Abstract

Aim

To identify factors that may serve as facilitators and barriers to self-management described by adults living with chronic illness by conducting a qualitative metasynthesis.

Background

Self-management is an individuals’ active management of a chronic illness in collaboration with their family members and clinicians.

Design

Qualitative metasynthesis.

Data Sources

We analyzed studies (N=53) published between January 2000–May 2013 that described factors affecting self-management in chronic illness as reported by adults aged over 18 years with chronic illness.

Review Methods

Sandelowsi and Barroso approach to qualitative metasynthesis: literature search; quality appraisal; analysis; and synthesis of findings.

Results

Collectively, article authors reported on sixteen chronic illnesses, most commonly diabetes (N=28) and cardiovascular disease (N=20). Participants included men and women (mean age=57, range 18–94) from twenty countries representing diverse races and ethnicities. We identified five categories of factors affecting self-management: Personal/Lifestyle Characteristics; Health Status; Resources; Environmental Characteristics; and Health Care System. Factors may interact to affect self-management and may exist on a continuum of positive (facilitator) to negative (barrier).

Conclusion

Understanding factors that influence self-management may improve assessment of self-management among adults with chronic illness and may inform interventions tailored to meet individuals’ needs and improve health outcomes.

Keywords: self-management, chronic illness, metasynthesis, review, qualitative, nursing

INTRODUCTION

Self-management includes the daily activities in which individuals engage, along with their family, community and health care professionals, to manage a chronic illness (Lorig & Holman 2003, Richard & Shea 2011). Self-management encompasses multiple domains, including management of symptoms, treatments and lifestyle changes, as well as psychosocial, cultural and spiritual consequences of health conditions (Richard & Shea 2011). Individuals’ self-management may greatly affect their quality of life and health outcomes. Self-management is a key component of the Chronic Care Model, which has been used internationally to guide clinical quality improvement initiatives (Coleman et al. 2009, McCorkle et al. 2011). The premise of this model is that self-management support that is provided in a health system by a prepared proactive team contributes to informed and activated individuals and improved outcomes (Bodenheimer et al. 2002). Thus, self-management support is a well-recognized aspect of chronic illness care.

Background

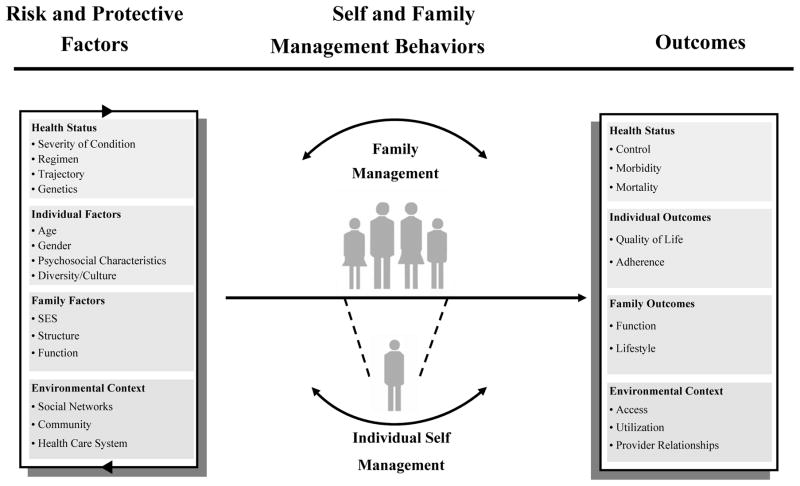

The Self- and Family Management Framework (Grey et al. 2006) was developed to illustrate relationships among risk and protective factors, self- and family management processes and health outcomes (Figure 1). In earlier work (Schulman-Green et al. 2012), we sought to deconstruct processes of self-management as broadly depicted in the Framework. Using qualitative metasynthesis techniques, we identified three main processes of self-management among adults with chronic illness: Focusing on Illness Needs; Activating Resources; and Living with a Chronic Illness. In several of these studies, factors that influenced individuals’ self-management were identified, such as depression and co-morbidities. Therefore, we sought to comprehensively identify factors influencing self-management in adults with chronic illness and to further define risk and protective factors in the Self- and Family Management Framework. While several reviews have synthesized the processes and outcomes of self-management (Barlow et al. 2002, Newman et al. 2004, Warsi et al. 2004), less is understood about factors influencing self-management from the perspective of individuals living with chronic illness. Identification of factors that affect self-management can improve assessment of self-management, can inform the development of interventions by specifying potential mediators and/or moderators of self-management behaviors or processes and may also assist individuals with chronic illness to engage in productive and sustainable self-management.

Figure 1.

Self and Family Management Framework

THE REVIEW

Aim

To identify factors that may serve as facilitators and barriers to self-management described by adults living with chronic illness by conducting a qualitative metasynthesis.

Design

Qualitative metasynthesis is an integration of findings from qualitative studies with the aim of producing theories, grand narratives, generalizations, or interpretive translations (Polit & Beck 2008). To complete this metasynthesis, we followed methodological procedures outlined by Sandelowsi and Barroso (2007): 1) literature search; 2) quality appraisal; 3) analysis of findings; and 4) synthesis of findings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Methodological Procedures for Qualitative Metasynthesis (adapted from Sandelowsi and Barroso, 2007)

| Procedure | Activities |

|---|---|

| 1. Literature search | Comprehensive, systematic search of the literature, including manual searching and selection of key articles |

| 2. Quality appraisal | Comparative appraisal and evaluation of included articles to evaluate methodological strengths and limitations |

| 3. Analysis | Classify and meta-summarize findings by extracting, editing, and grouping |

| 4. Synthesis | Integrate findings and offer novel interpretation |

Search methods

We began with a comprehensive literature search to identify all articles that used qualitative methods to describe factors affecting self-management from the perspective of adults living with a chronic illness (Procedure 1). With the assistance of a medical librarian, we searched for articles in the Academic Search Premier, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and PubMed databases as the most likely databases to contain literature on chronic illness self-management. We used combinations of the terms: ‘self- management’; ‘chronic illness’; ‘chronic disease’; ‘qualitative’; ‘factors’; ‘barriers’; ‘obstacles’; and ‘facilitators’. We did not include ‘self-care’ as a search term because it often refers to general healthy lifestyle behaviors and we wanted to locate articles on factors in the specific context of self-management as a set of tasks and skills used to manage chronic illness.

We included peer-reviewed articles concerning factors (i.e., facilitators and barriers) affecting self-management in adults aged over 18 years with chronic illness that were written in English and published between January 2000 – May 2013. When qualitative and quantitative data were distinct, we included qualitative results of mixed methods studies. We included studies with data from children, family caregivers and/or health care providers, but only when data from adults with a chronic illness was reported separately from the other group(s). We excluded articles that focused on mental illness or substance abuse given that self-management experiences may differ among these populations. We likewise excluded metasyntheses, literature reviews, theory-based works, dissertations, secondary analyses and evaluations of self-management interventions.

Search outcome

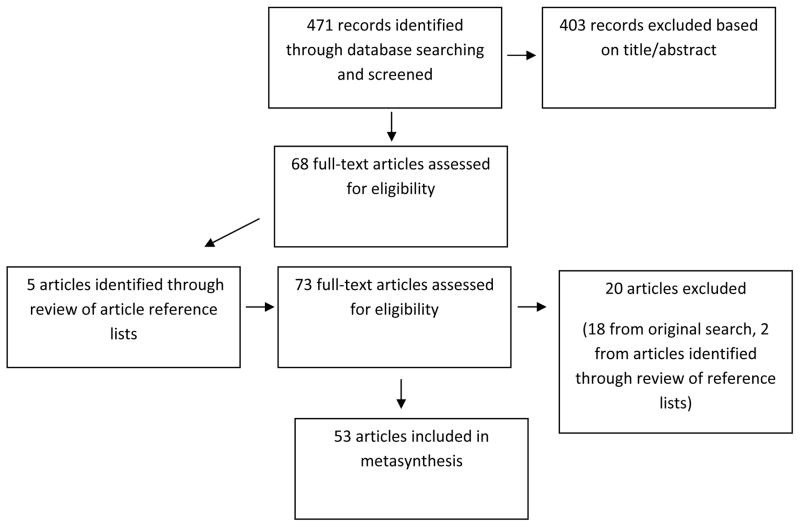

Figure 2 shows the flow of our literature search. Our initial search yielded 471 articles. Two reviewers read the titles and abstracts of these articles and judged, first independently and then jointly, if articles met inclusion criteria. Following this process, 68 articles met our eligibility criteria. Next, the two reviewers independently read the full text of these 68 articles and then collaboratively made a determination on eligibility. We searched the reference lists of these articles to identify any new articles and found five additional articles, which we then reviewed using the above process. After reading the full text of all articles (N=73), we excluded 20 due to a focus on self-management processes rather than factors affecting self-management (N=9), focusing on the experience of chronic illness (N=5), or not meeting other inclusion criteria (N=6). Therefore, the sample for this metasynthesis was 53 articles. We created a data display matrix (Table 2) to categorize and compare articles (Miles & Huberman 1994) (Detailed data available in Table S1).

