SUMMARY

Background

Fiber supplements are useful, but whether a plum-derived mixed fiber that contains both soluble and insoluble fiber improves constipation is unknown.

Aim

We investigated the efficacy and tolerability of mixed fiber versus psyllium in a randomized double blind controlled trial.

Methods

Constipated patients (Rome III) received mixed fiber or psyllium, 5g bid, for 4 weeks. Daily symptoms and stool habit were assessed using stool diary. Subjects with ≥1 complete spontaneous bowel movement (CSBM)/week above baseline for ≥ 2/4 weeks were considered responders. Secondary outcome measures included stool consistency, bowel satisfaction, straining, gas, bloating, taste, dissolvability and Quality of Life (QOL).

Results

72 subjects (MF=40; psyllium=32) were enrolled and 2 from psyllium group withdrew. The mean CSBM/week increased with both mixed fiber (p<0.0001) and psyllium (p=0.0002) without group difference. There were 30 (75%) responders with mixed fiber and 24 (75%) with psyllium (p=0.9). Stool consistency increased (p=0.04), straining (p=0.006), and bloating scores decreased (p=0.02) without group differences. Significantly more patients reported improvement in flatulence (53% vs. 25%, p=0.01) and felt that mixed fiber dissolved better (p=0.02) compared to psyllium. QOL improved (p=0.0125) with both treatments without group differences.

Conclusions

Mixed fiber and psyllium were equally efficacious in improving constipation and QOL. Mixed fiber was more effective in relieving flatulence, bloating and dissolved better. Mixed fiber is effective and well tolerated.

Clinical Trial No: NCT01288508

Keywords: Constipation, fiber, treatment, quality of life, withdrawal effect

INTRODUCTION

Constipation is a common problem that affects up to 15% of the world population (1, 2). Its treatment remains challenging because nearly one half of patients surveyed remain dissatisfied with current therapies either because of lack of efficacy or safety or availability (3). Although the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recommends a gradual increase in the daily intake of fiber (4), a recent dietary survey did not recommend fiber for the treatment of constipation, because low fiber intake was not associated with constipation (5). One review that included 6 randomized controlled trials found that soluble fiber including psyllium was useful in improving constipation (6). Also soluble fiber increased the mean number of stools per week, and reduced the number of days without bowel movements. However, the benefit of insoluble fiber is unclear.

In a recent study, we showed that dried plums (prunes) that contains both soluble and insoluble fiber was significantly better than psyllium in improving bowel symptoms (7). A most recent systematic review suggested that fiber supplementation is beneficial in mild to moderate chronic constipation with fair evidence (8). However there is limited data comparing different fibers, and furthermore most studies are old and used outcome measures that were suboptimal.

Although psyllium is useful, it may cause loss of appetite and delay gastric emptying if used before meals, and some patients do not like its texture. Also, some patients report increased gas that may affect its compliance (9). Consequently, there is a need for an alternative fiber supplement with less side effects. One approach could be to use a fiber supplement that contains both soluble and insoluble fiber.

We tested the hypotheses that a plum-derived mixed fiber that contains both soluble and insoluble fiber (SupraFiber®, Sunsweet Growers Inc., CA, USA), is as effective as psyllium in the treatment of chronic constipation. Our aims were to compare the effects of mixed fiber or psyllium on bowel symptoms, in patients with chronic constipation, as well as its effects on taste, dissolvability and quality of life (QOL), in a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. We also examined the durability of fiber treatment by examining bowel symptoms for 4 weeks after completion of treatment.

METHODS

Subjects

Patients who were 18–75 years old and with symptoms of chronic constipation (Rome III) (10) were enrolled in the study. All participants reported constipation symptoms for > 3 days/month during the past three months and reported at least two of the following six symptoms with at least 25% of bowel movements: straining, lumpy or hard stool, sensation of incomplete evacuation, sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage, use of manual maneuvers, <3 bowel movements/week (10). Patients with alarming symptoms or co-morbid illnesses or active local anorectal problems, on fiber supplements, laxatives, polyethylene glycol or lubiprostone or on constipating drugs and unwilling to discontinue these medications for at least 2 weeks prior to the study were excluded. We also excluded patients with neurologic diseases and patients who were pregnant. Patients with alternating constipation and diarrhea and those with known allergy to psyllium or plums were excluded. Patients with predominant symptoms of outlet constipation were also excluded. Subjects were recruited from hospital and the community through local advertisement. The study was approved by the University of Iowa (9/17/2010), and Georgia Regents University Institutional Review Boards (12/11/2011).

