Abstract

The enhanced CO2 release of illuminated leaves transferred into darkness, termed “light enhanced dark respiration (LEDR)”, is often associated with an increase in the carbon isotope ratio of the respired CO2 (δ13CLEDR). The latter has been hypothesized to result from different respiratory substrates and decarboxylation reactions in various metabolic pathways, which are poorly understood so far. To provide a better insight into the underlying metabolic processes of δ13CLEDR, we fed position-specific 13C-labeled malate and pyruvate via the xylem stream to leaves of species with high and low δ13CLEDR values (Halimium halimifolium and Oxalis triangularis, respectively). During respective label application, we determined label-derived leaf 13CO2 respiration using laser spectroscopy and the 13C allocation to metabolic fractions during light–dark transitions. Our results clearly show that both carboxyl groups (C-1 and C-4 position) of malate similarly influence respiration and metabolic fractions in both species, indicating possible isotope randomization of the carboxyl groups of malate by the fumarase reaction. While C-2 position of pyruvate was only weakly respired, the species-specific difference in natural δ13CLEDR patterns were best reflected by the 13CO2 respiration patterns of the C-1 position of pyruvate. Furthermore, 13C label from malate and pyruvate were mainly allocated to amino and organic acid fractions in both species and only little to sugar and lipid fractions. In summary, our results suggest that respiration of both carboxyl groups of malate (via fumarase) by tricarboxylic acid cycle reactions or by NAD-malic enzyme influences δ13CLEDR. The latter supplies the pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction, which in turn determines natural δ13CLEDR pattern by releasing the C-1 position of pyruvate.

Keywords: fumarase, LEDR, malic acid, malic enzyme, pyruvic acid, respiration, stable carbon isotopes, TCA cycle

Introduction

Transferring light-acclimated leaves into darkness lead to rapid changes in various metabolic processes, causing halt of any photosynthetic activity and increased respiration rates (Florez-Sarasa et al., 2012; Griffin and Turnbull, 2012). During such light–dark transitions, leaves show enhanced O2 consumption (Stone and Ganf, 1981; Azcon-Bieto et al., 1983) concurrently with enhanced CO2 release (Hill and Bryce, 1992; Atkin et al., 1998). The extent of this increasing CO2 emissions after darkening, defined as “light enhanced dark respiration (LEDR)”, depends on light intensity of the previous photoperiod and lasts about 20–30 min, with a maximum CO2 release within the first 5 min (Atkin et al., 1998; Griffin and Turnbull, 2012). LEDR does not interfere with the post-illumination burst, which occurs within <20 s after darkening and is related to photorespiratory glycine oxidation (Atkin et al., 1998).

During LEDR the carbon isotope ratio of leaf-respired CO2 (δ13CLEDR) is also changing, showing a strong initial increase which is followed by a progressive decrease (Werner et al., 2009; Wegener et al., 2010; Lehmann et al., 2016). Such a δ13CLEDR pattern was also observed under natural conditions in a grassland ecosystem (Barbour et al., 2011), demonstrating that this phenomenon has also potential relevance at higher scales. δ13CLEDR is also relevant for cases when leaf dark-respired CO2 is sampled from light-acclimated leaves. Many field (Prater et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2009; Dubbert et al., 2012) and laboratory experiments (Wegener et al., 2010; Lehmann et al., 2015, 2016) have shown that δ13CLEDR is often less negative compared to respiratory substrates. The 13C enrichment in leaf-respired CO2 during LEDR progressively increases during daytime, which has been shown to be strongly related to the cumulative assimilation of CO2 (Hymus et al., 2005). Moreover, δ13CLEDR may retain information of plant internal carbon allocation and was observed to differ among plant functional groups (Wegener et al., 2010, 2015): evergreen, slow-growing or aromatic species showed a very high increase in δ13CLEDR during the day (up to 14.8‰), while fast-growing, non-aromatic herbaceous species showed no or a small increase in δ13CLEDR (Lehmann et al., 2016). However, although leaf dark-respired CO2 is a potential and easy accessible indicator for leaf internal metabolic processes, high-resolution measurements of δ13CLEDR are scarce (Werner et al., 2009; Jardine et al., 2014). Also the interpretation of this data is still difficult, since its respiratory substrates and associated enzymatic reactions are not fully understood so far (Werner and Gessler, 2011; Ghashghaie and Badeck, 2014).

δ13CLEDR may depend on the heterogeneous intramolecular isotope distribution within respiratory substrates (e.g., sugars). For instance, the C-3 and C-4 positions of glucose are enriched in 13C compared to other positions of the same molecule (Rossmann et al., 1991; Gilbert et al., 2012), probably due to an equilibrium isotope effect of the aldolase reaction (Gleixner and Schmidt, 1997). On the one hand, 13C enriched positions of glucose molecules broken down during glycolysis are relocated to the C-1 position of pyruvate molecules and can be released as CO2 by the mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase (mtPDH) reaction in the dark, influencing δ13CLEDR. Additionally, the chloroplast pyruvate dehydrogenase (cpPDH) reaction can consume photosynthetically produced pyruvate in the light (Tovar-Mendez et al., 2003). On the other hand, 13C depleted positions of glucose molecules relocated in the acetyl-CoA residue (C-2 and C-3 position of pyruvate) can be used in dark for respiration or for biosynthesis of various substrates such as amino acids, lipids, or organic acids (Tcherkez et al., 2009). Leaf feeding studies showed that the extent of 13CO2 respiration from 13C-1 pyruvate was higher than from pyruvate molecules labeled in other positions (Tcherkez et al., 2005, 2009). Other studies indicated that species-specific differences in 13CO2 respiration from 13C-1 pyruvate might explain the species-specific differences in δ13CLEDR (Priault et al., 2009; Wegener et al., 2010).

