Abstract

Semidwarfism is an important agronomic trait in rice breeding programs. The semidwarf mutant gene Sdt97 was previously described. However, the molecular mechanism underlying the mutant is yet to be elucidated. In this study, we identified the mutant gene by a map-based cloning method. Using a residual heterozygous line (RHL) population, Sdt97 was mapped to the long arm of chromosome 6 in the interval of nearly 60 kb between STS marker N6 and SNP marker N16 within the PAC clone P0453H04. Sequencing of the candidate genes in the target region revealed that a base transversion from G to C occurred in the 5′ untranslated region of Sdt97. qRT-PCR results confirmed that the transversion induced an obvious change in the expression pattern of Sdt97 at different growth and developmental stages. Plants transgenic for Sdt97 resulted in the restoration of semidwarfism of the mutant phenotype, or displayed a greater dwarf phenotype than the mutant. Our results indicate that a point mutation in the 5′ untranslated region of Sdt97 confers semidwarfism in rice. Functional analysis of Sdt97 will open a new field of study for rice semidwarfism, and also expand our knowledge of the molecular mechanism of semidwarfism in rice.

Keywords: semidwarfism, Sdt97, transversion, map-based cloning, qRT-PCR, complement test, rice (Oryza sativa L.)

Dwarfism is one of the most important agronomic traits of rice. The introduction of high-yielding dwarf cultivars, together with the application of large amounts of fertilizer and pesticides—termed the ‘Green Revolution’—has contributed substantially to the significant increase in rice production, and largely averted the chronic food shortage that was feared after the rapid expansion of the world population in the 1960s (Khush 2001; Sasaki et al. 2002; Hedden 2003; Muangprom and Osborn 2004).

Utilization of dwarf rice cultivars was one of the greatest achievements in rice breeding in the 20th century. Before the introduction of the dwarf gene to rice improvement programs, rice cultivars were all tall; the stems of tall rice plants were not strong enough to support the heavy grain of the high-yielding varieties, and this resulted in plants falling over. This process, known as lodging, resulted in large yield losses (Hedden 2003).

Semidwarf plants possess short, strong stalks, exhibit less lodging, and a greater proportion of assimilation partitioned into the grain, resulting in further yield increases (Hedden 2003). Reducing plant height to breed high-yielding, nonlodging, rice varieties has become a predominant strategy for breeders since the 1960s (Hargrove and Cabanilla 1979). Dwarf genes have been utilized extensively in plant breeding to improve lodging resistance (Khush 2001; Sasaki et al. 2002).

The dwarfing gene originated from a Chinese cultivar, Dee-geo-woo-gen, which was used in a breeding program in Taiwan during the 1950s to produce the highly successful Taichung Native 1. This cultivar was also used later at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines to produce IR-8. Semidwarf, high-yielding cultivars have also been produced independently in the People’s Republic of China, Japan and the USA. The semidwarf trait can be attributed to the different alleles of a single recessive gene, sd1, even where the parent strains have been selected or produced independently (Hedden 2003; Sasaki et al. 2002; Kikuchi and Futsuhara 1997).

In previous research, we isolated a dominant semidwarf mutant gene Sdt97 (Tong et al. 2007). In this article, we report current progress in the molecular cloning of Sdt97.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Plant materials used in this study are the semidwarf mutant (Y98149), the tall wild type (Y98148), Huajingxian74, an elite indica variety, F7 residual heterozygous lines (RHL), and F7:8 residual heterozygous lines (RHL). Y98149 was isolated originally from an F6 generation nursery selection of a medium japonica rice cross between M9056 and R8018 Xuan. Y98149 and Y98148 are near isogenic lines (NIL) (Tong et al. 2003).

Field trials were carried out on paddy fields in two locations. (1) During the natural rice growing seasons in Hefei in 2006, Y98149, Y98148, Huajingxian74, and F7 RHL were planted at the Experimental Station at Hefei (31 × N, 117 × E), Anhui province, China. Seeds were sown in seed beds on April 15–20, 2006. On June 15–20, 1-month old seedlings were transferred to the paddy field for further growth. (2) During the natural early rice growing seasons in Sanya in 2006–2007, Y98149, Y98148, Hua jingxian74, and F7:8 RHL were planted in the field at experimental stations at Sanya (18 × N, 109 × E), Hainan province, China. Seeds were sown in seed beds on November 15–20, 2006. On December 15–20, 2006, 1-month old seedlings were transferred to the paddy field for further growth.

The planting density was 13.3 cm between plants in a row, and the rows were 16.7 cm apart. Field management, including irrigation, fertilizer application, and pest control, followed normal agricultural practice.

Phenotypical characterization and genetic analysis

In this research, plant heights were recorded at maturity in the paddy field. Plant height was measured from ground level to the plant material tassel tip. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test. Probability values (P) 0.05 were considered significant. Segregation of plant height phenotype in RHL segregated progenies was analyzed for goodness of fit in the ratio of 3:1 using a Chi-square test (χ2 < χ2 0.05, 1 = 3.84). Each quantitative real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed for three biological replicates. The ΔΔCt method was used for data analysis.

Mapping population development

An intersubspecific cross between semidwarf mutant Y98149 (japonica cv.) and Hua- jing-xian74 (indica cv.) was developed for the Sdt97 mapping. A F6 recombinant inbred line population (RIL) was identified to be a RHL, and was used in the rough mapping of Sdt97 (Tuinstra et al. 1997; Yamanaka et al. 2005; Tong et al. 2007).

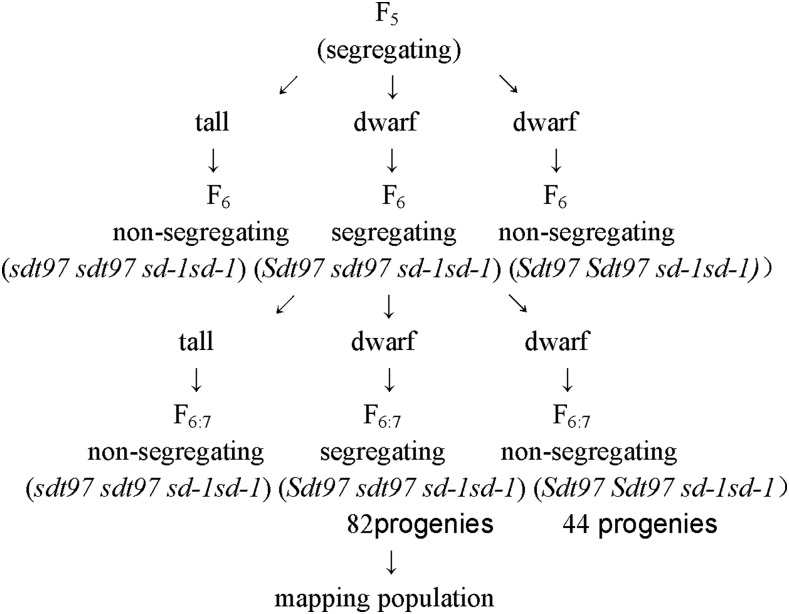

In the fine mapping study of Sdt97, a large scale F7 RIL population was constructed. Out of this segregating F7 RHL population, F7 recessive tall individuals were selected for the fine mapping of Sdt97. For the genetic validation, or progeny testing of the recessive F7 individuals, F7:8 RHL derived from these tall F7 recessive individuals were further planted in the field at experiment stations in Sanya (18 × N, 109 × E), Hainan province, China. The developmental process of the RHL population was as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Development of the RHL mapping population.

DNA extraction and molecular marker development

Fresh leaves were collected and ground in liquid nitrogen. DNA was extracted from the ground tissues using the modified CTAB (celytrimethyl ammonium bromide) method (Rogers and Bendich 1998).

