Abstract

The mariner-based Himar1 system has been utilized for creating mutant libraries of many Gram-positive bacteria. Streptococcus suis serotype 2 (SS2) and Streptococcus equi ssp. zooepidemicus (SEZ) are primary pathogens of swine that threaten the swine industry in China. To provide a forward-genetics technology for finding virulent phenotype-related genes in these two pathogens, we constructed a novel temperature-sensitive suicide shuttle plasmid, pMar4s, which contains the Himar1 system transposon, TnYLB-1, and the Himar1 C9 transposase from pMarA and the repTAs temperature-sensitive fragment from pSET4s. The kanamycin (Kan) resistance gene was in the TnYLB-1 transposon. Temperature sensitivity and Kan resistance allowed the selection of mutant strains and construction of the mutant library. The SS2 and SEZ mutant libraries were successfully constructed using the pMar4s plasmid. Inverse-Polymerase Chain Reaction (Inverse-PCR) results revealed large variability in transposon insertion sites and that the library could be used for phenotype alteration screening. The thiamine biosynthesis gene apbE was screened for its influence on SS2 anti-phagocytosis; likewise, the sagF gene was identified to be a hemolytic activity-related gene in SEZ. pMar4s was suitable for mutant library construction, providing more information regarding SS2 and SEZ virulence factors and illustrating the pathogenesis of swine streptococcosis.

Transposable elements (TEs), or transposons, are remarkably diverse molecular tools for random mutagenesis in bacterial chromosomes. Transposon-based, signature-tagged mutagenesis in bacteria is a widely used and effective strategy for finding new virulence factors and studying bacterial pathogenesis. This technique has pinpointed many genes that are crucial for the infectivity of a variety of pathogens1,2. Several transposon-based gene delivery systems have already been utilized to create mutant libraries in streptococci3,4, although almost all of them have properties that limit their usefulness. Tn916 is a conjugative transposon in Gram-positive bacteria, but harbors a preferred insertion site of a conserved AT-rich sequence5. Tn917 is available for high integration efficiency mutagenesis in many Gram-positive bacteria, but random mutants are relatively scarce due to the existence of hot spots, and as such, Tn917 is less productive2. Many new transposons have been developed through modification of Tn916, such as Tn3872 and Tn3704. These new transposons have been used for streptococcus mutation in many studies, but insertion site hot spots limit the application of these transposons6,7. Tn10, Tn4001 and Mu-based transposons are rarely used in streptococcus.

Himar1 is a transposable element that belongs to the mariner family of transposons. Originally isolated from Haematobia irritans, Himar1 has been extensively used to generate large numbers of bacterial insertion mutants8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Due to its ubiquitous dinucleotide target, TA, and simple transposition mechanism (no obvious host factors required), Himar1 has become the state-of-the-art genetic tool for random mutagenesis in bacterial genomes17. The Himar1 system has successfully been used for the mutagenesis of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus equi subsp. equi18,19. However, this system has never been used in Streptococcus suis serotype 2 (SS2) and Streptococcus equi ssp. Zooepidemicus (SEZ). Thus, the development of a novel Himar1 transposon mutagenesis system suitable for these swine streptococcosis pathogens was the primary purpose of this study.

SS2 and SEZ are responsible for great economic losses to pig agriculture in China. These two pathogens are also capable of infecting human beings, thereby threatening public health20,21,22. Knowledge of the virulence factors of SS2 and SEZ is limited, restricting the study of their pathogenesis. Although previous work has determined the complete genome sequence of several SS2 and SEZ strains, most of their genes have unknown functions and remain uncharacterized23,24. Transposons are routinely employed to screen for genes related to a specific phenotype to investigate bacterial virulence genes. In this study, we constructed a temperature-sensitive plasmid with the Himar1 system that can be used to generate mutants in the SS2 and SEZ genomes. Furthermore, we successfully constructed SS2 and SEZ mutation libraries, which are suitable for further virulence gene screening.

