Abstract

Background and objective

Time-average proteinuria (TAp) is the strongest predictor of renal survival in IgA nephropathy (IgAN). Little is known about the utility and safety of corticosteroids (CS) to obtain TAp<1 g/d in patients with advanced IgAN. This study sought to evaluate TAp at different degree of baseline renal function and histologic severity during CS use and to investigate treatment safety.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We performed one-stage individual-patient data meta-analysis among 325 patients with IgAN enrolled in three prospective, randomized clinical trials. Patients were divided into three groups according to treatment: no treatment (NT; supportive therapy), CS, and CS plus azathioprine (CS+A). Associations of TAp with histologic grading, treatment, and eGFR at baseline were performed with linear regression models for repeated measures. The median follow-up duration was 66.6 months (range, 12–144 months).

Results

In the first 6 months, proteinuria did not change in the NT group and decreased substantially in the other groups(CS: from a mean±SD of 2.20±1.0 to 0.8 [interquartile range, 0.4–1.2] g/d; CS+A: from 2.876±2.1 to 1.0 [interquartile range, 0.5–1.7] g/d), independent of the degree of histologic damage and baseline eGFR. The percentage of patients who maintained TAp<1 g/d was 30.2% in the NT, 67.3% in the CS, and 66.6% in the CS+A group. Thirty-four patients experienced adverse events: none in the NT, 11 (6.4%) in the CS, and 23 (20.7%) in the CS+A group. The risk of developing adverse events increased with decreasing levels of eGFR (from 2.3% to 15.4%). The addition of azathioprine to CS further increased the percentage of patients with adverse events (16.8% versus 5.7% in study 2 and 30.0% versus 15.4% in study 3; overall P<0.001).

Conclusions

In patients with IgAN, CS can reduce proteinuria and increase the possibility of maintaining TAp<1 g/d, regardless of the stage of CKD and the histologic damage. The risk of major adverse events is low in patients with normal renal function but increases in those with impaired renal function and with the addition of azathioprine.

Keywords: IgA nephropathy, proteinuria, histopathology, chronic kidney disease, azathioprine, follow-up studies, humans, kidney, prospective studies, renal insufficiency

Introduction

Regardless of baseline proteinuria, patients with IgA nephropathy (IgAN) who achieve and sustain proteinuria levels <1 g/d during follow-up have a more favorable renal outcome (1–3). Time-average proteinuria (TAp) is now considered a marker not only of disease activity but also of treatment response (3). With the aim of obtaining proteinuria <1 g/d and preserve renal function, recent guidelines suggest the use of corticosteroids (CS) in patients with an eGFR>50 ml/min per 1.73 m2 who have proteinuria >1 g/d despite at least 3–6 months of treatment with renin-angiotensin system blockers (RASBs) (4,5). Accordingly, CS are now widely used in patients with IgAN who have proteinuria >1 g/d and normal renal function. Conversely, little is known about effectiveness and safety of CS or immunosuppressants in more advanced phases of CKD. A recent retrospective analysis from the European Validation Study of the Oxford Classification of IgAN (VALIGA) showed long-term benefits of CS in patients with an initial eGFR<50 ml/min per 1.73 m2. However, no information is available on CS doses, the rate of decrease of proteinuria after CS administration, and the occurrence of adverse events (AEs) due to immunosuppression.

Whether histologic findings should affect treatment choices is still unclear (4). Surprisingly, VALIGA showed a possible great advantage of CS in patients with severe histologic lesions (3). The aim of our study was to evaluate the efficacy of CS in reducing and maintaining proteinuria <1 g/d during follow-up in different treatment groups of patients with IgAN who have various degrees of renal function and histologic lesions, as well as the occurrence of AEs with therapy.

Materials and Methods

Trial Descriptions

We performed a one-stage individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis (6) of three prospective, randomized clinical trials that enrolled a total of 339 patients with IgAN from 1989 to 2005 (7–9). After exclusion of 14 patients with follow-up <1 year, we considered 325 patients. The inclusion and exclusion criteria and treatment schedules have already been described (7–9). Briefly, the first trial enrolled 86 patients with proteinuria of 1–3.5 g/d and serum creatinine ≤1.5 mg/dl and compared supportive therapy (no treatment [NT]) with CS (7); the second study enrolled 207 patients with proteinuria ≥1 g/d and serum creatinine ≤2 mg/dl and compared CS with CS plus azathioprine (CS+A) (8); the third study enrolled 46 patients with proteinuria ≥1 g/d and serum creatinine >2 mg/dl and compared CS with CS+A (9). Study investigators and locations are provided in the Supplemental Material.

