Abstract

Objective

In middle-aged and older samples, perceived subjective socioeconomic status (SSS) is a marker of social rank that is associated with elevated inflammation and cardiovascular disease risk independent of objective indicators of socioeconomic status (oSES). Whether SSS is uniquely associated with elevated inflammation during young adulthood and whether these linkages differ by sex has not been studied using a nationally representative sample of young adults.

Methods

Data came from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. At Wave IV, young adults, aged mostly 24-32 years old, reported their SSS, oSES, and a range of covariates of both SES and elevated inflammation. Trained fieldworkers assessed medication use, body mass index, and waist circumference, and also collected bloodspots from which high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) was assayed. The sample size for the present analyses was N=13,236.

Results

Descriptive and bivariate analyses revealed a graded association between SSS and hs-CRP (b=-.072, SE=.011, p< .001): As SSS declined, mean levels of hs-CRP increased. When oSES indicators were taken into account, this association was no longer significant in women (b=-.013, SE=.019 p=.514). In men, a small but significant SSS-hs-CRP association remained after adjusting for oSES indicators and additional potential confounders of this association in the final models (b=-.034, SE=.011 p= .003; p< .001 for the sex x SSS interaction).

Conclusion

SSS is independently associated with elevated inflammation in young adults. The associations were stronger in men than in women. These data suggest that subjective, global assessments of social rank might play a role in developing adverse health outcomes.

Keywords: subjective social status, inflammation, sex differences, young adulthood, cardiovascular risk, Add Health

Objective socioeconomic status (oSES)—including years of education, occupational status, and income—is a highly robust psychosocial predictor of cardiovascular disease and mortality risk (1-6). In any layer of oSES, however, people vary considerably in their subjective social status (SSS), that is, their actual perceptions of their position in the social hierarchy. Whereas oSES focuses on objective indices only, SSS represents a global, complex summary of everyday experiences of social rank (e.g., 7). Subjective social status ratings are informed not only by oSES indicators, but also by “softer” aspects of status. These include cognitive and emotional appraisals of social standing (e.g., status among peers, neighbors, and co-workers, perceived rejection, stigma), access to privileges and resources, and projected future standing (8-12). Unsurprisingly, correlations between oSES and SSS rarely exceed the r=.30-.50 range (e.g., 3, 7, 13, 14).

Not all indicators of SES play an equal role in informing the body's response to its social environment. Notably, subjective assessments of rank may hold a key or independent role in SES-physiology associations (e.g., 9, 14). In animal models (e.g., 15), social demotion/defeat induces systemic inflammation (e.g., 16, 17). In humans, threats to social status and low social dominance rankings are associated with inabilities in maintaining homeostatic hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and immune activation (7, 9, 18-24). Indeed, in middle-aged (e.g., 14), and in some studies, older adults (e.g., 10), lower SSS is associated with higher inflammation when adjusting for oSES indicators. Thus, subjective assessments of social rank independently predict cardiovascular disease and mortality risk (e.g., 10, 12).

Subjective Social Status and Inflammation During Young Adulthood

No nationally-based study has examined associations between subjective social rank and inflammation in young adulthood. Yet this developmental period is distinctive, in part because social status is highly in flux and of heightened salience (e.g., 25). Many educational and career milestones of the young adult years involve social rankings, including admission to post-secondary education and vocational training, securing jobs, and developing career trajectories (25). During this developmental period, measures of oSES (e.g., income) may not fully capture actual and projected access to resources. For example, many young people with high earnings potential have low incomes; a similar observation could be made for occupational prestige. Subjective social status during young adulthood could be particularly informative for health-related research because it draws on past, current, and expected objective and subjective experiences of social rank.

When testing SSS-inflammatory marker associations in young adults, examining sex differences is important. Levels and correlates of hs-CRP during this developmental period are partially sex-differentiated (26-28). Young women's hs-CRP levels are almost twice as high compared to males'. Females face a multitude of potentially pro-inflammatory influences, ranging from actual chronic disease processes to use of oral contraceptives and hormonal/metabolic shifts related to pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding (26, 28). Testing sex differences in SSS-inflammation associations during young adulthood is also important because social rankings—including potential for resource and earnings acquisition—are still a key element of success in securing a mate for males in U.S. society (e.g., 29, 30). Indeed, males' perceptions of social dominance appear to be more closely linked with biomarkers of social dominance such as higher testosterone (31), that are also closely linked with lower systemic inflammation (26). In contrast, associations between social dominance and such biomarkers have not consistently been documented in females (31).

The present study fills a notable gap in research by using a nationally representative U.S. sample of young adults to test associations between subjective social status and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP)—a marker of systemic inflammation and risk for future morbidity and mortality (32-34). The study also tests whether SSS-inflammation associations are stronger in young adult men than in young adult women.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

Data came from Waves I and IV of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health, see 35). Wave I of Add Health is a nationally representative sample of adolescents enrolled in middle or high school in the US in 1994. The National Quality Education Database, which lists all US high schools, provided the sampling frame. Eighty high schools were randomly selected out of all high schools with an 11th grade and at least 30 students enrolled. These 80 high schools were paired with middle schools that fed into their student body. Together, 145 schools hosted an in-school survey, yielding 90,118 student respondents in grades 7-12 in 1994.

