Abstract

Despite seeming uniformity in the law, end-of-life controversies have highlighted variations among state brain death laws and their interpretation by courts. This article provides a survey of the current legal landscape regarding brain death in the United States, for the purpose of assisting professionals who seek to formulate or assess proposals for changes in current law and hospital policy. As we note, the public is increasingly wary of the role of organ transplantation in determinations of death, and of the variability of brain death diagnosing criteria. We urge that any attempt to alter current state statutes or to adopt a national standard must balance the need for medical accuracy with sound ethical principles which reject the utilitarian use of human beings and are consistent with the dignity of the human person. Only in this way can public trust be rebuilt.

Keywords: brain death, brain death laws, dead donor rule, organ transplantation, Uniform Determination of Death Act

I. INTRODUCTION

All 50 states have adopted by law the neurological criteria for determining death, whether by statute, regulation, or judicial decision. By adoption of the Uniform Determination of Death Act, these laws recognize total brain death, or the irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, as a valid criterion for death. The standard rationale for this criterion is that “since death is the breakdown of the organism as a whole, and the functioning of the brain is necessary for the integration of the various cells, tissues, and organs into a single organism—total brain death is the death of the human being” (Lee, 2015).

Despite this seeming uniformity in the law, end-of-life controversies have increasingly made their way into the headlines, highlighting variations among state brain death laws and their interpretation by courts. Further, the growing disproportion between the demand for organs and their supply has resulted in increasing criticism by some of the dead donor rule (DDR), the ethical norm that protects patients by mandating that vital organs be taken only from persons who are dead––whether by irreversible loss of all brain or cardiac function.

The authors recognize that the determination of death by neurological criteria (brain death) raises controversies even among likeminded allies. The authors also recognize that the clinical determination of brain death of patients whose cardiac and respiratory functions are artificially maintained require the most rigorous diagnostic standards.

It is beyond the scope of this article to analyze the complex medical, legal, and ethical issues that arise from the neurological determination of death and its relation to organ procurement policy. Rather, this article simply provides a survey of the current legal landscape regarding brain death in jurisdictions throughout the United States, for the purpose of assisting professionals in the fields of medicine, law, and moral philosophy who seek to formulate or assess various proposals for changes in current law and hospital policy. 1

Section II addresses modern brain death law, focusing on the DDR and its modern challengers, and on the origins of the Uniform Determination of Death Act.

Section III sets forth the various features of the brain death statutes and cases across the United States, including organ transplantation provisions, and miscellaneous variations, such as who may make the determination of death. This section also addresses brain death during pregnancy, focusing on how court rulings and statutes that provide for pregnancy-exclusions to advanced directives have impacted mothers declared to be brain dead and the lives of their unborn children.

Section IV addresses criticisms of the current state-based model, including public distrust of the role of organ transplantation in determinations of death, and the variability of brain death diagnosing criteria.

Finally, Section V concludes that any attempt to alter current state statutes or to adopt a national standard should proceed with the utmost attention to balancing the need for medical accuracy with sound ethical principles consistent with respect for the inviolable and inherent dignity of the human person. Clarity in law and policy based on medical ethics that reject the utilitarian use of human beings are necessary to bridge the gap between the medical community and an increasingly wary public in order to rebuild trust in regard to ethical criteria for both the determination of death and standards for organ procurement.

II. MODERN BRAIN DEATH LAW

The DDR and its Challengers

The determination of death criteria recognized in jurisdictions across the United States have raised complex medical, legal, and ethical issues, largely based on the prevailing respect for a moral framework known as the DDR. The DDR is neither a piece of legislation nor an absolute rule of medicine. Rather, “it is an ethical norm that has been formulated in at least two ways: 1. organ donors must be dead before procurement of organs begins; 2. organ procurement itself must not cause the death of the donor. Only the second formulation has a foundation in law, namely, in laws prohibiting homicide, which forbids that patients be killed for any reason” (DuBois, 2002). 2

Scholars have noted that the DDR “helps to maintain public trust in organ donation” because it “keeps medical practices away from the spectrum of the slippery slope that might be created if an exception to the prohibition of killing for social purposes were accepted” (Rodriguez-Arias, Smith, and Lazar, 2011). Yet, the DDR is under increasing criticism, especially by some who claim that the bifurcated legal standard for declaring death (circulatory death or brain death) “may be allowing organ procurement in ways that already violate the DDR.” 3

Indeed, some critics are expressly urging policymakers to engage in a discussion about “abandoning” the DDR in favor of “an ethical focus on autonomy and non-malfeasance” that “would require creation of legal exceptions to our homicide laws” (Truog, Miller, and Halpern, 2013, 1287–1289; see also Arnold and Youngner, 1993). Such proposals are based on the justification that “when death is very near, some patients may want to die in the process of helping others to live, even if that means altering the timing or manner of their death” (Truog, Miller, and Halpern, 2013, 1289, n. 4).

This proposal to justify decisions by a living patient (or his or her family/health care proxy) who may become a donor of vital organs raises dangerous and profound issues that implicate the legal arguments often surrounding practices such as euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide, and the “liberty” interests that have been used by courts to proclaim constitutional protection for elective abortion.

Numerous examples in the legal history of the United States illustrate that the so-called right of an individual (or his or her proxy) to choose an inherently immoral means to achieve a purported individual or public good often degenerates into violations of conscience and threats to the human dignity of others. This is often manifested, based on the asserted right of the government or individuals with unequal bargaining power to directly or subtly coerce another individual into “choosing” the immoral action (see, e.g. Kramlich, 2003).

