Abstract

In the study, we evaluated chemical composition and antimicrobial, antibiofilm, and antitumor activities of essential oils from dried leaf essential oil of leaf and flower of Agastache rugosa for the first time. Essential oil of leaf and flower was evaluated with GC and GC–MS methods, and the essential oil of flower revealed the presence of 21 components, whose major compounds were pulegone (34.1%), estragole (29.5%), and p-Menthan-3-one (19.2%). 26 components from essential oil of leaf were identified, the major compounds were p-Menthan-3-one (48.8%) and estragole (20.8%). At the same time, essential oil of leaf, there is a very effective antimicrobial activity with MIC ranging from 9.4 to 42 μg ml−1 and potential antibiofilm, antitumor activities for essential oils of flower and leaf essential oil of leaf. The study highlighted the diversity in two different parts of A. rugosa grown in Xinjiang region and other places, which have different active constituents. Our results showed that this native plant may be a good candidate for further biological and pharmacological investigations.

Keywords: Essential oil, Agastache rugosa, GC–MS, Biological, Pharmacological, China

1. Introduction

Agastache rugosa is an edible plant, which belongs to Lamiaceae family and widely grows in China. The cultivated plant is used as a treatment for people suffering from anxiety, nausea, and bacterial infections. The herb is known under many different names, such as Korean Mint, purple giant hyssop, Indiana mint, and the wrinkled giant hyssop (Hudaberdi and Pan, 2004). As one of the 50 fundamental herbs, A. rugosa is known as huò xiāng, which is reported to have antifungal, antibacterial, carminative, and antipyretic properties (Liu, 1993). As an antifungal agents, this plant is used against Trichophyton species (Shin, 2004, Shin, 2004). It is reported that A. rugosa have antioxidant activity (Oha et al., 2006), antimicrobial activity (Kim, 2008) and anti-HIV integrase action (Kim et al., 1999). Essential oils are natural compounds with their components gaining increasing interest because of their relatively safe status, their wide acceptance by consumers and their exploration for potential functional use (Ormancey et al., 2001, Sawamura, 2000, Gianni et al., 2005). Actually, the essential oil shows a great promise as a new prototype from which antifungal agents may be developed (Yoon et al., 1994, Bidlack et al., 2000, Faleiro et al., 2003, Shin and Kang, 2003). In a previous report, the main component of the essential oil of A. rugosa is estragole (Shin and Kang, 2003), which has antifungal activity (Shin, 2004, Shin, 2004). In order to develop native herbal medicine resource and realize complementary and alternative for advantage resources, our research group cultivated the A. rugosa in Xinjiang for the last two years. However, to the best of our knowledge, the constituents of essential oils isolated from the dried flower and leaf of A. rugosa which grows in Xinjiang region, and its activity have never been evaluated and studied. As we known, the multi-drug resistance bacteria and biofilm development are ubiquitous phenomena with several deleterious medical and economic consequences. The ability to form biofilms is the important factor in pathogenesis of most microorganisms. Thus, the present study was to search for new antimicrobials agents, especially from native herbal plants. In this study, we aim to evaluate essential oil constituents of A. rugosa, which have many pharmacological activities and been cultivated in Xinjiang of China and to investigate the antimicrobial, antibiofilm and cytotoxic activities of essential oil of leaf and flower from A. rugosa. The current investigation was to find whether there is diversity in two different parts of A. rugosa grown in Xinjiang and other places. At the same time, we initiated this study to find an efficiency and low toxicity natural medicines, which will apply to treatment of human diseases, lower resistance rates and benefit of mankind, for further research.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Plant material

The aerial part of A. rugosa was collected in September 2010 from Liyu mountain in Urumqi city of Xinjiang, China, which was identified by Traditional Chinese Medicine Ethnical Herbs Specimen Museum, Yonghe Li. A voucher specimen (No. TCMEHSM 2010-352) was deposited in the museum of this institute.

