Abstract

Missing in metastasis (MIM) is abundantly expressed in hematopoietic cells. Here we characterized the impact of MIM deficiency on murine bone marrow (BM) cells. Although MIM-/- cells proliferated similarly to wild type (WT), they exhibited stronger response to chemokine SDF-1, increase in surface expression of CXCR4, impaired CXCR4 internalization and constitutive activation of Rac, Cdc42 and p38. Transplantation of MIM-/- BM cells into lethally irradiated mice showed enhanced homing to BM, which was abolished when mice were pretreated with a p38 antagonist. Interestingly, MIM-/- BM cells, including hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), showed 2 to 5-fold increase in mobilization into the peripheral blood upon treatment with AMD3100. In vitro, MIM-/- leukocytes were susceptible to AMD3100 and maintained increased response to AMD3100 for mobilization even after transfer into wild type mice. MIM-/- mice had also a higher level of SDF-1 in the circulation. Our data highlighted an unprecedented role of MIM in the homoeostasis of BM cells, including HSPCs, through modulation of the CXCR4/SDF-1 axis and interactions of BM leukocytes with their microenvironments.

Keywords: MIM, HSPC, CXCR4, homing, endocytosis, GTPases, MAPKs

INTRODUCTION

Bone marrow provides a confined microenvironment where the pool(s) of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) is maintained, differentiated and amplified to continuously generate the entire lympho-hematopoietic lineage. The molecular basis by which HSPCs and their differentiated progeny reside in and egress out of the BM is largely directed by cellular interactions with BM environmental niches, which express multiple cytokines and chemokines. In particular, chemokine stromal derived factor 1 (SDF-1, also CXCL12) and its receptor CXCR4 play a vital role in homing and mobilization of HSPCs1, 2. The CXCR4 receptor is coupled to heterotrimeric guanosine triphosphate (GTP) and is highly expressed on the surface of HSPCs and many types of leukocytes, while SDF-1 is enriched and secreted by BM stromal cells3. Binding of SDF-1 to CXCR4 triggers a signaling cascade leading to actin cytoskeleton reorganization and activation of integrins for proper interaction with the endothelium of BM sinusoids and stromal cells4, 5. Upon ligand binding, CXCR4 undergoes endocytic trafficking into early endosomes and lysosomes, and subsequent ubiquitination-mediated degradation6. Unlike many other receptors, internalization of CXCR4 is not required for its signaling7. CXCR4 mutants that fail to be internalized often exhibit constitutive activation, which has been proposed to be the etiology of Warts- Hypogammaglobulinemia-Infections and Myelokathexis (WHIM) syndrome8, 9. Similar WHIM- like mutations have also been described recently in Waldernstrom macroglobulinemia10, 11, and may play a key role in the progression of this type of B lymphoid malignancy.

The process of CXCR4 internalization involves the assembly of clathrin-coated pits12, which occurs along with extensive remodeling of membrane curvatures manifested by invagination, tubulation and scission. Dynamics of those membrane curvatures involves the assembly of actin, providing a mechanical force for the membrane movement; and the action of a protein family characterized by sharing a Bin-Amphiphysin-Rvs (BAR) domain, generating initial membrane transformation13-15. The BAR domain is a dimeric motif that binds to phospholipid membranes through a curved interface. Depending on the shape of the interface, BAR domain-containing proteins may facilitate either membrane invagination or membrane extensions. On the basis of the intrinsic property of BAR curvature, members of the BAR family can be further divided into several subfamilies16. While most BAR domains have a positively charged concave surface, the inverse BAR (I-BAR) domains display a convex exterior17, 18, and proteins containing an I-BAR domain tend to deform membranes into protrusive rather than invaginated tubules. The representative for the I-BAR family in hematopoietic cells is MIM (or MTSS1)19, a gene that is frequently abnormally expressed, often downregulated, in a subset of cancerous cells20-22, including leukemia23. We have previously evidenced that MIM knockout (KO) mice displayed abnormal splenomegaly and chronic progression of neoplasms that were originated from B cells19. In addition to leukocytes, abundant MIM has been found in renal epithelial cells, liver, cerebellar Purkinje cells and embryonic cardiomyocytes24, 25. MIM expression in renal cells is upregulated by fluid flow, and MIM-/- mice developed extensive renal tubule dilation, renal cysts26, and reduced integrity of kidney epithelial intercellular junctions27.

Binding of MIM I-BAR peptides to lipid membranes in vitro is sufficient to induce extensive tubule-like membrane protrusions28. Overexpression of MIM in mammalian cells increases the formation of filopodia-like microprotrusions24, 29 and partially inhibits the motility response to growth factors29. It was recently reported that these microprotrusions are structurally and functionally related to dendritic spines that form the postsynaptic component for excitatory synapse30. Although the existing data support an important function of MIM in membrane deformation, the physiological relevance of this property to the homeostasis of leukocytes in vivo has not yet been explored. In the present study, we investigated the role of MIM in HSPC trafficking and found that MIM-/- BM cells have increased cell surface expression of CXCR4 and abnormal trafficking between the peripheral circulation and the BM. Our results suggest that the MIM-mediated CXCR4 internalization contributes to the homeostatic trafficking of leukocytes including HSPCs and we propose a possible link between downregulated MIM expression and hematopoietic malignancies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

WT and MIM-/- mice on the background of C57BL/6J-CD45.2 were bred and maintained in the animal facility at the University of Maryland School of Medicine31. BoyJ mice (B6.SJL-CD45.1) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All the animals were used in accordance with the University of Maryland Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines under approved protocols. Other than ages and strains, animals were randomized selected for analysis. No blinding was used in all the animal studies.

Analysis of homing of BM cell

BM cells were flushed from femurs and tibiae of 6-8 week old WT or MIM-/- mice (CD45.2+). After lysis of red blood cells, BM cells were suspended in 200 μl PBS + 0.5% BSA and injected via tail vein at 5×106/recipient into lethally irradiated (1050 cGy) congenic BoyJ (CD45.1+) mice. 24h later, the injected mice were euthanized, and the number of CD45.2+ donor leukocytes and LSK progenitors present in mouse BM, spleen and PB were measured by flow cytometry. In addition, HSPCs that had homed to the BM were assessed by colony-forming assay.

