Abstract

Background

We developed a composite measure of agitation as a secondary outcome of change over time in the Citalopram for Agitation in Alzheimer's disease study (CitAD). CitAD demonstrated a positive effect of citalopram on agitation on the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale (NBRS-A). CitAD included additional agitation measures such as the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Methods

We performed principal components analyses on change in individual item of these scales for the same, original CitAD subjects.

Results

The first principal component accounted for 12.6% of the observed variance and was composed of items that appear to reflect agitation. The effect size for citalopram calculated using this component was 0.53 (95% CI 0.22 - 0.83) versus 0.32 for the NBRS-A (95% CI 0.01 - 0.62).

Conclusions

Results suggest that a composite measure of change in agitation might be more sensitive than change in a single primary agitation measure.

Keywords: agitation, Alzheimer's Disease, principal component analysis

1. Introduction

Agitation is a common and disturbing symptom in many Alzheimer Disease patients and its pharmacological treatment has often been inadequate (Antonsdottir et al. 2015). Given the prohibitive costs of additional clinical trials, the purpose of this work is to test the hypothesis that a composite measure of agitation based on a principal component analysis (PCA) of change in individual items from standard agitation measures provides more sensitivity to change after psychotropic medication treatment than a single global agitation measure. For this analysis we used data of change over time on relevant measures from the Citalopram for Agitation in Alzheimer's Disease study (CitAD; Porsteinsson et al., 2014). In prior work we found that PCAs of measures such as the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) differ depending upon whether the PCA is performed on data from a single time point or from data reflecting change in individual items over time (Brooks et al. 1993; Tinklenberg et al. 1990). The present work performs a similar analysis on measures of agitation (Porsteinsson et al. 2014).

The CitAD study demonstrated a significant positive effect of citalopram on agitation of 0.93 points on the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale agitation subscale (NBRS-A: p = 0.04; Cohen's d = 0.32; possible range of scores: 0-18 points; Levin et al. 1987). The original study included secondary measures of agitation such as the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI; Cohen-Mansfield 1996) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI; Cummings et al. 1994), thus providing the opportunity to perform PCAs on change on all relevant individual items of these scales over the course of the study. This allows the possibility of determining if there are candidate composite measures that might be more sensitive to change after psychotropic medication treatment than the single CitAD primary agitation measure, the NBRS-A.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants in CitAD had a diagnosis of AD with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) Agitation/Aggression subscale rated as occurring 1) very frequently, or 2) frequently marked moderate or severe (Cummings et al. 1994). Primary outcome measures were 9-week change in the NBRS-A (Levin et al. 1987) and the 9-week rating on the modified Alzheimer Disease Cooperative Study-Clinical Global Impression of Change (mADCS-CGIC; Schneider et al. 1997). Participants received either placebo or active drug with a target dose of three pills a day (a target dose of citalopram 30 mg daily). All participants and caregivers received a psychosocial intervention as previously described (Drye et al. 2012) that involved counseling, emotional support and problem solving.

2.2 Statistics

The de-identified data set available for the CitAD study was used in these analyses. This dataset contains no protected health information (PHI), and thus provides no risk of confidentiality loss. Our criterion for determining if there were a candidate composite measure of change in agitation that might be more sensitive to treatment effects than the CitAD primary agitation measure, the NBRS-A (Levin et al. 1987), was to determine if the resulting new measure demonstrated a larger effect size on the same subjects than did the NBRS-A alone. All subjects with complete data for the CMAI (14 items) and NPI (12 items) at time of enrollment (baseline) and week 9 (end of treatment) were included in the analysis (N=167). Difference scores from end of treatment minus baseline were computed.

Standardized Scores of Individual Scale Items

The difference scores were standardized to mean = 0 and the standard deviation = 1 across all 167 subjects with complete data. Standardization allows us to compare scores across two different metrics: the CMAI and the NPI.

Principal Components Analysis

These 26 items were included in a PCA for all 167 subjects (regardless of treatment assignment). Analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (Cary, NC) using the SAS procedure PROC FACTOR (with the method=prin option). Sample size for the original effect size was calculated using the equation of Smithson (Smithson 2001).

