Abstract

This study investigates differences in μ-opioid receptor mediated neurotransmission in healthy controls and overnight-abstinent smokers, and potential effects of the OPRM1 A118G genotype. It also examines the effects of smoking denicotinized (DN) and average nicotine (N) cigarettes on the μ-opioid system. Positron emission tomography with 11C-carfentanil was used to determine regional brain μ-opioid receptor (MOR) availability (non-displaceable binding potential, BPND) in a sample of 19 male smokers and 22 nonsmoking control subjects.

Nonsmokers showed greater MOR BPND than overnight abstinent smokers in the basal ganglia and thalamus bilaterally. BPND in the basal ganglia was negatively correlated with baseline craving levels and Fagerström scores. Interactions between group and genotype were seen in the nucleus accumbens bilaterally and the amygdala, with G-allele carriers demonstrating lower BPND in these regions, but only among smokers.

After smoking the DN cigarette, smokers showed evidence of MOR activation in the thalamus and nucleus accumbens. No additional activation was observed after the N cigarette, with a mean effect of increases in MOR BPND (i.e., deactivation) with respect to the DN cigarette effects in the thalamus and left amygdala. Changes in MOR BPND were related to both Fagerström scores and changes in craving.

This study showed that overnight-abstinent smokers have lower concentrations of available MORs than controls, an effect that was related to both craving and the severity of addiction. It also suggests that nicotine non-specific elements of the smoking experience have an important role in regulating MOR-mediated neurotransmission, modulating withdrawal-induced craving ratings.

Keywords: smoking, PET, [11C]-Carfentanil, OPRM1, A118G

1. INTRODUCTION

With over one billion smokers worldwide, nicotine dependence is a major health concern. There are more than 5 million deaths associated with tobacco each year, and tobacco smoking is the most prevalent cause of “preventable disease and death” in the United States (Graul and Prous, 2005). There are substantial lines of evidence pointing to a strong link between nicotine use and endogenous μ-opioid mechanisms, which may mediate some of nicotine’s addictive properties and distress during withdrawal (for review see Pomerleau, 1998).

Animal and cell culture studies suggest that acute nicotine induces endogenous opioid release (Boyadjieva and Sarkar, 1997; Davenport et al, 1990). However, attempts to translate these initial findings into human studies have led to inconsistent results. Studies examining changes in MOR availability (binding potential, BP) after smoking denicotinized (DN) versus average nicotine (N) cigarettes with positron emission tomography (PET), an indirect measure of changes in neurotransmitter release and μ-opioid receptor activation, have found both reductions in BP (suggesting activation of neurotransmission) and increases (deactivation) in different regions of the brain (Domino et al, 2015; Scott et al, 2006). Alternatively, some studies have not found any significant differences in MOR binding after smoking N versus DN cigarettes (Kuwabara et al, 2014; Ray et al, 2011). Measures at baseline have also shown either lower MOR BP in smokers compared to nonsmoking controls (Scott et al, 2006), or no significant differences between groups (Kuwabara et al, 2014). The μ-opioid system is known to respond to positive expectancies, including the so-called placebo effect (Pecina et al, 2015a; Scott et al, 2008; Zubieta et al, 2005), which may impact the effects of both DN and N. This effect could be particularly prominent in studies conducted after nicotine abstinence, when craving and positive expectancies are highest. This was initially suggested in a small pilot study (Scott et al., 2006), and could potentially contribute to inconsistencies in results across study designs.

To explore this possibility, the current study examined MOR non-displaceable BP (BPND) (Innis et al, 2007) at baseline, preceding and following DN and N cigarettes, and again during DN and N smoking using a single blind design. In this analysis, effects of DN and N cigarette smoking on subsequent BPND values were further controlled by their corresponding baseline values to provide a corrected measure of μ-opioid system activation (changes in BPND) after DN and N smoking. Smokers were studied after verified overnight abstinence when craving for cigarettes would be high. The effects of a common functional polymorphism of the MOR (OPRM1) gene, the A118G polymorphism, were also evaluated in these analyses. This substitution of an aspartic acid for asparagine in the MOR gene has been associated with lower levels of MOR mRNA and protein (Zhang et al, 2005; Kroslak et al, 2007). There has been a great deal of interest in whether this polymorphism is associated with aspects of addiction, but studies have given inconsistent results (Arias et al, 2006). The A118G polymorphism has been shown in previous PET studies to reduce both baseline MOR BPND (Pecina et al, 2015b; Ray et al, 2011; Weerts et al, 2013) and the activation of the μ-opioid system during positive expectations (Pecina et al, 2015b).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Participants and study design

Twenty-four smokers and 22 healthy nonsmokers between the ages of 20 and 35 were recruited by advertisement for this study. All participants were male and right-handed, not on any medication, and had no history or current signs of psychiatric or physical illnesses. Participants were excluded if they used any drugs of abuse besides tobacco smoking. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subject Research and the Radioactive Drug Research Committee at the University of Michigan.

Five individuals from the experimental group were excluded from the analyses. Three had missing elements of MRI or PET data, one subject was discovered to be a nonsmoker, and one tested positive for opioids at the time of his PET scan. The final sample was 19 male smokers between the ages of 20 and 35 (mean ± SD: 25.3±4.4 years) and 22 nonsmokers (mean ± SD: 24.2±3.7 years). Participants smoked between 6 and 30 cigarettes a day (mean ± SD: 18.4±5.6), and had Fagerström Scale of Nicotine Dependence scores ranging from 2 to 8.3 (mean ± SD: 5.5±1.9) with 10 being most dependent (Heatherton et al, 1991).

Smokers were instructed to cease smoking the night before the 8:30 AM scans, resulting in 8–12 hrs of abstinence. Compliance was tested using a carbon monoxide (CO) detector (Vitalograph Breath CO Model BC1349, Vitalograph Inc., Lenexa, KS) with a requirement of CO levels < 10 parts per million (p.p.m.) prior to scanning (Domino and Ni, 2002).

