Abstract

Magic Angle Spinning (MAS) NMR spectroscopy is a powerful method for analysis of a broad range of systems, including inorganic materials, pharmaceuticals, and biomacromolecules. The recent developments in MAS NMR instrumentation and methodologies opened new vistas to atomic-level characterization of a plethora of chemical environments previously inaccessible to analysis, with unprecedented sensitivity and resolution.

Keywords: magic angle spinning, MAS, inorganic materials, biological systems, pharmaceuticals, structural analysis, dynamic analysis, NMR spectroscopy

Introduction

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is arguably the most versatile method among analytical techniques. NMR experiments can be performed on the three main states of matter, liquid, solid, and gas, and under a wide range of sample conditions (specimen temperature, pressure, concentration, and morphology). The magnetic interactions are highly sensitive to the local environment, and hence NMR spectra feature exquisite site resolution permitting identification of individual types of nuclei in the context of complex molecules. This site resolution enables detailed atomic-level analysis of molecular structure and dynamics on multiple timescales as fast as nanoseconds and as slow as weeks or months, permits quantification of kinetics and binding, simultaneously for multiple species present in the sample. NMR experiments can be readily tailored to observing a specific interaction (or multiple interactions) of interest, in the bulk of the sample, or (in its imaging, MRI, modality) in a spatially resolved way.

The versatility of NMR brought an array of applications in industry and academia, encompassing basic research into the structure and dynamics of inorganic and biological systems1, drug discovery2, development of novel materials3, medical diagnostics4,5, petroleum and natural gas exploration6,7, explosives analysis8, and many others.

The drawbacks of NMR include relatively low sensitivity, traditionally requiring at least micromolar quantities of material for analysis, which limited to some extent the range of applications. The presence of paramagnetic species in the sample can also make NMR more difficult but also provides an opportunity to obtain additional valuable information. In the recent years, these limitations have been overcome by the technological developments, including the availability of commercial superconducting magnets operating at “high” and “ultrahigh” magnetic fields (17.6 – 23.8 T)9, cryogenic and fast-spinning probes10–14, considerable improvements in the radiofrequency (rf) console technologies, as well as streamlined data acquisition using nonlinear sampling protocols15–17, all transforming the field and bringing the detection limit down to nanomolar quantities of sample.11,18,19

The purpose of this Feature article is to introduce the broader Analytical Chemistry community to the state of the art technologies and applications of NMR spectroscopy to analysis of specimens in the solid phase, using magic angle spinning (MAS) based methods. Solid-phase specimens constitute a huge proportion of naturally occurring and man-made materials that are important technologically, biomedically and from the fundamental-science standpoint. Examples of solid-phase systems include but are not limited to electronic, optical, magnetic, and energy storage materials; heterogeneous catalysts; ceramics and glasses; composite materials; polymers; metal alloys; hydrogels; nanomaterials; biomaterials; synthetic and natural product based pharmaceuticals; minerals; soils; radioactive waste and others. We will demonstrate that MAS NMR spectroscopy is ideally suited for in-depth, atomic-resolution analysis of these kinds of systems in amorphous, crystalline, as well as gel-like environments, under non-destructive conditions, and where other conventional analytical methods provide limited information or fail. We note that for materials where both liquid and solid domains are present, MAS NMR methods permit analysis of the two phases, contrary to other NMR techniques. We will discuss the emerging methodologies for “fast” and “ultrafast” MAS NMR, enabling analysis of nano- to micromole quantities of sample, at atomic resolution and with unprecedented level of structural and dynamic details.

General Principles of MAS NMR

Almost every element in the Periodic Table has at least one magnetically active isotope with non-zero nuclear spin. The majority of the magnetically active isotopes possess spins greater than ½ and the associated nuclear quadrupole moments.20 The gyromagnetic ratios and the natural abundances of magnetically active nuclei vary widely, and hence their relative receptivities. The sensitivity of the NMR experiments is directly connected to the nucleus’ receptivity the latter determining in practice how challenging NMR analysis for a particular nucleus would be. To date, NMR measurements have been performed on essentially every nucleus in the Periodic Table possessing non-zero magnetic moment (with exceptions of short-lived radioactive nuclides).

The typical NMR observables recorded in an experiment are resonance frequencies that are determined by the gyromagnetic ratio of the nucleus, the magnetic shielding interaction, and the quadrupolar interaction (for nuclei with spins greater than ½); peak multiplicities that are determined by the scalar and/or couplings to neighboring nuclei; and peak intensities. Additional information-rich parameters that can be recorded through specialized (often multidimensional) experiments include, for example, homo- and heteronuclear dipole-dipole couplings as well as various relaxation and exchange parameters, which report on internuclear distances and dynamics.

All of the nuclear magnetic interactions are generally anisotropic, i.e., the energy levels and the corresponding resonance frequencies depend on the orientation of the corresponding magnetic moment with respect to the static magnetic field or with respect to the magnetic moments of the coupled nuclei. The orientational dependencies of the main nuclear magnetic interactions are given by Equation 1 below:

| (1) |

where HCS, HQ(1), and HD(1) are the Hamiltonians for chemical shift, first-order nuclear quadrupolar, and first-order dipolar interaction. σiso is the isotropic chemical shift, ω0 is the Larmor frequency of the nucleus and δσ is the chemical shielding anisotropy. Q is the quadrupole moment of the nuclei, Vzz is the largest component of the electric field gradient tensor, h is the Planck constant, and e is the electronic charge. γI and γS represent the gyromagnetic ratios of spin I and S. θ and ϕ determine the orientation of the principal axis system of the tensorial anisotropic interaction with respect to the static magnetic field. Since the Larmor frequency ω0 is the product of the magnetic field and the gyromagnetic ratio, i.e. ω0 = −γB0, it is clear that as the field value increases, both the isotropic (σiso) and anisotropic (δσ) chemical shift terms increase and the isotropic spectrum is better resolved.

The sensitivity of the NMR experiment depends on several factors. The bulk magnetization M is the ratio of populations of the two Zeeman levels (for a spin-1/2), which are given by the Boltzman factor exp(−ΔE/KBT). It can be shown that the equilibrium magnetization is

| (2) |

Where N is the number of spins; KB is the Boltzman constant and I is the spin quantum number. An NMR signal is obtained when the magnetization oscillates with a frequency ω0. Since in the most basic apparatus the signal is measured as voltage in a solenoid coil, the oscillating magnetization M(t) induces an electromotive force ε (emf), which is proportional to the derivative of M. As a result, the NMR signal (Eq. 3) becomes dependent on the square of the magnetic field and on the cube of the gyromagnetic ratio. It follows that high fields and high-γ spins are critical for obtaining enhanced sensitivities in NMR experiments.

| (3) |

Finally, the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) depends on the sample volume, B1 field, and rf power applied to the probe. At room temperatures and negligible preamplifier noise21,

| (4) |

Where B1 is the magnetic field at the sample, P is the power applied to the probe, and VS is the sample volume. In a single coil rf efficiency goes approximately as , where Vcoil is the coil volume.22 Thus attaining maximum signal-to-noise ratio requires the maximum sample volume yet the minimum coil diameter, and the optimum S/N is a compromise between these two conflicting requirements.

In solution, rapid isotropic motions of molecules result in efficient averaging out of the orientational dependence of nuclear magnetic interactions, leaving only the isotropic component detectable. In solid-phase samples, which, for the purpose of this article, we define as those that do not undergo unrestricted isotropic molecular motions, NMR experiments result in broad lines, whose frequency and intensity profiles reflect the orientational distributions of molecules in the sample.23 While these broad lines, called “powder patterns”, bear a wealth of information on local geometric and electronic structure of the molecules under investigation, they are associated with complete loss of resolution precluding detection of multiple sites in a specimen and with severely reduced sensitivity, due to the distribution of spectral intensity over a wide frequency range.

