Abstract

We recently reported our findings of resting state functional connectivity in the human spinal cord: in a cohort of healthy volunteers we observed robust functional connectivity between left and right ventral (motor) horns and between left and right dorsal (sensory) horns (Barry et al., 2014). Building upon these results, we now quantify the within-subject reproducibility of bilateral motor and sensory networks (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.54–0.56) and explore the impact of including frequencies up to 0.13 Hz. Our results suggest that frequencies above 0.08 Hz may enhance the detectability of these resting state networks, which would be beneficial for practical studies of spinal cord functional connectivity.

INTRODUCTION

We recently reported the use of blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) at 7 Tesla to detect resting state correlations within the gray matter of spinal cords, suggesting the potential for using high-field fMRI to assess functional connectivity in the human spinal cord (Barry et al., 2014). Our observations of significant correlations between ventral horns and between dorsal horns revealed spinal cord motor and sensory networks that are detectable in a resting state. The nature of these spinal cord networks is not yet known, but they may subserve the relay and processing of inputs from the peripheral nervous system and/or sensorimotor areas in the cerebrum, or perhaps reflect locally generated signals necessary to maintain a basal level of neuronal activity (Eippert and Tracey, 2014).

Additionally, Kong et al. used a spinal cord template to observe resting state spinal cord networks at a lower field strength (Kong et al., 2014). Interestingly, these papers (Barry et al., 2014; Kong et al., 2014) used methods that were quite different, and despite the differences between data acquisition, processing methods and field strengths, the independent reporting of reproducible low-frequency correlations in ventral gray matter from two different research labs adds credibility to the existence of these spinal cord networks. However, one interesting and important difference between these studies is that Kong et al. observed unilateral sensory networks whereas we observed bilateral connectivity between dorsal (sensory) horns. It is not yet clear why this difference was observed, but our measurements of dorsal connectivity were markedly weaker than measurements of ventral connectivity (Barry et al., 2014). As such, connectivity within the sensory network may be inherently weaker than connectivity within the motor network, and thus benefit from the higher sensitivity to BOLD signal fluctuations at ultra-high magnetic fields (Ogawa et al., 1993; Gati et al., 1997). Moreover, as in all fMRI studies, the particular choice of processing and selection of threshold criteria can affect the results reported.

The goal of our previous report was to demonstrate the existence of resting state networks in the human spinal cord and verify they could be detected by resting state fMRI. In our current study, we report the within-subject reproducibility of bilateral ventral (motor) and dorsal (sensory) networks, which is a key property for their potential use as biomarkers of functional recovery, the effects of aging or degeneration, or of interventions. Reproducibility is dependent upon signal to noise ratio, temporal signal to noise ratio, and the choice of imaging parameters (selection of TE, bandwidth, etc.), so each field and each application requires its own assessment. Supplementary power spectra analyses in our original paper suggested that frequencies above 0.08 Hz may contain signal power related to functional connectivity, so herein we also explore resting state fluctuations up to 0.13 Hz.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data acquisition

Experiments were performed on a Philips Achieva 7 Tesla scanner with a custom-designed (Nova Medical Inc.) quadrature transmit and 16-channel receive coil array for cervical spinal cord imaging. Twenty-three healthy volunteers (11 male, 18–36 years; 12 female, 21–35 years; 25.7±4.5 years) with no history of spinal cord injury or neurological impairment were recruited and scanned under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Female participants of childbearing potential required a negative urine pregnancy test for the scan to proceed. Non-MR study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Vanderbilt University (Harris et al., 2009).

Anatomical axial images with high spatial resolution and T2*-weighting were acquired with the following MR parameters: field of view = 160 × 160 mm2, 12 4-mm slices (centered on the C3/C4 junction, as shown in Figure 1A), nominal voxel size = 0.6 × 0.6 × 4 mm3, interpolated voxel size = 0.31 × 0.31 × 4 mm3, repetition time = 303 ms, echo time = 8.2 ms, flip angle = 25°, sensitivity encoding (SENSE) (Pruessmann et al., 1999) reduction factor = 2.0 (anterior-posterior), number of acquisitions averaged = 8, total acquisition time = 5 min 22 sec.

Figure 1.

Acquisition and analysis strategy for resting state spinal cord fMRI at 7 Tesla. (a) Mid-sagittal slice from a healthy volunteer showing the cervical spinal cord and imaging stack centered on the C3/C4 intervertebral disc. (b) For each axial slice in the imaging stack, measurements of functional connectivity between ventral (motor) horns and between dorsal (sensory) horns are calculated. Partial correlations are also calculated between ventral and dorsal horns on each side to investigate the reproducibility of ipsilateral correlations.

Functional images with identical slice placement were acquired with a 3D multi-shot gradient-echo sequence to minimize T2* blurring and geometric distortions (Barry et al., 2011). The functional MR parameters for all subjects were: field of view = 160 × 160 mm, 12 4-mm slices, voxel size = 0.91 × 0.91 × 4 mm3, repetition time = 17 ms, echo time = 8.0 ms, flip angle = 15°, echo train length (number of k-space lines acquired per shot) = 9, SENSE reduction factor = 1.56 (anterior-posterior), volume acquisition time = 3.34 sec (278 ms/slice), number of volumes = 150 (after 10 “dummy” scans), total scan time = 9 min, max gradient strength = 30 mT/m, max slew rate = 175 mT/m/ms. Respiratory and cardiac cycles were externally monitored and recorded using a respiratory bellow and pulse oximeter.

Two functional runs of comparable quality were acquired for each volunteer. In most cases, these runs were acquired sequentially in less than 20 minutes. For a few subjects, however, obtaining an adequate shim in the region from C2 to C5 was particularly challenging and the shimming routine had to be repeated between functional runs to obtain a satisfactory shim for the second functional run. For these few subjects, the acquisition of both functional runs was completed in 30–35 minutes. The shimming procedure used only first order shims to shim the cervical cord because linear shims produced the most consistent results across subjects (the use of second and third order shims at 7 Tesla occasionally produced spinal cord images with visibly worse B0 artifacts compared to images acquired using only linear shims, which may have been caused by inaccurate estimation of higher order spherical harmonics due to insufficient signal-to-noise ratio within the small shimming region).

