Abstract

Background

Toxicity, pathologic CR, and long term outcomes are reported for the neoadjuvant therapies assessed in a randomized phase II trial for operable esophageal adenocarcinoma, staged II-IVa by endoscopy/ultrasound (EUS).

Methods

86 eligible patients (pts) began treatment. Arm A preoperative chemotherapy was cisplatin (C) 30mg/m2 and irinotecan (I) 50 mg/m2 on days (d) 1, 8, 22, 29 of 45 Gy radiotherapy (RT) over 5 weeks. Adjuvant therapy was C 30 mg/m2 and I 65 mg/m2 d 1, 8 q21 days × 3. Arm B therapy was C 30 mg/m2 and paclitaxel (P) 50 mg/m2 d 1, 8, 15, 22, 29 with RT, followed by adjuvant C 75 mg/m2 and P 175 mg/m2 day 1 q21 days × 3. Stratification included EUS stage and performance status (PS).

Results

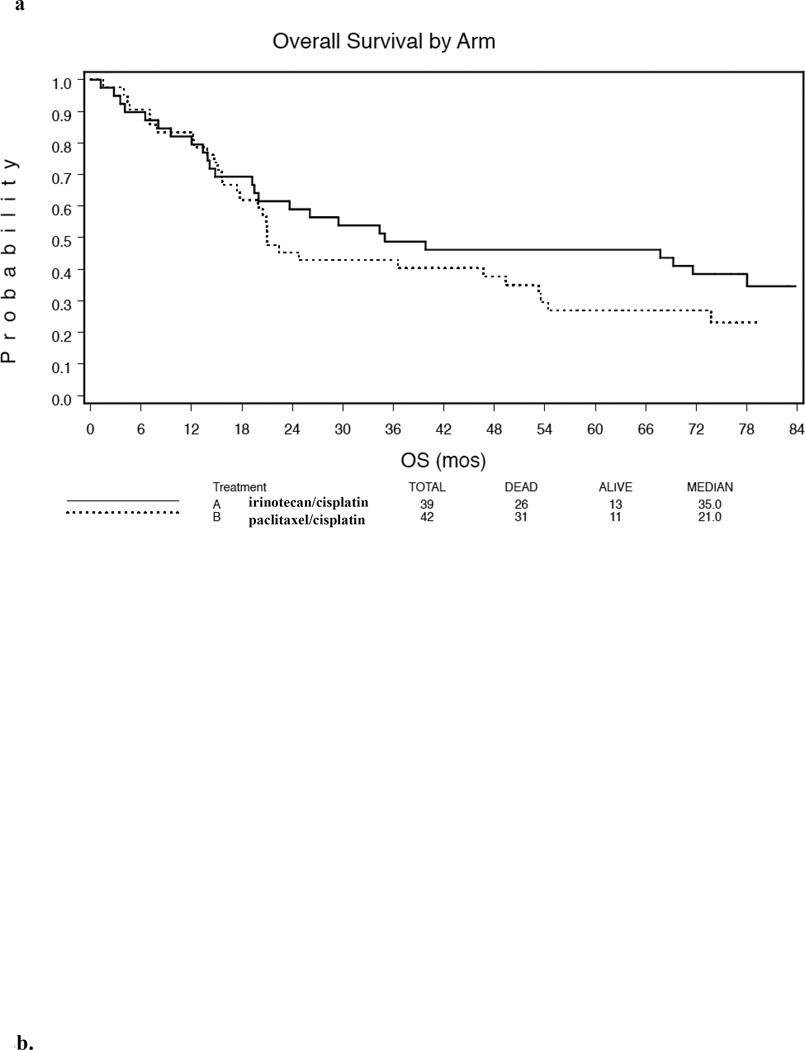

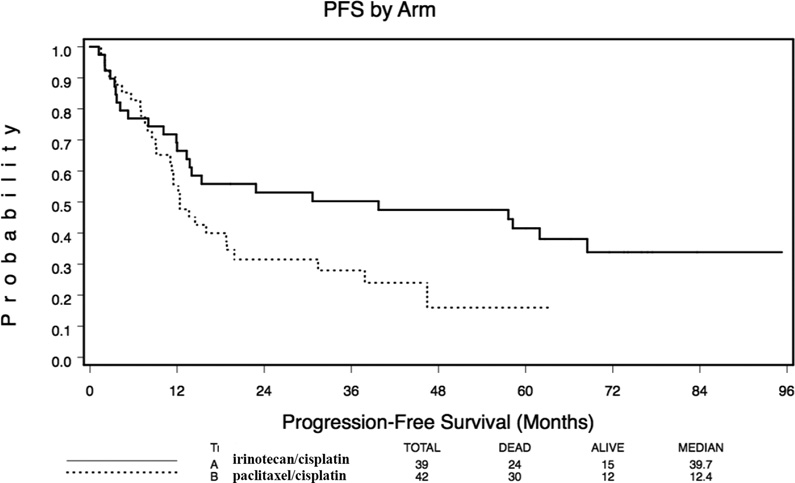

In Arm A, median overall survival (ms) was 35 m and the 5, 6, and 7 year survivals were 46%, 39%, and 35% whereas for arm B it was 21 m and 27%, 27%, and 23%, respectively.. Median PFS was 39.8 m with 3 Y PFS 50% for arm A and 12.4 months (p=.046) with 3 Y PFS 28% for arm B. Eighty percent of the observed incidents of progression occurred within 19 months. Survival did not differ significantly by EUS and PS strata.

Conclusions

Long term survival is similar for both arms and does not appear superior to results achieved with other standard regimens.

Summary

The long term survival results of an Oncology Group randomized phase II study assessing outcome of neoadjuvant preoperative paclitaxel/cisplatin/radiotherapy (RT) or irinotecan/cisplatin/RT in esophageal adenocarcinoma demonstrate that neither regimen achieved results that would justify study as potentially superior to other standard regimens.

Keywords: Esophageal neoplasm, adenocarcinoma, esophagogastric junction neoplasm, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, survival

The Oncology Group trial was a randomized phase II study in newly diagnosed resectable adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastro-esophageal junction testing preoperative paclitaxel/cisplatin/RT or irinotecan/cisplatin/RT followed by postoperative chemotherapy with the same drugs. There were data suggesting these regimens are active in esophageal cancer and safely administered along