Abstract

Interval censoring arises frequently in clinical, epidemiological, financial and sociological studies, where the event or failure of interest is known only to occur within an interval induced by periodic monitoring. We formulate the effects of potentially time-dependent covariates on the interval-censored failure time through a broad class of semiparametric transformation models that encompasses proportional hazards and proportional odds models. We consider nonparametric maximum likelihood estimation for this class of models with an arbitrary number of monitoring times for each subject. We devise an EM-type algorithm that converges stably, even in the presence of time-dependent covariates, and show that the estimators for the regression parameters are consistent, asymptotically normal, and asymptotically efficient with an easily estimated covariance matrix. Finally, we demonstrate the performance of our procedures through simulation studies and application to an HIV/AIDS study conducted in Thailand.

Keywords: Current-status data, EM algorithm, Interval censoring, Linear transformation model, Nonparametric likelihood, Proportional hazards, Proportional odds, Semiparametric efficiency, Time-dependent covariate

1. Introduction

Interval-censored data arise when the event or failure of interest is known only to occur within a time interval. Such data are commonly encountered in disease research, where the ascertainment of an asymptomatic event is costly or invasive and so can take place only at a small number of monitoring times. For example, in HIV/AIDS studies, blood samples are periodically drawn from at-risk subjects to look for evidence of HIV sero-conversion. Likewise, biopsies are performed on patients at clinic visits to determine the occurrence or recurrence of cancer.

There are several types of interval-censored data. The simplest and most studied type is

called case-1 or current-status data, which involves only one monitoring time per subject

and is routinely found in cross-sectional studies. When there are two or

monitoring times per subject, the resulting data are

referred to as case-2 or case-

monitoring times per subject, the resulting data are

referred to as case-2 or case- interval censoring (Huang & Wellner, 1997). The most general and common type allows

for varying numbers of monitoring times among subjects and is termed mixed-case interval

censoring (Schick & Yu, 2000).

interval censoring (Huang & Wellner, 1997). The most general and common type allows

for varying numbers of monitoring times among subjects and is termed mixed-case interval

censoring (Schick & Yu, 2000).

The fact that the failure time is never observed exactly poses theoretical and

computational challenges in semiparametric regression analysis of such data. Huang (1995, 1996) and Huang & Wellner (1997)

studied nonparametric maximum likelihood estimation for the proportional hazards and

proportional odds models with case-1 and case-2 data. The estimators are obtained by the

iterative convex minorant algorithm, which becomes unstable for large datasets. Sieve

maximum likelihood estimation for the proportional odds model was considered by Rossini & Tsiatis (1996) with case-1 data and

by Huang & Rossini (1997) and Shen (1998) with case-2 data; however, it is

difficult to choose an appropriate sieve parameter space and, especially, to choose the

number of knots. For the proportional odds model with case-1 and case-2 data, Rabinowitz et al. (2000) derived an approximate

conditional likelihood, which does not perform well in small samples. Gu et al. (2005), Sun &

Sun (2005), Zhang et al. (2005) and

Zhang & Zhao (2013) constructed

rank-based estimators for linear transformation models, but such estimators are

computationally demanding and statistically inefficient. None of the existing work

accommodates time-dependent covariates or can handle case- or mixed-case interval

censoring.

or mixed-case interval

censoring.

In this paper we consider interval censoring in the most general form, that is, mixed-case data. We study nonparametric maximum likelihood estimation for a broad class of transformation models that allows time-dependent covariates and includes the proportional hazards and proportional odds models as special cases. We develop an EM-type algorithm, which is demonstrated to perform satisfactorily in a wide variety of settings, even with time-dependent covariates. Using empirical process theory (van der Vaart & Wellner, 1996; van de Geer, 2000) and semiparametric efficiency theory (Bickel et al., 1993), we establish that, under mild conditions, the proposed estimators for the regression parameters are consistent and asymptotically normal and the limiting covariance matrix attains the semiparametric efficiency bound and can be estimated analytically by the profile likelihood method (Murphy & van der Vaart, 2000). The theoretical development requires careful treatment of the time trajectories of covariate processes and the joint distribution for an arbitrary sequence of monitoring times.

2. Methods

2.1. Transformation models and likelihood construction

Let  denote the failure time, and let

denote the failure time, and let

denote a

denote a  -vector of potentially time-dependent

covariates. Under the semiparametric transformation model, the cumulative hazard function

for

-vector of potentially time-dependent

covariates. Under the semiparametric transformation model, the cumulative hazard function

for  conditional on

conditional on  takes the

form

takes the

form

|

(1) |

where

is a specific transformation function that is strictly

increasing and

is a specific transformation function that is strictly

increasing and  is an unknown increasing function (Zeng & Lin, 2006). The choices of

is an unknown increasing function (Zeng & Lin, 2006). The choices of

and

and  yield the proportional

hazards and proportional odds models, respectively. It is useful to consider the class of

frailty-induced transformations

yield the proportional

hazards and proportional odds models, respectively. It is useful to consider the class of

frailty-induced transformations

|

where  is the density function of a

frailty variable with support

is the density function of a

frailty variable with support  . The choice of the gamma density with unit

mean and variance

. The choice of the gamma density with unit

mean and variance  for

for  yields the class of logarithmic

transformations,

yields the class of logarithmic

transformations,

, and the

choice of the positive stable distribution with parameter

, and the

choice of the positive stable distribution with parameter  yields the

class of Box–Cox transformations,

yields the

class of Box–Cox transformations,  . When

all the covariates are time-independent, model (1) can be rewritten as a linear transformation model

. When

all the covariates are time-independent, model (1) can be rewritten as a linear transformation model

|

where  is an error

term with distribution function

is an error

term with distribution function  (Chen et al., 2002). Thus,

(Chen et al., 2002). Thus,

can be interpreted as the effects of covariates on a

transformation of

can be interpreted as the effects of covariates on a

transformation of  .

