Abstract

HIV-1 immunotherapy with a combination of first generation monoclonal antibodies was largely ineffective in pre-clinical and clinical settings and was therefore abandoned1–3. However, recently developed single cell based antibody cloning methods have uncovered a new generation of far more potent broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) to HIV-14,5. These antibodies can prevent infection and suppress viremia in humanized mice (hu-mice) and nonhuman primates, but their potential for human HIV-1 immunotherapy has not been evaluated6–10. Here we report the results of a first-in-man dose escalation phase 1 clinical trial of 3BNC117, a potent human CD4 binding site antibody11, in uninfected and HIV-1-infected individuals. 3BNC117 infusion was well tolerated and demonstrated favorable pharmacokinetics. A single 30 mg/kg infusion of 3BNC117 reduced the viral load (VL) in HIV-1-infected individuals by 0.8 – 2.5 log10 and viremia remained significantly reduced for 28 days. Emergence of resistant viral strains was variable, with some individuals remaining sensitive to 3BNC117 for a period of 28 days. We conclude that as a single agent 3BNC117 is safe and effective in reducing HIV-1 viremia, and that immunotherapy should be explored as a new modality for HIV-1 prevention, therapy, and cure.

A fraction of HIV-1-infected individuals develop potent neutralizing serologic activity against diverse viral isolates4,5. Single cell cloning methods to isolate antibodies from these individuals12 revealed that broad and potent neutralization can be achieved by antibodies targeting many sites on the viral envelope5,13,14. Many of these antibodies can prevent infection, and some can suppress active infection in hu-mice or macaques6–10. Therefore, it is generally accepted that a vaccine eliciting such antibodies is likely to be protective against HIV-1. However, potent anti-HIV-1 bNAbs are highly somatically mutated and many carry other uncommon features such as insertions, deletions, or long complementary determining regions4,5,11,12,15, which may account for the difficulty in eliciting such antibodies by immunization. In view of the efficacy of passive bNAb administration in hu-mice and macaques7–9,16, it has been suggested that bNAbs should be administered passively, or by viral vectors for prevention and immunotherapy4,9,16. However, their safety and efficacy has not been tested in humans.

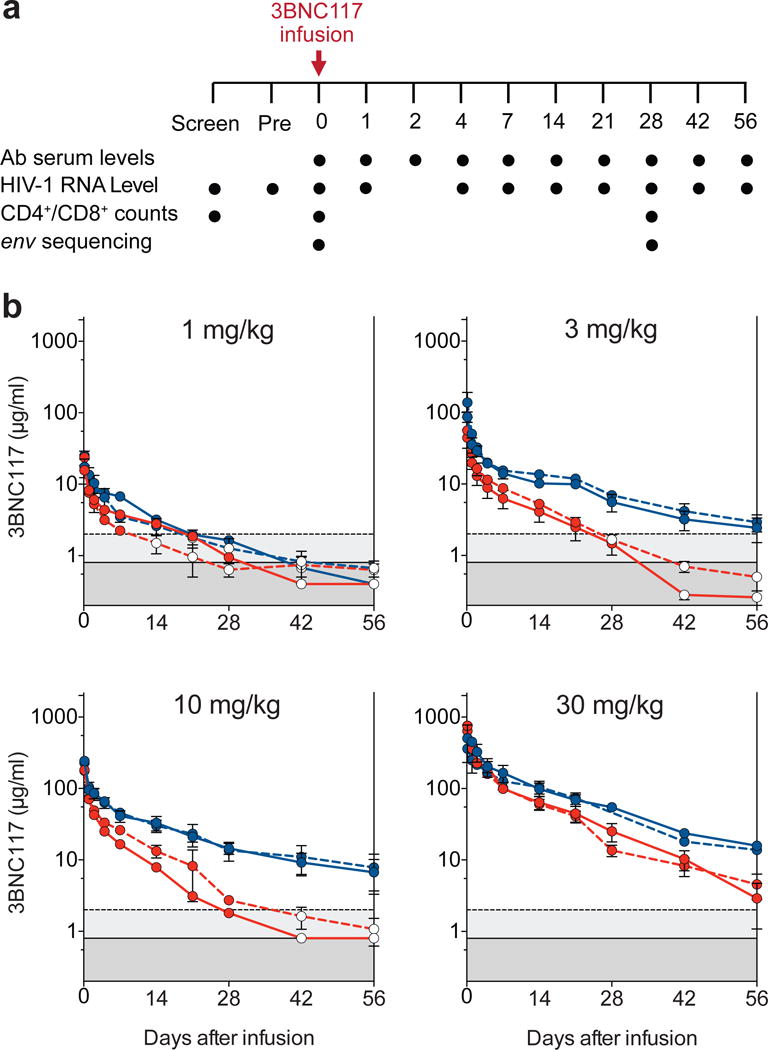

To determine whether the new generation of more potent bNAbs are safe and active against HIV-1 in humans, we initiated an open label phase 1 study (Fig. 1a) with 3BNC117, an anti-CD4 binding site antibody cloned from a viremic controller11. 3BNC117 neutralizes 195 of 237 HIV-1 strains comprising 6 different clades with an average IC50 of 0.08 μg/ml (Extended Data Fig. 1)11. 12 uninfected and 17 HIV-1-infected individuals (Table 1) were administered a single intravenous dose of 1, 3, 10 or 30 mg/kg of 3BNC117 (Extended Data Table 1a). 3BNC117 serum concentrations, plasma HIV-1 viral loads (VL), CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts, and safety were monitored closely (Fig. 1a, Extended Fig. 2, 3, and Extended Data Table 1b, 2). The two groups were comparable for gender, race and age (Table 1).

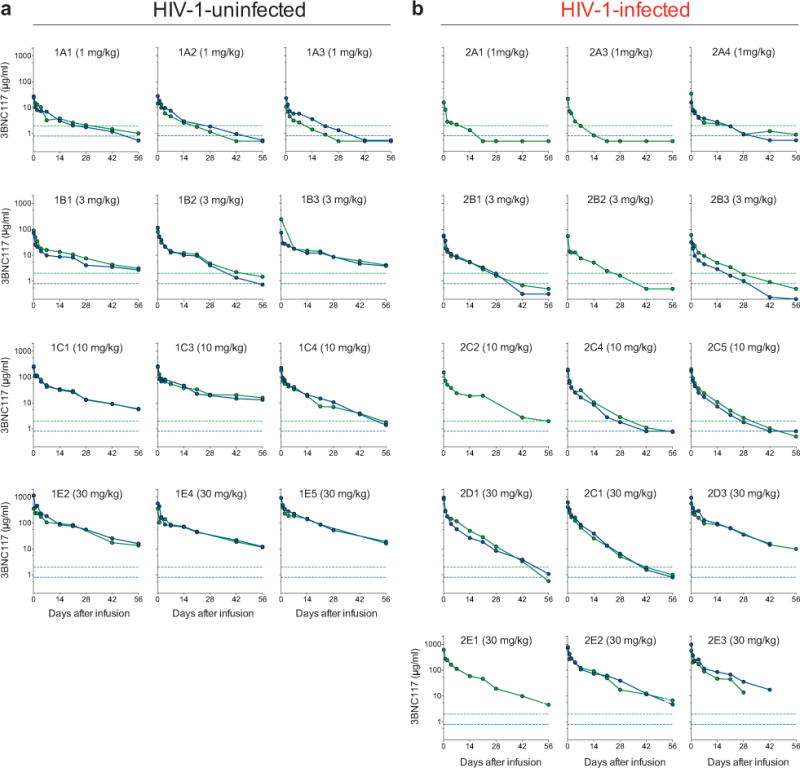

Figure 1. Pharmacokinetics of 3BNC117 in healthy and HIV-1-infected individuals.

a. Diagrammatic representation of the study. Time of 3BNC117 infusion indicated by the red arrow, and sampling for 3BNC117 serum levels, HIV-1 viral load, CD4+/CD8+ counts and env sequencing indicated below. b. Antibody decay measured in TZM.bl assays (solid lines) and ELISA (dotted lines). Mean values and SEM for uninfected individuals (3 per group) are shown in blue and for HIV-1-infected individuals (2–5 per group) in red. Light gray indicates lower level of accuracy by the ELISA assay and dark gray by the TZM.bl assay. Open circles indicate levels lower than the accuracy threshold.

Table 1.