Results

Analysis of transcription factor σ A in SS2 and SEZ

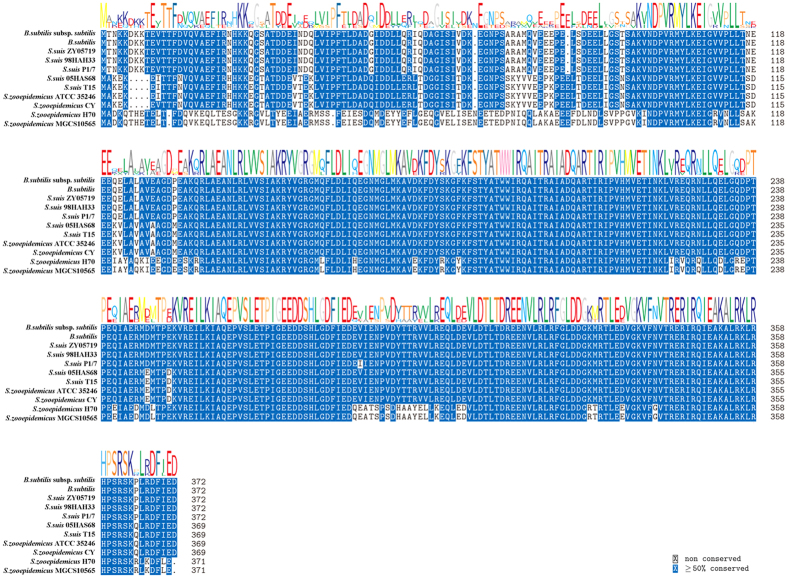

The RopD in SS2 and SEZ has high homology to the SigA of Bacillus subtilis, which also known as σA with an active Himar1 promoter. RopD from five SS2 strains and four SEZ strains were chosen to compare with the SigA in Bacillus subtilis. As shown in Fig. 1, there was greater than 90% homology among B. subtilis SigA protein, SS2 RopD protein and SEZ RopD protein. These proteins had high level of identity. Thus, we decided to retain the Himar1 promoter of pMarA in the constructed pMar4s plasmid.

Figure 1. Homology analysis of the SigA protein from B. subtilis and the RopD protein from SS2 and SEZ.

Position weight matrix (PWM) of each amino acid is shown with the alignment results. Amino acids with greater than 50% conservation are shown in blue. RopD from five SS2 strains and four SEZ strains were chosen to compare with the SigA of Bacillus subtilis.

Construction of the mariner-based pMar4s temperature-sensitive plasmid

Plasmid pMar4s was constructed for mutagenesis of SS2 and SEZ. pMar4s is a 8265 bp temperature-sensitive suicide plasmid containing a repATs fragment from the pSET4s plasmid. The TnYLB-1 transposon, which contains the ITR1 and ITR2 repetitive sequences and kan gene for kanamycin resistance, the Himar1 C9 gene and its promoter were obtained from pMarA (Supplement 1). The pSET4s fragment was amplified by PCR with primers containing an EcoR I restriction enzyme cutting site; the pMarA fragment was obtained by direct digestion with EcoR I.

Construction of SS2 and SEZ mutant libraries with pMar4s

pMar4s was used to alter the phenotypes of SS2 and SEZ to construct mutant libraries for use in selecting genes related to bacterial virulence (Supplement 2). Insertion of the TnYLB-1 transposon into the SS2 and SEZ genome was verified by PCR. As pMar4s contained Spc resistance on its backbone, loss of the plasmid from mutants was confirmed by culturing bacteria on Spc-resistance plates. Only PCR-positive, Kan-resistant, Spc-sensitive bacteria were included in the library. Of 275 randomly chosen SS2 mutants on the THB plates containing Kan, 193(70%) were Kan resistance and 82(30%) were Spc sensitivity. The transposition rate is about 70% in the SS2 mutants. In this manner, 2400 strains of SS2 mutants and 2400 strains of SEZ mutants were rapidly generated.