Furthermore, also other respiratory substrates are expected to have a significant influence on δ13CLEDR. A study by Gessler et al. (2009) showed a clear malate breakdown shortly upon darkening in Ricinus communis, estimating that malate decarboxylation represents 22% of the respired CO2 during LEDR. The role of malate during LEDR was supported by a more recent study from Lehmann et al. (2015) who identified malate as an important and relatively 13C enriched respiratory substrate in Solanum tuberosum. The biochemical link between malate and δ13CLEDR was explained with an anaplerotic flux via the PEPC reaction that replenishes TCA cycle intermediates, which are withdrawn for biosynthetic use (Werner et al., 2011; Lehmann et al., 2015). This is in line with other studies, suggesting that organic acids such as malate derived from PEPC may accumulate in leaves under illumination due to inhibition of enzymatic reactions in the mitochondrion such as fumarase, NAD-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase (mtIDH), and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (OGDH) (Werner et al., 2011; Eprintsev et al., 2016), causing an open and only partially active TCA cycle (Hanning and Heldt, 1993; Tcherkez et al., 2005; Araújo et al., 2012). Thus, a rapid breakdown of malate via TCA recycling in the dark may be in support of enhanced CO2 release during LEDR and simultaneous increases in δ13CLEDR, but also other individual organic acids might be involved (Lehmann et al., 2016). In addition, malate derived from PEPC via oxaloacetate and the malate dehydrogenase reaction (MDH) is expected to be enriched in 13C at the C-4 position compared to other molecule positions (Melzer and O’Leary, 1987; Savidge and Blair, 2004), since PEPC fixes HCO3- with a net isotope fractionation of -5.7‰ (with respect to dissolved CO2; Farquhar, 1983). Thus, decarboxylation of this malate molecule position in the dark by the previously light-inhibited mitochondrial NAD-ME reaction, as observed in Hordeum vulgare protoplasts (Hill and Bryce, 1992; Igamberdiev et al., 2001), might also contribute to the observed increase in δ13CLEDR (Barbour et al., 2007; Gessler et al., 2009; Werner et al., 2011; Tcherkez et al., 2012), although NAD-ME might fractionate against 13C by about 20‰ as observed in Crassula plants (Grissom et al., 1987). Direct experimental evidence for respiration of malate is still missing and thus the respiratory and metabolic fate of the carboxyl groups (C-1 and C-4 position) of malate during light–dark transitions and their influence on δ13CLEDR remains to be proven.

Here, we hypothesize that δ13CLEDR is determined by decarboxylation of malate and pyruvate, but we expect position-specific and species-specific differences in the intensity of these reactions. Our main objectives are (1) to determine if and to which extent malate and pyruvate influence respiration during light–dark transitions, (2) to identify position- and species-specific differences of both substrates in respiration, (3) and in 13C allocation to metabolic fractions. Therefore, we fed different position-specific 13C-labeled malate (13C-1, 13C-4) and pyruvate (13C-1, 13C-2) via the xylem stream to leaves of two different species, with known high (Halimium halimifolium) and low (Oxalis triangularis) increases in δ13CLEDR. We measured the RLabel during light–dark transitions on-line with high time-resolved isotope laser spectroscopy and determined the 13C allocation to leaf metabolic fractions using isotope ratio mass spectrometry.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

We chose species from two functional groups as described in Priault et al. (2009): the evergreen Mediterranean shrub Halimium halimifolium L. and the fast-growing herb Oxalis triangularis A. St.-Hil. While H. halimifolium plants were potted in 5 L pots filled with sand (plant height 40–60 cm), O. triangularis plants were potted in 1 L pots with potting soil (plant height 10–15 cm). Both species have a similar LEDR duration, with the main CO2-peak declining within approximately 30 min after darkening followed by a slow decrease for another 30 min (Lehmann et al., 2016). All plants were grown under controlled conditions in walk-in climate chambers with a constant temperature of 23°C and relative humidity of about 60% during a 12 h light period (09:00–21:00 h) with a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of about 770 μmol m-2 s-1.

Acquiring of Position-Specific 13C-Labeled Malate and Pyruvate

13C-1 and 13C-4 labeled malate substrates were synthesized with coupled enzymatic reactions modified after Rosenberg and O’Leary (1985): 4.4 mmol NADH disodium salt (Roth, Arlesheim, Switzerland), 2.8 mmol 2-oxoglutarate (Sigma–Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland), 2.9 mmol 13C-1 or 13C-4 aspartate (99%, both Sercon, Crewe, UK), and 100 U glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminase (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) were dissolved in 50 ml of 0.2 M KH2PO4 (pH 7.5) buffer solution. Subsequently, pH 7.5 was readjusted with 11 ml of 1 M KOH and the reaction solution continuously stirred for 10 min at 25°C. The enzymatic reaction was then started by adding 100 U of a malate dehydrogenase solution (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Aliquots of the reaction solution were analyzed at 340 nm with a 96-well microplate reader (ELx800, BioTek, Luzern, Switzerland) to follow the NADH degradation, which ended after 2 h. Thereafter, all enzyme residues of the reaction solution were removed with pre-washed centrifugation filters with a molecular weight cut-off of 5000 da (Vivaspin 15R, 5000 MWCO HY, Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). Subsequently, aliquots of the reaction solutions were separated by ion exchange chromatography using Dowex material (see below). Malate containing fractions of the reaction solution were eluted from Dowex 1X8 columns with 40 ml 1 M HCl, frozen (-20°C), and lyophilized. Finally, pellets were re-suspended in deionized water and aliquots merged to one labeling solution. Synthesis of 13C-1 and 13C-4 labeled malate was verified by NMR (Supplementary Figure S1), showing the appropriate position-specific 13C-labeling, with only marginal impurities. 13C-1 pyruvate (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Tewksbury, MA, USA) and 13C-2 pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland) were commercially acquired.

Experimental Setup for Laser-Based On-line Measurements

Leaf 13CO2 respiration was determined on-line by a cavity ringdown laser spectrometer (CRDS, G2101-I, Picarro, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The CRDS system holds a wavelength monitor, which quantifies the spectral signature of CO2 isotopologs with a time-based measurement technique in an optical cavity at 1603 nm. Temperature and pressure within the measurement cavity were controlled at 40°C and 140 Torr, respectively. Data were monitored continuously with a temporal resolution of 0.75 Hz, thus 45 single values were averaged per minute for further analysis.

For all laser-based on-line gas exchange measurements, a transparent 500 ml glass cylinder, with one inlet and one outlet, was used as a plant chamber that enclosed twigs or leaves. Inlets of all plant chambers were flushed continuously with fresh air at a molar mass flow rate of 640 μmol s-1. Outlets were connected via Teflon tubing to the CRDS, thus determining 13CO2 of sample gas (13CO2SG). For 13CO2 measurements of reference gas (13CO2RG), an empty plant chamber of the same size was used. The open bottom side of all plant chambers was sealed with airtight non-fractionating plastic foil (FEP, 4PTFE, Stuhr, Germany). Before and after each 13CO2SG measurement of about 40–60 min, 13CO2RG was analyzed for about 10–20 min. 13CO2RG concentrations (μmol 13CO2 mol-1) were interpolated with a generic regression equation (y = mx + b) for the period of 13CO2SG measurements. Switching between 13CO2SG and 13CO2RG was done manually by re-plugging the CRDS Teflon tubing. 13CO2 readings were discarded within the first minutes after switching between gases. Compressed air from gas cylinders (4.4 ppm 13CO2, Riessner-Gase, Lichtenfels, Germany) was analyzed two times per day for about 10–20 min, showing a total variation of SD ≤ 0.008 ppm in 13CO2, thus no significant drift during the experiments occurred.

