Summary

Sirtuin-family deacylases promote health and longevity in mammals. The sirtuin SIRT5 localizes predominantly to the mitochondrial matrix. SIRT5 preferentially removes negatively charged modifications from its target lysines: succinylation, malonylation, and glutarylation. It regulates protein substrates involved in glucose oxidation, ketone body formation, ammonia detoxification, fatty acid oxidation, and ROS management. Like other sirtuins, SIRT5 has recently been linked with neoplasia. Therefore, targeting SIRT5 pharmacologically could conceivably provide new avenues for treatment of metabolic disease and cancer, necessitating development of SIRT5-selective modulators. Here we describe the generation of SIRT5 bacterial expression plasmids, and their use to express and purify catalytically active and inactive forms of SIRT5 protein from E. coli. Additionally, we describe an approach to assay the catalytic activity of purified SIRT5, potentially useful for identification and validation of SIRT5-specific modulators.

Keywords: Sirtuins, Site Directed Mutagenesis, Desuccinylation, PDC, E1α, PDHA1

1. Introduction

Sirtuins are NAD+-dependent enzymes that regulate diverse cellular processes, thereby maintaining metabolic homeostasis and genomic integrity (1). Mammals possess seven sirtuin family members (SIRT1-SIRT7) (2,3), which display diverse sub-cellular localization patterns, catalytic activities, protein targets, and biological functions (4,1,2). Owing to their ability to catalyze removal of acetyl moieties from lysine residues, sirtuins were initially described as class III deacetylases. However, certain members of the mammalian sirtuin family carry out a range of enzymatic activities other than deacetylation. SIRT3, the predominant mitochondrial deacetylase (5), has recently been shown to possess decrotonylase activity (6). Likewise, SIRT4 can catalyze both deacetylation and ADP-ribosylation reactions (7–9). The least well-characterized sirtuin, SIRT5, displays very low deacetylase activity (10); instead SIRT5 preferentially catalyzes removal of negatively charged modifications: malonylation, succinylation, and glutarylation (10–14). SIRT5-mediated modification of carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) (15,10,13), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase 2 (HMGCS2) (12), Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) (16) and urate oxidase (17) increases enzymatic activity, while desuccinylation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) by SIRT5 reduces their activities (11). PDC catalyzes oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate into acetyl-CoA, which is subsequently used in the Krebs cycle to generate ATP (18,19). In other contexts, altered activities of the SIRT5 targets, PDC and SDH, have been linked with neoplasia and cancer cell metabolic reprogramming (20,2). Additionally, SIRT5-mediated desuccinylation and activation of SOD1 suppresses ROS levels and promotes the growth of lung cancer cells (16). Recently, it has been shown that SIRT5 is overexpressed in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and promotes chemoresistance in NSCLC via enhancement of NRF2 activity. Consistently, SIRT5 knockdown represses the growth of NSCLC cell lines and increases their susceptibility to genotoxic drugs (21). These findings suggest a potential oncogenic function of SIRT5 in NSCLC.

Despite the fact that SIRT5 is broadly expressed (22,15), SIRT5-deficient mice are healthy, fertile, and without major clinical phenotype (23,5,12). This suggests that SIRT5 is largely dispensable for metabolic homeostasis at least under basal conditions, rendering it an attractive potential drug target. The production of catalytically active SIRT5 protein is first step towards identification of SIRT5-specific modulators.

Alternative splicing of the human SIRT5 mRNA results in two distinct SIRT5 protein isoforms, differing at their C-termini (24,25). Full-length isoform-1 comprises 310 amino acids, containing a 36 amino acid N-terminal mitochondrial localization signal (MLS) (26). The MLS is proteolytically removed during mitochondrial import, which results in a 274 amino acid mature SIRT5 protein (27,26,25). The second isoform comprises 299 amino acids. Whereas ectopically expressed isoform-1 is present throughout the cell, isoform-2 appears to be strictly mitochondrial (25). In mouse liver, SIRT5 protein is predominantly mitochondrial, but also present in the cytosol and the nucleus (11).

In this chapter, we describe a method for generation of catalytically active and inactive forms of mature, SIRT5 isoform-1 protein, utilizing the basic techniques of molecular cloning and biochemistry. Replacing a catalytic Histidine (H) residue with Tyrosine (Y) at position 158 of full length SIRT5 attenuates catalytic activity (13,15,11). Initially we describe site directed mutagenesis to replace C472 with T in the coding sequence of SIRT5. This single nucleotide change converts a Histidine (H) to a Tyrosine (Y) at position 158 of full-length, unprocessed SIRT5 protein. Then we discuss the cloning of SIRT5 and SIRT5C472T sequences, encoding the mature, processed forms (lacking the mitochondrial targeting signal) of SIRT5 and SIRT5H158Y proteins, respectively, into the bacterial expression plasmid pET15b. The pET15b plasmids harboring SIRT5 and SIRT5C472T sequences are then used for over-expression and purification of catalytically active and inactive (H158Y) forms of SIRT5 protein. Finally, a desuccinylation assay is described to evaluate the catalytic activity of purified proteins. The desuccinylation activity assay can further be exploited for the validation of SIRT5-specific modulators (inhibitors or activators), identified in large scale screening of compound libraries.