Study participants demographics

| Uninfected (n = 12) | HIV-1-infected (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (% male) | 83% | 76% |

| Mean Age (range) | 43 (22 – 58) | 37 (20 – 54) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 42% | 29% |

| Black or African American | 50% | 53% |

| Hispanic | 8% | 18% |

| ART status | ||

| On ART n (%) | – | 2 (12%) |

| Off ART n (%) | – | 15 (88%) |

|

Mean abs. CD4+ count (cells/μl; day 0) |

– | 655 (245 – 1,129) |

| Mean % CD4+ count (day 0) | – | 29% (20 – 42%) |

|

Mean HIV-1 RNA level (copies/ml; day 0)* |

– | 9,420 (640 – 53,470) |

Mean HIV-1 RNA levels in HIV-1-infected participants off ART

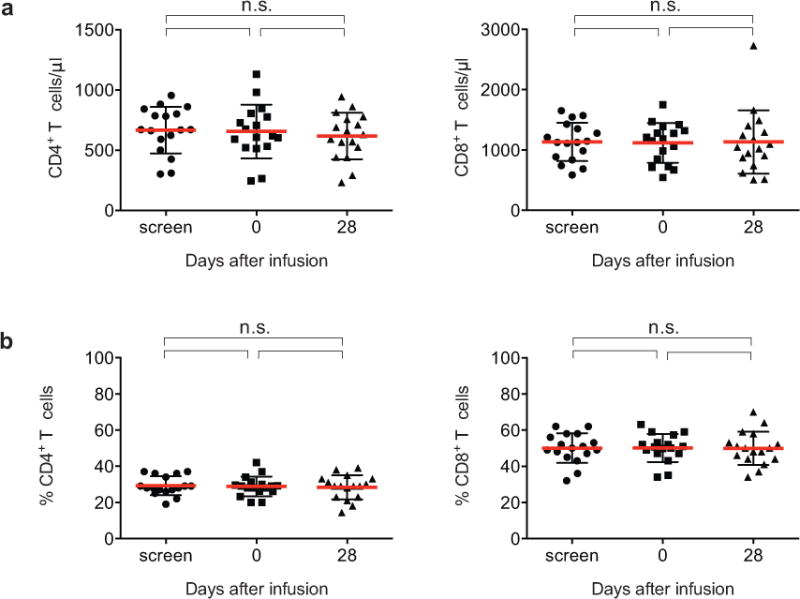

3BNC117 was generally safe and well tolerated at all doses tested in both uninfected and HIV-1-infected individuals. No grade 3, 4 or serious adverse events and no treatment-related laboratory changes were observed during 56 days of follow up (Extended Data Table 1b). CD4+ or CD8+ T cell counts did not change after 3BNC117 infusion in the HIV-1-infected group possibly because initial CD4+ T cell counts were near normal in most participants (mean absolute CD4+ T cell count was 655 cells/μl, Extended Data Fig. 2).

Two different assays were used to measure 3BNC117 levels in serum: TZM.bl neutralization assay to measure activity, and anti-idiotype specific ELISA to measure antibody protein levels (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 3 and Extended Table 4, 5). With few exceptions the two assays were generally in agreement in both groups (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 3). However, elimination of 3BNC117 activity was more rapid in the HIV-1-infected group resulting in an estimated t1/2 of average around 9 days as opposed to around 17 days in uninfected individuals (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Table 4, 5). We conclude that 3BNC117 has pharmacokinetic properties consistent with a typical human IgG1 in uninfected individuals and a somewhat faster decay rate in HIV-1-viremic individuals. Similar antigen dependent enhanced clearance has been reported with anti-cancer antibodies17. Although there may be other explanations, we speculate that the increased rate of antibody elimination in the presence of HIV-1 is due to accelerated clearance of antigen-antibody complexes.

Viral loads were measured by standard assays or by single copy assays. Baseline VLs in HIV-1-infected individuals not on ART varied from 640 – 53,470 copies/ml (mean 9,420 copies/ml). Two participants were on ART at the time of antibody infusion but had detectable baseline VLs (30 and 100 copies/ml). (Table 1, Extended Data Table 2a).

Virologic responses correlated with antibody dose. Infected individuals receiving 1 or 3 mg/kg 3BNC117 doses showed only small and transient changes in viremia consisting of increases of up to 3-fold one day after infusion, followed by a short temporary decrease, and rapid return to baseline (Fig. 2, Extended Data Fig. 4, and Extended Data Table 2a). The magnitude and kinetics of the initial increase in viremia were consistent with those seen with viral entry inhibitors18.

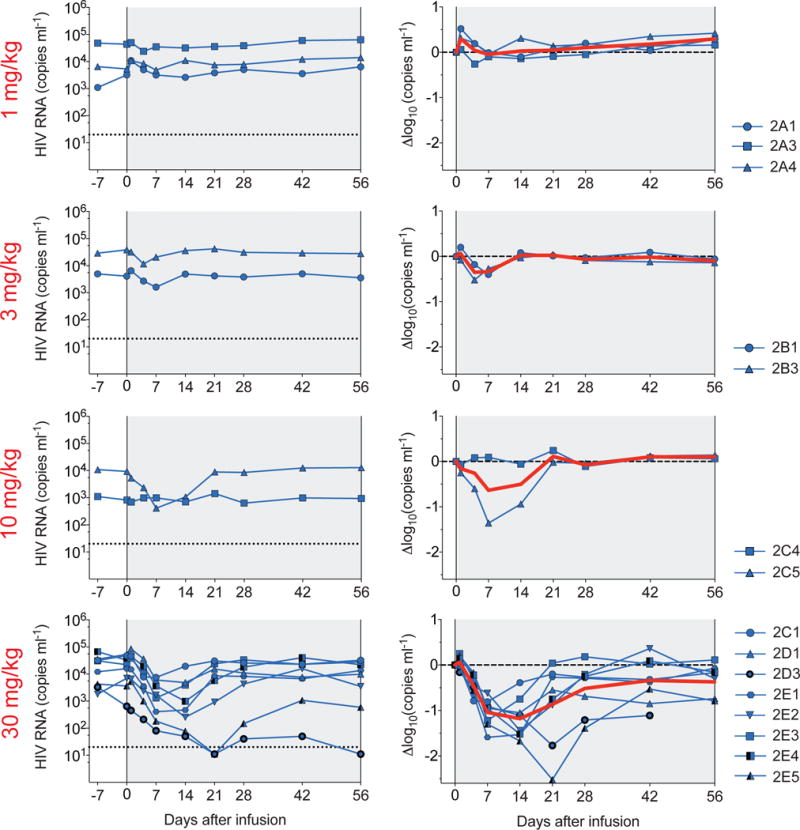

Figure 2. HIV-1 viral load measurements.

3BNC117 dose indicated in red. Plots (left-hand column) show absolute VLs in HIV-1 RNA copies/ml (y-axis) vs. time in days after infusion (x-axis; left panel). Log10 changes (right-hand column) in VL from day 0. Red line illustrates the average (LS-mean, by mixed-effect linear model). Individual subjects are indicated on the right side. Subjects 2E1-5 were pre-screened for 3BNC117-sensitivity. At 30 mg/kg dose level, the change in viremia was significant (p= 0.004, <0.001, <0.001, <0.001, 0.011 at days 4, 7, 14, 21, and 28, respectively) when compared to all available pretreatment values (Extended Data Table 2b).

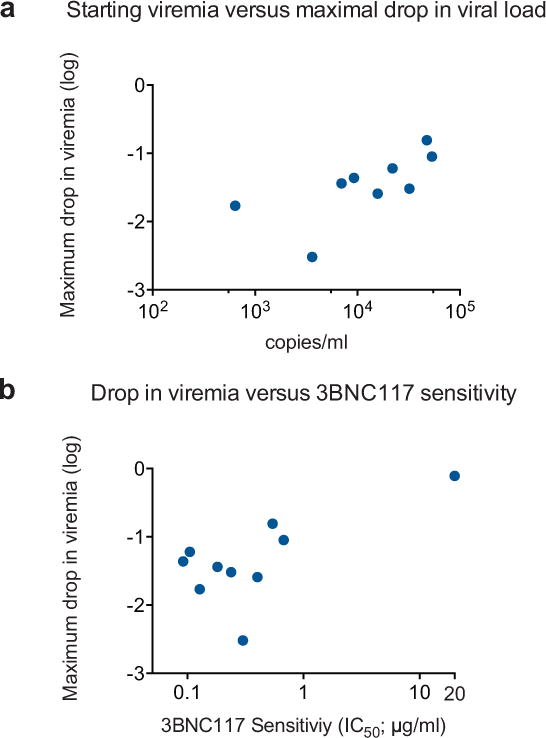

In contrast, 10 out of 11 individuals receiving 10 or 30 mg/kg infusions responded by dropping their VLs by up to 2.5 log10 (Fig. 2, Extended Data Fig. 4 and Extended Data Table 2a). 2 individuals off ART received the 10 mg/kg dose, of whom 1 responded with 1.36 log10 decline in viremia and the other did not (Fig. 2 and Extended Data Table 2a). The individual that did not respond was infected with a virus that was completely resistant to 3BNC117 (2C4; IC50 > 20 μg/ml; Fig. 3 and Extended Data Table 3). All 8 individuals that received the 30 mg/kg dose of 3BNC117 showed highly significant and rapid decreases in their viral loads that varied between −0.8 to −2.5 log10 (Fig. 2 and 3 and Extended Data Table 2a, b). The magnitude of the decline was related to the starting VL and the sensitivity of the subjects’ autologous virus to 3BNC117 (Fig. 2 and 3, Extended Data Fig. 5). The median time to reach the nadir in viremia was 7 days, and the mean drop in VL was 1.48 log10 at nadir. When compared to all available pre-treatment measurements, the drop in viremia was highly significant from days 4 through 28 (Fig. 2 and Extended Data Table 2b). Although the limited data set does not allow us to determine viral set point, 4 of the 8 individuals receiving a single 30 mg/kg infusion did not entirely return to day 0 pre-infusion levels during the observation period of 56 days (Fig. 2 and 3, Extended Data Table 2a).

