Abstract

Background

Population-based data on melanoma survival are important for understanding the impact of demographic and clinical factors on prognosis.

Objective

We describe melanoma survival by age, sex, race/ethnicity, stage, depth, histology, and site.

Methods

Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data, we calculated unadjusted cause-specific survival up to 10 years from diagnosis for 68,495 first primary cases of melanoma diagnosed from 1992 to 2005. Cox multivariate analysis was performed for 5-year survival. Data from 1992 to 2001 were divided into 3 time periods to compare stage distribution and differences in stage-specific 5-year survival over time.

Results

Melanomas that had metastasized (distant stage) or were thicker than 4.00 mm had a poor prognosis (5-year survival: 15.7% and 56.6%). The 5-year survival for men was 86.8% and for persons given the diagnosis at age 65 years or older was 83.2%, varying by stage at diagnosis. Scalp/neck melanoma had lower 5-year survival (82.6%) than other anatomic sites; unspecified/overlapping lesions had the least favorable prognosis (41.5%). Nodular and acral lentiginous melanomas had the poorest 5-year survival among histologic subtypes (69.4% and 81.2%, respectively). Survival differences by race/ethnicity were observed in the unadjusted survival, but nonsignificant in the multivariate analysis. Overall 5-year melanoma survival increased from 87.7% to 90.1% for melanomas diagnosed in 1992 through 1995 compared with 1999 through 2001, and this change was not clearly associated with a shift toward localized diagnosis.

Limitations

Prognostic factors included in revised melanoma staging guidelines were not available for all study years and were not examined.

Conclusions

Poorer survival from melanoma was observed among those given the diagnosis at late stage and older age. Improvements in survival over time have been minimal. Although newly available therapies may impact survival, prevention and early detection are relevant to melanoma-specific survival.

Keywords: anatomic sites, cancer registry, histology, melanoma, survival

More than 50,000 people are given the diagnosis of melanoma in the United States every year, according to the US Cancer Statistics report.1 In addition to the stage at diagnosis, previous studies have shown other factors are related to prognosis such as histology, location on body, and socioeconomic status (SES).2-5 In this study, we used the data from population-based cancer registries to describe melanoma survival by demographic and clinical factors.

METHODS

We analyzed data from the 13 registries that participate in the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program (Atlanta, GA; Connecticut; Detroit, MI; Hawaii; Iowa; New Mexico; San Francisco-Oakland, CA; Seattle-Puget Sound, WA; Utah; Los Angeles, CA; San Jose-Monterey, CA; rural Georgia; and the Alaska Native Tumor Registry). The coverage of these SEER-13 registries represented 14% of the US population and met uniform data standards for cancer registration.6

We identified 133,386 cases of melanoma diagnosed between 1992 and 2005 at age 15 years or older and reported to a SEER-13 registry. We excluded 37,160 in situ melanoma cases (27.9%); 26,282 melanoma cases that were not the first cancer diagnosed (19.7%); 145 cases found by death certificate only or autopsy; 275 cases not microscopically confirmed; 318 cases with an unknown cause of death; 88 patients with unknown age; and 623 patients who had no survival time. Our final study population included 68,495 first primary invasive melanoma cases diagnosed in years 1992 to 2005 and followed up through 2006 to ensure at least 12 months of complete follow-up. Melanoma cases were identified by International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition morphology codes (C440-C449)7 and categorized by histologic subtype as superficial spreading, lentigo maligna, acral lentiginous, nodular, not otherwise specified, and other.8 We chose not to collapse the histologic category “not otherwise specified” with “other” because the survival patterns for these two subtypes were different. A revised staging system for melanoma was introduced in the sixth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual and implemented into cancer registries in 2003.9 To ensure consistency in staging across all study years, we used SEER historic stage, which provides consistent definitions over time (as opposed to AJCC staging, which is more commonly used in the clinical settings).10 SEER historic stages were localized (confined to primary site), regional (spread to regional lymph nodes), distant (cancer had metastasized), and unknown (unstaged). Depth of melanoma was classified as less than or equal to 1 mm, 1.01 to 2.00 mm, 2.01 to 4.00 mm, and greater than 4.00 mm. Anatomic sites were classified as face/ears (C440-C443), scalp and neck (C444), trunk (C445), extremities (C446-447), and not otherwise specified/overlapping codes (C448-C449).7 Scalp and neck melanomas have been shown to have poorer survival than melanomas on the face, ear, and other anatomic sites,3 thus we analyzed them separately. Information on race and ethnicity was obtained from medical records by tumor registrars who reported melanoma to the SEER program.6 Identification of cases having Hispanic ethnicity was enhanced with the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries Hispanic Identification Algorithm.11 The availability and quality of variables on receipt of surgery, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), and radiation were limited, especially in the earlier years, and therefore not included in this analysis.

