Abstract

Background

A recent prospective randomized trial demonstrated that prophylactic pasireotide reduces the incidence of pancreatic complications (PC) following resection. In this secondary analysis, we aimed to describe quality of life (QoL) before and after resection, characterize the impact of PC on QoL, and assess whether pasireotide improves QoL.

Methods

We conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of preoperative pasireotide in patients undergoing pancreatectomy. Participants completed the EORTC C30 and PAN26 modules preoperatively and on postoperative days 14 and 60. Scores were compared using t-tests. Percent of patients with clinically important worsening (a decline ≥0.5 times the baseline standard deviation) was reported.

Results

Eighty-seven percent of patients (260/300) completed all questionnaires. No major differences were observed between the pasireotide and placebo groups, therefore the data was pooled for further analyses. A significant worsening of function at 14D was detected on all PAN26 and C30 function scales except hepatic and emotional functioning (EF), and all C30 symptom scales. More than 75% of patients experienced clinically important worsening of fatigue, pain and role functioning. Most effects persisted at 60D. 60D EF was significantly better than baseline (p=0.03). PC were associated with worse outcomes on most function scales.

Conclusions

During the 14D following resection, patients can be expected to have a significant decline in QoL. Many symptoms abate by 60D, and EF improves. PC were associated with impaired QoL on several domains. Although pasireotide effectively reduced PC, its effect did not appear to translate to improved QoL in this sample of 300 patients.

Introduction

Quality of life is becoming increasingly central to medical decision-making in even the most aggressive and aggressively-treated cancers and in settings where life expectancy is short. Among patients with resectable pancreatic cancer, prognosis remains poor with 5 year overall survival of 10-20%. 1,2 Little data exists in the literature regarding quality of life for pancreatic cancer patients, especially in the weeks and months following pancreatic resection, which carries a substantial risk of short and long term morbidity and often requires a prolonged recovery period. 3 High-quality data demonstrating the effects of resection on quality of life from the perspective of the patient is invaluable for patient counseling and management. Previous studies have shown that familiarity with the expected post-surgical experience can reduce patients' surgical anxiety. 4,5 In addition, such data would highlight common issues experienced during the post-surgical period that may call for monitoring or intervention, set a baseline for “normal” levels of morbidity, and inform comparisons between treatment options. 3

As the need for quality of life assessment in pancreatic cancer became clear, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) developed a pancreatic cancer-specific module, the PAN26, to complement their widely-used quality of life instrument for cancer patients, the QLQ-C30. 6 The instrument has completed the EORTC module development process and is becoming the most commonly-used pancreatic-specific quality of life instrument. 7-9

Despite the obvious benefits of quality of life data generated from patients directly, patient reported outcomes are often hard to interpret because in many cases, the measurement scales do not carry intrinsic meaning. For example, a score of 20 on the PAN26 pain scale carries no built-in interpretation as normal, good, or poor, thus a reader cannot picture what level of symptoms it represents. In this analysis, we aimed to describe quality of life prior to pancreatic resection and in the two subsequent months, using a large, high-quality, prospectively collected Phase III trial dataset. We also attempted to enhance the interpretability of the quality of life outcomes through the use of data-driven anchors, which allow us to identify patients who experience a meaningful change from baseline in a given domain (clinically important worsening) versus an immaterial change. The primary analysis of this clinical trial demonstrated that pasireotide reduces pancreatic complications. 10 In this analysis, we were interested in the effect of complications on quality of life, and whether the confirmed efficacy of pasireotide to reduce complications would translate to improved quality of life.