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) markers were developed by sequencing the PCR products amplified from japonica cv. semidwarf mutant Y98149, and Indica cv. Huajingxian74 in the rough mapping region of Sdt97. PCR products were cloned into the vector pGEM-T (Promega, USA) for sequencing, and for developing SNPs. PCR amplifications followed the profile: 94° for 3 min, 35 cycles of 94° for 1 min, 55° for 1 min and 72° for 1 min, with a final extension of 72° for 5 min. The markers, which showed polymorphism between Y98149 and Huajingxian74, were then utilized for Sdt97 fine mapping.

The LightCycler480 Real-Time PCR System was employed for SNP Genotyping. PCR amplification was performed in a 96-well plate in the LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System. Reaction volume was 10 μl; 2 μl of genomic DNA (10 ng/μl) was added to 8 μl of the reaction master mixture consisting of 1× LightCycler 480 High Resolution Melting Master (containing the proprietary ds-DNA saturating binding dye), with 2.5 mM MgCl2 (Roche Diagnostics, Germany), and 0.5 μM of forward and reverse primers. The PCR program started with an initial denaturation of 10 min at 95°, and continued with 40 cycles of 10 sec at 95°, 15 sec at 60°, and 10 sec at 72°. For high resolution melting (HRM), the plate was heated from 65° to 95°, performing 25 acquisitions per 1° (Norambuena et al. 2009).

Map-based cloning

Using the RHL, Sdt97 was mapped to a 118-kb region on chromosome 6 flanked by two STS markers, N6 and TX5(Tong et al. 2003). Bulked segregant analysis (BSA) (Michelmore et al. 1991) combined with recessive class analysis (RCA) (Chen et al. 2005; Pan et al. 2003; Zhu et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 1994) were used to identify molecular markers linked to the mutant gene Sdt97 in the fine mapping of Sdt97. Genomic DNA from 30 tall individuals and 30 dwarf individuals in the F6:7 segregated progenies were pooled to create the tall and dwarf DNA bulks, respectively. The parental DNA, and the two bulks, were used for BSA. Polymorphic markers from the two parents were screened against the two DNA bulks, and polymorphic markers between the two DNA bulks were screened against the entire population of tall recessive individuals in the F6:7 segregated population.

Using the markers developed in this research, the mutant gene Sdt97 was finally mapped, the candidate genes detected in the target region were PCR-amplified and sequenced for mutation detection. The average length of the PCR products was 1.5 kb, and the PCR products were sequenced directly.

RNA manipulation and qRT-PCR analysis

To analyze the expression pattern of Sdt97 carried by the semidwarf mutant Y98149, sdt97 carried by tall wild-type Y98148, and the gene expression of Sdt97 in transgenic lines, samples were prepared from Y98149, Y98148, and the transgenic T1 lines of F4 plants at seedling stage, tillering stage, elongation stage, and milk ripe stage, respectively.

Fresh plant tissues of above-ground rice were harvested, and immediately ground to fine powder in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The TransScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (TransGen Biotech) were used to synthesize cDNA using an anchored oligo(dT)18 primer according to the kit instructions.

qRT-PCR (20 μl reaction volume) was carried out using 0.5 μl cDNA, 0.2 μl of each gene-specific primer, and SYBR Premix Ex Taq Kit (TaKaRa) in a LightCycler Real Time PCR according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reaction conditions were 95° for 30 sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95° for 5 sec, and 60° for 31 sec. The standard procedure for melt curve analysis followed the amplification cycles. The rice actin gene was used as the endogenous control for normalization. Each real-time PCR analysis was performed for three biological replicates. The relative quantification method (ΔΔCt) was used for data analysis.

The gene-specific primers used for qRT-PCR are as follows: Sdt97-specific Q1 (forward primer: GTCCGGTCGCTGAACGTG; reverse primer: GGCTTCGGCGAGGGCTT), located in the first exon coding section of Sdt97; the expected length of the qRT-PCR product was 113 bp. Sdt97-specific Q2 (forward primer: CATGTGGAACAGTGATGCGG; reverse primer: AACTGG GTTGCATTACTGACACA), located towards the end of the noncoding cDNA section of Sdt97; the expected length of qRT-PCR product was 136 bp. Actin-specific (LOC_Os03g61970) (forward primer: ATCCTTGTATGCTAGCGGTCGA; reverse primer: ATCCAACCGGAGGATAGCATG).

Vector constructions and plant transformation

To confirm further that the mutated traits were caused by mutant gene Sdt97, we constructed transgenic plants for the complement test of Sdt97. The Gateway cloning system was adopted, and the Gateway vector pGWB12:[(35S promoter,N-FLAG) (–35S promoter-FLAG-R1-CmR-ccdB- R2–)] (Invitrogen) was used for the Sdt97 complementarity test. We wanted to test the effect of the point mutation in the 5′ untranslated region (5′-UTR) on the gene expression of Sdt97 itself. Considering that the point mutation in the 5′-UTR may be associated with the promoter of Sdt97, perhaps the point mutation in the 5′-UTR is part of the promoter itself, thus pGWB3: [(no promoter, C-GUS) (-R1- CmR-ccdB-R2-GUS -)] (Invitrogen nomenclature), a no promoter Gateway vector, was also used in the complementary test of Sdt97.

Two Sdt97 genomic DNA fragments were amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA using the following primers: BF1: GTGGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCA GGCTTCCCTCTCCTCTCCTCTCACCACC, BR1: GTGGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCTGTTAACTGATTGAGGAAGATTTTTCA, BF2: GTGGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTCGTGAGATAATGCCGGGCCC, and BR2: GTGGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCAGGTATCCTGCAGTTCTGCATG. A 2701-bp genomic DNA fragment containing the entire Sdt97, and a 3116-bp genomic DNA fragment containing the entire Sdt97, the 174 bp 5′ upstream sequence and the 243 bp 3′ downstream sequence, were amplified with high fidelity using KOD-Plus-Neo (TOYOBO, Japan). The PCR amplification products were mixed with Donor vectors (Invitrogen nomenclature) and BP Clonase enzyme mix to construct an Entry clone. Then, the Entry clone was transferred into the Gateway vector using the enzyme mix, and LR Clonase to construct the Expression clone. The expression clone was constructed from the 3116-bp PCR product and pGWB12, and was designated as F4. The expression clones constructed from the 2701 bp and 3116 bp PCR products and pGWB3 were named T6 andT15, respectively. The expression clone was introduced into the Agrobacterium strain EHA105 by electroporation, and transformation was carried out as described (Hiei et al. 1994; Xue et al. 2008).

Positive transgenic plants were detected by sequencing the PCR products of the genomic DNA using a pair of primers (forward primer: CCTCTCCTCTCCTCTCACCACC; reverse primer:TAATCCCAGCCCAGGGTTCG) designed according to the sequence mutation at the promoter region. The PCR products were 223 bp, and it was easy to separate the transgenic plants from that of transgenic acceptors line or tall wild type plants. Transgenic lines were selected using hygromycin treatment (15 mg L–1).The transgenic rice plants were transferred to and grown in experimental fields from January to April in Sanya, Hainan Province, and from May to October in Hefei Anhui Province China 2014.

Data availability

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article.

Results

Isolation and phenotypic characterization of the semidwarf mutant

In 1997, a semidwarf mutant was isolated from the tall F6 progenies derived from the cross between M9056 and R8018 XUAN (Tong et al. 2001). The semidwarf mutant was deduced to result from a spontaneous mutation, and not from the cross-fertilization between the tall wild type and other dwarf rice cultivars (Tong et al. 2003). It is the NIL to the tall wild type in the same selected nursery, the semidwarf mutant was named Y98149, and the tall wild type was named Y98148 (Tong et al. 2003).