During the experiments, one twig with leaves of H. halimifolium or three leaves of O. triangularis still attached to the potted plant were enclosed in the plant chambers. The system was sealed with airtight plastic foil around chamber and stalk of the twigs or leaf petioles. Respiration rates of twigs and leaves were measured in the first 10–20 min to determine the non-labeled leaf 13CO2 respiration. Subsequently, twigs or leaves within the plant chamber were detached from the plant by cutting and immediately transferred into tap water and cut again under water to prevent air embolism in the xylem. The truncated ends of these twigs and leaves were then directly transferred in reaction vials, which contained the 13C-labeling solutions and were placed outside of the plant chamber. The 13C-labeling solutions were refilled during the experiments to provide continuously 13C-labeled substrates to the plant. Subsequently, 13CO2 respiration was measured for about 20 min in the light and 20 min in the dark by covering the plant chamber with a light-impermeable cloth. Three to five replicates were measured with each position-specific 13C-labeled substrate for each species. Leaf area of all leaves was determined after each experiment.

Tests with dilution series of 13C-labeled malate (13C-1, 13C-4) in H. halimifolium and in O. triangularis showed that 2 mM malate solutions produced sufficient 13CO2 emissions and thus this concentration was applied for all further experiments. For 13C-labeled pyruvate (13C-1, 13C-2), 6 mM solutions yielded the best signals. Differences in molar strength by a factor of three for the labeling solutions were accounted for when computing the RLabel and the ΔLabel (see Eqs 1 and 3). All 13C-labeled substrates were purely provided without isotopic dilution by unlabeled substrates. No significant changes in total CO2 respiration (12CO2 + 13CO2) occurred after feeding plants of both species with any position-specific 13C-labeled substrate, indicating that the applied concentrations of malate and pyruvate solutions had no significant effect on respiratory CO2 emissions. Transpiration rates were monitored by CRDS and checked to be in steady-state during substrate application. Mean transpiration rates during the light in H. halimifolium (1.06 ± 0.13 mmol m-2 s-1) and O. triangularis (0.89 ± 0.04 mmol m-2 s-1) showed no significant differences for all 13C-labeled substrates (both species, p > 0.05; ANOVA + Tukey-HSD), indicating that absorption rates were similar for all experiments in both species. Air temperature and PPFD within the plant chambers during the measurements was about 29°C and 720 μmol m-2 s-1, respectively.

Equation 1 was used to calculate RLabel, which was corrected for non-labeled leaf 13CO2 respiration:

| (1) |

where, f is the molar mass flow rate (μmol s-1), a the leaf area (m2), 13CO2SG and 13CO2RG the sample and the reference gas (μmol 13CO2 mol-1), and RNL the non-labeled leaf 13CO2 respiration (μmol 13CO2 mol-1).

Eq. 2 was used to calculate sums of 13CO2 respiration (∫ R) for a distinct period:

| (2) |

where n is the number of seconds in the light or in the dark.

Isotopic Analysis of Leaf Metabolic Fractions

Similar to the above-described experiments regarding respiration, an additional experiment was carried out to determine 13C allocation of position-specific 13C-labeled malate and pyruvate to metabolic fractions. One twig with leaves of H. halimifolium or three leaves of O. triangularis were placed into reaction vials containing one of the four different position-specific 13C-labeled substrates or deionized water to correct for non-labeling conditions. To trace the 13C allocation in leaf metabolic fractions during light dark-transitions, leaves of both species were harvested after 20 min in the light, as well as after 40 min (20 min in the light and 20 min in the dark), using additional twigs/leaves of the same plants. Subsequently, leaves from both species were immediately frozen with liquid N2, lyophilized, and milled to a fine powder with a ball mill. 100 mg of the plant powder was dissolved in 1.5 ml MCW (methanol, chloroform, water, 12:3:5, v:v:v) and boiled for 30 min at 70°C in a water bath to extract the water soluble fraction, as described in Richter et al. (2009; method I2). Samples were centrifuged for 2 min at 10000 × g, and 800 μl of the supernatant were transferred into a new reaction vial. After adding 250 μl chloroform, samples were shaken intensively and centrifuged for 2 min at 10000 × g. For the isotopic analysis of lipids, aliquots of the lower chloroform phase were carefully taken to avoid contamination with the upper phase and transferred into tin capsules. In a next step, 1.2 ml of the upper phase was transferred into a new reaction vial, mixed roughly with 500 μl chloroform, and centrifuged 2 min at 10000 × g. Finally, 1 ml of the upper phase, which contained the total hydrophilic fraction of the extract, was transferred into a new reaction vial and stored at -20°C.

The hydrophilic fraction was further separated to sugar, amino acid, and organic acid fractions with ion-exchange chromatography using Dowex material (100–200 mesh, Sigma–Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland; see Richter et al., 2009). In brief, different Dowex materials were conditioned with 1M HCL (Dowex 50WX8) or with 1M sodium formate (Dowex 1X8) and transferred to columns, which were placed above each other on a rack. Columns were extensively prewashed with deionized water to fully remove potential carbon residues. Subsequently, the hydrophilic fraction was added and the neutral, sugar containing fraction was eluted with 35 ml deionized water, while the flow-through was collected in 50 ml falcon tubes. The amino acid fraction was absorbed by Dowex 50WX8 and eluted with 30 ml 3M NH3, while the organic acid fraction was absorbed by Dowex 1X8 and eluted with 35 ml 1M HCL. Eluates of all three fractions were frozen at -20°C, lyophilized, and the pellets re-suspended in deionized water. Subsequently, aliquots of the fractions were transferred into tin capsules. All capsules (including lipids) were oven-dried at 60°C and δ13C values analyzed with an EA-IRMS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Measurements and referencing for the IRMS were done after Werner et al. (1999) and Werner and Brand (2001). The IRMS long-term precision of a quality control standard (-43.11‰, Caffeine, Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) was ≤0.15‰ (SD).

Equation 3 was used to calculate the ΔLabel in leaf metabolic fractions, which was corrected for δ13C values under non-labeling conditions:

| (3) |

where δ13CL are the δ13C values in leaf metabolic fractions (lipids, sugars, amino and organic acids) of plants fed with position-specific 13C-labeled substrates, and δ13CNL is the mean δ13C value of the corresponding leaf metabolic fraction under non-labeling conditions.

Statistics

General linear models were performed to test for position-specific, species-specific, and temporal differences in ∫ R and ΔLabel of different metabolic fractions. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey-HSD post hoc tests were used to show differences in ΔLabel of different metabolic fractions for each 13C-labeled substrate. Unless otherwise specified, means and standard errors are given. All statistical analyses were performed in R (version 3.1.3; R Core Team, 2015).

Results

Leaf 13CO2 Respiration of Different Position-Specific 13C-Labeled Substrates and Species

To identify the respiratory substrates and enzymatic reactions, determining the species-specific differences in δ13CLEDR at natural isotope abundances in H. halimifolium (high increases in δ13CLEDR) and in O. triangularis (low increases in δ13CLEDR), we fed those plants with different 13C-labeled malate and pyruvate substrates, expecting position- and species-specific differences in 13CO2 respiration during light–dark transitions.