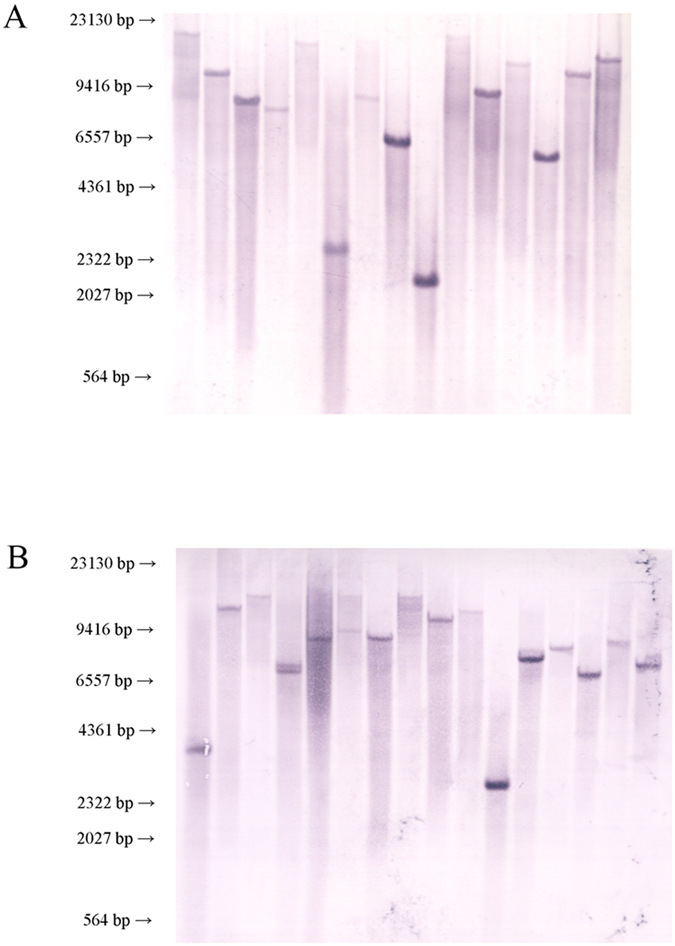

Mutants were randomly chosen from the SS2 and SEZ libraries for insertion site randomness detection by Inverse-PCR. The technological process and Inverse-PCR results are shown in Supplement 3. This technique revealed that the TnYLB-1 transposon inserted in different locations of the bacterial genome, indicating high insertion site variability. PCR fragments of SS2 were then sequenced and analysised by the BLAST program (Table 1). Southern Blot results verified the conclusion of Inverse-PCR. A 370 bp fragment of kan gene in TnYLB-1 was used as hybridization probe, the primers used in amplification of this fragment was listed in Table 2.SS2 and SEZ mutant libraries both had great insertion sites diversity (Fig. 2).

Table 1. DNA sequence analysis of SS2 insertional mutants obtainen by TnYLB-1 tansposition from pMar4s.

| Stain | Transposon insertion | Gene name |

|---|---|---|

| ZY05719.35 | ZY05719_RS02345 | ribonuclease G |

| ZY05719.120 | ZY05719_RS02540 | permease |

| ZY05719.235 | ZY05719_RS07110 | phosphoglycolate phosphatase |

| ZY05719.456 | ZY05719_RS03750 | branched-chain amino acid ABC transporter substrate -binding protein |

| ZY05719.555 | ZY05719_RS06850 | type I restriction endonuclease subunit S |

| ZY05719.631 | ZY05719_RS08285 | 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoate octaprenyltransferase |

| ZY05719.818 | ZY05719_RS06845 | ribose 5-phosphate isomerase |

| ZY05719.999 | ZY05719_RS06545 | ABC transporter permease |

| ZY05719.1146 | ZY05719_RS09300 | DNA mismatch repair protein MutT |

| ZY05719.1313 | ZY05719_RS00990 | AraC family transcriptional regulator |

| ZY05719.1553 | ZY05719_RS09965 | recombinase RarA |

| ZY05719.1721 | ZY05719_RS02070 | 16S rRNA methyltransferase |

| ZY05719.1818 | ZY05719_RS02315 | asparagine synthetase AsnA |

| ZY05719.1933 | ZY05719_RS02005 | penicillin-binding protein |

| ZY05719.2000 | ZY05719_RS03105 | hypothetical protein |

Table 2. Primers used in this study.

| Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′) | Restriction Enzyme Site |

|---|---|---|

| ST1 | ATCATCGAATTCACTAGTGTTCGTGAATACATGTTATAATAACTA | EcoRI |

| ST2 | ATCATCGAATTCAGATCTATTAATCGCAACATCAAAC | EcoRI |

| oIPCR | GCATTTAATACTAGCGACGCC | |

| C1 | GCTTGTAAATTCTATCATAATTG | |

| C2 | AGGGAATCATTTGAAGGTTGG | |

| Southern-F | TGATCCCCAGTAAGTCAAAAAA | |

| Southern-R | TGCATCAGGCTCTTTCACTCCA | |

| RP1 | ACATGCATGCAAAGAAAGCATTTACATA | SphI |

| R2 | ACGAAGGGTAATAATGTAGCAT AACTGTCTTCCTGTAATA | |

| apbE -F | TATTACAGGAAGACAGTT ATGCTACATTATTACCCTTCGT | |

| apbE -R | CCGGAATTCTTAAGGCATTGGGTGTACAAAGGC | EcoRI |

| P2 | TGCTAGTATTATGATCATGTTCTTTCCTTTCTTTTGGG | |

| sagF-F | CCCAAAAGAAAGGAAAGAACATGATCATAATACTAGCA | |

| sagF-R | CCGGAATTCCTAATGCTGCTCTTTAAAACTAAT | EcoRI |

Figure 2. Southern blot analysis of the TnYLB-1 insertions in SS2 and SEZ.

A 388 bp fragment of kan gene in TnYLB-1 was used as hybridization probe. (A) Genome of 15 SS2 transposon mutants were isolated and detected by Southern Blot. (B) Genome of 16 SEZ transposon mutants were isolated and detected by Southern Blot. DNA fragment sizes (kbp) are indicated to the left and are based on λ-Hind III digest DNA Marker included in the separating gel.