Data processing

Functional data were preprocessed using the following 15-step procedure, which is a refined version of the procedure presented in our previous report (Barry et al., 2014). The small size of the spinal cord and detrimental impact of physiological noise, susceptibility gradients, and geometric distortions make co-registration of functional images to an anatomical image challenging at the best of times, but these problems are exacerbated in the current study because two functional data sets must be registered to an anatomical image for each subject. As such, both registrations need to be accurate because even a relatively small mis-registration in one run (possibly caused by a change in the shim) could prevent regions of focal correlations from overlapping and thus underestimate measurements of reproducibility. To address these challenges, we developed a new multi-stage algorithm for robust co-registration of functional spinal cord images to their respective anatomical images. This custom functional-to-anatomical registration algorithm (step #9) performed very well when functional data quality was average to high, and still performed acceptably well in “worst case” scenarios when functional images were distorted by severe artifacts and/or susceptibility-induced signal drop-outs.

For each slice, a “not-spine” mask was defined by drawing a region around the entire spinal cord and then logically inverting it (used in step #2).

For each slice, data-driven “regressors of no interest” were selected via principal component analysis (PCA) of all voxels within the not-spine mask to identify structured noise sources that would similarly affect the spinal cord and external (neck) regions. The number of eigenvectors selected reflected up to 80% of the slice-wise cumulative variance or until the difference between two successive eigenvalues was less than 5%. These vectors were regressed from the time series of all voxels within a slice, and significantly improved the efficacy of motion correction (step #5) by mitigating widespread intensity fluctuations due to physiological noise.

For each slice, a representative (target) volume was automatically selected for motion correction by calculating the median intensity of each voxel over time and then selecting the volume closest to the median image (identified via minimal least squares error).

For each slice of the target volume, a 2D Gaussian weighting kernel was manually defined with the full-width-at-half-maximum set at the CSF boundaries. These weighting masks were used in rigid-body motion correction (step #5).

Rigid-body motion correction was performed on a slice-wise basis (using 3dWarpDrive in AFNI) (Cox, 1996) using the target volumes (identified in step #3). Motion was constrained to be within-plane translation (i.e., no rotation of the cord). To mitigate the detrimental effects of sporadic artifacts (e.g., swallowing) on motion parameter estimation, translation estimates were temporally filtered with a 5-point median filter and then re-applied (using 3dAllineate in AFNI) (Cox, 1996) to the original data before motion correction. The initial registration (to obtain motion parameter estimates) used quintic interpolation and the final transformation used sinc interpolation.

An established image correction technique called RETROICOR (“retrospective image correction”) (Glover et al., 2000) (implemented in AFNI) (Cox, 1996) was applied to the entire functional volume to further reduce quasi-periodic intensity variations due to physiological noise.

Using the high-resolution anatomical images as a reference, masks defining the boundaries of gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and CSF were created for each slice. In regions of significant signal drop-out (typically observed on the dorsal side at the CSF/bone interface), the CSF boundary should closely reflect the apparent boundary (not what the boundary should have been in the absence of signal drop-out).

For each slice of the anatomical image, a 2D weighting mask was automatically constructed using the GM, WM, and CSF masks (step #7), plus a CSF “boundary mask” (created by dilating the CSF mask outwards by 5 mm and then performing a logical XOR with the CSF mask). Voxels within the GM or WM masks were assigned a value of ‘5’ and voxels within the CSF or boundary masks were assigned a value of ‘1’, which heavily weights features within the cord, but still uses features of surrounding CSF and the CSF/bone boundary to guide the registration algorithm. These weighting masks were used to calculate the transformation parameters for each cost function (step #9).

For each slice, affine registration of functional images to the anatomical image was performed (via 3dAllineate) with degrees of freedom constrained to within-plane translation and scaling (maximum of 1% in the read direction and 2% in the phase-encode direction). This important step was divided into four sub-steps: (a) an initial translation was estimated based upon the median translation required to align the center of mass of each functional image multiplied by the spine mask (inverse not-spine mask) to the anatomical image (similarly multiplied by the spine mask); (b) a two-stage (coarse and fine) registration was applied for a given cost function (explained in step #9d) and masked functional image (step #9c): in the first stage, the search area was ±1.5 mm (anterior-posterior) and ±1.1 mm (left-right) relative to the initial translation (step #9a), and in the second stage the search area was reduced to ±0.75 mm (anterior-posterior) and ±0.38 mm (left-right) relative to the coarse translation; (c) step #9b was applied to the average functional image (calculated via 3dTstat) from data generated by step #6; (d) steps #9b and #9c were repeated for various cost functions available through 3dAllineate, and then the final transformation was calculated as the median translation across cost functions in each dimension. Due to the challenging nature of spinal cord registrations, no single cost function will be optimal 100% of the time, but we observe that several of 3dAllineate’s cost functions produce very similar results the majority of the time. Thus, to protect against occasional spurious transforms (observed in images with significant signal drop-out or artifacts), our current implementation calculates the median of the following ten cost functions (http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/pub/dist/doc/program_help/3dAllineate.html): Hellinger distance (“hel”), Pearson (“ls”) and Spearman (“sp”) correlation coefficients, mutual information (“mi”), normalized mutual information (“nmi”), correlation ratios (“crM”, “crA”, and “crU”), joint entropy (“je”), and local Pearson correlation (“lpa”). This step was guided by empirical observations, and may be modified to optimize for different data types or spatial contrasts. Nota bene: the boundary parameters defined in step #9b were selected to exceed the maximum residual translation observed (~1.5 mm in a slice with significant distortions) and increase co-registration accuracy, and are applicable to all the spinal cord data sets that we have analyzed to date. However, these parameters may be increased for specific applications where a greater functional-to-anatomical translation may occur.

