Abstract

Introduction

In the current study, the protective effect of hesperidin (HP) on carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced hepatotoxicity in rats was investigated.

Material and methods

Twenty-eight rats were divided equally into four groups. The first group was kept as a control and given only vehicle. In the second, rats were orally administered 50 mg/kg/day HP for 10 days. Carbon tetrachloride was given in a single intraperitoneal injection at the dose of 2 ml/kg in the third group. In the fourth group, the rats were treated with equal doses of CCl4 and HP.

Results

It was found that CCl4 induced oxidative stress via a significant increase in the formation of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) and caused a significant decline in the levels of glutathione (GSH), catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in rats. In contrast, HP blocked these toxic effects induced by CCl4, causing an increase in GSH, CAT and SOD levels and decreased formation of TBARS (p < 0.01). In addition, histopathological damage increased with CCl4 treatment. In contrast, HP treatment eliminated the effects of CCl4 and stimulated anti-apoptotic events, as characterized by reduced caspase-3 activation.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrated that CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity can be prevented with HP treatment. Thus, co-administration of HP with CCl4 may be useful for attenuating the negative effects of CCl4 on the liver.

Keywords: liver, hesperidin, carbon tetrachloride, hepatotoxicity

Introduction

Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) is a potent hepatotoxic chemical that produces free radicals and is widely used to induce acute hepatic injury in experimental animal models [1]. Carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic necrosis is caused by bioactivation of the microsomal cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase system, resulting in the formation of a trichloromethyl radical (CCl3) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [2]. Reactive oxygen species consist of free radicals or oxygen free-radical-generating agents, such as a superoxide anion (O2 –), an hydroxyl radical (OH–) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [3]. Metabolic processes are usually associated with the generation of free radicals, particularly oxygen-derived radicals that oxidize and damage surrounding biomolecules [4]. The consequences of CCl4-induced lipid peroxidation include membrane disintegration, loss of membrane-associated enzymes [5, 6] and necrosis.

Hesperidin (HP) is a bioflavonoid that plays a role in plant defense and is abundant in citrus species, such as grapefruit, lemon and orange. Hesperidin is used effectively as a supplemental agent in complementary therapy protocols, since it possesses biological and pharmacological properties as an effective antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic, and anti-hypertensive agent with lipid-lowering activity [7–9]. The antioxidant properties of HP protect testicular function from cadmium toxicity, and HP regulates hepatic cholesterol synthesis by inhibiting the activity of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase [10–12].

Hepatotoxicants, including CCl4, lead to oxidative stress and histological damage in the liver. Therefore, antioxidant agents such as HP may prevent CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity. In this study, we examined the biochemical and histological effects of HP on CCl4-induced toxicity.

Material and methods

Chemicals

Hesperidin was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Carbon tetrachloride was given by İnonu University chemistry laboratory as a gift. All other chemicals for biochemical and histological analysis were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO).

Animals and treatment

A total of 28 healthy adult male Wistar albino rats (2–3 months of age, 250–300 g) were obtained from the Experimental Animal Research Institute (Malatya, Turkey). Animals were housed in sterilized polypropylene rat cages, under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle, at an ambient temperature of 21°C. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Experiments were performed in accordance with the animal ethics guidelines of the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee.

Rats were randomly divided into four equal groups: control, CCl4, HP, CCl4 + HP (n = 7 per group). Carbon tetrachloride was diluted 1: 1 with corn oil and administered in a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) dose of 2 ml/kg. Hesperidin was dissolved in 1% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and administered orally at a dose of 50 mg/kg for 10 consecutive days. In the control group, rats were treated with the corn oil and 1% CMC vehicle. In the CCl4 group, CCl4 was administered in a single injection on day 2. Rats in the HP group were treated with HP for 10 days, and those in the CCl4 + HP group were treated with CCl4 and HP together. Tissue samples were collected on day 10 after the first HP treatment. The animals were euthanized under ether anesthesia, and tissue samples were removed immediately, dissected on ice-cold glass, and stored at –86°C until analysis.