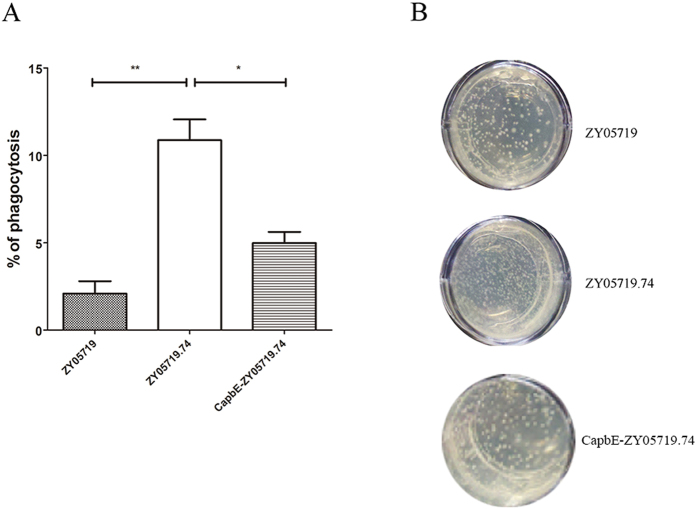

Characterization of SS2 transposon mutant genes exhibiting an altered phenotype on anti-phagocytosis

The SS2 transposon mutant library was used to screen for genes related to bacterial anti-phagocytosis. After screening approximately 200 SS2 mutants, 1 mutant strain with decreased anti-phagocytosis ability was isolated and marked as ZY05719.74. This mutant was easily ingested by macrophages (Fig. 3). The transposon insertion site of this mutant was identified by determining the sequence flanking the TnYLB-1 transposon. Sequence data from the mutant was used to search the complete open reading frames of SS2. BLAST results showed that the thiamine biosynthesis protein apbE gene (GI:502375556) was inserted by the TnYLB-1 transposon. The apbE gene complement strain CapbE-ZY05719.74 restored the anti-phagocytosis phenotype. Though the phagocytosis rate was not as low as the wild type SS2, but it significantly decreased because of the apbE gene complementing in ZY05719.74.

Figure 3. Identification of an SS2 transposon mutant exhibiting an altered anti-phagocytosis phenotype.

(A) ZY05719.74 mutant showed a significant decrease in its anti-phagocytosis phenotype compared to the ZY05719 wild strain (t-test statistical analysis). The apbE gene complement strain CapbE-ZY05719.74 restored the anti-phagocytosis phenotype. (B) The screening results of ZY05719.74 in 24-well plates. BV2 cells were cultured in 24-well plates; SS2 was used to infect cells with MOI = 1:1; after 1 h of incubation, extracellular bacteria was kill by 10 μg/ml penicillin G and 100 μg/ml gentamycin; ddH2O was added to make cells lysis; 1 ml THB containing 7.5% agar was added to each well; bacterial number should be counted after culturing at 37 °C overnight.

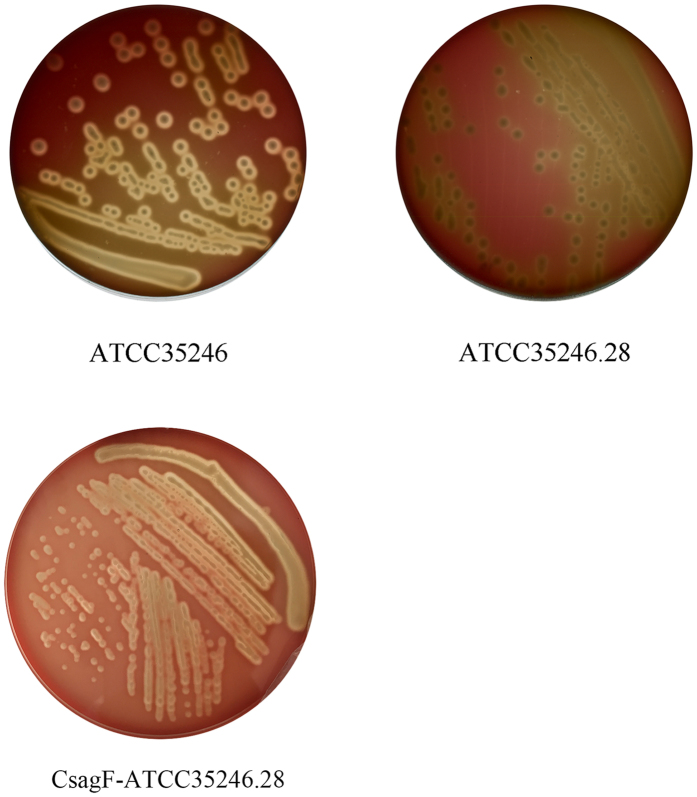

Characterization of SEZ transposon mutant genes exhibiting altered hemolytic activity

The SEZ transposon mutant library was used to screen for genes related to bacterial hemolytic activity. Of the 300 SEZ mutants screened, 1 strain with an altered hemolytic phenotype was isolated and marked as ATCC35246.28. This strain showed alpha-hemolysis instead of beta-hemolysis to hemolyze sheep blood (Fig. 4). After amplifying and sequencing the sequence flanking the TnYLB-1 transposon, the membrane protein gene (GI:504435324), homology to streptolysin associated protein SagF gene in Streptococcus pyogenes MGAS10270 (GI:195974341), was identified as that inserted by TnYLB-1. This gene was separated by a gene homology to sagE gene of Streptococcus pyogenes MGAS10270 (GI:195974340) from sagD gene (GI:504435322) of SEZ. So we believed that this membrane protein gene was the sagF gene of SEZ. The sagF gene complement strain CsagF-ATCC35246.28 was constructed and it restored the hemolytic phenotype as showing in Fig. 4.