Approximately 200 students from each school were randomly selected for in-depth in-home interviews, resulting in N=20,745 (Wave I). The only variables from Wave I used in the present analyses are subjects' race/ethnicity and parental education. Wave IV was collected when respondents were almost all between ages 24-32 years old (14 years after Wave I). Of the eligible respondents from Wave I, 93% were re-located, 80% were re-interviewed; resulting in 15,701 in-home interviews. Wave IV blood samples were obtained at the end of each interview, as described in the Add Health documentation of biomarker collection procedures (36). Dried blood spots were mailed to and assayed at the University of Washington Department of Laboratory Medicine. Add Health participants provided written informed consent for participation in all aspects of Add Health in accordance with the University of North Carolina School of Public Health Institutional Review Board guidelines.

Measures

High-sensitivity C-reactive Protein (hs-CRP)

In-depth documentation of the Add Health hs-CRP assay and quality control is available online (36). Briefly, a sandwich ELISA method was adapted from a previously published method (37). Values from dried blood spots and paired plasma samples were highly correlated (r=.98) in a cross-validation study. Intra-assay variation was 8.1% and inter-assay variation was 11%. We used a continuous, log-transformed variable of hs-CRP that included the full range of values. In follow-up sensitivity analyses, we tested all models using a log-transformed continuous hs-CRP< 10 mg/L as the outcome variable. We used this strategy because the percentage of cases with hs-CRP≥ 10 mg/L exceeds 10% in the Add Health study, and hs-CRP≥ 10 mg/L is associated with many indicators of chronic disease risk in this dataset (28).

Subjective Social Status (SSS) was measured using a 10-rung self-anchoring scale (e.g., 7). Respondents were asked the following question to gauge their position on this ladder: “Think of this ladder as representing where people stand in the United States. At the top of the ladder (step 10) are the people who have the most money and education, and the most respected jobs. At the bottom of the ladder (step 1) are the people who have the least money and education, and the least respected jobs or no job. Where would you place yourself on this ladder? Pick the number for the step that shows where you think you stand at this time in your life, relative to other people in the United States.” Higher values indicated higher status and lower values indicated lower status.

Objective Socioeconomic Status (oSES)

Subjects' educational attainment (Wave IV) was assessed on an 11-point scale (1= less than 8 th grade to 11= doctoral degree). The mean value, M=5.59, falls between completing vocational training after high school and completing some college. Subjects' household income (Wave IV) was measured as total income from all sources before taxes and deductions. Most respondents reported their household income in dollars. A few preferred to report a range; the midpoints of the indicated ranges were used for these respondents. Household income was logged for this analysis, which reduced the likelihood of a non-linear relationship between income and hs-CRP levels. Subjects' occupational prestige (Wave IV) was measured using the socioeconomic index of occupations created by Hauser and Warren (38). The index is a weighted average of occupational education and occupational earnings (for a full description for how the index is created, see 38). The mean occupational prestige score is M=38.85 (range 9.14-99.01). Finally, parental education (Wave I) was assessed from a parent/caregiver who reported on their own and the other residential parent's (when applicable) education. The highest level of education completed by either parent was coded, ranging from 0= ≤ 8th grade to 5= professional training beyond a four-year college/university degree. Child reports of parental education were substituted when parental reports were not available.

Demographics

Dummy variables coded subjects' sex (1= female) and racial/ethnic groups: White, Hispanic, Black, Asian, and other. Participants who indicated being Hispanic were coded into this category regardless of whether they indicated any other race/ethnic category.

Illness and medication use were assessed with checklists of recent and chronic health conditions, as is common in this type of field-based, epidemiological research. For self-reported diagnoses, participants were asked whether a doctor, nurse or other health care provider had ever told them that they suffered from a given condition. The subclinical symptoms scale counted whether participants reported having had a fever, night sweats, nausea or vomiting or diarrhea, blood in stool or urine, frequent urination, and skin rash or abscess in the past two weeks. The infectious/inflammatory diseases scale counted lifetime diagnosis of asthma or chronic bronchitis or emphysema, lifetime diagnosis of hepatitis C, and also gum disease, active infection, injury, acute illness, surgery, and active seasonal allergies in the past four weeks. Other illness counted self-reported diagnoses of cancer or lymphoma or leukemia, high blood cholesterol or triglycerides or lipids, high blood pressure or hypertension, high blood sugar or diabetes, heart disease, migraine headaches, epilepsy or another seizure disorder, and HIV/AIDS. Counts greater than 3 for the illness variables were collapsed to a value of “3.” The first two measures were constructed in accordance with the Add Health documentation (36). The other illness variable captured the remaining health conditions that were assessed.

Medication use was primarily recorded by interviewers from medications/containers provided by participants. A minority of participants (22%) recalled their medication use. The medication use variable indicated whether respondents were taking (1) NSAID/Salicylate medication, including in the past 24 hours, (2) Cox-2 Inhibitor, (3) Inhaled Corticosteroid, (4) Corticotropin/Glucocorticoid, (5) Antirheumatic/Antipsoriatic, or (6) Immunosuppressive medications in the past four weeks. This indicator was constructed in accordance with the Add Health documentation (36).