Study Design

Subjects with chronic constipation who met inclusion criteria were enrolled in a double-blind randomized controlled trial. They were instructed to discontinue laxatives or prokinetics at least 1 week before enrollment and to maintain their regular lifestyle, diet and activity throughout the study. They were screened with a questionnaire and a one-week stool diary. Those who were eligible were randomized to receive four weeks of treatment with either 5g of a plum-derived mixed fiber supplement, SupraFiber® (Sunsweet Growers Inc., CA, USA) dissolved in 8 oz. of liquid or 5g of psyllium (Organic Whole Husk Psyllium, ORGANIC INDIA) dissolved in 8 oz. of liquid, both twice a day after meals. Randomization codes were generated by the biostatistician using four permuted blocks and potential participants were consecutively numbered, and their allocation to a particular compound was printed and kept in opaque sealed envelopes. After assessing eligibility, a research assistant who was not involved with the rest of the study opened the seal to ensure concealed allocation. Participants in both groups maintained a daily stool and symptom diary for four weeks of treatment. If subjects did not have a bowel movement for 3 days, they were allowed to use bisacodyl suppositories (5 g) as rescue laxative, and up to two times per week and its use was documented. After four weeks of treatment, they attended a follow-up visit. In order to assess the withdrawal effect of fiber treatment, participants maintained their stool and symptom diary for another four weeks without altering their diet and physical activity and returned for a final follow-up visit. Only rescue laxative was permitted during this period.

Measurements

A previously validated stool and symptom diary was used (11) in which participants recorded their daily bowel movements, and feelings of complete evacuation, use of digital maneuvers, stool consistency (Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS); Scale 1–7), straining effort (3-point Likert Scale: 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe) and medication(s) for stooling. Gas and bloating were rated on a 4-point Likert Scale (0= none, 1= mild, 2= moderate, 3= severe). Participants also rated their bowel satisfaction (global constipation score), as well as their feelings of satiety, post-prandial fullness, abdominal bloating or distension, and gas or flatulence on a 7-point Likert scale (markedly worse, somewhat worse, a little bit worse, not changed, a little better, somewhat better, markedly better) at the end of four weeks. Also, they rated the taste of each fiber solution, and its dissolvability and the smoothness of its texture on a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) from 0–10 (0=worst, 10= best) at the end of treatment. Participants were also asked to choose the 2 most pre-dominant bowel symptoms out of 6 possible constipation-related symptoms (straining, hard stools, feeling of incomplete evacuation, digital maneuvers, feeling of blockage, bowel movements < three per week) before starting treatment, and again at the end of four-weeks, and at subsequent follow-up visit, and to rate its change on a 7-point Likert Scale similar to the scale described above. These parameters served as secondary outcome measures. The data were extracted and analyzed by one investigator (AE) who was not involved with the study conduct.

We also assessed Quality of Life (QOL) with the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire (PAC-QOL) under four domains; worries and concerns, physical discomfort, psychosocial discomfort, and satisfaction, using 0 (Not at all/None of the time) to 4 (Extremely/All of the time), both before and at the end of four-week treatment. Additionally we assessed the psychological traits of the participants by asking them to score the Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R) under nine domains; somatization, obsessive-compulsiveness, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation.

Data Analyses and Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measure was the change in the mean complete spontaneous bowel movements per week. Responders were defined as participants who demonstrated an increase of ≥1 completes spontaneous bowel movement per week from their baseline period, and for at least two of the four weeks of treatment, and this was based on FDA draft guidelines for clinical trial assessment. (12)

Secondary outcome measures included stool consistency (Bristol Stool Form Scale), straining effort, gas and bloating symptoms. Symptom scores from the 1-week baseline period were compared with those observed during the 4th week of treatment. The participant’s rating of bowel satisfaction, and a change in the predominant symptom, as well as symptoms of satiety, flatulence, post-prandial fullness and abdominal bloating were likewise compared. The mean scores for taste and dissolvability of fiber in liquid were compared between the two treatment groups.

The treatment effects on the mean scores for the nine domains of SCL 90-R and for the four domains for PACQOL were compared.