Analysis

Our main outcome of interest was survival time after a diagnosis of melanoma as the primary cancer. The cause of death information was from death certificates. We present cause-specific survival (eg, melanoma-specific survival [MSS]). For the unadjusted analyses, we used the Kaplan-Meier method to calculate MSS by gender, age at diagnosis, race, Hispanic ethnicity, stage and depth at diagnosis, anatomic site, and histologic subtype. To examine temporal trends in survival, we stratified cases into 3 time periods (1992-1995, 1996-1998, and 1999-2001). For this analysis of survival time by time period and stage, we excluded cases diagnosed after 2001 to have a full 5 years of follow-up. We used the Z-test to examine any differences in 5-year survival between the earliest and most recent time period and χ2 to test for any significant change in the proportion of cases diagnosed at the local, regional, distant, and unknown stage (eg, stage distribution).

We explored whether survival differences can be explained by sociodemographic and clinical characteristics by performing a multivariate analysis for MSS using Cox regression modeling. Because of missing information on race/ethnicity, stage at diagnosis, and depth, this multivariate analysis was based on 56,886 study cases. We restricted the follow-up time in the Cox model to a 5-year follow-up period. We assessed the Cox proportional hazards assumption for each covariate by graphical examination of the log of the negative log survival curves versus time and by the Schoenfeld residual correlation test. Variables for histologic subtype and anatomic site were both found to violate the Cox proportional hazards assumption. Thus, the final Cox model was stratified on histologic subtype and anatomic site and included sex, age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, stage at diagnosis, and depth.12,13 Hazard ratios (HR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated to determine statistical significance. All the analyses were performed using SEER*Stat, Version 6.6 (IMS Inc, Silver Springs, MD) and SAS, Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

