Abstract

Context:

Testosterone increases skeletal muscle mass and strength, but the effects of testosterone on aerobic performance in mobility-limited older men have not been evaluated.

Objective:

To determine the effects of testosterone supplementation on aerobic performance, assessed as peak oxygen uptake (V̇O2peak) and gas exchange lactate threshold (V̇O2θ), during symptom-limited incremental cycle ergometer exercise.

Design:

Subgroup analysis of the Testosterone in Older Men with Mobility Limitations Trial.

Setting:

Exercise physiology laboratory in an academic medical center.

Participants:

Sixty-four mobility-limited men 65 years or older with low total (100–350 ng/dL) or free (<50 pg/dL) testosterone.

Interventions:

Participants were randomized to receive 100-mg testosterone gel or placebo gel daily for 6 months.

Main Outcome Measures:

V̇O2peak and V̇O2θ from a symptom-limited cycle exercise test.

Results:

Mean (SD) baseline V̇O2peak was 20.5 (4.3) and 19.9 (4.7) mL/kg/min for testosterone and placebo, respectively. V̇O2peak increased by 0.83 (2.4) mL/kg/min in testosterone but decreased by −0.89 (2.5) mL/kg/min in placebo (P = .035); between group difference in change in V̇O2peak was significant (P = .006). This 6-month reduction in placebo was greater than the expected −0.4-mL/kg/min/y rate of decline in the general population. V̇O2θ did not change significantly in testosterone but decreased by 1.1 (1.8) mL/kg/min in placebo, P = .011 for between-group comparisons. Hemoglobin increased by 1.0 ± 3.5 and 0.1 ± 0.8 g/dL in testosterone and placebo groups, respectively.

Conclusion:

Testosterone supplementation in mobility-limited older men increased hemoglobin and attenuated the age-related declines in V̇O2peak and V̇O2θ. Long-term intervention studies are needed to determine the durability of this effect.

“Testosterone replacement in mobility-limited older men increased peak oxygen uptake and lactate threshold.”

Testosterone supplementation to improve consequences of sarcopenia has received considerable attention in older men with low circulating testosterone levels (1, 2). Increases in skeletal muscle mass and maximal voluntary muscle strength in these men have been convincingly demonstrated (3–5) with testosterone administration. Testosterone-induced gains in muscle mass and maximal voluntary muscle strength are related to testosterone dose and circulating testosterone concentrations in young as well as older men (3, 6). Less clear, however, is testosterone's effect on performance-based measures of physical function, such as walking speed, chair rises, and the timed-up-and-go; most studies have failed to demonstrate meaningful change in these measures (1, 7, 8).

One common measure of physical performance, which has not usually been assessed in testosterone trials in older men, is aerobic performance. This measure, indexed as peak oxygen uptake (V̇O2peak), is an important assessment of physical performance as it identifies a person's ability to perform work over prolonged periods of time, a fundamental requirement for daily physical functioning and maintenance of independence (9). Testosterone administration increases red cell mass, 2,3 bisphosphoglycerate, muscle fiber capillarity (10) and as shown in mice, mitochondrial biogenesis (11, 12), all of which would be expected to increase tissue O2 delivery and uptake. However, most earlier reports of testosterone's effects on aerobic performance in young healthy men (13, 14) and male athletes (15) have not provided compelling evidence of testosterone's effect on aerobic performance.

Very few studies have determined the effects of testosterone on aerobic function in older men with functional limitations. Nair et al reported a statistically nonsignificant increase in V̇O2max of 0.48 mL/kg/min after 16 weeks of 5-mg/d transdermal testosterone patch in older men with low bioavailable testosterone (16). However, the testosterone dose used in this trial did not result in a robust increase in serum testosterone levels, leaving open the possibility that the nonsignificance of the effect was due to the modest dose administered. Furthermore, the baseline median V̇O2max in these men was 40.7 mL/kg/min, approximating the 80th–90th percentile for men used in this study (17), suggesting that these men were quite fit for their age. Other studies in less able individuals, especially in those with congestive heart failure (CHF) (18–20), have reported more suggestive associations, but it remains unclear whether testosterone supplementation improves aerobic performance in older men with mobility limitation or similar morbidity.

In work described here, we tested the hypothesis that raising testosterone levels in mobility limited older men would improve aerobic performance compared with placebo and that this improvement would be largely related to increases in hemoglobin levels using data from the Testosterone in Older Men with Mobility Limitations (TOM) Trial (8, 21).

Materials and Methods

Study design

The TOM Trial was a parallel-group, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study that enrolled community-dwelling men of age at least 65 years. Subjects were recruited and screened at 3 sites: Boston University Medical Center, New England Research Institutes, and the Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System. Outcome assessments were assessed only at Boston University Medical Center. The institutional review board at each of the 3 sites approved the study protocol, and subjects provided written informed consent.