Figure 2.

Article Search Flow Diagram

Table 2.

METASYNTHESIS OF FACTORS AFFECTING SELF-MANAGEMENT: INCLUDED ARTICLES (N=53)

| Reference | Methods | Sample | Factors Affecting Self-Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Audulv et al. (2009) | Grounded Theory | N = 26; 69% Female; Swedish; Mean age = 58.5; multiple chronic illnesses Swedish |

Demographics; Clinical; Psychological Support; Financial/Insurance/Employment Issues; Health Maintenance; Health System |

| Balfe (2009) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N = 17; 65% Female, n=6; English; Age range = 18–25; type 1 diabetes | Demographics; Psychological; Support |

| Brand et al. (2010) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N = 45; Male; 80% Female; Australian; Mean age = 52.9; Rheumatoid Arthritis | Clinical; Health System; Support; Communication; Health Maintenance; Assistive Devices/Technology |

| Chasens and Olshansky (2008) | Qualitative/Interpretive description | N = 17; 65% Female; African American, Caucasian and Native American; Mean age = 55.5; Diabetes | Clinical; Health Maintenance |

| Chudyk et al. (2011) | Not specified (focus group interview) | N = 28; 50% Female; Caucasian & Asian Indian; Mean age = 71; Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | Assistive Devices/Technology |

| Cooper et al. (2010) | Other: the initial qualitative phase of a sequential qualitative-quantitative mixed methods study | N = 24; 46% Female; United Kingdom; Age range 30–40; Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Health System; Psychological; Communication; Other |

| Costantini et al. (2008) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N = 14; 57% Female; Canada; Mean age = 41; Chronic Kidney Disease | Clinical; Psychological; Communication |

| Curtin and Mapes (2001) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description & Other: Exploratory-Descriptive | N = 18, 44% Female; African American, Hispanic, Caucasian; Mean age = 48.77; End Stage Renal Disease | Health System; Communication; Health Maintenance |

| De Brito-Ashurst et al. (2011) | Qualitative/Interpretive description | N = 20; 100% Female; Bangladeshi (UK) Mean age = 60 ; Chronic Kidney Disease |

Demographics; Support; Communication |

| Dickerson et al. (2006) | Phenomenology (interpretive, Heidegger’s approach) | N = 20; 100% Female; Ethnicity not reported (US) Mean age = 52.3; Cancer |

Assistive Devices/Technology |

| Dickson et al. (2008) | Other: Dialogical Interviewing | N = 41; 37% Female; African American & White Hispanic; Mean age = 49; Heart Failure | Financial/Insurance/Employment |

| Emlet et al.2011 | Not specified | N = 25; 32% Female; White, African American & Hispanic (US); Mean age = 56.1; HIV/AIDS | Support |

| Foster and Gaskins (2009) | Other: Mixed Method | N = 24; 29% Female; African Americans (US) Mean age = 57; HIV/AIDS |

Spiritual |

| Gee et al. (2007) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N = 23; 65% Female; African American, Latino, Non-Hispanic White; Mean age = 22.1; Diabetes | Demographics; Support; Financial/Insurance/Health; Health System |

| Gordon et al. (2007) | Other: Inductive | N = 98; 58% Female; White, Black (UK); Mean age = 67; Cardiovascular | Clinical; Health System; Communication Health Maintenance |

| Griva et al. (2013) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N = 37; 41% Female; Chinese, Malay, Indian Ethnic groups/Singapore; Mean age = 51.3; End-Stage Renal Disease | Clinical; Health System; Psychological; Support; Financial/Insurance/ Employment Issues; Communication; Health Maintenance |

| Handley et al. (2010) | Phenomenology & Grounded Theory | N = 9; 56% ; New Zealand Europeans, Maori, Samoan; Age range = 43–79; Type 2 Diabetes | Clinical; Health System; Spiritual; Health Maintenance |

| Henriques et al. (2012) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N = 18; 61% Female; Portugal Age > 65 years; “four or more chronic illnesses” |

Demographics; Clinical; Health System; Psychological; Support; Financial/Insurance/Employment Issues; Communication; Health Maintenance; Assistive Devices/Technology |

| Horowitz et al. (2004) | Grounded Theory | N = 19; 47% Female; African American, Latino, Caucasian (US); Age range = 52–89; Congestive Heart Failure | Clinical; Health System; Psychological |

| Hwu and Yu, 2006 | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N = 36; 44% Female; Taiwanese (Taiwan); Mean age = 60; Cancer, stroke, heart disease, diabetes mellitus, liver disease, chronic lung disease, renal disease, hypertension & rheumatic disease | Clinical; Psychological; Support; Financial/Insurance/ Employment Issues; Health Maintenance; Assistive Devices/Technology |

| Jowsey et al. (2009) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N = 52; 46% Female; Australia; Most patients over 65 years; Diabetes, COPD, CHF | Clinical; Heath Systems |

| Jo Wu et al. (2008) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N = 9; 67% Female; Australian; Mean age = 68.5; Type 2 diabetes, comorbidities, ischemic heart disease, hypertension & hyperlipidemia | Clinical; Health System |

| Lin et al. (2008) | Not specified | N = 41; 46% Female; Taiwanese (Taiwan); Mean age = 61.37; Type 2 Diabetes | Demographics; Psychological; Support Health Maintenance; Assistive Devices/Technology |

| Lowe and McBride-Henry (2012) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N = 3; 100% Female; New Zealand; Mean age = 84; MI, arthritis, Meniere’s disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, asthma | Support; Health Maintenance |

| Lundberg and Thrakul (2011) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N = 29; 100% Female; n=29; Thai Muslim (Bangkok); Age range = 40–80; Type 2 Diabetes | Demographics; Clinical; Psychological; Spiritual; Support; Communication; Health Maintenance; Other |

| Lundberg and Thrakul (2012) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N = 30; 63% Female; Thai Buddhist (Bangkok); Mean age = 52.3; Type 2 Diabetes | Demographics; Clinical; Health System Spiritual; Support; Financial/Insurance/ Employment; Communication; Health Maintenance |

| McCarthy et al. (2010) | Other: case study | N = 5; 40% Female; Australia; Age range = 48–85; Renal Failure | Clinical; Support; Communication Assistive Devices/Technology |

| Mead et al. (2009) | Other: Focus Groups/Content Analysis | N=282 (or 387?); 70% Female (n=198, male=84); African American& Hispanic (USA); Age range = 18–64; Serious Heart Condition/Cardiovascular Disease; | Clinical; Health System; Psychological; Financial/Insurance/Employment; Communication |

| Modeste and Majeke (2010) | Other: Descriptive Exploratory w/ Qualitative Approach | N=11, 100% Female; South Africa; Age range = 25–57; HIV/AIDS | Clinical; Health System; Psychological; Support; Financial/Insurance/Employment Issues; Health Maintenance |

| Nagelkerk et al. (2006) | Other: focus groups/content analysis | N=24; 50% Female; Caucasian; Mean age = 59; | Clinical; Health System; Psychological; Financial/Insurance/Employment; Communication; Health Maintenance |

| Newcomb et al. (2010) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N=104; 67% Female; Multiethnic groups (USA); Mean age = 50; Asthma | Clinical; Health System; Psychological; Support; Financial/Insurance/Employment; Issues; Communication; Health Maintenance; Assistive Devices/Technology |

| Oftedal et al. (2010) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description or Other: focus group interview | N=21; 43% Female; Norway; Median age for each focus group: 57, 52, 42 ; Type 2 diabetes | Clinical; Support; Communication |

| Oftedal et al. (2010) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N= 19; 36% Female; Norway; Mean age = 51; Type 2 diabetes | Psychological; Financial/Insurance/ Employment Issues; Communication |

| Orzech et al. (2013) | Other: focus group, individual interviews & content analysis | N=71; Gender not reported; Multiethnic groups (USA); Mean age for White = 54.2, Black = 50.5, Vietnamese = 61.9, Latino = 53.9; Diabetes and hypertension (participants had either or both) | Demographics; Support; Financial/Insurance Employment Issues; Communication; Health Maintenance |

