Abstract

Pediatric Crohn's Disease (CD) is associated with low trabecular bone mineral density (BMD), cortical area, and muscle mass. Low magnitude mechanical stimulation (LMMS) may be anabolic. We conducted a 12 month randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 10 minutes daily exposure to LMMS (30 Hz frequency, 0.3 g peak to peak acceleration). The primary outcomes were tibia trabecular BMD and cortical area by peripheral quantitative CT (pQCT) and vertebral trabecular BMD by QCT; additional outcomes included DXA whole body, hip and spine BMD, and leg lean mass. Results were expressed as sex-specific Z-scores relative to age. CD participants, ages 8-21 years with tibia trabecular BMD < 25th percentile for age were eligible and received daily cholecalciferol (800 IU) and calcium (1,000 mg). In total, 138 enrolled (48% male) and 121 (61 active, 60 placebo) completed the 12-month trial. Median adherence measured with an electronic monitor was 79% and did not differ between arms. By intention-to-treat analysis, LMMS had no significant effect on pQCT or DXA outcomes. The mean change in spine QCT trabecular BMD Z-score was +0.22 in the active arm and −0.02 in the placebo arm [difference in change 0.24 (95% CI 0.04, 0.44); p=0.02]. Among those with > 50% adherence, the effect was 0.38 (0.17, 0.58, p<0.0005). Within the active arm, each 10% greater adherence was associated with a 0.06 (0.01, 1.17, p=0.03) greater increase in spine QCT BMD Z-score. Treatment response did not vary according to baseline BMI Z-score, pubertal status, CD severity, or concurrent glucocorticoid or biologic medications. In all participants combined, height, pQCT trabecular BMD and cortical area and DXA outcomes improved significantly. In conclusion, LMMS was associated with increases in vertebral trabecular BMD by QCT; however, no effects were observed at DXA or pQCT sites.

Keywords: Clinical Trials, Bone QCT, DXA, anabolics, skeletal muscle

INTRODUCTION

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract associated with defective innate immune regulation. Children and adolescents with CD have multiple risk factors for impaired bone accrual, including poor growth, delayed puberty, malnutrition, cachexia, decreased physical activity, chronic inflammation, and glucocorticoid therapy.(1, 2) Impaired bone accrual in childhood inflammatory diseases poses an immediate fracture risk, and low peak bone mass may result in life-long skeletal fragility.(3-5) We previously established an incident cohort of children with CD and documented substantial deficits in tibia trabecular bone mineral density (BMD), cortical dimensions and muscle mass at diagnosis.(6) Despite marked improvements in disease activity during therapy, significant musculoskeletal deficits persisted years later.(7) Glucocorticoid therapy and inflammation were independently associated with impaired trabecular and cortical bone accrual. In contrast, greater gains in muscle mass were associated with greater increases in cortical bone area.

The growing skeleton is able to modify its structure and strength in response to biomechanical loading induced by functional activity.(8, 9) As a surrogate to exercise, brief daily exposure to low-magnitude mechanical stimuli (LMMS) has shown potential as a non-pharmacologic bone therapy with anabolic and anti-resorptive properties;(10) however, its efficacy in metabolic disease in not known. LMMS involves standing on an oscillating platform that transmits vertical accelerations well below 1 g (earth's gravitational field, 9.8 m/s2) to weight-bearing bones. Animal studies demonstrated LMMS efficacy in growing bones, resulting in gains in trabecular bone volume fraction and cortical area.(11-13) Furthermore, LMMS preserved trabecular bone structure in rats treated with glucocorticoids.(14)

Translating to the clinic, randomized trials in children, adolescents and young adults have reported beneficial effects, including a study conducted in 48 otherwise healthy young women (ages 15-20 years) with low BMD and a history of fracture,(15) a study in 20 ambulatory children with disabling conditions (e.g. cerebral palsy),(16) a study in 31 children with cerebral palsy,(17) and a study in 124 young women (ages 15-25 years) with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and low BMD.(18) The intervention has not been evaluated in an inflammatory condition or as a means to counter the adverse skeletal effects of glucocorticoid therapy. We hypothesized that 12 months of daily 10 minute exposure to LMMS (0.3g, 30 Hz) in children and adolescents with CD would have beneficial effects on trabecular volumetric BMD (vBMD) in the tibia and spine, and on cortical area in the tibia diaphysis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This single center, two arm, double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial (RCT) was conducted at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) to evaluate the effects of daily 10 minute exposure to LMMS in children and adolescents with CD, compared with use of a placebo device over a 12 month interval. The Clinicaltrials.gov identifier is NCT00364130.

Participants were recruited from 2007 to 2010 from gastroenterology clinics at CHOP and in the greater Delaware Valley, the annual CHOP Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center Family Day, and advertisements on the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation website. The inclusion criteria were ages 8 to 21 years, a diagnosis of CD at least six months prior due to rapid musculoskeletal changes early after diagnosis(6), and a tibia peripheral quantitative CT (pQCT) trabecular vBMD < 25th percentile (Z-score = −0.67) for age, sex and race, compared with CHOP reference data in 652 healthy participants.(7, 19) Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, weight > 250 pounds (limit of the LMMS device), medical illness unrelated to CD with potential adverse effects on bone or body composition, plans to travel more than four weeks over the study interval, a sibling or acquaintance enrolled in the trial (due to potential threats to blinding), and developmental disorders prohibiting completion of study procedures.

The protocol was approved by the CHOP Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from study participants over age 18, and assent and parental consent from those less than 18 years of age. The FDA has designated the LMMS signal and platform as a non-significant risk device.

Interventions, Randomization, Measures of Adherence, and Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation

The LMMS device used in prior studies was used for this trial.(15, 16) In order to deliver LMMS to the weight-bearing skeleton, the platform was designed to use closed-loop accelerometer feedback to closely control vertical, sinusoidal accelerations of the top platen. The top plate of the platform accelerated at 0.3g, peak to peak, at a frequency of 30 Hz through a low force (18N) coil actuator. Maximum displacement of the platen remained below 100 microns at all times. Acceleration at this frequency is considered safe for up to four hours daily, as defined by the International Organization for Standardization and Occupational Safety and Health Administration recommendations.(20) Subjects were instructed to stand upright with legs straight on the platform for 10 minutes daily, either barefoot or wearing socks. No exercises were performed on the device. To help mask active/placebo status, all platforms were equipped with a speaker that emitted an audible buzzing sound.