Subjects

This report includes a subset of 64 participants in the TOM Trial for which details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria have been reported previously (8, 21). In addition, men comprising this subset were included if they were deemed to be at low cardiovascular risk and had no evidence of pulmonary disease based on the evaluation of medical history by a study physician. These individuals completed cardiopulmonary exercise testing at baseline and at the end of the 6-month intervention period. The men were more than or equal to 65 years of age with low-serum total testosterone (100–350 ng/dL [3.5–12.1 nmol/L] or low-serum free testosterone less than 50 pg/dL (173 pmol/L). The normal range for total testosterone is 300–1100 ng/dL, free testosterone 58–294 pg/mL, and sex hormone-binding globulin 15–72 nmol/L. The participants were deemed to have mobility limitation if they reported difficulty walking 2 blocks on a level surface or climbing 10 steps and had a summary score between 4 and 9 on the Short Physical Performance Battery, which reflects moderate-to-mild degree of physical dysfunction. Men were excluded who had prostate cancer, a prostate-specific antigen more than 4 ng/mL, lower urinary tract symptom score more than 21 (assessed by the International Prostate Symptom Score), unstable angina, CHF, myocardial infarction within 3 months, uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure [BP] > 160 mm Hg and diastolic pressure > 100 mm Hg), or neuromuscular diseases that limited mobility. Men who were using or had used testosterone, GH, or any anabolic therapy affecting gonadal function were excluded. Other exclusionary criteria included hematocrit more than 48%, hemoglobin A1c more than 8.5%, creatinine more than 3.5 mg/dL alanine or aspartate aminotransferase concentrations more than 3 times the upper limit of normal, body mass index more than 40 kg/m2, and untreated severe obstructive sleep apnea. Approximately 71% of men allocated to testosterone and 47% of men in the placebo group were on prescribed β-blockers and/or calcium channel blockers. Before randomization, based on their medical history, a subset of subjects were permitted to complete the highest intensity assessments including cardiopulmonary exercise testing and are reported in this article.

Procedures

Total and free testosterone assays

A Bayer-Advia-Centaur immunoassay with sensitivity 10 ng/dL was used to measure total testosterone (Quest Diagnostics). This method is well correlated with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (r2 = 0.945). Free testosterone was calculated using law-of-mass-action equations that account for competition among steroids for binding with sex hormone-binding globulin (22).

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

The participants completed a symptom limited incremental cycle ergometer exercise test with 5–15 W increments in ramp fashion using standard procedures (23, 24). Oxygen uptake (V̇O2), carbon dioxide output (V̇CO2), and pulmonary minute ventilation were measured breath-by-breath by indirect calorimetry using a fully automated metabolic measurement system (Vmax 29; Carefusion). An integrated electrocardiograph (Cardiosoft) provided continuous electrocardiogram tracings and heart rate (HR) during rest, exercise, and recovery. BP was measured by sphygmomanometry at rest, every 3 minutes during exercise, immediately after exercise, and every 3 minutes during at least 7 minutes of recovery. The cycle ergometer (ViaSprint; Carefusion) is electronically braked, adjusting work load in inverse proportion to pedal frequency in order to maintain the desired work rate. The metabolic measurement system underwent biological validation before the study. Calibration of the oxygen and carbon dioxide analyzers, the mass flow sensor, and transducers for air temperature and barometric pressure was performed before each test. The cycle ergometer was calibrated before the trial and during the course of the study. Aerobic capacity, V̇O2peak, defined in this study as the highest oxygen uptake achieved without adverse symptoms, was determined over the last 15 seconds of the test using an 8 breath rolling average. The gas exchange lactate threshold (V̇O2θ) was determined independently by 2 experienced investigators from the nonlinear increase in V̇O2 relative to V̇CO2 over the course of the test and reported as V̇O2 in mL/min (24, 25). If there was no clear breakpoint in V̇O2 relative to V̇CO2, the “dual criteria” was employed where V̇O2θ was identified from the systematic increase in the ventilatory equivalent for oxygen (V̇E/V̇O2) with increasing work rate without a corresponding increase in the ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide (V̇E/V̇CO2) (24, 26). If the independently identified V̇O2θ differed by more than 100 mL/min, the investigators discussed their findings and reevaluated until the criteria for agreement were met. Changes in aerobic function, V̇O2peak and V̇O2θ, are reported in relative units (mL/kg/min), because the energy cost of most activities are closely related to body weight. HR and the respiratory exchange ratio (R) exercise (HR at peak exercise [HRpeak] and R at peak exercise [Rpeak]) were recorded as indices of effort.