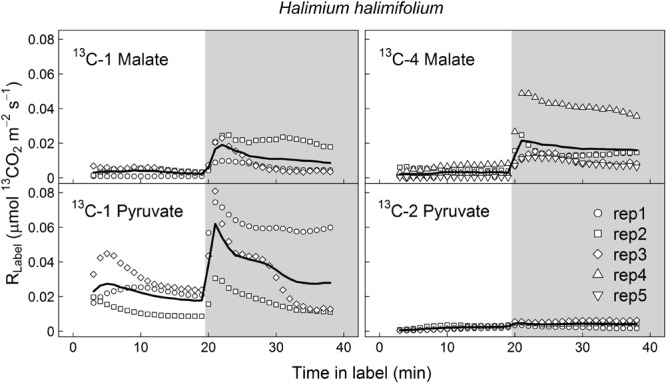

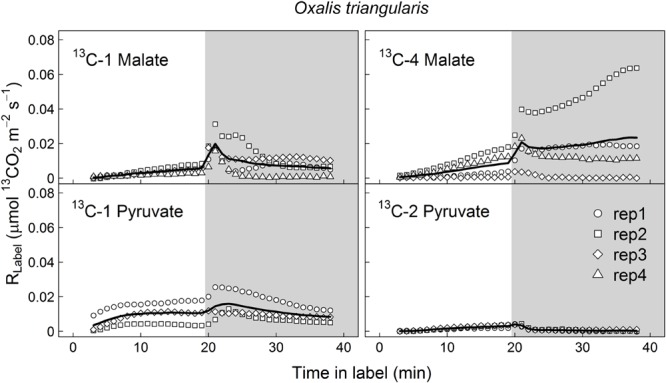

13CO2 respiration rates (RLabel) from 13C-1 and 13C-4 malate were low in the light, but steeply increased shortly after darkening during LEDR, with a peak of about 0.02 μmol 13CO2 m-2 s-1 (Figures 1 and 2). Clear light–dark differences for sums of the 13CO2 respiration rates (∫ R) reflect the observed RLabel patterns (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, ∫ R of malate substrates showed no significant position-specific and species-specific difference, showing that 13CO2 respiration from 13C-1 malate did not differ significantly compared to 13CO2 respiration from 13C-4 malate in both species during light–dark transitions (Tables 1 and 2).

FIGURE 1.

Label-derived leaf 13CO2 respiration (RLabel, μmol 13CO2 m-2 s-1) during light–dark transitions in Halimium halimifolium. Twigs with leaves were fed with position-specific 13C-labeled malate (13C-1, 13C-4) or pyruvate (13C-1, 13C-2) for about 40 min (20 min in the light and 20 min in the dark). Gray areas denote dark periods. Black bold lines denote mean values, while symbols indicate single replicates (n = 3–5 individuals).

FIGURE 2.

Label-derived leaf 13CO2 respiration (RLabel, μmol 13CO2 m-2 s-1) during light–dark transitions in Oxalis triangularis. Leaves were fed with position-specific 13C-labeled malate (13C-1, 13C-4) or pyruvate (13C-1, 13C-2) for about 40 min (20 min in the light and 20 min in the dark). Gray areas denote dark periods. Black bold lines denote mean values, while symbols indicate single replicates (n = 3–4 individuals).

Table 1.

Sums of 13CO2 respiration (∫ R) derived from different 13C-labeled substrates.

| Species | Label | ∫ R-light | ∫ R-dark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Halimium halimifolium | 13C-1 Malate | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.08 |

| 13C-4 Malate | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.11 | |

| 13C-1 Pyruvate | 0.37 ± 0.10 | 0.71 ± 0.24 | |

| 13C-2 Pyruvate | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | |

| Oxalis triangularis | 13C-1 Malate | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.05 |

| 13C-4 Malate | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.38 ± 0.19 | |

| 13C-1 Pyruvate | 0.16 ± 0.06 | 0.23 ± 0.07 | |

| 13C-2 Pyruvate | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 |

∫ R values from different 13C-labeled malate and pyruvate substrates were calculated for light (∫ R-light, μmol 13CO2 m-2 s-1) and dark periods (∫ R-dark, μmol 13CO2 m-2 s-1) in Halimium halimifolium and Oxalis triangularis plants. Means and SE are given (n = 3–5 individuals). Please refer to Table 2 for statistical analyses.

Table 2.

Statistical analyses of ∫ R and ΔLabel values from different metabolic fractions.

| Parameter | ∫ R | Lipids | Sugars | Organic Acids | Amino Acids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malate | 0.191 | 0.163 | 0.764 | 0.860 | 0.094 |

| Species | 0.960 | 0.001 | NA | 0.007 | 0.032 |

| Malate∗Species | 0.614 | 0.117 | NA | 0.666 | 0.240 |

| Time | 0.001 | 0.138 | 0.902 | 0.142 | 0.537 |

| Pyruvate | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.065 | 0.004 | 0.273 |

| Species | 0.015 | 0.001 | NA | 0.001 | 0.782 |

| Pyruvate∗Species | 0.039 | 0.544 | NA | 0.068 | 0.183 |

| Time | 0.129 | 0.028 | 0.925 | 0.101 | 0.494 |

Results of general linear models show light–dark (Time), position-specific (Malate, Pyruvate), and species-specific (Species) differences and their interactions (e.g., Malate∗Species). Please note that we separately performed statistical tests on malate and pyruvate, since a comparison of the absolute ∫ R and ΔLabel values from both substrates is potentially biased by differences in substrate transport from the assimilation site to the site of reaction, mixing with leaf internal substrate pools, and substrate compartmentalization. P-values are indicated. Significant values (P ≤ 0.05) are marked in bold.

In contrast to both 13C-labeled malate substrates, which can be released by different reactions (NAD-ME, TCA cycle), 13CO2 respiration rates from 13C-1 pyruvate reflect the direct CO2 release by a pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction (cpPDH or mtPDH). Highest RLabel values from 13C-1 pyruvate were observed in H. halimifolium, with about 0.025 μmol 13CO2 m-2 s-1 in the light, and with a pronounced peak of 0.06 μmol 13CO2 m-2 s-1 within the first minutes in the dark during LEDR, which was followed by a clear continuous decrease (Figure 1). A very different 13CO2 respiration pattern from 13C-1 pyruvate was found in O. triangularis, with no clear peak during LEDR (Figure 2). RLabel from 13C-2 pyruvate, reflecting the activity of CO2 releasing reactions within the TCA cycle, showed hardly any increase in both species (Figures 1 and 2). Statistical analyses on ∫ R values are in agreement with the observed 13CO2 respiration patterns from pyruvate substrates, showing a species-dependency for changes caused by the 13C-labeled substrates and no clear light–dark differences (Tables 1 and 2). A Tukey HSD post hoc test revealed significant position-specific differences for ∫ R from pyruvate substrates during light–dark transitions in H. halimifolium (P < 0.001), but not in O. triangularis (P = 0.354). It also shows species-specific differences for ∫ R from 13C-1 pyruvate (P ≤ 0.012), but not for ∫ R from 13C-2 pyruvate (P = 0.987). In summary, clear position- and species-specific differences during LEDR were only observed in the 13CO2 respiration pattern obtained from pyruvate.