Statistics

All the data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism 5 for error bars and Student’s t-test (two-sided). P< 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

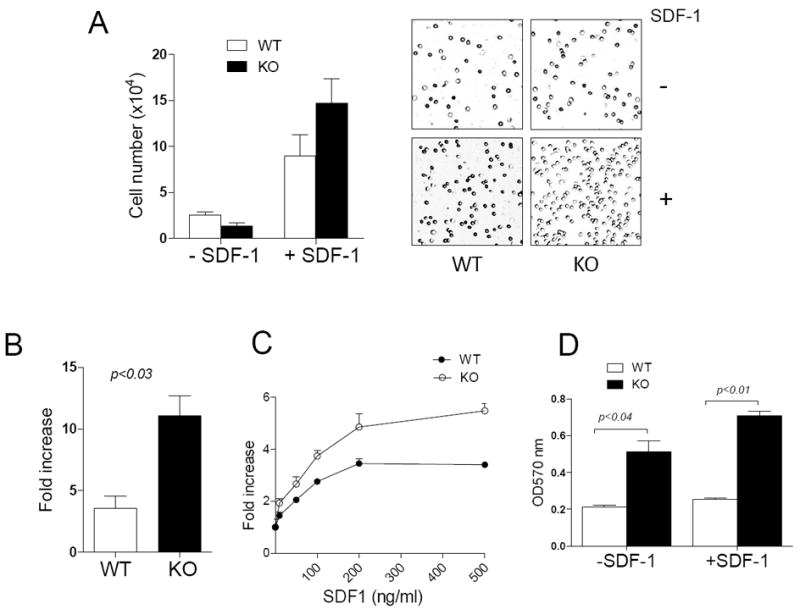

MIM-/- BM cells were hypersensitive to SDF-1

To explore the physiological role of MIM in leukocytes, we examined the chemotactic response of MIM-/- versus WT BM cells to SDF-1, a chemokine that plays a dominant role in the BM niche interactions of leukocytes, including HSPCs5. In the absence of chemoattractants, MIM-/- BM cells had slower mobility than WT cells (Figure 1A). However, MIM-/- BM cells had a significant greater chemotactic response to SDF-1. While SDF-1 stimulation elicited only a maximal 3.5-fold increase in chemotaxis in WT cells, chemotaxis of MIM-/- BM cells increased by as much as a 10-fold in the presence of SDF-1 (Figure 1B and 1C). We also examined the adhesion of BM cells to fibronectin, a major component of BM extracellular matrix and a ligand for α4β14, and found that MIM-/- BM cells had a greater affinity for fibronectin than did WT cells, even in the absence of SDF-1 (Figure 1D). The presence of SDF-1 further enhanced the adhesion of MIM-/- BM cells to fibronectin.

Figure 1. MIM-/- BM cells had a higher motility in response to SDF-1 than did WT cells.

(A) WT and MIM-/- (KO) BM cells were plated in the upper chamber of Transwell plates in the presence or absence of 200 ng/ml SDF-1. After 4h, cells migrated into the lower chamber were counted (left) or photographed using a 10 x objective lens (right). (B, C) The motility of cells toward either 200 ng/ml SDF-1 (B) or SDF-1 at different concentrations (C) was measured as above. The fold increase in the mobility was calculated by normalizing the number of mobilized cells to that measured in the absence of SDF-1. (D) BM cells were plated on 24-well plates pre-coated with 2 μg/ml fibronectin and incubated for 20 min. Attached cells were stained with crystal violet and quantified based on absorption at OD570nm. All the data represent mean ± SEM (n=3).

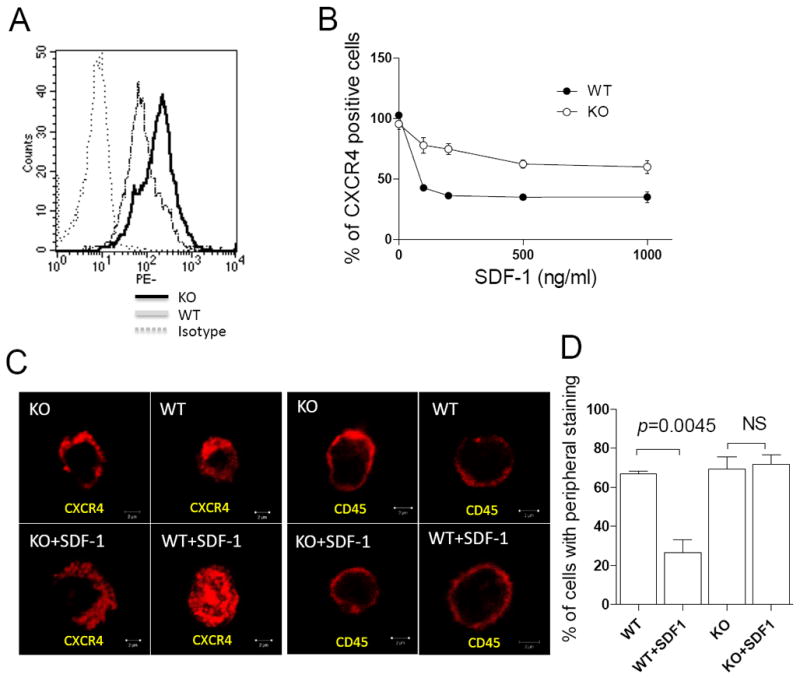

The observed hypersensitivity to SDF-1 suggests that MIM-/- BM cells may have increased expression of CXCR4, the primary receptor for SDF-1. While real-time RT-PCR analysis did not reveal a significant difference in CXCR4 gene expression in MIM-/- cells at the mRNA level (data not shown), flow cytometry detected nearly 2-fold higher CXCR4 on the surface of MIM-/- BM cells compared with WT cells (Figure 2A). Because BAR proteins are commonly involved in endocytosis32, we measured surface CXCR4 upon exposure to a range of doses of SDF-1. While CXCR4 on the surface of WT BM cells was reduced by as much as 65% in 10 min at saturated concentrations of SDF-1, the majority of CXCR4 (nearly 60%) remained on the surface of MIM-/- BM cells under the same conditions (Figure 2B). Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that CXCR4 was distributed primarily on the peripheral area of BM-derived mononuclear cells (MNCs) either from MIM-/- or WT mice in the absence of SDF-1 (Figure 2C). After exposure to SDF-1 for 15 min, CXCR4 accumulated in the cytoplasm of WT cells but remained in the peripheral area of most MIM-/- cells under the same condition (Figure 2C and 2D). As a control, cells were stained with antibody against CD45, a membrane protein that does not interact with SDF-1. No change in CD45 distribution was observed before and after SDF-1 treatment (Figure 2C), indicating that the observed increase in the cytoplasmic CXCR4 staining with WT cells is specific for SDF-1 stimulation. Taken together, these data imply that the lack of MIM impaired the SDF-1-mediated endocytosis of CXCR4, which may cause a relative increase in CXCR4 expression on the cell surface.