In the overall protocol, PET scanning was conducted using the radiotracers 11C-carfentanil (11C-CFN) and 11C-raclopride (11C-RCL) targeting μ-opioid and dopaminergic D2/D3 receptors, respectively. Only the 11C-CFN data is reported here. Smokers participated in the trials on two separate days, with two 90 min PET scans each day. For the first half of each scan the participants were simply instructed to lie still, providing a baseline measure. Between 43 and 53 min after tracer administration, smokers were directed to smoke either two DN cigarettes (0.08 mg nicotine/cigarette, 9.1 mg tar/cigarette) or two N cigarettes (1.01 mg nicotine/cigarette, 9.5 mg tar/cigarette) through a one-way airflow system. Smokers received the N cigarettes second in order to prevent the effects of the nicotine from carrying over into the DN condition. Each day, participants received one scan using the tracer 11C-CFN and one using the tracer 11C-RCL, separated by approximately two hours. On the second day the participants came in, the tracer order was switched. Whether subjects received 11C-CFN or 11C-RCL first on their first scanning day was counterbalanced to control for any possible effects the earlier tracer or MOR turnover might have on the later scan. However, tracers were administered at subpharmacological doses and therefore should not have had any pharmacological effects, occupying less than 1% of available receptors (Zubieta et al, 2003). The half-life of carbon-11 is 20 minutes, resulting in complete decay between tracer administrations. The data from the 11C-RCL scans has been previously reported (Domino et al, 2012; Domino et al, 2013), as has a different analysis of the 11C-CFN data (Domino et al, 2015).

Prior to scanning, smokers were asked to rate a 1–10 visual analog scale (VAS) for “craving”. They repeated this at 30 and 60 min into each of the scans (once before smoking and once after smoking). At the 30 and 60 min time points participants also completed the Positive and Negative Affectivity Schedule (PANAS; Watson and Clark, 1999), Profile of Mood States (POMS; McNair et al, 1971), and Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger et al, 1983).

Six of the healthy controls were asked to smoke a sham cigarette (unlit cardboard cylinder) in place of either the DN or N cigarette. The remaining 16 controls simply underwent one 90 min baseline 11C-CFN scan in which they were asked to lie in the scanner with no intervention.

2.2. Scanning protocol and data acquisition

Participants were placed in a Siemens HR+ scanner and data were collected as previously described (Domino et al, 2012; Scott et al, 2006). Briefly, scans were acquired in three-dimensional mode (reconstructed FWHM resolution ~5.5 mm in-plane and 5.0 mm axially, with septa retracted and scatter correction). Images were reconstructed using iterative algorithms (brain mode; FORE/OSEM four iterations, 16 subsets; no smoothing) into a 128×128 pixel matrix in a 28.8 cm diameter field of view. Attenuation correction was done using a 6 min transmission scan (68Ge source) obtained before the radiotracer was injected. Image data was transformed into two sets of parametric maps: a tracer transport measure (K1) and a receptor related measure (BPND) using a modified Logan graphical analysis (Logan et al, 1996) with the occipital cortex as a reference region.

A light forehead restraint was used on each participant to reduce movement, and two intravenous (antecubital) lines were placed. 11C-CFN was synthesized at high specific activity through the reaction of 11C-methyliodide and a non-methyl precursor (Jewett, 2001). The tracer was administered through one of the intravenous lines, beginning with a bolus containing half of the tracer. The other 50% was administered continuously during the scan.

A high-resolution anatomical magnetic resonance image was obtained for each participant using a 3 Tesla scanner (Signa, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI). The acquisition sequence used was an axial SPGR IRpPrep MR (TE = 5.5, TR = 14, TI = 300, flip angle = 20°, NEX = 1, 124 contiguous images, 1.5mm thickness), followed by axial T2 and proton density images (TE = 20 and 100, respectively; TR = 4000, NEX = 1, 62 contiguous images, 3mm thickness).

2.3. Bloods/Genotyping/Plasma Nicotine

Before the first scan, 10 ml of venous blood was drawn from each participant. Blood was processed by the Michigan Center for Translational Pathology laboratory biorepository and Michigan Sequencing Core for analysis and subsequently reconfirmed (Domino et al., 2012). Each participant’s genotype at the OPRM1 A118G polymorphism was determined. Participants were divided into two groups based on whether they carried at least one rare G allele (G*) or whether they were homozygous for the A allele. Nicotine plasma levels were also determined by drawing blood samples just before smoking (min 43) and at five other time points after smoking initiation (49, 59, 65, 75, and 95 min after tracer administration). Blood samples were analyzed by MEDTOX Laboratories, Inc. (St. Paul, MN).

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1. Image preprocessing

PET data consisted of two early BPND values acquired at baseline (10–40 min post-tracer administration, one of them after overnight abstinence and the second after an initial DN smoking session), and two late session BPND values (45–90 min post-tracer administration) acquired during DN and N smoking. Each participant’s PET images were coregistered to their own magnetic resonance image using Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts) and SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Center for Neuroimaging, London, United Kingdom) software, and then were linear and non-linear warped using VBM8 Toolbox (Christian Gaser, University of Jena, Department of Psychiatry, Jena, Germany) within SPM8 to match the Montreal Neurological Institute stereotactic atlas orientation. Coregistration and warping were checked visually for each participant, and a 3-D Gaussian filter (FWHM 6 mm) was applied to each scan. Voxel-by-voxel whole-brain analyses were performed, and significance thresholds estimated using image smoothness, the Euler characteristic, and the number of voxels in the gray matter (Worsley et al, 1992). Further analyses were performed on extracted data using SPSS Statistics v. 20 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). BPND values were examined to investigate differences between baseline values, changes in BPND as a result of DN and N smoking, and the effect of the OPRM1 A118G polymorphism on these measures.

2.4.2. Craving, Fagerström scores, and plasma nicotine levels in smokers

Paired t-tests in SPSS were used to compare VAS craving ratings at 30 min and 60 min (before and after DN and N) and Pearson correlations were calculated between VAS craving and Fagerström scores. The effect of smoking DN and N cigarettes on plasma nicotine levels was determined using paired t-tests between levels acquired prior to smoking (min 43) and post-smoking samples at min 49, 59, 65, 75, and 95 after tracer administration. Plasma nicotine data was not collected on one subject during the DN scan, and on another subject during the N scan.