13C Allocation to Leaf Metabolic Fractions

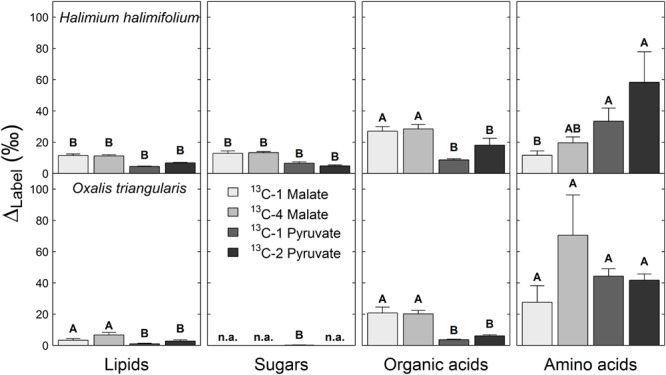

Carbon isotope ratios in leaf metabolic fractions (lipids, sugars, amino and organic acids) of H. halimifolium and O. triangularis plants did not show significant light–dark differences between the two sampling time points, except for lipids from plants fed with 13C-2 pyruvate (Table 2). Thus, mean values of both time points were used for further analysis, i.e., to determine 13C allocation of position-specific 13C-labeled substrates to metabolic fractions.

The ΔLabel derived from both 13C-labeled pyruvate substrates was highest in the amino acid fraction of both species, while ΔLabel derived from 13C-labeled malate substrates was found to be highest in both, the amino acid and the organic acid fractions (Figure 3). In contrast, ΔLabel derived from any 13C-labeled substrate was lowest in lipid and sugar fractions of in both species, or showed no distinct 13C allocation. Significant position-specific differences were only found in lipid and organic acid fractions derived from 13C-labeled pyruvate substrates, with higher ΔLabel values from 13C-2 pyruvate compared to those from 13C-1 pyruvate (Table 2). Significant species-specific differences were observed across different 13C-labeled substrates and fractions. In summary, 13C from malate and pyruvate was species-specifically allocated to leaf metabolic fractions, mainly to amino and organic acids under light conditions, while position-specific differences in 13C allocation were only observed for pyruvate.

FIGURE 3.

13C allocation of position-specific13C-labeled malate (13C-1, 13C-4) and pyruvate (13C-1, 13C-2) to metabolic fractions in Halimium halimifolium and Oxalis triangularis. The label-induced 13C increase corrected for non-labeling conditions (ΔLabel, ‰) indicates the amount of total 13C allocated to leaf metabolic fractions. Mean ΔLabel values for the two harvests (20 min light or 20 min light and 20 min dark) were calculated, since no significant light–dark differences were observed for ΔLabel, except for lipids in plants fed with 13C-2 pyruvate, which showed higher δ13C values in the dark than in the light (Table 2). Please refer to Table 2 for the statistical analyses. n.a. indicates no observable ΔLabel. Capital letters denote significant differences among metabolic fractions of plants fed with the same 13C-labeled substrate (ANOVA and Tukey-HSD). Means and SE are given (n = 3 individuals).

Discussion

Carboxyl Groups of Malate Similarly Fuel Respiration during Light–Dark Transitions

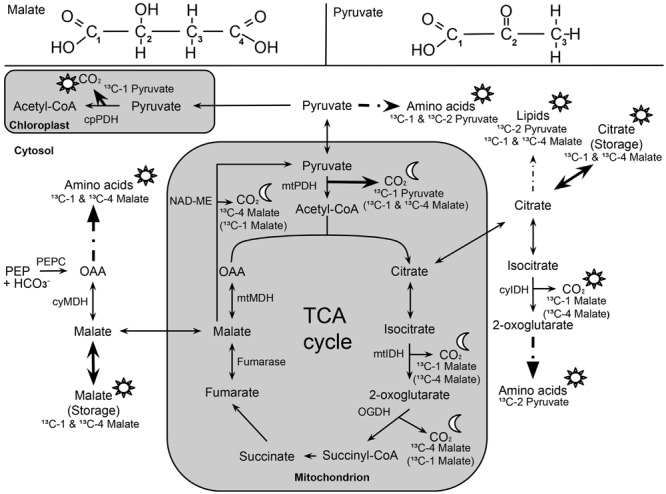

Here, we investigated the 13CO2 respiration pattern from different position-specific 13C-labeled malate and pyruvate in species with marked differences in δ13CLEDR to identify potential respiratory substrates and enzymatic reactions. Both, 13C-1 and 13C-4 malate were clearly respired during the light–dark transitions in H. halimifolium and O. triangularis (Figures 1 and 2; Table 1), demonstrating that both carboxyl groups of malate contribute to respiration, especially during LEDR. Interestingly, the 13CO2 respiration rates from 13C-1 and 13C-4 malate were similar in both species, which is surprising since only the C-4 position of malate have been suggested to be 13C enriched compared to other molecule positions (Melzer and O’Leary, 1987; Savidge and Blair, 2004) and thus expected to be of high importance for the 13C enrichment in respired CO2 during LEDR at natural isotope abundances (Barbour et al., 2007; Gessler et al., 2009; Werner et al., 2011; Tcherkez et al., 2012). The equal contribution of both carboxyl groups of malate to respiration in both species is most likely provoked by the fumarase activity, causing a partial isotope randomization of the carboxyl groups of malate (Bradbeer et al., 1958; Gout et al., 1993). For instance, 13C-label at the C-4 position of malate can be transferred to the C-1 position of malate, which can be decarboxylated by NAD-ME, producing 13C-1 labeled pyruvate that fuels mtPDH (Figure 4). This respiratory flux is in line with high NAD-ME activity during LEDR (Igamberdiev et al., 2001), which may be stimulated by fumarate in support of oxidation of photosynthetic substrates (Tronconi et al., 2015). Moreover, if randomization of malate by the fumarase reaction is assumed, the 13C-label from both carboxyl groups of malate could be released by the action of the NAD-dependent mtIDH and the OGDH in the TCA cycle. Otherwise, these reactions would only release one carboxyl group of malate; C-1 by mtIDH and C-4 by OGDH (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Overview of 13C allocation from position-specific 13C-labeled malate (13C-1, 13C-4) and pyruvate (13C-1; 13C-2) during light–dark transitions. Sun (☼) and half-moon ( ) symbols denote temporary 13C allocation during light or dark periods (LEDR), respectively. Solid arrows indicate 13C allocation of highest importance, while dashed arrows indicate reactions with intermediate steps. 13C-labeled malate substrates in brackets denote alternative respiratory pathways due to the influence of NAD-ME (decarboxylation of C-4 position of malate) and fumarase (randomization of C-1 and C-4 position of malate). The following abbreviations are used: cyIDH and mtIDH, NADP-cytosolic and NAD-mitochondrial isocitrate dehydrogenase; cyMDH and mtMDH, cytosolic and mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase; NAD-ME, NAD-malic enzyme; OAA, oxaloacetate; OGDH, 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase; cpPDH and mtPDH, chloroplast and mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase; PEPC, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase; TCA cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle.