Figure 4. Identification of an SEZ transposon mutant exhibiting an altered hemolytic activity phenotype.

The ATCC35246.28 SEZ mutant showed an altered hemolytic phenotype; the hemolytic activity of mutant strain decreased and exhibited alpha-hemolysis instead of beta-hemolysis on the sheep blood plates. The sagF gene complement strain CsagF-ATCC35246.28 restored the β-hemolytic phenotype.

Methods and Materials

Cells, bacterial strains and growth conditions

The SS2 strain, ZY05719, and the SEZ strain, ATCC 35246, were isolated from dead pigs in the Sichuan province of China. The bacteria were cultured in Todd Hewitt broth (THB) (Oxoid Ltd., USA). Solid media contained 1.5% agar. When necessary, antibiotics were added to the plate or broth at the following concentrations: ampicillin (Amp), 100 μg/ml; spectinomycin (Spc), 50 μg/ml; kanamycin (Kan), 50 μg/ml. Hemolysis-deficient SEZ mutants were identified as colonies unable to show beta-hemolysis on THB plates containing 5% defibrinated sheep blood. The Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used in this study. It was cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. When pMar4s was transferred into E. coli, the cultural condition was 37 °C, antibiotics were added to the plate or broth at the following concentrations: spectinomycin (Spc), 50 μg/ml; kanamycin (Kan), 50 μg/ml. The microglial BV2 cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in DMEM (Gibco, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, USA).

Construction of the pMar4s plasmid

The temperature-sensitive shuttle plasmid pMar4s was derived from pMarA25 and pSET4s26. The fragment containing the temperature-sensitive replication origin of pWV01 lineage and the Spc-resistance gene of pSET4s plasmid was amplified using the primers ST1 and ST2 (Table 2), and EcoRI restriction sites were added to both ends of the PCR product. pMarA was digested with EcoRI and the 5.4 kbp fragment containing the mariner-based TnYLB-1 transposon was extracted from the gel and ligated to the fragment from pSET4s to construct the pMar4s plasmid.

Competent bacterial cell preparation and electroporation

The pMar4s plasmid was transformed into SS2 and SEZ by electroporation27,28. Briefly, the optical density of the bacterial culture medium at 600 nm (OD600) was monitored with a spectrophotometer. SS2 was cultured in THB with the addition of 40 mM DL-threonine to an OD600 = 0.4. SEZ cells were prepared similarly but were treated with hyaluronidase Type IV (Sigma, USA) (45 U/ml for 30 min) to allow efficient pelleting. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellets were washed twice in 20 mL of 0.5 M sucrose solution. Finally, the cells were resuspended in 250 μL of a 10% glycerol and 0.5 M sucrose solution, and divided into aliquots. The competent cells were stored at −80 °C.

Approximately 1 μg of the pMar4s plasmid was added to the competent cells. The electroporation parameters were as follows: 25 kV/cm, 200 Ω and 25 μF. Immediately after electric shock, pre-warmed THB media containing 0.3 mmol glucose (1 mL) was added to the cuvette and incubated at 28 °C for 3–4 h.

Detection of transposition events and mutant library construction

After recovery at 28 °C, the transformed colonies were spread on THB agar plates containing Kan and cultured at 37 °C for 24–48 h. The clones that had Kan resistance and Spc sensitivity were chosen for further analysis. To verify that these clones contained the TnYLB-1 transposon, they were subjected to PCR analysis using the oITR primer25. Positive colonies were selected as transposants and used to construct the mutant library.

Identification of altered SS2 and SEZ phenotypes

For SS2, the anti-phagocytosis phenotype was chosen for screening in the SS2 mutant library. BV2 cells were cultured in 24-well plates. The MOI of SS2 to BV2 was 1:1. After incubating SS2 with BV2 for 1 h, SS2 was washed off with PBS 3 times. 100 mg/ml penicillin G was used to sterilize the extracellular bacteria. After washing with PBS 3 times to remove the penicillin G, 100 μl ddH2O was added to the 24-well plates to disrupt the BV2 cells and release the ingested SS2. Liquid THB containing 0.75% agar was added to the 24-well plates and cultured at 37 °C overnight. Clones with high growth density in the 24-well plates were selected for further analysis.

The SEZ mutant library was screened for hemolytic activity phenotype. Mutants of the library were spread on THB plates containing 5% defibrinated sheep blood. Clones lacking hemolytic activity were selected for further analysis.