Some of the landmark United States Supreme Court cases that would be relevant in a legal analysis of proposals to abandon the DDR would include:

-

•

Cruzan v. Director, Mo. Dept of Health, 497U.S. 261 (1990): requiring “clear and convincing evidence” of a patient’s wishes for the removal of life support;

-

•

Vacco v. Quill, 521 US 793 (1997): holding that states have legitimate interests in preventing doctors from assisting their patients to die, even those who are terminally ill or in great pain;

-

•

Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 US 702 (1997): holding physician-assisted suicide is not protected by the Due Process Clause;

-

•

Gonzales v. Oregon, 546 US 243 (2006): holding U.S. Attorney General could not enforce the federal Controlled Substances Act against Oregon physicians who prescribed drugs for the assisted suicide of the terminally ill in accord with Oregon law;

-

•

In re Quinlan, 355 A.2d 647 (N.J. 1976): finding the removal of “extraordinary means of treatment,” namely a ventilator, would not constitute the form of homicide known as euthanasia. Because the patient’s father, seeking a protective order for the removal of a ventilator from his daughter was Roman Catholic, the New Jersey Supreme Court quoted extensively from an address by Pope Pius XII regarding the principle of double effect in the withdrawal of extraordinary means of life-sustaining treatment. 4

Proposed policies to abandon the DDR and to alter organ procurement policy require careful medical, legal, and ethical analyses that are beyond the scope of this article. What follows is a survey of current statutes, regulations, and court decisions aimed at setting out the legal landscape for the benefit of those who seek to grapple with the issue of brain death and the myriad of related policies.

Origins of the Uniform Determination of Death Act

The law originally considered death to be an event, not a process. 5 Traditionally, this event was defined as having taken place when all major organ systems of the body ceased to function––the heart, lungs, and the brain being so interdependent that the death of one of the components would rapidly lead to the death of others when the individual lacks cardiac and respiratory support systems (Skegg, 1974, 130, 133). However, the mid-twentieth century saw the advent of respirators, defibrillators, organ transplantation, and other technological advancements that began to call into question society’s understanding of death (Powner, Ackerman, and Grenvik, 1996, 1219).

In May 1968, The Journal of the American Medical Association published an editorial describing a dilemma about vital organ transplants:

It is obvious that if . . . organs [such as the liver and heart] are taken long after death, their chance of survival in another person is minimized. On the other hand, if they are removed before death can be said to have occurred by the strictest criteria that one can employ, murder has been done. (American Medical Association, 1968, 539–540)

Months later, in August 1968, the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death published a report that set out the first formal definition of brain death (Ad Hoc Committee, 1968, 337–340). According to these criteria, individuals who had sustained traumatic brain injury that caused them to be in an irreversible coma, and had lost the ability to breathe spontaneously, would be considered dead. The two justifications the committee provided for this new neurological determination of death were (1) to allow for withdrawing life support from people who had sustained irreversible and devastating brain injury and (2) to address obstacles to organ transplantation (Ad Hoc Committee, 1968, 337).

A task force of physicians, philosophers, and bioethicists subsequently took care to explain that the neurological standard was not created solely for the purpose of facilitating increased organ transplantation (The Task Force on Death and Dying, 1972, 48, 51). Nevertheless, others have described the Harvard committee’s actions as having been undertaken through a moral lens (rather than a biological one)—establishing the determination of death criteria based on the underlying purpose they would serve in allowing organ transplantation to take place (Veatch, 2004, 261, 267).

The efforts to reach a consensus on the definition of brain death from the legal perspective led to the drafting of the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) in 1980 (National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws [NCCUSL], 1980, prefatory note). That model legislation was published the following year by a presidential commission in a report entitled “Defining Death: A Report on the Medical, Legal and Ethical Issues in the Determination of Death” (President’s Commission, 1981). The UDDA was approved by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, the American Medical Association, the American Bar Association, and the President’s Commission on Medical Ethics. These groups endorsed the following model legislation, and recommended that it be adopted in all jurisdictions in the United States:

Uniform Determination of Death Act

An individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem, is dead. A determination of death must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.

III. BRAIN DEATH LAWS ACROSS THE UNITED STATES

Determination of Death Statutes

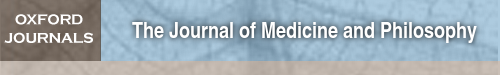

All 50 states have recognized the concept of brain death as a matter of law, whether by statute, regulation, or judicial decision. However, there exist many variations among their treatment of the subject, starting with the statutes governing determination of death. Thirty-eight states have adopted the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) word-for-word, or with very similar wording. 6 These states include Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Delaware, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming, and Washington (see fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

UDDA laws across the United States.

Nine other states––Connecticut, Florida, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, New Jersey, and Texas––have also adopted the UDDA, with the express qualification that the neurological criteria for death may only be used where an individual’s respiratory and circulatory functions are maintained by artificial means, a status that is (perhaps inaccurately) termed “life support.” 7 All other deaths must be determined solely due to irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions. While this language may not have medical significance, it could have political or policy significance in the legislative process or in informing a court’s decision-making process. Florida’s version reads as follows:

For legal and medical purposes, where respiratory and circulatory functions are maintained by artificial means of support so as to preclude a determination that these functions have ceased, the occurrence of death may be determined where there is the irreversible cessation of the functioning of the entire brain, including the brain stem, determined in accordance with this section (Fla. Stat. § 382.009[1], [2013]).

Arizona has not codified a recognition of brain death or any particular standard for the determination of death. Its law simply states that the determination of death must be made “in accordance with accepted medical standards” (Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 14–1107, [2007]). Unlike the other states, it does not define death as cessation of any specific functions.

Virginia is the only state that does not allow brain death in and of itself to be the determinative factor in pronouncing death. The law focuses on the spontaneous nature of cardiorespiratory functions, and whether those functions will ever again be able to occur spontaneously. A recent amendment requires the opinion of one specialist instead of two physicians. Death is defined to occur at the time when cardio-respiratory functions cease, or in the case of brain death, when brain function and spontaneous cardio-respiratory functions have all ceased:

In the opinion of a physician, who shall be duly licensed and a specialist in the field of neurology, neurosurgery, electroencephalography, or critical care medicine, when based on the ordinary standards of medical practice, there is the absence of brain stem reflexes, spontaneous brain functions and spontaneous respiratory functions and, in the opinion of such specialist, based on the ordinary standards of medical practice and considering the absence of brain stem reflexes, spontaneous brain functions and spontaneous respiratory functions and the patient’s medical record, further attempts at resuscitation or continued supportive maintenance would not be successful in restoring such reflexes or spontaneous functions, and, in such event, death shall be deemed to have occurred at the time when these conditions first coincide. (Va. Code Ann. § 54.1–2972 [2014]) 8

In North Carolina, brain death as the basis for determination of death is merely permissive, not conclusive (NC Gen. Stat. § 90–323, [2012]). Recognition of brain death does not supersede other medically recognized criteria for death determination.