Methods

Patients and Study Design

This is a secondary analysis of data collected in a Phase III, single center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of preoperative subcutaneous pasireotide to reduce pancreatic complications.10 The trial was approved by the institutional review board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Eligible patients were those undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy with or without splenectomy. Patients with a preoperative serum glucose level > 250 mg/dL, an international normalized ratio > 1.5, or a history of clinically significant cardiac disease were excluded. Randomization was stratified by operation performed (pancreaticoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy) and by the presence of preoperative pancreatic duct dilation (dilation was defined as a main-duct diameter of > 4mm at the site of pancreatic transection on preoperative imaging). 900 μg of pasireotide or placebo was administered subcutaneously twice daily starting on the morning of surgery and continuing for 7 days (14 doses). Patients were followed for surgical complications for 60 days using the MSKCC Surgical Secondary Events system. The primary endpoint was pancreatic complications, defined as grade 3 or higher pancreatic fistula, pancreatic anastomotic leak, or intraabdominal abscess.

Quality of Life Assessment

Quality of life was assessed preop and at 14 and 60 days postop using the EORTC QLQ-C30, which assesses quality of life issues relevant to all cancer patients, and the PAN26, which addresses symptoms, treatment side-effects and emotional issues specific to pancreatic cancer. Surveys were completed in person at scheduled clinic visits. The C30 consists of 28 four-level Likert items, and 2 seven-level Likert items, and the PAN26 consists of 26 four-level Likert items. Both instruments inquire about quality of life at present or during the past week.

Statistical Analysis

C30 Items were scored according the EORTC scoring procedures to create 6 function scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, social and global health status/QoL) and 9 symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea and financial difficulties). PAN26 items were scored according to draft scoring procedures supplied by the EORTC to create one function scale (satisfaction with health care) and 6 symptom scales (pain, digestive symptoms, altered bowel habit, hepatic, body image and sexuality). 11 Higher scores are better for function scales and worse for symptom scales. The internal consistency of the hypothesized PAN26 scales was verified using Cronbach's alpha.

Scales were summarized using mean and standard deviation, and compared across groups using t-tests. (For post-op time points, scores were standardized by subtracting baseline score.) Differences between baseline and postop scores were assessed using paired t-tests. For items that are not part of a scale, we reported the percent of patients reporting any extent of symptoms (a little, quite a bit or very much).

Clinically important worsening in score was defined for each domain as a worsening in score of at least 0.5 times the baseline standard deviation (baseline standard deviations are presented in Figures 1-3). Clinically important worsening is meant to capture differences that a patient would perceive as important, and has been found to correspond with what clinicians would deem a “moderate” or larger effect. 12 All statistical analysis was performed in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Two-sided p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