To eliminate the orientational dependence of the NMR anisotropic interactions in solid-phase samples, a commonly used approach is magic angle spinning (MAS),24,25 illustrated in Figure 1. In MAS, the sample is rotated rapidly around an axis of 54.74° with respect to the static magnetic field, resulting in averaging of the anisotropy of nuclear interactions whose frequency depends on the orientation according to a second order Legendre polynomial (in practice, this applies to all interactions except for the second-order quadrupolar coupling and for the cross-terms of the quadrupolar couplings with other anisotropic interactions). Depending on the MAS frequency, a particular interaction can be averaged out either partially (resulting in a spinning sideband envelope, representing the Fourier components of the spinning frequency with intensities of the individual sidebands that depend on the principal components of the respective interaction tensor and the spinning frequency) or completely, the latter occurring when the MAS frequency exceeds the magnitude of the interaction. While complete averaging results in narrow lines, this is achieved at the expense of losing the orientational dependence and hence valuable information on structure and dynamics.

Figure 1.

Left: Schematic representation of MAS NMR setup. The sample is placed into an NMR probe at the “magic” angle of 54.74° with respect to the static magnetic field, and spun rapidly. In practice, MAS frequencies of 10 – 62 kHz are used, and the highest currently attainable MAS frequency in 2014 is 110 kHz.11,19 The bottom photograph illustrates MAS NMR rotors of various diameters ranging from 1.3 to 4 mm. MAS NMR rotors of diameters of 5 and 7 mm are also available from NMR manufacturers, Bruker, Doty Scientific, and others. Middle: Illustration of the effect of MAS on NMR lineshapes in a spin-1/2 nucleus. The broad 13C powder pattern resulting from chemical shift interaction in a static sample (a) is broken up into a series of spinning sidebands (b), which represent the Fourier components of the MAS frequency; and averaged out into an isotropic peak (c) when the MAS frequency exceeds the magnitude of the anisotropic interaction. Right: Illustration of the effect of MAS on NMR lineshapes in a spin – 7/2 nucleus. The broad 51V powder pattern resulting from a combined effect of quadrupolar and chemical shift interactions and spanning the central and satellite transitions in a static sample (d) is broken up in to a series of spinning sidebands (e and f), which represent the Fourier components of the MAS frequency. Note that at 60 kHz, neither the CSA nor the quadrupolar interaction are averaged out, which is a common case in half-integer quadrupolar nuclei in low-symmetry environments.

In practice, both the partial and complete averaging regimes by MAS are widely applied in the experiments on solid-phase specimens, depending on the system under study and the desired information content. When multiple sites need to be detected, MAS NMR measurements are often conducted in a two- or multidimensional format, where isotropic chemical shift dimension(s) is (are) combined with an indirect dimension, where isotropic shifts, anisotropic interactions or multiple-quantum (MQ) coherences are recorded. To restore the anisotropic (or MQ) information in the indirect dimension, specially designed rf pulse schemes are used, where the MAS averaging is perturbed by the interference between the rf field and the mechanical rotation of the sample, the so-called recoupling.26,27 The principle of dipolar recoupling is introduced below.

The mechanical rotation of the sample in the MAS rotor results in time modulation of the dipolar frequency:

| (4) |

where , and is the dipolar frequency; ωR is the rotation frequency; θm is the axis rotation angle, and θij and ϕij are the polar and azimuthal angles defining the orientation of the dipolar vector connecting spins i and j with the magnetic field.

G0 is zero if the sample is rotated at the magic angle, while G1 and G2 are oscillatory terms that are averaged to zero over a single rotor period. Similar expressions can be derived for the other anisotropic interactions given in Eq. 1, with additional terms accounting for their asymmetry (the dipolar interaction is spherically symmetric).

Numerous recoupling pulse schemes have been developed over the past three decades that recouple selectively or jointly different anisotropic interactions that are suitable for various kinds of nuclei and experimental regimes, and this general approach is now used ubiquitously for analysis of structure and dynamics in solid samples containing multiple sites.1 In Figure 2, we describe a Rotational Echo Double Resonance (REDOR)28 pulse scheme that selectively recouples the dipolar interaction for heteronuclear spins. It utilizes pairs of π inversion pulses that are applied synchronously, two every rotor period, thereby preventing the averaging of the dipolar interaction selectively. When a single pulse is applied (Fig. 2a), a chemical shift echo is obtained and the local field (HL) on the detect spin resulting from the coupled spin is zero. This experiment serves as a reference spectrum S0 accounting for relaxation effects and various artifacts. The scheme on the right (Fig. 2b) demonstrates how the local field is preventing the spatial averaging by the action of the additional pulse hence producing a dephased signal S. A plot of (S0−S)/S0 gives a recoupling curve that can be fit to a dipolar coupling constant D, resulting an accurate (±0.1 Å) distance measurement. It should be noted that numerous variations of REDOR and of experiments aimed at measuring distances between like spins (homonuclear interaction) have been introduced over the last three-four decades and that can be found in numerous reviews.29,30

Figure 2.

Rotational Echo Double Resonance – REDOR. (a) The pulse scheme on the top signifies the basic repeat unit of the reference experiment. The local field experience by spin S is shown at the bottom. (b) The pulse scheme on the top signifies the basic repeat unit of the dipolar-dephased experiment. The local field experience by spin S is not averaged to zero and results in a net loss of magnetization due to the I-S dipolar interaction. A recoupling curve is obtained by repeating the experiment for multiples of the basic two-rotor-period units shown above. Reprinted in part from Figure 2 of31. Copyright © 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Dipolar recoupling sequences have been used in numerous analytical applications, and REDOR in particular has been very widely employed due to its robustness, ease of use and accuracy, which is a direct consequence of the ability to obtain a reference experiment. For example, REDOR was applied in a recent study aimed at analyzing the binding site of the lithium ion in the enzyme inositol monophosphatase, the putative target for lithium therapy in bipolar disorder patients.32 According to the inositol depletion hypothesis,33 lithium, which is a low affinity binder (~1 mM), displaces magnesium in one of three binding sites, thereby reducing its activity towards inositol phosphate. By using 7Li-detected REDOR experiments, it was shown that the dipolar recoupling curve could only be fit by three carbonyl carbons located at ~3.0 Å from the lithium site. Therefore, the controversy concerning whether the site contains a single carbonyl vs. three carbonyls could be resolved by these measurements. This information was not available by any other analytical techniques, including X-ray crystallography.

Contemporary Advances in MAS NMR Instrumentation and Methodologies: Pushing the Boundaries

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy has undergone a major transformation in the recent decade and a half, from a fairly specialized method used by expert practitioners in academia and industry to a technique, which is broadly utilized by non-expert researchers in the various settings. This rapid expansion of the field is due to several seminal technological and methodological developments, which made the experimental setup straightforward enough for a non-specialist and, most importantly, led to dramatically increased sensitivity of the experiments and enabled analysis of “challenging” nuclei previously considered unattainable. Below we discuss these key developments.

High magnetic fields (17.6 – 28.1 T)

The development of superconducting magnets operating at 17.6 – 28.1 T has been, without doubt, one of the major transformative technologies in the recent history of NMR spectroscopy. Specific to solid-state NMR, the availability of high magnetic fields has enabled research into systems previously not amenable to atomic-resolution analysis. The examples include but are not limited to materials possessing quadrupolar nuclei with spin > ½ and/or other “challenging” nuclei (those exhibiting low gyromagnetic ratio, low natural abundance, large anisotropic interactions in specific environments, or a combination of these properties)34,35; large biomolecules and biomolecular assemblies1,11,19,36; complex pharmaceuticals and their polymorphs, alone or in the context of interactions with biomolecular receptors37; as well as analysis of whole cells.38,39 For quadrupolar nuclei, the availability of high magnetic fields has been particularly critical because it made accessible for analysis isotopes, such as 43Ca, 39K, 67Zn and others40–43, which are ubiquitous in various inorganic and biological materials. The dramatically increased sensitivity and resolution attained at high magnetic fields enables analysis of very large macromolecular systems that would be intractable at lower fields.

