Abstract

Ocean acidification imposes many physiological, energetic, structural and ecological challenges to stony corals. While some corals may increase autotrophy under ocean acidification, another potential mechanism to alleviate some of the adverse effects on their physiology is to increase heterotrophy. We compared the feeding rates of Galaxea fascicularis colonies that have lived their entire lives under ocean acidification conditions at natural carbon dioxide (CO2) seeps with colonies living under present-day CO2 conditions. When provided with the same quantity and composition of zooplankton as food, corals acclimatized to high CO2 showed 2.8 to 4.8 times depressed rates of zooplankton feeding. Results were consistent over four experiments, from two expeditions and both in field and chamber measurements. Unless replenished by other sources, reduced zooplankton uptake in G. fascicularis acclimatized to ocean acidification is likely to entail a shortage of vital nutrients, potentially jeopardizing their health and survival in future oceans.

Corals evolved in oligotrophic waters to be mixotrophs, i.e. both auto- and heterotrophs. Autotrophy is the more studied component of the two nutritional modes. However, heterotrophy is just as important, even though its role in coral health is often ignored or underestimated1. In addition to supplementing the organic carbon supplied by endosymbiotic zooxanthellae living within their tissue2, heterotrophy provides corals with essential micro- and macronutrients that are not attained through autotrophy3. These nutrients, including nitrogen and phosphorus, are needed for tissue growth, zooxanthellae regulation, and reproduction4,5,6,7,8. Corals obtain these nutrients by the uptake of dissolved organic matter9, detrital particulates suspended in the water column10, bacteria11, and zooplankton12. Some species of corals increase their reliance on heterotrophy when under stress due to high turbidity10,13, increased seawater temperatures that lead to the loss of their endosymbionts (coral bleaching)1,14, and short-term exposure to elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations15,16. As environmental stressors from anthropogenic causes continue to increase, heterotrophy may become more relevant in the future to maintain coral health. Here, we explore coral heterotrophy with respect to one of the biggest environmental threats of all, ocean acidification. The term ‘ocean acidification’ describes the shift in seawater carbonate chemistry as anthropogenic CO2 is absorbed by the oceans17. Under ocean acidification, seawater pH and calcium carbonate saturation states are both reduced. The reduced concentration of carbonate ions increases energy demands to maintain rates of calcification and growth, and triggers other physiological and energetic changes18.

The number of studies is limited, but some suggest that coral heterotrophy may reduce the impacts caused by ocean acidification15,16,19. Several laboratory experiments show that adult and juvenile corals can maintain calcification rates with heterotrophy under ocean acidification15,19,20. Other studies found that feeding or nutrient loading did not offset the impacts to coral calcification by increased CO221,22. For example, calcification rates of Porites rus reduced during short-term high CO2 exposure but were unaffected by the provision of food23. It also remains unresolved whether coral heterotrophy may be affected by ocean acidification, and any underlying mechanisms explaining those changes. Previous studies that have investigated the effects of elevated CO2 on coral heterotrophy have shown mixed results. For example, Porites lutea expanded its polyps more in high CO2 waters, perhaps in an attempt to feed more and ameliorate the negative effects of ocean acidification24. Also, the corals Acropora cervicornis and Porites rus displayed increased rates of heterotrophy under elevated CO215,16, mitigating the adverse effects of elevated CO2 on calcification, while Stylophora pistillata had reduced rates under laboratory conditions25.

In this study, we investigated the impacts of ocean acidification on zooplankton capture rates in a coral species known for its voracity in feeding, Galaxea fascicularis. This coral feeds on zooplankton by extending mesenterial filaments through the polyp mouth, capturing particles, and then either ingesting them or digesting them externally, outside the coelenteron26,27. Our study was based on four complementary field and laboratory experiments. They were conducted during two expeditions to fringing reefs in Papua New Guinea where CO2 seeps create natural pH gradients. We compared the morphology, behavior and feeding rates of G. fascicularis colonies grown in seawater with elevated CO2 (pHT [total scale]~7.8, pCO2~760 μatm) against those grown at control CO2 (pHT~8.1, pCO2~420 μatm). We tested the following hypotheses: colonies acclimatized to elevated CO2 (1) have smaller polyps due to energetic constraints for calcification, (2) expand their polyps further, and (3) have increased rates of heterotrophy. We also tested for (4) food selectivity in G. fascicularis as a function of CO2 levels, and (5) whether the neurotransmitter receptor GABAA was involved in the observed changes in the feeding ability of G. fascicularis under ocean acidification.

GABA (gamma-amino butyric acid) is one of many neurotransmitters within the central nervous system of cnidarians that helps regulate circadian rhythms in corals28,29 and modulates feeding responses in the cnidarian Hydra vulgaris30,31,32. Two receptors are associated with the neurotransmitter GABA: GABAA and GABAB. There are multiple binding sites on each receptor with various possible agonists (chemicals that activate a biological response) and antagonists (chemicals that block the action of any agonist), which can attach to the binding site. The functioning of the GABA receptor GABAA is of particular interest within ocean acidification research and has been linked to interference of neurotransmitter functioning in fish, mollusks, and other marine organisms33,34. Sensory and behavioral impairment of these organisms can effectively be reversed with one of the antagonist to the GABAA receptor, gabazine, although it has never been tested in corals. G. fascicularis colonies under ocean acidification were treated with gabazine to determine its possible influences on heterotrophy.

G. fascicularis fragments used in this study have been exposed to high CO2 conditions their entire life; therefore, all observations of feeding behavior of G. fascicularis reflect heterotrophy of corals with life-long acclimation to ocean acidification.

