Summary

An AKT inhibitor plus an antiestrogen exhibited no significant clinical activity in patients with ER+/HER2− breast cancer despite laboratory studies supporting an antitumor effect for both drugs combined. These results raise concerns about the development of AKT inhibitors in unselected patients whose tumors have unknown dependence on the PI3K/AKT pathway.

In this issue of Clinical Cancer Research, Ma and colleagues (1) report the results of a phase I trial of MK-2206, an allosteric pan-AKT inhibitor, in combination with endocrine therapy (anastrozole, fulvestrant or both) in post-menopausal patients with metastatic ER+/HER2− breast cancer. In laboratory experiments, the combination of MK-2206 with fulvestrant induced significant apoptosis in human breast cancer cells resistant to long term estrogen deprivation, an experimental intervention equivalent to treatment with aromatase inhibitors, particularly in those with either PIK3CA or PTEN mutations. Despite these preclinical findings, the authors did not observe any significant anti-tumor effect of the combination in patients. The administration of MK-2206 was limited by the development of rash and slow resolution of this toxicity, probably due to the drug’s long half-life of 60–90 hours. Despite amelioration of the rash by prednisone prophylaxis, 17% of patients discontinued treatment due to toxicities. Notably, only 20% of patients developed hyperglycemia, an on-target toxicity of PI3K pathway inhibitors and a surrogate of drug-induced inhibition of PI3K, suggesting the dose of MK-2206 used did not optimally inhibit AKT in vivo. In addition to this limitation, we propose two plausible explanations to potentially explain the discrepancy between the preclinical studies and the clinical trial: either the combination was tested in patients that were not appropriately selected and/or the drug combination was not the optimal one in order to induce an antitumor effect.

The preclinical data suggested that the combination of MK-2206 and fulvestrant would be successful in patients with tumors that are ER+, with mutations in the PI3K pathway, and refractory to prior treatment with aromatase inhibitors. The latter is consistent with reports showing that hyperactivation of the PI3K/AKT pathway confers adaptation of ER+ breast cancer cells to estrogen deprivation. In these studies, PI3K inhibitors abrogated this adaptation and/or synergized with antiestrogens in inducing an antitumor effect (2). Clinically, the benefit of adding a PI3K pathway inhibitor to endocrine therapy has also been mostly seen in patients with secondary endocrine therapy resistance (3). Relevant to this point, the patients accrued to the study discussed herein were relatively endocrine therapy-naïve: 35% of patients have not had any treatment in the metastatic setting, and 50% have not had adjuvant endocrine therapy. Further, only 23% had a reported alteration in the PI3K pathway in their tumors with only one tumor harboring an AKT mutation (E17K). Finally, small numbers of patients were included in three different treatment cohorts (MK-2206 with anastrozole [n=16], fulvestrant [n=8] or both [n=7]), making it hard to draw any conclusions about clinical outcomes.

Was MK-2206 the right AKT inhibitor? Our laboratory and others have shown that ATP-competitive (GSK690693, GDC0068, AZD5363) and allosteric antagonists of AKT (MK-2206) inhibit AKT kinase activity in dose dependent fashion as determined by phosphorylation of AKT substrates in multiple tumor cells including melanoma, breast and lung cancer (4). Vivanco et al. (5) reported a PH domain-dependent, kinase-independent function of AKT associated with cancer cell survival. In the same study a comparison of MK-2206 with the ATP-competitive inhibitors GSK690693 and GDC0068 showed that the latter induce less cell death than MK-2206 despite greater inhibition of phosphorylation of AKT substrates. This can be explained in part by structural studies demonstrating that allosteric inhibitors lock AKT in a closed conformation with its phospholipid binding site blocked by the kinase domain (6). In stark contrast, cells treated with ATP-mimetics displayed increased binding of AKT to PtdIns(3,4)P2 (PIP2) and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (PIP3) and increased localization of AKT at the plasma membrane, resulting in its hyperphosphorylation at the PDK1 site T308 and the mTORC2 site S473 (5). Thus, ATP-competitive AKT inhibitors promote membrane localization of AKT and fail to block its kinase-independent function, liabilities that may limit their effectiveness compared to allosteric inhibitors. On the other hand, other studies have shown that cancer-associated mutations like E17K-AKT1 with constitutive membrane association exhibit reduced sensitivity to allosteric inhibitors compared to ATP-competitive inhibitors (7). Putting individual pharmacological differences aside, determining which type of AKT inhibitor would be mechanistically more effective will require clinical trials focused in patients with aberrantly activated AKT and/or mutant AKT.