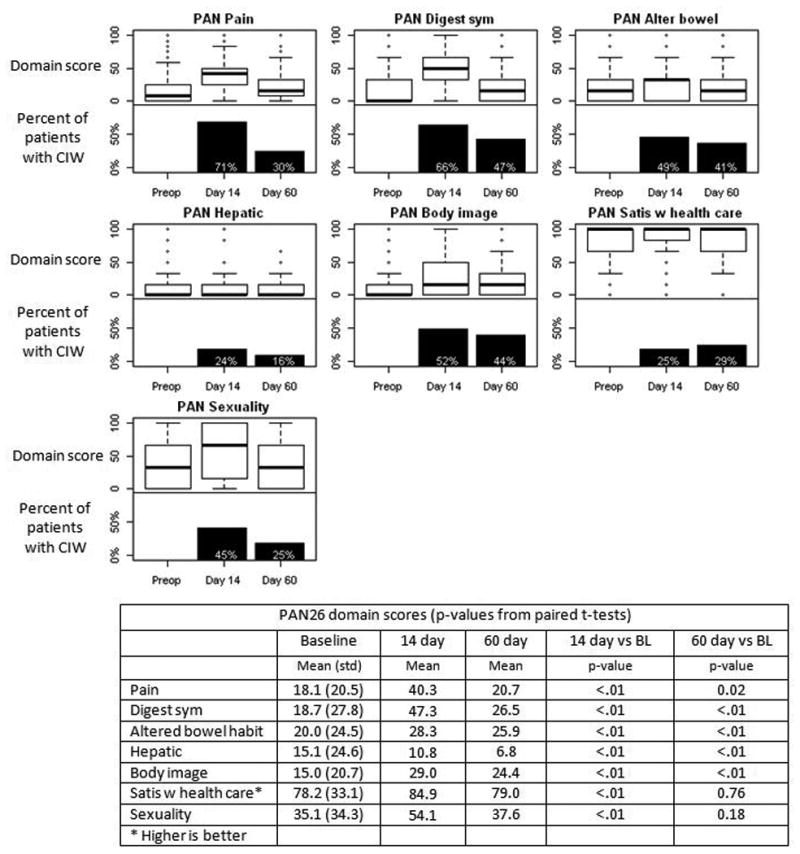

Figure 1.

Quality of life on PAN26 domains following pancreatic resection. Each plot includes a boxplot of domain score (top half) and the percent of patients with a clinically important worsening (CIW) in score compared with preop (bottom half). For satisfaction with health care, higher scores are better.

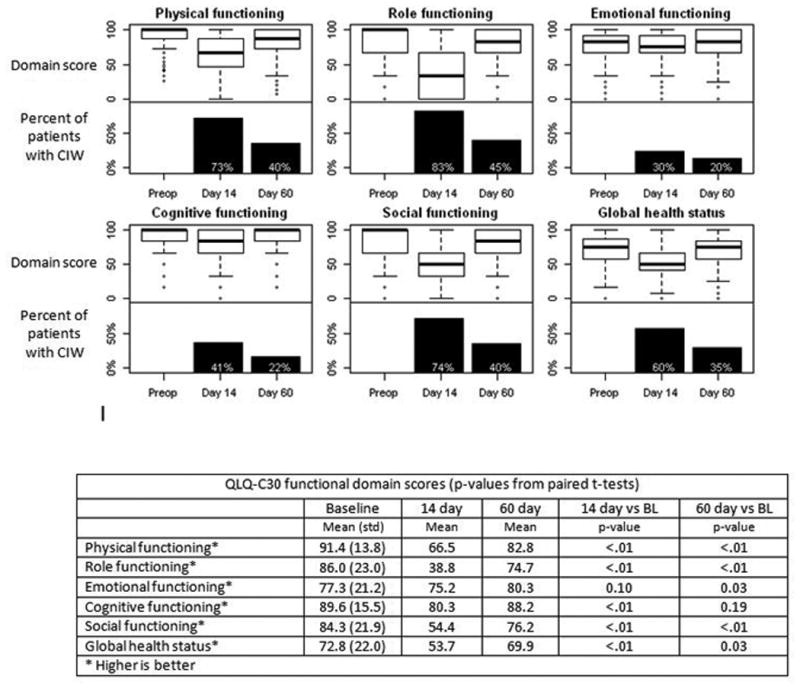

Figure 3.

Quality of life on QLQ-C30 functioning domains following pancreatic resection. Each plot includes a boxplot of domain score (top half) and the percent of patients with a clinically important worsening in score compared with preop (bottom half).

Results

Survey completion

Characteristics of the 300 evaluable patients have been described previously. 10 Questionnaires were completed at all time points by 87% patients (260/300) and at each time point by 299, 273 and 265 patients, respectively. Preop, 14 and 60 day questionnaires were completed at a median of 6 days before surgery (range = 0-40), 16 days postop (range = 8-49) and 62 days postop (range = 39-112). Although some items were skipped, at least 76% of patients completed each domain. The least-completed domain was PAN26 Sexuality.

Randomized comparisons

The internal consistency of the PAN26 scales was assessed with standardized Cronbach's alpha and found to be adequate for all domains except hepatic (data not shown). As expected, preop QoL was similar in the randomization groups (Table 1). In addition, no significant difference was observed in any of the PAN26 domains between pasireotide and placebo, at either 14 or 60 days postop (all p >0.05, Table 1). Shifting our focus to the QLQ-C30, pasireotide was associated with constipation at 60 days (p=0.04) and social functioning at 14 days (p=0.01). Pasireotide was not significantly associated with any other scale at 14 days or 60 days (all p>0.09, Table 1). Because only two significant differences were observed and because the differences were not consistent over time and the significance of these results would not stand up to adjustment for multiple comparisons, the placebo and pasireotide groups were combined for further analyses.