2.4.3. Effects of group and genotype on baseline MOR BPND

A 2×2 whole-brain analysis of covariance in SPM8 was used to examine the effect of group (smokers vs. controls) and genotype (AA vs. *G at the A118G polymorphism) on baseline MOR BPND (10–40 min post-tracer administration), as well as any interactions between group and genotype. The genotype frequencies for smokers were 14AA, 4AG, and 1GG; for nonsmokers they were 15AA, 5AG and 2GG.

2.4.4. Effects of DN and N smoking on MOR BPND

Differences between baseline BPND values preceding DN (after overnight abstinence) and after DN (prior to N), reflecting potential effects of DN smoking on endogenous opioid release, were examined in SPM8 using voxel-by-voxel paired t-tests with scan order as a covariate. Due to technical difficulties, this sample included n=16 smokers. Similar analyses were conducted to examine differences between DN and N effects, controlling for their preceding baseline BPND values and scan order (n=19).

Regions that were significant after cluster-level FWE correction (p<0.05) or approached significance (p<0.06) were extracted for further analysis using MarsBaR (Brett et al, 2002). Only areas with BPND values greater than 0.1 were included in the analyses, to exclude regions with nonspecific binding. Correlations between BPND in these regions of interest, baseline VAS craving, and participants’ Fagerström scores were examined using SPSS and Pearson correlations at p<0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline MOR BPND in smokers compared to nonsmokers

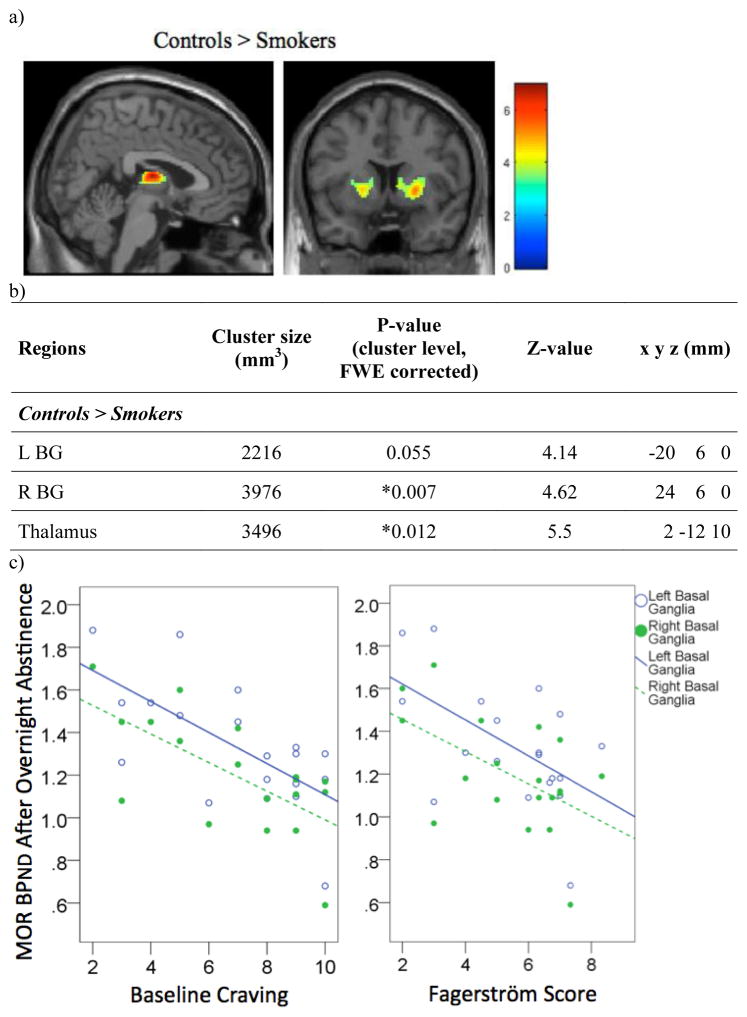

Two-way analysis of covariance showed an effect of group on MOR BPND at baseline. Healthy controls showed significantly higher BPND than smokers in the right basal ganglia (BG) and the thalamus, with differences approaching significance in the left basal ganglia (Figure 1a, 1b). BPND in the left and right BG of smokers was negatively correlated with baseline craving (L BG: r(17)=−0.67, p=0.002; R BG: r(17)=−0.68, p=0.001) (Figure 1c). Fagerström score was also negatively correlated with MOR BPND in the same regions (L BG: r(17)=−0.55, p=0.014; R BG: r(17)=−0.54, p=0.017) (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Relationship between MOR BP and smoking status. a) Regions where MOR BPND is greater in controls than in overnight abstinent smokers. b) Cluster size, cluster-level FWE-corrected p-value, Z-value, and coordinates of regions. c) Plot showing Pearson correlations between MOR BPND and craving or Fagerström score in overnight abstinent smokers.

* Regions where FWE corrected cluster significance is <0.05.

3.2. Effects and interactions of 118G allele and smoking status on baseline MOR BPND

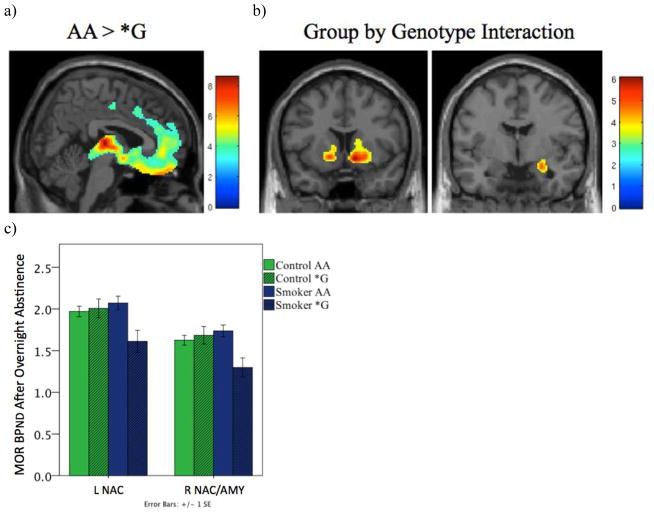

Two-way ANCOVA showed an overall significant effect of genotype, with G-allele carriers showing lower baseline BPND than AA homozygous individuals throughout brain areas with specific binding, most prominently in the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, insular cortex, nucleus accumbens (NAC), and thalamus (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Interaction between smoking status and A118G genotype. a) Regions where AA individuals have higher baseline MOR BPND than *G individuals. b) Regions where there is an interaction between group and genotype. c) Bar graph of the mean baseline MOR BPND ±1 SEM for regions shown in 2b. In the left nucleus accumbens (L NAC) and right nucleus accumbens/amygdala (R NAC/AMY), the presence of the 118G allele was associated with decreased BPND in smokers, but not in controls. d) Table showing cluster size, cluster-level FWE-corrected p-value, Z-value, and coordinates of regions showing an interaction between group and genotype.