with thoracic radiotherapy(1–8). The initial results of the oncology group trial have been presented(9, 9)(9, 10)and we now report the details of these results along with long term efficacy and toxicity outcome data.. While a definitive randomized trial (11) has since confirmed improved survival using neoadjuvant paclitaxel/carboplatin/radiotherapy compared with surgery alone, there are no randomized data comparing this with other regimens.

The primary objective of the oncology group trial was to determine whether these regimens would result in an improved histopathologic complete response rate in comparison with historical results with preoperative 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU)/cisplatin/RT. Secondary objectives include evaluating toxicity, progression-free survival, overall survival, and tolerability of adjuvant chemotherapy. These data were to be used to inform the decision of whether either regimen was worthy of further study in a randomized trial. Comparison of these two regimens was not an objective.

Materials and Methods

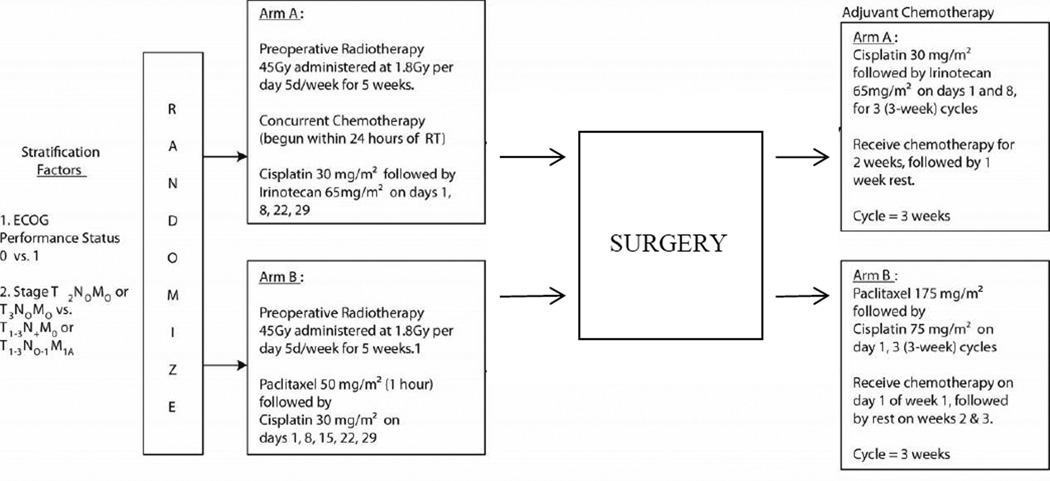

The schema of this randomized phase II trial is illustrated in Figure 1. Eligibility criteria included: Clinical stage T2N0M0, T3N0M0, T1–3N1M0 or T1–3N0–1M1A adenocarcinoma of the esophagus guided by the pathologic staging criteria of the AJCC 5.0 staging system, as determined by imaging studies and biopsy where appropriate. Celiac M1a disease (celiac nodal metastasis) was permitted if other eligibility criteria were met. Data from endoscopic ultrasound, endoscopy, and CT scan of the chest and upper abdomen were required for staging. If PET scanning, laparoscopy, or other relevant procedures were performed, the data were to be incorporated. Other criteria included: ECOG performance status 0–1; tumor considered surgically resectable (T1–3 but not T4); no intercurrent illness likely to prevent protocol therapy; patients having a history of a curatively treated malignancy must have been disease-free and have a survival prognosis > five years; required laboratory data obtained within 4 weeks of randomization included: granulocytes > 1,000/mm³;platelets > 100,000/mm³; calculated creatinine clearance (CRCL)> 60 mL/min.; and total serum bilirubin < 1.5 mg/dL.