Histological Lesions

Histologic lesions were evaluated in 275 patients who underwent renal biopsy in the 3 months preceding enrollment by using the Churg and Sobin classification (grade 1, minimal glomerular lesions; grade 2, active glomerular, tubular, and interstitial lesions; grade 3, active and chronic lesions) (10). Unfortunately, in the present analysis we could not perform the Oxford classification (11,12) because of difficulties in retrieving and analyzing very old specimens (despite adequate storage, images often fade and become unrreadable after >10–15 years).

Renal Function

Renal function at baseline was estimated with the CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration equation (13,14). Accordingly, the patients were divided in three groups: group 1, CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration stages 1 and 2 (eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2); group 2, stage 3 (eGFR, 30–59.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2); group 3, stage 4 (eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2). The patients were also divided into three groups according to treatment: NT, CS, and CS+A.

Patients at Risk

Patients were evaluated at baseline and at the end of the 6-month treatment; afterward, examinations were made 6 months later and then every year. TAp represents an average of every proteinuria measurements during follow-up. The numbers of patients at risk during follow-up were as follows: at 6 months, 325 patients; at 1 year, 325 patients; at 2 years, 309 patients; at 3 years, 285 patients; at 4 years, 249 patients; at 5 years, 208 patients; at 6 years, 171 patients; at 7 years, 119 patients; at 8 years, 70 patients; at 9 years, 43 patients; and at 10 years, 27 patients. After calculation of Tap, the patients were divided into five categories, as described by Reich et al. (1): <0.3 g/d (TAp1), 0.3–0.9 g/d (TAp2), 1–1.9 g/d (TAp3), 2–2.9 g/d (TAp4), and ≥3 g/d (TAp5).

Statistical Analyses

The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to test the normal distribution of quantitative variables. If normally distributed, the results were expressed as mean values and SDs; otherwise, median and interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles) were reported. Qualitative variables were summarized as counts and percentages.

The IPD meta-analysis for continuous data (6) analyzed treatment effects on TAp. It combined all patient data into one random, multilevel model, taking into account the clustering of patients within studies. This allows adjustment for treatment difference and patient heterogeneity (especially in baseline renal function and RASB use) among studies. To evaluate the association between treatment and TAp over time, an interaction term between treatment and baseline eGFR or between treatment and baseline proteinuria was inserted in two multivariate models (see Results section). Results are expressed as coefficient with their 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and presented with term-specific P values; the coefficient represents the mean variation of outcomes for unit change of quantitative predictors or between levels of categorical or ordinal predictors.

AE frequencies were compared between treatment groups according to mean eGFR in each study (7–9) by means of the Fisher exact test. We considered only AE necessitating hospitalization or treatment changes. P values <0.05 were considered to represent statistically significant differences. Data were analyzed with Stata software (release 13.1, 2013; Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Patients

The main characteristics of the 325 patients at baseline are reported in Table 1 (characteristics according to different studies and type of treatment are presented in Supplemental Table 1). According to the original study protocols, 43 patients were assigned to receive NT, 171 to CS, and 111 to CS+A. More than half of the patients had almost-normal to normal renal function at baseline (group 1, 57.5%), whereas the others had reduced renal function (group 2, 33.5%; group 3, 8.9%). Because the oldest study (7) excluded patients with serum creatinine >1.5 mg/dl, no NT patients were in group 3. The severity of histologic damage was similar in the three treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline, after 6 months, and during follow-up according to treatment

| Variable | All (n=325) | NT (n=43) | CS (n=171) | CS+A (n=111) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||||

| Age, yr | 38.5±12.9 | 38.9±12.9 | 39.4±13.4 | 36.9±12.1 | 0.28 |

| Male sex | 242 (74.5) | 31 (72.1) | 124 (72.5) | 87 (78.4) | 0.51 |

| Histologic grade 1 | 24 (8.7) | 2 (4.6) | 14 (9.7) | 8 (9.1) | |

| Histologic grade 2 | 105 (38.2) | 21 (48.8) | 50 (34.7) | 34 (38.6) | |

| Histologic grade 3 | 146 (53.1) | 20 (46.5) | 80 (55.6) | 46 (52.3) | 0.52b |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.45±0.7 | 1.06±0.2 | 1.52±0.7 | 1.50±0.6 | <0.001c |

| eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (group 1) | 187 (57.5) | 37 (86) | 90 (52.6) | 60 (54) | |

| eGFR 30–59.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (group 2) | 109 (33.5) | 6 (14) | 63 (36.8) | 40 (36) | |

| eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (group 3) | 29 (8.9) | 0 | 18 (10.5) | 11 (10) | 0.002d |

| RAS blockers | 164 (50.5) | 5 (11.6) | 92 (53.8) | 67 (60.4) | <0.001e |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 132.9±16.6 | 133.4±20.7 | 133.2±16.0 | 132.2±16.0 | 0.63 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 82.7±10.4 | 83.4±12.3 | 82.8±10.1 | 82.2±10.1 | 0.79 |