Histological examination

For light microscopic evaluation, liver samples were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. The specimens were cut into 5-µm thick sections, mounted on slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H + E). Tissue samples were examined using a Leica DFC280 light microscope and the Leica Q Win Image Analysis system (Leica Micros Imaging Solutions Ltd., Cambridge, UK).

For immunohistochemical analysis, thick sections were mounted on polylysine-coated slides. After rehydrating, samples were transferred to citrate buffer (pH 7.6) and heated in a microwave oven for 20 min. After cooling for 20 min at room temperature, the sections were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then sections were kept in 0.3% H2O2 for 7 min and afterward washed with PBS. Sections were incubated with primary rabbit-polyclonal caspase-3 antibody (Abcam, Ab4051) for 2 h. They then were rinsed in PBS and incubated with biotinylated goat antipolyvalent for 10 min and streptavidin peroxidase for 10 min at room temperature. Staining was completed with chromogen + substrate for 15 min, and slides were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin for 1 min, rinsed in tap water, and dehydrated. The caspase-3 kit was used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Biochemical assay

The levels of homogenized tissue TBARS, as an index of lipid peroxidation, were determined by thiobarbituric acid reaction using the method of Yagi [13]. The product was evaluated spectrophotometrically at 532 nm and results are expressed as nmol/g tissue. The glutathione (GSH) content of the liver homogenate was measured at 412 nm using the method of Sedlak and Lindsay [14]. The GSH level was expressed as nmol/ml. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured by the inhibition of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction due to O2 – generated by the xanthine/xanthine oxidase system [15]. One unit of SOD activity was defined as the amount of protein causing 50% inhibition of the NBT reduction rate. The product was evaluated spectrophotometrically at 560 nm. Results are expressed as IU/mg protein. Catalase (CAT) activity of tissues was determined according to the method of Aebi [16]. The enzymatic decomposition of H2O2 was followed directly by a decrease in absorbance at 240 nm. The difference in absorbance per unit time was used as a measure of CAT activity. Tissue protein content was determined according to the method developed by Lowry et al. [17] using bovine serum albumin as standard.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as mean ± SD. Differences were considered to be significant at p < 0.01 for biochemical changes. The computer program SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. For biochemical values, statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey's honestly significant difference test. For histological evaluation, the microscopic score of each tissue was calculated as the sum of the scores given for each criterion. Scores were given as absent (0), slight (1), moderate (2), and severe (3) for each criterion. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 13 and MedCalc programs. All groups were compared by the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Exact p-values were given where available, and p < 0.0001 was accepted as statistically significant. All results are expressed as means ± standard error (SE).

Results

Histological evaluation

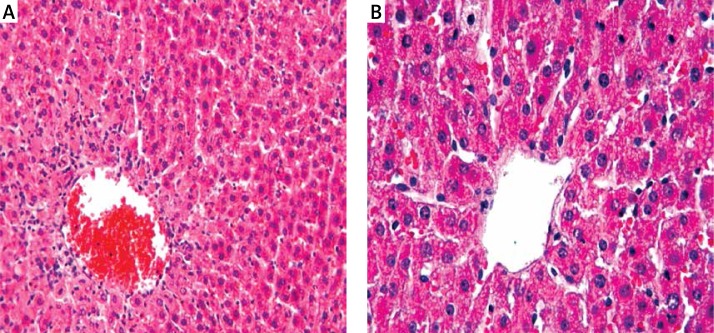

All figures demonstrate the histological changes in the livers of rats of each group. In the control (Figure 1 A) and HP (Figure 1 B) groups, we observed normal liver architecture and hepatocytes with well-preserved cytoplasms and nuclei. In the CCl4 (Figure 2) and CCl4 + HP (Figures 3 A, B) groups, we observed distortion of the hepatic cords, hepatocellular necrosis, hemorrhage (Figures 2 A, C), mononuclear cell infiltration (Figures 2 B, D), vascular congestion (Figures 2 D), eosinophilic and pyknotic nuclei hepatocytes (Figures 2 C, E), as well as vacuolated hepatocytes (Figure 2 F), which were not as extensive as in the CCl4 group, indicating an improved histological appearance in the liver tissue. The microscopic damage score for each group was determined in the histological section, and the results are given in Table I.