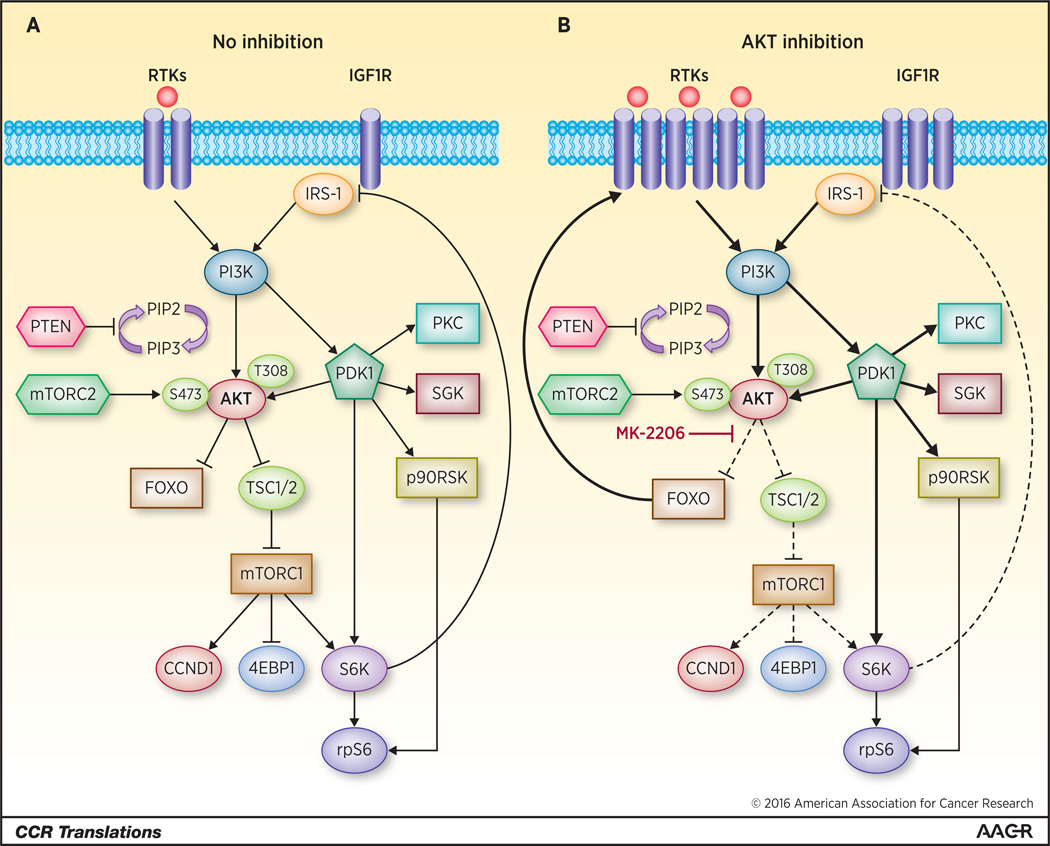

Another limitation of the use of AKT inhibitors as single drugs against tumors with aberrant PI3K signaling is that by relieving feedback inhibition of upstream signaling molecules, treatment with AKT inhibitors induces expression and phosphorylation of several receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) (8) which, in turn, activate PI3K, PDK1 and other non-AKT targets downstream (Figure 1). In ER+ breast cancer cells, there is also upregulation of ER levels and ER transcription upon therapeutic inhibition of AKT (9), supporting the combination of MK-2206 with antiestrogens in the trial discussed herein. This limitation of single agent AKT inhibitors also apply to the several drugs targeting the PI3K signaling pathway that are currently in clinic development.

Figure 1. Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway.