Figure 1.

Schema of oncology trial.

Informed consent was obtained from all participates. Institutional review board or ethics committee approval was obtained.

Chemotherapy Details

Treatment Arm A: included concurrent neoadjuvant RT and cisplatin/irinotecan followed after surgery by adjuvant cisplatin/irinotecan. Treatment on Arm B included concurrent RT and paclitaxel/cisplatin followed by adjuvant paclitaxel/cisplatin. The timing and dosing of neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy is summarized in Figure 1.

Radiotherapy

Megavoltage radiotherapy (≥6 MV) using conventional and 3-D planning was permitted. Radiation was 5 days/week at 1.8 Gy/day to 45Gy. Simulation on a diagnostic quality RT simulator or CT simulator was required with oral contrast to confirm location of esophagus.

Normal tissue dose limits were: spinal cord dose must not exceed 40 Gy; lung (more than 2 cm outside the target volume) must not receive more than 40 Gy, and the entire heart should receive no more than 30 Gy with less than 50% of the organ receiving a maximum of 40 Gy.

Gross Tumor Volume (GTV): included the primary tumor and any involved nodes, determined using all available information, If tumor was present 2 cm above the carina (proximal esophagus), the supraclavicular nodal regions were included in the target volume. If the primary tumor was in the distal third of the esophagus, the target volume included the celiac nodal volume.

When conventional 2-D planning was used, it was sufficient to place the block edge approximately 2.0 – 2.5 cm from the lateral borders of the GTV and 2.0 – 2.5 cm from involved or treated lymph, and 5 cm superiorly and inferiorly from the primary tumor. The clinical target volume (CTV) for 3-D planning is defined as the GTV with a 5 cm margin superiorly and inferiorly beyond the primary tumor and with lateral borders 1.5 −2 cm beyond the primary tumor or esophagus. All involved lymph nodes should have at least a 1.5 −2 cm margin. A margin for set up error or patient movement is to be added to the Clinical Target Volume to create a PTV.

Surgical Resection

After neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and within 2 weeks prior to surgery, patients were required to undergo an evaluation including physical exam, CT imaging, and other tests as indicated. Surgical resection was intended to occur 4–6 weeks after initiation of therapy. The type of resection was left to the discretion of the operating surgeon; one field lymph node dissection was required.

Follow-up

Scheduled follow-up evaluations were to occur 1 month after completing all treatments, then every 3 months up to 2 years, every 6 months from 2–5 years of study entry and annually 6–10 years from study entry. These evaluations included a history and physical examination, CBC with differential, hepatic panel, creatinine, and CT of the chest and abdomen. Other tests including endoscopy were to be done as indicated.

End Points and Statistical Considerations

Forty-seven patients per arm were be accrued with a goal of 45 eligible patients per arm. For each randomized phase II arm the study had 91% power against the null hypothesis based on historical controls of 25% pCR (one-sided significance level 0.07) if the true rate is 45% and 7% if it is truly 25. A 45% pCR rate was considered to suggest that a regimen should undergo more definitive evaluation. Each arm had a planned two-stage design: if 6/22 eligible patients had pCR, additional patients will be entered onto the second stage. If there are 16 pCR among 45 eligible patients, then the treatment will be considered promising. However, initial response classifications were not reported correctly in some cases such that the early stopping rule was not utilized as intended.

The primary endpoint is pCR defined as no histopathological evidence of residual tumor in the esophageal and nodal specimen. Overall survival was defined as time from randomization to death from any cause. Progression-free survival was defined as the interval between randomisation and the earliest occurrence of disease progression resulting in primary (or pre-operative) unresectability of disease, locoregional recurrence (after completion of therapy), distant dissemination (during or after completion of treatment), or death without documented progression from any cause. Cases are censored at the date of last disease assessment without progression.

The toxicity of these regimens, as well as that of the adjuvant chemotherapy component, time to progression or recurrence, overall survival, and laboratory studies were secondary endpoints. Point estimates and exact confidence intervals were calculated for the primary endpoint of pathologic complete response (12). Fisher’s exact test (13) was used to compare toxicity between treatment arms. Kaplan-Meier (14) estimates were used for overall survival (OS) and progression- or recurrence-free survival (PFS). The log rank test (15)was used to test for differences in time-to-event end points. Standard landmark analysis methods were used to evaluate overall survival by pathologic complete response status with a landmark time of 4 months. All quoted p-values are two-sided except those for the primary endpoint of path CR which are one-sided per the original design.

