Abstract

We aimed to evaluate the effect of chronic hypergravity in a mouse model of allergic asthma and rhinitis. Forty BALB/c mice were divided as: group A (n = 10, control) sensitized and challenged with saline, group B (n = 10, asthma) challenged by intraperitoneal and intranasal ovalbumin (OVA) to induce allergic asthma and rhinitis, and groups C (n = 10, asthma/rotatory control) and D (n = 10, asthma/hypergravity) exposed to 4 weeks of rotation with normogravity (1G) or hypergravity (5G) during induction of asthma/rhinitis. Group D showed significantly decreased eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes in their BAL fluid compared with groups B and C (p < 0.05). In real-time polymerase chain reaction using lung homogenate, the expression of IL-1β was significantly upregulated (p < 0.001) and IL-4 and IL-10 significantly downregulated (p < 0.05) in group D. Infiltration of inflammatory cells into lung parenchyma and turbinate, and the thickness of respiratory epithelium was significantly reduced in group D (p < 0.05). The expression of Bcl-2 and heme oxygenase-1 were significantly downregulated, Bax and extracellular dismutase significantly upregulated in Group D. Therefore, chronic hypergravity could have a hormetic effect for allergic asthma and rhinitis via regulation of genes involved in antioxidative and proapoptotic pathways. It is possible that we could use hypergravity machinery for treating allergic respiratory disorders.

Space physiology, which deals with physiologic changes in space, is an emerging field of research as the need for space exploration increases. For more successful performance of several missions in space, thorough understanding of the physiologic changes associated with spaceflight is quite mandatory. The environmental challenges when an organism is exposed to spaceflight include phychological stress, radiation, and abrupt change in inertial condition (such as hyper- or micro-gravity)1,2.

Due to economic burden and limited opportunity, it is extremely difficult to perform experiments in real space. Therefore, a number of ground-based models have been developed to simulate space environment. One of the most widely accepted model for simulating hypergravity is the centrifugal device. By using the centrifugal force due to the rotation, we could expose cultured cells or experimental animals to higher gravity than 1 G3,4,5,6.

The immune system is one of the most affected biological systems when exposed to space stimuli. In fact, immune dysfunction has been suggested as a major health problem during long-term space mission7. However, researches on the impact of hypergravity on the immune system is still limited. Some studies have evaluated changes in the mitogen-induced proliferation of lymphocytes, titers of several cytokines, and subpopulations of lymphocytes1,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16.

Generally, space stimuli are thought to be noxious and harmful. However, in certain circumstances, hypergravity could have a beneficial effect on the human body. Ling et al. suggested that when rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells were exposed to hypergravity and 5-azacytidine at the same time, their differentiation into cardiomyocytes was significantly improved4. Exposure to hypergravity could also upregulate expression of osteopontin in osteoblasts5, and enhance differentiation of neuronal cells6. However, to the best of our knowledge, studies on the effects on allergic immunity are scarce. Furthermore, according to our review of the literature, no study has been conducted on the effect of hypergravity on animals with allergic disorders. When we exposed mice with allergic asthma and rhinitis to chronic hypergravity (5 G, 4 weeks), we could observe significant improvement in their clinical course of allergic airway inflammation. To establish the physiologic mechanisms underlying this clinical improvement, we evaluated (1) serum total and ovalbumin (OVA)-specific IgE, (2) number of inflammatory cells in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, (3) expression of genes for IL-1β, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, and interferon (IFN)-γ in lung homogenate, and (4) histopathologic findings of lung and nasal cavity. We also performed real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Bcl-2, Bax, caspase-3, heme oxygenase (HO)-1 and extracellular superoxide dismutase (EC-SOD).

Results

Rotatory Stimulus and Chronic Hypergravity Caused a Significant Decrease of Serum Total IgE But Not OVA-specific IgE

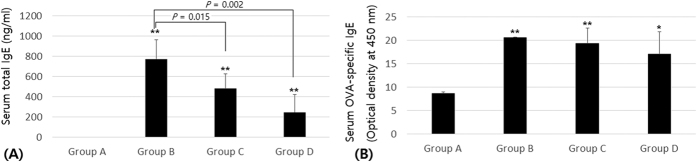

Compared with group A (control group), group B (asthma group) had a significantly elevated serum total IgE level (p < 0.01). After 4 weeks of continuous exposure to 1G or 5G gravity, the mice in group C (asthma/rotatory control group) and group D (asthma/hypergravity group) had significantly decreased serum total IgE levels (p < 0.05, Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Serum total IgE. Compared with group A, group B had significantly elevated serum total IgE. After 4 weeks of continuous exposure to 1G or 5G gravity, the mice in groups C and D had significantly decreased serum total IgE (p < 0.05). (B) Serum ovalbumin (OVA)-specific IgE. Compared with group A, groups B and C had significantly elevated OVA-specific IgE (p < 0.01). After 4 weeks of 5G hypergravity, group D had no significant decrease of OVA-specific IgE compared with groups B or C (p > 0.05). Group A is the control group, group B is the asthma group, group C is the asthma/rotatory control group, and group D is the asthma/hypergravity group. *Significant difference from group A, p < 0.05; **significant difference from group A, p < 0.01 (Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests).