Mapping of transposon insertion sites

Transposon insertion sites were mapped as described by Le Breton with some modifications25. Mutant bacterial genomic DNA was digested with TaqI and ligated end to form a circle with a Rapid Ligation Kit (Roche, USA). The ligation products were purified and used as the template for inverse-PCR. The C1 and C2 primers25 used in Inverse-PCR are listed in Table 2. Inverse-PCR products were purified using the QIAgen PCR purification kit (Qiagen, USA) and sequenced with the oIPCR primer25 (Table 2). PCR fragments were sequenced by the Shanghai Sunny Biotechnology Company Limited. DNA sequence analyses were performed using the BLAST progrom (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

Southern blot analyses were performed using a DIG High Prime DNA labeling and detection starter kit I (Roche, USA). Briefly, a 388 bp fragment of kan gene in TnYLB-1 was used as hybridization probe, the primers used in amplification of this fragment was listed in Table 2. Genome of 15 SS2 transposon mutants and genome of 16 SEZ transposon mutants were randomly isolated and digested with EcoR I, then used for Southern Blot analysis.

Bioinformatics analysis

Multiple sequence alignment of transcription factor σA among Bacillus subtilis, SS2 and SEZ was performed using the msa package of the R statistical computing platform29. Plasmid sequence analyses were performed using Vector NTI Advance 11.0 (Invitrogen, USA). The BLAST program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) was used for database analysis.

Construction of complemented strains

In this stduy, the promoter sequence of the IMPDH30 was used for the construction of the two complement plasmids. As we constructed the two complementation plasmids with the promoter sequence and the target genes sequences by using splicing-by-overlap-extension(SOE) PCR31, the two promoter sequences were amplified from SS2-ZY05719 genomic DNA by PCR using the primers RP1/R2 and RP1/P2. The sequences of target genes were amplified from SS2-ZY05719 and SEZ-ATCC 35246 genomic DNA respectively by PCR using the primers in the Table 2. Then the promoter sequence and the target genes sequences were fused by SOE PCR. After digestion with Sph I and EcoR I, the framents were cloned into shuttle vector pSET232. These two vectors were transformed into the ZY05719.74 and ATCC35246.28 respectively to obtain the complement strains CapbE-ZY05719.74 and CsagF-ATCC35246.2826.

Ethics

We confirmed that all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations of the Science and Technology Agency of Jiangsu Province. The Nanjing Agricultural University Veterinary College academic board approved all experiments in this research.

Discussion

In China, swine streptococcosis is responsible for enormous economic loss and threatens the pig farming industry33. Many humans have died from infections with pathogens of swine streptococcosis since 1977. SS2 and SEZ have been identified as the most important pathogens that can cause swine streptococcosis34. Though many virulence factors have been discovered in these two bacteria through genomic sequence and bioinformatics analyses, there has not been much progress in determining the pathogenesis of these two bacteria35. Because reverse genetics technologies have shown limitations to precisely determine the genes related to virulent phenotypes from large datasets. As such, the development of an effective forward genetics virulence gene location technology was the primary purpose of this study.

Though the mariner family of transposons had been used in Gram-positive bacterial mutants such as Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus pyogenes36,37,38,39 for many years, but this system has not previously been used to study swine streptococcosis pathogens. Himar1 has a ubiquitous dinucleotide target, TA, and requires no species-specific host factors40. As its insertion sites are more random than many other transposons, Himar1 has become a great genetic tool for random mutagenesis in Gram-positive bacterial genomes and has recently been utilized to create mutant libraries of prokaryotes.

In this study, we used pMarA and pSET4s to construct a new plasmid, pMar4s, which could be used in mutating SS2 and SEZ. As σA, the transcription factor that binds to the promoter of transposase Himar1 C9, was highly homologous among B. subtilis, SS2 and SEZ, we retained this promoter in pMar4. The subsequent results prove that this promoter was universal in these 3 different bacteria. The repATs fragment imparted temperature sensitivity to pMar4s in SS2 and SEZ. This plasmid could only tolerate a 28 °C culturing condition; pMar4s was lost when the temperature was set to 37 °C. The Amp and Spc resistance genes lost their efficacy; only the Kan resistance gene inserted into the genome with the transposon retained its function. This design simplified the screening process.

Both the SS2 and SEZ mutant libraries were constructed successfully and could be used for phenotype screening. Inverse-PCR technology was able to detect the sequence flanking the TnYLB-1 transposon insertion site. Inverse-PCR also revealed the randomness of the transposon insertion site and Southern Blot results verified these results. The sampling results showed that the SS2 and SEZ mutant libraries both had great variety and were appropriate for phenotype screening.