* Regions where FWE corrected cluster significance is <0.05.

A significant interaction between group and genotype was also observed in the right amygdala and NAC, and the interaction approached significance in the left NAC (Figure 2b–d). For controls, A118G genotype did not have a significant effect on baseline BPND in those regions (L NAC: F(1,36)=0.135, p=0.719; R NAC/Amygdala: F(1,36)=0.355, p=0.555). G-carrier smokers, however, showed lower BPND values compared to AA homozygotes (L NAC: F(1,36)=10.921, p=0.002; R NAC/Amygdala: F(1,36)=12.531, p=0.001) (Figure 2c).

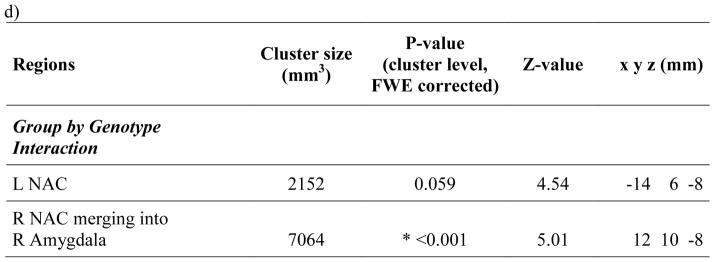

3.3. Craving, plasma nicotine levels, and Fagerström scores in smokers

Craving scores were significantly reduced after both the DN cigarette (t(18)=5.89, p<0.0001) and the N cigarette (t(18)=6.64, p<0.0001) compared to ratings prior to smoking. Craving during N scans was significantly lower than during DN scans, both at 30 min (post-DN smoking, pre-N smoking) (t(18)=3.34, p=0.004) and at 60 min (post-N smoking) (t(18)=3.71, p=0.002) (Figure 3a). No significant differences were found in the degree of craving relief afforded by N compared to DN cigarettes (t(18)=−0.35, p=0.732). There were no significant effects of OPRM1 A118G genotype on craving measures.

Figure 3.

Change in craving and plasma nicotine levels in response to DN and N smoking. a) Mean visual analog scale ratings for craving (from 1–10, with 10 being highest craving). Ratings were taken before each DN scan (Pre-scan), at 30 min into the DN and N scans (before receiving the cigarettes: Pre-DN, Pre-N), and at 60 minutes into the DN and N scans, (after receiving the cigarettes: DN, N). b) Mean plasma nicotine levels (ng/mL) after smoking either the DN or the N cigarettes. Error bars show ±1 SEM. *p<0.01. **p ≤0.001.

Smokers with higher Fagerström scores had higher baseline craving (r(17)=0.69, p=0.001) and a greater reduction in craving after both DN (r(17)=0.65, p=0.003) and N cigarettes (r(17)=0.51, p=0.026). Both the DN and the N cigarettes significantly increased plasma nicotine levels from pre-smoking levels (pre-DN vs. post-DN: t(17)=−3.26, p=0.005; pre-N vs. post-N: t(17)=−3.953, p=0.001), but with plasma nicotine levels at all time points after N being significantly higher than the corresponding plasma nicotine levels after DN (p<0.001) (Figure 3b). After DN smoking, plasma nicotine levels peaked at min 59 (mean ± SD: 3.2 ± 1.9 ng/ml), and after N smoking levels peaked at min 65 (mean ± SD: 16.4 ± 8.1 ng/ml).