Compared with group A, groups B and C had significantly elevated OVA-specific IgE levels (p < 0.01). After 4 weeks of continuous exposure to 5G hypergravity, group D had no significant decrease of OVA-specific IgE level compared with group B or C (p > 0.05, Fig. 1B).

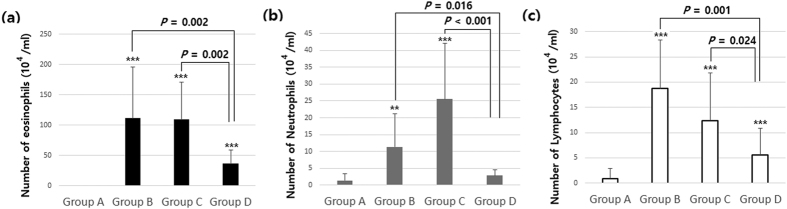

Decrease of Inflammatory Cells in BAL Fluid after Exposure to 4 Weeks of Hypergravity

Compared with group A, the number of inflammatory cells such as eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes in BAL fluid was significantly increased in groups B and C (p < 0.05). After exposure to 4 weeks of hypergravity, group D showed a significant decrease of all these inflammatory cells in BAL fluid compared with groups B and C (p < 0.05). Regarding neutrophils, especially, there was no significant difference between groups A and D (p > 0.05, Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The number of (a) eosinophils, (b) neutrophils, and (c) lymphocytes in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. Compared with group A, the number of eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes in BAL fluid was significantly increased in groups B and C (p < 0.05). After exposure to 4 weeks of hypergravity, group D showed significant decreases of all these inflammatory cells in BAL fluid compared with groups B and C (p < 0.05). Group A is the control group, group B is the asthma group, group C is the asthma/rotatory control group, and group D is the asthma/hypergravity group. **Significant difference from group A, p < 0.01; ***significant difference from group A, p < 0.001 (Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests).

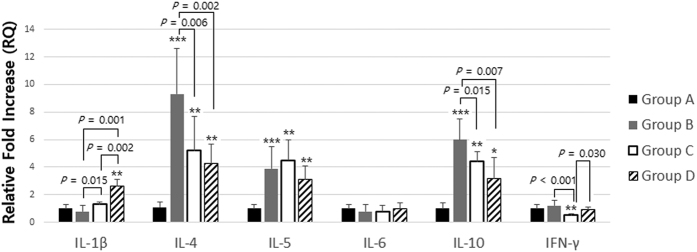

Chronic Hypergravity Caused upregulation of IL-1β and downregulation of IL-4 and IL-10 in Lung Homogenate

Performing real-time PCR analysis of lung homogenates, we found that group D had significant upregulation for IL-1β compared to groups B or C (p < 0.01). For IL-4 and IL-10, groups C and D had significant downregulation compared to group B after 4 weeks of rotatory normogravity or hypergravity stimuli (p < 0.05). Although the expression of IL-5 showed some tendency to decrease in group D, there was no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05). For IFN-γ expression, group C had significant downregulation (group B versus C, p < 0.001), which was recovered to normal level in group D (group C versus D, p = 0.030) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Gene expression for cytokines in lung homogenate.

Group D had significant upregulation for IL-1β compared with group B or C (p < 0.01). For IL-4 and IL-10, groups C and D had significant downregulation compared with group B after 4 weeks of rotatory normogravity stimulus or hypergravity (p < 0.05). Although the expression of IL-5 showed some tendency to be decreased in group D, there was no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05). For IFN-γ, group C had significant downregulation (group B versus C, p < 0.001), which was recovered to a normal level in group D (group C versus D, p = 0.030). Group A is the control group, group B is the asthma group, group C is the asthma/rotatory control group, and group D is the asthma/hypergravity group. *Significant difference from group A, p < 0.05; **significant difference from group A, p < 0.01; ***significant difference from group A, p < 0.001 (Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests). RQ, relative quantification.