We chose an anti-phagocytosis phenotype for the SS2 mutant library screening and a hemolytic activity phenotype for the SEZ mutant library screening. In the SS2 altered anti-phagocytosis phenotype mutant, TnYLB-1 inserted into the thiamine biosynthesis gene, apbE. Thiamine is an important nutrient for bacterial capsular polysaccharide (CPS) synthesis41. CPS helps pathogens evade ingestion by macrophages42. Inhibiting the biosynthesis of thiamine might influence CPS formation in SS2. Although the apbE gene might not be directly related to anti-phagocytosis in SS2, its mutant indeed altered the anti-phagocytosis phenotype by affecting a bacterial physiological process. Alternatively, there might be a novel mechanism connecting thiamine biosynthesis and SS2 anti-phagocytosis that needs to be studied further. The sagF gene was identified as the TnYLB-1-inserted gene in the SEZ hemolytic activity-altered phenotype mutant. In our previous study, the sagD gene was identified as a virulence factor and its mutation led to the loss of SEZ hemolytic activity43. The sagF gene was located in the same operon with sagD gene in SEZ genome, it should play an important role in SEZ hemolytic activity and was an indispensable gene in sag operon44.

In conclusion, we constructed pMar4s with the pMarA and pSET4s backbone plasmid. This novel plasmid, pMar4s, was effective for mutating SS2 and SEZ, and its insertion site variety was suitable for constructing SS2 and SEZ mutant libraries for use in altered phenotype screening. This forward genetics virulence gene location technology will provide more information regarding SS2 and SEZ virulence factors and help to illustrate the pathogenesis of swine streptococcosis.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Rui, L. et al. A novel suicide shuttle plasmid for Streptococcus suis serotype 2 and Streptococcus equi ssp. zooepidemicus gene mutation. Sci. Rep. 6, 27133; doi: 10.1038/srep27133 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31302093, 31172319, 31272581); the National Basic Research Program (973) of China (2012CB518804); the Ph.D. programs of the Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China (20130097120024); grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20130676); and the Jiangsu Province Science and Technology Support Program (BE2013433). Key projects of independent innovation of the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Y0201600144, KYZ201630). We thank Professor Haldenwang for kindly providing pMarA and Professor Sekizaki for kindly providing pSET4s and pSET2 to our lab.

Footnotes

Author Contributions H.F. and Z.M. designed the study; R.L., P.Z., Y.S. and L.Y. performed the experiments; Z.M. and H.L. analyzed the data and wrote the paper; H.Z. contributed reagents and analytical tools.