Bootstrapping

To calculate confidence limits for calculated effect sizes of various measures of agitation, 2000 bootstrap samples were drawn from the 167 complete CitAD cases. Bootstrapping is a statistical procedure in which random sampling and replacement of items in a dataset is used to estimate how confident one is of a particular result. For each bootstrap sample in this study, effect sizes for NBRS, CMAI, and NPI were calculated by taking the difference in change scores between treatment groups and dividing by the standard deviation of those changes scores for both groups combined. For the unstandardized effect size for NPI, the items were reverse coded such that 0 = no and 1 = yes. For creation of composites with other scales, the NPI z-score was multiplied by −1 in order to be in the same direction as the other two scales. The z-score composite change score was calculated as the mean of the three individual change z-scores, which in turn were the mean z-scores for the individual items. The composite z-score effect size was then calculated in the same way as the individual unstandardized scale effect sizes. Similarly, the z-score composites were calculated from just the CMAI and NPI. A principal components analysis was performed on the standardized change scores for the CMAI and NPI items, and component scores for the first component were calculated, and again effect sizes were calculated in the standard way. Finally, confidence intervals were calculated from bootstrap samples. Effect size here is the mean effect size across the 2000 draws, and the confidence interval is constructed from the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the effect sizes from the 2000 draws. For both the original and bootstrap effect sizes, the necessary sample size was calculated assuming an independent samples t-test with .80 power and .05 alpha. This procedure was repeated for the lower and upper bounds of the confidence interval.

3. Results

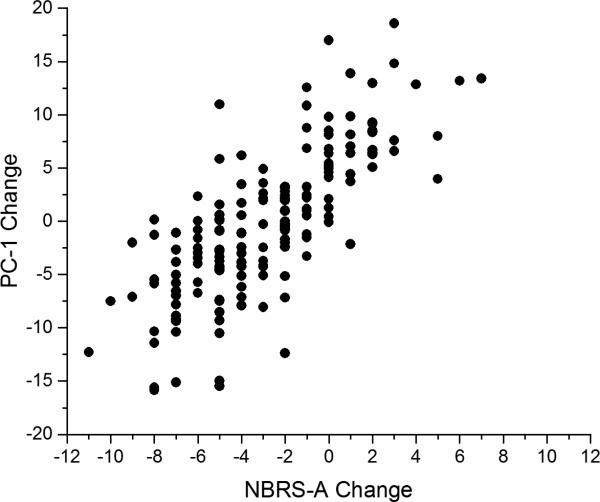

The first step in this process was to determine the PC structure of change in the 26 individual items of the CMAI and the NPI. Table 1 presents the PCs identified. Those with an Eigenvalue > 1.0 (10 PCs) accounted for a cumulative 60.0% of variance. Table 2 presents the pattern of Top 3 PCs for the 26-item PCA. Only the first three components were reported because they loaded on multiple items, whereas the additional components with an Eigenvalue > 1 were not reported as they mostly loaded on a single item. Also, to increase clarity, only factor loadings ≥ 0.40 are displayed. Table 3 presents the results of the power analyses and bootstrapping. Using the 167 subjects with complete data from the original study, we were able to calculate the 80% power of an experiment to detect the effect of citalopram on agitation with an alpha level of 0.05 using the original outcome measure (the NBRS-A). Finally, we present in Figure 1 a scatterplot demonstrating a significant relationship between the CitAD primary outcome measure (NBRS-A) and the calculated PC1 scores (Pearson r = 0.76, p < .0001).

Table 1.

Eigenvalues of the Correlation Matrix for 26-item Principal Components Analysis

| Item | Eigenvalue | Proportion of Variance | Cumulative Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.27 | 0.126 | 0.126 |