Organ transplantation provisions

Whether a patient is a candidate for organ donation is a factor in several states’ determination of death laws. Several states’ statutes specifically require that a determination of death on account of cessation of function of the brain or brain stem shall be pronounced before removal of life support and/or organ removal for purposes of transplantation. States with such laws include Hawaii, Maryland, and New Mexico. 9 For example, Hawaii law provides:

In the event that artificial means of support preclude a determination that respiratory and circulatory functions have ceased . . . death shall be pronounced before artificial means of support are withdrawn and before any vital organ is removed for purposes of transplantation. (HI Rev. Stat. § 327C-1(b), [2013)])

The laws of Hawaii, Louisiana, and New Jersey expressly incorporate the provisions of the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, 2006) that the physician(s) making the death determination cannot be involved in the future transplant of organs from the person, or in the treatment of a recipient of an organ from the person. 10

The Maryland codification of the UDDA explicitly states that it does not apply to voluntary vital organ removal while the donor is alive, even “if the individual gives informed consent to the removal.” Consistent with the DDR currently implicit in all state laws, Maryland’s statute provides that “a pronouncement of death shall be made before any vital organ is removed for transplantation” (MD Code, Health - General, § 5–202).

Miscellaneous variations in state statutes

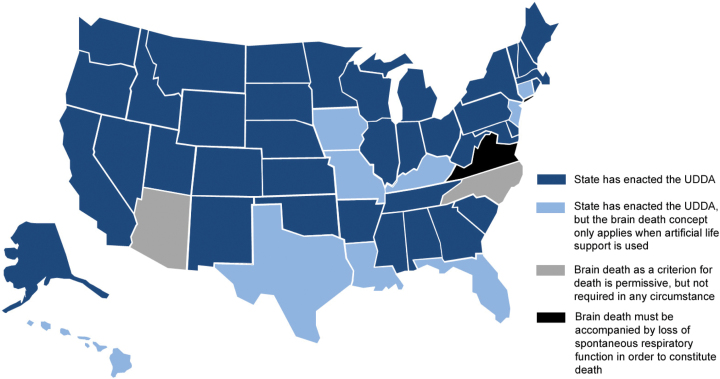

A patchwork of states has enacted a variety of miscellaneous provisions (see fig. 2). The Kentucky version of the UDDA defines its criteria as only the “minimal conditions” for a death determination. The primary considerations are “the usual and customary standards of medical practice” (KY Rev. Stat. § 446.400, [2009]).

Fig. 2.

Miscellaneous state laws.

Georgia provides that a person who makes a determination of death in good faith will not be liable for civil damages or subject to criminal prosecution as a result of making the determination (O.C.G.A. 31-10-16(b), [2010]). Georgia also allows for the use of “other medically recognized criteria” aside from those adopted from the UDDA (namely, “(1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory function, and (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem”). 11

Twelve states require that only specific health professionals make determinations of death. 12 Only three of those states––Florida, New Jersey, and Virginia––require that a specialist in neuroscience or related field must confirm when brain death has occurred. 13 New Jersey’s statute specifically states that the time of death due to cessation of function of the brain will be at the conclusion of the examination leading to the determination (NJ Rev. Stat. § 26:6A-4, [2013]).

New Jersey’s statute provides that if an authorized physician has reason to believe that an individual on artificial ventilation has religious opposition to determination of death based on neurological criteria, then death can only be pronounced on the basis of cardio-respiratory criteria (NJ Rev Stat § 26:6A-5, [2013]). New York requires that all hospitals have a policy for “reasonable accommodation” of such religious or moral opposition (10 NYCRR 400.16). And California similarly requires hospitals to have a policy that makes “reasonable efforts to accommodate those religious and cultural practices and concerns” about brain death. Notably, however, California’s statute then states that the hospital’s determination of what is reasonable “shall consider the needs of other patients and prospective patients in urgent need of care” (Cal. Health and Safety Code § 1254.4, [2008]).

Oklahoma is the only state that expressly requires that “all reasonable attempts to restore spontaneous circulatory or respiratory functions” first be made (O.S. § 63–3122, [2013]). It also specifies that its law “does not concern itself with living wills, death with dignity, euthanasia, rules on death certificates, maintaining life support beyond brain death in cases of pregnant women or of organ donors, and protection for the dead body” (O.S. § 63–3123, [2013]).

Oregon is the only state to specifically address “fetal death” in its determination of death statute:

For purposes of this section as it relates to fetal death, heartbeats shall be distinguished from transient cardiac contractions and breathing shall be distinguished from fleeting respiratory efforts or gasps. (OR Rev. Stat. § 432.300, [2011])

Idaho has codified the UDDA, but the usual “accepted medical standards” criterion has an additional qualification of being limited to the “usual and customary procedures of the community in which the determination of death is made” (ID Code § 54–1819, [2011]). Beyond the medical malpractice law concept of the “locality rule,” Idaho is the only state whose statute expressly requires adherence to the custom of a specific individual community. This could conceivably have legal implications, for example, in instances where a physician might seek to breach the DDR.