| Pascucci et al. (2010) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N= 30; 17% Female; Multiethnic groups (USA); Age range = 30–83; Diabetes, Heart Disease | Clinical; Financial/Insurance/Employment; Health Maintenance; Other |

| Paterson (2001) | Grounded Theory | N= 22, 64% Female; White (Canada); Mean age = 43 ; Type 1 diabetes | Financial/Insurance/Employment Issues; Communication; Health System |

| Plach et al. (2005) | Other: Longitudinal (10 interviews over 2 years) | N=9; 100% Female; Multiethnic groups (USA); Mean age = 52; HIV/AIDS | Spiritual; Financial/Insurance/Employment; Health System |

| Ploughman et al. (2012) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N= 18; 78% Female; Euro-Canadian; Mean, range not reported but participants aged 55+; Multiple Sclerosis | Clinical; Health System; Psychological; Support; Communication; Health Maintenance; Assistive Devices/Technology; Other |

| Rasmussen et al. (2011) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N= 20; 75% Female; Ethnicity not reported (Australia); Age range = 18–38; Type 1 Diabetes | Demographics; Clinical; Support |

| Riegel and Carlson (2002) | Not specified | N=26; 35% Female; Ethnicity not reported (USA); Mean age = 74.4 ; Heart Failure | Clinical; Health System; Support; Communication; Health Maintenance; Assistive Devices/Technology |

| Riegel et al. (2010) | Other: Mixed Method | N=27; 30% Female; White (Australia); Mean age = 68.7; Chronic Heart Failure | Clinical; Psychological; Support |

| Riegel et al. (2007) | Not specified | N=29; Gender not reported; White (USA); Age range not reported; Heart Failure | Clinical; Support; Health Maintenance |

| Roberto et al. (2005) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N=17; 100% Female; Ethnicity not reported (USA); Mean age = 76.1 ; Heart failure, diabetes, osteoporosis | Clinical; Support; Financial/Insurance/ Employment Issues; Health Maintenance |

| Savoca and Miller (2001) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N=45; 58% Female; Multiracial (Country not reported); Mean age = 52.6; Type 2 Diabetes | Clinical; Psychological; Health Maintenance |

| Schnell et al. (2006) | Other: Semi-structured interviews | N=11; 36% Female; Caucasian and Aboriginal (Canada); Mean age = 64; Chronic Heart Failure | Health System; Support; Communication; Health Maintenance; Assistive Device |

| Song et al. (2010) | Other: focus group interviews | N=24; 42% Female; Korea; Mean age = 69.9; Type 2 Diabetes | Clinical; Demographics; Support; Health Maintenance |

| Utz et al. (2006) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N=73; 58% Female; African American (USA); Mean age = 60; Type 2 diabetes | Clinical; Health System; Psychological; Spiritual; Support; Financial/Insurance/ Employment; Communication; Health Maintenance; Assistive Devices/Technology |

| Vest et al. (2013) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description (focus group) | N=34; 76% Female; Multi-ethnic groups (USA); Mean age = 58; Diabetes | Health System; Support; Financial/Insurance/ Employment; Communication |

| Wellard et al. (2008) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N=4; 75% Female; Australia; Age range = 55–65; Type 2 Diabetes | Health System; Support; Assistive Devices/Technology; Other |

| Winters et al. (2006) | Other: Multimethod integrated design | N=142; 100% Female; Race not reported; Mean age = 50.39; Rheumatoid conditions, MS, diabetes, cancer, heart disease | Demographic; Clinical; Support; Financial/Insurance/Employment Issues; Health Maintenance; Assistive Devices/Technology; Other |

| Wortz et al. (2012) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N=47; 47% Female; Multi-ethnic groups (No country reported); Mean age = 68.4; Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary disease | Clinical; Psychological; Support; Health Maintenance; Assistive Devices |

| Wu et al. (2011) | Qualitative/Interpretive Description | N=17; 53% Female; Taiwan; Mean age = 46.4; Diabetes (focuses on hypoglycemia) | Clinical; Psychological; Support; Communication; Health Maintenance |

| Zhang and Verhoef (2002) | Grounded Theory | N=19; 84% Female; Chinese immigrants (Canada); Age range = 30–70; Osteoarthritis/ rheumatoid arthritis | Demographics; Health System; Spiritual; Support; Financial/Insurance/ Employment Issues; Communication |

Among included articles, various qualitative designs and methods of data collection were used, including qualitative/interpretive description (N=27), focus group (N=6), mixed method (N=6), grounded theory (N=4), dialogical interviewing (N=3), phenomenology (N=1) and case study (N=1, 3 cases). The study type or method of data collection was not specified in five articles. Across all articles, 16 chronic illnesses were represented, most commonly type 1 and 2 diabetes (N=28) and cardiovascular disease (N=20). Samples, which ranged in size from 3–387 (median=24), represented 20 countries and included men and women of diverse races and ethnicities aged 18 to 94 (mean=57 years).

Quality appraisal

Next, we evaluated each article for quality (Procedure 2). To expedite the review process, we (all authors) assessed article quality (high, medium, low) using a slightly modified version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2014). Our quality checklist (‘Yes/No’) included seven key items assessing study design, sampling method, data collection and analysis procedure, saturation and the meaningfulness of the results. We also included space for reviewers’ open-ended comments to discuss with the team. We believe that the method we used accurately assessed the quality of articles by capturing the main tenets of quality and rigor of qualitative research. We did not find any low quality articles and had no exclusions. We report article scores in Table S2.

Data abstraction and synthesis

To classify and summarize studies (Procedure 3), we recorded information from each article on study design, sample characteristics and factors affecting self-management. Of note, the risk and protective factors specified in the Self- and Family Management Framework informed our work but did not guide data abstraction or synthesis. We divided eligible articles among all authors, who were each responsible for independently extracting the aforementioned data from their assigned articles line-by-line. To ensure standardization of abstraction procedures, our team agreed to include any theme, subtheme, participant quote, or phrase in an article that described a factor affecting self-management. We were mindful about distinguishing between processes of self-management and factors affecting self-management; however, in some cases, a self-management process (e.g., communication with health care professionals) was also a factor affecting self-management (e.g., good/poor communication with health care professionals). Following independent data abstraction, the team came together to review all data abstraction forms and to resolve any differences of opinion through consensus.

Concurrent with data abstraction, we developed data coding categories. After independent review of the first ten articles, the team determined an initial coding scheme for factors affecting self-management. We used the constant comparative approach (Miles & Huberman 1994) to examine similarities and differences among factors affecting self-management as they emerged. We initially identified eleven categories of factors: Demographic (4 subcodes); Clinical (4 subcodes); Health System (9 subcodes); Psychological (10 subcodes); Spiritual (3 subcodes); Support (4 subcodes); Financial/Insurance (5 subcodes); Communication (15 subcodes); Environment (16 subcodes); Assistive Devices/Technology (15 subcodes); and Self-Management (9 subcodes).

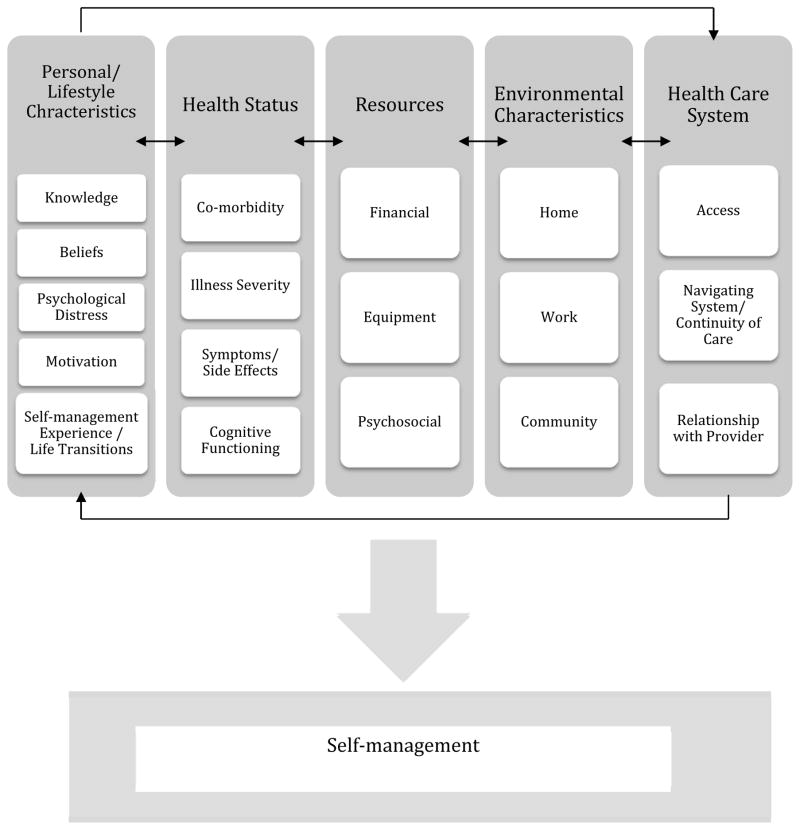

To synthesize findings (Procedure 4), we collapsed and expanded themes to determine an overall conceptualization of the analysis. We carefully considered the fit of sub-codes in each category, collapsing and expanding categories as indicated by group consensus. Our team discussed concepts underlying these eleven categories and we ultimately clustered them inductively into five higher level categories: Personal/Lifestyle Characteristics, Health Status, Resources, Environmental Characteristics and Health Care System.