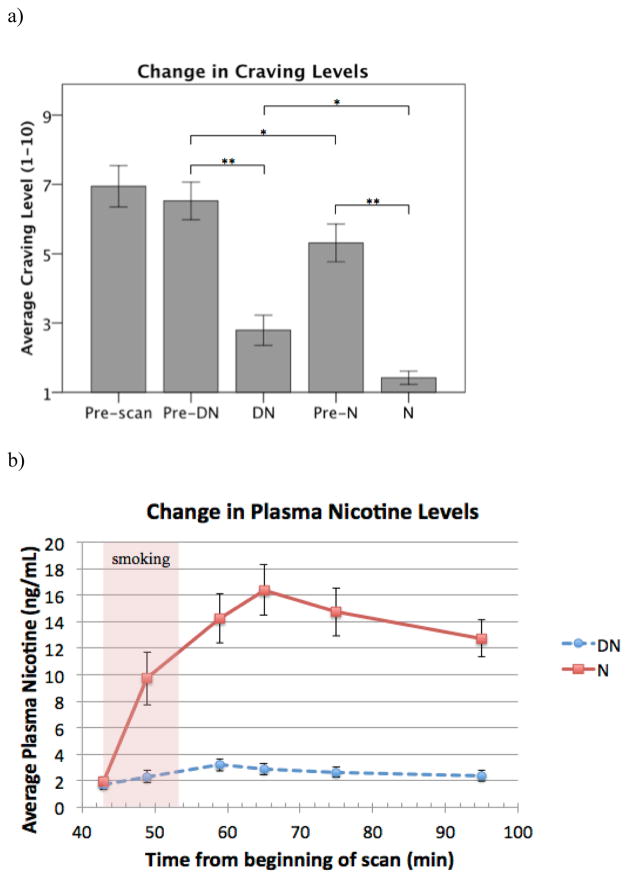

3.4. Effect of DN smoking

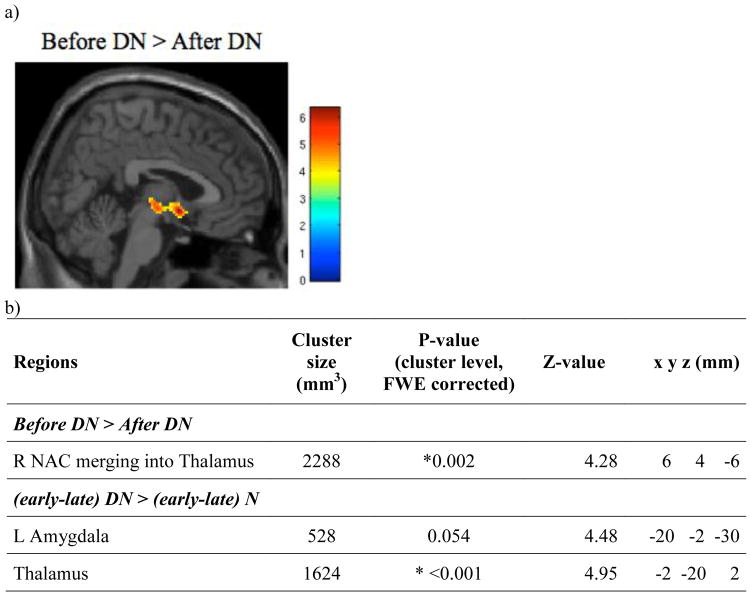

Early baseline scan (10–40 min) MOR BPND (before DN) was significantly higher than that following DN (before N) in an area that included the thalamus and the right NAC (Figure 4), suggesting a substantial activation of endogenous opioid neurotransmission in these areas after DN that persisted into the following scanning period. No significant correlations were found between the changes in BPND and Fagerström scores, craving ratings, or plasma nicotine levels. There were also no significant effects of OPRM1 A118G genotype.

Figure 4.

Effects of smoking. a) Brain regions showing greater MOR BPND before the DN cigarettes than after the DN cigarettes. b) Cluster size, cluster-level FWE-corrected p-value, Z-value, and coordinates of the regions of interest shown in Figure 4a, as well as regions where the change in BP from the early to late portion of the scan differs between the DN and N scans ((early-late) D > (early-late) N) (Figure 5).

* Regions where FWE corrected cluster significance is <0.05.

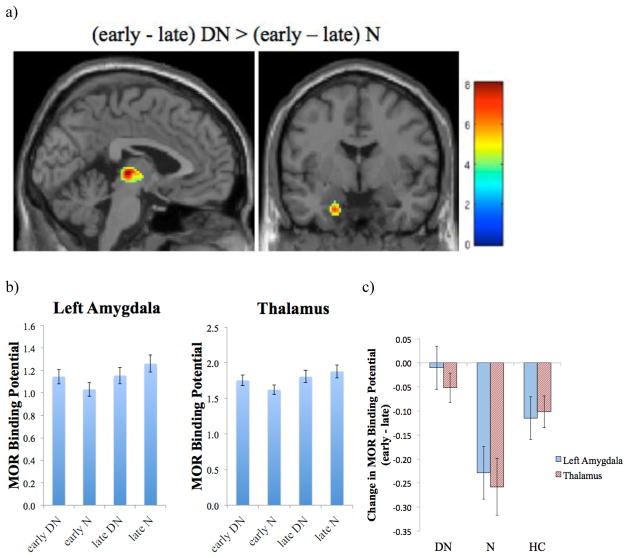

3.5. Effect of N smoking

To isolate the effects of DN versus N smoking, we controlled for the above baseline differences in MOR BPND during the early scans preceding DN and N. For this purpose we first subtracted the late portion of each scan (DN or N) from the earlier baseline portion and then examined differences between DN and N smoking effects. In these analyses, we observed greater activation of neurotransmission during DN smoking compared to N smoking, and net increases in BPND in the thalamus and left amygdala during the N scan compared to the DN scan, suggesting an overall effect of deactivation of neurotransmission during N smoking relative to DN smoking in these regions (Figures 4b, 5). There were no significant increases in MOR BPND during DN compared to N scans. No significant effects of OPRM1 A118G genotype were observed in these analyses.

Figure 5.

Effects of N smoking compared to DN smoking. a) Regions where the increase in MOR BPND from the early (min 10–40) to the late (min 45–90) portion of the scan is greater in N scans than in DN scans. b) MOR BPND in the left amygdala and thalamus during the early and late portions of both the DN and the N scans. c) Change in MOR BPND from the early to the late portion of the DN and N scans, and for the baseline scans of the healthy controls (HC). Error bars show ±1 SEM.

Fagerström scores were negatively correlated with changes in BPND in the thalamus during the DN scan (r(15)=−0.52, p=0.031) and the N scan (r(15)=−0.65, p=0.005), with greater relative activation of neurotransmission observed in those with higher nicotine dependence scores. The change in craving scores after DN smoking were also inversely associated with changes in MOR BPND in the thalamus (r(15)=−0.64, p=0.006). No significant associations were observed for changes after N smoking.