Table 1.

Baseline quality of life domain scores on PAN26 and QLQ-C30 and tests of the effect of pasireotide on quality of life. P-values are from t-tests of scores (baseline) and t-tests of differences in scores from baseline (14 and 60 day)

| Mean baseline score | Pasireotide vs placebo p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAN26 domains | Pasireotide (N=152) |

Placebo (N=148) |

Overall (N=300) |

Baseline | 14 day | 60 day |

| Pain | 17.3 | 19.1 | 18.1 | 0.44 | 0.88 | 0.55 |

| Digestive symptoms | 19.9 | 17.5 | 18.7 | 0.45 | 0.09 | 0.44 |

| Altered bowel habit | 21.3 | 18.7 | 20.0 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.66 |

| Hepatic | 16.3 | 13.9 | 15.1 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.95 |

| Body image | 15.6 | 14.4 | 15.0 | 0.63 | 0. 09 | 0. 31 |

| Satisfaction with health care* | 79.0 | 77.5 | 78.2 | 0.70 | 0.37 | 0.93 |

| Sexuality | 35.2 | 35.0 | 35.1 | 0.95 | 0.06 | 0.76 |

| QLQ-C30 domains | ||||||

| Physical functioning* | 92.4 | 90.4 | 91.4 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.80 |

| Role functioning* | 86.3 | 85.7 | 86.0 | 0.82 | 0.28 | 0.19 |

| Emotional functioning* | 77.0 | 77.6 | 77.3 | 0.80 | 0.31 | 0.22 |

| Cognitive functioning* | 89.7 | 89.5 | 89.6 | 0.91 | 0.11 | 0.42 |

| Social functioning* | 84.7 | 84.0 | 84.3 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 0.15 |

| Global health status* | 73.1 | 72.4 | 72.8 | 0.78 | 0.09 | 0.54 |

| Fatigue | 23.7 | 24.8 | 24.3 | 0.65 | 0.23 | 0.28 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 7.2 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 0.82 | 0.13 | 0.36 |

| Pain | 11.8 | 15.7 | 13.7 | 0.12 | 0.97 | 0.49 |

| Dyspnea | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 0.97 | 0.71 | 0.27 |

| Insomnia | 23.0 | 24.8 | 23.9 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.61 |

| Appetite loss | 18.8 | 17.8 | 18.3 | 0.76 | 0.11 | 0.24 |

| Constipation | 11.3 | 14.5 | 12.9 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0.04 |

| Diarrhea | 11.6 | 9.7 | 10.6 | 0.39 | 0.93 | 0.89 |

| Financial difficulties | 12.9 | 11.1 | 12.0 | 0.52 | 0.70 | 0.84 |

Means and p-values based on complete data. Scores range from 0 to 100.

indicates that a higher score is better. In all other cases a lower score is better.

QoL trajectory following pancreatic resection

A significant worsening of function was detected on all PAN26 scales except satisfaction and hepatic at 14 days (Figure 1). At that time, 71% of patients experienced clinically important worsening in score on the PAN26 pain scale and 66% experienced clinically important worsening on the digestive symptoms scale; the percentage with clinically important worsening on other scales ranged from 24%-52%. Significant differences persisted at 60 days for most scales (pain, digestive symptoms, altered bowel habit and body image), while sexuality returned to within 3 points of baseline. Scores at 14 and 60 days were significantly better than baseline for the hepatic domain, although internal consistency at these time points was questionable.

