Abstract

Background:

Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5) is a target of Wnt signalling and considered both a cancer stem cell marker and intestinal stem cell marker. We found first some splice variants of LGR5 in human intestine and elucidated the functional feature of full-length LGR5 (LGR5FL).

Methods:

Reverse transcript PCR using mRNA extracted from intestine revealed the existence of LGR5 splice variants. We designed an antibody that recognises only LGR5FL and assessed immunohistochemically the distribution of LGR5FL-positive cells and Ki-67-positive cells in clinical samples.

Results:

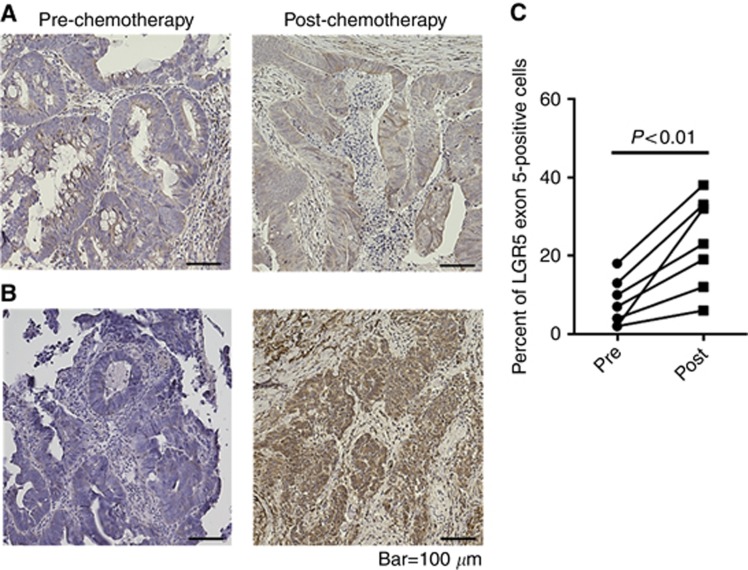

Two LGR5 splice variants were expressed in the human intestine crypt cells; one lacked exon 5 and the other lacked exons 5–8. Only LGR5FL appeared during cell cycle arrest, whereas the transcript variants appeared when the cell cycle was proceeding. Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridisation showed that LGR5FL-positive cells were negative for Ki-67. Comparing prechemotherapy and post-chemotherapy specimens, the population of LGR5FL-positive cells significantly increased with therapy (P<0.01).

Conclusions:

The function of LGR5FL-positive cells had low cell proliferative ability compared with the cells, which expressed splice variants of LGR5 and remained after chemotherapy. Designing therapeutic strategies that target LGR5FL-positive cells seems to be important in colorectal cancer.

Keywords: LGR5, splice variants, Ki-67, colorectal cancer, cell cycle, antitumour drug resistance

Leucine-rich repeat containing G-protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5), also referred to as GPR49, was identified as a leucine-rich, orphan G-protein-coupled seven-transmembrane receptor belonging to the G-protein-coupled receptor family. Using linear tracing in a mouse model, Barker et al, (2007) reported that LGR5 is expressed specifically in the crypt base columnar cells (CBCCs), and LGR5-positive cell were implied to be pluripotent and capable of self-renewal. Moreover, in an in vitro study, single LGR5-positive cells built crypt–villus structures, including enteroendocrine and crypt Paneth cells (Sato et al, 2009). These findings suggest that LGR5-positive cells are intestinal stem cells (ISCs) that generate rapidly proliferating transit-amplifying (TA) cells (Barker, 2014).

LGR5 is a target of Wnt signalling and acts as a receptor for R-spondins (RSPOs) (De Lau et al, 2011). After binding RSPOs, LGR5 forms a protein complex with Rnf43 and frizzled lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 and 6 (LRP5/6), interfering with degradation of the crucial signalling molecule β-catenin. Accumulated β-catenin could translocate to the nucleus and regulate the expression of a wide range of target genes (Birchmeier, 2011; De Lau et al, 2011).

The Wnt pathway has an important role in cell proliferation (Reya and Clevers, 2005). Mutations in APC and β-catenin, which are involved with Wnt pathway, have been reported to evoke hyperactivation of the Wnt pathway and development of adenoma in the intestine (Moser et al, 1990; Su et al, 1992; Harada et al, 1999; Koo and Clevers, 2014). LGR5 is considered to be involved in carcinogenesis; evidence indicates that LGR5 is cancer stem cell (CSC) marker and ISC marker. LGR5-positive cells have been shown to drive tumorigenesis in the small intestine and colon (Barker et al, 2009; Schepers et al, 2012). LGR5high cancer cells were demonstrated to have higher clonogenic potential in vitro and higher tumorigenicity in vivo compared with LGR5low cancer cells (Merlos-Suarez et al, 2011; Kemper et al, 2012). Elevated LGR5 expression has been observed in several types of cancer, including colorectal cancer (Takahashi et al, 2011), hepatocellular carcinoma (Yamamoto et al, 2003b), and basal cell carcinoma (Tanese et al, 2008). Several papers have reported a correlation between LGR5 overexpression and poor prognosis among colorectal cancer (CRC) patients (Takahashi et al, 2011; Chen et al, 2014). These findings indicate that LGR5 is a novel, functional CSC marker. Interestingly, LGR5-positive cells have two antithetical features: as an ISC marker with rapid cell cycle, and as a CSC marker in a quiescent state (Visvader and Lindeman, 2008).

LGR5 consists of 18 exons, with exons 1–17 constituting extracellular leucine-rich repeats (LRRs). The binding position of R-spondin-1 to the surface of LGR5 comprises LRR domains 3–9 (De Lau et al, 2014), implying that the structure of the LRR is important for LGR5 function. To the best of our knowledge, there are two transcript variants of LGR5: one lacking exon 5 (LGR5Δ5) and published in the ExPasy UniprotKB-data bank as variant VSP_ 054782, the other lacking exon 8 and published in the same database as variant VSP_037746 (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O75473). In a single report, the low expression of LGR5Δ5 mRNA was a negative prognostic marker in soft-tissue sarcoma (Rot et al, 2011). It is unclear whether there are any transcript variants in CRC, and there have been no reports assessing the LGR5 transcript variants in CRC. LGR5 belongs to the LGR family, which is defined by a large ectodomain composed of LRRs (Van Hiel et al, 2012). LGR7 is also a member of the LGR family, and its splice variants inhibit the function of full-length LGR7 (Kern et al, 2008). We hypothesised the presence of LGR5 splice variants in CRC and investigated whether the difference between full-length LGR5 (LGR5FL) and its isoforms affects the characteristics of CRC.