Results

Feeding rates

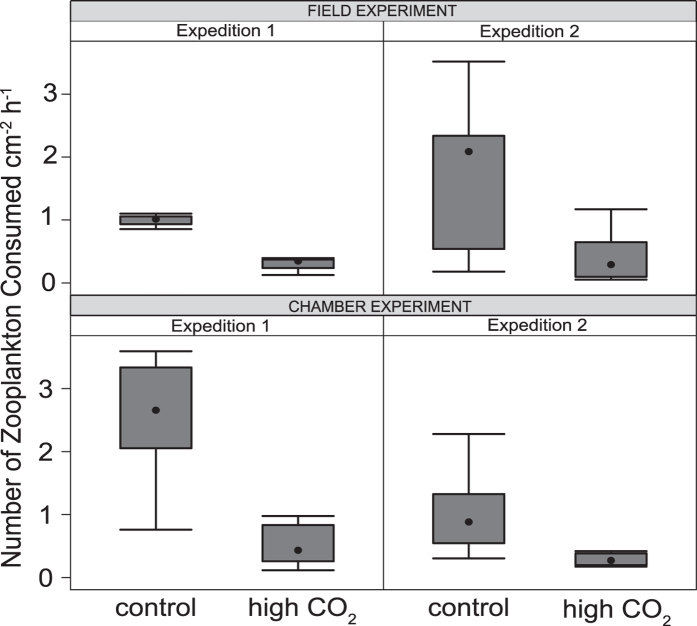

G. fascicularis colonies acclimatized to high CO2 conditions (average pHT of 7.8) consumed less zooplankton compared to colonies under control conditions (pHT 8.1; Fig. 1). This result was consistent for all experiments across methods and expeditions. The difference in the total number of zooplankton consumed per surface area was statistically different between CO2 levels, but not between methods (i.e. field versus chamber), or between expeditions (Table 1). The interaction between method and expedition had a significant influence on the total number of zooplankton consumed, although there was no difference for the main effect variables of method and expedition (Table 1).

Figure 1. Rates of heterotrophy in the coral Galaxea fascicularis in all experiments from two methods (field and chamber), two expeditions, and two CO2 levels (control and high CO2).

Table 1. Results of a generalized linear model regression of coral feeding rates in response to method, expedition, CO2, and their interaction terms.

| Factors and Interactions | F(df,df) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Method | F(1,61) = 0.46 | 0.50 |

| Expedition | F(1,60) = 1.9 | 0.18 |

| CO2 | F(1,62) = 51.9 | <0.001* |

| Method: Expedition | F(1,57) = 9.4 | 0.003* |

| Method: CO2 | F(1,59) = 0.39 | 0.53 |

| Expedition: CO2 | F(1,58) = 0.25 | 0.62 |

| Method: Expedition: CO2 | F(1,56) = 0.48 | 0.49 |

Following the observation of reduced feeding rates during the first expedition, in the second expedition we assessed whether the reduced heterotrophy was caused by CO2-induced impairment of neurotransmitters. The addition of gabazine during the chamber experiment from expedition 2 had no significant impact on the feeding rates (one-way ANOVA: F(2,22) = 0.51; P = 0.48). Thus, heterotrophy rates under high CO2 were not restored by the treatment with gabazine, the GABAA receptor antagonist.

Composition of consumed food and selective feeding

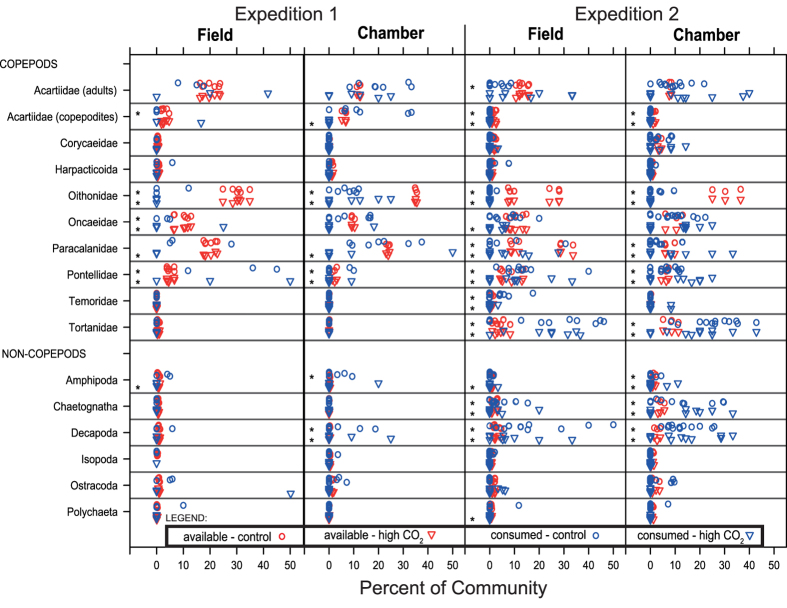

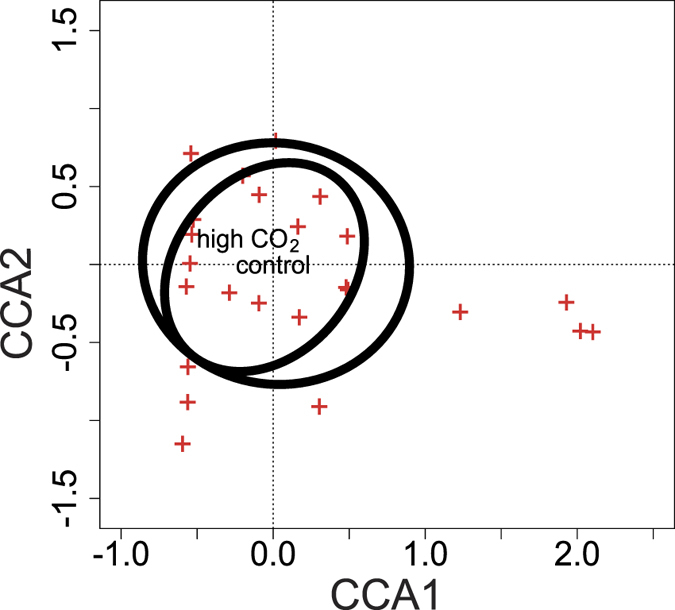

Although the total number of zooplankton consumed was different between CO2 levels, the types of zooplankton consumed by G. fascicularis were not different between CO2 levels. Taxonomic richness of the zooplankton prey consumed was not different between CO2 levels (three-way ANOVA: F(1,13) = 2.74; P = 0.10), although it was higher in the chamber experiments compared to the field experiments (F(1,15) = 20.2; P < 0.001), and higher in expedition 2 compared to expedition 1 (F(1,15) = 8.17; P = 0.006). Multivariate community analyses on the prey consumed by corals supported these results and indicated that the zooplankton community consumed was also not different between CO2 levels (three-way ANOVA: F(1,56) = 1.45; P = 0.14; Fig. 2; supplementary information Figure S2), although differed between methods (F(1,56) = 2.86; P = 0.003), expeditions (F(1,56) = 14.5; P = 0.001), and the interaction across the two variables (F(1,56) = 2.95; P = 0.005).