2.2. Essential oil isolation

The flower and leaf of examined plants were separated and dried in shadow at room temperature, and submitted 100 g to hydrodistillation with 1 L of distilled water in a Clevenger-type apparatus for 6 h. At the end of each distillation the oils were collected, dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate prior to analyses, measured, transferred to glass flasks and stored at 4 °C until the moment of analysis.

2.3. Gas chromatography and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry

GC was carried out using a Agilent 6890 N GC-FID system, equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) on a Agilent capillary column, HP-5 (30 m × 0.32 mm; film thickness 0.25 μm). The column temperature was programed from 40 °C to 250 °C for 5 °C/min. The column temperatures of injector and detector were fixed to 250 °C. Helium was used as the carrier, flow rate 1.0 ml/min.

The GC–MS analysis was carried out using a Agilent 6890 N GC-FID system, equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) on a Agilent capillary column, HP-5 (30 m × 0.32 mm; film thickness 0.25 μm). The column temperature was programed from 40 °C to 250 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min. The column temperatures of injector and detector were 250 °C. Helium was used as the carrier, flow rate 1.0 ml/min. Split ratio was 1:100. The GC–MS analysis was done in the EI mode at 70 eV, inlet temperature was 200 °C and transfer line temperature was 250 °C. The temperature program was the same with that of the GC analysis. The injected volume was 0.2 μl.

2.4. Identification of components

The identification of components and peak was done by comparison of their retention time with respect to the n-alkane series (C6-C22) internal standards under the identical experimental conditions. The mass spectra and relative Retention Index (RI) were compared with those of commercial (NIST 05 and NIST 05 s). The relative amounts of individual components were calculated based on GC integrator peak areas without using correction factors.

2.5. Test organisms

Organisms contain Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923, positive control: Penicillin) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922, positive control: Gentamycin Sulfate Injection) were used for the study. The organisms were maintained by serial sub-culturing every month on nutrient agar slants and incubating at 37 °C for 18–24 h.

The cultures were stored under refrigerated condition. The antifungal activity of the oil was tested against Candida albicans (ATCC 10231, positive control: Fluconazole).

2.6. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs)

The inhibition effect of EOF and essential oil of leaf on bacterial growth was determined, with a broth microdilution susceptibility test, as recommended by CLSI (2014) and described in experiment technique of medical microbiology (Guan et al., 2006). The oils were added aseptically to sterile melted Mueller Hinton Broth medium to produce the concentration range of 5.25–336 μg/ml for EOF and range of 4.72–302 μg/ml for essential oil of leaf. The bacterial plates were incubated at 37 °C.

The antifungal activity of the oils against C. albicans was evaluated using the broth dilution method. The oils were added aseptically to sterile melted Sabouraud’s Broth medium to produce the concentration range of 5.25–336 μg/ml for EOF and range of 4.72–302 μg/ml for essential oil of leaf. MIC values were determined as the lowest concentration of the essential oils where the absence of growth was recorded. Each test in this study was repeated triplicate.

2.7. Antibiofilm activity assay

The oils were diluted with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) as the stock solution for antibiofilm activity. 10 μl of DMSO loaded on three sterile blank disks was placed on the agar plates and was then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. There was no antibacterial activity on the plates and so DMSO was selected as a safe diluting agent for the oil. Each oil dilution was followed by sterilization using a 0.22 μm membrane filter. The solvent served as control.

The assay was performed in 96 well microtiter plates, and to each well we added the bacterial suspension (5 × 106 CFU/ml, S. aureus, E. coli, C. albicans), the EOF and essential oil of leaf at concentrations less than MIC (10-fold dilution from 10−1 to 10−6). Then the microplates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h under aerobic condition. After this incubation period, the culture medium was removed and rinsed with sterile distilled deionized water (six rinses). Then, the biofilm was fixed with 150 μl of Methanol (PA) for 15 min, stained with crystal violet 0.1% (v/v) and rinsed with water. Biofilm formation was evaluated by adding 150 μl of 95% ethanol to the wells, and the plates were subjected to spectrophotometric reading at 620 nm. The results were expressed as percent inhibition of biofilm formation, considering the absorbance of the positive control (no potential antibacterial agent was added) as 0% inhibition. At least three replicate experiments were performed for each concentration of EOF and essential oil of leaf that was tested.