.

We formulate the mixed-case interval censoring by assuming that the number of monitoring

times, denoted by  , is random and that there exists a random sequence of

monitoring times, denoted by

, is random and that there exists a random sequence of

monitoring times, denoted by  . We do not model

. We do not model

. Write

. Write  , where

, where  and

and  .

Also, define

.

Also, define  , where

, where

with

with

denoting the indicator function. Then the observed data

from a random sample of

denoting the indicator function. Then the observed data

from a random sample of  subjects consist of

subjects consist of

, where

, where

and

and  . If

. If  or 2

or 2

, then the observation scheme becomes case-1 or

case-2, respectively.

, then the observation scheme becomes case-1 or

case-2, respectively.

Suppose that  is independent of

is independent of  conditional on

conditional on

. Then the observed-data likelihood function concerning

parameters

. Then the observed-data likelihood function concerning

parameters  takes the form

takes the form

|

Since only one  is unity

for each subject and the others equal zero,

is unity

for each subject and the others equal zero,

|

where  is the smallest interval

that brackets

is the smallest interval

that brackets  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  and

and

. Clearly,

. Clearly,  indicates that

the

indicates that

the  th subject is left censored, while

th subject is left censored, while

indicates that the subject is right censored.

indicates that the subject is right censored.

Remark 1. —

The sequence of monitoring times may not be completely observed and, in fact, need not be for the purpose of inference. We only need to know the values of

and

, since the other monitoring times do not contribute to the likelihood. The theoretical development, however, requires consideration of the joint distribution for the entire sequence of monitoring times.

2.2. Nonparametric maximum likelihood estimation

To estimate  and

and  , we adopt the nonparametric

maximum likelihood approach, under which

, we adopt the nonparametric

maximum likelihood approach, under which  is regarded as a step function

with nonnegative jumps at the endpoints of the smallest intervals that bracket the failure

times. Specifically, if

is regarded as a step function

with nonnegative jumps at the endpoints of the smallest intervals that bracket the failure

times. Specifically, if  denotes the set

consisting of 0 and the unique values of

denotes the set

consisting of 0 and the unique values of  and

and

, then the estimator for

, then the estimator for

is a step function with jump size

is a step function with jump size

at

at  and with

and with  . Hence,

we maximize the function

. Hence,

we maximize the function

|

(2) |

Direct maximization of (2) is difficult due to the lack of an

analytical expression for the parameters

. An

even more severe challenge is that not all the

. An

even more severe challenge is that not all the  and

and  are informative

about the failure times, so many of the

are informative

about the failure times, so many of the  are zero and hence lie on

the boundary of the parameter space. For example, if there are no interval endpoints

between some

are zero and hence lie on

the boundary of the parameter space. For example, if there are no interval endpoints

between some  and

and  with

with  , then the

jump size at

, then the

jump size at  must be zero in order to maximize (2). The existing iterative convex minorant

algorithm works only for the proportional hazards and proportional odds models with

time-independent covariates (Huang & Wellner,

1997). In the following, we construct an EM algorithm to maximize (2).

must be zero in order to maximize (2). The existing iterative convex minorant

algorithm works only for the proportional hazards and proportional odds models with

time-independent covariates (Huang & Wellner,

1997). In the following, we construct an EM algorithm to maximize (2).

For the class of frailty-induced transformations described in §2.1, the observed-data likelihood can be written as

|

so that the estimation of the transformation

model becomes that of the proportional hazards frailty model. With

as a step function with jumps

as a step function with jumps  at

at

, this likelihood

becomes

, this likelihood

becomes

|

(3) |

where  .

We introduce latent variables

.

We introduce latent variables

which, conditional on

which, conditional on  , are independent Poisson random variables with means

, are independent Poisson random variables with means

. We show below that the

nonconcave likelihood function given in (3) is equivalent to a likelihood function for these Poisson variables, so the

M-step becomes maximization of a weighted sum of Poisson loglikelihood functions which is

strictly concave and has closed-form solutions for

. We show below that the

nonconcave likelihood function given in (3) is equivalent to a likelihood function for these Poisson variables, so the

M-step becomes maximization of a weighted sum of Poisson loglikelihood functions which is

strictly concave and has closed-form solutions for

. Similar Poisson

variables were recently used by Wang et al.

(2015) in spline-based estimation of the proportional hazards model with

time-independent covariates.

. Similar Poisson

variables were recently used by Wang et al.

(2015) in spline-based estimation of the proportional hazards model with

time-independent covariates.

Define  and

and  . Suppose that the observed data consist of

. Suppose that the observed data consist of

, where

, where

means that

means that  is known to be zero and that

is known to be zero and that

means that

means that  is known to be positive, such that

is known to be positive, such that

for

for  and at least one

and at least one

for

for  with

with

. Then the likelihood takes the form

. Then the likelihood takes the form

|

(4) |

which is the same as (3). Thus, maximization of (3) is equivalent to maximum likelihood

estimation based on the data

.

.

We maximize (4) through an EM

algorithm by treating  and

and  as missing data. The

complete-data loglikelihood is

as missing data. The

complete-data loglikelihood is

|

(5) |

where  . In the M-step, we calculate

. In the M-step, we calculate

|

(6) |

where  denotes the posterior mean given the observed data. After incorporating (6) into the conditional expectation of

(5), we update

denotes the posterior mean given the observed data. After incorporating (6) into the conditional expectation of

(5), we update

by solving the following equation using the one-step

Newton–Raphson method:

by solving the following equation using the one-step

Newton–Raphson method:

|

In the E-step, we evaluate the posterior means  and

and

. The posterior density function of

. The posterior density function of

given the observed data is proportional to

given the observed data is proportional to

, where

, where

and

and

. Hence, we

evaluate the posterior means by noting that for

. Hence, we

evaluate the posterior means by noting that for  ,

,

|

and for  with

with  ,

,

|

which can be calculated using Gaussian–Laguerre quadrature. In addition,

|

where  for any function

for any function  .