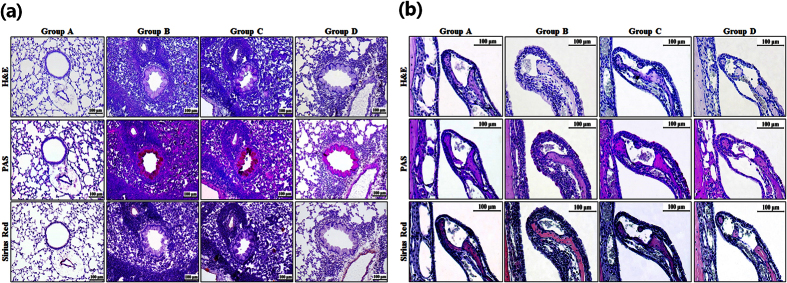

Histopathologic Change Related to Exposure to Long-Term Hypergravity

Compared with mice in group A, those in groups B and C had more infiltration of inflammatory cells into pulmonary parenchyma. After exposure to 4 weeks of 5G hypergravity, mice in group D had significantly less infiltration of inflammatory cells. Histopathologic examination of the nasal cavity also revealed a significantly less infiltration of inflammatory cells in the lamina propria in the turbinate in group D compared with groups B and C (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Histologic change of (a) lung and (b) nasal cavity after exposure to long-term hypergravity. Compared with group A, mice in groups B and C had more infiltration of inflammatory cells into pulmonary parenchyma. After exposure to hypergravity, mice in group D had significantly less infiltration of inflammatory cells. Histopathologic examination of the nasal cavity also revealed a significant tendency of less infiltration of inflammatory cells in the lamina propria in the turbinate in group D compared with groups B and C. Group A is the control group, group B is the asthma group, group C is the asthma/rotatory control group, and group D is the asthma/hypergravity group. The upper rows show hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, the middle rows show periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining, and the lower rows show Sirius Red staining at ×200 magnification for lung tissue and ×400 magnification for nasal cavity. Scale bar: 100 μm.

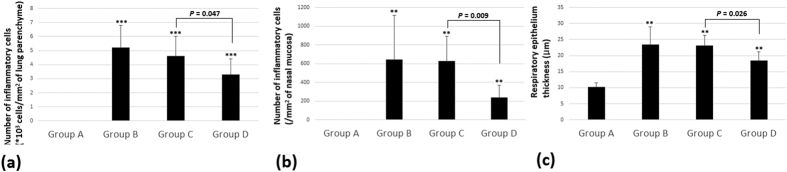

In quantitative analysis, mice in group D had a significantly decreased number of inflammatory cells that had infiltrated into pulmonary parenchyma and into the nasal mucosa compared with groups B and C. The thickness of the respiratory epithelium was also significantly decreased in group D after exposure to chronic hypergravity (p < 0.05, Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

The number of inflammatory cells in (a) 1 mm2 of lung parenchyma and (b) 1 mm2 of lamina propria of nasal mucosa. (c) The thickness of respiratory epithelium. Mice in group D had a significantly decreased number of inflammatory cells that had infiltrated into pulmonary parenchyma and into the nasal mucosa compared with groups B and C. The thickness of the respiratory epithelium was significantly decreased in group D after exposure to chronic hypergravity. Group A is the control group, group B is the asthma group, group C is the asthma/rotatory control group, and group D is the asthma/hypergravity group. **Significant difference from group A, p < 0.01; ***significant difference from group A, p < 0.001 (Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests).

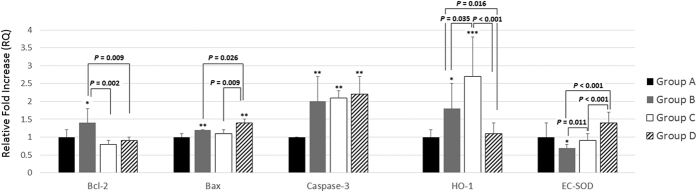

Change of Gene Expression Related to Apoptotic and Antioxidant Enzymes

Compared with group A, mice in group B had significantly upregulated gene expression for Bcl-2 (p < 0.05), Bax (p < 0.01), caspase-3 (p < 0.01), and HO-1 (p < 0.05) and significantly downregulated expression for EC-SOD (p < 0.05). After 4 weeks of hypergravity, group D had significant downregulation of Bcl-2 and significant upregulation of Bax compared with group B (p = 0.009 for Bcl-2; p = 0.026 for Bax). However, there was no significant difference in the expression of caspase-3 among groups B to D (p > 0.05).

After chronic exposure to hypergravity, mice in group D also showed significant suppression of HO-1. For EC-SOD, finally, mice in groups C and D showed significant recovery of EC-SOD compared with group B (group B versus C, p = 0.011; group C versus D, p < 0.001) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Gene expression related to apoptotic and antioxidant enzymes.

Compared with group A, the mice in group B had significantly upregulated gene expression for Bcl-2 (p < 0.05), Bax (p < 0.01), caspase-3 (p < 0.01), and HO-1 (p < 0.05) and significantly downregulated expression for EC-SOD (p < 0.05). After 4 weeks of hypergravity, group D had significant downregulation of Bcl-2 and significant upregulation of Bax compared with group B (p = 0.009 for Bcl-2; p = 0.026 for Bax). However, there was no significant difference in the expression of caspase-3 among groups B to D (p > 0.05). Group D also showed significant suppression of HO-1. For EC-SOD, mice in groups C and D showed significant recovery of EC-SOD compared with group B (group B versus C, p = 0.011; group C versus D, p < 0.001). Group A is the control group, group B is the asthma group, group C is the asthma/rotatory control group, and group D is the asthma/hypergravity group. *Significant difference from group A, p < 0.05; **significant difference from group A, p < 0.01 (Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests). RQ, relative quantification.