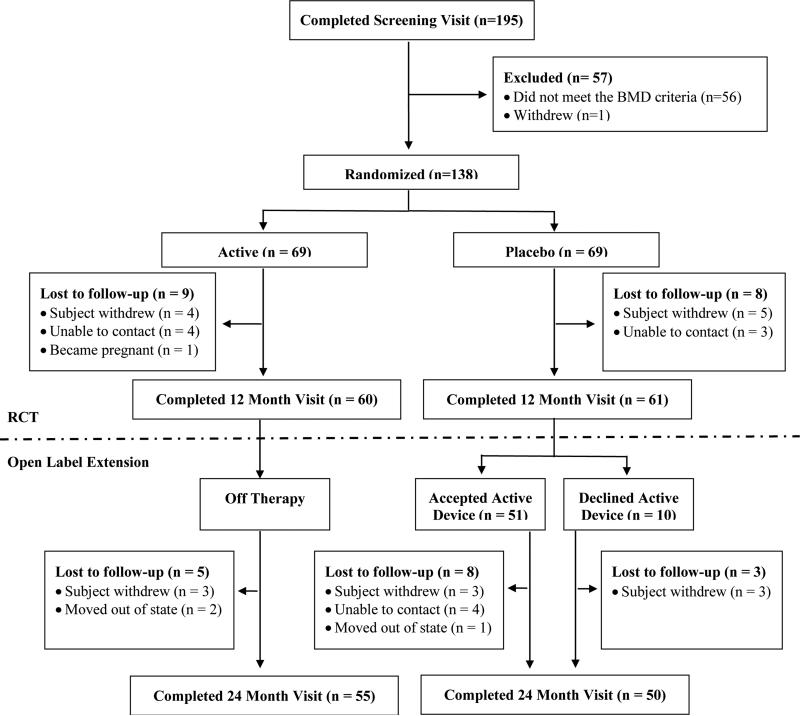

Eligible participants were randomly allocated 1:1 to an active or placebo device using Stata's random number generator and a block randomization with four strata according to sex and pubertal status (Tanner stage 1-2 vs. 3-5). Randomization assignments were stored in sealed envelopes in the CHOP Clinical Trials Office (CTO). Following completion of the 12 month intervention, participants initially randomized to active LMMS were followed for an additional 12 months off therapy in an open label extension (Figure 1). Those initially randomized to placebo devices were offered an active device during the second 12 month interval. The primary motivation for the open label extension was to provide an incentive for enrollment as all participants ultimately had access to an active LMMS device.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Study Flow Diagram

The individual in the CTO that was responsible for randomization, managing the devices and instructing families in their use was not involved in any aspect of data collection. All other members of the investigative team (with the exception of the statistician who reviewed the safety reports) were blinded throughout the 24 months. Participants and their families were blinded to assignment through the 12 month visit. Upon completion of the 12 month visit, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire to determine if they thought their device was active or placebo.

Adherence was measured by an inboard monitor that documented date, time and duration of each use. This information was transmitted via modem to CHOP bi-weekly during the 12 month trial. The study psychologist (KH) contacted those with less than 80% adherence in any biweekly interval. Additional strategies to promote adherence included $1 per completed daily treatment and $10 in any month without missed treatments. Percent adherence was calculated as the number of minutes completed (maximum of 10 min/day) divided by the minutes prescribed. Incentives and feedback were not provided during the open label extension, and adherence data were downloaded at 24 months.

All participants were provided calcium (1000 mg/day of elemental calcium) and cholecalciferol (800 IU/day) supplements. Average calcium and vitamin D intake from non-food sources and enteral feeds were evaluated and the study dose adjusted to ensure the average daily intake did not exceed 2000 mg of calcium or 2000 IU of vitamin D. The supplements were continued during the extension.

Outcomes and Covariates

Study visits were completed at enrollment, 6, 12, and 24 months. Disease characteristics, medications, anthropometrics and Tanner stage were documented at each visit. CD activity was assessed using the Pediatric CD Activity Index (PCDAI) based on symptoms (30%), physical examination (30%), laboratory parameters (20%), and growth (20%), with scores from 0 to 100.(21) Clinical disease activity was categorized as inactive (1-10), mild (11-30), and moderate to severe (>30). Height was measured using a stadiometer (Holtain, Crymych, UK) and weight with a digital scale (Scaletronix, White Plains, New York). Pubertal development was assessed using a self-assessment questionnaire and classified according to Tanner stage.(22)

PQCT scans were obtained at each visit in the left tibia using a Stratec XCT2000 device (Orthometrix, White Plains, NY) with a 12 detector unit, voxel size 0.4 mm, slice thickness 2.3 mm and scan speed 25mm/sec. Bone measurements were obtained 3% proximal to the distal physis for trabecular vBMD (mg/cm3) and at the 38% diaphysis for cortical vBMD (mg/cm3), periosteal and endosteal circumference (mm), and cortical cross sectional area (mm2). Muscle and fat area (mm3) were assessed at the 66% site. The hydroxyapatite phantom was scanned daily. In our laboratory, the coefficient of variation (CV) ranged from 0.5 to 1.6% for pQCT outcomes.(23)

Spine QCT scans were obtained at baseline, 12 and 24 months using a Siemens Somatom Sensation 64 slice CT scanner. A low-dose scanning technique was utilized to achieve an effective dose equivalent of approximately 50 mrem. Scout views were obtained, followed by acquisition of L2 and L3 with a field of view (360 mm) that encompassed all soft tissue and the calibration phantom. CT scan parameters were 120 kV, 50 mAs, and matrix 512. The QCT PRO (Mindways Software, Inc.; San Francisco, CA) solid K2HPO4 bone equivalent calibration phantom was covered with gel bolus bags to eliminate air between phantom and patient, and the participant was positioned over the phantom. The phantom was used to transform CT Hounsfield Units within the trabecular region of interest into bone mineral equivalents (mg/cm3). Measurement precision is between 1 and 2 mg/cm3.

Given concerns regarding the precision of a single pQCT slice in the metaphysis in longitudinal studies in growing children,(24) a spiral QCT scan (1 mm slice thickness) was obtained over the length of the entire tibia at the time of the spine QCT scan. A summary measure of trabecular vBMD (mg/cm3) was obtained along a cylindrical region of interest placed within the inner margin of the cortex over the length of metaphysis. Trabecular vBMD was averaged across the length of the metaphysis, excluding 10% at each end.

DXA scans were performed at each visit using a Delphi/Discovery (Hologic, Bedford, MA, USA) densitometer. Whole body, posteroanterior (PA) lumbar spine (L1–L4), lateral lumbar spine (L2-4) and left proximal femur scans were obtained using standard techniques. Paired PA-lateral DXA scans of L3 were used to derive an estimate of vBMD:(25) the vertebral dimensions on the PA and lateral scans were used estimate vertebral volume assuming an elliptical shape, and vertebral body BMC measured on the lateral scan, thereby excluding the cortical spinous processes. The spine and whole body scans were analyzed with software version 12.3 and 12.4, respectively. The spine (CV < 1%) and whole body phantoms (CV < 2.5%) were scanned daily and weekly, respectively.

Calf muscle strength was assessed using Biodex System 3 Pro (Biodex Medical Systems, Inc., Shirley, NY). Peak isometric torque (ft-lbs) in dorsiflexion was measured in triplicate and the highest value recorded, as previously described.(2, 26) The CV was 4.3%.

Serum 25(OH) vitamin D levels were measured at each visit using tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with a CV% of 5%. Bone biomarkers were measured at baseline and 12 months. Serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP, mg/L) was measured as a marker of bone formation using a two-site immunoradiometric assay (CV 8%). Serum C-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen (β-CTX, pg/mL) was measured as a marker of resorption using an electrochemiluminescent assay (CV 5%).

Physical activity was measured with RT3 Triaxial accelerometers (Stayhealthy, Inc., Monrovia, CA, USA) worn for 1 week intervals quarterly, over the 12 month trial. A threshold of ≥ 977 counts/minute was used to designate moderate-to-vigorous intensity of physical activity (MVPA).(27) Daily averages of minutes of MVPA were calculated for each participant.

Safety was assessed at each study visit. Participants were asked to report any episodes of headache, dizziness, vision changes, motion sickness, abdominal pain, loose stools, nausea, back pain or joint pain since the prior visit. All hospitalizations were documented over the study interval.

