Publisher's Note: There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Key Points

Fibrin engagement of leukocyte integrin-αMβ2 restricts bile duct hyperplasia and inhibits periductal fibrosis.

Periductal fibrosis following bile duct injury is inhibited by leukadherin-1, an allosteric activator of integrin-αMβ2 fibrin binding.

Abstract

Coagulation cascade activation and fibrin deposits have been implicated or observed in diverse forms of liver damage. Given that fibrin amplifies pathological inflammation in several diseases through the integrin receptor αMβ2, we tested the hypothesis that disruption of the fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 interaction in Fibγ390-396A mice would reduce hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in an experimental setting of chemical liver injury. Contrary to our hypothesis, α-naphthylisothiocyanate (ANIT)–induced liver fibrosis increased in Fibγ390-396A mice, whereas inflammatory cytokine expression and hepatic necrosis were similar to ANIT-challenged wild-type (WT) mice. Increased fibrosis in Fibγ390-396A mice appeared to be independent of coagulation factor 13 (FXIII) transglutaminase, as ANIT challenge in FXIII-deficient mice resulted in a distinct pathological phenotype characterized by increased hepatic necrosis. Rather, bile duct proliferation underpinned the increased fibrosis in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice. The mechanism of fibrin-mediated fibrosis was linked to interferon (IFN)γ induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), a gene linked to bile duct hyperplasia and liver fibrosis. Expression of iNOS messenger RNA was significantly increased in livers of ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice. Fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 interaction inhibited iNOS induction in macrophages stimulated with IFNγ in vitro and ANIT-challenged IFNγ-deficient mice had reduced iNOS induction, bile duct hyperplasia, and liver fibrosis. Further, ANIT-induced iNOS expression, liver fibrosis, and bile duct hyperplasia were significantly reduced in WT mice administered leukadherin-1, a small molecule that allosterically enhances αMβ2-dependent cell adhesion to fibrin. These studies characterize a novel mechanism whereby the fibrin(ogen)–integrin-αMβ2 interaction reduces biliary fibrosis and suggests a novel putative therapeutic target for this difficult-to-treat fibrotic disease.

Introduction

Increased coagulation activity and hepatic fibrin(ogen) deposition have been observed in models of cholestatic liver disease, wherein bile ducts are injured and often occlude.1-3 Reflecting this experimental observation, increased deposition of thrombin-cleaved fibrin was evident clinically in livers from patients with cholestatic liver disease compared with non-diseased livers.4 However, beyond limited clinical studies indicating sustained fibrin(ogen) expression and hypercoagulability in patients with liver fibrosis caused by cholestatic liver disease,5,6 the exact role of fibrin(ogen) in the progression of this pathology has not been completely defined. Cholestatic liver disease is typically coupled to bile duct epithelial cell (BDEC) injury in the liver, as is the case with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Although the etiology of PSC is clearly associated with BDEC injury, the central trigger(s) and mechanism(s) driving the pathology are not fully understood. PSC is typified by proliferation of the bile ducts, strictures prohibiting bile flow, and excess collagen deposition around the bile ducts (ie, peribiliary fibrosis), which if sustained, can lead to liver failure and predisposition to cancer.7-9 Of importance, PSC accounts for ∼8% of all liver transplants in the United States10 and currently there is no established curative therapy for PSC.8

The xenobiotic α-naphthylisothiocyanate (ANIT) is a chemical that selectively injures BDECs.11-14 Long-term exposure of rodents to ANIT recapitulates many clinical and histopathological features of sclerosing cholangitis,4,9,15,16 including coagulation cascade activation, robust fibrin(ogen) deposition, bile duct hyperplasia, and peribiliary fibrosis.2,5,6,17 Complete fibrin(ogen) deficiency in ANIT-exposed mice provoked an atypical increase in focal liver necrosis, a unique lesion that was recapitulated in mice expressing mutant fibrin(ogen) unable to engage platelet integrin αIIbβ3.2,4 This suggests that a hemostatic function of fibrin(ogen) inhibits necrosis in this setting; however, the presence of necrosis in these mutant mice prevented us from mechanistically isolating the specific role of fibrin(ogen)-driven inflammation in peribiliary fibrosis. Here, the longstanding yet untested hypothesis in the field is that fibrin matrices formed as a consequence of injury/disease-triggered coagulation, enhance inflammatory cell (ie, leukocyte) activity leading to liver fibrosis.18 This concept is anchored in the non-hemostatic functions of fibrin polymers, including engagement of the leukocyte integrin αMβ2, which amplifies inflammation and tissue injury in many other disease settings.19-23 Notably, however, the precise function of the fibrin(ogen)-leukocyte integrin αMβ2 interaction has never been evaluated in experimental hepatic injury.

Anchored in previous studies indicating that fibrin(ogen)-driven inflammation exacerbates inflammatory disease, we tested the hypothesis that the fibrin(ogen)-integrin αMβ2 interaction promotes experimental liver inflammation and fibrosis. To test this hypothesis, we used a combination of in vivo and in vitro studies involving mice expressing a mutant form of fibrinogen lacking the binding motif for integrin αMβ2 (Fibγ390-396A mice), coagulation factor 13 (FXIII)−/− mice, and leukadherin (LA)-1, a novel small molecule integrin agonist that allosterically increases αMβ2-dependent cell adhesion to fibrin polymers.

Methods

Mice

Fibγ390-396A mice,23 mice lacking the FXIII catalytic A subunit (FXIII−/−),24 and wild-type (WT) mice on an identical C57BL/6 background were maintained by homozygous breeding. Interferon (IFN)γ−/− mice25 and WT mice on an identical congenic C57BL/6J background were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Age-matched male mice between the ages of 8 to 14 weeks were used for these studies. WT C57BL/6J mice used for bone marrow (BM) isolation were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were housed at an ambient temperature of ∼22°C with alternating 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycles, and provided water and rodent chow ad libitum prior to study initiation. Mice were maintained in Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International-accredited facilities and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Michigan State University or Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation.

ANIT and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrosis and pharmacologic interventions

Details on experimental settings of ANIT and CCl4-induced liver fibrosis and interventions with LA-1 are described in supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site.

Histopathology and clinical chemistry

A detailed description of liver histopathology, immunohistochemistry and its quantification, and clinical chemistry is available in supplemental Methods.

Isolation and culture of BM-derived macrophages

A detailed description of mouse BM macrophage isolation, culture, and treatment is available in supplemental Methods.

RNA isolation, complementary DNA synthesis, and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Details on RNA isolation and quantitative reverse-transcription (qRT)-PCR are available in supplemental Methods. Primer sequences are listed in supplemental Table 1.