Cases involving determination of death

In the 1983 ruling of In re Haymer, an Illinois Appeals Court affirmed a declaratory judgment permitting a hospital to remove a 7-month-old brain dead patient from a mechanical ventilation system (In re Haymer, 115 Ill. App.3d 349, [1983]). In adopting the concept that whole brain death is the death of the person, the court focused on brain death’s widespread acceptance in the medical field:

In resolving the issue, we recognize the nearly unanimous consensus of the medical community that when the whole brain no longer functions, the person is dead. In addition, we take into account that the prevailing practice of the medical community nationwide is to regard total brain death as the death of the person. (In re Haymer, 353–354)

Washington adopted the brain death criteria judicially, as opposed to by statute. In the case of In re Welfare of Bowman, the Supreme Court of Washington unanimously held in 1980 that “it is for the law, rather than medicine, to define the standard of death,” but that “it is for the medical profession to determine the applicable criteria, in accordance with accepted medical standards, for deciding whether brain death is present” (In re Welfare of Bowman, 94 Wash. 2d 407, [1980]).

In Lovato v. District Court In and For Tenth Judicial Dist., Colorado adopted the brain death standard in 1979, describing it as “a more complete definition of death.” 14 It concluded that “to act otherwise would be to close our eyes to the scientific and medical advances made worldwide in the past two or three decades.” 15

In the 1984 case of People v. Eulo, the defendant shot his girlfriend in the head during an argument, and she was declared brain dead several days later (People v. Eulo, 63N.Y.2d 341, [1984]). Her organs were harvested, and her heartbeat thereafter ceased. The defendant argued that his victim had ultimately died not as a result of his actions, but because of the removal of her vital organs. He argued that the brain death standard should not go so far as to shoulder him with criminal liability for homicide. The court disagreed:

If the victims were properly diagnosed as dead, of course, no subsequent medical procedure such as the organ removals would be deemed a cause of death. If victims’ deaths were prematurely pronounced due to a doctor’s negligence, the subsequent procedures may have been a cause of death, but that negligence would not constitute a superseding cause of death relieving defendants of liability. (People v. Eulo, 359)

Brain death during pregnancy

Case law

Maternal brain death came into the national spotlight in 2013 when a 33-year-old Texan woman named Marlise Muñoz, who was 14 weeks pregnant, was declared brain dead after suffering a pulmonary embolism (see Lavandera, Rubin, and Botelho, 2014).

Her husband asked doctors to withdraw life-sustaining treatment, claiming that Muñoz had expressed to family members in the past that she was opposed to receiving artificial life support. The hospital refused, citing a 1977 law, Texas Health and Safety Code Sec. 166.049, that states: “A person may not withdraw or withhold life-sustaining treatment . . . from a pregnant patient” (Tex. H.S. Code Ann. §166.049, [2014]).

After 2 months on artificial life support, when the unborn child had reached 23 weeks gestation, a court ordered that medical treatment be withdrawn, and the baby did not survive. In a one-page order, the court stated that the pregnant patient statute barring removal of “life-sustaining treatment” did not apply. He reasoned that “applying the standards used in determining death set forth in Sec. 671.001 of the Texas Health and Safety Code, Mrs. Muñoz is dead.” 16 As characterized by one reporter, the court ruled that Muñoz “was brain dead and therefore legally dead” (Fernandez, 2014). The judge’s ruling therefore seems to imply that the term “life-sustaining treatment” refers only to a pregnant mother who is alive, and not to the unborn child.

While each case regarding the prospects for live birth of an unborn child vary depending on a myriad of factors, including the gestational stage of the pregnancy, it must be noted that babies have been successfully delivered from their brain dead mothers. In December 2013, a similar story began to play out in Victoria, British Columbia, although the pregnancy was much closer to viability. Robyn Benson, 22 weeks pregnant, suffered a brain hemorrhage and was declared brain dead. Unlike the Muñoz case, Benson’s husband Dylan and the doctors agreed to keep the pregnant mother on a ventilator until the baby could be delivered by cesarean section. The Bensons’ son Iver was delivered on February 8, 2014, and Mrs. Benson’s ventilator was removed shortly thereafter. 17

The 1986 case of University Health Services v. Piazzi is another of the few reported cases in the United States dealing with maternal brain death. 18 A Georgia hospital petitioned to keep a brain dead pregnant woman, Donna Piazzi, on artificial respiration until the birth of her unborn child, over the objections of her husband and family. In granting the petition, the court determined that Donna lacked the power to terminate life-sustaining medical treatment during her pregnancy even if she had executed a living will, relying on the Georgia Natural Death Act, which invalidates advance directives during pregnancy (Ga. Code Ann., § 31-32-2, [2007]).

The court also rejected the argument that Donna had a constitutional right to refuse treatment and to terminate the pregnancy, because she had no longer possessed privacy rights due to her status as being brain dead. The court found that public policy in Georgia requires the maintenance of artificial respiration for a brain dead mother, as long as a reasonable possibility exists that the fetus can develop and survive, which the court determined was the case. Unfortunately, the child died of organ failure within 2 days of birth.

With the advance of technology, the issue of brain death and pregnancy continues to garner headlines. In December 2014, Ireland’s second highest court ruled that a hospital must discontinue artificial life support for a pregnant woman who was 18-weeks pregnant based on medical testimony that the unborn child had no chance to be delivered alive (Winter, 2014).

On the other hand, months later, a first in the United States was achieved when an unborn child was delivered alive on April 4, 2015, by a brain dead mother, who had been on artificial life support for 54 days at Methodist Woman’s Hospital in Omaha, Nebraska. Her healthy baby boy left the hospital 2 months later. In that instance, the family consented to continuation of the artificial life support for their pregnant daughter, who suffered brain death at approximately 22 weeks gestation (Tan, 2015).

