Abstract

The objective of this Review is to characterize content related to global health in didactic and experiential curricula of doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) programs in the United States. The review was completed through a systematic website search of 133 US PharmD programs accredited or currently in the process of obtaining accreditation to identify global health dual degrees, minors/concentrations, required and elective courses, and experiential opportunities. Programs’ course catalogs were referenced as needed to find more specific course listings/descriptions. More than 50 programs offered an elective course related to global health; eight had a required course; eight offered a minor or certification for global health; three offered dual degrees in pharmacy and global health. Fourteen institutions had a center for global health studies on campus. More than 50 programs offered experiential education opportunities in global health including international advanced pharmacy practice experiences or medical mission trips. Inclusion of and focus on global health-related topics in US PharmD programs was widely varied.

Keywords: global health, pharmacy, curriculum

INTRODUCTION

In 2009, Koplan et al published a Viewpoint in The Lancet stating that “global health is fashionable…but rarely defined.”1 The article went on to differentiate between three categories that have commonly, and erroneously, been interchanged: public health, international health, and global health. The authors proposed that while public health focuses on prevention, and international health pertains mainly to under-developed countries, global health creates its own entity by utilizing both preventative and clinical treatment strategies for health issues that may or may not transcend national boundaries. Their definition determined global health to be “an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide. Global health emphasizes transnational health issues, determinants, and solutions; involves many disciplines within and beyond the health sciences and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration; and is a synthesis of population-based prevention with individual-level clinical care.”1

There is some overlap between these three categories. Each focuses on population-based care and gives attention to underserved or vulnerable populations.1 However, there are differentiating characteristics. Public health emphasizes prevention, while international health tends to prioritize acute care. Global health concentrates on both. Global health also more broadly considers the preparation and dispersion of health workers than does public health or international health. As global health uses wide-ranging skills and practices to tackle health problems around the world, it functions as a two-way partnership between countries; international health may be viewed as a “one-way street” from developed countries to developing countries.1

Multidisciplinary care is emphasized in Koplan et al’s definition of global health. US-based health care professions such as medicine, dentistry, and nursing have become increasingly involved in global health initiatives.2-4 However, an article by Steeb et al acknowledged that “literature is limited with respect to the role of the pharmacist in global health.”5 Nevertheless, there are ample opportunities for pharmacists in global health practice through a variety of avenues overseas or locally in underserved communities.5 Additional opportunities are available for pharmacists in global health research and policy development.5,6

To sustainably collaborate and contribute to these global health opportunities, pharmacists and pharmacy students need to have the proper background and training;5 yet, no published papers comprehensively examine curricular content related to global health in US pharmacy programs.7-9 The purpose of this Review is to characterize the current content and scope of global health in US doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) programs.