Withdrawal effect

In order to assess the durability of fiber treatment, bowel and abdominal symptoms were assessed for another four weeks after stopping treatment, and the data from baseline, after four-week treatment, and the post-treatment periods were compared.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size calculations were based on comparing the mean number of complete spontaneous bowel movements per week between mixed fiber and psyllium, using a two-sample Poisson test. We estimated that a sample size of at least 40 subjects per treatment group was required to detect a difference of at least 1.2 in mean complete spontaneous bowel movements per week at 0.05 significance level and 80% power.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® software 9.3 (Copyright © 2013, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). An intention-to-treat analysis was performed and missing data were handled by using the last observation carried forward imputation technique. Weighted means for stool consistency and straining effort ratings were calculated for each time point (baseline, end of 4-week treatment and post-treatment period) and were compared using repeated measures ANOVA. A p value of ≤=0.05 was considered significant. The Sphericity assumption, which is required for the validity of repeated measures ANOVA was tested using Mauchly’s criterion, and when sphericity assumption was not met, the Huynh-Feldt-Lecoutre Epsilon (H-F-L) correction was used for the p-values.

A two-way repeated measures ANOVA procedure was used to analyze the mean values of gas and bloating. The nonparametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test was used to analyze the taste, and dissolvability of fiber in liquid.

Weighted Least Squares Method for Categorical Repeated Measures Data Modeling was used for symptoms that were rated on ordinal scales (7-point Likert scale). Ratings 1, 2, and 3 were combined into category 1 (condition worsening), rating 4 was coded into category 2 (no change), and ratings 5, 6, and 7 were combined into category 3 (condition improving).

SCL-90-R, PACQOL: Paired t-test as well as the nonparametric Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test were conducted to analyze the difference between the baseline and the week 4 average symptom scores and for each of the four outcome variables for PAC-QOL and nine outcome variables for SCL-90-R, and individually for each of the two treatment groups; mixed fiber and psyllium. A Bonferroni correction was made to the level of significance when multiple ANOVA procedures were performed to analyze the difference between the baseline and the week 4 average scores for each of the multiple outcome variables so as to keep the overall error rate at 0.05: p<0.0125 (p<0.05/4 domains) for PAC-QOL and p<0.0056 (p<0.05/9 domains) for SCL-90-R. To assess significance, p values of the paired t-tests were used when the assumption of normality of the differences between the average scores of baseline and week 4 was satisfied, whereas p values of the Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test were used when the assumption of normality was not satisfied.

RESULTS

Demographics and baseline stool characteristics

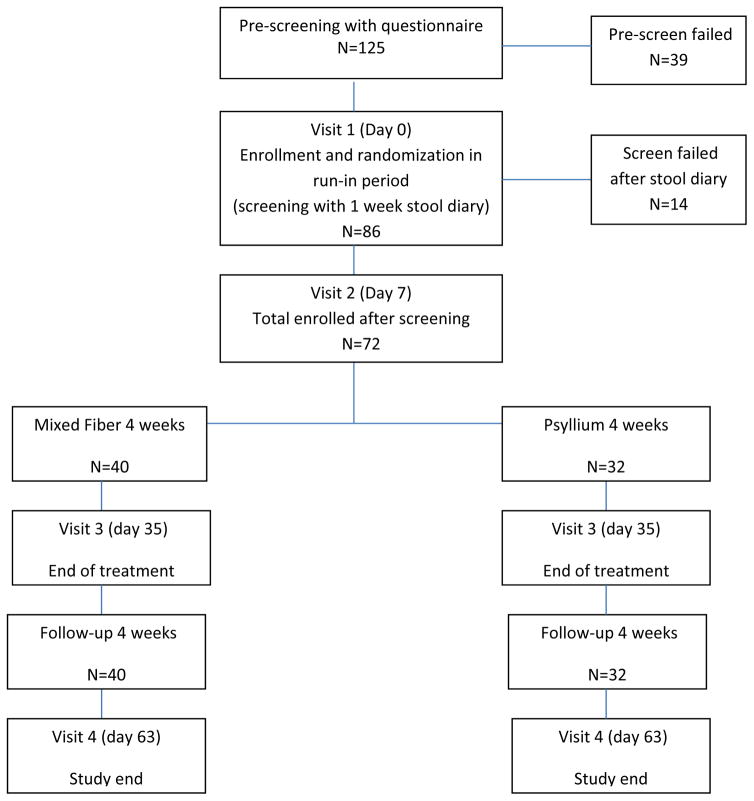

A total of 125 patients with chronic constipation were screened and 72 participants (F/M = 66/6, mean age = 42.9 years, mixed fiber = 40; psyllium = 32) were eventually enrolled (Figure 1). Two participants in the psyllium arm withdrew for personal reasons. Baseline (mean ± S.D) data for bowel habits were similar (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram showing study enrollment period and participation.