Figure 2. Community analysis of zooplankton consumed under contrasting CO2 regimes.

Ordination plot from a canonical correlation analysis (CCA).

The types of prey identified in the coelenteron of dissected corals had much lower taxonomic richness than the plankton available in the water column: corals contained only 11–17 zooplankton taxa of the 26–33 taxa present in the water. Corals preferentially ingested some zooplankton taxa, including Pontellidae and Paracalanidae copepods, decapods, amphipods, and chaetognaths, whereas Oithonidae copepods that are abundant in the water column were scarce in the food consumed (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. The percent composition of the top available and consumed zooplankton taxa is shown for both expeditions, methods, and between CO2 levels.

Plots for the 16 most commonly consumed zooplankton taxa compare the percent of each taxon consumed by the coral represented in the coelonteron (blue symbols) to the percent of the community that each zooplankton is available in the water column (red symbols). Each zooplankton taxon has two rows, with the top row (circles) representing the control site and the bottom row (triangles) representing the elevated CO2 site. Each panel represents a separate experiment (two expeditions and two methods). Asterisks indicate a significant difference between the percent consumed and percent available in the water column (t-tests, p-value < 0.05).

Results from logistic regressions that examined the effects of elevated CO2, expedition, and method, on the probability that each zooplankton taxon may be consumed indicated slight variation in the rates of consumption of the various taxa in response to these factors (Table 2). There was no difference in selectivity between high CO2 and control corals for the most available and most frequently consumed zooplankton taxa. However, the rare Acartidae copepodites, Harpacticoida, Isopoda, Ostracoda, and Polychaeta appeared preferentially consumed at the control CO2 level. These taxa all represent a small proportion of the plankton available and consumed (<2%). Furthermore, consumption rates of several zooplankton taxa differed between expeditions and methods. For example, Tortanidae copepods were rarely consumed during the first expedition, and yet during the second expedition they constituted on average 30.2% of the coral diet in the field experiment and 22.6% in the chamber experiment. Similarly, uptake rates of decapods and chaetognaths were relatively high during the second expedition.

Table 2. Probability for each of the 16 most common zooplankton taxon to be consumed by Galaxea fascicularis, as a function of CO2 (seep vs. control), expedition (one vs. two), method (field vs. chamber), and the interactions of these parameters (three-way interactions were non-significant for all taxa and are not shown).

| Taxon | CO2 | Expedition | Method | CO2: Expedition | CO2: Method | Expedition: Method | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Χ2 | p-value | Χ2 | p-value | Χ2 | p-value | Χ2 | p-value | Χ2 | p-value | Χ2 | p-value | |

| COPEPODS | ||||||||||||

| Acartiidae (adults) | 8.78 | 0.679 | 8.06 | 0.011 | 7.87 | 0.196 | 7.52 | 0.074 | 7.29 | 0.15 | 6.92 | 0.071 |

| Acartiidae (copepodites) | 5.28 | <0.001 | 2.44 | <0.001 | 2.26 | 0.003 | 2.26 | 0.999 | 1.26 | <0.001 | 1.26 | 0.999 |

| Corycaeidae | 2.71 | 0.889 | 2.15 | <0.001 | 1.58 | <0.001 | 1.58 | 1.000 | 1.57 | 0.611 | 1.57 | 0.999 |

| Harpacticoida | 0.81 | <0.001 | 0.81 | 0.907 | 0.63 | 0.001 | 0.63 | 0.999 | 0.63 | 0.999 | 0.60 | 0.169 |

| Oithonidae | 5.01 | 0.464 | 2.98 | <0.001 | 2.54 | <0.001 | 2.27 | 0.008 | 2.11 | 0.034 | 2.08 | 0.441 |

| Oncaeidae | 6.33 | 0.151 | 6.28 | 0.464 | 6 | 0.077 | 6.00 | 0.932 | 6.00 | 0.943 | 5.90 | 0.303 |

| Paracalanidae | 10.1 | 0.585 | 9.46 | 0.047 | 9.29 | 0.324 | 8.27 | 0.142 | 8.23 | 0.654 | 7.93 | 0.179 |

| Pontellidae | 13.9 | 0.614 | 13.6 | 0.199 | 12.6 | 0.029 | 12.4 | 0.412 | 11.9 | 0.110 | 11.6 | 0.217 |

| Temoridae | 2.62 | 0.171 | 2.17 | <0.001 | 2 | 0.025 | 2.00 | 0.999 | 1.47 | <0.001 | 1.47 | 0.999 |

| Tortanidae | 18.4 | 0.989 | 8.70 | <0.001 | 8.37 | 0.096 | 8.38 | 1.000 | 8.03 | 0.083 | 8.03 | 1.000 |

| NON-COPEPODS | ||||||||||||

| Amphipoda | 2.98 | 0.922 | 2.70 | 0.030 | 2.61 | 0.218 | 2.56 | 0.385 | 2.45 | 0.178 | 2.45 | 0.885 |

| Chaetognatha | 8.83 | 0.656 | 6.23 | <0.001 | 4.94 | <0.001 | 4.94 | 0.999 | 4.94 | 0.873 | 4.94 | 0.999 |

| Decapoda | 9.24 | 0.173 | 7.72 | <0.001 | 7.7 | 0.695 | 7.69 | 0.771 | 7.46 | 0.177 | 7.25 | 0.196 |

| Isopoda | 0.35 | <0.001 | 0.34 | 0.203 | 0.34 | 0.390 | 0.34 | 0.999 | 0.34 | 0.999 | 0.26 | 0.545 |

| Ostracoda | 2.23 | 0.002 | 2.22 | 0.574 | 2.22 | 0.766 | 2.06 | 0.013 | 1.74 | <0.001 | 1.45 | <0.001 |

| Polychaeta | 1.41 | <0.001 | 1.41 | 0.841 | 1.25 | 0.042 | 1.25 | 0.999 | 1.25 | 0.999 | 1.14 | 0.082 |

Χ2 (with df = 1 for all parameters) and p-values from the logistic regression analysis are presented, with bold print indicating significances at p < 0.05.