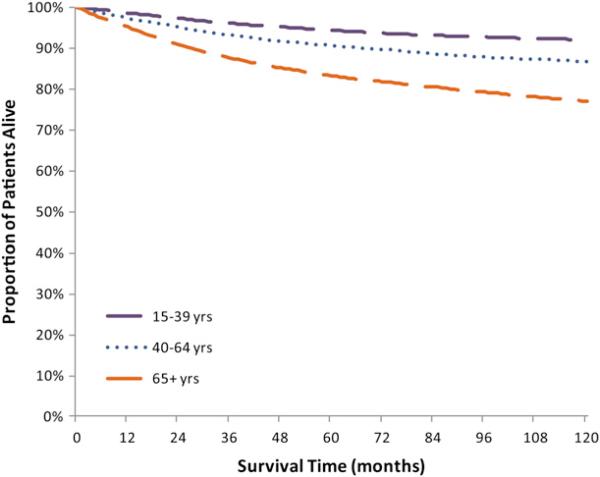

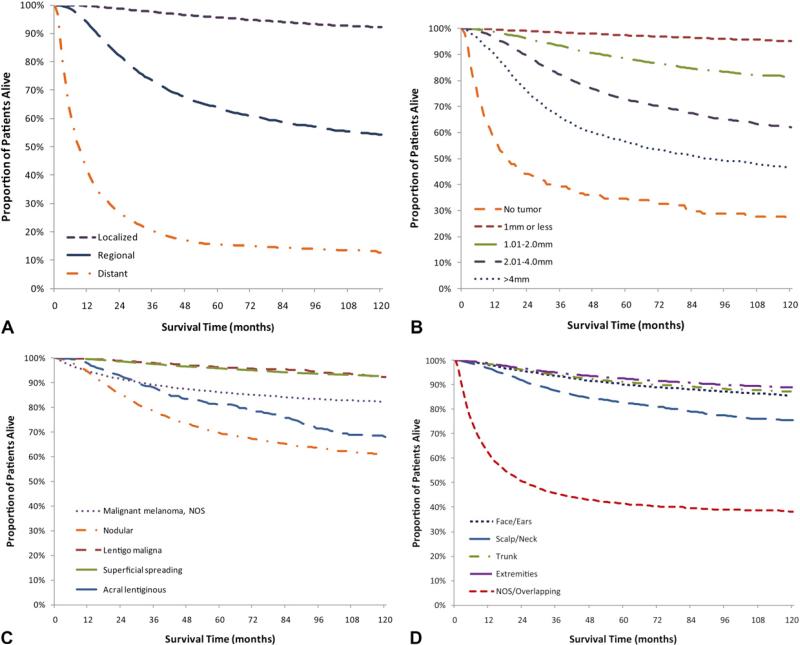

This study included 68,495 invasive melanoma cases diagnosed from 1992 to 2005 in the 13 SEER registries. Table I shows the distribution of melanoma incidence by demographic and clinical characteristics and 1-, 5-, and 10-year MSS. Figs 1 and 2 show Kaplan-Meier cause-specific survival curves. Overall, the 1-year MSS was 96.9%. The 5- and 10-year MSS were 89.2% and 85.1%. The MSS for males and females was 96.3% and 97.7% at year 1 and 86.8% and 92.0% at year 5, respectively. Age at diagnosis impacted survival. Men and women given the diagnosis at age 65 years and older had a lower 5-year survival than those at age 40 to 64 years and 15-39 years (83.2% vs 90.6% and 94.4%) (Table I). As time from diagnosis increased, so did the differences between the MSS of the oldest and younger age groups (Fig 1). The 10-year MSS was 77.0% for cases diagnosed at age 65 years, which was lower than 86.7% and 91.9% for the two younger age categories. We analyzed MSS by age and stage at diagnosis and found that the difference between the youngest (15-39 years) and oldest (≥ 65 years) age group was more pronounced for regional stage melanomas (73.5% vs 58.2%) than localized stage (98.0% vs 92.3%) (data not shown). Whites accounted for 95.2% of the study population and had a favorable prognosis at diagnosis (96.9% 1-year and 89.0% 5-year MSS) compared with blacks (72.2% 5-year MSS) and Asian/Pacific Islanders (79.2% 5-year MSS). Ethnicity also impacted survival. Non-Hispanic whites had a higher 5-year survival than Hispanic whites (89.2% vs 82.9%). Melanoma diagnosed at the localized stage had a 99.7% 1-year MSS, but despite early detection there were still deaths attributable to melanoma at the localized stage (10-year MSS 92.1%). In contrast, diagnoses at a distant stage had poor prognoses (1-year MSS 41.3%). For regional and distant stage melanomas, MSS decreased rapidly from year 1 to year 3 and then stabilized from year 5 to year 10 (Fig 2, A). Given that depth of melanoma is a major determinant of stage of diagnosis, as expected, lesions less than 1.00 mm had a 5-year MSS of 97.4% whereas the 5-year MSS for lesions that were 2.01 to 4.00 mm was 72.7% and, for lesions with a depth greater than 4.00 mm, MSS was 56.6% (Fig 2, B). Two histologic subtypes with favorable prognosis were superficial spreading and lentigo maligna. For both, MSS exceeded 99% at year 1, 95% MSS at year 5, and remain over 92% at year 10 (Fig 2, C). In contrast, the 1-, 5-, and 10-year MSS of nodular and acral lentiginous melanoma were substantially different. Survival by anatomic site was similar for melanoma diagnosed on the face/ears, trunk, and extremities (5-year MSS 90.2%, 91.2%, 92.5%) but less for melanoma on the scalp and neck (5-year MSS 82.6%, 10-year MSS 75.6%) and unspecified and overlapping lesions (5-year MSS 41.5%) (Fig 2, D).

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with invasive melanoma, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-13, 1992 to 2005

| Melanoma-specific survival, % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No. | Percentage | 1-y | 5-y | 10-y |

| Overall | 68,495 | 96.9 | 89.2 | 85.1 | |

| Sociodemographic | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 37,626 | 54.9 | 96.3 | 86.8 | 82.0 |

| Female | 30,869 | 45.1 | 97.7 | 92.0 | 88.8 |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |||||

| 15-39 | 13,383 | 19.5 | 98.6 | 94.4 | 91.9 |

| 40-64 | 33,526 | 48.9 | 97.4 | 90.6 | 86.7 |

| ≥ 65 | 21,586 | 31.5 | 95.1 | 83.2 | 77.0 |

| Race/ethnicity* | |||||

| White | 65,174 | 95.2 | 96.9 | 89.0 | 84.8 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 63,140 | 92.2 | 96.9 | 89.2 | 85.0 |