Analysis of liver nonparenchymal cells (NPCs) by flow cytometry

Details on perfusion and isolation of hepatic NPCs and assessment of liver macrophages by flow cytometry are included in supplemental Methods.

Human liver samples

De-identified liver samples and associated clinical data from 16 human patients with primary biliary cirrhosis-associated or PSC-associated cirrhosis, and 27 human patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-associated cirrhosis were kindly provided by The University of Kansas Medical Center Liver Center Tissue Bank. The project entitled “Association of hemostatic factor expression with profibrogenic genes” is supported by the Kansas University Liver Center.

Statistical analyses

Comparison of 2 groups was performed using the Student t test. Comparison of 3 or more groups was performed using one- or two-way analysis of variance, as appropriate, and the Student–Newman-Keuls post hoc test. Associations between variables for human data were assessed using Pearson r correlation. Comparisons of clinical parameters were made using the Mann–Whitney U test. The criterion for statistical significance was P ≤ .05.

Results

Fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding suppresses hepatic fibrosis following chronic bile duct injury

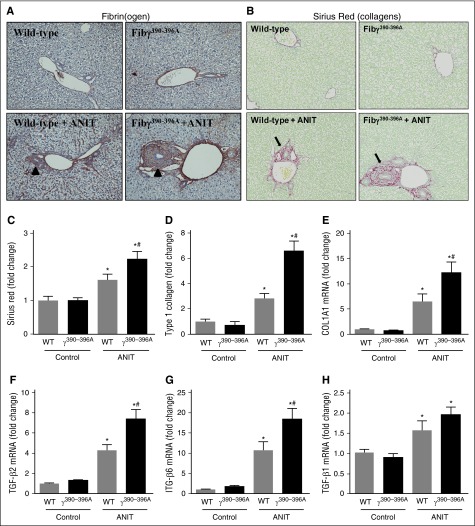

Periportal (zone 1) fibrin(ogen) deposition increased in livers of ANIT-exposed WT mice (4 weeks), particularly surrounding the bile ducts and in neighboring sinusoids (Figure 1A, arrowheads). No change in plasma fibrinogen was detectable after 4 weeks of ANIT exposure, reflecting minimal change in hepatic fibrinogen gene expression (supplemental Figure 1A-C,G). Fibγ390-396A mice express a mutant fibrinogen that cannot bind leukocyte integrin αMβ2.23 Documented evidence indicates normal hemostatic function in Fibγ390-396A mice, including fibrin polymer formation, prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time and thrombin times, and tail-bleeding analyses identical to WT mice.23 In agreement, the localization and intensity of peribiliary fibrin(ogen) staining was similar in ANIT-exposed WT and Fibγ390-396A mice, with an apparent increase in fibrin(ogen) deposition in Fibγ390-396A mice particularly evident near areas of bile duct proliferation (Figure 1A, arrowheads). Compared with WT mice, peribiliary fibrosis after 4 weeks of ANIT exposure was significantly increased in livers of Fibγ390-396A mice, marked by excessive total and type I collagen deposition in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice (Figure 1B-D). This increase in fibrosis was coupled to an exaggerated induction of the profibrogenic genes type 1 collagen (COL1A1), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β2, and ITGβ6 in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice (Figure 1E-G). In contrast, ANIT induction of TGFβ1 was not affected by genotype (Figure 1H). Interestingly, the exaggerated liver fibrosis in Fibγ390-396A mice occurred without a corresponding increase in serum enzyme biomarkers of liver injury (ie, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase; supplemental Figure 2A-B). Moreover, the induction of several pro-inflammatory mediators linked to fibrosis was unaffected by genotype in ANIT-exposed mice (supplemental Figure 2C-H). Peribiliary fibrosis (supplemental Figure 3, arrows) was also increased in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice after 8 weeks of ANIT exposure (supplemental Figure 3A-E), and this was similarly observed without an increase in serum ALT activity (supplemental Figure 3F). Collectively, the results indicate that experimental bile duct fibrosis is increased in Fibγ390-396A mice compared with WT mice.

Figure 1.

Increased fibrosis in livers of ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice. WT and Fibγ390-396A mice were fed a control diet (AIN-93M) or an identical diet containing 0.025% ANIT for 4 weeks. (A) Representative photomicrographs show liver sections stained for fibrin(ogen) (brown) (×200). Arrowheads indicate peribiliary fibrin(ogen) deposits. (B) Representative photomicrographs show liver sections stained for collagens with sirius red (×200). Arrows indicate peribiliary collagen deposition. (C) Sirius red and (D) type I collagen stains were quantified as described in “Methods.” Hepatic expression of mRNAs encoding the profibrogenic genes: (E) COL1A1, (F) TGFβ2, (G) ITGβ6, and (H) TGFβ1 were determined by real-time qPCR. Data are expressed as mean + standard error of the mean (SEM); mice fed a control diet (n = 4) and mice fed an ANIT diet (n = 10 to 16 mice per group). *P < .05 vs control diet within genotype; #P < .05 vs WT mice fed the same diet.

FXIII-deficient mice develop a pathological phenotype distinct from Fibγ390-396A mice after ANIT exposure

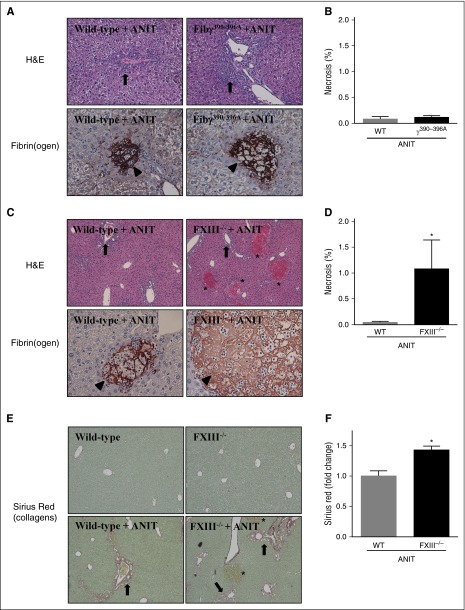

Fibγ390-396A mice were shown to develop venous thrombi of reduced size due to red blood cell exclusion from venous clots.26 This occurred secondary to a reduced rate of FXIII-mediated crosslinking.26 To address the possibility that a reduced rate of FXIII-mediated crosslinking could form the basis for exaggerated liver fibrosis in Fibγ390-396A mice, we compared hepatic fibrin(ogen) deposition in Fibγ390-396A mice with that of FXIII−/− mice exposed to ANIT, and determined the effect of FXIII deficiency on ANIT-induced liver fibrosis. Chronic exposure of mice to ANIT produces two distinct pathologies in the liver, bile duct hyperplasia, and fibrosis (ie, surrounding bile ducts in zone 1), and acute focal hepatocellular necrosis (ie, often termed bile infarcts). Bile duct hyperplasia was evident in ANIT-exposed WT mice and this seemed to increase in Fibγ390-396A mice (Figure 2A, arrows). In agreement with serum enzyme levels (supplemental Figure 2A-B), focal hepatocellular necrosis was very rare in both ANIT-exposed WT mice and ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice (Figure 2B). Fibrin(ogen) deposits observed in these infrequent necrotic lesions were similar in WT and Fibγ390-396A mice, appearing as a dense network spanning the lesion, which seemed to outline the border of previously intact hepatocytes (Figure 2A, arrowheads).