Age-related rate of decline in V̇O2peak

The annual rate of decline in V̇O2peak has been reported at about 4–5 mL/kg/min per decade using both cross sectional and longitudinal data across age spans of 20–90 years (9). Recently, the age related decline in aerobic capacity was specifically investigated in older adults (27). Longitudinal data collected over 7.9 years revealed an accelerated rate of V̇O2peak decline in older men. Men aged 60–69 years and men aged more than or equal to 70 years exhibited declines of 6.5 and 7.8 mL/kg/min per decade, respectively. Although there is some interobserver disagreement, it might be reasonable to assume a decrease of at least 4–5 mL/kg/min per decade. For this study, we used the prediction equation from a metaanalysis by Wilson and Tanaka (28), where V̇O2peak in mL/kg/min is approximated by the quantity 54.2 − (0.4 × age in years).

Age-related rate of decline in V̇O2θ

The oxygen uptake at the lactate threshold identifies a level of work that can be sustained for long periods of time and may be better associated with functional mobility limitations (29). Few studies are available that report age-related declines in V̇O2θ. A 10 year longitudinal study of 22 men aged 63 years at baseline reported a 1.4 ± 5.7 mL/kg/min decline in V̇O2θ over the 10 year period, P = .27 (30). Prediction equations for V̇O2θ based on cross-sectional data of healthy men suggest a similar 1.7 mL/kg/min fall in V̇O2θ from age 60 to age 70 (31).

Intervention

After randomization, all participants applied transdermal gel containing either placebo or 100-mg testosterone (Testim 1%; Auxilium Pharmaceuticals) daily for 6 months. This regimen raises total serum testosterone concentration in hypogonadal men into the mid-to-high normal range for eugonadal men, ie, 500–1000 ng/dL. To maintain blinding, all subjects applied 3 tubes of the gel daily that were identical in appearance. Initially, men assigned to the testosterone group applied 2 tubes each containing 5-g testosterone gel (100-mg testosterone) plus 1 tube containing placebo gel. The men assigned to placebo group received 3 tubes containing placebo that were identical in appearance to the tubes containing testosterone. Two weeks after randomization, testosterone was measured in 2 blood samples drawn 2–4 hours after gel application. If the average of the 2 testosterone concentrations was less than 500 ng/dL (17.3 nmol/L) or more than 1000 ng/dL (34.7 nmol/L), the unblinded physician either increased the daily testosterone dose to 15 g (3 tubes, 50-mg testosterone each) or decreased it to 5 g (50-mg testosterone) plus 2 tubes of placebo. The blinding was maintained as the subjects always applied 3 tubes of gel daily. For every subject who required a dose adjustment in the testosterone group, a subject assigned to placebo was given a sham dose adjustment.

Statistical analysis

Changes in outcome variables from baseline within and between groups were assessed by paired and independent t tests, respectively. Associations between V̇O2peak and serum total and free testosterone, as well as their changes from baseline, were evaluated using linear regression analysis. Linear regression was also used to describe the association between change in hemoglobin with change in V̇O2peak. The difference between the observed decline in V̇O2peak and age-predicted decline over the 6-month study period was evaluated with single sample t tests. Type I error rate for statistical significance was accepted at P = .05.

Results

The participant characteristics at baseline are displayed in Table 1. Mean age was 73 ± 5 years, and most of the subjects were overweight or obese. Serum total and free testosterone levels were similar in the 2 groups. Baseline V̇O2peak averaged 20.5 ± 4.3 and 19.9 ± 4.7 mL/kg/min for the testosterone and the placebo groups, respectively, representing between the fifth to 25th percentile of the age-adjusted reference range for this cohort (17). V̇O2θ was 13.6 ± 2.4 and 13.6 ± 2.7 mL/kg/min for the testosterone and placebo groups, respectively, representing 115% of predicted V̇O2θ (31). The HRpeak and Rpeak provided evidence of peak effort with HRpeak more than 85% of age predicted (32) and R more than 1.15.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics

| Testosterone Treated n = 28 |

Placebo Treated n = 36 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | |

| Age (y) | 73.6 | 5.8 | 65–86 | 72.8 | 4.5 | 65–82 |

| BW (kg) | 84.6 | 14.1 | 56.8–104.3 | 93.8 | 14.3 | 70.5–136.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.7 | 4.2 | 21.3–37.7 | 31.2 | 4.3 | 24.6–40 |