The length of each internode of the mutant is almost uniformly shortened, resulting in an elongation pattern similar to that of the wild-type plant (Table 1). According to the grouping of rice dwarf cultivars proposed by Takahashi, the semidwarf mutant belongs to the dn-type (Takahashi et al.and Takeda 1969).

Table 1. Plant height, panicle, and elongate internode length of semidwarf mutant and tall wild type.

| Item | Semidwarf Mutant | Tall Wild Type | Percentage Decrease (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant height | 75.87 ± 4.55 | 104.63 ± 4.68 | −27.49* |

| Panicle length | 27.12 ± 2.44 | 28.69 ± 2.17 | −5.47 |

| Length of the first internode under panicle | 17.95 ± 1.67 | 20.34 ± 1.62 | −11.75* |

| Length of the second internode under panicle | 24.21 ± 2.37 | 30.48 ± 2.72 | −20.57* |

| Length of the third internode under panicle | 12.09 ± 1.22 | 19.44 ± 1.48 | −37.81* |

| Length of the fourth internode under panicle | 7.37 ± 0.89 | 12.10 ± 1.48 | −39.09* |

| Length of the fifth internode under panicle | 5.88 ± 1.05 | 8.98 ± 0.97 | −34.52* |

| Length of the sixth internode under panicle | 2.96 ± 1.17 | 4.82 ± 1.27 | −38.59* |

| Length of the seventh internode under panicle | 0.90 ± 1.16 | 1.61 ± 2.37 | −44.10 |

| Length of the eighth internode under panicle | 0.21 ± 0.80 | 0.27 ± 0.75 | −22.22 |

| Length of the ninth internode under panicle | 0.07 ± 0.29 | 0.10 ± 0.42 | −30.00 |

Significance at P < 0.01 level; statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test.

Research into the genetic character of the semidwarf mutant revealed that there was only one dominant gene locus involved in the control of the semidwarfism, and the semidwarfism expression of the mutant was not affected by its cytoplasm (Figure 2). The results of classic genetic allelic tests revealed that the semidwarf mutant gene is a new kind of semidwarf gene reported in rice; the mutant gene was temporarily designated Sdt97 (Tong et al. 2003, et al. 2007).

Figure 2.

Tall wide type (WT), semidwarf mutant (M), and the F1 progeny derived from reciprocal crosses between M and WT [from right to left: WT, M, (WT/M)F1, (M/WT)F1].

RHL population development

For the sdt97 mapping, an intersubspecific cross between semidwarf mutant Y98149 (japonica cv.) and Hua-jing-xian74 (indica cv.) was developed. A F6 recombinant inbred line population (RIL), which originated from the intersubspecific cross, was identified as an RHL (Yamanaka et al. 2005; Tuinstra et al. 1997; Tong et al. 2007). The heterozygous chromosomal region is approximately 25.5 cM and 6646 kb, starting from RM3430 and ending at RM6395. This was initiated by different parents, one carrying the Sdt97 gene derived from the mutant, and the other carrying the sdt97 gene derived from Hua-jing-xian74 (Table 2). This F6 residual heterozygous lines population was used in the rough mapping of Sdt97, and the semidwarf mutant gene Sdt97 was mapped on the long arm of chromosome 6 at the interval between two STS markers N6 and TX5, with a genetic distance of 0.2 cM and 0.8 cM, respectively (Tong et al. 2007).

Table 2. Constituents of chromosome 6 of the RHL.

| Marker Name | Gene-Typea | Location (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| RM8019 | AA | 485930–486040 |

| RM589 | AA | 1380876–1381023 |

| RM588 | AA | 1611413–1611510 |

| RM190 | AA | 1764638–1764760 |

| RM225 | AA | 3416596–3416728 |

| RM584 | AA | 3416595–34516764 |

| RM253 | aa | 5425498–5425631 |

| RM276 | aa | 6230045–6230185 |

| RM4128 | aa | 6644518–6644658 |

| RM6836 | aa | 9308941–9309108 |

| RM3330 | AA | 11064158–11064302 |

| RM3183 | AA | 12447059–12447198 |

| RM1161 | AA | 13752128–13752207 |

| RM3187 | AA | 20925773–20925914 |

| RM4447 | AA | 22679594–22679732 |

| RM1340 | AA | 23343196–23343361 |

| RM3628 | AA | 23737084–23737180 |

| RM7434 | AA | 23934836–23934978 |

| RM162 | AA | 24035491–24035615 |

| RM275 | AA | 24324733–24324821 |

| RM5957 | Aa | 24521524–24521700 |

| RM5314 | Aa | 24842804–24842954 |

| RM5371 | Aa | 25825428–25825525 |

| RM6395 | Aa | 25995534–25995643 |

| RM3430 | Aa | 27432606–27432761 |

| RM5509 | Aa | 27828211–27828465 |

| RM3183 | Aa | 28469084–28469188 |

| RM340 | Aa | 28599182–28599297 |

| RM3509 | aa | 30970997–30971169 |

A means allele originates from Y98149; a means allele originates from Hua-jing- xian74.

A contig map was constructed based on the reference sequence aligned by the Sdt97 linked markers, and the mutant Sdt97 locus was defined to a 118-kb interval within the PAC clone P0453H04 (Sequence ID:dbj|AP005453.1| length: 175,047 bp) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

In the F6:7 progenies, 44 populations derived from homozygous dwarf F6 individuals, exhibited dwarf nonsegregation; 82 populations derived from heterozygote dwarf F6 individuals showed continued plant height segregation, and resulted in both tall and dwarf individuals (Figure 3). The ratio of the segregating F6:7 progenies to the nonsegregating dwarf F6:7 progenies is 1.86, which fits the expected Mendelian segregated ratio of 2:1 (χ2 = 0.081, P > 0.05). The results confirmed that there was only one dominant gene controlling the segregation of plant height in the RHL population.

Figure 3.

Plant height segregation mode of the F6:7 progenies derived from RHLs.

A large scale F7 RIL population, consisting of 10,000 F7 individuals, was constructed. Of these segregating F7 RHL plants, 2328 F7 tall recessive individuals were selected for the fine mapping of Sdt97 using the RCA method (Figure 4, Tuinstra et al. 1997; Yamanaka et al. 2005; Tong et al. 2007). For genetic validation or progeny testing of the recessive F7 individuals, 2328 F7:8 RHL derived from these tall F7 recessive individuals were further planted in the field at the experimental stations in Sanya (18 × N, 109 × E), Hainan province, China. A total of 2312 of them, which passed progeny testing, was further used for the fine mapping of Sdt97 in this study.

Figure 4.

Semidwarf plants and dwarf plants in the RHL mapping population of segregated F6:7 progenies.

Fine mapping of Sdt97

Upon further linkage analysis, one cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (dCAPS) (BamHI), and 16 SNP markers were developed by sequencing the PCR products amplified from Y98149 and Huajingxian74 in the target region (Supplemental Material, File S1). Depending on sequence variation, different SNP genotype of the recessive individuals in the F6:7 populations be differentiated (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

PCR products were amplified with SNP marker N16 from tall recessive individuals in the segregating F6:7 populations, and analyzed by high-resolution-melting (HRM). Three types of HRM curves were obtained: curve A represents homozygous Y98149, curve B represents homozygous Hua-jing-xian74, and curve C represents heterozygous RHL.