Figure 2. MIM-/- cells had increased in expression of CXCR4 on the surface.

(A) Freshly isolated BM cells were stained by PE-CXCR4 antibody and subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) BM cells were treated with SDF-1 for 10 min at concentrations as indicated, and then analyzed by flow cytometry for the surface expression of CXCR4. All the data represent mean ± SEM (n=3). (C) BM MNCs were stained with antibody against either CXCR4 or CD45 with or without SDF-1 treatment and examined by confocal microscopy. Bar, 2 μm. (D) Quantification of BM MNCs that showed CXCR4 staining mainly at peripheral areas.

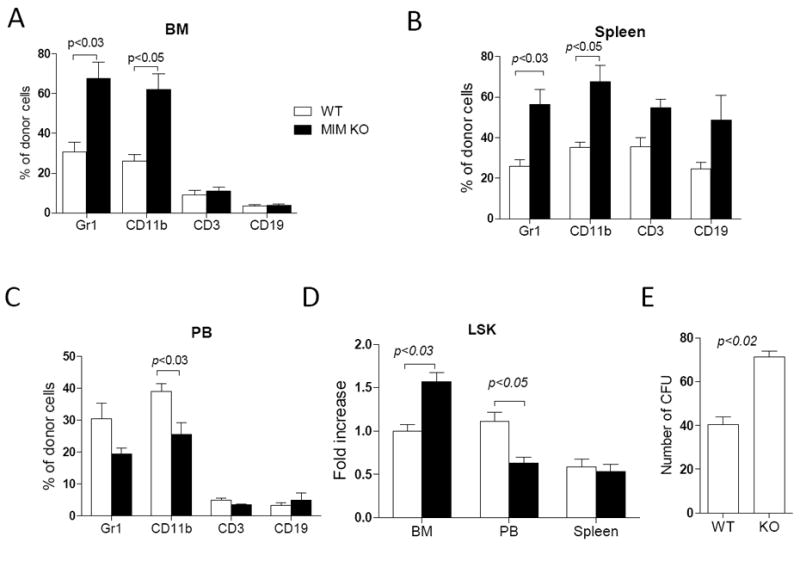

MIM-/- BM cells had increased homing efficiency in bone marrow transplant

To examine whether MIM deficiency might affect chemotaxis in vivo, we examined the homing of transplanted leukocytes into lymphoid organs, a process that is driven predominately by SDF-1. We transplanted BM MNCs from either CD45.2 MIM-/- or WT mice into lethally irradiated CD45.1 WT mice. 24h later, the period that commonly defines a homing process33, donor cells in recipient BM, peripheral blood (PB) and spleen were quantitated. There were nearly 2-fold greater numbers of MIM-/- donor cells expressing either Gr1 or CD11b (markers for neutrophils and monocytes, respectively) in BM (Figure 3A) and spleen (Figure 3B), as compared to WT donor cells. Conversely, numbers of MIM-/- neutrophils and monocytes in the PB of recipients were lower than with WT donor cells (Figure 3C). In addition, increased homing of T (CD3+) and B (CD19+) lymphocytes from MIM-/- mice to both BM and spleen of recipients was also observed. Since there was a similar ratio of leukocytes in the BM of donor MIM-/- mice versus donor WT mice prior to transplant (S-Figure 1A), the increased MIM-/- donor cells in the recipient BM and spleen reflected likely increased homing.

Figure 3. MIM-/- BM cells increased in homing during BM transplant.

2×106 WT or MIM-/- BM cells from CD4.2 mice were transplanted into lethally irradiated CD45.1 WT mice. The frequency of Gr1, CD11b, CD3 and CD19 cells in the donor population were determined by flow cytometry in the BM (A), the spleen (B) and the PB (C) of the recipients 24h after transplantation. Donor Lin-Scal-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) cells in the BM, the spleen and the PB of the recipients were also measured and normalized to WT donor LSK cells in the BM (D). All the data represent mean ± SEM (n=5). (E) BM cells were isolated from recipients 24 h after transplantation and analyzed by colony-forming assay (n=3). All p values were calculated by Student’s t-test.

We also examined the homing of Lin-Sca-1+Kit+ (LSK) cells, a population that is enriched in early hematopoietic cells34 and expresses abundant MIM protein (S-Figure 2). As we had observed with whole BM cells, MIM-/- LSK cells had impaired CXCR4 internalization (S-Figure 3A and 3C). Transplant of MIM-/- donor LSK cells resulted in significantly greater numbers of donor cells in the recipient BM, as compared to transplant of WT donor cells (Figure 3D). Further, MIM-/- donor cells harvested from recipient BM contained higher numbers of colony-forming cells than did WT donor cells (Figure 3E). However, homing of MIM-/- LSK cells to spleen was not significantly increased, indicating that MIM knockout selectively affected homing of HSPCs to the BM, presumably due to a raised affinity of these primitive cells for the BM niche.