Corallite size and polyp expansion between CO2 levels

No difference was observed in the size of G. fascicularis corallites between colonies originating at the seep and control sites (1-way ANOVA: F(1,62) = 2.7, P = 0.11). Elevated CO2 also had no effect on polyp expansion of G. fascicularis at the seep and control sites, neither in the field nor in the chamber experiments. While coral polyps were not expanded more under elevated CO2 compared to control CO2 levels (4-way ANOVA: F(1,124) = 1.1; P = 0.29), they were expanded significantly more in the field compared to the chamber experiments (F(1,126) = 22.0; P < 0.001), and in expedition 2 compared to expedition 1 (F(1,125) = 12.2; P < 0.001; see supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, corals expanded their polyps more at the end of each experiment compared to the beginning (F(1,123) = 6.3; P = 0.013).

Discussion

The observed effects of ocean acidification on heterotrophy in the stony coral Galaxea fascicularis contradicted our initial hypothesis. We expected corals to ingest more zooplankton under high CO2. Instead, we found that food consumption rates were reduced under elevated CO2, both in the field and in chamber experiments, and during two expeditions. Since the colonies in our high and ambient CO2 treatments had been subjected to life-long exposure to their respective CO2 environments, this study presents the first investigation of heterotrophy in corals that were fully acclimatized to elevated CO2 throughout their entire post-settlement lives.

The taxonomic composition of the zooplankton consumed by G. fascicularis was different compared to the zooplankton community available to the corals. Such selectivity is known for corals12. Selectivity may be indicative of plankton behavior; for example, some zooplankton taxa swim more slowly or clumsily making it easier to capture them, while some taxa have chemical defenses that make them unpalatable to corals35. Whether it is from their own choosing or more from the behavior or chemical defenses of the zooplankton, there was strong selection for certain zooplankton, and this selectivity appeared to be largely unaffected by CO2 treatments, with the exception of only a few uncommon taxa (Table 2).

Selectivity results may be slightly biased towards larger zooplankton taxa since smaller groups digest faster than larger zooplankton36. However, the feeding time in this study was purposely chosen to be one hour so that complete digestion could be avoided. Complete digestion takes hours to days, and even small nauplii are still recognizable after only 60 minutes in the coelenteron12,26,36,37. Furthermore, since the mesh size of the plankton net was 100 μm, the smallest zooplankton types were excluded from the experiment. In fact, most zooplankton consumed were easily identifiable to species level even when partially digested, hence the category ‘unidentified consumed zooplankton’ represented only 13% of the items retrieved from the coelonteron.

G. fascicularis consumed less zooplankton in the high CO2 water despite having the same access to food, the same state of polyp expansion, and the same corallite sizes between CO2 treatments. The reasons for the observed reduction in feeding rates could be many, however our study negated several potential causes. Reduced heterotrophy was not caused by a reduction in corallite size since G. fascicularis corallites were the same size between CO2 levels, even though exposure to elevated CO2 reduces corallite sizes in some other coral species38. For example, the temperate coral Oculina patagonica showed smaller corallites at elevated CO2 due to high energetic costs for calcification; however, after one month of acidic conditions the skeleton completely dissolved and polyp sizes increased when calcification ceased and the resulting free energy was channeled into somatic growth39. With respect to G. fascicularis, it is possible that net calcification rates may change under ocean acidification conditions despite the morphology of the corallites remaining similar for both CO2 levels.

Reduced heterotrophy was also not caused by a difference in polyp expansion, which remained unaffected by ocean acidification for G. fascicularis. In contrast, another study observed that polyps from the coral P. lutea extended further under high CO2 conditions24. During the second expedition, however, G. fascicularis polyps were expanded more, which happened to occur during a new moon compared to the first expedition that had a full moon. Corals are known to feed differently with the lunar cycle, coinciding with lunar effects on zooplankton migration patterns28,40. Also, polyps were expanded more in the field experiments compared to the chamber experiment, probably because the corals were undisturbed in the field.

A deficiency in the functioning of GABAA neurotransmitter receptors in G. fascicularis was also not a likely cause for the observed reduction in heterotrophy. Gabazine plays a role in Hydra vulgaris feeding response31, therefore we expected it to also influence coral feeding behavior of G. fascicularis since both of these cnidarians share similar nervous systems. Despite our predictions, the treatment of G. fascicularis with gabazine yielded no change in coral heterotrophy. The effect of ocean acidification on coral neurotransmitters cannot be completely excluded, however, because different chemicals besides gabazine may bind to the neurotransmitter receptors (e.g. the agonist muscimol and the antagonist bicuculline)32. To thoroughly understand the effect of ocean acidification on neurotransmitters of G. fascicularis, the reactions of other receptor antagonists and agonists to elevated CO2 need to be evaluated.

Additional experiments are needed to reveal the underlying mechanisms responsible for the reduced feeding rates in G. fascicularis. Potential causes or contributors that deserve further study include reduced particle retention, changes in cellular homeostasis of the tentacle cells, reduced nematocyst functioning, altered mucus production, physiological stress that makes them less capable to feed, an increase in autotrophy, and potential changes in plankton behavior, as briefly outlined here. G. fascicularis exerted similar effort to capture zooplankton between CO2 levels by extending their polyps to the same level. That they ingested fewer food particles in ocean acidification conditions may reflect upon the polyps’ ability to capture food. Food retention may be reduced if the functionality of their stinging cells (nematocysts) is disrupted41,42. Nematocyst performance may be vulnerable to changes in pH since the acid-base balance in cells corresponds to the intracellular concentration of free H+ ions. A study on the jellyfish Pelagica noctiluca indicated that the cell homeostasis of nematocysts is profoundly compromised by acidification of the surrounding seawater impairing the cells’ discharge capability43. Although cellular homeostasis in nematocysts may vary between jellyfish and corals, nematocyst functioning may be impaired for corals under ocean acidification and merits further investigation.

Another possible cause for the observed reduced feeding rates could be that the polyps themselves lose their ability to retain food particles. Food particles may be stung or killed, but the mucosal or tentacular action of the polyps may not trap the particles, resulting in the loss of prey items26. Mucus enhances coral heterotrophy44, therefore heterotrophy will likely be vulnerable to any changes in mucus production, but nothing is known about how ocean acidification may affect coral mucus.

