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase of Saccharomyces cervisiae is required for resistance to freeze-thaw stress. Generation of free radicals during freezing and thawing. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22921–22928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.22921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chatterjee S, Gagnon C. Evidence for the production of oxygen free radicals during freezing/thawing of bull spermatozoa. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;59:451–458. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomson LK, Fleming SD, Aitken RJ, De Iuliis GN, Zieschang JA, Clark AM. Cryopreservation-induced human sperm DNA damage is predominantly mediated by oxidative stress rather than apoptosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2061–2070. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gale SL, Burritt DJ, Tervit HR, Adams SL, McGowan LT. An investigation of oxidative stress and antioxidant biomarkers during Greenshell mussel (Perna canaliculus) oocyte cryopreservation. Theriogenology. 2014;1(82):779–789. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2014.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahn HJ, Sohn IP, Kwon HC, Jo do H, Park YD, Min CK. Characteristics of the cell membrane fluidity, actin fibers, and mitochondrial dysfunctions of frozen-thawed two-cell mouse embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;61:466–476. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wen B, Wang R, Cheng H, Hong S. Cytological and physiological changes in orthodox maize embryos during cryopreservation. Protoplasma. 2010;239:57–67. doi: 10.1007/s00709-009-0083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boonkusol D, Gal AB, Bodo S, Gorhony B, Kitiyanant Y, Dinnyes A. Gene expression profiles and in vitro development following vitrification of pronuclear and 8-cell stage mouse embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 2006;73:700–708. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane M. Addition of ascorbate during cryopreservation stimulated subsequent embryo development. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2686–2693. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castillo-Martín M, Bonet S, Morató R, Yeste M. Supplementing culture and vitrification-warming media with L-ascorbic acid enhances survival rates and redox status of IVP porcine blastocysts via induction of GPX1 and SOD1 expression. Cryobiology. 2014;68:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol. 1956;2:298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarin JJ. Potential effects of age-associated oxidative stress on mammalian oocytes/embryos. Mol Hum Reprod. 1996;2:717–724. doi: 10.1093/molehr/2.10.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei YH, Lee HC. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial DNA mutation and impairment of antioxidant enzymes in aging. Exp Biol Med. 2002;227:671–682. doi: 10.1177/153537020222700901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sohal RS, Mockett RG, Orr WC. Mechanism of aging: an appraisal of the oxidative stress hypothesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:575–586. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valojerdi MR. Vitrification versus slow freezing gives excellent survival, post warming embryo morphology and pregnancy outcomes for human cleaved embryos. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26:347–354. doi: 10.1007/s10815-009-9318-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Landuyt L, Stoop D, Verheyen G, Verpoest W, Camus M, Van de Velde H, Devroey P, Van den Abbeel E. Outcome of closed blastocyst vitrification in relation to blastocyst quality: evaluation of 759 warming cycles in a single-embryo transfer policy. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:527–534. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glujovsky D, Blake D, Farquhar C, Bardach A. Cleavage stage versus blastocyst stage embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD002118. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002118.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sifer C, Sermondade N, Dupont C, Poncelet C, Cédrin-Durnerin I, Hugues JN, Benzacken B, Levy R. [Outcome of embryo vitrification compared to slow freezing process at early cleavage stages. Report of the first French birth] Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2012;40:158–161. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levron J, Leibovitz O, Brengauz M, Gitman H, Yerushalmi GM, Katorza E, Gat I, Elizur SE. Cryopreservation of day 2–3 embryos by vitrification yields better outcome than slow freezing. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30:202–204. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2013.875995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kropp J, Salih SM, Khatib H. Expression of microRNAs in bovine and human pre-implantation embryo culture media. Front Genet. 2014;24(5):91. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vergouw CG, Heymans MW, Hardarson T, Sfontouris IA, Economou KA, Ahlström A, Rogberg L, Lainas TG, Sakkas D, Kieslinger DC, Kostelijk EH, Hompes PG, Schats R, Lambalk CB. No evidence that embryo selection by near-infrared spectroscopy in addition to morphology is able to improve live birth rates: results from an individual patient data meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:455–461. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]