4. DISCUSSION

This manuscript examined changes in endogenous μ-opioid receptor mediated mechanisms in addicted smokers during DN and N cigarette smoking in relation to a control sample of nonsmokers. We observed reductions in baseline receptor availability (BPND) in smokers after overnight abstinence compared to nonsmoking controls. These group effects were observed in the BG bilaterally and in the thalamus, regions involved in reward responsiveness and habitual behavior, and sensory integration, respectively (Graybiel, 2008; Haber and Knutson, 2010; Tyll et al, 2011). Reductions in the BG were further associated with Fagerström and craving scores, suggesting an association between the effects of chronic tobacco smoking on MORs and the severity of nicotine addiction. These data are also consistent with that acquired in an initial pilot study from our group, where reductions in MOR BPND were observed in a small sample of smokers after DN cigarette smoking in the rostral anterior cingulate, thalamus, NAC, and amygdala, in comparison with nonsmoking controls (Scott et al, 2006). Previous work by Ray et al. (2011) and Kuwabara et al. (2014), however, did not find significant differences in receptor availability between controls and smokers, a discrepancy that may be secondary to differences in the samples studied or in the study designs. Both Ray et al. (2011) and Kuwabara et al. (2014) studied males and females, who present substantial differences in MOR BPND under resting conditions (Zubieta et al, 1999), potentially increasing the variance of the measures. In contrast, the present study and Scott et al. (2006) included only males. Participants in this study also had average peak nicotine levels above 16 ng/mL, while in the study by Kuwabara et al. (2014) nicotine levels appear to have peaked around 7 ng/mL. This may have been too low a level to show significant group differences in binding, as previous electroencephalogram studies have suggested that increases of plasma nicotine levels greater than 10 ng/mL are needed before brain waves are significantly altered by smoking (Kadoya et al, 1994). There is also evidence that smokers self-regulate smoking to obtain nicotine boosts of 10 ng/mL per cigarette, a level that may be necessary to obtain many of the positive subjective effects of nicotine (Russell et al, 1995). In addition, the present study acquired baseline measures after overnight abstinence without any intervention, while others (Kuwabara et al, 2014; Ray et al, 2011) used scans acquired after DN smoking as surrogate baselines, which may introduce an additional confound, as noted below. Similarly to the present report, Kuwabara et al. (2014) observed negative correlations between MOR BPND and Fagerström score during the DN condition, albeit in different regions.

The observed reductions in baseline MOR BPND would be consistent with a chronic activation of this neuropeptide signaling system as a result of smoking and subsequent receptor downregulation, effects similar to those observed for dopamine and dopamine D2 receptors (Brody et al, 2004). It is also possible that overnight nicotine abstinence induced acute increases in endogenous opioid production, as suggested by data in animal models (Houdi et al, 1998; Isola et al, 2002), further reducing the receptor availability measures acquired in vivo.

In animal models, chronic exposure to nicotine has been shown to reduce MOR levels, an effect that was linked to the development of tolerance to nicotine (Galeote et al, 2006). However, the opposite effect has also been observed, with increases in MOR receptor concentrations after chronic administration that were associated with nicotine-induced reward conditioning (Walters et al, 2005). These upregulatory effects have also been shown to be sex dependent, more prominent in female than in male rodents, and associated with reductions in intracellular content of met-enkephalin (Wewers et al, 1999).

Smoking status also interacted with OPRM1 A118G genotype, whereby reductions in MOR BPND were observed in G allele carriers but only in smokers, not in nonsmoking controls, similar to data presented in Ray et al. (2011). Presence of the G allele has been associated with lower levels of MOR mRNA expression in human post-mortem tissue (Zhang et al, 2005), in cultured cells (Kroslak et al, 2007), and in animal models (Mague et al, 2009; Wang et al, 2012). In larger healthy control samples, G allele carriers have also shown reductions in MOR BPND in multiple cortical and subcortical brain regions, when compared to AA homozygotes (Pecina et al, 2015b). The significant interaction between smoking status and genotype found in this study are therefore likely to represent an additive effect of chronic smoking and G-allele reducing MOR availability, which would not be present in the control group and may not have been detected with the small control sample sizes employed in this report and in Ray et al. (2011). Peciña et al. (2015b) studied a much larger healthy control sample, but did not include smokers. In smokers, lower levels of receptor availability were associated with higher Fagerström nicotine dependence scores and higher craving ratings in both the present report and in Kuwabara et al. (2014). In nonsmokers, lower regional MOR BPND values in G-allele carriers have been linked to higher trait NEO Neuroticism scores, and specifically to the two subscales Vulnerability to Stress and Depression (Pecina et al, 2015b).

During the smoking phases of the study, both DN and N cigarettes significantly reduced craving after overnight abstinence, an observation that parallels the results of prior studies examining the effect of DN and N smoking on subjective reports of tobacco withdrawal symptoms, including craving (Butschky et al, 1995; Pickworth et al, 1999). The non-nicotine effects of smoking were highlighted in a recent study showing that smokers would preferentially self-administer DN cigarette puffs over intravenous nicotine (Rose et al, 2010), suggesting the importance of secondary, nicotine non-specific, reinforcing effects of smoking, which include sensory aspects such as the taste, smell, and feel of the cigarette smoke. In our study we observed lower craving levels immediately prior to and after N smoking compared to the same periods in the preceding DN scans, further suggesting that smoking the DN cigarette after overnight abstinence had substantial effects that carried over into the subsequent N smoking scanning period. The effects of both DN and N smoking were also dependent on the severity of nicotine addiction, with higher Fagerström scores associated with greater craving after overnight abstinence and more profound reductions in craving ratings after both DN and N cigarettes.

These non-specific effects of smoking, observed at the behavioral level, were paralleled by the results of the molecular measures acquired. In the experimental design employed, baselines were acquired prior to DN and N smoking acquisitions, which were not randomized in order. The rationale for this design was that the baseline periods, acquired early in the scan, would allow for the assessment of a “true” baseline prior to the introduction of any challenge. Comparisons between the effects of DN and N smoking can then be carried out across early periods as well as across late periods with similar signal to noise ratios, as tracer decay may differentially affect BPND estimates acquired early and late during scanning. Potential carry-over effects of the DN challenge would then be reflected in the following baseline, while N smoking, expected to have substantial carry over effects, would not affect DN BPND estimates.

We observed significant reductions in MOR BPND from the period preceding compared to that following DN smoking in the thalamus and amygdala, suggesting that DN smoking alone elicited a substantial release of endogenous opioid peptides. It should be noted that the minimal amounts of nicotine in the DN cigarettes did cause a boost in plasma nicotine levels of approximately 1.5 ng/mL. While it is possible this could partially explain the increase in endogenous opioid release following the DN cigarettes, evidence from the studies mentioned earlier suggest a nicotine level increase of 10 ng/mL is needed before pharmacological effects of nicotine are observed (Kadoya et al, 1994; Russell et al, 1995).