Here we report multiple LGR5 transcript variants in normal ileum and colon. We elucidated the distribution of LGR5 isoforms in the intestine and assessed the functional difference among these transcript variants in respect to cell proliferation. Moreover, we constructed a rabbit polyclonal antibody that recognises only LGR5FL and assessed the effect of chemotherapy on LGR5FL-positive cells.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

All clinical samples, including ileum, ascending colon, transverse colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and CRC, were collected from CRC patients who underwent surgery or biopsy at the Department of Gastroenterological Surgery of Osaka University. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Institutional Research Board for co-principal investigators, H Yamamoto, Y Doki, M Mori, and H Ishii (the approved protocol numbers were #08226 and #213).

Cell culture

HEK293 cells and human colorectal cancer cell lines SW480, Caco2, DLD1, HT29, KM12sm, Lovo, and HCT116 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) in 2001. Stocks were prepared after passage 2 in liquid nitrogen. All experiments were performed with cells of <8 passages. These cell lines were authenticated by morphological inspection, short tandem repeat profiling, and Mycoplasma testing by ATCC. Mycoplasma testing was also performed by the authors. Cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

RNA extraction and reverse-transcription PCR from human intestine

Total RNA was extracted using a modified acid-guanidinium-phenol-chloroform procedure. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesised from 8 μg total RNA using hexamer primers and Moloney murine leukaemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed on a LightCycler480 system (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) with the LightCycler 480 probes master kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The amplification conditions were 95 °C for 10 min followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and of 60 °C for 30 s. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene was used as an internal control to confirm cDNA quality.

Identification of LGR5 splice variants and sequence analysis

To identify the LGR5 splice variants in the intestine, we performed PCR using cDNA prepared from the intestine. The primers were designed based on the genomic sequence from exon 1 to exon 13, which corresponds to the LRRs in the extracellular domain of LGR5. The designed primer sequences were as follows: sense primer 5′-CCAACCTCAGCGTCTTCACCTCCTACC-3′, anti-sense primer 5′-CGGAGGCTAAGCAACTGCTGGAAAGTGTC-3′. The PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. The band around 1000 bp was cut out of the gel and the DNA fragments excised from the agarose using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. Extracted PCR fragments were cloned into the PCR4-TOPO vector (Cat# K4575-02; Invitrogen) and the sequence of the extracted DNA analysed (Center for Medical Research and Education, Osaka University). To verify the exon organisation and alternative splice sites of the variants, we compared the DNA sequences to the genomic sequence of LGR5 registered with the CCDS database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/CCDS/CcdsBrowse.cgi?REQUEST=CCDS&GO=MainBrowse&DATA=CCDS9000.1).

Isolating intestinal villi and crypt

The villi and crypts were obtained from human intestine, including the ileum, caecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum, by scratching the surface of the intestine several times in PBS containing 20 mM EDTA. First, the tips of villi were collected, then the middle portion of the villi, and finally the crypts.

LGR5 overexpression in HEK293 cells

Transduction of LGR5 isoforms in HEK293 cells was performed using the pLenti6/V5 Directional TOPO Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the PCR-amplified coding sequences of LGR5FL and the LGR5 splice variants were cloned into pLenti6/V5-D-TOPO. This vector was co-transfected into 293FT cells with ViraPower packaging mix to generate the lentivirus. HEK293 cells were transduced with the lentivirus and stable cell lines generated by selecting with blasticidin. To verify that the target gene was transduced, immunofluorescence was performed using anti-V5-FITC antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Western blotting

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (Yamamoto et al, 2003a). Briefly, 20 μg of protein was separated by 12.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by electroblotting onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was incubated for 1 h with the following primary antibodies at appropriate concentrations: anti-V5 antibody (1 : 5000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and anti-Lgr5 mouse monoclonal antibody (1 : 2000, Cat# TA503316; OriGene, Rockville, MD, USA). Equal loading of the protein samples was confirmed by parallel Western blots for actin with anti-actin rabbit polyclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA). The protein bands were detected using the American Enhanced Chemiluminescence Detection System (Amersham Bioscience Corp., NJ, USA).

Starve test

Cell lines were incubated in DMEM without serum at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 36 h, followed by incubation in DMEM with 10% FBS. Cultured cells were collected 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h after starting the incubation with FBS. To analyse the expression of CDKN1A, qRT–PCR was performed using the following primer; sense primer 5′-CATGTCAGAACCGGCTGGGGATGTC-3′, anti-sense primer 5′-GTGGGCGGATTAGGGCTTCCTCTTG-3′.

In situ hybridisation and fluorescent microscopy

In situ hybridisation (ISH) for the expression of LGR5 isoforms was performed by GeneticLab., Ltd (Sapporo, Japan) using the QuantiGene ViewRNA-ISH Assay Kit with Panomics protocols (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Briefly, tissue sections (4 μm) were prepared, fixed in 4% NBF for 1 h, deparaffinised, boiled in pretreatment solution for 5 min, and digested with proteinase K (included in kit) for 20 min. Specimens were hybridised for 3 h at 40 °C with a custom-designed probe against human LGR5 exon 5 (Cat# VA1-11207-06; Affymetrix) or the full sequence (Cat# VA1-10587-01; Affymetrix). Hybridised probes were amplified using PreAmp and Amp molecules. Labelled probes conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (LP-AP, included in kit) were then added and FastRed substrate used to develop the signals (red fluorophore). The slides were then counterstained with Gills hematoxylin and DAPI. DAPI staining (blue) was used to generate the nuclear compartment. Serial sections were also subjected to haematoxylin and eosin staining per standard histology protocol. A series of high-resolution monochromatic images were captured using an automated microscope platform equipped with a 40x objective (PM-2000TM; HistoRx, New Haven, CT, USA). Fluorescent chromagens (DAPI, FastRed, and Cy5) were used to detect ISH or immunofluorescent signals within each section. Images were depicted by pseudocolour merging using the image processing software ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). ISH (FastRed) and immunofluorescent (CY5) signals were coloured in green. Nuclei were coloured with blue (DAPI).