Table 1.

Effects of Mixed fiber and psyllium on stool consistency, bowel symptoms and palatability

| Mixed Fiber | psyllium | Mixed Fiber vs. psyllium (treatment) | Mixed Fiber vs. psyllium for treatment vs. baseline | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Treatment | P | Baseline | Treatment | P | P | P | |

| CSBM | 1.48 ± 1.77 | 3.45 ± 2.86 | <0.0001* | 1.47 ± 1.78 | 3.56 ± 3.24 | <0.0002* | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| BSFS (Mean±SD) | 2.68±1.04 | 2.97±1.18 | 0.0388* | 2.76±1.10 | 3.49±1.40 | 0.0124* | 0.09 | 0.4 |

| Straining effort (Mean±SD) | 1.95±0.41 | 1.64±0.46 | 0.0064* | 1.76±0.40 | 1.35±0.63 | 0.0045* | 0.03 | 0.6 |

| Bowel satisfaction‡ (%) | - | 66.7% | - | - | 62.5% | - | 0.7 | - |

| Gas (Mean±SD) | 2.12±0.88 | 1.78±0.69 | 0.0959 | 1.97±0.74 | 1.76±0.83 | 0.2361 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Bloating (Mean±SD) | 2.07±0.95 | 1.62±0.77 | 0.0022* | 1.87±0.97 | 1.47±0.95 | 0.0236* | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Smoothness of drink (Mean±SD) | - | 4.89±2.84 | - | - | 4.23±3.09 | - | 0.4 | - |

| Dissolvability of solution (Mean±SD) | - | 5.26±2.65 | - | - | 3.63±2.94 | - | 0.0248* | - |

| Gas or flatulence‡ (%) | - | 53.1% | - | - | 25.0% | - | 0.0118* | - |

| Bloating or distension‡ (%) | - | 43.8% | - | - | 25.0% | - | 0.1 | - |

| Satiety‡ (%) | - | 48.7% | - | - | 35.7% | - | 0.07 | - |

| Post-prandial fullness‡ (%) | - | 32.4% | - | - | 32.1% | - | 0.4 | - |

| Taste (Mean±SD) | - | 4.42±2.82 | - | - | 4.20±2.59 | - | 0.8 | - |

Improvement (A little better, somewhat better, markedly better),

P<0.05,

CSBM = Complete Spontaneous Bowel Movement BSFS = Bristol Stool Form Scale

Primary outcome measures

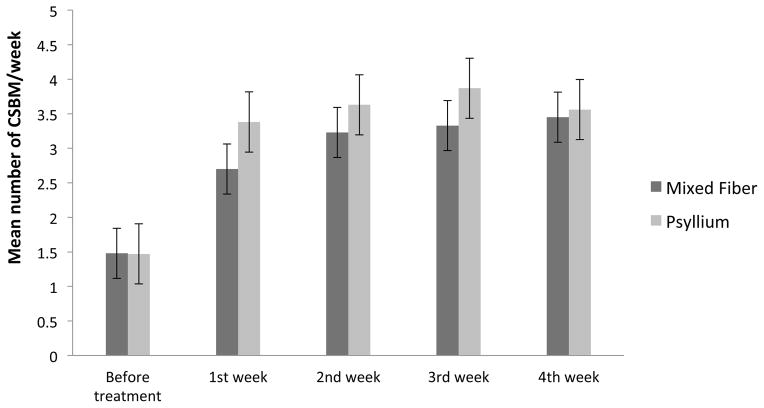

When compared to baseline, the mean number of complete spontaneous bowel movements per week increased to normal ranges with both mixed fiber (1.48± 1.77 vs 3.45± 2.86, (p<0.0001) and psyllium (1.47± 1.78 vs. 3.56± 3.24, p=0.0002) and there was no significant difference between the two groups (p=0.4) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of complete spontaneous bowel movements per week, before and after each week of treatment with mixed fiber and psyllium.