| White, Hispanic | 2034 | 3.0 | 95.1 | 82.9 | 79.0 |

| Black | 318 | 0.5 | 89.5 | 72.2 | 68.2 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 593 | 0.9 | 94.4 | 79.2 | 71.7 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 124 | 0.2 | 93.5 | 79.5 | 74.6 |

| Other/unknown | 2286 | 3.3 | 99.8 | 99.2 | 98.0 |

| Hispanic | 2104 | 3.1 | 95.3 | 83.3 | 79.5 |

| Clinical | |||||

| Stage at diagnosis | |||||

| Localized | 56,504 | 82.5 | 99.7 | 95.6 | 92.1 |

| Regional | 7365 | 10.8 | 93.6 | 63.7 | 54.3 |

| Distant | 2253 | 3.3 | 41.3 | 15.7 | 12.8 |

| Unstaged | 2373 | 3.5 | 93.4 | 80.3 | 74.2 |

| Depth, mm | |||||

| No mass/tumor found | 483 | 0.7 | 57.4 | 34.5 | 26.4 |

| 0.01-1.00 | 40,935 | 59.8 | 99.6 | 97.4 | 95.2 |

| 1.01-2.00 | 9520 | 13.9 | 98.7 | 88.4 | 81.2 |

| 2.01-4.00 | 5190 | 7.6 | 96.5 | 72.7 | 62.1 |

| >4.00 | 2955 | 4.3 | 91.1 | 56.6 | 46.6 |

| Unknown | 9412 | 13.7 | 87.4 | 75.4 | 71.2 |

| Histologic subtype | |||||

| Superficial spreading | 26,054 | 38.0 | 99.5 | 95.8 | 92.6 |

| Lentigo maligna | 4297 | 6.3 | 99.7 | 96.3 | 92.4 |

| Acral lentiginous | 785 | 1.1 | 97.7 | 81.2 | 67.9 |

| Nodular | 4998 | 7.3 | 94.3 | 69.4 | 60.8 |

| NOS | 29,445 | 43.0 | 94.7 | 86.2 | 82.2 |

| Others | 2916 | 4.3 | 96.2 | 83.4 | 78.1 |

| Anatomic site | |||||

| Face/ears | 8153 | 11.9 | 98.4 | 90.2 | 85.5 |

| Scalp/neck | 4328 | 6.3 | 96.6 | 82.6 | 75.6 |

| Trunk | 23,293 | 34.0 | 98.3 | 91.2 | 87.1 |

| Extremities | 29,990 | 43.8 | 98.7 | 92.5 | 88.8 |

| Upper limb/shoulder | 16,229 | 23.7 | 98.7 | 93.0 | 89.5 |

| Lower limb/hip | 13,761 | 20.1 | 98.6 | 91.8 | 88.0 |

| NOS/overlapping | 2731 | 4.0 | 61.7 | 41.5 | 38.2 |

NOS, not otherwise specified.

Hispanics were not mutually exclusive from race. Whites included both non-Hispanic whites and Hispanic whites.

Fig 1.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier melanoma-specific survival curve by age at diagnosis, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-13, 1992 to 2005.

Fig 2.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier melanoma-specific survival curves by stage (A), depth (B), histology (C), and anatomic site (D), Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-13, 1992 to 2005. NOS, Not otherwise specified.

A modest increase in the overall 5-year cause-specific survival for melanoma was observed between the time periods of 1992 to 1995 (87.7% [95% CI 87.1-88.2]) and 1999 to 2001 (90.1% [95% CI 89.6-90.5]) (Table II). Comparing these two time periods, there was a decrease in the proportion of unstaged cases from 5.9% to 2.1% of overall cases (P < .001). Among the cases that were staged, compared with cases diagnosed in 1992 through 1995, the proportion of localized cases decreased in the most recent time period of 1999 to 2001, whereas the proportion of cases diagnosed at the regional stage increased, and the change in proportion diagnosed at the distant stage was very small (P<.001 for overall change in distribution). Patients given the diagnosis at the localized and regional stages from 1999 to 2001 had significantly increased 5-year survival compared with patients given the diagnosis of same-stage cancer from 1992 to 1995. For melanoma diagnosed at a distant stage, there was a slight, but not significant, increase in 5-year MSS from the earliest to latest diagnostic time period.

Table II.