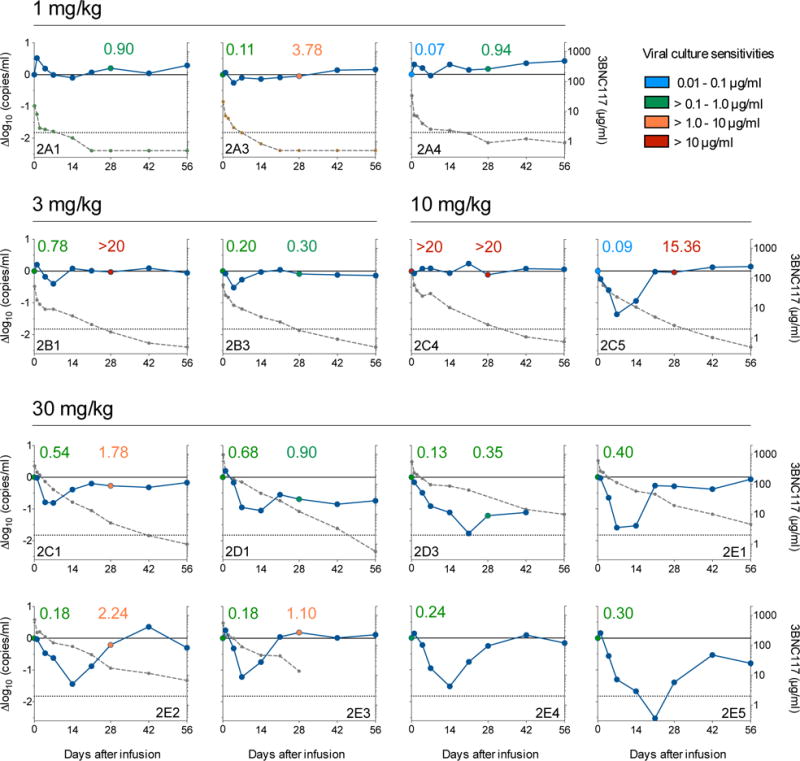

Figure 3. 3BNC117 sensitivity, changes in viremia, and 3BNC117 levels.

3BNC117 dose is indicated on the top of the graphs. The left y-axis shows log10 change in viremia from baseline, and right y-axis shows antibody level measured in ELISA. Blue line reflects change in VL and dotted gray line antibody level. Numbers indicate IC50s for 3BNC117 of autologous viral isolates measured by TZM.bl assay, color-coded as indicated on the top right.

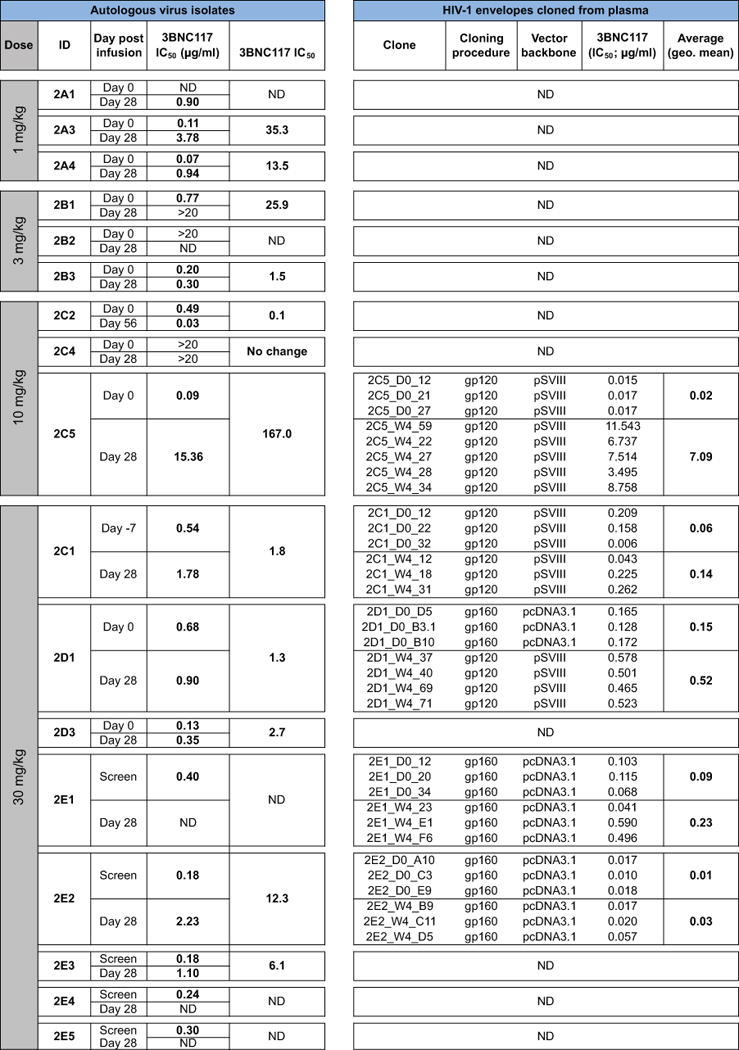

To further examine the virologic effects of 3BNC117 immunotherapy, autologous viral isolates were obtained from cultured PBMCs before (day 0) and after (day 28) antibody infusion. Paired samples from 12 of the 17 HIV-1-infected individuals were tested for 3BNC117-sensitivity (Fig. 3 and Extended Data Table 3). Samples obtained from individuals infused with 1 mg/kg showed 35- and 13.5-fold decreases in 3BNC117-sensitivity indicating that the antibody exerts selective pressure on HIV-1 even at the lowest dose (2A3, 2A4; Fig. 3). Similar changes in sensitivity were seen for some (2B1, 2C5) individuals treated with 3 and 10 mg/kg, but others remained 3BNC117-sensitive throughout (2B3) (Fig. 3, Extended Data Table 3). Similarly, at 30 mg/kg only 2 out of 5 individuals tested showed greater than 5-fold reduction in 3BNC117-sensitivity on day 28 (Extended Data Table 3). In contrast, 2C1, 2D1, 2D3 showed only 3.2-, 1.3- and 2.7 fold changes in sensitivity and these individuals did not rebound to baseline viremia levels at day 28 (Fig. 2 and 3). We conclude that in some individuals HIV-1 develops high-level resistance to 3BNC117 by 28 days after a single dose, while in others it does not.

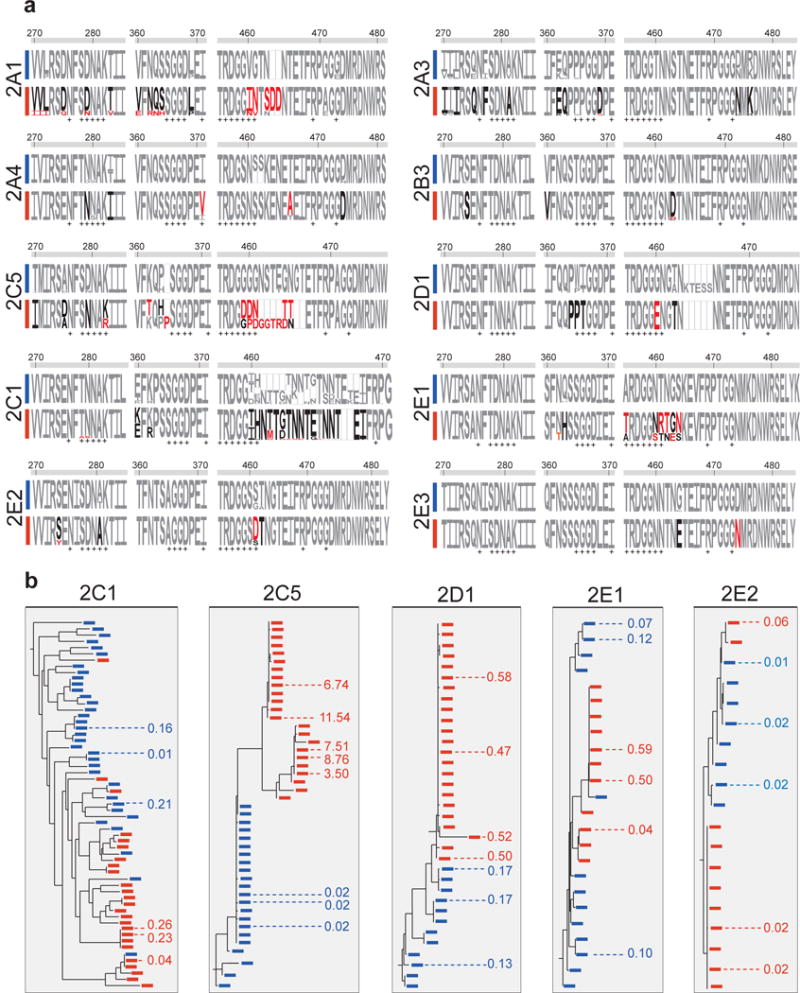

To examine the molecular nature of the changes in HIV-1 in response to 3BNC117, we cloned and sequenced HIV-1 envelopes from paired plasma samples from 10 individuals before and 28 days after infusion. Evidence for antibody-induced selection was seen in some but not all samples analyzed (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 1). For example, 2C5, who received a 10 mg/kg infusion, selected for a G459D mutation in 15 out of 23 env sequences, while the remainder showed a longer V5 loop. The G459D mutation alters the CD4bs and can result in resistance to 3BNC1179. Changes in the V5 loop can alter sensitivity to anti-CD4bs antibodies by steric clashing with the heavy or light chains of 3BNC117-type antibodies. Similarly, 10 or 30 mg/kg infusions selected single mutations at Q363H (2E1), S461D (2E2), and S274Y (2E2) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 1). These changes may alter sensitivity to 3BNC117 by interfering with binding5. Selection in these 3 individuals is also indicated by the emergence of a distinct group of closely related sequences in phylogenetic trees (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 1). Consistent with the molecular analysis, and the viral culture data (Fig. 3), pseudoviruses produced from serum of 2C5 from days 0 and 28 showed high level 3BNC117-resistance, whereas the changes in pseudoviruses produced from 2C1, 2D1, 2E1 and 2E2 were modest (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Table 3). In contrast, autologous viral isolates from individuals, who did not become resistant, or had only small changes in sensitivity, such as 2B3, showed little if any evidence of selection. We conclude that a single infusion of 3BNC117 leads to selection for high-level resistance in some but not all individuals.