Health behaviors

Physical activity was assessed with 7 items that asked how many times participants had engaged in a variety of sports in the past 7 days (e.g., running, bicycling, weightlifting, soccer, football, walking). Physical activity was coded as the maximum number of times that a participant had engaged in physical activities across these items with 0=not at all to 3 ≥ 3 time or more in the past seven days. Alcohol use was assessed as the extent of drinking in the past year. Possible responses included 0= never, 1= 1 or 2 days in the past 12 months, 2= once a month or less, 3= 2 or 3 days a month, 4= 1 or 2 days a week, 5= 3 to 5 days a week, and 6= almost every day. The dichotomous past smoking variable indicated whether the subject had ever smoked. The dichotomous current smoking variable indicated whether the subject had smoked at least one cigarette/day in the past 30 days.

Adiposity-related variables were assessed by trained field interviewers. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) / height (m2). Because associations between BMI and hs-CRP have been reported to differ by sex (e.g., 26), a BMI by hs-CRP interaction was included. A squared BMI term was created in order to allow for effects of extreme obesity. BMI is typically a strong correlate of CRP, and thus typically adjusted for in analyses testing unique associations with CRP (39). Waist circumference—an additional, and perhaps better indicator of health-related adiposity—was measured in centimeters.

Variables used in sensitivity analyses

Several additional variables that could be associated with both SSS and hs-CRP were adjusted for in sensitivity analyses. Young adults reported whether they were married, or cohabiting. Depressive symptoms were measured with four indicators from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) items with adequate Cronbach's alphas as described by Peirreira (40). Items included “could not shake off the blues,” “felt depressed,” “felt happy” (reverse coded), and “felt sad” in the past week. Neuroticism was assessed using Mini-International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) items, and consisted of the simple sum with appropriate reverse coding, with Cronbach's α=.62 in the Add Health study (41, 42). A dichotomous insomnia variable indicated whether participants reported difficulties either falling asleep or staying asleep on a daily or almost-every-day basis. Self-rated health (SRH) was assessed by asking “In general, how is your health.” Possible responses were 5= excellent, 4= very good, 3= good, 2= fair, and 1= poor. A SRH by sex interaction was also tested considering that previous work using this dataset had shown that SRH was associated with hs-CRP in young adult men but not women in fully adjusted models (43). Women reported whether they were currently pregnant or taking oral contraceptives.

Analytic Strategy

Linear regression models predicted logged hs-CRP as the outcome. Model 0 tested bivariate associations between all study variables and hs-CRP. We then estimated six nested regression models predicting hs-CRP with SSS, assessing whether SSS was associated with CRP independent of oSES measures and common covariates of both SES and CRP (44). Model 1 entered the main effect of sex, and the interaction between sex and SSS, which tested whether SSS-CRP associations differed in men and women. Model 2 added oSES indicators. Model 3 added race/ethnicity indicators. The next few models added possible confounds of the SSS-CRP association: Model 4 added illness and medication use indicators, Model 5 added health behaviors, and Model 6 added obesity-related variables. All models were weighted using Add Health survey weights to adjust for unequal probabilities of selection into the initial sample and attrition between Waves I and IV. Sensitivity analyses tested whether the pattern of significant findings regarding SSS from Model 6 would remain the same when adjusting for additional variables, excluding cases with hs-CRP≥ 10 mg/L or acute illness and testing interactions among SSS, race, and sex, and also oSES and sex.

The analysis sample consisted of cases with valid sample weights (N= 14,800), non-missing for hs-CRP (N= 13,247), and non-missing for sex and race (N= 13,236). Missing values on the remaining predictors/covariates ranged from none (many of the Wave IV variables) to n=148 on BMI to n=205 on parental educational attainment to n=839 on young adults' own income. We constructed five complete data sets via multiple imputation with chained equations to address the missing data. The substantive pattern of results remained unchanged when increasing the number of imputed datasets to N=20 (45) or when using listwise deletion.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the percent of participants at each level of SSS (M=5.02, SD=1.72), demonstrating that SSS was essentially normally distributed for women and men. Mean SSS did not differ by sex. Descriptive statistics of CRP and study covariates can be found in the Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content 1.

Table 1. Weighted percentage of young adults in each category of subjective social status.

| Subjective Social Status | Overall | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=13,236 | N=6,055 | N=7,181 | |

| Weighted % | Weighted % | Weighted % | |

| [1] (“bottom of the ladder”) | 2.16 | 1.87 | 2.41 |

| [2] | 4.36 | 4.53 | 4.22 |

| [3] | 12.29 | 12.78 | 11.88 |

| [4] | 17.84 | 17.46 | 18.16 |

| [5] | 27.30 | 26.08 | 28.32 |

| [6] | 16.82 | 17.42 | 16.31 |

| [7] | 12.19 | 12.54 | 11.89 |

| [8] | 4.77 | 4.91 | 4.65 |

| [9] | 1.20 | 1.19 | 1.21 |

| [10] (“people with the most money, education, and respected jobs”) | 1.08 | 1.24 | 1.00 |

SSS-oSES indicator correlations were r= .33, p< .001 for educational attainment; r= .33, p< .001 for logged household income; r= .16, p< .001 for occupational prestige; and r= .18, p< .001 for parental education.

Bivariate associations

Table 2 (Model 0) shows that a) lower SSS ratings were associated with higher levels of hs-CRP, b) female sex was associated with higher hs-CRP, and c) bivariate associations between all other covariates and hs-CRP.