2. Materials

2.1. Insertion of H158Y Mutation into SIRT5 Coding Sequence and Preparation of SIRT5 and SIRT5-H158Y Bacterial Expression Plasmids with N-Terminal His-Tag

Human SIRT5-pBABE-puro plasmid DNA.

Custom-synthesized oligonucleotides.

10mM dNTP mix.

PfuUltra High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase and 10X PfuUltra High-Fidelity Reaction Buffer.

Thermocycler.

Dpn I restriction enzyme.

Chemical competent DH5α bacterial cells.

Water Bath.

LB Medium (1L): 10g Tryptone, 5g Yeast Extract, 10g NaCl.

LB-Agar (1L): 10g Tryptone, 5g Yeast Extract, 10g NaCl, 2g Agar.

50mg/ml Carbenicillin or 100mg/ml Ampicillin: Dissolve the required amount in autoclaved double distilled water and filter through 0.2μm syringe filter. Aliquot and store at −20°C.

Miniprep Plasmid Purification Kit.

50X TAE Stock (1L): 242g Tris Base (MW=121.1), 57.1mL Glacial Acetic Acid, and 100mL 0.5 M EDTA. Dissolve Tris in about 600mL of ddH2O. Then add EDTA and Acetic Acid and bring the final volume to 1L with ddH2O. Store at room temperature. This 50X stock solution can be diluted with water to make a 1X working solution.

Agarose.

PCR clean-up/purification kit.

pET15b plasmid.

Nde1 and Xho1 restriction enzymes.

Gel extraction kit.

T4 DNA Ligase and 10X DNA Ligase buffer.

Nanodrop spectrophotometer.

2.2 Bacterial Expression, Solubility Determination, and Purification of His Tagged SIRT5 and SIRT5-H158Y proteins

Chemical competent E. coli BL21 (DE3).

1M IPTG: Dissolve 2.38g of IPTG in 10ml of autoclaved double distilled water and filter through 0.2μm syringe filter. Aliquot and store at −20°C.

4X Laemmli buffer: 40% Glycerol, 240 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 8% SDS, 0.04% bromophenol blue, 5% beta-mercaptoethanol.

4–20% Polyacrylamide Gel.

1X Running Buffer: 0.1 % (w/v) SDS, 192 mM glycine, 400 mM Tris-base.

Coomassie brilliant blue stain.

Sonicator equipped with a microtip probe.

Lysozyme Solution: Dissolve 10 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0.

50% Ni-NTA slurry.

Lysis buffer: 50mM NaH2PO4, 300mM NaCl, 10mM imidazole. Adjust to pH 8.0 using NaOH.

Wash Buffer: 50mM NaH2PO4, 300mM NaCl, 20mM imidazole. Adjust to pH 8.0 using NaOH.

Elution Buffer: 50mM NaH2PO4, 300mM NaCl, 250mM imidazole, 5% Glycerol. Adjust pH 8.0 using NaOH.

Protein Concentration Assay Kit.

2.3 In Vitro Desuccinylation Assay

Porcine Heart PDC.

PDC Centrifugation Buffer: 100mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.5), 0.05% Lauryl Maltoside, 2.5mM EDTA, 30% Glycerol.

3X Reaction Buffer: 75mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 600mM NaCl, 15mM KCl, 3mM, MgCl2, 0.3% PEG 8000, 9.375mM NAD+.

1X Running Buffer: 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 192mM glycine, 400mM Tris-base.

1X Transfer Buffer: 192mM glycine, 400mM Tris-base, 20% Methanol. Store transfer buffer at 4°C.

PVDF membrane.

Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA).

Anti Lysine-Succinyl antibody.

Anti-Pyruvate Dehydrogenase E1-alpha subunit antibody.

1X TBST (Tris buffered saline containing 0.01 % Tween-20): 50mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.6, 150mM NaCl, 0.01% (v/v) Tween-20.

Ponceau S Staining Solution: 0.1% (w/v) Ponceau S, 5% (v/v) acetic acid.

Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate.

Stripping Buffer (1L): 15g Glycine, 1g SDS, 10ml Tween 20. Adjust pH to 2.2 using HCl.

1X PBS: 137mM NaCl, 2.7mM KCl, 10mM Na2HPO4, 2mM KH2PO4. Adjust pH to 7.4 using HCl.

3. Methods

3.1. Engineering H158Y Mutation into the SIRT5 Coding Sequence

-

Custom synthesize the following two complementary oligonucleotides containing the desired mutation (underlined), flanked by unmodified nucleotide sequence.

SIRT5 H158Y sense oligo: 5′GAACCTTCTGGAGATCTATGGTAGCTTATTTAAAAC 3′

SIRT5 H158Y anti-sense oligo: 5′ GTTTTAAATAAGCTACCATAGATCTCCAGAAGGTTC 3′

Resuspend oligos in appropriate amount of ddH2O to a final concentration of 100μM. Dilute further by adding ddH2O to a concentration of 10μM.