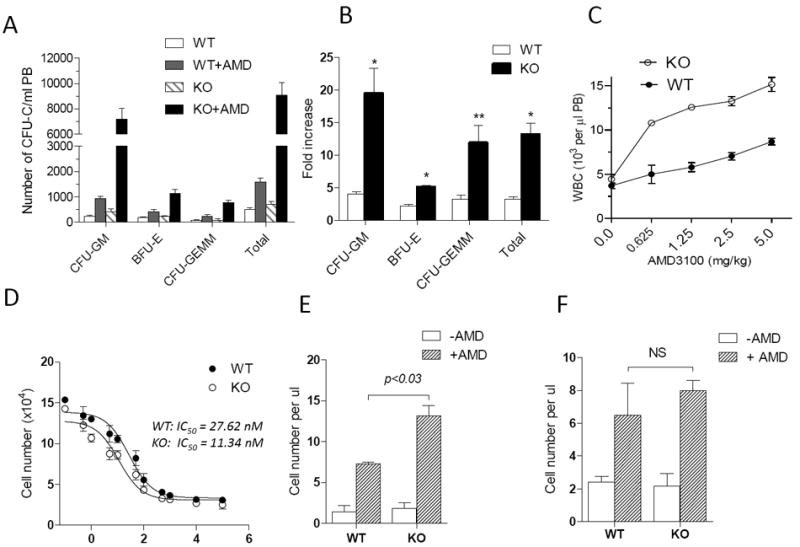

MIM-/- cells were hypersensitive to AMD3100

Analysis of transplanted mice after 4 to 16 weeks did not reveal any significant increases in the frequency of donor leukocytes present in lymphoid organs of mice receiving MIM-/- BM MNCs (S-Figure 4, data not shown), indicating that MIM plays little role in hematopoiesis. Indeed, MIM-/- BM cells showed no significant difference in colony-forming assays (data not shown, also Figure 6E) or proliferation (data not shown) compared with WT BM cells. It was possible that MIM depletion might affect the BM egress of HSPCs, where MIM is otherwise highly expressed (S-Figure 2). Although MIM-/- mice showed a normal ratio of leukocyte subtypes in major lymphoid organs (S-Figure 1A), there were slightly but consistently higher numbers of white blood cells (WBCs) in the blood of MIM-/- mice than in WT mice19 (also Figure 4C). Hence, we assessed whether MIM deficiency affects HSPC mobilization in response to AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. In the absence of any mobilizer, numbers of circulating HSPCs in MIM-/- mice were similar to or slightly higher than in WT mice (Figure 4A). Injection of AMD3100 into mice effectively mobilized HSPCs into PB (Figure 4A). Interestingly, the drug mobilized MIM-/- HSPCs nearly five times better than for WT cells (Figure 4B). Since AMD3100 mobilizes other types of WBCs, though less effectively than HSPCs35, we also measured total WBCs in the PB. In response to different doses of AMD3100, both WT and MIM-/- mice showed considerable increases in WBCs in PB. The number of WBCs in PB of MIM-/- mice was nearly 2-fold greater than that of WT mice (Figure 4C). Consistent with the increased mobilization of HSPCs and total WBCs from BM to PB in MIM-/- mice, MIM-/- cells were more susceptible than WT cells to AMD3100: AMD3100 inhibited chemotaxis of MIM-/- BM cells with an IC50 value of 11.34 nM, whereas it inhibited WT cells with an IC50 of 27.62 nM under the same conditions (Figure 4D).

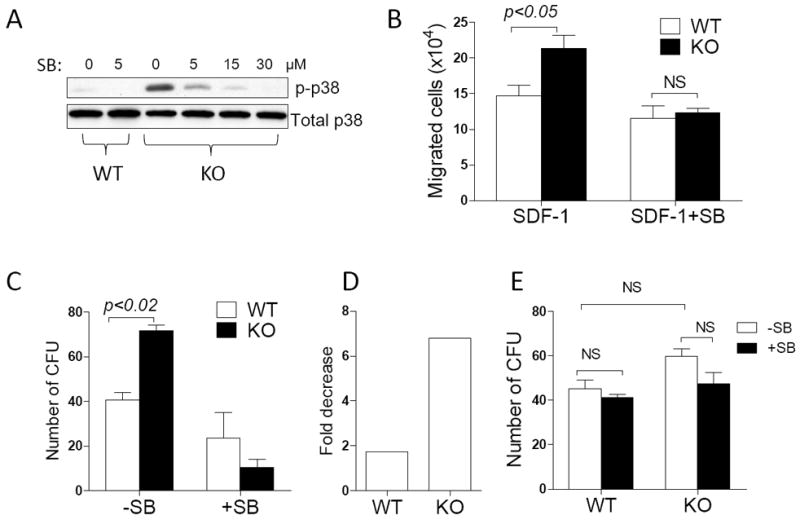

Figure 6. p38 antagonist inhibited the increased mobility and the homing activity of MIM-/- cells.

(A) MIM-/- and WT BM cells were treated for 2h with SB203580 at the concentrations as indicated and then analyzed for the level of phosphorylated p38 by Western blot. (B) WT and MIM-/- BM cells were treated with 5 μM SB203580 for 1h and analyzed for the motility response to SDF-1. The data represent mean ± SEM (n=3). (C) WT and MIM-/- BM cells were treated with 5 μM SB203580 for 1h and subsequently transplanted into lethally irradiated mice. After 24h, donor cells were isolated from the BM of recipients and analyzed for the clonogenic activity (n=2). The number of colonies was also compared between treated and non-treated cells and presented as fold decreases (D). (E) BM cells derived from WT and MIM-/- mice were treated with or without 5 μM SB203580 for 1h and then analyzed for the clonogenic activity. The data represents mean ± SEM (n=3). All the p values were based on t-test. NS, no significance.

Figure 4. MIM-/- cells were hypersensitive to AMD3100.

(A) WT and MIM-/- mice were s.c. injected with 5 mg/kg AMD3100. After 1 h, peripheral cells were collected and measured for the colony forming activity. The numbers of colony forming units (CFU) for different lineages (CFU-GM, BFU-E, and CFU-GEMM) were presented (n=5). (B) The data in A were presented as the fold increase of CFU by comprising AMD3100-injected mice with those without AMD3100 treatment. (C) Mice were injected with different doses of AMD3100 as indicated. After 1h, total white blood cells (WBC) in the circulation of the injected mice were collected and estimated by Hemavet hematology analyzer (n=3). (D) MNCs derived from the BM of WT and MIM-/- mice were analyzed for the chemotactic response to 200 ng/ml SDF-1 in the presence of AMD3100 at the indicated concentrations. The IC50 values were calculated using Prism 5 software. (E) WT CD45.1 mice were transplanted with MNCs derived from the BM of CD45.2 WT or MIM-/- mice. The transplanted mice were then injected with 5mg/Kg AMD3100. After 1h, the amount of CD45.2+CD19+ cells in the PB of treated mice was estimated as described in the Method. The data represents mean ± SEM (n=3). (F) MNCs isolated from WT CD45.1 mice were transplanted into CD45.2 WT or MIM-/- mice (n=3). The transplanted mice were then treated with AMD3100, and the mobilized CD45.1+CD19+ cells in the PB were analyzed as above. *, p<0.002; **; p < 0.02 (t-test), referring to the difference between KO and WT mice.

