Abstract

Pressures to contain health care costs, personalize patient care, use big data, and to enhance health care quality have highlighted the need for integration of evidence at the point of care. The application of evidence-based medicine (EBM) has great promise in the era of electronic health records (EHRs) and health technology. The most successful integration of evidence into EHRs has been complex decision tools that trigger at a critical point of the clinical visit and include patient specific recommendations. The objective of this viewpoint paper is to investigate why the incorporation of complex CDS tools into the EMR is equally complex and continues to challenge health service researchers and implementation scientists. Poor adoption and sustainability of EBM guidelines and CDS tools at the point of care have persisted and continue to document low rates of usage. The barriers cited by physicians include efficiency, perception of usefulness, information content, user interface, and over-triggering. Building on the traditional EHR implementation frameworks, we review keys strategies for successful CDSs: (1) the quality of the evidence, (2) the potential to reduce unnecessary care, (3) ease of integrating evidence at the point of care, (4) the evidence’s consistency with clinician perceptions and preferences, (5) incorporating bundled sets or automated documentation, and (6) shared decision making tools. As EHRs become commonplace and insurers demand higher quality and evidence-based care, better methods for integrating evidence into everyday care are warranted. We have outlined basic criteria that should be considered before attempting to integrate evidenced-based decision support tools into the EHR.

Keywords: clinical decision support tools, framework, implementation

Introduction

Field of Evidence-Based Medicine

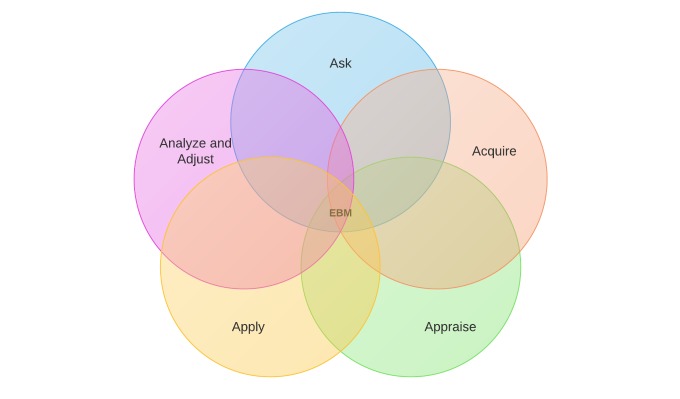

Pressures to contain health care costs, personalize patient care, use of big data, and enhance health care quality have highlighted the need for integration of evidence at the point of care [1-5]. In the field of evidence-based medicine (EBM), we talk about the evidence cycle (Figure 1 shows this) [6]. The EBM cycle starts with a question (ask), then accessing the evidence (acquire), appraising the evidence, applying the evidence to care for our patients, and analyzing and adjusting [7]. The application step is where researchers and policy makers have struggled with implementation and often failed. Furthermore, the constant evolving evidence-based guidelines, clinical prediction rules (CPRs), and comparative effectiveness results makes it challenging for providers to apply the latest evidence at the point of care. But the direct application of EBM has great promise in the era of electronic health records (EHRs) and health technology.

Figure 1.

Five steps of evidence-based practice. Evidence-based medicine: EBM.

With the onset of Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act and Meaningful Use initiatives in 2009, researchers have been hopeful that health technology will be the solution to bringing EBM to the point of care. Substantial investments of funding, intellect, and energy have yielded an array of EHRs and electronic clinical decision support (CDS) tools to improve patients’ quality of care and reduce inappropriate use of critical resources.