Figure 4. HIV-1 envelope sequence analysis after 3BNC117 infusion.

a. HIV-1 envelopes were cloned from plasma samples. Logogram showing Env gp120 regions (amino acid positions; 270–285, 360–371, and 455 to 471–485, according to HXBc2 numbering) indicating sequence changes from day 0 (blue bar) to day 28 (red bar). The frequency of each amino acid is indicated by its height. Red residues represent mutations that were only found after treatment, black residues represent amino acids that changed in frequency after treatment, empty boxes represent gaps, and + symbols represent 3BNC117 contact sites on gp12030. b. Phylogenetic trees show gp120 evolution from day 0 to 28 after treatment for 2C1, 2C5, 2D1, 2E1 and 2E2. Blue and red bars represent sequences obtained on days 0 and 28 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Illustrated values represent the IC50 of 3BNC117 in μg/ml against the cloned HIV-1 pseudoviruses from the analyzed sequences (Extended Data Table 3). The geometric means of the pseudoviruses’ IC50s on days 0 and 28 respectively are for 2C1: 0.06 and 0.14 μg/ml; 2C5: 0.02 and 7.09 μg/ml; 2D1: 0.15 and 0.52; 2E1: 0.09 and 0.23 μg/ml; 2E2: 0.01 and 0.03 μg/ml.

Although immunotherapy was initially used to treat infectious diseases, the great majority of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies are currently used to treat cancer and autoimmune diseases. This form of therapy has been shown to be highly effective, well tolerated, and to function in large part by engaging the host immune system through Fc receptors19.

In contrast, a role for antibodies in controlling HIV-1 infection has been difficult to establish. For example, the overall course of infection is not thought to be altered in individuals that develop bNAbs20. Moreover, first generation anti-HIV-1 bNAbs with limited breadth and activity produced little if any measurable effects in hu-mice or viremic individuals3,21. However, antibodies can put strong selective pressure on the virus in individuals that develop anti-HIV-1 antibody responses22–24. In addition, recent studies in hu-mice showed that, when administered as monotherapy, new generation bNAbs can transiently reduce VLs, and in combination they control viremia for as long as concentrations remain in the therapeutic range6,9. In contrast, single antibodies led to control of viremia in SHIV-infected macaques for as long as antibody levels remained therapeutic, and immune escape was rarely observed7,8. The surprising difference between hu-mice and macaques might be attributed in part to an intact host immune system in the macaque, including endogenous antibodies25, or differences between SHIV and HIV-1 infection. Our data establish that passive infusion of single bNAbs can have profound effects on HIV-1 viremia in humans.

Combinations of antiretroviral drugs are the standard of care for HIV-1 infection because resistance develops to single agents26. Similarly, monotherapy with 3BNC117 alone is insufficient to control infection, and we expect that antibody-drug or antibody-antibody combinations will be required for complete viremic control. Although the current generation of drugs is less expensive than antibodies, the latter have very long half-lives and have the potential to kill infected cells and to enhance host immunity by engaging Fc receptors19,27. Moreover, anti-HIV-1 antibodies can be made 100-fold more potent by molecular engineering28. Finally, the combination of antibodies with agents that activate latent viruses can interfere with the HIV-1 reservoir in hu-mice29 and may be critical to HIV-1 eradication strategies.

Given the difficulties in developing an HIV-1 vaccine and in eradicating established infection, passive transfer of monoclonal antibodies is being considered for HIV-1 prevention, therapy, and cure. Our data establish the principle that monoclonal antibodies can be both safe and effective against HIV-1 in humans. Antibody-mediated immunotherapy differs from currently available drugs in that it has the potential to impact the course of HIV-1 infection by directly engaging host immunity.

Methods

Study design

An open-label, dose-escalation phase 1 study was conducted in uninfected (Group 1) and HIV-1-infected subjects (Group 2; www.clinicaltrials.gov; NCT02018510). Study participants were enrolled sequentially according to eligibility criteria. A standard “3+3” phase I trial design was be used in the dose-escalation phase of the study. 3BNC117 was administered as a single intravenous infusion at four dose levels: 1mg/kg (subjects 1A1, 1A2, 1A3, 2A1, 2A3, 2A4), 3 mg/kg (subjects 1B1, 1B2, 1B3, 2B1, 2B2, 2B3), 10 mg/kg (subjects 1C1, 1C3, 1C4, 2C2, 2C4, 2C5) or 30 mg/kg (subjects 1E2, 1E3, 1E5, 2D1, 2C1, 2D3, 2E1, 2E2, 2E3, 2E4, 2E5), at a rate of 100 or 250 ml/hr. Study participants were followed for 56 days after infusion. All participants provided written informed consent before participation in the study and the study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice. The protocol was approved by the Federal Drug Administration in the USA, the Paul Ehrlich Institute in Germany and the Institutional Review Boards at the Rockefeller University and the University of Cologne.

Study Participants

All study participants were recruited at the Rockefeller University Hospital, New York, USA and at the University Hospital Cologne, Cologne, Germany. Eligible subjects were adults aged 18 – 65 years, HIV-1-infected or uninfected, and without concomitant hepatitis B or C infections. HIV-1-infected subjects enrolled in study groups 2A through 2E were ART-experienced or naïve. In groups 2A through 2D, subjects were either off standard ART for at least 8 weeks prior to study participation and had plasma HIV-1 RNA levels between 2,000 and 100,000 copies/ml, or they were on standard ART but had plasma HIV-1 RNA levels > 20 copies/ml, measured on two separate occasions at least 1 week apart. Subjects recruited into group 2E were HIV-1-infected, off ART (2,000 – 100,000 copies/ml), and differed from the other groups in that they were pre-screened for sensitivity to 3BNC117 as described below. Subjects with CD4+ T-cell counts < 300 cells/μl, clinically relevant deviations from normal physical findings, abnormal electrocardiogram (ECG), and/or laboratory examinations were excluded. Women of childbearing potential were required to have a negative result of a serum pregnancy test on the day of 3BNC117 infusion. HIV-1-infected individuals, who were not on standard ART at enrollment, were given the option to initiate ART 6 weeks after 3BNC117 infusion.

Study Procedures

The appropriate volume of 3BNC117 was calculated according to study dose group, diluted in sterile normal saline to a total volume of 100 or 250 ml, and administered intravenously over 60 minutes. Study participants received 3BNC117 on day 0 and remained under close monitoring in the inpatient unit of the Rockefeller University Hospital for 24 hours. Participants returned for frequent follow up visits for safety assessments that included physical examination, measurement of clinical laboratory parameters such as hematology, chemistries, urinalysis, coagulation times, pregnancy tests (for women) as well as HIV-1 viral loads and CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counts (Fig. 1a). Adverse events were graded according to the DAIDS AE Grading Table (HIV-1-infected groups) or the Toxicity Grading Scale for Healthy Adult and Adolescent Volunteers Enrolled in Preventive Vaccine Clinical Trials (uninfected groups). Blood samples (30 to 120 ml) were collected before and at multiple times after 3BNC117 infusion. Samples were processed within 4h of collection, and serum and plasma samples were stored at −80°C. PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation. The absolute number of peripheral blood mononuclear cells was determined by an automated cell counter (Vi-Cell XR; Beckman Coulter), and cells were cryopreserved in fetal bovine serum plus 10% DMSO.

Plasma HIV-1 RNA Levels

Plasma was collected for measuring HIV-1 RNA levels at screening (from day −49 to day −14), the day −7 pre infusion visit (from day −42 to day −2), day 0 (before infusion), and on days 1, 4, 7, 14, 21, 28, 42 and 56. HIV-1 RNA levels were determined using the Roche COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HIV-1 Assay, Version 2.0, which detects 20–10×106 copies/ml, or by the ABBOTT RealTime Assay, which detects 40–10×106 copies/ml. In samples with HIV-1 RNA < 20 copies/ml, viremia was measured by a quantitative real-time, reverse transcriptase (RT)-initiated PCR (RT-PCR) assay that can quantify HIV-1 RNA down to 1 copy/ml as previously described31.

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts were determined at screening, on day 0 (before infusion), and day 28 by a clinical flow cytometry assay, performed at LabCorp or at the University Hospital Cologne. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Leukocytes were determined as CD45+ cells. Percentage of cells positively stained for CD3, CD4, CD8 as well as the CD4/CD8 ratio were analyzed with the BD Multiset software (BD Biosciences).