The level of SDF-1 in PB of MIM-/- mice was significantly higher than that of WT mice (S-Figure 5A), and the SDF-1 level in the BM of MIM-/- mice was lower than in WT mice (S- Figure 5B). Since release of SDF-1 is indispensable for AMD3100 to effectively mobilize HSPCs in mice36, the altered microenvironment in lymphoid organs might have also contributed to the increased response of MIM-/- cells to AMD3100. Thus, we examined the trafficking behavior of MIM-/- cells in a normal microenvironment by transfer of CD45.2 MIM-/- or WT BM-MNCs into WT CD45.1 mice; this was done without irradiation, since radiation profoundly alters the response to AMD3100 (data not shown). 24h later, mice were treated with AMD3100. Since HSPCs could not readily be distinguished by CD45 isotype in conventional colony-forming assay, we assayed donor B cells (CD19+), which expressed abundant MIM19. In the normal environment of WT recipients, MIM-/- B cells mobilized to a greater extent in response to AMD3100 than did WT B cells (Figure 4E). To further examine the impact of microenvironment on MIM-mediated mobilization, BM cells derived from CD45.1 mice were transferred into CD45.2 MIM-/- or WT mice, and the recipient mice were then treated with ADM3100. As shown in Figure 4F, the response of WT B cells to AMD3100 in the MIM-/- microenvironment was slightly higher than that the WT microenvironment. We also measured overall donor WBCs in these recipient mice based on CD45.2 and CD45.1, and obtained a very similar result (S-Figure 6). Thus, MIM mutation influencing both intrinsic properties of leukocytes and their microenvironment, although the former appears to be dominant.

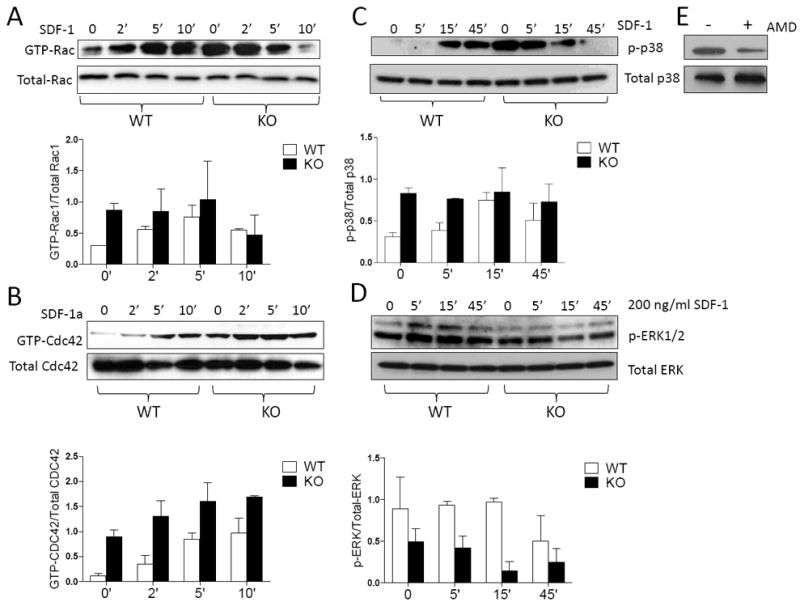

MIM-/- cells contained elevated activities of Rac and Cdc42

We next examined whether increased CXCR4 expression on cell surface affected its signal transduction with focusing on Rho-like small GTPases Rac and Cdc42, which are known to act downstream of CXCR437, 38. The activity of Rac and Cdc42 was measured based on their GTP bound forms: GTP-Rac and GTP-Cdc42. WT BM cells contained a basal level of GTP-Rac and GTP-Cdc42; exposure to SDF-1 resulted in substantial increases in the GTP-bound forms as early as 5 min after exposure (Figure 5A and B). In MIM-/- BM cells, the basal levels of GTP-Rac and GTP-Cdc42 were markedly higher than those in WT cells even under the condition without SDF-1 stimulation.

Figure 5. MIM-/- BM cells have enhanced CXCR4 signaling.

BM cells derived from WT and MIM-/- mice were treated with 200 ng/ml SDF-1 for the times as indicated and then analyzed for the presence of GTP-Rac (A), GTP-Cdc42 (B), phosphorylated p38 (C) and phosphorylated ERK1/2 (D) by Western blot. The charts below each image were the quantification results of three independent experiments. (E) Arresting BM cells of MIM-/- mice were treated with and without AMD3100 for 1h. The phosphorylated p38 was analyzed by Western blot.

Both Rac and Cdc42 play pivotal roles in promoting actin assembly in the cell cortex39. Rac is involved in the formation of lamellipodia and Cdc42 in the formation of micropikes such as filopodia40. Whereas BM derived hematopoietic cells did not display typical filopodia when plated on poly-L-lysine- (S-Figure 7) or fibronectin- (data not shown) coated plates, over 50% of MIM-/- BM MNCs had strong phalloidin staining at their leading edges in the absence of SDF-1, indicative of prominent assembly of actin filaments in the areas (S-Figure 7). In contrast, less than 25% of WT cells had a similar edge-associated actin assembly under the same condition. After exposure to SDF-1, both WT and MIM-/- BM MNCs had a significant increase in actin assembly at their leading edges. However, the degree of this increase with MIM-/- cells was less substantial than that of WT cells, a pattern that is consistent with the changes in content of GTP-associated Rac and Cdc42 in response to SDF-1.

Activation of p38 MAP kinase is implicated in the homing of MIM-/- HSPCs

To investigate whether other signaling molecules might be also affected by MIM deficiency, we examined p38 MAP kinase, which acts downstream of Rac and participates in SDF-1-induced cell migration41, 42. SDF-1 stimulation induced the phosphorylation of p38 after 15 min in WT BM cells, and this phosphorylation persisted at 45 min (Figure 5C). In contrast, MIM-/- BM cells contained a high level of phosphorylated p38 even in the absence of SDF-1 (Figure 5C). The level of p38 phosphorylation diminished when MIM-/- BM cells were treated with AMD3100 (Figure 5E), indicating that CXCR4 is involved in the constitutive activation of p38. Activation of p38 is known to be often associated with apoptosis43. However, we did not observe any significant increase in the death of WT or MIM-/- cells with or without SDF-1 exposure (S-Figure 8). We also examined ERK1/2 MAP kinase, which like p38, acts downstream of SDF-1. Although SDF-1 induced a slight increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation in WT BM cells (Figure 5D), no significant increase in phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was found in MIM-/- cells during the early phase of stimulation.