-

Set up a series of reactions using different amounts (5ng, 10ng, 20ng, and 50ng) of template DNA (human SIRT5-pBABE-puro plasmid) as below:

5μl of 10X PfuUltra HF Reaction Buffer

1μl of template DNA (5–50ng)

1.14μl of 10μM SIRT5 H158Y Top Oligo (125ng)

1.14μl of 10μM SIRT5 H158Y Bottom Oligo (125ng)

1μl of 10mM dNTP mix

1μl of PfuUltra HF DNA Polymerase (2.5U/μl)

39.72μl of ddH2O

-

Perform amplification reaction in a thermocycler, set to the following parameters:

95°C, 30 seconds

95°C, 30 seconds

55°C, 1 minute

68°C, 7.5 minutes

Repeat steps (ii) to (iv) for a total of 16 cycles

68°C, 10 minutes

4°C, Hold

Add 1μl of Dpn I restriction enzyme (10U/μl) to each reaction tube. Mix the contents gently and thoroughly by pipetting up and down multiple times. Spin down briefly, and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour to digest parental template DNA.

-

Transform Dpn I treated DNA into chemical competent DH5α bacteria via heat shock as below:

Thaw chemical competent DH5α bacterial cells on ice, and aliquot 50μl in separate fresh autoclaved tubes.

Transfer 1μl of Dpn I treated DNA from each sample tube to separate aliquots of chemical competent DH5α bacteria. Mix the content of tubes by gentle tapping and incubating on ice for 5 minutes.

Heat shock the transformation reactions for 90 seconds in a water bath set to 42°C, and immediately transfer the tubes to ice again for 5 min.

Add 1ml of LB medium to all tubes aseptically, and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour with shaking at 220rpm. Plate 50–100μl of the transformation mix on LB agar plates containing 50μg/ml carbenicillin or 100μg/ml ampicillin, and incubate at 37°C for ~16 hrs.

Inoculate few colonies (~4–6) from each plate into separate tubes containing 5ml LB medium with 50μg/ml carbenicillin or 100μg/ml ampicillin. Incubate overnight at 37°C with shaking at 220rpm.

Harvest the cells by centrifugation at 6,500 x g for 5 minutes at room temperature, and purify the plasmid DNA using a standard miniprep plasmid purification protocol or kit.

Confirm the insertion of desired mutation by nucleotide sequencing using pBABE sequencing primers (Weinberg Lab): 5′ CTTTATCCAGCCCTCAC 3′ and 5′ ACCCTAACTGACACACATTCC 3′.

3.2. Preparation of SIRT5 and SIRT5-H158Y Bacterial Expression Plasmids with N-Terminal His-Tag

-

Synthesize the following primers to amplify the SIRT5 coding sequence lacking the mitochondrial targeting signal, for in vitro studies. These oligos are designed to introduce appropriate restriction enzyme sites at each end of the amplified PCR product for subsequent cloning into the bacterial expression plasmid pET15b, which provides an in-frame His-tag followed by a thrombin site at the SIRT5 N-terminus.

SIRT5 forward primer with Nde1 restriction site (underlined): 5′ CCGGCATATGAGTTCAAGTATGGCAGATTTTCG 3′

SIRT5 reverse primer with Xho1 restriction site (underlined): 5′ CCGGCTCGAGTTAAGAAACAGTTTCATTTTC 3′

Make 10μM working solutions of both primers as described in section 3.1, step 3.

-

Using these primers and human SIRT5-pBABE-puro and SIRT5-H158Y-pBABE-puro plasmids as templates, perform PCR as described below:

-

Set up following reaction (per tube):

2.5μl of 10X PfuUltra HF Reaction Buffer

1μl of template DNA (50ng)

1μl of 10μM SIRT5 forward primer with Nde1 restriction site

1μl of 10μM SIRT5 reverse primer with Xho1 restriction site

1μl of 10mM dNTP mix

0.5μl of PfuUltra HF DNA Polymerase (2.5U/μl)

18μl of ddH2O

-

Perform amplification reaction in a thermocycler set to the following parameters:

95°C, 3 minutes

95°C, 1 minute

55°C, 1 minute

68°C, 1.5 minutes

Repeat step (ii) to (iv) for 34 times

68°C, 10 minutes

4°C, Hold

-

Verify the PCR fragment size on an 1% agarose gel, and purify the amplified products from the PCR reactions using PCR clean-up/purification kit following manufacturer’s instructions.

Perform restriction digestions of purified PCR products and pET15b with Nde1 and Xho1 restriction enzymes following manufacturer’s instructions (seeNote 3).

Perform Agarose Gel Electrophoresis using restriction enzymes digested PCR products and pET15b. Excise the DNA bands from the gel, and extract DNA from gel pieces using gel extraction kit following manufacturer instructions. Measure the concentrations of extracted DNA using nanodrop spectrophotometer.

-

Set the ligation reactions using restriction enzymes digested and gel extracted pET15b and SIRT5/SIRT5H158Y PCR products in plasmid to insert ratio of 1:3 as follow (seeNote 4):

2μl of 10X DNA Ligase Buffer

50ng of pET15b

22ng of SIRT5/SIRT5HY

1μl of T4 DNA Ligase

ddH2O to a final volume of 20μl

Incubate the ligation reactions at 16°C for 16 hours - overnight.

Transform 10μl of ligation products into chemical competent DH5α bacterial cells by the heat shock method as described in section 3.1, step 7.

Inoculate a few colonies (~6–8) from each plate into separate tubes containing 5ml LB medium with 50μg/ml carbenicillin or 100μg/ml ampicillin. Incubate overnight at 37°C under shaking at 220rpm.