Figure 1.

In the liver, a normal histological appearance was observed following hematoxylin and eosin staining of the (A) control and (B) hesperidin (HP) groups

VC – vena centralis; 20×.

Figure 2.

In the CCl4 group, we observed (A) distortion of the hepatocyte radial arrangement, hemorrhage and necrosis, (B) cell infiltration, (C) necrosis and hemorrhage, (D) vascular congestion and infiltration, (E) eosinophilic and pyknotic nuclei, and (F) vacuolization and congestion (A, B: H + E; 10×, C, D, E: H + E; 20×, F: H + E; 40×)

Figure 3.

Histological findings were decreased in the CCl4 + hesperidin (HP) group (A: H + E; 20×, B: H + E; 40×)

Table I.

Comparison of the effect of HP on microscopic damage caused by CCl4 in liver

| Groups | Microscopic damage (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| 1 Control | 0.39 ±0.49a |

| 2 CCl4 | 2.13 ±0.74b |

| 3 HP | 0.70 ±1.29a |

| 4 CCl4 + HP | 1.64 ±0.70c |

The differences between the mean values bearing different superscript letters within the same column are statistically significant (p ≤ 0.0001). SE – standard deviation.

Caspase-3-stained cells were not observed in the control (Figure 4 A) or HP (Figure 4 B) groups but were abundant in the CCl4 group (Figure 4 C). The density of caspase-3-positive cells was decreased in the CCl4 + HP group (Figure 4 D).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical expression of caspase-3 in the (A) control, (B) hesperidin (HP), (C) CCl4 and (D) CCl4 + HP groups. The number of positively stained cells decreased in the CCl4 + HP group. Positively stained caspase-3 cells are indicated by the arrows; 20×

Biochemical evaluation

Carbon tetrachloride administration led to a significant increase in thiobarbituric acid-reactive substance (TBARS) levels compared with the other groups. Moreover, HP treatment caused a significant decrease in elevated TBARS levels when administered together with CCl4, compared with the CCl4 group (Table II). Glutathione, CAT and SOD levels were decreased significantly by CCl4 treatment compared with the other experimental groups, and these parameters were elevated significantly by HP treatment when compared with the CCl4 group (Table II). There were no significant differences between the control and HP groups, except for the CAT values, which were decreased significantly by HP treatment compared with the other groups.

Table II.

Levels of SOD, CAT, GSH and TBARS in liver tissue (mean ± SD)

| Group | TBARS [nmol/g tissue] | Reduced GSH [nmol/ml] | CAT [kU/mg protein] | SOD [U/mg protein] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 7.54 ±0.39a | 181.6 ±22.9a | 0.93 ±0.11a | 15.2 ±2.25a |

| CCl4 | 11.9 ±0.87b | 112.3 ±14.1b | 0.42 ±0.09b | 9.41 ±1.04b |

| HP | 8.08 ±1.40a | 197.1 ±36.5c | 0.93 ±0.09a | 16.7 ±1.90ac |

| CCl4 + HP | 10.1 ±0.93c | 158.5 ±17.5a | 0.75 ±0.07c | 14.2 ±2.27a |

Means bearing different superscripts within same column are significantly different (p < 0.01).

Discussion

Carbon tetrachloride is a well-established hepatotoxic agent that causes severe liver damage and produces liver fibrosis and biochemical patterns that resemble human liver cirrhosis. The present study was designed to establish the protective effects of HP, a citrus bioflavonoid, on CCl4-induced liver damage. The results demonstrated that HP ameliorated biochemical and histological evidence of CCl4-induced liver damage.

Oxidative stress is caused by an imbalance between free radicals, such as TBARS, and the activity of the antioxidant defense system, including SOD, CAT, and GSH levels, which leads to lipid peroxidation and enzymatic inactivation [18]. TBARS are the final metabolites of peroxidized polyunsaturated fatty acids and are considered a late biomarker of oxidative stress [19]. Carbon tetrachloride treatment in rats markedly changed antioxidant enzyme activities, which was prevented by the co-administration of rutin, supporting a role for oxidative stress in CCl4-induced liver damage [20].