Results

A total of 97 patients were accrued from 19 different participating sites from August 2002 through October 2004. Fifty patients were randomized to Arm A and 47 to Arm B. Three in Arm A and 1 in Arm B did not begin assigned therapy. Twelve patients were found to be ineligible at the time of data analysis (8 in Arm A, 4 in Arm B) generally because EUS (9 pts.) was not performed (9). In total, there were 81 eligible and treated patients, 39 on Arm A and 42 on Arm B. The median follow-up of surviving patients is 78 months. All 93 treated patients (47 arm A and 46 arm B) were evaluable for toxicity of neoadjuvant therapy, but only the 81eligible patients were assessed for pCR, PFS, and survival. Analysis of feasibility of adjuvant therapy included only eligible patients with a gross total resection (36 arm A, 33 arm B).Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics of eligible patients

| Arm A (n=39) | Arm B n=(42) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 89.7% (35) | 83.3% (35) |

| Caucasian | 97.4% (38) | 92.9% (77) |

| ECOG Performance status | ||

| 0 | 69.2 % (27) | 64.3% (27) |

| 1 | 30.8% (12) | 35.7% (27) |

| Median Age | 56.9 % (37.4–76.6) | 59.9 % (34.9–77.2) |

| Clinical Stage | ||

| T2N0M0 or T3N0M0 | 20.5% (8) | 28.6% (12) |

| T1-3N1M0 or T1-3N0- 1M1a |

79.5% (31) | 71.4% (30) |

| Location | ||

| Mid-Thoracic | 5.1% (2) | 7.1% (5) |

| Lower Thoracic | 33.2 % (13) | 50% (21) |

| GE Junction | 56.4 % (22) | 38.1% (38) |

| Unspecified | 4.8 % (2) | 4.8% (2) |

| Histologic grade | ||

| Well Differentiated | 2.6 % (1) | 2.4% (1) |

| Moderately Differentiated | 48.7 % (19) | 54.4% (21) |

| Poorly Differentiated | 46.2% (18) | 28.6% (12) |

| Unknown | 2.6 % (1) | 14.3% (6) |

On Arm A, 37 of 39 eligible and treated patients completed neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation as prescribed by protocol and on Arm B, 40 of the 42 eligible and treated patients completed neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy per protocol.

Toxicity

Toxicities reported during the neoadjuvant chemo/radiation (chemo/RT) for the 93 treated patients, regardless of eligibility, are shown in Table 2. Overall, 32 of the 47 treated patients on Arm A (68.1%, exact 95% CI [52.9%, 80.9%]) experienced worst toxicity of grade of 3 or higher including one treatment-related grade 5 toxicity (thrombosis/embolism). For those on arm B, 30 of the 46 treated patients experienced grade of 3 or higher (65.2%, exact 95% CI [49.7%, 78.7%]) toxicity. (p-value = 0.83, two sided Fisher’s exact test). Two patients in each arm did not complete neoadjuvant chemoradiation.

Table 2.

Grade 3 and higher toxicities occurring in greater than 5% of patients for either arm during neoadjuvant chemoradiation.

| ARM | A (n=47) | B (n=46) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Grade 3 (n) | % Grade 4 (n) | %Grade 3 (n) | %Grade 4 (n) | |

| Leucocytes | 26% (12) | 11% (5) | 28% (13) | 7% (3) |

| Neutrophils | 21% (10) | 11% (5) | 22% (10) | 7% (3) |

| Anorexia | 19% (9) | 2% (1) | 2% (1) | |

| Dehydration | 9% (4) | 9% (4) | ||

| Dysphagia | 13% (6) | 17% (8) | ||

| Nausea | 23% (11) | 13% (6) | ||

| Vomiting | 6% (3) | 2% (1) | 9% (4) | |

| Diarrhea | 9% (4) | 2% (1) | ||

| Hyponatremia | 0 | 9% (4) | ||

Seventy-two protocol eligible patients had surgery following neoadjuvant chemotherapy – 36 on both treatment arms. The reasons for not undergoing surgery in Arm A was disease progression 1 pt, death 1 pt, and refusal 1 pt whereas for arm B it was disease progression 2 pts, toxicity 2 pts, death 1 pt, and other disease complications 1 pt.

The most common surgical procedures were transhiatal resection (50%) and Ivor-Lewis thoracotomy (20%). At surgery, four patients were found to have metastatic disease, 2 in each arm.