State statutes

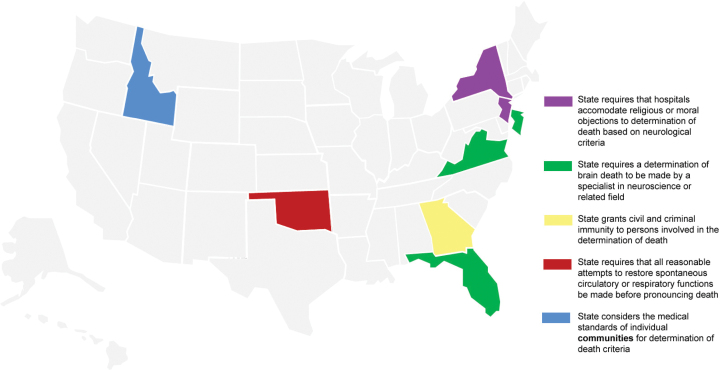

State laws addressing brain death of a pregnant woman vary widely (see fig. 3). Currently, twelve states have laws similar to the one at issue in the Texas Muñoz case––absolute and inflexible. These states include Alabama, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin (Greene and Wolfe, 2012). These 12 state laws automatically invalidate a woman’s advance directive, regardless of the gestational age or state of health of the unborn child. For example, South Carolina’s law states, “If a declarant has been diagnosed as pregnant, the Declaration [regarding the withdrawal of artificial life support] is not effective during the course of the declarant’s pregnancy” (SC Code § 44-77-70, [2013]).

Fig. 3.

Laws on brain death during pregnancy.

Four additional states have pregnancy restrictions like Texas’s, with the qualification that the unborn child must be considered viable for continued life-sustaining treatment to be required. These states include Colorado, Delaware, Florida and Georgia (Greene and Wolfe, 2012, n. 59).

Fourteen states follow the model of the “Uniform Rights of the Terminally Ill Act,” which requires that a pregnant woman be given life-sustaining treatment if she is pregnant and it is “probable” that the unborn child will develop to the point of “live birth.” These states include Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Illinois, Iowa, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and South Dakota. Four of these states (New Hampshire, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, and South Dakota) provide exceptions if the life-sustaining treatment would be “physically harmful to the pregnant woman,” or “will cause pain to the pregnant woman that cannot be alleviated by medication.” 19

In five states, laws allow the woman or her proxy to direct what she would want if she is pregnant, providing in the statutory living will form that a woman should think about this possibility and indicate what she would want. These states include Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Vermont (Greene and Wolfe, 2012, n. 59).

In the 2014 legislative session, a bill was passed in the legislature of Louisiana, HB 1274 (2014) that amends current laws on life-sustaining treatment to add the following emphasized language:

It is the policy of the state of Louisiana that human life is of the highest and inestimable value through natural death. When interpreting this Part, any ambiguity shall be interpreted to preserve human life, including the life of an unborn child if the qualified patient is pregnant and an obstetrician who examines the woman determines that the probable postfertilization age of the unborn child is twenty or more weeks and the pregnant woman’s life can reasonably be maintained in such a way as to permit the continuing development and live birth of the unborn child, and such determination is communicated to the relevant classes of family members and persons designated in R.S. 40:1299.58.5. (La. Act 850 [signed June 23, 2014])

As of July 2014, the laws of 14 states and the District of Columbia were completely silent on the subject of pregnancy and advanced directives. The states include California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

IV. CRITICISMS OF THE CURRENT STATE-BASED MODEL

Mounting Public Mistrust of the Role of Organ Transplantation

It has been claimed by a minority of critics that brain death is a legal fiction, formulated simply to solve the moral problem of harvesting organs from a potentially living body (Miller and Truog, 2008; Shah and Miller, 2010, 540; Sade, 2011). Since its inception, proponents of the neurological criteria for determining death have been accused of having a hidden agenda: meeting the growing need for vital organ donations.

As of April 2014, there were 122,193 waiting list candidates for organ transplants. Only 28,951 transplants took place in 2013. Of those transplants, nearly 80% of the organs were procured from deceased donors (as opposed to organ donation from a living friend or relative) (22,965) (US Dept. of Health and Human Services, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network). The imbalance of supply for the increasing demand demonstrates the importance of clearly defining determination of death in organ procurement for transplantation.

According to some commentators, the skyrocketing demand for organ transplants in the late twentieth century created a need for what was at first considered a paradox: a “living” body that was also a dead donor (Sade, 2011). In the words of one court:

The movement in law towards recognizing cessation of brain functions as criteria for death followed this medical trend. The immediate motive for adopting this position was to ease and make more efficient the transfer of donated organs. Organ transfers, to be successful, require a “viable, intact organ.” Once all of a person’s vital functions have ceased, transferable organs swiftly deteriorate and lose their transplant value. (People v. Eulo, 352, n. 42)

The recognition of the brain death criteria seemed to solve the dilemma by acknowledging that bodies can be caused by technological means to function artificially after death. But many critics have questioned whether individuals can be truly dead when they have sustained neurological injury indicating total brain failure but continue to circulate blood, breathe, and perform other biological functions with the aid of mechanical ventilation. Illinois’s brain death statute is codified within its Anatomical Gift Act, suggesting that some lawmakers consider their purposes to be intentionally linked (755 ILCS 50/1, [2013]).

Indeed, there has long been public concern for the potential conflict of interest underlying end-of-life care to potential organ donors (Lazar et al., 2001, 834). A 2006 survey found that 25% of respondents expressed fears that signing a donor card would result in physicians purposely doing less to save their lives (DuBois, 2009, 13, 19). The unfortunate information gap between the medical community and the public needs to be addressed in order to rebuild trust in the organ procurement system. 20

A certain case that continues to receive national attention involves a young girl named Jahi McMath, age 13. Jahi had tonsil surgery on December 9, 2013, at a hospital in Oakland, California. After significant blood loss, cardiac arrest, and then alleged observation of complete loss of blood flow to her brain, doctors declared McMath brain dead on December 12, 2013. The family reportedly asked that she remain on a ventilator for 48 hours after that declaration. The ventilator was maintained for approximately 8 days, but when the hospital attempted to remove the ventilator, the family retained an attorney and asked the hospital to keep McMath on a ventilator through Christmas.

The parents also asked both federal and state courts to intervene, and the hospital was ordered to continue the use of the ventilator until January 7, 2014. The federal court declined, however, to require the hospital to insert a gastric tube and tracheostomy tube (Kemp, 2014).