| Total testosterone (ng/dL) | 262.5 | 54.6 | 171–378 | 242.6 | 64.3 | 139–431 |

| Free testosterone (pg/dL) | 49.8 | 12.2 | 28–74 | 45.3 | 12.0 | 18–72 |

| Hemoglobin (g) | 14.4 | 0.9 | 12.1–15.8 | 14.1 | 1.0 | 11.3–16.2 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 42.2 | 2.7 | 36.1–46.3 | 41.4 | 3.0 | 34–47.5 |

| V̇O2peak (mL/kg/min) | 20.5 | 4.3 | 14.1–30.2 | 19.9 | 4.7 | 12.5–31.1 |

| V̇O2θ (mL/kg/min) | 13.6 | 2.4 | 10.1–20.5 | 13.6 | 2.7 | 9.8–21.3 |

| β-B or CCB; number (%) | 20 (71%) | 17 (47%) | ||||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; β-B, β-blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

Changes in testosterone and hemoglobin

In men assigned to the testosterone arm of the trial, total serum testosterone increased almost 3-fold to 714 ± 432 ng/dL (24.8 ± 15.0 nmol/L), and free testosterone increased by 101 ± 108 pg/mL (350 ± 375 pmol/L). Men assigned to placebo exhibited a small increase in total testosterone, 63 ± 174 ng/dL (2.2 ± 6.0) nmol/L), but no meaningful change in mean free testosterone. Hemoglobin increased significantly in men randomized to the testosterone group (1.0 ± 3.5g/dL) compared with a 0.1 ± 0.8 g/dL increase in those randomized to the placebo arm (P = .0005 for between group difference in change). The association for change in hemoglobin with change in V̇O2peak was r = 0.37, P = .06 for testosterone-treated men and r = 0.18, P = .30 for placebo-treated men.

V̇O2peak

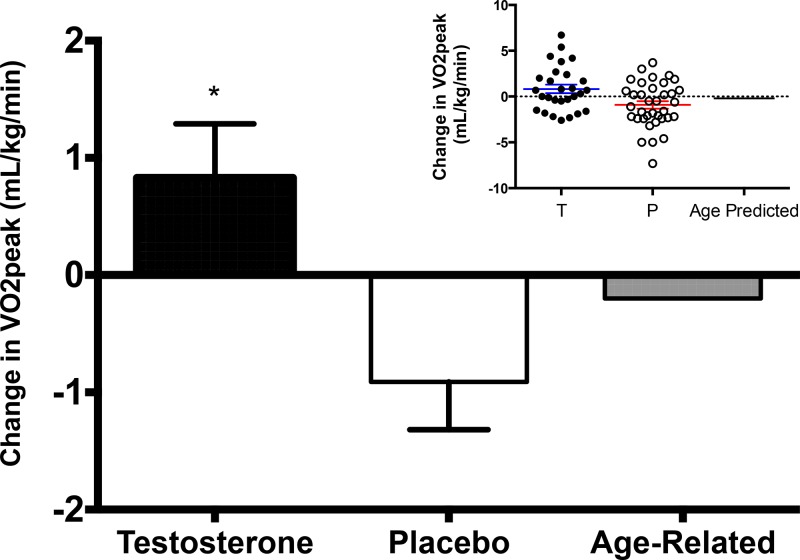

The V̇O2peak increased by 0.83 mL/kg/min over 6 months in participants randomized to the testosterone arm, thus attenuating the 6-month age-predicted decline of 0.2 mL/kg/min by about 1.0 mL/kg/min (Table 2). Fifty-four percent of men receiving testosterone exhibited attenuation of the age-predicted decline in V̇O2peak over the 6-month study period (Figure 1). In contrast, placebo-treated men experienced a 0.89 mL/kg/min decline in V̇O2peak, which exceeded the age-predicted decline in V̇O2peak by about 0.69 mL/kg/min; 33% of placebo-treated men exceeded a decline greater than age-predicted and 42% exceeded 0 change. The between group difference for the change in V̇O2peak was 1.7 mL/kg/min (95% confidence interval [CI], −3.0 to −0.5), P = .006. Neither changes in total nor changes in free testosterone were significantly associated with changes in V̇O2peak (data not shown).

Table 2.