It is perceivable that G. fascicularis may also have reduced rates of heterotrophy in response to a reduced energy demand. Elevated CO2 enhances the photosynthetic-derived energy supply in some coral species, and this energy is available to support critical functions like calcification. Coral calcification is generally considered to decline with elevated CO2 levels45, although some studies report parabolic and even positive calcification responses to ocean acidification conditions46,47. However, corals are more nutrient limited than carbon limited in oligotrophic and shallow (high-light) environments2. Furthermore, feeding rates of corals only reach saturation when food concentrations are high, with heterotrophy generally more efficient in oligotrophic habitats48. Considering that G. fascicularis from the CO2 seep sites live in a nutrient-poor and high-light environment, it is highly unlikely that feeding becomes saturated and their need for essential nutrients not attained from photosynthesis would still be prevalent. Therefore, G. fascicularis would likely continue to feed on zooplankton at the CO2 seep sites if they were still capable even under an increased carbon supply from photosynthesis.

Regardless of the underlying mechanisms, reduced heterotrophy under elevated CO2 will have biological impacts on corals. Growth, reproduction, zooxanthellae maintenance49, and other metabolic processes depend on nitrogen, phosphorus, and other essential trace elements, which are exclusively attained through heterotrophy6,50,51,52. We are only starting to understand the long-term impacts of ocean acidification on tissue growth, phototrophy, respiration, heterotrophy, and their energetic interdependencies, in selected species of coral. Many but not all coral species increase their rates of photosynthesis at higher pCO2 levels53. Reduced heterotrophy may also impact coral lipid content and fatty acid composition, since they are co-determined by zooplankton consumption54. Furthermore, lower feeding rates may slow skeletal and tissue growth considering that growth is positively correlated with rates of heterotrophy for several coral species6,52, so lower feeding rates may slow growth. Heterotrophy is certainly beneficial to corals and yet clearly heterotrophy declines for G. fascicularis under elevated CO2. Any potential impact to their basic biology warrants further research.

Despite the remaining knowledge gaps, decreased heterotrophy will have important implications for the health and resilience of corals. As ocean conditions increasingly become unfavorable for many coral species, their ability to react to such stress will become imperative to their survival. Some coral species will persist while others will not, and our data show that some G. fascicularis colonies are able to survive under high CO2 in the field, despite their lifetime exposure to elevated CO2 conditions and associated reduced zooplankton feeding rates. However, it was beyond the scope of this study to measure their physiology (tissue biomass, lipid content, calcification rates, or other biophysical parameters indicative of their overall health). Such measurements should be conducted to better understand coral long-term survivability under ocean acidification.

Methods

Study site

The feeding experiments were conducted at Upa-Upasina Reef, a fringing reef in Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea, where a natural volcanic CO2 seep provides gradients in seawater pH55. A spatial map of the seawater carbonate chemistry, along with a detailed description of the Upa-Upasina high CO2 and control site can be found in Fabricius et al.55,56. G. fascicularis colonies were collected near the seep site where seawater approximates 7.8 pHT (total scale), and from a control site with control CO2 at ~8.1 pHT. The chamber feeding experiments were conducted aboard the back deck of the ship while moored near Upa-Upasina Reef, with G. fascicularis fragments that were freshly collected from the reef. The field and chamber experiments were conducted during two ship expeditions to the site (12–14 April 2014 and 18–20 November 2014).

Seawater carbonate chemistry

The carbonate chemistry for the field sites varied through time and long-term measurements have been reported in previous literature56. Additionally, seawater pH at total scale (pHT) was recorded at the control and elevated CO2 sites for several days surrounding the commencement of the feeding experiments using SeaFET pH sensors (Supplementary Information Figure S3). pHT values had similar ranges compared to previous expeditions55,56. Water samples were also collected, fixed with saturated mercuric chloride solution (HgCl2), and later analyzed for their dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC: μmol kg−1) and total alkalinity (AT: μmol kg−1) using the Versatile Instrument for the Determination of Total Inorganic Carbon and Titration Alkalinity (VINDTA 3C).

Carbonate chemistry was also measured for the seawater used for the chamber experiments and water temperature (°C) was recorded on site. Water samples saturated with HgCl2 were stored and later measured for DIC and AT. The water temperature was 25 °C at the time the samples were analyzed in the laboratory for its carbonate chemistry using the VINDTA 3C. DIC and AT were used to calculate other seawater parameters (Table 3), including pH at total scale (pHT), partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2: μatm), bicarbonate (HCO3−: μmol kg−1), carbonate (CO32−: μmol kg−1), aqueous carbon dioxide (CO2(aq): μmol kg−1), the saturation state of calcite (ΩCA), and the saturation state of aragonite (ΩAR), using the Excel macro CO2SYS57 under the constraints set by Dickson and Millero (1987)58.

Table 3. Seawater carbonate chemistry of the chamber experiments with dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and total alkalinity (A T) measured from water samples fixed with saturated mercuric chloride solution (HgCl2).

| Expedition | Treatment | pHT | Temperature (°C) | AT (μmol kg−1) | DIC (μmol kg−1) | pCO2 (μatm) | HCO3− (μmol kg−1) | CO32− (μmol kg−1) | CO2(>aq) (μmol kg−1) | ΩCA | ΩAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | control | 8.05 | 28.0 | 2206 | 1887 | 381 | 1652 | 225 | 9.7 | 5.54 | 3.69 |

| 1 | elevated-CO2 | 7.70 | 28.0 | 2282 | 2135 | 1028 | 1987 | 121 | 26.3 | 2.97 | 1.98 |

| 2 | control | 8.08 | 29.5 | 2270 | 1938 | 359 | 1693 | 236 | 9.5 | 5.78 | 3.84 |

| 2 | elevated-CO2 | 7.75 | 29.5 | 2336 | 2171 | 906 | 2015 | 132 | 24.0 | 3.25 | 2.15 |

DIC and AT were inputted into the Excel macro CO2SYS and used to calculate pH at total scale (pHT), partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2), bicarbonate (HCO3−), carbonate (CO32−), aqueous carbon dioxide (CO2(aq)), the saturation state of calcite (ΩCA), and the saturation state of aragonite (ΩAR).