The liver contains many drug metabolizing enzymes that metabolize toxic chemicals in the liver. Carbon tetrachloride is metabolized by a cytochrome P450 enzyme to produce highly toxic CCl3 and CCl3O2 free radicals that damage hepatocytes [21–24]. Both CCl3 and CCl3O2 bind to proteins or lipids and extract a hydrogen atom from an unsaturated lipid, initiating lipid peroxidation and liver damage. Therefore, increased TBARS in CCl4-treated rats may result from enhanced membrane lipid peroxidation by free radicals and the failure of antioxidant defense mechanisms that prevent formation of excessive free radicals [25, 26]. Similarly, we found that CCl4 significantly induced oxidative damage, increased TBARS levels, and decreased GSH levels and the activities of antioxidant enzymes, including SOD and CAT, in the liver. Another study showed that the balance between ROS production and antioxidant defenses mediates oxidative stress during CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity. In addition, decreased SOD and CAT activities in the livers of CCl4-treated rats may be due to free radicals generated by CCl4 or inactivation of the antioxidant enzymes [27]. Another study demonstrated that administration of CCl4 to rats caused oxidative stress in the liver and was associated with significantly lower antioxidant activities of GSH, CAT and SOD. Therefore, the available literature confirms our results [28–30].

Our study further demonstrated that HP treatment reversed the oxidative effects of CCl4 via a significant reduction in elevated TBARS levels and induction of the antioxidant defense system. Only one other study has described the effects of HP against CCl4 toxicity, but that study did not address any histological changes [1]. That group concluded that HP could prevent CCl4 toxicity, which is in agreement with our results. There are a few studies describing the protective effects of HP on general liver injury [31, 32]. For example, Bentli et al. [33] determined that HP protected the liver against dioxin toxicity and claimed that it can be used to prevent liver injury. In addition to those findings, Chen et al. determined that HP reduced indicators of oxidative stress, such as ROS and lipid peroxidation, in a dose-dependent manner [34]. Heffner and Repine [35] suggested that HP offers protection by terminating lipid peroxidation side chains rather than scavenging extracellular non-lipid radicals that initiate lipid peroxidation. This supports our conclusion that HP protects liver tissue against many toxic agents, such as CCl4, and these effects may be due to HP's antioxidant and radical scavenging properties.

Upon histological evaluation, we determined that CCl4 treatment caused severe histological damage including distortion of hepatic cords, necrosis, vascular congestion, vacuolated hepatocytes, hepatocellular necrosis, eosinophilic and pyknotic nuclei, as well as mononuclear cell infiltration in liver tissues of rats. We also found a significantly larger number of caspase-3-stained cells, which were indicative of liver apoptosis, in the CCl4 group compared with the HP + CCl4 group. This demonstrates that HP protected the liver against cell death. Ebaid et al. [36] reported that an increased number of mitotic figures, vacuolated hepatocytes, eosinophilic hepatocytes and collagen deposition were observed in the histological sections of the CCl4-challenged group. In addition to those findings, Cui et al. [37] reported that in CCl4-injured mice, the cytoplasm was significantly reduced and the nuclei became atrophic, suggesting that CCl4 induced severe liver cell injury. Another study showed that CCl4 causes hepatic injury, including hepatocytic necrosis, steatosis, and inflammation [38]. These findings paralleled and confirmed our results describing histological damage. Moreover, our observations indicate that histopathological damage was ameliorated by HP treatment. A previous study by Bentli et al. (2013), which described the effect of HP treatment against liver injury, confirmed our findings, since they reported that HP treatment protects the liver against dioxin toxicities. Das Neves et al. also found that HP and lipoic acid exhibit protective effects against sodium arsenite-induced acute toxicity in the liver and kidneys of mice [39]. The histological effects of CCl4 on liver tissue were correlated with and caused by oxidative stress. Therefore, strong antioxidant agents such as HP can protect the liver by scavenging free radicals.