The final affine transforms for each slice (calculated in step #9) were applied to all functional volumes (via 3dAllineate), and transformed functional images were resampled (with sinc interpolation) to match the final resolution of the anatomical volume (voxel size = 0.31 × 0.31 × 4 mm3).

The quality of the final functional-to-anatomical alignments were visually verified using MRIcron (www.mccauslandcenter.sc.edu/mricro/mricron).

For each slice, additional data-driven “regressors of no interest” were selected via PCA of all functional voxels within the CSF mask (defined in step #7) to identify structured noise sources that would similarly affect gray matter and CSF. The number of eigenvectors selected reflected up to 50% of the slice-wise cumulative variance or until the difference between two successive eigenvalues was less than 5%. These vectors were regressed from the time series of all spinal cord voxels within a slice.

For each slice, a “global” white matter signal was calculated via PCA of all functional voxels within the white matter mask and extraction of the first eigenvector (typically representing 10–40% of the variance). This was primarily done to mitigate any residual variance due to shifting of the white matter boundary (caused by motion) but would also reduce variance caused by residual physiological noise. This vector was regressed from the time series of all gray and white matter voxels within a slice.

In preparation for region of interest (ROI)-based analyses of functional connectivity, resultant functional data were bandpass filtered between 0.01 and 0.08 Hz (or 0.13 Hz) using a Chebyshev Type II filter (‘cheby2’ and ‘filtfilt’ in Matlab) to emphasize low-frequency signals of interest. Nota bene: a frequency of 0.13 Hz mimics the supplementary analyses in our previous report (Barry et al., 2014), and was selected for that study because it was the highest unaliased frequency that could be resolved with a temporal sampling rate of 3.6 s (i.e., 1/(3.6 s)/2 ≈ 0.13 Hz). In our present study, fMRI data were acquired with a slightly faster sampling rate of 3.34 s, which translates to an unaliased frequency of ~0.14 Hz; however, an upper frequency of 0.13 Hz was used to facilitate a comparison between the previous supplementary analyses and the current investigation.

In preparation for ROI-based analyses, gray and white matter masks (defined in step #7) were subdivided into quadrants to identify left and right ventral and dorsal horns (excluding central gray matter connecting left and right sides), as well as the four adjacent white matter regions. Each of these eight sub-region masks (per slice) were morphologically eroded (using ‘imerode’ in Matlab) to remove the outermost voxels and mitigate partial volume effects. For gray matter the morphological eroding object was a disk with a radius of 3 voxels, and for white matter it was a disk with a radius of 6 voxels. If the eroded sub-region did not contain any voxels (i.e., the disk was too large) then the disk size was incrementally decreased by 1 interpolated pixel (0.31 × 0.31 mm2) and the erosion process repeated until the innermost area of each sub-region was extracted.

Data analysis

The ROI-based analyses presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3 explored the reproducibility of within-slice correlations between gray matter horns for two sequential functional runs. Such analyses require both functional runs to be aligned with the anatomical so that ROIs drawn on the anatomical are projected onto the intended anatomy in the functionals. However, even if these functional-to-anatomical alignments were performed optimally (step #9), small geometric distortions on the order of ~1 mm within the cord could still result in sub-millimeter registration inaccuracies between the functional and anatomical, as well as between the two functional runs (because changes in the shim from one run to the next would create different geometric distortions). To partially compensate for potential co-registration inaccuracies between the back-to-back functional runs, each sub-region mask (created in step #15) was dilated in-plane by one interpolated pixel. For ventral horn connectivity, the m individual voxel time series within the left ventral horn mask were correlated with n voxel time series in the right ventral horn mask while controlling for correlations in nearby gray matter subregions (namely the averaged time series within each of the left and right dorsal horn masks). The resultant m×n partial correlations (r) were then converted to z-scores using the Fisher r-to-z transformation z = tanh−1(r)(dof 3)1/2 where dof is the estimated degrees of freedom for each voxel after correction for first-order autocorrelation (Rogers and Gore, 2008). To protect against spuriously high single-voxel correlations, the 95% percentile of this z-score vector was selected as the metric of functional connectivity between the ventral horns. Similarly, for dorsal horn connectivity, the m voxel time series within the left dorsal horn mask were correlated with n voxel time series in the right dorsal horn mask while regressing out the respective time series within the averaged left and right ventral horn masks. As before, the 95% percentile of the vector of partial correlations after conversion to z-scores and correction for first-order autocorrelation was used as the metric of functional connectivity. Finally, the same procedure was used to calculate partial correlations between ventral and ipsilateral dorsal horns: the m voxel time series within a ventral horn mask were correlated with n voxel time series in the ipsilateral dorsal horn mask while regressing out the averaged time series within the contralateral ventral and dorsal horn masks, the resultant vector was converted to z-scores and corrected for first-order autocorrelation, and the 95% percentile was used to construct a distribution of ipsilateral correlations. To quantify the degree of reproducibility of spinal cord functional connectivity in back-to-back fMRI scans, the ‘Case 2’ intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (Shrout and Fleiss, 1979) was calculated for each aggregate z-score plot. The 95% confidence interval of the ICC was estimated using a bootstrap procedure (‘bootci’ in Matlab) and 50,000 subsamples generated using random sampling with replacement.

Figure 2.