We again worked in teams of two to re-code the data per these higher level categories, first coding independently and then jointly to resolve any coding conflicts. Table 3 shows the final categories and their subcodes. To maximize validity, we referred to our data abstraction forms and/or full-text manuscripts to ensure that our coding categories reflected self-management factors as described by adults with chronic illness. In addition, we took notes during team meetings to maintain an audit trail of our decision-making. To complete our synthesis, we discussed themes across categories and produced a graphic of factors affecting self-management.

Table 3.

Categories of Factors Affecting Self-Management and Associated Codes

| Category | Sub-Category | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Personal/Lifestyle Characteristics | Knowledge |

|

| Beliefs | Health Beliefs

|

|

| Psychological Distress |

|

|

| Motivation |

|

|

| Self-Management Experience/Life Patterns |

|

|

| Health Status | Co-morbidities |

|

| Illness Severity |

|

|

| Symptoms/Side Effects |

|

|

| Cognitive Functioning |

|

|

| Resources | Financial |

|

| Equipment | Devices-electronic or non-electronic

|

|

| Psychosocial |

|

|

| Environmental Characteristics | Home |

|

| Work |

|

|

| Community |

|

|

| Health Care System | Access |

|

| Navigating System/Continuity of Care |

|

|

| Relationship With Provider | Health Care Provider (HCP)

|

FINDINGS

As noted, the five main categories of factors affecting self-management were Personal/Lifestyle Characteristics, Health Status, Resources, Environmental Characteristics and Health Care System. Each category is described below.

Personal/Lifestyle Characteristics

Personal/Lifestyle Characteristics that influenced self-management included knowledge, beliefs (cultural, spiritual and health), psychological distress, motivation and life patterns.

Knowledge

Individuals reported that knowledge about disease processes, the role of medications and their treatment plan was critical to their ability to successfully self-manage. Most importantly, individuals needed to know how to apply self-management knowledge to their lives. They reported that if they did not know why and how to manage their chronic illness, self-management efforts were impeded (Savoca & Miller 2001, Riegel & Carlson 2002, Horowitz et al. 2004, Roberto et al. 2005, Schnell et al. 2005, Hwu & Yu 2006, Nagelkerk et al. 2006, Utz et al. 2006, Gordon et al. 2007, Riegel et al. 2007, Costantini et al. 2008, Mead et al. 2010, Modeste & Majeke 2010, Newcomb et al. 2010, Lundberg & Thrakul 2011, Rasmussen et al. 2011, Henriques et al. 2012, Ploughman et al. 2012, Wortz et al. 2012, Griva et al. 2013).

Beliefs

Cultural beliefs and traditions primarily affected individuals in terms of a lack of congruence between people’s cultural beliefs and self-management practices. For example, in Asian populations, if self-management tasks recommended by Western providers were incongruent with an individual’s belief in Eastern medicine, these tasks would not be completed as recommended (Zhang & Verhoef 2002, Lin et al. 2008, Newcomb et al. 2010, De Brito-Ashurst et al. 2011, Lundberg & Thrakul 2012). Individuals also reported struggling with self-management of their diet when recommendations were counter to their cultural practices or values (De Brito-Ashurst et al. 2011, Lundberg & Thrakul 2012, Orzech et al. 2013). For example, Vietnamese individuals with diabetes ate ‘forbidden foods,’ or foods that were not on their recommended diet, when they were offered them so as not to offend their hosts (Orzech et al. 2013).

Individuals reported that spiritual beliefs affected their coming to terms with a chronic illness and accepting the resultant change in life (Plach et al. 2005, Foster & Gatkins 2009, Handley et al. 2010). In addition, prayer and spiritual beliefs contributed to individuals’ sense of control and confidence in their ability to self-manage. Spiritual beliefs about the cause of illness or cures could influence individuals’ choices regarding health care providers (Utz et al. 2006) or treatments (Zhang & Verhoef 2002). Religious practices were mentioned as a potential barrier to self-management, e.g., fasting for Ramadan hindered the ability to follow a prescribed diet (Lundberg & Thrakul 2012).

Personal health beliefs were cited as both facilitators and barriers to self-management. Specifically, perceived control over illness and symptoms was identified as an important facilitator of self-management, such that increased perceptions of control facilitated better self-management (Horowitz et al. 2004, Hwu & Yu 2006, Cooper et al. 2010). Perceptions of the positive and negative consequences of self-management tasks were also reported to influence self-management efforts (Schnell et al. 2005, Hwu & Yu 2006, Lin et al. 2008, Henriques et al. 2012, Lundberg & Thrakul 2012). When individuals perceived the positive consequences of their self-management task, or the negative consequences of not completing self-management tasks, they expended more effort on self-management. Negative beliefs towards self-management, such as believing that self-management or treatment was time-consuming, inconvenient, complex, hard work, or did little to control their chronic illness, hindered individuals’ self-management behaviors (Savoca & Miller 2001, Roberto et al. 2005, Hwu & Yu 2006, Nagelkerk et al. 2006, Utz et al. 2006, Jo et al. 2008, Handley et al. 2010, Song et al. 2010, Lundberg & Thrakul 2011, Lundberg & Thrakul 2012, Henriques et al. 2012, Wortz et al. 2012, Griva et al. 2013).

Psychological Distress

Individuals reported that psychological distress influenced their self-management. Stress, including the pressure of multiple roles (Modeste & Majeke 2010) was mentioned as a barrier to self-management (Balfe 2009, Mead et al. 2010). Similarly, fear, anxiety and impaired mood (Chasens & Olshansky 2008, Jo et al. 2008, Wortz et al. 2012) had a negative impact on self-management (Wu et al. 2011, Ploughman et al. 2012); however, anxiety also served as a facilitator when it caused individuals to be more vigilant of symptom monitoring and other self-management tasks (Riegel et al. 2010).

Motivation

Motivation and self-discipline (or lack thereof, Song et al. 2010) affected perseverance with self-management efforts (Oftedal et al. 2010b). Sense of self-efficacy, or personal control, also contributed to motivation to self-manage (Horowitz et al. 2004, Schnell et al. 2005, Hwu & Yu 2006, Cooper et al. 2010, Handley et al. 2010, Lundberg & Thrakul 2012). Stigma was noted as a motivating factor; individuals talked about taking care of themselves to avoid the stigma of needing additional devices or accommodations and wanting to ‘achieve a normal life’ (Audluv et al. 2009, Ploughman et al. 2012).

Life patterns

Prior self-management experience, the ability to create a self-management routine and life transitions were other personal characteristics that influenced self-management. Prior self-management experiences where self-management practices improved health had a positive effect on current health beliefs and behaviors (Savoca & Miller 2001, Riegel et al. 2007, Lin et al. 2008, Henriques et al. 2012). In contrast, those who experienced adverse effects of self-management or threats of further harm were less willing to continue with self-management (Hwu & Yu 2006, Griva et al. 2013). For example, some individuals with diabetes hesitated to take insulin due to a fear of hypoglycemia (Griva et al. 2013).

Developing a daily self-management routine was reported to facilitate self-management (Hwu & Yu 2006, Song et al. 2010, Pascucci et al. 2012, Griva et al. 2013), such as doing exercises at the same time every day. These strategies helped individuals remember to engage in self-management behaviors. Having a busy schedule complicated the ability to develop and maintain routines (Savoca & Miller 2001, Riegel & Carlson 2002, Hwu & Yu 2006, Handley et al. 2010, Song et al. 2010). Disruptions of daily routines caused by special occasions, travelling, vacation, holidays and weather challenged individuals’ self-management routines (Savoca & Miller 2001, Roberto et al. 2005, Newcomb et al. 2010, Pascucci et al. 2010, Song et al. 2010). Individuals needed flexibility and creativity to maintain routines when circumstances changed.