Table 2. Associations of subjective social status, objective social status, and all other study variables (race/ethnicity, health conditions and medication use, health behaviors, and health-related adiposity measures) with hs-CRP (N=13,236).

| (0) | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate | SSS by Sex | Objective SES | Race/ Ethnicity | Illness/ Medication Use | Health Behaviors | Obesity | |

| 0. Subjective Social Status | |||||||

| SSS | -0.072*** | -0.093*** | -0.067*** | -0.067*** | -0.060*** | -0.059*** | -0.055*** |

| [-0.093,-0.050] | [-0.115,-0.070] | [-0.090,-0.044] | [-0.090,-0.044] | [-0.083,-0.036] | [-0.082,-0.036] | [-0.075,-0.034] | |

| 1. SSS by Sex | |||||||

| Female | 0.546*** | 0.313** | 0.307** | 0.307** | 0.231* | 0.199 | -0.180 |

| [0.484,0.609] | [0.096,0.529] | [0.092,0.523] | [0.094,0.520] | [0.017,0.446] | [-0.015,0.412] | [-0.475,0.116] | |

| SSS by Sex | 0.080*** | 0.047* | 0.050* | 0.050* | 0.055** | 0.054** | 0.085*** |

| [0.069,0.092] | [0.006,0.087] | [0.010,0.090] | [0.010,0.089] | [0.015,0.095] | [0.016,0.093] | [0.051,0.118] | |

| 2. Objective Social Status | |||||||

| Subject Educational | -0.056*** | -0.044*** | -0.041*** | -0.041*** | -0.038*** | -0.018 | |

| Attainment | [-0.074,0.037] | [-0.065,-0.023] | [-0.062,-0.020] | [-0.061,-0.020] | [-0.059,-0.018] | [-0.036,0.000] | |

| Subject Logged | -0.108*** | -0.013 | -0.002 | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.005 | |

| Household Income | [-0.148,-0.068] | [-0.057,0.032] | [-0.049,0.044] | [-0.039,0.054] | [-0.036,0.058] | [-0.032,0.043] | |

| Subject Occupational | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Prestige | [-0.002,0.002] | [-0.001,0.003] | [-0.001,0.003] | [-0.001,0.003] | [-0.001,0.003] | [-0.001,0.003] | |

| Parental Educational | -0.106*** | -0.065*** | -0.055*** | -0.054*** | -0.047** | -0.017 | |

| Attainment | [-0.134,-0.079] | [-0.094,-0.036] | [-0.086,-0.024] | [-0.084,-0.024] | [-0.076,-0.017] | [-0.040,0.007] | |

| 3. Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 0.210*** | 0.117* | 0.130* | 0.108* | 0.081* | ||

| [0.108,0.312] | [0.011,0.223] | [0.031,0.228] | [0.014,0.203] | [0.005,0.156] | |||

| Black | 0.175*** | 0.102 | 0.134* | 0.105* | -0.004 | ||

| [0.078,0.271] | [-0.002,0.206] | [0.029,0.239] | [0.004,0.205] | [-0.090,0.082] | |||

| Asian | -0.528*** | -0.484*** | -0.463*** | -0.487*** | -0.295*** | ||

| [-0.711,-0.345] | [-0.666,-0.302] | [-0.630,-0.295] | [-0.648,-0.326] | [-0.401,-0.189] | |||

| Other | 0.165 | 0.130 | 0.097 | 0.094 | 0.085 | ||

| [-0.074,0.405] | [-0.096,0.356] | [-0.131,0.325] | [-0.134,0.322] | [-0.078,0.249] | |||

| 4. Illness & Medication Use | |||||||

| Subclinical | 0.253*** | 0.178*** | 0.175*** | 0.179*** | |||

| [0.208,0.298] | [0.132,0.224] | [0.129,0.222] | [0.137,0.220] | ||||

| Infectious/Inflammatory | 0.116*** | 0.028 | 0.033 | 0.013 | |||

| Illness | [0.073,0.159] | [-0.018,0.074] | [-0.013,0.079] | [-0.026,0.052] | |||

| Other Illness | 0.256*** | 0.173*** | 0.165*** | 0.006 | |||

| [0.211,0.301] | [0.125,0.220] | [0.117,0.212] | [-0.031,0.043] | ||||

| Medication Use | 0.236*** | 0.114** | 0.120*** | 0.129*** | |||

| [0.162,0.308] | [0.045,0.184] | [0.052,0.189] | [0.070,0.189] | ||||

| 5. Health Behaviors | |||||||

| Physical Activity | -0.121*** | -0.078*** | -0.058*** | ||||

| [-0.150,-0.093] | [-0.160,-0.049] | [-0.082,-0.033] | |||||

| Alcohol Use | -0.083*** | -0.032*** | -0.001 | ||||

| [-0.101,-0.065] | [-0.049,-0.014] | [-0.017,0.014] | |||||

| Past Smoking | -0.009 | 0.048 | -0.066 | ||||

| [-0.083,0.065] | [-0.038,0.135] | [-0.140,0.009] | |||||

| Current Smoking | 0.008 | 0.086 | -0.015 | ||||

| [-0.063,0.080] | [-0.002,0.175] | [-0.096,0.066] | |||||

| 6. Obesity | |||||||

| Body Mass Index | 0.084*** | 0.131*** | |||||

| [0.080,0.087] | [0.109,0.153] | ||||||

| BMI by Sex | 0.028*** | 0.011*** | |||||

| [0.026,0.030] | [0.004,0.017] | ||||||

| BMI2 | 0.001*** | -0.001*** | |||||

| [0.001,0.001] | [-0.001,-0.001] | ||||||

| Waist Circumference | 0.035*** | 0.012*** | |||||

| [0.033,0.037] | [0.008,0.016] |

Data present regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (in brackets).