Overall melanoma-specific 5-year survival by specified time periods, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-13, 1992 to 2005

| Period I | Period II | Period III | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992-1995 | 1996-1998 | 1999-2001 | ||||

| N (%) | 5-y Survival, % (95% CI) | N (%) | 5-y Survival, % (95% CI) | N (%) | 5-y Survival, % (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 16,262 | 87.7 (87.1-88.2) | 14,286 | 89.1 (88.5-89.6) | 15,604 | 90.1 (89.6-90.5) |

| Staged | 15,304 (94.1) | 88.1 (87.5-88.6) | 13,647 (95.5) | 88.1 (87.5-88.6) | 15,272 (97.9) | 90.3 (89.8-90.7) |

| Unstaged | 958 (5.9) | 80.9 (78.2-83.3) | 639 (4.5) | 80.0 (76.6-83.0) | 332 (2.1) | 79.6 (74.6-83.7) |

| Staged | ||||||

| Localized | 13,223 (86.4) | 94.3 (93.8-94.6) | 11,726 (85.9) | 95.6 (95.2-96.0) | 12,922 (84.6) | 96.4 (96.1-96.7) |

| Regional | 1518 (9.9) | 59.4 (56.8-62.0) | 1468 (10.8) | 61.3 (56.8-63.8) | 1869 (12.2) | 65.5 (63.2-67.7) |

| Distant | 563 (3.7) | 14.0 (11.1-17.2) | 453 (3.3) | 16.4 (13.0-20.2) | 481 (3.2) | 16.6 (13.0-20.2) |

Cases diagnosed after 2001 were excluded to have a full 5 years of follow-up. Percentages may not add to 100 because of rounding.

CI, Confidence interval.

After controlling for demographic and clinical factors through multivariate analysis, we found sex and age remained significantly associated with 5-year survival (Table III). The risk of death for females was lower than for males (HR 0.76 [0.71-0.81]), as were the two younger age groupings (HR 0.66 [0.62-0.71] for ages 40-64 years and HR 0.49 [0.44-0.54] for ages 15-39 years) compared with those older than 65 years. Racial/ethnic differences in survival were attenuated in our multivariate model. The risk of melanoma death for blacks was over one-third higher than for non-Hispanic whites, but did not reach statistical significance (HR 1.33 [0.98-1.78]). The survival differences by Hispanic ethnicity (limited to cases of white race) also lost significance in the multivariate analysis (HR 1.06 [0.92-1.24]). We found the stage at diagnosis and depth of melanoma to be important factors related to 5-year survival.

Table III.

Cox multivariate analysis of 5-year survival for malignant melanoma, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-13, 1992 to 2005

| Characteristic | Hazard ratio* (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | Ref. |

| Female | 0.76 (0.71-0.81) |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |

| ≥ 65 | Ref. |

| 40-64 | 0.66 (0.62-0.71) |

| 15-39 | 0.49 (0.44-0.54) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | |

| Non-Hispanic | Ref. |

| Hispanic | 1.06 (0.92-1.24) |

| Black | 1.33 (0.98-1.78) |

| Asian Pacific Islander/American | 0.98 (0.76-1.25) |

| Indian Alaskan Native | |

| Stage at diagnosis† | |

| Localized | Ref. |

| Regional | 3.62 (3.35-3.91) |

| Distant | 18.66 (16.54-21.06) |

| Depth, mm | |

| ≤ 1 | Ref. |

| 1.01-2.0 | 2.89 (2.62-3.18) |

| 2.01-4.0 | 4.69 (4.24-5.02) |

| >4.0 | 5.71 (5.10-6.39) |

| No tumor found | 3.03 (1.98-4.64) |

CI, Confidence interval.

Survival estimates are from Cox proportional hazards model accounting for histologic subtype, anatomic site, sex, age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, stage at diagnosis, and depth.

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) historic stage based on SEER summary stage 2000.

DISCUSSION

Our study results are consistent with earlier reports that stage at diagnosis and depth are significant factors related to MSS.9 Although depth is one factor that determines stage, the correlation between them was modest (21%), therefore, we kept both depth and stage in the model. Sex and age also remained significant prognostic factors in the adjusted analysis, with worse survival for men and those who were elderly at diagnosis. The difference in survival by age may be related to comorbidities, which could not be directly accounted using SEER data. Although we observed survival differences by race and ethnicity (for whites) in the unadjusted analysis, the association of race and ethnicity with survival was attenuated in the multivariate analysis.