Statistical Analysis

Anthropometric, tibia pQCT, spine QCT, DXA and bone biomarker outcomes were converted to Z-scores. Age- and sex- specific height and BMI Z-scores were generated using national data.(28) Bone biomarker results were converted to sex and Tanner stage specific Z-scores.(1, 29) DXA and pQCT outcomes were converted to race (black vs. all others) and sex-specific Z-scores relative to age using the LMS method (Chartmaker Program version 2.3) based on our data in over 600 healthy participants.(19, 30) The LMS method accounts for the non-linearity, heteroscedasticity and skew of bone and body composition data in growing children.(31, 32) DXA measures of PA spine, femoral neck and total hip areal BMD (aBMD), and whole body (less head) BMC were converted to Z-scores relative to age and adjusted for height Z-score.(33) DXA estimates of spine vBMD based on paired PA-lateral scans were expressed as Z-scores relative to age. Whole body DXA measures of fat mass and leg lean mass were converted to Z-scores relative to age and adjusted for leg length for age Z-score.(34, 35) The pQCT cortical and trabecular vBMD outcomes were assessed relative to age. The tibia cortical geometry, fat area, and calf muscle area and strength were assessed relative to age and adjusted for tibia length Z-score.(33, 36)

Our reference participants did not undergo QCT scans; therefore, the spine QCT trabecular vBMD results were converted to sex-specific Z-scores relative to age using normative data published by Gilsanz, et al. in 1222 healthy white children and adolescents.(37) The reported Gilsanz trabecular bone density (TBD, mg/cm3) reference values were converted to bone mineral density (in mg/cm3 K2HPO4 equivalents) by dividing TBD by 1.7.(38) In order to assess the generalizability of the Gilsanz normative data to our scanner and participants, we applied these norms to spine QCT scans obtained in 51 white and 53 black healthy children enrolled in a concurrent study at CHOP: the mean ± SD Z-scores were 0.28 ± 1.49 and 0.96 ± 1.40 in the white and black participants, respectively. Normative data were not available for the tibia QCT metaphyseal vBMD data; therefore, analyses were limited to the vBMD result rather than a Z-score.

The three pre-specified primary outcomes were the Z-scores for trabecular vBMD by tibia pQCT and spine QCT, and cortical area by tibia pQCT. Cortical area was selected as the primary measure of cortical structure given the high correlation (R2 0.77 to 0.85) with failure load in bone biomechanics studies.(39-41) The pre-specified secondary outcomes were DXA aBMD Z-scores and QCT tibia vBMD. Exploratory analyses examined DXA body composition, pQCT muscle area, muscle strength, and bone biomarkers. The intention to treat analyses used quasi-least squares regression (QLS; xtqls command in Stata) to examine the change in bone, body composition, muscle strength and biomarker Z-scores since baseline at each visit, adjusted for the baseline value.(42, 43) The pQCT, DXA, and dynamometer models used the baseline, 6 and 12 month data, while the QCT data were limited to baseline and 12 months. The models considered change since baseline as the outcome variable and included the following covariates: the baseline value of the outcome, an indicator variable for group (active versus placebo), and a covariate that represented time of measurement. In order to determine if the treatment response varied according to pre-specified variables (sex, concurrent glucocorticoid or infliximab therapy, and baseline Tanner stage, BMI-Z score and leg lean mass Z-score), interaction terms were tested in the QLS models. We confirmed that the results of the regression analyses did not change when the regressions were conducted using multiple imputation chained equations with the mi compute command in Stata. Two approaches were employed using the adherence data. The LMMS effect was examined in subgroups based on percent adherence (> 25%, > 50%, or > 75%), and the associations between changes in outcomes and percent adherence (as a continuous variable) were examined within the active and placebo arms using the QLS regression models described above.

The target enrollment was 160 participants, to achieve 12 month data in 144 (assuming 90% retention). The intra-subject correlation (ρ) exceeded 0.80 for all pQCT and DXA outcomes in our prior CD studies. Using the sample size formula by Diggle et al,(44) 144 participants would provide 80% power to detect an effect size (difference in change in Z-scores) of 0.26. The analysis plan did not include a correction for multiple comparisons as the outcomes are not independent of each other. Enrollment was discontinued after 138 participants were randomized due to the funding timeline.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

A total of 195 participants completed the screening visit and 139 (71%) were eligible; see Figure 1 for details. A total of 138 were randomized and 69 each were given active or placebo devices (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the participant and disease characteristics, and baseline bone and body composition results; none of these variables differed between treatment arms. The median age was 14 years and bone and muscle Z-scores ranged from a mean of −0.45 to −1.74.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Overall and by Treatment Arm

| Overall (n = 138) | Active (n = 69) | Placebo (N = 69) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 14 (8 – 21) | 13 (8 – 21) | 14 (8 – 21) | 0.43 |

| Sex, n (%) male | 66 (48) | 33 (48) | 33 (48) | 1.00 |

| Race, n (%) black | 8 (6) | 5 (7) | 3 (4) | 0.47 |

| Tanner stage 1-2, n (%) | 48 (35) | 24 (35) | 24 (35) | 0.89 |

| Height Z-score | −0.76 ± 1.01 | −0.78 ± 0.99 | −0.73 ± 1.03 | 0.75 |

| BMI Z-score | −0.25 ± 1.14 | −0.17 ± 1.14 | −0.33 ± 1.14 | 0.41 |

| Interval since Crohn's Disease diagnosis, y | 2.7 (0.5 – 19.6) | 2.7 (0.5 – 19.6) | 2.7 (0.5 – 11.8) | 0.87 |

| Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index | 10 (3 -18) | 8 (3-15) | 10 (3-18) | 0.35 |

| Inactive (< 10), n (%) | 85 (62) | 43 (62) | 42 (61) | 0.88 |

| Mild (11-30), n (%) | 46 (33) | 22 (32) | 24 (35 | |

| Moderate/Severe (>30), n (%) | 7 (5) | 4 (6) | 3 (4) | |

| Medications | ||||

| Systemic steroids (ever), n (%) | 108 (78) | 57 (83) | 51 (74) | 0.23 |

| Systemic steroids (at baseline), n (%) | 18 (13) | 9 (13) | 9 (13) | 0.97 |

| Anti-TNF-α biologics (ever), n (%) | 53 (39) | 25 (36) | 28 (41) | 0.53 |

| Anti-TNF-α biologic (at baseline), n (%) | 43 (31) | 22 (32) | 21 (30) | 0.95 |

| Physical activity, mean MVPA min/day | 64 ± 33 | 68 ± 31 | 60 ± 34 | 0.17 |

| Calf muscle strength Z-score | −0.43 ± 0.90 | −0.38 ± 0.90 | −0.48 ± 0.91 | 0.52 |

| Laboratory Parameters | ||||

| 25(OH) vitamin D, ng/mL | 31 ± 11 | 32 ± 12 | 31 ± 10 | 0.50 |

| 25(OH) vitamin D < 20 ng/mL, n (%) | 15 (11) | 6 (9) | 9 (14) | 0.41 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 0.44 |

| Hematocrit, % | 36.9 ± 3.6 | 36.9 ± 3.7 | 36.9 ± 3.6 | 0.97 |

| BSAP Z-score | −0.77 ± 1.31 | −0.76 ± 1.38 | −0.78 ± 1.24 | 0.92 |

| β-CTX Z-score | 0.28 ± 1.04 | 0.26 ± 1.08 | 0.31 ± 1.01 | 0.77 |

| DXA Z-scores | ||||

| PA spine aBMD | −1.05 ± 1.05 | −0.99 ± 0.96 | −1.10 ± 1.14 | 0.55 |

| Paired PA-Lateral spine vBMD | −0.68 ± 1.32 | −0.63 ± 1.18 | −0.73 ± 1.45 | 0.66 |