Figure 2.

Hepatocellular necrosis and fibrin(ogen) deposition in livers of ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A and FXIII−/− mice. WT, Fibγ390-396A, and FXIII−/− mice were fed control a diet (AIN-93M) or an identical diet containing 0.025% ANIT for 4 weeks. Representative photomicrographs show liver sections stained for H&E or fibrin(ogen) (brown) from: (A) Fibγ390-396A mice, (C) FXIII−/− mice, and (A,C) corresponding WT mice exposed to ANIT. Arrows indicate areas of bile duct hyperplasia. Arrowheads indicate fibrin(ogen) deposits within areas of hepatocellular necrosis. Asterisks indicate focal hepatocellular necrosis or bile infarcts. Images are ×200 except hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections in (C), which are ×100. (B,D) Area of necrosis was determined as described in “Methods.” (E) Representative photomicrographs show liver sections stained for sirius red (×200). Arrows indicate peribiliary collagen deposition. Asterisks indicate focal hepatocellular necrosis (ie, bile infarcts). (F) Sirius red staining was quantified as described in “Methods.” Data are expressed as mean + SEM; n = 4 to 16 mice per group.*P < .05 vs ANIT-exposed WT mice.

In complete contrast to ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice, focal hepatocellular necrosis evident as bile infarcts (Figure 2C, asterisks) significantly increased in ANIT-exposed FXIII−/− mice compared with ANIT-exposed WT mice (Figure 2D). As compared with WT mice, fibrin(ogen) deposits within focal necrosis in ANIT-exposed FXIII−/− mice appeared less intense, and lacked a defined pattern within the lesion (Figure 2C, arrowhead). The markedly elevated necrosis in FXIII−/− mice appeared to be secondary to significantly increased peribiliary fibrosis in ANIT-exposed FXIII−/− mice compared with ANIT-exposed WT mice (Figure 2E-F). No obvious distinction in the peribiliary fibrin(ogen) deposits were observed in WT and FXIII−/− mice exposed to ANIT for 4 weeks (not shown). Thus, ANIT-exposed FXIII−/− mice developed increased focal hepatocellular necrosis with altered hepatic fibrin(ogen) deposition, a pathology distinct from ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice.

Fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding suppresses ANIT-induced bile duct hyperplasia

BDECs express a number of profibrogenic genes that drive local periductal fibrosis by activating adjacent portal fibroblasts.27 These include TGFβ2 and ITGβ6,3,27-30 genes expressed to a greater extent in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice (Figure 1F-G). Thus, we explored the possibility that increased fibrosis in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice could be anchored to an expansion of intrahepatic BDECs. Histologic analyses indicated that ANIT-exposed mice developed classic biliary hyperplasia, as indicated by cytokeratin (CK)-19 staining (Figure 3A, arrows), one marker of biliary epithelium in mice. Notably, bile duct hyperplasia was significantly exacerbated in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice compared with ANIT-exposed WT mice (Figure 3A-B). Although biliary hyperplasia tended to increase in ANIT-exposed FXIII−/− mice, this increase was not statistically significant (Figure 3C-D). This implies that excessive bile duct hyperplasia and related profibrogenic gene induction could be one mechanism underlying the exaggerated liver fibrosis in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice.

Figure 3.

Biliary hyperplasia in ANIT-exposed mice. WT, Fibγ390-396A, and FXIII−/− mice were fed a control diet (AIN-93M) or an identical diet containing 0.025% ANIT for 4 weeks. Representative photomicrographs (×200) show liver sections stained for CK-19 (brown) in ANIT-exposed: (A) Fibγ390-396A mice, (C) FXIII−/− mice, and (A,C) corresponding WT mice. Arrows indicate areas of biliary hyperplasia. Asterisks indicate focal hepatocellular necrosis (ie, bile infarcts). (B,D) CK-19 staining was quantified as described in “Methods.” Data are expressed as mean + SEM; n = 4 to 16 mice per group. *P < .05 vs ANIT-exposed WT mice.

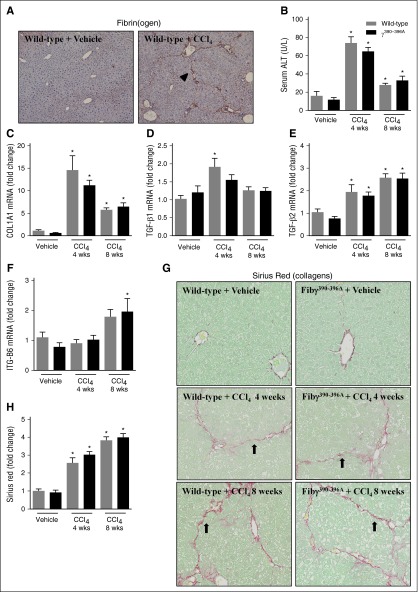

Fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding does not control experimental liver fibrosis in the absence of classical bile duct proliferation

If bile duct hyperplasia were central to the mechanism whereby fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding controlled hepatic fibrosis, we hypothesized that expression of γ390-396A fibrinogen would not impact fibrosis in a model lacking classic bile duct hyperplasia. Thus, for comparison we selected CCl4-induced liver fibrosis, wherein the chronic administration of toxicant produces liver fibrosis distinct in pattern from ANIT, and without classic bile duct hyperplasia.31 Similar to a previous study,32 hepatic fibrin(ogen) deposits were also observed in WT mice challenged with CCl4 (8 weeks) in a pattern resembling more the borders of the hepatic acinus (Figure 4A, arrowhead). Fibrin(ogen) deposition was similar in CCl4-challenged Fibγ390-396A mice (not shown). Hepatocellular injury, indicated by elevation of serum ALT activity, was similar in CCl4-challenged WT and Fibγ390-396A mice after 4 and 8 weeks of exposure (Figure 4B). The CK-19–positive cell population in CCl4-challenged mice lacked characteristics of classic biliary hyperplasia (supplemental Figure 4). Liver fibrosis was similar in WT and Fibγ390-396A mice challenged with chronic CCl4 exposure for 4 and 8 weeks, marked by hepatic collagen deposition (Figure 4G-H) and induction of profibrogenic genes in the liver (Figure 4C-F).