p< 0.050,

p< 0.010,

p < 0.001

BMI=Body Mass Index; SSS=Subjective Social Status

Adjusted models

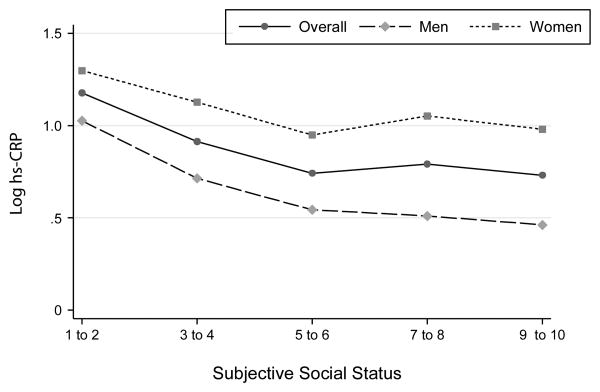

In Model 1 (“SSS by Sex Interaction”; see Table 2), a significant SSS by sex interaction emerged. Specifically, the SSS-hs-CRP association was stronger in men (b= -.093, p< .001) than in women (b= -.046, p< .001). Figure 1 shows bivariate associations between SSS and the continuous logCRP variable in the overall sample, men, and women.

Figure 1. Weighted mean levels of log hs-CRP for the overall sample, males and females across levels of subjective social status.

In Model 2 (“Objective SES”), higher subject and parental educational attainment were both independently associated with hs-CRP. Including these coefficients did not, however, account for the SSS by sex interaction. In follow-up analyses, we standardized the regression coefficients for SSS, subject education and parental education in men. Standardized betas were at -.101, -.073, and -.059, respectively. Thus, SSS was uniquely associated with hs-CRP at a level similar (or slightly higher) to that of oSES indicators. In Model 3(“Race/Ethnicity”), being Hispanic was associated with higher levels of hs-CRP and being Asian with lower levels. In Model 4 (“Illness/Medication Use”), subclinical symptoms, other illness, and medication use were all associated with higher hs-CRP. In Model 5 (“Health Behaviors”), more physical activity and more alcohol use were associated with lower levels of hs-CRP. Finally, in Model 6 (“Obesity”), all indicators of health-related adiposity (BMI, BMI2, and waist circumference) were associated with hs-CRP, as was the BMI by sex interaction. As reported in another paper, BMI was also more strongly associated with hs-CRP in women than in men in this sample (43).

Importantly, once these variables were entered into the model, the SSS by sex interaction did not diminish in size. In fact, it increased in size with the adjustment for health-related adiposity in Model 6. Tables S2 and S3 (Supplemental Digital Content 1) show results separately for men and women and further illustrate that lower subjective social status was associated with higher CRP in men in all models. In contrast, in women, SSS was associated with hs-CRP in bivariate models only. Once measures of oSES—especially parental and subject education—had been taken into account, SSS was no longer significantly associated with CRP in women.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted in order to test the robustness of the sex by SSS interaction observed in the final model. This interaction remained significant when 1) deleting cases with hs-CRP≥ 10 mg/L (Table S4, Supplemental Digital Content 1), 2) deleting cases with ≥1 acute condition (e.g., fever, night sweats, vomiting etc.), 3) deleting cases with ≥2 acute conditions, 4) adjusting for variables that coded pregnancy and use of oral contraceptives and/or deleting women who endorsed these variables, 5) testing interactions between sex and oSES variables, 6) testing interactions between sex and race, 7) including additional health behaviors (e.g., insomnia), and 8) adjusting for psychological variables that could influence ratings of SSS (e.g., neuroticism and depressive symptoms), and 9) testing models with BMI or waist circumference only. The SSS by sex interaction also did not further differ by race. Finally, we applied the Holm-Bonferroni method, which is a widely used method that is uniformly more powerful than Bonferonni corrections, to adjust p-values to address the issue of multiple testing (46). After applying these corrections, the SSS x sex correction remained significant at p < .001 in Model 6. The p-value of a few coefficients in Model 6 changed to p > .05, including being of Hispanic ethnicity (see also Table S5 in Supplemental Digital Content 1).

Assessing the size of the self-rated health effect in men

In order to gauge the effect size of the SSS-CRP association in the final model (i.e., Model 6) for men, we calculated standardized coefficients for SSS, oSES, and other common correlates of hs-CRP. The standardized coefficient for SSS in men's Model 6 was beta=-.048. Betas were .065 for medication use, .111 for subclinical disease, and .016 for inflammatory/infectious disease, respectively. Thus, effect sizes for SSS were similar in size or larger compared to prominent medical correlates of CRP. Beta was at -.052 for subject's education, and -.037 for parental education. Thus, the size of SSS-hs-CRP associations was comparable to that of subjects' educational indicators of oSES.