| 2 | 1.95 | 0.075 | 0.202 |

| 3 | 1.64 | 0.063 | 0.264 |

| 4 | 1.43 | 0.055 | 0.319 |

| 5 | 1.38 | 0.053 | 0.372 |

| 6 | 1.33 | 0.051 | 0.423 |

| 7 | 1.23 | 0.047 | 0.471 |

| 8 | 1.15 | 0.044 | 0.515 |

| 9 | 1.13 | 0.044 | 0.559 |

| 10 | 1.08 | 0.042 | 0.600 |

| 11 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.638 |

| 12 | 0.97 | 0.038 | 0.676 |

| 13 | 0.89 | 0.034 | 0.710 |

| 14 | 0.82 | 0.031 | 0.741 |

| 15 | 0.79 | 0.030 | 0.772 |

| 16 | 0.76 | 0.029 | 0.801 |

| 17 | 0.73 | 0.028 | 0.829 |

| 18 | 0.68 | 0.026 | 0.855 |

| 19 | 0.61 | 0.023 | 0.879 |

| 20 | 0.57 | 0.022 | 0.900 |

| 21 | 0.54 | 0.021 | 0.921 |

| 22 | 0.47 | 0.018 | 0.939 |

| 23 | 0.44 | 0.017 | 0.956 |

| 24 | 0.43 | 0.016 | 0.973 |

| 25 | 0.37 | 0.014 | 0.987 |

| 26 | 0.33 | 0.013 | 1.000 |

Table 2.

Pattern of Top 3 Principal Components for 26-item Principal Components Analysis. Only factor loadings ≥ 0.40 are displayed.

| CMAI Item (14 items) | PC-1 | PC-2 | PC-3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cursing | 0.61 | ||

| Hitting | 0.53 | ||

| Grabbing onto People | 0.52 | ||

| Other Aggressive | 0.49 | ||

| Pace | 0.46 | ||

| General Restlessness | 0.42 | ||

| Inappropriate Dress | |||

| Handling Things Inappropriately | |||

| Constant Request for Help | |||

| Repetitive Sentences | |||

| Complaining | 0.54 | ||

| Strange Noises | |||

| Hiding Things | 0.52 | ||

| Screaming |

| NPI Item (12 items) | PC-1 | PC-2 | PC-3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delusions | |||

| Hallucinations | −0.43 | 0.44 | |

| Agitation/Agression | 0.45 | ||

| Depression/Dysphoria | |||

| Anxiety | |||

| Elation/Euphoria | 0.40 | ||

| Apathy/I ndifference | 0.45 | ||

| Disinhibition | |||

| Irritability/Lability | −0.45 | ||

| Aberrant Motor Behavior | |||

| Sleep and Nighttime Disorders | |||

| Appetite and Eating Disorders | 0.49 |

Table 3.

Effect Sizes and Required Sample Sizes

| Variable | Effect Size (95% CI)1 | Sample Size | Sample Size (Lower Bound) | Sample Size (Upper Bound) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBRS-A | 0.32 (0.02, 0.64) | 310 | 80 | 78,492 |

| CMAI | 0.34 (0.04, 0.62) | 274 | 84 | 19,626 |

| NPI | 0.62 (0.31, 0.86) | 96 | 46 | 330 |

| PC-12 | 0.53 (0.10, 0.79) | 134 | 54 | 3,142 |

| Z-score 23 | 0.58 (0.28, 0.83) | 104 | 48 | 404 |

| Z-score 34 | 0.47 (0.17, 0.76) | 152 | 58 | 1,090 |

95% confidence interval based on 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of 2,000 bootstrap draws

Calculated from the first component of the principal components analysis

Calculated as the z-score from the NPI and CMAI

Calculated as the z-score from the NPI, CMAI, and NBRS-A

Yesavage Figure 1.

Scatterplot of NBRS-A change vs PC-1 change (Pearson r=0.76, p<.0001)

Plot demonstrating significant relationship between CitAD primary outcome measure (NBRS-A) and the calculated PC-1 scores.

4. Discussion

The results presented in Table 3 suggest that use of a composite outcome such as that based on PCA can lead to a more powerful and less costly study than using the NBRS-A or the CMAI as the primary outcome measure. For example, using PC-1 reflecting the factor score of the first principal component as the primary outcome measure implies a need for only a total of 134 subjects compared to 310 subjects using NBRS-A. This advantage may be due to reduced variability of scores because the PCs may include only the most reliably scored items. This approach may be of use in studies where subject recruitment is difficult, for example, in clinical trials of dementia patients with subtypes of behavioral symptoms or in studies that depend upon frequent visits and collaboration with an observing caregiver/rater. A similar approach has been used to derive a measure of executive function in dementia patients (Gibbons et al. 2012). Actigraphy in insomnia has also been used to measure agitation, especially in nursing homes.