A complete resection (R0) with all gross tumor removed and negative margins was achieved for all 36 eligible patients undergoing surgery in Arm A (100%), and for 33 of the 36 eligible patients in Arm B (91.7%). One death, Arm A (3%) occurred within 30 days of surgery.

For eligible patients who underwent complete resection, three cycles of adjuvant treatment were completed per protocol in 18 of the 36 patients on Arm A and 16 of the 33 completely resected patients on Arm B. Table 3 details the number of cycles and reasons for treatment termination among patients who did not complete 3 cycles of adjuvant therapy.

Table 3.

Completion of adjuvant chemotherapy Number of cycles and reasons for treatment termination among 36 Arm A patients (table 3a) and 33 ARM B patients (table 3b) who had complete resection after neoadjuvant therapy.

| a. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason for Treatment Termination Arm A |

adjuvant not initiated |

1 Adjuvant Cycle |

2 Adjuvant Cycle |

3 Adjuvant Cycle |

| Disease Progression | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Toxicity/Side Effects |

2 | 4 | 1 | |

| Death | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Refusal or withdrew | 0 | 4 | 1 | |

| Alternate therapy | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8/36 | 8/36 | 2/36 | 18/36 | |

| b. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason for Treatment Termination Arm B |

Adjuvant not initiated |

1 Adjuvant Cycle |

2 Adjuvant Cycle |

3 Adjuvant Cycles completed |

| Disease Progression | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Toxicity/Side Effects |

4 | 5 | 1 | |

| Death | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Refusal or withdrew | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Alternate therapy | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11/33 | 5/33 | 1/33 | 16/33 | |

During the adjuvant treatment period, 22/32 (68.8%, exact 90% CI [52.8%, 13 82.0%]) patients on arm A experienced a toxicity of grade three or higher (68.8%, exact 90% CI [52.8%, 13 82.0%]) as did 17/27 (63.0%, exact CI [45.4%, 78.3%]) on Arm B.

One patient in each arm was reported to have grade 3 or greater late radiation esophageal toxicity within the period of follow-up.

Pathology

Of the 39 eligible and treated patients on Arm A, 6 had a pCR (15.4%, exact, unadjusted 90% binomial CI [6.9%, 28.1%]). On Arm B, 7 of the 42 had a complete response (16.7%, exact, unadjusted 90% binomial CI [8.1%, 29.0%]).

Survival

Overall survival for treated eligible patients is summarized in Table 4 and Figure 2a. On Arm A, 22 of the 39 eligible and treated patients were known to have died and on Arm B, 31 of the 42 eligible and treated patients were known to have died by the last follow up date.

Table 4.

Long term outcome.

| Regimen | Median PFS (mos) |

2 Year PFS |

5 Year PFS |

Median Survival (mos) |

5 Year Survival |

6 Year Survival |

7 Year Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ArmA: Irinotecan/cisplatin/RT |

39.7 | 53% | 42% | 35 | 46% | 39% | 35% |

| Arm B: Paclitaxel/cisplatin/RT |

12.4 | 31% | 16% | 21 | 27% | 27% | 23% |

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival (Fig. 2a) and progression free survival (Fig 2b) for arm A (irinotecan/cisplatin/RT) and arm B (paclitaxel/cisplatin/RT) of oncology group trial.

Survival outcomes for the strata were not statistically different. For EUS stage stratum I (Stages T2N0M0 or T3N0M0) median survival is 36.5 months and 5 year survival is 43.6%. In the stage stratum II (Stages T1–3N1M0 or T1–3N0-1M1a), median survival is 24 months and 5 year survival 34.2% (p=0.64). Patients with PS 0, had median survival 35.0 months and 5 year survival of 37.2% whereas for those with PS 1, the outcomes were 20.4 months and 35.4% (p=0.59).

The median and 5-year survival rates for patients with a pathologic complete response were not reached and 58%, whereas for those with tumor in the pathologic specimen the outcomes were 23.9 months and 35%, respectively (p =0.082, landmark analysis, supplementary Figure 3).

Progression-Free Survival (PFS)

PFS is summarized in Table 4 and Figure 2b. Across both arms, with median follow-up of 83 months, 80% of the observed incidence of progression occurred within 19 months of enrollment.

Discussion

The primary objective was to estimate the pCR rate associated with each neoadjuvant chemoradiation regimen, and the results were not sufficient to reject the null hypothesis of a 25% pCR rate. Therefore neither regimen appeared superior to standard approaches. Pathologic complete response is a surrogate endpoint associated with better survival outcome. A meta-analysis exploring association of pCR with overall survival, including 22 clinical trials, suggested 3 and 5 year survival of 75% and 50% with pCR vs 29% and 22.6% without, including patients with adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.(16)which is similar to the outcomes observed in this study for those with and without pCR.