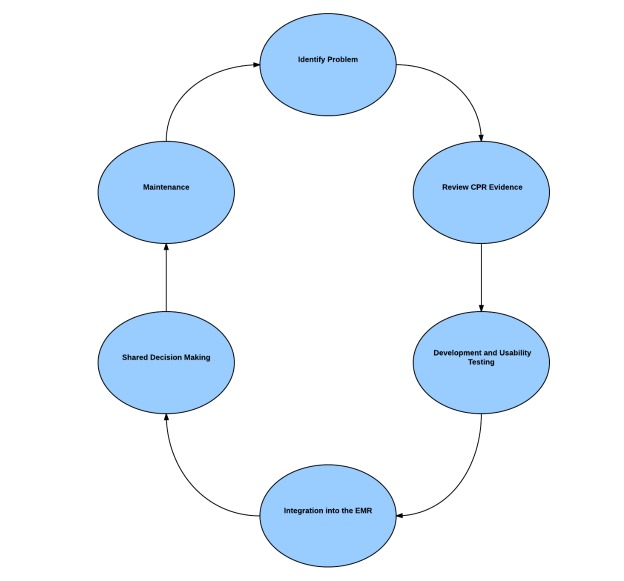

The most successful integration of evidence into EHRs has been complex decision tools that trigger at a critical point of the clinical visit and include patient specific recommendations. In contrast, most of the CDS tools being launched are uni-dimensional and not incorporated into the physicians’ workflow. For the purpose of this article, we have designated these forms of evidence integration as “flat reminders”: one-dimensional alerts that are typically triggered by one or two EHR components such as an element of patient history [8-11]. Examples include, flu-shot reminders at annual visits or reminders for colon-cancer screening triggered by patients’ age (Figure 2 shows this). These flat CDS tools unlike complex CDS rarely include patient-specific medical information, are not integrated into the providers’ clinical workflow, do not include tools to support workflow (bundled order sets or documentation corresponding to the tool), or inclusive of patient-centered decision-making tools [12-14].

Figure 2.

Flat versus dynamic clinical decision support tools. PCP: primary care provider.

Complex, multidimensional forms of CDS are patient-specific, provide specific recommendations for rapid frontline decision making, and therefore have had a greater impact on patient outcomes and resource utilization. CPRs are forms of complex CDS. Based on real-time patient data points such as medical history, physical examination, and laboratory data, CPRs are EBM based algorithms that are able to personalize the patient’s diagnosis, prognosis, and likely response to treatment [6]. CPRs weigh patient data and generate a composite score to stratify patients’ risk of disease onset, disease progression, or outcome events. Physicians find these tools more useful, compared to the flat reminders, when decision making is complex, the clinical stakes are high, or cost savings can be achieved without compromising patient care [6]. Adoption of CPRs have been problematic in that applying complex algorithms at the point of care takes additional time, providers’ forget to apply the rule, and they don’t document the usage.

Incorporating complex CDS tools, such as CPRs, into an EHR holds great promise for finally realizing their potential by standardizing their application, reinforcing their application, and documentation. The caveat is that incorporation of complex CDS tools into the EMR is equally complex and continues to challenge health service researchers and implementation scientists. Poor adoption and sustainability of CDS tools at the point of care has persisted and continues to have low rates of usage [15-18]. The barriers cited by physicians include efficiency, perception of usefulness, information content, user interface, and over-triggering [19,20].

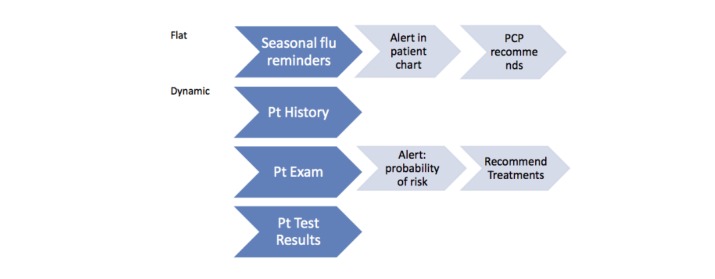

Over the past five years, our research team has been working to improve the integration and adoption of complex CDS tools. Similar to the EBM cycle, we see CDS integration as a step wise process of: identifying a clinical problem, reviewing the evidence, usability testing of the tool, integration and deployment of the tool into the EHR, incorporation of shared decision making, and continuous monitoring and maintenance for sustained effectiveness (Figure 3 shows this).

Figure 3.

Steps to complex clinical decision support tool integration. CPRs: clinical prediction rules.

Aim of the Study

During our research, we have encountered challenges that have repeatedly emerged. In this paper, we propose strategies to overcome those challenges to the integration of complex CDS in order to improve EHR-embedded CDS tools adoption rates, patient outcomes, and resource utilization [21,22].

Key Considerations for Integrating Evidence-Based Medicine Clinical Decision Support Tools at the Point of Care

Key Strategies for Successful Clinical Decision Support Tools

Building on the traditional EHR implementation frameworks, we review keys strategies for successful CDSs: (1) the quality of the evidence, (2) the potential to reduce unnecessary care, (3) ease of integrating evidence at the point of care, (4) the evidence’s consistency with clinician perceptions and preferences, (5) incorporating bundled sets or automated documentation, and (6) shared decision-making tools.