| Total hip aBMD | −1.21 ± 0.96 | −1.16 ± 0.96 | −1.26 ± 0.96 | 0.54 |

| Femoral neck aBMD | −1.28 ± 0.91 | −1.22 ± 0.90 | −1.35 ± 0.93 | 0.41 |

| Whole body BMC | −0.65 ± 0.89 | −0.63 ± 0.95 | −0.68 ± 0.83 | 0.74 |

| Leg lean mass | −1.01 ± 0.97 | −0.94 ± 0.96 | −1.08 ± 0.98 | 0.40 |

| Whole body fat mass | 0.29 ± 1.02 | 0.37 ± 1.01 | 0.22 ± 1.03 | 0.40 |

| Tibia pQCT Z-s cores | ||||

| Trabecular vBMD | −1.74 ± 0.73 | −1.66 ± 0.70 | −1.83 ± 0.76 | 0.17 |

| Cortical vBMD | −0.45 ± 1.26 | −0.48 ± 1.17 | −0.43 ± 1.36 | 0.81 |

| Cortical area | −1.43 ± 1.12 | −1.40 ± 1.17 | −1.46 ± 1.07 | 0.76 |

| Periosteal circumference | −0.77 ± 0.90 | −0.78 ± 0.91 | −0.76 ± 0.89 | 0.90 |

| Endosteal circumference | 0.29 ± 1.11 | 0.20 ± 1.14 | 0.38 ± 1.10 | 0.35 |

| Calf muscle area | −0.86 ± 0.95 | −0.81 ± 1.00 | −0.91 ± 0.90 | 0.56 |

| Calf fat area | 0.20 ± 1.08 | 0.28 ± 1.02 | 0.13 ± 1.14 | 0.40 |

| Spine QCT vBMD Z-scores | ||||

| Spine trabecular vBMD | −0.72 ± 1.30 | −0.68 ± 1.36 | −0.76 ± 1.25 | 0.71 |

| Tibia QCT BMD across the Metaphysis | ||||

| Tibia trabecular vBMD, mg/cm3 | 204 ± 34 | 208 ± 36 | 200 ± 32 | 0.17 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, n (%), or median (range)

MVPA: Moderate to vigorous physical activity

PA: Posteroanterior

aBMD: areal bone mineral density

vBMD: volumetric bone mineral density

BMC: bone mineral content

BSAP: bone specific alkaline phosphatase

β-CTX: C-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen

Retention and Adherence in the 12 Month RCT

A total of 60 and 61 participants allocated to active and placebo devices completed the 12 month visit, respectively (88% retention, Figure 1). Baseline age, sex, PCDAI score, and height and BMI Z-scores did not differ between the 121 that finished the 12 month visit and the 17 that did not.

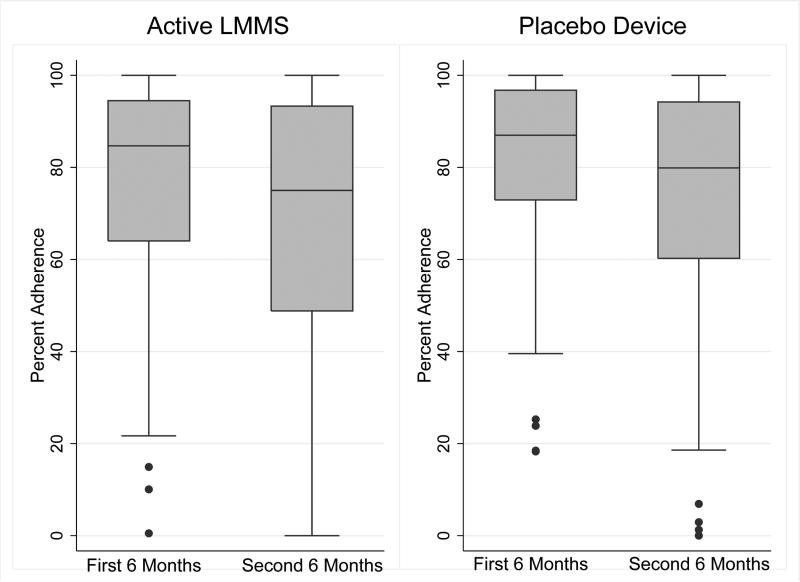

Overall, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) adherence was 77 (58 to 94) and 81 (62 to 96) percent in the active and placebo arms, respectively. Figure 2 illustrates the adherence in the first and second 6-month intervals; adherence was greater in the first 6 months, compared with the second 6 months (p < 0.001) and did not differ between treatment arms. At the completion of the 12 month visit, 51 (85%) of the 60 active participants and 38 (62%) of the 61 placebo participants correctly guessed their treatment assignment.

Figure 2.

Adherence over the 12 Month Trial, according to Treatment Arm

Clinical Parameters over the 12 Month RCT Interval

The clinical course over the 12 month interval in these 121 participants is summarized in Table 2. Height Z-scores, the proportion of participants treated with an anti-TNF-α biologic therapy, and serum 25(OH) vitamin D levels increased significantly. None of the changes in parameters in Table 2 differed significantly between the active and placebo treatment arms. Quarterly measures of physical activity did not change over the study interval and did not differ between treatment arms. The Tanner stage distributions did not differ between treatment arms at the 12 month visit.

Table 2.

Growth and Disease Characteristics over the Study Interval in the 121 Participants that Completed the 12 Month Trial

| Baseline | 12 months | Baseline vs 12 month p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height Z-score* | −0.84 ± 1.03 | −0.69 ± 1.02 | <0.0001 |

| BMI Z-score | −0.22 ± 1.15 | −0.13 ± 1.08 | 0.14 |

| Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index | 10 (3 – 15) | 5 (3 – 15) | 0.08 |

| Inactive (≤ 10), n (%) | 75 (62) | 84 (70) | 0.31 |

| Mild (11-30), n (%) | 40 (33) | 30 (25) | |

| Moderate/Severe (>30), n (%) | 6 (5) | 6 (5) | |

| Laboratory Parameters | |||

| Serum 25(OH) vitamin D, ng/mL | 31.5 ± 10.3 | 34.2 ± 12.4 | 0.005 |

| Serum 25(OH) vitamin D < 20 ng/mL, n (%) | 10 (9) | 7 (6) | 0.16 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 0.91 |

| Hematocrit, % | 37.1 ± 3.7 | 37.9 ± 3.5 | 0.02 |

| Medications | |||

| Glucocorticoids at the visit, n (%) | 14 (12) | 6 (5) | 0.06 |

| Glucocorticoids anytime during the year, n (%) | 20 (17) | -- | |

| Anti-TNF-α biologic at the visit, n (%) | 38 (31) | 53 (44) | <0.001 |

| Anti-TNF-α biologic during the year, n (%) | 55 (46) | -- | |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, n (%), or median (range)

The height Z-score data are limited to those < 18 years of age at the baseline visit in order to assess those with possible growth potential.

Musculoskeletal Outcomes

Table 3 summarizes the analyses of the pQCT, QCT, DXA, bone biomarker, and muscle strength results. Overall, the majority of bone and muscle outcomes improved markedly in the two groups combined (Table 3, column A). Of note, the significant decrease in cortical vBMD is consistent with gains in cortical area and new, less fully mineralized bone, as previously described.(1, 7, 36)

Table 3.