Discussion

Subjective perceptions of status contribute to the SES-health gradient from middle adulthood onward, even when objective measures of SES are taken into account (e.g., 7, 10, 11, 47). Social status can be in flux during key milestone of young adulthood, including the completion of post-secondary education and establishing oneself in a career and community (48). Indeed, when ranking themselves during this developmental period, young adults likely transition from primarily drawing on their (inherited) parents' social position to drawing on their own (ascribed) social position. The present analyses using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health revealed that SSS-hs-CRP associations are detectable during young adulthood, especially inmen, even with stringent controls for oSES and other measures of health behaviors and health. Thus, young adult men's lived daily experiences of social status have unique associations with a marker of risk for cardiovascular health problems.

Why is “social status syndrome” (49)—i.e., the manifestation of subjective social status in health—detectable in young adult men but not women with respect to hs-CRP? Young adult men's identities may be centered around socioeconomic hierarchies, including workplaces, as they face stereotypical societal pressures involving the establishment of careers and primary breadwinner roles. Despite changing gender roles in today's society, social status is typically still more key for successfully securing a mate for U.S. men than women (29, 30). Not surprisingly, social rankings in men are also associated with a host of other biomarkers linked to health and inflammation, including testosterone. This has not consistently been found to be the case in women (31).

In contrast, at least some young adult women may fluctuate into and out of educational and workplace settings during their childbearing years and thus exhibit greater variability in terms of what information they draw on when ranking themselves in social hierarchies. They may, for example, draw more on their parents' than their own achievements in ranking themselves (which would explain the SSS effect being accounted for with the inclusion of oSES indicators in women). Furthermore, they may draw on their partner's ranking (e.g., 50). In addition, social hierarchies beyond socioeconomic position may play an important role in women's health. Women are known to draw on “tend and befriend” strategies to ensure their own and their offsprings' survival, perhaps especially during their reproductive years (51). Thus, rankings in perceived social support, family relationship qualities, and friendship networks could play a greater role in young women's health. These types of hierarchies may be not be fully captured by the SSS ladder.

Young adult men are also exposed to fewer proinflammatory influences compared to women—many of who are exposed to oral contraceptives and hormonal and metabolic changes associated with pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding. Thus, the SSS-CRP signal may be easier to detect in young adult men than women. We could not control for all of these potentially pro-inflammatory influences on young women, however, patterns of results remained similar when we reran analyses excluding pregnant females, females using birth control, and females with very young children (who may have been nursing).

Interestingly, select studies of older adults reported reverse patterns of sex differences in SSS-CRP associations. For example, Demakakos and colleagues (2008) reported that SSS-CRP associations were present in females but not in males in fully adjusted models. It is possible that older females become more attuned to their own subjective socioeconomic standing. It is also possible that, with aging, competing proinflammatory influences decrease in females, making it easier to detect SSS-CRP associations, while proinflammatory influences in males increase as they face early manifestations of chronic disease.

What mechanisms could explain the unique contributions that SSS makes to SES “getting under the skin,” especially in young men? Because SSS is a global summary rating of social standing that likely subsumes economic and social components, a variety of mechanisms are possible (e.g., 13). In addition to actual low access to resources and privileges, males with low SSS could have a low sense of personal control and mastery, which, in turn, has been linked with poor health. They could also perceive themselves as targets of interpersonal rejection or bullying, which also has been linked to increased inflammatory levels (52). Finally, males with low SSS could perceive more stressors overall (8) and/or have poorer coping strategies for dealing with them.

Indeed, work from smaller laboratory–based studies suggests that low SSS could represent a “double-hit” for health. Subjective social status marks not only relatively chronic perceptions of low rank (and the possible health implications of such chronicity), but also more intense physiological responses to acute stressors (53), including larger short-term increases in IL-6 to acute stressful social situations (8, 53-56). Greater, repeated, and prolonged reactivity in response to perceived social threats could, in turn, contribute to long-term dysregulated immune responses captured by measures of systemic inflammation (57). Sensitivity analyses controlled for depressive symptoms and neuroticism and findings remained unchanged; thus, these two constructs are unlikely to be key mechanisms in explaining the unique associations in our final models.

Finally, our sensitivity analyses showed no evidence of SSS by race or SSS by race by sex interactions in the prediction of hs-CRP. Some studies of oSES-inflammatory marker associations found no evidence of associations or weaker associations in their African American subsample (1, 58-60). Additional research should illuminate why links between SSS and health indicators are detected in some but not in other studies of historically disadvantaged groups.

Limitations

First, this study was cross-sectional, with only one assessment of hs-CRP. Therefore, we could not test whether decreases in SSS predicted increases in systemic inflammation (“causation” hypothesis) and/or vice versa (“selection” hypothesis). Second, the Add Health study currently has data on one inflammatory marker only. Associations between SSS with other markers of immune function, including IL-6, IL-1, TNF-alpha, and white blood cell counts would be of high interest. Third, key measures of SES were self-reported. Add Health also does not verify educational attainment or income.