| Proteinuria, g/d | 2.35±1.5 | 1.988±0.7 | 2.2±1.0 | 2.876±2.1 | <0.001f |

| 1.0 to <2.0 g/d | 183 (56.3) | 30 (69.8) | 98 (57.3) | 55 (49.5) | |

| 2.0 to <3.0 g/d | 85 (25.1) | 11 (25.6) | 47 (27.5) | 27 (24.3 | |

| ≥ 3.0 g/d | 57 (17.5) | 2 (15.2) | 26 (15.2) | 29 (26.1) | 0.02 |

| After 6 mo | |||||

| Proteinuria, g/dg | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 1.7 (1.1–2.4) | 0.8 (0.4–1.2) | 1.0 (0.5–1.7) | <0.001h |

| ≤0.3 g/d | 36 (11.6) | 0 (0) | 21 (12.9) | 15 14.4) | |

| >0.3 to <1.0 g/d | 125 (40.3) | 9 (20.9) | 78 (47.8) | 38 (36.5) | |

| 1.0 to <2.0 g/d | 94 (30.3) | 16 (37.2) | 47 (28.8) | 31 (29.8) | |

| 2.0 to <3.0 g/d | 32 (10.3) | 10 (23.3) | 12 (7.4) | 10 (9.6) | |

| ≥3.0 g/d | 23 (7.4) | 8 (18.6) | 5 (3.1) | 10 (9.6) | <0.001b,i |

| Follow-up | |||||

| RAS blockers | 259 (79.7) | 18 (41.9) | 140 (81.9) | 101 (91.0) | <0.001j |

| Proteinuria, g/dg | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | 0.7 (0.3–1.7) | <0.001k |

| ≤0.3 g/d (TAp1) | 58 (17.8) | 1 (2.3) | 35 (20.5) | 22 19.8) | |

| >0.3 to <1.0 g/d (TAp2) | 144 (44.3) | 12 (27.9) | 80 (46.8) | 52 (46.8) | |

| 1.0 to <2.0 g/d (TAp3) | 77 (23.7) | 14 (32.6) | 44 (25.7) | 19 (17.1) | |

| 2.0 to <3.0 g/d (TAp4) | 22 (6.8) | 7 (16.3) | 9 (5.3) | 6 (5.4) | |

| ≥3.0 g/d (TAp5) | 24 (7.4) | 9 (20.9) | 3 (1.7) | 12 (10.8) | <0.001b,l |

Unless otherwise noted, data are expressed as n (%) for qualitative variables and mean±SD) for quantitative variables. NT, no treatment; CS, corticosteroids; CS+A: corticosteroids plus azathioprine; RAS, renin-angiotensin system; TAp, time-average proteinuria.

P value refers to differences among three treatment groups.

P value for differences also among all proteinuria groups.

NT versus CS and NT versus CS+A: P<0.001; CS versus CS+A: P=0.98.

NT versus CS: P=0.001; NT versus CS+A: P=0.001; CS versus CS+A: P=0.97.

NT versus CS and NT versus CS+A: P<0.001; CS versus CS+A: P=0.28.

For all comparisons: P<0.001.

Values are expressed as median (interquartile range).

For all comparisons: P<0.001.

NT versus CS and NT versus CS+A: P<0.001; CS versus CS+A: P=0.13.

NT versus CS and NT versus CS+A: P<0.001; CS versus CS+A: P=0.03.

NT versus CS and NT versus CS+A: P<0.001; CS versus CS+A: P=0.002.

NT versus CS and NT versus CS+A: P<0.001; CS versus CS+A: P=0.01.

At baseline, nearly half of the patients (50.5%) were receiving RASB (versus only 9% in the NT group). During follow-up, this percentage increased homogeneously in the three treatment groups, reaching 79.7% at the last observation. Serum creatinine and 24-hour proteinuria were lower in the NT than in the CS and CS+A groups. Age, sex, histologic grading, and systolic and diastolic BP did not differ among treatment groups. The patients were followed up for a median of 66.6 months (interquartile range, 48–84 months; range, 12–144 months).

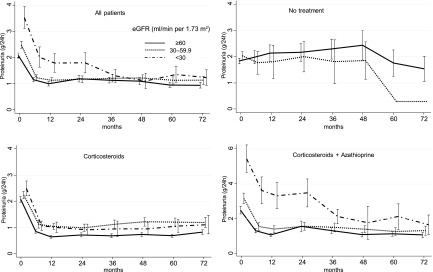

Effect of Treatment on TAp

In the NT group, overall proteinuria did not change in the first 6 months (Table 1). Conversely, in the two treated groups, proteinuria decreased >1 g/d during the first 6 months (Table 1), with a further decline during the subsequent follow-up. After 6 months of therapy, proteinuria decreased in all the CKD stages, even in group 3 (Figure 1). However, during subsequent follow-up, patients in groups 2 and 3 were more likely to have proteinuria values >1.0 g/d compared with those in group 1. The decline of proteinuria was slower in patients with baseline proteinuria >3 g/d.