Life transitions also affected self-management. For example, the relatively unstructured life of college students inhibited young adults’ ability to establish and maintain health care routines (Balfe 2009). Other life transitions, such as becoming a mother or beginning employment also required reprioritizing and adjustment of self-management regimens (Rasmussen et al. 2011). Getting older was reported to affect self-management due to increased potential for cognitive issues that could inhibit self-management, such as forgetting to take medications (Song et al. 2010).

Health Status

Individuals’ health status, including co-morbidities, illness severity, symptoms, side effects from treatment and cognitive functioning were cited as factors that influenced self-management tasks. Physical co-morbidities added complexity to health care regimens and contributed to symptoms that interfered with self-management efforts (Riegel & Carlson 2002, Roberto et al. 2005, Hwu & Yu 2006, Utz et al. 2006, Brand et al. 2010, McCarthy et al. 2010, Newcomb et al. 2010, Riegel et al. 2010, Ploughman et al. 2012, Wortz et al. 2012, Griva et al. 2013). For example, shortness of breath from chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder could contribute to inability to exercise as part of diabetes or cardiac self-management (Schnell et al. 2005). Symptoms and side effects, particularly pain and fatigue, were identified as barriers to self-management (Savoca & Miller 2001, Roberto et al. 2005, Schnell et al. 2005, Hwu & Yu 2006, Gordon et al. 2007, Riegel et al. 2007, Chasens & Olshansky 2008, Audluv et al. 2009, Jowsey et al. 2009, McCarthy et al. 2010, Pascucci et al. 2010, Wu et al. 2011, Henriques et al. 2012, Wortz et al. 2012). Notably, the absence of symptoms was identified as a factor that diminished self-management efforts, either due to lack of perceived seriousness or lack of perceived benefit (Constantini et al. 2008, Handley et al. 2010). Cognitive impairment was reported as a barrier to recognizing signs and symptoms, remembering to carry out self-management tasks, or problem-solving (Riegel et al. 2007, Jo Wu et al. 2008, McCarthy et al. 2012).

Resources

Resources that influenced self-management included financial resources, equipment and psychosocial support. The extent and quality of personal resources could influence self-management.

Financial

Limited financial resources, lack of insurance and financial instability were reported as major barriers to self-management. For example, low-income individuals paid more attention to their economic survival than to controlling their disease (Nagelkerk et al. 2006, Modeste & Majeke 2010, Lundberg & Thrakul 2011). The high price of medication, healthy food, supplies and alternative therapies served as barriers to self-management by restricting individuals’ choices. Factors related to employment, such as loss of work or maintaining working ability, were also reported to affect self-management efforts. Lack of or limited insurance coverage greatly impeded self-management by decreasing individuals’ access to health care and creating difficulties in obtaining medication (Gee et al. 2007, Mead et al. 2010, Newcomb et al. 2010, Vest et al. 2013). In contrast, financial support from family and friends facilitated self-management efforts, such as enabling purchase of high-cost foods as part of a prescribed diet (Orzech et al. 2013).

Equipment

Assistive devices that helped or hindered self-management included the Internet, as well as electronic and non-electronic equipment. The Internet could facilitate self-management by providing helpful information about health conditions and connecting individuals to peer support and other resources (Dickerson et al. 2006, Utz et al. 2006, Winters et al. 2006, Wellard et al. 2008, Brand et al. 2010, McCarthy et al. 2010). The Internet could also hinder self-management by offering an overwhelming amount of information, some of which could be perceived as frightening or unreliable (Dickerson et al. 2006, Balfe 2009).

Electronic equipment (e.g., glucose monitors) and non-electronic equipment (e.g., pill boxes) were also described as both facilitators and barriers to self-management. These types of equipment facilitated self-management by helping individuals to learn about their health condition, to make self-management decisions and to adapt to their environment. For example, individuals with memory problems recorded their daily schedule in a logbook to help them maintain self-management routines (Ploughman et al. 2012). Equipment could also serve as barrier to self-management due to perceived inconvenience or stigma. In one study, perception of adaptive devices was reported as a ‘clear marker of disability’, thus inhibiting their use (Ploughman et al. 2012).

Psychosocial

Psychosocial support was cited as a factor that affected self-management efforts in both positive and negative ways. Individuals reported that positive support from partners or peers was very influential (Hwu & Yu 2006, Gee et al. 2007, Brand et al. 2010, Henriques et al. 2012) and increased empowerment (Brand et al. 2010). Family and friends, especially those nearby (Hwu & Yu 2006, Emlet et al. 2010), helped with various aspects of self-management, including preparing healthy food, providing reminders about medication and accompanying individuals to medical appointments (Winters et al. 2006, Lundberg & Thrakul 2011, Lunberg & Thrakul 2012). However, individuals also reported a lack of or negative support from partners or peers (Roberto et al. 2005, Balfe et al. 2009, Newcomb et al. 2010, Orzech et al. 2013) as a self-management barrier. For example, a lack of spousal support for a new diet was identified as a barrier to following treatment recommendations (Savoca & Miller 2001).

Many adults highlighted the role of support groups and peer support as an important facilitator to self-management. Specifically, support groups and peers with the same condition offered an opportunity to share information (Utz et al. 2006, Ploughman et al. 2012, Giva et al. 2013) and feel connected to a community (Rasmussen et al. 2011, Lowe & McBride-Henry 2012). Finally, isolation, i.e., not having social support, was discussed as a barrier to self-management (Riegel et al. 2007, DeBrito-Ashurst et al. 2011).

Environmental Characteristics

Home, work and community were discussed as environmental factors that affected self-management.

Home

In the home environment, living among family members with different dietary preferences was a barrier to following a recommended diet (Schnell et al. 2005, Hwu & Yu 2006, Audluv et al. 2009, Wu et al. 2011, Orzech et al. 2013). Individuals could experience conflict with family members over food served in the home and reported receiving food from family members that was not congruent with their prescribed diets (Schnell et al. 2005, Hwu & Yu 2006, Orzech et al. 2013). Health problems of other family members were another reported barrier to self-management, as others’ health problems created competing demands and less ability to concentrate on personal self-management needs (Wu et al. 2011, Ploughman et al. 2012).

Work

In the work environment, time and schedule constraints imposed by work were identified as a barrier that hindered the ability to carry out self-management related to diet, exercise and medications (Dickson et al. 2008, Audluv et al. 2009, Oftedal et al. 2010b, Lundberg & Thrakul 2012). In contrast, the support provided by employers and co-workers, in addition to a sense of belonging found at work, facilitated self-management (Dickson et al. 2008, Oftedal et al. 2010b).

Community

In the community, barriers to self-management included lack of transportation to get to the gym or to medical appointments (Lundberg & Thrakul 2001, Utz et al. 2006, Winters et al. 2006, Modeste & Majeske 2010, Pascucci et al. 2012), exposure to unhealthy food at restaurants (Savoca & Miller 2001, Utz et al. 2006, Chasens & Olshansky 2008, Pascucci et al. 2010, Lundberg & Thrakul 2012) and in various social environments (Hwu & Yu 2006, Chasens & Olshansky 2008, Handley et al. 2010, Orzech et al. 2013) and lack of knowledge among the general public about chronic illness (Wellard et al. 2008, Foster & Gaskins 2009, Cooper et al. 2010, Oftedal et al. 2010b). Individuals reported that eating out was challenging because foods in restaurants and convenience stores were often highly processed, had little nutritious value and came in large portion sizes (Savoca & Miller 2001, Utz et al. 2006, Pascucci et al. 2010, Lundberg & Thrakul 2012). Individuals reported that seeing others eat or seeing foods being offered by family or friends tempted them and inhibited their diet regulation (Hwu & Yu 2006, Chasens & Olshansky 2008, Handley et al. 2010, Orzech et al. 2013). The lack of public knowledge about chronic illness and self-management behaviors also affected individuals’ self-management (Wellard et al. 2008, Foster & Gaskins 2009), at times creating social stigma associated with chronic illness (Foster & Gaskins 2009, Oftedal et al. 2010b).

Health System

Health system factors that influenced individuals’ ability to carry out self-management tasks included access to health care, the ability to navigate the health care system and ensure continuity of care and relationships with providers.

Access

Individuals reported that access (or lack of access) to specialists, nursing care, self-management programs and alternative therapy was an important factor that influenced their self-management (Curtin & Maples 2001, Schnell et al. 2005, Utz et al. 2006, Winters et al. 2006, Lin et al. 2008, Brand et al. 2010, Mead et al. 2010, Henriques et al. 2012, Ploughman et al. 2012, Vest et al. 2013). In addition, access to educational resources from outside the health care system, such as obtaining information from radio, books, or brochures, was identified as a facilitator (Schnell et al. 2005, Brand et al. 2010, Lundberg & Thrakul 2011, Lundberg & Thrakul 2012).