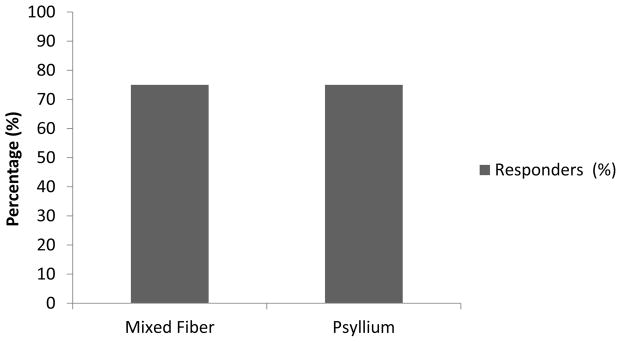

Responders

In the mixed fiber group, 30/40 (75%) patients were responders and likewise in the psyllium group, 24/32 (75%) patients were responders. There was no significant difference between the two groups (p=0.9) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of responders after treatment with mixed Fiber and psyllium.

Secondary outcome measures

Effects on stool habits

At baseline (before treatment), when comparing mixed fiber vs. psyllium the distribution of stool consistency, straining effort and other symptoms were not different (p=0.17, p=0.06, p>0.05 respectively). Comparing week-four vs. baseline for mixed fiber (2.68 vs. 2.97, p=0.04) and psyllium (2.76 vs. 3.49, p=0.01) significantly improved but there was no difference between the two groups (p=0.4) (Table 1). Likewise, the mean straining score improved significantly with both mixed fiber (1.95 vs. 1.64, p=0.0064) and psyllium (1.76 vs. 1.35, p=0.0045) but again there was no difference between the two groups (p=0.6) (Table 1). Overall, 67% of participants who received mixed fiber reported improved satisfaction with their bowel function at the end of treatment compared to 63% of patients who received psyllium, and there was no significant difference between the two groups (p=0.7) (Table 1).

Analysis of predominant symptoms

Excessive straining effort was reported as the most predominant symptom at baseline by participants in both treatment groups (45% and 64.5% respectively, Table 2). Feelings of incomplete evacuation (30.8%) and decreased stool frequency (30.8%) were reported with equal frequency as the second most bothersome symptom in the mixed fiber group, whereas hard stools (35.5%) and decreased stool frequency (35.5%) were reported in the psyllium group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency and favorable response* of predominant and second predominant symptoms for patients treated with Mixed fiber and psyllium at the end of treatment period

| Symptoms | Mixed Fiber | Psyllium | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predominant Symptom | Second predominant symptom | Predominant Symptom | Second predominant symptom | |||||

| Frequency N=40 (%) |

Favorable response*

N (%) |

Frequency N=39 (%)¶ |

Favorable response*

N (%) |

Frequency N=31 (%)¶ |

Favorable response*

N (%) |

Frequency N=31 (%)¶ |

Favorable response*

N (%) |

|

| Straining | 18 (45) | 11(68.8)§ | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 20 (64.5) | 12 (63.2)¶ | 1 (3.2) | 1 (100.0) |

| Hard stools | 9 (22.5) | 7 (77.8) | 9 (23.1) | 7 (87.5)¶ | 9 (29.0) | 8 (88.9) | 11 (35.5) | 7 (63.6) |

| Feeling of incomplete evacuation | 13 (32.5) | 10 (83.3)¶ | 12 (30.8) | 6 (50.0) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (100.0) | 8 (25.8) | 7 (100.0)¶ |

| Digital maneuvers | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0)¶ | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Feeling of blockage | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (12.8) | 3 (75.0)¶ | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| <3 bowel movements/week | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (30.8) | 9 (75.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (35.5) | 6 (54.5) |

| Change in dominant bowel symptom‡ | 75.68% | 69.4% | 70% | 70% | ||||

Improvement (Feeling a little better, somewhat better, markedly better)

1 missing frequency

2 missing frequencies

Overall, 75.7% of participants in the mixed fiber group and 70% in the psyllium group reported improvement in their most predominant symptom at the end of treatment but no difference between the groups was noted (p=0.6) (Table 2). On the other hand, 69.4% of participants in the mixed fiber group and 70% in the psyllium group reported improvement in their second most predominant symptom at the end of treatment, but there was no significant difference between the groups (p=0.7, Table 2).

Tolerability and Palatability

A significantly higher percentage of participants in the mixed fiber vs. psyllium group reported improvement in their flatulence at the end of week-four treatment (53.1 vs. 25% p=0.01) (Table 1).