To further verify p38 activation in MIM-/- cells, we examined the expression of CD49d (also α4 integrin subunit), which is implicated in cell adhesion and regulated by p3844. Quantitative RT-PCR or flow cytometry revealed approximately 2-fold higher CD49d expression in MIM-/- BM cells than in WT cells in the absence of SDF-1 (S-Figure 9A and 9B). Upon treatment with SDF-1, CD49d expression increased slightly in WT cells but decreased in MIM-/- cells, a pattern similar to that with p38 phosphorylation. As a control, we also examined CD62L (L-selectin), which is not directly regulated by p38 MAP kinase, and found no significant difference of CD62L expression in WT versus MIM-/- BM cells (S-Figure 9C and 9D).

Last, we examined whether there is a relation between p38 activation and the enhanced homing activity of MIM-/- HSPCs by treating BM cells with SB203580, a specific inhibitor of both p38α and p38β isoforms45. In vitro, SB203580 at concentrations as low as 5 μM effectively inhibited phosphorylation of p38 in MIM-/- BM cells (Figure 6A). In the absence of SB203580, MIM-/- BM cells had a higher motility than did WT BM cells in response to SDF-1 (Figure 6B). However, the increased motility of MIM-/- BM cells was diminished in the presence of SB203580. To evaluate the effect of the drug on HSPC homing to BM in vivo, BM cells were treated with SB203580 for 1h prior to transplant into mice. While SB203580 decreased the ability of both transplanted MIM-/- and WT HSPCs to home to BM, the degree of the decrease was significantly greater for MIM-/- cells than that for WT cells (nearly a 7-fold reduction with MIM-/- cells versus 1.7-fold decrease with WT cells) (Figure 6D). To ensure that the observed decrease was not due to a possible inhibition of colony formation per se, we also examined the direct effect of SB203580 on the clonogenic activity of BM cells in vitro. Treatment of MIM-/- or WT BM cells with SB203580 for 1h did not result in significant inhibition of numbers of hematopoietic colonies (Figure 6E). Thus, homing of MIM-/- HSPCs to BM is more dependent upon the function of p38 MAP kinase than is homing of WT cells.

DISCUSSION

In this report we made the novel observation that MIM-/- BM-derived leukocytes, including HSPCs, have elevated CXCR4 expression on their cell surface compared with WT cells. Consistent with this, MIM-/- BM cells had significantly greater in vitro chemotactic response to SDF-1, greater homing to mouse BM, greater CXCR4 signaling, and less CXCR4 internalization in response to SDF-1. The precise roles of MIM and other I-BAR proteins in endocytosis have not yet been illustrated. These proteins have been thought to promote only protrusive or negative membrane curvature, such as those associated with the initiation of filopodia or dendritic spines30,46. In contrast, the membrane deformation associated with endocytosis is a kind of positive curvature, establishment of which is often carried out by assembly of proteins with a concave BAR domain possessed by the majority of BAR domain proteins47. For example, the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles requires the function of the shallowly curved F-BAR protein FCHo48. However, there is growing evidence that F-BAR proteins are also engaged in the control of the formation of filopodia, a typical type of membrane protrusive structure49-51. Our data supports the notion that ultimate functions of BAR proteins may be determined by their concerted action with other factors, abundance in a local area, and exposure to different extracellular stimuli, in addition to the shape of BAR domains.

MIM may regulate molecules beyond CXCR4. We had previously observed that B cells derived from MIM-/- mice show a partial defect in the internalization of CXCR5, the receptor for chemokine CXCL1319. Unlike CXCR4, however, impaired CXCR5 internalization is correlated with partially impaired chemotactic response to CXCL13, whereas impaired CXCR4 internalization in MM-/- cells leads to enhanced response to SDF-1 and enhanced CXCR4 signaling. One plausible explanation is that CXCR4 signaling is not normally coupled with its internalization, which is triggered by phosphorylation of several C-tail Ser/Thr residues via either protein kinase C or G protein-coupled receptor kinase52. Mutations in the C-tail of CXCR4 are considered as the genetic etiology for the WHIM syndrome9 because defective internalization results in a constitutively activated receptor53. WHIM-like mutations also occur in Waldenstron’s Macroglobulinemia, in which enhanced CXCR4 signaling drives proliferation, dissemination and drug resistance54. Although we did not observe a significant proliferative advantage for MIM-/- cells, we have previously reported that MIM-/- mice display chronic progression of B cell malignances19. Hence, our findings here concerning deregulated CXCR4 signaling in MIM-/- cells suggests a pathological link to the progression of lymphomas in MIM-/- mice, a subject that warrants further investigation.

One of the characteristics of WHIM syndrome is that the egress of leukocytes from BM is severely compromised, causing chronic leukopenia55. Unlike WHIM, however, MIM-/- mice exhibit a slightly but consistently higher level of leukocytes in the PB even without AMD3100 treatment. Egress of leukocytes into the peripheral circulation of MIM-/- mice was even more dramatic after AMD3100 treatment. One explanation for the difference is due to pleiotropic functions of MIM. In fact, MIM-/- mice have increased SDF-1 in the circulation, which is known to facilitate the egress of leukocytes and HSPCs36. Also, MIM depletion could influence the configuration of other membrane proteins as evidenced by increased affinity of MIM-/- cells for AMD3100. Another possibility is that there may be altered cell-cell interactions in the BM and the vascular system of MIM-/- mice. Indeed, MIM-/- cells have enhanced expression of CD49d and altered activation of small-GTPases Rac and Cdc42. Because these molecules play critical roles in the actin dynamics, changes in their signaling would likely affect cell-cell interactions, deregulation of which has been thought to be the cause for the renal tubule dilation manifested in MIM-/- mice27. We speculate that all these changes would bring an overall negative effect to HSPCs, eventually facilitating their egress from BM to PB. Nevertheless, enhanced CXCR4 activity is able to yield a temporary benefit for MIM-/- cells to home during BM transplant, which involves lethal irradiation, a procedure that disturbs dramatically the BM environment by inducing massive cell deaths and increase of secreted chemokines and cytokines, including SDF-133, 56. In fact, we have observed that either WT or MIM-/- BM cells in irradiated mice failed to mobilize effectively to PB even after treatment with AMD3100 (data not shown), implying that the BM transplant favors homing over egress. Taken together, our data indicates that a global depletion of MIM affects both CXCR4 on BM cells and the BM environment, resulting in a complexity that may be likely attributed to the difference between MIM-/- mice and WHIM syndrome. Future effort with cell type-specific MIM knockout mice would be necessary to delineate the specific function of MIM in leukocytes and their interactions with lymphoid niches.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available at Leukemia’s website