Discussion

There have been reports about the hormetic effects of chronic hypergravity in living organisms3,4,5,6. Minois suggested that when D. melanogaster was exposed to 2 weeks of hypergravity (3 to 5G), it lived longer (in other words, hormetic effects on its longevity)17. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate the hormetic immune effect in animals with allergic disorder.

Only few studies have been conducted on the effect of hypergravity on the humoral immune system. Guéguinou and colleagues evaluated changes in serum IgG, IgA, and IgM after chronic exposure to 3 weeks of hypergravity up to 3G18. In our study, group C (asthma/rotatory control) and group D (asthma/hypergravity group) showed significant decreases of serum total IgE compared with group B (asthma/stationary control). As group C showed a significant decrease of serum total IgE with just rotatory stimulus (but without hypergravity), the decrease in IgE might be the result of a stress response to rotatory stimuli. Although no results showed a change in Ig levels after rotatory stimulus, Guéguinou and colleagues reported that serum titers of IgG were significantly increased after chronic exposure to 2G of hypergravity18. The serum titers of OVA-specific IgE in group D showed no significant difference from those in groups B and C. These results are in accordance with previous research. Voss and colleagues suggested that normal individuals showed no significant change in their humoral immunity after short-term spaceflight19. However, no studies have investigated the effect of chronic hypergravity in animals with allergic disorders. In our previous study, mice with allergic asthma showed no significant change in serum OVA-specific IgE after exposure to short-term hypergravity (10G for 4 hours)20. Therefore, we could suggest that changes in the allergic response in animals with allergic disorders may be unrelated to IgE-related mechanisms.

According to a previous study, the number of neutrophils and lymphocytes in serum was significantly reduced after exposure to 3 weeks of hypergravity up to 3G21. However, no study has evaluated the change of inflammatory cells in BAL fluid. In our study, the number of all inflammatory cells including eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes was significantly decreased after long-term exposure to hypergravity as shown in group D. We decided to identify the physiologic mechanism underlying this hormetic immune response in experimental animals.

After exposure to short-term hypergravity, serum titers of IL-1β showed no significant change20. On the other hand, Liu and colleagues reported that IL-1β titers in rat brain were significantly increased after short-term exposure to hypergravity of 14G22. In this study, the expression of IL-1β in lung homogenate was significantly increased, but that of IL-4 and IL-10 was significantly decreased after exposure to chronic hypergravity in allergic mice. Although not statistically significant, the expression of IL-5 also showed some tendency to decrease in group D. Therefore, we could postulate that the shift from a Th2 to a Th1 response (increased Th1 cytokines and decreased Th2 cytokines) could be partly responsible for the reduced allergic immune response. Regarding IFN-γ, Pecaut and colleagues suggested that the serum concentration was significantly decreased during a 3-week period of 3G hypergravity3. However, as they used stationary control animals (mice housed in stationary cages), the effect of rotatory stress could not be ruled out. In our study, group C showed significant down-regulation of IFN-γ after normogravity rotation. After long-term exposure to hypergravity, the expression of IFN-γ was restored to a normal level. As biological activity of IFN-γ is also related to promotion of Th1 differentiation and suppression of Th2 differentiation, the increase of IFN-γ after exposure to hypergravity could also be responsible for the shift from a Th2 to a Th1 response.

To confirm the effect of chronic hypergravity on the allergic inflammatory response in the lung and the nasal cavity, we performed a histopathologic examination. As there was a significant decrease in the number of inflammatory cells that had infiltrated into lung parenchyma and nasal mucosa, we could confirm histologically that chronic hypergravity could alleviate allergic asthma and rhinitis.

The mechanism of hormetic effect of chronic hypergravity still remains largely unveiled17. One of the hypotheses is that protection and repair mechanisms against the stress could be involved17. Because of increased metabolic rate due to increased weight, there could be more oxidative damage as a result. Therefore, activities of several anti-oxidant enzymes could be upregulated to protect an organism against this oxidative damage17. In order to investigate this hypothesis in our model of allergic inflammation, we evaluated the expression of several genes related with anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic function.