McMath was then reportedly transferred to an undisclosed long-term care facility in New Jersey, where she was placed on a ventilator and a feeding tube. The complaint filed by her parents in federal court alleged numerous violations of her civil rights under the Constitution, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Ten months after initial tests found no brain activity, further testing was reported by the family’s medical experts to show severe brain damage, but not brain death. The attorney for the family is taking steps to have the state of California revoke Jahi’s death certificate, so that she can be returned to her home in Oakland and treated with the assistance of state programs (DeBolt, 2014). This unique case may indicate a need for more clearly defined and rigorous hospital protocol in the determination of brain death, especially in regard to pediatric patients.

Variability of Brain Death Diagnosing Criteria

The Uniform Determination of Death Act is worded in such a way that ambiguity is a virtual guarantee. Because it states that brain death should be determined “according to medical standards,” the specific tests used to diagnose brain death vary from hospital to hospital (NCCUSL, 1980). A 2008 study, which included 41 of the nation’s top hospitals, found widespread and worrisome variability in how doctors and hospitals were determining who met the criteria (Greer et al., 2008, 284–289). Its conclusions were as follows:

Major differences exist in brain death guidelines among the leading neurologic hospitals in the United States. Adherence to the American Academy of Neurology guidelines is variable. If the guidelines reflect actual practice at each institution, there are substantial differences in practice which may have consequences for the determination of death and initiation of transplant procedures.

Is this a problem? If so, what should be done? There are several approaches that may be undertaken. Some scholars have suggested that brain death is a mere legal fiction designed solely for the purpose of satisfying the DDR, such that the concept should simply be abandoned. 21 Instead, they argue, retrieving organs from the dying but still alive patient is morally defensible, and society should attempt to embrace it. 22

Other scholars have argued persuasively that “proposals to drop the DDR are radical recommendations to cross lines we have never crossed before” (DuBois, 2002, n. 1), and that such proposals should be rejected because, inter alia, public support and trust in the organ donation process is already attenuated and fragile:

It remains precarious and can be shaken dramatically by highly publicized donation scares such as those following a BBC Panorama exposé in 1980, CBS’s 1997 report on 60 Minutes about the Cleveland Clinic’s consideration of a DCDD protocol, and the story of the California transplant surgeon who allegedly wrote terminal care orders for an organ donor in 2006. Many people harbor a fear that physicians have a greater interest in procuring their organs than in their welfare. They need the reassurance provided by the DDR. (Bernat, 2013, 1289–91)

Another approach proposes maintaining current policies and procedures, but implementing a national legal standard for executing them. The UDDA and state laws do not specify any practical clinical standard for the determination of brain death, so the criteria used vary from hospital to hospital. Consequently, a patient who is dead in one state might be considered alive in another (Goldsmith, 2007, 918–9).

Proponents of a national standard believe that its implementation would foster equal treatment for potentially brain dead patients, minimize the potential for inconsistent legal outcomes, and provide medical practitioners a unified set of procedures with which to determine death (Eun-Kyoung et al., 2008). Some suggest that subjecting the standard to legal codification would ensure that it is tested by substantial debate and scrutiny by a variety of experts of the medical, ethical, and legal realms. This alone may warrant the national standard approach, as some hospitals maintain their criteria a secret (Fry-Revere, Reher, and Ray, 2010, 68). Of course, the difficulty with implementing a national standard would be inherent in the political process it would have to endure. 23

V. CONCLUSION

Legal authorities have struggled to resolve the medical and ethical quandaries that surround brain death since its inception. The current laws and medical implementation have subtle variations across the United States, and the resulting controversies continue to engender national interest and debate. Any attempts to reconcile inconsistencies in various state laws and/or to address the increasing demand for human organs should proceed with the utmost attention to balancing the rigors of medical accuracy with sound ethical principles consistent with a philosophical anthropology that recognizes the dignity of the human person.

Clarity in law and policy based on sound medical ethics will go a long way toward bridging the gap between the medical community and an increasingly wary public in order to rebuild trust in regard to organ procurement and donation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Bioethics Defense Fund (www.BDFund.org) is a public interest organization whose mission is to put law in the service of human life via model legislation, litigation, and professional education in the fields of law and medicine.

NOTES

This article presents a survey of existing state and federal law in the United States addressing the determination of death. The survey is not, of course, an endorsement of any particular law, policy, statute, or decision. The authors advocate for the inherent dignity of every human life, and would not support any law or policy that would abrogate the DDR. Because the authors are not physicians, scientists, or philosophers, this survey should not be interpreted as support or opposition for any particular medical criteria for determining death.

See generally Robertson (1999). See also Bernat (2013, 1289): “The DDR is not a law but an informal, succinct standard highlighting the relationship between the two most relevant laws governing organ donation from deceased donors: the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act and state homicide law. The DDR states that organ donation must not kill the donor; thus, the donor must first be declared dead. It applies only to organ donation from deceased donors, not to living donation, such as that of one kidney or a partial liver.”

“The claim that perhaps the DDR is not being respected—despite the fact that donors are commonly described as ‘deceased’—is the tautological result of assuming that these individuals may be alive. Thus, it is important to evaluate both whether and how these practices may be currently violating the DDR and to examine whether such a violation is acceptable” (citing Menikoff, 1998; see also Rady, Verheijde, and McGregor, 2007; Miller and Truog, 2008).

See also Roe v. Wade, 410 US 113 (1973)––finding that a “right to privacy” under the Due Process Clause extends to a woman’s decision to terminate her pregnancy, and finding that the unborn child is not a “person” for purposes of the Due Process Clause; and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 505 US 833 (1992)––reaffirming the essential holding of Roe under the auspices of the “liberty” interests of the Due Process Clause: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.”

Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th ed., s.v. “death,” (1968): 488; cf. DuBois, 2002, setting forth an argument that death is a “state,” rather than an event or a process.