In parallel, and accounting for differences in baseline values across scans, relatively greater activation of endogenous opioid neurotransmission was observed for DN, in relation to N smoking during the late scanning periods. In the thalamus, Fagerström scores were correlated with activation of neurotransmission after smoking both the DN and the N cigarettes. The change in craving ratings was likewise associated with differential levels of activation in neurotransmission after DN smoking in the thalamus. These results then suggest that after overnight abstinence, when craving is highest, nicotine non-specific effects are prominent, inducing the release of endogenous opioids and μ-opioid receptor activation, which in the present study largely obscured additional effects of nicotine during N smoking, and are consistent with prior experimental observations (Butschky et al, 1995; Pickworth et al, 1999; Rose et al, 2010). The recent study by Domino et al. (2015) used a number of the same subjects but compared DN and N smoking directly without taking into account differences caused by the DN smoking. It is possible that endogenous opioid release caused by the DN cigarette could account for why that method of analysis found regions that showed both increases (left amygdala, left putamen, left NAC) and decreases (prefrontal cortex, right ventral striatum, left insula, right hippocampus) in MOR BPND after subjects smoked the N cigarette compared to the DN cigarette. The present analysis also used a more stringent statistical threshold, and only found two regions that showed differences between DN and N smoking: the left amygdala, a region observed to change in the previous study, and the thalamus.

MORs in the thalamus and amygdala, regions implicated in the regulation of sensory and emotionally relevant information (Gallagher and Chiba, 1996; Tyll et al, 2011), are known to be implicated in homeostatic responses of the organism to salient environmental cues. In the context of pain, but also in Major Depression, activation of MOR-mediated neurotransmission by expectations of symptom relief during placebo administration has been observed in these and other brain regions (Pecina et al, 2015a; Scott et al, 2008; Zubieta et al, 2005). It is therefore likely that DN smoking, particularly after overnight abstinence, when nicotine withdrawal distress and craving are high, would represent a strong environmental cue that induced a potent activation of MOR-mediated neurotransmission independent of nicotine content in the cigarettes.

These observations are relevant for the treatment of nicotine addiction. They would imply that under similar conditions of taste and appearance, reductions in nicotine content in cigarettes, particularly those consumed during early abstinence would be possible and still afford craving relief in nicotine-addicted individuals. This would allow for progressive reductions in nicotine consumed shortly after awakening, one of the hallmarks of nicotine dependence.

Further exploration of these processes appears warranted, given the high retention of addiction among heavy smokers. The results acquired in this study highlight the importance of non-specific elements of cigarette smoking. Future studies examining the effects of nicotine and smoking on brain function should take these processes into account by using sham comparison controls and employing full randomization of DN and N smoking.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study shows that overnight-abstinent smokers have decreased MOR BPND compared to nonsmoking controls, and that those individuals with the lowest MOR BPND in the basal ganglia also had higher nicotine dependence scores and greater craving after overnight nicotine abstinence. Preliminary results also suggest that A118G genotype may differentially affect MOR BPND in smokers vs. nonsmokers, a relationship that should be further explored. Finally, DN smoking was associated with endogenous opioid release as well as significant decreases in craving, demonstrating the power of the placebo effect, or non-nicotine factors, in modulating these systems.

Highlights.

Nonsmokers show greater MOR binding potential than overnight-abstinent smokers

Higher craving and nicotine dependence are associated with decreased MOR binding

A118G genotype differentially affected MOR binding in smokers vs. nonsmokers

Denicotinized cigarette smoking resulted in endogenous opioid release

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported in part by the Department of Pharmacology Research and Development Fund 276157, the Psychopharmacology Fund C361024, and Phil F. Jenkins Foundation, and National Institute on Drug Abuse grants R01DA016423 (E.F.D.) and R01DA027494 (J.K.Z.). E.B.N. was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants 5T32EY017878 and 5T32DA007281.

Cigarettes were obtained by the courtesy of Dr. Frank Gullotta and Ms. Cynthia Hayes of the Philip Morris Research Center, Richmond, VA. Data was collected with the help of Dr. Catherine Evans. The authors also wish to acknowledge the nuclear medicine technologists at the Positron Emission Tomography Center at the University of Michigan for the assistance in PET data acquisition and reconstruction.

List of abbreviations

- PET

positron emission tomography

- BPND

non-displaceable binding potential

- MOR

μ-opioid receptor

- CFN

carfentanil

- RCL

raclopride

- OPRM1

human μ-opioid receptor

- BG

basal ganglia

- NAC

nucleus accumbens

- DN

denicotinized

- N

nicotine

- HC

healthy controls

- VAS

visual analog scale

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arias A, Feinn R, Kranzler HR. Association of an Asn40Asp (A118G) polymorphism in the μ-opioid receptor gene with substance dependence: A meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83(3):262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjieva NI, Sarkar DK. The secretory response of hypothalamic beta-endorphin neurons to acute and chronic nicotine treatments and following nicotine withdrawal. Life Sci. 1997;61(6):PL59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett M, Anton JL, Valabrague R, Poline J-B. Region of interest analysis using MarsBar toolbox for SPM 99. Neuroimage. 2002;16:497. [Google Scholar]