Implications

Despite these limitations, our study suggests that SSS has real-life ramifications for males' health above and beyond “hard” objective markers of SES (e.g., 3). Viewing oneself as lower in status appears to be a chronic stressor that also compounds stress reactivity and poor coping in response to acute stressors (7, 8). Subjective social status is likely more easily changed compared to indicators of oSES such as income and education. For example, using cognitive behavioral strategies and/or mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques, people could change their subjective perceptions of social rank and social threat, alter their physiological reactivity to such threats, and also increase positive coping strategies (e.g., 61). These strategies could in turn improve health outcomes in the long run (62).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis. Support for this analysis came from NICHD (R01 HD061622). The authors thank Kathryn Linthicum for helpful comments and edits.

Acronyms

- Add Health

National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health

- HPA

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- hs-CRP

high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- oSES

objective socioeconomic status, SSS, subjective social status

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Brummett BH, Babyak MA, Singh A, Jiang R, Williams RB, Harris KM, Siegler IC. Socioeconomic indices as independent correlates of C-reactive protein in the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:882–93. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:959–9. doi: 10.1037/a0024768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manuck SB, Phillips JE, Gianaros PJ, Flory JD, Muldoon MF. Subjective socioeconomic status and presence of the metabolic syndrome in midlife community volunteers. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:35–45. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181c484dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gimeno D, Brunner EJ, Lowe GD, Rumley A, Marmot MG, Ferrie JE. Adult socioeconomic position, C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in the Whitehall II prospective study. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;22:675–83. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawlor DA, Batty GD, Morton SM, Clark H, Macintyre S, Leon DA. Childhood socioeconomic position, educational attainment, and adult cardiovascular risk factors: The Aberdeen children of the 1950s cohort study. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1245–51. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nazmi A, Oliveira IO, Horta BL, Gigante DP, Victora CG. Lifecourse socioeconomic trajectories and C-reactive protein levels in young adults: Findings from a Brazilian birth cohort. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:1229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology. 2000;19:586–92. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derry HM, Fagundes CP, Andridge R, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Lower subjective social status exaggerates interleukin-6 responses to a laboratory stressor. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:2676–85. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemeny ME. Psychobiological responses to social threat: Evolution of a psychological model in psychoneuroimmunology. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2009;23:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demakakos P, Nazroo J, Breeze E, Marmot M. Socioeconomic status and health: The role of subjective social status. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:330–40. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh-Manoux A, Marmot MG, Adler NE. Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosom Med. 2005;67:855–61. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188434.52941.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matthews KA, Gallo LC. Psychological perspectives on pathways linking socioeconomic status and physical health. Annual review of psychology. 2011;62:501–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh-Manoux A, Adler NE, Marmot MG. Subjective social status: Its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:1321–33. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seeman M, Stein Merkin S, Karlamangla A, Koretz B, Seeman TE. Social status and biological dysregulation: The “status syndrome” and allostatic load. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;118:143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sapolsky RM. The influence of social hierarchy on primate health. Science. 2005;308:648–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1106477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stark JL, Avitsur R, Padgett DA, Campbell KA, Beck FM, Sheridan JF. Social stress induces glucocorticoid resistance in macrophages. American Journal of Physiology: Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2001;280:R1799–805. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.6.R1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avitsur R, Stark JL, Sheridan JF. Social stress induces glucocorticoid resistance in subordinate animals. Hormones and Behavior. 2001;39:247–57. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gruenewald TL, Kemeny ME, Aziz N, Fahey JL. Acute threat to the social self: Shame, social self-esteem, and cortisol activity. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:915–24. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000143639.61693.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumari M, Badrick E, Chandola T, Adler NE, Epel E, Seeman T, Kirschbaum C, Marmot MG. Measures of social position and cortisol secretion in an aging population: Findings from the Whitehall II study. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:27–34. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181c85712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webster JI, Tonelli L, Sternberg EM. Neuroendocrine regulation of immunity. Annual Review of Immunology. 2002;20:125–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.082401.104914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McEwen BS. Allostasis and allostatic load: Implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:108–24. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steptoe A, Hamer M, Chida Y. The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating inflammatory factors in humans: A review and meta-analysis. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2007;21:901–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole SW, Hawkley LC, Arevalo JM, Sung CY, Rose RM, Cacioppo JT. Social regulation of gene expression in human leukocytes. Genome Biology. 2007;8:R189. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller GE, Cohen S, Ritchey AK. Chronic psychological stress and the regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines: A glucocorticoid-resistance model. Health Psychology. 2002;21:531–41. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shanahan MJ. Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: Variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annu Rev Sociol. 2000:667–92. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shanahan L, Copeland WE, Worthman C, Erkanli A, Angold A, Costello EJ. Sex-differentiated changes in C-reactive protein from ages 9 to 21: The contributions of BMI and physical/sexual maturation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:2209–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ford ES, Giles WH, Myers GL, Rifai N, Ridker PM, Mannino DM. C-reactive protein concentration distribution among US children and young adults: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2000. Clinical Chemistry. 2003;49:1353–7. doi: 10.1373/49.8.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shanahan L, Freeman J, Bauldry S. Is very high C-reactive protein in young adults associated with indicators of chronic disease risk? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;40:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buss DM. Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1989;12:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zentner M, Mitura K. Stepping out of the caveman's shadow: Nations' gender gap predicts degree of sex differentiation in mate preferences. Psychological Science. 2012;23:1176–85. doi: 10.1177/0956797612441004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Booth A, Granger DA, Mazur A, Kivlighan KT. Testosterone and social behavior. Social Forces. 2006;85:167–91. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO, 3rd, Criqui M, Fadl YY, Fortmann SP, Hong Y, Myers GL, Rifai N, Smith SC, Jr, Taubert K, Tracy RP, Vinicor F. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;107:499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai M, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;286:327–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeh ET, Willerson JT. Coming of age of C-reactive protein: Using inflammation markers in cardiology. Circulation. 2003;107:370–1. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000053731.05365.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel EA, Hussey JM, Tabor JW, Entzel PP, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design. 2015 Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- 36.Whitsel EA, Cuthbertson CC, Tziakas DN, Power C, Wener MH, Killeya-Jones LA, Harris KM. Add Health Wave IV documentation: Measures of inflammation and immune function. 2013 Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/add-health-wave-iv-documentation-measures-of-inflammation-and-immune-function/view.