References

- Hayes F. Transposon-based strategies for microbial functional genomics and proteomics. Annual review of genetics 37, 3–29 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. H. & Kim K. J. Applications of transposon-based gene delivery system in bacteria. J Microbiol Biotechnol 19, 217–228 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater J. D. et al. Mutagenesis of Streptococcus equi and Streptococcus suis by transposon Tn917. Vet Microbiol 93, 197–206 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihlberg B. M., Cooney J., Caparon M. G., Olsen A. & Bjorck L. Biological properties of a Streptococcus pyogenes mutant generated by Tn916 insertion in mga. Microb Pathog 19, 299–315 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. R. & Churchward G. G. Conjugative transposition. Annu Rev Microbiol 49, 367–397 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poyart C., Quesne G., Acar P., Berche P. & Trieu-Cuot P. Characterization of the Tn916-like transposon Tn3872 in a strain of Abiotrophia defectiva (Streptococcus defectivus) causing sequential episodes of endocarditis in a child. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44, 790–793 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clermont D. & Horaud T. Genetic and molecular studies of a composite chromosomal element (Tn3705) containing a Tn916-modified structure (Tn3704) in Streptococcus anginosus F22. Plasmid 31, 40–48 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hava D. L. & Camilli A. Large-scale identification of serotype 4 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors. Mol Microbiol 45, 1389–1406 (2002). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoffroy M. C., Floquet S., Metais A., Nassif X. & Pelicic V. Large-scale analysis of the meningococcus genome by gene disruption: resistance to complement-mediated lysis. Genome Res 13, 391–398 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrixson D. R. & DiRita V. J. Identification of Campylobacter jejuni genes involved in commensal colonization of the chick gastrointestinal tract. Mol Microbiol 52, 471–484 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant A. J. et al. Signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis studies demonstrate the dynamic nature of cecal colonization of 2-week-old chickens by Campylobacter jejuni. Appl Environ Microbiol 71, 8031–8041 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y., Kappler A., Croal L. R. & Newman D. K. Isolation and characterization of a genetically tractable photoautotrophic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacterium, Rhodopseudomonas palustris strain TIE-1. Appl Environ Microbiol 71, 4487–4496 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. M., Tucker A. M., Driskell L. O. & Wood D. O. Mariner-based transposon mutagenesis of Rickettsia prowazekii. Appl Environ Microbiol 73, 6644–6649 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Stewart P. E., Shi X. & Li C. Development of a transposon mutagenesis system in the oral spirochete Treponema denticola. Appl Environ Microbiol 74, 6461–6464 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beare P. A. et al. Characterization of a Coxiella burnetii ftsZ mutant generated by Himar1 transposon mutagenesis. J Bacteriol 191, 1369–1381 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray G. L. et al. Genome-wide transposon mutagenesis in pathogenic Leptospira species. Infect Immun 77, 810–816 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardeau M. Transposition of fly mariner elements into bacteria as a genetic tool for mutagenesis. Genetica 138, 551–558 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May J. P., Walker C. A., Maskell D. J. & Slater J. D. Development of an in vivo Himar1 transposon mutagenesis system for use in Streptococcus equi subsp. equi. FEMS Microbiol Lett 238, 401–409 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastanet A., Prudhomme M., Claverys J. P. & Msadek T. Regulation of Streptococcus pneumoniae clp genes and their role in competence development and stress survival. J Bacteriol 183, 7295–7307 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyette-Desjardins G., Auger J. P., Xu J., Segura M. & Gottschalk M. Streptococcus suis, an important pig pathogen and emerging zoonotic agent-an update on the worldwide distribution based on serotyping and sequence typing. Emerging microbes & infections 3, e45 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk M., Xu J., Calzas C. & Segura M. Streptococcus suis: a new emerging or an old neglected zoonotic pathogen? Future Microbiol 5, 371–391, 10.2217/fmb.10.2 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z. et al. Insight into the specific virulence related genes and toxin-antitoxin virulent pathogenicity islands in swine streptococcosis pathogen Streptococcus equi ssp. zooepidemicus strain ATCC35246. BMC Genomics 14, 377 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H. et al. Genome-wide identification of allele-specific expression in response to Streptococcus suis 2 infection in two differentially susceptible pig breeds. J Appl Genet (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z. et al. Complete genome sequence of Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus strain ATCC 35246. J Bacteriol 193, 5583–5584 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Breton Y., Mohapatra N. P. & Haldenwang W. G. In vivo random mutagenesis of Bacillus subtilis by use of TnYLB-1, a mariner-based transposon. Appl Environ Microbiol 72, 327–333 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamatsu D., Osaki M. & Sekizaki T. Thermosensitive suicide vectors for gene replacement in Streptococcus suis. Plasmid 46, 140–148 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin R. E. & Ferretti J. J. Electrotransformation of Streptococci. Methods Mol Biol 47, 185–193 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong-Jie F., Fu-yu T., Ying M. & Cheng-ping L. Virulence and antigenicity of the szp-gene deleted Streptococcus equi ssp. zooepidemicus mutant in mice. Vaccine 27, 56–61 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhofer U., Bonatesta E., Horejs-Kainrath C. & Hochreiter S. msa: an R package for multiple sequence alignment. Bioinformatics (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H. et al. Contribution of eukaryotic-type serine/threonine kinase to stress response and virulence of Streptococcus suis. PLoS One 9, e91971 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrens A. N., Jones M. D. & Lechler R. I. Splicing by overlap extension by PCR using asymmetric amplification: an improved technique for the generation of hybrid proteins of immunological interest. Gene 186, 29–35 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamatsu D., Osaki M. & Sekizaki T. Construction and characterization of Streptococcus suis-Escherichia coli shuttle cloning vectors. Plasmid 45, 101–113 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura M. et al. Latest developments on Streptococcus suis: an emerging zoonotic pathogen: part 2. Future Microbiol 9, 587–591 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng ZG H. J. Outbreak of swine streptococcosis in Sichan province and identification of pathogen. Anim Husbandry Vet Med Lett 2, 7–12 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Fittipaldi N., Segura M., Grenier D. & Gottschalk M. Virulence factors involved in the pathogenesis of the infection caused by the swine pathogen and zoonotic agent Streptococcus suis. Future Microbiol 7, 259–279 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson M. et al. A mariner transposon vector adapted for mutagenesis in oral streptococci. Microbiology Open 3, 333–340 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y. et al. Application of in vitro mutagenesis to identify the gene responsible for cold agglutination phenotype of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol Immunol 48, 449–456 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Breton Y. et al. Essential Genes in the Core Genome of the Human Pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes. Scientific reports 5, 9838 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Breton Y. et al. Genome-wide identification of genes required for fitness of group A Streptococcus in human blood. Infect Immun 81, 862–875 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe D. J., Churchill M. E. & Robertson H. M. A purified mariner transposase is sufficient to mediate transposition in vitro. EMBO J 15, 5470–5479 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti L. C., Ross R. A. & Johnson K. D. Cell growth rate regulates expression of group B Streptococcus type III capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun 64, 1220–1226 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels M. R., Moses A. E., Goldberg J. B. & DiCesare T. J. Hyaluronic acid capsule is a virulence factor for mucoid group A streptococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88, 8317–8321 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z. et al. Identification of novel genes expressed during host infection in Streptococcus equi ssp zooepidemicus ATCC35246. Microbial Pathogenesis 79, 31–40 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy E. M., Cotter P. D., Hill C., Mitchell D. A. & Ross R. P. Streptolysin S-like virulence factors: the continuing sagA. Nature reviews. Microbiology 9, 670–681 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.