MAS probe technologies

Several recent probe developments have transformed the field. The “low-E”44 “EFree”45, and “scroll coil”46 probes that emerged in the current decade, have permitted analysis of samples with high ionic strength, by eliminating or dramatically reducing the rf heating of the sample. To achieve this purpose, these probes utilize various coil configurations, designed to reduce or eliminate the rf fields delivered into the specimen. In Figure 3, a “low-E” probe is shown. Such probes have been indispensable for analysis of highly hydrated samples and those containing high salt or buffer concentration, such as membrane proteins reconstituted in lipids47, assemblies of HIV-1 proteins containing salt concentrations as high as 1 – 2.4 M48, intact bacteriophage viruses containing high salt concentrations49, and other systems.

Figure 3.

(a) Physical dimensions of the rf coils (in millimeters) and their integration into a MAS stator of a low-E probe; (b) photograph of the probe head. The Teflon coil platform and two pairs of leads can be seen at the bottom of the stator. (c) and (d) A comparison of sample heating in single-solenoid and low-E probes at 600 MHz. (c) RF loss in saline sample per B12 (mW/kHz2) at 600 MHz as function of salt concentration in a 5 mm tube. Remaining losses in the low-E probe are mostly of inductive nature. Note that dielectric loss in the solenoid has nonlinear dependence on sample conductivity. Reduction of conservative electric fields results in 10-fold decrease in sample heating for samples with < 200 mM NaCl, a value that is higher than the buffer strength in the majority of protein sample preparations. (d) Temperature rise in a saline sample (100 mM NaCl buffer doped with 20 mM TmDOTP5−) as a function of time-averaged RF power that reaches the coil under actual experimental conditions during the 1H decoupling pulse. The figure and the caption are reproduced with permission from ref44 and54.

Another transformative technology is fast MAS probes capable of spinning frequencies of 40 – 110 kHz. The first such probe spinning at 40–50 kHz was designed and built in ca. 2001 by Dr. Ago Samoson (Tallinn Institute of Technology)14, who continued to advance the technology, and was the first to build a 100 kHz probe. Since the first fast-MAS probe appeared, the NMR manufacturers (Bruker, Varian, and JEOL) have developed different fast MAS product lines compatible with the corresponding solid-state NMR spectrometers. (We note that as of November 2014, Agilent that has acquired Varian five years prior, has shut down its NMR business) There are multiple advantages in using fast-MAS probes. First, the MAS frequencies of 40 kHz and higher result in dramatic enhancements in resolution11,13, due to the efficient averaging out of heteronuclear dipolar interactions. Furthermore, at 40 kHz and above, 1H detection is efficient, even in fully protonated samples, where the proton linewidths can be sufficiently narrow.11,19,50–52 This benefit is realized fully at rotation frequencies of 100 – 110 kHz, where proton detection in fully protonated or extensively deuterated samples gives rise to unprecedented resolution and sensitivity permitting analysis of nanomole amounts of sample.19 It is worth noting that the small rotor and coil diameter employed in fast-MAS probes (1.6 – 1.9 mm for 40 kHz, 1.2 – 1.3 mm for 60–62 kHz, and 0.7 – 0.9 mm for 100–110 kHz probes) gives rise to natural sensitivity gains over the “conventional” probes employing 3.2 mm and larger rotors (as discussed earlier in the text and shown in Eqn. 4, the sensitivity depends on the inverse of the square root of the coil volume). Under such conditions both 1H and heteronucleus-detected multidimensional MAS NMR experiments are highly efficient, and several examples of resolution and sensitivity gains attained with fast MAS and high magnetic fields are illustrated in Figure 4. Fast MAS is currently a burgeoning area of research, with multiple applications to analysis of inorganic and biological materials, and with emerging methodological developments for conducting correlation spectroscopy under fast MAS conditions.53

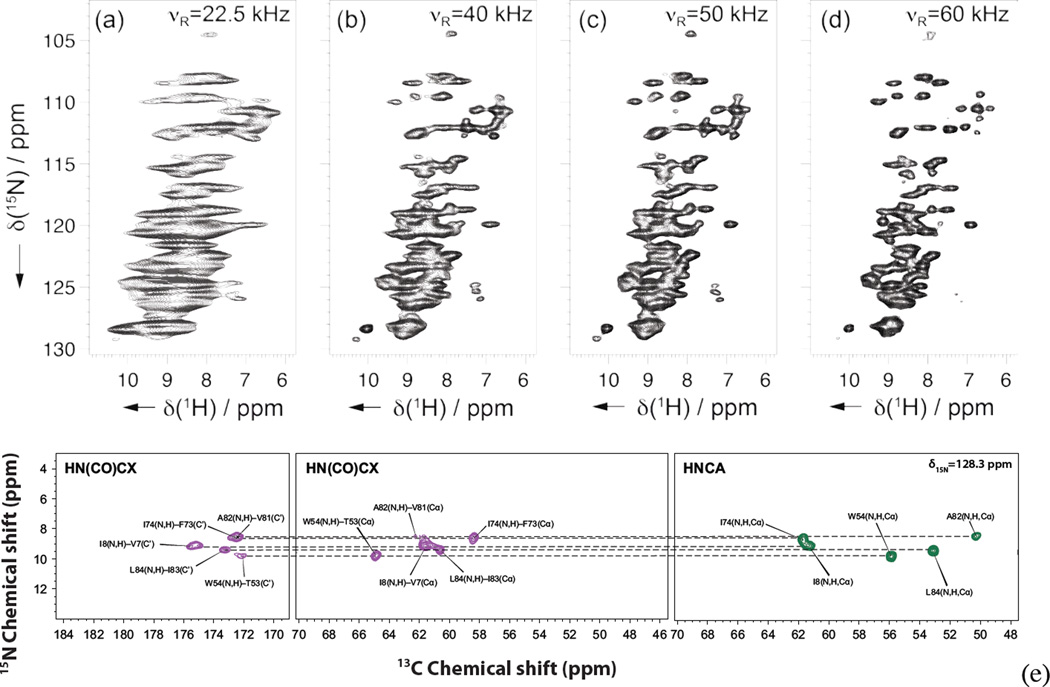

Figure 4.

Proton-detected HN correlation spectra of E. coli [13C,15N]-single-strand DNA binding protein (SSB, 4 × 18 kDa), at a 1H NMR frequency of 800 MHz. MAS rates were respectively 22.5 (a), 40 (b), 50 (c) and 60 kHz (d). Note the dramatic increase in resolution in the indirect 1H dimension with the increase in spinning frequency. (e) Representative 2D H-C planes of the 13C-detected 3D HNCOCX (purple) and HNCA (green) spectrum of U-13C, 15N-LC8 at δ15N = 128.3 ppm acquired at the magnetic field of 19.9 T (850 MHz 1H frequency) and a MAS frequency of 62 kHz. The spectra were recorded with 3.1 mg of sample. The experimental times are 3.5 days for HNCA and 7 days for HNCOCX. The corresponding NCA and NCOCX experiments recorded with conventional 3.2 mm probes at MAS frequencies of 24 kHz and below require 15–30 mg of sample. Panels a–d and e of the figure and the caption are reproduced with permission from refs19,52,55,56, respectively.

Pertinent to applications for analysis of non-conventional and challenging samples are also developments of customized MAS probes, such as probes for high-pressure applications57,58, probes for in-situ high-throughput analysis of pharmaceuticals and other samples59, probes for ultralow temperature applications60–63, as well as probes for analysis of radioactive samples.64–66 A recent highly exciting breakthrough is the announcement of room temperature and cold cryo-MAS probes from Doty Scientific67, which deliver 3 and 12 fold gain in sensitivity, respectively, compared to the conventional probes.