Harvest the cells by centrifugation at 6,500 x g for 5 minutes at room temperature, and purify the plasmid DNA using a miniprep plasmid purification kit following manufacturer’s instructions.

Confirm the cloning of SIRT5 and SIRT5H158Y inserts into pET15b by double restriction digestion and/or PCR amplification.

-

Sequence the entire PCR fragment to confirm that unintended mutations are not present using pET15b sequencing primer:

5′ TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG 3′.

3.3. Bacterial Expression of His Tagged SIRT5 and SIRT5-H158Y proteins

For expression of recombinant His tagged SIRT5 and SIRT5-H158Y proteins in E. coli, transform SIRT5-pET15b and SIRT5-H158Y-pET15b plasmids into chemical competent E. coli BL21 (DE3) by heat shock method as described in section 3.1, step 7.

Pick single colonies from each transformation, and inoculate in 2.5ml of LB medium supplemented with 50μg/ml carbenicillin or 100μg/ml ampicillin. Also inoculate one 2.5ml culture with a colony transformed with the control plasmid pET15b. Inoculate one extra set of cultures to serve as an uninduced control. Grow the cultures at 37°C until OD600 reaches ~0.45–0.5.

Induce the expression of recombinant SIRT5 by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 1mM, and grow the cultures for an additional 6–8 hours. Do not add IPTG to uninduced controls.

Transfer 1ml from all uninduced and induced cultures to separate microcentrifuge tubes. Harvest the cells by centrifugation for 1 minute at 15,000 x g, and discard supernatants.

Resuspend pellets in 25μl of ddH2O, and mix with 25μl of 4X Laemmli sample buffer. Heat the samples at 95–100°C for 10 minutes, and centrifuge at 15,000 x g for 10 minutes.

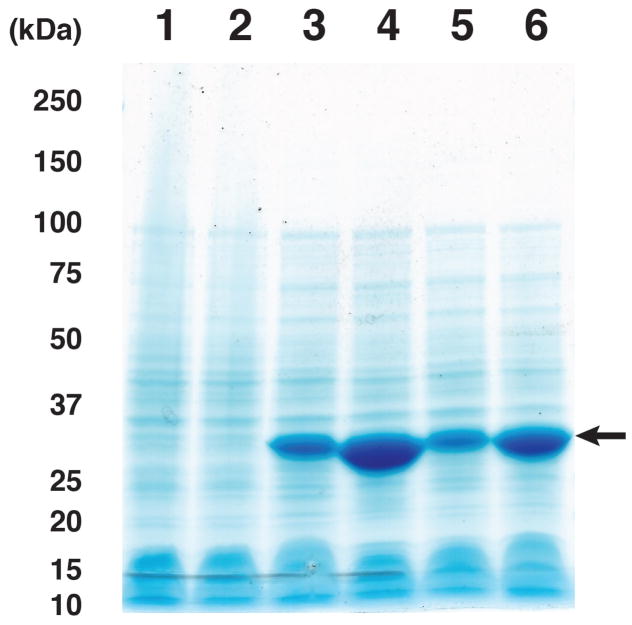

Monitor the expression of recombinant proteins by running 10μl supernatant from each tube from step 5 (i.e., cell lysates from un-induced and IPTG induced cultures) on 4–20% polyacrylamide gel in 1X running buffer at 200V for 1 hour, followed by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. The SDS-PAGE analysis of BL21 (DE3) cells, transformed with recombinant vectors having SIRT5 and SIRT5-H158Y coding sequences, shows over-expression of 32 kDa proteins (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 4 for SIRT5, lanes 5 and 6 for SIRT5-H158Y) corresponding to expected size of SIRT5 and SIRT5-H158Y with a 6X His-tag and a thrombin site (seeNotes 5 and 6).

Figure 1. SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinant SIRT5 and SIRT5H158Y expression.

Expression of SIRT5 (lane 4) and SIRT5H158Y (lane 6) in E. coli following induction with 1mM IPTG at 37°C. Lane 3 and lane 5 show the expression of SIRT5 and SIRT5H158Y respectively, in the absence of IPTG. Lane 1 and lane 2 show the vector control bacterial lysate in the absence and presence of 1mM IPTG, respectively.

3.4. Assessment of solubility of Tagged SIRT5 and SIRT5-H158Y proteins

Inoculate single bacterial colony harboring SIRT5-pET15b or SIRT5-H158Y-pET15b plasmid into 5ml LB medium containing 50μg/ml carbenicillin or 100μg/ml ampicillin, and incubate overnight at 37°C while shaking at 220rpm.

The next day, inoculate 50ml of LB medium containing 50μg/ml carbenicillin or 100μg/ml ampicillin with 2.5ml of the overnight cultures, and incubate at 37°C, with shaking, until the OD600 reaches ~0.5. This will take ~45 minutes.

Transfer 1ml of each culture to separate microcentrifuge tubes. Pellet the cells by centrifugation at 15,000 x g for 1 minute. Resuspend the pellets in 25μl of ddH2O, mix with 25μl of 4X Laemmli sample buffer, and save at −20°C. These will serve as uninduced controls.

Induce the remaining cultures for the expression of recombinant proteins by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 1mM, and grow the cultures for an additional 6–8 hours at 37°C with shaking.

Harvest bacterial cells by centrifugation at 10,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and resuspend cell pellet in 5 ml of lysis buffer for native purification.