Gender difference in melanoma survival have been reported in other studies.9,14-16 Although this observation is not well understood, previously published findings have suggested that older patients are given the diagnosis at later stages as a result of less screening; men are given the diagnosis of more nodular melanoma, which has a poorer prognosis; and that women undergo more screening and have melanomas in more favorable anatomic locations.10,15,17,18 Our multivariate analysis results showed that even adjusting for stage, the risk of death from melanoma was still higher for men than for women. Regarding race, the adjusted risk of death for blacks was higher than for non-Hispanic whites, but not statistically significant. This observation supports that there are racial differences in sex, age, and clinical factors of melanoma at diagnosis, which in turn impact survival. Previous studies have shown that blacks are disproportionately affected by acral lentiginous melanoma, a histologic subtype with worse survival than overall melanoma, likely because of acral lentiginous melanoma being diagnosed at later stages with thicker lesions.2,19 After accounting for stage, depth, and histologic subtype, we found survival differences for blacks compared with whites were less than in previously published work by Zell et al.5 Two major differences, however, were that the analysis of Zell et al5 used only California Cancer Registry data with 127 cases of melanoma among blacks, whereas our study used national SEER-13 data that included over twice the number of blacks; and, unlike the analysis of Zell et al,5 we did not adjust for SES and treatment. SES has been related to melanoma survival with increased survival for nonwhites and elderly persons with higher SES.4,5

We observed small improvements in survival at the localized and regional stage. A factor that could explain these observations and may have contributed to an increase in survival at these earlier stages is the adoption of SLNB around the year 2000, a technique that more precisely identifies potentially affected lymph nodes.20 Using SLNB, some melanoma cases that may have been classified as localized are identified as regional because of the increased specificity of the diagnostic workup. As a result of this upstaging, the survival at the regional disease improves because of the addition of cases that would have otherwise been classified as localized, and survival at the localized stage also improves because of the identification and classification of more disseminated disease as regional stage.9,21 The impact of SLNB on overall survival is a topic of much debate in the current literature because the early removal of lymph nodes with micrometastatic disease has not been shown to improve overall survival, and there have been no randomized trials that have shown that early surgical removal of affected nodes improves overall survival compared with delaying removal of nodes until they are clinically palpable.22,23

We showed a small improvement in overall 5-year survival from the early 1990s to the period around the year 2000. During this time we found that more cases were being staged; however, we did not observe a dramatic shift toward melanoma being diagnosed at earlier stages as might be expected from increased screening for melanoma. In fact, among the melanoma cases that were staged, from the earliest to most recent time period, the percentage of all melanomas diagnosed at the localized stage decreased and the percentage of all melanomas diagnosed at the regional stage increased. Jemal et al24 showed that the incidence rates from 1992 to 2006 increased for all tumor depths, but did not take into account nodal involvement, metastasis, or other criteria that determine stage. Further exploration of how the revised staging systems impact the relative percentages of melanoma diagnosed at the localized versus regional stage warrants further study.

Our cause-specific analysis focused on melanoma as the underlying cause of death and did not include death from all other causes. The validity of MSS depends on the quality of recorded cause of death.21 Understanding this, we believed that using MSS was justified for our study because of the high quality of SEER data, and because ascertaining death from melanoma is not as challenging as other diseases as a result of ease of obtaining diagnosis through biopsy, and because of the tendency of disseminated disease to metastasize and be detected. Another approach we could have used is “relative survival,” which compares the observed survival of those given the diagnosis of melanoma with a comparable population without melanoma, thus bypassing the need for cause for death because of the focus on excess mortality among those with melanoma.21 We chose not to show relative survival because our preliminary analyses using both cause-specific and relative survival were similar (data not shown) and because there were no life tables available for racial and ethnic groups besides black and white. “Period survival” is an approach that captures improvements in survival to provide better estimates of long-term survival for more recently diagnosed cancer.25 Given the lack of significant progress in survival shown in our study (Table II), using period survival was unnecessary. A more recent, relevant approach is “conditional survival,” which conditions survival upon living to a certain time point, and has been applied to melanoma by Rueth et al26 to show that 8 years after surgical treatment from melanoma, the survival for high-risk melanoma is similar to low-risk disease.