Nonlinear sampling for rapid data collection and sensitivity enhancement

Another vibrant and promising area in MAS NMR is the nonlinear sampling and non-Fourier spectral reconstruction protocols. Nonlinear sampling has been widely used in solution NMR and MRI16,17 but the applications to MAS NMR have lagged behind. In nonlinear NMR methods, the time-domain points are not sampled along the uniform Cartesian grid, but a subset of points is acquired according to a judiciously designed sampling schedule, resulting in considerably shortened experiment time16,17,68–70. While streamlining the data collection has been the most common objective for the use of nonlinear sampling in solution NMR experiments, MAS NMR measurements are usually sensitivity-limited, so another important goal here has been to attain sensitivity enhancement. As demonstrated originally by Rovnyak and colleagues theoretically71 and subsequently confirmed by us experimentally72,73, with appropriately designed random, exponentially biased nonuniform sampling (NUS) schedules, bona fide time-domain sensitivity enhancements of up to 2 fold can be attained in each indirect dimension without compromising spectral resolution. When experiments contain more than one indirect dimension, these sensitivity enhancements are multiplied, so 3–4 fold gains are attainable in a 3D experiment. In practice, NUS-based protocols permit collecting 2D and 3D MAS NMR spectra in cases, where conventional data acquisition would be time prohibitive73. As demonstrated, NUS can be readily combined with paramagnetically assisted condensed data collection (PACC) conducted under fast MAS conditions18, and the integrated NUS-PACC approach yields ca. 16–26 fold time savings in 3D heteronuclear correlation experiments without sacrificing the sensitivity or the resolution.74 A variant of nonlinear data sampling also includes collecting data points in indirect dimensions using variable number of scans per point resulting in sensitivity enhancements albeit at the expense of spectral resolution.75,76

Processing nonlinearly sampled data relies on non-Fourier reconstruction methods, and examples of those include maximum entropy (MaxEnt)68 together with its linear regime variant, maximum entropy interpolation (MINT)73, forward and fast forward maximum entropy (FM)70, G-matrix Fourier transform (GFT)77, spectroscopy by integration of frequency and time domain information (SIFT)78, l1- norm regularization79, multidimensional decomposition (MDD)80, maximum likelihood (ML)81, and other methods that are reviewed elsewhere.15

NMR Crystallography and NMR-Based Structure Determination

Structural analysis is a cornerstone of the application of MAS NMR spectroscopy to chemistry, biochemistry, and materials science. Extensive literature is available on MAS NMR-based structure determination in various biological systems, mostly proteins and protein assemblies.1 We would like to bring to the attention of the reader of this article an emerging approach, NMR crystallography82 for structure determination, at atomic resolution, of solid-phase amorphous or microcrystalline materials that are not amenable to single-crystal diffraction methods. NMR crystallography is a hybrid approach that integrates MAS NMR with quantum chemical calculations and also uses any additional experimental data that are available from other techniques, such as powder X-ray diffraction or other spectroscopies. The NMR data, for all or a subset of atom types in the material of interest, may include isotropic chemical shifts and chemical shift anisotropy tensors, quadrupolar coupling tensors, scalar couplings, as well as internuclear distances (obtained through the measurements of dipolar couplings) or correlation information qualitatively reporting on internuclear proximites. On the basis of these NMR observables and the information about the crystal symmetry obtained through powder X-ray diffraction (if available), the final 3D structure, including crystal packing, can be derived with the aid of quantum chemical calculations.82 NMR crystallography has been successful in identification of polymorphs83, delineating full 3D structures of inorganic materials84 as well as organic solids.85

MAS NMR of Paramagnetic Systems

Analysis of materials containing paramagnetic centers has been traditionally challenging by MAS NMR due to broad lines, short relaxation times, and difficulties in assigning chemical shifts. While initial seminal developments in this area have been made in late 1980’s – early 1990’s,86–88 the field has flourished since the early 2000’s thanks to the technological advances (probes and pulse sequences) as well as better quantum chemical methods available for calculations of paramagnetic NMR parameters. The applications of MAS NMR to paramagnetic systems encompass analysis of biological systems11,89,90 as well as numerous inorganic materials.87,91–93

MAS NMR of Sedimented Solutes

A highly exciting recent development in MAS NMR, which bridges solution and solid phases, are experiments conducted on high molecular weight solutes, such as large proteins and protein complexes, in solution.94–96 These are based on the fact that at commonly used MAS frequencies, molecules of sufficiently high molecular weight are efficiently sedimented to the walls of the MAS rotor, giving rise to highly resolved NMR spectra associated with such immobilized state of the sample. The solute sedimentation is a transient and fully reversible process, induced by sample rotation.96 Applications of this approach are envisioned in a broad range of systems including soluble biological and organic macromolecules that are too large to be studied by the conventional solution NMR approaches.

Recent Examples of MAS NMR Applications for Analysis of Solid-Phase Materials

Inorganic and hybrid materials

The most versatile applications of MAS NMR spectroscopy are arguably in the analysis of inorganic and hybrid materials. Unlike biological or organic solids that typically contain limited subsets of elements from the Periodic Table, inorganic materials exhibit unprecedented compositional versatility, requiring the use of multinuclear NMR techniques. As discussed above, responding to this compositional diversity, over the past decade solid-state NMR researchers have developed experimental protocols for the detection of every magnetically active isotope (with the exception of short-lived man-made radioactive nuclides). With the contemporary NMR technologies and methodologies in hand, a huge array of inorganic materials is now accessible to detailed atomic-resolution analysis by MAS NMR methods. Below, we present a judiciously chosen incomplete set of recent examples.

Energy storage materials: rechargeable Li ion batteries

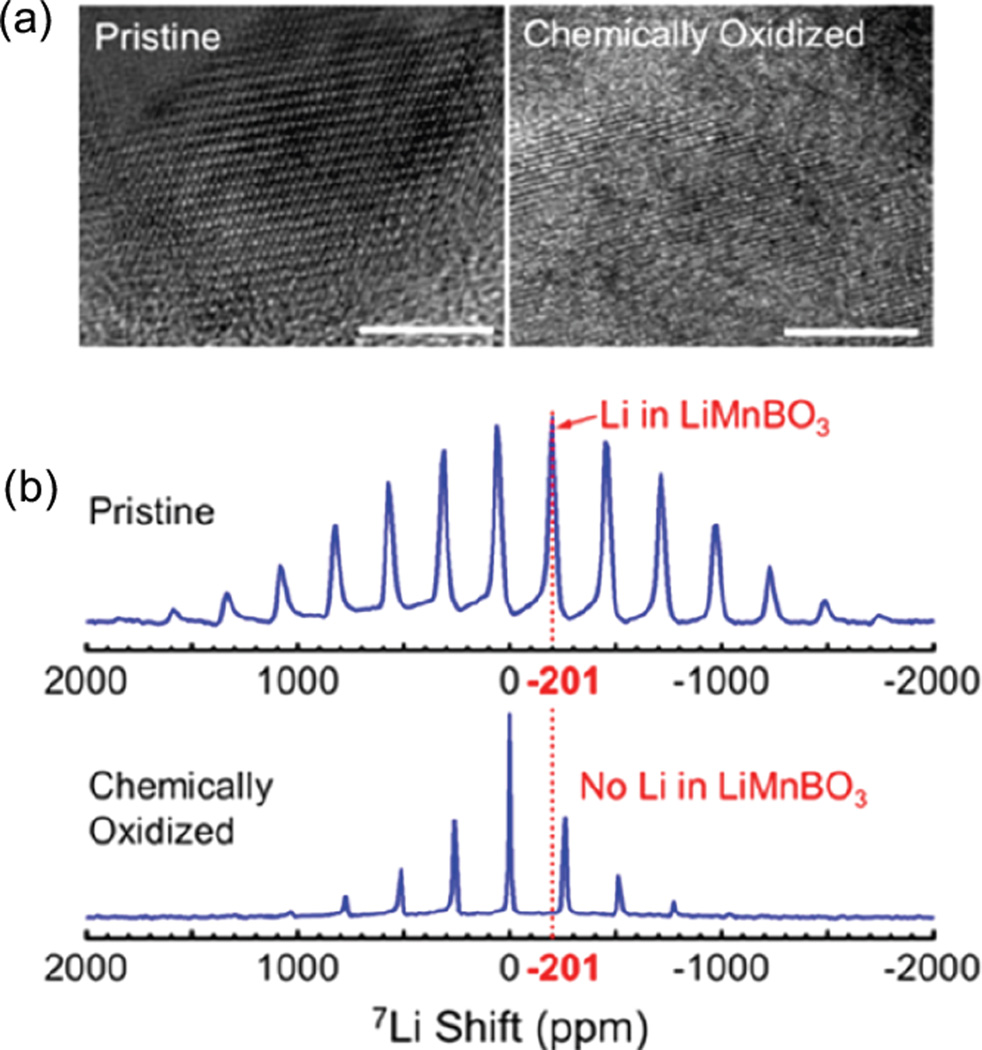

This class of materials has been essential in our daily lives being ubiquitous in consumer electronics and numerous industrial applications. The investigation of Li ion batteries by MAS NMR, now a burgeoning area comprised of multiple research groups, was originally pioneered by Clare Grey.97,98 The challenges associated with the analysis of this class of materials range are associated with the presence of paramagnetic centers as well as the amorphous nature and complex chemical composition of the electrolytes. 6Li and 7Li MAS NMR has been the most widely applied technique to study the structure and dynamics of lithium-ion batteries, whereas paramagnetic shifts in the Li spectra have been shown to be extremely sensitive reporters of the local structure.99,100 These paramagnetically induced shifts can be explained by the Goodenough-Kanamoori rules.101,102 In addition to 6Li / 7Li, 13C, 29Si, and other nuclei have been used as reporters of the local structure of the electrolyte and electrode materials (Figure 5).103–105

Figure 5.