METHODS

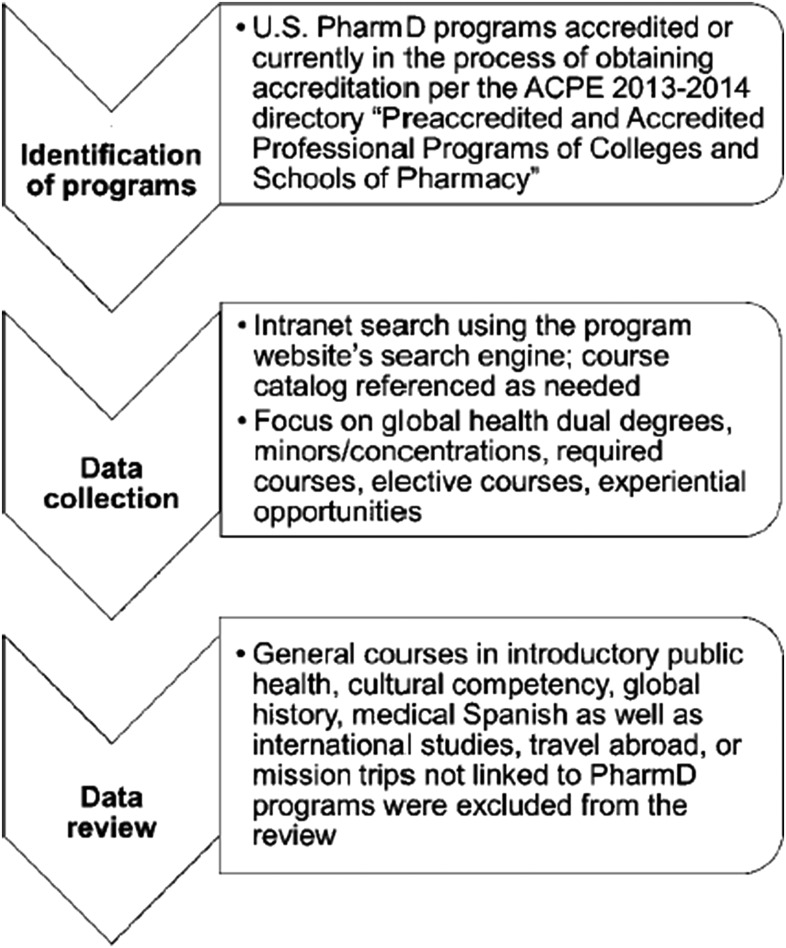

To conduct this Review of PharmD curricula, a systematic website search was completed in April-May 2014. Each of the 133 US PharmD programs accredited or currently in the process of obtaining accreditation as shown on the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) 2013-2014 directory10 was reviewed (Figure 1). Information was collected on the programs’ didactic and experiential curricula for the 2013-2014 academic year.

Figure 1.

Methodology Used to Review PharmD Curricula for Global Health Content.

Once the individual program site was accessed, documentation of the institution’s public or private status was made as well as the PharmD program’s current level of accreditation. Then, using the program website’s search engine and provided links, an Intranet search was conducted to look for global health dual degrees, minors/concentrations, required courses and elective courses. Key phrases used were “PharmD curriculum” and “PharmD dual degree.” Commonly, links were provided on the program’s website that contained lists of required courses and elective courses for the PharmD. If needed (as when the course title was too ambiguous to determine possible global health content), the institution’s course catalog was referenced to find more specific course listings and descriptions. Finally, a general Intranet search was performed on each website using the terms “global health” and “international experience” to try to identify and account for any missed information and to ensure a comprehensive search.

We documented whether global health offerings were experiential or didactic, stand alone or integrated, and specifically offered within the college/school of pharmacy or not. Mission trips offered through the school of pharmacy were classified as an experiential opportunity. International studies majors/minors or mission trips/general study abroad opportunities that were not linked specifically to the school were not included, as the focus was on PharmD program offerings. General courses such as introductory public health, cultural competency, world history, or medical Spanish were excluded from the Review, although we recognize these classes are connected with this field.

GLOBAL HEALTH IN US PHARMACY EDUCATION

Twenty-nine programs more heavily involved global health, as evidenced through the offering of global health dual degrees or concentrations, required courses, or affiliation with global centers. Eleven of these institutions were private and 18 were public. Twenty-eight were fully accredited, with one program having candidate status. Geographically, the largest proportion of these PharmD programs were located in the Northwest/Western United States.

Inclusion of and focus on global health-related topics in PharmD curricula of US programs varied widely. Three programs offered dual degrees in pharmacy and global health, and eight offered a minor or certification in global health. Fourteen institutions had a center for global health studies on campus. Eight PharmD programs required students to take a course related to global health. More than 50 programs offered an elective course related to global health. More than 50 institutions offered experiential education opportunities in global health including international advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs) or medical mission trips.

Programs varied not only by the amount of global health-related content in the curriculum, but also by the focus of each course. Courses ranged from pharmacists’ roles in and learning to successfully complete global medical mission trips to pharmacists’ roles in the history and epidemiology of diseases and treatment strategies worldwide.