.

We iterate between the E- and M-steps until the sum of the absolute differences of the

estimates at two successive iterations is less than, say,  . This EM

algorithm has several desirable features. First, the conditional expectations in the

E-step involve at most one-dimensional integration, so they can be evaluated accurately by

Gaussian quadrature. Second, in the M-step, the high-dimensional parameters

. This EM

algorithm has several desirable features. First, the conditional expectations in the

E-step involve at most one-dimensional integration, so they can be evaluated accurately by

Gaussian quadrature. Second, in the M-step, the high-dimensional parameters

are calculated

explicitly, while the low-dimensional parameter vector

are calculated

explicitly, while the low-dimensional parameter vector  is updated

by the Newton–Raphson method. In this way, the algorithm avoids the inversion of any

high-dimensional matrices. Finally, the observed-data likelihood is guaranteed to increase

after each iteration. To avoid local maxima, we suggest using a range of initial values

for

is updated

by the Newton–Raphson method. In this way, the algorithm avoids the inversion of any

high-dimensional matrices. Finally, the observed-data likelihood is guaranteed to increase

after each iteration. To avoid local maxima, we suggest using a range of initial values

for  while setting

while setting  to

to  . We denote the

final results by

. We denote the

final results by  .

.

2.3. Variance estimation

We use profile likelihood (Murphy & van der

Vaart, 2000) to estimate the covariance matrix of  .

Specifically, we define the profile loglikelihood

.

Specifically, we define the profile loglikelihood

|

where  is the set

of step functions with nonnegative jumps at

is the set

of step functions with nonnegative jumps at  . Then the covariance matrix of

. Then the covariance matrix of

is estimated by the negative inverse of the matrix

whose

is estimated by the negative inverse of the matrix

whose  th element is

th element is

|

where  is the

is the

th canonical vector in

th canonical vector in  and

and

is a constant of order

is a constant of order  . To

calculate

. To

calculate  for each

for each  , we reuse the proposed EM

algorithm with

, we reuse the proposed EM

algorithm with  held fixed. Thus, the only step in the EM algorithm is

to explicitly evaluate

held fixed. Thus, the only step in the EM algorithm is

to explicitly evaluate  and

and  so as

to update

so as

to update  using (6). The iteration converges quickly with

using (6). The iteration converges quickly with  as

the initial value.

as

the initial value.

3. Asymptotic theory

We establish the asymptotic properties of  under the

following regularity conditions.

under the

following regularity conditions.

Condition 1. —

The true value of

, denoted by

, lies in the interior of a known compact set

in

, and the true value of

, denoted by

, is continuously differentiable with positive derivatives in

, where

is the union of the supports of

.

Condition 2. —

The vector

is uniformly bounded with uniformly bounded total variation over

, and its left limit exists for any

. In addition, for any continuously differentiable function

, the expectations

are continuously differentiable in

, where

and

are increasing functions in the decomposition

.

Condition 3. —

If

for all

with probability 1, then

for

and

.

Condition 4. —

The number of monitoring times,

, is positive, and

. The conditional probability

is greater than some positive constant

. In addition,

for some positive constant

. Finally, the conditional densities of

given

and

, denoted by

, have continuous second-order partial derivatives with respect to

and

when

and are continuously differentiable with respect to

.

Condition 5. —

The transformation function

is twice continuously differentiable on

with

,

and

.

Remark 2. —

Condition 1 is standard in survival analysis. Condition 2 allows

to have discontinuous trajectories, but the expectation of any smooth functional of

must be differentiable. One example would be that

is a stochastic process with a finite number of piecewise-smooth trajectories, where the discontinuity points have a continuous joint distribution. This condition excludes taking Brownian motion as a process for

. Condition 3 holds if the matrix

is nonsingular for some

. Condition 4 pertains to the joint distribution of monitoring times. First, it requires that the monitoring occur anywhere in

and that the largest monitoring time be equal to

with positive probability. The latter assumption may be removed, at the expense of more complicated proofs. Condition 4 also requires that two adjacent monitoring times be separated by at least

; otherwise, the data may contain exact observations, which would entail a different theoretical treatment. The smoothness condition for the joint density of monitoring times is used to prove the Donsker property of some function classes and the smoothness of the least favourable direction. Finally, Condition 5 pertains to the transformation function and holds for both the logarithmic family

and the Box–Cox family

.

The following theorem establishes the strong consistency of  .

.

Theorem 1. —

Under Conditions 1–5,

almost surely as

, where

is the Euclidean norm.

It is implicitly assumed in Theorem 1 that  is restricted to

is restricted to

, although in practice

, although in practice  is allowed

to be very large. The proof of Theorem 1 is based on the Kullback–Leibler information and

makes use of the strong consistency of empirical processes. Careful arguments are needed to

establish a preliminary bound for

is allowed

to be very large. The proof of Theorem 1 is based on the Kullback–Leibler information and

makes use of the strong consistency of empirical processes. Careful arguments are needed to

establish a preliminary bound for  and to handle

time-dependent covariates. Our next theorem establishes the asymptotic normality and

semiparametric efficiency of

and to handle

time-dependent covariates. Our next theorem establishes the asymptotic normality and

semiparametric efficiency of  .

.

Theorem 2. —

Under Conditions 1–5,

converges in distribution as

to a zero-mean normal random vector whose covariance matrix attains the semiparametric efficiency bound.