- 37.McDade T, Burhop J, Dohnal J. High-sensitivity enzyme immunoassay for C-reactive protein in dried blood spots. Clinical Chemistry. 2004;50:652–4. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.029488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hauser RM, Warren JR. Socioeconomic indexes for occupations: A review, update, and critique. Sociological Methodology. 1997;27:177–298. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kushner I, Rzewnicki D, Samols D. What does minor elevation of C-reactive protein signify? American Journal of Medicine. 2006;119(166):e17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perreira KM, Deeb-Sossa N, Harris KM, Bollen KA. What are we measuring? An evaluation of the CES-D across race/ethnicity and immigrant generation. Social Forces. 2005;83:1567–601. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baldasaro RE, Shanahan MJ, Bauer DJ. Psychometric properties of the mini-IPIP in a large, nationally representative sample of young adults. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2013;95:74–84. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2012.700466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donnellan MB, Oswald FL, Baird BM, Lucas RE. The mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:192–203. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shanahan L, Bauldry S, Freeman J, Bondy CL. Self-rated health and C-reactive protein in young adults. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2014;36:139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Connor MF, Bower JE, Cho HJ, Creswell JD, Dimitrov S, Hamby ME, Hoyt MA, Martin JL, Robles TF, Sloan EK, Thomas KS, Irwin MR. To assess, to control, to exclude: Effects of biobehavioral factors on circulating inflammatory markers. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2009;23:887–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8:206–13. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kopp M, Skrabski A, Rethelyi J, Kawachi I, Adler NE. Self-rated health, subjective social status, and middle-aged mortality in a changing society. Behavioral Medicine. 2004;30:65–70. doi: 10.3200/BMED.30.2.65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goodman E, Huang B, Schafer-Kalkhoff T, Adler NE. Perceived socioeconomic status: A new type of identity that influences adolescents' self-rated health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:479–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marmot MG. The status syndrome: How your social standing affects your health and life expectancy. New York: Henry Holt; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baxter J. Is husband's class enough? Class location and class identity in the United States, Sweden, Norway, and Australia. American Sociological Review. 1994;59:220–35. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor SE. Tend and befriend: Biobehavioral bases of affiliation under stress. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:273–7. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Copeland WE, Wolke D, Lereya ST, Shanahan L, Worthman C, Costello EJ. Childhood bullying involvement predicts low-grade systemic inflammation into adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111:7570–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323641111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dickerson SS, Gable SL, Irwin MR, Aziz N, Kemeny ME. Social-evaluative threat and proinflammatory cytokine regulation: An experimental laboratory investigation. Psychological Science. 2009;20:1237–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gianaros PJ, Horenstein JA, Hariri AR, Sheu LK, Manuck SB, Matthews KA, Cohen S. Potential neural embedding of parental social standing. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2008;3:91–6. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Slavich GM, Way BM, Eisenberger NI, Taylor SE. Neural sensitivity to social rejection is associated with inflammatory responses to social stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:14817–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009164107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME, Aziz N, Kim KH, Fahey JL. Immunological effects of induced shame and guilt. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:124–31. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097338.75454.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steptoe A, Feldman PJ, Kunz S, Owen N, Willemsen G, Marmot M. Stress responsivity and socioeconomic status: A mechanism for increased cardiovascular disease risk? European Heart Journal. 2002;23:1757–63. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gruenewald TL, Cohen S, Matthews KA, Tracy R, Seeman TE. Association of socioeconomic status with inflammation markers in black and white men and women in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69:451–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pietras SA, Goodman E. Socioeconomic status gradients in inflammation in adolescence. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:442–8. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31828b871a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pollitt RA, Kaufman JS, Rose KM, Diez-Roux AV, Zeng D, Heiss G. Early-life and adult socioeconomic status and inflammatory risk markers in adulthood. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;22:55–66. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-9082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brown-Iannuzzi JL, Adair KC, Payne BK, Richman LS, Fredrickson BL. Discrimination hurts, but mindfulness may help: Trait mindfulness moderates the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. Pers Indiv Differ. 2014;56:201–5. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Low CA, Matthews KA, Hall M. Elevated C-reactive protein in adolescents: roles of stress and coping. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:449–52. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31828d3f1d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.