Add lysozyme to a final concentration of 1mg/ml, and incubate on ice for 30 minutes (seeNote 7).

Sonicate the cell suspension at 250W with 6–8 bursts of 10 seconds followed by 20 seconds intervals for cooling. Keep samples on ice at all times.

Transfer 10μl of each lysate to separate microcentrifuge tubes, mix with 10μl of 4X Laemmli sample buffer, and freeze at −20°C. These are induced controls.

Centrifuge remaining lysates at 10,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Transfer the supernatants containing soluble proteins to fresh tubes, and keep on ice. Resuspend the pellets into 5ml of lysis buffer to make a suspension of insoluble proteins.

Mix 10μl of soluble protein supernatant with 10μl of 4X Laemmli sample buffer. Similarly mix 10μl suspensions of insoluble proteins with 10μl of 4X Laemmli sample buffer.

Heat these samples along with uninduced, and induced controls, from steps 3 and 8 respectively, at 95–100°C for 10 minutes.

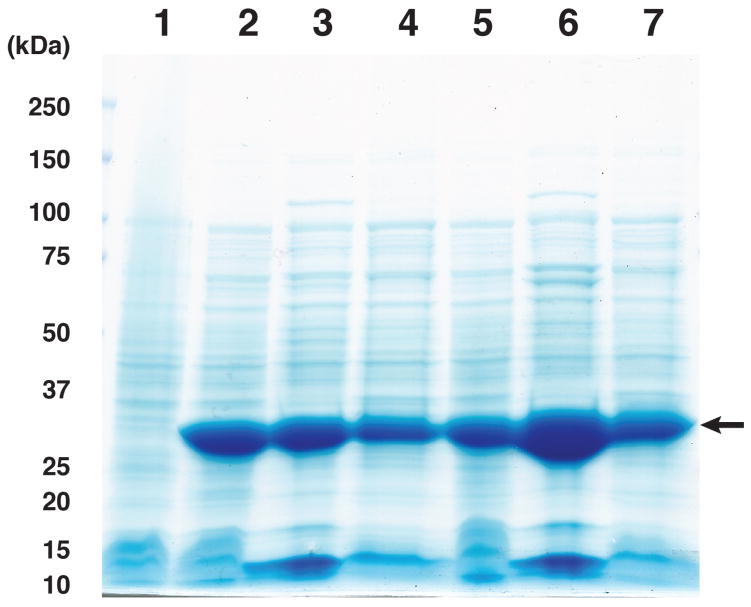

Centrifuge at 15,000 x g for 10 minutes, and run 20μl of the supernatants from the un-induced controls and 10μl from all other samples including vector control on 4–20% polyacrylamide gel followed by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. SDS-PAGE analysis shows that both His-tagged SIRT5 and SIRT5H158Y recombinant proteins corresponding to ~32 kDa are soluble in lysis buffer for native purification (Fig. 2) and can be purified under native conditions (seeNote 8).

Figure 2. SDS-PAGE analysis of SIRT5 and SIRT5H158Y solubility under native conditions.

IPTG induced E. coli cells expressing SIRT5 or SIRT5H158Y were lysed under native conditions and centrifuged. Whole cell lysates (SIRT5; lane 2 and SIRT5H158Y; lane 5), supernatants containing soluble proteins (SIRT5; lanes 3 and SIRT5H158Y; lane 6) and pellets containing insoluble material (SIRT5; lanes 4 and SIRT5H158Y; lane 7) were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lane 1 shows induced E. coli cells harboring empty control vector.

3.5. Purification of His Tagged SIRT5 and SIRT5-H158Y proteins

Grow 5ml each of starter cultures from single bacterial colonies as described above in the section 3.4, step 1.

Inoculate 1L each of LB medium containing 50μg/ml carbenicillin or 100μg/ml ampicillin with 5ml of the starter cultures, and grow at 37°C with shaking at 220rpm, until the OD600 reaches ~0.5.

Induce the expression of recombinant proteins by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 1mM, and grow the cultures for an additional 8 hours.

Harvest bacterial cells expressing recombinant proteins by centrifugation at 10,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Weigh the bacterial cell pellets (seeNote 9).

Resuspend the cell pellets in lysis buffer at 5ml per gram wet weight, and add lysozyme to final concentration of 1 mg/ml. Incubate on ice for 30 minutes (see Note 10).

Sonicate the cell suspension with a sonicator set to 250W with 6–8 bursts of 10 seconds followed by 20 seconds intervals for cooling. Keep samples all time on ice (see Note 11).

Centrifuge lysates at 10,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C to pellet the insoluble fractions and other cellular debris. Supernatants (i.e. cleared lysates), containing the soluble proteins, will be used for purification of His tagged SIRT5 and SIRT5-H158Y proteins in subsequent steps (see Note 8).

Transfer 1ml 50% Ni-NTA slurry per 4ml of cleared lysate to 50ml Falcon tubes, and centrifuge at 700 x g for 2 minutes at 4°C.

Remove and discard the supernatants, and resuspend Ni-NTA pellets in four resin-bed volumes of lysis buffer. Centrifuge again at 700 x g for 2 minutes at 4°C, and carefully remove and discard buffer.