Designing the LGR5 exon 5 antibody

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were raised against LGR5 exon 5 using two peptides with the following amino acid sequences: CHSLRHLWLDDNALTEIP and CAMTLALNKIHHIPDYAF. The antibody was ordered from MBL (Medical & Biological Laboratories Co., LTD, Japan).

Visualisation of LGR5FL localisation

Lovo cells were cultured in 24-well plates at 37 °C with 5% CO2 overnight. After washing the cells with PBS, they were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Specimens were blocked and permeabilised in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100, and then anti-LGR5 exon 5 antibody was added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) was used as a negative control. After washing the cells in PBS, they were stained by DyLight 649 Donkey anti-rabbit IgG (minimal x-reactivity) Antibody (406406; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and Hoechist 33342 (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR, USA). The plate was viewed by IN Cell Analyzer 6000 (GE Healthcare UK Ltd, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis of LGR5 and Ki-67 was performed using surgical specimens from selected patients with CRC at Osaka University. The avidin–biotin–peroxidase method (Vectastain Elite ABC reagent kit; Vector, CA, USA) was used on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Tissue sections (3.5-μm thick) were prepared from paraffin-embedded blocks. After deparaffinisation and blocking, the antigen–antibody reaction was carried out overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibody concentrations were as follows: LGR5 exon 5 antibody; 1 : 1000; Ki-67 (Ab15580, Abcam plc, Cambridge, UK), 1 : 250.

Absorption test

For the absorption test, an excess amount of immunogen peptide was added to the antibody (20 mol : 1 mol) and the mixture incubated overnight at 4 °C.

Proliferation assay with 5-FU and anti-LGR5 exon 5 antibody

Cells, DLD1 and LOVO, were seeded at a density of 2000 cells per well in 96-well dishes, with 5-FU (0.5 μg ml−1), normal rabbit IgG, anti-LGR5 exon 5 antibody (10 μg ml−1). Cells were cultured for 48 h and 72 h and cell counting was performed with Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Kumamoto, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP software version 11.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Possible differences between groups were analysed using Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test appropriately. The population of LGR5 exon 5-positive cells was their ratio among all tumour cells in 50 HPF. A probability level of 0.05 was chosen to indicate significance.

Results

LGR5 splice variant mRNA in clinical specimens

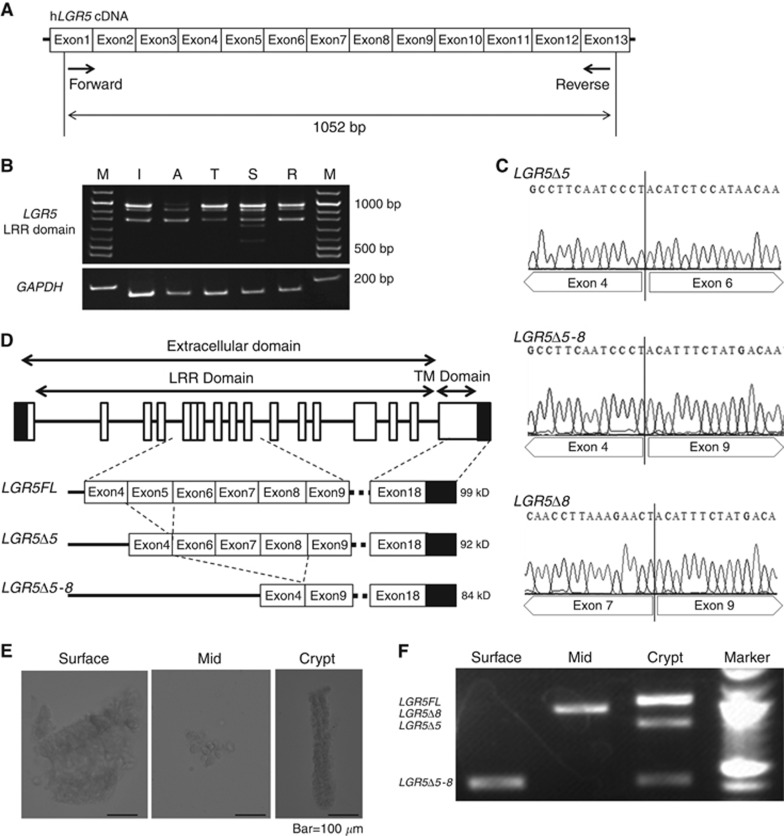

First, we verified the existence of LGR5 splice variants mRNA in clinical specimens. We designed the primer that could detect the LRR domain of LGR5 as shown in Figure 1A. RT–PCR of mRNA from each part of the intestine resulted in several bands, implying the presence of several types of LGR5 variants (Figure 1B). The sequence analysis of these bands revealed there were three LGR5 splice variants, which were deficient in exon 5 (LGR5Δ5), exons 5–8 (LGR5Δ5–8), and exon 8 (LGR5Δ8; Figure 1C). The schema of LGR5FL, LGR5Δ5, and LGRΔ5–8 isoforms is shown in Figure 1D.

Figure 1.

LGR5 splice variants were identified from a clinical sample.(A) Schematic of the primer design corresponding to LRR. The forward primer corresponds to exon 1 and reverse primer to exon 13. The amplicon is 1052 bp. (B) Electrophoresis of PCR products obtained from RT–PCR against each part of the intestine showed multiple bands around 1000 bp. (C) Sequence analysis of the PCR products showed three kinds of LGR5 splice variants. One is deficient in exon 5, another is deficient in exons 5–8, and the other is deficient in exon 8. (D) Schematic representation of the exons constituting the LGR5 isoforms in the intestine. (E) Microscopic picture of the colonic villi removed by chemical dissection using EDTA. Initially, the tips of villi were taken, the middle part of the villi obtained, and then finally the crypts were taken. (F) Electrophoresis of PCR products obtained from RT–PCR against each part of the villi. The LGR5FL bands only appeared with the amplicon from the crypt.

To examine whether the expression of these variants depended on the site of the villi, we performed RT–PCR with the same primer for the villi and crypts from the small intestine. First, we chemically dissected the resected colon using EDTA and collected each part of the villi while observing the resected epithelial cells under the microscope (Figure 1E). Next, we extracted the mRNA from the collected villi and performed RT–PCR. The bands for the LGR5 splice variants were recognised in the middle and tips of the villi, but the LGR5FL mRNA was expressed only in the crypts (Figure 1F). Interestingly, the mRNA of LGR5Δ8 was not expressed in the crypt, therefore, we focused on LGR5FL, LGR5Δ5, and LGR5Δ5–8 in further experiments.