3BNC117 Study Drug

3BNC117 is a recombinant, fully human IgG1κ mAb recognizing the CD4 binding site on the HIV-1 envelope11. The antibody was cloned from an HIV-1-infected viremic controller in the International HIV Controller Study11,32, expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells (clone 5D5-5C10), and purified using standard methods. The 3BNC117 drug substance was produced at Celldex Therapeutics Fall River (MA) GMP facility, and the drug product was fill-finished at Gallus BioPharmaceuticals (NJ). The resulting purified 3BNC117 was supplied as a single use sterile 20 mg/ml solution for intravenous injection in 8.06 mM sodium phosphate, 1.47 mM potassium phosphate, 136.9 mM sodium chloride, 2.68 mM potassium chloride, and 0.01% polysorbate 80. 3BNC117 vials were shipped and stored at 4°C.

Measurement of 3BNC117 serum levels

Serum levels of 3BNC117 were determined by using two separate methods (ELISA and TZM.bl). 3BNC117 serum concentrations were measured by a validated sandwich ELISA. Plates (Sigma-Aldrich PN: CLS3590 96-well, High Bind, polystyrene) were coated with 4 μg/ml of an anti-idiotypic antibody specifically recognizing 3BNC117 (anti-ID 1F1 mAb), and incubated overnight at 2–8°C. After washing, plates were blocked for 1 h with 5% BSA. Serum samples, QCs and standards were added (1:50 minimum dilution in 5 % BSA) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. 3BNC117 was detected using an HRP-conjugated mouse anti-human IgG kappa chain specific antibody (Abcam PN: ab79115) and the HRP substrate tetra-methylbenzidine. 3BNC117 concentrations were then interpolated from a standard curve of 3BNC117 using a 4 parameter logistic curve-fitting algorithm. The reference standard and positive controls were created from the drug product lot of 3BNC117 utilized in the clinical study. The capture anti-idiotypic antibody was produced by immunizing BALB/c mice with a Fab’ fragment of 3BNC117 and plasma was tested for the presence of neutralizing antibodies in an ELISA. Briefly, the HIV-1 antigen (2CC core protein) was coated to a plate and blocked. Plasma dilutions were pre-incubated with a sub-saturating concentration of 3BNC117 then added to the plate. Binding to the antigen was detected with an HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG-Fc specific antibody. Plasma was considered neutralizing if it was able to block the binding of 3BNC117 to the antigen coated plate. Two mice were selected for fusion. Those hybridomas that showed high specificity when comparing binding to 3BNC117 versus binding to the irrelevant human IgG1 antibody were selected to expand, screened in the neutralization assay as described above, subcloned and purified for use in the anti-idiotype specific ELISA.

In addition, the concentration of active 3BNC117 was determined by TZM.bl neutralization assay7,8. Serum samples were heat-inactivated for 1h at 56°C and measured for neutralizing activity against an HIV-1 strain that was highly sensitive to 3BNC117 but resistant to any autologous HIV-1 neutralizing serum activity. In all uninfected subjects serum samples were tested against Q769.d22 and ID50 values were derived by using a 5-parameter curve fitting, considering accurate within the pre-established limits (3-fold variation with a 20% error rate). The serum concentration of active 3BNC117 was calculated by taking into account the sera ID50 titers multiplied by the known IC50 of 3BNC117 for Q769.d22. In HIV-1-infected subjects pre-infusion samples were first tested against a panel of 3BNC117-sensitive HIV-1 strains that included Q769.d22 (Clade A1, Tier 2), YU2.DG (Clade B, Tier 2), Q259.d2.17 (Clade C, Tier 1B), Q842.d12 (Clade A1, Tier 2), ZM135M.PL10a (Clade C, Tier 2), and TRO.11 (Clade B, Tier 2). A single strain per subject was selected that showed no or only minimal background activity and 3BNC117 serum levels were determined in the same way as described for Q769.d22.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Blood samples were collected immediately before, at the end, 0.5, 3, 6, 9, 12 and 24 hours after completion of the 3BNC117 infusion, and on days 2, 4, 7, 14, 21, 28, 42 and 56. 3BNC117 serum levels were obtained from ELISA (Celldex Therapeutics) and TZM.bl neutralization assay, and PK-parameters were estimated by performing a non-compartmental analysis (NCA) using WinNonlin 6.3.

Neutralization assay

Serum samples, viral supernatants, and control antibodies were tested against HIV-1 envelope pseudoviruses as previously described33,34.

Virus cultures

Autologous virus was retrieved from HIV-1 infected individuals as previously described35. Briefly, healthy donor PBMCs were obtained by leukapheresis from a single donor. Cells were cultured at a concentration of 5 × 106/ml in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Thermo Scientific), 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Gibco), and 1 μg/ml Phytohemagglutinin (Life Technologies) at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 2–3 days, 5×106 cells were transferred into IMDM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin, 5 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma), and 10 U/ml of IL-2, and co-incubated with 2–3 × 106 PBMCs from the study participants obtained before and 28 days or later after 3BNC117 infusion (Extended Data Table 3). Media was replaced on a weekly basis and culture supernatants quantified using the Alliance HIV-1 p24 Antigen ELISA kit (PerkinElmer) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. TCID50s were determined for all HIV-1 containing supernatants33,34 and then tested for sensitivity against 3BNC117 in a TZM.bl neutralization assay. Outgrowth of autologous virus isolates from subjects with low level viremia was performed as previously described36. Briefly, 2–5 million CD4+ T cells were cultured in the presence of 10 million irradiated healthy donor PBMCs and 3 million healthy donor PHA stimulated CD8+ depleted lymphoblasts. Lymphoblasts were replenished weekly by adding 3 million healthy donor PHA stimulated CD8+ depleted lymphoblasts. Blood samples and leukopheresis were collected under separate IRB-approved protocols and after study participants provided informed consent.

Sequence analysis

HIV-1 RNA was extracted from plasma samples using the Qiagen MinElute Virus Spin kit (Qiagen) followed by first strand cDNA synthesis using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and the antisense primer env3out 5′–TTGCTACTTGTGATTGCTCCATGT–3′37 or 5′–GGTGTGTAGTTCTGCCAATCAGGGAAGWAGCCTTGTG–3′6. gp160 env was amplified using envB5out 5′–TAGAGCCCTGGAAGCATCCAGGAAG–3′ and envB3out 5′–TTGCTACTTGTGATTGCTCCATGT–3′ in the first round and second round nested primers envB5in 5′–CACCTTAGGCATCTCCTATGGCAGGAAGAAG–3′ and envB3in 5′–GTCTCGAGATACTGCTCCCACCC-3′. First round PCR was performed using a High Fidelity Platinum Taq (Invitrogen) at 94°C, 2 min; (94°C, 15 sec; 55°C 30 sec; 68°C, 4 min) × 35; 68°C, 15 min. Second round PCR was performed with 2 μl of 1. PCR product as template and Phusion Hot Start Polymerase at 98°C, 30 sec; (98°C, 8 sec; 55°C, 20 sec; 72°C, 1 min) × 35; 72°C, 6 min. gp120 env was amplified using first round primers and conditions as described, but second round was performed by using second round nested primers 5′–TAGAAAGAGCAGAAGACAGTGGCAATGA-3′ and 5-′TCATCAATGGTGGTGATGATGATGTTTTTCTCTCTGCACCACTCTTCT-3′. Second round PCR was performed with 1 μl of 1. PCR product as template and High Fidelity Platinum Taq (Invitrogen) at cycling conditions, 94°C, 2 min; (94°C, 15 sec; 58°C, 35 sec; 68°C, 2 min and 30 sec) × 35; 68°C, 10 min. Following the second-round PCR amplification, 0.5 μl Taq polymerase was added to each 50 μl reaction and an additional 72°C extension for 15 min was performed to add 3′dA overhangs for cloning inserts into pCR4-TOPO. PCR amplicons were gel purified and ligated into pCR4-TOPO (Invitrogen) or pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen), followed by transfection into MAX Efficiency Stbl2 Competent Cells (Life Technologies). Individual colonies were analyzed for insert length by PCR, and successfully cloned envelopes sequenced by a set of env specific primers. Sequence alignments and mutation analysis of gp120 and gp160 was performed by using Geneious Pro software, version 5.6.7 (Biomatters Ltd.), and residues were numbered according to HXBc2. Phylogenetic trees were generated using the PhyML tool at the Los Alamos HIV website38, and sequence analysis was performed using Antibody database by Anthony West39. Logograms were generated using the Weblogo 3.0 tool40. Selected sequences were used to generate pseudovirues and tested for 3BNC117 sensitivity in a TZM.bl assay37.

Statistical analyses

The sample size to detect > 1 log10 decline in viremia with 80% power at 5% of significance was determined to be 5 HIV-1-infected individuals, not on ART, infected with 3BNC117-sensitive viruses assuming that the standard deviation would be similar to 3BNC117 effects in hu-mice (Horwitz et al. 2013). Adverse events were summarized by the number of subjects who experienced the event, by severity grade and by relationship to 3BNC117 according to the DAIDS AE Grading Table (HIV-1-infected groups) or the Toxicity Grading Scale for Healthy Adult and Adolescent Volunteers Enrolled in Preventive Vaccine Clinical Trials (uninfected groups). PK-parameters were estimated by performing a non-compartmental analysis (NCA) using WinNonlin 6.3. CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counts before and after 3BNC117 were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. To assess the changes in HIV-1 viral loads, we used a mixed-effect linear model where dose and time were fixed effects and random intercepts for each participant. These models take full advantage of the repeated measure structure of the data while estimating parameters for each dose simultaneously, hence improving the power of small study groups. The final model was fitted assuming an AR(1) correlation structure over time, which was the best in terms of AIC/BIC criteria. The significance of the effect of 3BNC117 on viral load, defined as change between each time point and day 0, was assessed using least-squares means within each dose group (Extended Data Table 2b). Sensitivity analysis was also carried out with variations of these models and the same conclusions were achieved. Pearson and nonparametric Spearman coefficients were calculated to assess the correlation between maximum drop in viremia after 3BNC117 infusion and baseline HIV-1 viral load or baseline sensitivity of autologous viruses to 3BNC117.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1.