Transfer cleared lysates from step 7 to Ni-NTA pellets from step 9, and mix gently by shaking on a rotary shaker (~200rpm) at 4°C for 45–60 minutes.

Load the lysate–Ni-NTA mixtures into separate columns, and collect the flow-through from each column. If desired, save for SDS-PAGE analysis.

Wash resin twice with four bed volumes of wash buffer, and collect the flow-through for SDS-PAGE analysis, if desired.

Elute His-tagged proteins from the resin with 1ml elution buffer. Repeat this step 8–10 times, collecting each fraction in a separate tube (see Note 12).

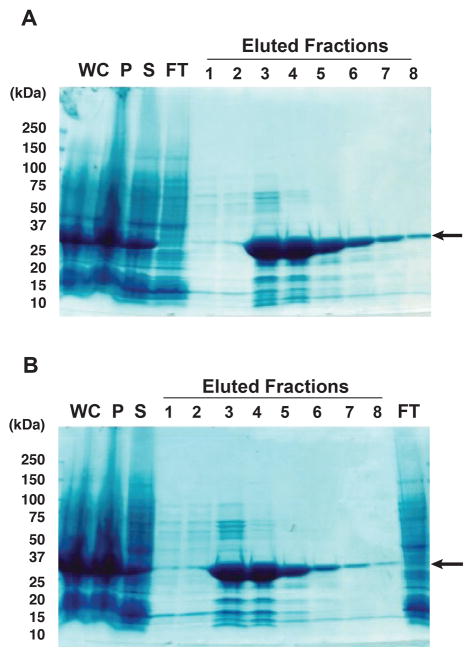

Monitor protein elution by measuring the absorbance of the fractions at 280nm, and fractionate on a 4–20% polyacrylamide gel to directly analyze the purified proteins (Fig. 3).

Measure the concentrations of eluted protein in desired fractions by suitable Protein Assay Kit (see Note 13).

Figure 3. SDS-PAGE analysis of SIRT5 (Panel A) and SIRT5H158Y (Panel B) purified under native conditions.

IPTG-induced E. coli cells expressing SIRT5 and SIRT5H158Y were lysed under native conditions and centrifuged. Whole cell lysates (WC), supernatants containing soluble proteins (S), pellets containing insoluble fractions (P) and eluted protein fractions (1–8, 10μl each) were separated electrophoretically; FT shows the flow through (supernatant following incubation with Ni-NTA) in both panels.

3.6. In Vitro Desuccinylation Assay to Assess the Activity of Purified SIRT5 and SIRT5-H158Y proteins

Mix 0.5ml (~7.5mg) of PDC with 1ml of PDC centrifugation buffer, and centrifuge at 135,000 x g for 2 hours at 4°C (seeNote 14).

Remove supernatant leaving 200μl. Resuspend pellet in residual 200μl of supernatant by pipetting up and down several times.

Measure the concentration of resuspended PDC.

Set up three reaction tubes, each with 30μg of purified porcine heart PDC and 20μl of 3X desuccinylation reaction buffer. In one tube add 10μg of purified SIRT5 protein, and in another add 10μg of purified SIRT5H158Y protein. Do not add any SIRT5 protein to the third (negative control) tube. Bring up the total final reaction volume to 60μl in all three tubes by adding ddH2O. Incubate in water bath set at 37°C for 2 hours with occasional agitation via finger tap (see )Note 15.

-

Analyze samples from each reaction tube by immunoblot using rabbit anti lysine-succinyl antibody as discussed below:

Add 20μl of 4X Laemmli sample buffer to each tube, and heat at 95–100°C for 5 minutes.

Load 20μl of each sample and 8μl of protein standard ladder on a 4–20 % polyacrylamide gel, and run the gel at 200V in 1X running buffer until the dye front reaches to the bottom of the gel.

Transfer the fractionated proteins from polyacrylamide gel to a PVDF membrane in 1X transfer buffer at 800mA for 50 minutes at 4°C.

Visualize the transfer of fractionated proteins on PVDF membrane using Ponceau S staining solution. Make a digital scanned image of the stained membrane.

Block the nonspecific binding sites by incubating the membrane in 5% skim milk in 1X TBST for 30 minutes at room temperature on a rocker.

Discard blocking solution, and wash briefly with 1X TBST.

Incubate overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti lysine-succinyl antibody, diluted @1:1000 in 5% BSA in 1X TBST, while shaking on a rocker.

Collect antibody solution, and wash membrane three times for 10 minutes each with 1X TBST.

Incubate the membrane with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody, diluted at 1:10,000 in 5% skim milk in 1X TBST, for 1 hour at room temperature while shaking on a rocker.

Wash membrane three times for 10 minutes each with 1X TBST.

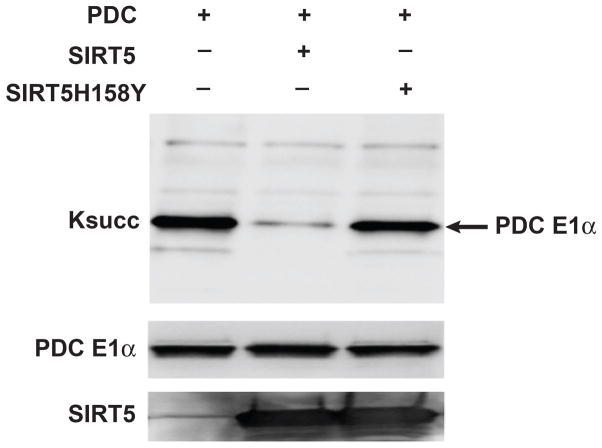

Develop signal using appropriate chemiluminescent HRP Substrate. Figure 4 shows that SIRT5-treated PDC has decreased levels of lysine succinylation on the E1α subunit compared with untreated or SIRT5H158Y treated controls.