Changes in DXA, pQCT, QCT, Bone Biomarker and Muscle Strength Outcomes in the Intention to Treat Analyses

| A | B | C | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active LMMS (n = 60) | Placebo (n = 61) | P-value for Change in All Participants Combined | Difference in Changes between Groups (95% C.I.)** | P-value for Differences in Changes between Group | |||||

| Baseline | 12 Months | Change | Baseline | 12 Months | Change | ||||

| DXA | |||||||||

| PA spine aBMD Z-score | −1.06 ± 0.97 | −0.88 ± 0.99 | 0.18 ± 0.42 | −1.06 ± 1.13 | −0.97 ± 0.98 | 0.09 ± 0.44 | <0.0005 | 0.05 (−0.07, 0.17) | 0.40 |

| Paired PA lateral spine vBMD Z-score | −0.69 ± 1.19 | −0.54 ± 1.13 | 0.14 ± 0.83 | −0.71 ± 1.45 | −0.57 ± 1.26 | 0.15 ± 0.88 | 0.06 | 0.04 (−0.18, 0.26) | 0.71 |

| Total hip aBMD Z-score | −1.21 ± 0.98 | −0.97 ± 1.02 | 0.24 ± 0.44 | −1.23 ± 0.95 | −0.98 ± 0.89 | 0.26 ± 0.43 | <0.0005 | −0.01 (−0.14, 0.11) | 0.83 |

| Femoral neck aBMD Z-score | −1.26 ± 0.93 | −1.06 ± 0.98 | 0.19 ± 0.45 | −1.34 ± 0.95 | −1.13 ± 0.94 | 0.22 ± 0.45 | <0.0005 | −0.03 (−0.16, 0.10) | 0.66 |

| Whole body BMC Z-score | −0.66 ± 0.99 | −0.46 ± 0.92 | 0.20 ± 0.40 | −0.69 ± 0.81 | −0.51 ± 0.71 | 0.18 ± 0.43 | <0.0005 | 0.02 (−.09, 0.13) | 0.70 |

| Leg lean mass Z-score | −0.97 ± 0.98 | −0.87 ± 1.06 | 0.10 ± 0.68 | −1.00 ± 1.01 | −0.76 ± 1.02 | 0.24 ± 0.56 | <0.0005 | −0.09 (−0.26, 0.08) | 0.29 |

| Tibia pQCT | |||||||||

| Trabecular vBMD Z-score* | −1.69 ± 0.73 | −1.54 ± 0.98 | 0.15 ± 0.55 | −1.87 ± 0.76 | −1.62 ± 0.88 | 0.23 ± 0.70 | <0.0005 | −0.08 (−0.26, 0.10) | 0.38 |

| Cortical vBMD Z-score | −0.10 ± 1.26 | −0.58 ± 1.10 | −0.38 ± 1.01 | −0.14 ± 1.47 | −0.53 ± 1.41 | −0.39 ± 1.07 | <0.0005 | 0.01 (−0.24,0.26) | 0.91 |

| Cortical area Z-score* | −1.44 ± 1.20 | −1.27 ± 1.26 | 0.17 ± 0.58 | −1.45 ± 1.05 | −1.25 ± 0.96 | 0.20 ± 0.59 | < 0.0005 | −0.02 (−0.18, 0.14) | 0.80 |

| Periosteal circ Z-score | −0.84 ± 0.91 | −0.83 ± 1.00 | 0.01 ± 0.26 | −0.75 ± 0.92 | −0.75 ± 0.88 | 0.01 ± 0.27 | 0.76 | 0.00 (−0.07, 0.08) | 0.97 |

| Endosteal circ Z-score | 0.14 ± 1.16 | 0.00 ± 1.11 | −0.13 ± 0.30 | 0.39 ± 1.07 | 0.22 ± 1.09 | −0.17 ± 0.27 | < 0.0005 | 0.02 (−0.06, 0.10) | 0.63 |

| Calf muscle area Z-score | −0.87 ± 1.02 | −0.80 ± 1.04 | 0.07 ± 0.48 | −0.81 ± 0.86 | −0.65 ± 0.89 | 0.15 ± 0.46 | 0.01 | −0.05 (−0.18, 0.08) | 0.42 |

| Spine QCT | |||||||||

| Spine trabecular vBMD Z-score* | −0.78 ± 1.39 | −0.56 ± 1.26 | 0.22 ± 0.59 | −0.74 ± 1.24 | −0.76 ± 1.09 | −0.02 ± 0.67 | 0.09 | 0.24 (0.03, 0.44) | 0.02 |

| Tibia Metaphysis QCT | |||||||||

| Metaphysis Trabecular vBMD, mg/cm3 | 204 ± 36 | 213 ± 40 | 8 ± 21 | 198 ± 31 | 209 ± 34 | 11 ± 16 | <0.0005** | −2 (−9, 5) | 0.53 |

| Bone Biomarkers | |||||||||

| BSAP Z-score | −0.86 ± 1.41 | −0.26 ± 1.28 | 0.60 ± 1.39 | −0.80 ± 1.30 | −0.20 ± 1.56 | 0.44 ± 1.71 | <0.001 | 0.00 (−0.32, 0.32) | 0.98 |

| β-CTX Z-score | 0.19 ± 1.03 | 0.31 ± 0.99 | 0.11 ± 1.15 | 0.26 ± 1.02 | 0.26 ± 1.36 | −0.12 ± 1.30 | 0.99 | 0.22 (−0.12, 0.56) | 0.20 |

| Dynamometer | |||||||||

| Calf muscle strength Z-score | −0.40 ± 0.91 | −0.25 ± 0.92 | 0.13 ± 0.68 | −0.46 ± 0.94 | −0.41 ± 0.87 | 0.09 ± 0.75 | 0.11 | 0.08 (−0.10, 0.27) | 0.38 |

Primary outcomes

Adjusted for baseline value

PA: posterioanterior

aBMD: areal BMD

vBMD: volumetric BMD

Circ: circumference

**Note, the significant increase in tibia QCT metaphysis trabecular vBMD represents growth and development, at least in part, as these were not converted to Z-scores.

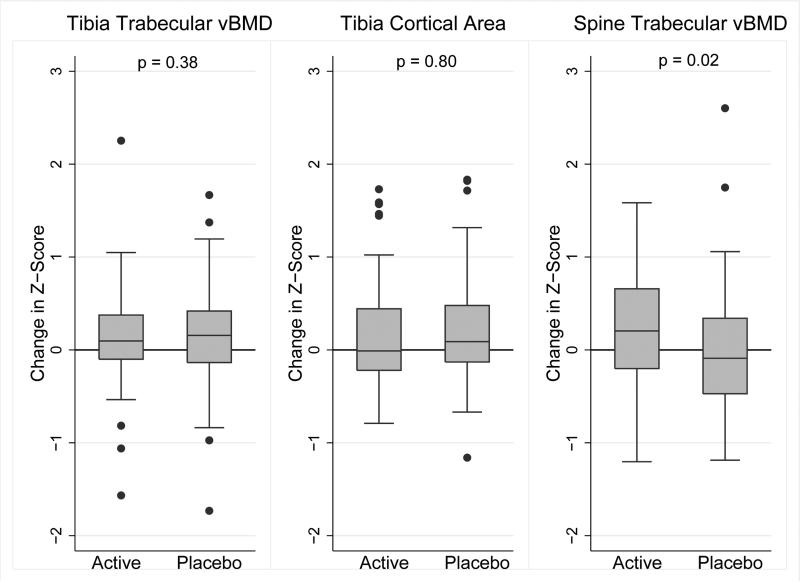

Using an intention-to-treat analysis adjusted for the baseline value, LMMS resulted in no significant differences in changes in Z-scores for any of the pQCT, DXA or bone biomarker outcomes. Columns B and C (Table 3) summarize the group differences in change and the corresponding p-values. A statistically significant treatment effect was observed for the spine QCT trabecular vBMD Z-score: the mean change was +0.22 in the active arm and −0.02 in the placebo arm for a difference in change of 0.24 (p = 0.02). The results were unchanged using multiple imputation. The analysis of changes in tibia QCT measures of vBMD across the trabecular metaphysis did not demonstrate any treatment effect; these results could not be examined as a Z-score given the lack of reference data. There was no evidence of a treatment interaction with sex, baseline BMI Z-score, leg lean mass Z-scores, Tanner stage, PCDAI Score, or with concurrent glucocorticoid or biologic therapy for any of the outcomes in Table 3. The results for the three primary outcomes are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Changes in the Primary Outcomes over 12 Months in the Active and Placebo Arms