Strengths of this study were the use of population-based, high-quality SEER data and the large number of melanoma cases, including cases among those who were black or Hispanic. A limitation is that we were unable to use the complete US Cancer Statistics data set (SEER combined with National Program of Cancer Registries data)1 because the survival data are not consistently available from all National Program of Cancer Registries. Other limitations include the use of the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries Hispanic Identification Algorithm, which may misclassify Hispanic ethnicity because of the reliance of surname and other demographic variables rather than self-report.11 We did not account for all factors known to impact survival including treatment, prognostic factors in the revised staging system (nodal involvement, metastasis, and, more recently, mitoses, ulceration, and serum lactate dehydrogenase), SES, and physician specialty or availability as these data are not available in population-based registries.4,5,14,27,28 Also, we examined survival after diagnosis of the “first and primary” melanoma but did not limit cases to “first and only” melanoma. Thus, our data include people who may have had subsequent cancers, melanoma or otherwise, after a primary diagnosis of melanoma. It is important to be aware that certain medical conditions, such as atypical mole (dysplastic nevi) syndrome or immunosuppression, may predispose one to multiple diagnoses of melanoma and may impact survival.29-35

The contrast in melanoma survival by stage at diagnosis offers a compelling reason to support early detection and to support primary prevention through sun protection and avoidance of harmful ultraviolet light; these prevention efforts should be emphasized. Although, routine screening for early detection of lesions is not currently recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force and Cancer Council Australia,36-38 early detection through screening should be considered for persons at risk for melanoma. Previous studies have found such screening program to be cost-effective, even if screening is not currently recommended. For instance, Freedberg et al39 used data from the US population and estimated a cost-effectiveness ratio of $29,170 per year of life saved for a one-time screening of self-selected patients at high-risk with a mean age of 48 years. Further, a study from Australia estimated a cost-effectiveness of annual melanoma screening in Australians aged 50 years or older to be Aust. $12,137 and Aust. $20,877 (US$12,318 and US$21,188) for men and women, respectively.40

In conclusion, our study found minimal progress in survival from 1992 to 2005. The relevance of new therapies such as interferon alfa-2b and, more recently, immunotherapy (eg, ipilimumab) on prognosis will be determined in future studies.20,41 Until then, efforts to reduce melanoma deaths must continue through prevention, screening of persons at high risk, and elimination of disparities that lead to late diagnosis.

CAPSULE SUMMARY.

Cancer registry data were used to calculate cause-specific survival up to 10 years from diagnosis for 68,495 first primary cases of melanoma diagnosed from 1992 to 2005.

Poorer survival from melanoma was observed among those given the diagnosis at late stage and older age.

Improvements in survival over time have been minimal.

Abbreviations used

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

hazard ratio

- MSS

melanoma-specific survival

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- SES

socioeconomic status

- SLNB

sentinel lymph node biopsy

Footnotes

Publication of this supplement to the JAAD was supported by the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

The opinions or views expressed in this supplement are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions, recommendations, or official position of the journal editors or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Cancer Statistics Working Group . United States cancer statistics: 1999-2006 incidence and mortality Web-based report. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; Atlanta: 2010. [October 1, 2010]. Available from: URL: www.cdc.gov/uscs. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford PT, Goldstein AM, McMaster ML, Tucker MA. Acral lentiginous melanoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1986-2005. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:427–34. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lachiewicz AM, Berwick M, Wiggins CL, Thomas NE. Survival differences between patients with scalp or neck melanoma and those with melanoma of other sites in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:515–21. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reyes-Ortiz CA, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL, Kuo YF. Socioeconomic status and survival in older patients with melanoma. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1758–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zell JA, Cinar P, Mobasher M, Ziogas A, Meyskens FL, Jr, Anton-Culver H. Survival for patients with invasive cutaneous melanoma among ethnic groups: the effects of socioeconomic status and treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:66–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Havener LA, Thornton ML, editors. Standard for cancer registries. Vol 2. Data standards and data dictionary. 13th ed. Version 11.3. North American Association of Central Cancer Registries; Springfield (IL): 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Firtz A, Percy C, Jack A, Shanmungaratnam K, Sobin L, Parkin DM, et al. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson M, Johnson CJ, Chen VW, Thomas CC, Weir HK, Sherman R, et al. Melanoma surveillance in the United States: overview of methods. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:S6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balch CM, Soong SJ, Atkins MB, Buzaid AC, Cascinelli N, Coit DG, et al. An evidence-based staging system for cutaneous melanoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:131–49. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.3.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Cancer Institute [October 13, 2010];SEER stat fact sheets: melanoma of the skin. Bethesda (MD) Available from: URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html.