Although measurement of pCR may be a useful screening endpoint for the activity of new regimens, long term survival results are essential as it is not prospectively confirmed whether improved pathologic complete response at the primary site (which is also treated by radiotherapy and surgery) would actually lead to a superior survival outcome. Prognostic factors for survival of individual esophageal patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy are not well elucidated, such that heterogeneity of enrolled patients across phase II studies with differing proportions with adenocarcinoma may also play a role in varying reported pCR and overall survival results. Indeed, the prospective stratification factors used in this study of adenocarcinoma patients, including performance status and pretreatment clinically (with EUS) estimated nodal stage were not significantly predictive for survival as expected. Although this study was not well powered for subgroup analysis, we present this information as future trial designs should consider that pretreatment nodal stage may not be related to survival outcome, potentially resulting from inaccuracies in nodal staging(17) (18–20)(21)as well as the potential dominant effect of response to therapy on survival outcome regardless of nodal stage. In addition, pretreatment staging to determine eligibility may vary across trials affecting observed outcome. The oncology group trial did require EUS but did not require PET (22–24) scanning.

In this study, five year survival for neoadjuvant paclitaxel/cisplatin/RT was 27%, and 46% for irinotecan/cisplatin/RT (Figure 2a and Table 5). Five year survival results in trials predominantly enrolling adenocarcinoma patients reporting long term survival after treatment with neoadjuvant chemoradiation have varied from 22%-47% (3, 11, 25–29)Survival outcomes across studies do not appear to closely correlate with the observed proportion achieving a complete response in these individual trials which ranged from 22–47%, The pCR, toxicity, and survival outcomes we report do not appear superior to these other tested regimens, and are similar to the results that were reported with other phase I and II trials using the particular agents included in the oncology group trial.(3, 30)

At the time of the design and initiation of the oncology group trial, there was controversy about the benefit of noeadjuvant therapy for locally advanced esophageal cancer and the trial was in part motivated by the desire to identify an optimal regimen for definitive testing of this strategy. The survival and toxicity results of the oncology group trial may now be assessed in the context of the well-powered CROSS randomized evaluation of neoadjuvant paclitaxel/carboplatin/radiotherapy in both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma patients which was shown to have survival benefit when compared with surgery.(11) This regimen, which did not include adjuvant chemotherapy, appears better tolerated than those evaluated in the oncology group trial, and there is no suggestion that long term survival results in E1201 may be superior to the CROSS results. Recently median survival outcome for the adenocarcinoma population in the CROSS trial has been specifically reported and was improved from 27·1 months (13·0–41·2) in the surgery alone group to 43·2 months (24·9–61·4) in the neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy group, which may not be meaningfully different from the survival outcome observed with cisplatin/irinotecan/radiotherapy in E1201 . Demonstration of validity of PFS as a surrogate early endpoint associated with later survival may be particularly useful as trials are initiated of adjuvant targeted and immune therapies that are be administered after surgical determination of response. Although the oncology group trial was not designed to compare long term survival outcomes, the relatively favorable results observed in particular with irinotecan/cisplatin/RT could justify further investigation in adenocarcinoma patients of an irotecan and platinum containing regimens as a potentially appropriate alternative.

We also reported PFS, and it is intriguing to consider whether this could be a more appropriate surrogate endpoint for survival than pCR for phase II studies exploring new regimens.. A possible weakness of this study in assessing PFS is the lack of planned follow-up with endoscopy for detection of local recurrence. However data now available (31) suggest that the omission of endoscopy would not substantially affect assessment of disease free survival as only 5% of 518 patients treated with trimodality therapy had an isolated luminal recurrence and 90% of all initial recurrences occurred within 29 months of surgery. In our study with mature follow-up, 80% of observed first progression occurred within 19 months of enrollment providing additional support for the hypothesis that 2 year PFS may be an appropriate alternative to pCR as a phase II endpoint. Early PET response (24, 32–34)is also under prospective evaluation as an indicator of treatment activity that may be used to assess and guide therapy.

A secondary objective was to assess the feasibility of administering the same chemotherapy adjuvantly with the goal of decreasing metastatic failure. The benefit of adjuvant therapy after neoadjuvant therapy is uncertain. Favorable results have been achieved without the addition of adjuvant therapy (11, 35, 36) and the addition of additional cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy has not been beneficial (37). This remains a potentially important research issue as metastatic failure remains quite common (35),. Standard 5FU and platinum planned adjuvant therapy has generally been tolerated by only approximately half of patients. (28, 38, 39) Similarly, we found that only half of patients who were candidates for post-operative adjuvant paclitaxel/cisplatin or irinotecan/cisplatin were able to complete 3 cycles and up to a third of those having undergone complete resection did not receive any adjuvant chemotherapy. Better tolerated regimens, perhaps using targeted or immune agents, may be required to enable evaluation of adjuvant systemic therapy. For example, Randomized RTOG trial 1010(40) is testing neoadjuvant and adjuvant trastuzumab along with neoadjuvant paclitaxel/carboplatin/RT for HER2+ patients..