Content Areas

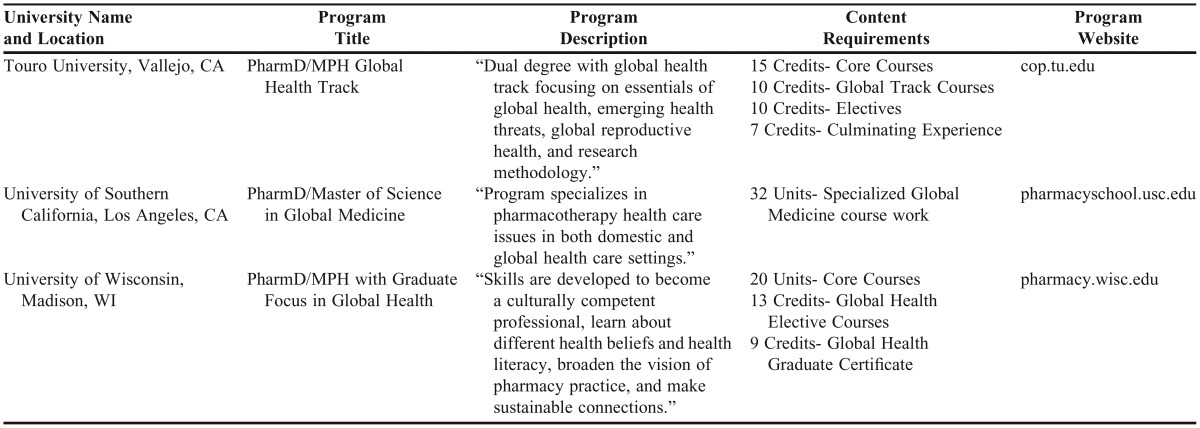

One school offered a dual master of science in global medicine. Two schools offered a dual degree with a global health track within their public health programs. Table 1 summarizes these programs’ structures. Six schools offered a specific global health track within their master of public health program as well as one program with a master of global health. While not specifically connected with the PharmD program, pharmacy students could potentially apply for entry into these programs. An additional 27 universities had PharmD programs that offered a master of public health degree; however, it was unclear how much global health content was incorporated into those programs.

Table 1.