Food collection

Zooplankton were freshly collected via plankton net tows from the control site at approximately 9 pm, i.e. 2–3 h after sunset, and shortly before the start of the field and the chamber experiments. Each net tow was very slow to minimize stress to the zooplankton. Live samples were handled with care and only living zooplankton were used as food for corals (i.e. zooplankton still suspended in the water column and actively swimming. No zooplankton that had settled at the bottom of the collection container were used). Three to six zooplankton samples were preserved in 4% formalin and kept as references to determine variation in the number and taxonomic composition of zooplankton between samples.

Field feeding experiment

Tents of 100 μm plankton mesh and 25 cm base diameter (approximately 8 L volume) were used to contain zooplankton close to corals for the duration of the feeding experiment. Five tents were placed over separate G. fascicularis colonies each at the high CO2 and the control sites. To prevent corals from consuming zooplankton that are naturally in the water column, the tents were deployed during daylight when zooplankton numbers are low and demersal zooplankton have not emerged into the water column yet. At approximately 9 pm, SCUBA divers injected three 60 ml syringes of freshly collected and concentrated zooplankton into each tent. Polyp expansion (25, 50, 75 or 100 percent expanded) was recorded at the beginning and end of the feeding period. After approximately one hour, the tents were removed and a fragment of each colony was extracted with a hammer and chisel and preserved in 4% formalin. The field experiments were conducted once during expedition 1 (three replicate coral colonies per CO2 level), and twice on two consecutive nights during expedition 2 (five replicate coral colonies per CO2 level for both nights). The plankton fed to the corals during the second expedition had similar composition and concentration in the two consecutive nights, so the results from both nights were pooled together and considered one experiment.

Chamber feeding experiment

G. fascicularis fragments were collected from both the high CO2 site and the control site. They were placed in flow-through aquaria for four days to recover. The aquaria consisted of two 60 L bins with an outboard pump supplying a constant inflow of fresh seawater. For 12 hours prior to the feeding experiment, 100 μm mesh was placed over the input valve to starve G. fascicularis, allowing any previously consumed food to be digested. Three hours prior to the feeding experiment, each coral fragment was transferred onto a raised grid platform in individual cylindrical incubation chambers (89 mm diameter, 106 mm height, 637 ml volume) without exposing them to air. Corals collected from the seeps were placed in the chambers filled with seawater from the seep site, while those from the control site were placed in chambers filled with seawater from the control site (seawater carbonate chemistry for chamber experiments found in Table 3).

Chambers were 80% immersed in a water bath. Airspace in the chamber and a hole in its upper lid facilitated gas exchange. To generate a current within the chamber, a battery driven pulley system activated magnetic stirrer bars underneath the grid53. G. fascicularis were fed at around 9 pm. Taking care to supply only living zooplankton, concentrated zooplankton was injected through a hole in the top lid of the chamber with a volumetric pipette. The zooplankton concentration was lower during the second expedition compared to the first, so a larger volume of plankton solution was inserted into the chamber during the second (30 ml) compared to the first expedition (20 ml). An additional three samples of the food were preserved in 4% formalin and kept as references. The feeding experiment was conducted in the dark, although red light was used for a few minutes at the commencement and cessation of the experiment to assess their state of polyp expansion. G. fascicularis fed for approximately one hour and then each coral piece was removed and immediately stored in 4% formalin. The chamber experiment was conducted once through an initial pilot study during expedition 1 (7 replicate coral colonies per CO2 level), and repeated during expedition 2 with additional replicates (12 replicate coral colonies per CO2 level).

To determine if elevated CO2 interferes with neurotransmitter receptor functioning, six of the coral fragments per CO2 treatment were exposed to gabazine (SR-95531, Sigma-Aldrich) at a concentration of 4 mg L−1 seawater for 30 min (chamber experiment, second expedition). Coral fragments were gently washed and transferred into their chambers filled with gabazine-free seawater. The other six colonies per CO2 treatment were exposed to the same handling procedure, but their 30 min transfer was into a container without gabazine. Experiments were then conducted as outlined above.

Food samples for corals

Food samples given to corals were compared within and between experiments. Food samples given to each replicate coral fragment were similar in quantity and composition within each experiment, and they were not different between high CO2 (7.8 pHT) and control treatments (8.1 pHT) and replicates. However, food samples varied in quantity and composition between the four field and chamber experiments. Details about the analysis of food samples are in the supplementary information, including Figure S1.

Laboratory analysis

Coral consumption was measured through coelenteron content analysis. G. fascicularis fragments were removed from formalin and placed in freshwater. Every polyp coelenteron was probed using a tungsten needle and dissecting forceps. Extracted zooplankton were identified to their major taxonomic groups. Total corallite number and corallites containing food particles were enumerated. Each coral fragment was photographed and the surface area calculated within the image-processing program, ImageJ. Corallite size was calculated by dividing the surface area of each coral fragment by the number of corallites.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were computed in R, version 3.2.2 (R Development Core Team, 2015). Generalized linear models (GLMs) were used to determine if: (1) the number of zooplankton consumed (standardized by surface area) differed across CO2 regimes (seep vs. control), expedition (one vs. two), or methods (field vs. chamber), (2) species richness (Shannon-diversity index) of the zooplankton taxa consumed by corals differed between CO2 regimes, expedition, or methods, (3) gabazine affected coral feeding rates, (4) zooplankton concentration in the food samples was different between each of the experimental runs, (5) corallite sizes were different between corals originating from seep and control sites, and (6) polyp expansion differed across CO2 levels, methods, expeditions, or from the beginning to the end of the experiment. Appropriate data distributions and link functions were chosen for each GLM. Model assumptions of independence, homogeneity of variance, and normality of error were evaluated through diagnostic tests of leverage, Cook’s distance, and dfbetas59. Checks for all GLMs indicated that no influential data points or outliers existed in the data and model assumptions were met. ANOVAS (Type II) were used to determine the minimal adequate GLM with the ‘Anova’ function in the R library ‘car’ (version 2.1-1)60. The effects of the explanatory variables on the response variables were then reported based on these GLMs.

Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) was used to determine if the zooplankton community composition of the food available to the corals, and the food consumed by the corals, differed in relation to the explanatory variables (CO2, expedition, method). To account for many zeros in the data where some zooplankton taxonomic groups were rarely present or rarely consumed, the community data was standardized using the Hellinger (square root) method within the decostand function of the vegan package in R61. A Monte-Carlo permutation test was used to determine the optimal CCA model and to assess the significance of the variation in species composition attributable to the explanatory variables (CO2, expedition, method).