Quality of the Evidence

The first consideration to successful adoption of CDS tools is assessing the quality of the evidence. This may seem an obvious step, but this critical element is often overlooked, with inaccurate assumptions about evidence and impeding the hoped-for results. Therefore, a formal process of evaluating and grading the evidence of the CDS prior to integration is critical. In order for the CDS tool to have a significant impact on health care outcomes, it must be based on high-quality evidence [20].

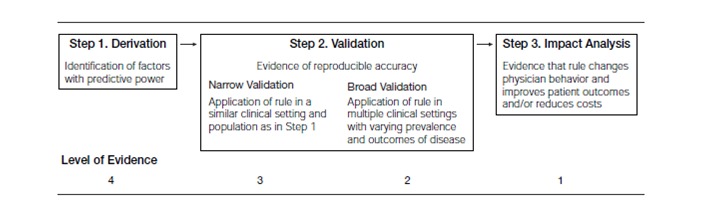

The quality of CPRs is determined by how well they have been validated and tested. CPRs are typically developed in a three-step process: (1) derivation of the rule and creation of a model, usually with a retrospective database; (2) validation of the rule, in which the model is tested, preferably in a prospective fashion in several different sites to demonstrate that it is transportable and stable; and (3) impact analysis, when the rule’s impact on clinical behavior is assessed (Figure 4 shows this) [6]. The further along in the development process, the higher the level or quality of evidence and the more ready it is for integration in the EHR. Only CPRs that have reached a level 1 or 2 of evidence and have shown to have a consistent predictive accuracy should be considered for integration.

Figure 4.

Development and testing of a clinical prediction rule.

Several risk-stratification tools with poor and unclear levels of evidence are currently in wide use, for example, the Modified Early Warning Scoring and the pulmonary embolism rule criteria rule for pulmonary embolism. The rules have been derived, but haven’t shown consistency in prospective validations performed in various clinical settings [23-27].

Potential to Reduce Unnecessary Care

A second consideration we identified as critical is the potential for the evidence to have a significant effect on health care delivery. Historically, CDS and CPR tools have often been introduced in clinical areas plagued by overuse of diagnostic tests or treatments. CPRs aim to accurately identify patients at very low risk who can possibly forgo further testing and those at high risk who can be prioritized for further diagnostic tests or immediate treatment. If the goal of evidence integration is to reduce unnecessary testing or treatment in low risk populations, then estimating how many patients fall into the low risk category will help give an accurate measure of the potential impact of a prediction rule. Our experience has been that estimating this risk will allow you to weigh the potential impact to the work/resources need to build and implement an EHR based CDS tool.

For example, CPRs that guide clinicians through the complex process of risk stratification usually shift the distribution of patients from higher to lower risk. With a CPR such as the strep or pneumonia rule, shifting patients from medium to low risk could reduce orders for antibiotics, which are recommended for patients with medium or high risk; if this constitutes a large proportion of patients, the CPR will have a substantial impact on public health implications (antibiotic resistance) and reduce unnecessary usage of antibiotics.

Ease of Integrating Evidence at Point of Care

A key to both clinician adoption of CDS tools at the point of care and successful integration is how it easy it is to meld the CPR into workflow and how the patient specific data are entered into the tool. Some CDS tools are extremely complex, requiring multiple data points that may not be automatically integrated into the CDS tool and thus require manual entry. In some practice settings, the EHR may not automatically interface with required data such as x-ray results in the emergency departments or rapid point-of-care test results in primary care clinics. Busy clinicians are unlikely to adopt tools that require them to manually derive, obtain, or enter data. Examples of overly complex tools are the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) used in emergency departments to help providers decide to admit patients. The rule has over 20 data elements [28]. Attempts to integrate PSI in emergency room workflow have failed due to poor adoption of the model.

Automatic, Seamless Triggers

A related issue to ease of integration is “triggering” of the tool. To be truly effective, CDS tools need to be an active (automatic) trigger and seamlessly integrated into the flow of care. Providers should not have to activate the decision support, but rather be automatically offered it in the appropriate setting and related to the appropriate patient. Certain phrases or orders and combinations can act as trigger points in the EMR, such as chief complaint or diagnosis. For a trigger to be successful, it needs to trigger accurately (when truly needed) and not be overly sensitive. In our study on using a CPR for pneumonia, entering cough in the chief complaint section was one method of automatically triggering the complex decision support tool. Ideally, decision support is triggered infrequently and is targeted to the specific condition where it can most assist the provider. If there is no method for accurate triggering, the decision tool may not be effective in changing clinicians’ behavior.