Our study evaluated two combined modality regimens of cisplatin/RT plus either paclitaxel or irinotecan in a parallel, randomized phase II design. Although both regimens resulted in observable pathologic complete responses, neither regimen met the predetermined criteria for further study of outcome sufficient to reject the null hypothesis of a pathologic complete response rate of 25%. The long term survival results which also do not appear superior to other standard regimens, although regimens based on these backbones may be used as an appropriate alternative and be included as the backbone of study of new agents. In addition, these regimens appeared fairly toxic in comparison with paclitaxel/carboplatin/RT now standardly utilized for operable adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.

National Clinical Trials Network trials designed to improve survival outcome have and will focus on other cytotoxic regimens such as flurouracil /oxliplatin(41), novel immune and targeted agents (42), adaptation of therapy using imaging biomarkers of response(34), and personalization of therapy based upon tumor molecular and genetic characteristics(40).

Supplementary Material

Progression free survival, by landmark analysis, for resected patients with or without pathologic complete response to either regimen of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.

These are the results, including long term survival outcome, of E1201 a randomized phase II trial of neoadjuvant preoperative paclitaxel/cisplatin/radiotherapy or irinotecan/cisplatin/RT in locally advanced esophageal adenocarcinoma with, for the two arms: The pathologic complete response were 17% and 15%, respectively, median survival: 21 months and. 35 months, and 7 year survival: 23% vs. 35%. The results did not appear superior to other regimens, and implications for therapy and future trial design are discussed.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (Robert L. Comis, M.D. and supported in part by Public Health Service Grants CA23318, CA66636, CA21115, CA16116, CA14958, CA13650, CA17145 and from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services. Its content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no disclosures.