In conclusion, in the current study, we confirmed that a single dose of 2 ml/mg CCl4 is toxic to rats, causing increased oxidative stress and histological changes indicative of liver damage. Also, we found that the use of HP at the dose of 50 mg/kg/day for 10 consecutive days in combination with CCl4 minimized its hepatotoxicity, which was evident from decreasing TBARS levels, histological changes in tissue and increasing antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, CAT) and GSH levels. The beneficial effects of HP against CCl4-induced liver damage may be due to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and free radical scavenging properties. Therefore, it appears that HP, a citrus flavonoid, can prevent and protect against many toxicological situations including CCl4 toxicity caused oxidative stress. In this context, it is suggested that HP may be clinically used in human health as a radical scavenger agent.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tirkey N, Pilkhwal S, Chopra K. Hesperidin, a citrus bioflavonoid, decreases the oxidative stress produced by carbon tetrachloride in rat liver and kidney. BMC Pharmacol. 2005;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee KJ, Choi JH, Khanal T, Hwang YP, Chung YC, Jeong HG. Protective effect of caffeic acid phenethyl ester against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Toxicology. 2008;248:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valko M, Rhodes CJ, Moncol J, Izakovic M, Mazur M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;10:1–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yahuaca P, Amaya A, Rojkind M, Mourelle M. Cryptic adenosine triphosphatase activities in plasma membranes of CCl4-cirrhotic rats. Its modulation by changes in cholesterol/phospholipids ratios. Lab Invest. 1985;53:541–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muriel P. Nitric oxide protection of rat liver from lipid peroxidation, collagen accumulation, and liver damage induced by carbon tetrachloride. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56:773–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyake Y, Yamamoto K, Tsujihara N, Osawa T. Protective effects of lemon flavonoids on oxidative stress in diabetic rats. Lipids. 1998;33:689–95. doi: 10.1007/s11745-998-0258-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiba H, Uehara M, Wu J, et al. Hesperidin, a citrus flavonoid, inhibits bone loss and decreases serum and hepatic lipids in ovariectomized mice. J Nutr. 2003;133:1892–7. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.6.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morand C, Dubray C, Milenkovic D, et al. Hesperidin contributes to the vascular protective effects of orange juice: a randomized cross over study in healthy volunteers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:73–80. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.004945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi MS. Plasma and hepatic cholesterol and hepatic activities of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase and acyl CoA: cholesterol transferase are lower in rats fed citrus peel extract or a mixture of citrus bioflavonoids. J Nutr. 1999;129:1182–5. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.6.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SH, Jeong TS, Park YB, Kwon YK, Choi MS, Bok SH. Hypocholesterolemic effect of hesperetin mediated by inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl coenzyme A reductase and acylcoenzyme A: cholesterol acyltranseferase in rats fed high-cholesterol diet. Nutr Res. 1999;19:1245–58. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park YB, Do KM, Bok SH, Lee MK, Jeong TS, Choi MS. Interactive effect of hesperidin and vitamin E supplements on cholesterol metabolism in high cholesterol-fed rats. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2001;71:36–44. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.71.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yagi K. Simple assay for the level of total lipid peroxides in serum or plasma. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;108:101–6. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-472-0:101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sedlak J, Lindsay RH. Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman's reagent. Anal Biochem. 1968;25:192–205. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun Y, Oberley LW, Li YA. Simple method for clinical assay of superoxide dismutase. Clin Chem. 1988;34:497–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aebi H. Catalase. In: Bergmeyer HU, editor. Methods of Enzymatic Analysis. New York: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 673–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RI. Protein measurement with folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciftci O, Vardi N, Ozdemir I. Effects of quercetin and chrysin on 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Environ Toxicol. 2013;28:146–54. doi: 10.1002/tox.20707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheeseman KH. Mechanisms and effects of lipid peroxidation. Mol Aspects Med. 1993;14:191–7. doi: 10.1016/0098-2997(93)90005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang X, Wang X, Lv Y, Xu L, Lin J, Diano Y. Protection effect of kallistatin on carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in rats via antioxidative stress. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohta Y, Kongo M, Sasaki E, Nishida K, Ishiguro I. Therapeutic effect of melatonin on carbon tetrachloride-induced acute liver injury in rats. J Pineal Res. 2000;28:119–26. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2001.280208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girish C, Koner BC, Jayanthi S, Rao KR, Rajesh B, Pradhan SC. Hepatoprotective activity of six polyherbal formulation in CCl4 induced liver toxicity in mice. Indian J Exp Biol. 2009;47:257–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huo HZ, Wang B, Liang YK, Bao YY, Gu Y. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant effects of licorice extract against CCl4-induced oxidative damage in rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:6529–43. doi: 10.3390/ijms12106529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pingle BR, Apte KG, Gupta M, Chakraborthy GS. Hepatoprotective activity of different extracts of grains of Eleusinecoracana. Pharmacol Online. 2011;2:279–86. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Tan H, Sun Y, Zhou S, Cao J, Wang F. The preventive effects of heparin-superoxide dismutase on carbon tetrachloride-induced acute liver failure and hepatic fibrosis in mice. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;327:219–28. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim HY, Kim JK, Choi JH, et al. Hepatoprotective effect of pinoresinol on carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic damage in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010;112:105–12. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09234fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganie SA, Haq E, Maood A, Zargar MA. Amelioration of carbon tetrachloride induced oxidative stress in kidney and lung tissues by ethanolicrhizome extract of Podophyllum hexandrum in Wistar rats. J Med Plants Res. 2010;4:1673–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozturk F, Gul M, Ates B, et al. Protective effect of apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) on hepatic steatosis and damage induced by carbon tetrachloride in Wistar rats. Br J Nutr Dec. 2009;102:1767–75. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509991322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu B, Xu Y, Xu L, et al. Mechanism investigation of dioscin against CCl4-induced acute liver damage in mice. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2012;34:127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaaban AA, Shaker ME, Zalata KR, El-kashef HA, Ibrahim TM. Modulation of carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic oxidative stress, injury and fibrosis by olmesartan and omega-3. Chem Biol Interact. 2014;207:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timoshin AA, Dorkina EG, Paukova EO, Vanin AF. Quercetin and hesperidin decrease the formation of nitric oxide radicals in rat liver and heart under the conditions of hepatosis. Biofizika. 2005;50:1145–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeh YH, Hsieh YL, Lee YT. Effects of yam peel extract against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:7387–96. doi: 10.1021/jf401864y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bentli R, Ciftci O, Cetin A, Unlu M, Basak N, Cay M. Oral administration of hesperidin, a citrus flavonone, in rats counteracts the oxidative stress, the inflammatory cytokine production, and the hepatotoxicity induced by the ingestion of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) Eur Cytokine Netw. 2013;24:91–6. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2013.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen M, Gu H, Ye Y, et al. Protective effects of hesperidin against oxidative stress of tert-butyl hydroperoxide in human hepatocytes. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:2980–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heffner JE, Repine JE. Pulmonary strategies of antioxidant defense. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:531–54. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.2.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ebaid H, Bashandy SA, Alhazza IM, Rady A, El-Shehry S. Folic acid and melatonin ameliorate carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic injury, oxidative stres and inflammation in rats. Nutr Metabol. 2013;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui Y, Han Y, Yang X, Sun Y, Zhao Y. Protective effects of quercetin and quercetin-5’,8-disulfonate against carbon tetrachloride-caused oxidative liver injury in mice. Molecules. 2013;19:291–305. doi: 10.3390/molecules19010291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.PerezTamayo R. Is cirrhosis of the liver experimentally produced by CCl4 and adequate model of human cirrhosis? Hepatology. 1983;3:112–20. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840030118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das Neves RN, Carvalho F, Carvalho M, et al. Protective activity of hesperidin and lipoic acid against sodium arsenite acute toxicity in mice. Toxicol Pathol. 2004;32:527–35. doi: 10.1080/01926230490502566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]