A total of 2312 tall recessive individuals in the 86 F6:7 segregated population was used. By analyzing BSA and RCA, 33 distinct recombinants were identified in the target region. Using one dCAPS marker (BamHI), and 16 new SNP markers developed in this research, the Sdt97 gene was further mapped to the long arm of chromosome 6 at the interval of nearly 60 kb between STS markers N6 and SNP marker N16 within the PAC clone P0453H04 (Sequence ID: dbj|AP005453.1 |length: 175,047 bp). The sequence of primers N6 and N16, and their location on the PAC clone P0453H04, are as shown in Table 3 (see http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Table 3. The sequences of primers N6 and N16, and their location on P0453H04.

| Marker | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Location on P0543H04 |

|---|---|---|---|

| N6 | GCCGGGGAGCTACTACCGAG | CACTGATTCAGCTCCCAAGGC | 36129 bp–36327 bp |

| N16 | GGGATAGATGCCTTCCATTGTT | CGAGTAGGAAGTGCCTCTAGCG | 96547 bp–96761 bp |

Map-based cloning of the Sdt97 gene

Based on the available sequence annotation database (http://www.gramene.org/;http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/index.shtml), nine genes were predicted in the 60 kb target region of the cultivated rice genome. To identify the candidate gene of Sdt97, the genomic DNA sequence of all nine predicted genes in the 60 kb target region were sequenced. Based on the sequence analysis, nine genes could be categorized under three headings (Table 4).

Table 4. The information and sequence alignment of the genes in Y98148, Y98149 in the 60 kb target region.

| Gene | 5′–3′ | Putative Function | Sequence Alignment Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOC_Os06g44040 | 7096–10256 | DOMON domain containing protein, expressed | No difference |

| LOC_Os06g44050 | 13373–16415 | Methyladenine glycosylase, putative, expressed | One base mutation occurred in 5′-UTR region, and 342 bp nucleotide fragment deletion at the CDS region. The mutant base of mutant at the site of 277 bp upstream of initiation codon was C, which in wild type was G |

| LOC_Os06g44060 | 19082–23641 | Phospholipase D.Active site motif family protein, expressed | No difference |

| LOC_Os06g44070 | 25659–27705 | Retrotransposon protein, putative, unclassified | No difference |

| LOC_Os06g44080 | 29517–32089 | Ubiquitin family protein, putative, expressed | No difference |

| LOC_Os06g44090 | 33739–34636 | Hypothetical protein | No difference |

| LOC_Os06g44100 | 35862–37421 | HLS, putative, expressed | No difference |

| LOC_Os06g44120 | 51318–51844 | Retrotransposon protein, putative,Ty3-gypsy,subclass | Multi copy gene(2) |

| LOC_Os06g44130 | 52687–54379 | Retrotransposon protein, putative, unclassified | Multi copy gene(3) |

Note that the 342-bp deletion fragment in LOC_Os06g44050 is observed between Y98149 (or Y98148) and Nipponbare.

There is no DNA sequence difference between the semidwarf mutant and the tall wild type; LOC_Os06g44040, LOC_Os06g44060, LOC_Os06g44070, LOC_Os06g44080, LOC_Os06g44090, and LOC_Os06g440100 were of this type.

Multicopy genes exist in the rice genome; LOC_Os06g44120 and LOC_Os06g44130 were of this type. Two copies of LOC_Os06g44120 [LOC_Os06g44120; LOC_Os12g34630], and three copies of LOC_Os06g44130 [LOC_Os06g44130; LOC_Os03g19150; LOC_ Os10 g08300], are known to exist in the rice genome.

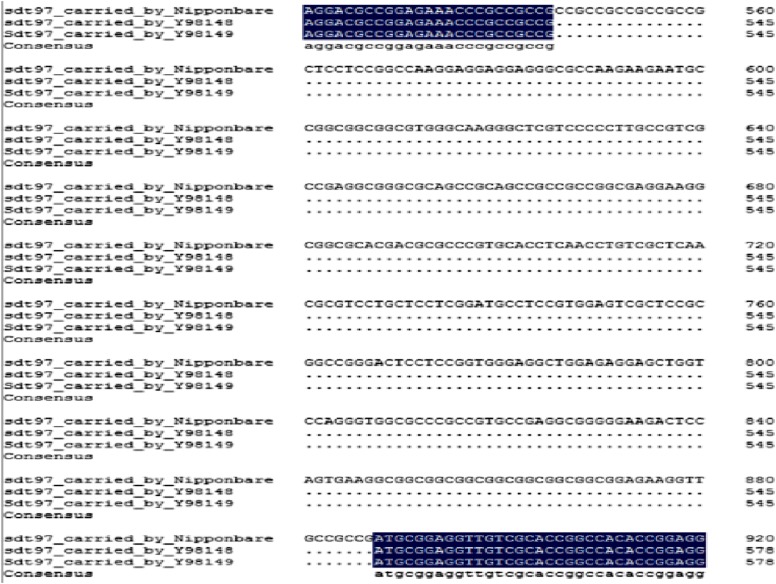

Sequence analysis of genomic DNA fragments of the gene from tall wild-type and the semidwarf mutant showed that a point mutation occurred in the 5′-UTR of LOC_Os06g44050, resulting in a transversion from G to C.

The transversion took place at a site 277 bp upstream of the initiation codon in the 5′-UTR of exon 1 (Figure 6). The mutant base of Sdt97 carried by Y98149 was C, while sdt97 alleles of the same gene occupying the equivalent locus on homologous chromosomes carried by Y98148 had a G in this position (Figure 7). Compared with the genomic DNA sequence of Nipponbare, it was found that not only Y98149, but also Y98148, had a 342-bp deletion in the first coding exon in LOC_ Os06g44 050. The deletion occurred between 546 bp and 887 bp in the genomic sequence, or between 194 bp and 535 bp in the coding sequence (CDS) of LOC_Os06g44050 (Figure 8). Thus, LOC_Os06g44050 was finally identified as the candidate gene of Sdt97.

Figure 6.

Schematic model of Sdt97 gene.

Figure 7.

5′-UTR sequence alignment of Sdt97 carried by mutant, and sdt97 carried by wild type.

Figure 8.

Fragment (342 bp) representing nucleotide deletion of Sdt97 in mutant and sdt97 in wild type.

The genomic DNA and cDNA nucleotide sequences of Sdt97 were 2701 bp and 1517 bp in length, respectively. Sdt97 consisted of five exons and four introns, as follows: 5′-exon 1 [617 bp = 5′-UTR (352 bp) + coding exon 1 (265 bp)]–intron 1 (920 bp)–exon 2 (coding exon 2, 58 bp)–intron 2 (92 bp)–exon 3 (coding exon 3, 84 bp)–intron 3 (79 bp)–exon 4 (coding exon 4, 142 bp)–intron 4 (93 bp)–exon 5 [616 bp = coding exon 5 (396 bp) +3′-UTR (220bps)]–3′ (File S1).

A schematic gene model of Sdt97 is displayed in Figure 6. The DNA and cDNA sequences of Sdt97 and the deletion fragment are provided.

Transversion from G to C in the 5′-UTR of Sdt97 alters the expression pattern

At different stages of growth and development of Y98149 and Y98148, qRT-PCR was applied to analyze the effect of the transversion from G to C in the 5′-UTR of Sdt97 on its own gene expression. The results of qRT-PCR were as follows (Table 5):

Table 5. The relative quantification of Sdt97 (carried by semidwarf mutant Y98149), and sdt97 (carried by tall wild-type Y98148) (NrelM/NrelWT) at different growth stages.

| Item | Seedling Stage | Tillering Stage | Elongation Stage | Milk Ripe Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔCt, Sdt97, carry in Y98149 | −0.65 | −2.42 | −0.58 | −0.97 |

| ΔCt, sdt97, carry in Y98148 | −0.77 | −0.30 | −2.64 | −0.97 |

| ΔΔCt = (ΔCt Sdt97-ΔCtsdt97) | 0.12 | −2.12 | 2.06 | 0 |

| NrelM/NrelWT = 2-ΔΔCt | 0.92 | 4.37 | 0.24 | 1.00 |

At the seedling stage, the ΔΔCt = 0.12, the NrelM/NrelWT = 2–ΔΔCt = 0.92, meaning that the gene expression of Sdt97 in Y98149 was just the same level as that in Y98148.