HIV-1 neutralizing activity of 3BNC117. a. Summary of 3BNC117 neutralizing in vitro activity based on 237 HIV-1 isolates comprising 6 different clades. Data were retrieved from the ‘AntibodyDatabase’ by Anthony West (West et al., PNAS, 2013). b. Illustration of the fraction (i.e. % coverage; y-axis) of HIV-1 isolates that are neutralized at a given IC50 (μg/ml; x-axis) using the same data set.

Extended Data Figure 2.

CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counts before and after 3BNC117 infusion. a. Absolute numbers (cells/μl) of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell counts of all enrolled HIV-1-infected participants at screen, on the day of 3BNC117 infusion (day 0), and at day 28 after infusion. b. Percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells for the same subjects and time points. Mean and standard deviation are indicated in red and black, respectively. No significant differences between pre-infusion and post infusion levels were detected by using One-way ANOVA.

Extended Data Figure 3.

3BNC117 serum concentration and activity in single subjects. Serum levels of 3BNC117 in all uninfected (a) and HIV-1-infected (b) individuals that received 1, 3, 10, or 30 mg/kg 3BNC117 at day 0. Antibody levels were measured by a sandwich ELISA using an anti-3BNC117 specific antibody (green) or by measuring the 3BNC117 serum activity in a TZM.bl neutralization assay (blue).

Extended Data Figure 4.

3BNC117 sensitivity and changes in viremia in 2 ART-treated subjects 3BNC117 sensitivity and changes in viremia of subjects 2B2 and 2C2. Both subjects were on ART when enrolled in the study and received a single dose (2B2, 3 mg/kg; 2C2, 10 mg/kg) of 3BNC117 at day 0. The left y-axis shows log10 change in viremia from baseline, and right y-axis shows antibody level measured in ELISA. Blue line reflects change in VL and dotted gray line antibody level. Numbers indicate IC50s for 3BNC117 of autologous viral isolates measured by TZM.bl assay, color-coded as indicated on the right.

Extended Data Figure 5.

Correlating viral decay with 3BNC117 sensitivity and starting viral load. a. Maximum decline in viral load in ART-untreated HIV-1-infected participants with baseline 3BNC117-sensitive viruses (IC50 < 1 μg/ml) versus pretreatment (day 0) viral load (Pearson coefficient r = 0.72 p = 0.03; Spearman coefficient rho = 0.78, p = 0.02). b. Maximum drop in viral load in HIV-1-infected and 3BNC117-sensitive individuals receiving a 10 or 30 mg/kg dose of 3BNC117 (y-axis) versus baseline autologous virus sensitivity to 3BNC117 (x-axis; Pearson coefficient r = 0.69 p = 0.03; Spearman coefficient rho = 0.41, p = 0.23).

Extended Data Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of HIV-1-infected individuals and 3BNC117 safety data. a. Baseline characteristics of HIV-1-infected individuals. *, absolute CD4 T cell count was 309 and 302 cells/mm at screening. **, DRV/r/TDF/FTC, darunavir, ritonavir tenofovir, emtricitabine; ATV/r/3TC/ZDV – atazanavir, ritonavir, lamividune, zidovudine. ND, Not Determined. b. 3BNC117 safety data. AE, adverse events. Subject 2D3 developed herpes zoster involving a lumbar dermatome 35 days after infusion. The event was graded as moderate and considered not related to 3BNC117.

| a

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study ID | 3BNC117 dose | Age | Years since HIV Diagnosis | Current ART regimen | Clade | HIV-RNA level (copies/ml) | abs. CD4* T cell count (day 0; cells/mm3) |

| 2A1 | 1 mg/kg | 35 | 11 | ART naïve | B | 3,210 | 674 |

| 2A3 | 1 mg/kg | 39 | 14 | Off ART | B | 43,650 | 520 |

| 2A4 | 1 mg/kg | 42 | 8 | ART naïve | B | 5,340 | 607 |

| 2B1 | 3 mg/kg | 20 | 1 | Off ART | ND | 4,090 | 264* |

| 2B2 | 3 mg/kg | 48 | 20 | DRV/r/TDF/FTC** | ND | 100 | 706 |

| 2B3 | 3 mg/kg | 20 | 1 | ART naïve | B | 38,190 | 777 |

| 2C2 | 10 mg/kg | 51 | 12 | ATV/r/3TC/ZDV** | ND | 30 | 728 |

| 2C4 | 10 mg/kg | 54 | 23 | Off ART | ND | 820 | 805 |

| 2C5 | 10 mg/kg | 50 | 4 | ART naïve | B | 9,260 | 245* |

| 2D1 | 30 mg/kg | 33 | 3 | ART naïve | B | 53,470 | 980 |

| 2C1 | 30 mg/kg | 51 | 17 | Off ART | B | 47,650 | 1129 |

| 2D3 | 30 mg/kg | 33 | 0.5 | ART naïve | ND | 640 | 618 |

| 2E1 | 30 mg/kg | 21 | 2 | ART naïve | B | 15,780 | 847 |

| 2E2 | 30 mg/kg | 46 | 1.5 | ART naïve | B | 6,990 | 513 |

| 2E3 | 30 mg/kg | 23 | 1.5 | ART naïve | BF | 22,030 | 590 |

| 2E4 | 30 mg/kg | 38 | 1 | ART naïve | ND | 32,220 | 603 |

| 2E5 | 30 mg/kg | 30 | 1 | ART naïve | ND | 3,610 | 532 |

| b

| ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Events | No. AEs | %of reported AEs | No. possibly related | No. Mild | No. Moderate | No. Severe | Uninfected (No. of AEs) | HIV-1-infected (No. of AEs) | ||||||

| 1 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg | 10 mg/kg | 30 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg | 10 mg/kg | 30 mg/kg | |||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Rhinorrhea and/or cough | 10 | 16.9 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Malaise | 7 | 11.9 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 6 | 10.2 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Diarrhea | 5 | 8.5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Myalgia/arthralgia (localized) | 4 | 6.8 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Sore throat | 4 | 6.8 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Tenderness | 3 | 5.1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Increased Lacrimation | 2 | 3.4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Myalgia | 2 | 3.4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Chills | 2 | 3.4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Conjunctival erythema | 2 | 3.4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fevershiness | 2 | 3.4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 2 | 3.4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 2 | 3.4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Blurry vision | 1 | 1.7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 1 | 1.7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Erythema | 1 | 1.7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Paresthesia upper extremity | 1 | 1.7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shingles | 1 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Vomiting | 1 | 1.7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Extended Data Table 2.

HIV-1 RNA levels and viral decay mixed-effect linear model. a. HIV-1 RNA levels. Subjects 2B2 and 2C2 were on ART. Subject 2D3 started ART after day 42. Screen was performed between day −49 and day −14. Viremia measurements at “Pre” were performed between day −42 and day −2.

|

Extended Data Table 3.

Sensitivity of autologous virus isolates and cloned HIV-1 envelopes to 3BNC117. ND, Not Determined.

|

Extended Data Table 4.

Pharmakokinetics of 3BNC117 based on a 56-day period post infusion. Estimation of PK parameters retrieved from study participants (ID) up to 8 weeks post 3BNC117 infusion. 3BNC117 was administered at 1, 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg in uninfected (Negative) and HIV-1-infected (Positive) individuals. 3BNC117 serum concentrations were determined by ELISA or TZM.bl assay (see Methods). PK-parameters were obtained by performing a non-compartmental analysis (NCA) using WinNonlin 6.3. T1/2 was estimated using values between Lambda upper/lower. n.d., PK parameters were not determined because of insufficient data or an extrapolated AUC_inf that exceeded 25%. Values in red indicate extrapolated AUC_inf >10%.*, Days post infusion of 3BNC117.