2.8. Cell viability assay (MTT)

To evaluate the MTT assay for the assessment of gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901 damage induced by essential oils from A. rugosa, we used 5-fluorouracil (5-F) as a positive control. A MTT colorimetric method based on the reduction in a tetrazolium salt was used according to the modification of Walenka et al. (2005), as follows: after incubation Gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901 suspensions were added in 96-well plates per 100 μl (3.44 × 107/well). Then four different concentrations samples (S1: essential oil of flower, S2: essential oil of leaf, S3: estragole, S4: pulegone) and 5-fluorouracil (5-F) were added in 96-well plates per 10 μl, respectively.

Incubating at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, then 10 μl of 5 mg/ml MTT (Sigma–Aldrich, Switzerland) was added in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, Gibco, Life Technologies, Switzerland). After incubating for 4 h, the medium was replaced with 200 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to stop the reaction and lyse the cells. Uninfected gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901 served as 0%-damage control and wells containing medium alone were used for background correction. Absorbance of 200 μl of the solution was measured at 560 nm. Damage was calculated using the following formula: 1−(A560 of test well/A560 of 0%-damage control well).

1 control and 4 experimental groups were run in triplicate for cellular viability analysis by the MTT assay. Each experiment was repeated 3 times.

2.9. Statistics

All experiments were performed in at least three repetitions. A comparative analysis of means was performed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple comparison test (P < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Chemical composition

The yields of EOF and essential oil of leaf of A. rugosa were 0.29–0.57% (w/w), respectively. The characteristic color of EOF was powerful spicy and presented light yellow color. The essential oil of leaf gave off stronger aromatic odor with brilliant yellow color. The oils were analyzed by using GC–MS of which the percentage compositions of the oils were listed in Table 1, where all constituents were arranged in such a way that their elution was on the DB-5 column.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the essential oil of the dried flowers and leaf from Agastache rugosa (Fisch. et Mey) from Xinjiang.

| Peak | Name | RI | Peak area (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||

| 1 | Octane | 800 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| 2 | Hexane, 2,2,3-trimethyl | 816 | t | t |

| 3 | Hexane, 2,3,4-trimethyl | 818 | t | – |

| 4 | 2-Hexenal, (E) | 850 | – | 0.1 |

| 5 | 3-Hexen-1-ol | 853 | – | t |

| 6 | Cyclohexanone | 895 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| 7 | Sabinen | 972 | t | 0.1 |

| 8 | 1-Octen-3-ol | 980 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| 9 | 3-Octanone | 984 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| 10 | β.-Myrcene | 989 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 11 | Limonene | 1030 | 8.2 | 7.7 |

| 12 | α.,p-Dimethylstyrene octen-1- | 1091 | – | t |

| 13 | ol, acetate | 1106 | 0.7 | 1.4 |

| 14 | trans-p-Mentha-2,8-dienol | 1124 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| 15 | 4-Isopropenyl-1-methyl-2- cyclohexen-1-ol | 1139 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| 16 | p-Menthan-3-one, cis p- | 1158 | 2.5 | 7.3 |

| 17 | Menthan-3-one | 1167 | 16.7 | 48.8 |

| 18 | p-Menth-8-en-3-one, trans | 1178 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| 19 | Estragole | 1200 | 29.5 | 20.8 |

| 20 | 6,6,7-Trimethyl-octane-2,5-dione | 1219 | – | 0.1 |

| 21 | cis-Carvessential oil of leaf | 1221 | – | t |

| 22 | Pulegone | 1241 | 34.1 | 0.4 |

| 23 | Piperitone | 1257 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| 24 | Benzyl isopentyl ether | 1289 | t | t |

| 25 | Tridecane | 1300 | – | 0.1 |

| 26 | (Z)-Cinerone | 1342 | 0.1 | – |

| 27 | Cyclobuta[1,2:3,4]dicyclopentene,decahydro-3a-methyl-6-methylene-1-(1-methylethyl)-,[1S-(1.α.,3a.α.,3b.β.,6a.β.,6b.α.)] | 1388 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 28 | Benzene, 1,2-dimethoxy-4-(2-propenyl) | 1400 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| 29 | Caryophyllene | 1425 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| 30 | Germacrene D | 1487 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| 31 | Gamma-elemene | 1501 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| 32 | Cadina-1(10),4-diene | 1523 | – | t |