At the tillering stage, the ΔΔCt = –2.12, the NrelM/NrelWT = 2–ΔΔCt = 4.37, meaning that the gene expression of Sdt97 in Y98149 was four times higher than that of sdt97 in Y98148.

In contrast, at the elongation stage, the ΔΔCt = 2.06, the NrelM/NrelWT = 2–ΔΔCt = 0.24, meaning that the gene expression of sdt97 in Y98148 was four times higher than that of Sdt97 in Y98149.

At the milk ripe stage, the ΔΔCt = 0, the NrelM/NrelWT = 2–ΔΔCt = 1.00, meaning that the gene expression of sdt97 in Y98148 was just the same as, or just more than, Sdt97 in Y98149.

The expression level of the gene Sdt97 in the transgenic lines is very strong supporting evidence for the function of sdt97. In this study, qRT-PCR was applied at different growth stages to analyze the effect of the gene transfer of Sdt97 on the expression pattern of this gene in transgenic T1 lines of F4. Table 6 provides qRT-PCR results.

Table 6. The relative quantification of the transgenic T1 lines of F4/the transgenic receptor, the tall wild-type, Y98148 (NrelF4/NrelWT) at different growth stages.

| Item | Seedling Stage | Tillering Stage | Elongation Stage | Milk Ripe Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔCt, Sdt97, carried in the transgenic T1 lines of F4 | 2.05 | 1.03 | 2.65 | 5.98 |

| ΔCt, sdt97, carried in the tall wild-type Y98148 | 2.15 | 1.69 | 2.43 | 6.28 |

| ΔΔCt = (ΔCt Sdt97-ΔCtsdt97) | −0.1 | -0.0.66 | 0.22 | −0.3 |

| NrelF4/NrelWT = 2-ΔΔCt | 1.07 | 1.58 | 0.86 | 1.23 |

At the seedling stage, the expression level of the gene Sdt97 in transgenic T1 lines of F4 was just the same as that in the transgenic receptor, the tall wild type, Y98148. At the tillering stage, the expression level of the gene Sdt97 in the transgenic T1 lines of F4 increased, ΔΔCt = –0.66, the NrelF4/NrelWT = 2–ΔΔCt = 1.58, i.e., 1.58 times higher than that in the transgenic receptor, Y98148. At the elongation stage, in contrast, the expression level of the gene Sdt97 in transgenic T1 lines of F4 decreased, ΔΔCt = 0.22, the NrelF4/NrelWT = 2–ΔΔCt = 0.86, i.e., lower than that in the transgenic receptor, Y98148. At the milk ripe stage, the expression level of the gene Sdt97 in transgenic T1 lines of F4 was just the same as, or just slightly higher than that in the tall wild type Y98148.

The results showed that gene transfer of Sdt97 induced obvious changes in the expression of this gene in transgenic T1 lines of F4, with a pattern similar to that in the semidwarfism mutant Y98149.

These results indicated that the G–C transversion that occurred in the 5′-UTR of Sdt97 induced obvious changes in the expression pattern of the Sdt97 gene carried in Y98149 and the transgenic lines, it altered the expression pattern of the gene Sdt97 itself, and led to an obvious change in plant height performance of Y98149 and the transgenic lines.

A transgenic Sdt97 line driven by a no-promoter version of the gateway vector (pGWB3) to tall wild type displays the semidwarf mutant phenotype

To highlight the effect of the point mutation in the 5′-UTR on the gene expression of Sdt97 itself, a no-promoter Gateway vector, pGWB3 [(no promoter, C-GUS)(-R1-CmR-ccdB-R2-GUS-)] (Invitrogen), was used to carry out the complementarity test of Sdt97 in this study.

The genotypes of the transgenic plants were determined by sequencing PCR products. The transgenic acceptor lines with overlapping peaks of C and G at the nucleotide location of 124 bp in the DNA sequencing chromatogram can be easily and clearly detected (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Determination of the transgenic plant genotype.

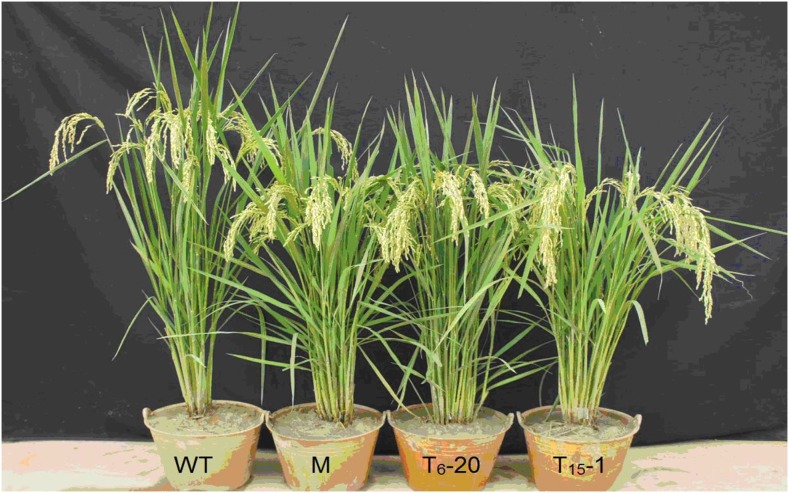

Forty-one independent transgenic T0 lines for T6, and 25 independent transgenic T0 lines for T15 were obtained. Most of the independent T0, T1 transgenic lines exhibited a semidwarf phenotype like that of the mutant (Y98149). Genetically, the positive transgenic T0, T1 plants were the same as that of the (Y98148/Y98149)F1,F2 progeny derived from crosses between Y98148 and Y98149. Because only pGWB3, which has no 35S promoter, was used in the transgenic clone construction of Sdt97, the CDS sequence of Sdt97 in Y98149 was coincident with that of sdt97 in Y98148. Therefore, the point mutation in the 5′-UTR region of Sdt97 was responsible for restoration of the semidwarfism mutant phenotype in the transgenic lines (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Height of the tall wild type (WT), the semidwarf mutant (M), and transgenic T0 for T6-20 and T15-1. From left to right: tall wild-type (WT, 100 cm), semidwarf mutant (M, 82 cm), transgenic T0 line for T6-20 (T6-20, 83 cm), and transgenic T0 line for T15-1 (T15-1, 85cm).

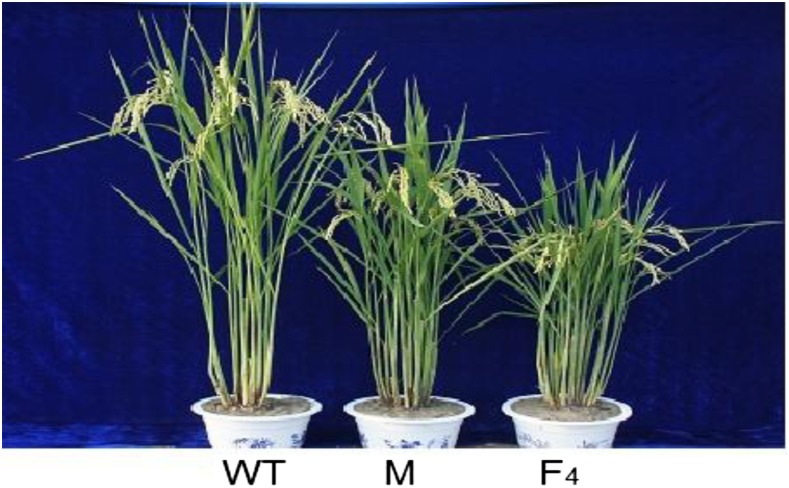

A Sdt97 transgenic line driven by the 35S promoter (tall wild type) displays a more pronounced dwarf phenotype than the mutant

In a complementarity test of Sdt97, we constructed transgenic plants. The mutant gene Sdt97 driven by the 35S promoter (F4) was introduced into tall wild-type plants (Y98148) via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. To confirm further that the mutated trait of semidwarfism was caused by a point mutation in the 5′-UTR of Sdt97, 14 independent transgenic T1 lines of the F4 generation were obtained. Most of the independent T1 transgenic lines exhibited a more pronounced dwarf phenotype than the semidwarf mutant (Y98149) (Figure 11). The results indicated that Sdt97 overexpression in the genetic background of the tall wild type (Y98148) caused a more pronounced dwarf phenotype than the semidwarf mutant (Y98149).