Wash membrane with distilled water for 10 minutes at room temperature.

Strip membrane by incubating with stripping buffer while shaking at room temperature for 10 minutes. Discard buffer, and repeat one more time.

Wash membrane twice with 1X PBS for 10 minutes each, followed by two washes with 1X TBST.

Block and re-probe with mouse anti-pyruvate dehydrogenase E1-alpha subunit antibody, diluted @1:1000 in 5% BSA in 1X TBST, as described above in the section 3.6, step 5 (v–vii).

Repeat steps from viii–xi (see Note 16 ).

Figure 4. Desuccinylase activity of purified SIRT5 and SIRT5H158Y.

Pelleted porcine heart PDC was treated with or without purified SIRT5 and SIRT5H158Y proteins and processed for immunoblotting with anti-Ksucc antibody as described in the Methods section. Total PDC E1α serves as loading control.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Lombard laboratory for helpful discussions. Work in our laboratory is supported by the National Institute of Health (R01GM101171, R21CA177925), the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research, and the Discovery Fund of the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center. Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000433. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Natalie German and Dr. Marcia Haigis are gratefully acknowledged for providing the SIRT5 retroviral plasmid.

Footnotes

Human SIRT5-pBABE-puro plasmid was the kind gift of Dr. Marcia Haigis, Department of Cell Biology, Harvard Medical School.

Always use plasmid DNA isolated from dam+ strains of the E. coli. Plasmid DNA isolated from dam strains of E. coli (e.g., JM110 is not suitable) as DpnI, which is used to selectively digest parental plasmid DNA, cleaves only when its recognition site is methylated.

The pET15b plasmid should be sequentially digested.

The plasmid:insert ratio can be increased up to 1:5 if ligation efficiency is poor.

Both SIRT5 and SIRT5H158Y display leaky expression in E. coli BL21 (DE3), which is confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-His antibody. However, we do not observe any toxicity of SIRT5 expression to E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells.

Expression of recombinant proteins can further be confirmed by immunoblotting using anti-His antibody or anti-SIRT5 antibody.

Always use a freshly prepared lysozyme solution.

A significant proportion of SIRT5 and SIRT5H158Y proteins remain insoluble and can be found in the pellet. If desired, these can be purified from insoluble pellet under denaturing purification conditions.

First weigh the empty tubes. Following centrifugation, weigh again tubes containing bacterial pellets. To determine the weight of bacterial pellets, subtract the weights of empty tubes from that of bacterial pellets containing tubes.

To avoid protein degradation during purification, inclusion of protease inhibitors in the lysis buffer is recommended.

If the lysate is very viscous, add RNase A (10μg/ml) and DNase I (5μg/ml), and incubate on ice for 10–15 min.

Ni-NTA resin can be washed with phosphate buffer, and collected for reuse in subsequent purifications.

Eluted fractions should be stored at −70°C.

Always use tubes certified for ultracentrifugation.

3X reaction buffer can be stored at −20°C for 3–4 weeks.

SIRT5-treated material can be used for MS analysis. Also we have found that recombinant SIRT5 is active against target specific peptides (not shown); hence it is suitable for the screening of specific modulators (inhibitors or activators) by high-throughput methodology.