Figure 1.

Trend of mean proteinuria at different values of eGFR, according to treatment. All the reductions at 6 months were statistically significant (P<0.001), except for the no treatment group. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

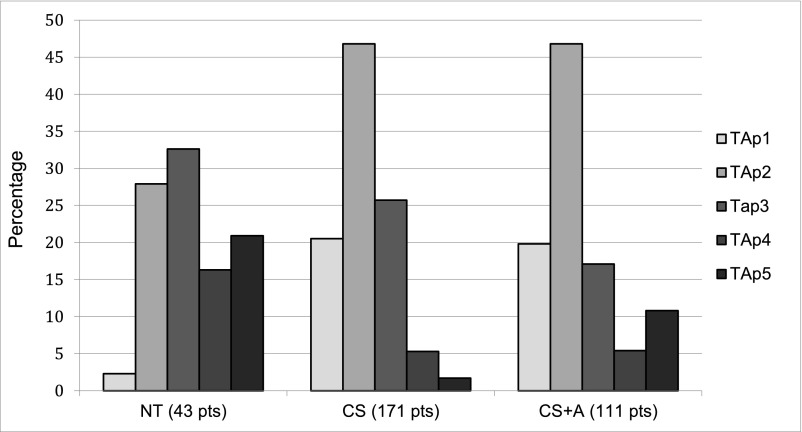

With respect to the average proteinuria during follow-up, 58 patients (17.8%) were in TAp1, 144 (44.3%) were in TAp2, 77 (23.7%) were in TAp3, 22 (6.8%) were in TAp4, and 24 (7.4%) were in TAp5. TAp values <0.3 g/d (TAp1) were almost absent in untreated patients (2.3% in the NT group versus 20.5% in the CS group and 19.8% in the CS+A group). The percentage of patients who maintained mean proteinuria <1 g/d (Tap1 and Tap2) was 30.2% in the NT group, 67.3% in the CS group, and 66.6% in the CS+A group. After 5 years, 222 patients were at risk (68.3%); after 10 years, 27 (8.3%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of time-average proteinuria (TAp) in the patients (%) according to treatment. TAp1, proteinuria < 0.3 g/d; TAp2, proteinuria 0.3–0.9 g/d; TAp3, proteinuria 1.0–1.9 g/d; TAp4, proteinuria 2.0–2.9 g/d; TAp5, proteinuria ≥ 3.0 g/d. CS, corticosteroids; CS+A: corticosteroids plus azathioprine; NT, no treatment.

Multivariate Analysis

In the first model, the outcome was TAp; the predictors were treatment, baseline proteinuria, and the interaction between treatment and baseline proteinuria, along with eGFR and RASB use; and the random factor was study). This model showed that in both the CS and CS+A groups, TAp was significantly reduced compared with the NT group (coefficient, −1.0 [95% CI, −1.2 to −0.8; P<0.001] and −0.9 [95% CI, −1.1 to −0.7; P<0.001]). Furthermore, a significant interaction was found between CS and baseline proteinuria >3 g/d (these patients had a larger decrease).

Similar results were obtained in the second model, in which the outcomes were TAp; the predictors were treatment, baseline eGFR (and the interaction of treatment and baseline eGFR), baseline proteinuria, and RASB use; and the random factor was study. However, results were less precise because of collinearity and empty strata. A significant interaction was observed between CS use and each baseline level; patients with higher baseline values had a larger decrease in TAp (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis evaluating association between treatment and time-average proteinuria over time

| Parameter | Coefficient (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||

| Proteinuria (g/d) at baseline | ||

| <2 g/d | Reference | |

| 2–2.9 g/d | 0.73 (0.38–1.08) | <0.001 |

| ≥3 g/d | 2.02 (1.17–2.88) | <0.001 |

| Treatment | ||

| None | Reference | |

| CS | −0.96 (−1.17 to 0.75) | <0.001 |

| CS+A | −0.88 (−1.10 to 0.66) | <0.001 |

| Use of RAS blockers | 0.16 (0.02–0.30) | 0.12 |

| eGFR at baseline | ||

| ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (CKD 1–2) | Reference | |

| 30–59.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (CKD 3) | 0.39 (0.02–0.26) | <0.001 |

| <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (CKD 4) | 0.92 (0.26–0.68) | <0.001 |