It is interesting to note that the NPI total score might be a more sensitive measure to change under citalopram treatment than either the NBRS-A or PC-1, but the NPI is a nonspecific measure, not an agitation measure. For example, it also includes depression. Thus its total score would not be appropriate to use in a clinical trial on an anti-agitation treatment, especially when an antidepressant is used in the trial. The point of the analysis is to show that this composite measure is more sensitive to change than the single item global change measure (NBRS-A) that was the “gold standard” for agitation. The composite measure also has relatively high “face validity” as a measure of agitation, when one examines the individual items, such as cursing, hitting and irritability.

A score obtained from PCA may have the advantage of greater sensitivity to change, but does have limitations. First, because it includes several items, it may be less intuitive than a measure that is readily affixed to a single clinical description. Second, the optimal choice of PCs may vary from study to study depending on the characteristics of the study cohort. These trade-offs should be carefully considered when making the choice between an established measure of agitation and a potentially more sensitive measure requiring fewer subjects. Where appropriate, the costs, effort and time required to complete a clinical trial can be significantly reduced by use of the PCA approach. This is good for patients suffering from AD, their caregivers and society.

Highlights.

We developed a composite measure of agitation as an outcome of change over time

We performed principal components analysis

The composite agitation measure might be more sensitive than a single such measure

Acknowledgements

None

Role of funding source

This work was supported by NIA and NIMH, R01AG031348 and in part by NIH P50, AG05142 (USC, LSS). and by the Sierra-Pacific Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC) and the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The funding sources had a role in in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributions

Jerome A. Yesavage formulated the research question, wrote the first draft of the manuscript and interpreted the findings.

Jeannie-Marie S. Leoutsakos was responsible for the analysis methodology and interpretation of findings.

Joy L. Taylor, Leah Friedman, Lisa M. Kinoshita, Laura C. Lazzeroni, Mark J. Perlow and Paul B. Rosenberg contributed to critical revisions of the manuscript. Cynthia A. Munro, D.P. Devanand, Lea T. Drye, Jacobo E. Mintzer, Bruce G. Pollock, Anton P. Porsteinsson, Lon S. Schneider, David M. Shade, Daniel Weintraub, and Constantine G. Lyketsos were responsible for the supervision of the study and data collection at given site.

Art Noda conducted the data analysis, contributed to the interpretation of results and critical revisions of the manuscript.

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Antonsdottir IM, Smith J, Keltz M, Porsteinsson AP. Advancements in the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer's disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:1649–56. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.1059422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JO, 3rd, Yesavage JA, Taylor J, Friedman L, Tanke ED, Luby V, et al. Cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease: elaborating on the nature of the longitudinal factor structure of the Mini-Mental State Examination. Int Psychogeriatr. 1993;5:135–46. doi: 10.1017/s1041610293001474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J. Conceptualization of agitation: results based on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory and the Agitation Behavior Mapping Instrument. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8(Suppl 3):309–15. doi: 10.1017/s1041610297003530. discussion 351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drye LT, Ismail Z, Porsteinsson AP, Rosenberg PB, Weintraub D, Marano C, et al. Citalopram for agitation in Alzheimer's disease: design and methods. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons LE, Carle AC, Mackin RS, Harvey D, Mukherjee S, Insel P, et al. A composite score for executive functioning, validated in Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) participants with baseline mild cognitive impairment. Brain Imaging Behav. 2012;6:517–27. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9176-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin HS, High WM, Goethe KE, Sisson RA, Overall JE, Rhoades HM, et al. The neurobehavioural rating scale: assessment of the behavioural sequelae of head injury by the clinician. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1987;50:183–193. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsteinsson AP, Drye LT, Pollock BG, Devanand DP, Frangakis C, Ismail Z, et al. Effect of citalopram on agitation in Alzheimer disease: the CitAD randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:682–691. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider LS, Olin JT, Doody RS, Clark CM, Morris JC, Reisberg B, et al. Validity and reliability of the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study-Clinical Global Impression of Change. The Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(Suppl 2):S22–32. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199700112-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smithson M. Correct confidence intervals for various regression effect sizes and parameters: The importance of noncentral distributions in computing intervals. Educ Psychol Meas. 2001;61:605–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tinklenberg J, Brooks JO, 3rd, Tanke ED, Khalid K, Poulsen SL, Kraemer HC, et al. Factor analysis and preliminary validation of the mini-mental state examination from a longitudinal perspective. Int Psychogeriatr. 1990;2:123–34. doi: 10.1017/s1041610290000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]