The proof of Theorem 2 relies on the derivation of the least favourable submodel for

and utilizes modern empirical process theory. A key step

is to show that

and utilizes modern empirical process theory. A key step

is to show that  converges to

converges to  at the

at the

rate. Although the general procedure is similar to

that of Huang & Wellner (1997), a major

innovation is the derivation of the least favourable submodel for general interval censoring

and time-dependent covariates by carefully handling the trajectories of

rate. Although the general procedure is similar to

that of Huang & Wellner (1997), a major

innovation is the derivation of the least favourable submodel for general interval censoring

and time-dependent covariates by carefully handling the trajectories of

and the joint distribution of

and the joint distribution of  . The

existence of the least favourable submodel is also used at the end of the Appendix to show

consistency of the profile-likelihood covariance estimator given in §2.3.

. The

existence of the least favourable submodel is also used at the end of the Appendix to show

consistency of the profile-likelihood covariance estimator given in §2.3.

4. Simulation studies

We conducted simulation studies to assess the operating characteristics of the proposed

numerical and inferential procedures. In the first study, we considered two time-independent

covariates,  and

and  . In the second study, we allowed

. In the second study, we allowed

to vary over time by imitating two-stage randomization:

to vary over time by imitating two-stage randomization:

, where

, where  and

and

are independent

are independent  and

and  with

with

. In both studies, we generated the failure times from the

transformation model

. In both studies, we generated the failure times from the

transformation model

|

where

. We set

. We set

,

,  and

and

. To create interval censoring, we randomly generated

two monitoring times,

. To create interval censoring, we randomly generated

two monitoring times,  and

and  , so that the time axis

, so that the time axis

was partitioned into three intervals,

was partitioned into three intervals,

,

,  and

and  . On

average, there were 25–35% left-censored observations and 50–60% right-censored ones. We set

. On

average, there were 25–35% left-censored observations and 50–60% right-censored ones. We set

, 400 or 800 and used 10 000 replicates for each

sample size.

, 400 or 800 and used 10 000 replicates for each

sample size.

For each dataset, we applied the proposed EM algorithm by setting the initial value of

to 0 and the initial value of

to 0 and the initial value of  to

to

, and we set the convergence threshold to

, and we set the convergence threshold to

. We also tried other initial values for

. We also tried other initial values for

, but they all led to the same estimates. For the variance

estimation, we set

, but they all led to the same estimates. For the variance

estimation, we set  , but the results differed only in the third

decimal place if we used

, but the results differed only in the third

decimal place if we used  or

or  . There was

no nonconvergence in any of the EM iterations.

. There was

no nonconvergence in any of the EM iterations.

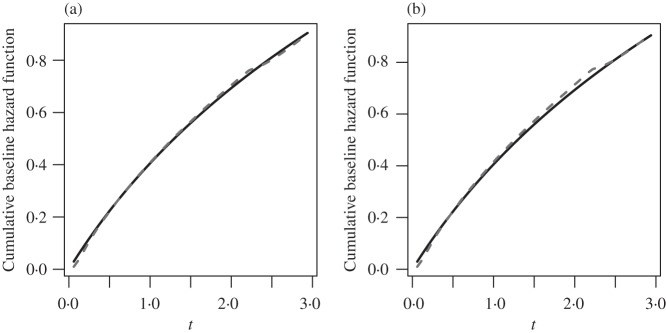

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the results of the two simulation studies under

or 1. The parameter estimators have small bias, and the

bias decreases rapidly as

or 1. The parameter estimators have small bias, and the

bias decreases rapidly as  increases. The variance estimators accurately reflect

the true variabilities, and the confidence intervals have proper coverage probabilities. As

shown in Fig. 1, the estimated cumulative hazard

functions have negligible bias.

increases. The variance estimators accurately reflect

the true variabilities, and the confidence intervals have proper coverage probabilities. As

shown in Fig. 1, the estimated cumulative hazard

functions have negligible bias.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for the simulation study with time-independent covariates

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Est | SE | SEE | CP | Est | SE | SEE | CP | Est | SE | SEE | CP | ||||

| 0 |

|

0 515 515 |

0 209 209 |

0 216 216 |

96 | 0 506 506 |

0 148 148 |

0 149 149 |

95 | 0 503 503 |

0 103 103 |

0 104 104 |

95 | |||

|

515 515 |

0 366 366 |

0 354 354 |

94 |

505 505 |

0 254 254 |

0 248 248 |

95 |

504 504 |

0 176 176 |

0 174 174 |

95 | ||||

|

|

0 514 514 |

0 255 255 |

0 259 259 |

96 | 0 507 507 |

0 180 180 |

0 176 176 |

94 | 0 503 503 |

0 125 125 |

0 125 125 |

95 | |||

|

516 516 |

0 451 451 |

0 434 434 |

94 |

505 505 |

0 311 311 |

0 303 303 |

94 |

503 503 |

0 215 215 |

0 212 212 |

94 | ||||

| 1 |

|

0 516 516 |

0 294 294 |

0 297 297 |

95 | 0 506 506 |

0 209 209 |

0 207 207 |

95 | 0 504 504 |

0 145 145 |

0 144 144 |

95 | |||

|

517 517 |

0 522 522 |

0 503 503 |

94 |

505 505 |

0 358 358 |

0 350 350 |

95 |

502 502 |

0 249 249 |

0 244 244 |

94 | ||||

Est, empirical average of the parameter estimator; SE, standard error of the parameter estimator; SEE, empirical average of the standard error estimator; CP, empirical coverage percentage of the 95% confidence interval.

Table 2.