Likewise, a higher percentage of participants reported improvement in their early satiety at the end of treatment with both mixed fiber and psyllium, although there was no significant difference (48.7 vs. 35.7% p=0.07) (Table 1). The percentage of participants with mixed fiber vs. psyllium who reported improvement in post-prandial fullness was also similar (32.4% vs. 32.1%, p=0.4). Although a higher percentage of participants in the mixed fiber group (43.8% vs. 25.0%) reported improvement in bloating, the difference was not significant (p=0.1) (Table 1).

Both mixed fiber (2.12±0.88 vs. 1.78±0.69, p=0.09) and psyllium (1.97±0.74 vs. 1.76±0.83, p=0.2) decreased the mean score for passing gas at the end of the treatment compared to baseline, but this was not significant, and when compared to baseline (p=0.8) (Table 1). Mixed fiber (2.07±0.95 vs. 1.62±0.77, p=0.0022) and psyllium (1.87±0.97 vs. 1.47±0.95, p=0.0236) significantly decreased the mean score for bloating at the end of treatment compared to baseline, but there was no significant difference between the groups (p=0.7) (Table 1).

Also participants reported that mixed fiber dissolved more easily than psyllium (5.26±2.65 vs. 3.63±2.94, p=0.02) (Table 1). The mean score for taste at the end of treatment was similar between groups (4.42±2.84 and 4.20±2.59, p=0.8) (Table 1). The ease of drinking mixed fiber and psyllium was also similar (4.89±2.84 and 4.23±3.096, p=0.4) (Table 1).

Psychological traits

Psyllium significantly improved two of the domains; obsessive compulsiveness (p= 0.0016) and anxiety (p=0.0006), while mixed fiber had no effect on the psychological traits (p>0.0056). There was no significant difference in the remaining domains for either treatment and also between the two treatments.

Quality of life

Mixed fiber significantly improved the following domains; physical discomfort (p<0.0001), psychosocial discomfort (p=0.0055), and worries and concerns (p=0.0002), whereas psyllium significantly improved two domains; physical discomfort (p=0.0071) and worries and concerns (p=0.0027). There was no difference between the two groups.

Use of laxatives and adverse effects

None of the participants in either group reported treatment-related adverse effects during the study, although one participant in each arm experienced viral upper respiratory infection and urinary tract infection. One (1/32) participant in each group used rescue laxative during the baseline period, whereas 1/40 participants in the mixed fiber group and 4/32 participant in the psyllium group used rescue laxative during the treatment period.

Withdrawal effects of fiber treatment

The mean number of complete spontaneous bowel movement per week after 4 weeks of follow-up, the percentage of responders, the percentage of participants who reported improvement in their bowel satisfaction, and the mean stool consistency either decreased slightly or were unchanged, and were not significantly different from the parameters observed at the end of the treatment period in both groups (p>0.05) (Table 3). There was no significant difference between the two groups (p>0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Withdrawal Effects of Mixed fiber and psyllium on number of CSBMs, responder rates, most bothersome symptoms, bowel satisfaction and stool consistency

| Mixed Fiber | Psyllium | P Mixed Fiber vs. psyllium for follow-up vs. treatment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Treatment | Follow-up | P (Follow-up vs. Baseline) | P (Follow-up vs. Treatment) | Baseline | Treatment | Follow-up | P (Follow-up vs. Baseline) | P (Follow-up vs. Treatment) | ||

| No. of CSBM/week (Mean±SD) | 1.48±1.77 | 3.45 ±2.86 | 2.64±2.76¶ | 0.0096 | 0.06 | 1.47±1.78 | 3.56±3.24 | 3.44±2.79 | 0.0004 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Responders N (%) | - | 30 (75.0%) | 24 (62.0%) | - | 0.1 | - | 24 (75.0%) | 20 (62.5%) | - | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| BSFS (Mean±SD) | 2.68±1.04 | 2.97±1.18 | 2.93±1.08 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 2.76±1.10 | 3.49±1.40 | 3.33±1.72 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Bowel satisfaction‡ (%) | - | 66.7% | 57.0% | - | 0.2 | - | 62.5% | 54.0% | - | 0.3 | 0.9 |

Improvement (Feeling a little better, somewhat better, markedly better)

1 missing frequency

Participants in the mixed fiber group showed improvement in the predominant symptom when compared to the treatment period (p=0.0126), but not in the psyllium group (p=0.5). Only three participants in the mixed fiber group and four participants in the psyllium group reported usage of rescue laxatives during the follow-up period.