The Bcl-2 family comprises proteins involved in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Among them, Bcl-2 is an antiapoptotic factor, and Bax is one of the proapoptotic factors. In our study, the expression of Bcl-2 was significantly suppressed and that of Bax was significantly enhanced after exposure to chronic hypergravity. Suppression of antiapoptotic enzymes and enhancement of proapoptotic enzymes could be responsible for increased apoptosis (and decreased number) of inflammatory cells in the lung parenchyma and nasal cavity. A decrease of inflammatory cells, in turn, could be responsible for the decreased Th2 cytokines. Our results and suggestions are in agreement with those of previous studies. Lin and colleagues suggested that IL-21 treatment caused reduced allergic symptoms, increased apoptosis of Th2 lymphocytes, and a significant decrease of the antiapoptotic factor Bcl-2 in allergic mice23. Zhao and colleagues reported that the expression of Bcl-2 was significantly increased in patients with allergic rhinitis. They stated that the expression of Bcl-2 was increased in CD4+ T lymphocytes and endothelial and epithelial cells24. On the other hand, the expression of Bax and caspase-3 mRNA was significantly increased in allergic mice25. Therefore, a protective effect of chronic hypergravity against allergic inflammation could be related to the downregulation of antiapoptotic signals (Bcl-2) and upregulation of proapoptotic signals (Bax) in inflammatory cells such as eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes.

HO-1, a specific regulator of endogenous carbon monoxide, suppresses degranulation of mast cells and synthesis of Th2 cytokines. Therefore, it has a protective effect against allergic airway inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness and hypersecretion of mucus26. Yu and colleagues suggested that OVA-sensitized guinea pigs showed significantly enhanced expression of the HO-1 gene, which was significantly suppressed after dexamethasone treatment27. Kuribayashi and colleagues also suggested that suppression of HO-1 activity by zinc protoporphyrin (a competitive HO-1 inhibitor) resulted in inhibition of airway hyperresponsiveness and pulmonary eosinophilia28. Therefore, suppression of HO-1 could be a promising potential target for antiallergic treatment26,29,30. In our study, it is probable that the suppression of HO-1 in group D could be responsible for the antiallergic effect of chronic hypergravity.

EC-SOD is one of the most important enzymes, exerting its antioxidant activity by removing oxygen free radicals such as superoxide in the lung. In our study, expression of EC-SOD was significantly downregulated in allergic mice. Our results are in agreement with those of previous studies. Ono and colleagues suggested that SOD activity was significantly reduced in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis31. Kwon and colleagues also suggested that administration of EC-SOD alleviated the Th2 response in mice with allergic asthma. Also, EC-SOD knockout mice showed severer asthma32. Therefore, recovery of EC-SOD activity could be another possible pathway for the antiallergic effect of chronic hypergravity.

Someone could argue that 5G of hypergravity is so severe that this result could not be directly interpolated to human. However, we should keep in mind that sensitivity to gravitational force is so different from species to species. According to Lee et al., 9G of hypergravity stimuli to mice equals 6.5 G to rats, and approximately matches to 2.7 G to humans33. According to them, 5 G of hypergravity used for this study would be equal to 1.3 to 1.4 G to human. As we need only modest speed of rotation and centrifugal force to induce 1.3 to 1.4 G of hypergravity, it would not cause much discomfort for the patient. Therefore, ‘hypergravity machinery’ for the new treatment strategy of allergic disorders would be relevant. Surely, we need to perform clinical study for human using bigger rotatory machinery to prove this possibility.

The importance of this study is that chronic hypergravity could have a positive effect on allergic asthma through activation of several genes involved in proapoptotic and antioxidant pathway. This is, to our best of knowledge, quite new finding and adds to our better understanding of the pathophysiology of allergic asthma34. Also, it is quite meaningful that hypergravity could possibly be considered as an additional, non-pharmacologic treatment in the management of allergic respiratory disorders.

Because of the small number of mice in each group, we had no choice but to perform nonparametric statistical analysis. Considering the large standard deviations for the results, it is necessary for us to perform further study with a larger population. Further study is also required to confirm the protein synthesis for all genes using Western blot analysis.

In conclusion, chronic hypergravity could have a beneficial effect in a mouse model of allergic asthma and rhinitis through regulation of genes involved in antioxidative and proapoptotic pathways.

Methods

Animals

Forty female BALB/c mice, 4 weeks old and free of murine-specific pathogens, were purchased from Orient Bio (Seongnam, Korea). They were raised in a controlled environment, with a regular 12-hour light/dark cycle and unrestricted access to OVA-free food and water. All mice used in this study were handled according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (INHA 150309-351-2).

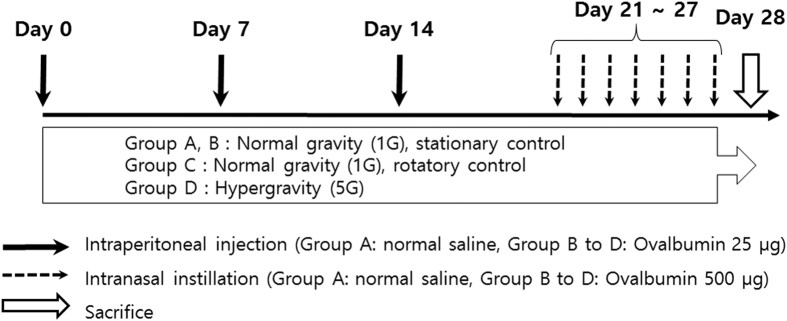

Sensitization and Challenge

For induction of allergic asthma and rhinitis, mice were first sensitized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 25 μg OVA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 1 mg aluminum hydroxide gel in sterile saline on days 0, 7, and 14. After systemic sensitization, mice were locally challenged by intranasal (i.n.) instillation with 500 μg OVA into their nostrils from days 21 to 27.