) symbols denote temporary 13C allocation during light or dark periods (LEDR), respectively. Solid arrows indicate 13C allocation of highest importance, while dashed arrows indicate reactions with intermediate steps. 13C-labeled malate substrates in brackets denote alternative respiratory pathways due to the influence of NAD-ME (decarboxylation of C-4 position of malate) and fumarase (randomization of C-1 and C-4 position of malate). The following abbreviations are used: cyIDH and mtIDH, NADP-cytosolic and NAD-mitochondrial isocitrate dehydrogenase; cyMDH and mtMDH, cytosolic and mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase; NAD-ME, NAD-malic enzyme; OAA, oxaloacetate; OGDH, 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase; cpPDH and mtPDH, chloroplast and mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase; PEPC, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase; TCA cycle, tricarboxylic acid cycle.

Decarboxylation of 13C-labeled malate in the light was generally not very strong, but also visible in all species (Figures 1 and 2; Table 1). The theoretical background for malate respiration in light was previously described by Werner et al. (2011). At least for 13C-1 malate, this might be explained by conversion of malate via the mtMDH reaction to oxaloacetate, which is used together with glycolytic acetyl-CoA by the citrate synthase reaction to build up citrate. This citrate can then be transferred to the cytosol via the citrate shuttle, where it is converted to isocitrate and subsequently decarboxylated to α-ketoglutarate and CO2 by the NADP-dependent cytosolic isocitrate dehydrogenase reaction (cyIDH, Figure 4) (Werner et al., 2011). On the other hand, less is known about the biochemical pathways for direct respiration of 13C-4 malate in the light, since NAD-ME (Hill and Bryce, 1992; Igamberdiev et al., 2001) and TCA cycle reactions (Hanning and Heldt, 1993; Tcherkez et al., 2005; Araújo et al., 2012) are known to be partially down-regulated. Cytosolic fumarase might be involved, which was found to be expressed in some species (Pracharoenwattana et al., 2010; Eprintsev et al., 2014). However, the role of the enzyme in malate randomization in the light and during LEDR has not been elucidated yet.

Position- and Species-Specific Differences in Pyruvate Respiration Determine Natural δ13CLEDR Patterns

In contrast to 13C-labeled malate substrates, position-specific differences in RLabel were induced by the 13C-labeled pyruvate substrates (Figures 1 and 2; Table 1), which were, however, species-dependent (Table 2). Differences in 13CO2 respiration from 13C-1 pyruvate and 13C-2 pyruvate were significant in H. halimifolium, the species with high natural increases in δ13CLEDR (up to 14.8‰; Wegener et al., 2010), but not in O. triangularis, the species which exhibits only low natural increases in δ13CLEDR (up to 3.4 ‰; Wegener et al., 2010). This demonstrates a biochemical link between respiration of the C-1 position of pyruvate and the known increases in δ13CLEDR and suggests a higher mtPDH activity during LEDR in H. halimifolium compared to O. triangularis (Priault et al., 2009; Wegener et al., 2010). Pyruvate for the mtPDH reaction may be provided by different fluxes, e.g., by glycolysis, by anaplerotic PEPC fluxes (via PEPC, MDH, NAD-ME), and by fluxes from carbon storage pools such as citrate and malate (via decarboxylation reactions from TCA cycle and NAD-ME; Figure 4).

We also observed an increase in 13CO2 respiration rates from 13C-1 pyruvate in the light, especially in H. halimifolium (Figures 1 and 2; Table 1). This was most likely mainly caused by the chloroplast PDH reaction (cpPDH, Figure 4; Tcherkez et al., 2005, 2012), since the mitochondrial PDH reaction is known to be strongly down regulated under illumination (mtPDH, Figure 4), (Budde and Randall, 1990). In contrast, 13C-2 pyruvate was only weakly respired during the light–dark transitions in both species (Figures 1 and 2; Table 1). This suggests that the C-2 position of pyruvate (reflecting the acetyl-CoA residue) is predominantly used for biosynthesis of compounds during light–dark transitions. Indeed, this was further supported by position-specific 13C allocation differences in leaf metabolic fractions originated from 13C-labeled pyruvate substrates as described in the next paragraph.

13C-Label from Malate and Pyruvate Is Mainly Allocated to Amino and Organic Acids

Our final objective was to determine the 13C allocation from position-specific 13C-labeled substrates to metabolic fractions. We typically observed that 13C allocation to metabolic fractions (lipids, sugars, amino and organic acids) was high under light conditions, but immediately decreased when plants were transferred into darkness. This observation can be explained by well-known changes in transpiration and respiration rates in the dark. On the one hand, darkening causes a decrease of transpiration rates (due to decrease in vapor pressure deficit) and thus lower substrate uptake and less 13C allocation to metabolic fractions. On the other hand, most of the 13C-labeled substrates are used for respiration rather than for biosynthesis in the dark, causing an increase in 13CO2 respiration rates during LEDR in both species (Figures 1 and 2). With one exception, lipids in plants fed with 13C-2 pyruvate were significantly more enriched in 13C after darkening (Figure 3; Table 2), suggesting that the acetyl-CoA produced from pyruvate is especially used for lipogenesis during light–dark transitions. This also partially explains the low 13CO2 respiration rates from 13C-2 pyruvate compared to those from 13C-1 pyruvate in both species (Figures 1 and 2).

Furthermore, our results show that the 13C-label from both malate and pyruvate were generally allocated to the amino and organic acid fractions in both species. As summarized in Figure 4, the substrates were mostly used as precursors for the synthesis of amino acids derived from pyruvate, oxaloacetate, 2-oxoglutarate, as well as for the synthesis of organic acids such as citrate and malate, which are TCA cycle intermediates (Werner et al., 2011) or used as carbon storage molecules (Zell et al., 2010). However, with respect to the 13C-labeled substrates, we cannot distinguish if the organic acids taken up via the xylem stream were fully used for biosynthesis or if they partly accumulated in the leaves. ΔLabel values in lipids for both species suggested that only small amounts of the position-specific 13C-labeled malate and pyruvate were used for lipogenesis (Figures 3 and 4); similar results was found in a recent 14C labeling study (Grimberg, 2014). Low ΔLabel values in sugars in H. halimifolium might be explained by photosynthetic fixation of respired CO2 derived from the 13C-labeled substrates, as previously observed for pyruvate (Tcherkez et al., 2005) or malate substrates (Hibberd and Quick, 2002).