Structure of Global Health Content in Master/PharmD Dual Degree Programs

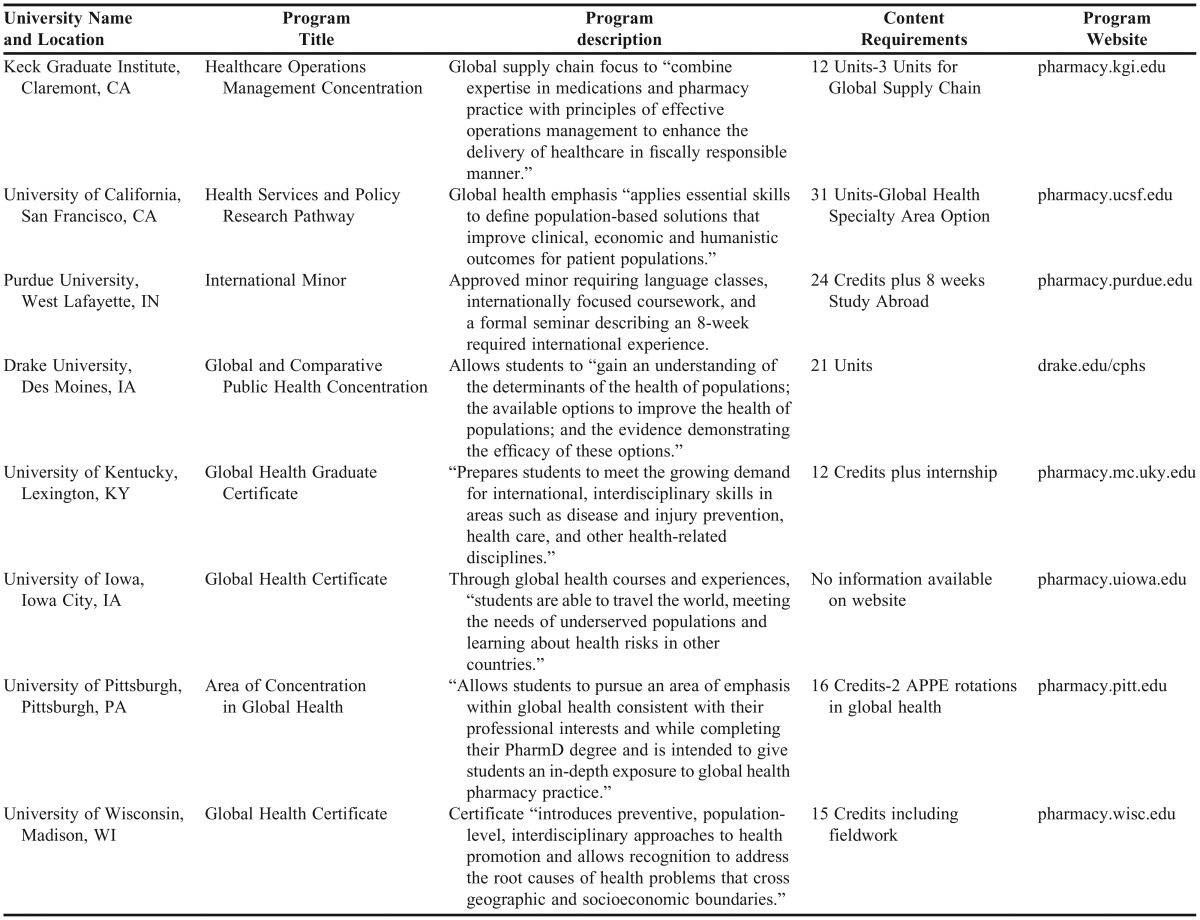

Eight programs offered either a concentration or certification in global health within the PharmD program (Table 2). Five programs offered global health certificates, but these programs were not listed specifically with the PharmD program.

Table 2.

Structure of Global Health Minor or Concentration in PharmD Programs

Fourteen institutions had a center for global health studies on campus. While this is not specific to pharmacy, some centers coordinated global pharmacy experiences with students, brought in lecturers, partnered with international pharmacy programs, and participated in global engagement through research, among other services. Other programs highlighted centers focused on interdisciplinary global health education and offered didactic courses as well as international experiences for all health care professions students. One program offered a global medicine program for the medical school and pharmacy school and included global health research, didactic education, and service activities. Other campuses had centers and global health groups for the university, but with no apparent elements specific to the PharmD program. It was unclear the degree to which pharmacy students were involved in those programs.

Eight PharmD programs had a global health course as a required component in their curriculum at the time of the Review. This included global health care delivery courses and travel medicine. These listings were mostly stand-alone courses, and there may be other programs that integrate global health concepts into required courses.

More than 50 schools offered a global health-related course as an elective within or directly approved by the PharmD program. While some courses were offered within the PharmD program and provided a more pharmacist-centric view, many others were from departments across the university outside of the PharmD program. The focus of the courses varied and included global health systems, medical missions, health disparities, international travel medicine, global topics seminars, didactic courses linked to global experiences, among others. Specific syllabi were unavailable for most courses; therefore, any comparison of core components in global health courses was not possible.

More than 50 schools offered international experiences within the PharmD program. International experiences were noted for APPEs or international experiences specific to pharmacy, such as medical mission trips or organized service trips. The most formalized opportunities linked to global health were those connected with didactic course work in that field. Some programs first had students participate in lectures and projects related to their planned experience, and the class culminated in the international application of studied topics. These didactic courses allowed for greater assessment of learning experiences.

DISCUSSION

With the growing recognition of the impact of globalization on health, many US institutions and organizations are placing a greater emphasis on global health issues. For example, the US Department of Health and Human Services has an Office of Global Affairs, which has created a Global Health Strategy to focus on those areas of synergy and priority for individuals in the United States and around the world.11 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a Center for Global Health, which organizes and implements the agency’s response to a number of global health issues.12 Healthy People 2020 also includes “Global Health” as new a new topic area.13

Within the profession of pharmacy, there is increased interest in global health as well. For example, a Global Health Practice and Research Network was established in the American College of Clinical Pharmacy in 2014.14 Within the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Public Health Special Interest Group, the Global Public Health Pharmacy Committee was formed in July 2014.

The 2013 Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes indicate that future pharmacists must be proficient in competencies integral to global health such as providing population-based care to diverse patient populations and recognizing and addressing disparities. Specifically, the learning outcomes related to “Promoter,” “Provider,” and “Includer” contain language related to global health.15 For example, the sample learning objective 2.3.4 (Promoter) requires students to “evaluate personal, social, economic, and environmental conditions to maximize health and wellness.” Example learning objectives in the Provider category include “assessing healthcare status and needs of a targeted patient population” and creating approaches to care based on those assessments, as well as “participating in population health management.” Sample learning objectives for section 3.5 (Includer) emphasize cultural sensitivity by being able to “recognize the collective identity and norms of different cultures without overgeneralizing” and “safely and appropriately incorporate patients’ cultural beliefs and practices into health and wellness care plans.” Coursework focused on global health exposes students to these issues. In addition, concepts associated with global health are found throughout the 2016 ACPE Accreditation Standards and Key Elements, especially section 2.4 (Population-based Care) and section 13.2 (Diverse Populations).16 The ACPE Guidance for Standards 2016 also indicates “global health” as a possible area of focus for PharmD programs.17 Universities are uniquely suited to impact global health issues,2 further providing cause to involve pharmacy students and their institutions in global health initiatives.