Summary statistics for the simulation study with time-dependent covariates

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Est | SE | SEE | CP | Est | SE | SEE | CP | Est | SE | SEE | CP | ||||

| 0 |

|

0 529 529 |

0 241 241 |

0 239 239 |

95 | 0 518 518 |

0 166 166 |

0 164 164 |

95 | 0 509 509 |

0 114 114 |

0 114 114 |

95 | |||

|

515 515 |

0 363 363 |

0 353 353 |

95 |

511 511 |

0 253 253 |

0 247 247 |

94 |

503 503 |

0 175 175 |

0 173 173 |

95 | ||||

|

|

0 533 533 |

0 292 292 |

0 280 280 |

94 | 0 522 522 |

0 198 198 |

0 193 193 |

94 | 0 511 511 |

0 138 138 |

0 134 134 |

94 | |||

|

514 514 |

0 441 441 |

0 433 433 |

95 |

512 512 |

0 307 307 |

0 302 302 |

95 |

503 503 |

0 214 214 |

0 211 211 |

95 | ||||

| 1 |

|

0 537 537 |

0 336 336 |

0 317 317 |

94 | 0 525 525 |

0 228 228 |

0 219 219 |

94 | 0 514 514 |

0 157 157 |

0 152 152 |

94 | |||

|

518 518 |

0 512 512 |

0 502 502 |

95 |

513 513 |

0 358 358 |

0 349 349 |

95 |

505 505 |

0 250 250 |

0 243 243 |

94 | ||||

Fig. 1.

Estimation of  with

with  , for (a)

, for (a)

and (b)

and (b)  . The solid and

dashed curves represent the true values and mean estimates, respectively.

. The solid and

dashed curves represent the true values and mean estimates, respectively.

We conducted an additional simulation study with five covariates. We set

to zero-mean normal with unit variances and pairwise

correlations of 0

to zero-mean normal with unit variances and pairwise

correlations of 0 5 and took

5 and took  ; the other simulation settings were left unchanged. The

results are summarized in the Supplementary Material. The proposed methods performed well in

this simulation too. Again, there were no cases of nonconvergence.

; the other simulation settings were left unchanged. The

results are summarized in the Supplementary Material. The proposed methods performed well in

this simulation too. Again, there were no cases of nonconvergence.

To evaluate the performance of the EM algorithm in even larger datasets, we set

and

and  to ten standard normal random variables

with pairwise correlations of 0

to ten standard normal random variables

with pairwise correlations of 0 25 and regression coefficients of

0

25 and regression coefficients of

0 5. The algorithm converged to values close to

0

5. The algorithm converged to values close to

0 5 in all 10 000 replicates.

5 in all 10 000 replicates.

5. Application

The Bangkok Metropolitan Administration conducted a cohort study of 1209 injecting drug users who were initially sero-negative for the HIV-1 virus. Subjects from 15 drug treatment clinics were followed from 1995 to 1998. At study enrolment and approximately every four months thereafter, subjects were assessed for HIV-1 sero-positivity through blood tests. As of December 1998 there were 133 HIV-1 sero-conversions and roughly 2300 person-years of follow-up.

We aim to identify the factors that influence HIV-1 infection. We fit model (1) with the class of logarithmic

transformations

. The

covariates include age at recruitment, gender, history of needle sharing, and drug injection

in jail before recruitment; age is measured in years, gender takes value 1 for male and 0

for female, and history of needle sharing and drug injection are binary indicators of yes or

no. In addition, we include a time-dependent covariate indicating imprisonment since the

last clinic visit.

. The

covariates include age at recruitment, gender, history of needle sharing, and drug injection

in jail before recruitment; age is measured in years, gender takes value 1 for male and 0

for female, and history of needle sharing and drug injection are binary indicators of yes or

no. In addition, we include a time-dependent covariate indicating imprisonment since the

last clinic visit.

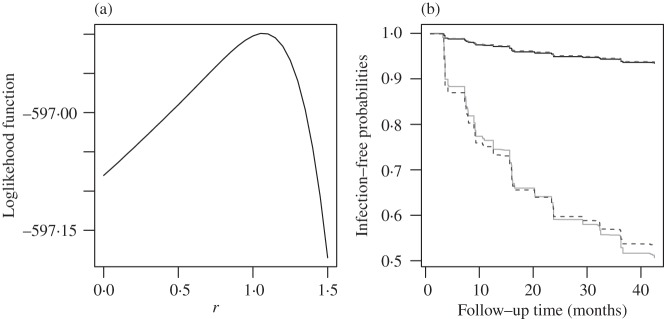

To select a transformation function, we vary  from 0 to 1

from 0 to 1 5 in steps of

0

5 in steps of

0 05. For each

05. For each  , we estimate

, we estimate  and

and

by the EM algorithm and evaluate the loglikelihood at the

parameter estimates. Figure 2(a) shows that the

loglikelihood changes only very slowly as

by the EM algorithm and evaluate the loglikelihood at the

parameter estimates. Figure 2(a) shows that the

loglikelihood changes only very slowly as  varies and is maximized at

varies and is maximized at

. We choose

. We choose  , which corresponds to the

proportional odds model. Table 3 shows the

results under this model. For comparison, we also include the results for

, which corresponds to the

proportional odds model. Table 3 shows the

results under this model. For comparison, we also include the results for

, which corresponds to the proportional hazards model.

, which corresponds to the proportional hazards model.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration HIV-1 study: (a) the loglikelihood

at the nonparametric maximum likelihood estimates plotted as a function of

in the logarithmic transformations; (b) estimation of

infection-free probabilities, where the upper lines correspond to a low-risk subject

under the proportional hazards (solid) and proportional odds (dashed) models, and the

lower lines correspond to a high-risk subject under the proportional hazards (solid) and

proportional odds (dashed) models.

in the logarithmic transformations; (b) estimation of

infection-free probabilities, where the upper lines correspond to a low-risk subject

under the proportional hazards (solid) and proportional odds (dashed) models, and the

lower lines correspond to a high-risk subject under the proportional hazards (solid) and

proportional odds (dashed) models.