(a) HRTEM images and (b) 7Li 50 kHz MAS NMR spectra of pristine and chemically delithiated Li1−xMnBO3. Monoclinic lithium manganese borate is of interest for its usage as cathode material. The figure and the caption are reproduced with permission from116.

The most recent exciting development is the specialized setup for in situ NMR spectroscopy and imaging of lithium-ion batteries inside the magnet, which already yielded key information concerning the charge-discharge processes in real time inside the NMR magnet.106,107 In situ NMR can allow real-time monitoring of evolution and degradation of chemical species and has been used to investigate lithium-ion batteries, supercapacitors and fuel cells.105 In situ measurements necessitate the use of specialized coil design and NMR hardware.108 Coin cell battery design,109 flat sealed plastic bag,110 and a cylindrical cell design for the sample holder have been used to study entire batteries in the NMR magnet.111 Information obtained from such measurements can help to improve the performance and lifetime of energy storage devices. 7Li in situ NMR spectroscopy has been employed to detect and quantify the formation of metallic lithium microstructure, responsible for short circuits and battery failures leading to characterization of different electrolytes and additives that could help minimize formation of such species.112,113 Similarly, 2H and 13C real-time NMR spectroscopy has allowed for the investigation of circulating methanol and the reaction intermediates in the fuel cells performing electrochemical oxidation of methanol, leading to identification of factors such as methanol cross over which effect their performance.114,115

Heterogeneous catalysts

Examples of applications of MAS NMR spectroscopy to structural analysis of heterogeneous catalyst materials, which are commonly applied in heterogeneous catalysis, are numerous and diverse. For example, a search under “MAS NMR” and “zeolite” in the Web of Science reveals close to 3,000 publications, and the technique has been used to probe the various aspects of zeolite structure, such as the framework structure, the heteroatom substitutions and distribution of defects, host-guest interactions, channel structure and confinement effects, as well as acidity. In the structural analysis of zeolites, multinuclear MAS techniques are commonly used, where both spin-1/2 (e.g., 29Si, 31P, 1H, 19F, 129Xe) and quadrupolar nuclei (e.g., 2H, 27Al, 11B) have served as probes of local environment. We point the interested reader to the recent reviews on the subject.117–121

Metal-organic frameworks represent another widely investigated class of catalytically active materials by MAS NMR. For this class of systems, NMR crystallography approach has been very successful, as discussed in a recent review article.121 Multinuclear MAS NMR spectroscopy has also been commonly applied for the analysis of polyoxometalate based catalysts, where electronic structure of the anions has been investigated as a function of heteroatom substitution and the counterion.122,123

Radioactive materials

MAS NMR spectroscopy of radioactive materials has been particularly challenging due to stringent safety requirements, necessitating highly specialized experimental setups to assure appropriate containment of the radioactive specimens under study. Only a handful of laboratories around the world have the necessary equipment for the analysis of radioactive solids, and hence the literature has been sparse. Various nuclear probes (13C, 17O, 31P, and 23Na) have been employed in the MAS NMR experiments to yield insights into the local structure of the materials and into the changes in the structure induced by the presence of the radioactive species.124–127 Among the interesting recent reports worth noting are the unique insights gained from MAS NMR into the unusual properties of actinide-containing materials resulting from their 5f unpaired electrons.124

Surface species

One of the most exciting recent developments is the analysis of surface species. MAS NMR of surfaces has been extremely challenging for a long time, because of limited sensitivity.128 The developments in dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) technologies have opened doors for facile MAS NMR analysis of surface species in a variety of contexts.128–133

Lesage et al. were the first to demonstrate the use of DNP based methodologies to enhance the sensitivity for the studies of organic functionalities of hybrid silica material (Figure 6).134 Since then, it has been shown that DNP surface enhanced NMR spectroscopy (DNP SENS) provides a viable approach to achieve atomic-level structural and chemical characterization of the surfaces of both porous and nonporous materials.128 Using this methodology, sensitivity enhancements of up to 100 fold can be achieved allowing characterization of material surfaces with naturally abundant 13C, 15N and 29Si nuclei without isotope labeling.135 By monitoring the topology and composition of the functional groups on the surface of the material, DNP SENS can provide information regarding its stability. This approach has been used to characterize silica-based mesostructured organic-inorganic hybrid materials.129 In addition, DNP SENS enables characterization of chemical reactions taking place on the surface functionalities of a hybrid organic-silica material.135 Sensitivity enhancements from DNP SENS have been used to characterize incorporation of functional groups into metal-organic framework (MOF) materials.136

Figure 6.

(a) Pulse sequence used for 1D CP MAS NMR spectroscopy; (b) different covalently incorporated aromatic substrates on the silica material; 13C CP MAS spectra with (top and/or middle) and without (bottom) microwave (MW) irradiation at 263 GHz to induce DNP of I (c) and II (d); (e) contour plots of a DNP-enhanced 2D 1H-13C spectrum of II recorded using MW irradiation of 263 GHz. εH and εC denote the experimental enhancements gained by DNP for 1H and 13C nuclei. The figure and the caption are reproduced with permission from134.

We anticipate that this field will continue to transform rapidly in the near future, and we are likely to witness new methodological breakthroughs enabling new applications.

Pharmaceuticals

Analysis of solid pharmaceuticals is another area where MAS NMR spectroscopy has become an indispensable technique. The developments in methodologies for half-integer quadrupolar nuclei and in NMR crystallography have transformed MAS NMR based analysis of pharmaceuticals. Among many exciting examples we point the reader to studies on polymorph identification using quadrupolar and spin-1/2 nuclei (e.g., 35Cl, 23Na, 17O, 11B, 43Ca, 1H, 13C, 15N, and 19F)137–141 and to the analysis of pharmaceutical excipients where NMR spectra report on the crystallinity and the major/minor forms.142 This information is not easily attainable by any other method. For further in-depth discussions we point the reader to recent reviews on the topic.143,144

Biochemical systems

Biomolecular MAS NMR underwent tremendous growth and development in the recent years. This subdiscipline possibly benefited the most from the technological breakthroughs outlined in the previous sections of the article. It is only through a combination of high and ultrahigh magnetic fields, enhanced probe technologies, improved data acquisition and analysis protocols, and aided by contemporary computational tools that it has become possible to push the boundaries permitting analysis of very large biomolecular assemblies and/or low-concentration species in the context of biomolecules, at atomic resolution. Examples include but are not limited to membrane proteins, assemblies of viral proteins, assemblies of motor proteins associated with cytoskeleton polymers, metalloproteins, nucleic acids, bone minerals and associated proteins, as well as ligand-receptor complexes. MAS NMR studies into structure and dynamics of these and other biomacromolecular systems are discussed in several recent reviews.11,36,53,63,89,90,95