Baseline, 6-Month, and Changes in Hemoglobin and Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test Variables

| Baseline, Mean (SD) |

6 Months, Mean (SD) |

Change, Mean (SD) |

P for Change Between Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone | Placebo | Testosterone | Placebo | Testosterone | Placebo | ||

| Hemoglobin (g) | 14.4 (0.9) | 14.1 (1.1) | 15.3 (1.6) | 14.1 (1.2) | 1.0 (3.5) | 0.1 (0.8) | <.0001 |

| VO2peak (mL/kg/min) | 20.5 (4.3) | 19.9 (4.7) | 21.3 (4.7) | 19.0 (4.7) | 0.8 (2.4) | −0.9 (2.5) | .006 |

| VO2θ (mL/kg/min) | 13.6 (2.4) | 13.6 (2.7) | 13.9 (3.0) | 12.5 (2.9) | 0.3 (1.9) | −1.1 (1.8) | .011 |

| Work rate peak (watts) | 111 (35) | 115.2 (32.3) | 114.7 (38.0) | 112 (33.3) | 3.9 (17.6) | −3.1 (13.1) | .068 |

| HRpeak (beats/min) | 124.3 (18) | 127.5 (22.9) | 125.6 (20.5) | 125 (23.4) | 1.3 (12) | −2.5 (10.8) | .188 |

| R peak | 1.20 (0.1) | 1.21 (0.12) | 1.20 (0.1) | 1.20 (0.11) | 0.01 (0.1) | −0.01 (0.08) | .361 |

| Resting systolic BP (mm Hg) | 137.0 (15.1) | 132.7 (12.8) | 132.2 (16.1) | 133.7 (17.3) | −4.7 (19.1) | 0.9 (16.6) | .218 |

| Resting diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 74.2 (11.5) | 73.8 (9.4) | 72.1 (9.6) | 73.6 (10.0) | −2.1 (9.9) | −0.2 (8.8) | .443 |

| Systolic BP at peak exercise (mm Hg) | 201 (28.4) | 199.4 (25.2) | 193.2 (28.7) | 187.0 (26.7) | −7.7 (24.5)a | −12.4 (26.5)b | .512 |

| Diastolic BP at peak exercise (mm Hg) | 83.5 (13.1) | 84.4 (10.0) | 80.6 (13.5) | 76.9 (14.5) | −2.9 (13.7) | −7.5 (15.4) | .246 |

Significantly different from baseline, P = .011.

Significantly different from baseline, P = .01.

Figure 1.

Mean changes in V̇O2peak after 6 months of testosterone supplementation or placebo in mobility limited older men. The anticipated age-related decline in VO2peak is shown for reference. Error bars represent SE. Inset indicates individual responses for testosterone and placebo groups with means and SE shown. *, significantly different than placebo, P = .006. T, testosterone; P, placebo.

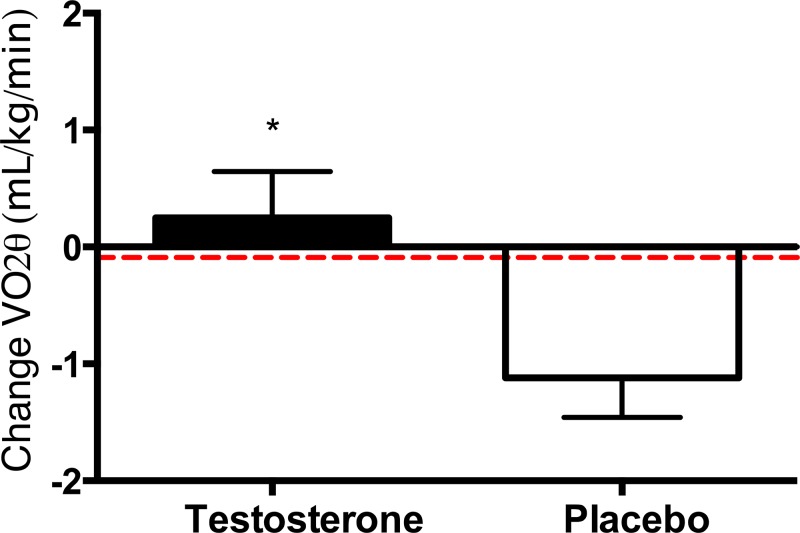

V̇O2θ

The oxygen uptake at the V̇O2θ increased by 0.25 (1.9) mL/kg/min in testosterone-treated men (P = .533) but decreased by 1.1 (1.8) mL/g in men receiving placebo (P = .002) (Figure 2). The 1.4 (95% CI, −2.4 to −0.3 mL/kg/min) difference in change in V̇O2θ between groups was significant, P = .011 (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Mean changes in oxygen uptake at the gas exchange anaerobic threshold, VO2θ, after 6 months of testosterone replacement or placebo in mobility limited older men. Error bars are SE. The horizontal dashed line indicates the predicted age-related decline in VO2θ (31). *, significantly different; P = .011.

Peak work rate

Peak work rate was not significantly different at baseline but increased slightly in the testosterone group and decreased slightly in the placebo group, although the between-group difference was not significant.