Table 3.

Regression analysis of the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration HIV-1 infection data

| Proportional hazards | Proportional odds | |||||||

| Covariates | Estimate | Standard error |

-value -value |

Estimate | Standard error |

-value -value |

||

| Age |

028 028 |

0 012 012 |

0 021 021 |

031 031 |

0 013 013 |

0 016 016 |

||

| Gender | 0 424 424 |

0 270 270 |

0 117 117 |

0 539 539 |

0 310 310 |

0 082 082 |

||

| Needle sharing | 0 237 237 |

0 183 183 |

0 196 196 |

0 251 251 |

0 196 196 |

0 200 200 |

||

| Drug injection | 0 313 313 |

0 184 184 |

0 089 089 |

0 360 360 |

0 198 198 |

0 069 069 |

||

| Imprisonment over time | 0 502 502 |

0 211 211 |

0 017 017 |

0 494 494 |

0 219 219 |

0 024 024 |

||

Under either model, ageing reduces the risk of HIV-1 infection, whereas being male increases it. In addition, drug injection increases the risk. Finally, subjects who have recently been imprisoned have an elevated risk of HIV-1 infection.

Figure 2(b) shows the prediction of HIV-1 infection for a low-risk subject versus a high-risk subject. The low-risk subject is a 50-year-old female with no history of needle sharing, no drug injection in jail before recruitment, and no imprisonment during follow-up; the high-risk subject is a 20-year-old male with a history of needle sharing, drug injection in jail before recruitment, and imprisonment over time. The estimated probabilities of infection for the low-risk subject are similar under the proportional odds and proportional hazards models. For the high-risk subject, however, the proportional odds model yields slightly higher risks of infection than the proportional hazards model during the first part of the follow-up period, with the opposite being true during the later part of the follow-up period.

6. Remarks

The presence of time-dependent covariates poses major computational and theoretical

challenges. With time-dependent covariates, the parameters  and

and

in the likelihood

function are entangled. As a result, the diagonal approximation to the Hessian matrix in the

iterative convex minorant algorithm (Huang &

Wellner, 1997) is inaccurate, and the algorithm becomes unstable. By contrast, each

iteration of our EM algorithm only solves a low-dimensional equation for

in the likelihood

function are entangled. As a result, the diagonal approximation to the Hessian matrix in the

iterative convex minorant algorithm (Huang &

Wellner, 1997) is inaccurate, and the algorithm becomes unstable. By contrast, each

iteration of our EM algorithm only solves a low-dimensional equation for

while calculating the jump sizes of

while calculating the jump sizes of

explicitly as weighted sums of Poisson rates. Thus, our

algorithm is fast and stable. In extensive numerical studies we have never encountered

nonconvergence. Our software is available at http://dlin.web.unc.edu/software.

explicitly as weighted sums of Poisson rates. Thus, our

algorithm is fast and stable. In extensive numerical studies we have never encountered

nonconvergence. Our software is available at http://dlin.web.unc.edu/software.

Our theoretical development requires that the population average of the covariate process

be smooth but allows individual covariate trajectories to be discontinuous. We treat

as a bundled process of

as a bundled process of

and

and  when proving the identifiability

of

when proving the identifiability

of  in Theorem 1, the convergence rate of

in Theorem 1, the convergence rate of

in Lemma A1, and the invertibility of the information

operator in Theorem 2. The Donsker property for this class of processes indexed by

in Lemma A1, and the invertibility of the information

operator in Theorem 2. The Donsker property for this class of processes indexed by

is used repeatedly in the proofs. Besides time-dependent

covariates, one major theoretical challenge is dealing with general interval censoring,

which allows each subject to have a different number of monitoring times. In particular, the

derivation of the least favourable direction for

is used repeatedly in the proofs. Besides time-dependent

covariates, one major theoretical challenge is dealing with general interval censoring,

which allows each subject to have a different number of monitoring times. In particular, the

derivation of the least favourable direction for  requires

careful consideration of the joint distribution for an arbitrary sequence of monitoring

times, and the Lax–Milgram theorem is used to prove the existence of a least favourable

direction. That theorem greatly simplifies the proof, in contrast to the approach of Huang & Wellner (1997), even for case-2

data.

requires

careful consideration of the joint distribution for an arbitrary sequence of monitoring

times, and the Lax–Milgram theorem is used to prove the existence of a least favourable

direction. That theorem greatly simplifies the proof, in contrast to the approach of Huang & Wellner (1997), even for case-2

data.

To apply the transformation model to real data, one must choose a transformation function. In the analysis of the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration HIV-1 data, we used the aic to select the transformation function, although the likelihood surface is fairly flat. It would be worthwhile to develop formal diagnostic procedures to check the appropriateness of the transformation function and other model assumptions. One possible strategy is to examine the behaviour of the posterior mean of the martingale residuals (Chen et al., 2012) given the observed intervals.

In many applications, the event of interest may occur repeatedly over time. Recurrent events under interval censoring are called panel count data, which have been studied by Sun & Wei (2000), Zhang (2002) and Wellner & Zhang (2007), among others. There are also studies in which each subject can experience different types of events or where subjects are sampled in clusters such that the failure times with the same cluster are correlated. We are currently developing regression methods to handle such multivariate failure time data.

We are also extending our work to competing risks data. Indeed, the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration HIV-1 study contains information on HIV-1 infection by viral subtypes B and E, which are two competing risks. We propose to formulate the effects of potentially time-dependent covariates on the cumulative incidence functions of competing risks in the form of model (1). We will modify the EM algorithm to deal with multiple subdistribution functions and establish the asymptotic theory under suitable conditions.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The authors thank the editor, an associate editor and a referee for helpful comments.