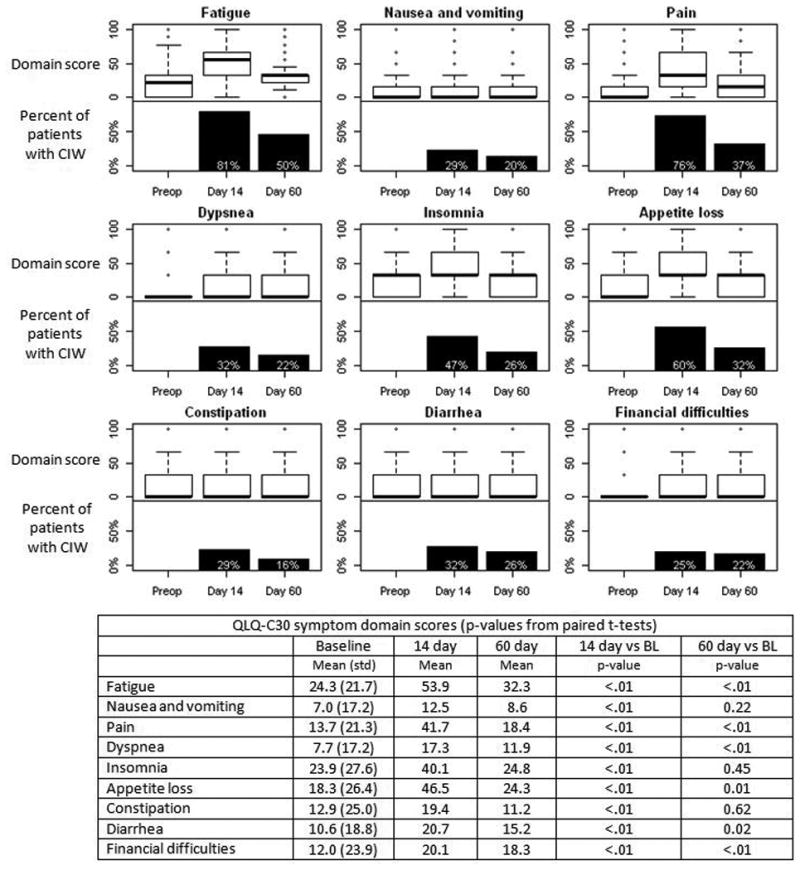

Within the QLQ-C30 at 14 days postop, scores were significantly worse than baseline in all functioning domains except emotional (physical, role, cognitive, social and global health status) and all symptom domains (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea and financial difficulties) (Figures 2 and 3). The domains with the most patients experiencing clinically important worsening at 14 days were role functioning (83% of patients), fatigue (81%), and physical and social functioning and pain (about 75%). By 60 days, cognitive functioning, nausea and vomiting, insomnia and constipation were no longer significantly worse than baseline, and there was no scale where more than 50% of patients still had clinically important worsening compared to baseline. Emotional functioning actually improved between 14 and 60 days to become significantly better than baseline (p=0.03).

Figure 2.

Quality of life on QLQ-C30 symptom domains following pancreatic resection. Each plot includes a boxplot of domain score (top half) and the percent of patients with a clinically important worsening in score compared with preop (bottom half).

Fourteen items are not used in the scoring of any domain. The percent of patients experiencing problems in these areas is presented in Supplemental Table 1. Patients were more likely to report problems at 14 days than at baseline or 60 days. Some extent of future health worry was present in a high proportion of patients (85% or more across all time points).

Effect of pancreatic complications

Pancreatic complications were associated with worse body image, physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning, fatigue, C30 pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, and financial difficulties at 14 days (Table 2). Differences in clinically important worsening were especially pronounced for social functioning (93% of patients with complications had clinically important worsening at 14 days, compared to 72% of patients without complications), dyspnea (59% vs 29%) and financial difficulties (60% vs 21%). Differences in most of these domains were also seen at 60 days, and additionally, constipation and sexuality scores were worse in patients with pancreatic complications,

Table 2.