Conclusion

Based on our experiments, we provide first direct experimental evidence that both carboxyl groups of malate are used as respiratory substrates during LEDR in different species. Surprisingly, plants fed with 13C-1 or 13C-4 malate showed no position- and species-specific differences in respiration pattern and metabolic fractions, strongly indicating that the carboxyl groups of malate undergo leaf internal isotope randomization by fumarase. Thus, our findings introduce a new level of complexity to the interpretation of respiratory substrates and enzymatic reactions influencing δ13C of leaf-respired CO2 at natural isotope abundances. We conclude that malate respiration via different enzymatic reactions and metabolic pathways (e.g., fumarase, NAD-ME, and TCA cycle) supports and supplies pyruvate respiration during LEDR, which determines the species-specific differences of natural δ13CLEDR patterns via decarboxylation of the C-1 position of pyruvate by PDH reactions, as shown within this study.

Author Contributions

ML and FW equally contributed to the manuscript. ML, FW, CW, and RW designed the experiments. ML synthesized the position-specific 13C-labeled malate. FW assembled the experimental setup. ML and FW performed the experiments and acquired the raw data. ML, FW, and MB processed the data. RW, CW, NB, RS, and VM supervised data analyses and interpretation. All authors helped drafting the manuscript and gave essential input to the work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Barbara E. Kornexl (ETH Zurich) for experimental advice, Jürgen Schleucher and Ina Ehlers (both Umea University) for NMR analyses, and Gregory Goldsmith (Paul Scherrer Institute) for useful comments. Technical assistance was provided by Annika Ackermann, Noemi Umbricht, and EA Burns (all ETH Zurich), as well as by Ilse Thaufelder (University of Bayreuth). This study was financially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF project “CIFRes,” contract number 205321_132768) and by the German Research Foundation (DFG project “ECORES,” contract number WE2681/5-1). VM acknowledge the DFG grant MA 2379/8-2 and EXC 1028. ML also acknowledges a grant by COST Action ES0806 SIBAE for a short-term scientific mission.