Figure 4.

Effect of CCl4 challenge on liver fibrosis in Fibγ390-396A mice. WT and Fibγ390-396A mice were exposed to vehicle (corn oil) (left) or CCl4 (10% at 10 μL/g, IP) (right) for 4 and 8 weeks as described in “Methods.” (A) Representative photomicrographs (×200) show liver sections stained for fibrin(ogen) (brown) in CCl4-treated WT mice after 8 weeks. Arrowhead indicates fibrin(ogen) deposition resembling borders of hepatic acinus. (B) Serum ALT activity was determined as described in “Methods.” Hepatic expression of mRNAs encoding the profibrogenic genes: (C) COL1A1, (D) TGFβ1, (E) TGFβ2, and (F) ITGβ6 was determined by real-time qPCR. (G) Representative photomicrographs show liver sections stained for sirius red (×200). Arrows indicate collagen deposition resembling borders of hepatic acinus. (H) Sirius red staining was quantified as described in “Methods.” Gray bars indicate WT and black bars indicate Fibγ390-396A mice. Mice treated with vehicle (n = 4 to 5 mice per group) and mice treated with CCl4 (n = 9 to 10 mice per group). *P < .05 vs vehicle within genotype. IP, intraperitoneal; Wks, weeks.

Suppression of type 1 cytokine-driven macrophage activation by fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding: a potential mechanism controlling pathological bile duct hyperplasia and fibrosis

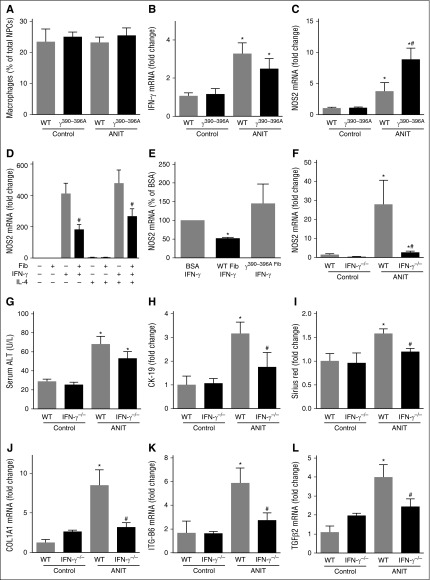

Despite a marked induction of numerous inflammatory chemokines in livers of ANIT-exposed mice (supplemental Figure 2C-H), we did not observe an effect of ANIT exposure or genotype on the number of hepatic macrophages (Figure 5A). Of importance, we and others have shown lymphocyte accumulation in livers of ANIT-exposed mice.2,33 Increased expression of type 1 cytokines, including IFNγ is observed in ANIT-exposed rodents.33 IFNγ promotes pro-inflammatory (ie, “classical”) macrophage activation.34 We found that hepatic IFNγ messenger RNA (mRNA) increased similarly in ANIT-exposed WT and Fibγ390-396A mice (Figure 5B). However, hepatic induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS/NOS2) mRNA, a readout of pro-inflammatory macrophage activation34 increased in livers of patients with PSC35 and was dramatically increased in livers of ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice compared with ANIT-exposed WT mice (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Suppression of type 1 cytokine-driven macrophage activation by fibrin(ogen)-αM β2 binding. WT, Fibγ390-396A, and IFNγ−/− mice were fed a control diet (AIN-93M) or an identical diet containing 0.025% ANIT for 4 weeks. (A) Hepatic macrophage number was determined by flow cytometry as described in “Methods.” Hepatic expression of mRNAs encoding the genes: (B) IFNγ and (C,F) NOS2 was determined by real-time qPCR. (D) Expression of NOS2 mRNA in BM macrophages plated on either bovine serum albumin (BSA) or surface adhered WT fibrinogen (10 μg/mL) and stimulated with recombinant mouse IFNγ and/or recombinant mouse interleukin-4 (10 ng/mL) for 24 hours. (E) Expression of NOS2 mRNA in IFNγ-stimulated BM macrophages plated on BSA, WT fibrinogen, or γ390-396A fibrinogen (10 μg/mL). (G) Serum ALT activity was determined as described in “Methods.” (H) CK-19 and (I) sirius red staining were quantified as described in “Methods.” Hepatic expression of mRNAs encoding the profibrogenic genes: (J) COL1A1, (K) ITGβ6, and (L) TGFβ2 were determined by real-time qPCR. Data are expressed as mean + SEM; n = 4 to 16 mice per group for in vivo studies; for in vitro studies, results represent macrophages from 9 mice. *P < .05 vs control diet within genotype; #P < .05 vs ANIT-exposed WT mice or respective treatment on BSA. Fib, fibrinogen.

IFNγ and integrin signaling pathways are known to interact.36 Thus, we tested the hypothesis that the fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding could suppress IFNγ-mediated NOS2 induction. Fibrinogen adhered to a surface, such as cell culture plastic, and engages αMβ2, allowing us to test this hypothesis in vitro. Compared with a BSA-coated surface, IFNγ-mediated NOS2 mRNA induction was significantly attenuated in macrophages cultured on a fibrinogen-coated surface (Figure 5D). Similar results were obtained when the cells were treated with IFNγ and interleukin-4, a cytokine capable of promoting alternative macrophage activation (Figure 5D). Whereas WT fibrinogen significantly inhibited IFNγ-mediated NOS2 mRNA induction, this effect was lost when the cells were cultured on γ390-396A fibrinogen (Figure 5E). This suggests that the fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding could suppress IFNγ induction of NOS2 mRNA, forming a mechanistic basis for enhanced NOS2 mRNA expression in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice. Indeed, we found that NOS2 mRNA induction in ANIT-exposed mice was dramatically reduced in IFNγ−/− mice (Figure 5F). IFNγ deficiency had no impact on serum ALT in ANIT-exposed mice (Figure 5G). However, bile duct hyperplasia (Figure 5H and supplemental Figure 5B) and hepatic fibrosis (Figure 5I and supplemental Figure 5A), along with hepatic profibrogenic gene induction (Figure 5J-L), were significantly reduced in ANIT-exposed IFNγ−/− mice compared with ANIT-exposed WT mice. Collectively, these studies suggest a mechanism whereby fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding could inhibit bile duct proliferation and liver fibrosis, and are the first to define the precise role of IFNγ in ANIT-induced bile duct fibrosis.