Mean PAN26 and QLQ-C30 domain scores for patients with and without pancreatic complications prior to survey completion and percent of patients with clinically important worsening (CIW). P-values from t-test of difference in score from baseline. 28 patients with PC and 245 without completed the 14 day questionnaire and 36 patients with PC and 229 without completed the 60 day questionnaire.

| Mean score | % with CIW | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAN26 domains | No PC | PC | No PC | PC | |

| Pain | |||||

| 14 day | 39.4 | 48.2 | 70% | 79% | 0.09 |

| 60 day | 20.0 | 25.2 | 29% | 36% | 0.23 |

| Digestive symptoms | |||||

| 14 day | 47.21 | 48.2 | 68% | 54% | 0.94 |

| 60 day | 26.2 | 28.2 | 47% | 47% | 0.77 |

| Alter bowel | |||||

| 14 day | 27.3 | 36.3 | 48% | 64% | 0.60 |

| 60 day | 25.2 | 30.1 | 42% | 36% | 0.78 |

| Hepatic | |||||

| 14 day | 11.0 | 9.5 | 26% | 11% | 0.94 |

| 60 day | 6.5 | 8.3 | 15% | 22% | 0.37 |

| Body image | |||||

| 14 day | 28.2 | 35.1 | 51% | 57% | <.01 |

| 60 day | 23.0 | 33.3 | 40% | 69% | <.01 |

| Satisfaction with health care* | |||||

| 14 day | 84.7 | 86.3 | 25% | 24% | 0.76 |

| 60 day | 78.5 | 81.9 | 31% | 20% | 0.34 |

| Sexuality | |||||

| 14 day | 52.2 | 69.0 | 43% | 65% | 0.12 |

| 60 day | 34.5 | 56.3 | 20% | 53% | <.01 |

| QLQ-C30 domains | |||||

| Physical functioning* | |||||

| 14 day | 68.2 | 50.9 | 73% | 81% | <.01 |

| 60 day | 84.1 | 74.3 | 36% | 67% | <.01 |

| Role functioning* | |||||

| 14 day | 40.7 | 21.6 | 83% | 85% | 0.01 |

| 60 day | 77.1 | 59.3 | 43% | 56% | 0.03 |

| Emotional functioning* | |||||

| 14 day | 75.3 | 74.2 | 29% | 41% | <.01 |

| 60 day | 80.5 | 79.1 | 18% | 31% | <.01 |

| Cognitive functioning* | |||||

| 14 day | 80.9 | 75.3 | 40% | 52% | 0.03 |

| 60 day | 88.2 | 88.4 | 22% | 22% | 0.49 |

| Social functioning* | |||||

| 14 day | 56.9 | 32.1 | 72% | 93% | <.01 |

| 60 day | 78.6 | 61.1 | 36% | 67% | <.01 |

| Global health status* | |||||

| 14 day | 55.1 | 41.7 | 59% | 70% | 0.12 |

| 60 day | 71.5 | 60.0 | 33% | 47% | 0.15 |

| Fatigue | |||||

| 14 day | 52.3 | 68.3 | 80% | 89% | <.01 |

| 60 day | 30.8 | 41.1 | 50% | 53% | 0.12 |

| Nausea and vomiting | |||||

| 14 day | 11.4 | 22.8 | 27% | 41% | 0.14 |

| 60 day | 8.7 | 7.9 | 21% | 17% | 0.29 |

| Pain | |||||

| 14 day | 39.9 | 57.4 | 75% | 81% | 0.01 |

| 60 day | 17.8 | 22.2 | 35% | 50% | 0.75 |

| Dyspnea | |||||

| 14 day | 15.4 | 34.6 | 29% | 59% | <.01 |

| 60 day | 10.8 | 19.0 | 20% | 48% | 0.04 |

| Insomnia | |||||

| 14 day | 39.4 | 46.9 | 46% | 63% | 0.06 |

| 60 day | 23.9 | 30.6 | 25% | 33% | 0.25 |

| Appetite loss | |||||

| 14 day | 43.7 | 73.1 | 58% | 85% | <.01 |

| 60 day | 23.1 | 32.4 | 31% | 37% | 0.18 |

| Constipation | |||||

| 14 day | 19.8 | 15.4 | 30% | 19% | 0.88 |

| 60 day | 10.1 | 18.5 | 14% | 28% | 0.04 |

| Diarrhea | |||||

| 14 day | 19.3 | 33.3 | 31% | 46% | 0.15 |

| 60 day | 15.4 | 13.9 | 27% | 20% | 0.10 |

| Financial difficulties | |||||

| 14 day | 18.2 | 37.3 | 21% | 60% | <.01 |

| 60 day | 16.8 | 27.6 | 20% | 38% | <.01 |

Higher is better

Discussion

Overall, we found that during the 14 days following resection, patients experience a significant decline in quality of life. By 60 days, symptoms abate but generally remained significantly worse than baseline, and emotional functioning was significantly better than baseline. The areas of quality of life that were especially affected were pain, digestive symptoms, fatigue, physical, role and social functioning. In each of these areas more than 65% of patients experienced clinically important worsening at 14 days. Our data sheds light on the period of time required for recovery following resection. Results are in line with previous studies that reported worse quality of life immediately after surgery followed by a slow recovery to baseline or better by 3-6 months postop. 13-15