Ala. Code § 22-31-1 (2013); Alaska Stat. § 13.06.035. (2007); Ark. Code Ann. § 20-17-101 (2010); Cal. Health and Safety Code § 7180 Art. 1 (2009); Col. Rev. Stat. 12-36-136 (2013); 24 DE Code § 1760 (2012); O.C.G.A. 31-10-16 (2010); ID Code § 54–1819 (2011); 755 ILCS 50/1 (2013); Ind. Stat. 1-1-4-3; Kan. Stat. Ann. 77–205; 22 ME Rev. Stat. § 2811 (2012); MD Code, Health - General, § 5–202; Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 190B § 1–107; MI Comp L § 333.1033 (2009); MN Stat. § 145.135 (2013); MS Code § 41-36-3 (2013); MT Code § 50-22-101 (2011); NE Code § 71–7202 (2012); NV Rev. Stat. § 451.007 (2013); NH Rev. Stat. § 141-D:2 (2013); NM Stat. § 12-2-4 (2013); 10 NYCRR 400.16; ND Stat. § 23-06.3; Ohio Rev. Code § 2108.40 (2013); O.S. § 63–3122 (2013); OR Rev. Stat. § 432.300 (2011); 35 P.S. § 10203; RI Gen. L. § 23-4-16 (2012); S.C. Code Ann. § 44-43-460 (2012); S.D. Codified Laws § 34-25-18.1 (2013); TN Stat. § 68-3-501 (2010); UT Stat. § 26-34-2; 18 VT Stats. § 5218 (2011); WV Code § 16-10-1 (2012); WI Stat. § 146.71 (2012); WY Stat. § 35-19-101 (2013).; In re Welfare of Bowman, 94 Wash.2d 407 (1980).

Conn. Gen. Stat. § 19a-504a (2012); Fla. Stat. § 382.009 (2013); HI Rev. Stat. § 327C-1 (2013); Iowa Code § 702.8 (2013); KY Rev. Stat. § 446.400 (2009); La. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 9:111 (2012); Mo. Rev. Stat. § 194.005 (2013); NJ Rev. Stat. § 26:6A-3 (2013); Tex. Health and Safety Code § 671.001 (2011).

This law was amended and reenacted in the 2014 session to require the opinion of one specialist instead of two physicians. The requirement of cessation of spontaneous respiratory function remains, which sets Virginia apart from all other states.

HI Rev. Stat. § 327C-1 (2013); MD Code, Health - General, § 5–202; NM Stat. § 12-2-4 (2013).

HI Rev. Stat. § 327C-1 (2013); La. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 9:111 (2012); NJ Rev. Stat. § 26:6A-4(c) (2013).

O.C.G.A. 31-10-16 (2010). Subsection (c) provides, “The criteria for determining death authorized in subsection (a) of this Code section [UDDA criteria] shall be cumulative to and shall not prohibit the use of other medically recognized criteria for determining death.”

FL Stat. § 382.009 (2013); O.C.G.A. 31-10-16 (2010); HI Rev. Stat. § 327C-1 (2013); Iowa Code § 702.8 (2013); KY Rev. Stat. § 446.400 (2009); La. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 9:111 (2012); Mo. Rev. Stat. § 194.005 (2013); NJ Rev. Stat. § 26:6A-4 (2013); NC Gen. Stat. § 90–323 (2012); Ohio Rev. Code § 2108.40 (2013); Tex. Health and Safety Code § 671.001 (2011); Va. Code Ann. § 54.1–2972 (2013).

FL Stat. § 382.009 (2013); NJ Rev. Stat. § 26:6A-4 (2013); Va. Code Ann. § 54.1–2972 (2014).

Lovato v. District Court In and For Tenth Judicial Dist., 198 Colo. 419, 425 (1979).

Ibid. at 432.

Munoz v. John Peter Smith Hospital, No. 096-270080-14, 96th Judicial District, Tarrant County, Texas (Jan. 24, 2014). The cited Texas statute to determine death states, “If artificial means of support preclude a determination that a person’s spontaneous respiratory and circulatory functions have ceased, the person is dead when, in the announced opinion of a physician, according to ordinary standards of medical practice, there is irreversible cessation of all spontaneous brain function. Death occurs when the relevant functions cease” (Tex. H.S. Code. Ann. §671.001 [2014]).

See NBC News, 2014, Brain-dead Canadian woman dies after giving birth to boy, Feb. 11, 2014 [On-line]. Available: http://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/brain-dead-canadian-woman-dies-after-giving-birth-boy-n27741 (accessed February 20, 2016).

University Health Services v. Piazzi, Superior Court of Georgia, Richmond County. No. CV86-RCCV-464, Aug. 4, 1986.

See e.g. PA Act 169, § 5429 (2006).

See also Lewis (2012).

Legal fictions, once famously described as false statements not intended to deceive, have been utilized to facilitate the operation of law since its beginnings (Smith, 2007, 1435). A classic example of a legal fiction is the presumption that jurors in a trial will faithfully obey a judge’s instruction to ignore evidence that was incorrectly revealed to them. See, e.g. Francis v. Franklin, 471 US 307, 324n.9 (1985). Such fictions are accepted because they are necessary—they serve the utilitarian purpose of creating consistency in the application of the laws that invoke them (Harmon, 1990).

See Section I of this article. See also Caplan, Magnus, and Wilfond (2014).

Additionally, supporters of states’ rights may reject the idea of a federal law, in consideration of police power: the autonomy of the individual states in regulating for the health and general welfare of the people. See Wilkinson (2009, 305, 311).

REFERENCES

- Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death 1968. A definition of irreversible coma. The Journal of the American Medical Association 205:337–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association. 1968. What and when is death? The Journal of the American Medical Association 204:539–40. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold R. M. and Youngner S. J.. 1993. The dead donor rule: Should we stretch it, bend it, or abandon it? Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 3:263–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat J. L. 2013. Life or death for the dead-donor rule? The New England Journal of Medicine 369:1289–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan A. L., Magnus D. C., Wilfond B. S. 2014. Accepting brain death. The New England Journal of Medicine 370:891–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBolt D. 2014, October 27. Jahi McMath: New tests may not be enough to declare her alive, experts say San Jose Mercury News [On-line]. Available: http://www.mercurynews.com/ci_26799085/jahi-mcmath-new-tests-may-not-be-enough (accessed February 19, 2016).