DISCUSSION

In this randomized controlled study, we found that fiber supplements are effective in improving bowel symptoms in the short term treatment of patients with mild to moderate chronic constipation. Also a fruit-based, plum-derived mixed fiber preparation was just as effective as psyllium in improving bowel symptoms. Both mixed fiber and psyllium were equally effective in increasing the number of complete spontaneous bowel movements after 4-weeks in participants with mild to moderate chronic constipation.

Our study, also used the most stringent outcome measures of any fiber trial. Using composite responder measure that included both an increase in the number of complete spontaneous bowel movements per week and for 50% of the duration of the study, we found that 75% of participants in both groups were responders. Both treatments also improved the stool consistency (looser stool), and decreased the straining effort and bloating. At least 60% of participants reported improvement in their bowel satisfaction, and in both groups. Mixed fiber was more effective in relieving gas and flatulence when compared to psyllium. Also, with regards to the dissolvability, our patients reported that mixed fiber was significantly superior to psyllium.

Because of the heterogeneity of symptoms in chronic constipation, the Rome criteria require the presence of at least two out of six symptoms to make a diagnosis of chronic constipation. Although these criteria have been used for a diagnosis of constipation and for entry into a clinical trial, little attention has been paid to which symptom(s) was most predominant in a patient with constipation, and more importantly if this symptom(s) improved at the end of treatment. For an individual patient, an improvement in their dominant symptom is clinically more meaningful than either an overall improvement or improvement in metrics such as complete spontaneous bowel movement. One study showed that a feeling of incomplete bowel movement, straining and hardness of stool were as important as decreased bowel movements in patients experiencing chronic constipation (17). Two previous studies that compared psyllium with placebo showed that psyllium improved straining and stool consistency but whether this was their predominant symptom was not assessed (14, 15). In this study, we found that excessive straining was the most predominant symptom in both groups of patients, followed by feelings of incomplete evacuation and decreased stool frequency in the mixed fiber group, and incomplete evacuation and hard stools in the psyllium group respectively. Also, in both groups approximately 70% of patients reported improvements in their predominant bowel symptoms. Thus, these fiber supplements not only demonstrated efficacy as assessed by the primary outcome measure but also with a clinically meaningful outcome measure as assessed by an improvement in their predominant symptom that primarily contributed to their bowel problem.

It is known that insoluble fibers such as inulin, bran and rye may cause more bloating and flatulence (16, 17) and sometimes this is a reason for discontinuation of treatment (8). In one study of wheat bran (insoluble fiber), bloating improved but flatulence worsened (18). Here, we found that approximately 50% of patients in the mixed fiber group reported improvement in bloating and this percentage was two-fold higher than that seen in the psyllium group. Also significantly more patients (two fold) reported improvement in flatulance with mixed fiber compared to psyllium. These findings suggest that besides relieving the common symptoms of constipation, approximately 50% of subjects may also experience improvement in the feelings of bloating and flatulence with mixed fiber treatment.

Other limitations of fiber supplementation that may cause patients to discontinue treatment include taste, smoothness (texture) of the drink and dissolvability in a solution. Our participants in both treatment arms scored the taste and smoothness of drink as moderately acceptable, and there was no difference between the two products, confirming a previous study (7). However, we found that significantly more participants reported that mixed fiber dissolved more easily in a solution than psyllium.

Whether benefits of fiber are durable after discontinuation of treatment is not known. Here, we examined this by following up our participants for another four weeks after completion of the clinical trial. We found that the beneficial effects of fiber treatment appear to persist in most patients even after four weeks, and there was no excessive use of rescue laxatives suggesting a durable effect, at least in the short term. Because constipation is generally a chronic relapsing condition, whether the beneficial effects of this short-term fiber supplementation will persist in the long term is unclear and is a limitation of our study.

Patients with chronic constipation have significant impairment in their quality of life and report psychological distress (19, 20). Although whole-wheat bran increased health-related quality of life in patients with Crohn’s Disease (21), it is not known whether fiber improves quality of life in patients with chronic constipation. We found that mixed fiber significantly improved physical discomfort, psychosocial discomfort and worries and concerns, while psyllium improved physical discomfort and worries and concerns. Psyllium also significantly improved obsessive compulsiveness and anxiety domains, while mixed fiber showed no significant change in psychological traits. Although a four-weeks trial is generally too short a period to demonstrate improvement in these domains, most scores for the psychological traits and quality of life were generally low at baseline in our participants, and hence a floor effect cannot be excluded. One limitation of our study was the absence of placebo group and participants were aware that they were receiving treatment possibly enhancing the results of treatment. The treatment duration was four weeks in our study and a study with longer treatment duration may help further to demonstrate the effects of fiber treatment.