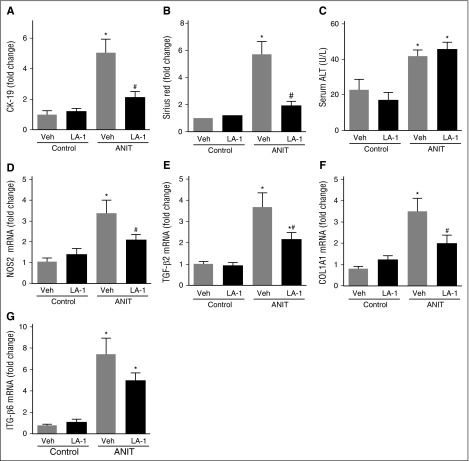

The novel allosteric αMβ2 integrin activator LA-1 reduces collagen deposition in WT mice with established periductal fibrosis

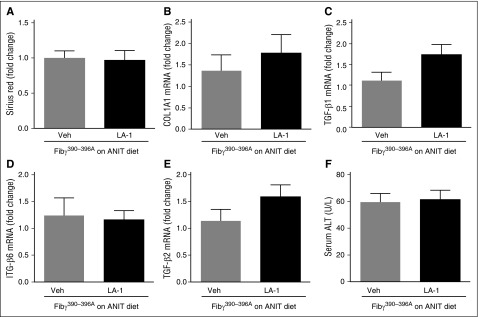

The novel small molecule LA-1 has previously been shown to act selectively on αMβ2 to enhance binding of the integrin to fibrin through an allosteric mechanism.37,38 We postulated that LA-1 treatment would suppress ANIT-induced biliary fibrosis. To evaluate the effect of LA-1 treatment on mice with established liver disease, WT mice were exposed to ANIT for 6 weeks and given LA-1 (0.4 mg/kg per day, IP) or vehicle (1.5 μL dimethylsulfoxide [DMSO] in 100 μL sterile phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) twice daily during weeks 5 and 6. LA-1 treatment significantly attenuated bile duct hyperplasia (Figure 6A) and hepatic fibrosis (Figure 6B) in ANIT-exposed mice, as indicated by CK-19 and sirius red staining, respectively, without affecting serum ALT activity (Figure 6C). Interestingly, LA-1 treatment also attenuated the induction of NOS2, TGFβ2, COL1A1, and ITGβ6 mRNAs in ANIT-exposed mice (Figure 6D-G). Finally, we assessed whether the impact of LA-1 treatment on fibrosis required fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding. Of importance, LA-1 failed to affect liver fibrosis, profibrogenic gene expression, or serum ALT activity in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice (Figure 7). This suggests that the therapeutic effects of LA-1 in this experimental setting require fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 integrin binding.

Figure 6.

Treatment with the novel allosteric αM β2 integrin activator LA-1 reduces fibrosis in livers of WT mice with established periductal fibrosis. WT mice were fed a control diet (AIN-93M) or an identical diet containing 0.025% ANIT for 6 weeks. Mice were treated with vehicle (1.5 μL DMSO in 100 μL sterile PBS) or LA-1 twice daily (0.4 mg/kg per day, IP) in weeks 5 and 6. (A) CK-19 staining and (B) sirius red staining were quantified as described in “Methods.” (C) Serum ALT activity determined was as described in “Methods.” Hepatic expression of mRNAs encoding the genes: (D) NOS2, (E) TGFβ2, (F) COL1A1, and (G) ITGβ6 was determined by real-time qPCR. Data are expressed as mean + SEM; mice fed the control diet (n = 5) and mice fed the ANIT diet (n = 12 to 13 mice per group). *P < .05 vs respective treatment on control diet; #P < .05 vs vehicle-treated ANIT-exposed mice. Veh, vehicle.

Figure 7.

LA-1 fails to reduce fibrosis in livers of ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice. Fibγ390-396A mice were fed a diet containing 0.025% ANIT for 6 weeks. Mice were treated with vehicle (1.5 μL DMSO in 100 μL sterile PBS) or LA-1 twice daily (0.4 mg/kg per day, IP) in weeks 5 and 6. (A) Sirius red staining was quantified as described in “Methods.” Hepatic expression of mRNAs encoding the profibrogenic genes: (B) COL1A1, (C) TGFβ1, (D) ITGβ6, and (E) TGFβ2 were determined by real-time qPCR. (F) Serum ALT activity was determined as described in “Methods.” Data are expressed as mean + SEM; n = 7 mice per group. Veh, vehicle.

Discussion

Fibrin deposits are often assigned a pathological role in studies of acute and chronic liver damage. In part, this is driven by evidence that anticoagulants attenuate fibrin deposition concurrent with a reduction in experimental fibrosis.39,40 However, the reduction of fibrosis by anticoagulants cannot be definitively ascribed to changes in fibrin(ogen), due to the fact that thrombin has multiple downstream targets that may influence fibrotic changes. Previous studies have indicated a seminal role for the thrombin receptor protease activated receptor-1 in fibroblast activation in vitro and liver fibrosis in vivo in several experimental mouse models.3,40-42 To date, evidence supporting a pro-inflammatory and profibrogenic function of fibrin in experimental hepatic fibrosis has largely been “guilt by association,” because fibrin deposits frequently co-localize with damaged liver tissue and/or collagen. Contradicting this assumption, we found that fibrin(ogen) engagement of leukocyte integrin-αMβ2 had no impact on chronic CCl4-induced liver fibrosis, a result consistent with previous findings by Pohl et al,43 in mice completely lacking fibrinogen. We further describe a novel mechanism wherein fibrin(ogen) inhibits experimental bile duct hyperplasia and fibrosis, mediated by the leukocyte integrin-αMβ2 binding motif located in the carboxyl-terminal domain of the fibrinogen γ-chain. Previous studies implicated this domain in driving inflammation in the context of multiple disease states.19-23 Now, we can extend the mechanistic contributions of fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 engagement to include modulation of leukocyte activation and anti-fibrotic function in bile duct injury.