| Interaction between TAp at baseline and treatment | ||

| TAp<2 g/d and no treatment | Reference | |

| TAp 2–2.9 g/d and CS | −0.37 (−0.76 to 0.01) | 0.06 |

| TAp 2–2.9 g/d and CS+A | −0.43 (−0.84 to 0.02) | 0.04 |

| TAp≥3 g/d and no treatment | NP | |

| TAp≥3 g/d and CS | −1.44 (−2.32 to 0.57) | 0.001 |

| TAp≥3 g/d and CS+A | −0.66 (−1.54 to 0.22) | 0.14 |

| Model 2 | ||

| eGFR at baseline | ||

| CKD 1–2 | Reference | |

| CKD 3 | −0.27 (−0.73 to 0.20) | 0.26 |

| CKD 4 | 1.29 (0.96–1.62) | <0.001 |

| Treatment | ||

| None | Reference | |

| CS | −1.21 (−0.14 to 1.02) | <0.001 |

| CS+A | −0.99 (−1.19 to 0.78) | <0.001 |

| Use of RAS blockers | 0.11 (−0.03 to 0.25) | 0.12 |

| Proteinuria (g/d) at baseline | ||

| <2 g/d | Reference | |

| 2–2.9 g/d | 0.39 (0.27–0.51) | <0.001 |

| ≥3 g/d | 0.92 (0.77–1.07) | <0.001 |

| Interaction between eGFR at baseline and treatment | ||

| CKD 1–2 and no treatment | Reference | |

| CKD 3 and CS | 0.57 (0.08–1.06) | 0.02 |

| CKD 3 and CS+A | 0.32 (−0.18 to 0.83) | 0.21 |

| CKD 4 and no treatment | NP | |

| CKD 4 and CS | −1.17 (−1.58 to 0.77) | <0.001 |

| CKD 4 and CS+A | NP |

Model 1: model with interaction between proteinuria at baseline and treatment; model 2: model with interaction between eGRF at baseline and treatment. Results are expressed as coefficient with their 95% confidence interval (95% CI); the coefficient represents the mean variation of outcomes for unit difference of quantitative predictors or between levels of categorical or ordinal predictors. CS, corticosteroids; CS+A: corticosteroids plus azathioprine; RAS, renin-angiotensin system; TAp, time-average proteinuria. NP, not possible for collinearity and empty strata.

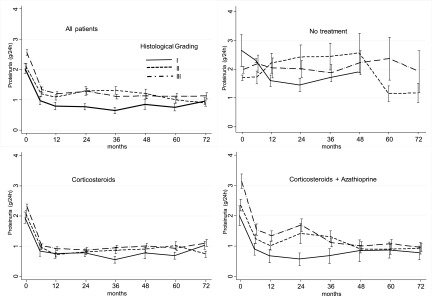

Histologic Lesions and Proteinuria in the Three Treatment Groups

Compared with lower grades, patients having grade 3 histologic damage had higher baseline proteinuria. In the NT group, proteinuria remained unchanged during follow-up, regardless of the grade of histologic lesions. Conversely, treated patients (the CS and CS+A groups) had a sharp decline in proteinuria in the first 6 months, whatever the degree of histologic damage, and then stabilized without differences related to the pathologic lesions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Trend of proteinuria in the three histologic grades, according to treatment. All the reductions at 6 months were statistically significant (P<0.001), except for the no treatment group. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Adverse Effects

The toxic effects of CS are well known and affect many organs and systems. The same holds true for azathioprine (15). In the present analysis, we considered only major AEs necessitating hospitalization or treatment changes.

Thirty-four patients experienced AEs: 0 in the NT group, 11 (6.4%) in the CS group, and 23 (20.7%) in the CS+A group (Table 3). Because of AEs, 14 patients had to reduce or stop therapy (one patient in the CS group and 11 in the CS+A group). Ten patients (five in the CS and five in the CS+A group) developed infection: seven bacterial, two viral, and one Pneumocystis jirovecii infection. Diabetes mellitus developed in three patients in the CS group and two patients in the CS+A group. Hepatotoxicity, leukopenia, and gastrointestinal symptoms were observed only in the CS+A group. No patients presented neuropsychiatric, muscular, bony, or ocular complications.

Table 3.

Adverse events in the three treatment groups

| Variable | NT | CS | CS+A | Total | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 43 | 171 | 111 | 325 | |

| Patients with adverse events | 0 | 11 (6.4) | 23 (20.7) | 34 (10.5) | <0.001a |

| Infections | 0 | 5 (2.9) | 5 (4.5) | 10 (3.0) | 0.39 |

| Diabetes | 0 | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.8) | 5 (1.5) | |

| Hypertension | 0 | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) | |

| Hepatotoxicity | 0 | 0 | 6 (5.4) | 5 (1.5) | |

| Leukopenia | 0 | 0 | 4 (3.6) | 4 (1.2) | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 0 | 0 | 3 (2.7) | 3 (0.9) | |

| Bleeding due to ulcerative esophagitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Myalgia | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | |

| Depression | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) |

Unless otherwise stated values are number (percentage). NT, no treatment; CS, corticosteroids; CS+A, corticosteroids plus azathioprine.