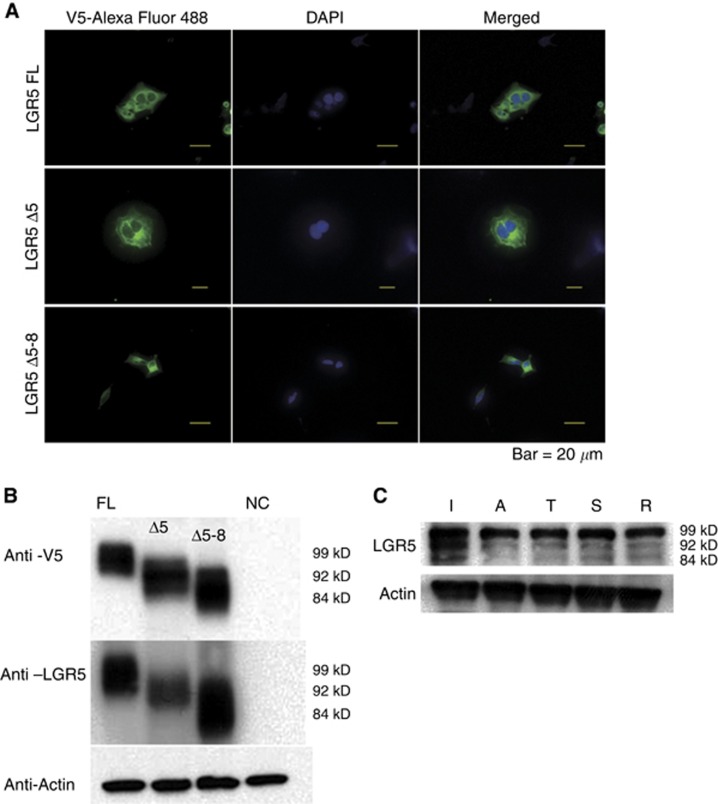

LGR5 splice variant mRNA were translated to protein

In order to analyse that the mRNA of each LGR5 splice variants were translated to protein, we overexpressed the LGR5FL, LGR5Δ5, and LGR5Δ5–8 genes in HEK293 cells. We confirmed that these genes were transfected correctly by immunofluorescence (Figure 2A). Western blot analysis revealed LGR5FL protein but the proteins encoded by the LGR5 splice variants, including LGR5Δ5 and LGR5Δ5–8 (Figure 2B). In addition, western blot analysis of a clinical sample showed that the proteins of these isoforms were expressed endogenously in the ileum, colon, and rectum (Figure 2C). Thus, the LGR5 isoforms were not only present at the mRNA level, but also translated to proteins.

Figure 2.

Each LGR5 isoform was translated to protein.(A) Immunofluorescent analysis of HEK293 cells. LGR5 isoforms were tagged with V5, which was conjugated by Alexa Fluor 488 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (B) Western blotting showed the bands of each isoform. (C) Endogenous expression of the LGR5 isoforms was detected at the protein level.

Functional analysis in vitro among LGR5 isoforms

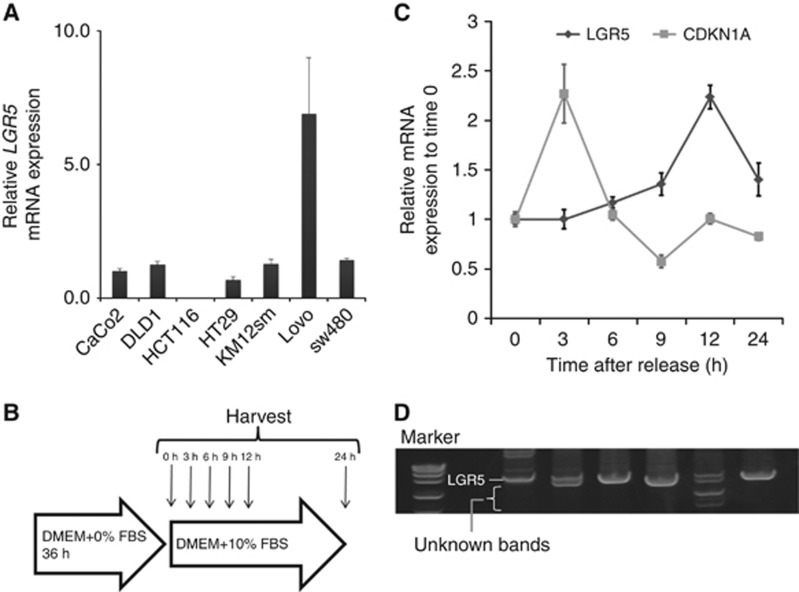

We examined the biological difference between LGR5FL and its splice variants. The function of LGR5 is relative to the Wnt signal, which regulates cell proliferation (Reya and Clevers, 2005). Therefore, we speculated that the appearance of LGR5 splice variants was related to the cell cycle. We analysed the expression of LGR5 in vitro using several CRC cell lines as shown in Figure 3A. We cultured Lovo without serum for 36 h to arrest the cell cycle and collected cells at each fixed time after adding serum. The schema of the experiment is illustrated in Figure 3B. The mRNA expression of LGR5 and CDKN1A (encodes p21, also known as cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor1), which regulates cell cycle progression at G1 and S phase, was measured in the collected cells. The expression of CDKN1A decreased gradually after peaking at 3 h, whereas LGR5 expression slowly increased after serum addition and peaked after 12 h (Figure 3C). Multiple bands were revealed by gel electrophoresis after 3 and 12 h, suggesting the existence of splice variants (Figure 3D). These findings indicated that the LGR5 splice variants appeared during cell cycle progression. On the other hand, LGR5FL was only expressed during cell cycle arrest. From this result, the cells expressed LGR5FL might have less proliferative ability than the cells that expressed splice variants of LGR5. To investigate the mechanism related to cell proliferation among LGR5 isoforms, we analysed the effect to Wnt signalling influenced by LGR5 isoforms.. Western blotting analysis revealed LGR5FL overexpressed cells were less expressed phosphorylated LRP6, which is one of important factors to activate Wnt signalling (De Lau et al, 2014), than the cells expressed the splice variants of LGR5 (Supplementary Figure S1). Wnt activity assay (TOP-flash) revealed that LGR5FL overexpressed cells had significantly lower activity of Wnt signalling than the cells that overexpressed splice variant of LGR5 (Supplementary Figure S2). Moreover, cell cycle assay showed that the cells overexpressed with LGR5 proceeded cell cycle slowly compared with the cells that overexpressed splice variant of LGR5 (Supplementary Figure S3). These results implied that the cells which expressed LGR5FL had low proliferative capacity, on the other hand, the cells which expressed splice variants of LGR5 had high proliferative capacity.