Other examples

In addition to applications in chemistry, materials science and engineering, biophysics and structural biology, MAS NMR methods have found use in other disciplines, such as geosciences145, environmental research146, plant and soil sciences147–149, archaeology150, art history151, as well as oil exploration and processing industry.6,7 Interesting examples of applications of MAS NMR to research into plant cell wall polysaccharides148,152 and other plant biopolymers include the use of MAS NMR to monitor the chemical composition and cellulose crystallinity during delignification and acid pretreatment processes.153–155 13C MAS NMR have also been employed to characterize enzymatic degradation of difficult to decompose lignocellulosic biomass by termites and soil microbiota.156 The interested reader can explore the relevant review articles on the subject such as the study describing the advances in solid state NMR of cellulose.157

Conclusions and Future Outlook

This is an exciting time to do MAS NMR related research. As discussed in the article, the recent advances in all areas have transformed the field. The era where MAS NMR was an insensitive and highly laborious method, used predominantly by experts, is over. MAS NMR has become one of the mainstream techniques both in academia and industry, pursued by numerous practitioners for analysis of a broad range of systems. The seminal developments yielding dramatic sensitivity enhancements have brought the amounts of sample required for MAS NMR analysis into nano- to micromole range, opening doors for atomic-level characterization of challenging specimens, such as surface species and systems containing low-receptivity nuclei. Given the current trajectory of the field, we anticipate that MAS NMR has excellent potential to become a high-throughput method, which will further expand its utility in industrial and academic laboratories.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the US-Israel Binational Science Foundation (Grant 2011077). We acknowledge the support of the National Science Foundation (NSF Grant CHE0959496) for the acquisition of the 850 MHz NMR spectrometer at the University of Delaware and of the National Institutes of Health (NIH Grants P30GM103519 and P30GM110758) for the support of core instrumentation infrastructure at the University of Delaware.

Biographies

Tatyana Polenova is a Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Delaware. She received her undergraduate diploma in Chemistry with excellence from Lomonosov Moscow State University and PhD from Columbia University. She did her graduate and postdoctoral work at Columbia University with Professor Ann McDermott. Her current research interests are the development and applications of magic angle solid-state NMR spectroscopy for structural and dynamics characterization of protein assemblies comprising cytoskeleton and HIV-1 virus; half-integer quadrupolar metal sites in metalloproteins and inorganic materials, particularly those containing vanadium.

Rupal Gupta earned her Ph.D. from Carnegie Mellon University in Bioinorganic Chemistry. Her Ph.D. dissertation focused on the investigations of synthetic and biological paramagnetic metal centers using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and Mössbauer spectroscopy and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Currently, she is a postdoctoral associate in Professor Tatyana Polenova’s laboratory and her research focuses on the development and application of magic-angle spinning solid-state NMR spectroscopy of vanadium-containing proteins and bioinorganic systems.

Amir Goldbourt is a senior lecturer in the School of Chemistry at Tel Aviv University. He received his B.Sc in chemistry and computer science from Tel Aviv University and his Ph.D. in the department of Chemical Physics at the Weizmann institute of science in Rehovot. He performed his postdoctoral research with Prof. Ann McDermott at Columbia University, NY. His research focuses on the development and application of the magic-angle spinning solid-state NMR technique to study the structure and dynamics of biomolecules, in particular viruses, metalloenzymes and the basic development of distance measurements.

Contributor Information

Tatyana Polenova, Email: tpolenov@udel.edu.

Rupal Gupta, Email: rupalg@udel.edu.

Amir Goldbourt, Email: amirgo@post.tau.ac.il.