| 33 | Spathulenol | 1585 | – | 0.2 |

| 34 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1591 | – | t |

| 35 | α.-Cadinol | 1663 | – | 0.2 |

RI = retention indices relative to C8-C17. N-alkanes on the HP-5 column. 1: flower, 2: leaf.

t = trace, GC Compositional values less than 0.1% are denoted as traces.

Legend: The identification of the components and peak was done by comparison of their retention time with respect to the n-alkane series (C6–C22) internal standards under identical experimental condition. The mass spectra and relative Retention Index (RI) were compared with those of commercial (NIST 05 and NIST 05s). The relative amounts of individual components were calculated based on GC integrator peak areas without using correction factors.

In this study, the EOF revealed the presence of 21 components, representing 99.78% of the total oil. The major compounds were oxygenated terpenes (35.4%), including pulegone (34.1%), estragole (29.5%), p-Menthan-3-one (19.2%), and monoterpenes (8.8%). The monoterpenes and aromatic compounds were main volatile fractions of the EOF. Meanwhile, 26 components accounting for 99.62% of constituents of essential oil of leaf were identified, and the main compounds of the oil were p-Menthan-3-one (48.8%), estragole (20.8%), monoterpenes (8.3%), and oxygenated terpenes (5.6%).

3.2. Antimicrobial activity

The in vitro antibacterial activities of EOF and essential oil of leaf from A. rugosa against the microorganisms were qualitatively and quantitatively assessed by the MIC values. The results were obtained and screening of antibacterial activity of essential oil of A. rugosa is summarized in Table 2. With the broth dilution method, the MIC values for EOF and essential oil of leaf were in the range of 21–42 μg/ml and 9.4–37.8 μg/ml, respectively. In Table 2, the essential oil of flower and leaf of A. rugosa was found to have moderate to high antimicrobial activity. It showed strong inhibition against S. aureus, E. coli for EOF; and strong inhibition against E. coli for essential oil of leaf. And it showed low activity against C. albicans for essential oil of flower and leaf. The results of MIC values indicated that E. coli was inhibited at lower concentrations by essential oil of leaf than S. aureus, in which the lowest MIC value is 9.4 μg/ml. The essential oil of leaf was sensitive than essential oil of flower in fungicidal activity. The antibacterial ability showed by the essential oil of leaf may be due to the chemical composition of the extract, which is rich in p-Menthan-3-one. When the oils were added to the culture medium, the growth rates of tested organisms were found to significantly decrease as compared to the control cultures. In some cases, the oils showed the same type of antimicrobial activity compared to penicillin, while the oils showed high activity in some other cases than the standard reference antibiotics.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial activity of essential oils from leaf and flower parts of Agastache rugosa.

| Organisms | MICa (minimum inhibitory concentration) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Leaf part | Flower part | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 37.8 | 21 |

| Escherichia coli | 9.4 | 21 |

| Blastomyces albicans | 37.8 | 42 |

Values given as μg ml−1.