As-treated analyses for each outcome in Table 3 were repeated using the adherence data. The LMMS effect (differences in changes in Z-scores) for the spine QCT trabecular vBMD Z-score among those with > 25%, > 50% and > 75% adherence were: 0.23 (95% CI 0.02, 0.44, p = 0.03), 0.38 (0.17, 0.58, p < 0.0005), and 0.41 (0.16, 0.66, p < 0.0005), respectively. Within the active arm, each 10% greater adherence was associated with a 0.06 (95% CI 0.01, 1.17, p = 0.03) greater increase in spine QCT trabecular vBMD Z-score over the study interval. This association was absent (p = 0.36) within the placebo arm. These as-treated analyses were repeated using the vBMD (mg/cm3) results (as opposed to Z-scores). The LMMS effect (differences in changes in vBMD) for the spine QCT trabecular vBMD among those with > 50% adherence was 6.5 mg/cm3 (95% CI 0.4, 12.5, p = 0.04). Within the active arm, each 10% greater adherence was associated with a 1.4 mg/cm3 (95% CI 0.03, 2.7, p = 0.04) greater increase in spine QCT trabecular vBMD over the study interval. This association was absent (p = 0.81) within the placebo arm. The as-treated analyses confirmed non-significant results for all other outcomes in Table 3.

Adverse Events

The adverse events over the 12 month RCT are summarized in Table 4. There were a total of 28 and 27 hospitalizations in participants in the active and placebo arms, respectively. The majority were for CD flares. The proportion reporting gastrointestinal symptoms at each visit was greater among participants randomized to the active device (p = 0.001 by Fisher's exact test). One participant in the placebo arm attributed foot pain to the device and withdrew from the study.

Table 4.

Adverse Events During the 12 Month Trial

| Active N = 69 | Placebo N = 69 | |

|---|---|---|

| Hospitalizations | 28 | 27 |

| Crohn Disease flare | 20 in 13 participants | 25 in 15 participants |

| Migraine | 4 in 1 participant | 0 |

| Myositis | 1 | 0 |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 0 |

| Viral illness | 0 | 1 |

| Appendectomy | 1 | 0 |

| Pyelonephritis | 0 | 1 |

| Cellulitis | 1 | 0 |

| Reported Symptoms at Study Visits | 21 | 18 |

| Abdominal pain | 5 | 0 |

| Stool changes | 5 | 0 |

| Nausea, motion sickness or dizziness | 2 | 2 |

| Vision change | 0 | 0 |

| Anxiety | 0 | 1 |

| Back pain | 3 | 2 |

| Lower extremity pain | 3 | 6 |

| Other joint pain (not lower extremity) | 0 | 3 |

| Headache | 2 | 4 |

| Urinary urgency | 1 | 0 |

Open Label Extension from 12 to 24 Months

Of the 60 participants in the active arm that completed the 12 month trial, 55 returned for the 24 month visit after a year off therapy (Figure 1). Among the 61 participants in the placebo arm that completed the 12 month trial, 51 accepted an active LMMS device for the open label extension and 10 declined. Of these 61, 50 returned at 24 months, including 43 of those that took home an active device. Table 5 summarizes the clinical course in the 105 participants that completed the 24 month visit. Height Z-scores continued to improve. The Tanner stage distributions and height Z-scores did not differ between the two randomization groups at the time of the 24 month visit. None of the DXA, pQCT, or QCT Z-scores changed significantly during the 12 month open label extension (data not shown). In the 55 participants that were randomized to the active device during the initial 12 month trial and were then followed for a year off therapy, the QCT spine vBMD decreased from −0.56 ± 1.29 to −0.70 ± 1.23 (p = 0.02). In the 50 participants that were randomized to the placebo device during the initial 12 month trial and completed the 24 month visit, the QCT spine vBMD Z-scores did not change (from −0.78 ± 1.12 to −0.76 ± 1.03). However, only 43 had an active device in the home during this interval and the median (IQR) adherence was only 5 (1 to 48) percent.

Table 5.

Growth and Disease Characteristics at 12 and 24 Months among the 105 Participants that Completed the Open Label Extension

| 12 months | 24 months | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height Z-score* | −0.61 ± 0.97 | −0.51 ± 0.98 | < 0.001 |

| BMI Z-score | −0.13 ± 1.06 | −0.19 ± 1.00 | 0.27 |

| Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index | 5 (3 - 15) | 5 (0 - 13) | 0.05 |

| Inactive (≤ 10), n (%) | 72 (69) | 74 (72) | 0.28 |

| Mild (11-30), n (%) | 26 (25) | 29 (28) | |

| Moderate/Severe (>30), n (%) | 6 (6) | 1 (1) | |

| Laboratory Parameters | |||

| Serum 25(OH) vitamin D, ng/mL | 34.2 ± 11.8 | 37.7 ± 15.6 | 0.01 |

| Serum 25(OH) vitamin D < 20 ng/mL, n (%) | 7 (7) | 8 (8) | 0.71 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 0.89 |

| Hematocrit, % | 37.9 ± 3.5 | 38.9 ± 3.8 | < 0.001 |

| Medications | |||

| Systemic steroids at the visit, n (%) | 6 (6) | 5 (5) | 0.71 |

| Systemic steroids anytime during interval, n (%) | 14 (13) | -- | |

| Biologics at the visit, n (%) | 45 (43) | 48 (46) | 0.32 |

| Biologics anytime during the interval, n (%) | 50 (48) | -- | |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, n (%), or median (range)

Height Z-score data limited to those < 18 years of age at the 12 month visit.

DISCUSSION

This 12 month RCT of 10 minutes of daily LMMS did not demonstrate beneficial effects on tibia trabecular vBMD, tibia cortical structure or DXA outcomes in the spine, proximal femur and whole body in children and adolescents with CD and low trabecular vBMD treated with calcium and vitamin D supplementation. In contrast, LMMS was associated with significant improvements in QCT measures of spine trabecular vBMD in the intention to treat analyses and the effect size was greater when limited to those with greater adherence. In addition, there was a significant dose-response relationship with adherence among those randomized to the active device. Given reports of vertebral compression fractures in children with CD and other chronic inflammatory conditions, this is a clinically relevant finding.(3, 5)

Prior RCTs of daily LMMS in children and adolescents yielded mixed results. A study of 149 females with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and low femoral neck aBMD (Z-score < −1) demonstrated that 20 minutes of LMMS prescribed five days per week for 12 months, compared with observation alone, resulted in greater increases in DXA femoral neck aBMD (on the dominant side only) and marginally greater increases in DXA spine BMC (p = 0.05); however, there were no significant effects on high resolution-pQCT measures of trabecular microarchitecture or cortical area in the dominant or nondominant tibia.(18) A study in 48 adolescents and young women (ages 15 to 20 years) with low QCT spine trabecular vBMD (approximately 1 SD below peak vBMD values) and a history of a fracture demonstrated an effect of LMMS prescribed 10 minutes daily for 12 months on QCT measures of spine trabecular vBMD (p = 0.06 in the intention-to-treat analysis) and femur cortical bone area, compared with observation alone. Mean adherence in the LMMS arm was only 40% and the spine effects were statistically significant when those with < 20% adherence were excluded. Finally, a study in 31 children with cerebral palsy examined the effect of 10 minutes of LMMS prescribed daily for 6 months, compared with the subsequent 6 month interval with standing alone: LMMS was associated with significantly greater increases in QCT tibia cortical area but not spine trabecular vBMD.(17) Of note, none of these studies used a placebo device. Furthermore, the LMMS signal may not have been effectively transmitted to the spine in the children with neuromuscular disorders due to contractures and an inability to stand upright.(16, 17)