We found that pancreatic complications were associated with worse body image, dyspnea, financial difficulties, physical, role, emotional and social functioning at 14 and 60 days. While impaired quality of life in the weeks following resection and impaired quality of life associated with pancreatic complications are both to be expected, our data allows us to quantify the extent of impairment that patients actually experience. It is also worth noting that the impact of complications on quality of life persists for at least two months after the operation.

Although the primary analysis of this trial showed that pasireotide reduced the rate of pancreatic complications from 21% to 9%, and the analysis presented here revealed that complications were associated with decline in several quality of life domains, this did not appear to translate to measurably better quality of life in this sample. This may be due to the fact that the majority of patients in both the placebo and pasireotide groups did not experience pancreatic complications. Although we can rule out a large effect of pasireotide on quality of life, a study with a larger sample size may have sufficient power to detect a small to moderate effect.

Future health worry was high with more that 85% of patients reporting some extent of worry across all three time points, as would be expected in the setting of a disease with high mortality. Patients reported significantly more financial difficulty after surgery compared to before and also more difficulty in the presence of pancreatic complications. Although financial difficulties experienced by cancer patients are well-documented, it is interesting that the level of concern changed with complications and over time. 16 Satisfaction with health care was generally high, and highest at 14 days postop, probably because patients would have frequent interactions their healthcare team often in the days immediately after surgery, and memories of these positive experiences of being cared for would be most recent at 14 days. Interestingly, emotional functioning was the only scale that significantly improved over time. (Hepatic also improved but there were issues regarding the reliability of the scale.) This is may be due to the fact that patients are less anxious after their surgery has been successfully completed.

Strengths of this study include the use of a large (300 patient), high-quality RCT dataset with high survey completion rates and the use of a disease-specific instrument that is focused on issues unique to pancreatic cancer. As there is little published data from trials that utilized the PAN26 instrument, this work provides useful background data for future researchers. In addition, while the C30 and PAN26 scores themselves do not carry intrinsic meaning, we believe that the use of clinically important worsening may make them more interpretable, as this calculation is designed to represent a worsening in score large enough to be perceived as important by the patient.

One limitation of this analysis is that data was only collected for two months following resection. With longer follow-up, we likely would have seen more domain scores return to baseline levels. Shaw et al used the C30 and PAN26 instruments to assess quality of life in an unselected cohort of patients at a median of 42 months after pancreaticoduodenectomy and found that their scores compared favorably to controls undergoing cholecystectomy with some differences suggestive of exocrine insufficiency. 17 In addition, in this analysis we were unable to confirm the internal consistency of the hepatic scale of the PAN26, while the other scales had adequate internal consistency. The PAN26 instrument has not been validated in a large international cohort of patients, and future studies are needed to enhance understanding of its properties and thoroughly assess its reliability and validity.