In conclusion, a plum-derived mixed fiber and psyllium were both equally efficacious in improving constipation symptoms and quality of life using validated outcome measures. Plum-derived mixed fiber was more effective in relieving bloating and flatulence and dissolved better in a solution, and therefore is better tolerated than psyllium in the treatment of constipation.

Acknowledgments

Dr. SSC Rao was supported by NIH grant No. 2R01 KD57100-05A2.

This investigator initiated study was supported by an unrestricted grant from Sunsweet Growers Inc., CA, USA. We thank m/s Helen Smith for superb secretarial assistance

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of article: Satish S.C. Rao, MD, PhD, FACG.

Specific author contributions:

Author Contribution:

The study was conceived and designed by Satish SC Rao. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by Askin Erdogan and Yeong Yeh Lee and Enrique Coss Adame, Jessica Valestin and Meagan O’Banion as well as Enrique Coss Adame facilitated study recruitment and conduct of study. Dharma Thiruvaiyaru served as Biostatistician. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the article.

Potential competing interests: None

Portions of this were presented at ANMS 2013, Huntington Beach, California, USA (poster no: 57) and FNM 2014 Guangzhou, China (poster no: PP150)

References

- 1.Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:750–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rey E, Balboa A, Mearin F. Chronic constipation, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and constipation with pain/discomfort: similarities and differences. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:876–84. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:599–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bharucha AE, Dorn SD, et al. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:211–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markland AD, Palsson O, Goode PS, et al. Association of low dietary intake of fiber and liquids with constipation: evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:796–803. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suares NC, Ford AC. Systematic review: the effects of fibre in the management of chronic idiopathic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:895–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attaluri A, Donahoe R, Valestin J, et al. Randomised clinical trial: dried plums (prunes) vs. psyllium for constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:822–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao SS, Yu S, Fedewa A. Systematic review: dietary fibre and FODMAP-restricted diet in the management of constipation and irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1256–70. doi: 10.1111/apt.13167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiller LR. Review article: the therapy of constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:749–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meduri KBCK, Attaluri A, Valestin J, Rao SSC. Validation of a prospective stool diary for assessment of constipation. Neurogastroenetrol Motil. 2011;23:21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Guidance for industry: Irritable bowel syndrome - clinical evaluation of products for treatment. 2010 http://www.FDA.GOV/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM205269.pDf.

- 13.Ervin CM, Fehnel SE, Baird MJ, et al. Assessment of treatment response in chronic constipation clinical trials. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2014;7:191–8. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S58321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenn GC, Wilkinson PD, Lee CE, et al. A general practice study of the efficacy of Regulan in functional constipation. Br J Clin Pract. 1986;40:192–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashraf W, Park F, Lof J, et al. Effects of psyllium therapy on stool characteristics, colon transit and anorectal function in chronic idiopathic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:639–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hongisto SM, Paajanen L, Saxelin M, et al. A combination of fibre-rich rye bread and yoghurt containing Lactobacillus GG improves bowel function in women with self-reported constipation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:319–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedersen A, Sandstrom B, Van Amelsvoort JM. The effect of ingestion of inulin on blood lipids and gastrointestinal symptoms in healthy females. Br J Nutr. 1997;78:215–22. doi: 10.1079/bjn19970141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawton CL, Walton J, Hoyland A, et al. Short term (14 days) consumption of insoluble wheat bran fibre-containing breakfast cereals improves subjective digestive feelings, general wellbeing and bowel function in a dose dependent manner. Nutrients. 2013;5:1436–55. doi: 10.3390/nu5041436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao SSC, Seaton K, Miller MJ, Schulze K, Brown CK, Paulson J, Zimmerman B, et al. Psychological profiles and quality of life differ between patients with dyssynergia and those with slow transit constipation. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:441–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merkel IS, Locher J, Burgio K, et al. Physiologic and psychologic characteristics of an elderly population with chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1854–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brotherton CS, Taylor AG, Bourguignon C, et al. A high-fiber diet may improve bowel function and health-related quality of life in patients with Crohns disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2014;37:206–16. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]