For each zooplankton taxon, its percent representation in the coral coelenteron content was compared against its percent in the available food using two-tailed t-tests, assuming unequal variances between samples. Logistic regressions were used to model the response of each zooplankton taxon contained in the corals to the explanatory variables of CO2, expedition, and method. Logistic regressions use binary data of ‘successes’ and ‘failures’. In this example, ‘success’ equals the probability of each taxon being consumed (p), and ‘failure’ equals the probability of not being consumed (1-p). Logistic regressions are within the framework of GLMs and use log-odd-ratios, defined by the logit link function, to estimate the (log) odds of each taxon being consumed under each independent variable. GLMs with a binary data distribution and logit link function were checked for overdispersion. Overdispersion (residual deviance greater than the residual degrees of freedom) existed, so the data distribution was changed to quasibinomial. Anovas with a Chi-square test were applied to the results of each GLM for each zooplankton taxon.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Smith, J. N. et al. Reduced heterotrophy in the stony coral Galaxea fascicularis after life-long exposure to elevated carbon dioxide. Sci. Rep. 6, 27019; doi: 10.1038/srep27019 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the community at Upa-Upasina for their permission to study the corals on their reef, as well as the crew of the M.V. Chertan, especially Obedi Daniel and Robin (‘Lei’) Luke, for their support during the fieldwork. We additionally thank Johanna Arndt and Meliha Bademci for helping hands in the laboratory, and Glenn De’ath and Karin Boos for statistical advice. This project was funded in part by the Erasmus Mundus funded joint doctoral program MARES (FPA 2011-0016), the Great Barrier Reef Foundation’s ‘Resilient Coral Reefs Successfully Adapting to Climate Change’ Program in collaboration with the Australian Government, the BIOACID Phase II Programme of the German Science Ministry BMBF (Grant 03F0655B), and the Australian Institute of Marine Science. The authors also acknowledge the contribution by J. Ries and an anonymous referee, whose helpful reviews improved the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.N.S., J.S., G.M.S., C.R. and K.E.F. designed the experiment. J.N.S., J.S., S.H.C.N. and K.E.F. conducted the fieldwork. J.N.S. did the laboratory work and data analysis. J.N.S. and K.E.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- Grottoli A. G., Rodrigues L. J. & Palardy J. E. Heterotrophic plasticity and resilience in bleached corals. Nature 440, 1186–1189 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscatine L. & Porter J. W. Reef Corals: Mutualistic Symbioses Adapted to Nutrient-Poor Environments. Bioscience 27, 454–460 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Houlbrèque F. & Ferrier-Pagès C. Heterotrophy in tropical scleractinian corals. Biol. Rev. 84, 1–17 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier-Pagès C., Witting J., Tambutté E. & Sebens K. P. Effect of natural zooplankton feeding on the tissue and skeletal growth of the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata. Coral Reefs 22, 229–240 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Piniak G. A. & Lipschultz F. Effects of nutritional history on nitrogen assimilation in congeneric temperate and tropical scleractinian corals. Mar. Biol. 145, 1085–1096 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Rodolfo-Metalpa R., Peirano A., Houlbrèque F., Abbate M. & Ferrier-Pagès C. Effects of temperature, light and heterotrophy on the growth rate and budding of the temperate coral Cladocora caespitosa. Coral Reefs 27, 17–25 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Johannes R. E., Coles S. L. & Kuenzel N. T. The role of zooplankton in the nutrition of some scleractinian corals. Limnol. Oceanogr. 15, 579–586 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- D’Elia C. F. The uptake and release of dissolved phosphorus by reef corals. Limnol. Oceanogr. 22, 301–315 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Goreau T. F., Goreau N. I. & Yonge C. M. Reef corals: autotrophs or heterotrophs? Biol. Bull. 141, 247–260 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- Anthony K. R. N. Coral suspension feeding on fine particulate matter. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 232, 85–106 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier-Pagès C., Gattuso J. P., Cauwet G., Jaubert J. & Allemand D. Release of dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen by the zooxanthellate coral Galaxea fascicularis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 172, 265–274 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Sebens K. P., Vandersall K. S., Savina L. A. & Graham K. R. Zooplankton capture by two scleractinian corals, Madracis mirabilis and Montastrea cavernosa, in a field enclosure. Mar. Biol. 127, 303–317 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Anthony K. R. N. Enhanced energy status of corals on high-turbidity reefs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 319, 111–116 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Palardy J. E., Rodrigues L. J. & Grottoli A. G. The importance of zooplankton to the daily metabolic carbon requirements of healthy and bleached corals at two depths. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 367, 180–188 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds P. J. Zooplanktivory ameliorates the effects of ocean acidification on the reef coral Porites spp. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 2402–2410 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Towle E. K., Enochs I. C. & Langdon C. Threatened Caribbean coral is able to mitigate the adverse effects of ocean acidification on calcification by increasing feeding rate. PLoS One e0123394, 10.1371/journal.pone.0123394 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doney S. C., Fabry V. J., Feely R. A. & Kleypas J. A. Ocean acidification: the other CO2 problem. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 1, 169–192 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh-Guldberg O. et al. Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science. 318, 1737–1742 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenkard E. J. et al. Calcification by juvenile corals under heterotrophy and elevated CO2. Coral Reefs 32, 727–735 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. L., McCorkle D. C., De Putron S., Gaetani G. A. & Rose K. A. Morphological and compositional changes in the skeletons of new coral recruits reared in acidified seawater: Insights into the biomineralization response to ocean acidification. Geochemistry, Geophys. Geosystems 10, 10.1029/2009GC002411 (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin A., Denis V. & Cuet P. Is the response of coral calcification to seawater acidification related to nutrient loading? Coral Reefs 30, 911–923 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb M., Cohen A. L. & McCorkle D. C. An investigation of the calcification response of the scleractinian coral Astrangia poculata to elevated pCO2 and the effects of nutrients, zooxanthellae and gender. Biogeosciences 9, 29–39 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Comeau S., Carpenter R. C. & Edmunds P. J. Effects of feeding and light intensity on the response of the coral Porites rus to ocean acidification. Mar. Biol. 160, 1127–1134 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Pacherres C. O., Schmidt G. M. & Richter C. Coral growth and bioerosion of Porites lutea in response to large amplitude internal waves. J. Exp. Biol. 216, 4365–4374 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlbrèque F. et al. Ocean acidification reduces feeding rates in