Figure 11.

Height of the tall wild type (WT), semidwarf mutant (M), and transgenic T1 for F4. From left to right: tall wild type (WT, 103 cm), the semidwarf mutant (M, 85 cm), and the transgenic T1 line for F4 (F4, 68 cm).

Discussion

Sdt97, a new dwarf gene reported in rice

More than 70 dwarf and semidwarf genes have been identified in rice. These genes mediate important physiological and biochemical processes, and most of them are relevant to plant hormones. The semidwarf1 (sd1), designated as the ‘Green Revolution Gene’, affects the gibberellin (GA) biosynthesis pathway (Monna et al. 2002; Sasaki et al. 2002; Spielmeyer et al. 2002; Muangprom and Osborn 2004). The d35Tan-Ginbozu is caused by a defective early step in GA biosynthesis (Itoh et al. 2004). OsGA3oxl and OsGA3ox2 encode proteins with 3b-hydroxylase activity (Itoh et al. 2001). The dwarf mutant genes GID1, GID2, dwarf mutant d1, and slr1-1 in rice are defective in response to GA (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al. 2005; Hartweck et al.and Olszewski 2006; Gomi et al. 2004; Ueguchi-Tanaka et al. 2000; Ashikari et al. 1999; Ikeda et al. 2001). Brassinosteroids (BRs) are structurally defined as C27, C28, and C29 steroids with substitutions on the A- and B-rings and side chains (Fujioka and Sakurai 1997; Yokota 1997; Grove et al. 1979).The brassinosteroid dependent 1 (brd1) is defective in BR-6-oxidase (Mori et al. 2002; Hong et al. 2002). D2 encodes a novel cytochrome P450 classified as CYP90D, The D2/CYP90D2 is an enzyme catalyzing a step in the late BR biosynthesis pathway (Hong et al. 2003). The brd2 gene is defective in the rice homolog of Arabidopsis DIMINUTO/DWARF1 (Hong et al. 2003). D11 encodes a novel cytochrome P450 (CYP724B1), D11/CYP724B1 is involved in the BR biosynthesis network in rice (Tanabe et al. 2005). Osdwarf4-1 has a weak dwarf phenotype of OsDWARF4 (Sakamoto et al. 2006). Bai et al. (2007) identified OsBZR1-interacting proteins. OsBRI1, d61-7, DLT, and three MADS box proteins are defective in response to BRs in rice (Yamamuro et al. 2000; Morinaka et al. 2006; Tong et al. 2009; Duan et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2008). The strigolactones are rhizosphere-signaling molecules as well as a new class of plant hormones with an increasing number of biological functions (Ruyter-Spira et al. 2013). The gsor23 encodes a key enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of strigolactones (SIs) (Wang et al. 2013). D53 encodes a substrate of the SCFD3 ubiquitination complex and functions as a repressor of SL signaling (Jiang et al. 2013; Zhou et al. 2013). In 2012, a gain-of-function epi-allele (Epi-df) of rice fertilization-independent endosperm1 (FIE1) was identified by Zhang et al. (2012). Epi-df is the only dwarf mutant gene entirely unrelated to plant hormones reported in rice. It has no altered nucleotide sequence but is hypomethylated in the 59 region of FIE1, resulting in a dwarf stature (Zhang et al. 2012).

Sdt97 was deduced to have resulted from a spontaneous mutation. In our previous research, Sdt97 was mapped to the long arm of chromosome 6 at the interval between two STS markers, N6 and TX5, at a genetic distance of 0.2 cM and 0.8 cM, respectively. In a recent study, Sdt97 was fine-mapped to a interval of nearly 60 kb within the PAC clone P0453H04, and LOC_Os06g44050 was identified as the candidate gene of Sdt97. Sdt97 is not allelic to the sd-1 gene on chromosome 1 (Monna et al. 2002; Sasaki et al. 2002; Spielmeyer et al. 2002), sd-t, sd-t2 on chromosome 4 (Li et al. 2001; Jiang et al. 2002 ; Zhao et al. 2005), sd-g, sd-n on chromosome 5 (Liang et al. 1994, 2004; Li et al. 2003), D53 on chromosome 11 (Wei et al. 2006), or the dwarf gene Dx on chromosome 8 (Qin et al. 2008). Clearly, Sdt97 is a novel semidwarf gene reported in rice (Tong et al. 2007).

The predicted bioinformatics results show that LOC_Os06g44050 (the candidate gene of Sdt97) encodes a putative methyladenine glycosylase, a DNA repair enzyme (http://www.Gramene.org/; http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/index.shtml). It is located on the reverse DNA strand of chromosome 6 (Chromosome 6: 26,568, 419-26,571,461) (http://www.Gramene.org/; http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/index.shtml). Compared with LOC_Os06g44050 carried by Nipponbare, the genomic DNA sequence of Sdt97 carried by the semidwarf mutant (Y98149), and sdt97 carried by tall wild type (Y98148), carry a 342-bp nucleotide deletion (Figure 8). The deletion occurred between 546 bp and 887 bp in the first exon, or between 194 bp and 535 bp in the CDS of LOC_Os06g44050 carried by Nipponbare. The peptide encoded by Sdt97 and sdt97 is 114 amino acids shorter than the peptide encoded by LOC_ Os06g44050.

Until now, no phenotype, disease, or trait is known to be associated directly with LOC_Os06g44050 (the candidate gene of Sdt97), and no phenotype, disease, or trait is associated with these gene variants in plants (www.gramene.org). Methyladenine glycosylase has been reported only in Mycobacterium bovis BCG (Liu et al. 2014). Therefore, further research into Sdt97 will open new fields of research into rice semidwarfism, with emphasis on the regulation of Sdt97 expression at the transcriptional level, and the relationship between point mutations in the 5′-UTR and Sdt97 promoter, the relationship between methyladenine glycosylase and the semidwarf phenotype of the mutant, and the physiological and biochemical pathways of Sdt97 at the molecular level.

Sdt97 could be used as an elite cultivar to breed super-high-yielding hybrid rice in China

Dwarf resources are the foundation to realizing the ideal plant type in rice breeding (Zhu 1980). Since the 1960s, the discovery and identification of new dwarf gene resources in rice have gained huge attention. However, these genes are associated with traits such as severe dwarfism, floret sterility, or abnormal plant and grain development; therefore, most of them have not been used in crop improvement (Aquino and Jennings 1966; Kinoshita 1995;Tong et al. 2003). In recent years, new semidwarf genes nonallelic to sd-1 have been identified (Liang et al. 1994, 2004; Li et al. 2001, 2003; Jiang et al. 2002; Zhao et al. 2005), but sd-1 is still the primary semidwarf gene used in rice breeding (Kinoshita 1995). It is reported that about one-half of the stock from the IRRI collection is allelic to Dgwg (Gu & Zhu 1979). In southern China, 75% of the semidwarf gene found in varieties of economic importance is at the same locus as sd-1 (Min et al. 1996).