There are multiple potential explanations for the lack of consistent effects across skeletal sites in our study. First, DXA spine aBMD includes substantial cortical bone, potentially concealing treatment effects in the trabecular compartment. More than 50% of the BMC in the PA projection is contained within the cortical spinous processes in children and adolescents.(45) Accordingly, PA DXA spine aBMD correlates poorly with QCT trabecular vBMD (R = 0.66).(46) Furthermore, trabecular bone accounts for less than half of the BMC within the vertebral body.(47) These relations may account for our inconsistent findings in the spine by DXA and QCT. Second, the inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of CD.(48) Recent preclinical studies suggest that TNF-α induces osteocyte apoptosis.(49) That is, the underlying inflammatory process in CD may promote the death of the mechanosensors that contribute to the skeletal response to LMMS. In addition, LMMS may have direct effects on mesenchymal stem cells through mechanical coupling between the cytoskeleton and nucleus;(50) the impact of inflammation on this process is not known. Third, bone density and structure improved significantly over the 12 month study period in both treatment arms, possibly obscuring an LMMS effect. While the calcium and vitamin D supplements may have contributed to the improvements in skeletal outcomes, the increase in height Z-scores and muscle mass suggest more global improvements in health. It is possible that participation in the RCT was associated with greater overall adherence to concurrent CD therapies. It is noteworthy that bone and muscle outcomes did not improve further during the off label extension when study participants were not monitored for adherence by the study team in real time. An alternative interpretation is that the changes over the first year represented regression to the mean in a cohort recruited with lower trabecular vBMD Z-scores. Fourth, a substantial proportion of participants were treated with intravenous anti-TNF-α biologics during the study interval. Given our recent report of rapid increases in bone density, bone structure, muscle mass and growth following initiation of anti-TNF-α therapy,(1) this potent therapy may also have obscured LMMS effects. Fifth, LMMS is a subtle intervention, and greater treatment frequency and/or duration may be needed to counteract the adverse skeletal effects of this chronic disease.

The study had many important and unique strengths. This is the first study of LMMS in a chronic inflammatory condition in children or adults. The use of an electronic adherence monitor provided objective and complete measures of adherence, and the ongoing feed-back and incentives achieved high levels of adherence in a population with a complex chronic disease. The treatment arms were well balanced at baseline, and the disease and treatment characteristics did not differ between treatment arms over the duration. Further, accelerometers were used to ensure that physical activity did not differ between groups over the trial duration. The provision of calcium and vitamin D supplements ensured adequate nutritional substrate in the context of anabolic bone stimuli. Finally, the novel use of QCT scans of the entire tibia provided a comprehensive measure of trabecular vBMD across the entire metaphysis, obviating concerns that a single 2.3 mm pQCT slice would not capture the same bone region in a growing child over time.(24)

The study included an open label extension as an incentive for enrollment, and adherence was not monitored in real time in the participants with an active LMMS device in the home during the extension. The poor adherence (median of 5%) may reflect cessation of monitoring and financial incentives, and should not be generalized to other clinical settings. The significant decrease in QCT spine trabecular vBMD Z-scores during the second year among the participants originally treated with an active device suggests treatment gains may not be sustained.

The study had potential limitations. First, we did not have local reference data for the spine QCT trabecular vBMD results and relied on published data. However, any inaccuracies in the Z-score would affect each treatment arm the same, and sensitivity analyses using vBMD (mg/cm3, as opposed to Z-scores) confirmed our findings. Second, 12% of participants did not complete the 12 month visit; however, retention was comparable in both arms and comparison of participant characteristics among those that did vs. did not complete the study did not suggest bias. Third, the large number of study outcomes increases the potential for a type 1 error. The pre-specified analyses did not include adjustments for multiple comparisons given that the numerous outcomes are not independent. Rather, we examined for consistency of findings. Accordingly, the spine QCT findings should be interpreted with caution in the absence of a significant effect detected for PA or paired PA-lateral spine DXA BMD. Last, the results are likely generalizable to childhood chronic inflammatory diseases but may not be generalizable to clinical care in the absence of incentives and monitoring.

In conclusion, this 12 month RCT demonstrated lack of an LMMS effect on cortical bone structure and an inconsistent effect on axial and appendicular trabecular vBMD in children and adolescents with CD. Pre-clinical studies are needed to determine if systemic inflammation hampers the osteocyte response to LMMS. The strong dose response observed for vertebral trabecular vBMD may inform future studies of LMMS interventions in chronic inflammatory disease.

Role of the Funding Source

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) funding this study. Officer. The investigators retained control of all aspects of the study design, conduct and reporting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for Laura K. Bachrach's service and helpful suggestions as our Safety Officer throughout the duration of the study.

AUTHORS’ ROLES

Study design: MBL, JS, RNB, KB, BSZ, SM, CT. Study conduct and data collection: MBL, JS, RNB, KB, KH, BSZ, SM, KHW, RH, CT. Data analysis and interpretation: MBL, JS, JL, KB, KH, BSZ, DL, JR, CT. Drafting manuscript: MBL, JL. Revising manuscript content and approving final version: all. MBL takes responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

Funding Sources: NIH R01-DK073946, K24-DK076808, K23-DK079037, T32-DK007740, and UL1-RR-024134 and UL1-TR-000003

Footnotes

Disclosure: CTR is a founder of Marodyne, Inc., and has several patents on the use of mechanical signals to regulate bone activity. No other authors have any conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Data: none