Within-slice partial correlations between (a) ventral horns, (b) dorsal horns, (c) left ventral and dorsal horns, and (d) right ventral and dorsal horns. Resting state data were filtered using a 0.01–0.08 Hz bandpass filter before analyses of functional connectivity. Each point represents a pair of z-scores for one slice in one subject (23 subjects × 12 slices/subject = 276 points). To investigate possible slice-level biases across subjects, red denotes values from the superior four slices (C2/C3), green denotes values from the middle four slices (C3/C4), and blue denotes values for the inferior four slices. The majority of ipsilateral correlations (i.e., between ventral and dorsal horns; c and d) lie between z = 0 and z = 4, so these values are marked by solid vertical and horizontal lines on all plots to facilitate visual comparisons between scatterplots. Finally, the black diamond denotes the center of mass of all 276 correlation pairs, where each pair is given equal weighting. These analyses reveal that resting state spinal cord motor (a) and sensory (b) networks both exhibit moderate reproducibility (ICC = 0.54), although mean ventral horn connectivity (z = 4.42) is markedly higher than dorsal horn connectivity (z = 3.24). In comparison, partial correlations between ventral and dorsal horns is low (z = 2.26 across both left and right) and has low reproducibility (ICC = 0.39 and 0.24, respectively).

Figure 3.

The analyses performed to generate Figure 2 were repeated after resting state data were filtered using a 0.01–0.13 Hz bandpass filter. As before, these plots display within-slice partial correlations between (a) ventral horns, (b) dorsal horns, (c) left ventral and dorsal horns, and (d) right ventral and dorsal horns. A few correlations exceed a z-score of 10 in (a) and (b), but the dynamic range was kept at −2 < z < 10 for all plots to facilitate a comparison with Figure 2 (because the vast majority of z-scores are less than 10). The inclusion of frequencies between 0.08 and 0.13 Hz shifts the center of mass (black diamond) upwards along the line of unity in all plots, but this increase is considerably higher for motor network connectivity (Δz = 1.06 to z = 5.48) and sensory network connectivity (Δz = 0.60 to z = 3.84) than ipsilateral partial correlations on the left (Δz = 0.23 to z = 2.57) and right (Δz = 0.24 to z = 2.43) sides. Motor and sensory networks exhibit moderate reproducibility (ICC = 0.56) whereas partial correlations between ipsilateral ventral and dorsal horns (with markedly lower z-scores) demonstrate lower reproducibility (ICC = 0.46 and 0.36, respectively).

The above analyses of four gray matter sub-regions (left ventral, right ventral, left dorsal, right dorsal) considered the correlation between two sub-regions (e.g., left and right ventral) after regression of the average fluctuation within the other two sub-regions (e.g., left and right dorsal). This approach is advantageous because residual non-neuronal variance related to physiological noise or sub-voxel motion nearest to the regions of consideration will be removed so that the residual (partial) correlation will predominantly reflect correlated BOLD signal fluctuations of interest. However, a disadvantage of this approach is that the average time series from all voxels in a gray matter sub-region will undoubtedly contain a BOLD contribution, and the effect of regressing time courses with unknown variance contributions from both physiological noise and BOLD on the calculated ICC is not obvious — especially for ipsilateral correlations between ventral and dorsal sub-regions. Therefore, we repeated the analyses to estimate each ICC and 95% confidence interval for both frequency ranges with the modification that the correlation between two gray matter sub-regions did not regress out average signal fluctuations from nearby gray matter. The results of these additional analyses are presented in Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Figure S2.

Finally, to qualitatively evaluate the spatial reproducibility of functional connectivity in single-subject analyses (presented in Figure 4 and Figure 5), AFNI’s “InstaCorr” function (Cox, 1996) was used to display significant positive and negative correlations (p < 0.0001) between a single gray matter time series and all other gray and white matter voxels in the spinal cord. The resultant correlation maps were overlaid on the corresponding high-resolution anatomical image.

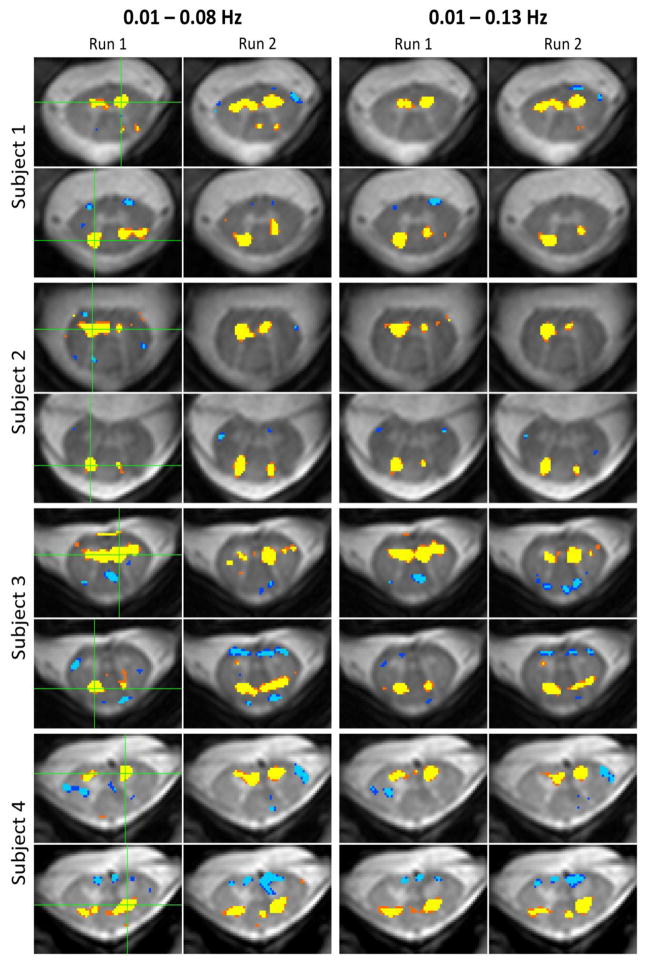

Figure 4.

Examples of reproducible spatial correlations for ventral (motor) and dorsal (sensory) resting state spinal cord networks in C3/C4 across four subjects. A single voxel time series (identified with a green cross in the first column) was selected from a ventral horn and a dorsal horn, and significant correlations (p < 0.0001) throughout gray and white matter were overlaid onto the high-resolution image. The second column displays correlations for the same seed regions but using data from the second resting state run. These 16 single-voxel correlation analyses were then repeated after resting state data are were re-filtered using a 0.01–0.13 Hz bandpass filter to visualize changes in spatial correlation patterns caused by the inclusion of higher frequencies.

