Abstract

Objective:

To measure the extent and timing of physicians' documentation of communication with patients and families regarding limitations on life-sustaining interventions, in a population cohort of adults who died within 30 days after hospitalization for ischemic stroke.

Methods:

We used the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development Patient Discharge Database to identify a retrospective cohort of adults with ischemic strokes at all California acute care hospitals from December 2006 to November 2007. Of 326 eligible hospitals, a representative sample of 39 was selected, stratified by stroke volume and mortality. Medical records of 981 admissions were abstracted, oversampled on mortality and tissue plasminogen activator receipt. Among 198 patients who died by 30 days postadmission, overall proportions and timing of documented preferences were calculated; factors associated with documentation were explored.

Results:

Of the 198 decedents, mean age was 80 years, 78% were admitted from home, 19% had mild strokes, 11% received tissue plasminogen activator, and 42% died during the index hospitalization. Preferences about at least one life-sustaining intervention were recorded on 39% of patients: cardiopulmonary resuscitation 34%, mechanical ventilation 23%, nasogastric tube feeding 10%, and percutaneous enteral feeding 6%. Most discussions occurred within 5 days of death. Greater stroke severity was associated with increased in-hospital documentation of preferences (p < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Documented discussions about limitations on life-sustaining interventions during hospitalization were low, even though this cohort died within 30 days poststroke. Improving the documentation of preferences may be difficult given the 2015 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid 30-day stroke mortality hospital performance measure that is unadjusted for patient preferences regarding life-sustaining interventions.

Thirty-day mortality in ischemic stroke is estimated to range between 13% and 15% and has come into the sights of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as a target for hospital performance measurement beginning in Fiscal Year 2015.1,2 The policy—whose purpose is to stimulate hospital quality improvement—requires reporting of 30-day mortality rates poststroke, adjusted for case mix but not stroke severity or patient preferences regarding life-sustaining interventions.3

The etiology of mortality in the acute poststroke period is multifactorial and attributed not only to the severity of the initial event and subsequent complications but also to the quality of care delivered for the stroke and its complications. Decisions to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining interventions may indicate high-quality palliative care for severe strokes in selected patients because they reflect patient and/or family preferences for limitations on life-sustaining interventions. However, these decisions may also occur following avoidable complications or poor poststroke management.4

Documentation of communication regarding one's preferences for life-sustaining interventions is important from both clinical and policy standpoints. A lack of documentation can contribute to patients receiving care that is not desired, confusion during code situations, uncertainty among the providers, and family conflict.5 Incentive-based quality measures that focus on 30-day mortality have the potential to negatively influence the elicitation of patient preferences if physicians fear these discussions, and the subsequent documentation of them, would lead to increased 30-day mortality and thus provide misleading evidence about the quality of care provided by their hospital.

In a population cohort of adults in California who had died within 30 days after ischemic stroke, we quantified the extent and timing of physicians' documentation of communication during hospitalization with patients and families regarding decisions around 5 life-sustaining interventions: cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), mechanical ventilation, nasogastric tube feeding, percutaneous enteral feeding, and dialysis.

METHODS

Sources of data and analytic sample (multilevel sampling).

Patient sampling.

We used data collected for a stroke outcomes validation study,6 the primary goal of which was to validate outcome measures for monitoring ischemic stroke care in California. The California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) Patient Discharge Database was used to identify patients with a diagnosis of ischemic stroke from December 2006 to November 2007. Ischemic stroke discharge diagnoses were captured by ICD-9-CM codes 434.xx, 436, and 437.x.7–9 Exclusion criteria included patients who were hospitalized at non–acute care hospitals or who were hospital transfers, patients who had a prior ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke (ICD-9-CM codes 430, 431, and 432.x) within 180 days of admission, and patients who were younger than 18 years, were non-California residents, did not have valid social security numbers, or had procedure-related strokes. Patients with ischemic strokes were linked to the state Death Statistical Master File to determine 30-day mortality. Between December 2006 and November 2007, 45,013 ischemic stroke cases were identified.

Hospital sampling.