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00364130

REFERENCES

- 1.Griffin LM, Thayu M, Baldassano RN, DeBoer MD, Zemel BS, Denburg MR, et al. Improvements in Bone Density and Structure during Anti-TNF-alpha Therapy in Pediatric Crohn's Disease. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2015;100(7):2630–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee DY, Wetzsteon RJ, Zemel BS, Shults J, Organ JM, Foster BJ, et al. Muscle torque relative to cross-sectional area and the functional muscle-bone unit in children and adolescents with chronic disease. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2015;30(3):575–83. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Semeao EJ, Stallings VA, Peck SN, Piccoli DA. Vertebral compression fractures in pediatric patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(5):1710–3. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burnham JM, Shults J, Weinstein R, Lewis JD, Leonard MB. Childhood onset arthritis is associated with an increased risk of fracture: a population based study using the General Practice Research Database. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2006;65(8):1074–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.048835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeBlanc CM, Ma J, Taljaard M, Roth J, Scuccimarri R, Miettunen P, et al. Incident Vertebral Fractures and Risk Factors in the First Three Years Following Glucocorticoid Initiation Among Pediatric Patients With Rheumatic Disorders. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2015 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubner SE, Shults J, Baldassano RN, Zemel BS, Thayu M, Burnham JM, et al. Longitudinal assessment of bone density and structure in an incident cohort of children with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(1):123–30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsampalieros A, Lam CK, Spencer JC, Thayu M, Shults J, Zemel BS, et al. Long-term inflammation and glucocorticoid therapy impair skeletal modeling during growth in childhood Crohn disease. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98(8):3438–45. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ducher G, Bass SL, Saxon L, Daly RM. Effects of repetitive loading on the growth-induced changes in bone mass and cortical bone geometry: a 12-month study in pre/peri- and postmenarcheal tennis players. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2011;26(6):1321–9. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kontulainen S, Sievanen H, Kannus P, Pasanen M, Vuori I. Effect of long-term impact-loading on mass, size, and estimated strength of humerus and radius of female racquet-sports players: a peripheral quantitative computed tomography study between young and old starters and controls. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2002;17(12):2281–9. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.12.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan ME, Uzer G, Rubin CT. The potential benefits and inherent risks of vibration as a non- drug therapy for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Current osteoporosis reports. 2013;11(1):36–44. doi: 10.1007/s11914-012-0132-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie L, Jacobson JM, Choi ES, Busa B, Donahue LR, Miller LM, et al. Low-level mechanical vibrations can influence bone resorption and bone formation in the growing skeleton. Bone. 2006;39(5):1059–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie L, Rubin C, Judex S. Enhancement of the adolescent murine musculoskeletal system using low-level mechanical vibrations. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md : 1985) 2008;104(4):1056–62. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00764.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanleene M, Shefelbine SJ. Therapeutic impact of low amplitude high frequency whole body vibrations on the osteogenesis imperfecta mouse bone. Bone. 2013;53(2):507–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Oliveira ML, Bergamaschi CT, Silva OL, Nonaka KO, Wang CC, Carvalho AB, et al. Mechanical vibration preserves bone structure in rats treated with glucocorticoids. Bone. 2010;46(6):1516–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilsanz V, Wren TA, Sanchez M, Dorey F, Judex S, Rubin C. Low-level, high-frequency mechanical signals enhance musculoskeletal development of young women with low BMD. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2006;21(9):1464–74. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward K, Alsop C, Caulton J, Rubin C, Adams J, Mughal Z. Low magnitude mechanical loading is osteogenic in children with disabling conditions. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2004;19(3):360–9. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wren TA, Lee DC, Hara R, Rethlefsen SA, Kay RM, Dorey FJ, et al. Effect of high-frequency, low-magnitude vibration on bone and muscle in children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30(7):732–8. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181efbabc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam TP, Ng BK, Cheung LW, Lee KM, Qin L, Cheng JC. Effect of whole body vibration (WBV) therapy on bone density and bone quality in osteopenic girls with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a randomized, controlled trial. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2013;24(5):1623–36. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leonard MB, Elmi A, Mostoufi-Moab S, Shults J, Burnham JM, Thayu M, et al. Effects of sex, race, and puberty on cortical bone and the functional muscle bone unit in children, adolescents, and young adults. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2010;95(4):1681–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Standards Organization: Evaluation of Human Exposure to Whole-Body Vibration. Geneva, Switzerland: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyams JS, Ferry GD, Mandel FS, Gryboski JD, Kibort PM, Kirschner BS, et al. Development and validation of a pediatric Crohn's disease activity index. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 1991;12(4):439–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris NM, Udry JR. Validation of a self-administered instrument to assess stage of adolescent development. Journal of youth and adolescence. 1980;9(3):271–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02088471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams JE, Engelke K, Zemel BS, Ward KA. Quantitative computer tomography in children and adolescents: the 2013 ISCD Pediatric Official Positions. Journal of clinical densitometry : the official journal of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry. 2014;17(2):258–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee DC, Gilsanz V, Wren TA. Limitations of peripheral quantitative computed tomography metaphyseal bone density measurements. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2007;92(11):4248–53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsampalieros A, Berkenstock MK, Zemel BS, Griffin L, Shults J, Burnham JM, et al. Changes in trabecular bone density in incident pediatric Crohn's disease: a comparison of imaging methods. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2014;25(7):1875–83. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2701-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wetzsteon RJ, Zemel BS, Shults J, Howard KM, Kibe LW, Leonard MB. Mechanical loads and cortical bone geometry in healthy children and young adults. Bone. 2011;48(5):1103–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowlands AV, Thomas PW, Eston RG, Topping R. Validation of the RT3 triaxial accelerometer for the assessment of physical activity. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2004;36(3):518–24. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000117158.14542.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Guo S, Wei R, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):45–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuchman S, Thayu M, Shults J, Zemel BS, Burnham JM, Leonard MB. Interpretation of biomarkers of bone metabolism in children: impact of growth velocity and body size in healthy children and chronic disease. The Journal of pediatrics. 2008;153(4):484–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffin LM, Kalkwarf HJ, Zemel BS, Shults J, Wetzsteon RJ, Strife CF, et al. Assessment of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry measures of bone health in pediatric chronic kidney disease. Pediatric nephrology. 2012;27(7):1139–48. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2116-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole TJ. The LMS method for constructing normalized growth standards. European journal of clinical nutrition. 1990;44(1):45–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flegal KM, Cole TJ. Construction of LMS parameters for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts. National health statistics reports. 2013(63):1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zemel BS, Leonard MB, Kelly A, Lappe JM, Gilsanz V, Oberfield S, et al. Height adjustment in assessing dual energy x-ray absorptiometry measurements of bone mass and density in children. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2010;95(3):1265–73. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Avitabile CM, Leonard MB, Zemel BS, Brodsky JL, Lee D, Dodds K, et al. Lean mass deficits, vitamin D status and exercise capacity in children and young adults after Fontan palliation. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2014;100(21):1702–7. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mostoufi-Moab S, Magland J, Isaacoff EJ, Sun W, Rajapakse CS, Zemel B, et al. Adverse Fat Depots and Marrow Adiposity Are Associated With Skeletal Deficits and Insulin Resistance in Long-Term Survivors of Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2015;30(9):1657–66. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mostoufi-Moab S, Brodsky J, Isaacoff EJ, Tsampalieros A, Ginsberg JP, Zemel B, et al. Longitudinal assessment of bone density and structure in childhood survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial radiation. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2012;97(10):3584–92. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilsanz V, Perez FJ, Campbell PP, Dorey FJ, Lee DC, Wren TA. Quantitative CT reference values for vertebral trabecular bone density in children and young adults. Radiology. 2009;250(1):222–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2493080206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hangartner TN, Gilsanz V. Evaluation of cortical bone by computed tomography. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 1996;11(10):1518–25. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashe MC, Khan KM, Kontulainen SA, Guy P, Liu D, Beck TJ, et al. Accuracy of pQCT for evaluating the aged human radius: an ashing, histomorphometry and failure load investigation. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2006;17(8):1241–51. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kontulainen SA, Johnston JD, Liu D, Leung C, Oxland TR, McKay HA. Strength indices from pQCT imaging predict up to 85% of variance in bone failure properties at tibial epiphysis and diaphysis. Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions. 2008;8(4):401–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu D, Manske SL, Kontulainen SA, Tang C, Guy P, Oxland TR, et al. Tibial geometry is associated with failure load ex vivo: a MRI, pQCT and DXA study. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2007;18(7):991–7. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shults J, Ratcliffe SJ, Leonard MB. Improved generalized estimating equations analysis vis xtqls for quasi-least squared in Stata. The Stata Journal. 2007;7(2):147–66. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shults J, Hilbe JM. Quasi-Least Squares Regression. Chapman and Hill; London, UK: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diggle P, Heagerty P, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leonard MB, Shults J, Zemel BS. DXA estimates of vertebral volumetric bone mineral density in children: potential advantages of paired posteroanterior and lateral scans. Journal of clinical densitometry : the official journal of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry. 2006;9(3):265–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee DC, Campbell PP, Gilsanz V, Wren TA. Contribution of the vertebral posterior elements in anterior-posterior DXA spine scans in young subjects. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2009;24(8):1398–403. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nottestad SY, Baumel JJ, Kimmel DB, Recker RR, Heaney RP. The proportion of trabecular bone in human vertebrae. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 1987;2(3):221–9. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Mattos BR, Garcia MP, Nogueira JB, Paiatto LN, Albuquerque CG, Souza CL, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Overview of Immune Mechanisms and Biological Treatments. Mediators of inflammation. 2015;2015:493012. doi: 10.1155/2015/493012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bonewald LF. The amazing osteocyte. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2011;26(2):229–38. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uzer G, Thompson WR, Sen B, Xie Z, Yen SS, Miller S, et al. Cell Mechanosensitivity to Extremely Low-Magnitude Signals Is Enabled by a LINCed Nucleus. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2015;33(6):2063–76. doi: 10.1002/stem.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]