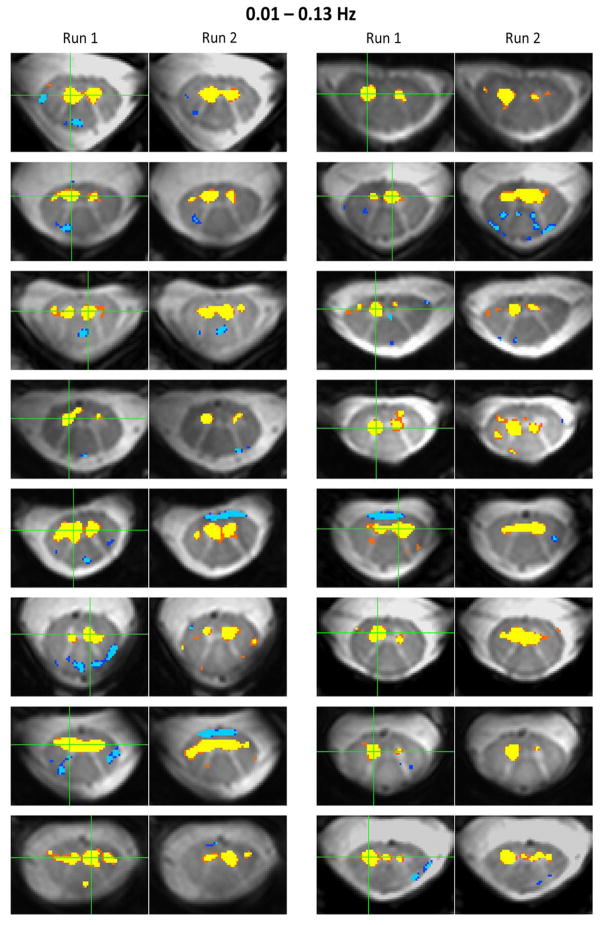

Figure 5.

Examples of reproducible spatial correlations for ventral resting state networks in C3 across an additional 16 subjects. All resting state data were filtered using a 0.01–0.13 Hz bandpass filter. For each pair of images, the seed region is identified with a green cross and significant correlations (p < 0.0001) throughout gray and white matter were overlaid onto the high-resolution image. The extent of positive gray matter correlations exhibit differences from one subject to the next, but overall the most significant and reproducible positive correlations are observed within gray matter horns, and secondary correlations with adjacent white matter are less reproducible between runs.

RESULTS

Functional images covering the C3–C4 spinal cord (Figure 1A) were preprocessed using the 15-step standardized analysis protocol to mitigate issues pertaining to physiological noise, geometric distortions, and signal drop-out. Connectivity measurements (i.e., partial correlations converted to z-scores) between ventral horns and between dorsal horns (Figure 1B), as well as between ventral and ipsilateral dorsal horns, are presented as scatterplots across all slices and subjects in Figure 2 and Figure 3. To investigate possible slice-level biases across subjects, red denotes z-scores from the superior four slices (C2/C3), green denotes z-scores from the middle four slices (C3/C4), and blue denotes z-scores for the inferior four slices. A visual examination of the spread of these three colors across the eight sub-plots did not reveal any obvious z-score bias across vertebral levels, so the possibility of slice-level effects was not considered further.

For a conventional bandpass frequency bandwidth from 0.01 to 0.08 Hz, motor network connectivity (Figure 2A) exhibited a mean z-score of 4.42 across slices and subjects, and 38% of z-score pairs (106 of 276) were in the upper right quadrant (z > 4 for both runs). Similarly, sensory network connectivity (Figure 2B) exhibited a mean z-score of 3.24 and 15% of z-score pairs (42 of 276) were in the upper right quadrant. In comparison, the mean partial correlation between left ventral and ipsilateral dorsal horns (Figure 2C) was much lower (z = 2.34) and had very few z-score pairs in the upper right quadrant (1.8%; 5 of 276), and the mean z-score between right ventral and ipsilateral dorsal horns (Figure 2D) was even lower (z = 2.19) and had only 1 z-score pair (0.36%) in the upper right quadrant. To quantify the reproducibility of these measurements, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (Shrout and Fleiss, 1979) was calculated for each subplot using all 276 z-score pairs. The motor network exhibited an ICC of 0.54 with a 95% confidence interval (C.I.) from 0.46 to 0.62 and the sensory network exhibited a similar ICC of 0.54 with a 95% C.I. from 0.45 to 0.62. The majority of the z-score pairs in the other two plots were tightly clustered in the range 0 < z < 4, and so the ICCs of left and right ventral-dorsal partial correlations were 0.39 (95% C.I. = 0.25 to 0.57) and 0.24 (95% C.I. = 0.13 to 0.34), respectively.

To investigate the possibility that resting state frequencies higher than the conventional 0.08 Hz may contain additional information related to functional connectivity, functional data from all subjects were re-filtered (step #14) with a bandpass filter from 0.01 to 0.13 Hz and then the group-level analysis was repeated. For a wider frequency bandwidth from 0.01 to 0.13 Hz, motor network connectivity (Figure 3A) exhibited a mean z-score of 5.48 across all slices and subjects (an increase, Δ, of 1.06 relative to the same analysis using a 0.01–0.08 Hz filter), and 63% of z-score pairs (163 of 276) were in the upper right quadrant. Similarly, sensory network connectivity (Figure 3B) exhibited a mean z-score of 3.84 (Δz = 0.60) and 29% of z-score pairs (79 of 276) were in the upper right quadrant. In comparison, the mean partial correlation between left ventral and ipsilateral dorsal horns (Figure 3C) was still much lower (z = 2.57; Δz = 0.23) and had very few z-score pairs in the upper right quadrant (4.3%; 12 of 276), and the mean z-score between right ventral and ipsilateral dorsal horns (Figure 3D) was also low (z = 2.43; Δz = 0.24) and had only 4 z-score pairs (1.4%) in the upper right quadrant. Finally, for this wider bandwidth, the motor network exhibited an ICC of 0.56 (95% C.I. = 0.46 to 0.65), the sensory network exhibited a similar ICC of 0.56 (95% C.I. = 0.47 to 0.64), and the ICCs of left and right ventral-dorsal partial correlations were still notably lower at 0.46 (95% C.I. = 0.33 to 0.58) and 0.36 (95% C.I. = 0.25 to 0.45), respectively.

