Optical coherence tomography in two 7-year-old girls with juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis showed the same degenerative retinal changes, despite different mutations in the CLN3 gene.

Key words: autofluorescence, Batten disease, bull's eye maculopathy, CLN3 gene, juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, macular dystrophy, optical coherence tomography, photoreceptor dystrophy, Spielmeyer-Vogt disease

Abstract

Purpose:

To report optical coherence tomography findings obtained in two patients with juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis.

Methods:

Two case reports.

Results:

Two 7-year-old girls presented with decreased visual acuity, clumsiness, night blindness, and behavioral problems. Optical coherence tomography showed an overall reduction in thickness of the central retina, as well as the outer and the inner retinal layers. The degenerative retinal changes were the same, despite different mutations in the CLN3 gene.

Conclusion:

In these rare cases of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, optical coherence tomography enabled unambiguous detection of prominent morphologic abnormalities of the retina at the patient's first presentation. The advanced stage of photoreceptor degeneration seen in our patients shows that a diagnosis can potentially be made much earlier.

Juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL; Batten disease or Spielmeyer-Vogt-Sjögren-Batten disease) is one of a group of inherited lysosomal storage diseases known as neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis is a fatal autosomal recessive, childhood-onset neurodegenerative disease caused by mutation in the ceroid lipofuscinosis three gene (CLN3) on chromosome 16. The genetic defect leads to lysosomal storage and accumulation of intracellular fluorescent material. The first symptoms occur at the age of 5 to 6 years.1 Patients present with insidious but rapidly progressive vision loss as the first symptom. A “bull's eye” type of macular degeneration appears as an early feature. Degeneration of the peripheral retina becomes more marked with time. With progression of the disease, cognitive decline, behavioral problems, and seizures appear. The average life expectancy is 15 years from the onset of symptoms.2 Treatment is symptomatic only. Here, we present optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fundus autofluorescence photography findings in two 7-year-old girls with JNCL. This has not, to the best of our knowledge, been reported before.

Case Report

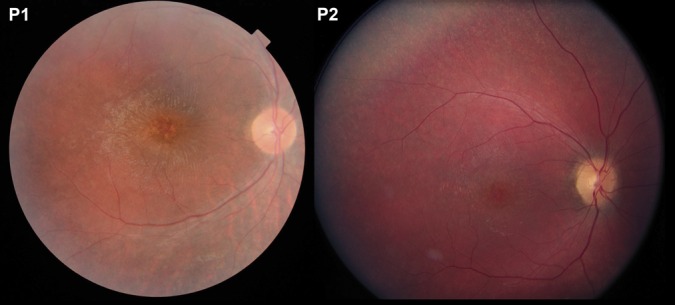

Our patients presented with decreased visual acuity, clumsiness, night blindness, and behavioral problems when they started school at the age of 6 years. The first patient was homozygous for the common 1.02 kb deletion in the CLN3 gene, and the second patient had a heterozygous deletion (c.461_677del) and a heterozygous missense mutation (c.988C>T).3 Fundus examination showed optic nerve pallor, narrow retinal vessels, and scattered mottling of the fundus pigment (Figure 1). Best-corrected visual acuity was 3/36 in both eyes in Case 1 and 1.5/60 in the right eye and 2/60 in the left eye in Case 2. Full-field electroretinography was without measurable responses under both dark-adapted and light-adapted conditions in Case 1, and it could not be obtained in Case 2.

Fig. 1.

Color fundus photographs from Patient 1 (left) and Patient 2 (right) showing thin retinal vessels, well-defined nerve fibers, a wrinkled cellophane-like macular surface, and central retinal atrophy with mottled pigmentation. A fine granular pigmentation in the peripheral retina is seen in Patient 2.