NT versus CS alone: P=0.13; no treatment versus CS+A: P<0.001; CS alone versus CS+A: P=0.001.

The risk of developing AEs with the use of steroids was higher with decreasing eGFR (Table 4). The addition of azathioprine to CS further increased the risk of developing AEs (16.8% versus 5.7% in study 2, 30.0% versus 15.4% in study 3; overall P<0.001).

Table 4.

Adverse events by renal function (mean eGFR) and by treatment (corticosteroids versus corticosteroids plus azathioprine)

| Variable (Reference) | Renal Function | Treatment Discontinuation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients at Risk, n | AEs in CS Group Alone, n (%) | AEs in CS+A Group, n (%) | P Value | Patients at Risk, n | AEs in CS Group Alone | AEs in CS+A Group, n (%) | |

| Study 1 (7): eGFR 90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | NT: 43; CS: 43 | 1 (2.3) | N/A | NT: 43; CS: 43 | 0 | N/A | |

| Study 2 (8): eGFR 81 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | CS: 106; CS+A: 101 | 6 (5.7) | 17 (16.8) | CS: 106; CS+A: 101 | 3 (2.8) | 15 (14.8) | |

| Study 3 (9): eGFR 3 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | CS: 26; CS+A: 20 | 4 (15.4) | 6 (30.0) | <0.001a | CS: 26; CS+A: 20 | 4 (15) | 7 (35) |

NT, no treatment; N/A, not applicable; CS, corticosteroids; CS+A, corticosteroids plus azathioprine.

P value refers to the comparison (CS to CS+A) overall adjusted for two kidney function groups

Discussion

In recent years, TAp has been considered the strongest predictor of renal survival in IgAN. Patients who reached proteinuria <1 g/d during follow-up regardless of their starting point had a good renal outcome, similar to that in patients who never had proteinuria >1 g/d (1).

In this IPD meta-analysis, CS or CS+A was more effective in reducing proteinuria in the short term and in maintaining a low TAp value over time compared with supportive therapy. In particular, average proteinuria <1 g/d (TAp1 and TAp2) was observed in 67% of the patients who had received CS (67.3% of the CS group and 66.6% of the CS+A group) and in only 30.2% of the untreated patients, showing the effectiveness of CS on TAp.

The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes clinical practice guidelines for GN recommend the use of CS only in patients with an eGFR>50 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and discourage CS when eGFR is <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2. In the presence of diffuse chronic lesions at renal biopsy, active immunosuppression is also discouraged (4). However, VALIGA found that immunosuppressants were used more frequently in patients with eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 than in those with a more preserved eGFR (60% versus 44%); this finding suggests that nephrologists have a more aggressive therapeutic attitude toward patients with severe renal insufficiency (2). A recent analysis of VALIGA compared the benefits of CS+RASB with those of RASB alone in 115 patients with eGFR<50 ml/min per 1.73 m2: Renal function decline was faster in those who used RASB alone compared with those who received CS+RASB (−4.8±7.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and −0.3±6.2 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively). Moreover, the percentage of patients reaching proteinuria <1 g/d was significantly higher in the CS+RASB recipients than in patients receiving RASB alone (3).

To investigate whether CS are also effective in patients with more advanced disease, we analyzed TAp at different degrees of renal function and renal pathologic damage. CS or CS+A achieved a significant proteinuria reduction in patients with more advanced CKD. After 6 months of treatment, the decrease in proteinuria was similar in magnitude and speed for all stages of CKD, decreasing to <1 g/d after 12 months in many patients. However, in the long term, the mean reduction was sustained only in patients with eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2; in contrast, among patients with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, proteinuria tended to slowly increase over time yet remaining <1.5 g/day. This suggests that the presence of renal insufficiency may reduce the effectiveness of CS on proteinuria over time.

IgAN often progresses with the worsening of histologic features toward the predominance of chronic lesions. Only a few studies in the literature evaluated the effect of CS on histologic lesions and considered mainly patients with normal renal function (16–18). In 2012, we described four IgAN patients with serum creatinine already >3 mg/dl at presentation and with diffuse sclerotic lesions at renal biopsy (19). After a CS course of 12 months, proteinuria decreased <1 g/d in two patients, whereas the other two experienced a slower and less persistent decrease. Despite similar histologic lesions at renal biopsy, renal function stabilized only in the two patients who had a decrease in proteinuria, suggesting that the histologic picture cannot be used alone to predict outcome. This aspect was recently studied in 1147 patients in VALIGA, which found that the predictive value of pathology was reduced in the patients who had received immunosuppressants (2). Accordingly, two other studies confirmed that the Oxford classification has no predictive value in patients treated with CS or immunosuppressants (20,21). In the present study, we found no differences in the speed and magnitude of proteinuria decrease in the three histologic grades of the Churg and Sobin classification. This finding confirms the possible positive role of CS in patients with chronic lesions. Our inability to perform the Oxford classification for technical reasons is one possible limitation of the present study.