Fibγ390-396A mice are documented to have normal hemostasis and arterial thrombosis similar to WT mice.23 However, red blood cells are excluded from venous thrombi in Fibγ390-396A mice, owing to a reduced rate of FXIII-mediated γ390-396A fibrinogen crosslinking.26 Whether intrahepatic fibrin(ogen) deposits resemble one of these forms of thrombosis, or something entirely unique, is not known. Thus, it is difficult to completely exclude a role for this process in the observed phenotype of ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice. However, we observed a dramatic increase in hepatic necrosis in ANIT-exposed FXIII−/− mice, a pathological feature completely distinct from ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice. Thus, it is not likely that reduced FXIII fibrin crosslinking function in and of itself is the primary mechanism of increased fibrosis in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice. Interestingly, fibrin(ogen) had an altered, diffuse appearance in necrotic lesions in livers of FXIII−/− mice. It is plausible that FXIII-mediated crosslinking of fibrin(ogen) within foci of necrosis is an essential precursor to protective hemostatic effect of fibrin(ogen) mediated by binding the platelet integrin αIIBβ3 (supplemental Figure 7).2 Consistent with this, FXIII deficiency was associated with delayed liver repair after acute CCl4-induced liver injury.44 To our knowledge, these are the first studies to examine the role of FXIII in experimental liver fibrosis, leading to unexpected discovery of a protective function of FXIII in limiting hepatocellular necrosis in ANIT-exposed mice.

Although liver pathology was quite distinct in ANIT-exposed FXIII−/− mice and Fibγ390-396A mice, we cannot exclude the possibility that delayed FXIII-mediated crosslinking contributes to increased fibrosis in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice. Indeed, FXIII deficiency also increased fibrosis after ANIT exposure. One hypothesis is that FXIII-mediated crosslinking increases the affinity of fibrin for αMβ2 (ie, FXIII-crosslinked fibrin is a better ligand of αMβ2 than non-crosslinked fibrin), although to our knowledge this has not yet been examined. Notably, biliary fibrosis increased in FXIII−/− mice without a robust increase in bile duct hyperplasia, distinguishing this response from ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice. Because hepatic necrosis was uniquely increased in FXIII−/− mice, the increase in fibrosis may also occur by mechanisms secondary to the necrosis. Overall, given the complex liver pathology observed in FXIII−/− mice exposed to ANIT, it seems premature to conclude definitively as to the precise role of FXIII in liver fibrosis. Indeed, one human study found that the FXIII Val34Leu polymorphism, which increases the rate of thrombin-mediated FXIII activation, was associated with faster fibrosis progression in patients with viral hepatitis B and C.45 Collectively, there is a need for additional studies defining the role of FXIII, and specifically FXIII-mediated fibrin crosslinking, in experimental and clinical liver fibrosis.

The role of fibrin(ogen) in experimental fibrosis appears to be highly tissue- or even context-specific. For example, fibrin(ogen) actually promotes tissue fibrosis in models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy19,20 and kidney injury.46 However, complete fibrin(ogen) deficiency had no impact on chemical-induced lung fibrosis.47 Our results indicate that even within a single organ system, fibrin(ogen) engagement of integrin-αMβ2 can have disparate roles depending on the experimental context/pathology. In ANIT-exposed mice, the disruption of fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding resulted in excessive bile duct hyperplasia. Proliferating BDECs express higher levels of profibrogenic mediators,3,28,48 including the αVβ6 integrin, which directs local generation of active TGFβ1 protein and portal fibroblast activation.3,28,29,48,49 Indeed, hepatic expression of the β6 subunit increased dramatically in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice. αVβ6 expression is selective to BDECs and αVβ6 contributes to biliary fibrosis in multiple models of bile duct injury.3,28,29,50 In contrast, we found that neither classic bile duct hyperplasia nor ITGβ6 mRNA expression increased in CCl4-exposed mice, and αVβ6 does not participate in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis.50 Collectively, these observations suggest that the suppression of liver fibrosis by fibrin(ogen) engagement of integrin αMβ2 occurs secondary to a reduction in bile duct hyperplasia.

There may be multiple mechanisms whereby fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding inhibits bile duct fibrosis, but it seems plausible that liver macrophages play a central role. Depending on their gene expression profile, macrophages can promote liver fibrosis, and cytokines driving macrophages toward this profibrogenic phenotype are increased in livers of ANIT-exposed rodents (eg, IFNγ). We found that IFNγ drives bile duct hyperplasia and fibrosis in ANIT-exposed mice, the first mechanistic validation of the suggestion that IFNγ drives this pathology.33 In ANIT-exposed mice, IFNγ induced hepatic expression of iNOS, one pro-inflammatory macrophage biomarker expressed in patients with PSC and linked to biliary hyperplasia and fibrosis.35 Here, we show for the first time that IFNγ is responsible for induction of iNOS in ANIT-exposed mice. Despite having a similar induction of IFNγ, hepatic iNOS expression was markedly enhanced in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice. Anchoring this observation to an in vitro mechanism, we found that fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding suppressed IFNγ-mediated iNOS induction in macrophages. Interestingly, there is precedent for this pathway, as other studies have suggested that ITAM-coupled integrins can inhibit IFN signaling in macrophages.36 Collectively, the results suggest a mechanism wherein fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding inhibits bile duct hyperplasia and the ensuing fibrosis in ANIT-exposed mice by inhibiting IFNγ-mediated macrophage activation (supplemental Figure 7). Although additional experimentation is required, this hypothesis is consistent with the exciting concept that fibrin(ogen) deposition is not just reactive to tissue injury, but instead can carefully tailor local leukocyte activity to modify disease progression.

Human liver diseases vary with their etiology and thus may have differing mechanistic paths driving fibrosis. Particularly for cholestatic liver diseases, where treatment options are limited, capturing key differences in mechanism or clinical pathology may reveal unique targets for treatment. Previous studies have suggested that patients with cholestatic liver disease have preserved levels of plasma fibrinogen,5,6,51,52 whereas fibrinogen levels tend to decrease in patients with liver disease of noncholestatic origin. This has not been observed in all cases, and may relate to differential regulation of hepatic fibrinogen. Interestingly, plasma fibrinogen levels at 4 weeks were normal in ANIT-exposed mice, but decreased after CCl4 treatment (supplemental Figure 1G). This difference, and the differential inhibition of fibrosis by fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding in these experimental settings prompted us to explore whether there were any interesting associations between hepatic fibrin(ogen) and profibrogenic gene expression in diseased human livers. Interestingly, we found that expression of the rate-limiting fibrinogen β chain inversely associated with COL1A1 mRNA expression in cirrhotic livers from patients with PSC/primary biliary cirrhosis, but not in cirrhotic livers from patients with traditionally noncholestatic liver disease (ie, hepatitis C/HCV) (supplemental Figure 6). The exact basis for this association in PSC patients and lack thereof in HCV patients is not clear, and interpretation should be cautious. However, viewed in the context of results from the 2 fibrosis models, this could suggest a unique association between fibrinogen expression and/or function in cholestatic liver disease. The results support a need for additional clinical analyses of fibrin(ogen) expression and regulation in patients with different types of liver disease.