Navigating System/Continuity of Care

Navigating the health care system and continuity of care were challenges for some adults with chronic illness. Individuals reported that long wait times for appointments, unreturned phone messages, or confusing communication with clinic staff negatively affected self-management (Schnell et al. 2005, Gordon et al. 2007, Brand et al. 2010, Newcomb et al. 2010). Some adults who had multiple health care providers expressed that they did not know who to call or when to call (Brand et al. 2010). Further, when individuals saw different providers at every appointment, they expressed challenges in communication and difficulty obtaining prescriptions (Plach et al. 2005, Gordon et al. 2007, Newcomb et al. 2010). Inconsistent advice by providers was also noted when there was a lack of continuity of care (Riegel & Carlson 2002).

Relationships with Providers

self-management was facilitated by positive patient-provider relationships where patients had time to share concerns, related to their provider and felt support, trust and empathy (Patterson 2001, Schnell et al. 2005, Nagelkerk et al. 2006, Jo et al. 2008, Jowsey et al. 2009, Brand et al. 2010, McCarthy et al. 2010, Mead et al. 2010, Newcomb et al. 2010, Oftedal et al. 2010a, Oftedal et al. 2010b, Wu et al. 2011, Henriques et al. 2012, Ploughman et al. 2012, Griva et al. 2013, Vest et al. 2013). In addition, self-management was supported by a collaborative approach where patients and providers were partners in self-management and problem-solved together with shared goals (Curtin & Maples 2001, Paterson 2001, Schnell et al. 2005, Nagelkerk et al. 2006, Utz et al. 2006, Cooper et al. 2010, Handley et al. 2010, Oftedal et al. 2010b, Lundberg & Thrakul 2012, Ploughman et al. 2012). Individuals expressed that adequate time was essential to understand changes in self-management, to ask questions, or to get feedback on self-management (Newcomb et al. 2010, Vest et al. 2013). Feeling confident in their health care providers’ competence was reported as necessary to follow recommended self-management tasks (Zhang & Verhoef 2002, Winters et al. 2006, Wu et al. 2011).

Good communication was essential to positive patient-health care provider relationships. When providers used medical jargon or technical language (Patterson 2001, Riegel & Carlson 2002, Zhang & Verhoef 2002, Gordon et al. 2007, Jowsey et al. 2009), patients were confused and left wondering what they should be doing. The same was the case when providers rushed communication or provided an inadequate amount of information (Gordon et al. 2007, Costantini et al. 2008, Brand et al. 2010, Newcomb et al. 2010, Oftedal et al. 2010a, Ploughman et al. 2012). Provider-related factors that facilitated self-management were actively listening to patients’ input on their health condition, valuing patients’ subjective illness experience, investing time to get to know patients as individuals (Paterson 2001, Wu et al. 2011, Henriques et al. 2012, Ploughman et al. 2012, Zhang & Verhoef 2002), having regular visits (Paterson 2001, McCarthy et al. 2010), offering practical advice and anticipatory guidance (Schnell et al. 2005, Mead et al. 2010, Oftedal et al. 2010a) and recommending culturally-sensitive self-management strategies, which increased the likelihood of strategies being followed (DeBrito-Ashurst et al. 2011, Orzech et al. 2013).

Individuals likewise identified their own communication as affecting self-management. Problems included limiting communication or not being honest with their providers to avoid conflict (Curtin & Maples 2001, Newcomb et al. 2010, Lundberg & Thrakul 2012). Language barriers, specifically, not reading or speaking English (Zhang & Verhoef 2002, DeBrito-Ashurst et al. 2011, Griva et al. 2013), were also reported as impeding self-management. Proactively seeking information, making suggestions and sharing their opinion about their self-management regimen with providers were patient-related factors that facilitated self-management (Curtin & Maples 2001, Utz et al. 2006).

Factors affecting self-management may interact

We found that factors affecting self-management did not occur or act in isolation. Rather, various factors could interact to affect an individual’s ability and/or motivation to self-manage, as well as the quality of self-management. Figure 3 is a graphic representation of factors affecting self-management and their relationship to each other, showing that both within and across factor categories, factors may interact to affect self-management. For example, in the Resources category, having limited financial resources (Financial) could affect an individual’s ability to afford an assistive device, e.g., a glucose monitor (Equipment). Across categories, not having a glucose monitor could affect the Health Status factors of Illness Severity (if blood sugar levels are not well controlled) and Symptoms (if an individual develops severe hypoglycemia).

Figure 3.

Factors Influencing Self-Management

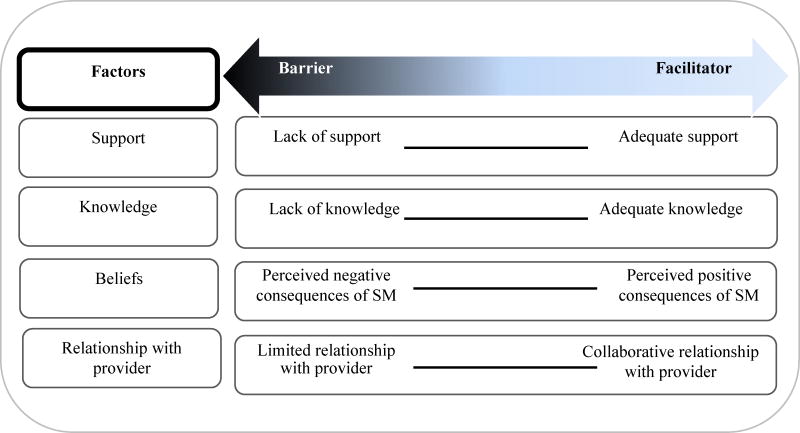

Factors affecting self-management are on a continuum

We also found that many factors affecting self-management could be conceptualized as being on a continuum where factors are not present or absent, but rather reflect degrees of positive (facilitators) or negative (barriers). That is, a particular factor can be a facilitator or a barrier to self-management depending on where an individual falls along the continuum. For example, social support is not typically present or absent, but is perceived as a degree of support. Involvement of family and friends may be a positive factor (facilitator), as when family is supportive (e.g., accompaniment to an appointment), or a negative factor (barrier), as when family is unsupportive (e.g., offering ‘forbidden’ foods), or somewhere in between, as when gestures that are indeed helpful may also be perceived as nagging or intrusive. Figure 4 shows exemplars of factors on the continuum.

Figure 4.

Continuum of Selected Factors Affecting Self-Management

DISCUSSION

This metasynthesis provides a rigorous review of factors affecting self-management from the perspective of adults living with chronic illness. We have specified self-management factors across a range of categories and have identified themes related to the nature and interaction of these factors. Identified factors and themes are consistent with other self-management frameworks (Dunbar et al. 2008, Ryan & Sawin 2009) and further specify the risk and protective factors of the Self- and Family Management Framework (Grey et al. 2015). By identifying facilitators and barriers related to the broad categories of risk and protective factors, we have detailed specific positive and negative influences on self-management to guide research and practice.

Our results are also consistent with other self-management reviews (Barlow et al. 2002, Newman et al. 2004, Warsi et al. 2004) in identifying individual and interpersonal aspects of self-management, particularly in our Personal/Lifestyle Characteristics category (e.g., symptoms, psychological and lifestyle components). Results of our metasynthesis extend previous work by identifying the individual, family, environment and health care system as contexts that influence self-management.

To provide a foundation for research on factors affecting self-management, we took a broad perspective and included studies on a variety of chronic illnesses among an international group of adults of diverse races and ethnicities. However, this metasynthesis does not provide a complete profile of what may help or hinder self-management in chronic illness. For example, in the articles that met our inclusion criteria, we found few demographic factors that might influence self-management. Yet, we know from quantitative work that demographic characteristics such as socio-economic status, gender and race influence self-management (Nwasuruba et al. 2007, Heo et al. 2008). Analysis of quantitative studies and studies not written in English would add to our data. In addition, our sample largely included adults with diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Studies are needed to identify factors both common among and specific to self-management of various chronic illnesses that may differ across the illness trajectory. Finally, although our sample included a diverse group of study participants from multiple countries, additional research is needed to better understand the influence of factors affecting self-management among individuals of different backgrounds, in different countries with varying health care systems and among those with multiple chronic illnesses.