the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60, 89–99 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Hii Y. S., Soo C. L. & Liew H. C. Feeding of scleractinian coral, Galaxea fascicularis, on Artemia salina nauplii in captivity. Aquac. Int. 17, 363–376 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Wijgerde T., Diantari R., Lewaru M. W., Verreth J. A. J. & Osinga R. Extracoelenteric zooplankton feeding is a key mechanism of nutrient acquisition for the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 3351–3357 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoadley K. D., Szmant A. M. & Pyott S. J. Circadian clock gene expression in the coral Favia fragum over diel and lunar reproductive cycles. PLoS One 6, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertucci A., Forêt S., Ball E. E. & Miller D. J. Transcriptomic differences between day and night in Acropora millepora provide new insights into metabolite exchange and light-enhanced calcification in corals. Mol. Ecol. 24, 4489–4504 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierobon P. et al. Biochemical and functional identification of GABA receptors in hydra vulgaris. Life Sci. 56, 1485–1497 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierobon P., Tino A., Minei R. & Marino G. Different roles of GABA and glycine in the modulation of chemosensory responses in Hydra vulgaris (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa). Hydrobiologia 530–531, 59–66 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Pierobon P. Coordinated modulation of cellular signaling through ligand-gated ion channels in Hydra vulgaris (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa). Int. J. Dev. Biol. 56, 551–565 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson G. E. et al. Near-future carbon dioxide levels alter fish behaviour by interfering with neurotransmitter function. Nat. Clim. Change. 2, 201–204 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Watson S.-A. et al. Marine mollusc predator-escape behaviour altered by near-future carbon dioxide levels. Proc. Biol. Sci. 281, http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.2377 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist N. Palatability of invertebrate larvae to corals and sea anemones. Marine Biology 126, 745–755 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Porter J. W. Zooplankton feeding by the caribbean reef-building coral Montastrea cavernosa. Proceedings of the Second International Coral Reef Symposium 1, 111–125 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Leal M. C., Nejstgaard J. C., Calado R., Thompson M. E. & Frischer M. E. Molecular assessment of heterotrophy and prey digestion in zooxanthellate cnidarians. Mol. Ecol. 23, 3838–3848 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwa R. et al. Effects of acidified seawater on early life stages of scleractinian corals (Genus Acropora). Fish. Sci. 76, 93–99 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Fine M. & Tchernov D. Scleractinian coral species survive and recover from decalcification. Science 315, 1811 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alldredge A. L. & King J. M. Effects of moonlight on the vertical migration patterns of demersal zooplankton. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 44, 133–156 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood P. G. Acquisition and use of nematocysts by cnidarian predators. Toxicon 54, 1065–1070 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özbek S., Balasubramanian P. G. & Holstein T. W. Cnidocyst structure and the biomechanics of discharge. Toxicon 54, 1038–1045 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabito R., Marino A., Lauf P. K., Adragna N. C. & La Spada G. Sea water acidification affects osmotic swelling, regulatory volume decrease and discharge in nematocytes of the jellyfish Pelagia noctiluca. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 32, 77–85 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bythell J. C. & Wild C. Biology and ecology of coral mucus release. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 408, 88–93 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. & Holcomb M. Why corals care about ocean acidification: uncovering the mechanism. Oceanography 22, 118–127 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Castillo K. D., Ries J. B., Bruno J. F. & Westfield I. T. The reef-building coral Siderastrea siderea exhibits parabolic responses to ocean acidification and warming. Proc. Biol. Sci. 281, http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.1856 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodolfo-Metalpa R. et al. Coral and mollusc resistance to ocean acidification adversely affected by warming. Nat. Clim. Change. 1, 308–312 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Anthony K. R. N. Enhanced particle-feeding capacity of corals on turbid reefs (Great Barrier Reef, Australia). Coral Reefs 19, 59–67 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- van Os N. et al. Influence of heterotrophic feeding on the survival and tissue growth rates of Galaxea fascicularis (Octocorralia: Occulinidae) in aquaria. Aquaculture 330–333, 156–161 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier-Pagès C., Hoogenboom M. & Houlbrèque F. The role of plankton in coral trophodynamics. Coral Reefs: An Ecosystem in Transition (Springer Science, 2011), 10.1007/978-94-007-0114-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Séré M. G., Massé L. M., Perissinotto R. & Schleyer M. H. Influence of heterotrophic feeding on the sexual reproduction of Pocillopora verrucosa in aquaria. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 395, 63–71 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Houlbrèque F., Tambutté E. & Ferrier-Pagès C. Effect of zooplankton availability on the rates of photosynthesis, and tissue and skeletal growth in the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 296, 145–166 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Strahl J. et al. Physiological and ecological performance differs in four coral taxa at a volcanic carbon dioxide seep. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A 184, 179–186 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Moghrabi S., Allemand D., Couret J. M. & Jaubert J. Fatty acids of the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis: effect of light and feeding. J. Comp. Physiol. B 165, 183–192 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius K. E. et al. Losers and winners in coral reefs acclimatized to elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. Nat. Clim. Change. 1, 165–169 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius K. E., Kluibenschedl A., Harrington L., Noonan S. & De’ath G. In situ changes of tropical crustose coralline algae along carbon dioxide gradients. Sci. Rep. 5, 9537 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis E. & Wallace D. Program developed for CO2 system calculations. ORNL/CDIAC-105. Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, Tennessee (1998).

- Dickson A. G. & Millero F. J. A comparison of the equilibrium constants for the dissociation of carbonic acid in seawater media. Deep Sea Res. Part A, Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 34, 1733–1743 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Y. & Cohen J. Y. Statistics and Data with R: An Applied Approach Through Examples. (John Wiley & Sons Ltd., 2008), 10.1111/j.1751-5823.2010.00109_8.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. & Weisberg S. An R Companion to Applied Regression. (Sage, 2011), at http://socserv.socsci.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion. [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P. & Gallagher E. D. Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia 129, 271–280 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.