(A) Depiction of the pathway in steady state. Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) activation by ligand binding stimulates PI3K which converts phosphoinositide bisphosphate, PI(4,5)P2 (PIP2), to phosphoinositide trisphosphate, PI(3,4,5)P3 (PIP3), which serves as docking site for the membrane localization of PH domain-containing molecules like PDK1 and AKT. PDK1 phosphorylates AKT at T308 and mTORC2 phosphorylates AKT at S473, leading to full activation of AKT. In turn, AKT phosphorylates FOXO, thus retaining it in the cytoplasm and preventing FOXO-mediated transcription of RTKs and ER. Pathway stimulation also activates mTORC1 which represses IRS-1, thus attenuating PI3K-PDK1-AKT signaling. (B) MK-2206 inhibits both AKT and downstream mTORC1 activity. As a consequence of this, there is relief of mTORC1-dependent feedback inhibition of IGFIR/IRS-1 signaling as well as AKT-repression of FOXO with subsequent upregulation of RTKs and stimulation of PI3K, PDK1 and other non-AKT targets downstream. Thus, inhibition of the AKT node is an intrinsically incomplete approach for effective blockade of the PI3K pathway. Effective inhibition of this pathway would require blocking different nodes and alternative signaling pathways in order to achieve antitumor activity in tumors with aberrant activation of the PI3K pathway.

The BELLE-2 (NCT01610284) (10) trial compared fulvestrant plus placebo vs. fulvestrant plus the pan-PI3K inhibitor buparlisib in patients with ER+/HER2− metastatic breast cancer who had progressed on aromatase inhibitors. Patients treated with the combination of fulvestrant plus buparlisib exhibited a superior progression-free survival (PFS) compared to patients treated with fulvestrant plus placebo. This improvement was particularly significant in patients with mutant PIK3CA detected in cell-free plasma tumor DNA, suggesting the clinical benefit from PI3K inhibitors may be limited to tumors with mutational activation of PI3K. Of note, a similar population of patients with PIK3CA mutations in the BOLERO-2 trial (11) benefited from the combination of the aromatase inhibitor exemestane plus the mTORC1 inhibitor everolimus. Whether inhibition of mTORC1 and inhibition of PI3K upstream, with either pan-PI3K or PI3Kα inhibitors, are equivalent strategies against tumors with mutant PIK3CA remains to be studied.

A transforming E17K somatic mutation in the PH domain of AKT1 has been reported in breast, colorectal, lung, ovarian and endometrial cancers (12). Within ductal and lobular breast cancers, E17K-AKT1 is mutually exclusive with E545K and H1047R activating PIK3CA mutations. The transforming activity of E17K-AKT1 is apparently due to PIP3-independent recruitment to the plasma membrane while still facilitating activation by RTKs and exhibiting reduced sensitivity to AKT allosteric inhibitors. Despite its leukemogenic effect in vivo, evidence that E17K-AKT1 is an oncogenic driver and/or that generates AKT dependence in human tumors is lacking. Indeed, we are unaware of exceptional responders to AKT inhibitors among patients with E17K-AKT1 mutant tumors. However, a recent report by Hyman et al. (13) suggested a clear signal of clinical activity of the pan-AKT catalytic inhibitor AZD5363 in a phase I trial in patients with solid tumors harboring E17K-AKT1. Among 45 patients, 20 with ER+ breast cancer, 13 with gynecological tumors, and 12 with a range of other solid tumors, 37 patients exhibited tumor shrinkage; among these, there were at least seven confirmed partial responses. In 20 of 21 patients with E17K-AKT1 detectable in plasma tumor DNA, circulating mutant levels declined upon treatment with AZD5363 (13). In general, duration of response was short lived with few patients exhibiting a durable clinical response. Because of the cross-talk between AKT signaling and ER function, patients with ER+/AKT mutant breast cancer are now being treated with AZD5363 plus the ER antagonist fulvestrant.