As for other retrospective studies (12), the use of RASB was not homogenous at baseline or during follow-up because of historical reasons and changes in everyday clinical practice. In the early 1990s, when we started our first study, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors were used mainly as antihypertensive drugs; only since the late 1990s have they been used for their nephroprotective and antiproteinuric properties. For this reason, only 50.5% of the patients received RASB at baseline; this percentage had progressively increased to 79.7% at the end of the study. We are aware that this is an important and uncorrectable limitation of our analysis. However, accordingly to the recent findings of VALIGA, CS+RASB seems to be much more effective than RASB alone (3).

Because both CS and azathioprine can cause AEs, safety is an important aspect in deciding whether to start treatment in a given patient. Lv et al. (22) evaluated the incidence of AEs in 245 patients with IgAN receiving steroids in nine randomized clinical trials. Severe AEs occurred in 6.9% of the treated patients (diabetes in four patients, hypertension in 12, and gastrointestinal bleeding in one). However, little information was obtained about the frequency of AEs in patients with advanced CKD because only one study included patients with serum creatinine of 1.7 mg/dl. This information is even more important today, given the tendency to also treat patients with reduced renal function (3). In our analysis, the risk of AEs due to CS was greater in patients with impaired renal function at baseline, increasing especially in those in study 3, who had a mean eGFR of 34 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (11). Adding azathioprine to CS further increased the risk of AE, especially in patients with advanced CKD. Because CS+A is not more effective on proteinuria and renal survival compared with CS alone (9) and has an increased incidence of major AEs, this immunosuppressant should be avoided in IgAN patients with advanced CKD.

Our study has some limitations. First, it was not a prespecified analysis, and this may have reduced statistical power. Second, the designs of the three trials were not homogenous with respect to treatment schedules and patient characteristics. In addition, the patients were enrolled in different time periods, and differences in everyday clinical practice, such as RASB use, may have influenced patient outcome. We tried to overcome these limitations by using IPD analysis, which allows adjustment for treatment difference and patient heterogeneity among studies. Given that the first of the three trials was designed in the late 1980s, when a strong indication for the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors as nephroprotective agents was still not present, only a minority of the patients of this study received RASB at baseline. This may have favored the inclusion of patients who may have achieved a reduction in proteinuria <1 g/d only with RASB without needing steroids. The progressive introduction of RASB during follow-up may explain why nearly 30% of the untreated patients had a proteinuria reduction during follow-up. In all three studies, the percentage of patients taking RASB had increased homogeneously during follow-up. It is then likely that the fast decrease of proteinuria in the first 6 months was almost exclusively produced by CS or CS+A treatment. Conversely, the further small proteinuria reduction observed in the subsequent part of the follow-up in all the treatment groups may have been favored both by the increasing use of RASB over time and by a possible legacy effect of CS (3,23).

In conclusion, TAp is one of the best predictors of renal survival in patients with IgAN, and its reduction should be considered the main target of treatment. We found that CS are effective in reducing TAp, regardless of the degree of renal function and the severity of histologic damage at baseline. However, caution is needed in patients with advanced CKD, who have a higher risk of drug-related AEs. Azathioprine seems not to add any advantages compared with CS alone and increases the risk of AEs.

Disclosures

None.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.02300215/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Reich HN, Troyanov S, Scholey JW, Cattran DC Toronto Glomerulonephritis Registry : Remission of proteinuria improves prognosis in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 3177–3183, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coppo R, Troyanov S, Bellur S, Cattran D, Cook HT, Feehally J, Roberts IS, Morando L, Camilla R, Tesar V, Lunberg S, Gesualdo L, Emma F, Rollino C, Amore A, Praga M, Feriozzi S, Segoloni G, Pani A, Cancarini G, Durlik M, Moggia E, Mazzucco G, Giannakakis C, Honsova E, Sundelin BB, Di Palma AM, Ferrario F, Gutierrez E, Asunis AM, Barratt J, Tardanico R, Perkowska-Ptasinska A VALIGA study of the ERA-EDTA Immunonephrology Working Group : Validation of the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy in cohorts with different presentations and treatments. Kidney Int 86: 828–836, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tesar V, Troyanov S, Bellur S, Verhave JC, Cook HT, Feehally J, Roberts ISD, Cattran D, Coppo R VALIGA study of the ERA-EDTA Immunonephrology Working Group : Corticosteroids in IgA Nephropathy: A retrospective analysis from the VALIGA study. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2248–2258, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for glomerulonephritis – chapter 10: Immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl 2: S209–S217, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radhakrishnan J, Cattran DC: The KDIGO practice guideline on glomerulonephritis: Reading between the (guide)lines--application to the individual patient. Kidney Int 82: 840–856, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available at http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed March 1, 2015