Identification of the fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 interaction as a putative mechanism to inhibit biliary fibrosis suggests a novel therapeutic target. To explore this concept, we employed the novel small molecule LA-1, an αMβ2 integrin agonist that allosterically enhances αMβ2-dependent cell adhesion to fibrin polymers.37 Using an interventional treatment paradigm, we found that LA-1 reduced bile duct hyperplasia and fibrosis in ANIT-exposed WT mice, even when administered after the mice had developed disease. The precise cellular mechanism whereby LA-1 reduces bile duct hyperplasia and fibrosis requires additional investigation. However, our observation that LA-1 treatment did not reduce fibrosis in ANIT-exposed Fibγ390-396A mice implies that the mechanism whereby LA-1 reduces fibrosis in this experimental context requires the αMβ2 integrin-binding domain of the fibrin(ogen) molecule. The appeal of this therapeutic strategy is increased by the fact that targeting the fibrin αMβ2-binding domain could be accomplished without necessarily compromising fibrin polymerization or the role of fibrin in hemostasis.

In the present study, we found that the integrin-αMβ2 binding domain of fibrin(ogen) inhibits liver fibrosis specifically coupled to bile duct proliferation. The mechanism appeared distinct from FXIII-mediated crosslinking, as we show for the first time that FXIII-deficient mice develop focal hepatic necrosis as a unique phenotype accompanying biliary fibrosis. Rather, a combination of in depth in vivo and in vitro studies suggested a novel mechanism where fibrin(ogen)-αMβ2 binding inhibits IFNγ-driven leukocyte activation, thereby reducing bile duct hyperplasia and fibrosis in mice. Finally, we provide proof-of-principle experimental evidence that this pathway can be pharmacologically targeted to inhibit bile duct hyperplasia and fibrosis in mice (supplemental Figure 7). Overall, these carefully paired and well-controlled studies significantly advance the field by illuminating an entirely novel and druggable pathway wherein hemostatic factors control the progression of experimental liver disease.

Authorship

Contribution: N.J., A.K.K., M.J.F., and J.P.L. participated in concept and research design; N.J., A.K.K., J.L.R., H.C.-F., C.E.R., and J.P.L. conducted experiments; N.J., A.N., T.S., M.J.F., C.E.R., R.N., and J.P.L. performed data analysis and interpreted data; N.J., A.K.K., J.L.R., R.N., T.R.Z., M.J.F., and J.P.L. wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript; and N.J., A.K.K., J.L.R., H.C.-F., A.N., T.S., R.N., T.R.Z., M.J.F., C.E.R., and J.P.L. approved the final version to be published.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: James P. Luyendyk, Department of Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation, Michigan State University, 1129 Farm Lane, 253 Food Safety and Toxicology Building, East Lansing, MI 48824; e-mail: luyendyk@cvm.msu.edu.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01 ES017537) and (NIH 5T32GM092715), and AgBioResearch at Michigan State University. The content of this study is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