Frequent usage of the sd-1 gene may reduce genetic diversity and bring about genetic vulnerability to pests and diseases. According to reports, in Asia, the genetic distance of intersubspecies was nearly equal to that of intervariety in rice (Hong 1999), while the genetic distance of the improvement rice varieties, and their parents, was less than half of that of intersubspecies (Zhuang et al. 1997). It is therefore imperative to develop a new source in order to broaden the genetic basis of semidwarfism. The discovery and utilization of a dominant semidwarf gene may be of great significance, not only in genetic theory but also in rice breeding practice (Tong et al. 2001, 2003).

The semidwarf mutant genes reported here are just the ideal gene resources of the dominant semidwarf, and could provide a power genetic tool not only to resolve the problem of excessive height in the inter-subspecific F1 hybrid, but also to breed an ideal type of ‘super-high-yielding rice’. In our previous research, the semidwarf mutant gene Sdt97 and the photoperiod-sensitive genic male sterile gene pms3 were combined, and a series of semidwarf PSGMS rice was bred successfully, which is now available for a two-line hybrid rice breeding program (Tong et al. 2007).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (31071396; 31371698), the Key Projects of Nature Science Foundation of Tianjin Municipality (11JCZDJC17400), and the President Nature Science Foundation of the Tianjin Academy of Agricultural Science (09012).

Footnotes

Communicating editor: J. Ma

Literature Cited

- Aquino R. C., Jennings P. R., 1966. Inheritance and significance of dwarfism in an indica rice variety. Crop Sci. 6: 551–554. [Google Scholar]

- Ashikari M., Wu J., Yano M., Sasaki T., Yoshimura A., 1999. Rice gibberellin-insensitive dwarf mutant gene Dwarf 1 encodes the subunit of GTP-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 10284–10289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai M. Y., Zhang L. Y., Gampala S. S., Zhu S. W., Song W. Y., et al. , 2007. Functions of OsBZR1 and 14–3-3 proteins in brassinosteroid signaling in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104(34): 13839–13844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Wang L., Que Z., Pan R., Pan Q., 2005. Genetic and physical mapping of Pi37(t), a new gene conferring resistance to rice blast in the famous cultivar St. No. 1. Theor. Appl. Genet. 111: 1563–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan K., Li L., Hu P., Xu S. P., Xu Z. H., et al. , 2006. A brassinolide-suppressed rice MADS-box transcription factor, OsMDP1, has a negative regulatory role in BR signaling. Plant J. 47: 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka S., Sakurai A., 1997. Brassinosteroids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 14: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomi K., Sasaki A., Itoh H., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Ashikari M., et al. , 2004. GID2, an F-box subunit of the SCF E3 complex, specifically interacts with phosphorylated SLR1 protein and regulates the gibberellin-dependent degradation of SLR1 in rice. Plant J. 37: 626–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove M. D., Spencer G. F., Rohwedder W. K., Mandava N. B., Worley J. F., Warthen J. D., Jr., et al. , 1979. Brassinolide, a plant growth-promoting steroid isolated from Brassica napus pollen. Nature 281: 216–217. [Google Scholar]

- Gu M. H., Zhu L. H., 1979. Primary analysis of the allelic relationship of several semidwarfing genes in indica varieties. Hereditas 1: 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hargrove T. R., Cabanilla V. L., 1979. The impact of semi-dwarf varieties on asian rice-breeding programs. Bioscience 29: 731–735. [Google Scholar]

- Hartweck L. M., Olszewski N. E., 2006. Rice gibberellin insensitive dwarf1 is a gibberellin receptor that illuminates and raises questions about GA signaling. Plant Cell 18: 278–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P., 2003. The genes of the Green Revolution. Trends Genet. 19: 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiei Y., Ohta S., Komari T., Kumashiro T., 1994. Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J. 6: 271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong G.F., 1999. Genomics pp. 23–26 in Rice Genome Project Shanghai Science and Technology Publishing House, Shanghai. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Shimizu-Sato S., Inukai Y., Fujioka S., et al. , 2002. Loss-of-function of a rice brassinosteroid biosynthetic enzyme, C-6 oxidase, prevents the organized arrangement and polar elongation of cells in the leaves and stem. Plant J. 32(4): 495–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Umemura K., Uozu S., Fujioka S., et al. , 2003. A rice brassinosteroid-deficient mutant, ebisu dwarf (d2), is caused by a loss of function of a new member of cytochrome P450. Plant Cell 15(12): 2900–2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda A., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Sonoda Y., Kitano H., Koshioka M., et al. , 2001. slender rice, a constitutive gibberellin response mutant, is caused by a null mutation of the SLR1 gene, an ortholog of the height-regulating gene GAI/RGA/RHT/D8. Plant Cell 13: 999–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Yutaka S., 2001. Cloning and functional analysis of two gibberellin 3b-hydroxylase genes that are differently expressed during the growth of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 8909–8914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H., Tatsumi T., Sakamoto T., Otomo K., Toyomasu T., et al. , 2004. A rice semi-dwarf gene, Tan-Ginbozu (D35), encodes the gibberellin in biosynthesis enzyme, ent-kaurene oxidase. Plant Mol. Biol. 54: 533–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G., Liang G., Zhai W., Gu M., Lu R., et al. , 2002. Genetic mapping of a new semi-dwarf gene, sd-t(t), in indica rice and estimating of the physical distance of the mapping region. Science in China 32: 193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Liu X., Xiong G. S., Liu H. H., Chen F., et al. , 2013. DWARF 53 acts as a repressor of strigolactone signalling in rice. Nature 504: 401–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khush G. S., 2001. Green revolution: the way forward. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2: 815–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, F., and Y. Futsuhara, 1997 Inheritance of morphological characters. 2. Inheritance of semidwarf, pp. 309–317 in Science of the Rice Plant, Vol. 3, edited by T. Matsuo, Y. Futsuhara, F. Kikuchi, and H. Yamaguchi. Tokyo Food and Agricultural Policy Research Center, Tokyo. [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T., 1995. Report of the Committee on Gene Symbolization, Nomenclature and Linkage Groups. Rice Genet. Newsl. 12: 997. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Choi S. C., An G., 2008. Rice SVP-group MADS-box proteins, OsMADS22 and OsMADS55, are negative regulators of brassinosteroid responses. Plant J. 54: 93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Gu M., Liang G., Xu J., Chen Z., et al. , 2001. Chromosome location of a semi-dwarf gene sd-t in indica rice (O. sativa L.). Acta Genetica Sinica. 28: 33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Xu J., Wang X., Yan C., Liang G., et al. , 2003. Chromosome location of a semi-dwarf gene sd-n in indica rice (O. sativa L.). J. Yangzhou Univ. 23: 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liang C. Z., Gu M. H., Pan X. B., Liang G. H., Zhu L. H., 1994. RFLP tagging of a new semidwarfing gene in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 88: 898–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G. H., Cao X. Y., Sui J. M., Zhao X. Q., Yan C. J., et al. , 2004. Fine mapping of a semidwarf gene sd-g in indica rice (Oryza sativa L.). Chin. Sci. Bull. 49: 900–904. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Huang Ch., He Zh. G., 2014. A TetR family transcriptional factor directly regulates the expression of a 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase and physically interacts with the enzyme to stimulate its base excision activity in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J. Biol. Chem. 289: 9065–9075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelmore R. W., Paran I., Kesseli R. V., 1991. Identification of markers linked to disease-resistance genes by bulked segregant analysis: a rapid method to detect markers in specific genomic regions by using segregating populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88: 9828–9832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min Sh. K., Shen Z. T., Xiong Zh. M., 1996, Rice High Yield Breeding, pp. 305–311 in RiceBreeding, Chinese Agriculture Press, Beijing. [Google Scholar]