References

- 1.Giblin W, Skinner ME, Lombard DB. Sirtuins: guardians of mammalian healthspan. Trends in genetics : TIG. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar S, Lombard DB. Mitochondrial Sirtuins and Their Relationships with Metabolic Disease and Cancer. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015 doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.6213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman JL, Dittenhafer-Reed KE, Denu JM. Sirtuin catalysis and regulation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:42419–42427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.378877. R112.378877 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frye RA. Phylogenetic classification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic Sir2-like proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:793–798. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3000. S0006-291X(00)93000-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lombard DB, Alt FW, Cheng HL, Bunkenborg J, Streeper RS, Mostoslavsky R, Kim J, Yancopoulos G, Valenzuela D, Murphy A, Yang Y, Chen Y, Hirschey MD, Bronson RT, Haigis M, Guarente LP, Farese RV, Jr, Weissman S, Verdin E, Schwer B. Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT3 regulates global mitochondrial lysine acetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8807–8814. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01636-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bao X, Wang Y, Li X, Li XM, Liu Z, Yang T, Wong CF, Zhang J, Hao Q, Li XD. Identification of ‘erasers’ for lysine crotonylated histone marks using a chemical proteomics approach. eLife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.02999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahuja N, Schwer B, Carobbio S, Waltregny D, North BJ, Castronovo V, Maechler P, Verdin E. Regulation of insulin secretion by SIRT4, a mitochondrial ADP-ribosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33583–33592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haigis MC, Mostoslavsky R, Haigis KM, Fahie K, Christodoulou DC, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Karow M, Blander G, Wolberger C, Prolla TA, Weindruch R, Alt FW, Guarente L. SIRT4 inhibits glutamate dehydrogenase and opposes the effects of calorie restriction in pancreatic beta cells. Cell. 2006;126:941–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laurent G, German NJ, Saha AK, de Boer VC, Davies M, Koves TR, Dephoure N, Fischer F, Boanca G, Vaitheesvaran B, Lovitch SB, Sharpe AH, Kurland IJ, Steegborn C, Gygi SP, Muoio DM, Ruderman NB, Haigis MC. SIRT4 Coordinates the Balance between Lipid Synthesis and Catabolism by Repressing Malonyl CoA Decarboxylase. Mol Cell. 2013;50:686–698. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du J, Zhou Y, Su X, Yu JJ, Khan S, Jiang H, Kim J, Woo J, Kim JH, Choi BH, He B, Chen W, Zhang S, Cerione RA, Auwerx J, Hao Q, Lin H. Sirt5 is a NAD-dependent protein lysine demalonylase and desuccinylase. Science. 2011;334:806–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1207861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park J, Chen Y, Tishkoff DX, Peng C, Tan M, Dai L, Xie Z, Zhang Y, Zwaans BM, Skinner ME, Lombard DB, Zhao Y. SIRT5-mediated lysine desuccinylation impacts diverse metabolic pathways. Mol Cell. 2013;50:919–930. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rardin MJ, He W, Nishida Y, Newman JC, Carrico C, Danielson SR, Guo A, Gut P, Sahu AK, Li B, Uppala R, Fitch M, Riiff T, Zhu L, Zhou J, Mulhern D, Stevens RD, Ilkayeva OR, Newgard CB, Jacobson MP, Hellerstein M, Goetzman ES, Gibson BW, Verdin E. SIRT5 regulates the mitochondrial lysine succinylome and metabolic networks. Cell Metab. 2013;18:920–933. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan M, Peng C, Anderson KA, Chhoy P, Xie Z, Dai L, Park J, Chen Y, Huang H, Zhang Y, Ro J, Wagner GR, Green MF, Madsen AS, Schmiesing J, Peterson BS, Xu G, Ilkayeva OR, Muehlbauer MJ, Braulke T, Muhlhausen C, Backos DS, Olsen CA, McGuire PJ, Pletcher SD, Lombard DB, Hirschey MD, Zhao Y. Lysine glutarylation is a protein posttranslational modification regulated by SIRT5. Cell Metab. 2014;19:605–617. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng C, Lu Z, Xie Z, Cheng Z, Chen Y, Tan M, Luo H, Zhang Y, He W, Yang K, Zwaans BM, Tishkoff D, Ho L, Lombard D, He TC, Dai J, Verdin E, Ye Y, Zhao Y. The first identification of lysine malonylation substrates and its regulatory enzyme. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M111 012658. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakagawa T, Lomb DJ, Haigis MC, Guarente L. SIRT5 Deacetylates carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 and regulates the urea cycle. Cell. 2009;137:560–570. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin ZF, Xu HB, Wang JY, Lin Q, Ruan Z, Liu FB, Jin W, Huang HH, Chen X. SIRT5 desuccinylates and activates SOD1 to eliminate ROS. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;441:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura Y, Ogura M, Ogura K, Tanaka D, Inagaki N. SIRT5 deacetylates and activates urate oxidase in liver mitochondria of mice. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:4076–4081. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel MS, Nemeria NS, Furey W, Jordan F. The Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complexes: Structure-based Function and Regulation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:16615–16623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.563148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozden O, Park SH, Wagner BA, Song HY, Zhu Y, Vassilopoulos A, Jung B, Buettner GR, Gius D. Sirt3 Deacetylates and Increases Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Activity in Cancer Cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zwaans BM, Lombard DB. Interplay between sirtuins, MYC and hypoxia-inducible factor in cancer-associated metabolic reprogramming. Dis Model Mech. 2014;7:1023–1032. doi: 10.1242/dmm.016287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu W, Zuo Y, Feng Y, Zhang M. SIRT5 facilitates cancer cell growth and drug resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michishita E, Park JY, Burneskis JM, Barrett JC, Horikawa I. Evolutionarily conserved and nonconserved cellular localizations and functions of human SIRT proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4623–4635. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0033. E05-01-0033 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu J, Sadhukhan S, Noriega LG, Moullan N, He B, Weiss RS, Lin H, Schoonjans K, Auwerx J. Metabolic characterization of a Sirt5 deficient mouse model. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2806. doi: 10.1038/srep02806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahlknecht U, Ho AD, Letzel S, Voelter-Mahlknecht S. Assignment of the NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin 5 gene (SIRT5) to human chromosome band 6p23 by in situ hybridization. Cytogenetic and genome research. 2006;112:208–212. doi: 10.1159/000089872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsushita N, Yonashiro R, Ogata Y, Sugiura A, Nagashima S, Fukuda T, Inatome R, Yanagi S. Distinct regulation of mitochondrial localization and stability of two human Sirt5 isoforms. Genes to cells : devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms. 2011;16:190–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gertz M, Steegborn C. Function and regulation of the mitochondrial sirtuin isoform Sirt5 in Mammalia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:1658–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakagawa T, Guarente L. Urea cycle regulation by mitochondrial sirtuin, SIRT5. Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1:578–581. doi: 10.18632/aging.100062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]