3.3. Antibiofilm activity and cell viability assay

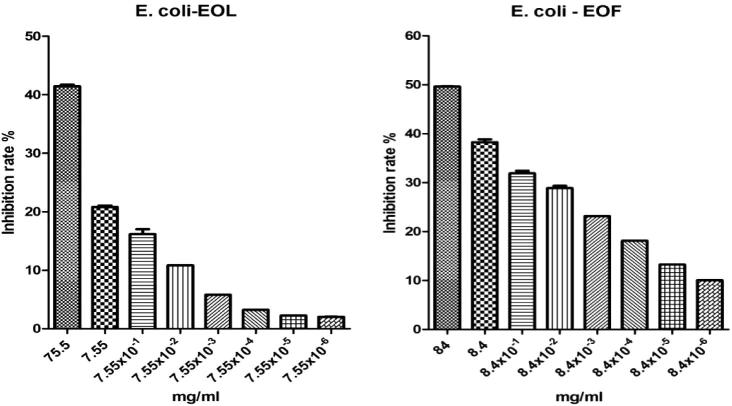

Studies describe the action of natural plant extracts as antibacterial agents, and able to inhibit many bacterial species, particularly Gram-negative microorganism (E. coli). However, in some cases, E. coli have high rate of resistance of antibiotics, particularly when they form biofilm. According to our recent survey, E. coli. occupied 21.54% of the ten common clinic bacteria in 2014 from a three levels of first-class hospital. Meanwhile, E. coli is capable of forming biofilm, which is one causes of drug-resistant, is increasingly recognized as an important virulence factor for E. coli (Oliveira et al., 2006). Thus, we further examined the antibiofilm activity of essential oils of EOF and essential oil of leaf. Both the essential oil of flower and leaf showed inhibited biofilms, and the inhibitory rate increased at the concentration of essential oil of flower and leaf from 8.4 × 10−6 to 84 mg/ml and 7.5 × 10−6 to 75.5 mg/ml, respectively (Fig. 1). The antimicrobial agent derived from natural products may represent a suitable alternative to limit this process.

Figure 1.

Percent inhibition of biofilm formation exhibition by essential oil of leaf and EOF of Agastache rugosa.