| ID | HIV-1/ART | 3BNC117 (mg/kg) |

Method | Cmax (μg/ml) |

adjusted R-squared |

Estimated T1/2 (days) |

Lambda (lower)* |

Lambda (upper)* |

AUC (INF_pred) |

Tlast* | Clast (μg/ml) |

AUC_% Extrap_pred |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A1 | Negative | 1 | ELISA | 27.4 | n.d. | n.d. | – | – | n.d. | – | – | n.d. |

| TZM.bl | 27.4 | 0.936 | 21.32 | 14 | 42 | 184.0 | 42 | 1.2 | 19.2 | |||

| 1A2 | Negative | 1 | ELISA | 18.8 | n.d. | n.d. | – | – | n.d. | – | – | n.d. |

| TZM.bl | 27.8 | 0.893 | 12.89 | 7 | 42 | 181.7 | 42 | 1.0 | 9.0 | |||

| 1A3 | Negative | 1 | ELISA | 11.2 | n.d. | n.d. | – | – | n.d. | – | – | n.d. |

| TZM.bl | 23.5 | 0.976 | 10.38 | 4 | 28 | 138.0 | 28 | 1.3 | 14.0 | |||

| 2A1 | Positive/Off | 1 | ELISA | 15.7 | n.d. | n.d. | – | – | n.d. | – | – | n.d. |

| 2A3 | Positive/Off | 1 | ELISA | 22.7 | n.d. | n.d. | – | – | n.d. | – | – | n.d. |

| 2A4 | Positive/Off | 1 | ELISA | 33.8 | n.d. | n.d. | – | – | n.d. | – | – | n.d. |

| TZM.bl | 15.6 | n.d. | n.d. | – | – | n.d. | – | – | n.d. | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 1B1 | Negative | 3 | ELISA | 89.9 | 0.985 | 19.64 | 7 | 56 | 685.2 | 56 | 3.1 | 12.1 |

| TZM.bl | 70.9 | 0.881 | 24.30 | 7 | 56 | 483.7 | 56 | 2.7 | 17.9 | |||

| 1B2 | Negative | 3 | ELISA | 90.1 | 0.878 | 12.91 | 7 | 42 | 523.5 | 42 | 2.2 | 8.8 |

| TZM.bl | 116.0 | 0.936 | 10.04 | 7 | 42 | 481.2 | 42 | 1.4 | 4.6 | |||

| 1B3 | Negative | 3 | ELISA | 243.4 | 0.954 | 21.54 | 14 | 56 | 1017.3 | 56 | 4.2 | 12.1 |

| TZM.bl | 74.5 | 0.954 | 21.70 | 7 | 56 | 706.6 | 56 | 3.9 | 15.6 | |||

| 2B1 | Positive/Off | 3 | ELISA | 90.8 | 0.942 | 9.60 | 4 | 21 | 219.4 | 21 | 2.8 | 19.2 |

| TZM.bl | 57.4 | 0.994 | 10.28 | 7 | 28 | 245.9 | 28 | 1.9 | 12.1 | |||

| 2B2 | Positive/On | 3 | ELISA | 97.6 | 0.928 | 8.74 | 7 | 21 | 200.7 | 21 | 2.5 | 16.5 |

| 2B3 | Positive/Off | 3 | ELISA | 60.0 | 0.981 | 9.08 | 4 | 21 | 251.2 | 21 | 3.5 | 17.0 |

| TZM.bl | 32.6 | 0.994 | 9.19 | 4 | 28 | 129.8 | 28 | 1.0 | 10.1 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 1C1 | Negative | 10 | ELISA | 347.8 | 0.942 | 16.33 | 7 | 56 | 1667.9 | 56 | 5.9 | 7.5 |

| TZM.bl | 281.8 | 0.964 | 15.79 | 7 | 56 | 1598.9 | 56 | 5.6 | 7.3 | |||

| 1C3 | Negative | 10 | ELISA | 308.9 | 0.860 | 29.01 | 7 | 56 | 2529.4 | 56 | 15.8 | 23.5 |

| TZM.bl | 244.7 | 0.700 | 26.59 | 14 | 56 | 2228.5 | 56 | 13.1 | 19.3 | |||

| 1C4 | Negative | 10 | ELISA | 180.6 | 0.835 | 10.73 | 7 | 42 | 859.1 | 42 | 4.0 | 5.5 |

| TZM.bl | 230.7 | 0.990 | 10.56 | 14 | 56 | 1022.0 | 56 | 1.4 | 2.2 | |||

| 2C2 | Positive/On | 10 | ELISA | 326.8 | 0.866 | 10.87 | 7 | 42 | 904.5 | 42 | 2.7 | 5.6 |

| 2C4 | Positive/Off | 10 | ELISA | 178.2 | 0.944 | 6.92 | 4 | 28 | 550.2 | 28 | 2.8 | 5.1 |

| TZM.bl | 193.0 | 0.979 | 6.14 | 4 | 28 | 417.9 | 28 | 1.8 | 3.4 | |||

| 2C5 | Positive/Off | 10 | ELISA | 201.1 | 0.997 | 6.60 | 7 | 28 | 592.6 | 28 | 2.6 | 4.1 |

| TZM.bl | 174.4 | 0.994 | 6.50 | 7 | 28 | 431.2 | 28 | 1.8 | 3.7 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 1E2 | Negative | 30 | ELISA | 360.8 | 0.930 | 14.48 | 7 | 56 | 4259.4 | 56 | 13.6 | 5.9 |

| TZM.bl | 1166.3 | 0.978 | 16.19 | 14 | 56 | 5901.2 | 56 | 16.1 | 6.2 | |||

| 1E3 | Negative | 30 | ELISA | 361.8 | 0.990 | 16.26 | 7 | 56 | 3177.5 | 56 | 11.7 | 8.2 |

| TZM.bl | 606.2 | 0.989 | 17.85 | 7 | 56 | 3422.2 | 56 | 12.3 | 9.3 | |||

| 1E5 | Negative | 30 | ELISA | 765.0 | 0.992 | 14.15 | 4 | 56 | 5874.2 | 56 | 16.3 | 5.7 |

| TZM.bl | 939.6 | 0.959 | 15.22 | 14 | 56 | 6424.5 | 56 | 19.1 | 6.1 | |||

| 2C1 | Positive/Off | 30 | ELISA | 410.2 | 0.991 | 5.80 | 7 | 28 | 1707.8 | 28 | 5.1 | 2.6 |

| TZM.bl | 717.4 | 0.993 | 5.99 | 7 | 42 | 2186.4 | 42 | 1.6 | 0.6 | |||

| 2D1 | Positive/Off | 30 | ELISA | 976.4 | 0.996 | 6.86 | 7 | 42 | 2494.9 | 42 | 3.4 | 1.3 |

| TZM.bl | 849.3 | 0.990 | 8.83 | 7 | 56 | 1825.5 | 56 | 1.1 | 0.8 | |||

| 2D3 | Positive/Off | 30 | ELISA | 571.0 | 0.962 | 13.39 | 7 | 56 | 3616.5 | 56 | 9.9 | 4.8 |

| TZM.bl | 953.7 | 0.993 | 11.23 | 7 | 42 | 4346.2 | 42 | 16.0 | 6.0 | |||

| 2E1 | Positive/Off | 30 | ELISA | 712.4 | 0.970 | 11.14 | 14 | 56 | 3028.5 | 56 | 4.6 | 2.3 |

| 2E2 | Positive/Off | 30 | ELISA | 789.4 | 0.920 | 11.14 | 7 | 56 | 3596.1 | 56 | 6.7 | 2.4 |

| 2E3 | Positive/Off | 30 | ELISA | 559.6 | 0.821 | 8.54 | 7 | 28 | 2495.6 | 28 | 13.7 | 8.4 |

Extended Data Table 5.

Summary of 3BNC117 pharmakokinetics based on a 56-day period post infusion. (1) Estimation of half-lives; SD, standard deviation.

| Dose | HIV-1-status | Subjects | Method (subjects analyzed) | Cmax (μg/ml) | t1/2 (days) (1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | ||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| 1 mg | Neg. | 3 | ELISA (3) | 19.1 | 8.1 | 11.2 – 27.4 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| TZM.bl (3) | 26.2 | 2.4 | 23.5 – 27.8 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |||

| 1 mg | Pos. | 3 | ELISA (3) | 24.1 | 9.1 | 15.7 – 33.8 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| TZM.bl (1) | 23.5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |||

| 3 mg | Neg. | 3 | ELISA (3) | 141.1 | 88.6 | 89.9 – 243.4 | 18.0 | 4.5 | 12.9 – 21.5 |

| TZM.bl (3) | 87.1 | 25.1 | 70.9 – 116.0 | 18.7 | 7.6 | 10.0 – 24.3 | |||

| 3 mg | Pos. | 3 | ELISA (3) | 73.7 | 35.7 | 32.6 – 97.6 | 9.2 | 0.4 | 8.7 – 9.6 |

| TZM.bl (3) | 50.6 | 15.7 | 32.6 – 61.7 | 11.2 | 2.2 | 9.5 – 13.73 | |||

| 10 mg | Neg. | 3 | ELISA (3) | 279.1 | 87.5 | 180.6 – 347.8 | 18.7 | 9.4 | 10.7 – 29.0 |

| TZM.bl (3) | 252.4 | 26.4 | 230.7 – 281.8 | 17.7 | 8.1 | 10.7 – 26.6 | |||

| 10 mg | Pos. | 3 | ELISA (3) | 235.4 | 80.0 | 178.2 – 326.8 | 8.1 | 2.4 | 6.6 – 10.9 |

| TZM.bl (3) | 213.6 | 52.6 | 174.4 – 273.4 | 8.8 | 4.3 | 6.5 – 13.7 | |||

| 30 mg | Neg. | 3 | ELISA (3) | 495.9 | 233.1 | 360.8 – 765.0 | 15.0 | 1.1 | 14.2 – 16.3 |

| TZM.bl (3) | 904.0 | 281.7 | 1166.3 – 606.2 | 16.4 | 1.3 | 15.2 –17.9 | |||

| 30 mg | Pos. | 6 | ELISA (6) | 669.8 | 199.7 | 410.2 – 976.4 | 9.9 | 3.3 | 5.8 – 13.7 |