References

- 1.Wang H, Vohra BPS, Zhang Y, Heuckeroth RO. Transcriptional profiling after bile duct ligation identifies PAI-1 as a contributor to cholestatic injury in mice. Hepatology. 2005;42(5):1099–1108. doi: 10.1002/hep.20903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joshi N, Kopec AK, O’Brien KM, et al. Coagulation-driven platelet activation reduces cholestatic liver injury and fibrosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(1):57–71. doi: 10.1111/jth.12770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan BP, Weinreb PH, Violette SM, Luyendyk JP. The coagulation system contributes to alphaVbeta6 integrin expression and liver fibrosis induced by cholestasis. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(6):2837–2849. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luyendyk JP, Kassel KM, Allen K, et al. Fibrinogen deficiency increases liver injury and early growth response-1 (Egr-1) expression in a model of chronic xenobiotic-induced cholestasis. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(3):1117–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pihusch R, Rank A, Göhring P, Pihusch M, Hiller E, Beuers U. Platelet function rather than plasmatic coagulation explains hypercoagulable state in cholestatic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2002;37(5):548–555. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Ari Z, Panagou M, Patch D, et al. Hypercoagulability in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis evaluated by thrombelastography. J Hepatol. 1997;26(3):554–559. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirschfield GM, Karlsen TH, Lindor KD, Adams DH. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1587–1599. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindor KD, Kowdley KV, Harrison ME American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guideline: primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(5):646–659. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Björnsson E, Olsson R, Bergquist A, et al. The natural history of small-duct primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(4):975–980. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim WR, Lake JR, Smith JM, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2013 Annual Data Report: liver. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(suppl 2):1–28. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietrich CG, Ottenhoff R, de Waart DR, Oude Elferink RPJ. Role of MRP2 and GSH in intrahepatic cycling of toxins. Toxicology. 2001;167(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00459-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jean PA, Roth RA. Naphthylisothiocyanate disposition in bile and its relationship to liver glutathione and toxicity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50(9):1469–1474. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jean PA, Bailie MB, Roth RA. 1-Naphthylisothiocyanate-induced elevation of biliary glutathione. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;49(2):197–202. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)00469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker BA, Plaa GL. The nature of alpha-naphthylisothiocyanate-induced cholestasis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1965;7(5):680–685. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(65)90125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fickert P, Pollheimer MJ, Beuers U, et al. International PSC Study Group (IPSCSG) Characterization of animal models for primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). J Hepatol. 2014;60(6):1290–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollheimer MJ, Fickert P. Animal models in primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;48(2-3):207–217. doi: 10.1007/s12016-014-8442-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joshi N, Kopec AK, Towery K, Williams KJ, Luyendyk JP. The antifibrinolytic drug tranexamic acid reduces liver injury and fibrosis in a mouse model of chronic bile duct injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;349(3):383–392. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.210880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neubauer K, Knittel T, Armbrust T, Ramadori G. Accumulation and cellular localization of fibrinogen/fibrin during short-term and long-term rat liver injury. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(4):1124–1135. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vidal B, Ardite E, Suelves M, et al. Amelioration of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in mdx mice by elimination of matrix-associated fibrin-driven inflammation coupled to the αMβ2 leukocyte integrin receptor. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(9):1989–2004. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vidal B, Serrano AL, Tjwa M, et al. Fibrinogen drives dystrophic muscle fibrosis via a TGFbeta/alternative macrophage activation pathway. Genes Dev. 2008;22(13):1747–1752. doi: 10.1101/gad.465908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinbrecher KA, Horowitz NA, Blevins EA, et al. Colitis-associated cancer is dependent on the interplay between the hemostatic and inflammatory systems and supported by integrin alpha(M)beta(2) engagement of fibrinogen. Cancer Res. 2010;70(7):2634–2643. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams RA, Bauer J, Flick MJ, et al. The fibrin-derived gamma377-395 peptide inhibits microglia activation and suppresses relapsing paralysis in central nervous system autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 2007;204(3):571–582. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flick MJ, Du X, Witte DP, et al. Leukocyte engagement of fibrin(ogen) via the integrin receptor alphaMbeta2/Mac-1 is critical for host inflammatory response in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(11):1596–1606. doi: 10.1172/JCI20741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Souri M, Koseki-Kuno S, Takeda N, Degen JL, Ichinose A. Administration of factor XIII B subunit increased plasma factor XIII A subunit levels in factor XIII B subunit knock-out mice. Int J Hematol. 2008;87(1):60–68. doi: 10.1007/s12185-007-0005-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalton DK, Pitts-Meek S, Keshav S, Figari IS, Bradley A, Stewart TA. Multiple defects of immune cell function in mice with disrupted interferon-gamma genes. Science. 1993;259(5102):1739–1742. doi: 10.1126/science.8456300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aleman MM, Byrnes JR, Wang JG, et al. Factor XIII activity mediates red blood cell retention in venous thrombi. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(8):3590–3600. doi: 10.1172/JCI75386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dranoff JA, Wells RG. Portal fibroblasts: underappreciated mediators of biliary fibrosis. Hepatology. 2010;51(4):1438–1444. doi: 10.1002/hep.23405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patsenker E, Popov Y, Stickel F, Jonczyk A, Goodman SL, Schuppan D. Inhibition of integrin alphavbeta6 on cholangiocytes blocks transforming growth factor-beta activation and retards biliary fibrosis progression. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(2):660–670. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Popov Y, Patsenker E, Stickel F, et al. Integrin alphavbeta6 is a marker of the progression of biliary and portal liver fibrosis and a novel target for antifibrotic therapies. J Hepatol. 2008;48(3):453–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milani S, Herbst H, Schuppan D, Stein H, Surrenti C. Transforming growth factors beta 1 and beta 2 are differentially expressed in fibrotic liver disease. Am J Pathol. 1991;139(6):1221–1229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geerts AM, Vanheule E, Praet M, Van Vlierberghe H, De Vos M, Colle I. Comparison of three research models of portal hypertension in mice: macroscopic, histological and portal pressure evaluation. Int J Exp Pathol. 2008;89(4):251–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2008.00597.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hugenholtz GCG, Meijers JCM, Adelmeijer J, Porte RJ, Lisman T. TAFI deficiency promotes liver damage in murine models of liver failure through defective down-regulation of hepatic inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2013;109(5):948–955. doi: 10.1160/TH12-12-0930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tjandra K, Sharkey KA, Swain MG. Progressive development of a Th1-type hepatic cytokine profile in rats with experimental cholangitis. Hepatology. 2000;31(2):280–290. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mills CD. M1 and M2 macrophages: oracles of health and disease. Crit Rev Immunol. 2012;32(6):463–488. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v32.i6.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaiswal M, LaRusso NF, Shapiro RA, Billiar TR, Gores GJ. Nitric oxide-mediated inhibition of DNA repair potentiates oxidative DNA damage in cholangiocytes. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(1):190–199. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Gordon RA, Huynh L, et al. Indirect inhibition of toll-like receptor and type I interferon responses by ITAM-coupled receptors and integrins. Immunity. 2010;32(4):518–530. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maiguel D, Faridi MH, Wei C, et al. Small molecule-mediated activation of the integrin CD11b/CD18 reduces inflammatory disease. Sci Signal. 2011;4(189):ra57. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Celik E, Faridi MH, Kumar V, Deep S, Moy VT, Gupta V. Agonist leukadherin-1 increases CD11b/CD18-dependent adhesion via membrane tethers. Biophys J. 2013;105(11):2517–2527. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abdel-Salam OM, Baiuomy AR, Ameen A, Hassan NS. A study of unfractionated and low molecular weight heparins in a model of cholestatic liver injury in the rat. Pharmacol Res. 2005;51(1):59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiorucci S, Antonelli E, Distrutti E, et al. PAR1 antagonism protects against experimental liver fibrosis. Role of proteinase receptors in stellate cell activation. Hepatology. 2004;39(2):365–375. doi: 10.1002/hep.20054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rullier A, Gillibert-Duplantier J, Costet P, et al. Protease-activated receptor 1 knockout reduces experimentally induced liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294(1):G226–G235. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00444.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaça MDA, Zhou X, Benyon RC. Regulation of hepatic stellate cell proliferation and collagen synthesis by proteinase-activated receptors. J Hepatol. 2002;36(3):362–369. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pohl JF, Melin-Aldana H, Sabla G, Degen JL, Bezerra JA. Plasminogen deficiency leads to impaired lobular reorganization and matrix accumulation after chronic liver injury. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(6):2179–2186. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63069-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsujimoto I, Moriya K, Sakai K, Dickneite G, Sakai T. Critical role of factor XIII in the initial stages of carbon tetrachloride-induced adult liver remodeling. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(6):3011–3019. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dik K, de Bruijne J, Takkenberg RB, et al. Factor XIII Val34Leu mutation accelerates the development of fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B and C. Hepatol Res. 2012;42(7):668–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Craciun FL, Ajay AK, Hoffmann D, et al. Pharmacological and genetic depletion of fibrinogen protects from kidney fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;307(4):F471–F484. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00189.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hattori N, Degen JL, Sisson TH, et al. Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in fibrinogen-null mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(11):1341–1350. doi: 10.1172/JCI10531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munger JS, Huang X, Kawakatsu H, et al. The integrin alpha v beta 6 binds and activates latent TGF beta 1: a mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell. 1999;96(3):319–328. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hahm K, Lukashev ME, Luo Y, et al. Alphav beta6 integrin regulates renal fibrosis and inflammation in Alport mouse. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(1):110–125. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang B, Dolinski BM, Kikuchi N, et al. Role of alphavbeta6 integrin in acute biliary fibrosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(5):1404–1412. doi: 10.1002/hep.21849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jedrychowski A, Hillenbrand P, Ajdukiewicz AB, Parbhoo SP, Sherlock S. Fibrinolysis in cholestatic jaundice. BMJ. 1973;1(5854):640–642. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5854.640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Segal H, Cottam S, Potter D, Hunt BJ. Coagulation and fibrinolysis in primary biliary cirrhosis compared with other liver disease and during orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1997;25(3):683–688. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]