While considerable effort has been expended worldwide to improve the management of chronic illnesses, chronic illness care remains a major challenge to health care systems globally. Improving access to self-management support programs has become a priority in numerous health care systems; however, for many individuals, care remains fragmented and self-management support programs, if provided, are not often integrated into primary care. Furthermore, many self-management programs focus on a single chronic illness, limiting the efficiency and effectiveness of such programs in populations where adults have high rates of co-morbidity (Geyman 2007).

Innovative programs and initiatives that address these barriers warrant attention. In Sweden, nurse-led clinics providing advanced care for adults with a chronic and complex condition (e.g., diabetes) have become common, with many integrated into primary care health centers in addition to hospital clinics. In the U.S., a chronic illness self-management program for adults, the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program, has demonstrated robust evidence of efficacy across a wide range of chronic illnesses (Ory et al. 2013); however, linkages with existing health care systems have not been evaluated. Workplace initiatives are increasingly being offered to support healthy behaviors in the workplace, such as fitness classes, access to healthy food and reducing sitting time (Center for Disease Control http://www.cdc.gov/features/workingwellness/). However, more could be done to facilitate the needs of people with chronic illness, such as offering flexible hours and psychosocial support. Ongoing effort to provide self-management support for adults with multiple chronic conditions that is integrated into work environments and the health care system is indicated.

Technology, such as decision-support (e.g. alerts, reminders, decision tools), interactive health communication between patients and health care providers and electronic health records that connect health care providers, holds great promise for linking providers and services, using resources effectively and providing integrated and coordinated health care for adults with chronic illness. Several countries, such as Denmark, the United Kingdom and Canada (Glasgow et al. 2008), have begun to implement technology-based platforms to improve health care for people with chronic illness.

Health policy that improves access to health care and prevents discrimination in the workplace for disability/illness is needed worldwide. For example, the UK Equality Act 2010 is aimed at preventing discrimination, including in the workplace (Equality Act 2010, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/85028/vcs-service-providers.pdf). Health care reform that focuses on prevention and wellness, such as the Affordable Care Act in the U.S., is also encouraging as a means for improving the health of populations with and without chronic illness (Anderko et al. 2012).

CONCLUSION

In this metasynthesis, we identified numerous factors that influence self-management, increasing the specificity of the Self- and Family Management Framework. Further development and application of this conceptualization of factors affecting self-management is warranted. Understanding factors that influence self-management may improve assessment of self-management among adults with chronic illness and may inform interventions tailored to meet individuals’ needs and improve health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

SUMMARY STATEMENT.

Why is this review needed?

There is no synthesis of factors that may affect individuals’ self-management.

Identification of factors can help define risk and protective factors in the Self- and Family Management Framework, informing interventions by specifying potential mediators and moderators of self-management behaviors or processes.

Specification of facilitators and barriers to self-management can assist individuals with chronic illness and their clinicians to identify and address modifiable factors.

What are the key findings?

We identified five categories of factors affecting self-management which detail specific positive and negative influences on self-management to guide research and practice.

Interaction of factors affects individuals’ ability and motivation to self-manage, as well as the quality of self-management, thereby forming a ‘factor profile’ that can help determine needed self-management support.

Factors may be conceptualized as being on a continuum ranging from negative (barriers) to positive (facilitators), hence self-management interventions may assist individuals in moving toward the positive side.

How should the findings be used to influence policy/practice/research/education?

Improving access to self-management support programs by integrating them into primary care may help to address fragmentation of care in health care systems.

Given high rates of comorbidity in adult populations, self-management programs should have the capacity to support management of multiple chronic illnesses rather than focusing on a single chronic illness.

Health policy that improves access to health care, prevents discrimination for disability/illness and focuses on prevention/wellness is needed to improve the health of populations with and without chronic illness.

Acknowledgments

Funding. This work was supported by the Center for Self and Family Management in Vulnerable Populations, P30NR008999, and the Center for Enhancement of Self-Management in Individuals and Families, P20NR0010674. At the time this work was completed, Dr. Schulman-Green was supported by a Mentored Research Scholar Grant, MRSG 08-292-05-CPPB from the American Cancer Society. Dr. Jaser is supported by awards from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, K23 NK088454, and the National Center for Research Resources, grant number UL1 RR024139.

The authors are grateful to Rebecca Linsky and Sarah Linsky for their assistance with this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Author Contributions:

- substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data;

- drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. * http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/

Contributor Information

Dena SCHULMAN-GREEN, Email: dena.schulman-green@yale.edu.

Sarah S. JASER, Email: sarah.jaser@vanderbilt.edu.

Chorong PARK, Email: chorong.park@yale.edu.

Robin WHITTEMORE, Email: robin.whittemore@yale.edu.

References

- Anderko L, Roffenbender JS, Goetzel RZ, Millard F, Wildenhaus K, DeSantis C, Novelli W. Promoting prevention through the Affordable Care Act: Workplace wellness. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2012;9:E175. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audulv Å, Norbergh KG, Asplund K, Hörnsten Å. An ongoing process of inner negotiation–a Grounded Theory study of self-management among people living with chronic illness. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness. 2009;1(4):283–293. [Google Scholar]

- Balfe M. Healthcare routines of university students with Type 1 diabetes. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65(11):2367–2375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2002;48(2):177–187. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner E, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(15):1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand C, Claydon-Platt K, McColl G, Bucknall T. Meeting the needs of people diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis: an analysis of patient-reported experience. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness. 2010;2(1):75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cener for Disease Control. [Accessed August 2015]; http://www.cdc.gov/features/workingwellness/

- Chasens ER, Olshansky E. Daytime sleepiness, diabetes and psychological well-being. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2008;29(10):1134–1150. doi: 10.1080/01612840802319878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudyk A, Shapiro S, Russell-Minda E, Petrella R. Self-monitoring technologies for type 2 diabetes and the prevention of cardiovascular complications: Perspectives from end users. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2011;5(2):394–401. doi: 10.1177/193229681100500229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium. Health Affairs. 2009;28(1):75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman K, Mattke S, Perrault PJ, Wagner EH. Untangling practice redesign from disease management: how do we best care of the chronically ill? Annual Review of Public Health. 2009;30:385–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JM, Collier J, James V, Hawkey CJ. Beliefs about personal control and self-management in 30–40 year olds living with inflammatory bowel disease: a qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2010;47(12):1500–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini L, Beanlands H, McCay E, Cattran D, Hladunewich M, Francis D. The self-management experience of people with mild to moderate chronic kidney disease. Nephrology Nursing Journal. 2008;35(2):147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) CASP Checklists. Oxford: CASP; 2014. ( http://www.casp-uk.net) [Google Scholar]

- Curtin RB, Mapes DL. Health care management strategies of long-term dialysis survivors. Nephrology Nursing Journal. 2001;28(4):385–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Brito-Ashurst I, Perry L, Sanders T, Thomas J, Yaqoob M, Dobbie H. Barriers and facilitators of dietary sodium restriction amongst Bangladeshi chronic kidney disease patients. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2011;24(1):86–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Boehmke M, Ogle C, Brown JK. Seeking and managing hope: patients’ experiences using the Internet for cancer care. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2006:E8–17. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.E8-E17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson VV, McCauley LA, Riegel B. Work—Heart Balance The Influence of Biobehavioral Variables on Self-Care among Employees with Heart Failure. AAOHN Journal. 2008;56(2):63–73. doi: 10.1177/216507990805600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Quinn C, Gary RA, Kaslow NJ. Family influences on heart failure self-care and outcomes. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2008;23(3):258–265. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000305093.20012.b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emlet CA, Tozay S, Raveis VH. ‘I’m Not Going to Die from the AIDS’: Resilience in Aging with HIV Disease. The Gerontologist. 2010;51(1):101–111. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [Accessed August 2015];Equality Act 2010: What do I need to know? 2010 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/85028/vcs-service-providers.pdf.