The results from the group re-analyses are presented in the Supplementary Material. In brief, only minor differences are revealed between partial and full correlations for the 0.01–0.08 Hz frequency range (i.e., Figure 2 vs. Supplementary Figure S1). A comparison for the 0.01–0.13 Hz frequency range (i.e., Figure 3 vs. Supplementary Figure S2) reveals a slight extension of the upper range (z > 10) for correlations between ventral horns and between dorsal horns. The most noticeable difference for this wider frequency range is a higher number of z > 4 ipsilateral ventral-dorsal correlations without regression of contralateral signal fluctuations, suggesting that plausible correlations related to functional connectivity may be observed between ventral and dorsal gray matter on some slices (e.g., Figure 4L in Barry et al., 2014).

To investigate the spatial extent of resting state correlations for individual subjects and from one run to the next, Figure 4 presents examples of reproducible resting state spinal cord networks across four representative subjects. For each subject, a single voxel time series (identified with a green cross in the first column) was selected from a ventral horn and a dorsal horn, and significant correlations (p < 0.0001) throughout gray and white matter were overlaid onto the high-resolution image. The second column displays correlations for the same seed regions but using functional data from the second resting state run. To visualize changes in spatial correlation patterns caused by the inclusion of higher frequencies, these 16 single-voxel correlation analyses were repeated after resting state runs are were re-filtered using a bandpass filter from 0.01 to 0.13 Hz. The results from these analyses are illustrated in the third and fourth columns.

A qualitative assessment across subjects and frequency bandwidths shows reasonable to very good reproducibility of resting state motor and sensory networks from one run to the next. In general, positive bilateral correlations between ventral horns are prominent and observed across the vast majority of slices, whereas reproducible bilateral correlations between dorsal horns are less prominent but still observed across subjects. Correlations between left and right gray matter horns are often focal and typically do not extend into adjacent white matter, although some correlations include the gray matter bridge (e.g., Figure 4, subject 3, run 1, ventral horns) and other correlations are more diffuse and include adjacent white matter (e.g., Figure 4, subject 3, 0.01–0.08 Hz, run 2, dorsal horns). Comparisons of the preceding group analyses (i.e., Figure 2A vs. Figure 3A and Figure 2B vs. Figure 3B) show that including frequencies from 0.08 to 0.13 Hz results in a group-wise increase in z-scores within the center of gray matter horns, although it is not clear how this increase affects the spatial extent of positive (and possibly negative) correlations when analyzing individual resting state runs. In single-subject analyses, there is evidence that positive spatial correlations can both increase slightly (e.g., Figure 4, subject 3, run 2, ventral horns, 0.01–0.08 Hz vs. 0.01–0.13 Hz) or become more focal (e.g., Figure 4, subject 4, run 2, ventral horns, 0.01–0.08 Hz vs. 0.01–0.13 Hz; Figure 4, subject 2, run 1, ventral horns, 0.01–0.08 Hz vs. 0.01–0.13 Hz; and Figure 4, subject 1, run 1, dorsal horns, 0.01–0.08 Hz vs. 0.01–0.13 Hz). The inclusion of frequencies up to 0.13 Hz may also decrease possibly artifactual negative correlations that manifest along the edge of the cord (caused by step #13, as explored in previous supplementary analyses (Barry et al., 2014)). To further investigate the reproducibility of single-subject functional connectivity between consecutive runs, Figure 5 presents ventral horn correlation maps for 16 additional subjects using resting state data filtered between 0.01 and 0.13 Hz. For each pair of images, the seed region is selected within the approximate center of a ventral horn. The extent and location of positive gray matter correlations exhibit differences from one subject to the next, which may be analogous to differences in sensitivity between subjects and/or selected seed regions in resting state networks in the brain, but overall the most significant and reproducible positive correlations are observed within the gray matter horns, and secondary correlations (both positive and negative) are less reproducible between runs.

DISCUSSION

The translation of resting state functional connectivity from the brain to the spinal cord is a very recent development (Barry et al., 2014; Kong et al., 2014) that is methodologically challenging given the small size of the cord, close proximity to large vertebral bones and pulsating cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and propensity for contamination by magnetic field fluctuations due to respiration, swallowing, and cardiac pulsatility. At 7 Tesla, the confounds of physiological noise, geometric distortions, and suboptimal shimming are particularly problematic, and thus it is important to establish the expected reproducibility of functional connectivity measurements given these challenging circumstances.