Appendix A. Appendix

Technical details

We use  to denote the empirical measure from

to denote the empirical measure from

independent observations and

independent observations and

to denote the true probability measure. The

corresponding empirical process is

to denote the true probability measure. The

corresponding empirical process is  . Let

. Let  be the

observed-data loglikelihood for a single subject, that is,

be the

observed-data loglikelihood for a single subject, that is,

|

Proof of Theorem 1. —

We first show that

with probability 1. By Condition 4, the measure generated by the function

is dominated by the sum of the Lebesgue measure in

and the counting measure at

, and its Radon–Nikodym derivative, denoted by

, is bounded away from zero. We define

Clearly,

is a step function with jumps only at

. Since

uniformly in

with probability 1 as

, we conclude that

converges uniformly to

with probability 1 for

.

By the definition of

, we have

. Because of its bounded total variation,

belongs to a Donsker class indexed by

. Hence, the class of functions

where

denotes functions which have total variation in

bounded by a given constant

, is a convex hull of functions

, so it is a Donsker class. Furthermore,

is bounded away from zero. Therefore,

belongs to some Donsker class due to the preservation property of the Donsker class under Lipschitz-continuous transformations. We conclude that

almost surely. In addition, by the construction of

,

converges almost surely to

, which is finite. Therefore, with probability 1,

(A1) Let

be such that

for

. Then the left-hand side of (A1) is less than or equal to

Hence

. Since as

,

, which is positive, Condition 5 implies that

with probability 1.

We can now restrict

to a class of functions with uniformly bounded total variation, equipped with the weak topology on

. By Helly's selection lemma, for any subsequence of

we can choose a further subsequence such that

converges weakly to some

on

,

converges to

, and

converges to

. Clearly,

implies that

, where

, so that

By the above arguments for proving the Donsker property of

, together with the fact that the total variation of

is bounded by a constant, we can show that

belongs to a Donsker class with a bounded envelope function, so that

. It follows that

Furthermore,

where

is the measure corresponding to

. According to Conditions 2 and 4,

is dominated by the Lebesgue measure with bounded derivative in

and has a point mass at

. Hence

almost surely. We therefore conclude that

By the properties of the Kullback–Leibler information,

with probability 1. In particular, for any

, we choose

to obtain

Thus, for any

,

(A2) Differentiating both sides with respect to

, we have

By Condition 3,

and

for

. We let

by redefining

to centre at a deterministic function in the support of

, and we set

in (A2) to obtain

. Hence,

for

. It follows that

and

converges weakly to

almost surely. The latter convergence can be strengthened to uniform convergence since

is continuous. Thus, we have proved Theorem 1. □

Since we have established consistency, we may restrict the space of

to

to

|

for some  . Thus, when

. Thus, when

is large enough,

is large enough,  belongs to

belongs to  with probability 1. Before proving Theorem 2, we need

to establish the convergence rate for

with probability 1. Before proving Theorem 2, we need

to establish the convergence rate for  . Specifically, the

following lemma holds.

. Specifically, the

following lemma holds.

Lemma A1. —

Under Conditions 1–5,

Proof. —

The proof relies on the convergence-rate result in Theorem 3.4.1 of van der Vaart & Wellner (1996). To use that theorem, we define

and let

be a class of functions indexed by

and

.

We first calculate the

-bracketing number of

. Because

consists of increasing and uniformly bounded functions on

, Lemma 2.2 of van de Geer (2000) implies that for any

, the bracketing number satisfies

where

denotes the

-norm with respect to the Lebesgue measure on

, and

means that

for a positive constant

. For

, we can find

number of brackets

with

and

to cover

. In addition, there are

number of brackets covering

, such that any two

within the same bracket differ by at most

. Hence, there are a total of

brackets covering

. For any pair of

and

, there exist some constants

and

such that

Because the measures

and

have bounded derivatives with respect to the Lebesgue measure in

and the former has a finite point mass at

,

Thus, the bracketing number for

satisfies

and so it has a finite entropy integral. Define

It is easy to show that

. In addition, by Lemma 1.3 of van de Geer (2000),

where

is the Hellinger distance, defined as

with respect to the dominating measure

.

The above results, together with the fact that

maximizes

and the consistency result in Theorem 1, imply that all the conditions in Theorem 3.4.1 of van der Vaart & Wellner (1996) hold. Thus, we conclude that

, where

satisfies

. In particular, we can choose

in the order of

such that

. By the mean value theorem,

On the left-hand side of the above equation, we consider the event

to find that

Next, we consider

to obtain the same equation as the one above but with

replaced by

. By repeating this process, we conclude that, conditional on

and for any

,

It then follows from the mean value theorem that

and so the lemma is proved. □

Now we are ready to prove Theorem 2.

Proof of Theorem 2. —

It is helpful to introduce the following notation:

,

and

The score function for

is

To obtain the score operator for

, we consider any parametric submodel of

defined by

, where

. The score function along this submodel is

Clearly,

and

. Hence

We apply Taylor series expansions about

to the right-hand sides of the above two equations. By Lemma A1, the second-order terms are bounded by

Hence

(A3)

(A4) where

is the second derivative of

with respect to

,

is the derivative of

along the submodel

,

is the derivative of

with respect to

, and

is the derivative of

along the submodel

. All the derivatives on the right-hand sides of (A3) and (A4) are evaluated at

.

We choose

to be the least favourable direction

, a

-vector with components in

that solves the normal equation

(A5) where

is the adjoint operator of

. Then

so that the difference between (A3) and (A4) yields

(A6) Consequently, Theorem 2 will be established if we can show that:

equation (A5) has a solution

;

belongs to a Donsker class and converges in the

-norm to

;

the matrix

is invertible.