References

- 1.Ajani JA, Ilson DH, Daugherty K, et al. Activity of taxol in patients with squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1086–1091. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.14.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Philip PA, Zalupski MM, Gadgeel S, et al. A phase II study of carboplatin and paclitaxel in the treatment of patients with advanced esophageal and gastric cancer. Semin Oncol. 1997;24:S19,86–S19-88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ilson DH, Minsky BD, Ku GY, et al. Phase 2 trial of induction and concurrent chemoradiotherapy with weekly irinotecan and cisplatin followed by surgery for esophageal cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:2820–2827. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin L, Hecht JR. A phase II trial of irinotecan in patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction. Proceedings of American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choy H, Chakravarthy A, Devore RF, 3rd, et al. Weekly irinotecan and concurrent radiation therapy for stage III unresectable NSCLC. Oncology (Williston Park) 2000;14:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oka M, Fukuda M, Kuba M, et al. Phase I study of irinotecan and cisplatin with concurrent split-course radiotherapy in limited-disease small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:1998–2004. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yokoyama A, Kurita Y, Saijo N, et al. Dose-finding study of irinotecan and cisplatin plus concurrent radiotherapy for unresectable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer [seecomments. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:257–262. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilson DH, Bains M, Kelsen DP, et al. Phase I trial of escalating-dose irinotecan given weekly with cisplatin and concurrent radiotherapy in locally advanced esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2926–2932. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleinberg LR, Powell ME, Forastiere AA, et al. E1201: An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) randomized phase II trial of neoadjuvant preoperative paclitaxel/cisplatin/RT or irinotecan/cisplatin/ RT in endoscopy with ultrasound (EUS) staged adenocarcinoma of the esophagus [abstract] J Clin Onol. 2008;26(suppl):4532. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleinberg LR, Catalano PJ, Forastiere AA, et al. Long term survival and disease free survival outcome of E1201: An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) randomized phase II trial of neoadjuvant preoperative paclitaxel/cisplatin/radiotherapy (RT) or irinotecan/ cisplatin/RT in endoscopy with ultrasound (EUS) staged esophageal adenocarcinoma [abstract] Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35:186. [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2074–2084. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkinson EN, Brown BW. Confidence limits for probability of response in multistage phase II clinical trials. Biometrics. 1985;41:741–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox DR. Analysis of binary data. London: Methuen and Co.; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1958;53:457–481. 53:457=481. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peto R, Peto J. Asymptomatically efficient rank invariant test procedure. journal of the royal statistical society A, 1972; 135:185-206. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1972;135:185–296. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheer RV, Fakiris AJ, Johnstone PA. Quantifying the benefit of a pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in the treatment of esophageal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80:996–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cordin J, Lehmann K, Schneider PM. Clinical staging of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2010;182:73–83. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-70579-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Levy MJ, Clain JE, Routine vs, et al. selective EUS-guided FNA approach for preoperative nodal staging of esophageal carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Wang L, Burgart L, et al. Occult lymph node metastases as a predictor of tumor relapse in patients with node-negative esophageal carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1815–1821. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crabtree TD, Kosinski AS, Puri V, et al. Evaluation of the reliability of clinical staging of T2 N0 esophageal cancer: A review of the society of thoracic surgeons database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.03.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stiles BM, Mirza F, Coppolino A, et al. Clinical T2-T3N0M0 esophageal cancer: The risk of node positive disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(6):491. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.004. discussion 496–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Purandare NC, Pramesh CS, Karimundackal G, et al. Incremental value of 18F–FDG PET/CT in therapeutic decision-making of potentially curable esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nucl Med Commun. 2014;35:864–869. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong R, Walker-Dilks C, Raifu A. Evidence-based guideline recommendations on the use of positron emission tomography imaging in oesophageal cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2012;24:86–104. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munden RF, Macapinlac HA, Erasmus JJ. Esophageal cancer: The role of integrated CT-PET in initial staging and response assessment after preoperative therapy. J Thorac Imaging. 2006;21:137–145. doi: 10.1097/00005382-200605000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forastiere AA, Orringer MB, Perez-Tamayo C, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation followed by transhiatal esophagectomy for carcinoma of the esophagus: Final report. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1118–1123. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.6.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urba SG, Orringer MB, Turrisi A, et al. Randomized trial of preoperative chemoradiation versus surgery alone in patients with locoregional esophageal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:305–313. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Posner MC, Gooding WE, Lew JI, et al. Complete 5-year follow-up of a prospective phase II trial of preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal cancer. Surgery. 2001;130(6):620. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116673. discussion 626–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinberg L, Knisely JP, Heitmiller R, et al. Mature survival results with preoperative cisplatin, protracted infusion 5-fluorouracil, and 44-gy radiotherapy for esophageal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:328–334. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tepper J, Krasna MJ, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Phase III trial of trimodality therapy with cisplatin, fluorouracil, radiotherapy, and surgery compared with surgery alone for esophageal cancer: CALGB 9781. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1086–1092. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim DW, Blanke CD, Wu H, et al. Phase II study of preoperative paclitaxel/cisplatin with radiotherapy in locally advanced esophageal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taketa T, Correa A, Sudo K. Customizing surveillance of patients with esophageal or esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma (E-EGA) after trimodality therapy (TMT) J Clin Oncol. 2013;(31 suppl) abstract 4085. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lordick F, Ott K, Krause BJ, et al. PET to assess early metabolic response and to guide treatment of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction: The MUNICON phase II trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:797–805. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duong CP, Demitriou H, Weih L, et al. Significant clinical impact and prognostic stratification provided by FDG-PET in the staging of oesophageal cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:759–769. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-0028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CALGB 80803: Phase II randomized study of PET scan-directed combined modality therapy in patients with esophageal cancer receiving FOLFOX-6 chemotherapy versus paclitaxel and carboplatin.

- 35.Oppedijk V, van der Gaast A, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Patterns of recurrence after surgery alone versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy and surgery in the CROSS trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:385–391. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allum WH, Stenning SP, Bancewicz J, et al. Long-term results of a randomized trial of surgery with or without preoperative chemotherapy in esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5062–5067. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alderson D, Langley R, Nankivell M. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for resectable oesophageal and junctional adenocarcinoma: Results from the UK medical research council randomised OEO5 trial (ISRCTN 01852072) J Clin Oncol 33, 2015 (suppl; abstr 4002) 2015;33 abstr 4002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herskovic A, Martz K, al-Sarraf M, et al. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in patients with cancer of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1593–1598. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206113262403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelsen DP, Winter KA, Gunderson LL, et al. Long-term results of RTOG trial 8911 (USA intergroup 113): A random assignment trial comparison of chemotherapy followed by surgery compared with surgery alone for esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3719–3725. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.RTOG 1010: A phase III trial evaluating the addition of trastuzumab to trimodality treatment of Her2-overexpressing esophageal adenocarcinoma.

- 41.Leichman LP, Goldman BH, Bohanes PO, et al. S0356: A phase II clinical and prospective molecular trial with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and external-beam radiation therapy before surgery for patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4555–4560. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.7490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ilson DH, Moughan J, Suntharalingam M. RTOG 0436: A phase III trial evaluating the addition of cetuximab to paclitaxel, cisplatin, and radiation for patients with esophageal cancer treated without surgery. J Clin Oncol 32:5s, 2014 (suppl; abstr 4007) 2014;32 abstract 4007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Progression free survival, by landmark analysis, for resected patients with or without pathologic complete response to either regimen of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.