Figure 3.

The LGR5 splice variants were not expressed during cell cycle arrest.(A) Expression of LGR5 mRNA among LPC. Lovo expressed high levels of LGR5 mRNA. (B) Schematic illustration of the starve test. (C) qRT–PCR of the mRNA extracted from collected Lovo shows that the expression of CDKN1A decreased gradually after the peak at 3 h, whereas LGR5 mRNA slowly increased after serum addition, peaking after 12 h. (D) As a result of electrophoresis of the PCR-purified products, multiple bands were revealed after 3 and 12 h.

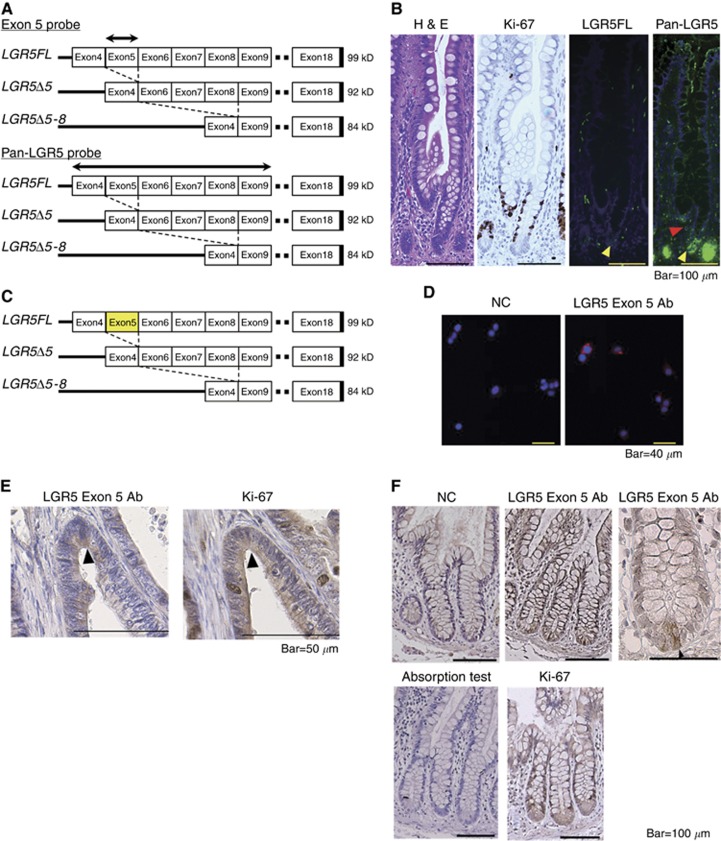

LGR5FL-positive cells were Ki-67-negative

To assess the localisation of LGR5FL mRNA, we designed two kinds of probes for ISH. One was the probe corresponding to exon 5, and the other corresponded to exons 4–9 (Figure 4A). The former could recognise only LGR5FL, but the latter could recognise all kinds of LGR5 isoforms because both splice variants of LGR5 lacked exon 5. Regarding the small intestine, the results of haematoxylin and eosin staining, immunostaining for Ki-67, and ISH of the two probes are shown in Figure 4B. TA cells were Ki-67-positive as expected. The exon 5 probe referred to as LGR5Full was positive in only CBCCs, and the pan-LGR5 probe was positive in both CBCCs and TA cells. Thus, only LGR5FL mRNA was expressed in CBCCs. The results of ISH for other parts of the intestine are shown in Supplementary Figure S4. The anti-LGR5 exon 5 antibody (LGR5 exon 5 Ab) could recognise only LGR5FL, because both LGR5Δ5 and LGR5Δ5–8 lacked exon 5 (Figure 4C). In immunofluorescence analysis, this antibody could detect the LGR5 located on the surface of the Lovo cells (Figure 4D). The results of immunohistochemistry (IHC) for normal intestine are shown in Figure 4E. LGR5 exon 5 Ab was specifically positive on the CBCCs at the crypts of the small intestine and, when it was absorbed, the staining was abolished. TA cells, but not CBCCs, were positive for Ki-67. TA cells are considered to have the ability to proliferate rapidly (Figure 4E). Figure 4F shows the difference in staining between LGR5 exon 5 Ab and Ki-67 in sequential cancer specimens. The tumour cells which expressed LGR5 exon 5 were negative for Ki-67. Thus, it is possible to identify LGR5FL-positive cells using this novel antibody, and the LGR5FL positive were Ki-67 negative. We also validated this antibody for western blotting analysis, but it did not work (data not shown).

Figure 4.

LGR5FL-positive cells were Ki-67-negative.(A) The designed probe for ISH. The exon 5 probe recognised only LGR5FL-positive cells. On the other hand, pan-LGR5 probe corresponding to exons 4–9 recognised all isoforms of LGR5. (B) H&E stain, immunostaining of Ki-67, and ISH for LGR5 isoforms on the sequential intestine specimen. TA cells were Ki-67-positive. LGR5FL was found only in CBCCs (yellow arrow head), and pan-LGR5 probe was positive in CBCCs and TA cells (red arrow head). (C) The designation of the antibody combining exon 5 of LGR5. This antibody could recognise only LGR5FL because both LGR5Δ5 and LGR5Δ5–8 lacked exon5. (D) Immunofluorescent analysis of Lovo. The LGR5 exon 5 Ab could detect LGR5 located on the surface of the CRC cell line. (E) Immunohistochemistry for normal intestine showed that LGR5 exon 5 Ab was specifically positive on the CBCCs at the crypts of the small intestine. In an absorption test, the staining of LGR5 exon 5 Ab was abolished. Ki-67 antibodies yielded positive staining in TA cells. (F) Immunohistochemistry of the sequential section of CRC sample. LGR5 exon 5 Ab-positive cells (arrow head) were negative for Ki-67.