- Brody AL, Olmstead RE, London ED, Farahi J, Meyer JH, Grossman P, et al. Smoking-induced ventral striatum dopamine release. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(7):1211–1218. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butschky MF, Bailey D, Henningfield JE, Pickworth WB. Smoking without nicotine delivery decreases withdrawal in 12-hour abstinent smokers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;50(1):91–96. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)00269-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport KE, Houdi AA, Van Loon GR. Nicotine protects against μ-opioid receptor antagonism by β-funaltrexamine: Evidence for nicotine-induced release of endogenous opioids in brain. Neurosci Lett. 1990;113(1):40–46. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90491-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domino EF, Evans CL, Ni L, Guthrie SK, Koeppe RA, Zubieta J-K. Tobacco smoking produces greater striatal dopamine release in G-allele carriers with mu opioid receptor A118G polymorphism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;38(2):236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domino EF, Hirasawa-Fujita M, Ni L, Guthrie SK, Zubieta JK. Regional brain [(11)C]carfentanil binding following tobacco smoking. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2015;59:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domino EF, Ni L. Clinical phenotyping strategies in selection of tobacco smokers for future genotyping studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26(6):1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domino EF, Ni L, Domino JS, Yang W, Evans C, Guthrie S, et al. Denicotinized versus average nicotine tobacco cigarette smoking differentially releases striatal dopamine. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):11–21. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeote L, Kieffer BL, Maldonado R, Berrendero F. Mu- opioid receptors are involved in the tolerance to nicotine antinociception. J Neurochem. 2006;97(2):416–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher M, Chiba AA. The amygdala and emotion. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6(2):221–227. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graul AI, Prous JR. Executive summary: Nicotine addiction. Drugs of Today. 2005;41(6) doi: 10.1358/dot.2005.41.6.914907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM. Habits, rituals, and the evaluative brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:359–387. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber SN, Knutson B. The reward circuit: linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):4–26. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdi AA, Dasgupta R, Kindy MS. Effect of nicotine use and withdrawal on brain preproenkephalin A mRNA. Brain Res. 1998;799(2):257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, Fujita M, Gjedde A, Gunn RN, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(9):1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isola R, Zhang H, Duchemin A-M, Tejwani GA, Neff NH, Hadjiconstantinou M. Met-enkephalin and preproenkephalin mRNA changes in the striatum of the nicotine abstinence mouse. Neurosci Lett. 2002;325(1):67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett DM. A simple synthesis of [11C]carfentanil using an extraction disk instead of HPLC. Nucl Med Biol. 2001;28(6):733–734. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(01)00226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoya C, Domino EF, Matsuoka S. Relationship of electroencephalographic and cardiovascular changes to plasma nicotine levels in tobacco smokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55(4):370–377. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroslak T, Laforge KS, Gianotti RJ, Ho A, Nielsen DA, Kreek MJ. The single nucleotide polymorphism A118G alters functional properties of the human mu opioid receptor. J Neurochem. 2007;103(1):77–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara H, Heishman SJ, Brasic JR, Contoreggi C, Cascella N, Mackowick KM, et al. Mu Opioid Receptor Binding Correlates with Nicotine Dependence and Reward in Smokers. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e113694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Alexoff DL. Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16(5):834–840. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mague SD, Isiegas C, Huang P, Liu-Chen LY, Lerman C, Blendy JA. Mouse model of OPRM1 (A118G) polymorphism has sex-specific effects on drug-mediated behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(26):10847–10852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901800106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. Manual for the profile of mood states. Educational and Industrial Testing Service; San Diego, CA: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Pecina M, Bohnert AS, Sikora M, Avery ET, Langenecker SA, Mickey BJ, et al. Association Between Placebo-Activated Neural Systems and Antidepressant Responses: Neurochemistry of Placebo Effects in Major Depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015a;72(11):1087–1094. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecina M, Love T, Stohler CS, Goldman D, Zubieta JK. Effects of the Mu opioid receptor polymorphism (OPRM1 A118G) on pain regulation, placebo effects and associated personality trait measures. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015b;40(4):957–965. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickworth WB, Fant RV, Nelson RA, Rohrer MS, Henningfield JE. Pharmacodynamic effects of new de-nicotinized cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 1999;1(4):357–364. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF. Endogenous opioids and smoking: A review of progress and problems. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23(2):115–130. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray R, Ruparel K, Newberg A, Wileyto EP, Loughead JW, Divgi C, et al. Human Mu Opioid Receptor (OPRM1 A118G) polymorphism is associated with brain mu-opioid receptor binding potential in smokers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(22):9268–9273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018699108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Salley A, Behm FM, Bates JE, Westman EC. Reinforcing effects of nicotine and non-nicotine components of cigarette smoke. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1810-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell MAH, Stapleton JA, Feyerabend C. Nicotine boost per cigarette as the controlling factor of intake regulation by smokers. In: Clarke PBS, Quik M, Adlkofer F, Thurau K, editors. Effects of nicotine on biological systems II. Birkhäuser; Basal, Switzerland: 1995. pp. 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Scott DJ, Domino EF, Heitzeg MM, Koeppe RA, Ni L, Guthrie S, et al. Smoking Modulation of |[mu]|-Opioid and Dopamine D2 Receptor-Mediated Neurotransmission in Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;32(2):450–457. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DJ, Stohler CS, Egnatuk CM, Wang H, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK. Placebo and nocebo effects are defined by opposite opioid and dopaminergic responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(2):220–231. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Tyll S, Budinger E, Noesselt T. Thalamic influences on multisensory integration. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4(4):378–381. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.4.15222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters CL, Cleck JN, Kuo YC, Blendy JA. Mu-opioid receptor and CREB activation are required for nicotine reward. Neuron. 2005;46(6):933–943. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YJ, Huang P, Ung A, Blendy JA, Liu-Chen LY. Reduced expression of the mu opioid receptor in some, but not all, brain regions in mice with OPRM1 A112G. Neuroscience. 2012;205:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule--expanded form. University of Iowa; Iowa City, IA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Weerts EM, McCaul ME, Kuwabara H, Yang X, Xu X, Dannals RF, et al. Influence of OPRM1 Asn40Asp variant (A118G) on [11C]carfentanil binding potential: preliminary findings in human subjects. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(1):47–53. doi: 10.1017/S146114571200017X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wewers ME, Dhatt RK, Snively TA, Tejwani GA. The effect of chronic administration of nicotine on antinociception, opioid receptor binding and met-enkelphalin levels in rats. Brain Res. 1999;822(1–2):107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsley KJ, Evans AC, Marrett S, Neelin P. A three-dimensional statistical analysis for CBF activation studies in human brain. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1992;12(6):900–918. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wang D, Johnson AD, Papp AC, Sadée W. Allelic Expression Imbalance of Human Mu Opioid Receptor (OPRM1) Caused by Variant A118G. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(38):32618–32624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Bueller JA, Jackson LR, Scott DJ, Xu Y, Koeppe RA, et al. Placebo effects mediated by endogenous opioid activity on mu-opioid receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25(34):7754–7762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0439-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Dannals RF, Frost JJ. Gender and age influences on human brain mu-opioid receptor binding measured by PET. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(6):842–848. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Ketter TA, Bueller JA, Xu Y, Kilbourn MR, Young EA, et al. Regulation of human affective responses by anterior cingulate and limbic mu-opioid neurotransmission. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(11):1145–53. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]