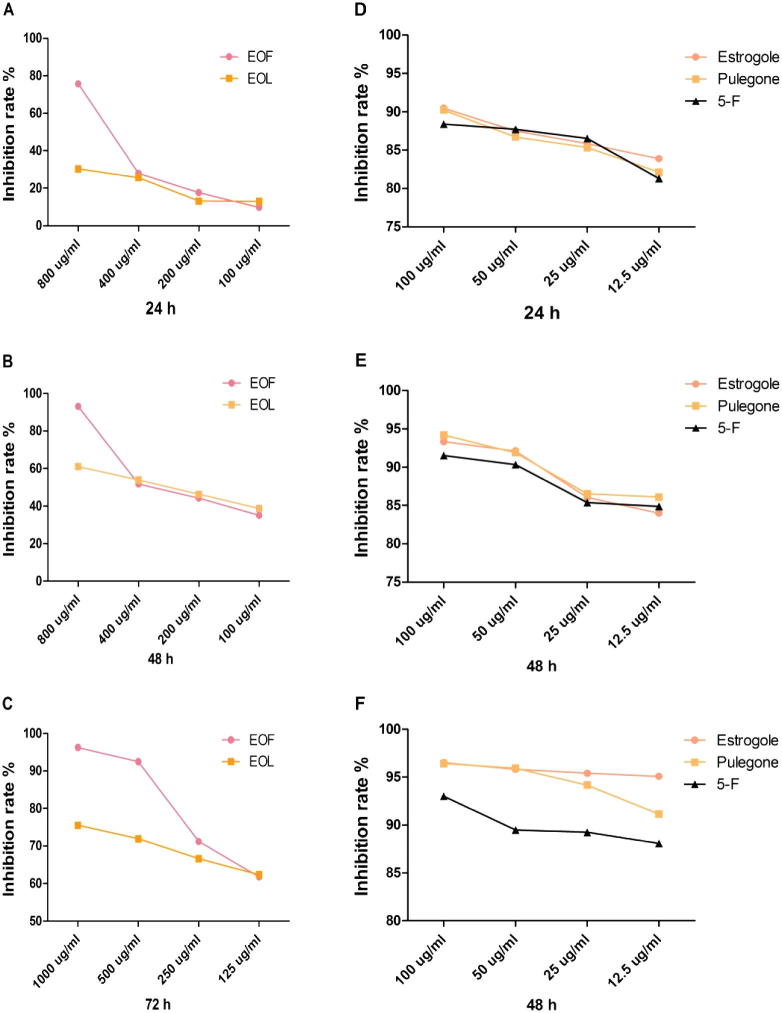

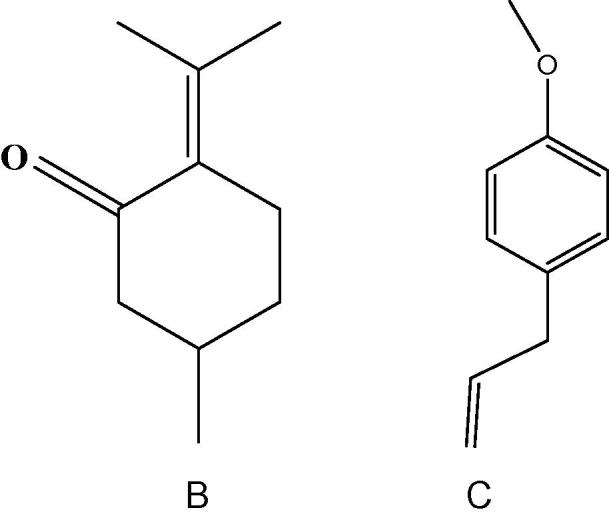

According to the assay of chemical composition and antibacterial activity in the study, the pulegone (CAS: 89-82-7, Fig.2A) and estragole (CAS: 140-67-0, Fig.2A) are applied as standard substances which were the main active compounds in the essential oil of flower and leaf of A. rugosa. The MTT assay showed a dose and time-dependent increase in damage induced by S1–S4 in gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901 (Fig. 3). Meanwhile, the EOF showed sensitive (inhibition rate >70%) to gastric cancer cell line SGC-7901 ranging from 250 to 1000 μg ml−1, from 500 to 1000 μg ml−1 for the essential oil of leaf, and from 12.5 to 100 μg ml−1 for estragole, pulegone and 5-fluorouracil (inhibition rate >85%).

Figure 2.

Chemical formula of Pulegone (A), Estragole (B).

Figure 3.

Inhibition rate of each group at different time (24 h, 48 h, 72 h), expressed in percentage. EOF and essential oil of leaf, estragole, pulegone and 5-fluorouracil indicate statistical differences (P < 0.05).

4. Discussions

In the present study, we investigated whether there is diversity between two different parts of A. rugosa. However, there was hardly similarity between oils from the essential oil of flower and leaf. In this study, oxygenated terpenes were the main compounds in the EOF; p-Menthan-3-one was the main compound in the essential oil of leaf. The oils have high contents of p-Menthan-3-one. Meanwhile, P-Menthan-3-one and estragole were detected as common main compounds (peak area >10%) of two essential oils.

Compared with Korean Mint (A. rugosa), there were significant differences for each other. As reported, methyl chavicol was the predominant component in the both leaf (84.25%) and flower (57.94%) of Korean Mint (A. rugosa) (Lim et al., 2013). Previous investigations were done on the chemical constituents of essential oil of A. rugosa from northeast China (Yue, 1998), Hubei (Yang et al., 2000) and Hunan (Xiong et al., 2009) of China, the Central Botanical Garden of the NAS of Belarus (Skakovskii et al., 2010). So far, constituents of essential oils isolated from the flower and leaf of A. rugosa cultivated in Xinjiang, have not been reported.

S. aureus and E. coli exist in upper respiratory, food, and large intestine, respectively. Blastomyces albicans exists in mucous membrane of oral cavity, upper respiratory, intestinal tract, vagina, etc. Herbal medicines may be an alternative because they present secondary metabolites that are active against a wide range of microorganisms. Based on the research, the essential oils derived from herbal plants, could be developed as an antimicrobial agent in medical field and food industry, and its mode of action is required for future drug development.