Exposure to Hypergravity

We developed a gravitational force (G-force) simulator for hypergravity experiments, which has two rotatory arms (50 cm long). When the arms are rotated, an outward centrifugal force is exerted on the animal cage, which is suspended from the arms. When the arms rotate at a speed of 65 rpm, mice in the cage are exposed to 5G hypergravity. With a high-resolution video camera inside the cage, we could evaluate whether the mice could move freely and get access to food and water. In this experiment, mice were exposed to simulated hypergravity for 28 consecutive days, during the whole sensitization and challenge period. During this 28-day period, we stopped the G-force simulator once a day (for approximately 30 minutes), checked the vitality of the animals, facilitated food and water intake, and performed the i.p. sensitization or i.n. challenge.

Mice in group A (n = 10, control group) received the i.p. and i.n. challenge with sterile saline only. Mice in group B (n = 10, asthma group) received the i.p. sensitization and i.n. challenge with OVA for induction of allergic asthma and rhinitis. Mice in groups A and B were bred without being exposed to any rotatory stimulus (stationary control). In group C (n = 10, asthma/rotatory control group), mice were exposed to a rotatory stimulus for 4 consecutive weeks as well as i.p. sensitization and i.n. challenge with OVA. However, with the centrifugal force so weak (lower rotational speed), animals in group C were exposed to normal gravity (1G, rotatory control). Finally, in group D (n = 10, asthma/hypergravity group), mice were exposed to continuous hypergravity of 5G for 28 days along with induction of allergic asthma and rhinitis (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Study protocol for induction of asthma/rhinitis and exposure to gravity stimuli.

Collecting Serum and Measuring Serum Total and OVA-specific IgE

Twenty-four hours after the last i.n. saline or OVA instillation, the G-force simulator was stopped and mice were immediately killed. We collected serum from the abdominal aorta using an aortic puncture technique. Whole blood was centrifuged at 4 °C for 30 minutes at 13,000 × g, and the supernatant was stored immediately at −80 °C. For analysis, the samples were diluted 1:100.

Serum levels of total IgE were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Total IgE was measured and compared with a mouse IgE standard (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA). Serum titers for OVA-specific IgE were determined using an ELISA kit (BD Pharmingen). We used the plate-coated IgE-capture antibody with OVA 50 μg/mL, and analyzed the optical density at 450 nm in accordance with the protocol provided by manufacturer.

Harvesting BAL Fluid and Differential Cell Counts in BAL Fluid

To harvest BAL fluid, we first cannulated the trachea using polyethylene tubing and then used a pulmonary lavage technique with sterile saline (approximately 3 mL). To determine the viability of cells and the total cell count, we used the trypan blue exclusion assay. Total cell numbers were determined in duplicates with a hemocytometer. Subsequently, a 100- to 200-μL aliquot was centrifuged in a Model 2 Cytospin cytocentrifuge (Shandon Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Differential cell counts for eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes were determined from centrifuged preparations stained with the Diff-Quik stain kit (Sysmex Corp., Kobe, Japan) by counting 500 or more cells from each sample at a magnification of ×200 (oil immersion).

Histopathologic examination

Tissue specimens of lung and nasal cavity were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 24 hours. Lung tissues were washed with deionized water and then embedded in paraffin. Nasal tissues were also washed with deionized water and then immersed in EDTA solution for decalcification for 3 to 4 weeks. They were then embedded in paraffin in the same way. Tissue sections (3 μm thickness) were stained using hematoxylin and eosin solution (for qualitative evaluation of histopathologic change), periodic acid–Schiff solution (for mucus) and Sirius Red staining (for evaluation of eosinophilic infiltration). The number of eosinophils infiltrated into 1 mm2 of pulmonary parenchyma was counted in 20 random high-power fields (×200 magnification). The number of eosinophils infiltrated into 1 mm2 of lamina propria was counted for each sample in the T1 area (section immediately caudal to the upper incisor teeth) in 10 high-power fields (×400 magnification). The thickness of the respiratory epithelium was calculated using ImageJ software, calculating the number of pixels for the respiratory epithelial cells and dividing it by the total number of pixels in the entire lung field. Two impartial, blinded researchers performed the histopathologic examinations and counted the eosinophils in tissue specimens.