Consistency of the Evidence With Provider Perceptions and Preferences

Clinicians are most likely to adopt decision support tools or act on evidence guidelines that align with their predispositions about care. Literature suggests providers’ understand the value of CPRs and state they utilize them in decision making, but CPR adoption rates continue to be low and vary across CPRs [15,16,18,29,30]. We have therefore found it helpful to conduct a needs assessment and survey providers on their beliefs and attitudes to better understand their reception and potential for adopting the rules. Furthermore, it allows us to anticipate and approach the cultural barriers to CPR adoption. For example, the success of two accurate CPRs, the Ottawa Ankle Rule (OAR) and the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI), varied in clinical impact, not based on the quality of evidence, but upon the attitudes the providers’ had on the utility of the CPR in their practice, which hindered the adoption. Dr Ian Stiell derived and validated the OAR CPR to reduce x-ray ordering in emergency rooms among low risk patients presenting with ankle injuries. Implementation of the rule reduced x-ray ordering by over 30% [31]. In contrast, several prediction rules for chest pain risk stratification in emergency rooms have not been widely adopted despite their demonstrated accuracy [32-34]. Physicians in both examples were presented with accurate CPRs, but behaved differently in each situation. In the case of the OAR, most physicians (89.6%) reported using the rule always or most of the time in appropriate circumstances and 42.2% reported basing their decisions to order radiography primarily on the rule [35]. In contrast, physicians using the TIMI rule reported that they looked at the CPR during the triage in 46% of eligible patients, but only one triage decision (1%) was changed by it [33,36]. The OAR CPR in this situation supports their predisposition to confirm their clinical gestalt and empowers them to follow through. In contrast, patients presenting with chest pain may present physicians with a challenging decision that evidence introduction will not help and therefore evidence alone will not change practice patterns. Performing a needs assessment and survey prior to integrating evidence into workflow will potentially uncover these biases and lead to insight on how to overcome those biases.

Incorporating Bundled Sets or Automated Documentation

CPRs that can stratify risk and have a corresponding management plan or diagnostic testing, which can be streamlined and bundled into order sets, will likely have more buy in by physicians, leading to higher usage and therefore larger impact on patient outcomes. The largest incentive we have witnessed through our usability testing is how the CPR and CDS tools can streamline clinical practice instead of impeding and slowing it. By incorporating order sets or automated documentation in progress notes of the EMR and automated documentation in progress notes of the EMR, physicians see the CDS as a facilitator rather than a burden. Therefore, we work to develop CDS tools that offer some incentive to using the tool. In our models, we embedded patient education material in both English and Spanish for patients to take home [21,22,37]. We also developed order sets for recommended antibiotics for patients identified as high risk. Both these aspects were popular with providers.

Shared Decision-Making Tools

The final piece of completing the evidence cycle, which has yet to be sufficiently studied, is the integration of shared decision making when it’s appropriate and as long as it’s based on the best available evidence. Shared decision making (SDM) is becoming an integral part of patient centered care and is seen as a method to improve patient-clinician communication [38,39]. SDM is a process in which the clinician and patient share information about the disease and treatment options and discuss the patient’s preferences to arrive at a decision about a management plan. Decision aids are typically used during the discussions to describe risk of disease and impact of treatment on morbidity and mortality, and have shown to have positive impacts on patient and clinical outcomes [38]. In a systematic review of the literature, it is suggested that patients may benefit from the use of SDM in the emergency department and that SDM is feasible [40]. A randomized controlled trial used SDM tools in patients with chest pain and showed an increase in patients’ knowledge and engagement in decision making and patients decided less frequently to be admitted to the observation unit [41,42]. The combination of CPR with SDM allows for tailored messages around their severity of disease and treatment plans, and through the use of the EMR SDM, reminders, tools, and documentation in clinical visits, CDS is becoming easier.