We initiated this study to characterize composition of the essential oils from different parts of A. rugosa that was artificial cultured and grown in Xinjiang, and offer choice for clinical treatments and application, which have not been the subject of previous studies. The essential oils from A. rugosa possess potential antimicrobial, antibiofilm and cytotoxic activities. So our results offer reliable base for resource optimization, clinical choice and standard of quality control.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant from China, the Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2013211A063).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Bidlack W.R., Omaye S.T., Meskin M.S., Topham D. Technomic Publishing Company; Lancaster: 2000. Phytochemicals as Bioactive Agents; pp. 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Faleiro M.L., Miguel M.G., Ladeiro F., Venâncio F., Tavares R., Brito J.C. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils isolated from Portuguese endemic species of Thymus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2003;36:35–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2003.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianni S., Maietti S., Muzzoli M., Scaglianti M., Manfredini S., Radice M. Comparative evaluation of 11 essential oils of different origin as functional antioxidants, antiradicals and antimicrobials in foods. Food Chem. 2005;91:621–632. [Google Scholar]

- Guan Z.Y., Wang A.L., Li J. Chemical Industry House; China: 2006. Experiment Technique of Medicalmicrobiology; pp. 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Hudaberdi M., Pan X.L. Xinjiang Science & Technology Publishing House Publ.; Xinjiang: 2004. Introduction of Agastache rugosa (Fisch. et Mey) of Xinjiang (4th of Flora Xinjiangensis) pp. 237–239. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. Phytotoxic and antimicrobial activities and chemical analysis of leaf essential oil from Agastache rugosa. J. Plant Biol. 2008;51(4):276–283. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.K., Lee H.K., Shin C.G., Huh H. HIV integrase inhibitory activity of Agastache rugosa. Arch. Pharm. Res. 1999;22:520–523. doi: 10.1007/BF02979163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S.S., Jang J.M., Park W.T. Chemical composition of essential oils from flower and leaf of Korean mint Agastache rugosa. Asian J. Chem. 2013;25(8):4361–4363. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.M. Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Health Department Edits; Health Science and Technology Publishing House Publ (K); Xinjiang: 1993. Uighur Medicine Standard, Upper Volume; pp. 387–388. [Google Scholar]

- Oha H.M., Kangb Y.J., Leea Y.S., Parka M.K., Kima S.H., Kima H.J. Protein kinase G-dependent heme oxygenase-1 induction by Agastache rugosa leaf extract protects RAW 264.7 cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced injury. Ethnopharmacol. 2006;103:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira M., Bexiga R., Nunes S.F., Carneiro C., Cavaco L.M., Bernardo F. Biofilm-forming ability profiling of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis mastitis isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 2006;118:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormancey X., Sisalli S., Coutiere P. Formulation of essential oils in functional perfumery. Parfums Cosmetiques Actualites. 2001;157:30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura M. Aroma and functional properties of Japanese yuzu (Citrus junos Tanaka) Essent. Oil Aroma. Res. 2000;1(1):14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Shin S. Essential oil compounds from Agastache rugosa as antifungal agents against Trichophyton species. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2004;27(3):295–299. doi: 10.1007/BF02980063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S. Essential oil compounds from Agastache rugosa as antifungal agents against Trichophyton species. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2004;27:295–297. doi: 10.1007/BF02980063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S., Kang C.A. Antifungal activity of the essential oil of Agastache rugosa Kuntze and its synergism with ketoconazole. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2003;36:111–115. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2003.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skakovskii E.D., Kiselev W.P., Tychinskaya L.Y. Characterization of the essential oil of Agastache rugosa by NMR Spectroscopy. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 2010;77(3):329–334. [Google Scholar]

- Walenka E., Sadowska B., Rozalska S. Lysostaphin as a potential therapeutic agent for staphylococcal biofilm eradication. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2005;54:191–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y.H., Hu K., Wang M. Analysis of essential oil in herbal pair Artemisia annua-Agastache rugosa by GC–MS and chemometric resolution method. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2009;44(11):1267–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D., Wang F., Su J. Chemical composition of essential oil in stems, leaves and flowers of Agastache rugosa. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2000;23(3):149–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S.Y., Eo S.K., Lee D.K., Han S.S. Antimicrobial activity of Ganoderma lucidum extract alone and in combination with some antibiotics. Arch. Pharmacol. Res. 1994;6:438–442. doi: 10.1007/BF02979122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J.L. Chemical constituents of essential oil of Agastache rugosa of Northeast China. J. Northeast For. Univ. 1998;26(1):11–18. [Google Scholar]