Our current analyses suggest a moderate level of reproducibility (ICC ≈ 0.54–0.56) in both motor and sensory resting state spinal cord networks. In quantifying the reproducibility of bilateral motor and unilateral sensory networks at 3 Tesla, Kong et al. reported that approximately half of the voxels within the independent component analysis components of interest had fair reliability (ICC > 0.4) and one-quarter of the voxels had good reliability (ICCs > 0.6) (Kong et al., 2014). Although we cannot directly compare ICC values between our current study and Kong et al.’s study, both studies agree that bilateral ventral horn networks exhibit a moderate level of reproducibility. In previous studies that image the cerebrum, measurements of reliability for brain connectivity have ranged widely depending upon details of the methods used and the connectivity measures considered. For example, a wide range of ICC from 0 to 0.763 was observed in the brain for various approaches to preprocessing and filtering (Braun et al., 2012). Other studies have reported moderate to high within-subject reliability (Pearson correlation) between 0.38 and 0.69 (Honey et al., 2009) and between 0.71 and 0.85 (Van Dijk et al., 2010), which similarly reflect the specific procedures and measures used. These ranges suggest that resting state brain networks can be highly reproducible under ideal conditions, but can also have low reproducibility when sub-optimal preprocessing choices are made. The small size of the cord and inherent imaging challenges (physiological noise, B0 inhomogeneities, etc.) suggest that measurements of spinal cord networks may in practice have slightly lower reproducibility than resting state networks in the brain, or that they are inherently more variable across time. It is not yet clear whether increases in the reproducibility of our measurements of spinal cord networks may be achieved by improved acquisition strategies that provide higher temporal signal-to-noise and/or enhanced preprocessing methodologies.

The group analyses combined data from all slices and all subjects (i.e., 23 subjects × 12 slices/subject = 276 points) to estimate the mean within-slice z-scores and group-level ICCs. This approach presents two minor concerns: (1) these 276 z-score pairs are not all independent, and (2) by including data from all slices, we are also including data irreparably impacted by signal drop-out or artifacts. With regards to the first point, the primary goal of these analyses is to adequately characterize cervical spinal cord functional connectivity within a given axial slice, which may include the mean, range/distribution, and reproducibility. If we collapsed such metrics across slices for each subject (as was done in our previous report) then we would consider only the median values for each subject and discard information about the range and overall distribution. We posit that future clinical investigations that use spinal cord connectivity will focus, at least initially, on motor or sensory network dysfunction within a few axial slices that contain visible lesions or injuries to the cord, and thus an understanding of the range and distribution of these measurements in healthy individuals is crucial for making inferences about possible changes to these networks in patient cohorts or individual subjects. With regards to the second point, we included data from all slices because there is currently no objective way to exclude certain slices a priori because, as an example, an artifact may come close to the dorsal horns (as illustrated via Figure 2 in Barry et al., 2014) but not actually impede the measurement of sensory network connectivity in that slice. Ideally, one would establish objective measures to exclude certain slices or runs (e.g., fMRI in the brain may exclude a functional run if the motion correction algorithm estimates that the translation exceeds ~5 mm in any direction) and then filter the data (i.e., exclude certain time points, individual slices, or entire runs) according to these measures before calculating the functional connectivity or ICC. Therefore, our study may have slightly underestimated the reproducibility of within-slice correlations, and future work can investigate objective measures to establish robust data quality control.

The anatomical variability of the spinal cord (Cadotte et al., 2015), and particularly the shape and extent of the dorsal horns across axial slices and subjects, makes accurate group alignments extremely challenging. For the majority of fMRI studies in the brain, an occasional mis-alignment of 1–2 mm between certain functional datasets and a target template would probably not impact the findings of the group analysis to a significant degree, but a misalignment of 1–2 mm in the spinal cord would significantly impact a group analysis of small structures because the gray matter horns are on the order of 1–2 mm in size. Our approach to performing single-subject correlation analyses obviated the challenges of group alignments and registration errors by keeping data from each subject in its own native space, and may in part explain why we observed bilateral sensory networks in our previous paper as well as the current reproducibility study. Furthermore, the scatterplots for dorsal horn connectivity (Figure 2B and Figure 3B) display approximately half the number of z-score pairs with z > 4 compared to ventral horn connectivity, but still an order of magnitude more z > 4 correlations compared to the ventral-dorsal correlations, supporting the hypothesis that dorsal horn connectivity is an inherently weaker phenomenon. Our observation of reproducible bilateral sensory networks may reflect commissural propriospinal connections between dorsal horns (Petkó and Antal, 2012), but ultimately, further research is required to better understand the nature of spinal cord sensory networks. Furthermore, although bilateral motor and sensory networks are clearly visualized in these data, future work should continue to investigate the possible manifestation of resting state functional connectivity between ventral and dorsal horns (e.g., Supplementary Figure S2), which has been observed in squirrel monkeys (Chen et al., 2015) and may also exist in humans to a lesser, or perhaps intermittent, degree. As the field of spinal cord fMRI continues to develop and grow, it will become increasingly important to recognize the significant inter-subject variability of spinal and vertebral levels (Cadotte et al., 2015) and convert data into a group space using robust templates adopted by the community. Therefore, our future work will also investigate the use of de novo templates for spinal cord imaging (Fonov et al., 2014).

Another challenge with imaging the cord is that even if the registration of a functional image to its corresponding high-resolution anatomical (step #9) was optimal, a mis-alignment between the anatomically-derived gray matter mask and the underlying functional data is still possible due to geometric distortions in the functional runs. Furthermore, these geometric distortions are likely to be at least slightly different between the two functional runs, which is a serious confound when measuring reproducibility. To address this problem, we acquired our data using a multi-shot gradient echo technique that produces images with markedly less distortion than, for example, single-shot echo planar sequences (Barry et al., 2011). We then developed a modified approach to measuring temporal correlations between gray matter horns. The eroded sub-region masks (step #15) were dilated slightly, by a single interpolated pixel (0.31 × 0.31 mm2), to acknowledge the fact that there is a degree of unavoidable anatomical uncertainty within each mask. Then, the calculation of all correlation pairs between the two gray matter regions was performed to compute a metric of functional connectivity that is more robust against geometric distortions and partial volume effects — and the fact that the exact locations of correlated resting state BOLD signal fluctuations are unknown (they appear to be in the approximate center of the gray matter horns on many, but not all, slices as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5). In a scenario where the regions of correlated signal BOLD fluctuations are relatively large and homogeneous and include all voxels in the sub-region masks (e.g., Figure 4, subject 3, run 1, ventral horns), then selecting the 95% percentile of all possible correlation pairs would produce a result similar to the correlation coefficient between the average time courses of each region (as was done in our previous paper). However, if one of the focal regions of correlated BOLD signal changes was smaller (e.g., Figure 4, subject 2, run 1, ventral horns) and/or slightly away from the apparent center of the gray matter horn due to geometric distortions or sub-millimeter registration inaccuracies (e.g., Figure 4, subject 2, run 1, dorsal horns), then our approach should have a higher likelihood of extracting a reasonable measure of functional connectivity. Future work will continue to improve our approaches to accurately characterize resting state connectivity in the presence of sub-millimeter geometric distortions and/or registration inaccuracies.