LGR5FL-positive cell population increased after chemotherapy

Many kinds of drugs used for chemotherapy in CRC target tumour cells with an ability to rapidly proliferate. Therefore, CSCs, which are reported to have a low ability to proliferate, remain and can cause regrowth after chemotherapy. Antitumour drugs are generally effective to rapidly proliferative cells. As LGR5FL-positive cells were not positive for Ki-67, which expressed during cell proliferative phase, we speculated that these cells could have chemoresistant character. To examine the effect of chemotherapy LGR5FL-positive cells, we extracted the CRC patients who underwent surgical resection of the tumour following chemotherapy. We performed IHC on the biopsy specimen taken before chemotherapy as the pre-chemotherapy sample and on the surgical specimen as the post-chemotherapy sample. Oxaliplatin, 5-FU were used as antitumour drug for all patients and several patients were administered cetsuximab. IHC of tumour regression grade (TRG) 4 (Rubbia-Brandt et al, 2007) and TRG 3 specimens are shown in Figures 5A and B. Seven cases showed that the ratio of LGR5FL-positive cells in increased post-chemotherapy compared with the ratio prechemotherapy (Figure 5C). We performed IHC for the liver metastasis resected without taking chemotherapy or after chemotherapy. LGR5FL-positive cells were significantly increased in the specimen taken chemotherapy than the specimen without taking chemotherapy (Supplementary Figure S5). Thus, LGR5FL-positive cells seem to be resistant to chemotherapy. To make further analysis of chemresistant ability of LGR5 isoforms, we performed MTT assay using 5-FU. As shown in Supplementary Figure S6, LGR5FL overexpressed cells were more resistant to 5-FU. Similar result was obtained under the stimulation of Wnt3A and RSPO1. Interestingly, adding anti-LGR5 exon 5 Ab attenuated this chemoresitant ability of LGR5FL overexpressed cells. These implied that LGR5FL-overexpressed cells have stronger chemorsistant ability than splice variants of LGR5 in a steady state. However, blocking LGR5 exon 5 could attenuate the chemoresistant ability.

Figure 5.

Ratio of LGR5FL cells increased after chemotherapy.(A and B) Immunohistochemistry of LGR5 exon 5 Ab against chemotherapy effect grade 1a and 2, respectively. (C) Transition of the ratio of LGR5-positive cells in 7 cases of chemotherapy.

Discussion

LGR5 is a receptor belonging to a subgroup of eight LGRs within the superfamily of rhodopsin GPCRs. The distinctive feature of the LGR family is the large extracellular domain composed of tandem arrays of LRR units (Kajava, 1998). The LGR family is divided into three groups: class A, class B, and class C (Van Hiel et al, 2012). Class A consists of LGR1, the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor; LGR2, the luteinising hormone receptor; and LGR3, the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR). Class B includes LGR4, LGR5, and LGR6, which are receptors for RSPOs (De Lau et al, 2014). Class C contains LGR7 and LGR8, which are characterised by the existence of an LDLa motif in the extracellular domain (Hsu et al, 2000). The ligands of LGR7 and LGR8 are relaxin and insulin-like peptide 3, respectively, and cause the production of cAMP (Hsu et al, 2002; Kumagai et al, 2002).

Alternative splicing is a common phenomenon in the LGR family of receptors. All of the class A and class C LGR family members are reported to have splice variants (Apaja et al, 2006; Scott et al, 2006). Alternative splicing variants and the mutant forms of GPCRs are known to inhibit the wild-type isoform (Nakamura et al, 2004; Apaja et al, 2006). In a mouse model, the secreted LGR7 splice variant inhibits the function of wild-type LGR7 via its extracellular interaction with the full-length receptor without modulating its cell surface expression (Scott et al, 2006). In human fetal membrane, three kinds of LGR7 splice variants decrease the ability of wild-type LGR7 to homodimerise, attenuating its function (Kern et al, 2008). Moreover, the structural alteration of the extracellular domain of LGR8 is caused by the mutation results in the inability of the cell to express the receptor on its surface (Bogatcheva et al, 2007). Two kinds of LGR5 splice variants were also reported, and the low expression of the splice variants deficient in exon 5 was relative to the poor prognosis in soft-tissue sarcoma (Rot et al, 2011). However, the biological significance of the LGR5 splice variants is unclear, and their existence was unknown in CRC.

CSCs is one of the most important theories in CRC, as it suggests a subset of cancer cells that possess stem cell properties and have an important role in tumour initiation, metastasis, recurrence, and resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy (Reya et al, 2001; Iwahashi et al, 2013). LGR5 was indicated to be one of the functional CSC markers, and many studies have demonstrated the higher expression of LGR5 in CRC than in normal tissue (Aguilera et al, 2011; Al-Kharusi et al, 2013). However, these studies did not consider the presence of a splice variant of LGR5.

In this report, we showed that the phosphorylation of LRP6, which was a key factor for activation of Wnt signalling, was lower in the cells overexpressed with LGR5FL than splice variants. It is reported that activation of Wnt signalling increased the expression of Ki-67 (Inoue et al, 2006). Low activation of Wnt signalling of LGR5FL-overexpressed cells might be one of the reasons that LGR5FL-positive cells were negative of Ki-67. Moreover, only LGR5FL expressed in CBCCs and splice variants expressed TA cells. As CBCCs were thought to be intestinal stem cell and TA cells proliferates aggressively, these results imply that LGR5FL might be more important factor for maintaining dormancy, and splice variants of LGR5 might get proliferative ability. Typically, high-proliferative cells are more responsive to antitumour drug compared with the cells, which proliferate slowly (Dominguez-Brauer et al, 2015). Accordingly, it is speculated that LGR5FL-positive cells have higher chemoresistant ability than the LGR5 splice variants positive cells. IHC using our novel antibody, which detected only LG5FL-positive cells showed increasing population of LGR5FL-positive cells after chemotherapy and this result is consistent with the non-proliferative activity of LGR5FL-positive cells.