- DuBois J. M. 2002. Is organ procurement causing the death of patients? Issues in Law & Medicine 18:21–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2009. Increasing rates of organ donation: Exploring the Institute of Medicine’s boldest recommendation. The Journal of Clinical Ethics 20:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eun-Kyoung C., Fredland V., Zachodni C., Lammers J. E., Bledsoe P., Helft P. R. 2008. Brain death revisited: The case for a national standard. The Journal of Law, Medicine, & Ethics 36:824–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M. 2014, January 26. Texas woman is taken off life support after order The New York Times; [On-line]. Available: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/27/us/texas-hospital-to-end-life-support-for-pregnant-brain-dead-woman.html?_r=0 (accessed March 2, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Fry-Revere S., Reher T., Ray M. 2010. Death: A new legal perspective. Journal of Contemporary Health Law and Policy 27:1–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith J. L. 2007. Wanted! Dead and/or alive: Choosing among the not-so-uniform statutory definitions of death. University of Miami Law Review 61:871–930. [Google Scholar]

- Greene M. and Wolfe L. R.. 2012. Pregnancy exclusions in state living will and medical proxy statutes. Reproductive Laws for the 21st Century Papers. Center for Women Policy Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Greer D. M., Varelas P. N., Haque S., Wijdicks E. F. 2008. Variability of brain death determination guidelines in leading US neurologic institutions. Neurology 70:284–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon L. 1990. Falling off the vine: Legal fictions and the doctrine of substituted judgment. Yale Law Journal 100:1–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp D. S. 2014, January 6. On brain death and civil rights Justia [On-line]. Available: http://verdict.justia.com/2014/01/06/brain-death-civil-rights (accessed February 19, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Kramlich M. 2003. The abortion debate thirty years later: From choice to coercion. Fordham Urban Law Journal 31:783–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavandera E. Rubin J. and Botelho G., 2014, January 24. Texas judge: Remove brain-dead woman from ventilator, other machines CNN [On-line]. Available: http://www.cnn.com/2014/01/24/health/pregnant-brain-dead-woman-texas/ (accessed February 19, 2016).

- Lazar N. M., Shemie S., Webster G. C., Dickens B. M. 2001. Bioethics for clinicians: 24 brain deaths. Canadian Medical Association Journal 164:833–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P. 2015. Total brain death is a valid criterion of death Ethika Politika. Available: http://ethikapolitika.org/2015/01/15/total-brain-death-valid-criterion-death/ (accessed February 18, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. P. 2012. Suit alleges donor network pressured staff to declare live patients brain dead The Lewis Law Firm [On-line]. Available: http://lewis-firm.com/2012/09/suit-alleges-donor-network-pressured-staff-to-declare-live-patients-brain-dead/ (accessed February 19, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Menikoff J. 1998. Doubts about death: The silence of the Institute of Medicine. Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics 26:157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller F. G. and Truog R. D.. 2008. Rethinking the ethics of vital organ donations. Hastings Center Report 38:38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller F. G., Truog R. D., Brock D. W. 2010. The dead donor rule: Can it withstand critical scrutiny? The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 35:299–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL) 2006. Revised Uniform Anatomical Gift Act [On-line]. Available: http://www.uniformlaws.org/shared/docs/anatomical_gift/uaga_final_aug09.pdf (accessed February 20, 2016).

- NBC News 2014, February 11. Brain-dead Canadian woman dies after giving birth to boy [On-line]. Available: http://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/brain-dead-canadian-woman-dies-after-giving-birth-boy-n27741 (accessed February 20, 2016).

- Powner D. J., Ackerman B. M., Grenvik A. 1996. Medical diagnosis of death in adults: Historical contributions to current controversies. Lancet 348:1219–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research 1981. Defining Death: Medical, Legal and Ethical Issues in the Determination of Death [On-line]. Available: https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/bitstream/handle/10822/559345/defining_death.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed February 20, 2016).

- Rady M. Y., Verheijde J. L., McGregor J. 2007. Organ donation after cardiac death: Are we willing to abandon the dead-donor rule? Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 8:507–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J. A. 1999. The dead donor rule. Hastings Center Report 29:6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguiz-Arias D., Smith M. J., Lazar N. M. 2011. Donation after circulatory death: Burying the dead donor rule. The American Journal of Bioethics 11:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sade R. M. 2011. Brain death, cardiac death, and the dead donor rule. The Journal of the South Carolina Medical Association 107:146–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. H. and Miller F. G.. 2010. Can we handle the truth? Legal fictions in the determination of death. American Journal of Law & Medicine 36:540–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skegg D. 1974. Irreversibly comatose individuals: “Alive” or “dead”? The Cambridge Law Journal 33:130–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. J. 2007. New legal fictions. Georgetown Law Journal 95:1435–95. [Google Scholar]

- Tan A. 2015, June 10. Baby delivered by brain-dead mother on life-support for 54 days leaves hospital ABC News, Good Morning America [On-line]. Available: http://abcnews.go.com/Health/baby-delivered-brain-dead-mother-life-support-54/story?id=31676251 (accessed February 20, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- The Task Force on Death and Dying of the Institute of Society, Ethics and the Life Sciences 1972. Refinements in criteria for the determination of death: An appraisal. The Journal of the American Medical Association 221:48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truog R. D., Miller F. G., Halpern S. D. 2013. The dead-donor rule and the future of organ donation. The New England Journal of Medicine 369:1287–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health & Human Services (HRSA) Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network [On-line]. Available: http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov (accessed February 19, 2016).

- Veatch R. M. 2004. Abandon the dead donor rule or change the definition of death? Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 14:261–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson III J. H. 2009. Of guns, abortions, and the unraveling rule of law. Virginia Law Review 95:253–323. [Google Scholar]

- Winter M. 2014, December 26. Irish court ends life support for brain dead pregnant mom. USA Today [On-line]. Available: http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2014/12/26/pregnant-woman-life-support-ireland/20917791/ (accessed April 13, 2016). [Google Scholar]