Conflict-of-interest Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Ma Q, Jones D, Springer TA. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is required for the retention of B lineage and granulocytic precursors within the bone marrow microenvironment. Immunity. 1999 Apr;10(4):463–471. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zou YR, Kottmann AH, Kuroda M, Taniuchi I, Littman DR. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature. 1998 Jun 11;393(6685):595–599. doi: 10.1038/31269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, Nagasawa T. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. 2006 Dec;25(6):977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazo IB, Massberg S, von Andrian UH. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell trafficking. Trends Immunol. 2011 Oct;32(10):493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burger M, Glodek A, Hartmann T, Schmitt-Graff A, Silberstein LE, Fujii N, et al. Functional expression of CXCR4 (CD184) on small-cell lung cancer cells mediates migration, integrin activation, and adhesion to stromal cells. Oncogene. 2003 Nov 6;22(50):8093–8101. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchese A. Endocytic trafficking of chemokine receptors. Current opinion in cell biology. 2014 Apr;27:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCormick PJ, Segarra M, Gasperini P, Gulino AV, Tosato G. Impaired recruitment of Grk6 and beta-Arrestin 2 causes delayed internalization and desensitization of a WHIM syndrome-associated CXCR4 mutant receptor. PloS one. 2009;4(12):e8102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawai T, Choi U, Whiting-Theobald NL, Linton GF, Brenner S, Sechler JM, et al. Enhanced function with decreased internalization of carboxy-terminus truncated CXCR4 responsible for WHIM syndrome. Experimental hematology. 2005 Apr;33(4):460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balabanian K, Lagane B, Pablos JL, Laurent L, Planchenault T, Verola O, et al. WHIM syndromes with different genetic anomalies are accounted for by impaired CXCR4 desensitization to CXCL12. Blood. 2005 Mar 15;105(6):2449–2457. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao Y, Hunter ZR, Liu X, Xu L, Yang G, Chen J, et al. The WHIM-like CXCR4 somatic mutation activates AKT and ERK, and promotes resistance to ibrutinib and other agents used in the treatment of Waldenstrom’s Macroglobulinemia. Leukemia. 2014 Jun 10; doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Treon SP, Cao Y, Xu L, Yang G, Liu X, Hunter ZR. Somatic mutations in MYD88 and CXCR4 are determinants of clinical presentation and overall survival in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2014 May 1;123(18):2791–2796. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-550905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neel NF, Schutyser E, Sai J, Fan GH, Richmond A. Chemokine receptor internalization and intracellular trafficking. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2005 Dec;16(6):637–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mim C, Unger VM. Membrane curvature and its generation by BAR proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012 Dec;37(12):526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habermann B. The BAR-domain family of proteins: a case of bending and binding? EMBO Rep. 2004 Mar;5(3):250–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao H, Michelot A, Koskela EV, Tkach V, Stamou D, Drubin DG, et al. Membrane-sculpting BAR domains generate stable lipid microdomains. Cell reports. 2013 Sep 26;4(6):1213–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frost A, Unger VM, De Camilli P. The BAR domain superfamily: membrane-molding macromolecules. Cell. 2009 Apr 17;137(2):191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SH, Kerff F, Chereau D, Ferron F, Klug A, Dominguez R. Structural basis for the actin-binding function of missing-in-metastasis. Structure. 2007 Feb;15(2):145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saarikangas J, Zhao H, Pykalainen A, Laurinmaki P, Mattila PK, Kinnunen PK, et al. Molecular mechanisms of membrane deformation by I-BAR domain proteins. Current biology : CB. 2009 Jan 27;19(2):95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu D, Zhan XH, Zhao XF, Williams MS, Carey GB, Smith E, et al. Mice deficient in MIM expression are predisposed to lymphomagenesis. Oncogene. 2012 Jul 26;31(30):3561–3568. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YG, Macoska JA, Korenchuk S, Pienta KJ. MIM, a potential metastasis suppressor gene in bladder cancer. Neoplasia. 2002 Jul-Aug;4(4):291–294. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lei R, Tang J, Zhuang X, Deng R, Li G, Yu J, et al. Suppression of MIM by microRNA-182 activates RhoA and promotes breast cancer metastasis. Oncogene. 2014 Mar 6;33(10):1287–1296. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang S, Qi Q. MTSS1 suppresses cell migration and invasion by targeting CTTN in glioblastoma. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2015 Feb;121(3):425–431. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1656-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schemionek M, Kharabi Masouleh B, Klaile Y, Krug U, Hebestreit K, Schubert C, et al. Identification of the Adapter Molecule MTSS1 as a Potential Oncogene-Specific Tumor Suppressor in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. PloS one. 2015;10(5):e0125783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattila PK, Salminen M, Yamashiro T, Lappalainen P. Mouse MIM, a tissue-specific regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics, interacts with ATP-actin monomers through its C-terminal WH2 domain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003 Mar 7;278(10):8452–8459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Liu J, Smith E, Zhou K, Liao J, Yang GY, et al. Downregulation of missing in metastasis gene (MIM) is associated with the progression of bladder transitional carcinomas. Cancer investigation. 2007 Mar;25(2):79–86. doi: 10.1080/07357900701205457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia S, Li X, Johnson T, Seidel C, Wallace DP, Li R. Polycystin-dependent fluid flow sensing targets histone deacetylase 5 to prevent the development of renal cysts. Development. 2010 Apr;137(7):1075–1084. doi: 10.1242/dev.049437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saarikangas J, Mattila PK, Varjosalo M, Bovellan M, Hakanen J, Calzada-Wack J, et al. Missing- in-metastasis MIM/MTSS1 promotes actin assembly at intercellular junctions and is required for integrity of kidney epithelia. Journal of cell science. 2011 Apr 15;124(Pt 8):1245–1255. doi: 10.1242/jcs.082610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mattila PK, Pykalainen A, Saarikangas J, Paavilainen VO, Vihinen H, Jokitalo E, et al. Missing- in-metastasis and IRSp53 deform PI(4,5)P2-rich membranes by an inverse BAR domain-like mechanism. The Journal of cell biology. 2007 Mar 26;176(7):953–964. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin J, Liu J, Wang Y, Zhu J, Zhou K, Smith N, et al. Differential regulation of cortactin and N-WASP-mediated actin polymerization by missing in metastasis (MIM) protein. Oncogene. 