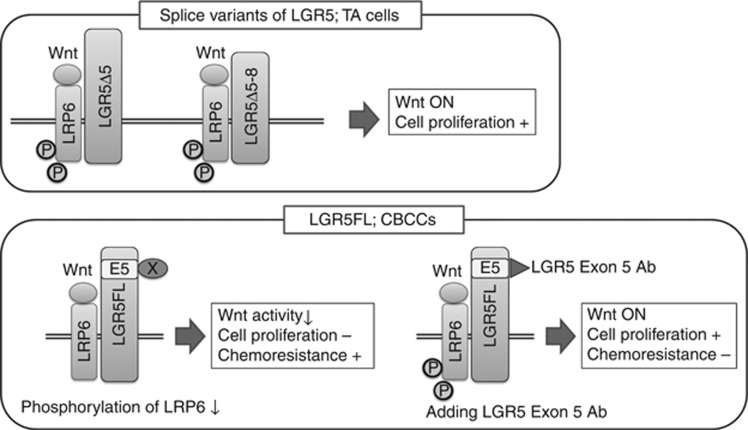

On the basis of the above observation, LGR5FL-positive cells have two features, one is low proliferative activity and the other is chemoresistant. The result of proliferation assay with 5-FU and LGR5 exon 5 Ab showed adding LGR5 exon5 Ab attenuate the ability of chemoresistant. This suggests that blocking LGR5 exon 5 impairs the dormancy of LGR5FL-positive cells and gives the ability of proliferation. As a result, the sensitivity to anti-tumour drug could be increased. Accordingly, although we proved a piece of evidence, there seem to be a potential possibility that LGR5 exon 5 Ab could be promising new drug to CRC. From these results, we proposed the concept which classifies LGR5. The cells that express splice variants of LGR5 present at TA cells and have rapid proliferative ability. On the other hand, LGR5FL-positive cells exist at CBCCs and have relatively dormant by the unknown effect of substance X, which binds the part of LGR5 exon 5 and attenuates phosphorylation of LRP6. Blocking this binding by LGR5 exon5 Ab, LGR5FL-positive cells could activate Wnt signalling and start proliferation and reduce the chemoresitant character as a result (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The speculated concept of the functional difference among LGR5 isoforms.Splice variants of LGR5 expressed at TA cells which proliferate rapidly. LGR5FL expressed specifically at CBCCs. In normal status, unknown substance X affects LGR5 exon 5 and phosphorylation of LRP6 is attenuated. Blocking the binding of substance X by LGR5 exon 5 Ab cause activation of Wnt signalling by LRP6 phosphorylation and the cells get ability of proliferation. As a result, the cells become sensitive to antitumour drug.

There were four limitations of this study. First, anti-LGR5 exon 5 Ab was a polyclonal antibody and its intensity was not enough, although it could specifically detect LGR5FL-positive cells. Second, the number of neoadjuvant chemotherapy cases was small. One reason is that conversion to surgical resection of the tumour after chemotherapy is not common in CRC. An analysis of the differences among LGR5 isoforms using a monoclonal antibody against LGR5 exon 5 seems to be necessary. Third, the evidence was not enough to indicate the link between intestinal stem cell cycle and LGR5 isoforms. Creating a suitable animal model is needed to investigate this point. Finally, we did not analyse the splicing mechanism that arose the splicing variants of LGR5. It is reported that SON had a critical role in regulation of splicing in human embryonic stem cells (Lu et al, 2013) and PHF5A was an important regulator of cancer-specific RNA splicing in glioma stem cell (Hubert et al, 2013). Further analysis of spiliceosome system of LGR5 is needed.