Abbreviations

- δ13CLEDR

carbon isotopic composition of leaf-respired CO2 during LEDR

- ΔLabel

label-induced 13C increase

- cyIDH and mtIDH

cytosolic and mitochondrial isocitrate dehydrogenase

- LEDR

light enhanced dark respiration

- cyMDH and mtMDH

cytosolic and mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase

- NAD-ME

NAD-malic enzyme

- OGDH

2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase

- cpPDH and mtPDH

chloroplast and mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase

- PEPC

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase

- RLabel

label-derived leaf 13CO2 respiration

- TCA cycle

tricarboxylic acid cycle

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.00739

References

- Araújo W. L., Nunes-Nesi A., Nikoloski Z., Sweetlove L. J., Fernie A. R. (2012). Metabolic control and regulation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle in photosynthetic and heterotrophic plant tissues. Plant Cell Environ. 35 1–21. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin O. K., Evans J. R., Siebke K. (1998). Relationship between the inhibition of leaf respiration by light and enhancement of leaf dark respiration following light treatment. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 25 437–443. 10.1071/PP97159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azcon-Bieto J., Lambers H., Day D. A. (1983). Effect of photosynthesis and carbohydrate status on respiratory rates and the involvement of the alternative pathway in leaf respiration. Plant Physiol. 72 598–603. 10.1104/pp.72.3.598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour M. M., Hunt J. E., Kodama N., Laubach J., McSeveny T. M., Rogers G. N., et al. (2011). Rapid changes in δ13C of ecosystem-respired CO2 after sunset are consistent with transient 13C enrichment of leaf respired CO2. New Phytol. 190 990–1002. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03635.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour M. M., McDowell N. G., Tcherkez G., Bickford C. P., Hanson D. T. (2007). A new measurement technique reveals rapid post-illumination changes in the carbon isotope composition of leaf-respired CO2. Plant Cell Environ. 30 469–482. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01634.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbeer J. W., Ranson S. L., Stiller M. (1958). Malate synthesis in crassulacean leaves. I. The distribution of 14C in malate of leaves exposed to 14CO2 in the dark. Plant Physiol. 33 66–70. 10.1104/pp.33.1.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde R. J. A., Randall D. D. (1990). Pea leaf mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex is inactivated in vivo in a light-dependent manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87 673–676. 10.1073/pnas.87.2.673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbert M., Rascher K. G., Werner C. (2012). Species-specific differences in temporal and spatial variation in δ13C of plant carbon pools and dark-respired CO2 under changing environmental conditions. Photosynth. Res. 113 297–309. 10.1007/s11120-012-9748-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eprintsev A. T., Fedorin D. N., Sazonova O. V., Igamberdiev A. U. (2016). Light inhibition of fumarase in Arabidopsis leaves is phytochrome A-dependent and mediated by calcium. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 102 161–166. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eprintsev A. T., Fedorin D. N., Starinina E. V., Igamberdiev A. U. (2014). Expression and properties of the mitochondrial and cytosolic forms of fumarase in germinating maize seeds. Physiol. Plant. 152 231–240. 10.1111/ppl.12181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar G. D. (1983). On the nature of carbon isotope discrimination in C4 species. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 10 205–226. 10.1071/PP9830205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Florez-Sarasa I., Araújo W. L., Wallstrom S. V., Rasmusson A. G., Fernie A. R., Ribas-Carbo M. (2012). Light-responsive metabolite and transcript levels are maintained following a dark-adaptation period in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 195 136–148. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04153.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessler A., Tcherkez G., Karyanto O., Keitel C., Ferrio J. P., Ghashghaie J., et al. (2009). On the metabolic origin of the carbon isotope composition of CO2 evolved from darkened light-acclimated leaves in Ricinus communis. New Phytol. 181 374–386. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02672.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghashghaie J., Badeck F. W. (2014). Opposite carbon isotope discrimination during dark respiration in leaves versus roots – a review. New Phytol. 201 751–769. 10.1111/nph.12563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert A., Robins R. J., Remaud G. S., Tcherkez G. G. B. (2012). Intramolecular 13C pattern in hexoses from autotrophic and heterotrophic C3 plant tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 18204–18209. 10.1073/pnas.1211149109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleixner G., Schmidt H. -L. (1997). Carbon isotope effects on the fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase reaction, origin for non-statistical 13C distributions in carbohydrates. J. Biol. Chem. 272 5382–5387. 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gout E., Bligny R., Pascal N., Douce R. (1993). 13C nuclear magnetic resonance studies of malate and citrate synthesis and compartmentation in higher plant cells. J. Biol. Chem. 268 3986–3992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin K. L., Turnbull M. H. (2012). Out of the light and into the dark: post-illumination respiratory metabolism. New Phytol. 195 4–7. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimberg Å. (2014). Preferred carbon precursors for lipid labelling in the heterotrophic endosperm of developing oat (Avena sativa L.) grains. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 83 346–355. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissom C. B., Willeford K. O., Wedding R. T. (1987). Isotope effect studies of the chemical mechanism of nicotinamide adenine-dinucleotide malic enzyme from Crassula. Biochemistry 26 2594–2596. 10.1021/bi00383a027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanning I., Heldt H. W. (1993). On the function of mitochondrial metabolism during photosynthesis in spinach (Spinacia-Oleracea L.) leaves – Partitioning between respiration and export of redox equivalents and precursors for nitrate assimilation products. Plant Physiol. 103 1147–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibberd J. M., Quick W. P. (2002). Characteristics of C4 photosynthesis in stems and petioles of C3 flowering plants. Nature 415 451–454. 10.1038/415451a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill S. A., Bryce J. H. (1992) “Malate metabolism and light-enhanced dark respiration in barley mesophyll protoplasts,” in Molecular, Biochemical and Physiological Aspects of Plant Respiration eds Lambers H., Van der Plas L. H. W. (The Hague: SPB Academic Publishing; ) 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Hymus G. J., Maseyk K., Valentini R., Yakir D. (2005). Large daily variation in 13C-enrichment of leaf-respired CO2 in two Quercus forest canopies. New Phytol. 167 377–384. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01475.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igamberdiev A. U., Romanowska E., Gardeström P. (2001). Photorespiratory flux and mitochondrial contribution to energy and redox balance of barley leaf protoplasts in the light and during light-dark transitions. J. Plant Physiol. 158 1325–1332. 10.1078/0176-1617-00551 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jardine K., Wegener F., Abrell L., van Haren J., Werner C. (2014). Phytogenic biosynthesis and emission of methyl acetate. Plant Cell Environ. 37 414–424. 10.1111/pce.12164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann M. M., Rinne K. T., Blessing C., Siegwolf R. T. W., Buchmann N., Werner R. A. (2015). Malate as a key carbon source of leaf dark-respired CO2 across different environmental conditions in potato plants. J. Exp. Bot. 66 5769–5781. 10.1093/jxb/erv279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann M. M., Wegener F., Werner R. A., Werner C. (2016). Diel variations in carbon isotopic composition and concentration of organic acids and their impact on plant dark respiration in different species. Plant Biol. (Stuttg.) 10.1111/plb.12464 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer E., O’Leary M. H. (1987). Anapleurotic CO2 fixation by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase in C3 plants. Plant Physiol. 84 58–60. 10.1104/pp.84.1.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pracharoenwattana I., Zhou W. X., Keech O., Francisco P. B., Udomchalothorn T., Tschoep H., et al. (2010). Arabidopsis has a cytosolic fumarase required for the massive allocation of photosynthate into fumaric acid and for rapid plant growth on high nitrogen. Plant J. 62 785–795. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prater J. L., Mortazavi B., Chanton J. P. (2006). Diurnal variation of the δ13C of pine needle respired CO2 evolved in darkness. Plant Cell Environ. 29 202–211. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priault P., Wegener F., Werner C. (2009). Pronounced differences in diurnal variation of carbon isotope composition of leaf respired CO2 among functional groups. New Phytol. 181 400–412. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02665.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2015) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Richter A., Wanek W., Werner R. A., Ghashghaie J., Jaeggi M., Gessler A., et al. (2009). Preparation of starch and soluble sugars of plant material for the analysis of carbon isotope composition: a comparison of methods. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 23 2476–2488. 10.1002/rcm.4088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg R. M., O’Leary M. H. (1985). Aspartate beta-decarboxylase from Alcaligenes faecalis: carbon-13 kinetic isotope effect and deuterium exchange experiments. Biochemistry 24 1598–1603. 10.1021/bi00328a004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann A., Butzenlechner M., Schmidt H.-L. (1991). Evidence for a nonstatistical carbon isotope distribution in natural glucose. Plant Physiol. 96 609–614. 10.1104/pp.96.2.609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savidge W. B., Blair N. E. (2004). Patterns of intramolecular carbon isotopic heterogeneity within amino acids of autotrophs and heterotrophs. Oecologia 139 178–189. 10.1007/s00442-004-1500-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone S., Ganf G. (1981). The influence of previous light history on the respiration of four species of fresh-water phytoplankton. Arch. Hydrobiol. 91 435–462. [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Resco V., Williams D. G. (2009). Diurnal and seasonal variation in the carbon isotope composition of leaf dark-respired CO2 in velvet mesquite (Prosopis velutina). Plant Cell Environ. 32 1390–1400. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G., Boex-Fontvieille E., Mahe A., Hodges M. (2012). Respiratory carbon fluxes in leaves. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15 308–314. 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G., Cornic G., Bligny R., Gout E., Ghashghaie J. (2005) In vivo respiratory metabolism of illuminated leaves. Plant Physiol. 138 1596–1606. 10.1104/pp.105.062141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez G., Mahe A., Gauthier P., Mauve C., Gout E., Bligny R., et al. (2009) In folio respiratory fluxomics revealed by 13C isotopic labeling and H/D isotope effects highlight the noncyclic nature of the tricarboxylic acid “cycle” in illuminated leaves. Plant Physiol. 151 620–630. 10.1104/pp.109.142976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovar-Mendez A., Miernyk J. A., Randall D. D. (2003). Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in plant cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 270 1043–1049. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03469.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronconi M. A., Wheeler M. C. G., Martinatto A., Zubimendi J. P., Andreo C. S., Drincovich M. F. (2015). Allosteric substrate inhibition of Arabidopsis NAD-dependent malic enzyme 1 is released by fumarate. Phytochemistry 111 37–47. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener F., Beyschlag W., Werner C. (2010). The magnitude of diurnal variation in carbon isotopic composition of leaf dark respired CO2 correlates with the difference between δ13C of leaf and root material. Funct. Plant Biol. 37 849–858. 10.1071/FP09224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener F., Beyschlag W., Werner C. (2015). Dynamic carbon allocation into source and sink tissues determine within-plant differences in carbon isotope ratios. Funct. Plant Biol. 42 620–629. 10.1071/FP14152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner C., Gessler A. (2011). Diel variations in the carbon isotope composition of respired CO2 and associated carbon sources: a review of dynamics and mechanisms. Biogeosciences 8 2437–2459. 10.5194/bg-8-2437-2011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werner C., Wegener F., Unger S., Nogues S., Priault P. (2009). Short-term dynamics of isotopic composition of leaf-respired CO2 upon darkening: measurements and implications. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 23 2428–2438. 10.1002/rcm.4036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner R. A., Brand W. A. (2001). Referencing strategies and techniques in stable isotope ratio analysis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 15 501–519. 10.1002/rcm.258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner R. A., Bruch B. A., Brand W. A. (1999). ConFlo III – an interface for high precision δ13C and δ15N analysis with an extended dynamic range. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 13 1237–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner R. A., Buchmann N., Siegwolf R. T. W., Kornexl B. E., Gessler A. (2011). Metabolic fluxes, carbon isotope fractionation and respiration – lessons to be learned from plant biochemistry. New Phytol. 191 10–15. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03741.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zell M. B., Fahnenstich H., Maier A., Saigo M., Voznesenskaya E. V., Edwards G. E., et al. (2010). Analysis of Arabidopsis with highly reduced levels of malate and fumarate sheds light on the role of these organic acids as storage carbon molecules. Plant Physiol. 152 1251–1262. 10.1104/pp.109.151795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.