Other parameters

Other indices of peak effort during the incremental exercise test, HRpeak and Rpeak, were not significantly different between groups before or after the intervention and did not change within groups (Table 2). Subjects in both groups achieved about 85% of predicted HRpeak before and after treatment. Rpeak R was 1.20 for baseline and 6-month tests in both groups. Neither resting nor peak exercise BPs were different between groups at baseline or after 6 months of treatment. However, systolic BP at peak exercise decreased significantly in both groups at the 6-month reassessments (Table 2).

Discussion

Raising serum testosterone in older men with mobility limitation, low cardiovascular disease risk, and low testosterone levels for 6 months was associated with a significantly greater improvement in V̇O2peak than placebo. The 0.83 mL/kg/min increase in the testosterone-treated men, although modest, contrasted with the 0.89 mL/kg/min decline in V̇O2peak in placebo-treated men. The annual rate of decline in V̇O2peak has been reported across age spans of 20–90 years at about 4–5 mL/kg/min per decade. Recently, the age related decline in aerobic capacity has been specifically investigated in longitudinal studies of older adults (27). For men aged 60–69 or more than or equal to 70, the per-decade rates of decline in V̇O2peak were −6.5 and −7.8 mL/kg/min, respectively. Hence, in this trial, the between-group difference of 1.7 mL/kg/min was substantially, and arguably meaningfully, greater than the age-predicted rate of decline. Although the minimal important difference in V̇O2peak and V̇O2θ are not known, higher V̇O2peak and V̇O2θ have been associated with increased work capacity, ability to sustain work for longer periods of time (33), and reduced mortality (34). Submaximal aerobic function, eg, lactate threshold, may better reflect the ability to perform and sustain performance of typical activities of daily living than other tests of physical function (29).

Our findings contrast with those reported in younger men (13–15) or in older men with high functional capacities (16), which have generally not shown significant improvements in aerobic capacity in response to testosterone administration, possibly because of smaller windows for improvement in physical function among more able men. Studies conducted in men with CHF have revealed more substantial increases in V̇O2peak and measures of endurance in response to testosterone administration than we found in our otherwise healthy, mobility limited older men (18–20). For instance, in a 12-week study, older men with CHF (left ventricular ejection fraction < 40%) and low-serum testosterone (230 ng/dL [8 nmol/L]) received 1000-mg testosterone undecanoate or placebo every 6 weeks in addition to optimal medical therapy (18). Both V̇O2peak and 6-minute walk distance increased significantly in the testosterone group (2.9 mL/kg/min and 86 m, respectively) but not in placebo; men with lower baseline V̇O2peak showing greater improvement. No significant changes were seen in left ventricular function for either group. Other indices of aerobic function, such as the shuttle walk test (19), and the 6-minute walk test have also been reported to be responsive to testosterone administration in older men (18) with heart failure.

Contrary to observations with heart failure patients (18–20), our study did not detect a significant association between changes in total or free testosterone with changes in V̇O2peak. Mechanisms by which testosterone improves V̇O2peak and V̇O2θ are not fully understood but may include increased oxygen carrying capacity, delivery, and utilization through testosterone-induced increases in hemoglobin, tissue blood flow, muscle capillarity, myocellular oxidative capacity, and the number of type I slow muscle fibers. Testosterone administration is known to increase hemoglobin concentration (35), up-regulate erythropoietin levels, and suppress hepcidin (11, 36). Statistically, the association between change in hemoglobin with change in V̇O2peak was not robust, r = 0.37, P = .06 for testosterone-treated men and r = 0.18, P = .30 for placebo. Theoretically, however, the increase in hemoglobin of 1.0 ± 3.5 g/dL could account for nearly all of the difference in V̇O2peak. Testosterone-treated men in the present study would have been expected to increase arterial oxygen content by 1.34 mL O2/dL due to this 1-g increase in hemoglobin, thus increasing oxygen delivery. Replacement doses of anabolic steroids have been shown to accelerate fast to slow oxidative muscle fiber conversion (37), increase the number and size of type I slow fibers (38, 39), and increase mitochondrial density (39), all of which would be expected to improve the oxidative capacity of the skeletal muscle.

Our study has some notable strengths. The study had many features of good trial design: participant allocation by concealed randomization, inclusion of a placebo control, parallel group design, and blinded intervention. Testosterone levels were raised robustly into the mid to high-mid range and maintained into the target range by monitoring of testosterone levels and concealed dose adjustment. Unlike some other trials that included healthy older adults, we recruited men with mobility limitation.