- 11.NAACCR Latino Research Work Group . NAACCR Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander identification algorithm. North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR); Springfield (IL): 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allison PD. Survival analysis using the SAS system: a practical guide. SAS Institute Inc; Cary (NC): 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collet D. Modeling survival data in medical research. Chapman and Hall; London: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pennie ML, Soon SL, Risser JB, Veledar E, Culler SD, Chen SC. Melanoma outcomes for Medicare patients: association of stage and survival with detection by a dermatologist vs a nondermatologist. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:488–94. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swetter SM, Geller AC, Kirkwood JM. Melanoma in the older person. Oncology (Williston Park) 2004;18:1187–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cockburn M. Melanoma. In: Ries LAG, Young JL, Keel GE, et al., editors. SEER survival monograph: cancer survival among adults; US SEER Program, 1988-2001, patient and tumor characteristics. National Cancer Institute, SEER Program; Bethesda (MD): 2007. pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reyes Ortiz CA, Freeman JL, Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. The influence of marital status on stage at diagnosis and survival of older persons with melanoma. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:892–8. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.8.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Durme DJ, Ferrante JM, Pal N, Wathington D, Roetzheim RG, Gonzalez EC. Demographic predictors of melanoma stage at diagnosis. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:606–11. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.7.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu X-C, Eide MJ, King J, Saraiya M, Huang Y, Wiggins C, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:S26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubois RW, Swetter SM, Atkins M, et al. Developing indications for the use of sentinel lymph node biopsy and adjuvant high-dose interferon alfa-2b in melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1217–24. doi: 10.1001/archderm.137.9.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickman PW, Adami HO. Interpreting trends in cancer patient survival. J Intern Med. 2006;260:103–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, Mozzillo N, Elashoff R, Essner R, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1307–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stebbens WG, Garibyan L, Sober AJ. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and melanoma: 2010 update part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:737–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.11.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jemal A, Saraiya M, Patel P, Cherala SS, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Kim J, et al. Recent trends in cutaneous melanoma incidence and death rates in the United States, 1992-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:S17–25. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenner H, Hakulinen T. Up-to-date cancer survival: period analysis and beyond. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1384–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rueth NM, Groth SS, Tuttle TM, Virnig BA, Al-Refaie WB, Habermann EB. Conditional survival after surgical treatment of melanoma: an analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1662–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0965-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eide MJ, Weinstock MA, Clark MA. Demographic and socioeconomic predictors of melanoma prognosis in the United States. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20:227–45. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eide MJ, Weinstock MA, Clark MA. The association of physician-specialty density and melanoma prognosis in the United States, 1988 to 1993. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauer J, Garbe C. Acquired melanocytic nevi as risk factor for melanoma development: a comprehensive review of epidemiological data. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:297–306. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tiersten AD, Grin CM, Kopf AW, et al. Prospective follow-up for malignant melanoma in patients with atypical-mole (dysplastic-nevus) syndrome. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991;17:44–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1991.tb01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tucker MA, Halpern A, Holly EA, et al. Clinically recognized dysplastic nevi: a central risk factor for cutaneous melanoma. JAMA. 1997;277:1439–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma, I: common and atypical nevi. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:28–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vajdic CM, van Leeuwen MT, Webster AC, et al. Cutaneous melanoma is related to immune suppression in kidney transplant recipients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2297–303. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hollenbeak CS, Todd MM, Billingsley EM, Harper G, Dyer AM, Lengerich EJ. Increased incidence of melanoma in renal transplantation recipients. Cancer. 2005;104:1962–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le ML, Hollowood K, Gray D, Bordea C, Wojnarowska F. Melanomas in renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:472–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolff T, Tai E, Miller T. Screening for skin cancer: an update of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:194–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:188–93. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cancer Council Australia . Position statement: Screening and early detection of skin cancer. Cancer Council Australia; Sydney: 2007. [October 1, 2010]. Available from: URL: http://www.cancer.org.au/File/PolicyPublications/Position_statements/PS-Screening_and_early_detection_of_skin_cancer_Aug07.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freedberg KA, Geller AC, Miller DR, Lew RA, Koh HK. Screening for malignant melanoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:738–45. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Girgis A, Clarke P, Burton RC, Sanson-Fisher RW. Screening for melanoma by primary health carephysicians: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Med Screen. 1996;3:47–53. doi: 10.1177/096914139600300112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]