After applying the exclusion criteria, 29,781 patients at 326 hospitals were eligible for the study. All 326 hospitals were invited to participate. Of those, 115 hospitals (35%) with 13,742 ischemic stroke cases expressed interest. The validation study aimed to obtain a representative sample of hospitals based on stroke case volume and unadjusted 30-day mortality. The hospitals were stratified by case volume quartile and mortality quintile, and potential hospitals were randomly selected from each volume quartile and mortality quintile. The final patient sample—that oversampled on deaths and receipt of IV tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)—was drawn from 39 hospitals. From these hospitals, chart abstractions were attempted on 1,052 charts. Because of stop flags in the abstraction tool if patients met exclusions, incomplete sections, and medical records that were unable to be linked to OSHPD data, 981 complete chart abstractions were performed by trained abstractors. Hospital characteristics were obtained from the OSHPD annual hospital reports.10

Death cohort for analysis of treatment intensity preferences.

Using the State Death Master File, we identified the patients who died within 30 days of the ischemic stroke admission. Of the 981 patients with completed chart abstractions, 198 (20%) died by 30 days. We aimed to characterize this cohort and to describe the variation in the extent and timing of documentation of preferences for life-sustaining interventions in these patients.

Chart abstraction instrument.

The chart abstraction instrument, which was modeled after the national Veteran Health Administration Office of Performance Management Stroke Study chart abstraction tool, was reorganized into 5 modules.11,12 A Health Information Technician module included the required reporting data from the OSHPD Patient Discharge Database: patient demographics, point of origin (home, residential care facility, skilled nursing/intermediate care), payment type, place of discharge, and ICD-9-CM codes. Patient race (white, black, Native American/Eskimo/Aleutian, Asian/Pacific Islander, other) and ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic) were abstracted from the medical records at the participating hospitals. These patient characteristics were included based on literature that describes disparities in end-of-life care among ethnic and racial minorities.13 An admission module included information obtained at admission: point of origin, time and date of emergency department arrival, vital signs, stroke symptoms, medical history including comorbidities, and poststroke care and complications. An NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was derived from abstraction of the medical record using a tool previously developed and validated.14 A tPA module focused on timing of symptom onset, presentation to the emergency department, and IV tPA administration. A discharge module included the discharge location or time and date of death, discharge medications, and caregiver instructions. Interrater reliability was assessed during a pilot study for the first 50 charts. Abstractor training was then modified to increase reliability.

A treatment intensity preferences module (appendix e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org) captured patients' documented orders for “do not resuscitate” or “do not intubate” and preferences for limitations on artificial nutrition and dialysis at the time of admission and within the initial 48 hours. In addition, the module documented orders or discussions in the medical record by physicians regarding life-sustaining interventions throughout the hospitalization. Any mention of these life-sustaining interventions would suffice, including in the context of a discussion of goals of care. Life-sustaining interventions include CPR, mechanical ventilation, nasogastric tube feeding, percutaneous enteral feeding, and dialysis. The module also specified whether, during the hospitalization, patients received enteral feeding or were mechanically ventilated and whether these interventions were withdrawn or withheld in anticipation of the patient's death.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The study was approved by the OSHPD Committee for Protection of Human Subjects and the University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Board. A HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) waiver was obtained.

Data analysis.

We calculated descriptive statistics (proportions, medians, interquartile ranges/25th and 75th percentiles) for the percentage of patients or families who had documented conversations with physicians regarding limitations on life-sustaining interventions during the hospital stay; the percentage who had orders for no CPR or no mechanical ventilation, or who expressed a preference for no nasogastric tube feeding, no percutaneous enteral feeding, and no dialysis within 48 hours of hospital admission; and the timing of discussions regarding life-sustaining interventions before death.

We used bivariate analyses to explore associations of patient and hospital characteristics with physician communication regarding life-sustaining interventions during the hospital stay and with limitations on life-sustaining interventions within the initial 48 hours of hospitalization. Independent variables, i.e., age, race, ethnicity, point of origin, NIHSS score, prior stroke, comorbidities, receipt of IV tPA, and hospital size, ownership, and teaching status were dichotomized. Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables. The dependent variable was documentation of any physician communication regarding life-sustaining interventions during the index hospitalization. Each of the 5 life-sustaining interventions was also assessed individually to determine whether any of the patient characteristics were associated with a discussion about a specific life-sustaining intervention. Missing patient and hospital characteristics were categorized as unknown and were not included in the exploratory analyses.

To examine the association between patient characteristics and physician communication during the hospital stay, multivariate analyses were performed using logistic regression. Two models were constructed. The first model used the independent variables that were significantly associated in the bivariate analyses with physician communication during the hospital stay. The second model included all patient characteristics, excluding race because it was highly correlated with ethnicity. SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for the analyses.