This study quantified intra-session reproducibility to estimate an upper bound on the ICCs for spinal cord connectivity. Other investigations of reproducibility could include intra-session with subject replacement (subjects exit and then re-enter the scanner to incorporate variability associated with slice planning and shimming) and inter-session (subjects are scanned on a different day that could be weeks or months later). Future work may re-scan participants from this study to quantify inter-session reproducibility of healthy subjects, and knowledge of both intra- and inter-session reproducibility in a healthy cohort of subjects with no history of spinal cord disease would be of paramount importance for clinical studies that consider metrics of spinal cord functional connectivity as potential biomarkers of functional recovery or integrity.

Finally, the secondary goal of this report was to investigate the inclusion of resting state frequencies above 0.08 Hz because any bandpass filter cutoff is arbitrary and it is important to investigate how different cutoffs affect the results. Although the majority of resting state studies in the brain filter fMRI data from 0.01 to 0.08–0.1 Hz (following the methods of the original 1995 resting state study (Biswal et al., 1995)), more recent investigations have explored frequency bands up to 0.5 Hz (Chen and Glover, 2015) or 0.75 Hz (Gohel and Biswal, 2015) and found that useful power related to functional connectivity exists at higher frequencies. Indeed, our comparisons of spinal cord connectivity using different frequency bands showed that correlation analyses using frequencies from 0.01 to 0.13 Hz (Figure 3) resulted in a group-wise increase in z-scores within the center of gray matter horns compared to the same correlation analyses using the traditional range of frequencies from 0.01 to 0.08 Hz (Figure 2). Furthermore, in single-subject analyses (Figure 4), there is evidence that for the same statistical threshold (p < 0.0001), the higher frequencies may result in more focal positive correlations within the gray matter horns and suppress doubtful negative correlations with regions outside the gray matter butterfly. These results are encouraging, and suggest that future studies of functional connectivity in the spinal cord should consider frequencies above the conventional 0.08 Hz.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants 5K99EB016689-02 and 5R21NS081437-02. The project was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources, grant UL1RR024975-01, which is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant 2UL1TR000445-06. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barry RL, Smith SA, Dula AN, Gore JC. Resting state functional connectivity in the human spinal cord. Elife. 2014;3:e02812. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry RL, Strother SC, Gatenby JC, Gore JC. Data-driven optimization and evaluation of 2D EPI and 3D PRESTO for BOLD fMRI at 7 Tesla: I. Focal coverage Neuroimage. 2011;55:1034–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.12.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun U, Plichta MM, Esslinger C, Sauer C, Haddad L, Grimm O, … Meyer-Lindenberg A. Test-retest reliability of resting-state connectivity network characteristics using fMRI and graph theoretical measures. Neuroimage. 2012;59:1404–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadotte DW, Cadotte A, Cohen-Adad J, Fleet D, Livne M, Wilson JR, … Fehlings MG. Characterizing the location of spinal and vertebral levels in the human cervical spinal cord. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:803–810. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JE, Glover GH. BOLD fractional contribution to resting-state functional connectivity above 0.1 Hz. Neuroimage. 2015;107:207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LM, Mishra A, Yang PF, Wang F, Gore JC. Injury alters intrinsic functional connectivity within the primate spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:5991–5996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424106112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29:162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eippert F, Tracey I. The spinal cord is never at rest. Elife. 2014;3:e03811. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonov VS, Le Troter A, Taso M, De Leener B, Lévêque G, Benhamou M, … Cohen-Adad J. Framework for integrated MRI average of the spinal cord white and gray matter: the MNI-Poly-AMU template. Neuroimage. 2014;102:817–827. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gati JS, Menon RS, Uğurbil K, Rutt BK. Experimental determination of the BOLD field strength dependence in vessels and tissue. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38:296–302. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover GH, Li TQ, Ress D. Image-based method for retrospective correction of physiological motion effects in fMRI: RETROICOR. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:162–167. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200007)44:1<162::aid-mrm23>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohel SR, Biswal BB. Functional integration between brain regions at rest occurs in multiple-frequency bands. Brain Connect. 2015;5:23–34. doi: 10.1089/brain.2013.0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey CJ, Sporns O, Cammoun L, Gigandet X, Thiran JP, Meuli R, Hagmann P. Predicting human resting-state functional connectivity from structural connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2035–2040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811168106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y, Eippert F, Beckmann CF, Andersson J, Finsterbusch J, Büchel C, … Brooks JCW. Intrinsically organized resting state networks in the human spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:18067–18072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414293111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Menon RS, Tank DW, Kim SG, Merkle H, Ellermann JM, Uğurbil K. Functional brain mapping by blood oxygenation level-dependent contrast magnetic resonance imaging. A comparison of signal characteristics with a biophysical model. Biophys J. 1993;64:803–812. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81441-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkó M, Antal M. Propriospinal pathways in the dorsal horn (laminae I IV) of the rat lumbar spinal cord. Brain Res Bull. 2012;89:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P. SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:952–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers BP, Gore JC. Empirical comparison of sources of variation for FMRI connectivity analysis. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk KRA, Hedden T, Venkataraman A, Evans KC, Lazar SW, Buckner RL. Intrinsic functional connectivity as a tool for human connectomics: theory, properties, and optimization. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:297–321. doi: 10.1152/jn.00783.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.