This study is limited, however, by its relatively small sample size and short study duration; we do not know whether the changes in V̇O2peak or V̇O2θ observed in this study persist after treatment discontinuation, and whether they are associated with improvements in fatigue or fatigability. Studies of longer duration may add further insight into the value of improved functional capacity and submaximal work performance with testosterone replacement. We cannot exclude the possibility that the observed changes in V̇O2peak and V̇O2θ are due to testosterone itself or mediated through its aromatization to estradiol. Although there are no randomized controlled data addressing this effect in men, there are some, albeit equivocal data in women, suggesting that estrogen replacement therapy may increase exercise capacity (40, 41). We also do not know whether the changes in V̇O2peak and V̇O2θ are entirely due to testosterone-induced increase in hemoglobin or mediated through other mechanisms. Additionally, many of the subjects in the present study were using β-blockers or calcium channel blockers that are known to decrease peak HR potentially reducing V̇O2peak. However, our subjects achieved more than 85% predicted HRpeak and Rpeak of more than 1.2 at both baseline and end of study tests (Table 2), suggesting little blunting of peak HR. The clinical meaningfulness of the treatment effect on V̇O2peak − 1.7 mL/kg/min over a 6-month intervention duration, is not known.

Conclusion

Testosterone replacement in older men with low testosterone and mobility limitation was associated with significantly greater improvements in V̇O2peak and V̇O2θ than placebo. Long-term intervention studies are needed to determine the durability of this effect and whether these changes in V̇O2peak and V̇O2θ reduce objective and subjective measures of fatigue.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Boston University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (1UL1RR025771) and the trial participants. Clinical Trials Government Identifier, NCT00240981.

This work was supported by the National Institutes on Aging Grant 1UO1AG14369, the Boston Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center Grant 5P30AG031679, and the Boston University Clinical and Translational Science Institute Grant 1UL1RR025771. Testosterone and placebo gel for the study were provided by Auxilium Pharmaceuticals, Norristown, PA.

Disclosure Summary: T.G.T., K.P., R.M., and J.M. have nothing to disclose. T.W.S. has received consulting fees from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. S.Bh. has received research grants from AbbVie, Eli Lilly & Co, Regeneron, Transition Therapeutics, and Novartis and consulting fees from Sanofi, Novartis, Lilly, and AbbVie. S.Bh. has equity interest in FPT, LLC; has filed patent applications on a method to calculate free testosterone and for a selective anabolic therapy; has served on the American Board of Internal Medicine Endocrinology Examination Writing Committee and the Endocrine Society Council; and S.Ba. has received research grants from AbbVie and consulting fees from Eli Lilly and Takeda.

Footnotes

- BP

- blood pressure

- CHF

- congestive heart failure

- CI

- confidence interval

- HR

- heart rate

- HRpeak

- HR at peak exercise

- R

- respiratory exchange ratio

- Rpeak

- R at peak exercise

- TOM

- Testosterone in Older Men with Mobility Limitations

- V̇CO2

- carbon dioxide output

- V̇O2

- oxygen uptake V̇O2θ, gas exchange lactate threshold

- V̇O2peak

- peak oxygen uptake.