- Foster PP, Gaskins SW. Older African Americans’ management of HIV/AIDS stigma. AIDS Care. 2009;21(10):1306–1312. doi: 10.1080/09540120902803141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee L, Smith TL, Solomon M, Quinn MT, Lipton RB. The clinical, psychosocial and socioeconomic concerns of urban youth living with diabetes. Public Health Nursing. 2007;24(4):318–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyman J. Disease management: panacea, another false hope, or something in between? Annals of Family Medicine. 2007;5:257–60. doi: 10.1370/afm.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow N, Durand-Zaleski I, Chan E, Rubiano D. In: Caring for people with chronic conditions: A health system perspective. Nolte E, McKee M, editors. Berkshire, England: McGraw Hill Open University Press; 2008. pp. 172–194. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon K, Smith F, Dhillon S. Effective chronic disease management: patients’ perspectives on medication-related problems. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;65(3):407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey M, Knafl K, McCorkle R. A framework for the study of self-and family management of chronic conditions. Nursing Outlook. 2006;54(5):278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey M, Schulman-Green D, Knafl K, Reynolds NR. A Revised Self- and Family Management Framework. Nursing Outlook. 2015;63(2):162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griva K, Ng H, Loei J, Mooppil N, McBain H, Newman S. Managing treatment for end-stage renal disease–A qualitative study exploring cultural perspectives on facilitators and barriers to treatment adherence. Psychology & Health. 2013;28(1):13–29. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2012.703670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley J, Pullon S, Gifford H. Living with type 2 diabetes:’Putting the person in the pilots’ seat’. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010;27(3):12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques MA, Costa MA, Cabrita J. Adherence and medication management by the elderly. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012;21(21–22):3096–3105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo S, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Riegel B, Chung ML. Gender differences in and factors related to self-care behaviors: a cross-sectional, correlational study of patients with heart failure. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008;45(12):1807–1815. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz CR, Rein SB, Leventhal H. A story of maladies, misconceptions and mishaps: effective management of heart failure. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58(3):631–643. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00232-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwu YJ, Yu CC. Exploring health behavior determinants for people with chronic illness using the constructs of planned behavior theory. Journal of Nursing Research. 2006;14(4):261–270. doi: 10.1097/01.jnr.0000387585.27587.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo Wu CJ, Chang AM, McDowell J. Perspectives of patients with type 2 diabetes following a critical cardiac event - an interpretative approach. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(5A):16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jowsey T, Jeon YH, Dugdale P, Glasgow NJ, Kljakovic M, Usherwood T. Challenges for co-morbid chronic illness care and policy in Australia: a qualitative study. Australia and New Zealand Health Policy. 2009;6(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1743-8462-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CC, anderson RM, Hagerty BM, Lee BO. Diabetes self-management experience: a focus group study of Taiwanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(5a):34–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe P, McBride-Henry K. What factors impact upon the quality of life of elderly women with chronic illnesses: Three women’s perspectives. Contemporary Nurse. 2012;41(1):18–27. doi: 10.5172/conu.2012.41.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg PC, Thrakul S. Diabetes type 2 self-management among Thai Muslim women. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness. 2011;3(1):52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg PC, Thrakul S. Type 2 diabetes: how do Thai Buddhist people with diabetes practise self-management? Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2012;68(3):550–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy AL, Shaban R, Boys J, Winch S. Compliance, normality and the patient on peritoneal dialysis. Nephrology Nursing Journal. 2010;37(3):243–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, Schulman-Green D, Schilling LS, Lorig K, Wagner EH. Self-management: Enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2011;61(1):50–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.20093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead H, Andres E, Ramos C, Siegel B, Regenstein M. Barriers to effective self-management in cardiac patients: the patient’s experience. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;79(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Modeste RRM, Majeke SJ. Self-care symptom-management strategies amongst women living with HIV/AIDS in an urban area in KwaZulu-Natal: original research. Health SA Gesondheid. 2010;15(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nagelkerk J, Reick K, Meengs L. Perceived barriers and effective strategies to diabetes self-management. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;54(2):151–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb PA, McGrath KW, Covington JK, Lazarus SC, Janson SL. Barriers to patient-clinician collaboration in asthma management: the patient experience. Journal of Asthma. 2010;47(2):192–197. doi: 10.3109/02770900903486397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S, Steed L, Mulligan K. Self-management interventions for chronic illness. Lancet. 2004;364(9444):1523–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwasuruba C, Khan M, Egede LE. Racial/ethnic differences in multiple self-care behaviors in adults with diabetes. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(1):115–120. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0120-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oftedal B, Karlsen B, Bru E. Perceived support from healthcare practitioners among adults with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010a;66(7):1500–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oftedal B, Karlsen B, Bru E. Life values and self-regulation behaviours among adults with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010b;19(17–18):2548–2556. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory MG, Ahn S, Jiang L, Smith ML, Ritter PL, Whitelaw N, Lorig K. Successes of a National Study of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program: Meeting the Triple Aim of Health Care Reform. Medical Care. 2013;51(11):992–998. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a95dd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orzech KM, Vivian J, Torres CH, Armin J, Shaw SJ. Diet and exercise adherence and practices among medically underserved patients with chronic disease variation across four ethnic groups. Health Education & Behavior. 2013;40(1):56–66. doi: 10.1177/1090198112436970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascucci MA, Leasure AR, Belknap DC, Kodumthara E. Situational challenges that impact health adherence in vulnerable populations. Journal of Cultural Diversity. 2010;17(1):4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson B. Myth of empowerment in chronic illness. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;34(5):574–581. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plach SK, Stevens PE, Keigher S. Self-care of women growing older with HIV and/or AIDS. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;27(5):534–553. doi: 10.1177/0193945905275973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploughman M, Austin MW, Murdoch M, Kearney A, Godwin M, Stefanelli M. The path to self-management: a qualitative study involving older people with multiple sclerosis. Physiotherapy Canada. 2012;64(1):6–17. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2010-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. 8. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen B, Ward G, Jenkins A, King SJ, Dunning T. Young adults’ management of Type 1 diabetes during life transitions. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2011;20(13–14):1981–1992. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard AA, Shea K. Delineation of Self-Care and Associated Concepts. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2011;43(3):255–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel B, Carlson B. Facilitators and barriers to heart failure self-care. Patient Education and Counseling. 2002;46(4):287–295. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel B, Dickson VV, Kuhn L, Page K, Worrall-Carter L. Gender-specific barriers and facilitators to heart failure self-care: a mixed methods study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2010;47(7):888–895. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel B, Dickson VV, Goldberg LR, Deatrick JA. Factors associated with the development of expertise in heart failure self-care. Nursing Research. 2007;56(4):235–243. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000280615.75447.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto KA, Gigliotti CM, Husser EK. Older women’s experiences with multiple health conditions: Daily challenges and care practices. Health Care for Women International. 2005;26(8):672–692. doi: 10.1080/07399330500177147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P, Sawin KJ. The individual and family self-management theory: background and perspectives on context, process and outcomes. Nursing Outlook. 2009;57(4):217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research. Springer Publishing Company; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Savoca M, Miller C. Food selection and eating patterns: themes found among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Nutrition Education. 2001;33(4):224–233. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell K, Naimark B, McClement S. Influential factors for self-care in ambulatory care heart failure patients: a qualitative perspective. Canadian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2005;16(1):13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman-Green D, Jaser S, Martin F, Alonzo A, Grey M, McCorkle R, Redeker N, Reynolds N, Whittemore R. Processes of self-management in chronic illness. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2012;44(2):136–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01444.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M, Lee M, Shim B. Barriers to and facilitators of self-management adherence in Korean older adults with type 2 diabetes. International Journal of Older People Nursing. 2010;5(3):211–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2009.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz SW, Steeves RH, Wenzel J, Hinton I, Jones RA, Andrews D, Oliver MN. ‘Working Hard With It’: Self-management of type 2 diabetes by rural African Americans. Family & Community Health. 2006;29(3):195–205. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vest BM, Kahn LS, Danzo A, Tumiel-Berhalter L, Schuster RC, Karl R, Fox CH. Diabetes self-management in a low-income population: impacts of social support and relationships with the health care system. Chronic Illness. 2013;9(2):145–55. doi: 10.1177/1742395313475674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warsi A, Wang PS, LaValley MP, Avom J, Solomon DH. Self-management education programs in chronic disease. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;164(15):1641–1649. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.15.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellard SJ, Rennie S, King R. Perceptions of people with type 2 diabetes about self-management and the efficacy of community based services. Contemporary Nurse. 2008;29(2):218–226. doi: 10.5172/conu.673.29.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters CA, Cudney SA, Sullivan T, Thuesen A. The rural context and women’s self-management of chronic health conditions. Chronic Illness. 2006;2(4):273–289. doi: 10.1177/17423953060020040801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortz K, Cade A, Menard JR, Lurie S, Lykens K, Bae S, Coultas D. A qualitative study of patients’ goals and expectations for self-management of COPD. Primary Care Respiratory Journal: Journal of the General Practice Airways Group. 2012;21(4):384–391. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2012.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu FL, Juang JH, Yeh MC. The dilemma of diabetic patients living with hypoglycaemia. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2011;20(15–16):2277–2285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Verhoef MJ. Illness management strategies among Chinese immigrants living with arthritis. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55(10):1795–1802. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.