In conclusion, this study used empirical data to characterize the decrease in QOL following pancreatectomy as reported by patients themselves. During the two weeks following resection, patients can be expected to have a significant decline in QoL. These data suggest that many symptoms abate by 60D, and EF improves. A measurable decrease in QOL was observed in patients who experienced pancreatic complications, however the decrease in pancreatic complications observed in the group who received pasireotide did not translate to a measurable improvement in QOL.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1: Percent of patients experiencing these problems to any extent (a little, quite a bit or very much). These items do not contribute to any scale.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Cancer Center core grant P30 CA008748. The core grant provides funding to institutional cores such as Biostatistics, which was used in this study.

Footnotes

Disclosures: This research was funded by Novartis. Dr Allen has worked in a consulting/advisory role for Sanofi and received research funding from Novartis.

References

- 1.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer of the head of the pancreas. 201 patients. Annals of surgery. 1995 Jun;221(6):721–731. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199506000-00011. discussion 731-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Piccoli A, Pedrazzoli S. Survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. British Journal of Surgery. 1996;83(5):625–631. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Numico G, Longo V, Courthod G, Silvestris N. Cancer survivorship: long-term side-effects of anticancer treatments of gastrointestinal cancer. Current opinion in oncology. 2015 Jul;27(4):351–357. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spalding NJ. Reducing anxiety by pre-operative education: make the future familiar. Occupational Therapy International. 2003;10(4):278–293. doi: 10.1002/oti.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson CJ, Mitchelson AJ, Tzeng TH, et al. Caring for the surgically anxious patient: a review of the interventions and a guide to optimizing surgical outcomes. American journal of surgery. 2015 Jun 2; doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzsimmons D, Johnson CD, George S, et al. Development of a disease specific quality of life (QoL) questionnaire module to supplement the EORTC core cancer QoL questionnaire, the QLQ-C30 in patients with pancreatic cancer. EORTC Study Group on Quality of Life. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 1999 Jun;35(6):939–941. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.EORTC. [June 1, 2015];Modules in development and available for use. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/modules-development-and-available-use.

- 8.Keck T, Wellner UF, Bahra M, et al. Pancreatogastrostomy Versus Pancreatojejunostomy for RECOnstruction After PANCreatoduodenectomy (RECOPANC, DRKS 00000767): Perioperative and Long-term Results of a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Annals of surgery. 2015 Jul 1; doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moningi S, Walker AJ, Hsu CC, et al. Correlation of clinical stage and performance status with quality of life in patients seen in a pancreas multidisciplinary clinic. Journal of oncology practice / American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015 Mar;11(2):e216–221. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.000976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen PJ, Gönen M, Brennan MF, et al. Pasireotide for Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(21):2014–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Group EQoL. Draft scoring procedure for the EORTC-PAN26. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical care. 2003 May;41(5):582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crippa S, Dominguez I, Rodriguez JR, et al. Quality of life in pancreatic cancer: analysis by stage and treatment. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2008 May;12(5):783–793. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0391-9. discussion 793-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nieveen van Dijkum EJ, Kuhlmann KF, Terwee CB, Obertop H, de Haes JC, Gouma DJ. Quality of life after curative or palliative surgical treatment of pancreatic and periampullary carcinoma. The British journal of surgery. 2005 Apr;92(4):471–477. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schniewind B, Bestmann B, Henne-Bruns D, Faendrich F, Kremer B, Kuechler T. Quality of life after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. The British journal of surgery. 2006 Sep;93(9):1099–1107. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNulty J, Khera N. Financial Hardship—an Unwanted Consequence of Cancer Treatment. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2015/06/26. 2015:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11899-015-0266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw CM, O'Hanlon DM, McEntee GP. Long-term quality of life following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepato-gastroenterology. 2005 May-Jun;52(63):927–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1: Percent of patients experiencing these problems to any extent (a little, quite a bit or very much). These items do not contribute to any scale.