RESULTS

Descriptive profile.

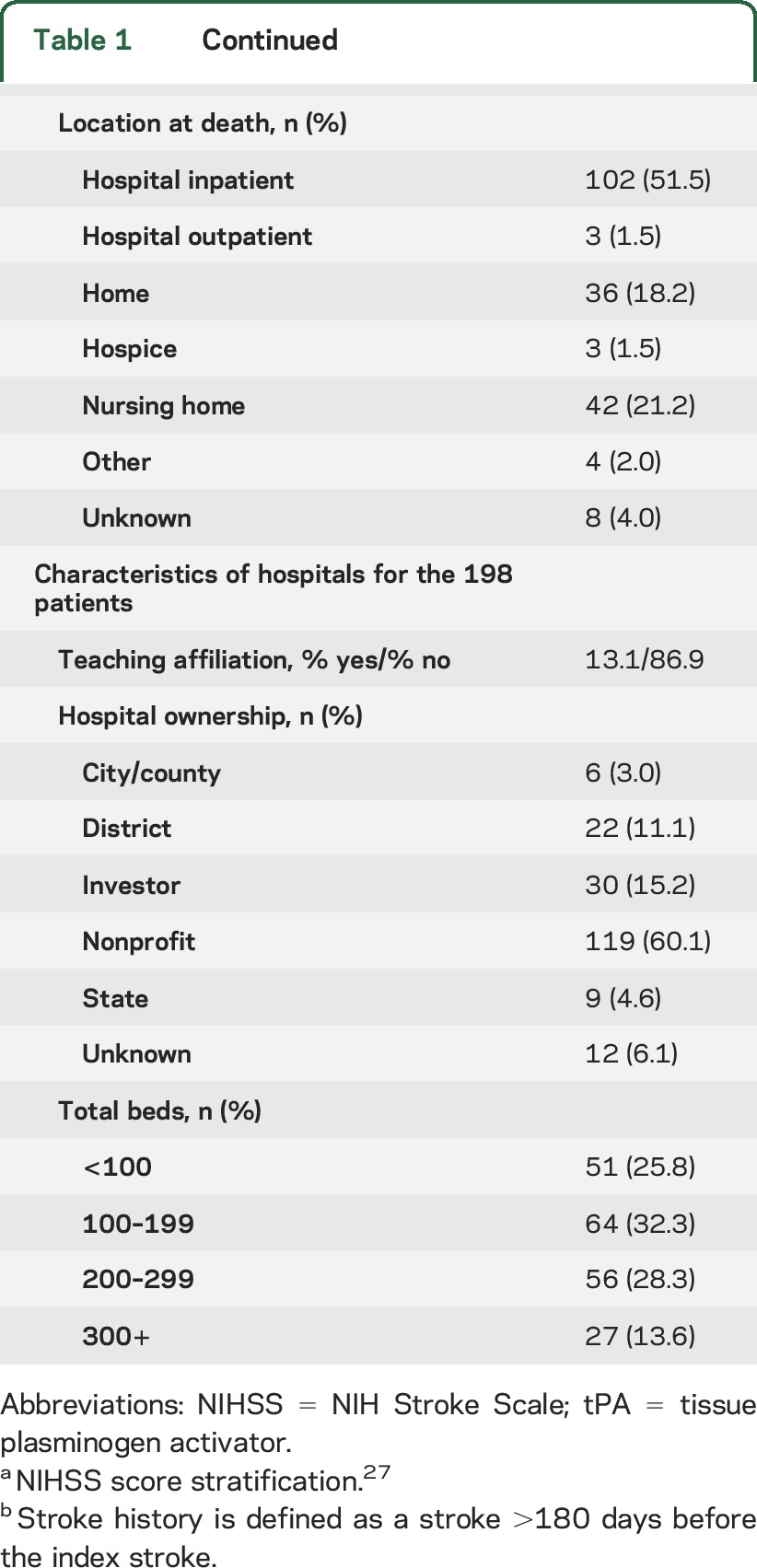

Demographic and clinical data of the 198 patients and hospital characteristics are shown in table 1. The mean age was 80 years (range 34–102), 64% were women, 79% were Caucasian, and 78% were admitted from home. Location at death was in the hospital for 51% of patients, which includes patients who were readmitted or transferred to another hospital.

Table 1.