Discussion

As EHRs become commonplace and insurers demand higher quality and evidence-based care, better methods for integrating evidence into everyday care are warranted. We have outlined basic criteria that should be considered before attempting to integrate evidenced-based decision support tools into the EHR. First and foremost, this process emphasizes a critical appraisal of the quality of the evidence behind the decision support. Second, CDS tools should be evaluated for their ability to perform and impact clinical care through assessments of providers’ perception of utility. Finally, usability testing and integration into workflow need to be thoroughly evaluated prior to attempts to integrate evidence. Evaluation of the evidence and usability testing, however, are often lacking in research design, implementation methodology, and training of researchers in this area. If the federal government, EHR vendors, or health care institutions do not support research in these areas, the integration of successful CDS tools will continue to lag in creating change in patient outcomes. At this critical juncture of widespread EHRs and pressure to bend the cost curve, incentives to help industry, government, and academic health centers to support these research areas is urgent.

Abbreviations

- CDS

clinical decision support

- CPRs

clinical prediction rules

- EBM

evidence-based medicine

- EHRs

electronic health records

- OAR

Ottawa Ankle Rule

- PSI

Pneumonia Severity Index

- SDM

shared decision making

- TIMI

Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Blumenthal D. Launching HITECH. N Engl J Med. 2010 Feb 4;362(5):382–385. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0912825.NEJMp0912825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linder JA, Chan Joseph C, Bates David W. Evaluation and treatment of pharyngitis in primary care practice: The difference between guidelines is largely academic. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jul 10;166(13):1374–1379. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.13.1374.166/13/1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medicare and Medicaid Programs. 2006. Jul 10, [2016-03-28]. Electronic health record incentive program--Stage 2. Proposed Rule https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2012/09/04/2012-21050/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-electronic-health-record-incentive-program-stage-2 .

- 4.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Federal Register. 2010. [2016-03-26]. Federal register | electronic health record (EHR) incentive program https://www.federalregister.gov/regulations/0938-AP78/electronic-health-record-ehr-incentive-program-cms-0033-f-

- 5.King J. ONC Data Brief, no. 7. 2012. [2016-03-28]. Physician adoption of electronic health record technology to meet meaningful use objectives https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/onc-data-brief-7-december-2012.pdf .