| TZM.bl (3) | 840.1 | 118.4 | 717.4 – 953.7 | 8.9 | 2.3 | 6.7 – 11.2 | |||

| All | Neg. | 12 | ELISA (9) | – | – | – | 17.2 | 5.5 | 10.7 – 29.0 |

| TZM.bl (9) | – | – | – | 17.6 | 5.7 | 10.0 – 26.6 | |||

| All | Pos. | 15 | ELISA (12) | – | – | – | 9.3 | 2.6 | 5.7 – 13.7 |

| TZM.bl (9) | – | – | – | 9.6 | 2.9 | 6.1 – 13.7 | |||

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all individuals who participated in this study. We thank the Rockefeller University Hospital Clinical Research Support Office and nursing staff, as well as Tim Kümmerle, Christoph Wyen, and Larry Siegel for help with recruitment; Szilárd Kiss for ophthalmologic assessments; Frank Maldarelli and Jeff Lifson for single copy analysis and Brandie Freemire for technical assistance; James Pring, Amr Almaktari, Cecile Unsen, Sonya Hadrigan, Eleonore Thomas, Henning Gruell, Daniel Gillor, and Ute Sandaradura de Silva for sample processing and study coordination, and Natalie Rodziewicz for help with HIV-1 culturing. We thank Audrey Louie and Christoph Conrad for help with regulatory submissions; Larry Thomas for IND-enabling studies, Laura Vitale for cell line and anti-idiotype antibody development, Bill Riordan, Amy Rayo and Joseph Andreozzi for anti-idiotype ELISA method development and sample analysis, Russ Hammond for process development, and Steve DiSciullo for 3BNC117 manufacturing; James Perry for performing neutralization assays. We thank Mayte Suarez-Farinas for support with statistical analysis; Pat Fast and Harriet Park for clinical monitoring; and Emil Gotschlich and Barry Coller for input on study design. J.C.L. is supported by an award from CNPq “Ciencia sem Fronteiras” Brazil (248676/2013-0). This work was supported in part by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery (CAVD) Grants OPP1033115 (M.C.N.), OPP1092074 (M.C.N.), OPP1040753 (A.P.W.) and OPP1032144 (M.S.S.), and U19AI111825-01 Cooperative Centers on Human Immunology from NIH to M.C.N., by grant #UL1 TR000043 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), by a grant from the Robertson Foundation to M.C.N., in part with Federal funds from the NCI/NIH, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E, and a grant from the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) to G.F. 3BNC117 was generated from a subject in the International HIV Controller Study, supported by the Mark and Lisa Schwartz Foundation and CAVD Grant 43307. M.C.N. and B.D.W. are Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigators. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Authors Contributions

M.C. and F.K. planned and implemented the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; J.C.L. performed sequence analyses, and contributed to writing the manuscript; M.S.S. performed TZM.bl neutralization assays; A.P.W. assisted with sequence analyses; N.B., G.K., S.B.S., M.W.P., M.P., L.A.B. implemented the study; L.N. and M.B. performed cloning and sequencing; I.S., C.L. coordinated sample processing; T.H. performed ELISA assays; and R.J.G. performed single copy assays. T.K. was responsible for 3BNC117 manufacture and provided regulatory guidance; J.F.S., B.D.W. contributed to study design and helped with the manuscript; R.M.G. contributed to study design; and G.F. and S.J.S. contributed to study design and implementation. M.C.N. planned and implemented the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Mehandru S, et al. Adjunctive passive immunotherapy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals treated with antiviral therapy during acute and early infection. Journal of virology. 2007;81:11016–11031. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01340-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trkola A, et al. Delay of HIV-1 rebound after cessation of antiretroviral therapy through passive transfer of human neutralizing antibodies. Nat Med. 2005;11:615–622. doi: 10.1038/nm1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armbruster C, et al. Passive immunization with the anti-HIV-1 human monoclonal antibody (hMAb) 4E10 and the hMAb combination 4E10/2F5/2G12. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2004;54:915–920. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein F, et al. Antibodies in HIV-1 vaccine development and therapy. Science. 2013;341:1199–1204. doi: 10.1126/science.1241144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West AP, Jr, et al. Structural insights on the role of antibodies in HIV-1 vaccine and therapy. Cell. 2014;156:633–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein F, et al. HIV therapy by a combination of broadly neutralizing antibodies in humanized mice. Nature. 2012;492:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature11604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barouch DH, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of potent neutralizing HIV-1-specific monoclonal antibodies in SHIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2013;503:224–228. doi: 10.1038/nature12744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shingai M, et al. Antibody-mediated immunotherapy of macaques chronically infected with SHIV suppresses viraemia. Nature. 2013;503:277–280. doi: 10.1038/nature12746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horwitz JA, et al. HIV-1 suppression and durable control by combining single broadly neutralizing antibodies and antiretroviral drugs in humanized mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:16538–16543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315295110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moldt B, et al. Highly potent HIV-specific antibody neutralization in vitro translates into effective protection against mucosal SHIV challenge in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:18921–18925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214785109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheid JF, et al. Sequence and Structural Convergence of Broad and Potent HIV Antibodies That Mimic CD4 Binding. Science. 2011 doi: 10.1126/science.1207227. doi: science.1207227 [pii] 10.1126/science.1207227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheid JF, et al. Broad diversity of neutralizing antibodies isolated from memory B cells in HIV-infected individuals. Nature. 2009;458:636–640. doi: 10.1038/nature07930. doi:nature07930.[pii] 10.1038/nature07930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scharf L, et al. Antibody 8ANC195 reveals a site of broad vulnerability on the HIV-1 envelope spike. Cell reports. 2014;7:785–795. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falkowska E, et al. Broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies define a glycan-dependent epitope on the prefusion conformation of gp41 on cleaved envelope trimers. Immunity. 2014;40:657–668. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein F, et al. Somatic mutations of the immunoglobulin framework are generally required for broad and potent HIV-1 neutralization. Cell. 2013;153:126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balazs AB, et al. Antibody-based protection against HIV infection by vectored immunoprophylaxis. Nature. 2012;481:81–84. doi: 10.1038/nature10660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glassman PM, Balthasar JP. Mechanistic considerations for the use of monoclonal antibodies for cancer therapy. Cancer biology & medicine. 2014;11:20–33. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nettles RE, et al. Pharmacodynamics, safety, and pharmacokinetics of BMS-663068, an oral HIV-1 attachment inhibitor in HIV-1-infected subjects. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012;206:1002–1011. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Antibody-mediated modulation of immune responses. Immunol Rev. 2010;236:265–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00910.x. doi:IMR910 [pii] 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Euler Z, et al. Cross-reactive neutralizing humoral immunity does not protect from HIV type 1 disease progression. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2010;201:1045–1053. doi: 10.1086/651144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsushita S, Yoshimura K, Ramirez KP, Pisupati J, Murakami T. Passive transfer of neutralizing mAb KD-247 reduces plasma viral load in patients chronically infected with HIV-1. AIDS. 2015;29:453–462. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao HX, et al. Co-evolution of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody and founder virus. Nature. 2013;496:469–476. doi: 10.1038/nature12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei X, et al. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature. 2003;422:307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doria-Rose NA, et al. Developmental pathway for potent V1V2-directed HIV-neutralizing antibodies. Nature. 2014;509:55–62. doi: 10.1038/nature13036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein F, et al. Enhanced HIV-1 immunotherapy by commonly arising antibodies that target virus escape variants. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2361–2372. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet. 2013;382:1525–1533. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61809-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bournazos S, et al. Broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibodies require Fc effector functions for in vivo activity. Cell. 2014;158:1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diskin R, et al. Increasing the potency and breadth of an HIV antibody by using structure-based rational design. Science. 2011;334:1289–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.1213782. doi:science.1213782 [pii] 10.1126/science.1213782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halper-Stromberg A, et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies and viral inducers decrease rebound from HIV-1 latent reservoirs in humanized mice. Cell. 2014;158:989–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou T, et al. Multidonor analysis reveals structural elements, genetic determinants, and maturation pathway for HIV-1 neutralization by VRC01-class antibodies. Immunity. 2013;39:245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Somsouk M, et al. The Immunologic Effects of Mesalamine in Treated HIV-Infected Individuals with Incomplete CD4+ T Cell Recovery: A Randomized Crossover Trial. PloS one. 2014;9:e116306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereyra F, et al. The major genetic determinants of HIV-1 control affect HLA class I peptide presentation. Science. 2010;330:1551–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1195271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montefiori DC. Evaluating neutralizing antibodies against HIV, SIV, and SHIV in luciferase reporter gene assays. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2005:11. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1211s64. Chapter 12, Unit 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li M, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env clones from acute and early subtype B infections for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. Journal of virology. 2005;79:10108–10125. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10108-10125.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van ‘t Wout AB, Schuitemaker H, Kootstra NA. Isolation and propagation of HIV-1 on peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Nature protocols. 2008;3:363–370. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laird GM, et al. Rapid quantification of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 using a viral outgrowth assay. PLoS pathogens. 2013;9:e1003398. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salazar-Gonzalez JF, et al. Deciphering human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission and early envelope diversification by single-genome amplification and sequencing. Journal of virology. 2008;82:3952–3970. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02660-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guindon S, et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Systematic biology. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.West AP., Jr Computational analysis of anti-HIV-1 antibody neutralization panel data to identify potential functional epitope residues. PNAS. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309215110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome research. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.