Quantitative Real-time PCR

Whole-lung tissue from each mouse was frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after harvest and homogenized in 1 mL TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Waltham, MA, USA). They were then stored at −20 °C until further analysis. Total RNA was isolated as recommended protocol by the manufacturer. Before complementary DNA synthesis, quantity of extracted total RNA was analyzed by NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The integrity of the RNA was confirmed by electrophoresis.

After quantification of total RNA to 1 μg in each lung homogenate sample, we performed reverse transcription using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). Real-time PCR analysis was performed in duplicate using SYBR Green Master Mix ABI Prism in a PCR machine (7500 Real-Time PCR System; Applied Biosystems Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Primer annealing temperatures and number of cycling were as follows: 95 °C for 10 minutes, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 1 minute. We identified the highlight Sequence Features of the target gene from the NCBI site and primers were designed using Primer 3.0 software (primer sequences are shown in Table 1, except for IL-5 and IL-10). Primers for IL-5 and IL-10 were purchased from QuantiTect Primer Assays (QIAGEN, Venlo, The Netherlands). To calculate the efficiency of amplification, the relative quantity of each target gene was normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH.

Table 1. Primer Sequences for Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction.

| Gene | Primer Sequence | |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | Forward | 5′-CTC GGC CAA GAC AGG TCG CTC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CCC CCA CAC GTT GAC AGC TAG G-3′ | |

| IL-4 | Forward | 5′-GGT CTC AAC CCC CAG CTA GT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TGT GAG GAC GTT TGG CAC AT-3′ | |

| IL-6 | Forward | 5′-GCC TTC TTG GGA CTG ATG CTG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GGA CTC TGG CTT TGT CTT TCT TGT-3′ | |

| IFN-γ | Forward | 5′-AGG AAC TGG CAA AAG GAT GGT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTT GCT GAT GGC CTG ATT GT-3′ | |

| Bcl-2 | Forward | 5′-GGA CTT GAA GTG CCA TTG GT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AGC CCC TCT GTG ACA GCT TA-3′ | |

| Bax | Forward | 5′-GGA TGC GTC CAC CAA GAA GC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GGA GGA AGT CCA GTG TCC AGC C-3′ | |

| Caspase-3 | Forward | 5′-TGG GCC TGA AAT ACC AAG TC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-AAA TGA CCC CTT CAT CAC CA-3′ | |

| HO-1 | Forward | 5′-CCT CAC TGG CAG GAA ATC ATC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CCT CGT GGA GAC GCT TTA CAT A-3′ | |

| EC-SOD | Forward | 5′-GTG TCC CAA GAC AAT C-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GTG CTA TGG GGA CAG G-3′ | |

| GAPDH | Forward | 5′-GCA CAG TCA AGG CCG AGA AT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-GCC TTC TCC ATG GTG GTG AA-3′ | |

Statistical Analysis

We used nonparametric tests such as the Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney U test to compare the titers of total and OVA-specific IgE, the number of inflammatory cells in BAL fluid, the number of infiltrated eosinophils in pulmonary parenchyma and nasal cavity, and the degree of gene expression between groups. We considered a p value < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Jang, T. Y. et al. Hormetic Effect of Chronic Hypergravity in a Mouse Model of Allergic Asthma and Rhinitis. Sci. Rep. 6, 27260; doi: 10.1038/srep27260 (2016).

Acknowledgments

Tae Young Jang received a research grant (NRF-2013M1A3A3A02042309) from the Space Core Technology Development Program of the NRF funded by the Korean MSIP.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions T.Y.J. wrote main manuscripts, performed the statistical analysis, English interpretation and correction of the script. A.-Y.J. performed the main animal experiment and gained the preliminary data, performed the statistical analysis and the production of image. Y.H.K. designed the whole study and is responsible for the study.