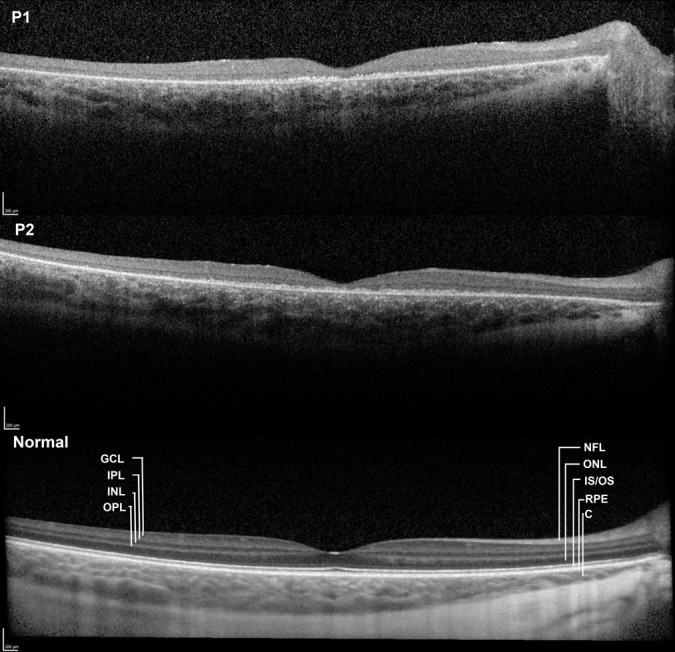

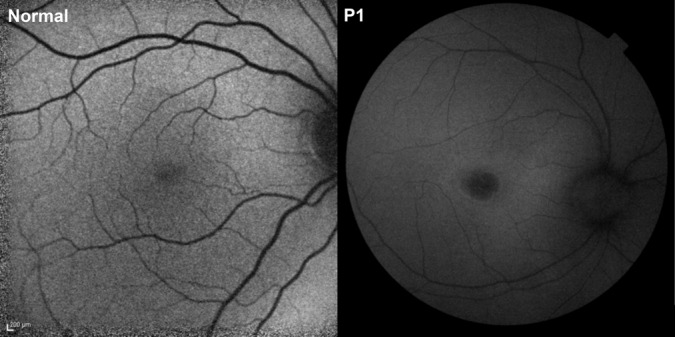

Optical coherence tomography showed an overall reduction in thickness of the central retina compared with a normal scan from an individual of the same age (Figure 2). The thickness of the outer and the inner retinal layers was markedly reduced, most prominently in the outer layer and inner segment/outer segment part of the photoreceptors layer. Multiple hyperreflective granules were seen at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium. The optical reflectivity of the inner retinal layers was abnormally homogeneous, including that of the inner nuclear layer. The choroid had a normal thickness and structure. Fundus autofluorescence imaging, available only in Patient 1, showed a relatively dark fovea and a normal or diffusely subnormal autofluorescence (Figure 3). In infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses, Levin et al4 have reported that on full-field electroretinography, inner retinal responses are compromised earlier in life than the responses generated by photoreceptors.

Fig. 2.

Horizontal transfoveal OCT scans obtained with averaging (3–10 scans) from the right eye of a 7-year-old girl with JNCL (top, Patient 1) and from the right eye of another 7-year-old girl with the same disease (middle, Patient 2). A comparable image from a healthy 7-year-old girl (below) is the product of the averaging of 30 scans. The number of scans in the two patients was limited by poor fixation. Both patients show unremarkable retinal nerve fiber layers, whereas the structures of the outer layers of the retina are severely disrupted. Assuming that the main loss of substance has occurred in the photoreceptor and retinal pigment epithelium layers, what is left of the retina may be interpreted as an isoreflective unit of the ganglion cell layer and the inner plexiform layer, which appear to be of normal combined thickness, followed by severely attenuated but distinct inner nuclear and outer plexiform layers. A thin outer nuclear layer is visible in Patient 2, but not in Patient 1, and farther out the remaining layers of the retina are reduced to a thin irregular hyperreflective layer. In Patient 1, epiretinal fibrosis is seen in the temporal macula.

Fig. 3.

Autofluorescence fundus photographs from a healthy 7-year-old girl (left) and from Patient 1 (right) with ceroid neuronal lipofuscinosis. The patient had a comparatively dark fovea and a normal or diffusely reduced autofluorescence in the rest of the fundus. Although the scale of the images is different, it is also apparent that the retinal vessels are thinner than normal in the patient.

Discussion

Our noninvasive clinical findings are largely consistent with those made using light microscopy in human ocular tissue samples and in mouse models of JNCL, with near-complete absence of the photoreceptors and outer nuclear and outer plexiform layers in combination with severe reduction of the thickness of the retinal pigment epithelium.5 In contrast to previous findings in autopsy eyes with end-stage retinal degeneration, atrophy of the optic nerve, the retinal nerve fiber layer, and the retinal ganglion cell layer were not prominent in our patients.6,7

In conclusion, OCT enabled unambiguous detection of prominent morphologic abnormalities of the retina in JNCL at the patient's first presentation. The morphology was independent of the patients' different mutations. The ability to perform OCT without pharmacological pupil dilation makes it suitable for diagnosing and monitoring retinal disease in children, including children with JNCL who have suffered severe visual loss. Fundus autofluorescence photography, however, requires pupil dilation, and the bright blue light used in this technique is less likely to be tolerated by children. In our patients, OCT abnormalities had progressed to advanced degeneration of the retinal photoreceptor layer. It is thus evident that OCT provides an early and simple means of diagnosing and monitoring retinal atrophy in JNCL. The advanced stage of photoreceptor degeneration in our two 7-year-old patients shows that a diagnosis can potentially be made much earlier. A therapeutic perspective that could motivate an earlier diagnosis does not currently exist, but the findings of this and previous reports suggest that to prevent blindness, treatment would have to be implemented much earlier than at the age of 7 years.

Footnotes

None of the authors have any financial/conflicting interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Lebrun AH, Moll-Khosrawi P, Pohl S, et al. Analysis of potential biomarkers and modifiers genes affecting the clinical course of CLN3 disease. Mol Med 2011;17:1253–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams HR, Rose K, Augustine EF, et al. Experience, knowledge, and opinions about childhood genetic testing in Batten disease. Mol Genet Metab 2014;111:197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eksandh L, Ponjavic VB, Munroe PB, et al. Full-field ERG in patients with Batten/Spielmeyer-Vogt disease caused by mutations in the CLN3 gene. Ophthalmic Genet 2000;21:69–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levin SV, Baker EH, Zein WN, et al. Oral cysteamine bitartrate and N-acetylcysteine for patients with infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: a pilot study. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:777–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groh J, Stadler D, Buttmann M, Martini R. Non-invasive assessment of retinal alterations in mouse models of infantile and juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis by spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2014;2:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bozorg S, Ramirez-Montealegre D, Chung M, Pearce DA. Juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL) and the eye. Surv Ophthalmol 2009;54:463–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Traboulosi EI, Green WR, Luckenback MW, de la Cruz ZC. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Ocular histopathologic and electron microscopic studies in the late infantile, juvenile, and adult forms. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1987;225:391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]