Other initiatives similar to the above mentioned trial are in progress. The National Cancer Institute Molecular Analysis of Therapy Choice (NCI MATCH) is a large multi-arm clinical trial with the primary objective of assessing objective response and time to progression in cohorts of tumors with a similar genotype regardless of anatomical site (14). Patients with any solid tumor or lymphoma harboring the same actionable somatic mutation will be enrolled in one of several arms in MATCH using a therapy targeted to such genetic alteration. At the time of this writing, MATCH is planning an arm for patients with tumors with AKT mutations treated with AZD5363. In our opinion, genotype-specific trials like MATCH or the one above by Hyman et al. focused on AKT-mutant tumors will be required to ensure AKT inhibitors have any chance of clinical success. Because of the known mechanisms of compensation that follow inhibition of AKT, these trials should also incorporate the addition of other therapies once patients progress on single agent AKT inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

This work was supported by the NIH under the Breast Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) grant P50CA98131 (to C.L. Arteaga) and Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center Support grant P30CA68485 (to C.L. Arteaga).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ma CX, Sanchez C, Gao F, Crowder R, Naughton M, Pluard T, et al. A phase I study of the AKT inhibitor MK-2206 in combination with hormonal therapy in postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor positive metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016 Jan 18; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2160. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller TW, Hennessy BT, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Fox EM, Mills GB, Chen H, et al. Hyperactivation of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase promotes escape from hormone dependence in estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2406–2413. doi: 10.1172/JCI41680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachelot T, Bourgier C, Cropet C, Ray-Coquard I, Ferrero JM, Freyer G, et al. Randomized phase II trial of everolimus in combination with tamoxifen in patients with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer with prior exposure to aromatase inhibitors: a GINECO study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2718–2724. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thorpe LM, Yuzugullu H, Zhao JJ. PI3K in cancer: divergent roles of isoforms, modes of activation and therapeutic targeting. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:7–24. doi: 10.1038/nrc3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vivanco I, Chen ZC, Tanos B, Oldrini B, Hsieh WY, Yannuzzi N, et al. A kinase-independent function of AKT promotes cancer cell survival. Elife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.03751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu WI, Voegtli WC, Sturgis HL, Dizon FP, Vigers GPA, Brandhuber BJ. Crystal structure of human AKT1 with an allosteric inhibitor reveals a new mode of kinase inhibition. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parikh C, Janakiraman V, Wu WI, Foo CK, Kljavin NM, Chaudhuri S, et al. Disruption of PH-kinase domain interactions leads to oncogenic activation of AKT in human cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:19368–19373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204384109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandarlapaty S, Sawai A, Scaltriti M, Rodrik-Outmezguine V, Grbovic-Huezo O, Serra V, et al. AKT inhibition relieves feedback suppression of receptor tyrosine kinase expression and activity. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox EM, Kuba MG, Miller TW, Davies BR, Arteaga CL. Autocrine IGF-I/insulin receptor axis compensates for inhibition of AKT in ER-positive breast cancer cells with resistance to estrogen deprivation. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R55. doi: 10.1186/bcr3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baselga J, Im S-AIH, Clemons MIY, Awada ACS, Jagiełło-Gruszfeld A, Pistilli B, et al. PIK3CA status in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) predicts efficacy of buparlisib (BUP) plus fulvestrant (FULV) in postmenopausal women with endocrine-resistant HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer (BC): first results from the randomized, phase III BELLE-2 trial [abstract]. Cancer Res; Proceedings of the Thirty-Eighth Annual CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; 2015 Dec 8–12; San Antonio, TX. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; 2016. Abstract nr S6-01. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, Burris HA, 3rd, Rugo HS, Sahmoud T, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:520–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpten JD, Faber AL, Horn C, Donoho GP, Briggs SL, Robbins CM, et al. A transforming mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain of AKT1 in cancer. Nature. 2007;448:439–444. doi: 10.1038/nature05933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyman D, Smyth L, Bedard PL, Oza A, Dean E, Armstrong A, et al. AZD5363, a catalytic pan-Akt inhibitor, in Akt1 E17K mutation positive advanced solid tumors [abstract]. Mol Cancer Ther; Proceedings of the AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference: Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics; 2015 Nov 5–9; Boston, MA. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; 2015. Abstract nr B109. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conley BA, Doroshow JH. Molecular analysis for therapy choice: NCI MATCH. Semin Oncol. 2014;41:297–299. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]