Patient and hospital characteristics

Hospital-based documentation of physician communication regarding life-sustaining interventions among this early mortality cohort occurred in a minority of cases. Physicians documented engaging in discussions about at least one life-sustaining intervention with 39% (78 of 198) of patients and families (table 2). In a sensitivity analysis, even among those who died in the hospital or were discharged to hospice, 50% (56 of 111) had any documentation of physician communication regarding limitations on life-sustaining interventions.

Table 2.

Extent of documentation of patient preferences (n = 198)

Timing of documentation of treatment intensity preferences.

Among those who had documentation of physician communication about limitations of life-sustaining interventions, this documentation occurred at a median of 5 days before death for nasogastric tube feeding and for percutaneous enteral feeding, with even shorter median days before death for the other 3 life-sustaining interventions (table 2).

Extent of documentation of treatment intensity preferences.

At the time of admission or within 48 hours of admission, 47% (93 of 198) of the patients had documentation of their desire to forgo at least one life-sustaining intervention (table 2).

Exploratory analyses.

Among the patients who died within 30 days poststroke, there were significant associations in the bivariate analysis between 3 patient characteristics—ethnicity, point of origin, and NIHSS score—and documentation of communication with a physician about any life-sustaining intervention during the index hospitalization. Hispanics were more likely to have documentation of physician communication than non-Hispanics (odds ratio [OR] 2.86, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.07–7.62), and patients who were admitted from home were more likely to have documentation of physician communication than those not admitted from home (OR 2.15, 95% CI 1.01–4.58). Patients with less than a very severe stroke (NIHSS score 1–24) were less likely to have documentation of communication about any life-sustaining intervention than patients who had very severe strokes (NIHSS score >25) (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.20–0.80). Regarding specific life-sustaining interventions, Hispanics were more likely to have documentation of communication about CPR than non-Hispanics (OR 2.73, 95% CI 1.04–7.14), and patients with mild to severe strokes were less likely to have documentation of communication about CPR than patients with very severe strokes (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.20–0.81). There were no other significant associations between patient characteristics and documentation of physician communication about any of the specific life-sustaining interventions.

In multivariate analyses, patients with mild to severe strokes remained less likely than patients with very severe strokes to have documented physician communication regarding any life-sustaining intervention (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.21–0.93). This association was maintained when we controlled for all of the patient characteristics (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.21–0.93) as well as when we assessed for documentation of physician communication about CPR specifically (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.20–0.92). The associations between Hispanic ethnicity and documentation of physician communication, as well as home origin and documentation of physician communication, were not statistically significant in the multivariate regression models.

DISCUSSION

Among a cohort of patients who died within 30 days after an ischemic stroke, documentation of physician communication regarding life-sustaining interventions during the index hospitalization was limited. The most significant variable associated with documentation of limitations on any life-sustaining intervention, and about CPR specifically, was stroke severity. It is plausible that physicians are more comfortable initiating discussions about end-of-life care decisions in catastrophic situations or that these discussions more often lead to documented decisions to withhold life-sustaining interventions with severe strokes relative to milder ones, or both. While previous studies have demonstrated that ischemic stroke mortality is significantly influenced by withdrawing or withholding life-sustaining interventions,4,15 assessment of physician practices of eliciting and documenting patient preferences in the poststroke setting in patients who died early has been rare.

The reasons behind the lack of documentation in this study may relate to discomfort by physicians in broaching this topic, prognostic uncertainty, or patient and family unwillingness to discuss this sensitive issue.16–18 In addition, the abstraction tool captured discussions that led to decisions to place limits on specific interventions. It is possible that other discussions occurred but were either not documented or did not result in limitations being placed.

Study findings also highlight the delay in the documentation of discussions regarding patient preferences. In patients with multiple medical comorbidities including prior strokes, advance care planning should be initially addressed in the outpatient setting. Hospital admission may offer an opportunity to readdress patients' goals of care and treatment intensity preferences. In the state of California, POLST (physician orders for life-sustaining treatment) forms19 are now widely available and can also be used to indicate a patient's preferences for care in the setting of an acute or chronic illness. They also acknowledge that a physician has engaged in a relevant conversation with the patient or surrogate decision-maker.