References

- 1.McDermott AE, Polenova T. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2010. p. 592. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrido L, Beckmann L. New Developments in NMR. Cambridge, UK: The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2013. p. 565. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakhmutov VI. Solid-State NMR in Materials Science: Principles and Applications. CRC Press; 2011. p. 280. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolinska A, Blanchet L, Buydens LM, Wijmenga SS. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2012;750:82–97. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sappey-Marinier D, Briguet A. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Hoboken, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2014. p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rana MS, Ancheyta J, Sahoo SK, Rayo P. Catal. Today. 2014;220:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali F, Khan ZH, Ghaloum N. Energy Fuels. 2004;18:1798–1805. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apih T, Rameev B, Mozzhukhin G, Barras J. In: NATO Science for Peace and Security Series B: Physics and Biophysics. Apih T, Rameev B, Mozzhukhin G, Barras J, editors. Netherlands: Springer; 2014. p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halperin BI, Aeppli G, Ando Y, Aronson M, Basov D, Budinger T, Dimeo R, Gore JC, Hunte F, Lau CN, Maan JC, McDermott A, Minervini J, Ong NP, Ramirez AP, Tesanovic ZB, Tycko R. High Magnetic Field Science and Its Application in the United States: Current Status and Future Directions. Washington, DC: National Research Council; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kovacs H, Moskau D, Spraul M. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2005;46:131–155. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parthasarathy S, Nishiyama Y, Ishii Y. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:2127–2135. doi: 10.1021/ar4000482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.USA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samoson A, Tuherm T, Gan Z. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 2001;20:130–136. doi: 10.1006/snmr.2001.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samoson A, Tuherm T, Past J, Reinhold A, Anupõld T, Heinmaa I. In: New Techniques in Solid-State NMR. Klinowski J, editor. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2005. pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Billeter M, Orekhov V. In: Topic in Current Chemistry. Billeter M, Orekhov V, editors. London New York: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2012. p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoch J, Maciejewski MW, Mobli M, Schuyler AD, Stern AS. In: Encyclopedia of Magnetic Resonance. Harris RK, Wasylishen RE, editors. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012. pp. 2999–3013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoch JC, Maciejewski MW, Mobli M, Schuyler AD, Stern AS. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:708–717. doi: 10.1021/ar400244v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wickramasinghe NP, Parthasarathy S, Jones CR, Bhardwaj C, Long F, Kotecha M, Mehboob S, Fung LW, Past J, Samoson A, Ishii Y. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:215–218. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal V, Penzel S, Szekely K, Cadalbert R, Testori E, Oss A, Past J, Samoson A, Ernst M, Bockmann A, Meier BH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:12253–12256. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wasylishen RE, Ashbrook SE, Wimperis S. In: Encyclopedia of Magnetic Resonance. Wasylishen RE, Ashbrook SE, Wimperis S, editors. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012. p. 533. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doty FD. In: Encyclopedia of NMR. Harris RK, Wasylishen RE, editors. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. pp. 3540–3551. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zilm KW. The 53rd Experimental Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Conference (ENC) Miami, FL: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haeberlen U. High Resolution NMR in Solids. Selective Averaging. San Diego: Academic Press; 1976. p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrew ER, Bradbury A, Eades RG. Nature. 1958;182:1659–1659. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowe IJ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1959;2:285–287. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaroniec CP. In: Encyclopedia of Magnetic Resonance. Harris RK, Wasylishen RE, editors. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012. pp. 1132–1150. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffiths JM, Bennett AE, Griffin RG. In: Encyclopedia of Magnetic Resonance. Wasylishen RE, Ashbrook SE, Wimperis S, editors. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012. pp. 1905–1910. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gullion T, Schaefer J. J. Magn. Reson. 1989;81:196–200. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaroniec CP. eMagRes. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tycko R. eMagRes. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gullion T. Concepts Magn. Reson. 1998;10:277–289. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haimovich A, Eliav U, Goldbourt A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:5647–5651. doi: 10.1021/ja211794x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harwood AJ. Mol. Psych. 2004;10:117–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipton AS, Ellis PD, Polenova T. In: Encyclopedia of Magnetic Resonance. Wasylishen RE, Ashbrook SE, Wimperis S, editors. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012. pp. 3719–3731. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashbrook SE, Sneddon S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:15440–15456. doi: 10.1021/ja504734p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan S, Suiter CL, Hou G, Zhang H, Polenova T. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:2047–2058. doi: 10.1021/ar300309s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williamson PTF. Concepts Magn. Reson. 2009;34A:144–172. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Renault M, Tommassen-van Boxtel R, Bos MP, Post JA, Tommassen J, Baldus M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:4863–4868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116478109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reichhardt C, Cegelski L. Mol. Phys. 2014;112:887–894. doi: 10.1080/00268976.2013.837983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mroué KH, Power WP. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2010;114:324–335. doi: 10.1021/jp908325n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moudrakovski IL, Ripmeester JA. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:491–495. doi: 10.1021/jp0667994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lipton AS, Ellis PD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:9192–9200. doi: 10.1021/ja071430t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Widdifield CM, Moudrakovski I, Bryce DL. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:13340–13359. doi: 10.1039/c4cp01180e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McNeill SA, Gor'kov PL, Shetty K, Brey WW, Long JR. J. Magn. Reson. 2009;197:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.2014 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stringer JA, Bronnimann CE, Mullen CG, Zhou DH, Stellfox SA, Li Y, Williams EH, Rienstra CM. J. Magn. Reson. 2005;173:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahmed MA, Bamm VV, Harauz G, Ladizhansky V. Biophys. J. 2010;99:1247–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han Y, Hou G, Suiter CL, Ahn J, Byeon IJ, Lipton AS, Burton S, Hung I, Gor'kov PL, Gan Z, Brey W, Rice D, Gronenborn AM, Polenova T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:17793–17803. doi: 10.1021/ja406907h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abramov G, Goldbourt A. J. Biomol. NMR. 2014;59:219–230. doi: 10.1007/s10858-014-9840-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou DH, Shea JJ, Nieuwkoop AJ, Franks WT, Wylie BJ, Mullen C, Sandoz D, Rienstra CM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2007;46:8380–8383. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou DH, Shah G, Cormos M, Mullen C, Sandoz D, Rienstra CM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11791–11801. doi: 10.1021/ja073462m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marchetti A, Jehle S, Felletti M, Knight MJ, Wang Y, Xu ZQ, Park AY, Otting G, Lesage A, Emsley L, Dixon NE, Pintacuda G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:10756–10759. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hou G, Suiter CL, Yan S, Zhang H, Polenova T. In: Annu. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. A WG, editor. Burlington House, London, UK: Academic Press; 2013. pp. 293–357. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gor'kov PL, Brey WW, Long JR. In: Encyclopedia of NMR. Wasylishen RE, Harris RK, editors. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012. pp. 3551–3564. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guo C, Hou G, Lu X, O'Hare B, Struppe J, Polenova T. J. Biomol. NMR. 2014;60:219–229. doi: 10.1007/s10858-014-9870-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou DH, Nieuwkoop AJ, Berthold DA, Comellas G, Sperling LJ, Tang M, Shah GJ, Brea EJ, Lemkau LR, Rienstra CM. J. Biomol. NMR. 2012;54:291–305. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9672-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoyt DW, Turcu RV, Sears JA, Rosso KM, Burton SD, Felmy AR, Hu JZ. J. Magn. Reson. 2011;212:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turcu RV, Hoyt DW, Rosso KM, Sears JA, Loring JS, Felmy AR, Hu JZ. J. Magn. Reson. 2013;226:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nelson BN, Schieber LJ, Barich DH, Lubach JW, Offerdahl TJ, Lewis DH, Heinrich JP, Munson EJ. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 2006;29:204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ssnmr.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lipton AS, Sears JA, Ellis PD. J. Magn. Reson. 2001;151:48–59. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lipton AS, Heck RW, Sears JA, Ellis PD. J. Magn. Reson. 2004;168:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Myhre PC, Webb GG, Yannoni CS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:8991–8992. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tycko R. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:1923–1932. doi: 10.1021/ar300358z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martel L, Somers J, Berkmann C, Koepp F, Rothermel A, Pauvert O, Selfslag C, Farnan I. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2013;84:055112. doi: 10.1063/1.4805017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Farnan I, Cho H, Weber WJ, Scheele RD, Johnson NR, Kozelisky AE. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2004;75:5232–5236. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sakellariou D, Le Goff G, Jacquinot JF. Nature. 2007;447:694–697. doi: 10.1038/nature05897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.2014 [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoch J, Stern AS. NMR Data Processing. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1996. p. 230. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maciejewski MW, Mobli M, Schuyler AD, Stern AS, Hoch JC. In: Novel Sampling Approaches in Higher Dimensional NMR. Billeter M, Orekhov V, editors. London New York: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2012. pp. 49–77. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hyberts SG, Frueh DP, Arthanari H, Wagner G. J. Biomol. NMR. 2009;45:283–294. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9368-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rovnyak D, Sarcone M, Jiang Z. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2011;49:483–491. doi: 10.1002/mrc.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Suiter CL, Paramasivam S, Hou G, Sun S, Rice D, Hoch JC, Rovnyak D, Polenova T. J. Biomol. NMR. 2014;59:57–73. doi: 10.1007/s10858-014-9824-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paramasivam S, Suiter CL, Hou G, Sun S, Palmer M, Hoch JC, Rovnyak D, Polenova T. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:7416–7427. doi: 10.1021/jp3032786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sun SJ, Yan S, Guo CM, Li MY, Hoch JC, Williams JC, Polenova T. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:13585–13596. doi: 10.1021/jp3005794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Qiang W. J. Magn. Reson. 2011;213:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li YX, Wang Q, Zhang ZF, Yang J, Hu BW, Chen Q, Noda I, Deng F. J. Magn. Reson. 2012;217:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim S, Szyperski T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1385–1393. doi: 10.1021/ja028197d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Matsuki Y, Eddy MT, Herzfeld J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4648–4656. doi: 10.1021/ja807893k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Donoho DL. Comm. Pure Appl. Math. 2006;59:907–934. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Orekhov VY, Ibraghimov I, Billeter M. J. Biomol. NMR. 2003;27:165–173. doi: 10.1023/a:1024944720653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jeong GW, Borer PN, Wang SS, Levy GC. J. Magn. Reson. 1993;103:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Harris RK, Wasylishen RE, Duer MJ. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2009. p. 520. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Harris RK. In: Encyclopedia of Magnetic Resonance. Wasylishen RE, Ashbrook SE, Wimperis S, editors. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012. pp. 3517–3523. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dupree R. In: Crystallography and NMR. Wasylishen RE, Harris RK, Duer MJ, editors. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Potrzebowski MJ. In: Encyclopedia of Magnetic Resonance. Wasylishen RE, Ashbrook SE, Wimperis S, editors. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012. pp. 890–903. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nayeem A, Yesinowski JP. J. Chem. Phys. 1988;89:4600–4608. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cheetham AK, Dobson CM, Grey CP, Jakeman RJB. Nature. 1987;328:706–707. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu K, Ryan D, Nakanishi K, McDermott A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:6897–6906. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Knight MJ, Felli IC, Pierattelli R, Emsley L, Pintacuda G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:2108–2116. doi: 10.1021/ar300349y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sengupta I, Nadaud PS, Jaroniec CP. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:2117–2126. doi: 10.1021/ar300360q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lennartson A, Christensen LU, McKenzie CJ, Nielsen UG. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:399–408. doi: 10.1021/ic402354r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Clément RJ, Pell AJ, Middlemiss DS, Strobridge FC, Miller JK, Whittingham MS, Emsley L, Grey CP, Pintacuda G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:17178–17185. doi: 10.1021/ja306876u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Michaelis VK, Greer BJ, Aharen T, Greedan JE, Kroeker S. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2012;116:23646–23652. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mainz A, Jehle S, van Rossum BJ, Oschkinat H, Reif B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:15968–15969. doi: 10.1021/ja904733v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bertini I, Luchinat C, Parigi G, Ravera E. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:2059–2069. doi: 10.1021/ar300342f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bertini I, Luchinat C, Parigi G, Ravera E, Reif B, Turano P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:10396–10399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103854108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lee YJ, Wang F, Grey CP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:12601–12613. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee YJ, Wang F, Mukerjee S, McBreen J, Grey CP. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2000;147:803–812. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Strobridge FC, Middlemiss DS, Pell AJ, Leskes M, Clément RJ, Pourpoint F, Lu ZG, Hanna JV, Pintacuda G, Emsley L, Samoson A, Grey CP. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014;2:11948–11957. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Grey CP, Lee YJ. Solid State Sci. 2003;5:883–894. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kanamori J. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 1959;10:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Goodenough JB. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 1958;6:287–297. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cuisinier M, Martin JF, Moreau P, Epicier T, Kanno R, Guyomard D, Dupré N. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 2012;42:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ssnmr.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kim T, Park S, Oh SM. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007;154:A1112–A1117. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Blanc F, Leskes M, Grey CP. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:1952–1963. doi: 10.1021/ar400022u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ilott AJ, Trease NM, Grey CP, Jerschow A. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4536:1–6. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Trease NM, Köster TK, Grey C. Electrochem. Soc. Interface. 2011;20:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rathke JW, Klingler RJ, Gerald RE, Kramarz KW, Woelk K. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 1997;30:209–253. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gerald RE, Sanchez J, Johnson CS, Klingler RJ, Rathke JW. J. Phys.-Condes. Matter. 2001;13:8269–8285. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Letellier M, Chevallier F, Morcrette M. Carbon. 2007;45:1025–1034. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Poli F, Kshetrimayum JS, Monconduit L, Letellier M. Electrochem. Commun. 2011;13:1293–1295. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bhattacharyya R, Key B, Chen HL, Best AS, Hollenkamp AF, Grey CP. Nat. Mater. 2010;9:504–510. doi: 10.1038/nmat2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Key B, Bhattacharyya R, Morcrette M, Seznec V, Tarascon JM, Grey CP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9239–9249. doi: 10.1021/ja8086278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Han OH, Han KS, Shin CW, Lee J, Kim SS, Um MS, Joh HI, Kim SK, Ha HY. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:3842–3845. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Blanc F, Leskes M, Grey CP. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:1952–1963. doi: 10.1021/ar400022u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kim JC, Li X, Moore CJ, Bo SH, Khalifah PG, Grey CP, Ceder G. Chem. Mater. 2014;26:4200–4206. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Li SH, Deng F. In: Annu. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. A WG, editor. Burlington House, London, UK: Academic Press; 2013. pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zheng AM, Deng F, Liu SB. In: Annu. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. A WG, editor. Burlington House, London, UK: Academic Press; 2014. pp. 47–108. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mafra L, Vidal-Moya JA, Blasco T. In: Annu. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. A WG, editor. Burlington House, London, UK: Academic Press; 2012. pp. 259–351. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Koller H, Weiss M. Top. Curr. Chem. 2012;306:189–227. doi: 10.1007/128_2011_123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ashbrook SE, Dawson DM, Seymour VR. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:8223–8242. doi: 10.1039/c4cp00578c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Huang W, Todaro L, Yap GP, Beer R, Francesconi LC, Polenova T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11564–11573. doi: 10.1021/ja0475499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Huang W, Todaro L, Francesconi LC, Polenova T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:5928–5938. doi: 10.1021/ja029246p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Martel L, Magnani N, Vigier JF, Boshoven J, Selfslag C, Farnan I, Griveau JC, Somers J, Fänghanel T. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:6928–6933. doi: 10.1021/ic5007555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Smith AL, Raison PE, Martel L, Charpentier T, Farnan I, Prieur D, Hennig C, Scheinost AC, Konings RJ, Cheetham AK. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:375–382. doi: 10.1021/ic402306c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Goel A, McCloy JS, Windisch CF, Riley BJ, Schweiger MJ, Rodriguez CP, Ferreira JMF. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 2013;4:42–52. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nuñez UC, Eloirdi R, Prieur D, Martel L, Honorato EL, Farnan I, Vitova T, Somers J. J. Alloys Compd. 2014;589:234–239. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rossini AJ, Zagdoun A, Lelli M, Lesage A, Copéret C, Emsley L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:1942–1951. doi: 10.1021/ar300322x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lelli M, Gajan D, Lesage A, Caporini MA, Vitzthum V, Miéville P, Héroguel F, Rascón F, Roussey A, Thieuleux C, Boualleg M, Veyre L, Bodenhausen G, Coperet C, Emsley L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2104–2107. doi: 10.1021/ja110791d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Blanc F, Sperrin L, Jefferson DA, Pawsey S, Rosay M, Grey CP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:2975–2978. doi: 10.1021/ja4004377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rossini AJ, Zagdoun A, Lelli M, Gajan D, Rascon F, Rosay M, Maas WE, Copéret C, Lesage A, Emsley L. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:108–115. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Vitzthum V, Miéville P, Carnevale D, Caporini MA, Gajan D, Copéret C, Lelli M, Zagdoun A, Rossini AJ, Lesage A, Emsley L, Bodenhausen G. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:1988–1990. doi: 10.1039/c2cc15905h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Conley MP, Rossini AJ, Comas-Vives A, Valla M, Casano G, Ouari O, Tordo P, Lesage A, Emsley L, Copéret C. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:17822–17827. doi: 10.1039/c4cp01973c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lesage A, Lelli M, Gajan D, Caporini MA, Vitzthum V, Miéville P, Alauzun J, Roussey A, Thieuleux C, Mehdi A, Bodenhausen G, Coperet C, Emsley L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15459–15461. doi: 10.1021/ja104771z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zagdoun A, Casano G, Ouari O, Lapadula G, Rossini AJ, Lelli M, Baffert M, Gajan D, Veyre L, Maas WE, Rosay M, Weber RT, Thieuleux C, Coperet C, Lesage A, Tordo P, Emsley L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2284–2291. doi: 10.1021/ja210177v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Rossini AJ, Zagdoun A, Lelli M, Canivet J, Aguado S, Ouari O, Tordo P, Rosay M, Maas WE, Coperet C, Farrusseng D, Emsley L, Lesage A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:123–127. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hildebrand M, Hamaed H, Namespetra AM, Donohue JM, Fu RQ, Hung I, Gan ZH, Schurko RW. Cryst Eng Comm. 2014;16:7334–7356. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hamaed H, Pawlowski JM, Cooper BFT, Fu RQ, Eichhorn SH, Schurko RW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:11056–11065. doi: 10.1021/ja802486q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Perras FA, Bryce DL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:4227–4230. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Dicaire NM, Perras FA, Bryce DL. Can. J. Chem. 2014;92:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kong XQ, Shan M, Terskikh V, Hung I, Gan ZH, Wu G. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013;117:9643–9654. doi: 10.1021/jp405233f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Sperger DM, Munson EJ. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech. 2011;12:821–833. doi: 10.1208/s12249-011-9637-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Paradowska K, Wawer I. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014;93:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Holzgrabe U. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2010;57:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Stebbins JF. In: Encyclopedia of Magnetic Resonance. Wasylishen RE, Ashbrook SE, Wimperis S, editors. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2012. pp. 3732–3741. [Google Scholar]