In conclusion, we found LGR5 splice variants in colon cancer. Only LGR5FL expressed CBCC among the isoforms of LGR5- and LGR5FL-positive cells have the possibility to resist antitumour drug owing to its low ability of cell proliferation. LGR5FL-positive cells are worthy to pay attention in studying colorectal cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by MEXT KAKENHI Grant Number 24689054 to N.J.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aguilera C, Nakagawa K, Sancho R, Chakraborty A, Hendrich B, Behrens A (2011) c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation antagonises recruitment of the Mbd3/NuRD repressor complex. Nature 469: 231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kharusi MR, Smartt HJ, Greenhough A, Collard TJ, Emery ED, Williams AC, Paraskeva C (2013) LGR5 promotes survival in human colorectal adenoma cells and is upregulated by PGE2: implications for targeting adenoma stem cells with NSAIDs. Carcinogenesis 34: 1150–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apaja PM, Tuusa JT, Pietila EM, Rajaniemi HJ, Petaja-Repo UE (2006) Luteinizing hormone receptor ectodomain splice variant misroutes the full-length receptor into a subcompartment of the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Biol Cell 17: 2243–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N (2014) Adult intestinal stem cells: critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15: 19–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Ridgway RA, Van Es JH, Van De Wetering M, Begthel H, Van Den Born M, Danenberg E, Clarke AR, Sansom OJ, Clevers H (2009) Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature 457: 608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, Van Den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, Clevers H (2007) Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449: 1003–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchmeier W (2011) Stem cells: orphan receptors find a home. Nature 476: 287–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogatcheva NV, Ferlin A, Feng S, Truong A, Gianesello L, Foresta C, Agoulnik AI (2007) T222P mutation of the insulin-like 3 hormone receptor LGR8 is associated with testicular maldescent and hinders receptor expression on the cell surface membrane. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E138–E144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Zhang X, Li WM, Ji YQ, Cao HZ, Zheng P (2014) Prognostic value of LGR5 in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9: e107013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lau W, Barker N, Low TY, Koo BK, Li VS, Teunissen H, Kujala P, Haegebarth A, Peters PJ, Van De Wetering M, Stange DE, Van Es JE, Guardavaccaro D, Schasfoort RB, Mohri Y, Nishimori K, Mohammed S, Heck AJ, Clevers H (2011) Lgr5 homologues associate with Wnt receptors and mediate R-spondin signalling. Nature 476: 293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lau W, Peng WC, Gros P, Clevers H (2014) The R-spondin/Lgr5/Rnf43 module: regulator of Wnt signal strength. Genes Dev 28: 305–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Brauer C, Thu KL, Mason JM, Blaser H, Bray MR, Mak TW (2015) Targeting Mitosis in Cancer: Emerging Strategies. Mol Cell 60: 524–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada N, Tamai Y, Ishikawa T, Sauer B, Takaku K, Oshima M, Taketo MM (1999) Intestinal polyposis in mice with a dominant stable mutation of the beta-catenin gene. EMBO J 18: 5931–5942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SY, Kudo M, Chen T, Nakabayashi K, Bhalla A, Van Der Spek PJ, Van Duin M, Hsueh AJ (2000) The three subfamilies of leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptors (LGR): identification of LGR6 and LGR7 and the signaling mechanism for LGR7. Mol Endocrinol 14: 1257–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SY, Nakabayashi K, Nishi S, Kumagai J, Kudo M, Sherwood OD, Hsueh AJ (2002) Activation of orphan receptors by the hormone relaxin. Science 295: 671–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert CG, Bradley RK, Ding Y, Toledo CM, Herman J, Skutt-Kakaria K, Girard EJ, Davison J, Berndt J, Corrin P, Hardcastle J, Basom R, Delrow JJ, Webb T, Pollard SM, Lee J, Olson JM, Paddison PJ (2013) Genome-wide RNAi screens in human brain tumor isolates reveal a novel viability requirement for PHF5A. Genes Dev 27: 1032–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Kagawa T, Fukushima M, Shimizu T, Yoshinaga Y, Takada S, Tanihara H, Taga T (2006) Activation of canonical Wnt pathway promotes proliferation of retinal stem cells derived from adult mouse ciliary margin. Stem Cells 24: 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwahashi S, Utsunomiya T, Shimada M, Saito Y, Morine Y, Imura S, Ikemoto T, Mori H, Hanaoka J, Bando Y (2013) High expression of cancer stem cell markers in cholangiolocellular carcinoma. Surg Today 43: 654–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajava AV (1998) Structural diversity of leucine-rich repeat proteins. J Mol Biol 277: 519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper K, Prasetyanti PR, De Lau W, Rodermond H, Clevers H, Medema JP (2012) Monoclonal antibodies against Lgr5 identify human colorectal cancer stem cells. Stem Cells 30: 2378–2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern A, Hubbard D, Amano A, Bryant-Greenwood GD (2008) Cloning, expression, and functional characterization of relaxin receptor (leucine-rich repeat-containing g protein-coupled receptor 7) splice variants from human fetal membranes. Endocrinology 149: 1277–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo BK, Clevers H (2014) Stem cells marked by the R-spondin receptor LGR5. Gastroenterology 147: 289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai J, Hsu SY, Matsumi H, Roh JS, Fu P, Wade JD, Bathgate RA, Hsueh AJ (2002) INSL3/Leydig insulin-like peptide activates the LGR8 receptor important in testis descent. J Biol Chem 277: 31283–31286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Goke J, Sachs F, Jacques PE, Liang H, Feng B, Bourque G, Bubulya PA, Ng HH (2013) SON connects the splicing-regulatory network with pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 15: 1141–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlos-Suarez A, Barriga FM, Jung P, Iglesias M, Cespedes MV, Rossell D, Sevillano M, Hernando-Momblona X, Da Silva-Diz V, Munoz P, Clevers H, Sancho E, Mangues R, Batlle E (2011) The intestinal stem cell signature identifies colorectal cancer stem cells and predicts disease relapse. Cell Stem Cell 8: 511–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser AR, Pitot HC, Dove WF (1990) A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science 247: 322–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Yamashita S, Omori Y, Minegishi T (2004) A splice variant of the human luteinizing hormone (LH) receptor modulates the expression of wild-type human LH receptor. Mol Endocrinol 18: 1461–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T, Clevers H (2005) Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature 434: 843–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL (2001) Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 414: 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rot S, Taubert H, Bache M, Greither T, Wurl P, Eckert AW, Schubert J, Vordermark D, Kappler M (2011) A novel splice variant of the stem cell marker LGR5/GPR49 is correlated with the risk of tumor-related death in soft-tissue sarcoma patients. BMC Cancer 11: 429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubbia-Brandt L, Giostra E, Brezault C, Roth AD, Andres A, Audard V, Sartoretti P, Dousset B, Majno PE, Soubrane O, Chaussade S, Mentha G, Terris B (2007) Importance of histological tumor response assessment in predicting the outcome in patients with colorectal liver metastases treated with neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by liver surgery. Ann Oncol 18: 299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, Van De Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, Van Es JH, Abo A, Kujala P, Peters PJ, Clevers H (2009) Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459: 262–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepers AG, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, Van Den Born M, Van Es JH, Van De Wetering M, Clevers H (2012) Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science 337: 730–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DJ, Layfield S, Yan Y, Sudo S, Hsueh AJ, Tregear GW, Bathgate RA (2006) Characterization of novel splice variants of LGR7 and LGR8 reveals that receptor signaling is mediated by their unique low density lipoprotein class A modules. J Biol Chem 281: 34942–34954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su LK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Preisinger AC, Moser AR, Luongo C, Gould KA, Dove WF (1992) Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science 256: 668–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Ishii H, Nishida N, Takemasa I, Mizushima T, Ikeda M, Yokobori T, Mimori K, Yamamoto H, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, Mori M (2011) Significance of Lgr5(+ve) cancer stem cells in the colon and rectum. Ann Surg Oncol 18: 1166–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanese K, Fukuma M, Yamada T, Mori T, Yoshikawa T, Watanabe W, Ishiko A, Amagai M, Nishikawa T, Sakamoto M (2008) G-protein-coupled receptor GPR49 is up-regulated in basal cell carcinoma and promotes cell proliferation and tumor formation. Am J Pathol 173: 835–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hiel MB, Vandersmissen HP, Van Loy T, Vanden Broeck J (2012) An evolutionary comparison of leucine-rich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptors reveals a novel LGR subtype. Peptides 34: 193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ (2008) Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat Rev Cancer 8: 755–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H, Kondo M, Nakamori S, Nagano H, Wakasa K, Sugita Y, Chang-De J, Kobayashi S, Damdinsuren B, Dono K, Umeshita K, Sekimoto M, Sakon M, Matsuura N, Monden M (2003. a) JTE-522, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, is an effective chemopreventive agent against rat experimental liver fibrosis1. Gastroenterology 125: 556–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Sakamoto M, Fujii G, Tsuiji H, Kenetaka K, Asaka M, Hirohashi S (2003. b) Overexpression of orphan G-protein-coupled receptor, Gpr49, in human hepatocellular carcinomas with beta-catenin mutations. Hepatology 37: 528–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.