The reason is that when (i)–(iii) hold, (A6) entails

and further yields

This implies that the influence function for

is exactly the efficient influence function, so that

converges to a zero-mean normal random vector whose covariance matrix attains the semiparametric efficiency bound (Bickel et al., 1993, p. 65).

We first verify (i). For any

,

where

Likewise,

Therefore, by the definition of the dual operator

, solving the normal equation (A2) is equivalent to solving the integral equation

(A7) We define the left-hand side of (A7) as a linear operator

which maps

to itself. In addition, we equip

with an inner product

so that it becomes a Hilbert space. On the same space, we define

. It is easy to show that

is a seminorm for

. Furthermore, if

, then

. Thus, with probability 1,

is zero, i.e., for any

,

Setting

we obtain

Thus,

for

, implying that

is a norm in

. Clearly,

for some constant

. According to the bounded inverse theorem in Banach spaces, we have

for another constant

; that is, we have

. By the Lax–Milgram theorem (Zeidler, 1995), the solution to (A7), namely

exists. So we have verified (i).

To verify (ii), we examine

by considering

and

. Along the lines of Huang & Wellner (1997), we differentiate the integral equation (A7) with respect to

to obtain

where

and

are continuously differentiable with respect to their arguments. Hence

is continuously differentiable in

. This fact implies that

belongs to some Donsker class. It then follows from the Donsker property of the class

that (ii) is true.

Finally, we verify (iii). If the matrix is singular, then there exists a nonzero vector

such that

It follows that, with probability 1, the score function along the submodel

is zero; that is, for any

,

where

. We consider

for

to obtain

Therefore, with probability 1,

for any

. This implies that

, so

by Condition 3. Thus, we have verified (iii). □

Remark A1. —

For a given

, we define

as the step function that maximizes

. The arguments in the proof of Theorem 1 can be used to show that

is bounded asymptotically when

is in a small neighbourhood of

, so

converges to

as

converges to

. In addition, the arguments in the proof of Lemma A1 yield

in the

space. Finally, in light of the existence of

in the proof of Theorem 2, we can define

to obtain the least favourable submodel as

, where

is in a neighbourhood of

. Thus, we can easily verify conditions (8), (9) and (10) of Murphy & van der Vaart (2000) for the likelihood function along this submodel. Along with the Donsker property of the functional classes for the first and second derivatives of

with respect to

and

, we conclude that Theorem 1 of Murphy & van der Vaart (2000) is applicable, and hence the covariance matrix estimator given in §2.3 with

is consistent for the limiting covariance matrix of

.

References

- Bickel P. J., Klaassen C. A. J., Ritov Y. & Wellner J. A. (1993). Efficient and Adaptive Estimation for Semiparametric Models. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Jin Z. & Ying Z. (2002). Semiparametric analysis of transformation models with censored data. Biometrika 89, 659–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Lin D. Y. & Zeng D. (2012). Checking semiparametric transformation models with censored data. Biostatistics 13, 18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu M. G., Sun L. & Zuo G. (2005). A baseline-free procedure for transformation models under interval censorship. Lifetime Data Anal. 11, 473–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. (1995). Maximum likelihood estimation for proportional odds regression model with current status data. In Analysis of Censored Data, vol. 27 of IMS Lecture Notes—Monograph Series, H. L. Koul and J. V. Deshpande, eds. Hayward: Institute of Mathematical Statistics, pp. 129–46.

- Huang J. (1996). Efficient estimation for the proportional hazards model with interval censoring. Ann. Statist. 24, 540–68. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. & Rossini A. J. (1997). Sieve estimation for the proportional-odds failure-time regression model with interval censoring. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 92, 960–7. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. & Wellner J. A. (1997). Interval censored survival data: A review of recent progress. In Proc. 1st Seattle Symp. Biostatist.: Survival Anal., D. Y. Lin and T. R. Fleming, eds. New York: Springer, pp. 123–69.

- Murphy S. A. & van der Vaart A. W. (2000). On profile likelihood. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 95, 449–65. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz D., Betensky R. A. & Tsiatis A. A. (2000). Using conditional logistic regression to fit proportional odds models to interval censored data. Biometrics 56, 511–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossini A. J. & Tsiatis A. A. (1996). A semiparametric proportional odds regression model for the analysis of current status data. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 91, 713–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schick A. & Yu Q. (2000). Consistency of the GMLE with mixed case interval-censored data. Scand. J. Statist. 27, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shen X. (1998). Proportional odds regression and sieve maximum likelihood estimation. Biometrika 85, 165–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sun J. & Sun L. (2005). Semiparametric linear transformation models for current status data. Can. J. Statist. 33, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sun J. & Wei L. J. (2000). Regression analysis of panel count data with covariate-dependent observation and censoring times. J. R. Statist. Soc. B 62, 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- van de Geer S. A. (2000). Empirical Process Theory and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van der Vaart A. W. & Wellner J. A. (1996) Weak Convergence and Empirical Processes. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., McMahan C. S., Hudgens M. G. & Qureshi Z. P. (2015). A flexible, computationally efficient method for fitting the proportional hazards model to interval-censored data. Biometrics72, 222–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wellner J. A. & Zhang Y. (2007). Two likelihood-based semiparametric estimation methods for panel count data with covariates. Ann. Statist. 35, 2106–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zeidler E. (1995). Applied Functional Analysis: Applications to Mathematical Physics. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng D. & Lin D. Y. (2006). Efficient estimation of semiparametric transformation models for counting processes. Biometrika 93, 627–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. (2002). A semiparametric pseudolikelihood estimation method for panel count data. Biometrika 89, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. & Zhao Y. (2013). Empirical likelihood for linear transformation models with interval-censored failure time data. J. Mult. Anal. 116, 398–409. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Sun L., Zhao X. & Sun J. (2005). Regression analysis of interval-censored failure time data with linear transformation models. Can. J. Statist. 33, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.