- 146.Simpson AJ, McNally DJ, Simpson MJ. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2011;58:97–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Marin-Spiotta E, Swanston CW, Torn MS, Silver WL, Burton SD. Geoderma. 2008;143:49–62. [Google Scholar]

- 148.White PB, Wang T, Park YB, Cosgrove DJ, Hong M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:10399–10409. doi: 10.1021/ja504108h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Stark RE, Yan B, Ray AK, Chen Z, Fang X, Garbow JR. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 2000;16:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0926-2040(00)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bardet M, Gerbaud G, Giffard M, Doan C, Hediger S, Le Pape L. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2009;55:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- 151.Catalano J, Yao Y, Murphy A, Zumbulyadis N, Centeno SA, Dybowski C. Appl. Spectrosc. 2014;68:280–286. doi: 10.1366/13-07209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Wang T, Zabotina O, Hong M. Biochemistry. 2012;51:9846–9856. doi: 10.1021/bi3015532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Chunilall V, Bush T, Erasmus RM. Cell Chem. Technol. 2012;46:269–276. [Google Scholar]

- 154.Witter R, Sternberg U, Hesse S, Kondo T, Koch FT, Ulrich AS. Macromolecules. 2006;39:6125–6132. [Google Scholar]

- 155.Foston M, Ragauskas AJ. Biomass Bioenerg. 2010;34:1885–1895. [Google Scholar]

- 156.Ogura T, Date Y, Kikuchi J. PloS One. 2013;8:e66919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Foston M. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014;27:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]