References

- 1. Snyder PJ, Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, et al. Effects of testosterone treatment in older men. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):611–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Basaria S, Harman SM, Travison TG, et al. Effects of testosterone administration for 3 years on subclinical atherosclerosis progression in older men with low or low-normal testosterone levels: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(6):570–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhasin S, Woodhouse L, Casaburi R, et al. Older men are as responsive as young men to the anabolic effects of graded doses of testosterone on the skeletal muscle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(2):678–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Urban RJ, Bodenburg YH, Gilkison C, et al. Testosterone administration to elderly men increases skeletal muscle strength and protein synthesis. Am J Physiol. 1995;269(5 Pt 1):E820–E826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Casaburi R, Bhasin S, Cosentino L, et al. Effects of testosterone and resistance training in men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(8):870–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhasin S, Woodhouse L, Casaburi R, et al. Testosterone dose-response relationships in healthy young men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281(6):E1172–E1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hildreth KL, Barry DW, Moreau KL, et al. Effects of testosterone and progressive resistance exercise in healthy, highly functioning older men with low-normal testosterone levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):1891–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Travison TG, Basaria S, Storer TW, et al. Clinical meaningfulness of the changes in muscle performance and physical function associated with testosterone administration in older men with mobility limitation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(10):1090–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shephard RJ. Maximal oxygen intake and independence in old age. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(5):342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yu J-G, Bonnerud P, Eriksson A, Stål PS, Tegner Y, Malm C. Effects of long term supplementation of anabolic androgen steroids on human skeletal muscle. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e105330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guo W, Wong S, Li M, et al. Testosterone plus low-intensity physical training in late life improves functional performance, skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis, and mitochondrial quality control in male mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Usui T, Kajita K, Kajita T, et al. Elevated mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle is associated with testosterone-induced body weight loss in male mice. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(10):1935–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Storer T, Magliano L, Dzekov J, Woodhouse L, Casaburi R, Bhasin S. Testosterone dose-dependently increases muscle strength, power, and endurance, but not measures of aerobic capacity in healthy young men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(5):S293 (Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson LC, Roundy ES, Allsen PE, Fisher AG, Silvester LF. Effect of anabolic steroid treatment on endurance. Med Sci Sports. 1975;7(4):287–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Shea J. Anabolic steroid: effects on competitive swimmers. Nutr Rep Int. 1970;1:337–342. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nair KS, Rizza RA, O'Brien P, et al. DHEA in elderly women and DHEA or testosterone in elderly men. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(16):1647–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thompson WR, ed. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Klwer/Lippincott Williams, Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Caminiti G, Volterrani M, Iellamo F, et al. Effect of long-acting testosterone treatment on functional exercise capacity, skeletal muscle performance, insulin resistance, and baroreflex sensitivity in elderly patients with chronic heart failure a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(10):919–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Malkin CJ, Pugh PJ, West JN, van Beek EJ, Jones TH, Channer KS. Testosterone therapy in men with moderate severity heart failure: a double-blind randomized placebo controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(1):57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stout M, Tew GA, Doll H, et al. Testosterone therapy during exercise rehabilitation in male patients with chronic heart failure who have low testosterone status: a double-blind randomized controlled feasibility study. Am Heart J. 2012;164(6):893–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Basaria S, Coviello AD, Travison TG, et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(2):109–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mazer NA. A novel spreadsheet method for calculating the free serum concentrations of testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, estradiol, estrone and cortisol: with illustrative examples from male and female populations. Steroids. 2009;74(6):512–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Bricker JT, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines). Circulation. 2002;106(14):1883–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cooper C, Storer T. Exercise Testing and Interpretation: A Practical Approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sue DY, Wasserman K, Moricca RB, Casaburi R. Metabolic acidosis during exercise in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Use of the V-slope method for anaerobic threshold determination. Chest. 1988;94(5):931–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Caiozzo VJ, Davis JA, Ellis JF, et al. A comparison of gas exchange indices used to detect the anaerobic threshold. J Appl Physiol. 1982;53(5):1184–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fleg JL, Morrell CH, Bos AG, et al. Accelerated longitudinal decline of aerobic capacity in healthy older adults. Circulation. 2005;112(5):674–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wilson TM, Tanaka H. Meta-analysis of the age-associated decline in maximal aerobic capacity in men: relation to training status. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278(3):H829–H834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alexander NB, Dengel DR, Olson RJ, Krajewski KM. Oxygen-uptake (VO2) kinetics and functional mobility performance in impaired older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(8):734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stathokostas L, Jacob-Johnson S, Petrella RJ, Paterson DH. Longitudinal changes in aerobic power in older men and women. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97(2):781–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Davis JA, Storer TW, Caiozzo VJ. Prediction of normal values for lactate threshold estimated by gas exchange in men and women. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1997;76(2):157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tanaka H, Monahan KD, Seals DR. Age-predicted maximal heart rate revisited. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(1):153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sutton JR. VO2max–new concepts on an old theme. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24(1):26–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Myers J, Prakash M, Froelicher V, Do D, Partington S, Atwood JE. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(11):793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coviello AD, Kaplan B, Lakshman KM, Chen T, Singh AB, Bhasin S. Effects of graded doses of testosterone on erythropoiesis in healthy young and older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(3):914–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bachman E, Travison TG, Basaria S, et al. Testosterone induces erythrocytosis via increased erythropoietin and suppressed hepcidin: evidence for a new erythropoietin/hemoglobin set point. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(6):725–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Czesla M, Mehlhorn G, Fritzsche D, Asmussen G. Cardiomyoplasty - improvement of muscle fibre type transformation by an anabolic steroid (metenolone). J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29(11):2989–2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ustünel I, Akkoyunlu G, Demir R. The effect of testosterone on gastrocnemius muscle fibres in growing and adult male and female rats: a histochemical, morphometric and ultrastructural study. Anat Histol Embryol. 2003;32(2):70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sinha-Hikim I, Roth SM, Lee MI, Bhasin S. Testosterone-induced muscle hypertrophy is associated with an increase in satellite cell number in healthy, young men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285(1):E197–E205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Redberg RF, Nishino M, McElhinney DB, Dae MW, Botvinick EH. Long-term estrogen replacement therapy is associated with improved exercise capacity in postmenopausal women without known coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2000;139(4):739–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mercuro G, Saiu F, Deidda M, Mercuro S, Vitale C, Rosano GM. Effect of hormone therapy on exercise capacity in early postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(4):780–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]