Through this Review, variation of global health education in PharmD curricula was observed. The findings mirror those of literature reviews of global health content in other health care professions educational programs. Liu et al’s 2015 review article focused on global health content in the education of health care professionals around the world (primarily medical students, residents, and doctors) found a lack of consistency across curricula and programs. Elective courses were most commonly utilized to convey global health content. Global health training, programs, or fellowships were the second most commonly utilized approach.18 Battat et al’s literature review of global health competencies in medical education revealed that while almost one-third of medical graduates in the United States and Canada participated in a global health experience, there was a need for a standardized global health curriculum.19

There are potential limitations to this Review. Because of the variation of each program’s webpage, a global health component may have been present under different search terms or outside the PharmD program’s offered courses that was not captured. Additionally, some subjectivity was involved in determining whether a course contained “global health” information. Global health content may have been integrated into another course but if the description in the course catalog was missing or not detailed, the course may not have been included in this Review.

CONCLUSION

Global health can be differentiated from public health and international health. No published papers comprehensively examine global health content in US PharmD curricula. A systematic review of US PharmD programs revealed a variety of inclusion of and focus on global health topics, similar to findings of other health care professional programs. Additional research of global health education within PharmD curricula and perhaps development of curricular framework should be considered to facilitate pharmacists’ competently assuming greater responsibilities in this area.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank John Rovers, PharmD, MIPH, who is John R. Ellis Distinguished Chair in Pharmacy Practice at Drake University, for his review and feedback on the draft manuscript. The authors have no external funding sources to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1993–1995. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valachovic RW. A small step for global health with big implications for dental education. American Dental Education Association (ADEA). http://www.adea.org/uploadedFiles/ADEA/Content_Conversion_Final/about_adea/ADEA_CP_December_2011.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2014.

- 3.Greysen R, Le P. Surveys find growing interest among US physicians in working to improve global health. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Human Capital Blog. http://www.rwjfleaders.org/news/surveys-find-growing-interest-among-us-physicians-working-improve-global-health. Accessed November 1, 2014.

- 4.Upvall MJ, Leffers JM. Global Health Nursing: Building and Sustaining Partnerships. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 2014.

- 5.Steeb DR, Joyner PU, Thakker DR. Exploring the role of the pharmacist in global health. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(5):552–555. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.13251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rovers J, Andreski M, Gitua J, Bagayoko A, DeVore J. Expanding the scope of medical mission volunteer groups to include a research component. Global Health. 2014;10:7. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Addo-Atuah J, Dutta A, Kovera C. A global health elective course in a PharmD curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(10):Article 187. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7810187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan M, Cain J, Romanelli F. A survey of international activity among colleges of pharmacy in the United States. Int J Pharm Educ Pract. 2012;8 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cisneros RM, Jawaid SP, Kendall DA, et al. International practice experiences in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(9):Article 188. doi: 10.5688/ajpe779188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Preaccredited and accredited professional programs of colleges and schools of pharmacy, Accreditation Counsel for Pharmacy Education (ACPE). https://www.acpe-accredit.org/shared_info/programssecure.asp. Accessed November 1, 2014.

- 11. Who we are, Office of Global Affairs, US Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.globalhealth.gov/about-us/index.html. Accessed November 1, 2014.

- 12. Global Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). http://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/index.html. Accessed November 1, 2014.

- 13. Healthy People 2020, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=16. Accessed September 26, 2014.

- 14.Global health practice research network receives ACCP board approval. American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP). http://www.accp.com/report/index.aspx?iss=0814&art=18. Accessed November 1, 2014.

- 15.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Educational Outcomes 2013. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE). http://www.aacp.org/documents/CAPEoutcomes071213.pdf. Accessed September 17, 2014.

- 16. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Standards 2016. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE). https://www.Acpe-Accredit.Org/Pdf/Standards2016final.Pdf. Accessed February 23, 2015.

- 17. Guidance for the accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Guidance for Standards 2016. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE). https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/GuidanceforStandards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed February 23, 2015.

- 18.Liu Y, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Wang J. Gaps in studies of global health education: an empirical literature review. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:25709. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.25709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Battat R, Seidman G, Chadi N, et al. Global health competencies and approaches in medical education: a literature review. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:94. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]