- 6.McGinn TG, Guyatt G H, Wyer P C, Naylor C D, Stiell I G, Richardson W S. Users' guides to the medical literature: XXII: How to use articles about clinical decision rules. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000 Jul 5;284(1):79–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.1.79.jml90005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sackett DW. Evidence based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fritz D, Ceschi Alessandro, Curkovic Ivanka, Huber Martin, Egbring Marco, Kullak-Ublick Gerd A, Russmann Stefan. Comparative evaluation of three clinical decision support systems: Prospective screening for medication errors in 100 medical inpatients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012 Aug;68(8):1209–1219. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunt DL, Haynes R B, Hanna S E, Smith K. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on physician performance and patient outcomes: A systematic review. JAMA. 1998 Oct 21;280(15):1339–1346. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1339.jrv71066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Randolph AG, Haynes R B, Wyatt J C, Cook D J, Guyatt G H. Users' guides to the medical literature: XVIII. How to use an article evaluating the clinical impact of a computer-based clinical decision support system. JAMA. 1999 Jul 7;282(1):67–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.1.67.jml80003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Overhage JM, Tierney W M, Zhou X H, McDonald C J. A randomized trial of "corollary orders" to prevent errors of omission. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(5):364–375. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1997.0040364. http://jamia.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9292842 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ansari M, Shlipak Michael G, Heidenreich Paul A, Van Ostaeyen Denise, Pohl Elizabeth C, Browner Warren S, Massie Barry M. Improving guideline adherence: A randomized trial evaluating strategies to increase beta-blocker use in heart failure. Circulation. 2003 Jun 10;107(22):2799–2804. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070952.08969.5B. http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12756157 .01.CIR.0000070952.08969.5B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subramanian U, Fihn Stephan D, Weinberger Morris, Plue Laurie, Smith Faye E, Udris Edmunds M, McDonell Mary B, Eckert George J, Temkit M'Hamed, Zhou Xiao-Hua, Chen Leway, Tierney William M. A controlled trial of including symptom data in computer-based care suggestions for managing patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Med. 2004 Mar 15;116(6):375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.11.021.S0002934303008040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tierney WM, Overhage J Marc, Murray Michael D, Harris Lisa E, Zhou Xiao-Hua, Eckert George J, Smith Faye E, Nienaber Nancy, McDonald Clement J, Wolinsky Fredric D. Effects of computerized guidelines for managing heart disease in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003 Dec;18(12):967–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.30635.x. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0884-8734&date=2003&volume=18&issue=12&spage=967 .30635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemens BJ, Holbrook Anne, Tonkin Marita, Mackay Jean A, Weise-Kelly Lorraine, Navarro Tamara, Wilczynski Nancy L, Haynes R Brian, CCDSS Systematic Review Team Computerized clinical decision support systems for drug prescribing and management: A decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6:89. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-89. http://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-6-89 .1748-5908-6-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eccles M, McColl Elaine, Steen Nick, Rousseau Nikki, Grimshaw Jeremy, Parkin David, Purves Ian. Effect of computerised evidence based guidelines on management of asthma and angina in adults in primary care: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002 Oct 26;325(7370):941. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.941. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/12399345 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litvin CB, Ornstein Steven M, Wessell Andrea M, Nemeth Lynne S, Nietert Paul J. Use of an electronic health record clinical decision support tool to improve antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections: The ABX-TRIP study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013 Jun;28(6):810–816. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2267-2. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23117955 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cresswell K, Majeed Azeem, Bates David W, Sheikh Aziz. Computerised decision support systems for healthcare professionals: An interpretative review. Inform Prim Care. 2012;20(2):115–128. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v20i2.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bright TJ, Wong Anthony, Dhurjati Ravi, Bristow Erin, Bastian Lori, Coeytaux Remy R, Samsa Gregory, Hasselblad Vic, Williams John W, Musty Michael D, Wing Liz, Kendrick Amy S, Sanders Gillian D, Lobach David. Effect of clinical decision-support systems: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jul 3;157(1):29–43. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00450.1206700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bates DW, Kuperman Gilad J, Wang Samuel, Gandhi Tejal, Kittler Anne, Volk Lynn, Spurr Cynthia, Khorasani Ramin, Tanasijevic Milenko, Middleton Blackford. Ten commandments for effective clinical decision support: Making the practice of evidence-based medicine a reality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(6):523–530. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1370. http://jamia.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12925543 .M1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li A, Kannry Joseph L, Kushniruk Andre, Chrimes Dillon, McGinn Thomas G, Edonyabo Daniel, Mann Devin M. Integrating usability testing and think-aloud protocol analysis with "near-live" clinical simulations in evaluating clinical decision support. Int J Med Inform. 2012 Nov;81(11):761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.02.009.S1386-5056(12)00041-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mann DM, Kannry Joseph L, Edonyabo Daniel, Li Alice C, Arciniega Jacqueline, Stulman James, Romero Lucas, Wisnivesky Juan, Adler Rhodes, McGinn Thomas G. Rationale, design, and implementation protocol of an electronic health record integrated clinical prediction rule (iCPR) randomized trial in primary care. Implement Sci. 2011;6:109. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-109. http://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-6-109 .1748-5908-6-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Churpek MM, Yuen Trevor C, Edelson Dana P. Risk stratification of hospitalized patients on the wards. Chest. 