The new CMS 30-day stroke mortality measure may stimulate improved safe and effective practices in the poststroke setting. Alternatively, it may become an additional barrier to addressing patient preferences. The consequences of the measure could manifest as a delay in initiating and documenting discussions regarding patient preferences beyond the 30-day time frame and it could influence the content shared by physicians and the manner in which they elicit patient and family preferences. The plausibility of this is supported by a study that identified an association between 30-day mortality quality measures and an increased mortality rate in cardiac surgery patients after postoperative day 30.20 In an effort to encourage better quality of care at the end of life, CMS might consider accounting for patient preferences, stroke severity, planned withdrawal of life-sustaining interventions, and hospice admissions in their model.

This study has several limitations. First, data were from a California state database, so findings may not be generalizable to patients in other states or with other demographic profiles. Second, the extent of documentation of goals of care and end-of-life care discussions relied on medical record review. These types of conversations are often difficult to locate in medical records in the absence of a standardized documentation form, and conversations that occurred between physicians and patients or families that did not result in a decision to limit life-sustaining interventions may not have been recorded in the medical record. Third, we did not have access to the posthospital documentation for patients who died outside of the hospital but within 30 days of their strokes. Fourth, we assessed the documentation of code status orders and patient preferences within the initial 48 hours of the hospitalization, which may have led to an underestimation of the number of patients who had documented limitations on life-sustaining interventions during the hospital stay. We chose this time frame because changes in code status later in the hospital course may have been secondary to poor quality care. The abstraction tool did not capture the impetus for code status change.

The majority of documented discussions occurred within the week before death. The lateness in documentation of initiating these discussions could suggest that the patients' clinical condition worsened or that their poststroke deficits did not improve, thus prompting a discussion with the patients and families. Alternatively, the impetus for these discussions may have been episodes of poor quality of care, which led to clinical deterioration. Therefore, a fifth limitation of the study was that the abstraction tool did not provide enough detail to distinguish among these possibilities.

While these data are from 2007, and there has been significant growth in palliative medicine services over the past 10 years, there remains a gap in care quality as it relates to eliciting and documenting preferences for end-of-life care, even in patients who are near the end of life.21 A recent review showed that physicians continue to be inadequately prepared to discuss preferences with patients and when the discussions occur, they are often delayed.22 Despite increased efforts to improve end-of-life care, a study assessing the quality of care that patients receive at the end of life in the inpatient setting demonstrates the insufficient and untimely documentation of goals of care conversations.23,24 The recent Institute of Medicine report on “Dying in America” emphasizes the importance of physicians initiating conversations focused on end-of-life care preferences with patients,25 and the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association released a statement on palliative and end-of-life care in stroke, which suggests that clinicians should establish goals of care and discuss patient preferences.26 Thus, our findings remain highly relevant from both a clinical and policy standpoint.

In summary, we found that less than 40% of the patients who died within 30 days after an ischemic stroke had documented discussions with their physicians during the index hospitalization about limitations on life-sustaining interventions; despite that, more than half died in the hospital or were discharged to hospice. This suggests that there is an opportunity to improve patient–physician communication, and thus the quality of palliative care in stroke, in the early poststroke period. The new CMS policy could serve as a deterrent to physician-initiated conversations regarding patient preferences for life-sustaining interventions following severe strokes. Providing a systematic way for hospitals to document patient preferences could stimulate this communication and better reflect the quality of hospital stroke care.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- CI

confidence interval

- CMS

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

- CPR

cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- NIHSS

NIH Stroke Scale

- OR

odds ratio

- OSHPD

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development

- tPA

tissue plasminogen activator

Footnotes

Editorial, page 2032

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.R.: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation, preparation and revision of the manuscript, approval of the final version. B.V.: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation, preparation and revision of the manuscript, study supervision, approval of the final version. R.H.: study concept and design, interpretation of data, revision of the manuscript, approval of the final version. K.C.: study concept and design, revision of the manuscript, approval of the final version. L.W.: study concept and design, interpretation of data, revision of the manuscript, approval of the final version. R.B.: interpretation of data, revision of the manuscript, approval of the final version. M.L.: analysis and interpretation, review of the manuscript, approval of the final version. P.P.: data management, revision of the manuscript, approval of the final version. D.Z.: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation, revision of the manuscript, study supervision, approval of the final version.

STUDY FUNDING

This study was funded by the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD), contract 08-9079, awarded to the University of California, Los Angeles. OSHPD approved the original stroke outcomes validation study as contracted work. After completion of the original contracted work and creation of the deidentified research database, OSHPD and the state of California institutional review board gave us permission to pursue the research protocol as an investigator-initiated study. Dr. Robinson's effort was also supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program at the University of California, Los Angeles.