- Monna L., Kitazawa N., Yoshino R., Susuki J., Masuda H., et al. , 2002. Positional cloning of rice semidwarfing gene, sd-1: rice ‘green revolution gene’ encodes a mutant enzyme involved in gibberellin synthesis. DNA Res. 9: 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M., Nomura T., Ooka H., Ishizaka M., Yokota T., et al. , 2002. Isolation and characterization of a rice dwarf mutant with a defect in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 130: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morinaka Y., Sakamoto T., Inukai Y., Agetsuma M., Kitano H., et al. , 2006. Morphological alteration caused by brassinosteroid insensitivity increases the biomass and grain production of rice. Plant Physiol. 141(3): 924–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muangprom A., Osborn T. C., 2004. Characterization of a dwarf gene in Brassica rapa, including the identification of a candidate gene. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108: 1378–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norambuena P. A., Copeland J. A., Křenková P., Štambergová A., Macek M., Jr., 2009. Diagnostic method validation: high resolution melting (HRM) of small amplicons genotyping for the most common variants in the MTHFR gene. Clin. Biochem. 42: 1308–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Q. H., Hu Z. D., Tanisaka T., Wang L., 2003. Fine mapping of the blast resistance gene Pi15, linked to Pii, on rice chromosome 9. Acta Bot. Sin. 45: 871–877. [Google Scholar]

- Qin R., Qiu Y., Cheng Z., Shan X., Guo X., et al. , 2008. Genetic analysis of a novel dominant rice dwarf mutant 986083D. Euphytica 160: 379–387. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers O. S., Bendich A. J., 1998. Extraction of total DNA from plant tissue. Plant Mol. Biol. Manual A 6: 1010. [Google Scholar]

- Ruyter-Spira C., Al-Babili S., van der Krol S., Bouwmeeste H., 2013. The biology of strigolactones. Trends Plant Sci. 18(2): 72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto T., Morinaka Y., Ohnishi T., Sunohara H., Fujioka S., et al. , 2006. Erect leaves caused by brassinosteroid deficiency increase biomass production and grain yield in rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 24: 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A., Ashikari M., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Itoh H., Nishimura A., et al. , 2002. A mutant gibberellin-synthesis gene in rice. Nature 416: 701–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielmeyer W., Ellis M. H., Chandler P. M., 2002. Semidwarf (sd-1) ‘Green Revolution’ rice, contains a defective gibberellin 20-oxidase gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 9043–9048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M., Takeda K., 1969. Type and grouping of internode pattern in rice culm—genetical studies on rice plant, XXXVII. Memoirs Fac. Agric. Hokkaido Univ. 7: 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe S., Ashikari M., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Yoshida S., et al. , 2005. A novel cytochrome P450 is implicated in brassinosteroid biosynthesis via the characterization of a rice dwarf mutant, dwarf11, with reduced seed length. Plant Cell 17: 776–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong H. N., Jin Y., Liu W. B., Li F., Fang J., et al. , 2009. DWARF AND LOW-TILLERING, a new member of the GRAS family, plays positive roles in brassinosteroid signaling in rice. Plant J. 58(5): 803–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong J. P., Wu Y. J., Wu J. D., Zheng L., Yu Z. L., 2001. Discovery of a dominant semi-dwarf japonica rice mutant and its preliminary study. Chinese J. Rice Sci. 15: 314–316. [Google Scholar]

- Tong J. P., Wu Y. J., Wu J. D., Zheng L. Y., Zhang Z. G., et al. , 2003. Study on the inheritance of a dominant semi-dwarf japonica rice mutant Y98149. Acta Agron. Sin. 29: 473–477. [Google Scholar]

- Tong J. P., Liu X. J., Zhang S. Y., Li S. Q., Peng X. J., et al. , 2007. Identification, genetic characterization, GA response and molecular mapping of Sdt97: a dominant mutant gene conferring semi-dwarfism in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genet. Res. 89: 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuinstra M. R., Ejeta G., Goldsbrough P. B., 1997. Heterogeneous inbred family (HIF) analysis: a method for developing near isogenic lines that differ at quantitative trait loci. Theor. Appl. Genet. 95: 1005–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Fujisawa Y., Kobayashi M., Ashikari M., Iwasaki Y., et al. , 2000. Rice dwarf mutant d1, which is defective in the a subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein, affects gibberellin signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 11638–11643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Ashikari M., Nakajima M., Itoh H., Katoh E., et al. , 2005. Gibberellin insensitive Dwarf1 encodes a soluble receptor for gibberellin. Nature 437: 693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Yuan Sh. J., Yin I., Zhao J. F., Wan J. M., et al. , 2013. Positiona1 cloning and expression analysis of the gene responsible for the high tillering dwarf phenotype in the indica rice mutant gsor23. Chin J Rice Sci. 27(1): 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wei L. R., Xu J. C., Li X. B., Qian Q., Zhu L. H., 2006. Genetic analysis and mapping of the dominant dwarfing gene D-53 in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 48: 447. [Google Scholar]

- Xue W., Xing Y., Weng X., Zhao Y., Tang W., et al. , 2008. Natural variation in Ghd7 is an important regulator of heading date and yield potential in rice. Nat. Genet. 40: 761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamuro C., Ihara Y., Wu X., Noguchi T., Fujioka S., et al. , 2000. Loss of function of a rice brassinosteroid insensitive1 homolog prevents internode elongation and bending of the lamina joint. Plant Cell 12(9): 1591–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka N., Watanabe S., Hayashi K. T. M., Fuchigami H., Harada R. T. K., 2005. Fine mapping of the FT1 locus for soybean flowering time using a residual heterozygous line derived from a recombinant inbred line. Theor. Appl. Genet. 110: 634–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota T., 1997. The structure, biosynthesis and function of brassinosteroids. Trends Plant Sci. 2: 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L. P., 1999 Super hybrid rice, pp. 1–5 in Prospects of Rice Genetics and Breeding for the 21st Century-Paper Collection of International Rice Genetics and Breeding Symposium. China Agricultural Scientech Press, Beijing. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Cheng Z., Qin R., Qiu Y., Wang J. L., et al. , 2012. Identification and characterization of an epi-allele of FIE1 reveals a regulatory linkage between two epigenetic marks in rice. Plant Cell 24(11): 4407–4421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Shen B. Z., Dai X. K., Mei M. H., Saghai Maroof M. A., et al. , 1994. Using bulked extremes and recessive classes to map genes for photoperiodsensitive genic male sterility in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 8675–8679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. Q., Liang G. H., Zhou J. S., Yan C. J., Cao X. Y., et al. , 2005. Molecular mapping of two semi-dwarf genes in an indica rice variety Aitai yin3 (Oryza sativa L.). Acta Genetica Sinica. 32: 189–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F., Lin Q., Zhu L., Ren Y., Zhou K., et al. , 2013. D14- SCFD3-dependent degradation of D53 regulates strigolactone signalling. Nature 504(7480): 406–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L. H., Gu M. H., Xue Y. L., 1980. Studies on the dwarfism of indica rice. J. Nanjing Agric. College 2: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M. L., Wang L., Pan Q. H., 2004. Identification and characterization of a new blast resistance gene located on rice chromosome 1 through linkage and differential analysis. Phytopathology 4: 515–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang J. Y., Qian H. R., Lu J., Lin H. X., Zheng K. L., 1997. RFLP variation among commercial rice germplasms in China. J. Gentet. Breed. 51: 263–268. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article.