2013 Jun;143(6):1758–1765. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1605. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23732586 .S0012-3692(13)60409-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyriacos U, Jelsma J, Jordan S. Monitoring vital signs using early warning scoring systems: A review of the literature. J Nurs Manag. 2011 Apr;19(3):311–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.AydoÄŸdu M, TopbaÅŸi SinanoÄŸlu Nazlı, DoÄŸan Nurettin Ozgür, OÄŸuzülgen Ipek Kıvılcım, Demircan Ahmet, Bildik Fikret, Ekim Numan Nadir. Wells score and pulmonary embolism rule out criteria in preventing over investigation of pulmonary embolism in emergency departments. Tuberk Toraks. 2014;62(1):12–21. doi: 10.5578/tt.6493. http://www.tuberktoraks.org/linkout.aspx?pmid=24814073 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bokobza J, Aubry A, Nakle N, Vincent-Cassy C, Pateron D, Devilliers C, Riou B, Ray P, Freund Y. Pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria vs D-dimer testing in low-risk patients for pulmonary embolism: A retrospective study. Am J Emerg Med. 2014 Jun;32(6):609–613. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.03.008.S0735-6757(14)00174-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crichlow A, Cuker Adam, Mills Angela M. Overuse of computed tomography pulmonary angiography in the evaluation of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2012 Nov;19(11):1219–1226. doi: 10.1111/acem.12012. doi: 10.1111/acem.12012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fine MJ, Auble T E, Yealy D M, Hanusa B H, Weissfeld L A, Singer D E, Coley C M, Marrie T J, Kapoor W N. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997 Jan 23;336(4):243–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graham ID, Stiell I G, Laupacis A, O'Connor A M, Wells G A. Emergency physicians' attitudes toward and use of clinical decision rules for radiography. Acad Emerg Med. 1998 Feb;5(2):134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02598.x. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1069-6563&date=1998&volume=5&issue=2&spage=134 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perry JJ, Goindi Reena, Symington Cheryl, Brehaut Jamie, Taljaard Monica, Schneider Sandra, Stiell Ian G. Survey of emergency physicians' requirements for a clinical decision rule for acute respiratory illnesses in three countries. CJEM. 2012 Mar;14(2):83–89. doi: 10.2310/8000.2012.110552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perry J J, Stiell Ian G. Impact of clinical decision rules on clinical care of traumatic injuries to the foot and ankle, knee, cervical spine, and head. Injury. 2006 Dec;37(12):1157–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.07.028.S0020-1383(06)00425-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldman L, Cook E F, Johnson P A, Brand D A, Rouan G W, Lee T H. Prediction of the need for intensive care in patients who come to the emergency departments with acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 1996 Jun 6;334(23):1498–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606063342303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearson SD, Goldman L, Garcia T B, Cook E F, Lee T H. Physician response to a prediction rule for the triage of emergency department patients with chest pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1994 May;9(5):241–247. doi: 10.1007/BF02599648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hess EP, Agarwal Dipti, Chandra Subhash, Murad Mohammed H, Erwin Patricia J, Hollander Judd E, Montori Victor M, Stiell Ian G. Diagnostic accuracy of the TIMI risk score in patients with chest pain in the emergency department: A meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2010 Jul 13;182(10):1039–1044. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.092119. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=20530163 .cmaj.092119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brehaut JC, Stiell Ian G, Visentin Laura, Graham Ian D. Clinical decision rules "in the real world": How a widely disseminated rule is used in everyday practice. Acad Emerg Med. 2005 Oct;12(10):948–956. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.04.024. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1069-6563&date=2005&volume=12&issue=10&spage=948 .j.aem.2005.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pearson MR, Leonard R B. Posterior sternoclavicular dislocation: A case report. J Emerg Med. 1994;12(6):783–787. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(94)90484-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGinn TG, McCullagh Lauren, Kannry Joseph, Knaus Megan, Sofianou Anastasia, Wisnivesky Juan P, Mann Devin M. Efficacy of an evidence-based clinical decision support in primary care practices: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Sep 23;173(17):1584–1591. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8980.1722509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan Susan. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012 Mar 1;366(9):780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elwyn G, Frosch Dominick, Thomson Richard, Joseph-Williams Natalie, Lloyd Amy, Kinnersley Paul, Cording Emma, Tomson Dave, Dodd Carole, Rollnick Stephen, Edwards Adrian, Barry Michael. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 Oct;27(10):1361–1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22618581 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flynn D, Knoedler Meghan A, Hess Erik P, Murad M Hassan, Erwin Patricia J, Montori Victor M, Thomson Richard G. Engaging patients in health care decisions in the emergency department through shared decision-making: A systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2012 Aug;19(8):959–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01414.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hess EP, Knoedler Meghan A, Shah Nilay D, Kline Jeffrey A, Breslin Maggie, Branda Megan E, Pencille Laurie J, Asplin Brent R, Nestler David M, Sadosty Annie T, Stiell Ian G, Ting Henry H, Montori Victor M. The chest pain choice decision aid: A randomized trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012 May;5(3):251–259. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.964791. http://circoutcomes.ahajournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=22496116 .CIRCOUTCOMES.111.964791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pierce MA, Hess Erik P, Kline Jeffrey A, Shah Nilay D, Breslin Maggie, Branda Megan E, Pencille Laurie J, Asplin Brent R, Nestler David M, Sadosty Annie T, Stiell Ian G, Ting Henry H, Montori Victor M. The chest pain choice trial: A pilot randomized trial of a decision aid for patients with chest pain in the emergency department. Trials. 2010;11:57. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-57. http://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1745-6215-11-57 .1745-6215-11-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]