- 7.Pozzi C, Bolasco PG, Fogazzi GB, Andrulli S, Altieri P, Ponticelli C, Locatelli F: Corticosteroids in IgA nephropathy: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 353: 883–887, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pozzi C, Andrulli S, Pani A, Scaini P, Del Vecchio L, Fogazzi G, Vogt B, De Cristofaro V, Allegri L, Cirami L, Procaccini AD, Locatelli F: Addition of azathioprine to corticosteroids does not benefit patients with IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1783–1790, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pozzi C, Andrulli S, Pani A, Scaini P, Roccatello D, Fogazzi G, Pecchini P, Rustichelli R, Finocchiaro P, Del Vecchio L, Locatelli F: IgA nephropathy with severe chronic renal failure: A randomized controlled trial of corticosteroids and azathioprine. J Nephrol 26: 86–93, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Churg J, Sobin LH: Renal Disease, Classification and Atlas of Glomerular Disease, Tokyo, Igaku-Shoin, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts IS, Cook HT, Troyanov S, Alpers CE, Amore A, Barratt J, Berthoux F, Bonsib S, Bruijn JA, Cattran DC, Coppo R, D’Agati V, D’Amico G, Emancipator S, Emma F, Feehally J, Ferrario F, Fervenza FC, Florquin S, Fogo A, Geddes CC, Groene HJ, Haas M, Herzenberg AM, Hill PA, Hogg RJ, Hsu SI, Jennette JC, Joh K, Julian BA, Kawamura T, Lai FM, Li LS, Li PK, Liu ZH, Mackinnon B, Mezzano S, Schena FP, Tomino Y, Walker PD, Wang H, Weening JJ, Yoshikawa N, Zhang H Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society : The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: Pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney Int 76: 546–556, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cattran DC, Coppo R, Cook HT, Feehally J, Roberts IS, Troyanov S, Alpers CE, Amore A, Barratt J, Berthoux F, Bonsib S, Bruijn JA, D’Agati V, D’Amico G, Emancipator S, Emma F, Ferrario F, Fervenza FC, Florquin S, Fogo A, Geddes CC, Groene HJ, Haas M, Herzenberg AM, Hill PA, Hogg RJ, Hsu SI, Jennette JC, Joh K, Julian BA, Kawamura T, Lai FM, Leung CB, Li LS, Li PK, Liu ZH, Mackinnon B, Mezzano S, Schena FP, Tomino Y, Walker PD, Wang H, Weening JJ, Yoshikawa N, Zhang H Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society : The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: rationale, clinicopathological correlations, and classification. Kidney Int 76: 534–545, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Kidney Foundation : K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39[Suppl 1]: S1–S266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ponticelli C: Glucocorticoids and immunomodulating agents. In: Treatment of Primary Glomerulonephritis, Chapter 2, edited by Ponticelli C, Glassock R. Oxford, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 1997, pp 29–31

- 16.Yoshikawa N; for the Japanese Pediatric IgA Nephropathy Study Group: A controlled trial of combined therapy for newly diagnosed severe childhood IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 101–109, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shoji T, Nakanishi I, Suzuki A, Hayashi T, Togawa M, Okada N, Imai E, Hori M, Tsubakihara Y: Early treatment with corticosteroids ameliorates proteinuria, proliferative lesions, and mesangial phenotypic modulation in adult diffuse proliferative IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 35: 194–201, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hotta O, Furuta T, Chiba S, Tomioka S, Taguma Y: Regression of IgA nephropathy: A repeat biopsy study. Am J Kidney Dis 39: 493–502, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pozzi C, Ferrario F, Visciano B, Del Vecchio L: Corticosteroids in patients with IgA nephropathy and severe chronic renal damage. Case Rep Nephrol 2012: 180691, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herzenberg AM, Fogo AB, Reich HN, Troyanov S, Bavbek N, Massat AE, Hunley TE, Hladunewich MA, Julian BA, Fervenza FC, Cattran DC: Validation of the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 80: 310–317, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi S, Lee D, Jeong KH, Moon JY, Lee SH, Lee TW, Ihm CG: Prognostic relevance of clinical and histological features in IgA nephropathy treated with steroid and angiotensin receptor blockers. Clin Nephrol 72: 353–359, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv J, Xu D, Perkovic V, Ma X, Johnson DW, Woodward M, Levin A, Zhang H, Wang H TESTING Study Group : Corticosteroid therapy in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1108–1116, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coppo R: Is a legacy effect possible in IgA nephropathy? Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 1657–1662, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]