DISCLOSURE

M. Robinson reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. B. Vickrey receives research support from the NIH (NINDS U54 NS081764), the UniHealth Foundation, and the California Community Foundation; and has been a consultant to Genentech. R. Holloway consults for MCG Guidelines (reviewer of neurology guidelines) and Neurology Today (Associate Editor); and receives grant support from the NIH (5U10NS077265 and 5 UL1 TR000042). K. Chong, L. Williams, R. Brook, M. Leng, P. Parikh, and D. Zingmond report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fonarow GC, Saver JL, Smith EE, et al. Relationship of National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale to 30-day mortality in Medicare beneficiaries with acute ischemic stroke. J Am Heart Assoc 2012;1:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reed SD, Blough DK, Meyer K, Jarvik JG. Inpatient costs, length of stay, and mortality for cerebrovascular events in community hospitals. Neurology 2001;57:305–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CMS. Center for Medicare and Medicaid 30-day stroke mortality measure. Available at: http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier3&cid=1228773321281. Accessed September 24, 2014.

- 4.Kelly AG, Hoskins KD, Holloway RG. Early stroke mortality, patient preferences, and the withdrawal of care bias. Neurology 2012;79:941–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dy S. Ensuring documentation of patients' preferences for life-sustaining treatment: brief update review. In: Making Health Care Safer II: An Updated Critical Analysis of the Evidence for Patient Safety Practices. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013. (Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 211.) Chapter 30. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK133401/. Accessed November 21, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zingmond DZ, Vickrey B, Cheng E. Ischemic stroke: outcomes validation study in California, 2006–2009. Available at: http://oshpd.ca.gov/HID/Products/PatDischargeData/Stroke/stroke2011-2012.html. Accessed June 6, 2015.

- 7.Benesch C, Witter DM, Jr, Wilder AL, Duncan PW, Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Inaccuracy of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM) in identifying the diagnosis of ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Neurology 1997;49:660–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein LB. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM coding for the identification of patients with acute ischemic stroke: effect of modifier codes. Stroke 1998;29:1602–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leibson CL, Naessens JM, Brown RD, Whisnant JP. Accuracy of hospital discharge abstracts for identifying stroke. Stroke 1994;25:2348–2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.OSHPD annual hospital financial reports. Available at: http://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/Products/Hospitals/AnnFinanData/PivotProfles/default.asp. Accessed February 23, 2015.

- 11.Arling G, Reeves M, Ross J, et al. Estimating and reporting on the quality of inpatient stroke care by Veterans Health Administration Medical Centers. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:44–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross JS, Arling G, Ofner S, et al. Correlation of inpatient and outpatient measures of stroke care quality within Veterans Health Administration hospitals. Stroke 2011;42:2269–2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1329–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams LS, Yilmaz EY, Lopez-Yunez AM. Retrospective assessment of initial stroke severity with the NIH Stroke Scale. Stroke 2000;31:858–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holloway RG, Ladwig S, Robb J, Kelly A, Nielsen E, Quill TE. Palliative care consultations in hospitalized stroke patients. J Palliat Med 2010;13:407–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO, Jr, et al. Physician factors associated with discussions about end of life. Cancer 2010;116:998–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barclay S, Momen N, Case-Upton S, Kuhn I, Smith E. End-of-life care conversations with heart failure patients: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e49–e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Momen NC, Barclay SI. Addressing “the elephant on the table”: barriers to end of life care conversations in heart failure—a literature review and narrative synthesis. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2011;5:312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.POLST California. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment. Available at: http://capolst.org/. Accessed September 30, 2014.

- 20.Maxwell BG, Wong JK, Miller DC, Lobato RL. Temporal changes in survival after cardiac surgery are associated with the thirty-day mortality benchmark. Health Serv Res 2014;49:1659–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D, et al. Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:778–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernacki RE, Block SD; American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1994–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walling AM, Asch SM, Lorenz KA, et al. The quality of care provided to hospitalized patients at the end of life. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1057–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer AE, Meeker D, Teno JM, Lynn J, Lunney JR, Lorenz KA. Symptom trends in the last year of life from 1998 to 2010: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holloway RG, Arnold RM, Creutzfeldt CJ, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care in stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:1887–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams HP, Jr, Davis PH, Leira EC, et al. Baseline NIH Stroke Scale score strongly predicts outcome after stroke: a report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST). Neurology 1999;53:126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.