References

- Pecaut M. J., Simske S. J. & Fleshner M. Spaceflight induces changes in splenocyte subpopulations: effectiveness of ground-based models. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 279, R2072–2078 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd P., Pecaut M. J. & Fleshner M. Combined effects of space flight factors and radiation on humans. Mutat. Res. 430, 211–219 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecaut M. J., Miller G. M., Nelson G. A. & Gridley D. S. Hypergravity-induced immunomodulation in a rodent model: hematological and lymphocyte function analyses. J. Appl. Physiol. 97, 29–38 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling S.-K. et al. Pretreatment of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells with a combination of hypergravity and 5-azacytidine enhances therapeutic efficacy for myocardial infarction. Biotechnol. Prog. 27, 473–482 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S., Zu Y., Sun Z., Zhuang F. & Yang C. Effects of Hypergravity on Osteopontin Expression in Osteoblasts. PloS One 10, e0128846 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genchi G. G. et al. Hypergravity stimulation enhances PC12 neuron-like cell differentiation. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 748121 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueguinou N. et al. Could spaceflight-associated immune system weakening preclude the expansion of human presence beyond Earth’s orbit? J. Leukoc. Biol. 86, 1027–1038 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allebban Z. et al. Effects of spaceflight on the number of rat peripheral blood leukocytes and lymphocyte subsets. J. Leukoc. Biol. 55, 209–213 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapes S. K., Simske S. J., Sonnenfeld G., Miller E. S. & Zimmerman R. J. Effects of spaceflight and PEG-IL-2 on rat physiological and immunological responses. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md. 1985, 86, 2065–2076 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecaut M. J. et al. Genetic models in applied physiology: selected contribution: effects of spaceflight on immunity in the C57BL/6 mouse. I. Immune population distributions. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md. 1985, 94, 2085–2094 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley D. S. et al. Genetic models in applied physiology: selected contribution: effects of spaceflight on immunity in the C57BL/6 mouse. II. Activation, cytokines, erythrocytes, and platelets. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md. 1985, 94, 2095–2103 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiki A. T. et al. Effects of spaceflight on rat peripheral blood leukocytes and bone marrow progenitor cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 60, 37–43 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesnyak A. et al. Effect of SLS-2 spaceflight on immunologic parameters of rats. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md. 1985, 81, 178–182 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E. S., Koebel D. A. & Sonnenfeld G. Influence of spaceflight on the production of interleukin-3 and interleukin-6 by rat spleen and thymus cells. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md. 1985, 78, 810–813 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenfeld G. Immune responses in space flight. Int. J. Sports Med. 19 Suppl 3, S195-202-204 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenfeld G. et al. Spaceflight and development of immune responses. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md. 1985, 85, 1429–1433 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minois N. The hormetic effects of hypergravity on longevity and aging. Dose-Response Publ. Int. Hormesis Soc. 4, 145–154 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guéguinou N. et al. Stress response and humoral immune system alterations related to chronic hypergravity in mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37, 137–147 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss E. W. Prolonged weightlessness and humoral immunity. Science 225, 214–215 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang T. Y. et al. Exposure to hypergravity increases serum interleukin-5 and pulmonary infiltration in mice with allergic asthma. Cent.-Eur. J. Immunol. Pol. Soc. Immunol. Elev. Cent.-Eur. Immunol. Soc. 39, 434–440 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley D. S., Pecaut M. J., Green L. M., Miller G. M. & Nelson G. A. Hypergravity-induced immunomodulation in a rodent model: lymphocytes and lymphoid organs. J. Gravitational Physiol. J. Int. Soc. Gravitational Physiol. 9, 15–27 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. J. et al. [Changes of mRNA expression of IL-1beta and TNF-alpha in rat brains after repeated exposures to +Gz]. Hang Tian Yi Xue Yu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Space Med. Med. Eng. 13, 371–373 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P.-Y., Jen H.-Y., Chiang B.-L., Sheu F. & Chuang Y.-H. Interleukin-21 suppresses the differentiation and functions of T helper 2 cells. Immunology 144, 668–676 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Li W., Wang Y. & Chen X. [Expression of OX40 and Bcl-2 in allergic rhinitis]. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi J. Clin. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 22, 1057–1059 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem A. et al. Proteinase activated receptor-2-mediated dual oxidase-2 up-regulation is involved in enhanced airway reactivity and inflammation in a mouse model of allergic asthma. Immunology 145, 391–403 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pae H.-O., Lee Y. C. & Chung H.-T. Heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide: emerging therapeutic targets in inflammation and allergy. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov. 2, 159–165 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S., Zhang R., Liu G., Yan Z. & Wu W. Expression of heme oxygenase-1 in nasal mucosa of allergic rhinitis guinea pig. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi 19, 504–506 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuribayashi K. et al. Suppression of heme oxygenase-1 activity reduces airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in a mouse model of asthma. J. Asthma Off. J. Assoc. Care Asthma 52, 662–668 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.-Y. et al. Anti-asthmatic effects of Angelica dahurica against ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation via upregulation of heme oxygenase-1. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 49, 829–837 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhang L., Wu J., Di C. & Xia Z. Heme oxygenase-1 exerts a protective role in ovalbumin-induced neutrophilic airway inflammation by inhibiting Th17 cell-mediated immune response. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 34612–34626 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono N. et al. Reduction in superoxide dismutase expression in the epithelial mucosa of eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 162, 173–180 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M.-J., Jeon Y.-J., Lee K.-Y. & Kim T.-Y. Superoxide dismutase 3 controls adaptive immune responses and contributes to the inhibition of ovalbumin-induced allergic airway inflammation in mice. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 17, 1376–1392 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. G. et al. A load of mice to hypergravity causes AMPKα repression with liver injury, which is overcome by preconditioning loads via Nrf2. Sci. Rep. 5, 15643 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang T. Y. & Kim Y. H. Interleukin-33 and Mast Cells Bridge Innate and Adaptive Immunity: From the Allergologist’s Perspective. Int. Neurourol. J. 19, 142–150 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]