2005 Mar 17;24(12):2059–2066. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saarikangas J, Kourdougli N, Senju Y, Chazal G, Segerstrale M, Minkeviciene R, et al. MIM-Induced Membrane Bending Promotes Dendritic Spine Initiation. Developmental cell. 2015 Jun 22;33(6):644–659. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu D, Zhan XH, Niu S, Mikhailenko I, Strickland DK, Zhu J, et al. Murine missing in metastasis (MIM) mediates cell polarity and regulates the motility response to growth factors. PloS one. 2011;6(6):e20845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dawson JC, Legg JA, Machesky LM. Bar domain proteins: a role in tubulation, scission and actin assembly in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Trends in cell biology. 2006 Oct;16(10):493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lapidot T, Dar A, Kollet O. How do stem cells find their way home? Blood. 2005 Sep 15;106(6):1901–1910. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okada S, Nakauchi H, Nagayoshi K, Nishikawa S, Miura Y, Suda T. In vivo and in vitro stem cell function of c-kit- and Sca-1-positive murine hematopoietic cells. Blood. 1992 Dec 15;80(12):3044–3050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Broxmeyer HE, Orschell CM, Clapp DW, Hangoc G, Cooper S, Plett PA, et al. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005 Apr 18;201(8):1307–1318. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dar A, Schajnovitz A, Lapid K, Kalinkovich A, Itkin T, Ludin A, et al. Rapid mobilization of hematopoietic progenitors by AMD3100 and catecholamines is mediated by CXCR4-dependent SDF-1 release from bone marrow stromal cells. Leukemia. 2011 Aug;25(8):1286–1296. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cancelas JA, Williams DA. Rho GTPases in hematopoietic stem cell functions. Current opinion in hematology. 2009 Jul;16(4):249–254. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32832c4b80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang L, Zheng Y. Cdc42: a signal coordinator in hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. Cell cycle. 2007 Jun 15;6(12):1445–1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cancelas JA, Jansen M, Williams DA. The role of chemokine activation of Rac GTPases in hematopoietic stem cell marrow homing, retention, and peripheral mobilization. Experimental hematology. 2006 Aug;34(8):976–985. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ridley AJ, Hall A. Distinct patterns of actin organization regulated by the small GTP-binding proteins Rac and Rho. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1992;57:661–671. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1992.057.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rousseau S, Dolado I, Beardmore V, Shpiro N, Marquez R, Nebreda AR, et al. CXCL12 and C5a trigger cell migration via a PAK1/2-p38alpha MAPK-MAPKAP-K2-HSP27 pathway. Cellular signalling. 2006 Nov;18(11):1897–1905. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bendall LJ, Baraz R, Juarez J, Shen W, Bradstock KF. Defective p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling impairs chemotaxic but not proliferative responses to stromal-derived factor-1alpha in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer research. 2005 Apr 15;65(8):3290–3298. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou L, Opalinska J, Verma A. p38 MAP kinase regulates stem cell apoptosis in human hematopoietic failure. Cell cycle. 2007 Mar 1;6(5):534–537. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.5.3921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khurana S, Buckley S, Schouteden S, Ekker S, Petryk A, Delforge M, et al. A novel role of BMP4 in adult hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell homing via Smad independent regulation of integrin-alpha4 expression. Blood. 2013 Jan 31;121(5):781–790. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-446443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dar AC, Shokat KM. The evolution of protein kinase inhibitors from antagonists to agonists of cellular signaling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:769–795. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-090308-173656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamagishi A, Masuda M, Ohki T, Onishi H, Mochizuki N. A novel actin bundling/filopodium-forming domain conserved in insulin receptor tyrosine kinase substrate p53 and missing in metastasis protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004 Apr 9;279(15):14929–14936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qualmann B, Koch D, Kessels MM. Let’s go bananas: revisiting the endocytic BAR code. The EMBO journal. 2011 Aug 31;30(17):3501–3515. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henne WM, Boucrot E, Meinecke M, Evergren E, Vallis Y, Mittal R, et al. FCHo proteins are nucleators of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science. 2010 Jun 4;328(5983):1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.1188462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guerrier S, Coutinho-Budd J, Sassa T, Gresset A, Jordan NV, Chen K, et al. The F-BAR domain of srGAP2 induces membrane protrusions required for neuronal migration and morphogenesis. Cell. 2009 Sep 4;138(5):990–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Starnes TW, Bennin DA, Bing X, Eickhoff JC, Grahf DC, Bellak JM, et al. The F-BAR protein PSTPIP1 controls extracellular matrix degradation and filopodia formation in macrophages. Blood. 2014 Apr 24;123(17):2703–2714. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-516948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee K, Gallop JL, Rambani K, Kirschner MW. Self-assembly of filopodia-like structures on supported lipid bilayers. Science. 2010 Sep 10;329(5997):1341–1345. doi: 10.1126/science.1191710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borroni EM, Mantovani A, Locati M, Bonecchi R. Chemokine receptors intracellular trafficking. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2010 Jul;127(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lagane B, Chow KY, Balabanian K, Levoye A, Harriague J, Planchenault T, et al. CXCR4 dimerization and beta-arrestin-mediated signaling account for the enhanced chemotaxis to CXCL12 in WHIM syndrome. Blood. 2008 Jul 1;112(1):34–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Treon SP. How I treat Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2015 May 22; doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-553974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wetzler M, Talpaz M, Kleinerman ES, King A, Huh YO, Gutterman JU, et al. A new familial immunodeficiency disorder characterized by severe neutropenia, a defective marrow release mechanism, and hypogammaglobulinemia. The American journal of medicine. 1990 Nov;89(5):663–672. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90187-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kang Y, Chen BJ, Deoliveira D, Mito J, Chao NJ. Selective enhancement of donor hematopoietic cell engraftment by the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 in a mouse transplantation model. PloS one. 2010;5(6):e11316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.